LAO Contact

February 16, 2022

The 2022‑23 Budget

Public Health Foundational Support

- Background

- Governor’s Budget Proposal

- Assessment of Spending Plan

- Issues for Legislative Consideration

Summary

Public Health Funding Historically Limited. Funding for the California Department of Public Health (CDPH)—the majority of which typically flows to local health jurisdictions (LHJs)—has been largely stagnant since 2007‑08 until the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Pandemic Exposed Gaps and Led to Augmentation Beginning in 2022‑23. The pandemic highlighted the critical role of public health systems, but also their understaffing and inadequate information technology (IT) systems and lab capacity. The 2021‑22 budget agreement committed ongoing funding of $300 million General Fund for CDPH and LHJs beginning in 2022‑23.

Governor’s 2022‑23 Budget Includes Proposed Spending Plan for the $300 Million. Based on findings and recommendations of a workgroup convened in 2021, the plan would retain $100 million for CDPH and direct $200 million to LHJs. State activities would focus on six core areas, including staff recruitment and training, emergency response, IT, communications, community partnerships, and community health. The plan would require LHJs to dedicate 70 percent of funding for workforce and to submit triennial local public health plans tied to existing Community Health Assessments (CHAs) and Community Health Improvement Plans (CHIPs).

Despite Merits, Plan Omits Three Key Objectives. While the spending plan would increase real‑time disease surveillance, coordinate regional epidemiological and communications activities, and improve strategic planning, it omits (1) creating a workforce pipeline, (2) strengthening the statewide lab network, and (3) laying out an overarching IT strategy.

The Plan Could Have Stronger Oversight of LHJs. As written, the plan does not lay out minimum requirements or goals for LHJs. Tying local plans directly to CHAs and CHIPs (which can encompass goals beyond the purview of public health departments) may not be the best substitute for a more deliberate and consistent type of local plan across LHJs.

Issues for Legislative Consideration. As the Legislature reviews the proposal, we suggest:

- Asking for More Information. Consider requesting more information about the omitted objectives in the spending plan that we have identified.

- Incorporating Better LHJ Oversight. Consider requiring more CDPH management of local plan development and oversight of LHJs’ use of funds. Consider identifying common public health goals that the Legislature would prioritize universally.

- Developing Reporting Requirements. We suggest including regular reports to the Legislature on CDPH and LHJ efforts.

- Implementing Plan Through Trailer Bill Language. The administration proposes implementing the spending plan through budget bill language. We suggest developing trailer bill language to establish the plan’s requirements.

Background

CDPH Funding Historically Drawn From Fund Sources Dedicated to Specific Purposes. Historically, the vast majority of funding support for the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) has come from federal and state special funds. Most of CDPH’s federal funding is grant funding with strict spending and reporting requirements. For example, federal grants help fund health facility certification to receive Medicare and Medicaid payments. They also fund prevention and response (including vaccination) to infectious diseases, including outbreaks of specific diseases (such as Zika or COVID‑19) and ongoing diseases, such as sexually transmitted diseases and HIV/AIDs. Similarly, CDPH’s state special funds—which support activities such as childhood lead poisoning prevention, tobacco control, genetic disease testing, and health facility state licensing—must be spent only on the specified purpose. In contrast, the General Fund historically has supported a relatively small portion of the CDPH budget. General Fund support typically ebbs and flows year over year based on one‑time appropriations for specific activities such as Alzheimer’s disease research grants or support for sickle cell disease centers. In summary, very little of the funding supporting the CDPH budget can be used flexibly.

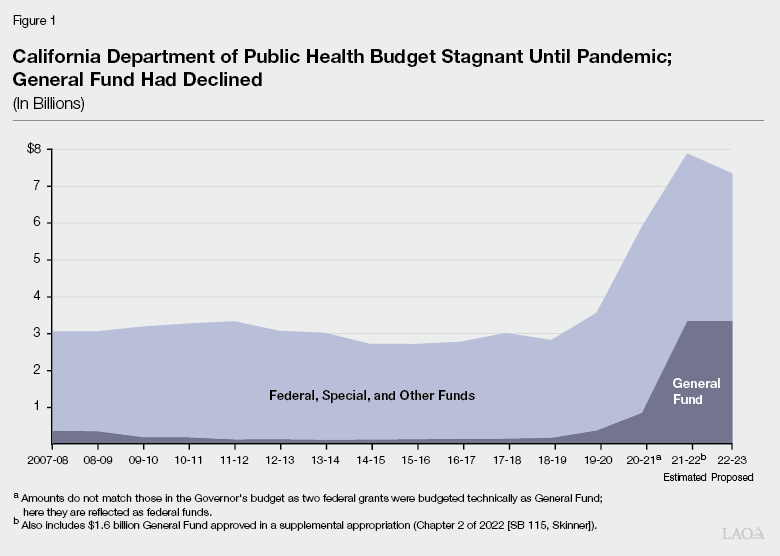

Until the Pandemic, Overall Funding for CDPH Was Stagnant; General Fund Support Had Declined. As shown in Figure 1, between 2007‑08, when CDPH became a standalone department (it was formerly a division within the then‑Department of Health Services), and the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic in 2019‑20, the overall CDPH budget was relatively stagnant and was about $3.4 billion at its peak. General Fund support declined in 2009‑10 (during the Great Recession) and was never fully restored. The most CDPH received from the General Fund prior to the pandemic was in its first year as a standalone department: $361 million in 2007‑08.

CDPH Provides Guidance to Local Health Jurisdictions (LHJs). California has 61 LHJs—58 county public health departments and three city public health departments. LHJs carry out many of the state’s public health programs, for example, by responding to local disease outbreaks and reporting diseases to the state, conducting restaurant health inspections, offering immunizations, conducting home visiting, and maintaining vital records. Twenty‑eight LHJs operate a local public health lab (since 2009, 12 local public health labs have closed; LHJs without their own lab often contract with a neighboring local public health lab for services). CDPH provides overall direction for many of the programs carried out at the local level and allocates funding to the LHJs to administer the programs.

Large Share of CDPH Budget Provided to LHJs. Prior to the pandemic, anywhere between 67 percent and 83 percent of CDPH funding flowed to LHJs. (In the 2020‑21, 2021‑22, and proposed 2022‑23 budgets, a larger‑than‑typical share of funding has gone or is proposed to go to state operations for COVID‑19 response.) LHJs also receive state‑local realignment funding for health (which includes indigent health care and public health). Local governments have some discretion over how health realignment funds are spent. In addition, they can supplement state funding for public health from other local sources of funding and may handle and define public health functions somewhat differently from one another. Consequently, the state currently does not have good statewide data on each LHJ’s total public health spending.

COVID‑19 Pandemic Highlighted Critical Role of Public Health System and Exposed Gaps in Its Current State. A primary statutory responsibility of state and local public health is controlling and responding to communicable disease outbreaks. When COVID‑19 first was detected in California, CDPH and LHJs began to issue public health orders; collect reportable disease data; investigate cases and conduct contact tracing; report information to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Governor, other state agencies, and LHJs; and issue guidance to health facilities, schools, businesses, and the general public. As the COVID‑19 pandemic took hold, however, the state’s public health systems quickly became overwhelmed. CDPH and LHJs did not have enough staff to respond—let alone maintain their other public health responsibilities simultaneously—and IT systems and public health lab capacity was quickly exceeded. In addition, state and local officials struggled with timely and consistent public health messaging and guidance, particularly in light of changing direction from the federal government. The pandemic also revealed that the state’s approach to public health had not enabled the strategic planning that might have prepared the system for a crisis of this scale and breadth.

2021‑22 Budget Agreement Pledged Ongoing General Fund Support Beginning in 2022‑23. The 2021‑22 budget included $3 million General Fund one time for CDPH to conduct a review of essential public health infrastructure requirements using the pandemic as context and to inform a proposal in the Governor’s 2022‑23 budget. The budget agreement also included a commitment to provide CDPH with $300 million General Fund ongoing beginning in 2022‑23. Using the $3 million appropriation for the review, CDPH hired a contractor and formed a “Future of Public Health” workgroup, comprised of state and local public health employees; state employees from the California Health and Human Services Agency and Department of Finance; and representatives of the County Health Executives Association of California (CHEAC), Health Officers Association of California, and Service Employees International Union (SEIU). Activities included analyses of existing data and research; surveys with state and local public health; and discussions and individual interviews with a wide variety of public health practitioners, experts, and stakeholders, including state and local public health staff, public health lab directors, public health associations, and several advocacy organizations. CDPH completed the review, producing a memo, “Investments and Capabilities Needed for the Future Public Health System” in September.

Governor’s Budget Proposal

The Governor’s budget reflects the agreement made last year to provide $300 million General Fund ongoing to CDPH starting in 2022‑23. The Governor’s budget also includes a proposal for how to allocate those funds and includes basic details in budget bill language. Additional details about the proposed plan follow, but at a high level, $100 million would be retained for state operations and $200 million would be directed to LHJs. The first allocation of funds in 2022‑23 would be available for expenditure over three years.

Proposed Spending Plan for State Operations

The proposed spending plan would provide $100 million for state operations and is built around six foundational areas. The Future of Public Health workgroup identified these six core governmental public health spending areas at the state level that support and complement the work of LHJs, health care providers, and other health‑related organizations. (It differentiates “governmental” public health services from public health services that might be provided by community‑based organizations (CBOs), hospitals, or other health‑related organizations.) Figure 2 shows the funding and positions proposed in the spending plan for each of the six core governmental public health spending areas. Additional highlights of the plan are described below.

Figure 2

Proposal for State Operations Includes

Support for Six Foundational Spending Areas

2022‑23, General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

Public Health Governmental Spending Areas |

Expenditures |

Positions |

|

1. Workforce Development, Recruitment, and Training |

$57.9 |

270 |

|

2. Emergency Preparedness and Response |

27.6 |

77 |

|

3. IT, Data Science, and Informatics |

0.6 |

3 |

|

4. Communications, Public Education, Engagement, and Behavior Change |

4.5 |

26 |

|

5. Community Partnerships |

2.9 |

5 |

|

6. Community Health Improvement |

6.2 |

23 |

|

Totals |

$99.6 |

404 |

|

Note: Amounts may not add to total due to rounding. |

||

|

IT = information technology. |

||

Increases Staffing. The plan proposes 404 new positions at CDPH, a 15 percent increase across the relevant CDPH centers and offices, which had 2,617 authorized positions as of December 1, 2021. CDPH intends to draft duty statements for the 404 new positions from January through May of this year, begin advertising positions from May to July, and conduct interviews and make candidate selections from July to October.

Creates Office of Policy and Planning. The Office of Policy and Planning would conduct strategic planning to assess current and emerging public health threats. This office also would be accountable for use of the funding provided in the spending plan, including by establishing performance targets and publishing an annual report measuring performance. More broadly, this office would build internal capacity to meet future strategic leadership needs.

Provides Regional Support. The plan includes ways to support both state objectives and LHJs by enhancing regional expertise and activities. For example:

- Establishes a Regional Public Health Office. This office, housed at CDPH, would include regional specialists for each of the five public health officer regions (Bay Area, Rural North, Greater Sacramento, San Joaquin Valley, and Southern California). These regional specialists would provide expertise in analytics, epidemiology, and communications for smaller LHJs and would assist in standardizing state policy.

- Adds a Regional Disaster Medical and Health Specialist to the State’s Mutual Aid Regions. Currently, each of the state’s six mutual aid regions have a Regional Disaster Medical and Health Coordinator and two Regional Disaster Medical and Health Specialists (whose expertise typically is in emergency medical services). CDPH proposes to add a third Specialist, whose expertise and background is in public health.

Establishes 24/7 Intelligence Hub. This hub would replace the current duty officer program, which provides 24‑hour coverage to receive notifications about emerging public health threats and is staffed by redirected full‑time staff who take turns being on duty around the clock. The new hub instead would be staffed with dedicated employees and include enhanced surveillance and analytic capabilities to make it more proactive on emerging threats. It would include better real‑time surveillance by having California participate in the CDC’s National Syndromic Surveillance Program, BioSense, which collects patient encounter data from emergency departments and can be used to identify health threats by tracking patient symptoms before diagnoses are confirmed. California currently is the only state that is not engaged actively in BioSense.

Forms Dedicated Recovery Unit. This unit would help coordinate health‑related recovery efforts following emergencies and establish community recovery guidance.

Expands State Lab Support. CDPH’s lab‑related activities include operating the state’s public health lab and licensing clinical labs and personnel. These programs would receive 25 new positions, with increased emphasis on workforce training; genomic sequencing for disease surveillance; and centralization of key lab functions, such as safety, regulatory compliance, and quality management.

Proposed Spending Plan for Support to LHJs

CDPH would allocate $200 million annually to LHJs. To receive funds, each LHJ would be required to submit a local public health plan by July 1, 2023 and every three years thereafter.

Allocates Funding Based on Local Population and Demographics. CDPH would award each LHJ a base grant of $350,000. Remaining funding would be based proportionally on an LHJ’s share of the state’s population (50 percent of funding); level of poverty (25 percent of funding), and share of black/African American, Latino, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander residents (25 percent of funding).

Requires LHJs to Submit Local Public Health Plans. An LHJ’s plan would be aligned with their existing Community Health Assessment (CHA) and Community Health Improvement Plan (CHIP), including proposed evaluation methods and metrics. LHJs must complete CHAs and CHIPs if they want to seek public health accreditation by a national board. (Accreditation means a public health department attests to a certain level of performance, has capacity to carry out essential public health services, and adheres to certain standards.) Typically, CHAs and CHIPs are updated every three to five years. CDPH worked with the California Conference of Local Health Officers (CCLHO), CHEAC, and SEIU to develop this approach.

Requires LHJs to Dedicate Majority of the Funding to Workforce. CDPH would require LHJs to spend 70 percent of their funding on workforce, particularly to fill staffing gaps identified during the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Requires Funding to Augment Existing Resources. CDPH would require LHJs to sign written attestations that the new funding does not replace existing public health resources.

Proposed New Requirement for Nonprofit Hospital Community Benefit Plans

The spending plan proposes a new requirement (which would be enforced by the Department of Health Care Access and Information [HCAI]) requiring nonprofit hospitals to direct 25 percent of their community benefit plan funds to CBOs in support of local public health efforts and to demonstrate how this spending addresses social determinants of health. (Nonprofit hospitals, in exchange for their tax‑exempt status, are required to use some of their resources for community benefits, such as charity care, based on a community needs assessment.)

Assessment of Spending Plan

Providing more sustained, flexible General Fund support for public health was an important priority for the Legislature in reaching the 2021‑22 budget agreement. The administration lived up to its commitment to examine the future of public health, producing a memo with its findings and recommendations and developing the associated spending plan proposal. Below, we discuss the merits of the proposal and identify a few issues, which, if addressed, we believe would strengthen the plan.

Plan Has Numerous Merits

The spending plan reflects a relatively cohesive approach to improving public health systems in California. In particular:

- It is based on quantitative and qualitative input from a wide variety of practitioners and stakeholders at both the state and local levels.

- The plan is forward‑looking, addressing ways the department can be more proactive and strategic in a cost‑effective way. For example, the Office of Policy and Planning will emphasize evaluation, measurement, and strategic planning.

- It includes a multifaceted approach to workforce recruitment and retention, including several options for internal training, education, and promotion. The internal professional development options could help cultivate future CDPH leadership.

- It stresses real‑time disease and emergency surveillance with a dedicated 24/7 Intelligence Hub and by participating in BioSense.

- It provides regional support and coordination, as well as regional resources to fill gaps in epidemiological, analytic, or communications expertise at smaller LHJs.

- It applies an equity lens to its proposed funding allocations and activities with a goal of reducing health disparities among all Californians.

In Its Current Form, Spending Plan Omits Three Key Objectives

Does Not Create a Public Health Workforce Pipeline. The current plan focuses on enhancing recruitment and hiring strategies, promoting interest in working at CDPH, and training and developing current employees—all important activities to improve CDPH’s current capacity. However, it does not discuss creating a future public health workforce pipeline despite significantly increasing staffing resources at the state and local levels. (The Governor’s health‑related workforce development proposal—referred to as the Care Economy Workforce Development Package—primarily concerns health care delivery rather than public health.) We understand that CDPH did not consult with HCAI—the state entity operating a number of existing health‑related workforce development programs—noting it did not do so because HCAI is focused on the health care workforce, rather than the public health workforce. Nevertheless, we think that CDPH likely could learn from HCAI’s experience when it comes to various tools and strategies for increasing the supply of potential workers in the health field.

Does Not Strengthen Public Health Laboratory Network Statewide. While the plan enhances state lab activities, it does not include a clear strategy for integrating the 28 local public health labs and the state lab into a cohesive network. CDPH noted that LHJs would have the option to use their new flexible funding to hire lab staff. The spending plan does not include any minimum capacity requirements for local public health labs, however. At a higher level, it also does not address whether there are enough local public health labs around the state or how well the existing local public health labs and the state lab work collaboratively as a network.

Does Not Yet Include an Overarching Information Technology (IT) Strategy. While the plan acknowledges the importance of IT for public health activities by recognizing it as one of the foundational governmental public health spending areas, it does not allocate any of the $300 million to IT (beyond a specific $548,000 project) and it does not include an overarching IT strategy. (A separate proposal would support COVID‑19/infectious disease‑related IT systems.) CDPH notes that assessments are being conducted to develop a comprehensive strategic technology plan and that it will be hiring a Chief IT Strategist to lead this effort. When this proposed strategy will be available and how this future vision would be funded is unclear.

Oversight and Accountability of LHJs Could Be Strengthened

The plan indicates that CDPH worked with CHEAC, CCLHO, and SEIU to develop the spending plan’s approach for the funding of local activities and accountability for the use of funds. The process for developing and implementing local plans, however, remains vague and there are untapped opportunities to increase the oversight of, and accountability for, the LHJs’ implementation activities. In particular:

Plan Does Not Include Minimum Public Health Goals for LHJs. While the plan notes that CDPH would collaborate with CHEAC, CCLHO, and SEIU to develop minimum requirements for the funding and statewide metrics, it currently does not include any stated public health goals that every LHJ should achieve. We recognize the importance of LHJs having greater flexibility over the use of funds than they do in the current environment. However, the Legislature may have some specific goals for local public health, even if it does not prescribe the way LHJs must achieve them.

Plan Assumes Nearly One‑Third of LHJs Can Quickly Develop a CHA and CHIP. Budget bill language would require LHJs’ plans to be tied to their CHAs and CHIPs, including evaluation methods and metrics. According to CDPH, 22 LHJs are accredited already and 20 LHJs actively are seeking accreditation, meaning they have a CHA and CHIP or are in the process of developing them. This means that up to 19 LHJs are not accredited nor seeking it, and thus may not have a CHA and CHIP in place already. (An LHJ could have a CHA or CHIP, but not seek accreditation.) CDPH said it would require LHJs to prepare them if they do not already have them and would provide technical assistance. Whether these 19 LHJs would be able to successfully complete high‑quality CHAs and CHIPs to form the basis of their local plans by July 1, 2023 and how much and what type of support and technical assistance they would need to do so are unclear. If there is another COVID‑19 surge, this could be further complicated. In addition, LHJs with completed CHAs and CHIPs likely should update them with lessons from the pandemic, but the extent to which this will be done or is feasible is unclear. LHJs likely would wait instead until the next update.

How Closely Local Plans Must Be Tied to CHAs and CHIPs Is Unclear. Some of the issues, goals, and metrics in CHAs and CHIPs can be broad and extend beyond the direct purview of public health. For instance, they can include strengthening the health care workforce and increasing stable housing options. Consequently, there may not be a direct link between CHAs and CHIPs and efforts to improve foundational public health. Moreover, the time line for updating CHAs and CHIPs may not align with local plans. The Governor’s proposal does not specify how to tie CHAs and CHIPs to local plans or whether the updates to these plans should be aligned.

Plan Lacks Common Standards. The proposed plan does not specify whether CDPH will provide guidance, templates, or examples of what LHJs should include in their local plans. Each LHJ may have slightly different goals or planned activities. However, whether all 61 local plans will define categories similarly or use consistent methods to measure progress is unclear.

Plan Does Not Address Coordination of State and Local Public Health Messaging. Although LHJs have discretion and legal authority for various public health activities in their jurisdictions, the COVID‑19 pandemic demonstrated the risk of having too many mixed messages from governmental public health authorities. While the regional support of communications for smaller LHJs makes sense, the plan does not discuss what steps the state and LHJs might be able to take more broadly to improve and coordinate public health communications statewide.

Plan Does Not Specify How CDPH Will Report Back to the Legislature

As written, the proposed spending plan does not require any reporting to the Legislature about the implementation of the plan or whether CDPH and LHJs are meeting their identified performance indicators. CDPH told our office it will report to the Legislature at budget hearings. While we support having such testimony and opportunities for oversight, the Legislature might want to consider having a more formalized means of reporting. We discuss this issue further below.

Basic Plan Details Are in Budget Bill Language, Rather Than Trailer Bill Language

Trailer bill language would allow the Legislature more opportunity to provide policy direction about the $300 million augmentation for public health foundational support and would ensure the augmentation is ongoing. Budget bill language, on the other hand, provides only limited detail and concerns appropriations made over the single budget year, meaning the $300 million still would be in question in the next budget cycle.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Based on our assessment, we raise several issues for legislative consideration below. In sum, the proposed spending plan for $300 million presents a promising approach to improving the state’s governmental public health systems. The issues we raise below, if addressed, offer opportunities to strengthen certain aspects of the spending plan and increase legislative oversight.

Addressing the Spending Plan’s Missing Pieces

The Legislature could consider asking the administration for more information about the plan’s missing elements and how these elements potentially could be incorporated in a revised spending plan. Specifically, the Legislature could ask about the following issue areas:

Workforce Pipeline and Integrated State‑Local Public Health Lab Network. The Legislature could ask the administration how these elements could be incorporated in the spending plan and how much these elements could cost. The Legislature then could consider whether it wishes to augment funding to support these activities or reduce funding for some aspects of the plan.

An IT Strategic Plan. While the spending plan does not currently reflect a strategic plan for IT‑related expenditures, CDPH indicated it will be developing an IT strategy after hiring a Chief IT Strategist. Nevertheless, the Legislature could request that CDPH produce a more specific time line for this strategy and its associated deliverables and seek a description of the steps the administration will undertake to develop this strategy.

Improving LHJ Oversight Issues

The current plan does not provide much detail about, or direction to, LHJs about CDPH’s expectations for LHJs’ use of the $200 million in funding. The Legislature could consider the following.

Refining Process for Preparing Local Plans. The Legislature might consider whether the proposal to have LHJs’ local plans tied to CHAs and CHIPs should be refined. For example, it could instead consider requiring CDPH to develop a template and provide associated guidance and examples for all LHJs to use. This not only would provide greater consistency (making statewide review and evaluation easier), but also it would ensure that the proposed activities and targets were practicable for a public health department. These local plan submissions could be informed by the CHAs and CHIPs, even if not tied to them directly.

Identifying Specific Requirements for LHJs. The Legislature might wish to identify specific requirements for LHJs that it would prioritize universally in local public health. For example, the Legislature could require that LHJs meet specific goals or spend a minimum level of funding for specific purposes, such as increasing local public health lab capacity. We think the Legislature could add such parameters without unduly impeding local flexibility to address local public health needs and challenges.

Developing Accountability System. The administration’s proposed plan does not specify how LHJs would be held accountable for making progress toward plan metrics. The Legislature could consider whether CDPH should be tasked with providing additional supports to LHJs that are not meeting outlined objectives.

Increasing Legislative Reporting Requirements

The Legislature might want to consider specific reporting from CDPH to increase its oversight of the $300 million spending plan, but also to increase its understanding of emerging public health issues. The Legislature could:

Require Interim Reporting to the Legislature Throughout Year One. This could include reporting on: hiring numbers, status of internal training and educational opportunities, status of the LHJ plans (especially in the counties currently without CHAs and CHIPs), and other implementation challenges.

Require Informal and Formal Reporting to the Legislature at Specific Intervals on an Ongoing Basis. The Legislature could consider additional types of reporting to increase oversight and awareness of key public health issues and threats. This could include, for example:

- Informal reporting to the Legislature when potential public health threats reach a particular threshold.

- Annual updates about the $300 million spending plan (which could be presented at budget hearings), including discussion of progress toward full implementation of the core spending areas; updates on various initiatives in the plan, such as development and implementation of statewide performance targets; updates on strategic IT planning and projects; how it is holding LHJs accountable for making progress toward local plan metrics and status of LHJs meeting these targets; and a basic summary of the state of the state’s public health. These updates also could address public health communications challenges across state and local public health systems and how these might be ameliorated.

- Five‑year and/or ten‑year reviews about the state of state’s public health, which could include progress toward meeting identified performance and outcome indicators (set by the Legislature), including reducing health disparities, challenges facing state and local public health, and key data and information about ongoing and emerging or anticipated future public health issues. The administration could request funding for these reviews and we recommend the Legislature require that they be conducted by an unbiased third party, such as an academic or research institution.

Shift Implementing Language From Budget Bill Language

to Trailer Bill

An augmentation and policy of this magnitude should be handled in trailer bill language. We suggest the Legislature require the administration to add the plan’s implementing language to trailer bill.