LAO Contact

Correction (2/18/2021): A previous version of this post stated DSS released a draft of the transition plan. This version is corrected to state DSS released a transition plan guide.

February 11, 2021

The 2021-22 Budget

Child Care Proposals

In this post, we analyze the Governor’s proposal to transition state administration of child care programs from the California Department of Education (CDE) to the Department of Social Services (DSS). We then provide background on how the pandemic has affected child care providers and families and provide options the Legislature could consider to support child care programs in the short term.

Transitioning State Administration of Child Care Programs

Background

State Subsidizes Child Care and Preschool, Primarily for Low‑Income Families. The state subsidizes child care and preschool through several programs, serving an estimated 415,000 children. The vast majority of children participate in programs currently administered by CDE, while DSS administers two programs.

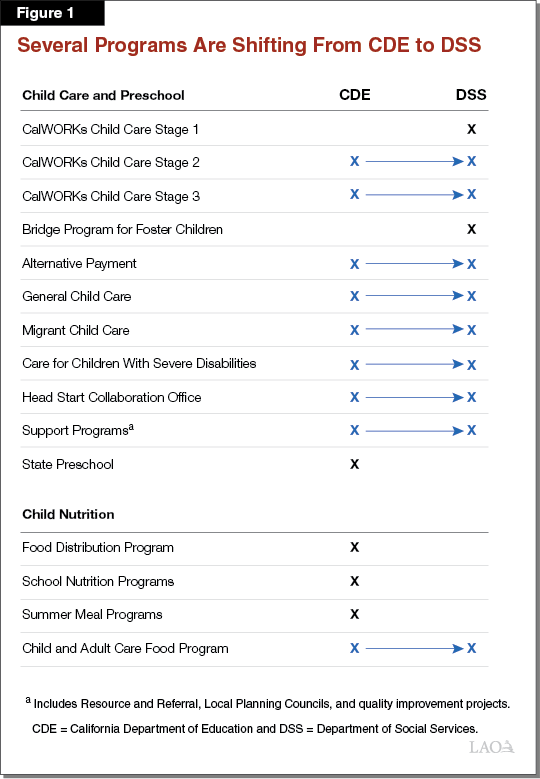

2020‑21 Budget Authorized the Transition of Child Care Programs and One Nutrition Program From CDE to DSS. Trailer legislation shifts administration of state child care programs and initiatives from CDE to DSS beginning July 1, 2021 (see Figure 1). Trailer legislation also shifts the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP) to DSS. State Preschool and other child nutrition programs will continue to be administered by CDE. The 2020‑21 budget provided DSS with $2 million one‑time General Fund to plan for the transition. Trailer legislation requires DSS to submit a transition plan to the Legislature by March 31, 2021. The plan is required to include answers to a number key questions, including how the shift will result in better services for children and families and what the ongoing cost of the shift will be. In February 2021, DSS released a transition plan guide, an overview document that responds at a high level to the key questions identified in statute.

Governor’s Proposal

Shifts $3 Billion in Local Assistance Funds for Child Care and Nutrition Programs. Consistent with the actions taken last June as part of the 2020‑21 budget package, the Governor’s budget proposes to shift $3 billion in local assistance from CDE to DSS. Figure 2 shows the programs and associated funding that would be shifted. Under the proposal, all of the state’s federal Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) funding would be allocated through DSS.

Figure 2

Governor’s Budget Shifts $3.1 Billion in Local Assistance to DSS

2021‑22 (In Millions)

|

Program Shifting |

General Fund |

Proposition 64 |

Federal Fund |

Total |

|

CalWORKs Child Care Stage 3 |

$397 |

— |

$278 |

$675 |

|

Alternative Payment Program |

181 |

$140 |

332 |

654 |

|

General Child Care |

346 |

50 |

134 |

529 |

|

Child and Adult Care Food Program |

— |

— |

525 |

525 |

|

CalWORKs Child Care Stage 2 |

387 |

— |

81 |

468 |

|

Support Programs |

27 |

— |

123 |

150 |

|

Migrant Child Care |

40 |

— |

6 |

46 |

|

Care for Children With Severe Disabilities |

2 |

— |

— |

2 |

|

Totals |

$1,379 |

$190 |

$1,479 |

$3,049 |

|

Note: Proposition 64 refers to revenue generated from taxes on cannabis. |

||||

|

DSS = Department of Social Services. |

||||

Shifts $31.7 Million From CDE to DSS for State Operations. The Governor’s budget also proposes shifting $31.7 million and 185.7 positions on an ongoing basis from CDE to DSS starting July 1, 2021. As Figure 3 shows, these positions are shifting from six different divisions within CDE, with the bulk of positions shifting from the Early Learning and Care Division and the Nutrition Services Division. Nearly all the positions and funds the Governor proposes shifting are funded with federal funds intended to support the administration of programs moving to DSS. Less than $1 million is funded from the General Fund.

Figure 3

Governor Proposes Shifting Positions

Across Six Divisions at CDE

|

CDE Division |

Positions Shifting |

New Positions |

|

Early Learning and Care |

72.5 |

17.0 |

|

Nutrition Services |

69.0 |

53.0 |

|

Fiscal and Administrative Services |

18.0 |

6.0 |

|

Audits and Investigations |

17.0 |

7.0 |

|

Technology Services |

6.7 |

— |

|

Legal |

1.5 |

— |

|

Indirect/Administrative |

1.0 |

— |

|

Totals |

185.7 |

83.0 |

|

CDE = California Department of Education and DSS = Department of Social Services. |

||

Provides $13 Million Ongoing General Fund for CDE State Operations to Address Administrative Shortfall. As part of the transition, the Governor’s budget includes $13 million and 83 new positions for CDE to backfill some of the positions shifting to DSS. As shown in Figure 3, the Governor proposes backfilling 53 nutrition positions—77 percent of the positions he proposes shifting to DSS. The administration indicates that these additional positions are intended to provide CDE with sufficient staff to administer the nutrition programs remaining at CDE, including the Food Distribution Program, Summer Meal Programs, and the School Nutrition Programs. The bulk of the remaining proposed positions are intended to support the State Preschool program.

Includes New Budget Structure and Provisional Language to Modify Shift Midyear. The Governor’s budget includes provisional language that would allow the administration to transfer local assistance expenditure authority (both federal fund and General Fund) between CDE and DSS during the course of the fiscal year. In addition, the proposed budget bill combines funding for all programs shifting to DSS into one schedule. Previously, funding for each child care program was listed separately in its own schedule, while the CACFP was combined with other child nutrition programs administered by CDE. The administration noted it intends to modify the language this spring and list each program and associated funding separately in the budget bill.

LAO Comments

Funds and Positions Shifting Not Based on Workload Analysis. The Governor’s proposed shift is almost entirely based on the fund source associated with these positions. For example, the Governor proposes moving all state operations positions funded with federal CCDBG funds that are set aside for state administration. This is consistent with the proposed shift of all local assistance CCDBG funding from CDE to DSS. Aligning local assistance and state operations funding within the same department makes sense. However, the administration has not conducted a workload analysis to determine whether the funding and positions at DSS are in line with its new administrative responsibilities. As a result, it is uncertain whether the level of proposed resources is fully justified. Given the magnitude of the proposed backfill for CDE, it does appear that DSS would likely have more funding and positions under the Governor’s proposal than required to address its new workload. Since there is no new workload across both departments, a cost neutral shift would be reasonable.

Cost of Shift Higher Than Anticipated, Full Cost Unclear. In his proposed 2020‑21 budget last January, the Governor proposed providing $10.4 million to create a new Department of Early Childhood Development and having child care programs administered under this department. As part of the May Revision for 2020‑21, the proposal was modified to instead shift child care programs to DSS. The administration indicated it was modifying the proposal due to cost concerns. The amount of funding requested in 2021‑22 ($13 million), however, now exceeds the cost of the initial proposal to create a separate department. Furthermore, the cost of the shift could grow in the future as the administration is still determining the resources it needs. The administration’s transition plan guide states DSS is “continuing to assess the resources and staffing needed” to administer the new programs.

Other Elements of Transition Also Lack Detail. In addition to lacking key information about costs, the administration also has not been able to answer several key questions regarding the administration of programs under DSS. For example, the plan is required to specify how the administration plans to maintain existing provider flexibility to transfer funds across General Child Care and State Preschool contracts. This flexibility allows providers that have both of these contracts to effectively meet the enrollment needs of their communities. While the administration indicates in its plan guide that it is “actively collaborating to develop processes to maintain these flexibilities,” it has not disclosed any details to help the Legislature evaluate whether these new processes would be more or less burdensome for providers compared to current processes.

Lack of Detail Potentially Due to Large Workload in the Current Year. Based on our conversations with both CDE and DSS, planning for the shift of programs within the time line specified in statute has been a large administrative workload on existing staff at both departments. For example, both departments have been involved in key workload to administer child care programs, such as developing the state’s Child Care and Development Fund Plan (a plan required by the federal government once every three years). In addition to the program shift, staff at both departments also have had higher‑than‑average workload as a result of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) pandemic. The state has implemented a number of pandemic related policies, such as providing temporary child care slots, stipends, and reimbursement flexibility. (We describe these policies in more detail in the next section of this post.) Staff time has been split between these priorities (the transition and pandemic response). Moreover, the significant workload has likely made it difficult for staff to dedicate sufficient time to preparing for the transition.

Given These Concerns, the Legislature May Want to Reconsider Continuing With Transition. Although the Legislature approved shifting programs from CDE to DSS as part of the 2020‑21 budget package, we think it may want to reconsider the shift given the various issues discussed above. The administrative costs associated with the shift are higher than anticipated and appear to result in administrative inefficiencies. Moreover, the administration has yet to provide key details of several important elements of the transition. While the main rationale for the shift was to better integrate and coordinate programs, the Governor has not provided concrete examples to explain how this outcome will in fact be achieved. We discuss the lack of specificity below.

- Child Care Programs. The administration has not yet provided any specific examples of how the programs will be better integrated and coordinated at DSS. Rather, the administration indicates it is in the process of engaging with stakeholders to identify options. The administration also stated that under DSS, its implementation of child care programs will “build upon prior efforts,” such as leveraging data‑driven decisions to determine allocation of child care funds. It is unclear how these efforts under DSS will result in greater benefits to children and families compared to CDE’s current efforts.

- CACFP. In addition to providing nutrition support to child care providers, CACFP supports adult day care, emergency shelters, and after school care. The administration plans to “connect the existing CACFP with other nutrition and child care programs currently housed at DSS.” However, it is unclear why these connections cannot be made within the current structure with CDE administering the program. CDE and DSS have collaborated on nutrition issues, the most recent example being the pandemic response to provide increased Cal Fresh benefits to families impacted by school closings. If the administration has specific concerns with how CDE is administering the program, more cost effective solutions likely exist to address these concerns.

Legislature Has Several Options on How to Proceed. In view of the concerns raised above, the Legislature has a range of options it could consider. Specifically, the Legislature could:

- Stop Transition. The Legislature could decide transitioning child care and CACFP to DSS is no longer a priority. This would “free up” $13 million in ongoing General Fund relative to the Governor’s budget proposal that would be available to support legislative priorities.

- Delay Transition. The Legislature could delay the transition. This would allow the administration to focus its entire attention on the pandemic response and plan for the transition on a slower time line. We think delaying the transition until a year after the COVID‑19 emergency declaration has ended would be a reasonable approach.

- Modify Scope of the Transition. The Legislature could reduce the number of programs shifting to DSS. If the Legislature takes this approach, we recommend keeping CACFP at CDE. The Legislature could further minimize the scope of the transition by also shifting certain child care programs to DSS, such as California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids Child Care Stages 2 and 3.

Key Issues for the Legislature to Consider if it Decides to Move Forward With the Transition. If the Legislature does decide to move forward with the transition, we identified two issues that it will want to consider:

- Revisiting State Preschool Oversight and Support. The requested backfill of positions for CDE are intended to maintain the existing level of administration for State Preschool. Historically, the level of administration was based on federal and state requirements, as State Preschool was funded in part with CCDBG funding. Since 2019‑20, however, State Preschool has been funded entirely from the state General Fund and no longer has to comply with federal CCDBG requirements. The state has an opportunity to revisit the state‑level oversight and support providers receive. For example, instead of having staff conduct activities formerly required by federal law, the Legislature may instead want to redirect these positions to provide more programmatic support to providers. If the state does decide to revisit the level of support and oversight, staff levels should align with these oversight and support expectations.

- Maintaining Legislative Oversight. In order for the Legislature to maintain its oversight role, we recommend modifying the proposed provisional language allowing the administration to shift expenditure authority between CDE and DSS. If the administration needs to make any budget revisions, we recommend it notify the Joint Legislative Budget Committee prior to making any adjustments. We further recommend amending the proposed budget bill so that funds are appropriated to child care in a similar structure as the 2020‑21 budget act. Specifically, we recommend that funding for each child care program be scheduled out in separate budget items instead of being consolidated together as proposed. This approach maximizes transparency and more effectively facilitates the ability of the Legislature to provide oversight of child care programs.

Supporting Child Care Programs During the Pandemic

In this section, we provide background on how the pandemic has affected child care providers and families. We then provide information on actions the state has taken to support child care providers and families. Last, we provide considerations for the Legislature to further support child care programs during the pandemic.

Background

Pandemic Has Affected Child Care Providers and Families. The COVID‑19 emergency, has placed increased fiscal pressure on child care providers. The Center for the Study of Child Care Employment conducted a survey of 953 California child care providers at the end of June 2020. The vast majority of child care providers reported they were serving fewer children compared to before the pandemic and 77 percent of open providers reported they experienced a loss of income from families. Providers are also reporting higher costs. Of open providers, 80 percent reported higher costs for cleaning, sanitation, and personal protective equipment. Families receiving child care also have been affected, particularly due to school and child care closures that have required families to find new child care arrangements.

State Has Taken Several Actions to Support Child Care Programs During the Pandemic. The vast majority of these actions were provided on a temporary basis and are only available during the current fiscal year. Most of these actions were funded with one‑time federal funds provided through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. In addition to the $350 million in CARES Act funding specifically for child care, the state also used $110 million from the Coronavirus Relief Fund (CRF) to support child care programs. The state had substantial discretion to allocate CRF for various programs related to the COVID‑19 emergency. Figure 4 describes the pandemic‑related actions in more detail.

Figure 4

Pandemic‑Related Child Care Actions

(In Millions)

|

Policy |

Description |

Total |

|

Alternative Payment Voucher Slots for Essential Workers |

Provided $50 million one time in 2019‑20 to provide temporary vouchers and $47 million ongoing federal funds in 2020‑21 to transition families to permanent vouchers. Provided an additional $138 million on a one‑time basis for 2020‑21. |

$235 |

|

Voucher Reimbursement Flexibility |

In 2020‑21, voucher‑provider payments are based on a child’s authorized hours of care instead of the amount of care used. This holds voucher providers harmless if a child temporarily does not attend child care. |

63 |

|

Family Fees |

From April 2020 through August 2020, the state temporarily waived family fees for those receiving subsidized care. From September 2020 through June 2021, the state has waived family fees for families not receiving in‑person care. |

62 |

|

Cleaning Supplies and Protective Equipment |

The state provided funds for gloves, face coverings, cleaning supplies, and labor costs associated with cleaning child care facilities. |

50 |

|

Voucher Paid Operation Days |

Provides an additional 14 paid non‑operation days. Funds used so child can attend another provider while the original provider is closed. |

40 |

|

School‑Aged Care |

Funds were to cover the additional cost of providing care to school‑aged children. During the school year, school‑aged children would typically receive care before and/or after school. As schools in most of the state remain closed, many school‑aged children participating in distance learning also are receiving care from a child care provider during the school day. |

38 |

|

Voucher Stipends |

Stipends to voucher providers based on the number of subsidized children enrolled. |

31 |

|

Direct Contract Reimbursement Flexibility |

Direct contract providers were provided reimbursement flexibility in 2020‑21. To receive this flexibility, providers must have opened to begin the school year or have been closed due to local or state public health guidance. Providers also must provide distance learning services to children enrolled in its programs and submit a distance learning plan to CDE. For providers that meet these conditions, reimbursement will be the lesser of their contract amount or program costs. Typically, provider reimbursement is also generally based on the attendance of eligible children. |

— |

|

Attendance Record Requirements |

Trailer legislation allows voucher providers to submit attendance records during 2020‑21 without a parent signature if the parent is unable to sign due to the COVID‑19 pandemic. Typically, providers are required to submit attendance records with a parent signature to receive reimbursement. |

— |

|

Total |

$518 |

|

|

CDE = California Department of Education and COVID‑19 = coronavirus disease 2019. |

||

Legislature Established Future Spending Priorities. The 2020‑21 budget package allows CDE to allocate additional federal funds if funds become available in the current year. Trailer legislation specifies the priority order and purposes the funds must be used for (see Figure 5). In the fall, the state made a budget revision fully funding the first priority with available CRF funds.

Figure 5

Additional Child Care and Preschool Spending if

Federal Funds Become Available

2020‑21 (In Millions), Listed in Priority Order

|

Waive fees for families not receiving in‑person care |

$30 |

|

Provide an additional 14 paid non‑operation days for voucher providers |

35 |

|

Add temporary voucher slots |

100 |

|

Provide additional temporary State Preschool and General Child Care slots |

30 |

|

Provide reopening grants to child care providers |

15 |

|

Provide stipends to child care providers |

90 |

|

Total |

$300 |

California Received an Additional $964 Million Federal Funding for Child Care. With the recent passage of H.R. 133 in December 2020, the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act, the state has received an additional $964 million in supplemental CCDBG funds. This additional funding can be used for most of the priorities outlined in the 2020‑21 budget package, as well as any other child care purposes related to the COVID‑19 emergency. Funds will be available for appropriation in the current and budget year.

Governor’s Budget Provides $55 Million One‑Time General Fund for COVID‑19 Related Support. The Governor’s budget includes $55 million one‑time General Fund to support child care providers and families during the pandemic. The Governor does not propose specific uses of these funds or indicate how they would be allocated.

Considerations for Supporting Child Care Programs

Below, we describe issues for the Legislature to consider when determining how to spend additional child care funds and modify program rules to most effectively support providers and families during the pandemic.

Consider Actions the State Can Implement Quickly. Given the immediate issues created by the COVID‑19 emergency, the Legislature will want to prioritize actions the state can implement quickly to get support to child care providers as soon as possible. Such actions could include the following:

- Use Existing Systems and Programs. While there is merit to considering new ideas for supporting child care providers and families, using existing systems and programs will deliver funding to providers more quickly and make implementation easier. Creating new programs and processes takes time, as the state would have to develop regulations and/or guidance, collect relevant data, and communicate program rules to providers. The state could use existing programs and systems to avoid these delays in implementation. For example, in spring 2020, the state used Resource and Referral agencies to distribute personal protective equipment to subsidized and nonsubsidized providers. The state could use these agencies in the future if it is interested in providing similar support.

- Extend Existing Pandemic Actions. Virtually all pandemic actions for child care providers were enacted by the state on a temporary basis, ending June 30, 2021. Extending these flexibilities would be administratively simple, as the guidance has already been written and implemented. Child care providers are already clear on how these actions impact their local programs.

- Use Simple Allocation Methodology. The state may want to allocate one‑time funds by using a simple formula instead of opting for a more sophisticated approach. Although complex formulas can more effectively target funding, allocating funds can be delayed as state agencies spend time developing models and collecting the appropriate data. For example, calculating stipends to providers based on a percent of their total contract would be simpler and quicker than temporarily increasing rates based on the regional market rate survey.

Consider Spreading Funds Across the Current and Budget Year. Given the one‑time nature of the General Fund and federal funds being provided, spreading funding over several fiscal years ensures the state can sustain the temporary support for a longer time period. For lump sum payments, such as stipends, spreading the funds over several years also gives providers more flexibility for spending the funds. However, the Legislature will want to ensure it fully expends federal funds during the allowable time period.

Consider Modifying Flexibilities to Ease Administrative Burden. Some of the policies implemented in the current year can be modified to ease the administrative burden for the state, local providers, and families. For example, family fees for September through July 2021 are waived for families not receiving in‑person services or sheltering in place. Since pandemic‑related child care closures and shelter‑in‑place requirements happen unexpectedly, this policy requires child care providers to revisit family fees throughout the month. Under typical circumstances, child care providers would only collect family fees at the beginning of the month. Waiving all family fees temporarily during the pandemic would be administratively simpler for all parties involved. We estimate this approach would have an annual cost in the high tens of millions of dollars.

Without Ongoing Funding, Temporary Slots Will Lead to Disenrollment Down the Line. During the pandemic, the Legislature has prioritized using one‑time funds to provide temporary slots for essential workers. The Legislature may want to consider providing similar funding with the additional CCDBG funding to continue to provide subsidized child care for families. Without ongoing funding, however, families receiving temporary slots will eventually be disenrolled. Providing additional one‑time funding for slots creates additional cost pressure to create ongoing slots that allow families to continue receiving child care. Although the temporary slots are intended to address temporary increases in the need for care, we would note that demand for subsidized child care from low‑income families has exceeded state funding for decades. As a result, we do not expect that demand for slots will decrease notably when the pandemic is over.

Applying Same Flexibilities to State Preschool Will Require General Fund Spending. During the pandemic, the state has so far provided the same flexibilities to State Preschool as it has for other child care programs. If the state wants to continue this practice in the budget year, it would likely need to fund the flexibilities with one‑time General Fund. This is because State Preschool programs do not meet all of the eligibility requirements to be funded with CCDBG.