LAO Contact

January 27, 2021

Update on Community College Reserves

With the onset on the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic in California, all California Community Colleges (CCC) shifted to remote operations in March 2020. In this post, we compare local reserve levels as of June 30, 2020—a few months after the shift to remote operations—with reserve levels in preceding years. We focus on local reserve levels because they are a key indicator of the overall fiscal health of community colleges. Below, we first provide background on community college reserve policies, then share data on reserve levels.

Reserve Policies

Colleges Maintain Reserves for Multiple Reasons. Local reserve levels are an important factor that oversight bodies and credit-rating agencies use to assess local governments’ fiscal health. For community colleges, the CCC Chancellor’s Office and the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges routinely monitor local college reserve levels. Local reserves are critical for several reasons. Local reserves allow community colleges (as they do other local agencies) to sustain their operations even if their annual funding drops due to economic recessions. Local reserves also allow colleges to handle lower-than-budgeted local property tax receipts or unexpected drops in enrollment. Additionally, local reserves help colleges manage their cash flow and pay their bills while awaiting receipt of funds. Local reserves can be especially helpful during times when the state is deferring payments, as colleges might not receive their state funding until many months after they have incurred operating costs. Reserves help too in covering unexpected costs. For example, since campuses moved to remote operations, they have incurred higher technology and professional development costs. Though campuses in some cases ultimately might be reimbursed for certain costs, they might need to cover costs upfront. Colleges also use reserves to pay for large, planned, one-time purchases (such as a large-scale upgrade of instructional equipment).

Colleges Hold Both “Unrestricted” and “Restricted” Reserves. In this post, we examine both unrestricted and restricted reserve levels. The bulk of local and state funding supporting the CCC system is unrestricted—meaning that colleges may use the funding for any educational purpose. In contrast, some state funding, most federal funding (which is a smaller fund source for colleges relative to local and state funding), and fee revenue is restricted—meaning that colleges are required to use that funding for specific purposes, such as student financial aid, veteran resource centers, or parking. Reserves typically must be used consistent with the associated funds’ original purposes. Unrestricted reserves thus are available for any education purpose, whereas restricted reserves are available only for program-specific purposes.

Chancellor’s Office Provides Systemwide Guidance on Colleges’ Unrestricted Reserves. State law does not specify a minimum or maximum level of reserves (either unrestricted or restricted) for community college districts. Instead, state law directs the Chancellor’s Office to develop standards relating to districts’ overall fiscal health. One of the standards developed by the Chancellor’s Office is that a community college district have unrestricted reserves equivalent to at least 5 percent of its annual unrestricted expenditures. A few times each year, the Chancellor’s Office reviews each district’s unrestricted reserve level (along with several other factors, including salaries and benefits as a share of the total operating budget and changes in enrollment). The Chancellor’s Office does not have systemwide guidance on restricted reserves—specifying neither an expected minimum nor maximum level.

Many Colleges Locally Adopt Higher Unrestricted Reserve Standards. The state does not require local community college governing boards to adopt local reserve policies, and the state does not regularly collect information about local reserve policies. To collect information about these policies, we reached out to 15 districts. The 15 districts we contacted were spread across the state (with some in the southern, central, and northern regions) and varied in terms of their enrollment (with some small, medium, and large). They also varied in their reliance on state versus local funds. All but 1 of the 15 districts reported having a local unrestricted reserve policy. Two of the 15 districts had a local policy of holding unrestricted reserves of 5 percent of annual unrestricted expenditures, the same as the Chancellor’s Office’s systemwide guidance. All other districts had higher standards, with unrestricted reserve standards ranging from 7 percent to 20 percent of annual unrestricted expenditures. Five of the districts had local policies close to the minimum unrestricted reserve recommended by the Government Finance Officers Association. This association encourages local governments to hold a minimum unrestricted reserve equivalent to at least two months (or 17 percent) of annual operating expenditures. Districts tend not to have local restricted reserve policies that apply broadly across their categorical funds, as many of these funds exist, with many different purposes.

Reserve Levels

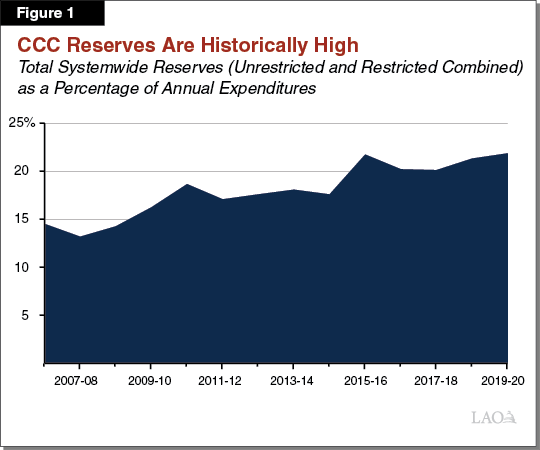

Systemwide Reserves Increased in 2019‑20. The CCC system consists of 73 districts and 116 college campuses. Of the 73 districts, 72 are governed by locally elected boards and 1 (the Calbright College District) is governed by the state Board of Governors. Total systemwide reserves (unrestricted and restricted combined) were $2.3 billion as of June 30, 2020—$117 million (5.3 percent) higher than a year earlier (at the end of 2018‑19). They were about double the level of ten years earlier. Systemwide reserves increased not only in dollar terms but also as a percentage of annual operating expenditures. As of June 30, 2020, systemwide reserves equated to 22 percent of annual operating expenditures, up about 0.5 percentage points from a year earlier. As Figure 1 shows, total reserves as a share of annual operating expenditures have been trending upward since 2007‑08. (We show data starting in 2006‑07—the year the Chancellor’s Office began compiling data separately for unrestricted and restricted reserves.)

Trend in Unrestricted Reserves Parallels That of Total Reserves. As of June 30, 2020, systemwide unrestricted reserves were $2 billion—$158 million (8.7 percent) higher than a year earlier and about double the level of ten years earlier. As of June 30, 2020, unrestricted reserves equated to 23 percent of annual unrestricted expenditures—up 1.2 percentage points from a year earlier. Unrestricted reserves as a share of annual unrestricted expenditures also have been trending upwards—from less than 15 percent in 2006‑07, 2007‑08, and 2008‑09 to more than 20 percent every year since 2015‑16.

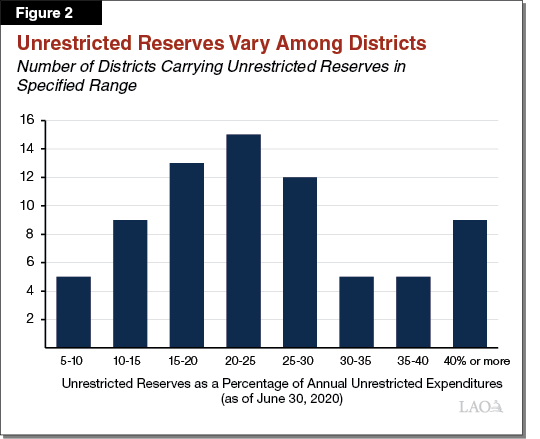

Colleges’ Unrestricted Reserves Vary Notably. As of June 30, 2020, all 73 community college districts were meeting the standard set by the Chancellor’s Office to have unrestricted reserves equivalent to at least 5 percent of their annual unrestricted expenditures. Unrestricted reserves ranged from 5.3 percent of annual expenditures at the San Francisco Community College District (CCD) to 58 percent at the Kern CCD, with a median unrestricted reserve of 23 percent. Figure 2 shows the distribution of districts’ unrestricted reserves as a percentage of annual expenditures as of June 30, 2020.

Various Reasons Colleges’ Unrestricted Reserve Levels Vary. Colleges’ local policies and unrestricted reserve levels are not tightly linked to their enrollment size or geography. Rather, their policies and unrestricted reserve levels tend to be more closely linked with the perspectives of their local governing boards. Boards that assess potential fiscal risks as high tend to carry higher unrestricted reserves. Boards facing greater salary and collective bargaining pressures tend to keep lower unrestricted reserves.

Unrestricted Reserves at Two-Thirds of Colleges Grew Over Last Year. Forty-eight districts had larger unrestricted reserves on June 30, 2020 compared to one year earlier. Of these districts, 11 had their unrestricted reserves grow by more than 10 percentage points over the year, whereas the remainder had smaller increases. Of the 25 districts that had declines in unrestricted reserves between June 2019 and June 2020, the vast majority had decreases of less than 10 percentage points. The two districts with decreases of more than 10 percentage points did not appear to be experiencing a major deterioration in their fiscal health. One of these districts, Calbright College, had particularly large reserves due to the state forward-funding its start-up activities (such that the drop in its reserves was expected). The other district, Palo Verde CCD, started (and ended) the year with relatively high unrestricted reserves—having its unrestricted reserves as a share of annual unrestricted expenditures drop from 52 percent as of June 30, 2019 to 36 percent as of June 30, 2020.

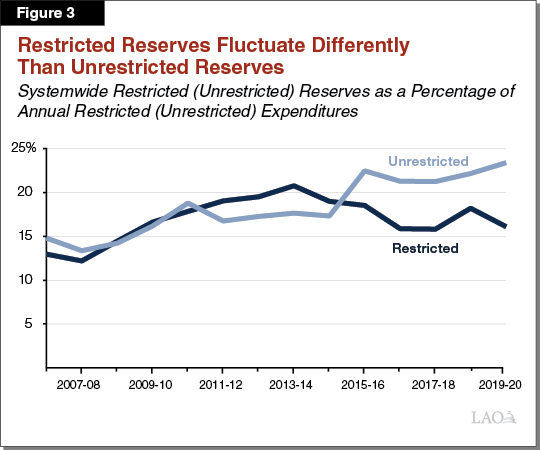

Restricted Reserves Dropped in 2019‑20. Unrestricted reserves comprise 85 percent of total systemwide reserves, with restricted reserves comprising 15 percent. In contrast to unrestricted reserves, systemwide restricted reserves dropped $41 million (10 percent) from June 30, 2019 to June 20, 2020—falling to $360 million. Restricted reserves fell from 18 percent of annual restricted expenditures to 16 percent. The pattern of colleges’ restricted reserves does not track closely with unrestricted reserves. Whereas unrestricted reserves grew gradually from 2006‑07 through 2019‑20, restricted reserves have experienced greater fluctuation. As Figure 3 shows, restricted reserves as a percentage of annual restricted expenditures saw some years of growth, followed by some years of decline. Though the Chancellor’s Office does not collect data on restricted reserves by program, reserves likely are larger for the larger categorical programs (including the Strong Workforce Program and Student Equity and Achievement Program).

Restricted Reserves at Nearly Half of Colleges Declined Over Last Year. From June 2019 to June 2020, 28 districts had increases in their restricted reserves as a share of annual restricted expenditures, whereas 35 districts had decreases. (Of the remaining ten districts, nine had no restricted reserves at the end of either of the past two fiscal years, and one district—Calbright—had no restricted expenditures.) Of the districts with decreases, seven had decreases of greater than 10 percentage points. Districts likely are drawing down these reserves to cover revenue declines in areas like parking due to campuses operating at reduced capacity. They also could be drawing down reserves in restricted programs that provide additional student and faculty support, as the need for such support likely has been amplified since the onset of the pandemic and shift to remote instruction.

Outlook Has Improved but Monitoring Colleges’ Fiscal Health Remains Important. Systemwide, community college reserves grew somewhat from June 2019 through June 2020. Since June 2020, the state’s fiscal outlook, as well as the Proposition 98 outlook for school and community college funding, has improved. Developments over just the past couple of months also bode well for community colleges. A second round of federal relief funding, which provides greater benefit to community colleges than the first round, was announced in late December 2020, with funds to begin arriving automatically to colleges over the next few weeks. In addition, the Governor submitted proposals in January to eliminate most community college payment deferrals and provide a cost-of-living adjustment to apportionment funding. For all these reasons, community colleges generally are not expected to experience a notable drop in their local reserves or major deterioration in their overall fiscal health throughout 2021‑22. The future of the pandemic, economy, and state revenues, however, remains uncertain, making continued fiscal oversight by the Chancellor’s Office as important as ever.