LAO Contact

February 19, 2021

The 2021-22 Budget

Educator Workforce Proposals

In this post, we analyze the Governor’s proposals to address teacher shortages, as well as his proposals to provide additional professional development for school staff.

Teacher Shortages

Below, we provide background on teacher shortages, describe the Governor’s proposals related to these issues, assess these proposals, and offer associated recommendations.

Background

California Has About 300,000 School Teachers. In 2018‑19, about 295,000 full‑time equivalent teachers were employed in California’s public school system. This is an increase of 9.8 percent over the 2010‑11 level (the low point during the Great Recession). Coupled with the effects of declining student enrollment, the statewide student‑to‑teacher ratio, in turn, has dropped every year since its peak in 2010‑11 (23:1). In 2018‑19, this ratio was about 21:1—comparable to the level prior to the Great Recession.

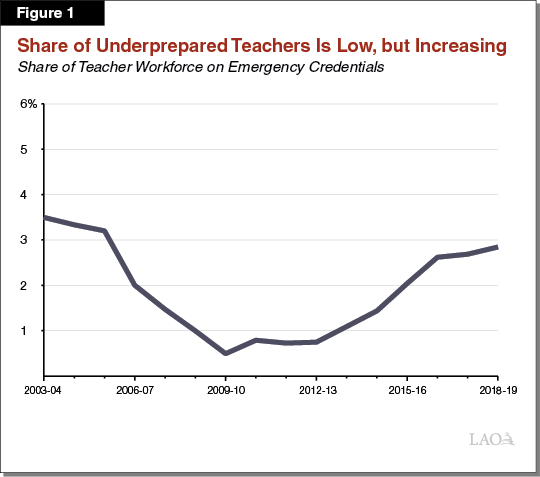

Some Districts Unable to Find Credentialed Teachers. Despite recent growth in the teacher workforce, some school districts in the state are unable to find credentialed teachers. As Figure 1 shows, almost 3 percent of the teacher workforce (about 8,700 teachers) had an emergency credential in 2018‑19. The share of teachers on emergency credentials has risen every year since 2009‑10, when the demand for teachers was low. Certain subject areas and types of schools are more likely to rely on underprepared teachers:

- Special Education, Science, and Math Are More Likely to Reflect Shortages. In reports required by the U.S. Department of Education, California has identified shortages of special education, science, and math teachers nearly every year since 1990‑91. Special education teachers tend to have higher rates of turnover due to several factors, such as the increased risk of lawsuits and considerable reporting requirements to comply with federal special education law. Teacher shortages in science and math are attributed to a shortage of undergraduates in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) majors and the high salaries that these graduates can receive in other professions.

- Low‑Income Urban Schools and Rural Schools Rely More Heavily on Underprepared Teachers. Staffing difficulties appear most pronounced in low‑income urban schools, as well as rural schools. National research shows that between 1987 to 2016, about one‑quarter of public schools accounted for almost half of all public school teacher turnover. Schools most affected by high teacher turnover were those with higher shares of low‑income students and/or students of color, as well as those in urban or rural areas. In California, higher teacher turnover also is reported in these types of schools.

Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic Could Worsen Teacher Shortages. A national survey of teachers from November 2020 found that 27 percent of teachers were considering taking a leave of absence, leaving the teaching profession, or retiring early in response to the pandemic. Data in California is consistent with this finding. According to the California State Teachers’ Retirement System, which manages the state’s pension system for teachers, 3,202 California teachers retired in the second half of 2020—a 26 percent increase relative to 2019. Although the pandemic appears to have accelerated teachers leaving the workforce, data on teachers entering the workforce—such as district hiring of new teachers and enrollment in teacher preparation programs in 2020‑21—are not yet available. Anecdotal evidence, however, suggests that enrollment in teacher preparation programs is higher for 2020‑21 relative to the prior year, which could mitigate other pandemic‑related impacts in subsequent years.

In Recent Years, State Has Funded Various Programs to Address Teacher Shortages. Figure 2 describes the programs that have received one‑time state funding since 2016‑17 to address teacher shortages. Some programs are aimed at increasing the supply of teachers. For instance, the Classified School Employee Teacher Credentialing Program (Classified Program) provides financial support for classified staff to pursue their teaching credential. Other programs focused on improving or accelerating teacher preparation, particularly in high‑need subject areas. The Teacher Residency Grant Program funds the expansion of residency programs in special education, bilingual education, and STEM fields that provide teacher candidates more support and classroom experience by first teaching alongside a mentor teacher. Other programs, such as the Golden State Teacher Grant Program, target the recruitment of special education teachers in schools with higher shares of underprepared teachers.

Figure 2

State Has Provided $190 Million Since 2016‑17 to Address Teacher Shortages

General Fund Unless Otherwise Indicated (In Millions)

|

Program |

Year |

Description |

Funding Allocation |

Amount |

|

Teacher Residency Grant Program |

2018‑19 |

Supports establishing and expanding teacher residency programs in special education, STEM, and bilingual education. |

CTC competitively awards grants to districts, COEs, and school‑university partnerships. There are two grant types: (1) planning grants of up to $50,000 and (2) residency grants of up to $20,000 per resident in the new or expanded program. |

$51a |

|

Local Solution Grants |

2018‑19 |

Provided funding to local efforts to recruit and retain special education teachers. |

CTC competitively awarded grants of up to $20,000 per participant to districts, COEs, and schools. Grantees required to provide a dollar‑for‑dollar match. |

50 |

|

Classified School Employee Teacher Credentialing Program |

2016‑17 and 2017‑18 |

Provides financial assistance to classified school employees, such as instructional aides, to pursue teaching credentials. |

CTC competitively awarded grants of $4,000 per participant per year for up to five years to districts, COEs, and schools. |

45 |

|

Golden State Teacher Grant Program |

2020‑21 |

Provides financial assistance to students enrolled in teacher preparation programs who commit to working in special education at a school with a high share of teachers on emergency credentials. |

CSAC awards funds to participating teachers. This program was federally funded. |

15b |

|

Integrated Undergraduate Teacher Preparation Grants |

2016‑17 |

Supported expanding integrated programs that allow participants to earn a bachelor’s degree and a teaching credential within four years. Programs focused on special education, STEM, and bilingual education received funding priority. |

CTC competitively awarded planning grants of up to $250,000 to universities. |

10 |

|

California Educator Development Program |

2017‑18 |

Assisted districts with recruiting and preparing teachers, principals, and other schools leaders. |

California Center on Teaching Careers competitively awarded grants to 26 districts, COEs, and schools. This program was federally funded. |

9 |

|

California Center on Teaching Careers |

2016‑17 |

Established a statewide teacher recruitment center to recruit qualified and capable individuals into the teaching field, particularly to low‑income schools in special education, STEM, and bilingual education. |

CTC competitively awarded grant to Tulare COE to operate center. |

5 |

|

Bilingual Teacher Professional Development Program |

2017‑18 |

Supported teachers pursuing authorization to teach bilingual and multilingual classes. |

CDE competitively awarded grants to eight districts and COEs. |

5 |

|

Total |

$190 |

|||

|

aProgram initially received $75 million. The 2020‑21 Budget Act swept $23 million in unused funds. bProgram initially received $90 million in 2019‑20 budget, but funds were swept as part of 2020‑21 budget. |

||||

|

STEM = science, technology, engineering, and math; CTC = Commission on Teacher Credentialing; COE = county office of education; CSAC = California Student Aid Commission; and CDE = California Department of Education. |

||||

Substantial Federal Emergency Relief Has Been Provided to Schools Within the Past Year. In response to the pandemic, the federal government passed two emergency relief packages providing significant one‑time funding for K‑12 public education. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, signed into law on March 27, 2020, allocated $1.5 billion to California public schools based on numbers of low‑income and disadvantaged children. These federal funds are available until September 30, 2022 and could be used on a variety of activities including maintaining continuity of school services (such as teacher recruitment and retention). Signed into law on December 27, 2020, the second federal relief package allocated an additional $6 billion to California public schools under the same allocation formula and broad range of allowable uses as the CARES funding. Schools must spend these funds by September 30, 2023.

Governor’s Proposals

Provides $225 Million One Time for Previously Funded Teacher Programs. The Governor’s budget provides additional funding for three previously funded programs:

- Teacher Residency Grant Program ($100 Million Proposition 98). Funding is for another round of awards to establish new and expand existing teacher residencies. The proposal also includes several changes to the program rules. Most notably, the proposal allows the Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) to expand the subject areas eligible for grant funding to include other shortage areas identified by CTC. Unlike previous funding, the Governor’s proposal does not allocate a specific amount of funding for each shortage area. (The initial funding for the program provided $50 million for special education and $25 million for both STEM and bilingual education.)

- Golden State Teacher Grant Program ($100 Million Non‑Proposition 98 General Fund). The California Student Aid Commission would award grants of up to $20,000 to each teacher candidate agreeing to teach in a priority school for four years. A teacher candidate must be enrolled in a teacher preparation program to receive a grant and agree to repay the grant if they fail to complete the service commitment. In contrast to the funding provided in 2020‑21, the Governor’s proposal includes two main program changes. First, rather than limiting the program to special education candidates, grants would be available for candidates pursuing credentials to teach bilingual education, STEM, special education, multiple subject instruction, and other shortage areas identified by CTC. Second, the Governor proposes to change the definition of a priority school to one in which 55 percent or more of its student population is either low income or an English learner. (Under current law, priority schools are defined based on having a high share of teachers on emergency credentials.) After accounting for funding that can be used for administration and outreach, the proposed funding would support up to 4,925 grants.

- Classified Program ($25 Million Proposition 98). Funding would support at least an additional 1,041 participants with grants of up to $24,000 over five years. School districts, county offices of education (COEs), and charter schools that have not previously received funding would receive priority for funding.

Assessment

First Round of Funding for Teacher Residency Grant Was Not Fully Exhausted. Of the $50 million provided in 2018‑19 specifically for special education residency programs, CTC was only able to award $27 million in the first funding round. The CTC subsequently released a second request for proposals to award the remaining funds, but these funds were swept in the 2020‑21 budget package due to the state’s fiscal condition. The $25 million set aside for STEM and bilingual education, however, has been exhausted.

Residency Programs May Improve Preparation but Are Challenging to Initiate and Sustain. Research suggests that teachers prepared through residency programs tend to feel more prepared than other beginning teachers and typically remain teaching in the same district for a longer period of time. Despite these potential benefits, however, residency programs can be difficult to develop and financially sustain. For example, the districts we spoke to mentioned they had challenges establishing a reliable partnership with the university, attracting residents due to the appeal of other preparation pathways (such as internship programs) that allow teacher candidates to earn a teaching salary while completing their program, and sustaining funding for the program after the residency grant ends.

Classified Program Is in High Demand. The Classified Program is oversubscribed. The initial two rounds of funding provided enough financial assistance to support 2,260 classified employees. However, an additional 6,000 classified employees requested to participate, and applications from 27 school districts and COEs remain unfunded. Administrators we spoke to viewed the program as a long‑term recruitment and “grow‑your‑own” retention strategy. Administrators also noted that, compared to the current teacher workforce, the participants in the Classified Program are more likely to be from the local community and share the same racial and ethnic backgrounds as the students they serve.

Classified Program Not Targeted to Statewide Shortage Areas. Although applicants were required to demonstrate a need for credentialed teachers in their applications, those with greater need did not receive priority in the application process. As a result, several districts participating in the program have relatively low shares of underprepared teachers. Of the 23 districts that applied individually (not part of a larger consortium), 14 had a lower percentage of teachers on emergency credentials than the statewide average. Seven districts have both lower shares of teachers on emergency credentials and lower shares of low‑income students than the statewide averages. This differs from most other teacher‑related state programs, which target resources to subject areas and school districts where teacher shortages are most pronounced.

Evaluation of Classified Program to Be Released This Summer. As statutorily required, CTC has contracted with an independent program evaluator to complete and submit to the Legislature an evaluation of the Classified Program by July 1, 2021. Although the evaluation will not be available for the 2021‑22 budget deliberations, CTC shared with us their intent to incorporate any notable evaluation findings into the next application process.

Impact of Golden State Teacher Grant Remains Unknown, Could Be Limited. At the time of this analysis, the first round of Golden State Teacher Grants had not been awarded. As such, the state cannot yet measure the effect of the program on teacher supply. Several programmatic elements of the grants, however, could limit their effects. Although teacher candidates agree to teach in a low‑income school to receive funding, there is no guarantee they will ultimately teach at a low‑income school. For instance, the teacher candidate may not be able to secure employment at a low‑income school due to reasons beyond their control. Furthermore, there is no guarantee the teacher candidates would repay grant funding if they are unable to meet the program requirements. Moreover, the effectiveness of this grant as a recruitment incentive is limited. For example, it is possible that the program might provide grants to some teachers who would have taught at a low‑income school even without the grant.

Given Recent Influx of One‑Time Federal Funding, Schools Have Broad Options for Teacher Recruitment and Retention. With a total of $7.5 billion available across the two federal emergency relief packages, California public schools will have significant one‑time resources available to spend in 2021‑22. This is particularly the case for low‑income school districts, which received significantly more funding per student under the federal allocation formulas. Given the flexibility and local control over these federal funds, schools have a broad range of options to hire and retain qualified, prepared teachers, including teacher service awards, signing bonuses, or student debt payments. These approaches may be more responsive to local needs than state‑funded initiatives, such as those proposed by the Governor.

Recommendations

Reduce Proposed Teacher Residency Grant Program Augmentation to $50 Million, Reject Expanding to Other Shortage Areas. We recommend the Legislature provide $50 million (half the amount proposed by the Governor) for new residency programs in 2021‑22—roughly equivalent to the amount of funds awarded thus far. Given the challenges in building and sustaining these programs, we believe this amount is sufficient to address additional demand for new residency programs. We also believe the current program rules are more appropriately targeted than the Governor’s proposed change in addressing long‑standing shortage areas. As such, we recommend the Legislature reject the proposed change to broaden the funding to other subject areas as identified by CTC.

Target Classified Program to Shortage Areas. Given the substantial demand for the Classified Program, we recommend the Legislature approve the Governor’s proposal to provide $25 million for this program. In addition, we recommend several modifications to ensure the program is more directly targeted toward addressing teacher shortage areas. Specifically, we recommend giving priority to districts with higher shares of teachers on emergency credentials and higher shares of low‑income students. After reviewing the findings of the forthcoming evaluation, the Legislature also may want to revisit program rules in subsequent years.

Reject Golden State Teacher Grant Proposal. We recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to augment the Golden State Teacher Grant Program. Given that the first round of grant funding has not yet been allocated in the current year, the effect of the program on teacher supply remains uncertain. Moreover, by mainly focusing on teacher candidates still in preparation programs prior to securing a teaching job, the proposal cannot guarantee that grant funds will effectively address recruitment challenges in low‑income schools. Furthermore, the low‑income schools intended to benefit from this program have access to significant one‑time federal funding that provides broader flexibility to address these long‑standing recruitment challenges. Should the Legislature be interested in incentive funding for teachers, we suggest focusing efforts on expanding the total supply of teachers in shortage areas. For instance, the Legislature could instead consider targeting funding to expand enrollment in the integrated teacher preparation programs at the undergraduate level. Many other states currently offer this route into teaching. Under this approach, the state could increase the total supply of teachers by encouraging more undergraduate students to pursue teaching in a high‑need subject when they might have otherwise pursued another profession.

Professional Development

Below, we provide background on professional development for teachers, describe the Governor’s proposals to provide additional professional development for teachers and other school staff, and offer issues for the Legislature to consider.

Background

Professional Development Activities Are Locally Determined and Funded. Teachers and other school staff negotiate with their school district on the amount of required time dedicated to professional development each year. If these activities occur when school is not in session, the district typically compensates staff at a negotiated hourly or daily rate. If teachers attend professional development during the school day, the district generally must pay the cost of hiring a substitute teacher. The topics of the professional development also can be decided through collective bargaining. Outside of the negotiated activities, teachers and school staff may voluntarily participate in additional professional development opportunities. This time may also be compensated as determined in the local collective bargaining agreement.

Districts Receive Some Federal and State Funding for Professional Development. Districts primarily fund professional development through local general purpose funding (mainly through the Local Control Funding Formula). In addition, the federal government provides $210 million to California annually to support professional development activities. All districts receive this federal funding, but a majority of the funds go to low‑income districts and schools. Additionally, the state provides districts funding for mandated school staff trainings on HIV prevention education and mandated reporting of child abuse.

Districts Have a Variety of Options for Providing Professional Development. School districts have a variety of options for choosing how to provide training and resources to their employees. Many districts develop their own training and resources based on the specific needs of their workforce. For example, some districts set aside time for professional learning communities, where teachers from the same grade level or subject area work collaboratively to improve their teaching skills throughout the school year. In addition, districts can obtain professional development from a variety of local and state educational agencies, public universities, and various agencies associated with the statewide system of support. For instance, the University of California receives $7.6 million ongoing (state and federal funds) to support professional development in core subject areas through the Subject Matter Projects. These options can be free of charge or on a fee‑for‑service basis. Districts also may receive training from various private entities, including private universities and nonprofit organizations.

Governor’s Proposals

Provides $320 Million One Time for Various Professional Development Initiatives. Figure 3 summarizes the Governor’s professional development proposals, which include both previously funded and new initiatives.

Figure 3

Governor’s Budget Proposes $320 Million for Educator Professional Development

One‑Time Proposition 98 Unless Otherwise Indicated (In Millions)

|

Program |

Proposal |

Proposed Amount |

|

Previously Funded |

||

|

Educator Effectiveness Block Grant |

Provides grants to schools based on counts of teachers (estimated to be $800 per teacher). Funds could be used for training in a broad array of topics, including core academic subjects, social‑emotional learning, school climate, inclusive practices, and English learner supports. Available through 2024‑25. Last funded in 2015‑16. |

$250 |

|

MTSSa |

Provides schools grants to support MTSS implementation, including site‑specific coaching and staff compensation to complete training. Last funded in 2018‑19. |

30 |

|

Early Math Initiative |

Funds development of training and resources to improve math skills for children age eight and under. Received federal funding in 2018‑19. |

8 |

|

University of California Subject Matter Projects |

Provides $5 million for teacher training on learning recovery in core subject areas (such as math and language arts) and $2 million for training in ethnic studies. Received federal funding in 2020‑21. This program also receives $7.6 million ongoing through a mix of federal and state funds. |

7 |

|

Subtotal |

($295) |

|

|

Newly Funded |

||

|

Social‑emotional learning |

Provides funding to Orange and Butte COEs, in partnership with another educational entity or consortia, to develop resources, convene professional learning communities, and provide ongoing training on social‑emotional learning and trauma‑informed practices. |

$20 |

|

Ethnic studies |

Provides funding for one or more COEs to provide training on developing or expanding ethnic studies courses, including those aligned with the Model Curriculum to be adopted by SBE by March 31, 2021. |

5 |

|

Subtotal |

($25) |

|

|

Total |

$320 |

|

|

aMTSS is framework that integrates academic, social, and behavioral interventions in a multitiered approach. The broadest tier provides general supports for all students, with tiers escalating in intervention based on student needs. |

||

|

MTSS = multitiered system of support; COEs = county offices of education; and SBE = State Board of Education. |

||

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Block Grant Approach Would Give Districts Flexibility to Address Greatest Needs. In the fall of 2019, the California Department of Education conducted a survey of school staff to identify the key barriers to accessing professional development. Respondents most commonly identified a lack of time as a major barrier, followed by the cost of participating in training. Under the Governor’s block grant proposal, districts would have flexible funding to help address these underlying challenges. For instance, districts can use this funding to compensate staff for time spent on trainings and cover other associated training costs. By providing some flexibility over the focus of trainings, this approach also allows for professional development to be targeted to areas that would most benefit the teachers and other staff at each local school.

Recent Federal Funds Could Also Support Professional Development Activities. Since the recent federal funds can also support professional development activities, the Legislature may want to consider how the Governor’s proposals complement these funds and other funding dedicated to professional development. Providing block grant funding specifically for professional development would allow districts to use federal or local funds for other local activities. Alternatively, the Legislature could provide less funding for professional development and direct schools to rely on existing federal and local funds to cover these activities. This would free up one‑time Proposition 98 funds that the Legislature could dedicate to its other K‑12 priorities.

Most Targeted Proposals Are Addressing Specific Gaps in Training. Given most decisions about professional development are made locally, we think directing most professional development funding to districts makes sense. To the extent the Legislature wants to dedicate state‑level funding to develop additional training resources, we think it should consider whether the additional resources are addressing existing gaps in training. Most of the targeted proposals in the Governor’s budget address existing gaps. The Early Math Initiative, for example, provides training resources in an area where relatively few training resources exist. Providing training on the forthcoming ethnic studies model curriculum is reasonable, given elements of the guidance will be new to schools. We are less clear, however, on how the funding for Subject Matter Projects would address existing gaps. The proposal includes $5 million for learning recovery in core subject areas, but it is unclear how this would differ from other training currently provided through the program. Furthermore, the $2 million provided to the Subject Matter Projects for ethnic studies appears duplicative of the Governor’s other proposal on ethnic studies.

Consider Requiring Clear Deliverables and Expectations Tied With Funding for Targeted Proposals. The Governor’s budget includes very few details on the deliverables and expected activities to be funded under the subject‑specific proposals. For instance, the Early Math Initiative proposal does not specify the types of activities to be supported with additional funding. The Subject Matter Projects proposal does not clarify how the proposed one‑time augmentation would be used differently than ongoing funding currently provided to the program. The proposed funding for social‑emotional learning also lacks detail regarding the level of support this funding would provide for schools. The Legislature may want to establish a clear set of deliverables and expectations for each proposal that is approved to ensure funds are spent as intended and achieve the desired outcomes.