LAO Contact

February 14, 2022

The 2022‑23 Budget

The Governor’s Housing Plan

Summary

Housing Affordability Is a Serious and Widespread Challenge in California. Californians spend a larger share of their income on rent than households in the rest of the nation at every income quartile. Households with the lowest income face the highest cost pressures.

Building Less Housing Than People Demand Drives High Housing Costs. While many factors have a role in driving California’s high housing costs, the most important is the significant shortage of housing, particularly within urban coastal communities.

Recent Housing‑Related Spending. Recent budget actions reflect the increased role of the state in helping spur housing development. The state budget provided nearly $5 billion in 2021‑22 for housing‑related programs.

Legislature Has Adopted Major Housing Legislation. While fiscal actions to address affordability are one critical element of addressing California’s housing challenges, perhaps more important are policy solutions pursued by the Legislature to increase the supply of housing, which can address housing affordability. In recent years, legislation has continued to make headway in helping to facilitate housing development in the state.

Housing Budget Package. The Governor’s 2022‑23 budget proposes $2 billion General Fund one time for several major housing proposals, largely reflecting expansions of existing programs.

LAO Comments. We raise the following issues for the Legislature’s consideration.

- We suggest the Legislature devote attention to overseeing recent augmentations.

- The Governor’s interest in aligning housing and climate goals is meritorious, but more concerted efforts will be necessary over the long term to build new, and protect existing, housing from the impacts of climate change.

- Assess how the Governor’s housing package moves the state towards meeting goals set out in recent policy changes.

- Consider evaluating distribution of housing development to ensure equitable support.

- The state’s capacity to fully utilize proposed funding is unclear.

- Consider the state’s long‑term fiscal strategy in addressing housing development and affordability.

- When crafting a housing package, consider the state appropriations limit.

- For any authorized funds, set clear expectations and establish metrics to assess performance.

Background

Housing Affordability Is a Serious and Widespread Challenge in California. Californians spend a larger share of their income on rent than households in the rest of the nation at every income quartile. Households with the lowest income face the highest cost pressures. In California, around 2.5 million low‑income households are cost burdened (spending more than 30 percent of their incomes on housing). Over 1.5 million low‑income renters face even more dire cost pressures—spending more than half of their income on housing. Housing affordability challenges even middle‑income households. About 900,000 households at or above the California median income (households earning above $80,000 annually) in the state are cost burdened (representing 15 percent of households). High housing costs drive California’s official poverty rate from 11 percent (about the national average) to 15 percent (only the District of Columbia has a higher rate) under the Census Bureau’s Supplemental Poverty Measure, which considers food, clothing, shelter, and utilities. Additionally, housing prices have increased rapidly during the COVID‑19 pandemic. While we do not know what effect the pandemic will have on housing in the long term, we know the pandemic has made the housing problem more acute in the near term.

Building Less Housing Than People Demand Drives High Housing Costs. While many factors have a role in driving California’s high housing costs, the most important is the significant shortage of housing, particularly within urban coastal communities. A shortage of housing along California’s coast means households wishing to live there compete for limited housing. This competition increases home prices and rents. Some people who find California’s coast unaffordable turn instead to California’s inland communities, causing prices there to rise as well. This dynamic can result in longer commutes, which in turn can contribute to increased greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and climate change. Moreover, because some degree of climate change already is occurring and more changes are inevitable, climate change will affect demand for housing in certain communities. For example, wildfire risk or seal‑level rise may decrease demand for housing in some communities and push demand elsewhere. Today, an average California home costs 2.3 times the national average. California’s average monthly rent is about 50 percent higher than the rest of the country. Though the exact number of new housing units California needs to build to address housing affordability is uncertain, the state would need to annually build roughly twice as much housing as it does today so that housing costs in California increase at the same rate as housing costs nationally.

Actions to Address Affordability. Historically, federal, state, and local governments have implemented a variety of programs aimed at helping Californians, particularly low‑income Californians, afford housing. These programs generally work in one of three ways: (1) increasing the supply of moderately priced housing, (2) paying a portion of households’ rent costs, or (3) limiting the prices and rents property owners may charge for housing. As the housing affordability crisis has become more acute over time, the state has significantly increased its fiscal role by largely expanding existing programs and establishing some new programs that help subsidize housing development at the local level. While affordable housing programs are important, these programs help only a small fraction of the Californians that are struggling to cope with the state’s high housing costs. Expanding existing housing programs to fully address needs would require a significant expansion of existing state programs and necessitate funding increases orders of magnitude larger than existing program funding.

Legislature Has Adopted Major Housing Legislation. While fiscal actions to address affordability are one critical element of addressing California’s housing challenges, perhaps more important are policy solutions pursued by the Legislature to increase the supply of housing, which can address housing affordability. In 2017, the Legislature passed a package of 15 bills aimed at addressing the high cost of housing in California, including streamlining approval processes, creating and preserving affordable housing, and strengthening accountability and enforcement of housing laws. In subsequent years, additional legislation has continued to make headway in helping to facilitate housing development in the state. Most recently, in the 2021 legislative session, the Governor signed over 30 bills related to streamlining home building, addressing barriers to building affordable housing, addressing systemic bias by elevating fair housing principles, and strengthening local government accountability.

Recent Housing‑Related Spending. Recent budget actions reflect the increased role of the state in helping spur housing development. Figure 1 summarizes major recent housing spending actions.

Figure 1

Major Recent State Housing Spending

(In Millions)

|

Program |

Amounta |

Funding Type |

State Administrator |

|

2019‑20 |

|||

|

State Low Income Housing Tax Credits |

$500 |

One‑time |

CTCAC |

|

Mixed‑Income Program |

200 |

Temporary |

CalHFA |

|

Infill Infrastructure Grant Program |

300 |

One‑time |

HCD |

|

Planning Grants to Local Governments |

250 |

One‑time |

HCD |

|

Total |

$1,250 |

||

|

2020‑21 |

|||

|

State Low Income Housing Tax Credits |

$500 |

One‑time |

CTCAC |

|

National Mortgage Settlement |

331 |

One‑time |

CalHFA, Judicial Branch |

|

Mixed‑Income Program |

50 |

Temporary |

CalHFA |

|

Total |

$881 |

||

|

2021‑22 |

|||

|

Affordable Housing Backlog |

$1,750 |

One‑time |

HCD |

|

Regional Planning Grants |

600 |

One‑time |

HCD |

|

State Low Income Housing Tax Credits |

500 |

One‑time |

CTCAC |

|

Foreclosure Prevention and Preservation Program |

500 |

One‑time |

HCD |

|

Student Housing and Campus Expansion |

500 |

Temporaryb |

CCC, CSU, UC |

|

Affordable Housing Preservation |

300 |

One‑time |

HCD |

|

Infill Infrastructure Grant Programc |

250 |

One‑time |

HCD |

|

Homebuyer Assistance |

100 |

One‑time |

CalHFA |

|

Accessory Dwelling Unit Financing |

81 |

One‑time |

CalHFA |

|

Farmworker Housing |

50 |

One‑time |

HCD |

|

Golden State Acquisition Fund |

50 |

One‑time |

HCD |

|

Mixed‑Income Program |

45 |

One‑time |

CalHFA |

|

Scaling Excess Lands Development |

45 |

One‑time |

HCD |

|

Legal Assistance for Renters |

40 |

Temporaryd |

Judicial Branch |

|

Total |

$4,811 |

||

|

aAll fund sources. bThe budget also authorized $750 million in 2022‑23 and $750 million in 2023‑24 for student housing and campus extension. cThe budget also reallocates $284 million in remaining Proposition 1 (2018) funds for the Infill Infrastructure Grant Program. dThe budget also authorized $20 million in 2022‑23 and $20 million in 2023‑24 for legal assistance for renters. |

|||

|

CTCAC = California Tax Credit Allocation Committee; CalHFA = California Housing and Finance Agency; and HCD = Housing and Community Development. |

|||

Summary of Major Housing Proposals. The Governor’s 2022‑23 budget proposes $2 billion General Fund one time for several major housing proposals, largely reflecting expansions of existing programs. Figure 2 provides an overview of the housing budget proposals.

Figure 2

Major 2022‑23 Housing Budget Proposals

(In Millions)

|

Proposal |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

Fund |

State |

|

Housing Development |

||||

|

Infill Infrastructure Grant Program |

$225 |

$275 |

General Fund |

HCD |

|

Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities Program |

75 |

225 |

General Fund |

HCD |

|

State Excess Sites |

25 |

75 |

General Fund |

HCD |

|

Adaptive Reuse |

50 |

50 |

General Fund |

HCD |

|

Affordable Housing |

||||

|

State Low Income Housing Tax Credits |

$500 |

— |

General Fund |

CTCAC |

|

Mixed‑Income Program |

50 |

$150 |

General Fund |

CalHFA |

|

Portfolio Reinvestment Program |

50 |

150 |

General Fund |

HCD |

|

Mobilehome Park Rehabilitation and Resident Ownership Program |

25 |

75 |

General Fund |

HCD |

|

HCD = Housing and Community Development; CTCAC = California Tax Credit Allocation Committee; and CalHFA = California Housing and Finance Agency. |

||||

Below, we provide an update on some major recent state budget actions related to housing, describe the Governor’s budget proposals, and raise issues for the Legislature’s consideration.

Housing Development

Governor’s Housing Development Package Primarily Expands Existing Programs. The Governor proposes $1 billion in one‑time General Fund over two years to expand housing development. The administration notes a climate benefit of these proposals primarily because these programs support more dense housing development, thereby reducing vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and GHG emissions.

Infill Infrastructure Grant Program

Background

Infill Infrastructure Grant (IIG) Program. The IIG Program was created in 2007 within the Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) to provide funding for infrastructure improvements that support higher‑density affordable and mixed‑income housing in locations designated as infill. Under the program, developers and local entities can partner to apply for infrastructure funding, including the development or rehabilitation of parks or open space; water, sewer, or other utility service improvements; streets; roads; sidewalks; and environmental remediation. The funding generally is available through a competitive application process that assesses project readiness, affordability, density, access to transit, proximity to amenities, and consistency with regional plans. Originally, bond funding was provided for the program through the Housing and Emergency Shelter Trust Fund Act of 2006 (Proposition 1C) and the Veterans and Affordable Housing Bond Act of 2018 (Proposition 1).

Recent Budget Actions Allocated General Fund for IIG Program. More recently, the state provided the program General Fund resources. Specifically, the 2019‑20 budget provided $300 million General Fund for the IIG Program. The allocation included a $90 million set aside for small jurisdictions—counties with populations under 250,000 and the cities located within those counties. The 2021‑22 budget provided HCD $250 million one‑time General Fund and maintained the $90 million set aside for small jurisdictions.

Update on IIG Program Spending. The funding provided in 2019‑20 has been fully allocated. The funding for large jurisdictions was oversubscribed by $112 million, while the small jurisdiction allocation was oversubscribed by $6 million. Among large jurisdictions, just over half of available funding was allocated to projects in Northern California, about 45 percent to Southern California, and 2 percent to Central California. Small jurisdictions in Central California received a significantly higher proportion of the small jurisdiction set aside—28 percent, while Northern California received 60 percent and Southern California received 11 percent. The Notice for Funding Availability (NOFA) for the remaining Proposition 1 funding is expected in March 2022, while the NOFA for the 2021‑22 General Fund appropriation is expected in April 2022. Figure 3 provides an update on IIG Program spending since the program was first established.

Figure 3

Infill Infrastructure Grant Program Spending

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Fund Source |

Total |

Remaining |

Next Funding |

Awarded |

Units |

|

Proposition 1C (2006) |

$850 |

— |

N/A |

178 |

24,000 |

|

Proposition 1 (2018) |

300 |

$140 |

March 2022 |

34a |

4,300 |

|

General Fund (2019‑20) |

300b |

— |

N/A |

60 |

6,800 |

|

General Fund (2021‑22) |

250c |

250 |

April 2022 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

a Based on a partial release of available funding. b $90 million set aside for small jurisdictions. c $90 million set aside for small jurisdictions. |

|||||

Governor’s 2022‑23 Budget Proposal

Augments Funding for IIG Program. The budget proposes $225 million General Fund in 2022‑23, and $275 million in 2023‑24, for the IIG Program focused on development in infill areas and locations that facilitate a reduction in VMTs. Unlike the other recent General Fund augmentations for IIG, this proposal does not specify a set aside for small jurisdictions. However, the department would have the authority to identify a percentage of funds in the NOFA targeted to small jurisdictions. Additionally, proposed budget‑related legislation is intended to facilitate program administration. Some existing program rules, such as the definition of a qualifying infill area, vary between the IIG Program of 2007, which apply to the bond‑funded portions of the program and the IIG Program of 2019, which apply to the General Fund portions of the program. The proposed legislation is intended to bring alignment and consistency to the program requirements—making more projects in small jurisdictions eligible. Finally, the program would set aside up to 5 percent of the proposed augmentation for state operations.

- Anticipated Outcomes. HCD estimates this funding would support approximately 108 new projects and support the creation of 13,000 housing units.

- Implementation Plan. For the 2022‑23 augmentation, HCD anticipates releasing the NOFA in January 2023 and announcing awards in June 2023. For the 2023‑24 augmentation, HCD anticipates releasing the NOFA in January 2024 and announcing awards in June 2024.

Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities Program

Background

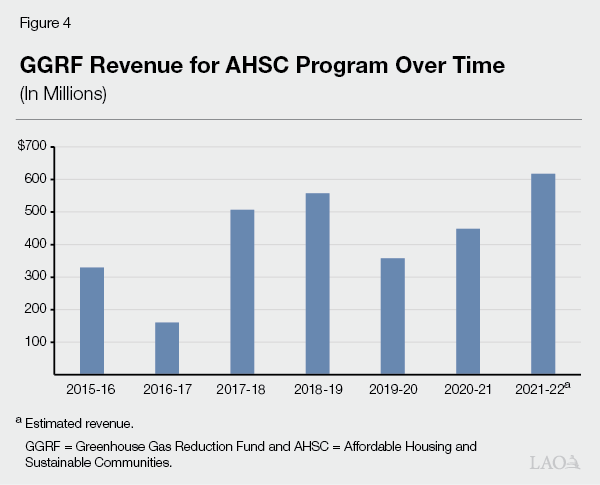

Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities (AHSC) Program. Administered by the Strategic Growth Council and implemented by HCD, the AHSC Program funds land‑use, housing, transportation, and land preservation projects to support infill and dense development that reduces GHG emissions. Therefore, the AHSC Program not only provides funding for the development of affordable housing, it also supports activities that allow residents to more easily move in their community. For example, by supporting dedicated bus lanes or establishing a bike share program. Funding for the AHSC Program is provided from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF), an account established to receive cap‑and‑trade auction proceeds. While factors inherent in the cap‑and‑trade market means there is significant volatility in annual GGRF revenue, AHSC generally receives 20 percent of the proceeds. Figure 4 shows how GGRF revenue allocated towards the AHSC program has changed over time.

Update on AHSC Program Spending. In all, the AHSC Program has allocated nearly $2.5 billion GGRF over six rounds of funding through 2020‑21 and has contributed to the creation of 16,400 housing units. Across all six rounds, the projects are estimated to reduce pollutants in the air equivalent to getting about 90,000 cars off the road for one year. Typically, the program releases a NOFA in October of each year—once proceeds from that year’s cap‑and‑trade auctions are known—applications are accepted through February of each year and awards are announced annually in June.

Governor’s 2022‑23 Budget Proposal

Proposes General Fund for AHSC Program. The budget proposes $75 million General Fund in 2022‑23, and $225 million in 2023‑24, to support land‑use, housing, transportation, and land preservation projects for infill and more compact development that reduces GHG emissions. The continuous appropriation from GGRF for the AHSC Program would not be affected by this proposal.

- Anticipated Outcomes. HCD estimates that this funding would incentivize the creation of 1,600 housing units through projects completed as a result of this proposal—400 housing units due to the 2022‑23 funding and 1,200 housing units due to the 2023‑24 funding.

- Implementation Plan. For the 2022‑23 augmentation, HCD anticipates releasing the NOFA in October 2022 and announcing awards in June 2023. HCD anticipates the same schedule for the 2023‑24 augmentation.

State Excess Sites

Background

Building Affordable Housing on Excess State Property. In 2019‑20, the Governor issued an executive order directing the state to identify excess state properties that are suitable for affordable and mixed‑income housing development. Ultimately, the Governor aimed to solicit affordable housing developers to build demonstration projects on excess state property that use creative and streamlined approaches to building (for example, using modular construction). The administration indicated that this approach was likely to produce housing units more quickly and cost‑efficiently than traditional projects because housing developers would not need up‑front capital to purchase the land and would not need to wait for local review processes.

However, in exploring the feasibility of affordable housing development on state excess sites, HCD and the Department of General Services (DGS) indicate they encountered two recurring problems: (1) lack of funding for environmental assessment and cleanup and (2) lack of financing for affordable housing development. The 2021‑22 budget provided HCD $45 million one‑time American Rescue Plan (ARP) Act fiscal relief funds to expand the state excess sites program with funding for brownfield remediation, and budget‑related legislation to expand the state excess sites program with local government matching grants that aim to incentivize further affordable housing development on excess lands.

Update on State Excess Sites Program. The state’s review of excess properties has resulted in a dynamic list of sites that are suitable for development. So far, 18 sites have been authorized to move forward with development and between 3,800 and 4,500 units of housing are anticipated on these properties. Additionally, 5 to 10 more sites are expected to move forward with development in the current year. Currently, HCD and DGS have identified 125 sites that are suitable and available for development across the state. HCD plans to release the NOFA for $30 million (of the $45 million provided in 2021‑22) in March 2022 and anticipates making awards to facilitate excess site development in June 2022. HCD transferred the remaining $15 million to DGS through an architectural revolving fund in September 2021 for the investigation and remediation of environmental conditions on excess sites.

Governor’s 2022‑23 Budget Proposal

Augments Funding for State Excess Sites Program. The budget proposes $25 million General Fund in 2022‑23, and $75 million in 2023‑24, to expand affordable housing and adaptive reuse opportunities on state excess land sites. Recently released budget‑related legislation would provide additional details about the proposal. We continue to review the legislation.

- Anticipated Outcomes. HCD has not quantified the increase in affordable housing supply this proposal could generate.

- Implementation Plan. HCD has not identified dates for key milestones associated with this proposal but notes general activities they would undertake, such as continued collaboration with DGS and technical assistance to local entities to ensure excess sites are ready for housing development.

Adaptive Reuse

Governor’s 2022‑23 Budget Proposal

Establishes New, Temporary Adaptive Reuse Program. The budget proposes $50 million General Fund in 2022‑23, and $50 million in 2023‑24, for a new adaptive reuse incentive grant program. Adaptive reuse is the process of adapting and rehabilitating unutilized or under‑utilized, generally commercial, buildings for housing. Adaptively repurposing these buildings can entail obstacles that can make it difficult for developers to offer the housing at affordable rents. For example, (1) these types of buildings were built to different code requirements and must be updated to residential building codes; (2) older buildings may need updating to meet seismic standards for residential occupancies, as well as remediating materials that pose environmental hazards, such as asbestos and lead‑based paint; and (3) converting interior spaces of large office buildings or warehouses may be challenging since these areas are not adjacent to windows. According to the administration, the program would prioritize projects located in infill and low‑VMT areas. The administration recently has proposed budget‑related legislation to implement this proposal, we are reviewing the language.

- Anticipated Outcomes. HCD estimates that the funding would be awarded to 20 projects and incentivize the creation of 1,460 to 1,960 housing units in total.

- Implementation Plan. For the 2022‑23 augmentation, HCD plans to offer the funding in conjunction with the upcoming October 2022 AHSC Program NOFA, as this is the department’s next planned release of funding. HCD indicates a strong interest in moving quickly in order to take advantage of opportunities created by commercial property vacancies due to the COVID‑19 pandemic. Awards would be anticipated in the fourth quarter of 2022‑23. If funds were not fully awarded, HCD would release the remaining funds concurrent with the 2022‑23 “SuperNOFA,” with awards anticipated for spring 2023. For the 2023‑24 augmentation, HCD plans to offer the funding in a similar matter—in conjunction with the October 2023 AHSC NOFA and, if funds remained, in the spring SuperNOFA. Awards would be anticipated in late 2023‑24 for AHSC and early in the 2024‑25 for the SuperNOFA.

Affordable Housing

Affordable Housing Package Primarily Expands Existing State Programs. The Governor proposes $1 billion in one‑time General Fund over the next several years for affordable housing development.

State Low Income Housing Tax Credits

Background

State Low‑Income Housing Tax Credit Program. The state Low‑Income Housing Tax Credit Program provides tax credits to builders of rental housing affordable to low‑income households. The program was created to promote private investment in affordable housing for low‑income Californians. The California Tax Credit Allocation Committee (CTCAC) administers the federal and state Low‑Income Housing Tax Credit Programs. The state has historically made about $100 million available annually for this purpose. Since 2019‑20 the budget has authorized consecutive $500 million one‑time expansions of the state Low‑Income Housing Tax Credit Program. This additional tax expenditure brings total credits to $1.5 billion across the past three years. Each of these one‑time expansions of the program have made up to $200 million available for the development of mixed‑income housing.

Update on State Low‑Income Housing Tax Credit Program. CTCAC received 110 applications for the tax credits authorized by the 2019‑20 budget. All of the 2019‑20 tax credits have been allocated. Of the 72 projects that received tax credits, 18 projects shared the $200 million set aside for mixed‑income housing. Collectively, these tax credits have resulted in the new construction of 6,550 low‑income units. The 2021 annual report, which would provide details on the tax credits authorized by the 2020‑21 budget, is not yet available.

Governor’s 2022‑23 Budget Proposal

Continues One‑Time Expansion of State Low Income Housing Tax Credits. In addition to the $100 million annually that the state makes available for housing tax credits, the Governor’s budget proposes $500 million for tax credits to builders of rental housing affordable to low‑income households. This would be the fourth consecutive year in which the Governor has proposed a one‑time expansion of the state’s housing tax credit, for a total of $2 billion in tax credits. As with the prior expansions, up to $200 million would be available for the development of mixed‑income housing projects.

Mixed‑Income Housing

Background

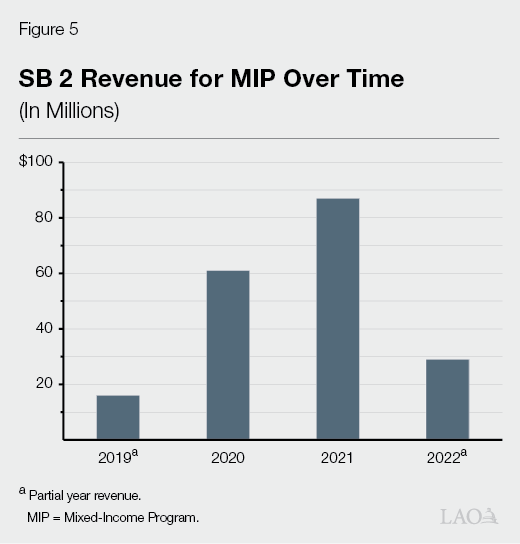

Mixed‑Income Program (MIP). Administered by the California Housing and Finance Agency (CalHFA), MIP provides loans to developers for new mixed‑income rental housing development. Specifically, these developments serve renters with incomes between 30 percent and 80 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI), with an option to serve renters with incomes up to 120 percent of AMI. The program was established in 2019 after Chapter 91 of 2017 (SB 2, Atkins) established an annual appropriation to CalHFA for the purpose of creating mixed‑income multifamily residential housing for lower‑ to moderate‑income households. To fund these efforts, CalHFA receives 15 percent of SB 2 funds. CalHFA expects to have a total of $65 million available for MIP in 2022. In addition to the continuous appropriation from SB 2, recent budget actions have authorized General Fund augmentations for the program. While the 2019‑20 budget provided MIP $500 million General Fund over four years, subsequent budget reversions associated with the COVID‑19 pandemic made only $250 million available to the program over two years. The 2021‑22 budget provided $45 million one‑time General Fund for MIP. Figure 5 depicts how SB 2 revenues for MIP have changed over time.

Update on MIP. The $300 million in funding awarded to date—$128 million SB 2 funding and $172 million General Fund—has contributed to the creation of 5,500 housing units.

Governor’s 2022‑23 Budget Proposal

Augments Funding for MIP. In addition to the $65 million available for MIP in 2022 through SB 2 revenue, the budget proposes an additional $50 million General Fund in 2022‑23, and $150 million in 2023‑24, for MIP. Up to 5 percent of this funding could be used for state operations by CalHFA.

- Anticipated Outcomes. CalHFA anticipates the proposal would support the development of 5,000 additional housing units.

- Implementation Plan. CalHFA’s budget proposal does not identify dates for key milestones associated with awarding this funding.

Portfolio Reinvestment Program

Background

Portfolio Reinvestment Program. The 2021‑22 budget provided HCD $300 million one‑time ARP fiscal relief funds for capital improvements to affordable housing developments with affordability covenants that are due to expire within five years—December 2026. These housing units would transition to market‑rate housing if the covenants expire. As a result, the funding is intended to preserve the state’s affordable housing stock because projects that receive this funding are required to recommit to affordability covenants. This newly created program was intended to provide the department the flexibility necessary to maintain the supply and quality of the affordable rental housing units for which there has already been a significant public investment.

Update on Portfolio Reinvestment Program Spending. HCD has completed program design and intends to issue the NOFA in March 2022, with awards starting October 2022.

Governor’s 2022‑23 Budget Proposal

Expands and Augments Funding for Portfolio Reinvestment Program. The budget proposes $50 million General Fund in 2022‑23, and $150 million in 2023‑24, to preserve targeted units in infill and low‑VMT areas and continue bolstering the state’s affordable housing stock. Budget related legislation would preserve affordable HCD‑funded multifamily rental projects at risk of converting to market‑rate within the next ten years, beyond the five years authorized for the 2021‑22 funding. Funds would be used for rehabilitation, including upgrading systems to promote energy efficiency and reduce GHG emissions, operating cost assistance, and recapitalizing project reserves. Projects that receive this funding would have to recommit to remaining affordable.

- Anticipated Outcomes. HCD anticipates preserving between 570 and 800 affordable housing units.

- Implementation Plan. HCD anticipates releasing the NOFA in 2022‑23 and awarding funds in 2023‑24.

Mobilehome Park Rehabilitation and Resident Ownership Program

Background

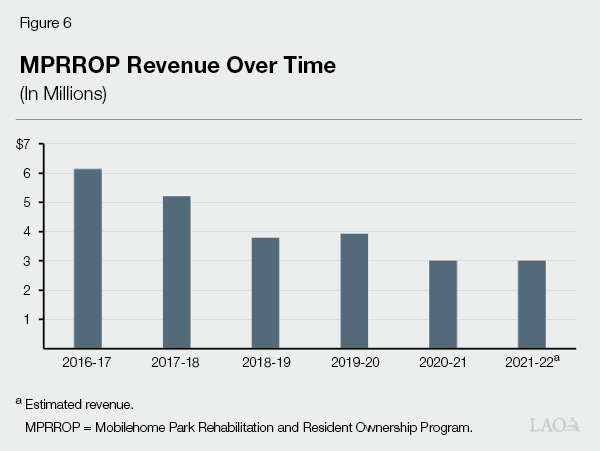

Mobilehome Park Rehabilitation and Resident Ownership Program (MPRROP). The program helps to preserve affordable mobilehome parks by offering loans (1) so a resident organization, nonprofit entity, or local public agency can purchase (convert) a mobilehome park; (2) for rehabilitation or relocation of a purchased park; and (3) so low‑income residents can purchase a share or space in a converted park or to pay for the cost to repair low‑income residents’ mobilehomes. MPRROP was established in 1984 and is funded through a registration fee on some manufactured homes and loan repayments from prior loans. All manufactured homes sold new on or after July 1, 1980 pay local property tax and are not subject to the annual fee. Therefore, over time, the number of manufactured homes registered annually have declined. There are currently 208,700 mobilehomes and manufactured homes subject to annual registration. HCD does not have a projection on the rate of reduction. As mobilehomes are installed on foundation systems and mobilehome owners convert to property taxes, the amount of funding available diminishes each year. The budget does not propose changes to this fee revenue sources. Figure 6 depicts how MPRROP revenues have changed over time.

Update on MPRROP Spending. The most recent MPRROP NOFA announced the availability of approximately $34 million to award. Since its inception, MPRROP has awarded approximately $70 million, supporting approximately 70 mobilehome parks.

Governor’s 2022‑23 Budget Proposal

Expands and Proposes General Fund for MPRROP. The budget proposes $25 million General Fund in 2022‑23, and $75 million in 2023‑24, to finance preservation and conversion of affordable mobile home parks. Recently introduced budget‑related legislation would change the MPRROP name to the Manufactured Housing Opportunity and Revitalization (MORE) Program and expand its authority to provide funding to support climate goals and conditions in mobilehomes and mobilehome parks. We continue to review the legislation.

- Anticipated Outcomes. The budget proposal indicates that under a possible funding structure, 40 percent of funds could support park infrastructure and clean‑up, 35 percent could support repairs and replacements of manufactured homes, 20 percent could support park acquisition and conversion, and 5 percent could support program administration. The administration does not commit to this specific breakdown.

- Implementation Plan. HCD anticipates developing guidelines by January 2023 and releasing the NOFA in May 2023. Applications would be evaluated as they are received. Depending on when applications were received, awards could be announced as soon as July 2023 and would continue on a flow basis until the open application period ends or the amount available has been awarded, whichever occurs first.

LAO Comments

Overall Housing Comments

Devote Attention to Overseeing Recent Augmentations. We suggest the Legislature dedicate the early part of the budget process to overseeing the implementation of last year’s significant augmentations. In our examination of recent investments, described above, we have learned about the status of funding disbursements, when unawarded funds are anticipated to be released, and have an initial understanding about the number of housing units that may be created through recent augmentations. However, there is more to learn as the Legislature conducts oversight of these programs, assesses their performance, and identifies opportunities to improve their operation. For instance, (1) what were the challenges and successes in standing up some of the newer programs, such as the State Excess Sites Program and the Portfolio Reinvestment Program; (2) what are the demonstrated program successes and/or are there opportunities for improving these programs; (3) are there capacity constraints that are limiting the effectiveness of these programs; (4) where are resources being allocated and for what purposes; (5) when will housing units start to come on line; and (6) are state, local, and regional entities coordinating effectively? Prior to authorizing increased funding for the activities proposed in the 2022‑23 budget, ensuring that the housing efforts authorized in prior budgets are operating effectively will be important. Ultimately, assessing the performance of current programs and taking stock of how prior actions collectively have moved forward the state’s housing response could inform the Legislature’s budget decisions in 2022‑23.

Governor’s Interest in Aligning Housing and Climate Goals Meritorious, More Concerted Efforts Necessary to Achieve Alignment. As has been the case in recent years, the Governor’s budget continues to acknowledge the significant need for additional housing in the state and proposes programs that support housing development. At the same time, the 2022‑23 housing package reflects a secondary benefit related to meeting climate change goals when the state is strategic in building new housing. While increased housing development is of foremost importance to address the state’s housing affordability challenges, increased focus on where housing is built will be necessary to mitigate and adapt to the current and growing impacts of climate change. Many of the Governor’s budget proposals would support more dense housing development—near jobs, schools, and other community amenities—that can be accessed with public transportation, reducing dependence on vehicles, and limiting GHG emissions. In addition to helping to mitigating climate change, some of these proposals would help the state respond to the current impacts of climate change. For example, the proposed MPRROP funding could support weatherization activities to make manufactured homes more resilient to the impacts of extreme heat. These are meritorious goals, but additional action is needed over the long term to build new, and protect existing, housing from the impacts of climate change.

Assess How Governor’s Housing Package Moves State Forward Towards Addressing Housing Goals. Collectively, the Governor’s housing proposals would help build more housing across the state, however, precisely how much and where is unclear. For each component of the Governor’s housing proposal, we suggest the Legislature engage the administration in a discussion of the (1) allocation process, (2) eligible activities and program guidelines, and (3) expected housing production achievements. Another element to consider is the extent to which the proposed augmentations align with the recent land use and housing policy changes the state has enacted. Recent policy changes made by the Legislature could have significant impact over time. Are there ways in which budget actions could help ensure their success, as well as better support local planning efforts? For example, now that the state has streamlined the process for homeowner to create a duplex and/or subdivide their property, should the state provide incentives for people to leverage this legal flexibility?

Consider Evaluating Distribution of Housing Development to Ensure Equitable Support. Beyond the general benefits of greater housing supply, there also are benefits from targeting housing resources to ensure equitable support. While households across the state face housing affordability challenges, some regions of the state have a more acute housing crisis. Furthermore, some communities, have faced historical inequities that make it more difficult for them to access housing that is both affordable and suits their needs. The Legislature may wish to consider how to target resources to support housing development in locations, and among communities, most in need of additional affordable housing. To help the Legislature inform this assessment, the Legislature could assess if there are inequities is how funds have been disbursed and consider solutions, such as geographic set asides, to address any issues identified.

State’s Capacity to Fully Utilize Proposed Funding Unclear. In many cases, the proposed funding is many orders of magnitude above what has been provided previously for programs. While directing augmentations to existing programs helps to expedite release of funding compared to establishing new programs, do these existing programs have capacity to absorb the proposed funding? The state’s ability to spend the major augmentations within the proposed time lines is unclear.

Consider Longer‑Term Plan for Expanded State Role in Housing. The scale of the housing crisis in California is significant. Addressing this crisis requires a complex combination of fiscal resources and policy solutions. The Governor continues to rely on one‑time resources to address the state’s ongoing housing challenge. As more information about recent state efforts becomes available, we suggest the Legislature assess which programs appear most effective at quickly and cost‑effectively producing housing. As the impact of recent budget augmentations and policy changes start to come to light, this will better position the Legislature to determine where continued actions are necessary and help guide the state’s long‑term fiscal strategy in addressing housing development and affordability. For instance, the state could consider establishing a housing fund for use over multiple years in order to support housing development.

State Appropriations Limit (SAL) Considerations. The SAL constrains how the Legislature can spend revenues that exceed a specific threshold. Given recent revenue growth, the SAL has become an important consideration in the state budget process and will continue to constrain the Legislature’s choices in this year’s budget process. However, certain types of spending, like some funding for capital outlay, are excluded from this limit. Some prior housing funding—such as General Fund spending on IIG—has met the SAL definition of capital outlay and has been excluded from the limit. As the Legislature crafts its housing package, allocating funding to housing programs excluded from the SAL could allow the state to allocate more funds to those programs than it otherwise could.

For Any Authorized Funds, Set Clear Expectations and Establish Metrics to Assess Performance. We recommend the Legislature consider how the state would coordinate work related to these proposals across programs and departments. Setting clear expectations through statute and establishing reporting requirements to facilitate oversight over the state’s progress towards addressing the housing crisis will be critical.

Proposal Specific Comments

Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities Program

Volatile GGRF Revenue Makes Predicting Annual AHSC Program Funding Difficult. Revenue from quarterly cap‑and‑trade auctions is deposited into the GGRF, and the funds are allocated to various climate‑related programs. The auction proceeds are a very volatile revenue source, which makes predicting the annual amount going to AHSC difficult.

Modifications to GGRF Continuous Appropriation Could Provide AHSC Program More Funding Predictability. The Legislature could consider a variety of modifications to the continuous appropriations to help address the revenue volatility. For example, the Legislature could consider allocating a specific annual amount to each continuously appropriated program, rather than a set percentage of auction revenue. This approach would provide a more consistent funding amount for these programs. Plus, if annual revenue continues to grow, this structure would allow the Legislature to use the annual budget process to determine how to allocate the additional funding in a way that best reflects its changing priorities. Furthermore, most of the continuous appropriations were established as part of the 2014‑15 budget, and legislative priorities may have changed over the last several years. If the Legislature were to determine that the AHSC Program were a much higher priority than other programs receiving GGRF revenue, the continuous appropriations could be reset accordingly.

Are One‑Time General Fund Revenues Better Allocated to Housing Programs Without Ongoing Revenue Source? Despite its volatility, GGRF is a continuously available source of revenue for the AHSC Program. Many HCD housing programs operate through bond proceeds or one‑time General Fund. We suggest the Legislature assess how much total funding it wishes to allocate towards the AHCS Program, then assess if there is a gap between interest and available GGRF revenue. Any gap in funding could be addressed through a General Fund appropriation.

Mobilehome Park Rehabilitation and Resident Ownership Program

Existing Revenue Source Is Declining. Revenue from the annual mobilehome registration fee has declined significantly since 2016‑17. In 2021‑22, the administration estimates the fee will generate $3 million. Current revenues are insufficient to support the current program objectives. In the near term, how the fee revenue supporting the existing program would interact with the proposed MORE Program is unclear. Would the fee revenue roll over to the MORE Program?

Details on Focus of Proposed New Program Will Be Important. Recently introduced budget‑related legislation will significantly change the scope and purpose of program. While we simultaneously continue to review the language, we suggest the Legislature ask: (1) how would the scope of eligible recipients change; (2) what activities could be funded through the program; (3) what criteria would the state use to evaluate applications and make funding decisions; (4) what steps would the state take to ensure geographic equity of awarded funds; (5) how would the state allocate funds among the various spending categories, such as clean‑up and acquisitions; and (6) how the state will help preserve long‑term affordability of manufactured homes?

Conclusion

Addressing California’s housing crisis is one of the most difficult challenges facing the state’s policy makers. Millions of Californians struggle to find housing that is both affordable and suits their needs. While the Governor proposes funding for specific programs that expand the availability of affordable housing and expand housing development, the Legislature could assess if the focus of these programs align with the Legislature’s priorities. Furthermore, the Legislature could assess opportunities to enhance the effectiveness of recent legislation by allocating resources towards those efforts. Ultimately, the enormity of California’s housing challenges suggest that policy makers engage on a variety of solutions. The crisis also is a long time in the making, the culmination of decades of shortfalls in housing construction. And just as the crisis has taken decades to develop, it will take many years or decades to correct.