LAO Contact

Correction 11/19/21: Corrected average annual per person fee-for-service cost in Medi-Cal.

November 9, 2021

Enhancing Federal Financial Participation for Consumers Served by the Department of Developmental Services

Summary

The Supplemental Report of the 2020‑21 Budget Act requires our office to evaluate Medi‑Cal enrollment processes among consumers of the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) and provide options to increase enrollment with the goal of increasing federal funding for regional center (RC)‑coordinated services.

Potential Additional Medi‑Cal Enrollment of DDS Consumers Is Fairly Limited. DDS can draw down federal funding for many of the services it provides to DDS consumers if the consumer is enrolled in Medi‑Cal, has legal immigration status, lives in a community‑based setting, and receives at least one RC‑coordinated service. Currently, eight in ten out of about 320,000 total DDS consumers already are enrolled in Medi‑Cal. Among adults, we find little potential for additional Medi‑Cal enrollments or additional federal funding for DDS services. We find that the potential to draw down additional federal funding in DDS rests largely with children who would qualify for Medi‑Cal through an eligibility pathway referred to as “institutional deeming.” This eligibility pathway—available to certain higher‑needs children—considers only the child’s (not the family’s) income in determining Medi‑Cal income eligibility. We estimate there is the potential to enroll up to 7,000 additional children in Medi‑Cal through this eligibility pathway.

On Net, Increasing Medi‑Cal Enrollment Among DDS Consumers Would Actually Increase State Costs Overall. The state would save about $24 million General Fund in the DDS budget if DDS were able to enroll all 7,000 additional children in Medi‑Cal. However, it would incur Medi‑Cal costs in other departments (for services such as medical and dental care or In‑Home Supportive Services) of about $70 million, for a net state cost of about $46 million General Fund, or $6,600 per child.

Recommendations. If the Legislature’s main goal were to save money, increasing Medi‑Cal enrollment among DDS consumers would not achieve that goal. However, if it has a policy basis for wanting to increase Medi‑Cal enrollment among DDS consumers, we recommend it consider one or both of the following options to do so in a relatively cost‑effective way:

- Providing more hands‑on Medi‑Cal enrollment assistance through dedicated liaisons and enrollment workers at counties and/or dedicated staff at RCs. The administrative cost of this option would range from about $2 million to $15 million and some of these costs would be eligible for federal Medicaid funding.

- Providing more education and improved materials about Medi‑Cal and the related Medicaid waiver program administered by DDS, such as by changing confusing terminology, translating forms currently provided only in English, hosting educational events, or improving training of RC staff. The total administrative cost of such options likely would not exceed $2 million.

We recommend against requiring Medi‑Cal enrollment among eligible consumers, as proposed by the Governor’s administration in May 2020. (A consumer who chose not to enroll would have had to pay the RC the equivalent of what Medicaid would have paid for RC‑coordinated services.) Not only would this approach cost the state money on net, but it potentially would discourage some families from seeking needed RC‑coordinated services.

Introduction

The Department of Developmental Services (DDS) currently serves a relatively small share of consumers who are eligible for, but not enrolled in, Medi‑Cal, the state’s Medicaid program, and Medicaid home‑ and community‑based services (HCBS) programs (which fund an array of services and supports that allow people to live in community‑based settings, rather than in institutional settings). Consequently, the state cannot draw down federal Medicaid funds to help pay for DDS services provided to these consumers—the state (through the General Fund) currently pays 100 percent of the cost. The Supplemental Report of the 2020‑21 Budget Act requires our office to evaluate Medi‑Cal enrollment processes and identify the barriers to enrollment among these DDS consumers. The Supplemental Report requires our office to provide options to address these barriers with the ultimate goal of increasing federal financial participation for regional center (RC)‑coordinated services. Our evaluation may consider opportunities for streamlining the enrollment process and educating consumers and their families/representatives about Medi‑Cal programs. Finally, the Supplemental Report requires us to include an estimate of potential General Fund savings resulting from increased federal financial participation as well as an estimate of potential costs resulting from additional administrative activities and increased utilization of Medi‑Cal benefits outside the DDS system.

This report builds on initial findings reported in an April 2021 interim update and contains four main sections: (1) background about how Medicaid works in the DDS system and the Medi‑Cal eligibility and enrollment processes, (2) findings about the potential for Medi‑Cal and waiver uptake among DDS consumers and about various enrollment challenges, (3) assessment of the fiscal implications of enrolling more consumers in Medi‑Cal and of four options for increasing enrollment in these programs, and (4) recommendations for the Legislature.

As RC‑coordinated services provided to infants and toddlers under age three in DDS’s Early Start program are not eligible for Medicaid reimbursement through DDS, we focus our analysis on DDS consumers—typically age three and older—who are eligible for RC‑coordinated services under the Lanterman Developmental Disabilities Services Act (Lanterman consumers). These are the services that can draw down federal Medicaid funds in the DDS system.

Background

How Medicaid Works in the DDS System

Nearly All of DDS’ Service Categories Are Eligible for Federal Medicaid HCBS Reimbursement. Nearly all of the types of home‑ and community‑based services coordinated by RCs for DDS consumers are eligible to receive federal Medicaid HCBS matching funds. Such services include residential services, independent and supported living services, day programs, transportation, supported employment, and respite services. In addition, some of the time spent on case management by RC staff for consumers enrolled in Medi‑Cal is eligible for Medicaid Targeted Case Management funding. Among the types of services that are not eligible to receive federal HCBS matching funds are funeral services, tutor services, day care provided by a family member, and temporary motel rooms used in emergency situations.

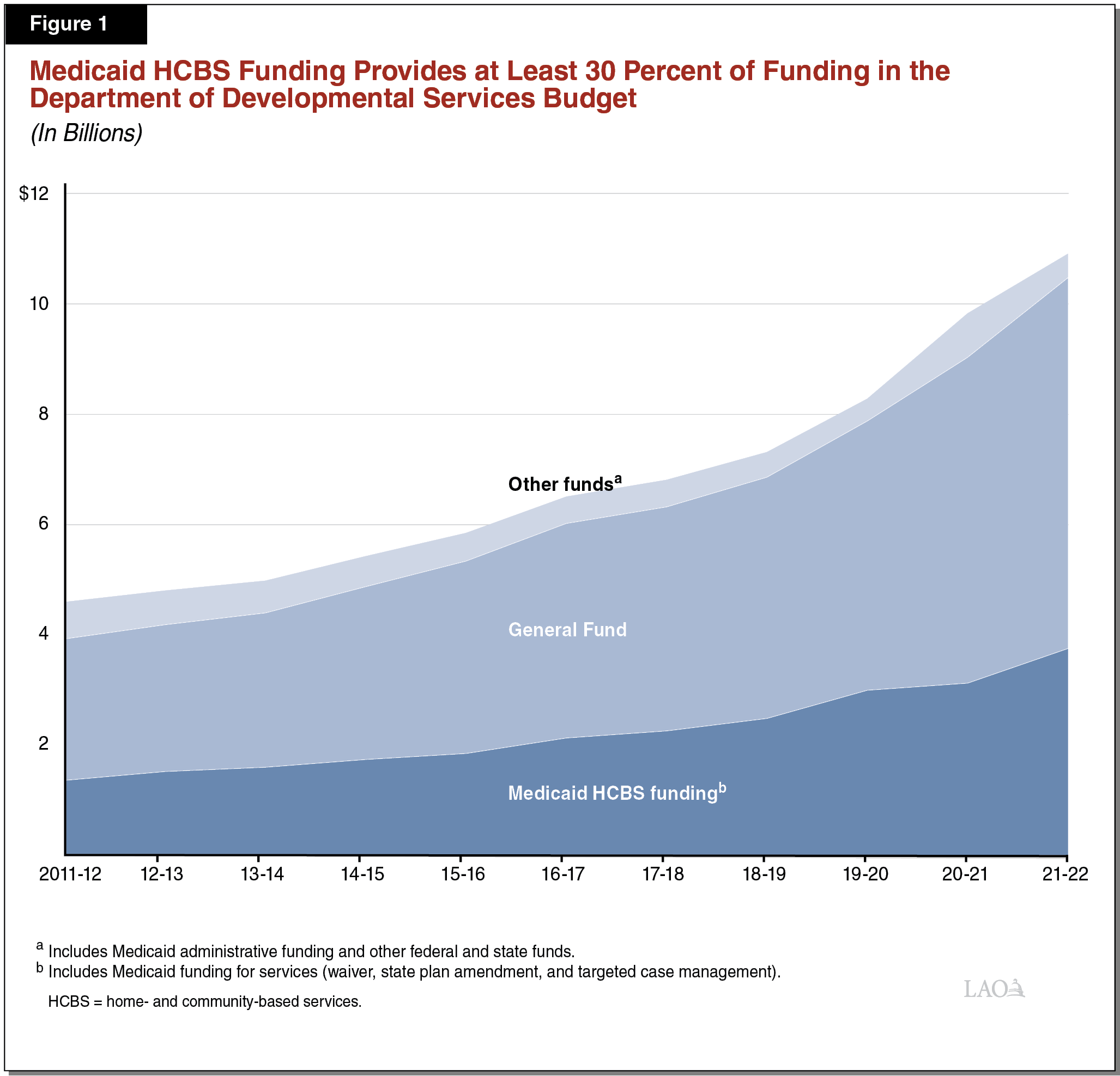

Medi‑Cal Enrollment of DDS Consumers Allows DDS to Access Federal Funding for HCBS Services Coordinated by RCs. DDS can draw down federal Medicaid funding to support HCBS services coordinated by RCs and provided to certain consumers who are enrolled in Medi‑Cal. This federal HCBS funding has supported at least 30 percent of DDS costs since 2011‑12 as shown in Figure 1.

For services funded by Medi‑Cal for Medi‑Cal‑eligible consumers in the DDS system, service costs are shared evenly between the state and federal governments. (The state also operates a 100 percent state‑funded Medi‑Cal program for certain individuals who are not eligible for the federally matched program due to immigration status.) If a consumer is not eligible for federally matched Medi‑Cal, the state funds the total cost of RC‑coordinated services.

RC‑Coordinated Services Draw Down Federal HCBS Funding in Two Main Ways. There are two primary authorities for federal funding for HCBS services in the DDS system—(1) a Medicaid 1915(c) HCBS waiver (which we refer to as the “waiver”), which has been in place for DDS since 1982, and (2) a Medicaid state plan amendment (which we refer to as the “1915(i) SPA”), which has been in place since 2009. The difference between the two is based on the level of care required by the consumer, with the waiver helping fund HCBS services for those with more intensive needs. California also has other Medicaid waivers (which are available to DDS consumers) that are managed in other departments, such as the Home‑ and Community‑Based Alternatives waiver, managed by the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS). An individual only can be enrolled in one waiver at a time. (Among DDS consumers enrolled in a waiver, most are in the waiver administered by DDS.) This report is focused on the waiver and 1915(i) SPA managed by DDS, the eligibility for which are described below.

- Waiver Eligibility: Consumers must be a legal resident, enrolled in full‑scope Medi‑Cal, live in a community‑based setting, and receive at least one RC‑coordinated service. (Some individuals—particularly children—receive only case management from RCs and either do not need RC‑coordinated services or receive the needed services outside of the RC system, such as through schools.) They also must need a level of care equivalent to that provided at an intermediate care facility (ICF) for the developmentally disabled, a licensed health facility that is considered a more institutional setting. An ICF level of care is defined as having two moderate or severe support needs in one or more of the following areas: self‑help, such as dressing or toileting; social‑emotional to address such issues as aggression, self‑injurious behavior, or running away; or health, such as tracheostomy care, apnea monitoring, or oxygen therapy. To enroll, the consumer, parent, guardian, or legal representative must complete a DDS form called the “Medicaid Waiver Consumer Choice of Services/Living Arrangement” (which we refer to as the “DDS choice form”) indicating that they have chosen a community‑based residence for the consumer, rather than an ICF.

- 1915(i) SPA Eligibility: Consumers must be a legal resident, enrolled in Medi‑Cal, and live in a community‑based residence. They do not need the same level of care as someone enrolled in the waiver. No forms or enrollment are required for the 1915(i) SPA; DDS can seek reimbursement from Medicaid once the consumer uses an RC‑coordinated HCBS service.

Medi‑Cal Pays for a Variety of Services, but the DDS Budget Reflects Only Case Management and HCBS Services. In addition to HCBS services coordinated by RCs, DDS consumers who are enrolled in Medi‑Cal also may receive other Medi‑Cal services, such as medical and dental care, and potentially may be eligible to receive in‑home supportive services (IHSS). (Medi‑Cal also funds non‑HCBS services provided in more institutional settings, like ICFs or skilled nursing facilities [SNFs]). While RC staff may help consumers access these other Medi‑Cal services, the costs of these Medi‑Cal services are not reflected in the DDS budget. Rather, these costs are reflected in other state departmental budgets, such as the DHCS budget for health care services (including ICFs and SNFs) and the Department of Social Services budget for IHSS. In addition, schools also may work with DHCS to seek Medi‑Cal reimbursement for therapies provided to children with developmental disabilities or delays.

Medi‑Cal Eligibility and Enrollment for DDS Consumers

Medi‑Cal Eligibility Pathways. Before enrolling in the waiver or becoming eligible for 1915(i) SPA reimbursement, DDS consumers must first enroll in Medi‑Cal. Individuals with developmental disabilities tend to qualify for Medi‑Cal through one of the following eligibility pathways, also shown in Figure 2:

- Automatic Eligibility Based on Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP) Qualification. Individuals who receive SSI/SSP cash assistance are automatically eligible for Medi‑Cal. SSI/SSP is available to individuals who are age 65 or older, blind, or disabled and whose income and resources fall below specified thresholds. Of the DDS consumers enrolled in Medi‑Cal, the majority—about 61 percent—became eligible because they receive SSI/SSP.

- Income‑Eligibility. Medi‑Cal is a means‑tested program. In the DDS context, slightly more than 20 percent of consumers enrolled in Medi‑Cal arrive through the income‑eligibility pathway, including children whose families are income‑eligible.

- Institutional Deeming. This eligibility pathway identifies children in the DDS system whose families are not income‑eligible for Medi‑Cal, but who could benefit from enrolling in the waiver because they live in a community setting and require an ICF level of care. Because of the needed level of care, this pathway disregards the parents’ income and considers only the child’s income to determine Medi‑Cal eligibility. (A child’s income includes any child support or trust fund income.) Institutional deeming also is an option for a married adult who requires an ICF level of care, but whose spouse’s income would disqualify them for Medi‑Cal. In this case, the spouse’s income can be disregarded in determining Medi‑Cal eligibility. Overall, somewhat fewer than 10 percent of DDS consumers enrolled in Medi‑Cal are eligible via institutional deeming and most are children.

- Other. There are a few other ways DDS consumers can enroll in Medi‑Cal. For example, until the age of 26, current and former youth in the foster care system are automatically eligible for Medi‑Cal (approximately 1.4 percent of DDS consumers enrolled in Medi‑Cal are eligible for this reason).

Figure 2

Main Medi‑Cal Eligibility Pathways Among

Department of Developmental Services Consumers

2019‑20

|

Medi‑Cal Eligibility Pathway |

Total |

Under Age 18 |

Age 18 and Older |

|

SSI/SSP |

61% |

44% |

73% |

|

Income |

22 |

29 |

17 |

|

Institutionally deemed |

9 |

21 |

1 |

|

Othera |

8 |

6 |

9 |

|

Totals |

100% |

100% |

100% |

|

aOther includes current and former foster youth under age 26. |

|||

Counties Manage Medi‑Cal Enrollment. While RCs manage waiver enrollment and DDS manages 1915(i) SPA reimbursements, county governments manage Medi‑Cal eligibility determinations, including for DDS consumers. California uses a federally approved application, which is the same for both Medi‑Cal and Covered California. People may apply online, by mail, in person at the county office, or by phone. The eligibility process uses information about each family member in a household—such as income, resources, size of household, and disability—to determine the scope of benefits available to the family and the family’s share of cost, if any (most often, there is no share of cost). The process is guided by federal law. If the applicant(s) is eligible for Medi‑Cal through more than one pathway, the process is designed to automatically base eligibility on what is most beneficial (in terms of scope of benefits and share of cost) for the applicant(s). If an RC has determined that an individual requires an ICF level of care, but that they may not be eligible for Medi‑Cal through typical income‑based pathways and should be considered under institutional deeming, they will send the county a DHCS referral form indicating that the “eligibility determination waives parental and spousal income and resources.” The county will then send an application directly to the consumer and consumer’s family. The DHCS waiver referral form instructs the county to send both the consumer as well as the RC a notice when the Medi‑Cal determination has been completed. In addition, the DHCS Medi‑Cal Eligibility Procedures Manual notes that the county may share ongoing eligibility information with the RC.

Medi‑Cal Enrollment Assistance Options Are Available. There are several options available to assist individuals with Medi‑Cal applications, some of which are tied to the Covered California application process. For example, a public agency (RCs are considered public agencies in regulations) can file an application on behalf of an individual who cannot apply on their own. An applicant can designate someone as their Medi‑Cal authorized representative (RCs or individual RC service coordinators can be designated as such) to assist with the application and interact with the county. In addition, county eligibility workers can be placed off‑site (such as at a hospital) or make off‑site visits to assist applicants. Via Covered California, certain organizations—including nonprofit community organizations—can become Certified Application Entities or Certified Enrollment Entities with certified counselors. The latter can enroll an applicant in Medi‑Cal (or a Covered California plan).

RCs Manage Waiver Enrollment. Two different types of RC staff manage waiver enrollment:

- Qualified Intellectual Disability Professionals (QIDPs) Ensure Consumers Meet Requirements for Waiver Enrollment. Most RCs have small teams of dedicated staff who specialize in the area of federal programs. These staff include one or more QIDPs, as required by DDS’ agreement with the federal government. In addition to ascertaining whether a consumer meets the ICF level of care criteria for initial waiver enrollment, QIDPs also manage required annual waiver recertifications. In addition, federal programs staff routinely review case records to see who else might be eligible for the waiver. The federal programs teams may terminate consumers from the waiver if the level of care required has changed or the consumer has lost Medi‑Cal eligibility. DDS and the federal government regularly audit RCs to ensure federal waiver reimbursements have been claimed properly.

- RC Service Coordinators Work Directly With Families. RC service coordinators work directly with consumers and their families to facilitate waiver enrollment with support from QIDPs. The service coordinator typically is responsible for ensuring the family has reviewed and signed the DDS choice form. In addition, a service coordinator may identify a consumer as potentially eligible for the waiver and alert federal programs staff.

Medi‑Cal Can Be Used for Primary or Secondary Insurance Coverage. If an individual, such as a child who is eligible through institutional deeming, already has private health insurance coverage, Medi‑Cal can act as a secondary payer for primary insurance co‑pays or uncovered costs. In some instances, a family may be required to pay a share of cost for health care services before Medi‑Cal payments are provided. This typically happens when income is higher (either the family’s income under typical income‑based pathways or the child’s income under institutional deeming).

For a Small Share of Beneficiaries, Medi‑Cal Seeks Repayment for Services From Their Estates After Death. The Medi‑Cal program is federally required to seek repayment from the estates of Medi‑Cal beneficiaries upon their death, if they have an estate subject to probate and meet other criteria. The criteria were narrowed by state statute in 2017 to limit estate recovery to the minimum required by federal law. Estate recovery applies to an individual who either was permanently institutionalized (at a SNF, ICF, or other medical facility) or received HCBS services at age 55 or older. It does not apply if there is a surviving spouse or registered domestic partner, a surviving child under age 21, or a surviving child who is blind or disabled. If the individual owned a home at the time of death that is worth 50 percent or less than the average home in the county, that home is not subject to estate recovery.

Findings

In this section, we first provide a summary of Medi‑Cal, waiver, and 1915(i) SPA statistics among DDS consumers. We then discuss the limits to potential Medi‑Cal uptake (and thus waiver and 1915(i) SPA enrollment), some of the possible reasons people may choose not to enroll, and some of the challenges that exist in the enrollment process.

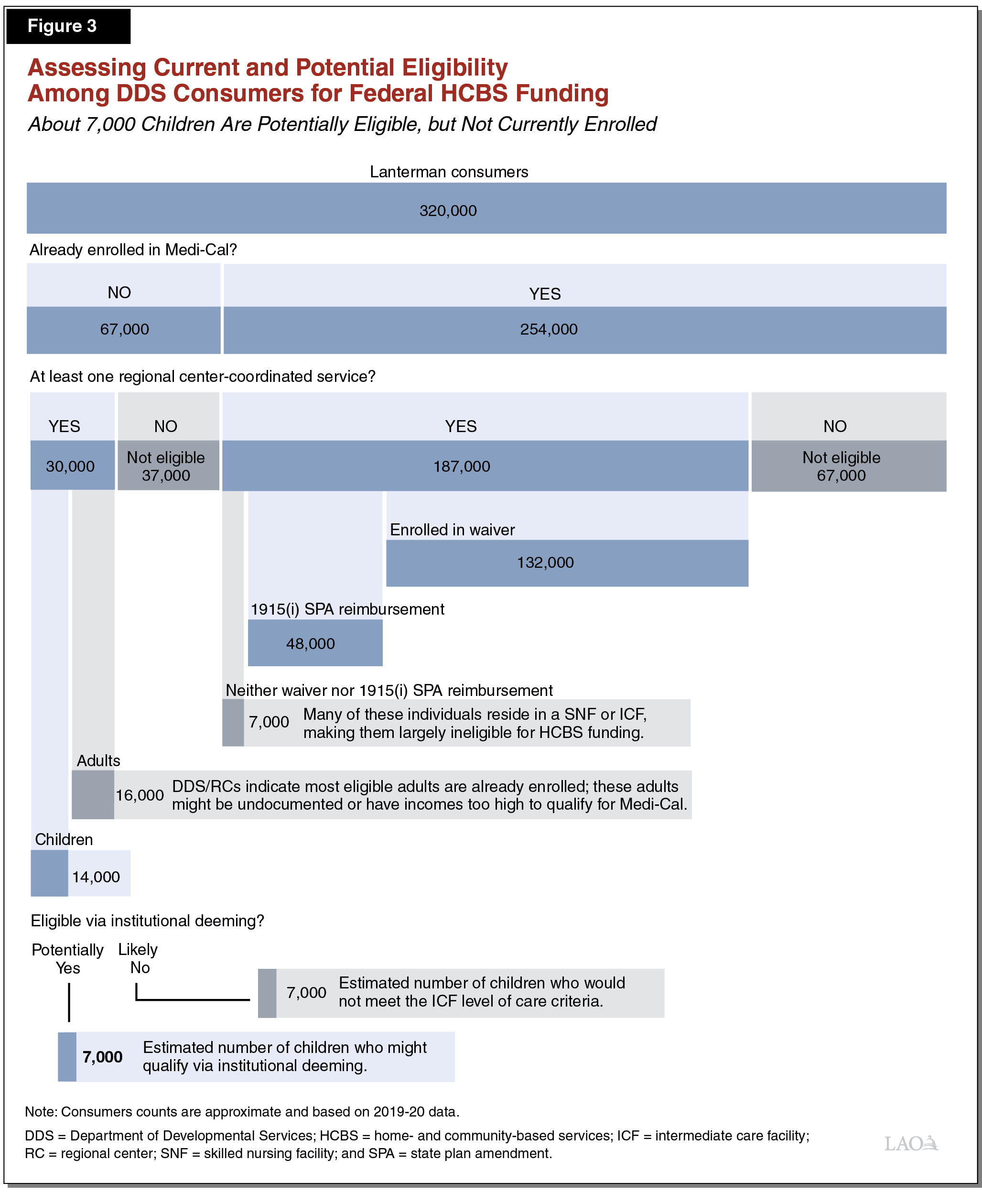

About Eight in Ten DDS Consumers Already Are Enrolled in Medi‑Cal. Figure 3 shows about 254,000 out of about 320,000 DDS consumers (or 79 percent) were enrolled in Medi‑Cal in 2019‑20. Of the 254,000 enrolled in Medi‑Cal, a total of 187,000 (or 74 percent) received at least one RC‑coordinated service, a prerequisite for waiver or 1915(i) SPA eligibility; about 132,000 of these consumers (or 52 percent of those enrolled in Medi‑Cal) were enrolled in the waiver, while about 48,000 (or 19 percent of those enrolled in Medi‑Cal) received 1915(i) SPA reimbursement.

Among the 7,000 who received an RC‑coordinated service, but did not receive waiver or 1915(i) SPA reimbursement, many lived in ICFs or SNFs, which, for the most part, makes them ineligible for HCBS funding. Furthermore, some of the 7,000 were enrolled in a waiver program administered by another department. As noted earlier, individuals only can be enrolled in one waiver at a time.

About 67,000 DDS consumers (or 21 percent) were not enrolled in Medi‑Cal, but importantly, more than half of these consumers (about 37,000) did not receive an RC‑coordinated service and would not be eligible for waiver enrollment or would not receive 1915(i) SPA reimbursement. Below, we discuss the potential for enrolling the remaining 30,000 individuals.

Uptake Potential

Potential Additional Enrollment of DDS Consumers in Medi‑Cal Is Fairly Limited. The proportion of DDS consumers enrolled in Medi‑Cal has increased over the past decade. In 2010, 74 percent of consumers were enrolled in Medi‑Cal, whereas today, 79 percent are enrolled. Among children, enrollment has increased by more than 10 percentage points since 2010, from 59 percent to 71 percent. The nearby box describes some of the efforts taken in recent years to increase enrollment. Consequently, most consumers eligible for Medi‑Cal likely already are enrolled.

Previous Efforts to Increase Federal Reimbursement for RC‑Coordinated Services

There have been several initiatives in the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) system to maximize the number of consumers drawing down federal Medicaid home‑ and community‑based services (HCBS) funding. For example, DDS used to set waiver enrollment targets for regional centers (RCs) and provide a payment to RCs for each new consumer enrolled in the waiver, although this incentive was eliminated in 2010‑11 as a cost‑savings measure. In 2009, the state pursued the Medicaid state plan amendment (1915(i) SPA) in order to receive federal reimbursement for Medi‑Cal‑enrolled consumers who received RC‑coordinated HCBS services but did not require an intermediate care facility level of care. Chapter 37 of 2011 (AB 104, Committee on Budget) added a new requirement that upon intake and assessment for RC services, the consumer must provide a copy of their health benefit card, in part to allow RCs to maximize federal waiver and 1915(i) SPA reimbursements among those enrolled in Medi‑Cal. RCs’ contracts with DDS also stipulate that the RC will pursue an “aggressive enrollment effort” to ensure willing and eligible consumers are enrolled in the waiver.

The combined effect of these efforts (and potentially the rollout of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act) has boosted the overall percentage of DDS consumers receiving federal Medicaid HCBS funding to about 56 percent (about 71 percent of consumers enrolled in Medi‑Cal). The proportion of all consumers enrolled in the waiver (just over 40 percent) has increased several percentage points since 2006‑07 and the introduction of the 1915(i) SPA has led to another 15 percent of DDS consumers drawing down federal funding for their RC‑coordinated HCBS services.

Uptake Potential Likely Limited to Children Through Institutional Deeming. Of the approximately 30,000 individuals who were not enrolled in Medi‑Cal in 2019‑20 and who did receive an RC‑coordinated service, about 16,000 were adults. Both DDS and RCs indicate that most adults who are eligible for Medi‑Cal are already enrolled, meaning that this group likely includes adults who are not eligible for some reason, for example, being an undocumented immigrant or having income that is too high.

The remaining group of about 14,000 consumers are children. To receive federally matched Medicaid funding, these children would have to have legal immigration status and either be income‑eligible through their family or qualify through institutional deeming. We do not expect all 14,000 would meet these criteria. We generally assume that if a child’s family is income‑eligible for Medi‑Cal, they likely would have enrolled already. This means the most viable eligibility pathway is institutional deeming, which (a) ignores the family’s income and looks solely at the child’s income and (b) requires that the child need an ICF level of care (which qualifies them for the waiver). Even ignoring the family’s income, however, some of these children may have their own income from a trust or from child support at a level that disqualifies them for Medi‑Cal. Furthermore, using current waiver enrollment proportions as a guide, we know that at least some of these children do not require an ICF level of care. (In addition, we can assume that families of children with a particularly high level of need likely have used the institutional deeming option already.) Finally, we know that RC staff regularly review consumers’ casefiles to determine if there are individuals who might be eligible for Medi‑Cal who are not enrolled. Based on these factors, as well as discussions with DDS, we estimate that about half, at most, of the potential pool of children, or about 7,000 children, could enroll in Medi‑Cal via institutional deeming.

Medi‑Cal and Waiver Enrollment Challenges

We spoke to DDS, the Association of Regional Center Agencies, several RCs, several families, Disability Rights California, and the County Welfare Directors Association, and conducted a survey of RCs (19 of 21 responded) to better understand the Medi‑Cal and waiver enrollment processes and reasons that some families may choose not to enroll or have trouble enrolling. Because participating in the 1915(i) SPA does not require anything additional of consumers—once they are enrolled in Medi‑Cal and begin to receive RC‑coordinated HCBS services, DDS can seek federal reimbursement for those services—the remainder of the report focuses on Medi‑Cal and waiver enrollment.

Reasons Offered for Not Enrolling in Medi‑Cal or the Waiver or Being Hesitant to Do So. Some themes emerged about reasons certain families either do not want to enroll their consumer family member in Medi‑Cal or the waiver or that made them hesitant in the process of doing so. The following issues appear to happen with some frequency:

- Preference for their current commercial health insurance.

- Doubt that there is any benefit to enrolling in Medi‑Cal (especially since the consumer will receive the same RC‑coordinated services regardless).

- Hesitancy or unwillingness to provide sensitive personal and income information to Medi‑Cal, particularly through institutional deeming (to qualify a child for institutional deeming, the family still has to provide information about each family member). In addition, if the parent is undocumented, the hesitancy to provide sensitive information is heightened.

- Concerns among families that they are “waiving” some kind of right or control by enrolling their child in the waiver.

- Concerns among families that the DDS choice form (which asks about institutional settings) and/or that the phrase “institutional deeming” might mean they are agreeing to place their consumer family member in an institution.

Issues that appear to be less common include:

- Perceived stigma about accessing Medi‑Cal, which is understood to be a government program for low‑income individuals.

- Concerns about accessing a benefit they perceive as meant for more needy families (and potentially depriving a needier family of this benefit).

- Having to meet with their RC service coordinator annually (rather than every three years) for the purposes of waiver recertification.

- Concerns about Medi‑Cal estate recovery.

Challenges Associated With the Medi‑Cal Enrollment Processes. Our findings indicate that the Medi‑Cal initial enrollment and annual renewal processes have some challenges, both for RCs and for families. These include:

- Familiarity. Some families want to, or potentially want to, enroll their child in Medi‑Cal, but lack awareness or understanding of Medi‑Cal and the potential benefits.

- Paperwork. Some families have trouble completing Medi‑Cal paperwork or providing required documentation. In addition, both RCs and families indicate that families who have enrolled their child in Medi‑Cal are frustrated by the amount of paperwork required at initial enrollment and at annual renewal.

- Time Lines. If a family has been referred for institutional deeming, they have 30 days after receiving the Medi‑Cal application to submit it, along with required documentation, back to the county before the referral expires. RCs indicate this 30‑day turnaround can be problematic for some families. For consumers already enrolled in Medi‑Cal, if they miss the annual renewal deadline, they are terminated from Medi‑Cal and have to begin the initial enrollment process anew.

- Lack of Liaisons. RCs note that the Medi‑Cal enrollment process (particularly when they are recommending a family enroll in Medi‑Cal via institutional deeming) goes much more smoothly when the county has a liaison or eligibility worker dedicated to working with RC staff and RC families and who is knowledgeable of the DDS system. Many counties do not have dedicated staff, however.

- Knowledge of DDS. When a county has a high rate of turnover among Medi‑Cal eligibility workers, understanding of the DDS system and of the institutional deeming process in particular often is lacking. For example, even the nomenclature used for institutional deeming is different. While DDS and RCs use the phrase “institutional deeming,” the county and Medi‑Cal Eligibility Procedures Manual typically use “DDS waiver” or “DD waiver.”

- Communication Between Counties and RCs. Although the referral form that RCs send to counties indicate that the county should send a notification back to the RC when the Medi‑Cal eligibility determination is complete, some RCs say the county does not notify them. This makes tracking Medi‑Cal enrollment (and claiming federal funding) more difficult for RCs.

Challenges Associated With Waiver Enrollment Process. RCs note that the DDS choice form and the DHCS waiver referral form are provided only in English even though many consumers and their families are more fluent in other languages. They note that under institutional deeming, the requirement that the child be receiving an RC‑coordinated service can be complicated by a lack of available service providers. This was raised several times in the context of respite services. For example, the family may be authorized by the RC to receive respite services, but they may be unable to find a respite provider. This compromises both waiver and Medi‑Cal eligibility since eligibility under institutional deeming hinges on receipt of RC‑coordinated services. Finally, several RCs indicated that a lack of standardized waiver training from DDS makes it difficult for RC service coordinators to understand the process.

Assessment

In the first part of our assessment below, we estimate the potential fiscal effect if the state were successful in maximizing Medi‑Cal and waiver enrollments among the pool of potentially eligible DDS consumers. We estimate the potential fiscal effect in the DDS budget and then on state spending overall. In the second part of our assessment, we consider and evaluate potential options for increasing these enrollments. Each option comes with a potential administrative cost to implement it, as well as trade‑offs and likely varying levels of success at increasing Medi‑Cal and waiver enrollments. We discuss these considerations for each option.

Fiscal Implications of Increasing Medi‑Cal and Waiver Uptake Among DDS Consumers

Trying to maximize federal support of the DDS system (and thus reduce state costs in the DDS budget) was the original impetus for this report. While we estimate that increased Medi‑Cal and waiver uptake would result in modest state savings in the DDS budget, there would be costs for the Medi‑Cal benefits administered by other state departments. We estimate that these costs would outweigh the savings in the DDS budget, resulting in a net cost to the state.

Fiscal Effect in the DDS System

As discussed in the previous section, the most likely pool of potential new enrollees is children who would be eligible for the waiver under institutional deeming—at most, about 7,000 in 2019‑20. At a per person cost of about $7,000 in 2019‑20, the state spent about $49 million General Fund for the RC‑coordinated services provided to these children. If we assume that all of these children were eligible for Medi‑Cal and the waiver via institutional deeming, that all of them were enrolled, and that the DDS costs of the children’s services remained roughly the same, DDS would save about half that cost—$24 million—due to federal Medicaid reimbursements (at the 50 percent match rate for HCBS services).

Added State Costs Outside the DDS System

Although DDS likely could achieve some savings by drawing down federal funding for children who are currently 100 percent state funded, there would be added Medi‑Cal costs outside the DDS system for services such as IHSS and for regular Medi‑Cal health insurance costs. Most DDS consumers who are enrolled in Medi‑Cal via institutional deeming are in fee‑for‑service Medi‑Cal (rather than in a managed care plan). In 2019‑20, among DDS consumers under age 18 and eligible through institutional deeming, the average annual per person fee‑for‑service cost in Medi‑Cal (excluding any costs reflected in the DDS budget) was about $10,000 General Fund ($20,000 total funds). These Medi‑Cal costs include IHSS costs. If all 7,000 children could be enrolled, we estimate 2019‑20 Medi‑Cal costs at roughly $70 million General Fund ($140 million total funds). This amount—$70 million General Fund—represents a potential maximum cost. The Medi‑Cal costs for children newly enrolled via institutional deeming potentially could be lower than the costs for children already enrolled through institutional deeming (because those with more intensive needs may have sought this option already).

Bottom Line for the State—A Net Cost. Enrolling more DDS consumers under the age of 18 in Medi‑Cal and the waiver via institutional deeming would result in net costs to the state. While we estimate that enrolling an additional 7,000 children in Medi‑Cal would save about $24 million General Fund in the DDS system, the other Medi‑Cal costs for these children would be about $70 million General Fund. Consequently, the net General Fund costs would be $46 million, or about $6,600 for each child added (based on data from 2019‑20). Importantly, this cost estimate does not include administrative costs to increase enrollment, which are discussed in the next section.

Ways to Increase Medi‑Cal and Waiver Enrollment Among DDS Consumers

While enrolling more DDS consumers in Medi‑Cal would increase state costs, increasing Medi‑Cal uptake among these consumers could have other benefits and address other legislative goals. For example, while consumers’ RC‑coordinated services would not change necessarily after enrolling in Medi‑Cal, they would now be able to access other services outside the DDS system through the Medi‑Cal program. This could advance the legislative goals of improving access to needed services across the state’s various health and human services programs. Below, we assess four main approaches that we have identified that could be taken separately or in combination to increase uptake in Medi‑Cal and the waiver: (1) requiring enrollment among those who are eligible, (2) incentivizing enrollment, (3) providing hands‑on enrollment assistance, and (4) providing more education and improved materials to families and RC staff. We also estimate the potential cost to implement each option. (These costs—largely administrative in nature—are separate from and in addition to the programmatic net costs of increased Medi‑Cal and waiver enrollments that result from implementation of the options.) We discuss some of the main advantages and challenges associated with each option and assess each option using the following criteria:

- Is the Option a Cost‑Effective Way to Increase Medi‑Cal and Waiver Enrollment? Would the option likely result in significantly increased Medi‑Cal and waiver enrollment among DDS consumers? Are the costs reasonable given the associated fiscal and policy benefits? Are there any unintended outcomes?

- Is the Option Feasible? Would the option be easy to implement and operationalize across the 21 RCs?

- Is the Option Equitable? How would the option affect different groups and consumers? How does the option impact consumers’ access to services?

Require Enrollment Among Those Who Are Eligible

Requiring Enrollment Was Proposed in 2020. In the Governor’s 2020‑21 May Revision, the administration proposed requiring consumers to enroll in Medi‑Cal (if eligible) to enable RCs to seek Medicaid reimbursements for RC‑coordinated services. If the consumer chose not to enroll in Medi‑Cal when eligible, they would have been required to pay the RC the equivalent of what Medicaid would have paid for RC‑coordinated services. This proposal was not adopted as part of the final budget package; instead, our office was asked to submit this report.

Potential Cost to Require Medi‑Cal Enrollment. There would be standard additional administrative costs to process an increased number of Medi‑Cal and waiver applications (this assumes the onus is on the family to proactively submit the application). (If DDS or RCs were to assist families in the application process, the costs for those added services would be similar to the costs of the third and fourth options we describe below.) For families that choose not to enroll their consumer family member in Medi‑Cal, there would be administrative costs—likely less than $1 million annually—for RCs to bill and collect payment from those families for half the cost of any RC‑coordinated services provided to the consumer.

Advantages of Requiring Medi‑Cal Enrollment. Requiring Medi‑Cal enrollment—or otherwise requiring the family to cover the federal portion of the cost of RC‑coordinated services—would be the most direct method for trying to increase Medi‑Cal enrollment among Medi‑Cal‑eligible DDS consumers. This approach could persuade families that have hesitated or been unwilling to apply for Medi‑Cal (or who perceive a stigma) to do so by providing a financial disincentive.

Challenges With Requiring Medi‑Cal Enrollment. Making Medi‑Cal enrollment a requirement could discourage families from seeking RC‑coordinated services in the first place or from accessing all of the RC‑coordinated services for which the consumer is authorized. Moreover, some individuals and families uncomfortable with signing up for Medi‑Cal may not be able to afford what would have been the federal portion of the cost of the RC‑coordinated services. Consequently, this approach could be more punitive in nature than the three alternative approaches discussed below, given that a family would have to pay for or forgo services if they did not want to enroll the consumer in Medi‑Cal. While the requirement would not negate the statutory entitlement to RC‑coordinated services provided by the Lanterman Act, it would create a new prerequisite (applying generally to all DDS consumers) to receiving services that did not exist before. (We note that in the DDS system, there currently is one program, Self‑Determination, that recently began requiring Medi‑Cal enrollment if one is eligible. We describe the program and new requirement in the nearby box.)

Self‑Determination Program Requires Medi‑Cal Enrollment When Its Participants Are Eligible

Relatively New Home‑ and Community‑Based Services (HCBS) Waiver Helps Pay for the Self‑Determination Program (SDP). The Department of Developmental Services (DDS) receives Medicaid funding for a small number of consumers who are enrolled in Medi‑Cal and DDS’ SDP (about 750 people as of August 31, 2021). Medicaid funding is provided through an HCBS waiver approved in 2018 (which we refer to as the “SDP waiver”). The SDP waiver has the same intermediate care facility level of care criteria as the waiver. The number of consumers enrolled in this program will most likely increase, as the program was made available statewide on July 1, 2021 after a three‑year phase‑in period (during which enrollment was limited to 2,500 consumers).

SDP Will Require Medi‑Cal Enrollment, if Eligible. Although participation in the SDP is not limited to individuals who are eligible for Medi‑Cal (as it was during the phase‑in period), legislation associated with the recently enacted 2021‑22 budget stipulates that consumers who are eligible for Medi‑Cal must apply for it in a timely manner in order to participate in the program. (Currently, DDS is working on the details of how to implement this new policy.) Under the new SDP policy, Medi‑Cal‑eligible DDS consumers who do not wish to enroll in Medi‑Cal could not participate in Self‑Determination. While they still would be able to access regular RC‑coordinated services under the Lanterman Act at no cost to them, they would have less control over the design of their service plan and selection of service providers.

Assessment of Requiring Medi‑Cal Enrollment. This option would be the most likely of the four to maximize Medi‑Cal enrollment among DDS consumers in a relatively cost‑effective way. We do not anticipate significant administrative or feasibility hurdles since counties and RCs already manage Medi‑Cal and waiver enrollment, respectively. Because this requirement could discourage some consumers from seeking RC services, however, this option likely would have disparate impacts among consumers. In particular, this option could reduce access among consumers whose parents who are undocumented or are otherwise hesitant to enroll in Medi‑Cal, but who cannot afford to pay a share of cost for RC‑coordinated services. Moreover, this option would create a pre‑requisite for Lanterman Act services that did not exist previously.

Incentivize Enrollment

Another approach to increase Medi‑Cal uptake among DDS consumers is to provide an incentive to consumers and their families for enrolling. One such incentive currently exists in the DDS system for families whose minor child receives DDS services. The fees associated with two of three family fee programs—the Family Cost Participation Program and the Annual Family Program Fee—are waived when the minor consumer is enrolled in Medi‑Cal. The extent to which these programs (which were implemented in 2005 and 2011, respectively) led to increased enrollment in Medi‑Cal (because families wished to avoid paying the fees) is unclear. While DDS Medi‑Cal enrollment data show a slight uptick in enrollment among children (from 59.4 percent to 62.3 percent) between 2010 (before the Annual Family Program Fee took effect) and 2012, the cause of this uptick could have been the result of more than one factor. We note that Medi‑Cal enrollment of children as of 2019‑20 (70.9 percent) was much higher than in 2012 (62.3 percent). This increase could reflect the waiver of family fees, rollout of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2014, efforts made by RCs to increase enrollment, more families needing Medi‑Cal generally, or a combination of these.

Cost to Incentivize Enrollment. The state would incur a cost to administer and pay for incentives, however, the total cost is uncertain since it would depend on how incentives are designed. A simple hypothetical example is a cash incentive to newly enrolled consumers. A $100 incentive (as an example) for each of the 7,000 consumers would cost $700,000. There would be trade‑offs with any incentive design, however. For instance, would incentives only be provided to newly enrolled consumers? Would incentives be provided annually to ensure people renew their Medi‑Cal enrollment? Are there noncash incentive options? What level of incentive would have the desired effect of causing people to enroll?

Advantages of Incentivizing Enrollment. Properly targeted incentives could make going through the Medi‑Cal application process more attractive to families that are hesitant due to administrative burdens and other similar concerns.

Challenges With Incentivizing Enrollment. An incentive approach would not guarantee consumers enroll in Medi‑Cal. Moreover, what types of incentives would be most effective at encouraging families to enroll consumers in Medi‑Cal are unknown.

Assessment of Incentivizing Enrollment. Design and implementation of this approach would be relatively complex and the cost is uncertain. In addition, how best to structure the incentive to have the intended effect is unknown, especially since incentives already exist for the likely pool of potential enrollees (children). Given existing incentives, the effectiveness of additional incentives may be limited. Furthermore, we are not aware of obvious examples or precedents for an incentive approach in other health and human services programs. If the Legislature pursued this approach, we suggest it consider who would benefit from receiving incentives—only those consumers newly enrolling in Medi‑Cal or those already enrolled in Medi‑Cal as well?

Provide Hands‑On Enrollment Assistance

For families that have trouble navigating the Medi‑Cal application process, another approach is to provide hands‑on assistance. Such assistance could take different forms, but some options include:

- Provide Dedicated Liaisons at the County. Ensuring these liaisons understand the DDS system and institutional deeming in particular would be important.

- Have County Eligibility Workers On‑Site at RCs. Depending on the number of consumers served, these eligibility workers could work at RCs part time or full time.

- Encourage Families to Allow RC Staff to Act as Authorized Representatives for Consumers. Doing so would allow RC staff to assist with Medi‑Cal applications and follow up with the county. If a family is not comfortable making RC staff an authorized representative, RC staff still could provide more hands‑on assistance to families who need it.

Costs to Provide Hands‑On Enrollment Assistance. This option would require more staff at counties and/or at RCs. Based on the current cost of a county eligibility worker, adding at least one new full‑time eligibility worker in each of the state’s 58 counties (for example) to act as a dedicated liaison or to work on‑site at RCs would cost approximately $10 million. Based on the current cost of an RC specialist‑type employee, adding one or two specialists in each of the state’s 21 RCs would cost approximately $2 million to $5 million. Medicaid reimbursements would cover some of the costs of these additional county and RC staff.

Advantages of Providing Hands‑On Enrollment Assistance. One or more of the approaches described above would not dissuade a family from seeking RC services (as the requirement approach might) and could alleviate some of the administrative burden and confusion associated with enrolling in Medi‑Cal. Families already enrolled in Medi‑Cal also could benefit from a more help. For example, county and/or RC staff could provide families reminders about Medi‑Cal renewal deadlines and offer to help with the renewal process. In addition, having dedicated county liaisons or having county eligibility workers on‑site at RCs would make the waiver enrollment process easier for RCs since they would have county staff readily available to answer questions and provide helpful information (such as the dates by which families must renew their Medi‑Cal enrollment).

Challenges With Providing Hands‑On Enrollment Assistance. Just because hands‑on enrollment assistance is available does not mean a family will take advantage of it and use it to enroll their family member in Medi‑Cal. Moreover, providing dedicated county liaisons and/or eligibility workers for DDS consumers would increase county staffing costs. Were the state to require counties to provide this service, the state likely would have to pay for the associated cost. If RCs acted as authorized representatives or provided assistance in another way, this would add costs to the RC operations budgets.

Assessment of Providing Hands‑On Enrollment Assistance. While there is no guarantee more consumers would enroll in Medi‑Cal, providing more hands‑on assistance to help them enroll could address some of the issues raised in interviews and surveys about the application process being difficult and confusing. These changes could benefit both those already enrolled in Medi‑Cal and those newly enrolling. Moreover, improving access to Medi‑Cal enrollment services could help those families and consumers who are most deterred by the process enroll.

Provide More Education and Improved Materials About Medi‑Cal and the Waiver to Families and RC Staff

We heard from RCs and families that certain aspects of the Medi‑Cal and waiver enrollment process or the way that these programs are presented to families could be improved. Some of these aspects are within the state’s control to change easily, while others are not. For example, the institutional deeming process requires the family to complete the full Medi‑Cal application, providing personal and income information about each household member, despite the family seeking Medi‑Cal exclusively for the child who is a DDS consumer. This process likely cannot be changed easily, however, given that the Medi‑Cal application form (which is also the Covered California form) and process for determining eligibility follows federal guidelines and has federal approval.

There are other aspects of the enrollment process or presentation of information, however, that would be much easier to address. For example, some families may be unaware of the range of potential Medi‑Cal benefits, such as IHSS, or that they could have Medi‑Cal cover private insurance co‑pays or other out‑of‑pocket medical expenses of their child. Increasing education and providing improved materials could come in the form of better standardization of information, requirements about when and how information is provided, increased opportunities for providing the education (such as webinars or workshops), and increased training for RC service coordinators who then relay information to families. For example, the following changes could be considered:

- Waiver‑related forms (the DDS choice form and the DHCS waiver referral form) are only provided in English currently. These and other educational materials could be translated into other languages.

- DDS and DHCS could change the language used on forms and in educational materials, such as waiver and institutional deeming, to make them more user‑friendly and accessible. They could consult with families and other stakeholders to select language that is more understandable.

- Education could be provided in formats that are accessible to families from a wide range of backgrounds. For example, this might require online or in‑person events be offered in multiple languages or have interpreters present.

- The terminology used by RC and county staff could be standardized to reduce miscommunication between these agencies.

- More information could be provided to families about the statutory changes made in 2017 to limit what is recovered from the estates of deceased beneficiaries.

- DDS could engage all 21 RCs in regular training and educational opportunities to ensure RC staff, including service coordinators, understand Medi‑Cal, the full range of Medi‑Cal benefits potentially available to consumers, the waiver, and enrollment processes for each, among other topics. These types of RC trainings would have the added benefit of providing RC staff the opportunity to share their own best practices and discuss examples of complex cases.

Costs to Providing More Education and Improved Materials. There likely would be costs in the low millions of dollars for this approach. While we expect some of these costs (such as changing forms or standardizing information) could be absorbed by DDS, adding staff to develop and translate educational materials or conduct forums or trainings (or paying a contractor for these services) would increase costs to some degree (likely not more than $2 million in total). Some activities involving translation or interpretation likely could be covered by a recent ongoing augmentation DDS received in the 2021‑22 budget ($10 million General Fund) for language access and cultural competency orientations and training.

Advantages of Providing More Education and Improved Materials. Families could make more informed decisions based on consistent and more comprehensive information about Medi‑Cal with better educational outreach. Particularly in combination with hands‑on enrollment assistance, this approach could dispel misinformation about Medi‑Cal. For some families, understanding the other benefits of Medi‑Cal outside the DDS system, such as IHSS and/or coverage of private insurance co‑pays, could be incentive enough for them to apply. Moreover, providing better and more consistent information could have benefits for those families already enrolled in Medi‑Cal.

Challenges With Providing More Education and Improved Materials. Increased education would not guarantee a family would enroll the consumer in Medi‑Cal. Moreover, given the relatively limited pool of possible enrollees, the cost of the outreach could outweigh the benefits of enrolling more consumers in Medi‑Cal and the waiver.

Assessment of Option to Provide More Education and Improved Materials. This approach would include numerous low‑cost options for increasing awareness about Medi‑Cal benefits and the enrollment process. It also is highly feasible—it would involve changes to forms; translation of forms; and development and implementation of trainings, webinars, and other outreach and education options. While some of these efforts would take more time, planning, and stakeholder engagement than others, they do not require changing anything significant about enrollment rules or regulations. This option could improve equity by ensuring that all families understand the range of benefits for which they are available, in a language and format they understand.

Recommendations

Based on our fiscal assessment, enrolling more DDS consumers in Medi‑Cal and the waiver would not save the state money on net and actually would increase state costs given that more individuals would be receiving state benefits across programs in several departments. Accordingly, if the primary legislative goal of increasing Medi‑Cal and waiver enrollments in DDS were to save money, then our analysis suggests that maximizing these enrollments would not achieve that result.

However, if the primary legislative goal were to maximize uptake in benefit programs for which individuals are eligible, the Legislature could consider option 3 (providing hands‑on enrollment assistance) and/or option 4 (providing more education and improved materials to families and RC staff). The relative benefits of option 3 versus option 4 depends on legislative priorities. For example, if the Legislature would like to increase enrollments among the eligible, but do so without increasing administrative costs significantly, we recommend it require DDS to pursue option 4. If the Legislature is less worried about administrative costs, and sees benefit in helping both new enrollees as well as those already enrolled with hands‑on assistance, it could consider requiring DDS and counties to pursue option 3. At a minimum, we recommend the Legislature require DDS and DHCS to translate forms (the DDS choice form and the DHCS waiver referral form) into languages used by DDS consumers and their families. This is a simple, low‑cost way to increase enrollments among at least some of the eligible, but currently unenrolled, individuals.

We do not recommend the Legislature pursue options 1 (requiring enrollment) or 2 (incentivizing enrollment). Option 1—which had been proposed by the administration as a budget solution in 2020—not only would not save the state money on net, but it potentially would discourage some low‑income or undocumented families from seeking needed RC‑coordinated services. Option 2 would come with an uncertain cost, be complicated to design and implement, and may not be particularly effective.

Conclusion

The purpose of this report was to explore ways to increase Medi‑Cal enrollment among DDS consumers as a way to increase federal reimbursements through the waiver and 1915(i) SPA and to provide a fiscal estimate of the total impact on state spending. We find that the potential for increasing Medi‑Cal enrollment among DDS consumers is limited, given that most eligible adults are enrolled already and many children do not receive an RC‑coordinated service (a prerequisite for institutional deeming). Moreover, we find that although more enrollments would save the state money in the DDS system, they would lead to a net cost to the state once other Medi‑Cal costs are considered. The Legislature still might see a policy rationale for enrolling more eligible individuals in Medi‑Cal, however, and we find that providing hands‑on assistance and improving and expanding education and awareness about the Medi‑Cal and waiver programs would be the best approaches for achieving that goal.