May 7, 2021

COVID-19

Impact of COVID-19 on Health Care Access

Summary

This post describes how coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has affected access to health care in California through the earliest months of 2021. Specifically, we describe four trends that together shed significant light on the impact of COVID-19 on access to health care. These trends are: (1) changes in how many Californians have health care coverage, (2) how health care employment has changed, (3) how health care utilization patterns have changed, and (4) to what extent Californians have reported delaying or foregoing health care.

Health Care Coverage Has Not Declined as Anticipated. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic coincided with the largest and swiftest job losses in recent state history. State policymakers expected that a surge in health care coverage losses would accompany the job losses. However, health care coverage losses did not materialize at similar magnitudes as job losses. Rather, health care coverage has either remained steady or potentially increased during the pandemic. While there have been losses in job-based health care coverage, these losses have been more than offset by increases in other forms of coverage, primarily Medi-Cal coverage. In this post, we provide a number of potential reasons why health coverage and job loss trends might not be moving together.

Health Care Employment Declined Significantly, Though Unevenly, Across Provider Types. Health care employment in California declined significantly in the initial months of the pandemic, though not as severely as employment overall. As with employment overall, health care employment has partially recovered since then. However, the health care employment declines—and corresponding recoveries—have varied across health care service types. For example, by the summer of 2020, total employment at California skilled nursing facilities had declined to around 10 percent and has not recovered since.

Health Care Utilization Plunged After Onset of COVID-19, but Largely Has Recovered. Quarterly utilization of health care services in California declined precipitously with the start of the pandemic. However, by the end of 2020, total service utilization had largely recovered. This recovery has been uneven across different types of health care services. For example, while hospital stays rose to far surpass 2019 levels in the last quarter of 2020 (potentially driven by the late-year surge in COVID-19-related hospitalizations), physician encounters only partially recovered.

Takeaways and Policy Options. We end the post by bringing up key takeaways, outstanding questions, and issues for legislative consideration. First, while access to care is trending toward pre-pandemic levels, continued monitoring of these trends is warranted. Second, there are a number of outstanding questions, such as whether lower health care employment is continuing to impair access and whether there is significant pent-up demand for services. Third, we provide several policy options that the Legislature could consider for sustaining and improving access to care. These include (1) funding additional outreach activities to encourage health care coverage enrollment as public health and labor market conditions improve (which could cause a significant number of Medi-Cal enrollees to lose their Medi-Cal income-eligibility), (2) funding or making policy changes to address a deficit in children’s preventive services that has arisen among Medi-Cal-enrolled children during the pandemic, and (3) initiating efforts to improve the timeliness of data collection and reporting on health care access.

Introduction

This post describes how COVID-19 has affected access to health care in California through the earliest months of 2021. Specifically, we describe four trends that together shed significant light on the impact of COVID-19 on access to health care. These trends are:

Health Care Coverage. Whether someone has health care coverage is a key factor in determining whether they have access to health care. We use two data sources to show how health care coverage has changed in California under COVID-19.

State oversight of health care coverage providers is split between two regulators: the Department of Managed Health Care (DMHC) and the California Department of Insurance. DMHC oversees all Health Maintenance Organization (managed care) products and some preferred provider organization (PPO) products, while the California Department of Insurance oversees the remaining PPO products and all traditional indemnity health insurance products. For this post, we refer to health care coverage providers overseen by DMHC as health plans and those overseen by the California Department of Insurance as health insurers. Our primary health care coverage data source is health plan enrollment data reported to DMHC by the state’s 44 major health plans. Roughly, 70 percent of Californians obtain health care coverage from one of these health plans. The DMHC data on health plan enrollment are reported quarterly and have been collected both prior to and during the pandemic, allowing comparison to the pre-pandemic period (before March 2020).

We also report trends from the Household Pulse Survey, which the U.S. Census Bureau has conducted regularly since close to the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. This data source provides information on how the uninsured rate among adult Californians has evolved under the pandemic. (Since the health plan enrollment data only captures coverage from certain sources, it does not show the uninsured rate.) Because this survey was initiated about two months into the pandemic (at the end of April 2020), it does not allow for direct comparison of the uninsured rate throughout the pandemic to the rate before the pandemic began.

Health Care Employment. In addition to health care coverage, whether health care services are available will affect an individual’s ability to access care. Put another way, having health care coverage does not guarantee that there is a sufficient supply of services available to provide to someone to ensure access to care. While comprehensive data on the amount of health care services available statewide are not available, the level of employment in the health care sector can be used as a proxy for the available supply of health care services. (The number of health care providers per person is a common measure of access to care.) To show how health care employment has changed in California under COVID-19, we use employment data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which show employment levels across various health care facility types statewide. (One limitation of this data source is that it includes non-health care provider positions that are employed in health facilities, such as office or administrative staff.) These data are reported monthly and have been collected both prior to and during the pandemic.

Utilization of Health Care. Data reported by health plans to DMHC contain information on the utilization of health care services by their members. Because these data have long been reported by plans, they show how utilization trends under the pandemic have diverged from pre-pandemic trends. As with the health plan enrollment data, these health care utilization data are broken out among several service categories. Because this data source includes utilization for enrollees of the state’s 44 major health plans overseen by DMHC, it covers utilization for nearly 70 percent of state residents.

Self-Reported Foregone and/or Delayed Health Care. In addition to inquiring into respondents’ access to health care coverage, the Household Pulse Survey asks respondents whether they have foregone or delayed health care during the pandemic. As with the Household Pulse Survey data on health care coverage, the survey cannot be used to compare the extent to which residents forewent or delayed care pre-pandemic. The survey does not include follow-up questions on exactly why respondents had foregone or delayed care. Accordingly, this data source does not indicate whether respondents had foregone or delayed health care due to the lack of availability of services or hesitation to seek care amidst the pandemic.

Health Care Coverage Has Not Declined as Anticipated

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic coincided with the largest and swiftest job losses in recent state history. State policymakers expected that a surge in health care coverage losses would accompany the job losses. However, as we lay out in this section, health care coverage losses did not materialize at similar magnitudes as job losses. Why job losses have widely outpaced health coverage losses is not entirely clear. Later in this post, we provide reasons why the health coverage and job loss trends might not be moving together.

Health Plan Enrollment

Background. Over 26 million Californians (nearly 70 percent) obtain health care coverage from a health plan. The remaining 14 million state residents generally obtain health care coverage from insurers (usually PPOs) overseen by the state Department of Insurance (6 million state residents), Medicare fee-for-service (around 3.5 million state residents), Medi-Cal fee-for-service (over 1 million state residents), or are uninsured (between 2 million and 3 million state residents). On a quarterly basis, DMHC collects reports from health plans on their enrollment numbers. The reports break down health plan enrollment by coverage type—that is, the reports show whether members have coverage that is job-based or through the individual market, Medi-Cal (the state’s Medicaid program), or Medicare Advantage (Medicare’s managed care program). Because health plans cover a relatively large share of the state’s population, these quarterly reports help show how overall health care coverage trends have evolved over the course of the pandemic.

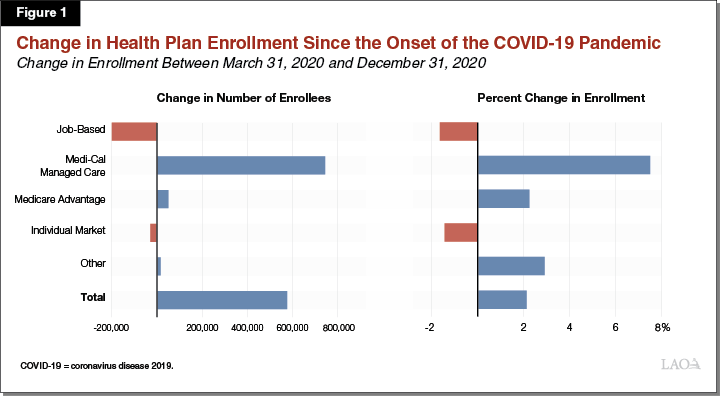

On Net, Overall Enrollment in Health Plans Has Grown, Rather Than Declined, Under the Pandemic. In terms of health care coverage, we would expect March 2020 to be the last largely normal month before the pandemic took hold. Therefore, changes in enrollment after March 2020 indicate the potential impact of COVID-19 on health care coverage. Between March 2020 and December 2020, enrollment in the state’s 44 major health plans increased on net by about 600,000 members (2 percent). This increase stands in contrast to what occurred over the nine month period between March and December period in 2019, when total health plan enrollment decreased by about 200,000 members (1 percent). However, there were significant changes in the types of health plan coverage that Californians obtained. Figure 1 shows the net changes in health plan enrollment between March 2020 and December 2020 by type of coverage.

Enrollment in Job-Based Coverage Has Not Declined as Severely as the Deterioration of the Labor Market Would Indicate. By April 2020, the state lost over 2.6 million jobs (15 percent). Subsequent months saw some recovery in the job market—cumulative net job losses since the onset of the pandemic decreased to around 1.8 million in July 2020 and 1.5 million in December 2020. Because nearly half of Californians have job-based health care coverage, the unprecedented job losses under the pandemic were expected to result in the widespread loss of health care coverage. However, losses in job-based coverage appear to be far smaller than losses in jobs. Between March 2020 and December 2020, health plan enrollment in job-based coverage fell by around 200,000 members. While similar data from the California Department of Insurance is not available, if enrollment in job-based coverage declined at a similar rate among health insurers regulated by the California Department of Insurance as it has for health plans overseen by DMHC, we would estimate that the total decline in job-based coverage among Californians is about 300,000 as of December 2020. This reflects a 2 percent decline in job-based coverage, compared to an 8 percent decline in total jobs in the state. By comparison, the same period in 2019 saw a 1 percent increase in job-based coverage.

Increased Enrollment in Other Forms of Health Plan Coverage More Than Offsets the Declines in Employer-Sponsored Coverage. Medi-Cal managed care enrollment has surged under the pandemic, growing by nearly 750,000 members (8 percent) between March 2020 and December 2020. This contrasts to a 3 percent decline in Medi-Cal managed care enrollment over the same period in 2019. While some of this growth in Medi-Cal managed care enrollment likely is due to state residents transitioning from job-based or individual market coverage to Medi-Cal coverage, much of this growth likely is due to greater continuity of coverage among previously enrolled Medi-Cal managed care enrollees. (This greater continuity of coverage for Medi-Cal managed care members likely is largely the result of a COVID-19-related federal rule change that effectively prohibits the state from terminating the eligibility of current Medi-Cal enrollees, except in limited circumstances, until after the associated national public health emergency ends.) Medicare Advantage enrollment also increased (in this case, modestly by around 2 percent) since the onset of the pandemic (in concert with pre-existing trends), while individual market enrollment declined by around 1 percent.

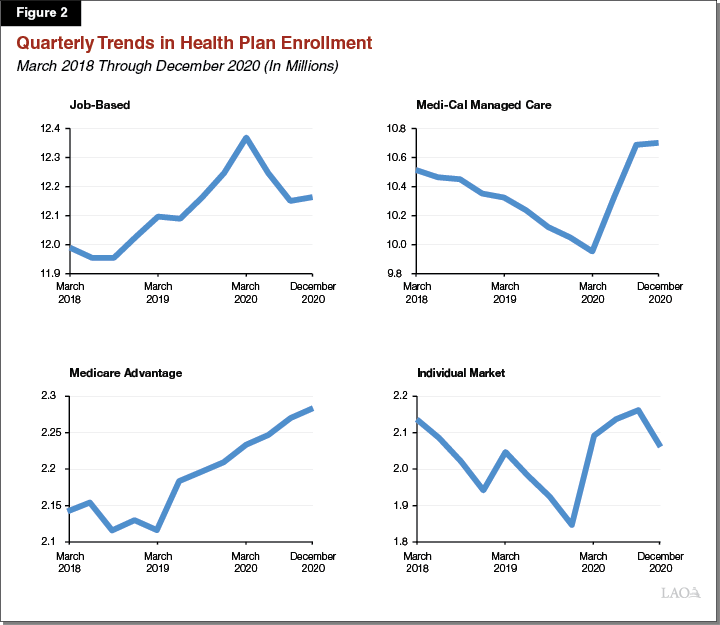

Enrollment Trends Under the Pandemic May Be Changing Course. Health plan enrollment under COVID-19 reveals three noteworthy trends: (1) a less-than-anticipated but nevertheless large decline in job-based coverage, (2) a substantial increase in Medi-Cal managed care plan enrollment, and (3) an overall net increase in enrollment. However, these trends have not been entirely consistent throughout the pandemic. Figure 2 shows three years of data on health plan enrollment broken down by type of coverage. The figure shows that job-based coverage declined swiftly over the first six months of the pandemic between March 2020 and September 2020. By December 2020, however, the decline in job-based coverage reversed itself and instead there was a modest, roughly 10,000 member increase in job-based coverage enrollment. Medi-Cal managed care enrollment trends also changed course. Rather than increasing at a rate of well over 100,000 members per month, as was the case between March 2020 and September 2020, Medi-Cal managed care plan enrollment increased by less than 5,000 members per month between September 2020 and December 2020. Enrollment through the individual market also exhibited changing trends. While individual market enrollment had increased by almost 70,000 members between March 2020 and September 2020, enrollment in this coverage type fell by around 100,000 members between September 2020 and December 2020.

No Sustained Increase in Uninsured Californians

In 2019, nearly 9 percent of adult Californians were uninsured. Data from the Household Pulse Survey suggest that, during the initial months of the pandemic, the share of the state’s adult population without health insurance hovered around or marginally increased above pre-pandemic levels, reaching roughly 10 percent in the summer months of 2020. By the fall of 2020, however, the share of adult Californians without health insurance declined to rates that may be lower than pre-pandemic levels. (Because this data source is based on survey responses from fairly small samples, the estimates are imprecise, making it difficult to determine whether more recent monthly uninsured rates have indeed dipped below or are roughly equivalent to pre-pandemic levels.)

Access to and Utilization of Health Care Declined, Followed by a Partial Recovery

In this section, we use three metrics to assess access to and utilization of care. First, we describe how employment within the health care industry has evolved over the pandemic, which helps show the extent to which health care professionals have been available to take appointments. Second, we describe trends in the utilization of health care services under the pandemic. This information helps to show the extent to which access has been realized through the successful completion of a health care visit or procedure. Third, we summarize data showing the extent to which Californians have reported delaying or foregoing care during the pandemic. This third data set is relevant as the utilization trends on their own may misleadingly infer that lower utilization during the pandemic is solely due to the lack of availability of services. Rather, a component of the survey responses on foregone/delayed care potentially reflects care that has been foregone/delayed given lower willingness to visit a health facility due to COVID-19 risks.

Health Care Employment

As discussed earlier, the level of employment in the health care sector can be used as a proxy for the amount of health care services—and providers—that are available statewide to ensure access to health care. In general, access to health care (in terms of amount of services available) declined in the initial months of the pandemic, but has partially recovered since then. However, as we discuss in this section, employment declines—and corresponding recoveries—have varied across health care service types.

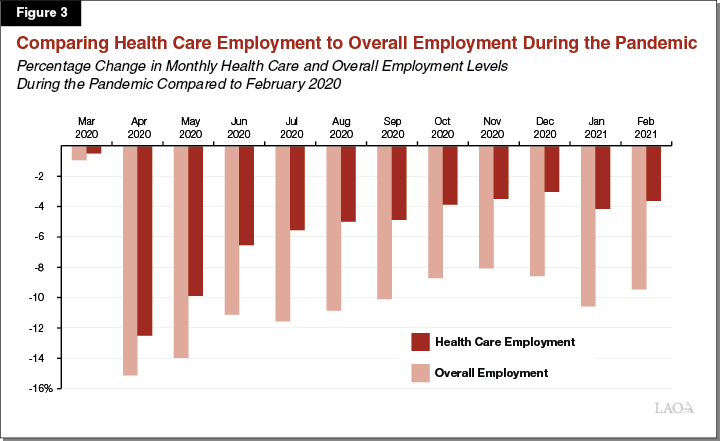

Health Care Employment Declines Under the Pandemic Not As Pronounced as Overall Employment Declines. In the months leading up to the pandemic, employment growth in health care outpaced overall employment growth. For example, in February 2020, total employment in health care statewide was 3 percent higher than in February 2019, while total overall employment statewide was just 2 percent higher across the same time period. While the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in dramatic job losses statewide, the decline in health care employment—while still substantial—has not been as pronounced as the decline in overall employment. For example, in April 2020, total overall employment statewide declined by 15 percent relative to February 2020, while total health care employment declined by 13 percent across the same time period.

Furthermore, following an initial sharp decline in employment in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the health care sector has experienced a more pronounced statewide employment recovery compared to overall employment in the months since. Figure 3 compares these trends. As seen in the figure, in February 2021, total health care employment was just 4 percent lower than in February 2020, while total overall employment statewide was 9 percent lower across the same time period. Notably, the recoveries in both health care employment and overall employment statewide stagnated in the early months of 2021, which may in part be due to higher rates of transmission during the winter months.

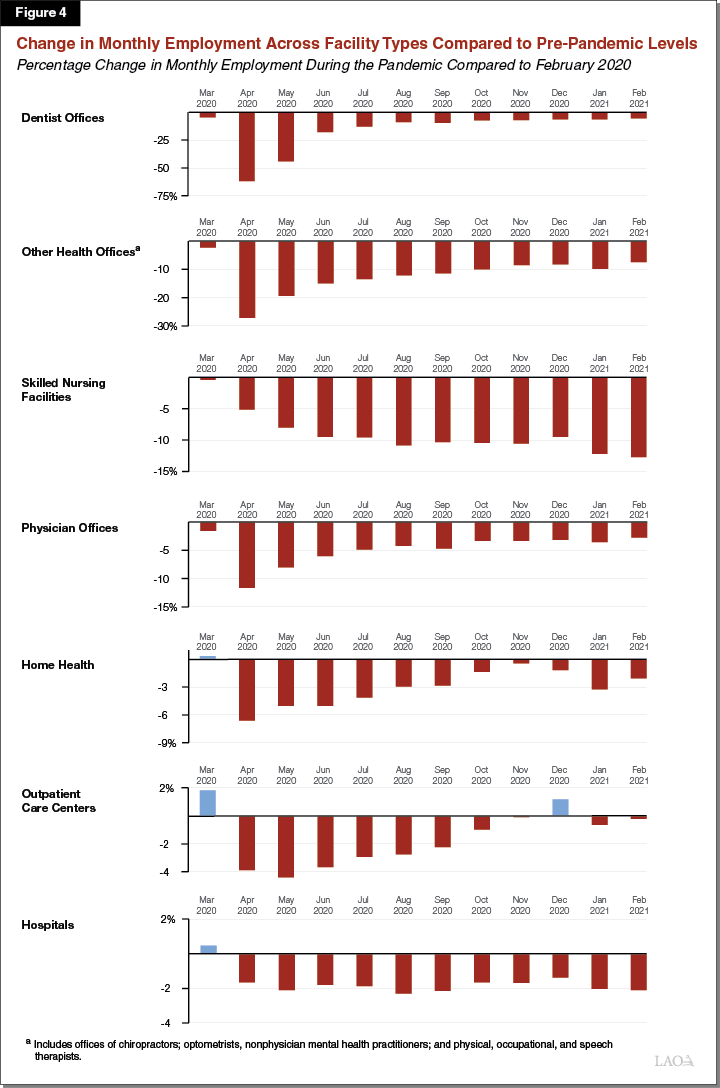

Employment at Health Care Facilities Declined During the Initial Months of the Pandemic, to Varying Degrees. As discussed earlier, health care employment in general experienced a substantial decline in the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, as shown in Figure 4, the degree to which employment levels changed after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic varied substantially by health care provider type. For example, statewide employment at dentists’ offices experienced a much more severe decline relative to other health care provider types. (Total employment at dentists’ offices in California declined by 62 percent in April 2020 relative to February 2020.) In contrast, employment at hospitals declined by just 2 percent across the same time period.

Employment Recovery Has Been Uneven Across Health Care Provider Types. As shown in Figure 4, the employment recovery has been uneven across health care provider types. For example, although dentists’ offices experienced the most severe job losses in the early months of the pandemic, they also experienced the most dramatic rebound when compared to other health care providers. (Total employment at dentists’ offices in California was just 6 percent lower in February 2021 compared to February 2020.) In contrast, total employment at hospitals has not recovered since the initial decline (of around 2 percent) in spring 2020. (Total employment at hospitals in California remained 2 percent lower in February 2021 compared to February 2020.) Furthermore, total employment at California skilled nursing facilities continued to decline until summer 2020, and has not recovered since. (Total statewide employment at skilled nursing facilities was 13 percent lower in February 2021 relative to February 2020.)

Utilization of Health Care

In this section, we summarize trends in the utilization of services, a common measure of the extent to which access to care is realized over time The data source is quarterly reporting by the state’s 44 major health plans to DMHC. Health plans report member utilization for three different categories of services: (1) physician encounters, (2) nonphysician encounters, and (3) hospital inpatient stays.

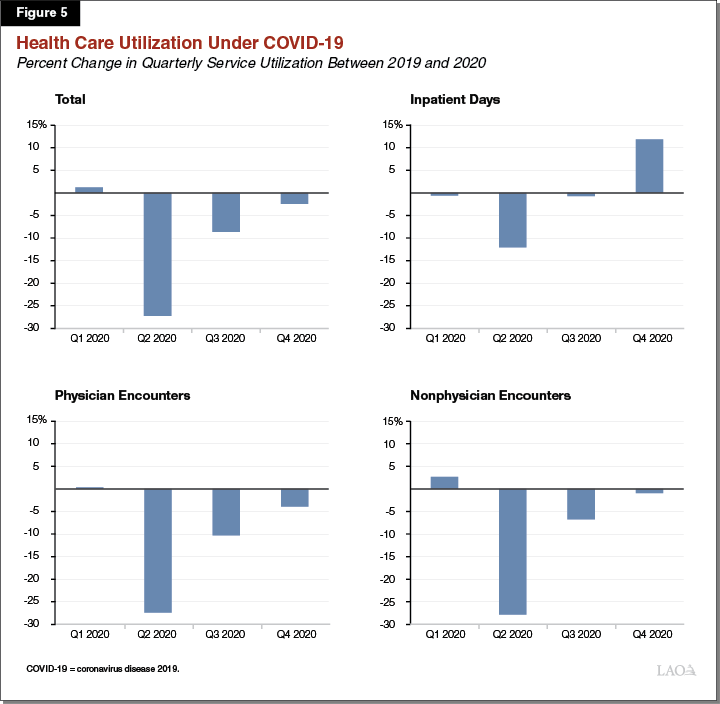

Health Care Utilization Plunged After Onset of COVID-19, but Largely Has Recovered. As Figure 5 shows, quarterly utilization of health care services among health plan enrollees declined precipitously with the start of the pandemic. This decline was most acute in the second quarter (April 2020 through June 2020), when total health care service utilization fell by around 27 percent compared to the same quarter of 2019. Subsequent quarters saw a gradual recovery in service utilization. In the third quarter (July 2020 through September 2020), total health care utilization was around 9 percent lower than the same period of 2019. By the fourth quarter (October 2020 through December 2020), total service utilization was only about 3 percent lower than in the fourth quarter of 2019.

Nonhospital Provider Encounters Experienced the Most Acute Declines, With Hospital Stays Being Largely Unchanged. During COVID-19, physician and nonphysician encounters dropped to a much greater extent than hospital inpatient stays. While the number of hospital inpatient bed days was roughly unchanged between 2020 and 2019 (on net), physician and nonphysician encounters were down by around 10 percent year over year. As Figure 5 shows, physician and nonphysician encounters have gradually, but not fully, returned to 2019 levels by the last quarter of 2020. Hospital inpatient days, on the other hand, fell dramatically in the second quarter of 2020 (the first quarter in which COVID-19 was in effect), then largely returned to pre-pandemic levels by the third quarter of 2020. Finally, hospital inpatient days rose to far surpass 2019 levels in the fourth quarter of 2020. This late-year surge in hospital inpatient days may have been driven by COVID-19-related hospitalizations.

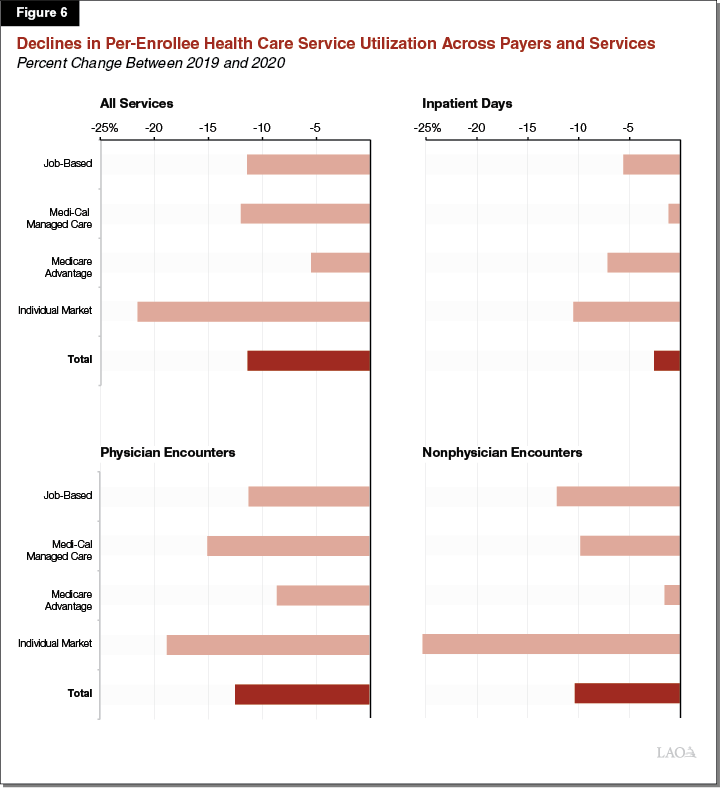

Reductions in Service Utilization Have Been Greatest Among Individual Market Enrollees and Least Among Medicare Advantage Enrollees. Reductions in service utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic have varied by the type of coverage Californians have and by the type of service. Figure 6 shows how these trends have varied. For all services, per-enrollee service utilization has declined the most among residents who have health care coverage through the individual market, while utilization has declined the least for Medicare Advantage plan members. Overall, per-enrollee service utilization among Medi-Cal managed care members declined by about the same percentage as health plan enrollees as a whole. However, the decline in inpatient stays among Medi-Cal managed care plan members was significantly lower than health plan enrollees overall, which could be due to a potentially greater prevalence of COVID-19 hospitalizations among Medi-Cal managed care enrollees. Physician encounters declined to a greater extent among Medi-Cal managed care enrollees than for health plan enrollees as a whole. This potentially could indicate access challenges among Medi-Cal enrollees, whose numbers have grown under the pandemic. As the textbox below describes, other data sources indicate that utilization of children’s preventive services in Medi-Cal have declined significantly during COVID-19. Left unaddressed, this decline could result in negative long-term health consequences for affected children.

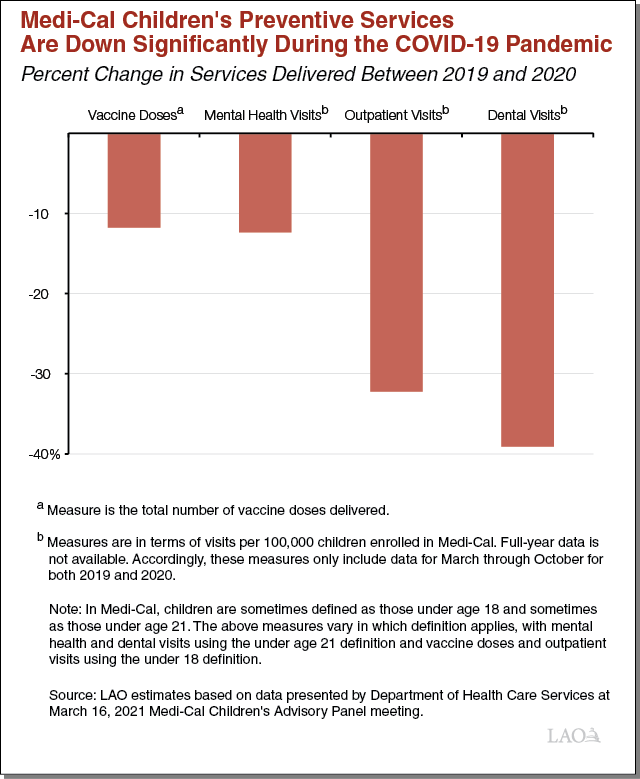

Medi-Cal Children’s Preventive Services Have Declined Significantly During COVID-19

About half of children living California are on Medi-Cal—with a significant majority enrolled in Medi-Cal managed care. Medi-Cal is responsible for ensuring access to preventive health care services for children, including, for example, general checkups known as well-child visits, developmental screenings, vaccinations against infectious diseases, mental health services, and dental care. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has significantly disrupted children’s preventive services in Medi-Cal. As the figure in this box shows, utilization of children’s preventive services is down significantly in 2020 relative to 2019 for a range of Medi-Cal services. Children’s vaccinations and mental health services are down by over 10 percent, while outpatient visits (which include well-child visits, where vaccinations and developmental screenings often take place) and dental visits are down by 30 percent to 40 percent. These disruptions could have negative long-term health consequences for affected children. At least certain of these foregone services—perhaps most notably, childhood vaccinations—would need to be made up to prevent negative long-term health consequences.

Self-Reported Foregone and/or Delayed Care

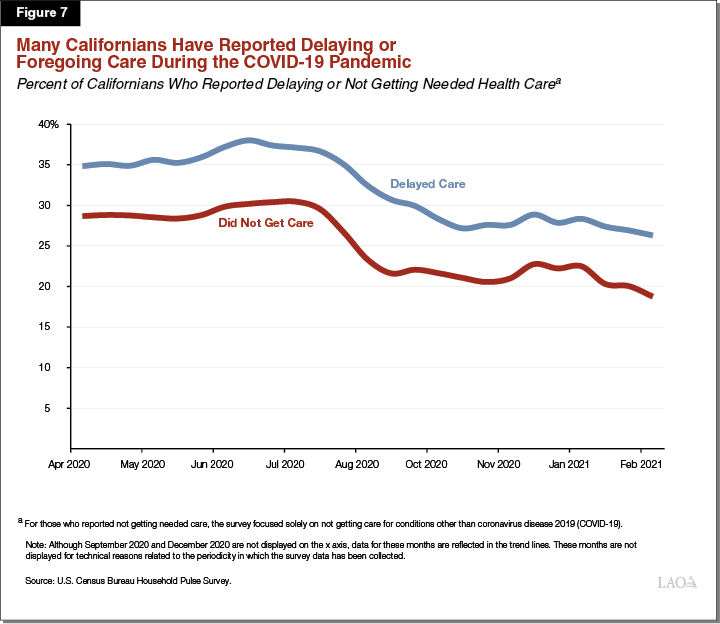

Figure 7 displays the monthly Household Pulse survey data on foregone and/or delayed care during the COVID-19 pandemic. From April 2020 through July 2020, more than one-third of survey respondents reported that they delayed getting medical care due to the COVID-19 pandemic (blue line). In addition, during the same time period, approximately 30 percent of survey respondents reported that they needed medical care for conditions other than COVID-19 but did not receive it (red line). While comparable data from survey respondents on delaying or not receiving medical care prior to the COVID-19 pandemic is not available, this survey data suggests that the pandemic has discouraged a significant number of Californians from utilizing health care services. The proportion of Household Pulse survey respondents who reported that they delayed getting medical care or did not receive medical care declined in August 2020—to just under one-third and slightly more than one-fifth, respectively. In more recent months, data from this survey show sustained declines in foregone or delayed care, although challenges in access to medical care likely remain given that the COVID-19 pandemic is still ongoing. While some Californians who reported delaying or foregoing care during the pandemic likely did so as a result of there not being health care appointments available, some of this delayed/foregone care likely is the result of lower willingness to visit a health care facility given COVID-19 risks. (As mentioned previously, the Household Pulse survey data do not include detailed reasons given for delaying or foregoing care.) Californians’ potentially lower willingness to visit a health care facility may be contributing to the sustained reduction in health care employment reported earlier in this section.

Key Takeaways

Health Care Coverage Has Not Declined as Anticipated. Having health care coverage facilitates accessing care. Because health care coverage is so often job-based in California, the job losses accrued under the pandemic were anticipated to result in major losses in coverage. However, the two available data sources we reviewed do not indicate overall losses in coverage. To the contrary, health care coverage has remained steady or potentially modestly has increased on net under the pandemic. Safety net coverage through Medi-Cal, as well as the individual market (where subsidized insurance is available), likely has contributed significantly to the sustained levels of health care coverage.

While Access to Care Is Trending Toward Pre-Pandemic Levels, Continued Monitoring of Trends Is Warranted. While rates of health care coverage have not been impaired in a sustained way during the pandemic, access to health care does not simply depend on whether someone has coverage. Health care access has been at least temporarily hurt by the pandemic: health care employment fell, service utilization declined, and significant portions of Californians have reported delaying or foregoing care. Nevertheless, data on each of the above metrics generally show that access to health care is trending toward pre-pandemic levels. However, there remain certain areas that warrant continued monitoring to ensure access does not suffer in the long term as the state reopens. First, physician service utilization remains low compared to prior to the pandemic. This trend is especially true for Californians with Medi-Cal managed care and individual market coverage. Second, employment levels have either (1) not recovered or (2) continue to decline for certain health care service types (such as skilled nursing facilities). Third, many Californians have continued to delay or forego health care under the pandemic.

Issues for Consideration

Major Outstanding Questions Remain. This post represents a preliminary look at how COVID-19 has affected access to health care. As the following bullets outline, many questions remain outstanding.

Why Have Health Care Coverage Losses Been Less Than Anticipated? At the onset of the pandemic, state policymakers anticipated that the unprecedented job losses would translate into millions of Californians losing job-based and individual market coverage, and instead would either join Medi-Cal or lose coverage entirely. These predictions have proven significantly overstated for reasons that are not entirely clear. Data on job loss patterns, however, provide some insight. While there were 1.5 million net job losses as of December 2020, the net decline in job-based health care coverage was closer to 300,000. The low share of workers and their families losing job-based coverage likely is, in part, due to the fact that job losses have been concentrated in industries where job-based coverage is less common, such as in the restaurant, hospitality, and entertainment sectors. This theory likely partially explains why job-based coverage losses have translated into relatively limited new enrollment into publicly financed health care coverage through Medi-Cal and the individual market. Workers in the most affected sectors are disproportionately likely to have Medi-Cal or individual market coverage already, or be uninsured. Nevertheless, further analysis would be needed to fully answer this important outstanding question.

How Is Lower Health Care Employment Continuing to Affect Access? As discussed earlier, health care employment experienced a sharp decline in the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic. This substantial decrease in the available supply of health care services likely had an adverse impact on access to health care statewide. In general, health care employment has experienced a partial recovery toward pre-pandemic levels, but the recovery has stagnated over recent months. In addition, certain health care service types have experienced no employment recovery or are still experiencing employment declines. Accordingly, challenges in accessing health care may be persistent due to the incomplete recovery of employment in health care.

Is There Significant Pent-Up Demand for Health Care Services? As previously shown in Figure 7, throughout the pandemic, the share of Californians reporting delaying or foregoing health care has remained above 20 percent, and in some months has approached 40 percent. How this delayed and foregone care has affected Californians’ health is not well understood. (Particularly worrisome are sharp declines in childhood vaccination rates for diseases other than COVID-19.) Moreover, as the pandemic dissipates, pent-up demand for services to treat conditions that went untreated throughout the pandemic could cause a spike in health care utilization. To what extent we will see such a spike in utilization is unclear.

How Have Health Plans Modified Their Provider Networks in Light of Coverage Changes? While coverage losses do not appear to have occurred on net during the pandemic, there have been shifts in coverage—most notably, losses in job-based coverage and increases in Medi-Cal coverage. Data from health plans reveal that physician-service utilization has remained more depressed under the pandemic for Medi-Cal managed care members than for Californians with other types of coverage. (Californians with individual market coverage appear to be utilizing all service types at disproportionately low rates under the pandemic compared to other health plan members.) There likely are multiple reasons why COVID-19 is having different impacts on utilization for Californians with different types of coverage. Nevertheless, the sustained reduction in physician-service utilization for Medi-Cal managed care members raises the question of how well health plans have been doing in modifying their provider networks to ensure appropriate access for Californians transitioning between coverage types.

Which Types of Providers Might Need Financial Assistance? Relief funding for health care providers is one way to help mitigate the negative employment impacts they have experienced as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (and the negative impacts this may have on access to health care). Although the health care sector experienced a sharp employment decline in the initial months of the COVID-19 pandemic, the degree to which this decline occurred varied substantially by specific health care service type. These health care service types have also varied in how strongly they have recovered their employment losses as the pandemic has gone on. At a high level, our review of employment data provides some insight on how health care providers have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, additional data—particularly related to provider finances—is needed to gain a more comprehensive understanding of which health care provider types are in most need of relief.

Policy Options for Sustaining and Improving Access to Health Care. The Legislature could consider ways to sustain and improve access to health care during and after the pandemic. Various policy options come with different near- and long-term costs, while also generating different levels of benefit. We primarily suggest limited-term funding opportunities and other policy changes that do not come with ongoing costs. Federal fiscal relief funds may be one possible source to fund these activities.

Fund Health Care Coverage Enrollment Outreach. As the pandemic subsides, shifts in which types of coverage are available to state residents are likely. Once federal Medicaid rules effectively allow Medi-Cal eligibility terminations to resume after the end of the national COVID-19 public health emergency and as the state’s labor market improves, fewer Californians will be eligible for Medi-Cal. Many individuals and families transitioning off Medi-Cal may be eligible for recently enhanced financial assistance from the federal government for individual market coverage. The Legislature could consider funding outreach campaigns to inform Californians of their health care coverage and financial assistance options.

Address the Deficit in Children’s Preventive Services. As described in the box above, children’s preventive services in Medi-Cal—including vaccination rates for diseases other than COVID-19—have plunged during the pandemic. If left unaddressed, these declines in services potentially could significantly increase the prevalence of preventable diseases in the future. The Legislature could consider funding statewide efforts or adopting other policy changes to address the deficit in children’s preventive services during COVID-19. Potential policy options include funding outreach efforts; temporarily increasing reimbursement levels for children’s Medi-Cal services; and improving the accessibility of children’s Medi-Cal services, for example, by carrying out vaccinations and potentially other preventive services out in the community.

Efforts to Improve Timeliness of Data Collection and Reporting on Access to Health Care. This post pieces together various data sources to sketch a high-level picture of how COVID-19 has affected access to health care in California. However, this picture is far from complete. The data we have relied upon generally are highly aggregated, not allowing for a detailed analysis of how trends have differed geographically across the state, for different population groups (such as individuals of different races and ethnicities), or for different kinds of inpatient and outpatient services. Moreover, the data are not always complete. Much of this analysis relied upon reports from the state’s 44 major health plans, which show the experience of a significant portion (70 percent) of, but not all, Californians in terms of access to care. Data from various sources that more comprehensively will show how COVID-19 has affected access to care ultimately will become available. However, these data will trickle out slowly and often after the pandemic has dissipated. These lags in the state’s health care data collection and release processes impede state policymakers’ ability to understand and respond to evolving crises and challenges. For example, we continue to lack information on which health care providers have faced the greatest financial challenges under the pandemic and, accordingly, where provider financial relief from the state could go the farthest in maintaining access to care. The Legislature might consider exploratory efforts on how to improve data collection and publication processes to allow more timely and nimble responses to evolving challenges related to health care access.