LAO Contact

May 17, 2020

The 2020-21 May Revision

The 2020‑21 Budget

Initial Comments on the Governor's

May Revision

Updated May 19, 2020

- Overview of Budget Condition

- How Does the Administration Solve the Budget Problem?

- LAO Comments

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

Administration Estimates State Faces $54.3 Billion Budget Problem. The administration’s estimate of the budget problem is the result of a combination of factors. Most notably, it anticipates revenues will be lower across 2018‑19, 2019‑20, and 2020‑21 by $41 billion. The administration also anticipates the budget will face higher costs in direct response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) public health emergency and indirect costs in light of worsening economic conditions.

Budget Assumes $8.6 Billion in Direct COVID‑19 Related Expenditures. State costs to respond to COVID‑19 span a number of program areas, including education, public health, homelessness, and corrections. One of the largest areas of proposed expenditures is a $2.9 billion COVID‑19 contingency fund that would be available to the administration to respond to the public health crisis.

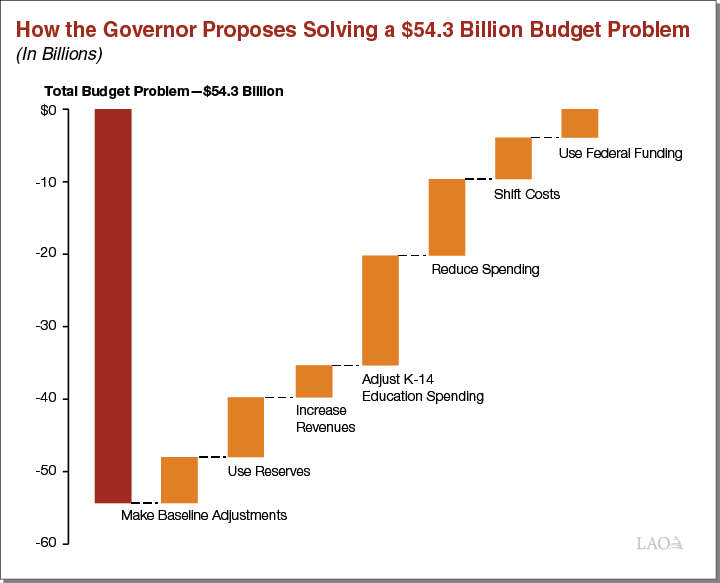

How Does the Administration Solve the Budget Problem? The Governor makes a number of proposed solutions across a wide range of areas to solve the budget problem. These solutions are summarized in the figure below. Of these solutions, roughly $15 billion would be unwound if sufficient federal assistance were provided.

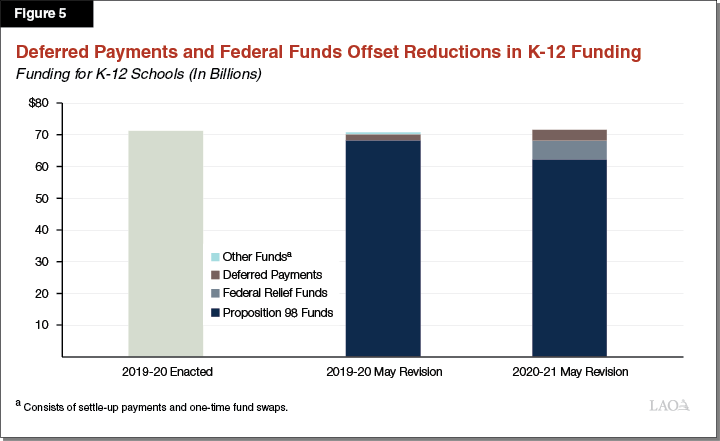

With Mitigating Actions, 2020‑21 School Funding Is Similar to 2019‑20 Levels. One of the program areas that the Governor uses to solve the budget problem is reducing General Fund spending on schools and community colleges to the minimum level required under the State Constitution. This action provides a budget solution of $15.2 billion. However, the Governor also proposes a number of mitigating actions—like payment deferrals and federal funding—that offset the effect of this reduction on school funding. After accounting for these mitigating actions, K‑12 funding is about flat on a year‑over‑year basis. In addition, the Governor proposes creating a new ongoing obligation for schools equal to 1.5 percent of General Fund revenues starting in 2021‑22.

LAO Comments. We conclude this report with our initial comments on this budget package. Our comments fall into a few different areas.

- Budget Solutions. The Governor takes a reasonably balanced approach in his proposed solutions without relying excessively on any one type of solution. While the Governor proposes some targeted spending reductions, others—like 10 percent reductions to universities and state employee compensation—are less targeted. We recommend the Legislature take a more surgical approach where possible.

- Multiyear Budget Condition. Although the state now faces a sizeable multiyear budget deficit, the Governor makes a serious effort to address this challenge. However, the Governor’s multiyear plan has some weaknesses. First, the proposal to create a significant, new ongoing obligation to schools contributes to the state’s multiyear operating deficit and limits future legislative flexibility. Second, some of the Governor’s cost shift proposals—specifically those on pensions—shift costs to future years and, in one case, could set a dangerous precedent.

- Federal Assistance. Along with the Governor, legislative leaders have already been pursuing new federal assistance, which is warranted. We suggest leaders request that such assistance be made flexible. However, even if new, flexible federal aid materializes, significant budget problems likely would reemerge in a few years. If the state receives significant federal aid, we would suggest the Legislature reconsider the structure of the budget in its entirety.

- Legislative Authority and Oversight. In a number of areas across the budget, the Governor makes proposals that raise serious concerns about the Legislature’s role in future decisions. We are very troubled by the degree of authority that the administration is requesting that lawmakers delegate. We urge the Legislature to resolutely guard its constitutional role and authority.

On May 14, 2020, Governor Newsom presented a revised state budget proposal to the Legislature. (This annual proposed revised budget is called the “May Revision.”) In stark contrast to the January budget proposal—which anticipated the state would have a surplus to allocate for 2020‑21—the public health emergency associated with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) pandemic and ensuing severe economic consequences have resulted in profoundly negative conditions for the upcoming budget.

In this report, we provide a summary of the Governor’s revised budget, focusing on the state’s General Fund—the budget’s main operating account. (In the coming days, we will analyze the plan in more detail and provide additional comments in hearing testimony and online.) We begin with an overview of the overall budget condition under the May Revision estimates and proposals. Then we describe the major actions the Governor took to close an estimated $54 billion budget gap. We conclude with our initial comments on this budget package.

The information presented in this report is based on our best understanding of administration actions as of Saturday, May 16, 2020. In many areas of the budget, our understanding of the administration’s proposals will continue to evolve as we receive more information.

Overview of Budget Condition

The Budget Problem

Administration Estimates State Faces $54.3 Billion Budget Problem. The administration estimates the state faces a budget problem of $54.3 billion relative to their January estimates. This is the result of a combination of factors. Most notably, it anticipates revenues will be lower across the budget window by $41 billion. The administration also anticipates the budget will face higher costs in both direct response to the COVID‑19 public health emergency and indirect response as caseload‑driven program costs are higher in light of worsening economic conditions. We describe these costs in more detail in the remainder of this section. (Earlier this month, our office estimated the budget problem would range between $18 billion and $31 billion depending on the severity of the economic recession. For more information about how the budget situation has changed since January see our LAO Spring Outlook.)

$8.6 Billion in Direct COVID‑19‑Related Expenditures. State costs to respond to COVID‑19 span a number of program areas, including education, public health, homelessness, and corrections. In addition to the roughly $2 billion in existing COVID‑19‑related expenditures the state has already incurred, we currently understand that the May Revision proposes additional direct COVID‑19 related spending in two categories:

- Additional Direct Response Expenditures of $3.5 Billion. We understand that the administration proposes an additional $3.5 billion in direct COVID‑19‑related expenditures. We have not yet received information about how the administration would spend this funding or which state departments would receive it.

- Unallocated COVID‑19‑Related Contingency Fund of $2.9 Billion. The administration also proposes the Legislature set aside $2.9 billion in a fund that the Governor could access for future COVID‑19‑related expenses. The administration has proposed using control section language to expend these funds for any purpose related to the COVID‑19 state of emergency with a 72‑hour notification to the Joint Legislative Budget Committee.

In total, under the May Revision, the state would spend $8.6 billion on direct COVID‑19‑related expenditures, as Figure 1 shows. Importantly, the administration assumes that the federal government ultimately will reimburse the state for an estimated 75 percent of these costs under the federal disaster declarations—meaning the net cost to the state would be $2.1 billion. (These reimbursements are reflected in the administration’s revenue estimates.)

Figure 1

Direct COVID‑19 Related Funding in the May Revision

(In Billions)

|

Amount |

|

|

Funding Already Expended |

|

|

Authorized under Control Section 36 |

$0.8 |

|

Authorized under DREOA |

1.4 |

|

Funding Proposed in the May Revision |

|

|

Direct responses expenditures (2019‑20) |

$2.1 |

|

Direct response expenditures (2020‑21) |

1.4 |

|

COVID‑19 contingency fund |

2.9 |

|

Total |

$8.6 |

|

COVID‑19 = coronoavirus disease 2019 and DREOA = Disaster Response‑Emergency Operations Account. |

|

Higher Costs Related to Caseload in Safety Net Programs. The administration anticipates caseload‑related costs across the state’s safety net programs—including Medi‑Cal, California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs), and CalFresh—to increase significantly. While we are still working to understand the administration’s estimates for these programs, they include a 9.2 percent year‑over‑year increase in Medi‑Cal enrollees, 51.1 percent increase in CalFresh participation, and an unprecedented 75.6 percent increase in CalWORKs participating families.

General Fund Condition

After Solutions, General Fund Would Have a Nearly $2 Billion Ending Balance. The Governor proposes $54.3 billion in solutions—which we describe in the next section—to balance the budget. After solutions, the General Fund would end 2020‑21 with an estimated $1.9 billion ending balance, shown as the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU) balance in Figure 2. (The enacted balance of the SFEU for the budget year cannot be below zero. This reserve generally is used for the state to respond to disasters, such as a fire, and provides a small buffer against some of the uncertainty inherent in budget estimates.)

Figure 2

General Fund Condition Under Governor’s May Revision

General Fund (In Millions)

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$11,280 |

$1,619 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

136,837 |

137,417 |

|

Expenditures |

146,497 |

133,902 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$1,619 |

$5,135 |

|

Encumbrances |

3,175 |

3,175 |

|

SFEU balance |

‑$1,556 |

$1,960 |

|

Reserves |

||

|

BSA balance |

$16,156 |

$8,350 |

|

SFEU |

—a |

1,960 |

|

Safety Net Reserve |

900 |

450 |

|

Totals |

$17,056 |

$10,760 |

|

aNegative SFEU excluded from total reserves balance. |

||

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties and BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

||

Administration’s Multiyear Budget Condition Reflects Continued Structural Deficit. In our Spring Fiscal Outlook, we noted that the state’s newly emergent fiscal challenges are unlikely to dissipate quickly and will extend well beyond the end of the public health crisis. This also is true in the administration’s multiyear budget projections, even after accounting for solutions proposed this year. Under its projections, the state would face a relatively small budget problem of around $5 billion in 2021‑22, growing to around $16 billion by 2023‑24.

How Does the Administration Solve the Budget Problem?

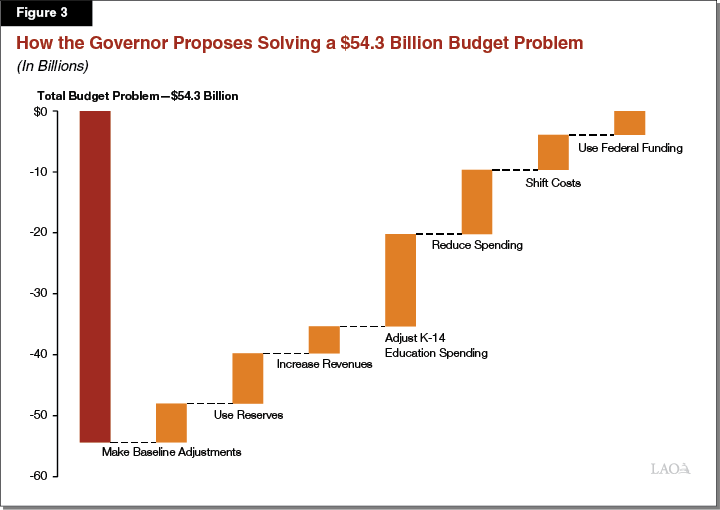

Figure 3 summarizes the budget solutions that this section describes in detail. Specifically, to solve the budget problem the Governor: (1) makes baseline adjustments, which do not involve choices about changes to current law (12 percent); (2) uses reserves (15 percent); (3) increases revenues (8 percent); (4) adjusts K‑14 education spending (28 percent); (5) reduces spending (19 percent); (6) shifts costs (11 percent); and (7) uses federal funds (7 percent). (Our categorization of these amounts is somewhat different than how the administration organized them.) Of the total, the administration proposes $15 billion in ongoing solutions (of this $8.1 billion are Proposition 98 General Fund). The ongoing solutions are entirely spending‑related.

Solutions Include $15 Billion Subject to Federal “Triggers.” The administration proposes making nearly $15 billion in one‑time and ongoing spending reductions subject to federal “trigger” language. Figure 4 shows more detail on the Governor’s proposed solutions, including those subject to the federal trigger. (Our estimate of the amount subject to the triggers differs from the administration’s figure somewhat because the administration’s total excludes one loan‑related item that is also contingent on the triggers.) Under the trigger language, if the federal government passes legislation that provides at least $14 billion in funding to the state, the administration would have authority to temporarily restore all of the programs that were reduced. We discuss the spending reductions subject to this provision in more detail below.

Figure 4

How the Administration Proposes Solving a $54.3 Billion Budget Problem

(In Billions)

|

Subject to Trigger |

Not Subject to Trigger |

Totals |

|

|

Make Baseline Adjustments |

|||

|

Account for higher federal Medicaid funding |

— |

$4.3 |

$4.3 |

|

Remove or modify January proposals |

— |

2.1 |

2.1 |

|

Use Reserves |

|||

|

Make BSA withdrawal |

— |

7.8 |

7.8 |

|

Make Safety Net Reserve withdrawal |

— |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

Increase Revenues |

|||

|

Suspend net operating losses |

— |

1.8 |

1.8 |

|

Limit business incentive tax credits |

— |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

Interaction between the two above items |

— |

0.6 |

0.6 |

|

Adjust K‑14 Education Spending |

|||

|

Provide funding at the minimum guarantee |

$8.1 |

7.1 |

15.2 |

|

Reduce Spending |

|||

|

Make flat 10 percent reductions |

3.6 |

1.4 |

4.9 |

|

Make targeted reductions |

2.3 |

3.2 |

5.6 |

|

Shift Costs |

|||

|

Make special fund loans |

0.9 |

2.0 |

2.9 |

|

Shift pension costs |

— |

1.7 |

1.7 |

|

Convert capital financing to lease revenue bonds |

— |

0.8 |

0.8 |

|

Transfer special fund balances |

— |

0.4 |

0.4 |

|

Use Federal Funding |

|||

|

Use Coronavirus Relief Fund |

— |

3.8 |

3.8 |

|

Use CCDBG funds |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

|

Totals |

$14.9 |

$39.4 |

$54.3 |

|

BSA = Budget Stabilization Account and CCDBG = Child Care and Development Block Grant. |

|||

Make Baseline Adjustments

There are two “baseline” adjustments to the Governor’s projection of the budget deficit. These are adjustments that do not require changes to current law to implement.

Receive $4.3 Billion in Federal Funding for Medicaid Programs. Congress recently approved a temporary 6.2 percent increase in the federal government’s share of cost for state Medicaid programs until the end of the national public health emergency declaration. We estimate the administration’s assumptions result in General Fund savings of $5.5 billion across three programs: Medi‑Cal, IHSS, and some developmental services programs. Of this, the administration scores $4.3 billion as budget solutions (the remainder offsets the budget problem in their baseline calculations).

Remove or Modify $2.1 Billion in January Proposals. The Governor’s proposed January budget estimated the state would have a moderate surplus for 2020‑21, which the Governor proposed allocating to a variety of new spending proposals. The Governor withdraws or modifies most of these proposals, reducing the budget problem. Based on information the administration provided to us, we estimate the associated savings of withdrawing or modifying these proposals is $2.1 billion, including roughly $900 million in ongoing savings.

Uses Reserves

Administration Proposes Withdrawing $8.3 Billion in Reserves. The state’s largest general purpose reserve is the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA), which is governed by constitutional rules under Proposition 2 (2014). The state also has the Safety Net Reserve, which was created to provide additional reserves for certain caseload‑driven programs. Under the administration’s estimates, the state would begin the 2020‑21 fiscal year with $17.1 billion across these two reserve accounts. The administration proposes using roughly half of that total to address the budget problem in 2020‑21.

$10.7 Billion in Reserves Would Remain at the End of 2020‑21. Under the administration’s estimates and proposals, the state would end 2020‑21 with $10.7 billion in reserves. This includes a balance of nearly $2 billion in the SFEU. The administration has a multiyear plan to use the remaining BSA and Safety Net reserves over three years—using about $6 billion in 2021‑22 and $3 billion in 2022‑23.

Increases Revenues

Increases Revenues by $4.4 Billion From Taxes on Businesses. The Governor’s budget solutions in the May Revision include two actions that the administration estimates would increase tax revenues by $4.4 billion in 2020‑21. They are:

- Suspend Net Operating Loss Deductions. Corporations that have net income over $1 million would not be allowed to use net operating loss (NOL) deductions to reduce their taxes in 2020, 2021, or 2022. When a corporation’s expenses exceed its revenue in a year, it generates a NOL equal to the amount by which their expenses exceed their revenues. The corporation can then deduct the NOL from its taxable income in subsequent years, reducing their taxes in those years.

- Limit Business Tax Credits. Businesses may not claim more than $5 million in tax credits per year in 2020, 2021, and 2022. Tax credits reduce a business’s tax bill directly, on a dollar‑for‑dollar basis. The largest business tax credit is the research and development credit.

In addition, the administration proposes two actions to increase sales tax compliance on used car purchases; however, they do not count these as budget solutions.

Adjusts School and Community College Spending

Budget Year

Reduces General Fund Spending to Minimum Level. Proposition 98 (1988) determines the minimum amount the state must spend on schools and community colleges each year through a combination of General Fund and local property tax revenue. The Governor’s estimates of General Fund revenue are down significantly over the 2018‑19 through 2020‑21 period, resulting in a drop to the minimum funding level for schools and community colleges. The Governor proposes to reduce funding to the lower level, resulting in General Fund savings of $16.5 billion. (The administration classifies about $15.2 billion of this total as “budget solution” related with the remaining difference largely the result of technical adjustments.) Local property tax revenues also drop by roughly $1 billion, resulting in a total Proposition 98 decrease of $17.5 billion.

With Mitigating Actions, 2020‑21 School Funding Is Similar to 2019‑20 Levels. To bring state spending down to the minimum guarantee, the May Revision includes $6 billion in reductions to existing K‑12 education programs (subject to the trigger reductions) and $5.3 billion in payment deferrals. (When the state defers payments to schools from one fiscal year to the next, the state can reduce spending while allowing school districts to continue operating a larger program by borrowing or using cash reserves.) Most of the remainder is associated with rescinding January proposals. The proposed programmatic reductions also are mitigated by $5.8 billion in one‑time federal funding for schools in 2020‑21. This amount includes $4.4 billion for districts to implement strategies to mitigate the effects of learning loss during school closures. The net fiscal effect of these proposed actions is shown in Figure 5. When accounting for these additional measures, K‑12 funding is about flat on a year‑over‑year basis, with federal funds and payment deferrals offsetting the reduction in Proposition 98 funding. (If the reductions are triggered off, overall funding would increase on a year‑over‑year basis.)

Community College Funding Set to Decline Despite Mitigating Actions. Of the $17.5 billion drop in the minimum guarantee, about $2 billion is attributable to the community colleges. The May Revision addresses this drop with $1 billion in cuts to community college programs (subject to the trigger reductions) and $662 million in payment deferrals, with the remainder largely associated with rescinding January proposals. (Typically a payment deferral does not impact programs.) In contrast to schools, federal relief funding allotted for community colleges is not a significant source of aid to offset state funding reductions for the colleges. Even with some mitigating actions (including the budget relief mentioned below), college funding per student still declines from 2019‑20 to 2020‑21.

Governor Also Proposes Supplanting Pension Payments for Schools and Community Colleges. The 2019‑20 budget included two supplemental pension payments—one to the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) and one to the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS)—that would reduce district pension contribution rates over the next few decades. Although subject to some uncertainty these payments could have yielded savings of more than $5 billion over the next few decades for school districts and more than $0.5 billion for community colleges. The Governor proposes repurposing these payments to supplant school and community college contributions to CalSTRS and CalPERS for 2020‑21 and 2021‑22. This would result in savings of around $2.1 billion for school districts and $0.2 billion for community colleges in 2020‑21 and 2021‑22, but would forgo the remaining savings over the next few decades.

Multiyear

Creates Supplemental Obligation to Increase School and Community College Funding. The May Revision proposes to create a new multiyear payment obligation to supplement the funding schools and community colleges receive under Proposition 98. The total obligation would be $13 billion—the administration’s estimate of the additional funding schools and community colleges would have received if their Proposition 98 funding had continued to grow in 2019‑20 and 2020‑21. The state would make annual payments toward this obligation beginning in 2021‑22. The payments would equal 1.5 percent of General Fund revenue and could be allocated for any school or community college program. The May Revision also proposes to recalibrate the Proposition 98 formulas so that a portion of these supplemental payments would increase school and community college funding on a permanent basis. Specifically, the state would increase the share of General Fund revenue required to be spent on schools and community colleges from 38 percent to 40 percent. (We estimate that this recalibration would make roughly the first $2.5 billion of the supplemental payments permanent.)

Reduces Spending

Proposes Flat Reductions Resulting in $4.9 Billion in Lower Spending. The Governor proposes a number of flat reductions across programs or rates in a few different areas. First, in three program areas—universities, judicial branch, and employee compensation—the Governor proposes making a flat, 10 percent reduction. (The Governor also proposes similar reductions in other areas of the budget, but the associated savings are smaller.) For example, for General Fund support to both university systems, the Governor withdraws his January proposal to provide a 5 percent base increase and then makes a 10 percent reduction. (In this case, the former is not part of the “trigger” reduction, but the latter is.) Second, the Governor proposes flat rate cuts for the Department of Developmental Services and child care. Third, the Governor anticipates savings of $900 million in 2020‑21 across a variety of departments from unspecified efficiencies. Overall, these reductions result in $4.9 billion in savings (of which $3.6 billion is subject to the triggers).

Proposes Targeted Reductions Totaling $5.6 Billion. In program areas across the rest of the budget, the Governor proposes making targeted reductions to certain programs or benefit levels. For example, the Governor proposes reverting a number of augmentations planned in 2019‑20, such as $200 million for the infill infrastructure development grant program for housing and $300 million for kindergarten facilities grants. Overall, these targeted reductions result in $5.6 billion in savings (of which $2.3 billion is subject to the triggers).

Shifts Costs

Makes $3.3 Billion in Special Fund Loans and Transfers. In past recessions, the state made loans from other state accounts, known as special funds, to the General Fund to address budget problems. The administration proposes making $2 billion in loans from 57 separate special funds to the General Fund. Over 90 percent of these loans are less than $100 million. The administration also proposes control section language that would lend special fund savings from lower employee compensation in 2020‑21 to the General Fund. The administration estimates this would yield about $1 billion in loans. (We count these as a trigger reduction because the employee compensation reductions are tied to the triggers.) Finally, the administration proposes transferring about $400 million in special fund balances to the General Fund—amounts that would not be repaid.

Shifts $1.7 Billion in Pension‑Related Costs. The Governor makes a few pension‑related proposals that shift costs. First, the 2019‑20 budget made a supplemental pension payment of $2.5 billion to CalPERS. The state would have realized savings over the next few decades, eventually resulting in an estimated gross savings of $5.9 billion. The Governor proposes repurposing this supplemental payment to supplant state General Fund contributions to CalPERS this year. This would result in savings of $2.4 billion, which the administration scores over multiple years including 2021‑22. However, it means the state would forgo the remaining savings over the next few decades. Second, the Governor proposes suspending CalSTRS’ ability to increase the state’s contribution rate from 2020‑21 to 2023‑24. Currently, CalSTRS can only increase (or decrease) the state’s rate by 0.5 percent per year (equivalent to $169 million in 2020‑21). Instead, the administration proposes to provide offsetting payments using other required debt payments. Finally, the administration proposes eliminating a $265 million supplemental payment to CalPERS planned for 2020‑21 under current law and shifting a $243 million pension payment to Proposition 2 debt payments.

Shifts Roughly $800 million in Costs to Lease Revenue Bonds (LRBs). Recent budgets have set aside General Fund monies to pay for some capital outlay projects. For example, the state has set aside nearly $1 billion in the State Project Infrastructure Fund for the renovation of the State Capitol Annex and the construction of a new office building near the State Capitol. The Governor proposes converting this and other projects to LRB financing. Under this proposal, the state would borrow from the bond market to pay the upfront costs of these projects and then repay those bonds with interest over time. This results in savings of roughly $800 million in 2020‑21, but higher debt service costs over time.

Uses Federal Funds

Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) Provides Funding for COVID‑19‑Related Expenditures. Congress recently established the CRF to provide money to state, local, tribal, and territorial governments for “necessary expenditures incurred due to the public health emergency with respect to the Coronavirus Disease 2019” that are incurred between March 1 and December 30, 2020. California’s state government is eligible for $9.5 billion from the CRF. Guidance from the U.S. Department of the Treasury outlines the eligible uses of these funds.

Administration Proposes Using $3.8 Billion in CRF to Address Budget Problem. The May Revision assumes the state can use $3.8 billion of the total CRF funding to offset underlying state costs. This includes $2.6 billion to address increased CalWORKs caseload from March 1 to December 30, 2020, $750 million for homelessness, and $405 million in other areas such as public safety and public health. (We currently have very little information about what is included in the final category.) The administration proposes to remit the remaining CRF funds to schools ($4 billion), counties ($1.3 billion), and cities ($450 million).

LAO Comments

Budget Solutions

Mix of Solutions Reasonably Well‑Balanced. In our Spring Fiscal Outlook, we recommended the Legislature use a mix of all the tools at its disposal to solve the 2020‑21 budget problem. The Governor has taken this approach, using a balanced mix of proposed solutions across a variety of types and areas. Doing this, the Governor does not rely excessively on any one type of solution. We recommend the Legislature take a similar approach, asserting its own priorities, as it constructs the state’s budget.

Proposed Revenue Solutions Are a Reasonable Starting Point for Deliberations, but Have Limitations. Should the Legislature wish to include revenue actions in its mix of solutions, the May Revision proposals are worth consideration. The state suspended NOLs and limited business tax credits during prior recessions. These actions generally are considered somewhat less burdensome on taxpayers than other actions like increasing tax rates. This is because they largely would change the timing of tax payments (causing payments to be made sooner than they otherwise would) but would not significantly increase the total amount of taxes businesses pay over the next several years. That being said, the proposed actions also have some drawbacks. Most importantly, predicting the amount of revenue generated from these solutions is more difficult than some alternatives due to the inherent complexity of corporation tax filings. Counting on a certain amount of revenues from these solutions to fix the budget problem is somewhat risky. Compounding this risk, our preliminary review suggests that the administration’s estimates for the revenue solutions may be too high.

Some Spending Reductions Are Targeted, Others Less so. The Governor proposes spending reductions across a wide array of program areas. (Many of these reductions would be temporarily “triggered off” in the event of more federal assistance.) In many cases, the Governor takes a targeted approach to reductions. In some of these cases, the Governor’s proposals avoid compounding the public health crisis or associated personal economic challenges facing Californians. For example, the Governor does not reduce CalWORKs grants or recent expansions to the Earned Income Tax Credit. The Governor also proposes targeted and relatively limited reductions to Medi‑Cal and corrections. In other areas, however, the Governor proposes blunter reductions. For example, the Governor proposes a flat 10 percent reduction to universities, judicial branch, and state employee compensation. While significant reductions are necessary given the severity of the budget crisis, we recommend the Legislature take a more surgical approach where possible. In the coming days and weeks, we will help identify alternative solutions where available.

Multiyear Budget Condition

Governor Makes Progress in Addressing Multiyear Condition... Similar to our office, the administration’s multiyear budget projections reflect continued economic and budgetary pain for the state. Nonetheless, by proposing a number of ongoing reductions, the Governor makes choices that reduce the ongoing budget gap. Some of these choices—like closing two prisons in the near future—are prudent given the circumstances. Other decisions—like reductions to programs and services—are painful but necessary to close the budget’s multiyear deficits. We support the Governor’s decision to make ongoing solutions a key feature of his proposed budget and urge the Legislature to take a similar approach. In particular, the Governor’s May Revision includes $15 billion in ongoing solutions—we recommend the ultimate budget package include no less than this amount.

…But Creates Significant New, Ongoing Obligation. Under the administration’s current projections, the supplemental payments to schools and community colleges would total $10.1 billion over the 2021‑22 through 2023‑24 period. (Of this amount, $5.7 billion is related to the 1.5 percent payments and $4.4 billion is related to recalibrating the Proposition 98 formulas.) These payments contribute directly to the state’s multiyear operating deficit, making it even more difficult for the Legislature to balance future budgets. In addition, the existing Proposition 98 formulas provide for increases in school funding tied to growth in General Fund revenue and local property tax revenue. Under the administration’s revenue assumptions, Proposition 98 would already require increases in per‑pupil funding averaging 5 percent per year over the multiyear period, while still requiring reductions to much of the rest of the budget. If the Legislature wishes to provide schools with additional funding beyond this level, it could make that decision as part of annual budget deliberations. Enacting a new formula limits legislative discretion and flexibility.

Pension Proposals Also Shift Costs to Future Years. As we described earlier, the Governor makes pension‑related proposals that achieve short‑term savings but result in higher costs in the future. Given the magnitude of the budget problem, some degree of cost shifts are tolerable. However, the plan to suspend increases to the state’s CalSTRS rate is short‑sighted and weakens the funding plan adopted in 2014. Unlike with CalPERS, which can require the state to make certain payments, CalSTRS’ authority is much more limited. Reducing CalSTRS’ statutory authority to raise rates now sets a dangerous precedent for future years, opening the door to further changes that could erode the health of the system.

Continuing to Seek More Federal Assistance Warranted... The extent of the budget problem identified not only for 2020‑21, but also future years, is substantial. Without federal assistance, the Governor proposes the state make sizeable and ongoing reductions to education, health and human services, state employee compensation, and many other areas. Moreover, while reserves and other budgetary maneuvers can mitigate these reductions in the near term, additional reductions will be necessary in future years. Along with the Governor, legislative leaders have already been pursuing new federal assistance, which is warranted. We suggest leaders request that any assistance made available be flexible. Given the significant ongoing effects of this crisis, the state requires assistance that can be used to address not only this year’s budget deficit, but also future deficits that will result from continued economic and budgetary hardship as a result of the COVID‑19 public health emergency.

...But Budget Structure Would Still Need to Be Reconsidered if Federal Assistance Materialized. As noted earlier, the Governor’s May Revision would undo the majority of ongoing spending reductions if additional federal assistance were received. Even if flexible funding materializes, however, it likely would only be available for a year or two. Consequently, significant budget problems likely would reemerge in a few years. Should additional federal assistance become available, we suggest the Legislature reconsider the structure of the budget using all available tools. Doing so would allow the state to phase in spending reductions more slowly, mitigating the negative economic consequences of pulling back spending too quickly.

Legislative Authority and Oversight

Governor Continues to Propose Significant Policy Changes That Require More Time for Legislative Consideration. In addition to budgetary actions, the Governor’s January budget proposal included a number of accompanying changes to policy. While some have been amended or withdrawn, the Governor continues to propose a number of these policy changes in the May Revision. This includes, for example, a number of proposals to create new or reorganize existing state departments—such as the Department of Business Oversight and the Department of Better Jobs and Higher Wages. Given the Legislature’s reduced capacity to hold hearings in recent months, lawmakers have not had time to carefully consider these proposals. The Governor now asks that the Legislature examine and approve these changes—alongside a complicated and difficult budget—in a compressed period of time. We recommend the Legislature defer some of these choices and consider them instead in the policy process or in the next budget cycle.

Several Administration Proposals Sideline Legislative Authority. In a number of areas across the budget, the Governor makes proposals that raise serious concerns about the Legislature’s role in future decisions. This includes, for example, the Governor’s creation of a new COVID‑19 contingency fund and a number of examples of budget bill language that delegate increased authority to the administration. In some cases, we have received only limited information about how the proposals would be implemented. In many cases, we are very troubled by the degree of authority that the administration is requesting that the Legislature delegate.

Conclusion

The Governor has presented a budget to the Legislature that addresses a $54.3 billion budget problem. Despite the state’s historic reserve levels and good budgetary position entering the recession, the dramatic change in the state’s economic circumstances has already meant the state must make difficult decisions. In response, the Governor has presented a plan that puts forward a balanced mix of solutions and makes a serious effort to address the state’s ongoing budgetary challenges. Nonetheless, the budget plan has some weaknesses, which we suggest the Legislature address as it adopts the fiscal plan for the state. However, perhaps more importantly, in a number of areas across the budget, the administration asks that the Legislature delegate significant authority to the executive branch. In these cases, we urge the Legislature to jealously guard its constitutional role and authority.