LAO Contact

February 26, 2021

The 2021-22 Budget

UC Programs in Medical Education

This post analyzes the Governor’s proposal to augment ongoing General Fund support for University of California (UC) Programs in Medical Education (PRIME)—a collection of medical school programs providing specialized instruction in health equity matters. The post first provides background about health equity and PRIME programs, then describes the Governor’s PRIME proposal, offers our assessment of the proposal, and gives several recommendations.

Background

UC Operates Six Medical Schools. In 2020‑21, UC is enrolling over 3,600 medical students across six medical schools. According to UC, these medical schools fund their operations primarily through a mix of core funding (state General Fund and student tuition revenue) and a portion of clinical revenues earned by medical school faculty. Historically, the state has not directly funded medical school operations or set medical school enrollment expectations in the annual budget act, instead leaving these decisions to campuses. In recent years, however, the state has allocated funds directly for certain medical education initiatives. Most notably, the state has supported the creation and development of the UC Riverside School of Medicine. The state also recently provided funding to expand the services of the UC San Francisco School of Medicine Fresno Branch Campus in partnership with UC Merced.

PRIME Trains Medical Students on Health Equity Matters. As Figure 1 shows, UC operates six PRIME programs. In 2020‑21, 365 students (around 10 percent of all medical school students) enrolled in PRIME programs. PRIME students receive a minimum of four years of training, the same length as their other medical school peers. Both PRIME students and other medical school students generally are required to complete two years of classroom instruction, followed by two years of clinical experiences in hospitals and other medical settings. Some of the courses PRIME students are required to take, however, are focused on health equity matters, and PRIME students’ clinical experiences tend to be focused on underserved populations and communities. Beyond the standard four‑year training program, a portion of PRIME students (as well as a portion of other medical school students) take additional coursework by pursuing a joint master’s degree requiring a fifth year of study (often in public health).

Figure 1

UC Medical Schools Run Six PRIME Programs

2020‑21

|

Campus |

Focus |

Students |

|

Los Angeles |

Underserved communities |

102 |

|

San Francisco/Berkeley |

Urban underserved |

75 |

|

Irvine |

Latino communities |

63 |

|

San Diego |

Health equity |

53 |

|

Davis |

Rural communities |

36 |

|

San Francisco/Fresno |

San Joaquin Valley |

36 |

|

Totals |

365 |

|

|

PRIME = Programs in Medical Education. |

||

State First Provided Funding Explicitly for PRIME in 2005‑06. UC Irvine was the first campus to develop a PRIME program, with its first class enrolled in 2004‑05. As with other UC medical school initiatives, UC Irvine funded its new PRIME program from within its campus support budget. In 2005‑06, the state began providing funds explicitly for PRIME programs and setting associated enrollment targets. Over the next five years, UC developed other PRIME programs, and the state provided additional funds for PRIME. Throughout these years, state funding for PRIME was linked to an underlying $15,000 per‑student funding rate. The rate was not tied to any particular formula and the basis for the amount was not specified in statute. It appears the rate was not intended to cover the full cost of the additional enrollment growth, with UC expected to fund the remaining costs using other sources, including general enrollment growth funds.

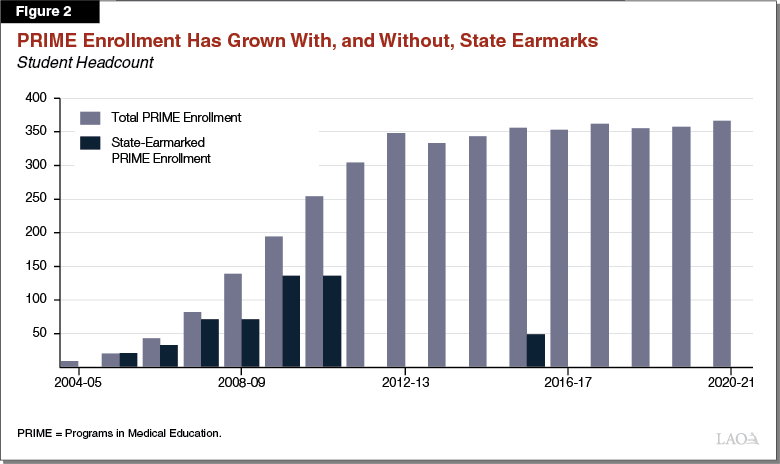

State No Longer Designates Funding Explicitly for PRIME. As Figure 2 shows, the state maintained and increased PRIME funding through 2010‑11. Though the state stopped designating funds for PRIME in 2011‑12, UC campuses continued to grow enrollment in these programs. The only additional funding the state has provided explicitly for PRIME since 2010‑11 was in 2015‑16, when it provided an ongoing augmentation for the San Joaquin Valley PRIME program. Specifically, the state provided $1.9 million ongoing General Fund to support enrollment of 48 students in this program. The underlying per‑student funding rate—$38,646—was higher than the $15,000 per‑student rate provided in previous years, with the rate intending to cover the full state cost of the program.

Growth in PRIME Reflects Notable Portion of Overall Medical School Growth. Since its inception in 2004‑05, PRIME has represented around 40 percent of the growth in UC medical school enrollment. Another roughly 40 percent has been concentrated at the UC Riverside School of Medicine, which enrolled its first class in 2013‑14. The remaining roughly 20 percent is from regular enrollment growth at UC’s other five medical schools.

Proposal

Governor Proposes Ongoing Augmentation for PRIME. The proposed augmentation in 2021‑22—$12.9 million—would fund enrollment growth in PRIME programs as well as enhancements among existing and new PRIME programs. Provisional language would require UC to spend one‑third of this amount ($4.3 million) on student financial aid. Below, we describe the components of this proposal in more detail.

Portion of Augmentation Would Support Enrollment Growth. UC attributes $4 million of the augmentation toward growing PRIME enrollment by 112 students over the next six years. As Figure 3 shows, 96 students would be in two new PRIME programs focused on American Indian/Alaska Native issues and Black health issues. The remaining 16 students would be across five of the existing PRIME programs. (UC plans to support an additional 12 students in the sixth program, San Joaquin Valley PRIME, using the funds it received in 2015‑16). According to UC, one‑third of the amount attributable to enrollment growth ($1.3 million) would cover financial aid for the additional students and the remainder ($2.7 million) would cover instructional costs (such as hiring new faculty). According to UC, the proposed per‑student funding rate for enrollment growth ($35,600) is the state rate provided to campuses for health science instruction under the university’s current allocation formula. (The nearby box explains the current methodology UC uses to distribute funds to campuses.)

Figure 3

UC Would Grow PRIME Enrollment Over the Next Six Years

Student Headcount

|

PRIME Program |

Actual 2020‑21 |

UC Enrollment Plan |

Change Over 2020‑21 |

|||||||

|

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

Los Angeles |

102 |

90 |

90 |

90 |

90 |

90 |

90 |

‑12 |

‑11.8% |

|

|

San Francisco/Berkeley |

75 |

75 |

75 |

75 |

75 |

75 |

75 |

— |

— |

|

|

Irvine |

63 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

‑3 |

‑4.8 |

|

|

San Diego |

53 |

51 |

53 |

55 |

56 |

58 |

60 |

7 |

13.2 |

|

|

Davis |

36 |

33 |

36 |

40 |

44 |

48 |

60 |

24 |

66.7 |

|

|

San Francisco/Fresno |

36 |

39 |

42 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

12a |

33.3 |

|

|

New (American Indian/Alaska Native) |

— |

12 |

24 |

36 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

New |

|

|

New (Black) |

— |

12 |

24 |

36 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

48 |

New |

|

|

Totals |

365 |

372 |

404 |

440 |

469 |

475 |

489 |

124 |

34.0% |

|

|

aUC plans to support this growth using funds the state provided in 2015‑16. PRIME = Programs in Medical Education. |

||||||||||

Overview of How UC Allocates State General Funds

Most Funding Allocated on a Weighted Student Basis. Since 2012, the University of California (UC) Office of the President has used a certain approach to allocate state General Fund across the UC system. Under this approach, the university first sets aside funds to cover certain systemwide and campus costs, such as systemwide debt service costs and study abroad programs. The university then allocates most of the remaining General Fund to eight of its ten campuses using a weighted per‑student formula. This formula provides a weight of 1 for undergraduate, graduate master’s, and professional enrollment excluding the health sciences; a weight of 2.5 for graduate academic enrollment at the doctoral level; and a weight of 5 for professional enrollment in the health sciences (consisting of medical schools, dentistry, optometry, and pharmacy, among other health programs). For the remaining two campuses—San Francisco and Merced—the university provides separate allotments that result in higher amounts of funding per student than for the other campuses. UC San Francisco’s per‑student funding is higher due to the school’s sole focus on health science instruction, whereas UC Merced’s per‑student funding is higher due to its relatively small size.

Remainder Would Bolster PRIME Funding. UC attributes the remaining $8.9 million toward enhancing support for the existing PRIME programs. According to UC, these funds would support enrollment growth from previous years that did not receive earmarked support in the state budget. One‑third of this amount ($3 million) would enhance student financial aid packages, potentially reducing debt burdens for some students and enabling more students to pursue the five‑year dual degree option. The remaining amount ($5.9 million) would be available to cover any other PRIME priority. In discussions with our office, UC suggested several uses of these remaining funds, including student and faculty recruitment, program administration, additional funds for financial aid, and additional funds for general medical school classes.

Assessment

Overarching Objectives of Proposal Have Merit, but Proposal Has Several Shortcomings. The Governor’s proposal highlights several longstanding health care issues in California. Research suggests that California could face a shortage of physicians in the future, particularly for primary care physicians. Data also suggest that there are existing disparities in health care across the state. The supply of physicians per capita varies among the state’s regions, with supply being the lowest in the San Joaquin Valley, Inland Empire, and Northern California. Health care utilization and the quality of care also varies substantially by race/ethnicity, and certain groups (such as Latinos) are underrepresented among California’s physician workforce. Given these issues, the Governor’s objectives to increase medical school enrollment and address health disparities are commendable. We are concerned, however, that the proposal has certain shortcomings, as described below.

Proposal Lacks Overall Medical School and Health Equity Plan. The administration’s proposal lacks key aspects vital to assessing its merit. First, neither the administration nor UC have shared with the Legislature their plans for UC’s overall medical student enrollment levels and how medical schools intend to cover the costs associated with any planned growth. Instead, the Legislature only has information for the fraction of UC’s medical students enrolled in PRIME. Second, while the proposed new programs identify populations with longstanding health disparities, UC does not appear to have a broader long‑term plan addressing the needs of other underserved regions and populations. Furthermore, the missions of UC’s existing PRIME programs do not seem well coordinated, with some focused on general health equity matters and others more targeted to specific regions and populations. Without better information, the Legislature would have little understanding as to how UC’s plans would meet state workforce needs and resolve longstanding inequities.

Proposed Budgetary Approach for Enrollment Growth Has Three Weaknesses. If UC were to have a comprehensive plan that considered enrollment across all of UC’s medical schools and PRIME programs, along with a funding strategy for supporting that enrollment, the Legislature would have the ability to assess how much additional enrollment to support with state funds. Though supporting some enrollment growth might be warranted, the Governor’s budgetary approach has certain shortcomings, as discussed below.

- Funding Would Be Provided Upfront. The Governor proposes providing all enrollment growth funding in 2021‑22, even though UC will not achieve full growth for several years. Providing all funds upfront weakens oversight and limits the Legislature’s ability to adjust support levels as new information becomes available. In this regard, the state’s experience with San Joaquin Valley PRIME serves as a cautionary lesson. Despite receiving upfront funds in 2015‑16 for 48 students, as of 2020‑21, the program enrolls 36 students and does not plan on attaining its target level of students until 2023‑24.

- Proposal Would Use Inconsistent Funding Rate. UC did not derive its proposed per‑student funding rate using a comparable methodology to its general enrollment growth formula. The general enrollment growth formula, known as the “marginal cost of instruction,” (1) makes key assumptions about education costs (such as a faculty‑student ratio), (2) explicitly excludes certain fixed costs that do not increase with enrollment, and (3) contains a method for attributing a share of the marginal cost to the state General Fund and student tuition revenue. Without a comparable formula for medical students, the Legislature has little basis to determine whether the proposed funding rate would appropriately align with programmatic costs.

- State Would Not Set Enrollment Targets. Despite UC having enrollment growth plans for PRIME, the Governor’s proposal does not link any additional funding to specific enrollment expectations. Such an approach weakens accountability and potentially creates confusion over how many additional students are to be enrolled.

Greater Clarity Is Needed on Financial Aid Objectives. Similar to funding enrollment growth, we think increasing student financial aid and reducing student debt could be reasonable objectives. As of this writing, however, neither the administration nor UC had provided a clear and comprehensive plan for addressing medical students’ debt levels. Such a plan would typically include a standard expectation of a manageable medical school debt level, the amount of available grant aid, and an estimate of the remaining unmet financial need. In the absence of this type of plan, the Legislature has little basis to determine whether the proposed set aside for financial aid would fulfill its intended purpose.

Unclear if Existing Programs Warrant Additional Funding. The university to date has not provided a clear rationale to bolster support for existing PRIME programs. While program enhancement could be warranted were PRIME programs to have gaps in service levels or outcomes, UC has not clearly documented these gaps. Despite UC’s claim that PRIME programs are underfunded by the state, virtually all students in PRIME graduate and are successfully placed in postgraduate residency programs.

State Lacks Consistent Reporting on PRIME Outcomes After Graduation. While UC reports high completion rates for its PRIME students, data on student postgraduate activities is incomplete. UC Irvine’s PRIME program, which focuses on serving Latino communities, has the most complete information on its graduates’ postgraduate activities. According to UC, 72 percent of practicing physicians from the UC Irvine program practice in county health facilities or federal qualified health centers, 66 percent work in practices that serve primarily low‑income patients, and 53 percent work in practices where a majority of patients are Latino. UC also provided data on UC Davis’ rural PRIME program, noting that 60 percent of its graduates practice in a rural area of the state. To date, however, the state does not have complete postgraduate data available for all of UC’s PRIME programs. The Governor’s proposal would maintain this information deficit, as it does not require any regular reporting on PRIME outcomes.

Recommendations

Direct UC to Develop Overall Medical School and PRIME Plan. We recommend withholding funds for enrollment growth in PRIME programs or any new PRIME programs until the administration and UC provide a plan for overall medical school enrollment, with a specific breakout for PRIME enrollment and detail on how the associated costs would be covered. The plan should also identify the remaining populations of Californians who are not adequately served by UC’s existing medical school programs and the actions UC will take to address these health disparities.

Phase in Funds, Develop Marginal Cost Formula, and Set Enrollment Targets. If the Legislature were to decide to fund growth in medical school enrollment or PRIME enrollment over a multiyear period, we recommend it develop an alternative budget approach. Under this alternative approach, the Legislature would phase in enrollment growth funding over multiple years. To assist medical schools in their planning, the Legislature could provide funds one year in advance of each cohort’s planned growth. The state already takes this approach when funding general campus enrollment growth. To determine funding levels, we recommend the Legislature direct UC to develop a marginal cost of instruction for medical education that is connected to anticipated education costs (excluding fixed costs) and devises a way to share these costs between state funding, student tuition, and faculty clinical revenue. Furthermore, any enrollment growth funds should be attached to explicit enrollment growth expectations to facilitate public accountability and legislative oversight.

Direct UC to Submit Plan on Addressing Unmet Student Financial Need. We similarly recommend the Legislature withhold additional funding for financial aid until UC provides a more specific estimate of medical students’ and PRIME students’ unmet financial need. Such an analysis should include an estimated cost of attendance, assumed student contribution amount through borrowing, an estimate of existing grant aid provided to students, and the remaining financial need to be addressed through additional grant aid.

If UC Wants to Enrich Programs, Stronger Case Needs to Be Made. Before providing any remaining funding for program enhancement, we recommend the Legislature direct UC to provide clearer documentation on its uses and projected improvements in outcomes resulting from these funds. If such documentation cannot adequately justify program enhancement funds, we recommend the Legislature redirect the remainder of the proposed funds toward other high budget priorities in 2021‑22.

Require Periodic Reporting. To aid legislative oversight and accountability, we recommend the Legislature require UC to report periodically (either annually or biennially) on PRIME activities and outcomes. At a minimum, the reports should include: (1) PRIME enrollment and student demographics in each program, (2) a summary of each program’s current curriculum, (3) graduation and residency placement rates, and (4) postgraduate data on where PRIME graduates are practicing and the extent to which they are serving the target populations and communities of their respective programs. If feasible, the reports should contain outcomes data for all student cohorts since 2004‑05.