LAO Contact

March 3, 2022

The 2022‑23 Budget

Analysis of the Governor’s

Major Behavioral Health Proposals

- Introduction

- Behavioral Health Bridge Housing Proposal

- IST Workgroup Solutions Package

- New Medi‑Cal Mobile Crisis Intervention Services Benefit

- Overarching Comments

Summary

In this brief, we analyze the Governor’s three major behavioral health budget proposals.

Behavioral Health Bridge Housing Proposal. The Governor’s budget proposes $1 billion General Fund in 2022‑23 and $500 million General Fund in 2023‑24 to provide short‑term housing intended to transition individuals with significant behavioral health needs out of unsheltered homelessness into a stable living environment in advance of further placement into permanent housing. While we find that this proposal appropriately targets a gap in the behavioral health treatment continuum and current state homelessness efforts, further specifics are necessary to fully assess the proposal’s merits. We recommend the Legislature adopt trailer bill language to specify its intent and terms for this proposed funding, including key details such as the balance of funding between tiny homes—a potentially promising approach that comes with trade‑offs—and more established bridge housing options. We also recommend that the Legislature consider trade‑offs between the proposal and modifying or expanding existing state homelessness programs, which may have greater capacity to deploy bridge housing immediately.

Incompetent to Stand Trial (IST) Workgroup Solutions Package. The Governor proposes an additional $317 million General Fund one time and $33.6 million General Fund ongoing to implement certain solutions from a workgroup convened to develop solutions to address the growing waitlist of felony ISTs awaiting admission to the Department of State Hospitals for competency restoration treatment. Although the priorities reflected in the solutions package are reasonable, we find that further efforts are needed to address underlying factors that impact the number of felony IST referrals. We recommend the Legislature use the budget process to provide input on the package and monitor the status of other promising ideas from the workgroup. We also find that the proposed cap on the number of county felony IST referrals (above which a county would pay a share of cost for felony IST treatment) raises state reimbursable mandate questions. Finally, we recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to explore the feasibility of counting additional funding as excluded from the State Appropriations Limit.

New Medi‑Cal Mobile Crisis Intervention Services Benefit. The Governor proposes $16 million General Fund ($108 million total funds) in 2022‑23—with funding ramping up in subsequent years—to add mobile crisis intervention services as a new Medi‑Cal benefit for five years. Although this proposal appropriately targets treatment gaps, we find that key details remain outstanding. We recommend the Legislature gather information before acting on this proposal and consider ways to ensure local capacity to provide this new benefit.

Overarching Comments. The Legislature may wish to consider how behavioral health fits within the state’s homelessness strategy, what the long‑term vision for the crisis continuum is, and how cross‑departmental coordination to address behavioral health issues can be facilitated.

Introduction

This brief provides an analysis of the Governor’s three major behavioral health budget proposals: (1) $1 billion General Fund in 2022‑23 and $500 million General Fund in 2023‑24 to the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) to provide short‑term behavioral health bridge housing options—through the existing Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program (BH‑CIP)—for individuals experiencing unsheltered homelessness with behavioral health needs; (2) an additional $317 million General Fund one time and $33.6 million General Fund ongoing (for a total of $93 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $571.6 million General Fund in 2022‑23 when combined with already authorized funding) to the Department of State Hospitals (DSH) to implement certain solutions developed by the Incompetent to Stand Trial (IST) workgroup that convened last fall in response to the substantial backlog of individuals found IST awaiting treatment in a DSH program; and (3) $16 million General Fund ($108 million total funds) to add mobile crisis intervention services as a new mandatory covered benefit in the Medi‑Cal program. We conclude this brief with some overarching issues for the Legislature to consider in its review of behavioral health proposals in general.

Behavioral Health Bridge Housing Proposal

Background

In California, Behavioral Health Services for the Most Severe Needs Primarily Are Funded and Delivered Through Counties. Counties have the primary role in the funding and delivery of public behavioral health—encompassing both mental health and substance use disorder (SUD)—services. In particular, counties generally are responsible for arranging and paying for community behavioral health services for low‑income individuals with the highest service needs. While some counties may provide short‑term housing supports to help stabilize individuals with significant behavioral health needs, generally this is not a focus of county behavioral health programs.

Many Individuals Experiencing Homelessness Also Have Significant Behavioral Health Needs… Although housing affordability is a major factor in the state’s homelessness crisis, there are many individuals experiencing homelessness who also have significant behavioral health needs. Estimates vary on exactly how many individuals experiencing homelessness also suffer from behavioral health disorders. In 2020, the U. S. Department of Housing and Urban Development estimated that 23 percent of people experiencing homelessness in California suffered from severe mental illness and 22 percent suffered from SUD. (There is possible overlap between these two populations, the degree to which is unknown.) The prevalence of behavioral health disorders also appears to differ for distinct categories of people experiencing homelessness. For example, researchers have estimated that the prevalence of mental illness and SUD is higher for people experiencing unsheltered homelessness than sheltered homelessness. Available research also indicates that experiencing homelessness may lead some individuals to develop or exacerbate existing behavioral health issues, due to the chronic stress of living without stable housing.

…And Would Benefit From Receiving Housing Support Paired With Behavioral Health Services. For individuals who both experience homelessness and have significant behavioral health needs, behavioral health services can be an essential component of addressing their homelessness. As discussed earlier, the chronic stress of living without stable housing can lead an individual to develop a behavioral health disorder. In turn, this can make it more difficult for an individual to escape homelessness as their behavioral health issues make it even more challenging to maintain housing stability. Accordingly, these individuals particularly benefit from a more comprehensive approach to care that includes housing supports paired with behavioral health services. For example, under permanent supportive housing models targeted at people with mental illness, mental health services are provided on‑site to individuals residing in designated housing units. These models also may help coordinate residents’ access to any necessary additional social services.

Most Recent State Homelessness Investments Have Not Focused on Behavioral Health. Historically, most homelessness assistance in California has been provided at the local level. However, in recent years, the state has begun to take a more active role in providing funding and support for local governments’ efforts to alleviate the homelessness issues in their jurisdictions (generally on a one‑time or limited‑term basis). Accordingly, there are several major state‑funded programs that support homelessness relief. Two of the larger programs have provided (1) flexible funding to local governments to address homelessness and (2) funding to invest in infrastructure—such as the purchase, renovation, and modification of facilities—to house people experiencing or at risk of homelessness. (For more information on the state’s recent efforts to address homelessness, see The 2022‑23 Budget: The Governor’s Homelessness Plan.)

Notably, most of these programs generally are not targeted at individuals experiencing homelessness who also have behavioral health needs and are not required to include the provision of behavioral health services. One notable exception is the No Place Like Home Program (NPLH), which allocates $2 billion (one time) to counties to construct new and rehabilitate existing permanent supportive housing for individuals struggling with severe mental illness who are homeless or are at risk of becoming homeless. The housing support provided through NPLH is paired with mental health services provided on‑site at the housing unit. In addition, local governments may (at their own discretion) choose to operate mental health programs focused on individuals experiencing homelessness. For example, counties are required to use a substantial share of their dedicated Mental Health Services Act (MHSA) revenues (roughly $1.4 billion annually statewide) to operate Full Service Partnership programs, which provide a comprehensive suite of services to people with severe mental illness under a “whatever it takes” approach. Under these programs, counties can elect to provide permanent supportive housing paired with mental health services.

BH‑CIP May Benefit Individuals Experiencing Homelessness. Last year, the state also began to take a more active role in providing funding and support for local governments’ efforts to alleviate the behavioral health issues in their jurisdictions. Specifically, the 2021‑22 budget created BH‑CIP, which provides temporary grant funding to support the development of new behavioral health treatment facilities. (We provide an implementation update for BH‑CIP later in this brief.) However, although people experiencing homelessness may receive behavioral health treatment at BH‑CIP facilities (and treatment for people with behavioral health disorders at these facilities may help prevent them from entering homelessness), they are not designated as a specific population of focus for this program (which is intended for people with behavioral health needs broadly).

California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal (CalAIM) Reforms Make Available Housing‑Related Services for Individuals With Behavioral Health Needs. The CalAIM initiative is a far‑reaching set of reforms to expand, transform, and streamline Medi‑Cal service delivery and financing. The state (in conjunction with counties and Medi‑Cal managed care health plans) currently is underway on implementation of several major components of CalAIM. CalAIM includes several reforms broadly intended to increase access to behavioral health services for Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. For example, it includes revisions to the criteria used to determine eligibility for certain Medi‑Cal behavioral health services to make it easier for Medi‑Cal beneficiaries to receive those services.

CalAIM also includes the addition of two new Medi‑Cal benefits targeted at the subset of Medi‑Cal beneficiaries with the most complex care needs. These complex care needs include issues related to homelessness and behavioral health. Specifically, CalAIM includes (1) a new enhanced care management (ECM) benefit to assist high‑need beneficiaries with navigating Medi‑Cal’s delivery systems and (2) a suite of new benefits—to be provided at the discretion of the managed care health plans that provide health care coverage to a majority of Medi‑Cal beneficiaries—known as “Community Supports,” which are nonmedical benefits aimed at addressing social factors that impact Medi‑Cal beneficiaries’ health status. Notably, several housing‑related services—such as housing navigation services and term‑limited payments for housing (such as for security deposits or first month’s rent)—are included as Community Supports options. Importantly, these Community Supports do not include funding to build housing infrastructure or pay for beneficiaries’ housing on a long‑term basis.

What Is Bridge Housing and Why Is It Important? Bridge housing—often known as transitional housing—is housing intended to transition individuals immediately out of homelessness into a stable living environment in advance of further placement into permanent housing. (Typically, applying, locating, and ultimately obtaining permanent housing takes some time.) Bridge housing can serve as a link between the homelessness shelter system and long‑term housing options. It often includes supportive services (such as employment and financial literacy counseling) provided on‑site at the bridge housing unit. In contrast to homelessness shelters (which in many cases do not provide a 24‑hour duration of residency), bridge housing residents typically are able to remain in their housing unit for a relatively extended period of time. This stability, combined with the supportive services received during bridge housing stays, increases the likelihood that an individual will be able to move into permanent housing and not fall back into homelessness. If bridge housing is targeted at individuals experiencing homelessness who also have behavioral health disorders, then it may also include the provision of behavioral health services on‑site.

Bridge Housing and Recent State Investments. The majority of the state’s recent major homelessness investments supported programs that are intended to provide permanent housing, rather than temporary bridge housing. (For example, the Homekey Program provides funding for the acquisition of hotels, motels, residential care facilities, and other facilities that can be converted and rehabilitated to provide permanent housing for persons experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness, and who also are impacted by COVID‑19.) In addition, as is the case for most permanent housing programs, the state homelessness programs that do provide for bridge housing generally do not require targeting individuals with behavioral health disorders. (For example, the Roomkey program provides hotel and motel rooms to provide immediate housing to vulnerable individuals experiencing homelessness at risk of contracting COVID‑19, and is intended to serve as an intermediate step to permanent housing. This program does not pair available housing options with the provision of behavioral health services.)

BH‑CIP Implementation Update

Below, we provide an implementation update for BH‑CIP, the most recent state investment for the creation of new behavioral health facilities. (As discussed earlier, although individuals experiencing homelessness are not a designated target population for this program as currently designed, they may ultimately access behavioral health treatment at BH‑CIP facilities.)

2021‑22 Budget Established BH‑CIP. The 2021‑22 budget package included $445.7 million General Fund ($755.7 million total funds) in 2021‑22, $1.2 billion General Fund ($1.4 billion total funds) in 2022‑23, and $2.1 million General Fund in 2023‑24 to implement BH‑CIP. Under this program, DHCS provides competitive grants to cities, counties, tribes, nonprofits, and corporations to increase behavioral health infrastructure, predominantly by constructing, acquiring, or renovating facilities for community behavioral health services (contingent on these local entities providing matching funds and committing to providing funding for ongoing services). Grants provided under this program fund a variety of community behavioral health facility types to treat individuals with varying levels of behavioral health needs. For example, funds could be used on (1) short‑term crisis treatment beds, (2) residential treatment facilities in which treatment typically lasts for a few months, or (3) longer‑term rehabilitative facilities. Certain portions of the total amounts discussed above for this program are set aside for more specific purposes or targeted at more specific populations. For example, some funding is reserved for the establishment of mobile behavioral health crisis teams and for community behavioral health facilities targeted at children and youth.

Since Legislative Approval, DHCS Has Developed Funding Plan and Key Program Details. When BH‑CIP was approved, several key implementation details were not fully developed yet. These outstanding details concerned (1) the funding allocation plan, (2) what requirements local entities would need to meet to apply for and obtain funds, and (3) what the ultimate match requirement from local entities would be. Below, we discuss recent developments related to these key program details.

- Funding Allocation Plan. DHCS intends to make BH‑CIP grant funds available through six rounds. Under this schedule, funding through rounds one (focused on mobile crisis infrastructure) and two (focused on local planning activities) were made available in 2021. (DHCS awarded $138.8 million through round one and $1.5 million through round two.) For the later rounds, round three ($518.5 million) will be focused on launch ready projects, round four ($480.5 million) will be focused on children and youth facilities, and rounds five and six ($960 million combined) will be focused on priorities identified in DHCS’ behavioral health Continuum of Care assessment report. (We discuss this assessment report later in this brief.) This funding plan results in shifts in the estimated payment timing for BH‑CIP, such that less funding than initially anticipated will be distributed in 2021‑22 and more than anticipated will be distributed in 2022‑23. In addition, DHCS intends to apply regional caps to most BH‑CIP funding across the state. The program’s seven regions are (1) the Bay Area, (2) the Central Coast, (3) Los Angeles County, (4) the Sacramento Area, (5) the San Joaquin Valley, (6) Southern California, and (7) the remaining balance of the state. (These caps would be determined by these regions’ share of 2011 realignment funds for behavioral health.) However, DHCS will reserve 20 percent of the total funding for BH‑CIP to distribute at its discretion depending on ultimate statewide demand.

- Local Application Requirements. In order to obtain BH‑CIP funding, local entities will be required to participate in a pre‑application consultation on project readiness. (These consultations provide an opportunity to discuss, for example [1] identified local regulatory hurdles to creating new facilities and [2] how proposed projects would address local needs.) Following this, when applying for funds, local entities will be required to submit documentation of (1) control over the property to be acquired or rehabilitated (such as by providing a letter of intent that outlines the terms of a sale or lease contract), (2) approval for any necessary local permits, (3) adherence to behavioral health facility licensing requirements, (4) preliminary construction plans and time lines, (5) capacity to meet the local match requirement (further discussed below), and (6) engagement with the local community (including any necessary contracts to ensure that Medi‑Cal services are provided in facilities proposed for acquisition or construction). Local entities also will be required to share results from local behavioral health needs assessments (which inform which facility types they will prioritize) and how they intend for projects to advance racial equity.

- Local Match Requirement. The amounts that local entities will be required to provide as the match for BH‑CIP funding vary by applicant type. Specifically, (1) tribal entities will be required to provide a 5 percent match; (2) counties, cities, and nonprofits will be required to provide a 10 percent match; and (3) for‑profit or private organizations, in partnership with counties, will be required to provide a 25 percent match. In addition, under BH‑CIP, the local match can be provided in the form of cash or in‑kind contributions (such as land or existing structures) subject to approval from the state.

Behavioral Health Continuum of Care Assessment Report

DHCS Recently Released Assessment of Current Capacity for Behavioral Health Services Statewide. Given the increased state focus on behavioral health as a major policy issue, DHCS attempted to assess the current landscape for behavioral health services throughout the state (using a combination of available data and qualitative interviews with key behavioral health stakeholders). The findings from this assessment were released in January 2022 in a report titled “Assessing the Continuum of Care for Behavioral Health Services in California.” This report examines the statewide capacity to provide behavioral health services across the full spectrum of behavioral health care.

Assessment Intended to Shape State Funding Priorities for Behavioral Health, Including for Later Rounds of BH‑CIP. The administration intends to use the findings from its behavioral health assessment report to help inform state priorities for behavioral health going forward. For example, it has stated that the identified need for certain behavioral health facilities will inform the design of the later rounds of BH‑CIP (resulting in a targeting of BH‑CIP grant funds for behavioral health facility types for which statewide need is particularly acute).

In addition, as part of the CalAIM initiative, the administration plans to pursue a federal waiver opportunity—known as the Serious Mental Illness (SMI)/Serious Emotional Disturbance (SED) demonstration opportunity—to potentially receive federal reimbursement for services provided to individuals with severe mental illness that are normally not eligible for federal funding. In order to gain approval from the federal government for this waiver opportunity, the state will need to build out necessary behavioral health infrastructure to address identified statewide gaps for community behavioral health care. DHCS’ behavioral health assessment report is intended to help inform what specific additional investments will be made going forward to fill these gaps in community care.

Behavioral Health Assessment Report Identifies Key Gaps in Continuum of Care, Including for Bridge Housing… As discussed, DHCS’ behavioral health assessment report concerns the statewide capacity to provide behavioral health services across the full spectrum of behavioral health care. (For example, it includes an assessment of statewide capacity for outpatient behavioral health care, crisis behavioral health care, and inpatient behavioral health care, among other types of behavioral health treatment.) Notably, this assessment report also includes a discussion of the landscape for housing options available to individuals with behavioral health disorders (including short‑term housing options such as bridge housing). To assess the need for housing options for individuals with behavioral health needs, the report relies on qualitative focus group interviews with key behavioral health stakeholders. The majority of participants in these focus group interviews identified a need for additional housing options for people with behavioral health disorders (including in certain state‑licensed facilities that can be used as a bridge housing option).

…But Does Not Provide Estimate of Additional Bridge Housing Beds Needed. While the assessment report provides some information on the current number of housing options (including bridge housing) for individuals with behavioral health needs, it does not provide an estimate of what additional housing capacity is necessary.

Proposal

$1.5 Billion General Fund One Time for Counties and Tribes to Provide Bridge Housing Options for Individuals Experiencing Homelessness With Significant Behavioral Health Needs. The Governor’s budget proposes $1 billion General Fund in 2022‑23 and $500 million General Fund in 2023‑24 to be distributed to counties and tribes to provide bridge housing that includes behavioral health services for people experiencing unsheltered homelessness with significant behavioral health needs. The funding would be administered by DHCS through BH‑CIP. This funding is intended to provide immediate bridge housing options for this population until the longer‑term housing and behavioral health facilities authorized as part of the 2021‑22 budget come online.

Funding Could Be Used to Purchase and Install Tiny Homes, Secure Beds in Existing Bridge Housing Settings, or Provide Behavioral Health Services. The administration indicates that counties and tribes could use this proposed funding to (1) purchase and install tiny homes to serve as bridge housing units, (2) secure bridge housing for individuals experiencing homelessness with significant behavioral health needs in existing housing settings—such as board and care facilities, and (3) provide time‑limited behavioral health services in these tiny homes or in other existing bridge housing settings.

Assessment

Further Specifics of the Proposal Needed to Fully Assess Its Merits. Further details are necessary to fully evaluate this proposal. For example, these details include specifics about (1) how available funds would be targeted to regions of the state that experience more substantial need for behavioral health bridge housing; (2) how funds ultimately would be distributed to counties and tribes (for example, whether this proposal would be structured as a competitive grant program or include a formula‑based allocation); (3) what, if any, requirements counties and tribes would need to meet in order to obtain funds; (4) how funds would be prioritized between the construction of tiny homes and supporting existing bridge housing settings; and (5) what oversight and evaluation activities DHCS would conduct for the proposal.

Highly Conceptual Nature of Proposal and Lack of Trailer Bill Language Could Limit Legislative Input on Ultimate Design of Proposal. Given the highly conceptual nature of this proposal as submitted to the Legislature—which provides a broad purpose and a high‑level description of how funding could be used to meet that purpose, with many key details outstanding—we find that legislative approval of this proposal in its current form could limit the Legislature’s input on the ultimate design of this proposal. That is to say, key decisions governing the structure of this program likely would be ceded to DHCS to implement administratively. Compounding this issue, we understand that the administration does not plan to propose trailer bill legislation to implement this proposal (which would allow the Legislature to specify its intent and terms for this proposed funding).

Proposal Appropriately Targets Gap in Behavioral Health Treatment Continuum and Current State Homelessness Efforts… As discussed earlier, people experiencing homelessness who also struggle with behavioral health disorders particularly benefit from housing support that is paired with the provision of behavioral health services. In addition, while some existing state programs to address homelessness do provide bridge housing, these programs do not target individuals experiencing homelessness who also have behavioral health disorders (nor is there any established strategy as part of these programs to address the needs of this population). We also understand that, currently, people with significant behavioral health needs may not be able to access bridge housing options through existing state programs due to their needs, potentially making current broader homelessness programs inaccessible to this population. Furthermore, DHCS’ behavioral health assessment report identifies a need for additional bridge housing for this population. Given this proposal’s primary focus—providing short‑term immediate housing combined with a suite of behavioral health services to stabilize people experiencing unsheltered homelessness in advance of moving into long‑term housing—we find that this proposal appropriately targets a gap in current state homelessness and behavioral health efforts.

…But Extent of Gap and Degree to Which Proposal Fills Gap Is Unclear. Although we find that this proposal is appropriate in its focus on behavioral health bridge housing, the ultimate number of additional bridge housing units needed to meet statewide need—both in the short and longer term—is unclear. Furthermore, the administration has not provided an estimate of how many additional bridge housing units would be created if this proposal is approved.

Ensuring Duration of Bridge Housing Stays Aligns With Ultimate Availability of Longer‑Term Housing Options Is Critical. The administration has indicated that this proposal is intended to provide immediate bridge housing to people experiencing unsheltered homelessness and who suffer from behavioral health disorders for a limited period of time until more permanent housing options are available (such as those permanent options funded through recent state investments). We find that ensuring that the ultimate duration of bridge housing stays aligns with the availability of permanent housing is critical. If these longer‑term housing options are not ready by the time individual stays in this bridge housing end, these individuals may face unsheltered homelessness again and bridge housing units may not be vacated in time to accommodate additional individuals.

Existing Homelessness Programs May Have Greater Capacity to Provide Immediate Homelessness Relief. BH‑CIP is a relatively new state program, and it took some time for DHCS to develop key program details and ultimately make funding available for new behavioral health facilities. In addition, only a fraction of the total funding for the program has been distributed to local entities thus far. Although the intent of this proposal is to make funding available immediately for behavioral health bridge housing, the additional capacity DHCS has to immediately develop key program modifications to BH‑CIP (if necessary) and ultimately disburse the proposal’s funds to counties is unclear. Accordingly, existing state homelessness programs—such as the Roomkey or Community Care Expansion (CCE) programs—may have greater capacity to deploy bridge housing more immediately. Moreover, some of these programs have more experience making housing options available for individuals experiencing homelessness on a short‑term basis. A modification or expansion of these existing programs—to target bridge housing at individuals with behavioral health needs—could result in more immediate relief for this population.

Tiny Homes Are Potentially Promising, but Present Trade‑Offs. Tiny homes are a potentially promising approach to providing bridge housing to individuals with behavioral health needs. However, they present trade‑offs when compared to other approaches to providing bridge housing. Below, we discuss tiny homes and these trade‑offs in further detail.

- Trade‑Offs of Tiny Homes as Approach for Addressing Homelessness. While there is no standard definition for what constitutes a tiny home, this term is often used to refer to a small house typically under 400 square feet in size. These houses vary in their construction design and what amenities they contain. While they can be built relatively quickly compared with traditional housing units, whether they are suitable for longer‑term housing is unclear. Tiny homes also do not necessarily have the same land requirements as multifamily housing units, but their placement still raises land use challenges and moreover typically do not result in housing density. Tiny homes may be suitable as a component of the state’s homelessness response, but whether they could be used at a large scale is unclear.

- Trade‑Offs of Tiny Homes as Component of This Proposal. As a bridge housing option (intended to house an individual temporarily until a permanent housing unit is available), tiny homes may make sense, as they can fulfill an immediate priority to house people experiencing unsheltered homelessness in a stable environment due to their relatively fast construction time and lower cost when compared to conventional housing. Whether this approach could be scaled up for the purposes of this proposal, however, is unclear. Counties likely would face challenges in the timely acquisition and placement of relatively large numbers of these units. Consequently, whether this approach would be significantly faster than using existing infrastructure or funding the acquisition or construction of new units is unclear. Moreover, there likely will be ongoing needs for bridge housing—as opposed to a one‑time need. While tiny homes could be more mobile, whether they could be maintained over time to support ongoing transitions to permanent housing is unclear.

Strategy for Overcoming Local Opposition to Tiny Homes May Be Needed. As discussed, we understand that local jurisdictions have experienced challenges related to local opposition to the construction and placement of tiny homes for people experiencing homelessness. The Governor’s proposal does not include a state‑level strategy for navigating this potential local opposition or how tiny homes should be distributed (whether by consolidating many tiny homes in specific locations or distributing them throughout jurisdictions). Without a clearly articulated strategy for doing so, we find that this proposal’s capacity to make additional tiny homes available for people experiencing homelessness with behavioral health needs may be significantly diminished.

Local Capacity to Continue Behavioral Health Bridge Housing Supports After Exhaustion of State Funding Is Unclear. The Governor’s proposal would provide funding for behavioral health bridge housing on a limited‑term basis in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24. While the behavioral health bridge housing options funded by the proposal are intended to serve as a temporary housing option until longer‑term housing options funded by other state investments come online, there likely would be some need to continue operating these bridge housing settings once state funding is exhausted. If counties and tribes elect to continue operating these behavioral health bridge housing options, they would need to do so using alternative funding sources. Accordingly, what capacity counties and tribes have to use alternative funding sources to continue operating these housing options is unclear.

How Proposal Would be Coordinated With Implementation of New CalAIM Benefits Is Unclear. As discussed earlier, in addition to reforms intended to broadly increase access to Medi‑Cal behavioral health services, the CalAIM initiative includes the addition of a new ECM benefit for individuals experiencing homelessness who also struggle with behavioral health disorders. CalAIM also includes the addition of several new Community Supports benefits that provide housing‑related services and time‑limited housing payments for this population. The administration has not provided a clear strategy for how the provision of the ECM and Community Supports benefits would be coordinated with the availability of behavioral health bridge housing units funded by this proposal. For example, this coordination could include a plan for ensuring that (1) Medi‑Cal managed care plans—tasked with providing these new CalAIM benefits—would provide these benefits on‑site at behavioral health bridge housing units operated by counties and tribes and (2) CalAIM housing navigation services would be provided to individuals in these units to support these individuals locating and securing permanent housing.

Proposal May Increase Likelihood of Federal Approval for Key CalAIM Demonstration Opportunity. As discussed earlier, in order to gain approval from the federal government for the SMI/SED demonstration opportunity—to receive federal reimbursement for services provided to individuals with severe mental illness that are normally not eligible for federal funding—the state will need to build out necessary behavioral health infrastructure to address identified statewide gaps for community behavioral health care (such as those identified in DHCS’ behavioral health assessment report). The activities funded by this proposal—providing behavioral health bridge housing to individuals experiencing unsheltered homelessness with significant behavioral health needs—could be considered by the federal government as evidence of this commitment and help contribute to the state’s application for this demonstration opportunity.

Recommendations

Consider Trade‑Offs Between Proposal and Modifications to Existing Homelessness Programs. As discussed earlier, we find that existing state homelessness programs—such as the Roomkey program—may have greater capacity to deploy bridge housing more immediately. Accordingly, the Legislature may wish to consider the trade‑offs between the Governor’s proposal—which would provide additional funding to BH‑CIP (which has still not disbursed the majority of its existing funds, which are focused on a related, but different, purpose)—and modifying or expanding existing state homelessness programs to focus specifically on individuals who also have behavioral health needs.

Consider Planning Funds Instead for New State Approaches. Developing novel approaches to provide bridge housing very likely will take time. For instance, the construction and placement of tiny homes as bridge housing would be a new state activity (in contrast to securing beds in existing housing facilities) and likely would be new for some counties and tribes as well. Given this, developing a plan for the disbursement of funds to counties and tribes for this specific purpose may take time. Moreover, counties’ and tribes’ ability to deploy these resources also would take time. Should the Legislature wish to move forward with the approach to construct tiny homes—or some other novel approach—to meet the state’s bridge housing needs, it may wish to consider providing planning funds to the state and local governments (while still providing funds to secure bridge housing in existing settings).

If Legislature Approves of Proposal in Concept, Ensure Input on Ultimate Design of Program Through Trailer Bill. As discussed earlier, given the highly conceptual nature of this proposal, we find that legislative approval of this proposal in its current form could limit the Legislature’s input on the ultimate design of bridge housing. To help ameliorate this issue, we recommend the Legislature adopt trailer bill language to govern the implementation of this program and provide more opportunities for oversight. Below, we provide some examples of key program details, including oversight provisions, that this trailer bill language could address:

- Additional Details About Proposal’s Program Design. Trailer bill language for this proposal could specify additional details about program design. These additional details could include, for example, (1) what requirements counties and tribes would need to meet in order to obtain funding and (2) how funding would be prioritized for different regions of the state.

- Appropriate Balance Between Prioritizing Tiny Homes and More Established Bridge Housing Options. As discussed earlier, we find the construction of tiny homes a promising, yet relatively new, approach to filling the need for bridge housing. Trailer bill language could delineate the appropriate balance of funding to be provided towards this purpose relative to securing bridge housing in existing facilities.

- Strategy for Navigating Local Opposition to Construction of Tiny Homes for People Experiencing Homelessness. Trailer bill language could provide direction on how to navigate potential local opposition to the construction of tiny homes, such as by streamlining local approval requirements or requiring counties and tribes to demonstrate community engagement in the decision to pursue tiny homes for behavioral health bridge housing.

- Allocation Methodology. Trailer bill language could specify what the allocation methodology for this behavioral health bridge housing should be. For example, this language would specify whether the proposal would be implemented as a competitive grant program (which may result in more sustainable models by requiring counties and tribes to demonstrate their capacity to operate these bridge housing settings on a longer‑term basis) or be subject to a formula‑based allocation formula to counties and tribes (which may result in funds being distributed more quickly).

- Long‑Term Planning. Trailer bill language could specify how bridge housing should be targeted to meet immediate needs, as well as how assets purchased under the program should be maintained to provide ongoing options. As there likely is a need for ongoing bridge housing supports, statute could lay out the Legislature’s longer‑term vision for this intervention.

- Oversight, Evaluation, and Reporting Requirements to the Legislature. Trailer bill language could specify what oversight and evaluation activities the administration would conduct for this proposal after funds are distributed to counties and tribes. It also could specify what information—and with what frequency—the administration would be required to provide to the Legislature (such as the number of individuals successfully transitioned to permanent housing or who have received the new Medi‑Cal services created under CalAIM).

IST Workgroup Solutions Package

Background

Felony ISTs and the Waitlist. Currently, counties are responsible for almost all mental health treatment for low‑income Californians with severe mental health needs. One exception, however, is treatment for individuals found IST and who face a felony charge (we refer to these individuals as “felony ISTs”). Felony ISTs typically are referred by a state trial court to DSH to receive treatment. The state treats the majority of felony ISTs in state hospitals; however, many individuals wait in county jails for many months given the limited number of DSH beds, which has resulted in a waitlist of felony ISTs who have not been admitted to DSH. The treatment provided to felony ISTs—known as “competency restoration treatment”—differs from general mental health treatment. The objective of competency restoration treatment is to treat a felony IST until they are competent enough to face their criminal charge, rather than provide comprehensive treatment for an underlying mental health condition. While the state is responsible for treating felony ISTs, counties are responsible for treating misdemeanor ISTs.

DSH Received Funding Augmentations in Recent Years to Treat Felony ISTs, Including Through Contracts With Counties. To increase capacity for felony IST treatment, in prior years, DSH has received funding to both (1) expand bed capacity in state hospitals and (2) contract with counties to provide competency restoration treatment to felony ISTs who do not require the higher level of care that state hospitals provide. When contracting with counties, DSH still retains responsibility for felony IST treatment, but provides funding to counties to treat felony ISTs on its behalf. County‑provided IST felony treatment includes (1) the establishment of Jail‑Based Competency Treatment programs, in which competency restoration treatment is provided to felony ISTs while they are in county jails; (2) Community‑Based Restoration (CBR) programs, in which counties receive funding to provide competency restoration treatment in a variety of community behavioral health treatment settings; (3) the DSH Conditional Release Program (CONREP), in which supervised felony ISTs reside in the community and receive outpatient mental health treatment; and (4) IST diversion programs, in which courts can refer felony ISTs (or those likely to be found IST) to mental health treatment in exchange for dropped or reduced charges upon completion of the mental health program. These county treatment options have resulted in some reduction in the pressures DSH faces to find treatment capacity for felony ISTs. (For example, as of June 2021, 458 individuals were referred to county mental health treatment programs as part of the DSH IST diversion program, rather than a state hospital bed.) In 2019, county‑based competency restoration programs served roughly 2000 felony ISTs compared to about 4000 treated in state hospitals.

In addition, the 2021‑22 budget included $267.1 million General Fund in 2021‑22—ramping down to $145.5 million General Fund in 2024‑25 and ongoing—for DSH to contract with counties for (and for the department to subsequently oversee) additional treatment bed capacity in the community. DSH has begun to engage with counties on securing contracts for this funding, but has not disbursed any funds yet.

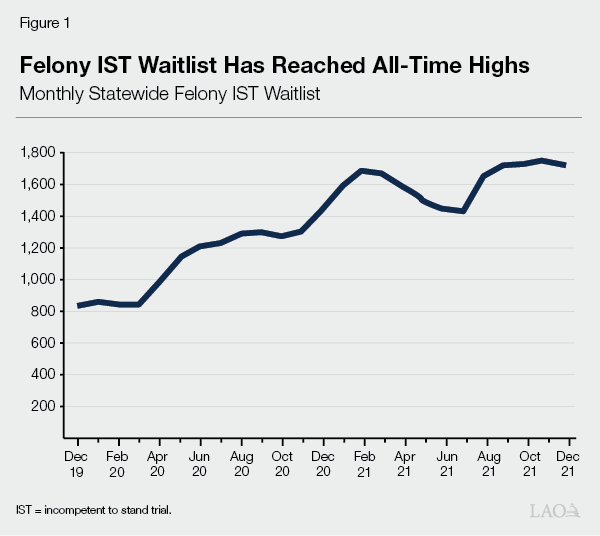

Felony IST Waitlist Has Reached All‑Time Highs. Prior to the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic, the number of felony ISTs on the waitlist for competency restoration was typically around 800 individuals. Since the initial months of the pandemic, the number of felony ISTs on the waitlist has grown to over 1,700 individuals as of December 2021 (with an average wait time for treatment exceeding 100 days). Figure 1 illustrates growth in the felony IST waitlist since December 2019.

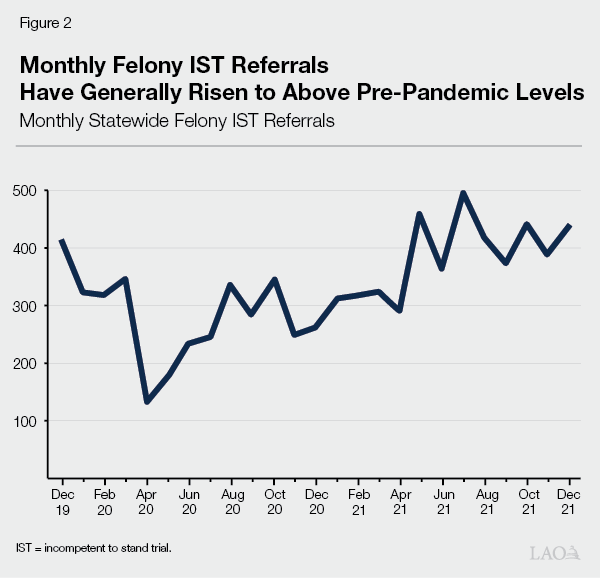

After Brief Dip Due to COVID‑19, Monthly Felony IST Referrals Generally Have Risen to Above Pre‑Pandemic Levels. In prior years, DSH experienced gradually rising felony IST referrals for competency restoration treatment. The average number of felony ISTs referred per month increased by roughly 20 percent between 2015‑16 and 2018‑19. However, in response to the COVID‑19 pandemic, DSH imposed a suspension of all admissions into state hospitals in the initial months of the pandemic. This, combined with reduced capacity in local court systems due to COVID‑19‑restrictions, led to a decline in the number of felony IST referrals as shown in Figure 2. (For example, from March 2020 to April 2020, referrals declined 62 percent.) DSH continued to experience lower numbers of felony IST referrals until August 2020, after which time COVID‑19‑related restrictions limiting referrals generally were lifted. (The department did later suspend admission of certain patients from January 2021 to February 2021.) For the months since then, the number of felony IST referrals generally has risen to above pre‑pandemic levels, as shown in Figure 2. In part, this rise reflects the backlog of cases resulting from pandemic‑related restrictions.

Stiavetti v. Clendenin. In 2016, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit against DSH alleging that the constitutional rights of felony ISTs were being violated due to DSH failing to place felony ISTs into competency restoration treatment in a timely manner. A California Superior Court ruled that felony ISTs have a constitutional right to competency restoration services within a reasonable period of time, and found that DSH had violated this right by failing to secure treatment for felony ISTs in a timely manner. Accordingly, the superior court required DSH to place felony ISTs into competency restoration treatment within 28 days. DSH appealed this ruling to the California Supreme Court, but the department’s appeal was denied in 2021. DSH is now required to provide competency restoration treatment for felony ISTs according to a phased‑in schedule of (1) within 60 days by August 2022, (2) within 45 days by February 2023, (3) within 33 days by August 2023, and (4) within 28 days by February 2024. If DSH is unable to meet these specified requirements, the department potentially could be subject to substantial fines or placed under federal receivership.

IST Solutions Workgroup. 2021‑22 budget‑related legislation established a workgroup—appointed by the California Health and Human Services Agency (CalHHS) Secretary—that convened last fall and developed short‑, medium‑, and long‑term solutions to address the growing felony IST waitlist. As required by statute, these solutions were submitted to CalHHS on November 30, 2021. The 2021‑22 budget package also authorized the Department of Finance to increase the DSH budget by up to $75 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and provided $175 million General Fund in 2022‑23 and ongoing to implement solutions identified by the workgroup. If the identified IST solutions are unable to be implemented, the budget‑related legislation authorizes DSH to (1) discontinue admissions for certain non‑IST patients (in order to prioritize competency restoration), (2) impose patient reduction targets, and/or (3) charge a premium bed rate to counties that refer greater numbers of felony ISTs to the department.

Proposal

The Governor’s budget reflects a funding set‑aside for a proposed package of select IST solutions developed by the IST solutions workgroup (accompanied by trailer bill language to implement these solutions). We understand that the administration intends to revise this proposed package based on legislative and stakeholder feedback, and update the proposed package at May Revision with this funding reflected in the DSH budget. Below, we describe the initially proposed package of select IST solutions.

Additional $317 Million General Fund One Time and $33.6 Million General Fund Ongoing to Implement IST Solutions Package. The Governor counts a total of $93 million General Fund in 2021‑22 (of which $66.4 million is one time and $26.6 million is ongoing) and $571.6 million General Fund in 2022‑23 (of which $233 million is one time and $338.6 million is ongoing) as funding in support of the initially proposed IST solutions package. This total amount reflects both (1) additional proposed funding of $317 million General Fund one time and $33.6 million General Fund ongoing in 2022‑23 and (2) $93 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $221 million General Fund in 2022‑23 in already authorized funding (both to implement the solutions developed by the IST solutions workgroup and for activities within existing DSH programs that the administration now considers as IST solutions). We describe all the components of the proposed IST solutions package (with all funding to be provided to DSH) below in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Proposed IST Workgroup Solutions Package

General Fund (In Millions)

|

2021‑22a |

2022‑23a |

||||

|

Previously |

Newly |

Previously |

Newly |

||

|

Solutions Focused on Early Stabilization and Community Care Coordination |

|||||

|

Provide early treatment upon arrival in jail |

$24.9 |

— |

$38.5 |

$28.3 |

|

|

Improve patient tracking and case management |

1.7 |

— |

— |

4.9 |

|

|

Solutions Focused on Expanding Capacity for CBR and Diversion Programs |

|||||

|

Provide housing to felony ISTs |

$60.0b |

— |

— |

— |

|

|

Acquire or renovate residential housing facilities for felony ISTs |

6.4b |

— |

$46.0b |

$187.0b |

|

|

Create additional CBR and diversion programs or expand existing programs |

— |

— |

136.5 |

130.0b |

|

|

Solutions Focused on Facilitating Increased Placements to CONREP |

|||||

|

Pilot independent panel to determine CONREP placement |

— |

— |

— |

$0.4c |

|

|

Totals |

$93.0 |

— |

$221.0 |

$350.6 |

|

|

aAll amounts ongoing unless otherwise noted. bOne time. c$1.2 million in 2023‑24 and ongoing. |

|||||

|

IST = incompetent to stand trial; CBR = Community‑Based Restoration; and CONREP = Conditional Release Program. |

|||||

IST Workgroup Solutions Package Priorities. Below, we describe the major priorities reflected in the Governor’s proposed IST solutions package.

- Providing Housing for Felony ISTs. We understand that one of the major barriers—identified by the IST solutions workgroup—to ensuring that felony ISTs have access to community‑based treatment programs is a lack of available housing options for this population. To that end, the proposed IST solutions package includes a combined $66.4 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $233 million General Fund in 2022‑23 one time to increase housing availability for felony ISTs. Specifically, this funding would support (1) securing housing for felony ISTs in existing facilities and (2) investing in housing infrastructure for felony ISTs participating in community‑based programs by acquiring and renovating properties to house felony ISTs.

- Expanding or Creating New Community‑Based Treatment Programs. The proposed IST solutions package also includes $266.5 million General Fund in 2022‑23 and ongoing to expand or create new community‑based—meaning CBR or diversion—felony IST treatment programs.

- Providing Stabilization and Early Access to Treatment for Felony ISTs. We understand that another of the major barriers—identified by the IST solutions workgroup—to referring felony ISTs to any of the various alternatives to treatment within a state hospital is a lack of early mental health treatment and stabilization (including by administering medication) as soon as an individual is booked into jail. To that end, the proposed IST solutions package includes $24.9 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $66.8 million General Fund in 2022‑23 to provide early mental health treatment and medications for felony ISTs to increase the number of individuals eligible for community‑based treatment programs (and reduce the number of felony ISTs in need of a state hospital bed).

- Improving Patient Tracking and Case Management. As a result of expanding the suite of community‑based treatment options available for felony IST treatment, DSH has identified a need to improve its capacity for patient tracking and case management. Accordingly, the proposed IST solutions package includes $1.7 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $4.9 million General Fund in 2022‑23 and ongoing to enhance these functions. Specifically, this funding would support (1) teams to screen all IST patients to determine appropriate placement, (2) case management for felony ISTs, (3) development of a statewide transportation contract to facilitate appropriate placement for felony ISTs, and (4) improved capacity to collect patient data.

- Increasing CONREP Placement. To increase the number of felony ISTs placed into CONREP (furthering the goal of increasing community‑based treatment for felony ISTs), the proposed IST solutions package includes $433,000 General Fund in 2022‑23 and $1.2 million General Fund in 2023‑24 and ongoing to pilot a new independent panel that would use a revised assessment process to determine CONREP eligibility.

Proposed Package Includes Cap on Felony IST Referrals From Counties, With Cost‑Sharing for Counties That Exceed Cap. The proposed IST solutions package includes a cap on the total number of felony IST referrals from each county, with a requirement that counties share in the cost of treatment for felony ISTs referred to DSH in excess of the cap. (This proposed cap was not developed as part of the IST solutions workgroup and originates from the administration.) These county caps would be set at the number of felony ISTs referred from each county in 2021‑22. While forthcoming additional trailer bill language to implement the proposed IST solutions package may provide further details on the specific cost‑sharing methodology, DSH has indicated that county shares of cost would depend on what DSH determines the appropriate treatment settings for felony ISTs referred to the department are. (For example, county shares of cost would differ for felony ISTs placed in CBR programs and felony ISTs placed in a state hospital.)

Bulk of Funding for Proposed Package Excluded From State Appropriations Limit (SAL). The SAL constrains how the state can spend revenues that exceed a specific threshold. Appropriations required to comply with federal government or court mandates are excluded from the SAL. Accordingly, funding within the DSH budget intended to provide competency restoration treatment to felony ISTs in a timely manner (in response to court rulings) can be excluded from the SAL. Within the proposed IST solutions package, the administration considers $75 million General Fund in 2021‑22 (reflecting already authorized funding) and $525 million General Fund in 2022‑23 (reflecting both already authorized and newly proposed funding) as excluded from the SAL for this reason.

Assessment

Some Proposed Trailer Bill Language Not Yet Available for Review. The administration has proposed trailer bill language to implement the proposed IST solutions package. However, language surrounding the proposed cost‑sharing methodology for counties (that exceed the proposed cap on felony IST referrals to DSH) is not yet available for review in order to assess this component of the proposed package.

Priorities Reflected in Solutions Package Appropriately Target Gaps in Current Felony IST Treatment Continuum and Are Reasonable... We find the selected IST solutions included in the proposed package to be reasonable, as they appropriately target key barriers to increasing the number of felony ISTs receiving community‑based treatment, which would help DSH commence treatment for felony ISTs in a timely manner in accordance with court orders. For example, lack of available housing and a need for stabilization and early treatment for felony ISTs were identified by the IST solutions workgroup as key priorities for addressing the substantial backlog of felony ISTs awaiting treatment.

…But Further Efforts Are Needed to Address Underlying Factors for Number of Felony IST Referrals. Although we find that the selected IST solutions included in the Governor’s proposed package are reasonable, we also find that further efforts are needed to address the underlying factors that impact the number of felony ISTs statewide. Specifically, the selected IST solutions in the proposed package seek to facilitate greater capacity for treatment of existing felony ISTs, rather than seek to address the underlying factors that determine the number of future felony ISTs. Addressing these underlying factors would require providing treatment for individuals’ underlying mental health needs prior to the point at which they commit an offense that could render them IST. Although the Governor’s approach to provide greater treatment capacity for existing felony ISTs would help DSH meet court‑ordered time frames for commencing treatment for felony ISTs, we find that addressing these underlying factors is important to reduce the rate at which individuals are found to be IST in the first place.

Initial Workgroup Efforts on Addressing These Underlying Factors Are Promising. As discussed earlier, reducing the number of future felony ISTs requires providing mental health services to an individual in advance of them committing an offense. In California, other state entities besides DSH are tasked with overseeing the provision of overall mental health services. In particular, counties play a key role in the provision of mental health services as they have primary responsibility for providing mental health treatment for individuals with the most severe mental health needs. Accordingly, efforts to reduce the number of future felony ISTs will require significant coordination with these other state entities and counties to ensure that adequate mental health services are provided to people with severe mental health needs.

We find that a few ideas developed by the IST solutions workgroup—while still in a very conceptual stage—appear promising in this regard. For example, we understand that the IST solutions workgroup discussed (1) how to improve transition planning for individuals leaving DSH treatment programs to ensure that they are linked with county services, (2) the inclusion of justice‑involved individuals as a population of focus in the administration of broader state homelessness and behavioral health programs such as the CCE program and BH‑CIP, (3) how to ensure that justice‑involved individuals have access to new Medi‑Cal benefits available under the CalAIM initiative, and (4) how to leverage broader state funding for behavioral health workforce development programs to ensure an adequate behavioral health workforce that focuses on the needs of justice‑involved individuals.

County Referral Cap May Make Sense, but Local Capacity to Stay Under Cap Unclear. The proposed package’s inclusion of a cap on the number of felony ISTs counties can refer to DSH may make sense, as it could incentivize counties to partner with DSH on the set of IST solutions included in the package. Counties have some ability—by increasing the availability of county mental health services—to help reduce the number of felony ISTs referred to DSH, but the determination of IST status also depends on court proceedings that are not directly tied to the ultimate availability of county mental health services. Accordingly, what control counties have over the ultimate number of felony ISTs referred to DSH is unclear. Moreover, while counties could impact future IST referrals through enhanced mental health services, they cannot directly impact the existing waitlist.

Proposed County Referral Cap Raises Reimbursable Mandate Questions. The State Constitution generally requires the state to reimburse local governments for the costs of a “new program” or “higher level of service” (when imposed by the state). While determining whether certain requirements are state reimbursable mandates can be complex, generally if the state requires local governments to provide a new governmental program, the state is required to reimburse those costs. Although counties have primary responsibility for providing mental health services to individuals with the most severe needs, the state is responsible for treating felony ISTs. Consequently, the administration’s proposal to require counties to pay a share of cost for felony IST treatment above a particular level (the cap) likely would impose a new requirement on counties that could be found to be a state reimbursable mandate.

Ongoing Funding for Independent Panel Pilot Is Premature. The Governor is proposing to fund the independent panel pilot (to facilitate increased placement in CONREP) on an ongoing basis prior to the state being able to assess whether it has been successful at achieving this goal. As a result, providing ongoing funding for this pilot prior to making these assessments is premature.

Additional Funding in Proposed Solutions Package and in Overall DSH Budget May Be Eligible for Exclusion From SAL. As discussed earlier, the administration considers the bulk of funding within the proposed IST solutions package as excluded from the SAL (as this funding is intended to address the substantial backlog of felony ISTs awaiting treatment, in accordance with court rulings). However, we find that the remaining funding within the IST solutions package—specifically the already authorized funding for existing DSH community‑based programs—may also be eligible for exclusion from the SAL. This is because these existing programs also are intended to help address the substantial backlog of felony ISTs awaiting treatment in line with court requirements. Furthermore, the overall DSH budget includes a substantial amount of funding to increase capacity for felony IST treatment in order to address the substantial felony IST waitlist—including funding to establish or expand capacity for felony ISTs within county jails—that also may be eligible for exclusion from SAL for court mandate reasons.

Recommendations

Use Budget Process to Provide Legislative Input on Package. As discussed earlier, we understand that the administration plans to revise the proposed IST solutions package based on stakeholder and legislative feedback and provide an updated version of the package at May Revision (reflecting funding for the proposed package within the DSH budget). We recommend that the Legislature use the budget process to provide input on the proposed IST solutions package given this opportunity to make adjustments to the proposal. This input could include the addition of other solutions developed by the IST solutions workgroup that were not included in the Governor’s proposed package, for example.

Monitor Status of Other Promising Ideas From IST Workgroup. As discussed earlier, the IST solutions workgroup included a discussion of additional ideas beyond the specific set of solutions included in the Governor’s proposed package. These additional ideas, while still very conceptual, appear to show promise in that they seek to address the underlying factors that impact whether individuals are found IST in the first place. We recommend that the Legislature monitor the status of these additional ideas and their potential development into additional IST solutions for DSH or counties to implement at a later time.

Provide Limited‑Term Funding for Independent Panel Pilot. Given that we find the proposed ongoing funding for the independent panel pilot (to facilitate greater placement in CONREP) to be premature, we recommend the Legislature instead provide limited‑term funding for this pilot until its effectiveness can be assessed.

Direct Administration To Explore Counting Additional DSH Funding as Excluded From SAL. As discussed earlier, we find that additional funding within the proposed IST solutions package and within DSH’s overall budget may be eligible for exclusion from the SAL (given that these other activities also are intended to bring DSH in compliance with court mandates). Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature direct the administration to explore the feasibility of counting this additional DSH funding as excluded from the SAL.

New Medi‑Cal Mobile Crisis

Intervention Services Benefit

Background

Mobile Crisis Intervention Services. While there is no standard definition for what constitutes mobile crisis intervention services, the main objective of mobile crisis intervention services is to rapidly provide behavioral health services to individuals experiencing a behavioral health—including mental health or SUD—crisis in the community. The exact model for how this service delivery occurs varies, but generally, mobile crisis intervention services are provided by “mobile crisis teams” of trained behavioral health professionals that are deployed in the community to meet an individual wherever they are experiencing crisis. The specific services provided by these teams also may vary, but generally can include (1) behavioral health assessments, (2) behavioral health services to stabilize an individual experiencing crisis, and in some cases (3) the provision of necessary medications. Mobile crisis teams also can provide referrals and warm handoffs to necessary follow‑up care for individuals after their immediate crisis, and also may provide an alternative to law enforcement engagement for an individual experiencing a behavioral health crisis.

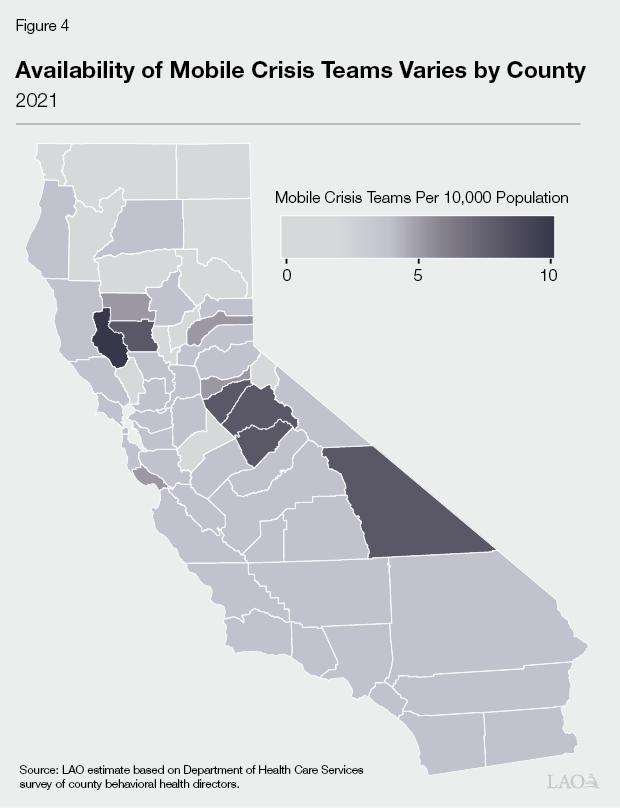

Availability of Mobile Crisis Teams Throughout the State Varies. In California, counties play a major role in the funding and delivery of public behavioral health services. In particular, counties generally are responsible for arranging and paying for community behavioral health services for low‑income individuals with the highest service needs. Accordingly, to the extent that mobile crisis intervention services are provided in California, they are provided by counties rather than the state. Counties generally have some degree of discretion over what behavioral health programs they elect to operate (with some exceptions which we discuss later). Due to this, counties have discretion over whether to establish mobile crisis teams for the provision of mobile crisis intervention services. This leads to the availability of mobile crisis teams varying by county, as shown in Figure 4.

Funding for Mobile Crisis Intervention Services. Counties receive a variety of dedicated revenue streams (which they generally can flexibly make use of) to fund their behavioral health programs. Accordingly, counties may choose to use these dedicated revenues to fund mobile crisis intervention services. In particular, we understand that counties that elect to fund mobile crisis intervention services do so using their dedicated MHSA revenues. In addition to these dedicated revenues, there are a few state programs that make available grant funding to counties to support infrastructure development for mobile crisis intervention services. These state programs include (1) the Investment in Mental Health Wellness Act of 2013 Grant Program and (2) DHCS’ Crisis Care Mobile Units program (which is funded with the portions of BH‑CIP that are earmarked for mobile crisis services). We understand that some counties have applied for and received funds for mobile crisis intervention services infrastructure through these programs. Furthermore, counties currently can obtain federal reimbursement for certain mobile crisis intervention services through Medi‑Cal. (We discuss the relationship between county mobile crisis intervention services and the Medi‑Cal program further in the following section.)

Mental Health Crisis Intervention Services in Medi‑Cal. As discussed earlier, counties generally have some degree of discretion over what behavioral health programs they elect to operate. However, counties are required to provide certain behavioral health services that are part of the Medi‑Cal program. Of these required Medi‑Cal behavioral health services, counties are required to provide mental health crisis intervention services (including the provision of assessments and mental health services to stabilize an individual experiencing crisis). Medi‑Cal crisis intervention services may be provided anywhere in the community. However, counties are not required to make these crisis intervention services available through mobile crisis teams. Should counties provide these Medi‑Cal crisis intervention services in the community through mobile crisis teams, they may obtain federal reimbursement for these service costs.

American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARP Act) Mobile Crisis Intervention Services Option. The ARP Act makes available an option for states to add qualifying mobile crisis intervention services as a covered Medicaid benefit for a five‑year period. These qualifying mobile crisis intervention services have increased federal requirements relative to what counties currently can provide through Medi‑Cal, such as a requirement that services be available to Medi‑Cal beneficiaries 24/7 and be provided by a multidisciplinary mobile crisis team of behavioral health providers. In addition, the ARP Act provides an opportunity to receive enhanced federal funding—85 percent of costs—through Medicaid for these qualifying mobile crisis intervention services for a period of three years, after which these services would be reimbursed according to standard federal cost‑sharing rules.

Proposal

Add New Mobile Crisis Intervention Services to Medi‑Cal, on a Statewide Basis. The Governor proposes to add—beginning January 1, 2023—these new qualifying mobile crisis intervention services as a mandatory statewide benefit in the Medi‑Cal program for a five‑year period (with forthcoming trailer bill language to implement the proposal). The Governor’s proposal assumes that enhanced federal funding (of 85 percent of costs) would be available for three years, and that the new benefit would be reimbursed at standard federal cost‑sharing rules for the remaining two years. The total costs of adding this new benefit to the Medi‑Cal program are assumed to be $16.2 million General Fund ($108.5 million total funds) in 2022‑23, and over the five‑year period total costs are assumed to be $335 million General Fund ($1.4 billion total funds). The Governor’s proposed new Medi‑Cal services would be implemented by counties through their existing behavioral health delivery systems. Specifically, the proposal would add new benefits for mobile crisis intervention services to both counties’ mental health systems and SUD systems. (The new benefit in counties’ mental health systems would be distinct from the current Medi‑Cal mental health crisis intervention benefit.) We also understand that additional activities beyond just service costs would be eligible for federal reimbursement through these new benefits. Specifically, activities related to transportation and the idle time associated with being on‑call 24/7 also would be eligible for federal reimbursement. To that end, DHCS intends to develop a bundled payment rate that will account for all of these costs.

Assessment

Proposed Trailer Bill Language Not Yet Available for Review. The administration plans to propose trailer bill language to implement the Governor’s proposal to add these new qualifying mobile crisis intervention services to the Medi‑Cal program. However, this language is not yet available for review (to comprehensively assess the merits of the Governor’s proposal). Some additional details necessary to assess this proposal may be included in the forthcoming trailer bill language. (For example, the language could include further information about how statewide standards for these mobile crisis intervention services would be determined, or how the bundled payment rates for these services and associated activities would be developed.)

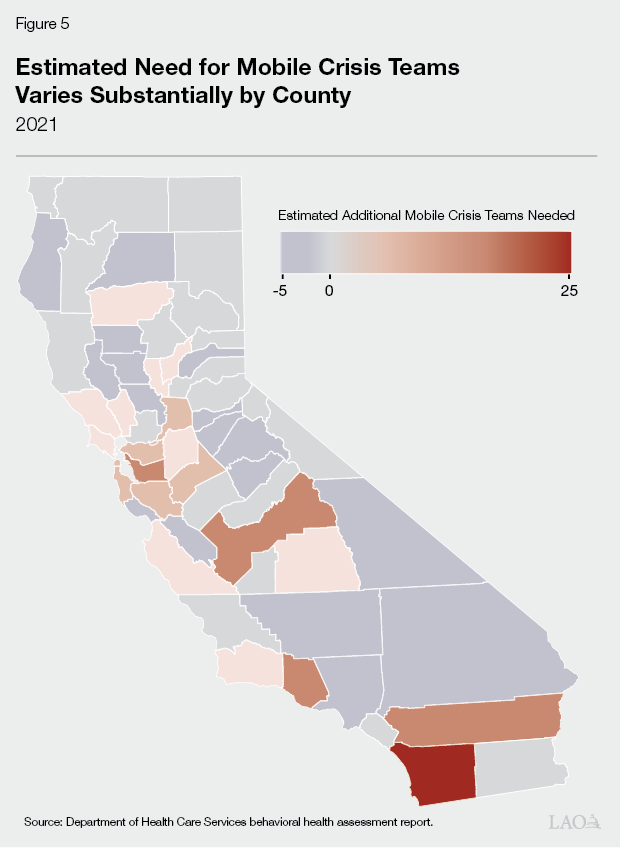

Proposal Appropriately Seeks to Address Gaps in Behavioral Health Crisis Continuum… We find that the Governor’s proposal to add new qualifying mobile crisis intervention services to the Medi‑Cal program appropriately seeks to address gaps in the behavioral health crisis continuum. As part of its behavioral health assessment report, DHCS also (using available data and qualitative interviews with key behavioral health stakeholders) examined the level of need for mobile crisis teams throughout the state. Key behavioral health stakeholders identified a need for additional mobile crisis teams. DHCS found that a significant number of counties did not operate any mobile crisis teams, and the counties that elected to operate teams did not have enough available to make mobile crisis services accessible 24/7.

…However, Gaps May Vary Substantially by County. As discussed earlier, the degree to which mobile crisis teams are available throughout the state varies by county. Although additional mobile crisis capacity is an appropriate priority overall, the degree of need for these teams varies by county. As part of its behavioral health assessment report, DHCS relied on the Crisis Resource Calculator—a tool developed by a national advocacy organization which aims to quantify the level of need for certain behavioral health treatment modalities—to estimate very roughly how many additional mobile crisis teams would be needed in each county to properly meet their need. (DHCS notes that these estimates are very rough and are not intended to be a precise estimate of the exact level of need in each county.) As shown in Figure 5, according to the Crisis Resource Calculator, this need may vary substantially by county.

Local Capacity to Meet Requirements of New Services Unclear. Whether the proposed statewide requirement to provide qualifying mobile crisis intervention services through Medi‑Cal would result in additional capacity for mobile crisis intervention services depends on whether there is sufficient local capacity to meet this requirement. We find that counties’ capacity to provide these new services (especially on a 24/7 basis) is unclear. For example, (1) counties may not have adequate behavioral health workforce to staff these new mobile crisis teams and (2) rural counties may experience difficulty ensuring 24/7 access to mobile crisis care in more sparsely populated areas.

How Will Best Practices be Included in Design of New Services? In addition to federal requirements surrounding the provision of these new qualifying mobile crisis intervention services, federal guidance also includes suggestions for best practices for mobile crisis services to be incorporated into states’ efforts to provide these new services. For example, it suggests that states consider ways (1) to minimize law enforcement involvement in the provision of mobile crisis services, and (2) coordinate with school systems to address youth‑specific needs. The administration has not yet provided information on its approach to incorporating these best practices into the Governor’s proposal.

Provision of New Mobile Crisis Intervention Services After Period Authorized by ARP Act Unclear. As discussed, the ARP Act provides states with the option to add these new mobile crisis intervention services to their Medicaid programs for a period of five years. The federal government has not provided information on whether these new Medicaid services would be allowed to continue beyond that time period. Although DHCS has expressed a willingness to continue these new Medi‑Cal mobile crisis interventions services on an ongoing basis, the administration has not proposed funding to do so. In addition, how the state would provide these new Medi‑Cal services on an ongoing basis (given that federal intent to allow this is uncertain) is unclear.

Recommendations

Gather More Information Before Taking Action on Proposal. While we think the Governor’s proposal in concept has a policy basis warranting serious consideration, we recommend that the Legislature gather more information about the proposal before taking action. This additional information could include, for example, (1) what the statewide standards would be for these mobile crisis services, (2) how payment rates would be determined, or (3) how best practices for mobile crisis teams would be incorporated into the state’s approach to providing these new services.

Consider Ways to Ensure Sufficient Local Capacity to Provide New Services. Given that we find that counties’ capacity to meet the requirements of these new Medi‑Cal services is unclear, we recommend that the Legislature consider ways to ensure that there is sufficient local capacity to provide these new services. If needed, the Legislature could consider making funding available to counties to develop the infrastructure needed to provide these services on a 24/7 basis. It also could explore ways to leverage workforce funding—including workforce funding proposed in the Governor’s budget—to ensure that there is sufficient staff to comprise these multidisciplinary mobile crisis teams.

Overarching Comments

Below, we provide some overarching issues for the Legislature to consider in its assessment of behavioral health proposals in general.