LAO Contact

May 6, 2021

COVID-19

American Rescue Plan’s Major Health‑Related Funding Provisions

Introduction

On March 11, 2021, the President signed into law the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARP Act)—a $1.9 trillion coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) relief package. This post highlights the health-related provisions of the ARP Act that provide significant funding directly to state/local health care and public health agencies, rural hospitals, home- and community-based services (HCBS) programs, subsidized individual market health coverage programs, and public behavioral health services. Where possible, based on currently available information, we provide an estimate of the funding allocations to California governments and other entities in the state. While this post reflects our best understanding of the high-level content and implications of this legislation as of late April, we will update the post as new information and clarifications become available.

Funding for COVID-19 Testing, Treatment, and Vaccine Distribution/Administration

Funding to State and Local Governments for Testing, Contact Tracing, Lab Capacity, and Related Activities. The ARP Act includes $47.8 billion for COVID-19 testing, contact tracing, lab capacity, and related activities conducted at the national level and by state, local, and territorial governments. Thus far, the federal government has announced that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will provide $10 billion to states for COVID-19 screening testing of teachers, students, and staff to support school reopening. The California Department of Public Health (CDPH) will receive $887.7 million for this purpose, and Los Angeles County will receive its own direct CDC allocation of $302.4 million. While the federal government has announced other efforts to expand and support testing activities with ARP Act funding, such as providing $2.25 billion nationwide to address COVID-19-related health inequities among communities of color and among people living in rural areas, further CDC allocations from the ARP Act to states for testing, contact tracing, mitigation, and laboratory capacity await future announcement from CDC. This most recent allocation builds on prior CDC funding of more than $2.3 billion to CDPH (and more than $900 million directly to Los Angeles County) over the course of the pandemic for COVID-19-related activities. About two-thirds of what CDPH has received thus far has been passed on to the state’s local health jurisdictions to carry out COVID-19 response at the local level.

Funding to State and Local Governments for Genomic Sequencing to Fight COVID-19 Variants. COVID-19 variants comprise an increasingly large share of positive COVID-19 cases and continue to grow in number. The ARP Act provides $1.75 billion to strengthen and expand genomic sequencing activities, analytics, and disease surveillance to identify mutations and develop disease response. Thus far, the federal government has announced $1.7 billion in funding for these purposes, including an initial CDC allocation of $240 million to states and select local governments, which will be distributed in early May. A second allocation will be provided over the next several years. California is set to receive $17.1 million from the initial allocation and Los Angeles County will receive $6.4 million.

Funding to State and Local Governments for Vaccine Distribution and Administration. The ARP Act provides $7.5 billion for COVID-19 vaccine-related activities, including planning, distribution, administration, and tracking. California will receive $357 million from CDC for these purposes (in this case, Los Angeles County does not receive a separate allocation). This funding builds on earlier federal allocations to states for vaccine-related activities, including $357 million awarded to California from the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2021.

Modifies Medicaid Coverage of COVID-19 Vaccinations and Treatment. The ARP Act includes several statutory changes that expand or clarify Medicaid policy related to COVID-19 vaccinations and treatment. These changes affect the funding needs and flexibilities of Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid program, and are summarized in the following bullets.

-

Increases Federal Medicaid Funding for COVID-19 Vaccine Administration. From April 2021 through one year after the national COVID-19 Public Health Emergency has ended, the federal government will pay 100 percent of the cost of COVID-19 vaccines, including their administration, provided to Medicaid beneficiaries. While the Governor’s budget released in January 2021 had assumed the federal government would pay for 100 percent of the costs of the vaccines themselves, the budget assumed the state would share in the cost of the vaccines’ administration to Medi-Cal beneficiaries. We estimate this increase in federal funding will save the state around $100 million in General Fund through the end of 2021‑22.

-

Clarifies the Extent of Medicaid Coverage of COVID-19 Vaccines. Previous COVID-19-related federal legislation required state Medicaid programs to cover COVID-19 testing and treatment without imposing a share of cost on Medicaid enrollees. The ARP Act clarifies that coverage of COVID-19 treatment—and the related prohibition on cost sharing—includes COVID-19 vaccines and their administration.

-

At States’ Option, Provides Federal Funding for COVID-19 Treatment for Uninsured Population. Previous COVID-19-related federal legislation offered state Medicaid programs the option to cover the cost of COVID-19 testing for the uninsured at a 100 percent federal share of cost. California took up this option and went further by extending Medi-Cal coverage to treatment of COVID-19 for the uninsured. The Governor’s January 2021 budget assumed the cost of providing COVID-19 treatment to the uninsured would be 100 percent state funded. Starting in March 2021, the ARP Act expands Medicaid coverage to treatment of COVID-19, with the federal government paying for the entirety of the costs. We estimate that this will result in General Fund savings in the low tens of millions of dollars.

Funding to Community Health Centers for Testing, Contact Tracing, and Vaccine Administration. Community health centers are a major provider of safety net primary care services in California. The ARP Act provides $7.6 billion nationwide for health centers for COVID-19 vaccine distribution, testing, and contact tracing, as well as the expansion of workforce efforts to support these efforts (through equipment, staff, or other infrastructure). Of the $7.6 billion, we estimate that California-based health centers will receive about $1 billion in funds.

Enhanced Federal Funding for HCBS

State Currently Spends Over $20 Billion on HCBS. HCBS include a variety of services for persons with functional limitations that are intended to help them avoid requiring care in institution, such as a nursing home. Common HCBS include nurse visits, personal care services, home modifications such as the installation of ramps, home-delivered meals, and adult daycare. California operates a variety of Medicaid-funded HCBS programs, including, for example, the In-Home Supportive Services program administered by the Department of Social Services, the Department of Developmental Services’ HCBS program, and the Assisted Living Waiver program administered by the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS). We estimate that California currently spends over $20 billion annually across the state’s various HCBS programs. The federal government typically pays 50 percent or 56 percent of HCBS costs, with the state General Fund usually covering the nonfederal share.

ARP Act Temporarily Enhances Federal Funding for State HCBS Program Improvements. The ARP Act increases the federal government’s share of Medicaid-funded HCBS by 10 percentage points during a “program improvement period” of April 1, 2021 through March 31, 2022. To qualify for this enhanced federal funding, states must “expand, enhance, or strengthen” their HCBS services. Moreover, the ARP Act requires that the increased funding shall supplement, and not supplant, the level of state funds expended for HCBS services as of April 1, 2021.

Outstanding Questions Around the Requirements for This Enhanced Federal Funding. As of the publication date of this post, we have a number of outstanding questions about how the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (which oversees Medicaid) will interpret, operationalize, and enforce the requirements on states for receiving the enhanced federal HCBS funding. (DHCS previously communicated that it similarly believes further clarification from the federal government is necessary.) Our outstanding questions include: (1) how states should calculate the potential amount of additional federal funding; (2) what the state’s share of cost would be for new HCBS spending; (3) whether there would be any flexibility associated with the non-supplantation clause; (4) what would be considered an allowable expenditure to expand, enhance, or strengthen HCBS services; and (5) whether funds would have to be appropriated, encumbered, or spent by March 31, 2022. These outstanding questions make it impossible at this time to estimate a fiscal impact of this new opportunity for enhanced federal funding.

New State Option to Extend Medicaid Coverage for Postpartum Women

Current Federal and State Medicaid Policy on Coverage for Postpartum Women. As authorized by federal law, Medi-Cal currently provides time-limited coverage to pregnant women who do not meet all standard Medi-Cal eligibility rules, such as those with incomes above 138 percent of the federal poverty level. In general, this coverage remains in place for 60 days following childbirth, after which their eligibility ends. In 2020, the state Legislature approved an extension of Medi-Cal coverage for postpartum women with mental health conditions to 12 months after childbirth. Because federal rules limit Medicaid coverage to 60 days following childbirth, the cost of extending postpartum coverage from 60 days to 12 months for women with mental health conditions is incurred entirely by the state. The administration has assumed the annual cost of the state’s extension of postpartum coverage would be $34 million General Fund.

New State Option to Further Extend Medicaid Coverage for Postpartum Women. The ARP Act temporarily gives states the option to extend Medicaid (and Children’s Health Insurance Program) coverage to all postpartum women to 12 months after childbirth. (California’s Children’s Health Insurance Program is consolidated with the state’s Medicaid program under Medi-Cal.) For states that opt in, the federal government would share in the cost of providing extended postpartum coverage according to standard federal-state cost-sharing rules. This state option is available from April 1, 2022 through March 31, 2027. Opting in would bring new state (as well as federal) costs of an unknown amount. However, a portion of any new state costs likely would be offset by state savings from the federal government beginning to share in the cost of the extended postpartum coverage that the state currently offers to women with mental health conditions. Whether the state could elect to only extend postpartum coverage for women with mental health conditions and obtain federal funding under the ARP Act’s new state option is unclear.

Funding for Public Health Workforce

The ARP Act provides $7.66 billion to support and sustain the public health workforce. While funding will be provided to state, local, and territorial public health departments, the specific allocations have not yet been announced. The ARP Act funding will support costs associated with recruiting, hiring, and training individuals for various positions, including case investigators, contact tracers, social support specialists, community health workers, public health nurses, disease intervention specialists, epidemiologists, program managers, laboratory personnel, and communication and policy experts. Throughout the pandemic, CDPH and the state’s 61 local health jurisdictions have been responsible for a wide range of COVID-19-related activities and have had to rapidly expand their workforce—by redirecting staff from other assignments or departments and by hiring new staff (often temporary or contract staff). Previous CDC grants for COVID-19 activities have helped to fund these public health workforce expansions. Whether this new ARP allocation from the CDC can be used to retroactively pay for the costs associated with these previous hires (if it were needed) is not clear yet. We await future guidance from CDC to provide this clarification.

Relief Funding for Rural Hospitals

The ARP Act makes available $8.5 billion in funding nationwide for rural hospitals that provide diagnosis, testing, or care for individuals who have COVID-19 or are suspected of having COVID-19. (Notably, this funding is being provided separately from the Provider Relief Fund established in prior federal COVID-19 relief legislation.) This funding may be used for a variety of purposes, such as leasing properties, setting up temporary structures for treatment activities, retrofitting facilities, purchasing medical supplies and equipment, and bringing on and training additional health care workers. The funding also may be used to offset lost revenues resulting from the COVID-19 outbreak, such as those associated with hospitals cancelling elective procedures to free up capacity to address the COVID-19 outbreak. Of this $8.5 billion, we estimate that rural hospitals in California will receive about $250 million in funds.

Temporary Increase in Support for Individual Market and Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance

Higher Health Insurance Premium Subsidies for Individuals Purchasing Coverage Through Health Benefit Exchange. California residents who do not receive health care coverage through their employers or from government programs can purchase individual coverage through a centralized health insurance marketplace known in California as the California Health Benefit Exchange (Covered California). Since 2014, under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), the federal government has provided subsidies to individuals who purchase coverage through the health benefit exchanges provided they meet income-eligibility rules. In 2020, around $7 billion in federal health insurance subsidies were provided through Covered California. To further improve the affordability of individual health insurance coverage, in 2020, the state began funding additional state subsidies on top of those from the federal government. The administration projects $355 million General Fund in 2020‑21 and $406 million General Fund in 2021‑22 will be used for subsidies (this funding, respectively, funds the state subsidies for the 2021 and 2022 calendar years). Both the federal and California governments set subsidies at levels that ensure state residents only need spend a given percentage of their income on health insurance premiums purchased through Covered California.

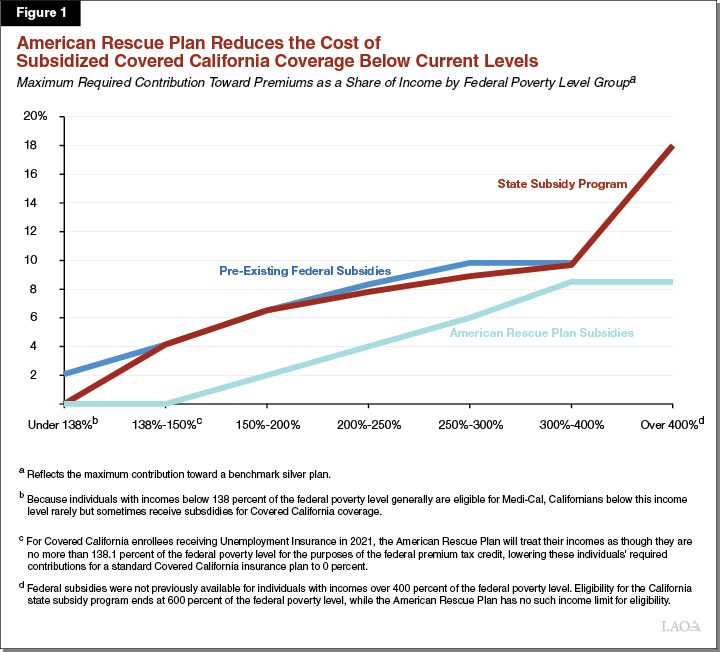

The ARP Act temporarily increases federal support for health insurance coverage purchased through the ACA health benefit exchanges. Across calendar years 2021 and 2022, Covered California projects the ARP Act will provide an additional $3 billion in federal support for health insurance subsidies. In 2021, the ARP Act’s higher subsidies will begin to be made available through Covered California from May 1, 2021 onward. According to the Department of Finance, the ARP subsidies will be adjusted upward for the months of May 2021 through December 2021 to retroactively ensure customers receive the higher subsidies for the first four months of 2021. Figure 1 shows how this additional federal support will further limit the percentage of their incomes Californians would have to spend to purchase health insurance coverage. The blue line shows how the ACA limited the percentage of incomes subsidized health insurance purchasers would have to spend on premiums. The red line shows how California’s state subsidy program further reduced the percentage of incomes subsidized Californians would have to spend on premiums. For Californians with incomes below 400 percent of the federal poverty level, the decrease was marginal—for example, for Californians with incomes equal to 300 percent of the federal poverty level, the state subsidy program reduces the percentage of income they would have to spend on premiums from about 9.8 percent to 8.9 percent. However, for Californians with incomes above 400 percent of the federal poverty level, the state subsidy program for the first time placed a limit on the percentage of income individuals would have to spend on premiums. The green line shows how the ARP Act goes beyond the level of subsidies provided by the state subsidy program across all income groups.

The ARP Act’s subsidies are more generous than those currently provided by the state subsidy program. Accordingly, we understand that the new federal subsidies free up the General Fund currently allocated to state subsidies. This presents the Legislature with an opportunity to either redesign the state subsidy program, such as by using the funding to lower Covered California consumer deductibles or further lower premiums, or redirect the General Fund currently allocated to Covered California to other purposes.

Temporary Subsidies to Help Workers Who Lose Employer-Sponsored Insurance Retain Their Health Benefits. Longstanding federal law gives workers who lose their employer-sponsored health insurance the opportunity to maintain the coverage provided by their employee health plan after the termination of their employment or other changes that otherwise would result in the loss of coverage (such as a change from full- to part-time employee status). This coverage option is known as “COBRA” coverage and is required to be available for a limited period of time after the coverage otherwise would have ended. Individuals who opt into COBRA coverage may be required to pay their entire premium in order to retain coverage. The ARP Act temporarily subsidizes COBRA coverage for individuals who involuntarily have lost their employer-sponsored health insurance due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This temporary federal subsidy covers the entire cost of COBRA coverage for the period of April 1, 2021 through September 30, 2021.

Funding for Behavioral Health Services

Funding for Behavioral Health Nationwide. The ARP Act makes available $3.9 billion in funding nationwide for behavioral health programs to respond to the COVID-19 outbreak, most of which is available as grant funding for states or local entities. This funding is allocated as follows:

-

$3 Billion for Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Block Grant Programs. SAMHSA administers two federal grant programs—the Community Mental Health Services Block Grant and the Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment Block Grant—which provide formula-based grant funding to states for mental health and substance use treatment, respectively. The ARP Act makes available $1.5 billion in funding nationwide for each program, for a total of $3 billion. About $200 million will be allocated to California for each program, for a total of $400 million.

-

$900 Million for Other Behavioral Health Programs. The ARP Act makes available about $900 million in funding nationwide for other behavioral health programs to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, this funding includes (1) $420 million to expand a program which certifies community behavioral health clinics so they can receive an enhanced federal reimbursement rate, (2) $100 million for a program intended to increase the number of behavioral health practitioners nationwide, and (3) $80 million for a program intended to promote behavioral health integration in pediatric primary care through telehealth. Of this $900 million, we estimate the amount that will be provided to California to be in the tens of millions of dollars.

Enhanced Federal Funding for Mobile Crisis Services. The ARP Act makes available an option for states to receive enhanced federal funding—85 percent of costs—through Medicaid for mobile crisis intervention services for beneficiaries experiencing a behavioral health crisis. The ARP Act also makes available $15 million in planning grant funding available nationwide for states to develop strategies (such as Medicaid state plan amendments or amendments to federal Medicaid waivers) for adding mobile crisis services to their state Medicaid programs. Furthermore, the ARP Act requires that the increased funding shall supplement, and not supplant, the level of state funding for mobile crisis services just prior to implementation of this new Medicaid option.

In California, counties are responsible for providing behavioral health services for Medicaid beneficiaries with severe behavioral health needs (and for providing the nonfederal share of cost for these services in most cases). Currently, counties are able to receive federal reimbursement through Medicaid for crisis intervention services provided in the community. However, the extent to which they elect to establish mobile crisis teams to provide these crisis intervention services is unclear. (We note that in 2013, the state established a grant program—funded through the Mental Health Services Fund—which provided funding to counties that could be used to establish these mobile crisis teams.) Similar to our earlier discussion on enhanced federal funding for HBCS, we have a few outstanding questions about this new enhanced federal funding opportunity. These include (1) whether the mobile crisis services referenced by the ARP Act are directly comparable to the current crisis intervention services provided by California counties in the community, (2) whether the state would be required to submit a Medicaid state plan amendment or an amendment to a federal Medicaid waiver to access this enhanced federal funding, and (3) how the ARP Act’s non-supplantation language—which references the level of state funding—would be applied to California (since counties provide most of the nonfederal share of funding for these services). Given these questions, we are unable at this time to estimate a fiscal impact to California of this new opportunity for enhanced federal funding.