LAO Contact

May 13, 2021

A Review of Child Care and Preschool Program Flexibilities in Certain Counties

In this post, we provide background on child care and preschool program flexibilities that have been granted in state law to certain counties. We then assess these flexibilities and provide issues for the Legislature to consider in deciding whether to maintain the flexibilities.

Background

State Law and Regulations Govern State Subsidized Child Care and Preschool Programs. The state subsidizes child care and preschool programs for an estimated 437,000 children. The state determines many programmatic aspects, such as who is eligible for the programs and how much providers receive for reimbursement. For example, state law specifies that, to be eligible for subsidized child care, children must be under the age of 13 and from a family with an income at or below 85 percent of the state median income ($73,885 for a family of three). State subsidized slots are limited and not all those eligible receive care. The American Institutes for Research estimates 483,000 eligible infants and toddlers are not receiving subsidized child care.

State Funds Child Care Providers Using Two Different Rates. The state funds subsidized child care programs through either vouchers or direct contracts (see Figure 1). For providers that care for children in a voucher-based program, the state provides a maximum reimbursement rate that varies based on the county where the child is served. (If a provider charges less than the maximum amount, the state reimburses the actual charge.) These reimbursement rates are referred to as the Regional Market Rate (RMR) and are based on a survey of licensed child care providers. In addition to variation by county, the maximum reimbursement a provider receives also varies by age of child, length of care, and setting of care. The state also contracts directly with providers to serve a specified number of eligible children. These providers, referred to as direct contract providers, receive the Standard Reimbursement Rate (SRR) which is set annually in the state budget. The SRR is adjusted by length of care and age of child. Providers also receive a higher SRR for serving students with limited English proficiency and students with disabilities. Unlike the RMR, the SRR does not vary based on the geographic location the child is served.

Figure 1

State Funds Child Care Programs Through Vouchers and Direct Contracts

|

Program |

Payment Type |

Reimbursement Rate |

|

CalWORKs Child Care |

Voucher |

RMR |

|

Alternative Payment |

Voucher |

RMR |

|

General Child Care |

Direct Contract |

SRR |

|

State Preschool |

Direct Contract |

SRR |

|

Care for Children With Severe Disabilities |

Direct Contract |

SRR |

|

Migrant Child Care |

Voucher and Direct Contract |

RMR and SRR |

|

RMR = regional market rate and SRR = standard reimbursement rate. |

||

Funds for Direct Contract Providers Initially Awarded Competitively, Then Annually Renewed. Expansion funds for direct contracts are awarded to eligible and qualified providers through a competitive application process. The California Department of Education (CDE) prioritizes awards to providers based on geographic unmet need. If the direct contract provider remains in good standing, its contract is renewed annually. Many providers have held a direct contract with the state for decades.

If a Provider Does Not Earn Its Full Contract, Funds Are Returned to the State. In some cases, a provider may serve less children than it intended to serve and not fully earn its contract. These unused funds result in one-time savings for the state. If a provider has a history of unused funds over several years, CDE could permanently reduce the provider’s contract. In recent years, CDE made funds from contract reductions available for other providers statewide to serve additional children.

In 2003 and 2005, the Legislature Authorized San Mateo and San Francisco Counties, Respectively, to Receive Flexibility From Certain State Laws. The Legislature enacted Chapter 691 of 2003 (AB 1326, Simitian) and Chapter 725 of 2005 (SB 401, Migden), which provided direct contract child care and preschool providers in San Mateo and San Francisco Counties flexibility from certain state laws. The goal of the flexibilities was to help providers located in these counties use all awarded funds and not return funds to the state. In particular, San Francisco and San Mateo Counties expressed concern that using the state median income to determine eligibility made it difficult for families in these counties—which have higher wages and a higher cost of living—to qualify for subsidized care. Chapters 691 and 725 allow CDE to grant on a pilot basis certain flexibilities after reviewing plans submitted by these counties. As a result of this authority, the two counties implemented a number policies that provide flexibility on administrative practices, eligibility, and per-child rates. While the pilots initially had a sunset date, the Legislature extended and subsequently removed the sunset provisions—permanently allowing these counties to receive flexibilities from state law. As “permanent pilot” counties, San Mateo and San Francisco must submit a report to the Legislature, CDE, and the Department of Social Services (DSS) once every three years.

Counties With Flexibilities Has Grown to 13. From 2015 through 2017, the state authorized 11 “temporary pilot” counties, which received similar authority to San Mateo and San Francisco Counties. The temporary authority of these counties expires July 1, 2021 for Alameda County, July 1, 2022 for Santa Clara County, and July 1, 2023 for the nine remaining counties. The temporary pilot counties are required to submit a report to the state. The reporting requirements are specified in statute and vary by county, but are only required if a county has an approved pilot plan. Two counties, Monterey and San Benito, do not have approved pilot plans.

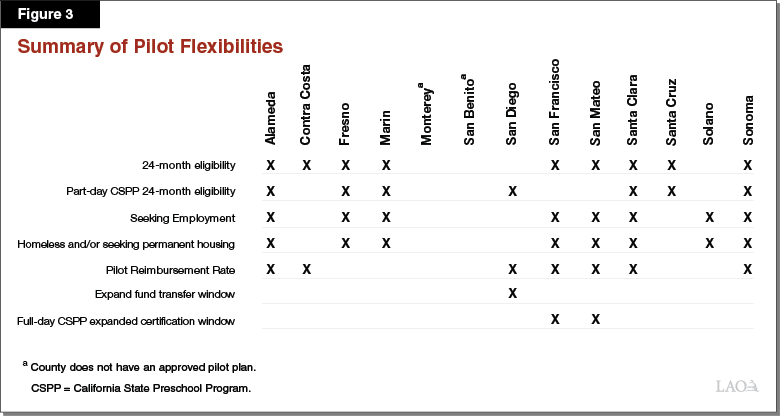

Each Pilot County Has a Unique Set of Flexibilities. Although legislation authorizes flexibility in a number of areas, the specific flexibilities that exist in each county are determined locally, subject to approval from CDE. Figure 2 describes the current flexibilities in more detail and in comparison to statewide policies. (As we discuss later, some flexibilities implemented by counties have since become statewide polices. Figure 2 excludes these policies.) Typically, local planning councils (LPCs) coordinate communication between providers in the county to decide on a set of flexibilities to request. (Each county has an LPC which provides a forum to identify priorities for child care programs within the county.) Once the providers that choose to participate in the county pilot agree on a set of flexibilities to request, the LPC prepares and submits an application to CDE. CDE then reviews and either approves or disapproves the applications. During its review, CDE ensures that the request meets the requirements specified in statute and is justified with data. As a result of these county-specific processes, the flexibilities in each of the pilot counties vary. Figure 3 displays the flexibilities requested by counties and approved by CDE.

Figure 2

Current Pilot Flexibilities Compared to State Law

2020‑21

|

Flexibility Type |

Statewide Policy |

Policy for Select Pilot Counties |

|

Eligibility |

|

|

|

Reimbursement Rate |

|

|

|

Administration |

|

|

|

CSPP = California State Preschool Program. |

||

Seven Counties Receive a Higher Reimbursement Rate From Unused Contract Funds. Pilot counties have the flexibility to give their providers a higher reimbursement rate, commonly referred to as a Pilot Reimbursement Rate (PRR). For counties that choose to take this approach, the higher rate is determined by the amount of unused funds available from providers within the county. This effectively allows the county to serve the same number of children at a higher reimbursement rate, with the state forgoing one-time savings. For a provider to receive the PRR, it must opt in to having its unused contract funds in this way. Figure 4 shows the 2020‑21 rates of the seven pilot counties using this flexibility. The PRRs range from 2 percent to 7 percent higher than a provider operating the same services and receiving the SRR.

Figure 4

Pilot Reimbursement Rates

2020-21 Daily Rate

|

State |

General |

|

|

Statewide |

$49.85 |

$49.54 |

|

Alameda |

53.41 |

52.78 |

|

Contra Costa |

50.67 |

— |

|

San Diego |

50.70 |

— |

|

San Francisco |

53.02 |

52.67 |

|

San Mateo |

53.69 |

53.37 |

|

Santa Clara |

53.74 |

52.52 |

|

Sonoma |

50.60 |

— |

Administration of Pilots to Change Due to Planned Child Care Transition. The 2020‑21 budget shifted administration of state child care programs and initiatives from CDE to DSS beginning July 1, 2021. Under the transition, CDE will continue to administer State Preschool, the largest direct contract program, while the General Child Care program will be administered by DSS. As a result of the planned transition of child care programs, DSS will have a more active role moving forward in the administration of pilots. Since many of the pilot flexibilities are applicable to both General Child Care and State Preschool, we anticipate DSS and CDE will need to have increased coordination to implement and oversee the pilot plans.

Assessment

Some Flexibilities Implemented by Pilot Counties Later Became State Law, Reducing the Need for Pilots. In recent years, the Legislature has changed state law to make certain pilot county flexibilities apply statewide. For example, pilot counties were allowed to serve children from families with income at or below 85 percent of state median income (the highest income allowable for federally funded programs), compared to 70 percent of state median income in the rest of the state. In 2019‑20, the Legislature increased the income eligibility threshold to 85 percent of the state median income for all counties. Authorizing pilot counties to implement new policies at a smaller scale allows the state to determine whether the policy is effective and provide guidance for better statewide implementation. Over time, however, the changes to state law have reduced the need for pilot flexibilities in participating counties.

Implementing Flexibilities Is Administratively Complex for State and Local Entities. The process of submitting and reviewing the county plan is a burdensome process for counties and the state. First, LPCs must submit a plan which requests specific flexibilities to CDE. The plan must specify which providers in the county agreed to participate in the pilot and want these flexibilities. Next, CDE reviews the plan and must approve or disapprove within 30 days. At this stage, CDE may request additional data to validate the county’s rationale for wanting specific flexibilities. Based on our conversations with CDE and LPCs, counties often must submit multiple iterations of their plan before CDE determines it has the appropriate data to approve the plan. After the county implements the flexibilities in the approved plan, counties have to provide a report to the state. Implementing the flexibilities also can be administratively complex for providers. For example, a provider that operates in two counties with different eligibility criteria must ensure it is in compliance with both sets of rules (the statewide eligibility for the non-pilot county and the pilot eligibility for the pilot county). A provider operating in multiple non-pilot counties would only need to comply with statewide eligibility.

Flexibilities Make It More Difficult for State to Respond to Statewide Need. Pilot flexibilities make it easier for providers in these counties to fully earn their contracts. When this occurs, a provider typically has the option to renew its contract at the same level in the following year. If a provider does not fully earn its contract for a few years, CDE makes those funds available to another provider. Being unable to earn your contract on an ongoing basis typically means there are not enough eligible families interested in receiving child care or preschool services from the provider. While the number of families eligible for child care and preschool slots greatly exceeds the number of subsidized slots available statewide, there could be other reasons for low demand in services for specific providers. For example, the operating hours may not meet the needs of families, or the number of income-eligible families in the local area could have decreased due to demographic changes. Providing flexibilities so certain providers can fully earn their contracts removes the state’s ability to reallocate funds to areas with the greatest unmet need. While CDE in recent years has attempted to redistribute slots from areas with lower demand to areas with the highest level of unmet need, funding within pilot counties has largely been excluded from these efforts.

County-Specific Rates Not Tied to Cost of Care. One rationale for allowing pilots to provide higher reimbursement rates is because of regional variation in costs. Based on our review of the SRR and RMR in these counties, we think there is some merit to higher reimbursement rates based on geographic variation in costs. However, existing PRRs are based on the amount of funds providers were unable to use, which does not necessarily align with the higher cost of care in the county. Moreover, the PRRs do not target rate increases to specific age groups that might have the lowest rates relative to the RMR. (The RMR captures cost variation based on both region and a child’s age using a survey of licensed child care providers.) For example, for preschool-aged children, the RMR is higher than the SRR or PRR in every county. For infants, the SRR is higher than the RMR in every county and the rate for counties using the PRR exceeds both the SRR and the RMR.

Flexibility on State Preschool Eligibility Reduces Administrative Burden and Supports Continuity of Care. Rather than requiring eligibility to be determined once per year, the pilot flexibilities grant three-year olds enrolled in direct contract programs with 24 months of eligibility. This allows children to stay eligible for both years of the preschool program, further promoting kindergarten readiness. The policy also reduces administrative burden without adding cost pressure, as three-year olds enrolled in State Preschool are very likely to continue to be eligible as four-year olds. Generally, income eligible four-year olds receive priority enrollment in State Preschool. Three-year olds that are prioritized ahead of income eligible four-year olds are either recipients of child protective services or at risk of being neglected, abused, or exploited and referred by a legal, medical, or social service agency.

Issues for Consideration

Apply Some Pilot Flexibilities Statewide. The Legislature could consider allowing some of the pilot flexibilities statewide. For example, we recommend the Legislature provide 24 months of State Preschool eligibility statewide. This change would allow three-year olds enrolled in State Preschool to continue participating in the program until they are eligible for kindergarten. This helps to ensure the kindergarten readiness benefits a child receives from preschool as a three-year old do not diminish prior to kindergarten enrollment. Moreover, the change would reduce some administrative burden without adding cost pressure to the program. (If the Legislature were to make other significant changes to its preschool programs, such as expanding Transitional Kindergarten, it would want to consider if 24-month eligibility in State Preschool continues to align with the intent of the program..

Allow Temporary Pilots to Keep Existing Flexibilities, but Remove the Ability to Add More Flexibilities. To avoid creating further inequities in the state’s system, the Legislature could consider codifying existing flexibilities for temporary pilot counties, but not allow counties to modify or add to these flexibilities in the future. Limiting future flexibilities would simplify administrative workload moving forward and eliminate the need for oversight from DSS and CDE. By allowing existing flexibilities to continue, counties would avoid disruptions to services for existing families and could continue to provide the existing PRR—which providers have now come to rely on to meet their operating costs. Under this approach, any rate or eligibility changes moving forward would be a result of changes in statewide policy.

The Legislature Could Decide to Modify Permanent Pilots. Given the above issues created by granting some pilot flexibilities, the Legislature may want to reconsider the flexibilities granted to permanent pilots. To the extent the Legislature decides to modify permanent pilots, it could require that these counties, as a condition of being granted program flexibilities, implement policies of state interest. This would allow the state to test new policies at a small scale before implementing the changes statewide. For example, the state could implement a different family fee schedule in pilot counties a year prior to making the new family fee schedule statewide policy. This approach could help estimate statewide costs of certain policies and give DSS and CDE a sense of what statewide guidance providers may need for a more seamless implementation. Furthermore, as the Legislature considers comprehensive changes to child care and preschool funding, it may also want to remove the ability for permanent pilots to further augment reimbursement rates. Comprehensive rate reform would likely address regional variation in costs that initially led to the implementation of the rate flexibilities.

In Making Changes to the System, Use Data-Driven Approach to Establishing County Variation. For most program rules, such as state oversight and eligibility requirements, we think having a uniform policy across the state allows for consistency and equity in implementing child care and preschool programs. For some issues, such as reimbursement rates, there may be a strong policy rationale for variation based on geography. To the extent the Legislature is interested in allowing for regional variation, we recommend the variation be based on specific data driven criteria that are used to consider variation for all counties—not only those that have been granted flexibility.