LAO Contact

May 26, 2021

Repaying the State’s Federal Unemployment Insurance Loan

The Governor’s 2021‑22 May Revision budget proposes $36 million General Fund to pay the first, partial payment on the state’s outstanding federal Unemployment Insurance (UI) loan and proposes to direct $1.1 billion in federal American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act funds to pay down a portion of the outstanding loan. In this post, we (1) provide an overview of the state’s UI system financing, (2) highlight how the pandemic affected the UI system, (3) look ahead to upcoming costs to employers and the state to repay the federal UI loan, and (4) assess the Governor’s proposed $1.1 billion pre-payment.

Overview

UI Program Assists Unemployed Workers. Overseen by the Employment Development Department (EDD), the UI program provides weekly benefits to workers who have lost their jobs through no fault of their own. The federal government oversees state UI programs but the state has significant discretion to set benefit and employer contribution levels. Under current state law, weekly UI benefit amounts are intended to replace up to 50 percent of a worker’s prior earnings, up to a maximum of $450 per week, for up to 26 weeks. In 2019, the average benefit amount was $330 per week.

UI Program Is Financed With Payroll Taxes Paid by Employers. Employers pay both state and federal UI payroll taxes. State UI tax revenues are deposited into the state’s UI trust fund to pay benefits to unemployed workers. State UI tax rates are set based on rate schedules laid out in state law. The schedules require higher rates, up to a maximum of 6.2 percent, when the condition of the UI trust fund is poor—meaning that it has a low level of reserves. Due to longstanding solvency issues, the state’s UI tax rate has been at this maximum amount since 2004. The federal UI tax typically is used to pay for state UI program administration costs and is set at a rate of 0.6 percent. Both state and federal UI payroll taxes are applied to each employee’s first $7,000 in annual wages.

States May Borrow From Federal Government During Economic Downturns. During recessions, the state’s UI trust fund can become insolvent as the cost of benefits exceeds employer tax contributions and trust fund reserves are exhausted. Federal law allows states, when they exhaust their state UI trust funds, to receive loans from the federal government to continue paying benefits. These loans must be repaid, with interest (currently 2.3 percent annually), at a later time. The loan principal is repaid by automatic increases in the federal UI tax rate that are set out in federal law. The loan interest typically has been paid from states’ General Funds.

Under Federal Repayment Plan, Businesses Repay Federal UI Loans Over Time. Under federal law, for states with federal UI loans outstanding, the federal UI tax rate on employers increases by 0.3 percentage points. The additional revenues generated from the tax increase go to paying down the state’s federal loan. The federal UI tax rate continues to increase by increments of 0.3 percentage points each year until the loans are fully repaid, at which point the federal tax returns to its usual rate of 0.6 percent. In effect, these federally required tax increases make it so that employers pay for UI benefit costs that were covered by federal loans when the state UI trust fund exhausted its reserves.

State’s UI System During the Pandemic

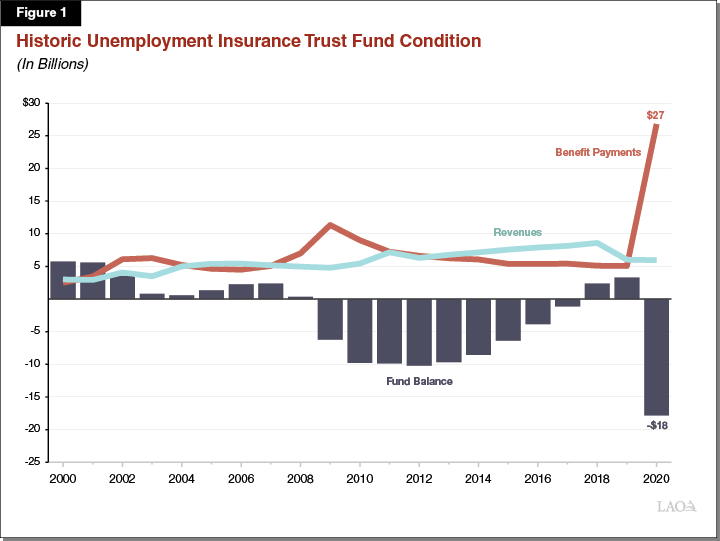

State’s UI Trust Fund Became Insolvent Shortly After Pandemic Began. Prior to the pandemic, at the start of 2020, the state’s UI trust fund held $3.3 billion in reserves. Despite these reserves, the state’s UI trust fund became insolvent during the summer of 2020, a few months following the start of the pandemic and associated job losses. (As described above, federal law provides states automatic federal loans to continue paying state benefits should a state’s UI trust fund become insolvent.) As shown in Figure 1, by the end of 2020, the state’s UI trust fund had a negative $18 billion fund balance.

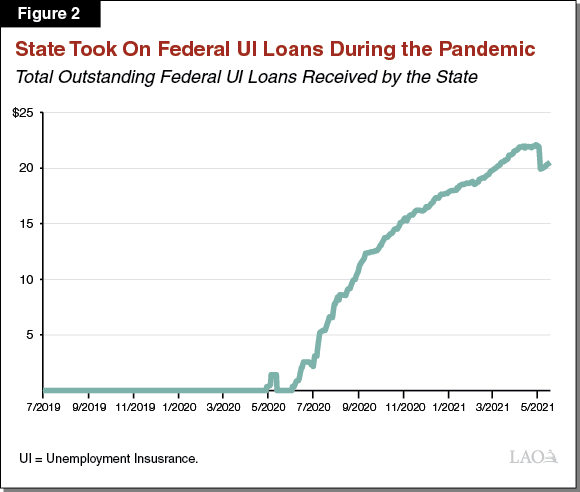

Since Pandemic Began, State Has Received $20 Billion in Federal UI Loans. California, like many other states, has used federal loans to continue paying benefits during the pandemic. As shown in Figure 2, the state first received federal UI loans to cover state UI benefit costs in May 2020. The state’s current outstanding loan balance is roughly $20 billion. (This state debt is only related to paying regular state UI benefits. The state does not need to borrow to pay for the temporary benefit increases and extensions that the federal government enacted during the pandemic because these benefits are 100 percent federally funded.) California also received federal loans during the Great Recession. At that time, the state’s peak year-end balance of loans was $10.2 billion at the end of 2012. Between 2011 and 2018, the state General Fund paid a total of $1.4 billion in interest payments on these loans.

Many Other States Also Received Federal UI Loans. In addition to California, 17 other states have received federal UI loans to continue paying state benefits. Figure 3 shows the amount borrowed to date by each state; and, in order to compare across states, the amount borrowed per worker in the state. California’s amount borrowed per worker—$1,070—is higher than in other states due to a combination of relatively generous state UI benefits and the state’s above-average unemployment rate throughout the pandemic.

Figure 3

Comparing States That Have Received Federal Unemployment Insurance Loans

As of May 19, 2021

|

State |

Federal |

Share of |

Loan Amount |

|

California |

$20,501,188,129 |

40% |

$1,070 |

|

New York |

9,286,282,325 |

18 |

979 |

|

Texas |

6,915,964,929 |

13 |

494 |

|

Illinois |

4,232,873,402 |

8 |

667 |

|

Massachusetts |

2,268,015,460 |

4 |

608 |

|

Pennsylvania |

1,559,422,237 |

3 |

239 |

|

Ohio |

1,471,812,516 |

3 |

252 |

|

Minnesota |

1,049,257,297 |

2 |

336 |

|

Colorado |

1,014,167,919 |

2 |

327 |

|

Connecticut |

725,077,559 |

1 |

379 |

|

Hawaii |

691,766,990 |

1 |

1,031 |

|

Kentucky |

505,732,622 |

1 |

244 |

|

Nevada |

332,407,747 |

1 |

209 |

|

New Jersey |

298,413,642 |

1 |

65 |

|

New Mexico |

278,163,849 |

1 |

289 |

|

West Virginia |

184,910,036 |

— |

229 |

|

Louisiana |

184,145,942 |

— |

86 |

|

Maryland |

68,528,256 |

— |

21 |

|

Totals |

$51,568,130,856 |

— |

$577 |

Looking Ahead

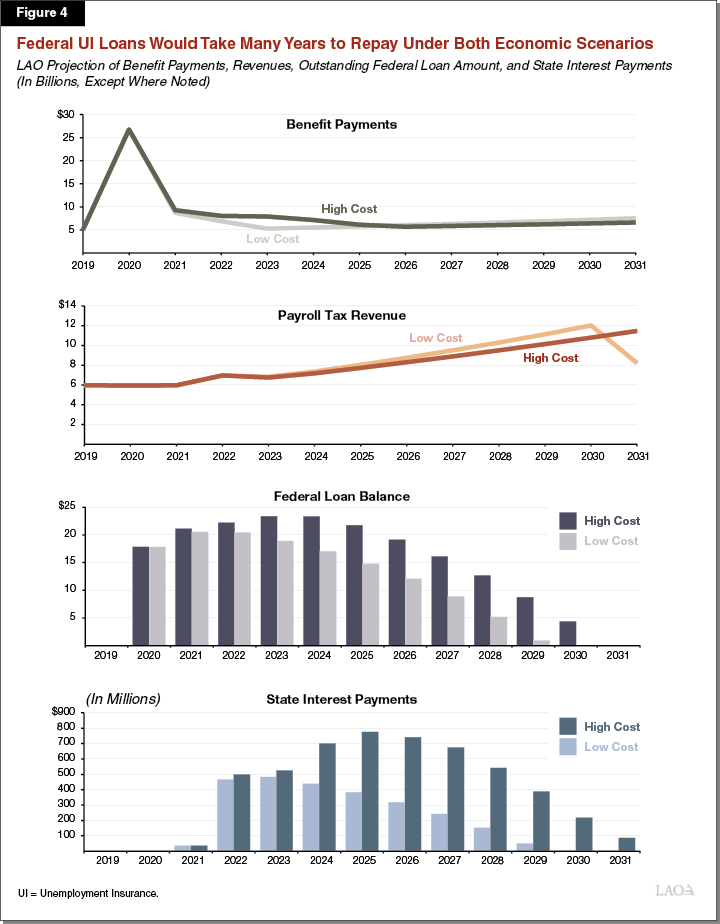

State and Employer Costs Under Two Economic Scenarios—Low Cost and High Cost. To illustrate state and employer costs to repay the federal UI loans, our office produced a low-cost and a high-cost forecast of the state’s UI system based on different underlying economic scenarios. Under the low-cost scenario, employment quickly returns to pre-pandemic levels and interest rates remain historically low for the entire period. In this scenario, the state’s unemployment rate settles at a low 4.5 percent and the federal interest rates on UI loans averages 2.5 percent for the repayment period. Under the high-cost scenario, the state’s economic recovery is delayed several years, with unemployment remaining above 6 percent until 2025, and interest rates paid on the UI loans increase gradually to 4.5 percent after the recovery has taken hold.

Under Both Scenarios, Federal UI Loans Would Take Many Years to Repay. Under the low-cost scenario, we project that the state and employers will repay the federal UI loans in 2030. Under the high-cost scenario, the state and employers would repay the federal loans one year later, in 2031. Figure 4 displays the key components of these projections, including annual benefit payments, payroll tax revenue, and the federal loan balance.

State’s First Partial Interest Payment on Federal UI Loans Due in 2021‑22… Under existing federal law, states must pay interest on their outstanding federal UI loans beginning on September 30 of the first calendar year during which the state had outstanding loans. (The current interest rate on the federal UI loans is historically low at just 2.3 percent.) However, several pieces of federal pandemic legislation waived accrual of interest from the beginning of the pandemic through September 6, 2021. As a result, the state’s upcoming interest payment—estimated to be $36 million General Fund—corresponds only to interest that will accrue between September 6 and September 30, 2021. Federal action to waive interests accrual during the pandemic likely resulted in the state paying about $350 million less interest than the state would have paid without the waivers.

…But Larger Payments Upcoming in Future Years. Barring additional interest waivers, the state will pay the full annual interest costs in upcoming years. Figure 5 shows our projections for the state’s upcoming interest payments under our two scenarios. Although projecting these interest payments is subject to major uncertainty, our preliminary projections indicate that the state will owe roughly $500 million in 2022‑23 under both scenarios. Under the low-cost scenario, the state would owe slowly decreasing amounts each year thereafter through 2030‑31 (when we expect employers to have repaid the loan principal, as discussed below). In total, under the low-cost scenario, we project the state will pay approximately $2.5 billion in interest over the life of the federal loan. Under the high-cost scenario, the state would make increasingly large interest payments for the next several years before payments decline slowly through 2031‑32, resulting in total state interest costs of $5.2 billion.

Figure 5

Looking Ahead at State Costs to

Repay Federal UI Loan

LAO Projections (In Millions)

|

Fiscal Year |

Estimated State Interest Payment |

|

|

Low‑Cost Scenario |

High‑Cost Scenario |

|

|

2021‑22 |

$36 |

$36 |

|

2022‑23 |

470 |

500 |

|

2023‑24 |

480 |

530 |

|

2024‑25 |

440 |

700 |

|

2025‑26 |

380 |

780 |

|

2026‑27 |

320 |

740 |

|

2027‑28 |

240 |

680 |

|

2028‑29 |

150 |

540 |

|

2029‑30 |

50 |

390 |

|

2030‑31 |

5 |

220 |

|

2031‑32 |

— |

90 |

|

Totals |

$2,500 |

$5,200 |

|

Note: low cost scenario assumes 2.5 percent interest rate, whereas high cost scenario assumes 4.5 percent interest rate. |

||

|

UI = Unemployment Insurance. |

||

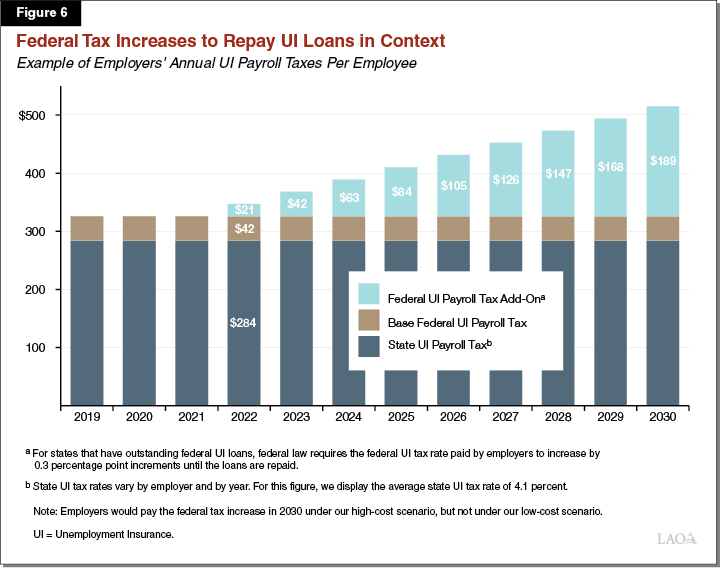

Businesses Set to Pay Add-On Federal UI Tax Beginning in 2023. Under current federal law, the federal UI payroll tax rate on employers will increase by 0.3 percent for tax year 2022. However, employers will not pay this higher rate until 2023 when employers remit their 2022 payroll taxes to EDD. To give some context to the size of increased federal UI taxes that employers will pay to repay the loans, Figure 6 shows a hypothetical employer’s combined state and federal UI tax liability for a single employee for each year the increased federal UI taxes are projected to be in effect. Under the low-cost scenario, we estimate—as shown in figure 7—total employer payroll taxes paid under the federal tax increase of $17 billion. Under the high-cost scenario, total employer payroll taxes paid under the federal tax increase are larger, about $20 billion. Employer costs would be higher under the high-cost scenario because the federal payroll tax increase used to repay the loans would be in effect for one additional year.

Figure 7

Looking Ahead at Employer Costs to

Repay the Federal UI Loans

LAO Projections (In Millions)

|

Calendar Year |

Estimated Add‑On Federal Payroll Taxes |

|

|

Low‑Cost Scenario |

High‑Cost Scenario |

|

|

2023 |

$400 |

$400 |

|

2024 |

800 |

800 |

|

2025 |

1,300 |

1,200 |

|

2026 |

1,800 |

1,700 |

|

2027 |

2,300 |

2,200 |

|

2028 |

2,800 |

2,600 |

|

2029 |

3,400 |

3,200 |

|

2029 |

4,100 |

3,700 |

|

2030 |

— |

4,200 |

|

Totals |

$17,000 |

$20,000 |

Two Scenarios Do Not Account for Potential Recession Before Federal Loans Are Repaid. As discussed above, our two projections assume a continuation of the economic recovery from the pandemic and no upcoming recession. Given how long the state and employers are projected to be repaying the federal loans, there is some probability that the state enters a recession before the loans are repaid. If this were to occur, overall costs for the state and employers would be higher than under either scenario we present here. Because the state’s trust fund is insolvent, any additional benefit payments made during the repayment period would require additional federal loans, thereby increasing state interest costs and future employer payroll taxes.

Governor’s 2021‑22 May Revision Proposal

The Governor’s 2021‑22 May Revision budget proposes $36 million General Fund to pay the first, partial payment on the state’s outstanding federal UI loan. The May Revision also proposes to direct $1.122 billion in federal ARP Act funds to pay down a portion of the outstanding loan. (Technically, the $1.1 billion payment will be made from the state’s Coronavirus State Fiscal Recovery Fund.) The administration also has signaled an intent to deposit unused ARP funds, as of June 30, 2024, to additional federal UI loan payments. The proposed deposit would reduce the state’s outstanding loan balance by about 5 percent.

Assessment

$1.1 Billion Repayment Would Lower State Interest Costs and Employer Costs... The Governor’s May Revision deposit proposal would immediately reduce the amount of outstanding federal UI loans. As a result, the proposal would reduce state interest costs immediately. The state also would face lower interest payments each year the loan remains outstanding. We estimate that the Governor’s proposed $1.1 billion deposit would reduce General Fund interest costs over the repayment period by about $230 million under the low-cost scenario and $370 million under the high-cost scenario.

The proposed deposit also would reduce employer costs in the future. In general, the $1.1 billion deposit would reduce the amount employers must repay by $1.1 billion. However, employers would not benefit from these lower costs for many years. This is because the proposed deposit would have the potential to shorten the number of years that employers pay the increased federal tax rates. Due to how the federal tax increases are calculated, however, employers may see no direct benefit if the $1.1 billion deposit is too small to reduce the repayment schedule by a full year. (In this case, employers would nevertheless pay the higher federal UI tax rates but the carryover revenue would instead be deposited into the state UI trust fund. These funds would be available to pay UI benefits in future years.)

…But Provide No Near-Term Economic Relief to Employers or Workers. Due to how federal law sets out the employer tax repayment structure, the Governor’s proposed $1.1 billion deposit would not benefit employers or their employees until well after the pandemic has ended. As discussed above, under our main projection, the earliest that the $1.1 billion deposit could provide business payroll tax relief would be in 2030.