May 8, 2020

The 2020-21 Budget

California's Spring Fiscal Outlook

- What Does the Pandemic Mean for the Economy?

- What Is Our Estimate of the Budget Problem?

- What Is Our Assessment and Guidance?

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1: How Do We Calculate the Budget Problem?

- Appendix 2: Using the BSA in 2020‑21

- Appendix 3: Figures

Executive Summary

The public health emergency associated with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) pandemic has resulted in sudden and severely negative economic consequences for California. This has significant implications for the state’s budget. This report—our Spring Fiscal Outlook—provides an update on the budget’s condition in light of this seismic shift. Specifically, we provide our estimates of the potential size of the budget problem—assuming a baseline level of expenditures—that the Legislature could face for 2020‑21. Ultimately, the May Revision will include different revenue estimates and expenditure proposals than we used to arrive at our assessment of the budget problem. In fact, the administration very recently released an estimate of the budget problem—about $54 billion—that is significantly higher than either of our estimates. The intent of this document, however, is to give the Legislature a sense of our estimate of the baseline problem going into the May Revision and to help prepare policymakers for the tremendous fiscal challenges ahead.

Report Includes Two Economic Scenarios. Although much is unclear about the economy, we can be fairly confident that the state currently is in a deep recession. The budgetary impact of that recession will depend on its depth and duration, which are difficult to anticipate. In light of this uncertainty, our outlook presents two potential scenarios (1): a somewhat optimistic “U‑shaped” recession, and (2) a somewhat pessimistic “L‑shaped” recession. These scenarios do not depict the best case or worst case. Outcomes beyond the range of our scenarios—especially those worse than we show—are entirely possible.

Budget Problem of $18 Billion to $31 Billion. Under the somewhat optimistic U‑shaped recession scenario assumptions, the state would have to address an $18 billion budget problem in the upcoming budget process. Under the somewhat pessimistic L‑shaped recession scenario assumptions, the state would face a budget problem of $31 billion. (A budget problem—also called a deficit—occurs when resources for the upcoming fiscal year are insufficient to cover the costs of currently authorized services.) The administration’s estimate is substantially larger than the higher range of our estimate largely because they focus on gross changes to the budget’s bottom line while our estimates include the net effects of current law.

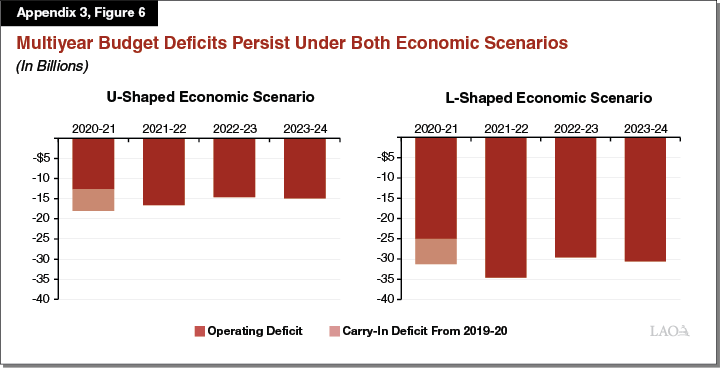

Budget Deficits Persist for Years to Come. The state’s newly emergent fiscal challenges are unlikely to dissipate quickly and will extend well beyond the end of the public health crisis. Under both of our economic scenarios, budget deficits persist until at least 2023‑24. Over the entire multiyear period, deficits sum to $64 billion in the U‑shaped recession and $126 billion in the L‑shaped recession.

Reserves Are Insufficient to Cover the Budget Problems. Budget reserves are the main tool that the state has to address a budget problem. Under our two economic scenarios, the state has around $16 billion in total reserves. However, due to the constitutional rules governing the state’s main reserve account, we think lawmakers could only have access to around $10 billion of its reserves in 2020‑21. Further, the state’s overall reserve level will be inadequate to cover multiyear budget deficits. That said, unlike in past recessions when the state had virtually no reserves on hand and deep cuts were immediately necessary, California today has built a sizeable reserve, which will cushion the coming budget crunch.

Guidance for Addressing the Budget Problem. The report concludes with our guidance for the Legislature as it begins considering how to address the shortfall. First, we recommend the Legislature use a mix of the tools at its disposal in approaching the 2020‑21 budget problem. These are: using reserves, reducing expenditures, increasing revenues, and shifting costs. Second, given that multiyear budget deficits are likely to persist for years to come, ongoing solutions are necessary to bring the budget into structural alignment. Third, while programmatic reductions will be necessary, we encourage the Legislature to mitigate actions that could worsen the public health crisis or compound personal economic challenges facing Californians. Finally, we encourage the Legislature to begin making these difficult, but necessary, decisions in June rather than waiting until future budget actions. Delaying action could only increase the size of the ultimate budget problem and make some solutions more difficult to implement.

The public health emergency associated with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) pandemic has resulted in sudden and severe economic consequences for California. This has significant implications for the upcoming budget. While the January Governor’s budget anticipated the state would have a surplus to allocate in 2020‑21, the administration’s forthcoming May Revision forecasts a substantial decline in state revenues and an ensuing budget deficit. Policymakers face a constitutional deadline to pass a balanced budget by June 15 for the upcoming fiscal year, 2020‑21.

Given the seismic shift in public health and economic conditions, we have updated our fiscal outlook—typically produced each fall—to help the Legislature prepare for the May Revision. This report—our Spring Fiscal Outlook—gauges the potential size of the budget problem under two sets of economic conditions and a “workload” or “baseline” level of expenditures. (We also identify some alternatives available to the Legislature to reduce the baseline expenditure level without reducing the level of state services being provided today.) Ultimately, the May Revision will include different revenue estimates and expenditure proposals than we used to arrive at our assessment of the budget problem.

What Does the Pandemic Mean for the Economy?

Pandemic Presents Major Disruptions and Uncertainty. The COVID‑19 pandemic has necessitated dramatic changes to the daily lives of California’s residents and businesses. While these changes clearly have had far‑reaching negative impacts on the state economy, the ultimate extent and severity of these impacts will remain unclear for some time. Much will depend on the trajectory of the public health crisis. How long will social distancing measures be necessary? How long until an effective treatment or vaccine is widely available? How long until people feel comfortable resuming prior levels of spending and economic activity? These questions are impossible to answer with certainty but are crucially important to the path of the state economy going forward.

What We Know: Economy Is in a Deep Recession. Although much is unclear about the economy, we can be fairly confident that the state (and the rest of the world) currently is in a deep recession. Since the beginning of March, 3 million to 4 million Californians appear to have lost their jobs. Households have curtailed spending significantly. Nationally, spending at restaurants was down about 25 percent in March. New car purchases were down by almost half in April. Pending home sales so far this spring have dropped by over 40 percent in major markets in California. These declines in economic activity surpass the worst of the Great Recession in most cases.

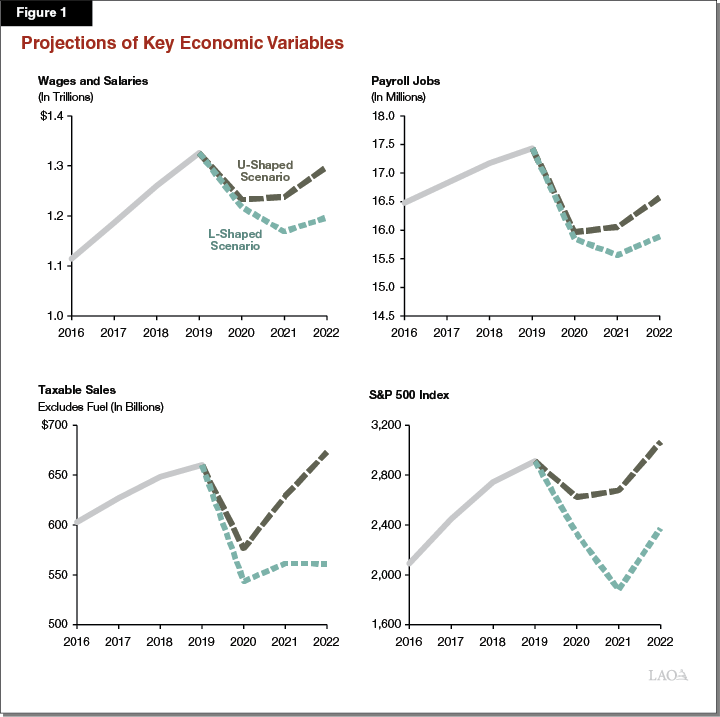

Key Unknown: How Long Will the Recession Last? While economic activity has declined sharply, the severity of the recession and its impact on Californians will depend not only on the depth of the downturn but also on how long it lasts. Anticipating the length of the downturn is extremely difficult. In light of this uncertainty, our outlook looks at two potential scenarios. These scenarios aim to illustrate the range of common predictions among economists, from a somewhat optimistic view on one end to a somewhat pessimistic view on the other. Crucially, we do not attempt to capture all possible outcomes, and our scenarios are not depictions of the best‑case or worst‑case scenarios. Outcomes beyond the range of our scenarios—especially those worse than we show—are entirely possible. We discuss the contours of our two scenarios below. Figure 1 shows our assumptions for key economic variables under each scenario.

“U‑Shaped” Recession. On the somewhat optimistic end of potential paths for the economy is the so‑called U‑shaped recession. Under this scenario, the economy would begin to see meaningful recovery this summer, as broadly measured by personal income and employment. Although economic activity would remain below pre‑recession levels well into 2021, the recovery would take a more rapid pace beginning in the second half of 2021. A key observation in support of this scenario is that, prior to the pandemic, the economy did not appear to have the types of imbalances that led to previous recessions. Prior to the current downturn, household borrowing was much lower than it was leading into the Great Recession. Similarly, there did not appear to be signs of major overheating in key assets, as with stocks in the dot‑com recession and housing in the Great Recession. As a result, Californians may be in a better position to weather the downturn and the economy may be poised to rebound more quickly once the threat of the virus subsides.

“L‑Shaped” Recession. A somewhat pessimistic potential path for the economy is the so‑called L‑shaped recession. Under this scenario, the economy would remain in a significant slump well into 2021. Gradual recovery would begin in the second half of 2021, but the economy would not return to pre‑recession levels until at least 2023. Several factors could drive such a protracted downturn. Some factors relate to the virus and the associated public health response. For example, as public health restrictions are eased some residents or businesses may attempt to resume activities too quickly, leading to renewed outbreaks and the need for additional rounds of restrictions. Some factors relate to potential economic fallout of the virus. For example, the current scale of job losses could mean many workers will remain out of the workforce for an extended period of time. Additionally, many businesses could be forced into bankruptcy as they are unable to weather the current shutdown or are unable to adapt their operations to allow social distancing.

What Is Our Estimate of the Budget Problem?

Using the two economic scenarios described earlier, this section presents our estimates of the possible budget problem. (The box below describes what the term “budget problem” means in more detail.) We begin by describing the budget problem assuming the state were to maintain its current service level. Next, we describe some alternative assumptions that—if used—would result in a lower (or higher) budget problem. Finally, we conclude with our estimate of the budget problem that could occur over the multiyear period.

What Is a Budget Problem?

A budget problem—also called a budget deficit—occurs when resources for the upcoming fiscal year are insufficient to cover the costs of currently authorized services. As such, calculating the budget problem involves two main steps:

- Projecting Anticipated Revenues. First, we estimate how much revenue will be available for the upcoming year. This means using assumptions about how the economy is likely to perform over the coming 14 months and then using those assumptions to project revenue collections.

- Estimating Current Service Level. Second, we compare those anticipated revenues to the level of spending to support the current service level (roughly the service level of the 2019‑20 Budget Act). Projecting current service spending, which we also call “baseline spending,” has several components. For example, it requires us to project how caseload will change for means‑tested programs, estimate how much federal funding will come to the state based on current federal policy, and make many other assessments.

When current service level spending exceeds anticipated revenues the state has a budget problem. In this document, the budget problem is reflected in the 2020‑21 ending balance in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties, shown in Figure 3 and Figure 4.

Budget Problem Must Be Addressed. The State Constitution requires the Legislature to pass a balanced budget. As a result, when the state faces a budget problem, the Legislature must solve the problem using a combination of tools. The main tool for solving a budget problem is building a savings account—called a reserve. If reserves are insufficient to cover the budget problem, however, the Legislature must take other actions to bring the budget into balance. These actions include reducing spending, increasing revenues, and/or shifting costs.

Budget Problem of $18 Billion to $31 Billion for 2020‑21

Figure 2 summarizes the key assumptions in each of the two economic scenarios assuming the state maintains its current service level.

Figure 2

Key Assumptions for LAO Baseline Budget Estimates

|

U‑Shaped Scenario |

L‑Shaped Scenario |

|

|

Economy |

Economy begins meaningful recovery this summer, but remains below pre‑recession levels well into 2021. The recovery takes a more rapid pace beginning in the second half of 2021. |

Economy remains in a significant slump well into 2021. Gradual recovery begins in the second half of 2021, but the economy does not return to pre‑recession levels until at least 2023. |

|

Schools and Community Colleges (Proposition 98) |

The state funds schools and community colleges in 2020‑21 at the enacted 2019‑20 level, adjusted for the 2.31 percent statutory cost‑of‑living adjustment and changes in attendance. |

The state funds schools and community colleges in 2020‑21 at the enacted 2019‑20 level, adjusted for the 2.31 percent statutory cost‑of‑living adjustment and changes in attendance. |

|

Other Programs |

The state funds: |

|

|

||

|

The state does not fund: |

||

|

||

|

Federal Funding |

The state receives: |

The state receives: |

|

|

|

|

CRF funds not allocated to address state costs. |

CRF funds not allocated to address state costs. |

|

|

COVID‑19 = coronavirus disease 2019; MOUs = memorandum of understanding; FEMA = Federal Emergency Management Agency; FMAP = federal medical assistance percentage; and CRF = Coronavirus Relief Fund. |

||

Budget Problem of $18.1 Billion Under U‑Shaped Recession. Figure 3 shows our estimate of the General Fund condition under the somewhat optimistic U‑shaped recession scenario described earlier. As the figure shows, under these economic assumptions, the state would have an $18.1 billion budget problem to solve in the upcoming budget process.

Figure 3

General Fund Condition Under LAO Spring Outlook

General Fund, U‑Shaped Scenario (in Millions)

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$8,403 |

‑$3,332 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

140,271 |

132,873 |

|

Expenditures |

152,006 |

145,517 |

|

Ending fund balance |

‑$3,332 |

‑$15,977 |

|

Encumbrances |

2,145 |

2,145 |

|

SFEU Balance |

‑5,477 |

‑18,122 |

|

Reserves |

||

|

BSA balance |

$15,630 |

$15,630 |

|

Safety Net Reserve |

900 |

900 |

|

Total Reserves |

$16,530 |

$16,530 |

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties and BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

||

Budget Problem of $31.4 Billion Under L‑Shaped Recession. Figure 4 shows our estimate of the General Fund condition under the somewhat pessimistic L‑shaped recession scenario. As the figure shows, under these economic assumptions, the state would have a $31.4 billion budget problem to solve in the upcoming budget process.

Figure 4

General Fund Condition Under LAO Spring Outlook

General Fund, L‑Shaped Scenario (in Millions)

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$8,295 |

‑$4,210 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

139,536 |

120,465 |

|

Expenditures |

152,040 |

145,517 |

|

Ending fund balance |

‑$4,210 |

‑$29,262 |

|

Encumbrances |

2,145 |

2,145 |

|

SFEU Balance |

‑6,355 |

‑31,407 |

|

Reserves |

||

|

BSA balance |

$15,302 |

$15,302 |

|

Safety Net Reserve |

900 |

900 |

|

Total Reserves |

$16,202 |

$16,202 |

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties and BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

||

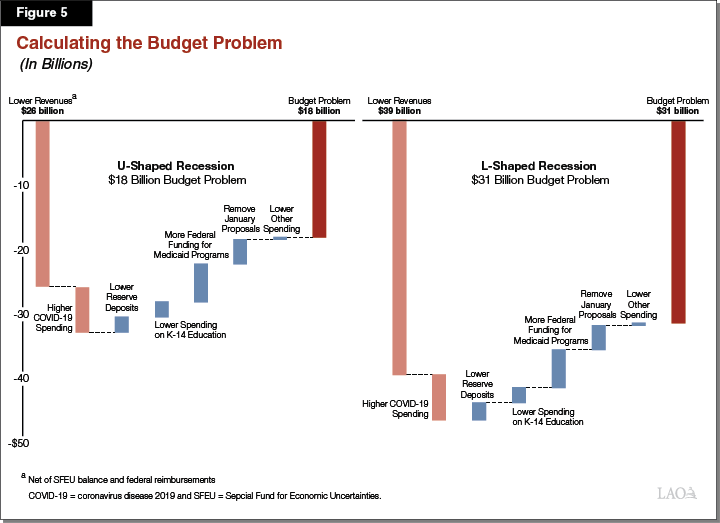

How Do We Calculate the Budget Problem Under the Two Scenarios? Figure 5 summarizes the key components of our calculation estimating the size of the budget problem. (We explain each of these component in more detail in “Appendix 1.”) They are:

- Lower Revenues. Under our estimates, revenues and other resources are lower, on net, by $26 billion in the U‑shaped recession scenario and $39 billion in the L‑shaped recession scenario.

- COVID‑19 Spending. Using an estimate from the administration, we assume the state spends $7 billion on COVID‑19‑related costs and 75 percent of those costs are reimbursed by the federal government (the latter is accounted for in revenues).

- Lower Reserve Deposits. We assume the state suspends the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) deposit in 2020‑21. On net, this, and other automatic deposit changes, increases resources available by $2.4 billion in the U‑shaped recession and $2.7 billion in the L‑shaped recession.

- Lower Spending on K‑14 Education. We assume the state funds schools and community colleges at the 2019‑20 enacted level, adjusted for inflation and attendance. The box below describes this assumption and the associated savings relative to the Governor’s budget in more detail.

- More Federal Funding for Medicaid Programs. We estimate the recently enacted enhanced federal cost share for state Medicaid programs (Medi‑Cal, In‑Home Supportive Services, and some developmental services) results in roughly $6 billion in savings in both scenarios.

- Remove January Proposals. Our estimates eliminate all discretionary funding proposals from the January Governor’s budget, which reduces costs by $3.8 billion.

How Do We Treat Proposition 98 in the Budget Problem Calculation?

Assume Cost‑Adjusted 2019‑20 Funding for Schools and Community Colleges. To estimate the budget problem under the two scenarios, we assume the state funds schools and community colleges in 2020‑21 at the enacted 2019‑20 level, adjusted for inflation and attendance. Essentially, this estimate accounts for the “current service level” of K‑14 education rather than the constitutional minimum level. (This is similar to the approach we used for other programs in the state budget. As we describe later, funding K‑14 education at the constitutional minimum level would result in substantially lower General Fund costs.) From 2018‑19 to 2020‑21, General Fund spending on K‑14 education would be $2.4 billion lower than the Governor’s January budget level in the U‑shaped recession and $2.3 billion lower in the L‑shaped recession. The difference between the two scenarios results from differing assumptions regarding property tax revenue.

Reserves Total Around $16 Billion… The bottom of Figure 3 and Figure 4 show total reserves available to address the respective budget problems. As the figures show, under the two scenarios, the state would have either $16.5 billion or $16.2 billion in total reserves. (The total reserve amounts differ by scenario because the BSA deposit for 2019‑20 changes depending on revenue estimates.) The box below describes how these reserve estimates are related to the state’s current cash position.

Cash Management

A Sizeable Cash Cushion Allows the State to Withstand the Delay in the Tax Filing Date… The state’s sizeable reserve balances have contributed to a strong cash position in recent years. In the coming weeks, this cash position will decline. The State Controller’s Office has estimated that while the state’s cash cushion was around $40 billion at the end of March, that balance will decline to roughly $9 billion by the end of the fiscal year. The single largest reason for this decline is the delay of the state’s tax filing date from April to July. Despite this decline, however, the administration does not anticipate that California will require external borrowing to manage cash flows in the current fiscal year.

…But State’s Cash Position Will Change Dramatically in the Coming Months. When normal collections resume, the state’s cash position could improve, but a variety of factors will continue to limit the state’s available cash. This includes: depressed economic activity which will lead to lower revenues, the use of the state’s General Fund and special fund reserves to pay for currently authorized services, and higher costs as the state responds to COVID‑19. As such, cash management is likely to become a more prominent feature in legislative deliberations and decision‑making in this budget process and future budgets.

…But Absent Using Reserves for a Disaster, the State Can Only Access Around $9 Billion of BSA in 2020‑21. Proposition 2 (2014) places restrictions on withdrawals from the BSA. Absent the Governor proposing to use a portion of the BSA to address costs related to the COVID‑19 emergency, funds could not be withdrawn in 2019‑20. This would mean that, under our revenue estimates, only a portion of the BSA could be withdrawn in 2020‑21. Specifically, we estimate about $9.4 billion would be accessible in the U‑shaped recession scenario and $9.2 billion would be available in the L‑shaped scenario. “Appendix 2” describes this estimate and our reasoning in more detail.

Budget Problem Lower Under Alternative Assumptions

Our estimate of the budget problem—$18 billion to $31 billion—would be lower if we made alternative assumptions. Those alternative assumptions, which might help guide the Legislature as it begins to consider how to approach the budget problem, are described in this section.

Use Federal Coronavirus Relief Funding to Cover Costs. Congress recently established the Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) to provide money to state, local, tribal, and territorial governments for “necessary expenditures incurred due to the public health emergency with respect to the Coronavirus Disease 2019” that are incurred between March 1 and December 30, 2020. We estimate California’s state government is eligible for $9.5 billion from the CRF. Recent guidance from the U.S. Department of the Treasury outlines the eligible uses of these funds. We think the state has a good argument to use most—or all—of this total to cover current state costs. However, because there is substantial uncertainty in how the Treasury will implement its guidance, we have not assumed the funding is used in this way.

Eliminate Cost‑of‑Living Adjustments (COLAs). Our estimates of the budget problem assume the state provides inflation‑related cost increases in order to maintain current service levels, although those increases are not necessarily required under current law or policy. For example, we provide COLAs to state employee salaries (after current bargaining agreements expire), universities, and K‑14 education. Eliminating all the various COLAs would result in General Fund savings of $2.1 billion in 2020‑21. Most of these savings—$1.7 billion—would come from eliminating the COLA for K‑14 education.

Fund Schools and Community Colleges at Constitutional Minimum Level. Rather than holding funding for schools and community colleges flat over the budget period, the state alternatively could provide the minimum required funding level allowed by Proposition 98 (1988). Funding at the minimum level would reduce the budget problem by $10.1 billion in the U‑shaped recession and $15.4 billion in the L‑shaped recession. Historically, the state has provided the minimum level of funding for schools and community colleges, even when those levels result in year‑over‑year reductions. This approach, however, would involve extraordinary reductions in overall education funding. The box below provides an update on the minimum guarantee under our economic scenarios in more detail.

Update on the Proposition 98 Guarantee

Proposition 98 Sets Minimum Funding Level. Proposition 98 (1988) established an annual funding requirement for schools and community colleges commonly known as the minimum guarantee. The California Constitution sets forth formulas for calculating the guarantee. These formulas depend upon various inputs, including General Fund revenue, per capita personal income, and student attendance. The state meets the guarantee through a combination of General Fund and local property tax revenue. Although the state can provide more funding than required, in practice it usually funds at or near the guarantee. With a two‑thirds vote of each house of the Legislature, the state can suspend the guarantee and provide less funding than the formulas require that year.

Proposition 98 Guarantee Down Significantly Under Both Scenarios. Under our U‑shaped scenario, the minimum guarantee is $13.3 billion lower than the Governor’s January estimates over the 2018‑19 through 2020‑21 budget period. Under the L‑shaped scenario, the guarantee is $18.6 billion lower. In both scenarios, most of the drop is related to 2020‑21 and reflects lower General Fund revenues. In each year of the period, the General Fund share of the guarantee drops about 40 cents for every dollar of lower revenue. Slower growth in local property tax revenue also contributes to a lower guarantee in both scenarios. Appendix 3 provides more information on our estimates of the minimum guarantee.

Pull Back Recent Augmentations and Allocations That Are Not Yet Disbursed. Another way to conceptualize the “current service level” is to consider the level of benefits and services being provided by the state today (rather than those that will be provided in the future under law). In this case, the state could eliminate funding provided in recent budgets and law that has not yet been disbursed or for which implementation has not begun. For example the state could:

- Return funds to the General Fund for infrastructure and maintenance projects that have not begun construction.

- Revert unspent funds from state departments and other entities, like universities.

- Delay implementation of recently enacted laws.

- Rescind funds for other recent legislative augmentations that have not been distributed to providers, local governments, or other beneficiaries.

Our initial review suggests there could be up to $3.8 billion in recent augmentations that can be reduced without affecting today’s service level. However, we were unable to get verification from the administration on this list. Compiling a more complete list would require more information from the administration, particularly the Department of Finance.

Other Alternative Assumptions. We have identified some other areas of the budget where alternative assumptions about baseline spending are possible, although some of these options would mean reducing today’s level of services. For example, in January, the administration defined $1.7 billion in recent augmentations that are subject to suspension in 2021‑22 as “discretionary” augmentations in 2020‑21. Our definition of “discretionary spending” would not include these items, however, removing them from baseline spending would reduce the budget problem by this amount. In addition, there are hundreds of millions of dollars in recent federal funding that could probably be used to offset state costs. Finally, the Governor could pause the minimum wage increase scheduled for January 1, 2020. We currently estimate, however, that the net budgetary savings from this action likely would not be significant in 2020‑21.

Why Is the Administration’s Estimate of the Deficit Larger?

The administration published a letter on May 7 indicating they estimate the budget problem for 2020‑21 is $54.3 billion. This estimate is substantially larger than our bottom line figure for the L‑shaped recession scenario. While we are still reviewing this estimate and have not yet received full information about it, we have identified a few preliminary reasons for our difference. In particular, the administration’s estimate of the budget problem assumes:

- Revenues are slightly lower than our L‑shaped recession scenario.

- Caseload‑driven costs are higher by billions of dollars.

- All of the Governor’s budget discretionary proposals are part of baseline costs.

- The Governor’s budget proposed level of spending for Proposition 98 remains roughly unchanged.

The key differences between our estimates is not necessarily the result of substantially differing assessments of the path of the economy or its effects on state programs. Rather, it is a question of how we display the bottom line numbers. In effect, the administration’s estimates largely reflect gross changes in the budget’s bottom line while our estimate includes the net effects of current law.

Budget Problems Linger for Multiyear Period

Ongoing Budget Problem of $20 Billion to $30 Billion. Under both of our economic scenarios, budget deficits persist until at least 2023‑24. This occurs despite the fact that the U‑shaped recession assumes the economy begins to recover this summer and the L‑shaped recession assumes the economy begins recovering later in 2021. The state would face annual deficits of about $20 billion in the somewhat optimistic U‑shaped recession scenario through 2023‑24 (the last year of our projections). In the somewhat pessimistic L‑shaped recession scenario, the state would face annual deficits of around $30 billion and an even larger budget problem in 2021‑22 than this year. Over the entire multiyear period, deficits sum to $64 billion in the U‑shaped scenario and $126 billion in the L‑shaped scenario. We show these estimates in “Appendix 3, Figure 4.”

What Is Our Assessment and Guidance?

Addressing the Budget Problem

Significant Budget Problems Likely to Persist in Years to Come. Some might have anticipated the state would face a deep—but short lived—budget problem in response to the COVID‑19 public health emergency. Our analysis shows, however, that the state’s fiscal challenges will not go away quickly and likely will extend well beyond the end of the public health crisis. Accordingly, long‑term solutions to bring the budget into structural alignment are needed.

Reserves Are Insufficient to Cover the Budget Problem. When the state faces a budget problem, the Legislature must solve it using a combination of tools. The main tool is the state’s reserve. However, existing reserves will not be sufficient to cover the budget problem in 2020‑21 and beyond. This means the Legislature will need to reduce spending, increase revenues, and/or shift costs to bring the budget into alignment. Although we focus on alternative expenditure assumptions in this report, we recommend the Legislature use a mix of all four tools in approaching the 2020‑21 budget problem.

California’s Reserves Nonetheless Yield Key Advantages. While the state’s reserves are insufficient to address the budget problem, they provide several important benefits. First, reserves will reduce the need for expenditure reductions or revenue increases—every dollar of reserves held today is a dollar in one‑time programmatic cuts that can be avoided. Second, reserves allow the state to phase in reductions to expenditures more slowly, reducing their potential impact during the most acute period of the public health and economic crisis. Finally, some budgetary reductions will take time to implement. Reserves serve as an interim solution, buying lawmakers time to implement those longer‑term reductions. Unlike past recessions, when the state had virtually no reserves and deep cuts were immediately necessary, the state’s reserves will cushion the coming budget crunch.

Consider Health and Economic Consequences When Evaluating Budget Solutions. In light of the current and future budget problems faced by the state, programmatic reductions will be needed as part of the overall budget solution. The Legislature likely will weigh multiple criteria when determining which solutions to implement. As one of those criteria, while the pandemic is ongoing, we recommend the Legislature consider whether the programmatic reduction under consideration could worsen the public health crisis or compound personal economic challenges facing Californians. Such actions include, for example, significantly reducing access to health care services or eliminating programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit. When possible, mitigating the effects of these types of reductions could help limit the impact of the virus and its negative implications for the state’s economy.

Upcoming Budget Process

Assessment of Budget Problem Reflects Our Best Estimates, Some Additional Information May Be Forthcoming in the May Revision. This report reflects our best estimates of the state’s budget situation given limited information and significant uncertainty. Much of this uncertainty surrounds the future path of the pandemic and the economy, which neither our office nor the administration can foresee with certainty. That being said, the May Revision may provide additional information on COVID‑19 costs and caseload effects of the deteriorating economic situation. Consequently, the May Revision should provide the Legislature additional information to assess the potential size of the budget problem and the extent to which policy interventions could mitigate that problem.

Start Making Hard Decisions in June Instead of Waiting Until August. The Legislature could pass a budget in June and then revisit these estimates in a subsequent budget package in August. This approach makes sense in light of the continuing evolving public health and economic situations. Regardless, under any scenario, the state will need to make some reductions in ongoing spending and we would strongly caution the Legislature against waiting until August to start making difficult decisions. Delaying action could only increase the size of the ultimate budget problem. Further, there are a number of areas of the budget for which midyear reductions are more difficult to implement. For instance, departments likely could respond to budget reductions more effectively if identified in June rather than in August.

Conclusion

After many years of favorable budgetary conditions, the state suddenly is facing a recession and a severely negative budgetary outlook. In this environment, lawmakers will face repeated—at times profoundly—difficult decisions. This will stand in stark and abrupt contrast to the budget surpluses of recent years. While the state and Governor have been appropriately focused on reacting to the current crisis, the upcoming budget process provides the Legislature with an important opportunity to assert its own priorities as the state moves forward on a long‑term fiscal plan.

A focus on the longer‑term budget situation—both in June and a possible package in August—is of serious import. Although the state faces a daunting budget deficit for the upcoming fiscal year, the multiyear situation is likely to be even worse. The Legislature should begin to craft multiyear actions now that help bring down the state’s ongoing budget deficits. Relying only on one‑time solutions in this budget cycle will mean significant budget problems reoccur year after year.

Appendix 1: How Do We Calculate the Budget Problem?

This Appendix describes our calculation of the budget problem in more detail.

Revenues and Other Resources Available Lower by $26 Billion to $39 Billion. Under both recession scenarios, our revenue estimates are tens of billions of dollars lower than the Governor’s budget estimates in January. In the U‑shaped scenario, revenues and other resources (specifically, the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties [SFEU]) are lower by $26 billion from 2018‑19 to 2020‑21. In the L‑shaped scenario, resources are lower by $39 billion across the same years. These revenue losses account for federal reimbursements from the state and federal disaster declaration (described in the next paragraph) and the estimated SFEU balance in the Governor’s budget.

COVID‑19 Response‑Related Spending. In a letter to the Joint Legislative Budget Committee in April, the administration estimated that the total costs of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) response will be $7 billion in 2020. Our baseline costs assume the state funds all of these costs in 2019‑20 and 2020‑21. Our revenue estimates assume that the federal government will ultimately reimburse the state for an estimated 75 percent of these costs—for total reimbursements of $5.25 billion—through 2020‑21.

Assume BSA Deposit Is Suspended in 2020‑21. As we describe in more detail in “Appendix 2,” under our revenue and economic estimates, the Governor could declare a fiscal emergency in 2020‑21, but not 2019‑20. The fiscal emergency declaration allows the state to suspend deposits into the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA). As such, we assume the BSA deposit is not suspended for 2019‑20, but is suspended for 2020‑21. Including the other required adjustments, compared to January estimates, required BSA deposits would be lower by $2.4 billion in the U‑shaped recession and $2.8 billion in the L‑shaped recession.

Assume Cost‑Adjusted 2019‑20 Funding for Schools and Community Colleges. To estimate the budget problem under the two scenarios, we assume the state funds schools and community colleges in 2020‑21 at the enacted 2019‑20 level, adjusted for inflation and attendance. Essentially, this estimate accounts for the “current service level” of K‑14 education rather than the constitutional minimum level. (This is similar to the approach we used for other programs in the state budget. As we describe later, funding K‑14 education at the constitutional minimum level would result in substantially lower General Fund costs.) From 2018‑19 to 2020‑21, General Fund spending on K‑14 education would be $2.4 billion lower than the Governor’s January budget level in the U‑shaped recession and $2.3 billion lower in the L‑shaped recession. The difference between the two scenarios results from differing assumptions regarding property tax revenue.

Account for Higher Federal Funding for Enhanced Federal Medical Assistance Percentage. Medicaid is an entitlement program whose costs generally are shared between the federal government and states. Congress recently approved a temporary 6.2 percentage point increase in the federal government’s share of cost for state Medicaid programs until the end of the national public health emergency declaration. We estimate this change results in General Fund savings of $4.1 billion for Medi‑Cal, $1.2 billion for In‑Home Supportive Services, and $560 million for some developmental services programs across 2019‑20 and 2020‑21 in the U‑shaped recession scenario and slightly more savings in the L‑shaped recession scenario. These estimates are based on our projections of caseload and the cost of services in these programs over the next 14 months, using assumptions based on our two economic and public health scenarios. (Importantly, these assumptions include the national public health emergency lasting beyond the 2020‑21 fiscal year in both scenarios.)

Remove All Discretionary Proposals From January Budget. The Governor’s proposed January budget estimated the state would have a moderate surplus for 2020‑21. (The “surplus” is defined as non‑Proposition 98 General Fund expenditures that are not required under current law or other policies.) The Governor proposed allocating that surplus to a variety of new spending proposals. (These proposals included, for example, funds for homelessness, expanded healthcare access, and environmental projects.) Under our definition of the baseline budget, these new proposed augmentations are not part of current services. Removing these proposals would reduce costs by $3.8 billion in 2020‑21.

Other Spending Slightly Lower. On net, we estimate that other costs across the budget will be lower by $225 million in the U‑shaped scenario and $299 million in the L‑shaped scenario. The reason other spending is lower in the L‑shaped scenario is that the state’s constitutionally required spending on debt payments is lower in those revenue assumptions.

Appendix 2: Using the BSA in 2020‑21

The budget has a few general purpose reserve accounts. The largest of these is the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA), which is governed by constitutional rules under Proposition 2 (2014). Here, we describe the rules around how the BSA can be used and how much of the BSA could be accessed to address a budget problem in 2020‑21.

Components of the BSA

BSA Has Optional and Mandatory Components. The total BSA in both the U‑shaped and L‑shaped recession scenarios has a component that is “mandatory” because it was deposited pursuant to the rules under Proposition 2, and a remaining “optional” balance that was deposited in some other way. In particular, these optional amounts include: (1) $1.6 billion deposited before Proposition 2 was enacted, (2) an optional deposit from the 2016‑17 budget that now totals $1.5 billion after adjustments, and (3) an optional deposit from the 2018‑19 budget that is now close to zero (see Appendix 2, Figure 1).

Appendix 2, Figure 1

Balance of the Budget Stabilization Account by Scenario

(In Billions)

|

U‑Shaped Scenario |

L‑Shaped Scenario |

|

|

Pre‑Proposition 2 balance |

$1.6 |

$1.6 |

|

2016‑17 optional deposit |

1.5 |

1.5 |

|

2018‑19 optional deposit |

— |

0.1 |

|

Optional Balance |

$3.1 |

$3.2 |

|

Mandatory balance |

$12.5 |

$12.1 |

|

Total Balance |

$15.6 |

$15.3 |

Is a Fiscal Emergency Available?

Legislature Can Make a BSA Withdrawal Under Two Conditions. The Legislature can suspend a BSA deposit or make a withdrawal from the mandatory share of the BSA if the Governor declares a budget emergency. The Governor may call a budget emergency in two cases: (1) if estimated resources in the current or upcoming fiscal year are insufficient to keep spending at the level of the highest of the prior three budgets, adjusted for inflation and population (a “fiscal budget emergency”) or (2) in response to a natural or man‑made disaster.

Fiscal Emergency Available in 2020‑21. Under our revenue scenarios, a fiscal emergency is available in 2020‑21, but not in 2019‑20, as Appendix 2, Figure 2 shows. Consequently, the BSA cannot be used to cover shortfalls in 2019‑20 under this provision. However, we think the Governor could declare a budget emergency in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 public health emergency in 2019‑20.

Appendix 2, Figure 2

Fiscal Emergency Likely Available in 2020‑21, But Not in 2019‑20

(In Millions)

|

U‑Shaped Scenario |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|

Highest adjusted budgeta |

$144,192 |

$146,049 |

|

Resources available |

148,190 |

136,962 |

|

Budget emergency available? |

No |

Yes |

|

Amount of Emergency |

|

$9,087 |

|

L‑Shaped Scenario |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|

Highest adjusted budgeta |

$144,192 |

$143,294 |

|

Resources available |

147,020 |

123,778 |

|

Budget emergency available? |

No |

Yes |

|

Amount of Emergency |

|

$19,516 |

|

aReflects the highest of the prior three budgets (2017‑18, 2018‑19, and 2019‑20), adjusted for inflation and population. In both cases, the highest of these is the 2019‑20 adjusted budget. |

||

How Much of the BSA Can the Legislature Use in 2020‑21?

Good Argument That the Legislature Can Access Optional BSA Balance by Majority Vote. Although not yet tested, we think there is a good argument that the balance of the BSA that was deposited on an “optional” basis is not subject to the withdrawal rules governing the mandatory balance. (Statutory language does indicate that nearly half of the optional total would be subject to rules, but this language can be amended by majority vote.) As such, under this argument, the Legislature could appropriate around $3 billion from the BSA by majority vote and without a fiscal emergency declaration by the Governor.

State Can Access Half of Mandatory Total. In the case of a fiscal emergency, the Legislature may only withdraw the lesser of: (1) the amount of the budget emergency, or (2) 50 percent of the BSA balance. (The second requirement is waived if the Legislature has accessed the BSA in the immediately preceding fiscal year. It is not clear whether withdrawing the funds for a disaster‑related purpose fulfills this requirement.) In both economic scenarios, the amount of the budget emergency exceeds 50 percent of the mandatory balance of the BSA. As such, in 2020‑21, there would be around $6 billion available from half of the BSA’s mandatory balance.

Likely Around $9 Billion in BSA Available in 2020‑21.The total amount available would be $9.2 billion to $9.4 billion, depending on the revenue scenario, as shown in Appendix 2, Figure 3. This said, there is an argument that if the Governor declared a budget emergency in 2019‑20 pursuant to the disaster declaration and the Legislature withdraws funds for that year, the entire remaining balance could be accessed for 2020‑21.

Appendix 2, Figure 3

BSA Balance Available in 2020‑21

(In Billions)

|

U‑Shaped Scenario |

L‑Shaped Scenario |

|

|

Optional balance |

$3.1 |

$3.2 |

|

Half of mandatory balance |

6.3 |

6.1 |

|

BSA Available |

$9.4 |

$9.2 |

|

BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

||

Appendix 3: Figures

Appendix 3, Figure 1

LAO Spring Outlook Revenue Estimates

(In Billions)

|

2018‑19 |

January Budget |

LAO Spring Outlook |

Change From January |

|||

|

U‑Shaped Scenario |

L‑Shaped Scenario |

U‑Shaped Scenario |

L‑Shaped Scenario |

|||

|

Personal income tax |

$98.6 |

$98.5 |

$98.5 |

‑$0.1 |

‑$0.1 |

|

|

Sales and use tax |

26.1 |

26.1 |

26.1 |

— |

— |

|

|

Corporation tax |

14.1 |

14.1 |

14.1 |

— |

— |

|

|

Subtotal, Big Three Revenues |

($138.8) |

($138.8) |

($138.8) |

(—) |

(—) |

|

|

BSA transfer |

‑$3.2 |

‑$3.2 |

‑$3.3 |

‑$0.1 |

‑$0.2 |

|

|

Federal cost recovery |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

|

All other revenues |

5.0 |

5.0 |

5.0 |

— |

— |

|

|

All other transfers |

‑1.3 |

‑1.3 |

‑1.3 |

— |

— |

|

|

Total Revenues and Transfers |

$139.4 |

$139.3 |

$139.2 |

‑$0.1 |

‑$0.2 |

|

|

2019‑20 |

January Budget |

LAO Spring Outlook |

Change From January |

|||

|

U‑Shaped Scenario |

L‑Shaped Scenario |

U‑Shaped Scenario |

L‑Shaped Scenario |

|||

|

Personal income tax |

$101.7 |

$98.9 |

$97.7 |

‑$42.8 |

‑$4.0 |

|

|

Sales and use tax |

27.2 |

24.3 |

24.3 |

‑2.8 |

‑2.9 |

|

|

Corporation tax |

15.3 |

13.1 |

13.1 |

‑2.2 |

‑2.2 |

|

|

Subtotal, Big Three Revenues |

($144.2) |

($136.4) |

($135.2) |

(‑$7.8) |

(‑$9.0) |

|

|

BSA transfer |

‑$2.1 |

‑$1.6 |

‑$1.2 |

$0.4 |

$0.9 |

|

|

Federal cost recovery |

1.0 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

|

|

All other revenues |

5.2 |

5.3 |

5.3 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

|

All other transfers |

‑1.9 |

‑1.9 |

‑1.9 |

— |

— |

|

|

Total Revenues and Transfers |

$146.5 |

$140.3 |

$139.5 |

‑$6.2 |

‑$6.9 |

|

|

2020‑21 |

LAO Spring Outlook |

Change From January |

||||

|

January Budget |

U‑Shaped Scenario |

L‑Shaped Scenario |

U‑Shaped Scenario |

L‑Shaped Scenario |

||

|

Personal income tax |

$102.9 |

$89.0 |

$81.3 |

‑$13.9 |

‑$21.6 |

|

|

Sales and use tax |

28.2 |

23.9 |

21.3 |

‑4.4 |

‑6.9 |

|

|

Corporation tax |

16.0 |

9.7 |

7.8 |

‑6.3 |

‑8.2 |

|

|

Subtotal, Big Three Revenues |

($147.1) |

($122.6) |

($110.4) |

(‑$24.5) |

(‑$36.8) |

|

|

BSA transfer |

‑$2.0 |

— |

— |

$2.0 |

$2.0 |

|

|

Federal cost recovery |

0.9 |

$5.1 |

$5.1 |

4.2 |

4.2 |

|

|

All other revenues |

5.4 |

5.0 |

4.9 |

‑0.4 |

‑0.6 |

|

|

All other transfers |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

— |

— |

|

|

Total Revenues and Transfers |

$151.6 |

$132.9 |

$120.5 |

‑$18.8 |

‑$31.2 |

|

|

BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

||||||

Appendix 3, Figure 2

LAO Spring Outlook Economic Assumptions

Annual Percent Change Unless Otherwise Indicated

|

U‑Shaped Scenario |

||||

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|

|

Personal income |

4.8% |

‑2.9% |

0.6% |

5.6% |

|

Wages and salaries |

5.2 |

‑5.2 |

‑1.0 |

4.7 |

|

Wage and salary employment |

1.5 |

‑6.4 |

‑1.6 |

3.0 |

|

Unemployment rate (percent) |

4.0 |

9.4 |

9.5 |

7.5 |

|

Housing permits (thousands) |

111 |

79 |

102 |

115 |

|

Median home price |

1.6 |

2.0 |

‑0.7 |

3.5 |

|

California Consumer Price Index |

2.9 |

1.6 |

2.2 |

3.4 |

|

S&P 500 (level) |

2,913 |

2,624 |

2,675 |

3,068 |

|

L‑Shaped Scenario |

||||

|

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|

|

Personal income |

4.8% |

‑5.5% |

‑3.3 |

3.9% |

|

Wages and salaries |

5.2 |

‑8.2 |

‑4.0 |

2.4 |

|

Wage and salary employment |

1.5 |

‑9.1 |

‑1.8 |

2.1 |

|

Unemployment rate (percent) |

4.0 |

11.5 |

11.5 |

10.1 |

|

Housing permits (thousands) |

111 |

64 |

65 |

97 |

|

Median home price |

1.6 |

‑1.2 |

‑5.7 |

3.3 |

|

California Consumer Price Index |

2.9 |

1.3 |

0.5 |

2.5 |

|

S&P 500 (level) |

2,913 |

2,328 |

1,880 |

2,375 |

Appendix 3, Figure 3

LAO Spring Outlook Agency‑Level Expenditure Estimates

|

U‑Shaped Scenario |

L‑Shaped Scenario |

||||

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

||

|

Proposition 98a |

$55,342 |

$56,207 |

$55,378 |

$56,278 |

|

|

Agency Totalsb |

|||||

|

Legislative, Judicial, and Executive |

$6,442 |

$3,771 |

$6,442 |

$3,771 |

|

|

Business, Consumer Services, and Housing |

1,049 |

159 |

1,049 |

159 |

|

|

Transportation |

96 |

9 |

96 |

9 |

|

|

Natural Resources and Environmental Protection |

3,205 |

2,281 |

3,205 |

2,281 |

|

|

Health and Human Services |

40,219 |

42,180 |

40,243 |

42,404 |

|

|

Corrections and Rehabilitation |

12,813 |

12,806 |

12,787 |

12,800 |

|

|

Education |

17,681 |

15,770 |

17,681 |

15,738 |

|

|

Labor and Workforce Development |

186 |

125 |

186 |

125 |

|

|

Government Operations and General Government |

4,912 |

6,886 |

4,912 |

6,627 |

|

|

Capital Outlay |

493 |

91 |

493 |

91 |

|

|

Debt Servicec |

5,168 |

5,231 |

5,168 |

5,231 |

|

|

Total Expenditures |

$147,606 |

$145,517 |

$147,640 |

$145,517 |

|

|

aAssumes the state funds schools and community colleges at the enacted 2019‑20 level, adjusted for inflation and attendance. bExcluding Proposition 98, capital outlay, and debt service spending. cIncludes debt service on general obligation and lease revenue bonds. |

|||||

Appendix 3, Figure 4

Comparing Estimates of the Minimum Guarantee

(In Millions)

|

January Budget |

LAO Spring Outlook |

Change From January |

||||

|

U‑Shaped Scenario |

L‑Shaped Scenario |

U‑Shaped Scenario |

L‑Shaped Scenario |

|||

|

2018‑19 |

$78,448 |

$78,508 |

$78,508 |

$61 |

$61 |

|

|

General Fund |

54,505 |

54,493 |

54,493 |

‑12 |

‑12 |

|

|

Local property tax |

23,942 |

24,015 |

24,015 |

73 |

73 |

|

|

2019‑20 |

$81,573 |

$78,328 |

$77,846 |

‑$3,245 |

‑$3,727 |

|

|

General Fund |

56,405 |

53,370 |

52,926 |

‑3,035 |

‑3,479 |

|

|

Local property tax |

25,168 |

24,958 |

24,921 |

‑210 |

‑248 |

|

|

2020‑21 |

$84,048 |

$73,884 |

$69,100 |

‑$10,164 |

‑$14,948 |

|

|

General Fund |

57,573 |

48,031 |

43,318 |

‑9,542 |

‑14,255 |

|

|

Local property tax |

26,475 |

25,853 |

25,782 |

‑622 |

‑693 |

|

|

Three‑Year Totals |

$244,069 |

$230,720 |

$225,455 |

‑$13,349 |

‑$18,614 |

|

|

General Fund |

168,484 |

155,893 |

150,737 |

‑12,590 |

‑17,747 |

|

|

Local property tax |

75,586 |

74,827 |

74,718 |

‑759 |

‑868 |

|

Appendix 3, Figure 5

Comparing Costs of Existing K‑14 Programs With the Proposition 98 Guarantee

(In Millions)

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

Three‑Year Totals |

|

|

Costs of existing programs |

$78,508 |

$80,300 |

$82,060a |

$240,868 |

|

U‑Shaped Scenario |

||||

|

Minimum guarantee |

$78,508 |

$78,328 |

$73,884 |

$230,720 |

|

Difference from existing program costs |

— |

1,972 |

8,176 |

10,148 |

|

L‑Shaped Scenario |

||||

|

Minimum guarantee |

$78,508 |

$77,846 |

$69,100 |

$225,455 |

|

Difference from existing program costs |

— |

2,454 |

12,960 |

15,413 |

|

aReflects cost of maintaining programs funded in the 2019‑20 budget plan, adjusted for changes in attendance, and the statutory cost‑of‑living adjustment (2.31 percent in 2020‑21). |

||||