LAO Contact

February 9, 2022

The 2022-23 Budget

The Governor’s Homelessness Plan

- Background

- Update on Major Recent State Actions Addressing Homelessness

- Governor’s 2022‑23 Homelessness Proposals

- LAO Comments

- Conclusion

Summary

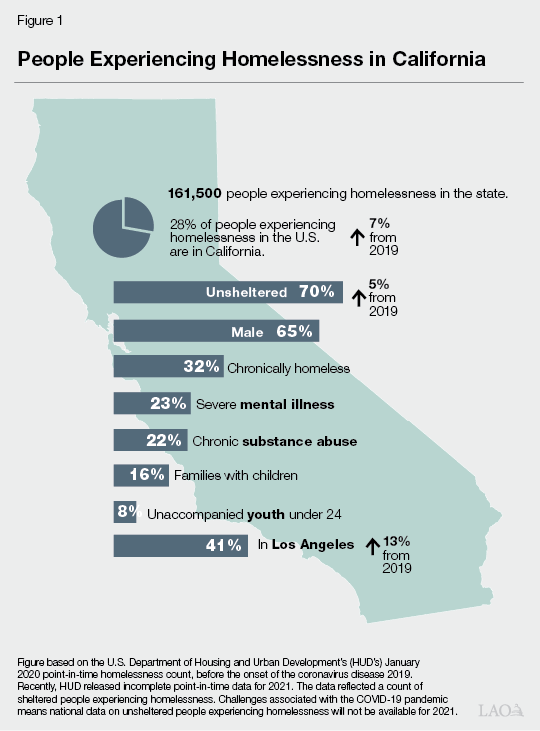

Homelessness in California. While homelessness is a complex problem with many causes, the high costs of housing is a significant factor in the state’s homelessness crisis. Rising housing costs that have exceeded growth in wages, particularly for low‑income households, put Californians at risk of housing instability and homelessness. In California, around 2.5 million low‑income households are cost burdened. More people experience homelessness in California than any other state. As of January 2020—the most recent year federal data is available—California had about 161,500 individuals experiencing homelessness.

Shifting State‑Local Relationship. Historically, local entities have provided most of the homelessness assistance in their jurisdiction, relying in part on federal and state funding. As the homelessness crisis has become more acute, the state has taken a larger role in funding and supporting local governments’ efforts to address homelessness. The state has increased its role in addressing homelessness by providing significant, albeit one‑time and temporary, funding towards infrastructure and flexible aid to local governments in recent years.

Update on Key Recent Homelessness State Spending. Recent budget actions reflect the increased role of the state in addressing homelessness. The state budget provided a total of $7.2 billion ($3.3 billion General Fund) in 2021‑22 to about 30 homelessness‑related programs across various state departments. We provide implementation updates for several of the major, recent homelessness augmentations.

Homelessness Package Proposes to Focuses on Near‑Team Needs. The Governor’s 2022‑23 budget proposes $2 billion one‑time General Fund over two years that is intended to address near‑term homelessness needs while previously authorized funds for long‑term housing solutions are implemented: $1.5 billion for behavioral health “bridge” housing and $500 million for the Encampment Resolution Grants Program.

Devote Attention to Overseeing Recent Augmentations. We suggest the Legislature dedicate the early part of the budget process to overseeing the implementation of last year’s significant homelessness augmentations. Prior to authorizing increased funding for the activities proposed in the 2022‑23 budget, ensuring that the homelessness efforts authorized in prior budgets are operating effectively, adequately supported, and can be maintained over time will be important.

Consider Long‑Term Plan for Ongoing Homelessness Efforts. Addressing this crisis requires a complex combination of services and infrastructure. As more information about recent state efforts becomes available, we suggest the Legislature assess which types of interventions appear most effective. This information could help guide the state’s long‑term fiscal and policy role in addressing homelessness.

For Any Authorized Funds, Set Clear Expectations and Establish Metrics to Assess Performance. Setting clear expectations through statute and establishing reporting requirements to facilitate oversight over the state’s progress towards addressing homelessness will be critical.

Background

Housing Affordability Affects Homelessness. The state is facing a severe affordable housing crisis. Not surprisingly, those living in poverty are the most significantly affected. Rising housing costs that have exceeded growth in wages, particularly for low‑income households, put Californians at risk of housing instability and homelessness. In California, around 2.5 million low‑income households are cost burdened (spend more than 30 percent of their incomes on housing). Over 1.5 million low‑income households face even more dire cost pressures—spending more than half of their income on housing. For this population, job loss or an unexpected expense could result in homelessness.

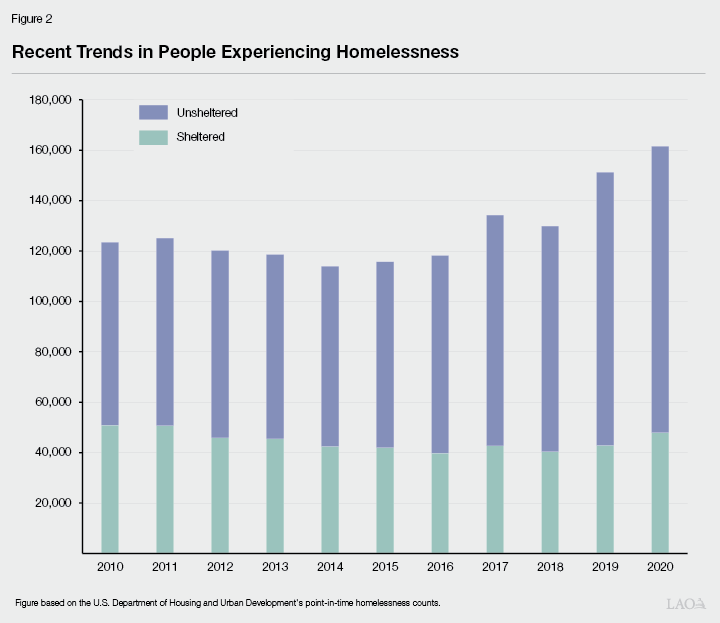

Homelessness in California. While homelessness is a complex problem with many causes, the high costs of housing is a significant factor in the state’s homelessness crisis. More people experienced homelessness in California than any other state. As of January 2020—the most recent year complete federal data is available—California has about 161,500 individuals experiencing homelessness, which represents about 28 percent of the total homeless population in the nation. (California’s overall population, however, is about 12 percent of the nation.) Figure 1 provides additional details about people experiencing homelessness in California in 2020. Additionally, the state’s Homeless Data Integration System (HDIS)—which tracks people served in the state—identified that 246,100 unique people accessed some form of homelessness service in the state in 2020—159,400 individuals and 83,500 families with children. Included in the individual and family totals are 24,300 unaccompanied youth. Finally, Figure 2 depicts how the state’s sheltered and unsheltered homeless populations have changed between 2010 and 2020. Recently, HUD released 2021 PIT count data for sheltered people experiencing homelessness. Challenges associated with the COVID‑19 pandemic means national data on unsheltered people experiencing homelessness will not be available for 2021. California had 51,400 sheltered people experiencing homelessness in 2021, a 5 percent increase in the population of sheltered people relative to 2020. The box below describes the challenges collecting accurate and timely homelessness data.

Challenges Collecting Accurate and Timely Homelessness Data

Federal Government and States Rely on Point‑in‑Time Counts. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) requires Continuums of Care (CoCs) to conduct point‑in‑time (PIT) counts of people experiencing homelessness, generally on a single night in January. CoCs are required to conduct a PIT count of homeless individuals who are “sheltered” annually and a PIT count of individuals who are “unsheltered” at least once every two years, though CoCs may choose to conduct an unsheltered count annually. HUD requires CoCs to conduct PIT counts as a condition of receiving federal funding and uses the data to determine allocations of federal funds. States and local entities also rely on PIT data to inform their response to homelessness.

Homeless Population Likely Larger Than Available Data Reveals. Various factors, including difficulty reaching all unsheltered individuals, limitations on counting all forms of homelessness, and capacity constraints of CoCs complicate efforts to produce an accurate count. The expert consensus is that the HUD PIT count underrepresents the homeless population.

COVID‑19 Further Complicates Data Availability and Accuracy. Federal reporting from the January 2020 PIT count (before the onset of COVID‑19) is available. Recently, HUD released 2021 PIT count data for people experiencing sheltered homelessness. Due to public health concerns associated with the pandemic, a federal waiver for the January 2021 PIT count means data will not be available for unsheltered homelessness that year. HUD is requiring the full January 2022 PIT count to move forward—sheltered and unsheltered. However, many jurisdictions are delaying their count to the end of February 2022 to allow time for the current surge in COVID‑19 cases to subside. This means that the first federal PIT count data reflecting the impact of COVID‑19 on homelessness will likely not be available until early 2023.

State’s New Homelessness Data Integration System Offers More Information. The Homeless Data Integration System (HDIS) administered by the California Interagency Council on Homelessness (Cal ICH), which became operational in 2021, allows the state to access and compile standardized data collected by CoCs about the people they serve. Cal ICH anticipates updating the system to focus more on the outcomes of people accessing services to help the state and local entities better assess their progress toward preventing, reducing, and ending homelessness. While this data would not replace the PIT count data, it can complement PIT count data by providing more information about the delivery of homelessness services in the state and captures a broader population of people experiencing housing instability.

Shifting State‑Local Relationship. Historically, local entities have provided most of the homelessness assistance in their jurisdiction, relying in part on federal and state funding. As the homelessness crisis has become more acute, the state has taken a larger role in funding and supporting local governments’ efforts to address homelessness. Initially, the state provided flexible funding directly to local entities to address homelessness in their own communities. However, the state expanded its support and approach following the emergence of the COVID‑19 pandemic. In response to concerns that the pandemic would place more people at risk of homelessness and further harm people experiencing homelessness, the state invested significant resources in infrastructure—such as the purchase, renovation, and modification of former hotels—to house people experiencing or at risk of homelessness. This new homelessness infrastructure, which is still coming online, is to be owned and operated locally. Concurrently, the state continued to provide local entities flexible homelessness assistance on a one‑time basis year after year. Overall, the state has increased its role in addressing homelessness by providing significant, albeit one‑time and temporary, funding towards infrastructure and flexible aid to local governments in recent years.

Recent Homelessness State Spending. Recent budget actions reflect the increased role of the state in addressing homelessness. Figure 3 summarizes major recent homelessness state spending actions.

Figure 3

Major Recent State Homelessness Spending

(In Millions)

|

Program |

Amounta |

Funding Type |

State Administrator |

|

2018‑19 |

|||

|

No Place Like Home |

$2,000 |

One time |

HCD |

|

HEAP |

500 |

One time |

HCFCb |

|

Total |

$2,500 |

||

|

2019‑20 |

|||

|

HHAPP Round 1 |

$650 |

One time |

HCFC |

|

COVID‑19 Emergency Homelessness Funding |

100 |

One time |

HCFC |

|

Project Roomkey |

50 |

One time |

DSS |

|

Total |

$800 |

||

|

2020‑21 |

|||

|

Homekey Program |

$800 |

One time |

HCD |

|

HHAPP Round 2 |

300 |

One time |

HCFC |

|

Project Roomkey |

62 |

One time |

DSS |

|

Total |

$1,162 |

||

|

2021‑22 |

|||

|

Homekey Program |

$1,450 |

Temporaryc |

HCD |

|

HHAPP Round 3 |

1,000 |

Temporaryd |

HCFC |

|

Community Care Expansion Program |

805 |

One time |

DSS |

|

Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program |

756 |

Temporarye |

DHCS |

|

CalWORKs Housing Support Program Expansion |

190 |

Temporaryf |

DSS |

|

Project Roomkey |

150 |

One time |

DSS |

|

Housing and Disability Advocacy Program Expansion |

150 |

Temporaryg |

DSS |

|

Bringing Families Home Program Expansion |

93 |

Temporaryh |

DSS |

|

Home Safe Program Expansion |

93 |

Temporaryi |

DSS |

|

Encampment Resolution |

50 |

One time |

HCFC |

|

Total |

$4,737 |

||

|

aAll fund sources. bHCFC is now the California Interagency Council on Homelessness. cThe budget also authorized $1.3 billion in 2022‑23 for the Homekey Program. dThe budget also authorized $1 billion in 2022‑23 for HHAPP Round 4. eThe budget also authorized $1.4 billion in 2022‑23 and $2.1 million in 2023‑24 for the Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program. fThe budget also authorized $190 million in 2022‑23 for the CalWORKs Housing Support Program Expansion. gThe budget also authorized $150 million in 2022‑23 for the Housing and Disability Advocacy Program Expansion. hThe budget also authorized $93 million in 2022‑23 for the Bringing Families Home Program Expansion. iThe budget also authorized $93 million in 2022‑23 for the Homekey Program. |

|||

|

HCD = Housing and Community Development; HEAP = Homeless Emergency Aid Program; HCFC = Homeless Coordinating and Financing Council; HHAPP = Homeless Housing, Assistance and Prevention Program; DSS = Department of Social Services; and DHCS = Department of Health Care Service. |

|||

Progress in State’s Response... In the past, our office has noted the challenges associated with providing funding for homelessness that is (1) one‑time or temporary in nature; (2) provided across multiple agencies, departments, and levels of government; (3) not tied to specific outcome measures, goals, or a particular strategy; and (4) not overseen and coordinated by one particular entity. Although these are challenging issues that are not solved quickly, California has made some notable progress in creating a state infrastructure and portfolio of programs to address homelessness since 2018‑19 when the state began taking a more active role in addressing homelessness. In particular, the recent statutory changes to the responsibilities and composition of the Homelessness Coordinating and Financing Council (HCFC)—now known as the California Interagency Council on Homelessness (Cal ICH)—encourages greater coordination among the various state entities involved in addressing homelessness. The box below explains Cal ICH’s original creation and recent changes to the council’s composition. Additionally, the recent roll out of HDIS is a step forward in the state’s access to centralized information about the delivery of homelessness services across the state. Over time, as the system compiles more detailed information about the homelessness services delivered locally, this system may help inform state policy and budget decisions. Finally, more recent rounds of flexible funding for local governments have included requirements, such as local action plans and outcome goals, that will facilitate oversight, accountability, and the ability to track local governments’ progress.

The California Interagency Council on Homelessness

Established to Oversee Housing First Policy. In 2017, the Housing First model was adopted in the state by Chapter 847 of 2016 (SB 1380, Mitchell). It required state housing programs to adopt the model. Housing First is an approach intended to quickly and successfully connect individuals and families experiencing homelessness to permanent housing without preconditions and barriers to entry, such as sobriety, treatment, or service participation requirements. Supportive services are offered to enhance the prospect of achieving housing stability and prevent returns to homelessness as opposed to addressing predetermined treatment goals prior to providing permanent housing. Housing First emerged as an alternative to a housing philosophy that required individuals experiencing homelessness to first complete short‑term residential and treatment programs before securing permanent housing. Under this prior model, permanent housing was offered only after an individual experiencing homelessness could demonstrate that they were “ready” for housing. The California Interagency Council on Homelessness (Cal ICH) is responsible for monitoring state programs’ compliance with Housing First. While confirmation was pending as of November 2021 for some programs administered by the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services (Cal OES), many other programs—including those administered by the Housing and Community Development Department and Department of Social Services—were found to be complying by Cal ICH.

Recent Statutory Changes to Cal ICH. In addition to overseeing compliance with the state’s Housing First policy, Cal ICH now directly administers the $3.45 billion in previously authorized flexible state funding provided to local entities. Legislation recently updated the council’s structure and membership in ways that facilitate better coordination across state entities that administer other homelessness‑related programs. Specifically, (1) requiring the Secretary of the California Health and Human Services Agency to serve as a co‑chair with the Secretary of the Business, Consumer Services, and Housing Agency; (2) requiring existing member agencies and departments to be represented by the Director or Secretary rather than by a representative, except for the California Department of Education; and (3) adding the Director of the Departments of Aging, Director of the Departments of Rehabilitation, Director of the Departments of State Hospitals, Director of the Departments of Cal OES the State Public Health Officer, and the executive director of the California Workforce Development Board. How these changes to Cal ICH that are intended to break down silos will work in practice is as yet unknown.

…But Long‑Term Planning and Funding Remains Necessary. Despite this progress in the state’s engagement and response, the scale of the homelessness crisis in California is significant and continued work and resources will be necessary to address the state’s homelessness challenges. Past budget actions and the Governor’s 2022‑23 budget continue to rely on one‑time and temporary funding. In order to meaningfully address homelessness, the state likely will need to have a continued fiscal role and set a clear, long‑term strategy. To this end, determining the balance of the state‑local relationship—both programmatically and fiscally—over the long‑term will be important. Programmatically, local entities are most knowledgeable about the specific homelessness‑related challenges facing their communities and are better positioned than the state to deliver services. In recognition of this, local entities traditionally have been given significant discretion over how state funds are spent to address homelessness. However, the state can help to coordinate and guide local action based on best practices and statewide interests. Fiscally, striking a balance between state and local responsibility may be more complex. Most recently, the state has focused on providing infrastructure funding, which otherwise could be challenging for local governments to raise. Having a clear balance of the state‑local relationship would help inform what types of activities the state should fund and over what time horizon, making it more likely that the state’s investments would have a meaningful, ongoing impact on homelessness.

Summary of Major 2022‑23 Homelessness Proposals. The Governor’s 2022‑23 budget proposes $2 billion General Fund over two years for two major homelessness proposals. Figure 4 provides an overview of the homelessness budget proposals.

Figure 4

Major 2022‑23 Homelessness Budget Proposals

(In Millions)

|

Proposal |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

Fund Source |

State Administrator |

|

Behavioral Health Bridge Housinga |

$1,000 |

$500 |

General Fund |

DHCS |

|

Encampment Resolution Grants Program |

500 |

— |

General Fund |

Cal ICH |

|

aThis funding is proposed to be provided through the existing Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program. |

||||

|

DHCS = Department of Health Care Services and Cal ICH = California Interagency Council on Homelessness. |

||||

Update on Major Recent State Actions Addressing Homelessness

In this section, we provide implementation updates for several of the major, recent homelessness augmentations. While Figure 3 shows that the major recent augmentations span four departments and an even larger number of programs, the 2021‑22 budget actually provided even more funding—a total of $7.2 billion ($3.3 billion General Fund)—to about 30 homelessness‑related programs in additional state departments that are not all shown in the figure. Beyond the various state housing departments, the 2021‑22 budget also funds homelessness programs in the human services, health, veterans, transportation, higher education, and emergency services areas of the budget. We are only highlighting the implementation status of the major augmentations in this section.

Homeless Housing, Assistance and Prevention Program (HHAPP)

Flexible Aid to Local Entities. Since 2019‑20, the budget has authorized $2.95 billion General Fund in flexible aid to large cities (populations over 300,000), counties, Continuums of Care (CoCs)—local entities that administer housing assistance programs within a particular area, often a county or group of counties—and more recently to tribal governments through HHAPP to fund a variety of programs and services that address homelessness. Eligible uses include rapid rehousing, operating subsidies for existing supportive housing units, street outreach, service coordination, and permanent housing. Allocations to local entities generally are based on the local entity’s share of the homeless population.

Budget‑related legislation has modified some HHAPP program features over time. Most significantly, the program has evolved to encourage coordination among local entities to address homelessness in their region and require local action plans that will facilitate assessing program performance and conducting oversight. Figure 5 provides an overview of each round of authorized HHAPP funding. (The state also provided $500 million in flexible homelessness aid to large cities [populations over 330,000] and CoCs on a one‑time basis in 2018‑19 through the Homeless Emergency Aid Program [HEAP].)

Figure 5

Overview of The Homeless Housing, Assistance and Prevention Program (HHAPP)

(In Millions)

|

2019‑20 HHAPP |

2020‑21 HHAPP |

2021‑22 HHAPP |

2022‑23a HHAPP |

|

|

Grant Funding |

||||

|

Citiesb |

$285 |

$130 |

$336 |

$336 |

|

Counties |

175 |

80 |

224 |

224 |

|

CoCs |

190 |

90 |

240 |

240 |

|

Tribal Governments |

— |

— |

20 |

20 |

|

Bonusc |

— |

— |

180 |

180 |

|

Totals |

$650 |

$300 |

$1,000 |

$1,000 |

|

Youth Set Aside |

8 percent of allocation. |

8 percent of allocation. |

10 percent of allocation. |

10 percent of allocation. |

|

Fund Disbursement |

Disbursed spring 2020. |

Disbursed fall 2021. |

Anticipated initial disbursement spring 2022. |

Anticipated initial disbursement spring 2023. |

|

Status |

Recipients managing allocated funds per program requirements and developing annual reports, as needed. |

Recipients managing allocated funds per program requirements and developing annual reports, as needed. |

Applicants engaging with Cal ICH on their local action plan and outcome goals before submitting a complete application, which is due June 30, 2022. |

Application anticipated to be released September 30, 2022. |

|

Expenditure Deadline |

June 30, 2025 |

June 30, 2026 |

June 30, 2026 |

June 30, 2027 |

|

Reporting Requirements |

Annual progress report due December 31. Final report due December 31, 2025. |

Annual progress report due December 31. Final report due December 31, 2026. |

Annual progress report due December 31. Final report due October 1, 2026. |

Annual progress report due December 31. Final report due October 1, 2027. |

|

aThe 2021‑22 budget authorized an additional $1 billion allocation in 2023‑24. The prior rounds of HHAPP allocated funding on a one‑time basis. bGenerally, funding is available for cities with populations over 300,000. However, HHAAP Round 1 also includes a $10 million allocation to Palm Springs. cPotential “bonus” disbursement available dependent on meeting performance conditions. Amount will vary depending on number of eligible recipients. |

||||

|

CoCs = Continuums of Care and Cal ICH = California Interagency Council on Homelessness. |

||||

Initial Findings From 2020 Annual Progress Report: HHAPP Round 1. The 2020 annual progress report for HHAPP Round 1 was published by HCFC in February 2021.

- Actual Awards. Eligible local entities had the option to apply jointly and redirect their HHAPP allocation to another eligible entity in their region. In total, $618 million was allocated to 102 local entities—14 large cities, 49 counties, and 39 CoCs. The remaining $32 million supports program administration and a technical assistance program to support grantees. Of the $618 million, cities received $271 million, counties received $179 million, and CoCs received $168 million.

- Obligated and Expended Funds. As of the February 2021 report, HHAPP grantees obligated 54 percent ($334 million) of awarded funds and expended 10 percent ($61 million) of their funding. Of the funds that have already been obligated, the funding mostly was dedicated towards implementing new navigation centers, emergency shelters, and permanent housing. Of the funds that have already been expended, the funding has mostly been directed towards providing new navigation centers with wraparound services and emergency shelters.

- Service Delivery. From spring 2020, when funds were disbursed, through September 2020, HHAPP funds served approximately 4,600 people—64 percent by CoCs, 17 percent by counties, and 19 percent by cities. Additionally, 41 percent of people served were chronically homeless. Services provided could range from offering information to a person experiencing homelessness to transitioning a person into permanent housing.

- Initial Outcomes. The main outcome in the report is related to the destination of people after they exited HHAPP‑funded projects. There were 2,000 recorded exits from HHAPP‑funded projects. Exits to unsheltered homelessness accounted for 26 percent (530 people) of all exits types reported. Exits to permanent housing destinations accounted for 22 percent (457 people) of all exits. People also exited to temporary living situations (18 percent, or 375 people). A large portion of individuals served in HHAPP‑funded projects exited to unknown destinations (18 percent, or 359 people). Finally, institutional settings (4 percent or 88 people) and other destinations (12 percent, or 246 people) accounted for the remaining reported exists.

The 2021 annual progress report, which would provide updates on HHAPP Round 1 and Round 2, is not yet available. As shown in Figure 5, while the allocation methodology was the same for HHAPP Round 1 and Round 2, the total allocation amount for Round 2 was less than half the amount available in Round 1.

Project Roomkey

Emergence of COVID‑19 Significantly Altered State’s Response to Homelessness. In March 2020, the state had authorized $1.15 billion in flexible aid to local entities (through HEAP and HHAPP Round 1). However, the state modified its approach as part of an amendment to the 2019‑20 budget following the emergence of COVID‑19 given the immediate need to prevent the spread of COVID‑19 among people experiencing homelessness and at risk of homelessness.

Emergency Action Established Project Roomkey to Address Immediate Housing Needs During Pandemic. At the outset of the COVID‑19 public health emergency, the state provided $50 million General Fund (later offset by federal funds) for the newly established Project Roomkey administered by the Department of Social Services (DSS). The program helped local governments lease hotels and motels to provide immediate housing to vulnerable individuals experiencing homelessness that were at risk of contracting COVID‑19. The goal of this effort was to provide non‑congregate shelter options for people experiencing homelessness, to protect public health, and to minimize strain on the state’s health care system. In November 2020, the state authorized an additional $62 million in one‑time funding from its Disaster Response‑Emergency Operations Account to continue operating the program while transitioning people to permanent housing. Project Roomkey was intended to provide temporary, emergency shelter options while also serving as a pathway to permanent housing. Accordingly, the 2021‑22 budget provided $150 million one‑time General Fund to support transitioning Project Roomkey participants into permanent housing.

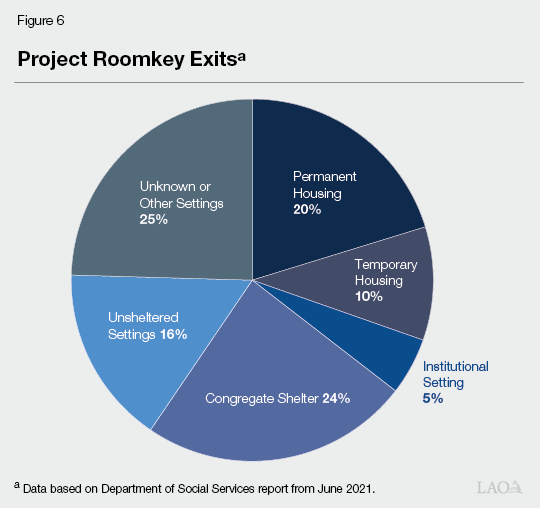

Preliminary Outcomes and Current Status. At the height of the program in August 2020, 16,400 rooms were secured statewide by Project Roomkey and 12,000 were occupied. Overall, the program has provided short‑term housing for over 50,000 people in 55 counties and five tribal entities. As the program is winding down there are about 10,500 rooms secured statewide, and about 62 percent are occupied. Of the 37 counties that continue to have rooms secured through Roomkey, 12 counties have occupancy rates between 90 and 100 percent, 8 counties have occupancy rates between 70 and 80 percent, and Los Angeles has an occupancy rate of 40 percent. Figure 6 shows preliminary data from a June 2021 report on the experience of Roomkey participants upon exiting the program. Today DSS is currently in the process of working with all Project Roomkey grantees to develop and execute local rehousing plans. The administration indicates that the time line for completing these transition plans varies by community.

Homekey Program

2020‑21 Budget Established Homekey Program. Building off of Project Roomkey, the 2020‑21 budget and subsequent action allocated $800 million in one‑time funding for the newly established Homekey Program. The program provides for the acquisition of hotels, motels, residential care facilities, and other facilities that can be converted and rehabilitated to provide permanent housing for persons experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness, and who also are impacted by COVID‑19. Homekey provides grants to local entities to acquire these properties, which are owned and operated at the local level. To promote equitable access to Homekey funding, the program divided the state into eight regions and reserved funding for applicants in each region during the initial priority application period. Each region’s share of the Homekey funding was based on its statewide share of (1) persons experiencing homelessness and (2) low‑income renter households that are rent burdened. The program also provides some exemptions to the California Environmental Quality Act and local zoning restrictions to expedite the acquisition of Homekey sites. Unlike Project Roomkey, this program is administered by the Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD).

2021‑22 Budget Provided Significant Additional Funding for Homekey Program. The 2021‑22 budget provided HCD $2.75 billion ($1.45 billion in 2021‑22 and $1.3 billion in 2022‑23) to fund additional Homekey projects that can be converted and rehabilitated to provide permanent housing for persons experiencing homelessness and who are also at risk of COVID‑19 or other communicable diseases. Most of the funding is federal, however the state also provided General Fund—$250 million in 2021‑22 and $300 million in 2022‑23—to support initial operating subsidies. Recipients have until June 30, 2026 to expend the General Fund portion. Within the total allocation, there is an 8 percent set‑aside for programs serving youth. Applications for funds are accepted from local governmental entities and tribal governments on a continuous basis. HCD began accepting applications in September 2021. Between September 2021 and January 2022, the program maintained the eight geographic region structure for initial prioritization of funding. Beginning in February 2022, applications will be considered on a case‑by‑case basis without regard to the regions. Additionally, the Homekey Program requires full occupancy—defined as no more than a 10 percent vacancy rate—within 90 days of completing construction and/or rehabilitation. For interim housing projects, the program requires an affordability restriction on the units for 15 years, while a 55 years affordability restriction is required for permanent housing projects. The administration estimates this funding will support the creation of 14,000 housing units. Figure 7 provides an overview of Homekey Program funding. Figure 8 provides a full breakdown of the set‑asides in the 2021‑22 funding.

Figure 7

Homekey Program Overview

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Amounta |

Awarded |

Units |

|

|

2020‑21 |

$800 |

94 |

5,900 |

|

2021‑22b |

1,450 |

14 |

1,200 |

|

2022‑23c |

1,300 |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$3,550 |

108 |

7,100 |

|

aAll fund sources. bApplications are still being accepted, so far $323 million has been awarded. cThe 2021‑22 budget authorized an additional $1.3 billion allocation in 2022‑23. |

|||

Figure 8

Homekey Program Funding Categoriesa

(In Millions)

|

Category |

2021‑22b |

|

Geographic Allocation |

$952 |

|

Discretionary Reserve (20 Percent) |

238 |

|

State Administrative (5 percent) |

72 |

|

Tribal Set‑Aside (5 percent) |

72 |

|

Homeless Youth Set‑Aside (8 percent) |

116 |

|

Total 2022‑23 Allocation |

$1,450 |

|

aAll fund sources. bFunding categories for the 2022‑23 appropriation are not available. However, state law requires an 8 percent homeless youth set‑aside. |

|

Preliminary Outcomes and Current Status. The 2020‑21 funding has been fully disbursed through 94 awards to 51 local entities and supported the creation of nearly 6,000 units. Figure 9 provides information about the distribution of funding across the state and units created. Additionally, 91 percent of funds were spent on rehabilitation and acquisition of motels and hotels; 7 percent of funds were spent on acquisition of other types of sites; and 2 percent of funds were spent on other eligible categories, including master leasing, conversion from nonresidential to residential purposes, purchase of affordable covenants, and relocation costs. For the 2021‑22 funds, HCD continues to accept applications and make awards. So far, over 40 applications have requested about $1 billion in Homekey funding and 14 projects have been awarded funding.

Figure 9

Homekey Program 2020‑21 Awards

(In Millions)

|

Regions |

Funding |

Units Created |

|

Los Angeles County |

$268 |

1,814 |

|

Bay Area |

275 |

1,627 |

|

San Joaquin Valley |

63 |

765 |

|

Southern California |

66 |

592 |

|

San Diego County |

38 |

332 |

|

Sacramento Area |

39 |

331 |

|

Balance of State |

26 |

233 |

|

Central Coast |

23 |

217 |

|

Totals |

$798 |

5,911 |

Encampment Resolution Program

Encampment Resolution Efforts. The 2021‑22 budget provided Cal ICH $50 million one‑time General Fund to establish a competitive grant program for cities, counties, and CoCs to support encampment resolution. Specifically, the program is intended to fund local demonstration projects that (1) address the immediate crisis of experiencing unsheltered homelessness in encampments, (2) position people living in encampments onto paths to safe and stable housing, and (3) result in sustainable restoration of public spaces to their intended uses. This program is established in recognition of a need to develop effective, scalable, and replicable strategies that meet the specific, complex needs of individuals living in encampments. The program received nearly 40 applications requesting $120 million in resources. As Cal ICH reviews applications, their scoring system prioritizes funding for applications that (1) demonstrate a commitment to collaborate with local and state partners to resolve encampment issues; (2) address encampments with 50 or more occupants; and (3) reflect a diverse range of communities across the state, including rural, urban, and suburban communities. Cal ICH is expected to provide award notifications in February 2022.

Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program

2021‑22 Budget Established Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program (BH‑CIP). The 2021‑22 budget package included $755.7 million in 2021‑22, $1.4 billion in 2022‑23, and $2.1 million in 2023‑24 to establish BH‑CIP. Under this program, the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) provides competitive grants to local entities to increase behavioral health infrastructure, predominantly by constructing, acquiring, or renovating facilities for community behavioral health services (contingent on these local entities providing matching funds and committing to providing funding for ongoing services). Grants provided under this program fund a variety of community behavioral health facility types to treat individuals with varying levels of behavioral health needs. For example, funds could be used on (1) short‑term crisis treatment beds, (2) residential treatment facilities in which treatment typically lasts for a few months, or (3) longer‑term rehabilitative facilities. Certain portions of the total amounts discussed above for this program are set aside for more specific purposes or targeted at more specific populations. Specifically, funding is reserved for the establishment of mobile behavioral health crisis teams and for community behavioral health facilities targeted at children and youth. Although the administration indicates that BH‑CIP could support people experiencing homelessness with behavioral health conditions, the funding is not limited to this population, nor is there an established set‑aside or strategy to target people experiencing homelessness.

Since Approval, DHCS Has Developed Funding Plan and Key Program Details. When BH‑CIP was approved, several key implementation details were not fully developed yet. These outstanding details concerned (1) the funding plan, (2) what requirements local entities would need to meet to apply for and obtain funds, and (3) what the ultimate match requirement from local entities would be. Below, we discuss recent developments related to these key program details.

- Funding Plan. DHCS intends to make BH‑CIP grant funds available through six rounds. Under this schedule, funding through rounds one and two were made available in 2021 and some awards were made. Round one ($150 million) is focused on mobile crisis infrastructure and round two ($16 million) is focused on local planning activities. DHCS has awarded $138.8 million through round one and $1.5 million through round two so far. For the later rounds, round three ($518.5 million) would be focused on launch ready projects, round four ($480.5 million) would be focused on children and youth facilities, and rounds five and six ($960 million combined) would be focused on priorities identified in a recently released DHCS analysis that examined the current capacity and statewide need for behavioral health services. Notably, this funding plan results in shifts in the estimated payment timing for BH‑CIP, such that less funding than anticipated will be distributed in 2021‑22 and more than anticipated will be distributed in 2022‑23. In addition, DHCS intends to apply a cap to most BH‑CIP funding for different regions of the state. (These caps would be determined by these regions’ share of 2011 realignment funds for behavioral health.) However, DHCS will reserve a small amount (not subject this cap) to distribute at its discretion depending on what statewide demand ultimately is.

- Local Application Requirements. In order to obtain BH‑CIP funding, local entities will be required to participate in a pre‑application consultation on project readiness requirements. Following this, when applying for funds, local entities will be required to submit documentation of (1) control over the property to be acquired or rehabilitated, (2) approval for any necessary local permits, (3) adherence to behavioral health facility licensing requirements, (4) preliminary construction plans and time lines, (4) capacity to meet the local match requirement (further discussed below), and (5) engagement with the local community (including any necessary contracts to ensure that Medi‑Cal services are provided in facilities proposed for acquisition or construction). Local entities also will be required to share results from local behavioral health needs assessments (which inform which facility types they will prioritize) and how they intend for projects to advance racial equity.

- Local Match Requirement. The amounts that local entities will be required to provide as the match for BH‑CIP funding vary by applicant type. Specifically, (1) tribal entities will be required to provide 5 percent in matching funds; (2) counties, cities, and nonprofits will be required to provide 10 percent in matching funds; and (3) for‑profit or private organizations will be required to provide 25 percent in matching funds. In addition, under BH‑CIP, the local match can be provided in the form of cash or in‑kind contributions (such as land or existing structures) subject to approval from the state.

Community Care Expansion Program

Community Care Expansion (CCE) Program Implementation Update. DSS received $805 million—$450 million federal American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) of 2021 funds, $53 million Home‑ and Community‑Based Services ARPA Fund, and $302 General Fund—in 2021‑22 to administer the CCE program. The program aims to expand and preserve residential facilities serving vulnerable adults and seniors—such as DSS‑licensed adult residential facilities and residential care facilities for the elderly. Facilities prioritized for funding will be those serving adults and seniors receiving Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment (SSI/SSP) or Cash Assistance Program for Immigrants (CAPI) benefits, and/or at risk of or experiencing homelessness. CCE funding has not yet been allocated. DSS indicated that a joint request for applications (RFA) portal for CCE capital expansion projects and BH‑CIP shovel‑ready projects will be launched February 15 for counties, cities, tribes, non‑profits, and for‑profit organizations. Applications will be assessed along a number of criteria, including: efforts to advance racial equity, financial viability, long‑term operational sustainability, and comprehensive use of resources to serve the target population. Applications will be reviewed on a rolling basis, with funding disbursed on a per‑project basis as applications are approved until funds are exhausted.

Leading up to the release of the RFA, the administration has made a number of implementation decisions for the program:

- Funding Division. Of the total funds, 75 percent will be available for capital expansion projects to acquire, construct, and rehabilitate facilities. The remaining 25 percent will be available (through a noncompetitive allocation to counties and tribes, separate from the RFA) to preserve facilities that serve the prioritized populations. The preservation funding will include $55 million for a capitalized operating subsidy reserve—for facilities running operating deficits—for use up to five years.

- Regional Approach With Set‑Asides. DSS defined seven CCE funding regions, with regional allocations to be determined by factors such as distribution of adult and senior care facilities, homelessness counts, and development costs. DSS also determined a few funding set‑asides, such as 5 percent for tribes and 8 percent for small counties.

- Matching Funds. Applicants will be required to provide matching funds, with the match rate varying by the type of applicant (for example, a 10 percent match will be required for counties and cities, and a 5 percent match for tribes).

- Intersection With Behavioral Health Infrastructure Program. DSS has been collaborating with DHCS to coordinate the departments’ work across CCE and BH‑CIP. The departments have contracted with an external consulting and research firm to serve as the administration entity for CCE and BH‑CIP. This contractor will provide pre‑application technical assistance and consultations to all program applicants beginning in January 2022, and will provide ongoing training and assistance throughout the duration of both projects. Where possible, applicants will be encouraged to leverage funding from both CCE and BH‑CIP—as well as other sources—to deliver more comprehensive residential and behavioral health services to eligible populations.

Homelessness Landscape Assessment

Homelessness Assessment and Data System. The 2021‑22 budget provided $5.6 million one‑time General Fund for Cal ICH to contract with a vendor to conduct an analysis of homelessness service providers and programs at the local and state level. A statutorily mandated interim report is due to the Legislature July 1, 2022 and a final assessment is due by December 31, 2022. In addition, the budget provided $4 million one‑time General Fund to support further development of HDIS, which would allow the state to access and compile more standardized data collected by CoCs. While the HDIS system is now operational, Cal ICH indicates they will spend the first half of 2022 working to establish systemwide performance measures that will help the state and local jurisdictions better assess their progress toward preventing, reducing, and ending homelessness. Once these performances measures are finalized, Cal ICH anticipates updating the HDIS system to focus more on the outcomes of people accessing services throughout California.

Governor’s 2022‑23 Homelessness Proposals

Homelessness Package Proposes to Focuses on Near‑Team Needs. The Governor proposes $2 billion one‑time General Fund over two years that is intended to address near‑term homelessness needs while previously authorized funds for long‑term housing solutions are implemented. Below, we describe the two major homelessness proposals.

Behavioral Health Bridge Housing

Proposes Bridge Funding for Behavioral Health Housing. The budget proposes $1 billion General Fund in 2022‑23 and $500 million General Fund in 2023‑24 to address the immediate housing and treatment needs of people with complex behavioral health conditions. The funding would be administered by DHCS through the Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program established in the 2021‑22 budget. While key details are forthcoming, the administration indicates funds could be used differently than the existing program structure. For instance, funds could be used to purchase and install tiny homes and to provide time‑limited operational supports in these tiny homes or in other housing settings, including existing assisted living settings. This funding is intended to serve as a “bridge” resource until the long‑term housing and treatment solutions for people with serious behavioral health conditions authorized as part of the 2021‑22 budget come online.

Encampment Resolution Grants Program

Significantly Augments Funding for Encampment Resolution Program. The Governor proposes $500 million one‑time General Fund in 2022‑23 for the Encampment Resolution Grants Program administered by Cal ICH. This is a ten‑fold expansion of the current Encampment Resolution Grant Program. The program would require quarterly fiscal reports and annual programmatic outcomes reports from all funding recipients. Cal ICH anticipates collecting information emerging from the grantees across the state to identify, disseminate, and coordinate resources and services to prevent and end unsheltered homelessness in collaboration with other state agencies. Recently released budget‑related legislation provides additional details about how the proposal would be implemented. We are reviewing the proposed legislation.

LAO Comments

Devote Attention to Overseeing Recent Augmentations. We suggest the Legislature dedicate the early part of the budget process to overseeing the implementation of last year’s significant homelessness augmentations. In our examination of recent investments, described above, we have learned about the status of funding disbursements, when unawarded funds are anticipated to be released, and have an initial understanding about where resources are being allocated and for what purposes. However, there is more to learn as the Legislature conducts oversight of these programs, assesses their performance, and identifies opportunities to improve their operation. For instance, what were the challenges and successes in standing up these programs; are there local capacity constraints that are limiting the effectiveness of these programs; and are state, local, and regional entities coordinating effectively? Prior to authorizing increased funding for the activities proposed in the 2022‑23 budget, ensuring that the homelessness efforts authorized in prior budgets are operating effectively, adequately supported, and can be maintained over time will be important. For instance, we have raised whether local governments need additional support to establish services and supports for Homekey properties, especially over the long term. Additionally, is the state actively disseminating best practices related to homelessness response and providing robust technical assistance to best position local entities for success? Is Cal ICH positioned and supported to effectively oversee the homelessness‑related programs administered across the many state entities administering them? In parallel with overseeing recent efforts, we suggest the Legislature consider the role of the state—in partnership with locals—in addressing homelessness going forward. Ultimately, assessing the performance of current programs and determining the nature of the state‑local relationship going forward could inform the Legislature’s budget decisions in 2022‑23.

Consider Long‑Term Approach for Ongoing Homelessness Efforts. The scale of the homelessness crisis in California is significant. Addressing this crisis requires a complex combination of services and infrastructure. As more information about recent state efforts becomes available, we suggest the Legislature assess which types of interventions appear most effective. This information could help guide the state’s long‑term fiscal and policy role in addressing homelessness. For instance, if Homekey were determined to be an effective state‑level intervention, the Legislature could consider establishing an infrastructure fund to support the purchase and rehabilitation of facilities over many years.

State Appropriations Limit (SAL) Considerations. The SAL constrains how the Legislature can spend revenues that exceed a specific threshold. Given recent revenue growth, the SAL has become an important consideration in the state budget process and will continue to constrain the Legislature’s choices in this year’s budget process. However, certain types of spending, like some funding for capital outlay, are excluded from this limit. Some prior homelessness funding—such as General Fund spending on the Homekey Program—has met the SAL definition of capital outlay and has been excluded from the limit. As the Legislature crafts its homelessness package, allocating funding to homelessness programs excluded from the SAL could allow the state to allocate more funds to those programs than it otherwise could.

For Any Authorized Funds, Set Clear Expectations and Establish Metrics to Assess Performance. We recommend the Legislature consider how the state would coordinate work related to these new proposals across programs and departments. Setting clear expectations through statute and establishing reporting requirements to facilitate oversight over the state’s progress towards addressing homelessness will be critical. Forthcoming information from the Homelessness Landscape Assessments and improvements to HDIS could help the Legislature make better‑informed budget decisions in future fiscal years and exercise stronger oversight over budget actions.

Specific Considerations for 2022‑23 Budget Proposals

How Has the Administration Assessed the Level of Need for Encampment Resolutions? While requests for encampment resolution funding in 2021‑22 exceeded availability by $70 million, the Governor’s proposal goes far beyond funding these original requests. The state’s ability to spend the major proposed augmentation is unclear. Understanding how recently introduced legislation may expand the scope of allowable usages of the funds will be important. Additionally, the 2021‑22 funding was intended to fund demonstration projects which would inform best practices for addressing the needs of people living in unsheltered encampments, while simultaneously addressing the health and safety needs of the entire community. The administration is proposing an augmentation on many orders of magnitude above what has been previously authorized for the program before the initial funding is released and the performance of the program can be assessed. As a result, how successful interventions will be identified for this round of funding is unclear.

Bridge Funding May Make Sense but Forthcoming Details Will Be Important. The Governor indicates the homelessness funding proposed in the 2022‑23 budget is intended to address near‑term needs while previously funded long‑term housing solutions come online. We suggest the Legislature consider the trade‑offs between pursuing the bridge proposal, given the time and resources required to implement a new program of this scale and supporting existing services and programs. Specifically, the Legislature could consider where existing programs could be leveraged to provide immediate housing support for people with behavioral health needs experiencing homelessness. While some bridge resources may be necessary, whether the short‑term options proposed by the administration are most effective, especially in the context of what the state already has invested towards housing and homelessness infrastructure, is unclear. For example, could an expanded Project Roomkey address the immediate need identified by the Governor? Alternatively, would additional funding for CCE provide both immediate and longer‑term solutions? Some key questions to consider about the current proposal include: (1) what would happen to resources once permanent housing comes online, (2) how quickly can the bridge‑funded units be up and running, (3) how does the timing align with the anticipated schedule for more permanent options, (4) does the proposed bridge housing solution make sense for individuals with behavioral health conditions, and (5) how would the funding support transitioning individuals into permanent housing? Finally, the focus of the proposal—whether for behavioral health or broader homelessness‑related services—should determine which state entity should oversee the program. Currently, many state entities are tasked with different homelessness responsibilities, so ensuring programs are properly suited to a department’s mission is important.

Conclusion

California has made notable progress in its engagement and development of partnerships with local governments since 2018‑19 when the state began taking a more active role in addressing homelessness. Overall, the state has increased its role in addressing homelessness by providing significant, albeit one‑time and temporary, funding towards infrastructure and flexible aid to local governments in recent years. Despite this progress, the scale of the homelessness crisis in California is significant and continued work and resources will be necessary to address the state’s homelessness challenges. We suggest the Legislature dedicate the early part of the budget process to overseeing the implementation of last year’s significant homelessness augmentations. Additionally, the state authorized significant funding last year for programs the Governor now proposes for additional augmentation. In both cases, it is too early to know how these programs have performed. As the Legislature moves forward in its efforts to address homelessness, we suggest considering how to balance the state‑local relationship and identify a predictable funding strategy that aligns with the balance of responsibilities between the state and local governments.