LAO Contact

February 16, 2021

The 2021-22 Budget

California Community Colleges

- Introduction

- Overview of Governor’s Budget

- Fiscal Impact of the Pandemic

- Apportionments

- Student Support

- Online Tools

- Apprenticeships and Work‑Based Learning

- Instructional Materials

- Faculty Professional Development

Summary

In this report, we provide an overview of the Governor’s budget for the California Community Colleges (CCC), examine how the pandemic has affected CCC, then analyze the Governor’s major CCC proposals. Below, we share three main takeaways from the report.

Opportunities Exist to Be More Strategic With Ongoing Spending Commitments. The Governor’s budget includes eight new CCC ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund spending commitments (totaling $213 million). The largest ongoing proposal is to provide apportionments a 1.5 percent cost‑of‑living adjustment. We believe the Legislature has opportunities to improve the Governor’s overall community college budget package by taking fewer, but more strategic, actions. Regarding ongoing spending, we encourage the Legislature to consider increasing the augmentation for apportionments by redirecting funds from lower‑priority proposals. (We identify some candidates for redirection in this report.) Potentially offering a larger increase to apportionments would help colleges in responding to staffing, salary, and benefit pressures while also giving them flexibility in responding to key local needs.

Legislature Could Be More Strategic With One‑Time Funds Too. The Governor’s budget includes nine one‑time Proposition 98 General Fund proposals (totaling $1.6 billion). The Governor’s largest one‑time proposal is to pay down just over $1.1 billion of the existing nearly $1.5 billion in deferrals. As with the ongoing proposals, we think the Legislature might want to consider redirecting funds from certain unjustified or otherwise lower‑priority one‑time initiatives (several of which we identify in this report) to a more select set of strategic one‑time priorities. In particular, the Legislature could consider redirecting resources to paying down more deferrals and/or mitigating districts’ future pension cost increases.

Governor’s Student Support Proposals Could Be Better Coordinated. Among the Governor’s proposals are three relating to student support totaling $380 million ($30 million ongoing and $350 million one time). These proposals provide additional funding for students’ basic needs (including food and housing), mental health, access to technology, and emergency grants. Although the Governor has a laudable focus on issues exacerbated by the pandemic, he continues the state’s uncoordinated and piecemeal approach to addressing those issues—combining unlike services into one categorical program, not specifying how proposed programs would interact with existing ones, and providing one‑time funding for a purpose (food pantry and housing assistance programs) that requires ongoing funds to be sustainable. We recommend the Legislature consider a different approach that would pool all or a portion of the proposed new funds (and an existing CCC housing program) into a basic needs block grant. Under such an approach, districts would have flexibility to use the funds for any combination of food, housing, mental health, and technology services, based on the needs of their students.

Introduction

This report analyzes the Governor’s major budget proposals for the California Community Colleges (CCC). We begin by describing the Governor’s overall budget plan for CCC. We then review what is known to date about the impacts of the pandemic on community colleges’ budgets. Next, we analyze the Governor’s specific CCC proposals, with sections focused on (1) apportionments, (2) student support, (3) online tools, (4) apprenticeships and work‑based learning, (5) instructional materials, and (6) faculty professional development. We provide tables with more detail about CCC’s budget on our EdBudget website.

Overview of Governor’s Budget

Total CCC Funding Reaches $17 Billion Under Governor’s Budget. Just over $10 billion of the CCC budget comes from Proposition 98 funds. Proposition 98 support for CCC in 2021‑22 increases by $423 million (4.4 percent) over the revised 2020‑21 level. In addition to Proposition 98 General Fund, the state provides CCC with non‑Proposition 98 General Fund for certain purposes. (Most notably, non‑Proposition 98 funds cover debt service on state general obligation bonds for CCC facilities, a portion of CCC faculty retirement costs, and operations at the Chancellor’s Office.) Much of CCC’s remaining funding comes from student enrollment fees, other student fees (such as nonresident tuition, parking fees, and health services fees), and various local sources (such as revenue from facility rentals and community service programs). As Figure 1 details, community colleges also are receiving federal relief funds over the period shown.

Figure 1

California Community Colleges Rely Heavily on Proposition 98 Funding

(Dollars in Millions, Except Funding Per Student)

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

Change From 2020‑21 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Proposition 98 |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$6,062 |

$6,174 |

$6,413a |

$239 |

3.9% |

|

Local property tax |

3,252 |

3,414 |

3,598 |

184 |

5.4 |

|

Subtotals |

($9,313) |

($9,588) |

($10,011) |

($423) |

(4.4%) |

|

Other State |

|||||

|

Other General Fund |

$658 |

$654 |

$663 |

$9 |

1.4% |

|

Lottery |

246 |

233 |

233 |

—b |

‑0.2 |

|

Special funds |

18 |

41 |

96 |

55 |

133.3 |

|

Subtotals |

($922) |

($929) |

($992) |

($63) |

(6.8%) |

|

Other Local |

|||||

|

Enrollment fees |

$455 |

$445 |

$447 |

$1 |

0.3% |

|

Other local revenuec |

5,011 |

4,168 |

4,098 |

‑71 |

‑1.7 |

|

Subtotals |

($5,466) |

($4,614) |

($4,544) |

(‑$69) |

(‑1.5%) |

|

Federal |

|||||

|

Federal relief fundsd |

$614 |

$54 |

$1,280 |

$1,226 |

2,272.0% |

|

Other federal funds |

287 |

287 |

287 |

— |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($900) |

($341) |

($1,567) |

($1,226) |

(359.9%) |

|

Totals |

$16,602 |

$15,471 |

$17,114 |

$1,643 |

10.6% |

|

Full‑time equivalent (FTE) students |

1,109,723 |

1,100,046 |

1,107,695 |

7,649 |

0.7%e |

|

Proposition 98 funding per FTE student |

$8,393 |

$8,716 |

$9,038 |

$321 |

3.7% |

|

Total funding per FTE student |

$14,961 |

$14,064 |

$15,450 |

$1,386 |

9.9% |

|

aExcludes $327 million in proposed apportionment deferrals to 2022‑23. bDifference of less than $500,000. cPrimarily consists of revenue from student fees (other than enrollment fees), sales and services, and grants and contracts, as well as local debt‑service payments. dFor 2019‑20, consists of $580 million in CARES Act funds for formula allocations (at least half of which is for emergency student aid), $33 million for community colleges designated as minority‑serving institutions, and $425,000 for districts designated as institutions with the greatest unmet need. Funds for 2020‑21 are designated by the state for a COVID‑19 response block grant. Funds for 2021‑22 are estimates as of January 2021 per CRRSAA. Of the estimated nearly $1.3 billion total, at least $290 million must be designated for emergency student aid. eReflects the net of the Governor’s proposed 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth together with all other enrollment adjustments. CARES = Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security; COVID‑19 = coronavirus disease 2019; and CRRSAA = Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act. |

|||||

Governor Proposes to Keep Deferrals in Place for 2020‑21, but Then Pay Down Most of Them in 2021‑22. The Governor proposes just over $1.1 billion one‑time Proposition 98 General Fund to pay down deferrals in the budget year. For 2021‑22, $326 million in deferrals would remain in place. Specifically, a portion of CCC’s May and June 2022 apportionment payments would be deferred to early 2022‑23. Growth in the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee in 2021‑22 is sufficient to cover the ongoing program costs that were not covered in 2020‑21 due to the deferrals.

Governor Has Numerous Other CCC Proposals. Figure 2 lists the CCC deferral paydown as well as the Governor’s 16 other CCC Proposition 98 proposals. Eight of these proposals reflect new ongoing spending commitments (totaling $213 million) and eight are one‑time initiatives (totaling $428 million). The largest ongoing proposal is to provide apportionments a 1.5 percent cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA). The Governor’s budget links this base increase to two expectations regarding student equity gaps and online education. The Governor also proposes funding enrollment growth of 0.5 percent (about 5,500 additional full‑time equivalent [FTE] students). The Governor’s largest one‑time proposals (after the deferral paydown) relate to emergency student financial aid and student basic needs.

Figure 2

Governor Has Many Proposition 98

CCC Spending Proposals

(In Millions)

|

Proposal |

Amount |

|

New Ongoing Spending |

|

|

COLA for apportionments (1.5 percent) |

$111 |

|

Student mental health and technology |

30 |

|

Enrollment growth (0.5 percent) |

23 |

|

California Apprenticeship Initiative |

15 |

|

COLA for select categorical programs (1.5 percent)a |

14 |

|

Online education and support block grant |

11 |

|

CENIC broadband |

8 |

|

Adult Education Program technical assistance |

1 |

|

Subtotal |

($213) |

|

One‑Time Initiatives |

|

|

Deferral paydown |

$1,127b |

|

Student emergency financial aid grants |

250c |

|

Student basic needs |

100 |

|

Faculty professional development |

20 |

|

Student retention and enrollment strategies |

20c |

|

Work‑based learning |

20 |

|

Zero‑textbook‑cost degrees |

15 |

|

Instructional materials for dual enrollment students |

3 |

|

AB 1460 implementationd/anti‑racism initiatives |

1 |

|

Subtotal |

($1,555) |

|

Total |

$1,768 |

|

aApplies to the Adult Education Program, apprenticeship programs, CalWORKs student services, campus child care support, Disabled Students Programs and Services, Extended Opportunity Programs and Services, and mandates block grant. bOf this amount, $145 million is scored to 2019‑20, $901 million is scored to 2020‑21, and $81 million is scored to 2021‑22. cScored to 2020‑21. dImplements activities relating to Chapter 32 of 2020 (AB 1460, Weber). COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment; CENIC = Corporation for Education Network Initiatives in California; and AB = Assembly Bill. |

|

Governor Includes Two of These Proposals in “Early Action” Package. As part of a broader early action package, the Governor proposes $100 million for emergency student financial aid grants and $20 million for student retention and enrollment strategies. The Governor intends for the Legislature to consider his early action package in the spring.

Four of These Proposals Are Largely Reenactments From Last Year. One of the ongoing proposals (for the California Apprenticeship Initiative) and three of the one‑time proposals (relating to work‑based learning, zero‑textbook‑cost degrees, and dual enrollment programs) are the same or very similar to proposals introduced by the Governor last January but withdrawn at the May Revision.

Governor Proposes No Change to Enrollment Fee. State law currently sets the CCC enrollment fee at $46 per unit (or $1,380 for a full‑time student taking 30 semester units per year). The Governor proposes no increase in the fee, which has remained flat since summer 2012.

Previous Pension Package Implemented, but No New Pension Relief. The 2019‑20 budget plan included $3.2 billion non‑Proposition 98 General Fund for certain pension payments the state was scheduled to make on behalf of schools and community colleges. Of this amount, $2.3 billion was intended to reduce future pension costs. The 2020‑21 budget package repurposed this $2.3 billion to provide immediate budget benefit in 2020‑21 and 2021‑22. Specifically, community colleges received an additional $147 million in 2020‑21 and are scheduled to receive an additional $113 million in 2021‑22 to cover a portion of their pension costs, with their employer contribution rates reduced by approximately 2 percentage points. The Governor’s budget implements the already scheduled payment for 2021‑22 but does not propose any new pension relief payments to districts.

LAO Comments

Opportunities Exist to Be More Strategic With Ongoing Spending Commitments. We believe the Legislature has opportunities to improve the Governor’s overall community college budget package by taking fewer, but more strategic, actions. Regarding ongoing spending, we encourage the Legislature to consider increasing the augmentation for apportionments by redirecting funds from lower‑priority proposals. Potentially offering a larger increase to apportionments would help colleges in responding to staffing, salary, and benefit pressures while also giving them flexibility in responding to key local needs. Throughout the remainder of this report, we identify a few ongoing spending proposals that we believe are good candidates for such a redirection.

Also Opportunities to Be More Strategic With One‑Time Initiatives. Spending on one‑time activities has the benefit of creating a budget cushion, which helps protect ongoing programs from volatility in the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. Having a cushion seems especially important in 2021‑22 given the continued and significant economic uncertainty due to the pandemic. As with the ongoing proposals, we think the Legislature might want to consider redirecting funds from some one‑time initiatives to a more select set of strategic one‑time priorities. Specifically, the Legislature could consider redirecting resources from lower‑priority, one‑time proposals to (1) paying down more deferrals and/or (2) mitigating districts’ future pension cost increases. Paying down more of the deferrals has several advantages, including reducing districts’ need for borrowing, reestablishing the link between ongoing program costs and ongoing funding, and giving the Legislature more budget tools to respond to future economic downturns. Paying down future pension costs, meanwhile, could help smooth out a notable increase in district costs currently projected for 2022‑23. Throughout this report, we also identify several one‑time initiatives that we believe are good candidates for this type of redirection.

Fiscal Impact of the Pandemic

Community Colleges Have Operated Remotely Since Start of Pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, 17 percent of overall instruction was provided online at the community colleges. The percent varied by college, ranging from 100 percent at Calbright College (a new statewide online college), to 78 percent at Coastline College, to less than 10 percent at several colleges (including City College of San Francisco and Los Angeles Trade‑Technical College). In response to the public health crisis, all community colleges shifted primarily to remote operations beginning in March 2020—the middle of the spring term for most colleges. Colleges continue to offer the vast majority of their instruction online, with the exception of a small number of courses that involve laboratory or other required hands‑on work. In addition, campuses are providing most of their student services (such as academic advising, financial aid administration, and mental health services) online. Colleges tend to be operating their noncore programs (such as their bookstores and parking programs) at substantially reduced capacity.

Pandemic Has Had Notable Fiscal Implications for Colleges and Students. The colleges’ shift to primarily remote instruction resulted in some extraordinary costs. These costs include acquiring technology such as laptops for employees and students, providing training and support for faculty moving their classes online, and purchasing personal protective equipment for staff remaining on campus. The Chancellor’s Office estimates that these extraordinary costs total about $350 million through 2020‑21. Colleges also provided a total of an estimated $58 million in enrollment and other fee refunds to students whose classes were abruptly cancelled in spring 2020 (such as those in performing arts and certain other classes that faculty deemed as too difficult to convert to an online format) or who were otherwise unable or unwilling to stay enrolled. In addition, colleges have experienced revenue losses from parking, food services, facility rentals, and various other noncore programs. As with the colleges, many students are facing extraordinary challenges, including reduced household income, higher technology costs, and disruptions in housing arrangements.

Federal Government Has Provided Substantial Fiscal Relief Both to Colleges and Students. One source of assistance for the colleges and their students has been federal relief funding. The federal government provided higher education institutions with relief funding shortly after the onset of the pandemic (in spring 2020) and is providing a second round of relief funding in winter 2021. (See our posts, Overview of Federal Higher Education Relief and Second Round of Federal Higher Education Relief Funding, for more detail.) As Figure 3 shows, federal relief funding across the two rounds totals nearly $2 billion for community colleges. Each round requires colleges to designate at least $290 million in federal relief funds for emergency student financial aid. The remaining $1.4 billion in federal relief funds are available for college operations. College relief funds can be used for an array of expenses, including health and safety measures, technology, professional development, and backfilling revenue declines from parking and other noncore programs. Based on our discussions with various districts, these federal funds appear to be sufficient to cover the colleges’ costs and revenue losses related to the pandemic through 2020‑21.

Figure 3

Community Colleges Are Receiving Federal Relief Funds

(In Millions)

|

Spring 2020 Relief Package |

|

|

CARES Act: Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund |

|

|

Base grants: student aid |

$290 |

|

Base grants: institutional relief |

290 |

|

Supplemental grants: minority‑serving institutions |

33 |

|

Supplemental grants: institutions with unmet need |

—a |

|

Subtotal |

($613) |

|

Coronavirus Relief Fund |

$54 |

|

Total |

$667 |

|

Winter 2021 Relief Package |

|

|

CRRSAA: Higher Education Emergency Relief Fundb |

|

|

Base grants: student aid |

$290 |

|

Base grants: institutional relief |

1,023 |

|

Total |

$1,313 |

|

Grand Total |

$1,981 |

|

aCertain colleges received supplemental grants totaling $425,000. bShows CRRSAA allocations known to date. Note: In most cases, campuses have one year from receiving funds to spend them. CARES = Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security and CRRSAA = Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act. |

|

Apportionments

In this section, we provide background on community college apportionment funding, describe the Governor’s proposals to increase apportionments for inflation and enrollment growth, assess those proposals, and offer associated recommendations.

Background

State Adopted New Apportionment Funding Formula in 2018‑19. For many years, the state has allocated general purpose funding to community colleges using an apportionment formula. Prior to 2018‑19, the state based apportionment funding for credit instruction almost entirely on enrollment. In 2018‑19, the state changed the credit‑based apportionment formula to include three main components—a base allocation linked to enrollment, a supplemental allocation linked to low‑income student counts, and a student success allocation linked to specified student outcomes. Of total apportionment funding, the base allocation accounts for 70 percent, the supplemental allocation accounts for 20 percent, and the student success allocation accounts for 10 percent. For each of the three components, the state set per‑student funding rates. The rates increase in years in which the state provides a COLA. The new formula—formally known as the Student Centered Funding Formula—does not apply to incarcerated students or high school students in credit programs. It also does not apply to students in noncredit programs. Apportionments for these students remain based entirely on enrollment.

Due to Disruptions Resulting From Pandemic, Certain Aspects of Formula Have Been Temporarily Modified. Statute specifies the years of data that are to be used to calculate the amount a district generates under the Student Centered Funding Formula. State regulations, however, provide the Chancellor’s Office with authority to use alternative years of data in extraordinary cases. Known as the “emergency conditions allowance,” the Chancellor’s Office has been allowing colleges to use alternative years of data for 2019‑20 and 2020‑21. (The 2020‑21 budget also explicitly provided colleges with this flexibility.) The purpose of the emergency conditions allowance is to prevent districts from having their apportionment funding reduced due to enrollment drops and other disruptions resulting from the pandemic.

Formula Insulates Districts From Certain Funding Losses for Next Several Years. In addition to the regulatory emergency conditions allowance just described, statute includes “hold harmless” provisions for community college districts that would have received more funding under the apportionment formula that existed prior to 2018‑19 than the new formula. Through 2023‑24, these community college districts are to receive the total apportionment amount they received in 2017‑18 adjusted for COLA each year of the period. Beginning in 2024‑25, districts are to receive no less than the per‑student rate they generated in 2017‑18 under the former apportionment formula multiplied by their current FTE student count. In 2020‑21, 32 districts were held harmless under these provisions, and the state provided $170 million in total hold harmless funding (that is, funding above what these districts would have generated based upon the Student Centered Funding Formula).

State Allocates Enrollment Growth Separately. Enrollment growth funding is provided on top of the funding derived from all the other components of the apportionment formula. Statute does not specify how the state is to go about determining how much growth funding to provide. Historically, the state considers several factors, including changes in the adult population, the unemployment rate, prior‑year enrollment, and the condition of the General Fund.

Enrollment Trends

Heading Into the Pandemic, CCC Enrollment Had Plateaued. During the Great Recession, community college student demand increased, but enrollment ended up dropping as the state reduced funding for the colleges. As state funding recovered during the early years of the economic expansion (2012‑13 through 2015‑16), systemwide enrollment increased. Enrollment flattened thereafter, as the period of economic expansion continued and unemployment remained at or near record lows.

CCC Enrollment Increased in Summer 2020. Historically, enrollment demand at the community colleges increases during a recession, as individuals affected by the economic downturn seek retraining. Summer 2020 appeared to follow this trend, as enrollment ended up higher than the summer 2019 level by about 4,000 FTE students (3.3 percent). Enrollment was uneven throughout the state, though, with 40 districts reporting an increase and 31 districts reporting a decline. (As of this writing, one district has not yet reported summer 2020 enrollment.) Based on discussions with the RP Group (a statewide organization of CCC researchers) and district administrators, the systemwide increase could be due in part to students re‑enrolling in the summer to complete courses they had withdrawn from in the spring. It also could be due in part to students seeking transfer—or already enrolled at a university—deciding to take online courses to earn college credits over the summer. Summer enrollment increased considerably in transfer‑level courses such as psychology, chemistry, and calculus (but declined in other programs such as physical education, culinary arts, and cosmetology/barbering).

CCC Enrollment Dropped Notably in Fall 2020. As of this writing, the Chancellor’s Office had not yet received complete fall 2020 enrollment data from districts. Based on surveys by the RP Group and preliminary Chancellor’s Office data, FTE students declined by an estimated 11 percent systemwide from fall 2019 to fall 2020 (an 8 percent decline in terms of headcount). Nearly all districts that have submitted data to the Chancellor’s Office as of the end of January 2021 report an enrollment drop. While enrollment declines are affecting most student demographic groups, districts generally report the largest enrollment declines among African American, Hispanic, male, and older adult students. Based on our discussions with various districts, spring 2021 enrollment is down similarly to fall 2020.

Several Factors Likely Contributing to Enrollment Drops. Based on our discussions with colleges and national surveys, reduced enrollment demand in 2020‑21 likely is due to a number of factors. Some students believe they do not do well learning in an online format. Others, particularly in rural areas, indicate they lack reliable, high‑speed internet connectivity to take online classes. Taking online courses also could be difficult due to a lack of a quiet study space at home. Beyond these challenges, community college students who are parents or otherwise responsible for taking care of children could have less ability to study themselves given K‑12 school closures. Students also might consider working (if they still have a job) even more important if other family members have lost jobs, or they could be spending time looking for a new job if they recently lost one. In either of these cases, enrolling in college coursework might have become a lower priority for them.

Proposals

Proposes COLA Tied to Districts Meeting Two Conditions. The Governor’s budget includes $111 million to cover a 1.5 percent COLA for apportionments. (The 2020‑21 budget did not provide a COLA.) This proposed COLA is less than half of the 3.84 percent COLA proposed for school districts’ Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), which the Governor’s budget states would make up for the lack of an LCFF COLA in the current year. As a condition of receiving the apportionment COLA, community college districts would be required to: (1) submit a plan by June 30, 2022 that identifies strategies for reducing equity gaps by 40 percent by 2023 and fully closing them by 2027 and (2) adopt policies by June 30, 2022 designed to maintain the share of campuses’ online courses and programs at a level that is at least 10 percentage points higher than their share in 2018‑19. (The Governor links proposed base increases for the universities to meeting similar conditions, as well as to a requirement that they create a dual admission pathway with the community colleges.)

Funds Enrollment Growth. The budget includes $23 million for 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth (equating to about 5,500 additional FTE students). Each district, in turn, would be eligible to grow up to 0.5 percent. Provisional language for the budget year allows the Chancellor’s Office to allocate any ultimately unused growth funding to backfill any shortfalls in the apportionment funding, such as ones resulting from lower‑than‑estimated enrollment fee or local property tax revenue. The Chancellor’s Office could make any such redirection after underlying data had been finalized, which would occur after the close of the fiscal year. (This is the same provisional language that has been used in recent years.)

Proposes One‑Time Funding to Boost Outreach to Students. The Governor’s budget also includes $20 million one time for student outreach as part of his early action package. The purpose of these funds is for colleges to reach out to former students who recently dropped out and engage with current or prospective students who might be hesitant to enroll at the colleges due to the pandemic. At the time of this writing, the administration had not yet submitted provisional language including the details of the proposal. The administration indicates its intention is to be flexible, allowing the Chancellor’s Office to decide grant recipients, amounts, and timing. The Chancellor’s Office could distribute the funds among community college districts or retain them centrally for a statewide outreach effort.

Assessment

Districts Have Various Compensation‑Related Costs. On average, districts spend about 85 percent of their operating budget on salary and benefit (compensation) costs. While the exact split varies from district to district, salaries and wages can account for up to about 70 percent of total compensation costs, with pensions typically accounting for another 10 percent to 15 percent of total compensation costs. District health care costs for active employees can vary, but it is common to account for roughly 10 percent of compensation costs. Retiree health care costs can vary too, but often account for less than 5 percent of costs. In addition to these costs, districts must pay various other compensation‑related costs for employees, such as workers’ compensation and unemployment insurance, which together typically account for about 5 percent of total costs.

Districts Are Facing Pensions and Other Cost Pressures in 2021‑22. Augmenting apportionment funding can help community colleges cover employee salary increases, higher pension costs, and higher health care premiums, among other cost increases. Community college pension costs, for example, are increasing by a total of about $70 million for 2021‑22, with the amount increasing by another about $160 million in 2022‑23. Health care premiums are expected to increase by about 5 percent at a number of districts in 2021‑22, with some districts reporting increases of 8 percent or 9 percent. Some districts cover the full increase in health care premiums. In other cases, districts cap the amount they cover and require employees to cover all or part of any increase. Like school districts, community college districts also face cost pressures to provide a COLA to salaries given increased living costs for their employees.

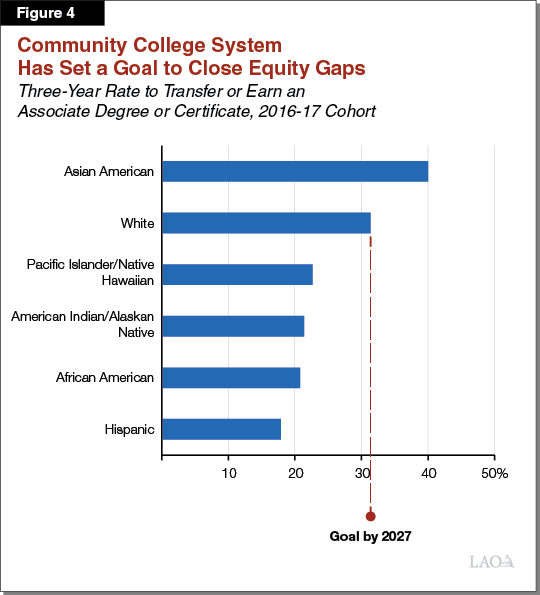

Requiring Districts to Develop Equity Plans Would Be Redundant. This is because districts already must develop and update every three years student equity plans. The state requires these plans as a condition of districts receiving Student Equity and Achievement Program funds. In these plans, districts are required to identify equity gaps by student race/ethnicity, age, and various other demographics. They also must identify strategies to close those gaps. These district plans already are aligned with the goals cited in the Governor’s provisional language (that is, a 40 percent reduction in equity gaps by 2023, with equity‑gap elimination by 2027), which originated in the CCC system’s 2017 Vision for Success strategic plan. Figure 4 shows the 2027 goals of the Vision for Success by racial/ethnic groups.

Proposed Online Education Requirement Is Arbitrary and Lacks Justification. Online education can offer a number of potential benefits, including making coursework more accessible to students who otherwise might not be able to enroll due to restrictive personal or professional obligations and allowing campuses to increase instruction and enrollment without a commensurate need for additional physical infrastructure. Online instruction is not suited for every student or educational program, though, and research suggests that online courses tend to have lower completion rates than in‑person instruction, with greater gaps for African American and Hispanic students. Given student demand for online courses and campus facility issues, we are concerned that the administration has not justified whether the proposed 10 percentage point increase is warranted. In addition, all colleges, regardless of their baseline, would be expected to increase their online offerings by the same percentage point. A more refined analysis might indicate a higher or lower level of online education is desirable at any particular campus. Without a clearer rationale for setting online enrollment targets, colleges could make poor decisions that work counter to promoting student success. For example, arbitrary increases in online courses potentially could work counter to the Governor’s proposed expectation to eliminate equity gaps.

Enrollment Demand in 2021‑22 Could Depend on a Number of Factors. Because they are open‑access institutions, community college enrollment demand is often difficult to predict. This year is even more difficult given the disruptions caused by the pandemic. As of this writing, it is unclear whether fall 2021 instruction will be primarily virtual, primarily in‑person, or a hybrid model. Community colleges generally are taking a “wait and see” approach and plan to make a decision by spring depending on the trajectory of the pandemic and updates on the effectiveness of vaccines and vaccine deployment. On the one hand, if colleges—and K‑12 schools—reopen in the fall and the economy is slow to recover for displaced workers, CCC enrollment demand could be strong. If colleges remain primarily online in the fall and children must continue to attend school virtually, CCC enrollment demand could remain weak.

Merit of Governor’s Retention and Enrollment Proposal Also Depends on Fall 2021 Decisions. As discussed above, the drop in enrollment demand this year likely is due to a number of factors, including individuals being reluctant to take online classes and their need to be home while their children are attending online school. Were community colleges and schools able to reopen campuses in the fall for instruction, community colleges could use the Governor’s proposed $20 million one time to boost outreach and advertising in the community. Colleges could hire limited‑term workers, for example, to contact former students and inform them of the programs that will be offered on campus. (The potential effect of these types of efforts on enrollment levels is uncertain.) Were community colleges and schools to remain primarily virtual in the fall, however, it is unclear how the proposed funds would be useful given the underlying reasons for weak enrollment demand would be unchanged.

Recommendations

Make COLA Decision Once Better Information Is Available This Spring. As with school funding, the COLA for CCC apportionments is based on the price index for state and local governments. The COLA rate will be locked down in late April when the state receives updated data from the federal Bureau of Economic Analysis. By early May, the Legislature also will have better information on state revenues, which, in turn, will affect the amount available for new CCC Proposition 98 spending. If additional Proposition 98 ongoing funds are available in May, the Legislature may wish to provide an even greater increase than the Governor proposes to community college apportionments. A larger increase would help all community college districts address rising pension and health care costs while also addressing pressure to increase employee salaries. The Legislature also could consider repurposing lower‑priority ongoing proposals to support a larger COLA. (We identify some lower‑priority proposals later in this analysis.)

Reject Governor’s Two Conditions Tied to a COLA, but Require Report About Online Education. Given that the state already requires districts to maintain and update a plan aimed at eliminating student equity gaps, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to require another equity plan. Given the arbitrariness of the proposed 10 percentage point increase in online courses, we also recommend rejecting this proposal. However, we understand the administration’s desire to maintain the current momentum toward developing and improving online courses. To this end, we recommend the Legislature instead adopt budget bill language directing the Chancellor’s Office to report on campuses’ experiences with online education. Such a report should include: (1) analysis as to which courses are most suitable for online instruction, (2) an estimate of the fiscal impact of expanding online education, (3) a plan for improving student access and outcomes using technology, and (4) an assessment of the need for additional faculty professional development. To ensure this information is available to assist next year’s budget deliberations, we recommend requiring the Chancellor’s Office to submit this information by November 2021. Such a report would give the Legislature a better basis to determine how to support online education at the community college in the coming years.

Withhold Decisions on Enrollment Growth and Retention‑Enrollment Proposals. Though the Legislature currently lacks key information to help it make an informed decision on enrollment growth and the Governor’s retention and enrollment proposal, more clarity likely will come over the next several months. By the time of the May Revision, the Chancellor’s Office will have provided the Legislature with final 2019‑20 enrollment data and initial 2020‑21 enrollment data. By that time, more school and CCC districts also likely will have announced their fall instructional plans. This information, in turn, will help the Legislature assess whether the Governor’s proposed 0.5 percent enrollment growth expectation for the CCC system in 2021‑22 is reasonable. Similarly, this information will help the Legislature better assess whether one‑time funds for community college outreach and advertising might be advantageous.

Student Support

In this section, we focus on student support programs. The Governor has three proposals in this area, together totaling $380 million Proposition 98 General Fund ($30 million ongoing and $350 million one time). The proposals would fund food, housing, mental health, and technology initiatives, as well as emergency grants. After providing background on student support programs, we describe each of the proposals in this area, then assess those proposals, and make associated recommendations.

Background

Many Students Report Difficulty Covering Basic Needs. The term “students’ basic needs” generally refers to living costs that affect students’ well‑being. Definitions vary, but they almost always include food and housing and may also include other components, such as access to medical care, mental health services, and technology. Previous surveys suggest a notable share of CCC students have difficulty covering certain basic needs. In particular, in surveys of CCC students conducted before the pandemic, 41 percent reported they skipped meals or cut the size of their meals for financial reasons and 12 percent reported not eating for at least one whole day the prior month because of lack of money. Rates of food and housing insecurity are highest among African Americans; American Indians; Pacific Islanders; and students who identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, or nonbinary. (Because the survey had a 5 percent response rate, respondents may not be representative of the overall CCC student population.)

Traditional Financial Aid Programs Provide Support for Basic Needs. The primary way the federal government and the state support living costs for CCC students is through financial aid. Many CCC students with financial need qualify for a federal Pell Grant (worth up to $6,345 in 2020‑21). In addition, the state funds the Cal Grant access award (worth up to $1,648 annually) and Student Success Completion Grant (worth up to $4,000 annually for Cal Grant recipients attending CCC full time). Federally subsidized and unsubsidized loan programs also are available to assist students. These grants and loans can be used for any cost of attendance, including housing, food, transportation, books, and supplies.

Targeted Programs Also Support Basic Needs. In addition to traditional financial aid programs, many colleges operate programs targeted toward students’ basic needs. These programs include on‑campus food pantries, emergency housing, and health services (including mental health services), among others. These targeted programs are funded through a mix of sources, including state funds, donations, and, in the case of health services, student fees. As Figure 5 shows, the state has funded several basic needs initiatives in recent years. With one exception (the rapid rehousing program), these programs were supported with one‑time funds through 2019‑20. The 2020‑21 budget package then added a requirement that districts operate on‑campus food pantries or food distributions as a condition of receiving ongoing Student Equity and Achievement Program (SEAP) funds. (This program funds academic counseling and various other strategies aimed at improving student completion rates and closing equity gaps.) The 2020‑21 budget did not provide an augmentation to SEAP to operate these food services. (The Governor’s 2020‑21 budget proposed $11.4 million in ongoing funds to support campus food services, but the proposal was rescinded in the May Revision due to a projected state budget shortfall.)

Figure 5

State Has Funded Several CCC Basic Needs Initiatives

One‑Time Proposition 98 General Fund, Unless Otherwise Noted (In Millions)

|

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|

|

Food pantries |

$2.5 |

$10.0 |

$3.9 |

—a |

|

Rapid rehousing |

— |

— |

9.0b |

$9.0b |

|

Mental health services |

4.5 |

10.0 |

7.0c |

— |

|

Totals |

$7.0 |

$20.0 |

$20.0 |

$9.0 |

|

aThe 2020‑21 budget package requires districts to operate a food pantry or food distribution program as a condition of receiving Student Equity and Achievement Program funds. bReflects ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund support. cReflects one‑time Proposition 63 funds (Mental Health Services Fund). |

||||

During Pandemic, Many Students Report Having More Challenges With Basic Needs. The state does not have comprehensive data on the impact of the pandemic on student financial need, largely because financial aid applications use income data from two years prior to the award year. However, surveys suggest many students have had unanticipated financial needs due to the pandemic. In a California Student Aid Commission survey of financial aid applicants across all segments conducted in late spring 2020, over 70 percent of respondents reported experiencing a loss of income due to the pandemic. Students also reported increased concern about paying for various living costs, including housing and food, health care, and technology. (This survey had a response rate of 12 percent.) Also in late spring 2020, a Student Senate for CCC survey found that 67 percent of respondents reported they were experiencing a higher level of anxiety, stress, or other mental distress than usual. (This survey was completed by a total of 1,690 students from 64 colleges.)

Relief Funds Have Provided Emergency Grants and Other Assistance to Students. Community colleges received a first round of federal relief funds in spring 2020 and are expecting to receive a second round of funds shortly. Colleges must spend a portion of these funds for student aid. Systemwide across the two rounds, the minimum portion that must be used for student aid totals $580 million. Under the new federal legislation (relating to second‑round funding), grants may support students’ regular costs of attendance or emergency expenses related to the pandemic. The new legislation includes a requirement for institutions to prioritize aid for students with exceptional need, such as Pell Grant recipients. In addition to the federal relief funds, the state provided CCC with $11 million non‑Proposition 98 General Fund in the 2020‑21 Budget Act for emergency grants to undocumented students. The colleges also have used federal relief funds to provide laptops and other technology to students so they can access online courses.

Proposals

Proposes Ongoing Funds for Mental Health and Technology. The Governor proposes to provide community colleges with $30 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund for student mental health services and access to technology (electronic devices and internet connectivity). The provisional language does not specify what portion of funds is to be used in each of the two areas, with the colleges having discretion to determine the split. Provisional language includes a requirement for the Chancellor’s Office to report by January 1, 2025 and every three years thereafter on how much each district received and how they used the funds.

Proposes One‑Time Funds for Basic Needs. The Governor proposes $100 million one‑time Proposition 98 General Fund for addressing student food and housing insecurity. Funds could be used for various activities, including to support food pantries, enroll students in CalFresh (food benefits for low‑income individuals), and help homeless students obtain housing. Funds would be available for encumbrance through June 30, 2024. Provisional language includes a requirement for the Chancellor’s Office to report by January 1, 2025 on how much funding it provided to each district, how the funds were used, the impact the funds had on reducing food and housing insecurity among students, and certain other information.

Proposes One‑Time Funds for Emergency Grants. The Governor proposes to provide a total of $250 million one‑time Proposition 98 General Fund for these grants. Of this amount, $100 million is proposed as part of the Governor’s early action package. Trailer bill language specifies that the Chancellor’s Office would allocate the funds to colleges based on their headcount of Pell Grant recipients, as well as undocumented students qualifying for resident tuition who meet certain income criteria. Colleges may award grants to students who self‑certify that they meet the following criteria:

- Have an emergency financial need.

- Meet the financial eligibility requirements to receive a CCC fee waiver.

- Meet certain enrollment or employment conditions.

Assessment

Proposals Address a Longstanding Problem Exacerbated by the Pandemic. Despite the lack of comprehensive data measuring students’ unmet basic needs, the available survey data suggests that unmet needs are substantial. Moreover, these needs have likely increased for some students during the pandemic. The Governor’s proposals address this sizable and timely problem.

To Date, State Has Taken a Piecemeal Approach to Addressing Students’ Basic Needs. Over the past four years, the state has funded multiple basic needs initiatives at the colleges. However, the state’s overarching strategy for addressing students’ root problems remains unclear. The state lacks a definition of what basic needs include, a way of measuring demand for programs supporting them, an expectation about levels of service, and clearly articulated goals about desired student outcomes. In the absence of this basic framework, funding levels for basic needs initiatives have tended to wax and wane each year, without a strong guiding policy rationale. Moreover, the state’s approach to allocating funds among the higher education segments is inconsistent and has not directly tied funding to need. For example, the University of California receives ongoing state funding for its basic needs initiative, while CCC, which serves a greater proportion of low‑income students, has primarily received one‑time funds.

Governor’s Proposals Would Add to This Uncoordinated Approach. The Governor proposes to create a new mental health and technology program on top of the existing basic needs programs. That new program combines two distinct objectives—increasing student mental health resources and increasing digital equity—without a clear nexus between the two. Moreover, it is unclear how the new funds are intended to interact with the campus mental health programs currently supported by student fees or the proposed funding for online tools that will support telehealth services for students. Similarly, it is unclear how the proposed funds for basic needs are intended to interact with CCC’s existing rapid rehousing program. As with existing basic needs programs, the Governor’s proposals also do not set any expectations for levels of service and desired student outcomes. Absent clearly stated objectives, holding colleges accountable for their use of the funds would be difficult.

To Be Sustainable, Basic Needs Programs Require Some Ongoing Funding. Basic needs programs have some ongoing operational costs. Food pantries, for example, need staff to obtain food supplies from community partners, manage inventory, and assist students who visit the pantries. Because such operations entail ongoing costs, colleges have difficulty maintaining consistent levels of service using one‑time allocations. Due to estimates at the time about a decline in the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee, the state made the difficult decision last year not to provide dedicated, ongoing funding for campus food services. The state knew that by requiring colleges to operate food service programs out of existing SEAP funds, the new requirement likely would result in a reduction in existing SEAP‑funded activities (such as counseling, tutoring, and other targeted academic support for traditionally underrepresented student groups). Now that revised estimates suggest additional funding is available for CCC, the Legislature has an opportunity to revisit its 2020‑21 budget action. This could include providing colleges a minimum level of ongoing support for sustaining their basic needs services. In addition, the Legislature could consider providing some one‑time funding to address variable costs (such as purchasing additional food during an economic downturn, when more students than usual may be in need).

Opportunity Exists to Coordinate Proposed State Emergency Grants and Federal Relief Grants. The administration did not have the benefit of knowing about the new federal relief package when developing its budget proposals, as the federal legislation was not enacted until late December 2020. Now that substantial new federal funds have been authorized for student aid, the Legislature can consider what one‑time state funding, if any, it would like to add in this area. Unfortunately, as with many other groups impacted by the pandemic, there is no comprehensive data measuring the increase in students’ financial need under the pandemic, or the amount of unmet need remaining after accounting for traditional and emergency financial aid programs. As a result, the Legislature has no easy way to determine if additional state funds are warranted.

Opportunities Remain to Leverage Public Assistance Programs. Over the past several years, the state has worked to increase student enrollment in CalFresh. Nonetheless, a recent report from the California Department of Social Services estimates that between 290,000 and 560,000 students eligible for CalFresh across California’s public segments were not enrolled as of 2018‑19. (No estimate is available specifically for community college students.) The state has an opportunity to further increase CalFresh enrollment in 2020‑21 and 2021‑22 as a result of the new federal relief legislation. That legislation expands student CalFresh eligibility during the public health emergency by removing the standard work requirement for certain students who are very low income or eligible for work‑study. Moreover, the state has opportunities to translate the lessons learned from its CalFresh student enrollment efforts to various other public assistance programs (such as Medi‑Cal, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and unemployment insurance) that students may be underutilizing.

Recommendations

Consider Creating a Basic Needs Block Grant. The Governor’s focus on students’ basic needs is laudable, but his proposals in this area lack coordination and accountability. A more coherent approach the Legislature might consider would be to pool all or a portion of the proposed new funds and the existing rapid rehousing program into a basic needs block grant. Under such an approach, districts would have flexibility to use the funds for any combination of food, housing, mental health, and technology services, based on the needs of their students. A major component of such a block grant would be an accountability system that (1) identifies the state’s expected levels of service and student outcomes and (2) includes regular reporting that tracks and measures districts’ performance in meeting these objectives. For example, annual reports provided by districts could identify student enrollment in CalFresh, the number of days students report being homeless, and average wait times to see a mental health professional, among other information.

Evaluate Emergency Grants Proposal in Light of New Federal Relief. We recommend the Legislature direct the Chancellor’s Office to report this spring on colleges’ plans for the upcoming federal relief funds. These spring plans should (1) identify the amount of federal relief funds that colleges intend to use for student aid, (2) estimate the number of students likely to receive federal emergency grants, (3) describe the methods colleges are using to distribute funds among students, (4) estimate the amount of aid a student is likely to receive, and (5) identify students’ remaining financial needs. After obtaining this information, the Legislature would be in a better position to make a decision on the proposed state emergency aid funds. For example, the Legislature could design state aid to supplement federal aid, such as by providing summer‑term assistance to students who would receive federal aid in the spring. Alternatively, the Legislature could decide that federally funded emergency grants are sufficient in size and instead repurpose the proposed state funds for other one‑time priorities (such as paying down additional deferrals or providing more pension relief to districts). If the Legislature provides additional funds for emergency student aid in 2021‑22, we recommend requiring colleges to report on how they distribute and use the additional funding, as this could help guide future state budget decisions. The state required similar reports for the emergency aid it provided to undocumented students in 2020‑21.

Expand Efforts to Increase Student Utilization of Public Assistance Programs. In addition to increasing the number of students enrolled in CalFresh, there are likely opportunities to expand student enrollment in other public assistance programs, which could help students cover other costs, including housing, mental health, and technology costs. The Legislature could direct community colleges to partner with the relevant state and local agencies to explore strategies to increase utilization of other public assistance among college students.

Online Tools

In this section, we provide background on CCC’s Online Education Initiative, discuss the Governor’s proposal to augment funding for colleges’ online tools, assess the proposal, and provide an associated recommendation.

Background

Initiative Aims to Provide Systemwide Access to Online Courses. The Online Education Initiative (OEI) consists of several projects, including a common course management system for colleges, resources to help faculty design high‑quality online courses, and the California Virtual Campus Exchange. The exchange creates a more streamlined process for students at participating colleges to take online classes from other participating colleges. The state currently provides $20 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund for OEI. The Chancellor’s Office has a grant with the Foothill‑De Anza Community College District to administer OEI.

Common Course Management System Is a Key Component of Initiative. Faculty use a course management system to post course information (such as the syllabus), instructional content (such as readings and videos), assignments, and other material. Students use the system to submit assignments, collaborate with classmates, and communicate with instructors. Historically, each college or district had selected its own course management system from among several vendors. In 2015, a large committee overseen by the Chancellor’s Office selected the Canvas course management system to be the common system across colleges. Currently, all but one community college use Canvas. (Calbright College, a fully online college, uses a separate system.)

A Suite of Online Tools Can Be Integrated Into Canvas. This suite includes a platform that permits students and their academic counselors to meet virtually, a platform that enables students to participate in virtual science labs, a tool that gauges the accessibility of instructors’ online course content, and telehealth services (which allow students to access third‑party health care professionals for medical or mental health issues). Colleges can choose which of these online tools they would like to integrate into their local Canvas configurations.

OEI Has Three Types of Price Assistance for Colleges. Using its state appropriation, OEI fully subsidizes Canvas subscription costs on behalf of colleges. OEI also fully subsidizes technical (help desk) support for Canvas users and subscription costs for certain online tools. For other online tools, OEI provides a partial subsidy for colleges (also using its state appropriation). The third type of price assistance involves negotiating a “bulk” discounted rate for certain online tools that colleges use their own funds to purchase. To help it negotiate discounted rates, the Chancellor’s Office typically partners with other agencies, including the Foundation for California Community Colleges.

Mass Migration to Online Instruction Led to Cost Pressures on OEI. Beginning in March 2020, OEI costs escalated primarily for two reasons. First, the Chancellor’s Office decided to support colleges’ transition to online courses by fully subsidizing certain online tools (such as the accessibility tool) that previously were the financial responsibility of colleges. In addition, colleges’ largescale migration to online instruction resulted in higher usage rates of Canvas, the Canvas help desk (which OEI upgraded from limited technical support to 24/7 assistance for users), and various online tools integrated with Canvas. Higher usage rates, in turn, resulted in higher subscription and maintenance costs.

Chancellor’s Office Has Announced Some Costs Will Have to Shift to Colleges Absent Additional State Funding. The Chancellor’s Office has responded to these higher OEI costs by redirecting unspent funds from certain other areas of CCC’s budget, including funds previously set aside for in‑person trainings. In addition, OEI has been scaling back some of its subsidies. For example, OEI began limiting the number of tutoring hours it will subsidize for an online tutoring service. As of January 2021, colleges that wish to exceed their initial allotment of hours must cover the costs using district funds. Recently, the Chancellor’s Office notified colleges of plans to reduce the state subsidy for other online tools beginning in July 2021 absent additional state funding for 2021‑22.

Proposal

Proposes $10.6 Million Ongoing Augmentation for Online Tools. The augmentation would bring total funding for OEI to $30.6 million Proposition 98 General Fund. (Although the proposal relates to OEI, the Governor’s budget places the $10.6 million in a separate categorical program that supports various other systemwide technology projects, including electronic transcripts.) The Governor’s budget does not specify the specific online tools that are to be supported with the additional funds, but provisional language states that the funds “may include, but are not limited to, access to online tutoring and counseling, ensuring available technical support, and providing mental health services and other student support services.” The language is silent on who would administer the additional funding.

Assessment

Unclear How Long Online Usage Rates Will Remain at Elevated Levels. Given increasing vaccine deployments, colleges might be able to offer more in‑person instruction during the 2021‑22 academic year. Were this to happen, pressure on OEI would be reduced at least somewhat, if not significantly.

Colleges Have Federal Relief Funds to Help With Extraordinary Pandemic‑Related Costs. As discussed earlier in our report, colleges are receiving approximately $1.4 billion in federal campus relief funds—considerably more than the reported adverse fiscal impacts of the pandemic on colleges to date. Based on our discussions with districts, this federal relief funding remains available to cover extraordinary costs associated with the pandemic, such as higher subscription and usage costs from online tools. Colleges have until next year (2022) to use these funds.

Recommendation

Reject Proposal, Reevaluate Need for Additional Funding Next Year. Given that the out‑year costs to support OEI are unknown and federal relief funding remains available, providing an ongoing augmentation for the program at this time is premature. (Colleges may have even more federal relief funds should Congress approve the Biden Administration’s recovery proposal now under consideration.) We thus recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal. Instead of providing an augmentation in 2021‑22, we recommend directing the Chancellor’s Office to report in spring 2022 on the status of campus reopenings and what the implication is for the usage rates and costs of Canvas and the suite of associated online tools. With that information, the Legislature could make a better determination of whether to provide additional funding for OEI for 2022‑23.

Apprenticeships and Work‑Based Learning

In this section, we provide background on (1) traditional apprenticeships, (2) a state‑funded apprenticeship program focusing on nontraditional sectors, and (3) CCC initiatives that incorporate work‑based leaning. We then describe the Governor’s proposals in each of these areas, assess those proposals, and offer associated recommendations.

Background

Some Individuals Are Trained Through Traditional Apprenticeships. The state has about 93,000 apprentices, mostly in the construction trades and public safety (including firefighting) sectors. Apprenticeships in these sectors are commonly referred to as “traditional apprenticeships.” Apprenticeship programs consist of two key components: (1) on‑the‑job training completed under the supervision of skilled workers and (2) classroom learning, known as related and supplemental instruction (RSI). Traditional apprenticeships typically are sponsored by employers and labor unions. These sponsors are largely responsible for providing on‑the‑job training. It is also common for sponsors to directly provide RSI, taught by their employees at stand‑alone training centers.

State Reimburses Apprenticeship Sponsors for Instruction. Sponsors typically cover the majority of the costs of instructing and training apprentices, often maintaining a training trust fund to support those costs. However, the state has a longstanding CCC categorical program that reimburses sponsors for a portion of their instructional costs. Sponsors are reimbursed at the hourly rate set for certain CCC noncredit instruction (currently $6.44). Sponsors must partner with a school or community college district to qualify for these funds. To receive reimbursement, the sponsor submits a record of RSI hours to the partnering district, which, in turn, submits those hours to the Chancellor’s Office. The Chancellor’s Office provides RSI funds to the district, which takes a small portion of the funds off the top and then passes the remaining funds to the sponsor.

State Seeks to Spur Apprenticeship Programs in Nontraditional Sectors. In 2015‑16, the state created the California Apprenticeship Initiative (CAI) to support new apprenticeship programs in high‑growth industry sectors—such as health care, information technology, and clean energy—that have not traditionally used the apprenticeship model. The state has provided $15 million annually—a total of $90 million to date—for CAI. Community college districts and K‑12 agencies (including school districts and county offices of education) may apply for these grants. To be eligible for funding, applicants must demonstrate a commitment from one or more employers to hire participating apprentices. Applicants also must submit a description of their program and a budget, among other criteria. Grant funding is intended to cover program start‑up costs such as curriculum development. As CAI funds are only available for a limited term, grantees are expected to find other fund sources to cover ongoing program costs once the grant expires.

Work‑Based Learning Covers a Broad Range of Career Readiness Activities. Defined broadly, work‑based learning refers to activities that promote career exploration and preparation. Schools and colleges choose what specific work‑based learning opportunities to provide their students. Common opportunities include guest job shadowing, internships, and apprenticeships. Promoting work‑based learning is a key purpose of the Strong Workforce Program. The state provides CCC with $248 million annually for this program. Work‑based learning also is an important component of CCC’s Guided Pathways Program, which aims to develop structured, efficient academic course sequences for entering students. State law defines guided pathways to include “group projects, internships, and other applied learning experiences to enhance instruction and student success.” In 2017‑18, the state provided CCC with $150 million one time for this initiative. The majority of Guided Pathways Program funds are being allocated to colleges in stages across five years, through 2021‑22.

Proposals

Proposes COLA for Traditional Apprenticeship Programs. The Governor’s budget provides $1 million for a 1.5 percent COLA on the RSI rate. This would increase the hourly reimbursement rate from $6.44 to $6.54. The Governor’s budget would not change the number of RSI hours that are funded (a total of about 10 million hours in 2020‑21).

Proposes to Double Ongoing Funding for CAI. Under the Governor’s proposal, CAI would receive a $15 million ongoing augmentation in 2020‑21, bringing total ongoing funding to $30 million. The Governor proposes no other changes to CAI.

Proposes $20 Million One Time for New Work‑Based Learning Initiative. Under the Governor’s proposal, this funding would support competitive grants to colleges to “expand work‑based learning models and programs at community colleges, with the goal of ensuring that students complete programs with applied work experience.” Provisional language charges the Chancellor’s Office with developing a competitive grant process for allocating the funds. At this time, the Chancellor’s Office is considering providing $1 million each to 20 colleges, with a focus on funding additional apprenticeships, internships, clinical practicums, and applied learning experiences within the classroom. The funds would be available through June 30, 2026.

Assessment

No Concerns With COLA for Traditional Apprenticeships. We do not have concerns with the proposed COLA for traditional apprenticeships. The augmentation would allow apprenticeship sponsors and partnering districts to address program cost pressures, including staff salaries and benefits.

Lack of Justification for Expanding CAI Funding at This Time. There appears to be insufficient demand among colleges, K‑12 agencies, and employers to fully utilize even the current level of funding for CAI. Based on data the Chancellor’s Office shared with our office, it appears grant awards fell short of available funds in both 2018‑19 and 2019‑20. Though the data provided by the Chancellor’s Office for this program is very limited, it suggests that only $12.5 million of the $14 million set aside for grants in 2018‑19 was awarded due to a lack of eligible applications. It appears no grants were awarded in 2019‑20. In addition to lack of unmet demand, key questions remain about the financial sustainability of CAI‑funded apprenticeships. While CAI is intended to create lasting programs that will serve apprentices for many years to come, the state does not yet have data on how many past CAI grantees have continued their programs beyond the grant period. The Foundation for California Community Colleges has partnered with Social Policy Research Associates on a follow‑up study on this topic. (The study was originally expected to be completed by summer 2020, but the Foundation indicates its release was delayed due to disruptions caused by the pandemic.) The study’s release date is anticipated for March or April 2021.

With Several Programs Already Focused on Work‑Based Learning, Another Is Not Warranted. Work‑based learning is explicitly part of the Strong Workforce Program and Guided Pathways Program. As discussed earlier, the state also supports apprenticeships—one form of work‑based learning—through both a categorical program that reimburses sponsors for instructional hours and a competitive grant program that provides seed funding for new apprenticeships.

One‑Time Funds Are Not a Good Fit for Supporting the Proposed Work‑Based Learning Activities. Based on conversations with the Chancellor’s Office, the proposed grants likely would support a range of expenses, including work‑based learning coordinators, stipends for industry practitioners to provide work‑based learning opportunities, curriculum development, and student screening and preparation. Most of these activities are ongoing in nature, requiring continued funding to sustain them. Without a plan to cover the costs moving forward, these activities are at risk of ramping up, only to end when the grant period ends. Such an approach also has the drawback of creating cost pressure for the state to sustain the activities in future years, despite a projected operating deficit.

Recommendations

Approve COLA for Traditional Apprenticeships. We recommend the Legislature approve the 1.5 percent COLA to the RSI rate for traditional apprenticeships, as the augmentation could help sponsors in operating their programs.

Reject CAI Augmentation. We believe it would be premature to expand CAI for two reasons. First, demand among eligible applicants appears insufficient for CCC to fully utilize even the existing funding level. Second, the Legislature currently lacks data on whether the new apprenticeship programs created to date are being sustained after grant funding ends. Later this year, the follow‑up study described above or other evaluation activities supported by the Chancellor’s Office could provide critical information about the programs funded to date. Having better information on initial CAI outcomes could inform future budget decisions for the program. If the findings were to show that most apprenticeship programs ended due to insufficient funding once their CAI grant expired, the Legislature might consider policy changes next year, including potentially refining the grant requirements. Alternatively, if the findings were to show that many grant recipients have identified ongoing fund sources, then the Legislature might consider expanding the program. Were this to be the case, we encourage the Legislature to ensure that any augmentation be based on evidence of unmet demand for CAI grants.

Reject Governor’s Proposal for Work‑Based Learning. Given the state already funds several programs focused on work‑based learning and most of the proposed activities associated with this new initiative are not of a one‑time nature, we recommend the Legislature reject the proposal and redirect the associated one‑time funds to other Proposition 98 priorities. For example, the Legislature could consider providing more one‑time funding to pay down additional deferrals and smooth out future district pension cost increases.

Instructional Materials

In this section, we first analyze the Governor’s proposal to create more degrees that would rely solely on instructional materials that are free of charge to students (commonly known as “zero‑textbook‑cost degrees”). We then analyze the Governor’s proposal to fund instructional materials for certain high school students taking community colleges classes (dual enrollment students).

Zero‑Textbook‑Cost Degrees

Below, we provide background on zero‑textbook‑cost degrees, then describe the Governor’s proposal, offer our assessment, and make an associated recommendation.

Background

Open Educational Resources (OER) Are Intended to Reduce the Cost of Instructional Materials. OER are digital instructional materials that educators can develop, share, repurpose, and make available to their students. OER can be used for in‑person classes as well as hybrid and fully online courses. OER come in many forms—ranging from course readings, videos, and tests, to textbooks. The use of OER content in place of instructional materials sold by publishers has several benefits, including reducing students’ costs and increasing access to materials. Numerous groups, including state higher education systems, consortia of higher education institutions, and national nonprofit organizations provide online OER repositories and search tools. Special state grant initiatives have supported faculty in developing OER.

A Few Years Ago, the State Funded a Zero‑Textbook‑Cost Degree Initiative. Beginning in 2012, the state funded several intersegmental initiatives intended to build up a shared repository of OER course materials. In an effort to take the next step and go beyond OER for individual courses, the state provided $5 million one time in 2016‑17 to create entire degrees relying solely on OER. Specifically, the $5 million was for a competitive grant program aimed at helping community colleges develop zero‑textbook‑cost associate degrees and career technical education certificates. Budget trailer legislation required grantees to prioritize the development of such degrees and certificates using existing OER materials before creating new content. The Chancellor’s Office was permitted to provide colleges with grants of up to $200,000 for each degree or certificate developed. Grantees were to “strive to implement degrees” by fall 2018.

First Zero‑Textbook‑Cost Degree Initiative Had a Reporting Requirement. The trailer bill language authorizing this initiative required the Chancellor’s Office to submit a report to the Legislature and Department of Finance by June 30, 2019 that included (1) the number of degrees developed by each grantee, (2) the number of students who completed a zero‑textbook‑cost degree or certificate program, (3) the estimated annual savings to students, and (4) recommendations to improve or expand zero‑textbook‑cost degrees. As of this writing, the Chancellor’s Office had not yet submitted this report.

Academic Senate Is Rolling Out More OER to Support More Zero‑Textbook‑Cost Degrees. The 2018‑19 budget provided $6 million one time for the CCC Academic Senate to lead an additional OER effort. Thus far, the Academic Senate has funded two new rounds of OER development, with additional rounds planned over the next three years. The Academic Senate’s focus for every round of funding is to prioritize OER that is needed to complete a new zero‑textbook‑cost degree for students, with an emphasis on associate degrees for transfer. During the first grant round, colleges created new OER content for courses in 18 disciplines. For the second round, new OER is in the process of being finalized for 18 additional disciplines. After faculty review of the newly created OER, the Academic Senate provides corresponding professional development to faculty throughout the state on integrating the OER into their teaching.

Proposal

Proposes $15 Million One Time for CCC to Create More Zero‑Textbook‑Cost Degrees. The administration’s trailer bill language for this proposal is similar to language the state adopted for the 2016‑17 initiative. The Chancellor’s Office may award grants of up to $200,000 for each associate degree or certificate developed. The intent is for grantees to begin offering the new round of zero‑textbook‑cost degrees by the 2023‑24 academic year. The Chancellor’s Office must report to the Legislature and Department of Finance by June 30, 2024 on the results of the initiative and make recommendations for further expansion or improvement.

Assessment