LAO Contact

August 8, 2022

Improving California’s

Unemployment Insurance Program

- Introduction

- California’s UI Program

- Why Is Getting UI Benefits Difficult?

- Signs of Imbalance in the UI Program

- Addressing State Practices That Make it Difficult to Get UI

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

California’s Unemployment Insurance (UI) program provides temporary wage replacement to unemployed workers. The program helps alleviate workers’ economic challenges and bolster the state economy during downturns. Despite its importance, the program faltered during the two most recent downturns. At the Employment Development Department (EDD)—which oversees UI—payments were delayed for roughly 5 million workers during the pandemic and phone lines were overwhelmed by frustrated callers. These failures caused hardship for unemployed workers and their families, held back the economy, and spurred frustration among Californians with their state government.

Recent Failures Trace Back to UI Program’s Basic Design. Recent failures can be traced back to the UI program’s basic design, which results in more emphasis being placed on minimizing fraud and business costs than making sure eligible workers can easily get benefits. Without safeguards to make sure eligible workers can get benefits easily, the state’s UI program has tilted out of balance. During normal economic times, this emphasis leads to unneeded complexity. During downturns, EDD’s policies and practices cause long delays and frustration for unemployed workers.

Program’s Basic Design Encourages EDD to Focus on Fraud and Containing Costs. Three key features of the program’s basic design have encouraged the state to adopt policies that make getting benefits difficult. First, the state operates the UI program with an orientation toward businesses (as the entities financing the program), which have a clear incentive to contain costs. Policies formed under this orientation tend to emphasize holding down business costs. Second, pressure from the federal oversight agency to avoid errors encourages the state to conduct lengthy reviews. These steps probably catch some mistakes, but make getting benefits challenging and time‑consuming for everyone else. Finally, to keep the program solvent, the state may look for ways to contain UI costs. The state UI trust fund does not build large enough reserves during normal times to weather downturns. Without legislative action to address this imbalance, the department may feel pressure to prevent the fund from becoming insolvent.

Signs of Imbalance in the UI Program. In this report, we highlight five key signs of the state’s imbalanced UI program. First, the department improperly denies many UI applications. More than half of EDD denials are overturned on appeal, while less than one‑quarter are overturned in the rest of the country. Second, UI claims are regularly delayed by weeks and often months, especially during downturns. Third, the administration’s assessment—conducted during the height of the pandemic—laid out how difficult the UI program is for workers. Fourth, we catalog state rules and application steps that make it unreasonably difficult for workers to prove eligibility and time‑consuming to apply for benefits. Finally, we highlight several concerning steps taken by EDD in recent years that suggest that ensuring eligible workers get benefits is not among its top priorities.

Improving the UI Program. Although these problems are not new, the pandemic has highlighted the need for the state to rebalance the UI program to make getting benefits to eligible workers a top priority. In our assessment, today’s problems do not call for fundamental reforms that could upend longstanding tenants of the state’s labor market. Instead, targeted changes to state practices could improve the experience unemployed workers have when they need UI. In this report, we suggest more than a dozen targeted changes to the state’s UI program to place greater priority on getting payments to eligible workers.

LAO Recommendations to Improve Unemployment Insurance (UI)

|

|

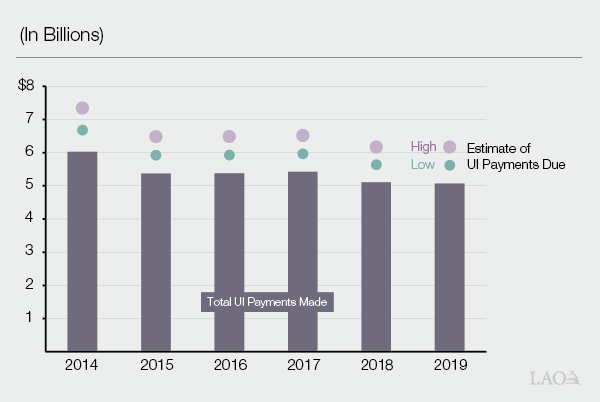

More than half of the UI claims the Employment Development Department (EDD) denies are overturned on appeal. Overturned denials cause lengthy delays for workers who appeal and raise concern that the state denies many eligible workers. Likely between $500 million and $1 billion annually in UI payments go unpaid each year due to improper denials. |

|

|

|

|

|

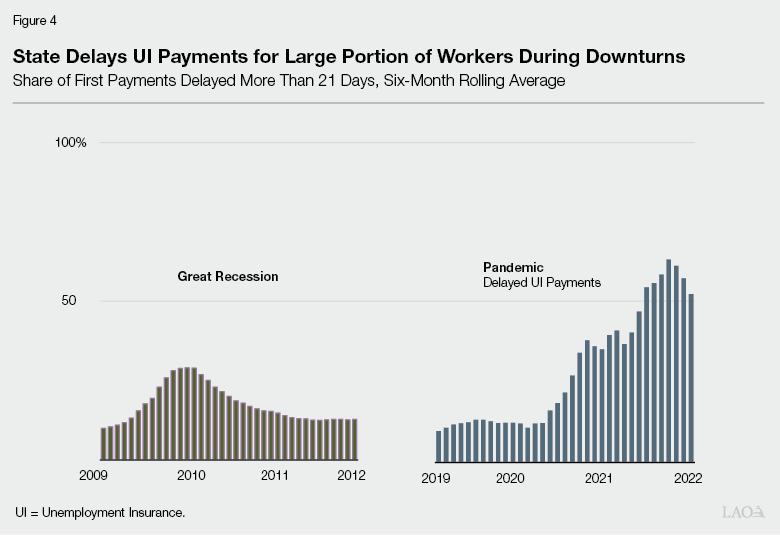

More than half of UI claims were delayed during the peak of the pandemic, for many workers by several months. Between 15 percent and 20 percent of workers who apply for UI during normal economic times experience delays. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

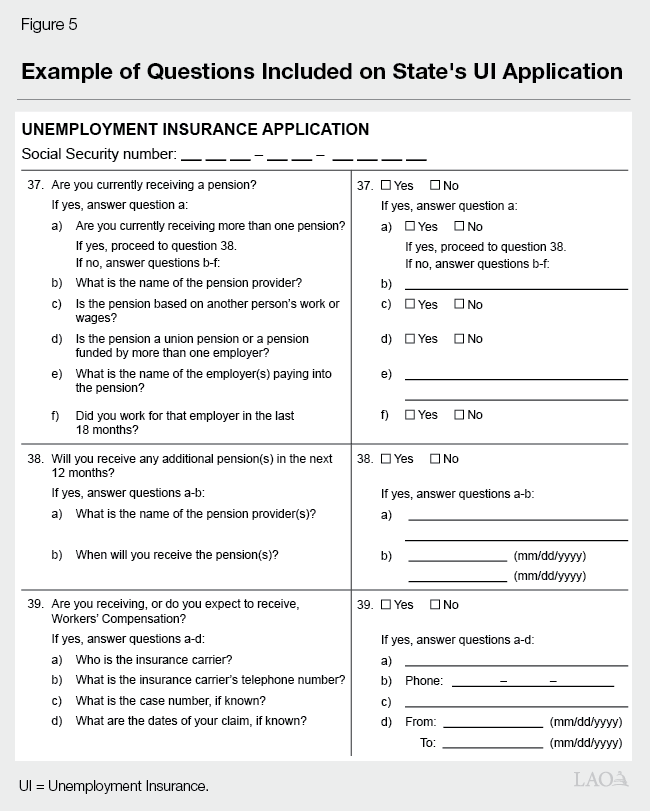

The state’s UI application and ongoing requirements are difficult to understand and unnecessarily lengthy. |

|

|

|

|

|

Introduction

California’s Unemployment Insurance (UI) program provides temporary wage replacement to unemployed workers. First enacted in response to the Great Depression, UI helps alleviate temporary economic challenges for workers and their families. By backfilling lost wages, the program also bolsters the state economy during economic downturns. Despite its importance to workers and the economy, the wage replacement program faltered during the two most recent downturns—the Great Recession and the pandemic. At the Employment Development Department (EDD)—which oversees UI—payments were delayed for roughly 5 million workers and improperly denied for likely 1 million more. The department’s phone lines were routinely overwhelmed by the number of frustrated callers. These failures caused hardship for unemployed workers and their families, held back the economic recovery during both periods, and spurred frustration among Californians with their state government. Recent failures can be traced back to the UI program’s basic design, which encourages EDD to adopt policies and practices that place more emphasis on eliminating fraud and minimizing business costs than making sure eligible workers can easily get benefits.

Our Approach to Improving the State’s UI Program. Although these problems are not new, the pandemic has highlighted the need for the state to rebalance the UI program to make getting benefits to eligible workers a top priority. In our assessment, today’s problems do not call for fundamental reforms that could upend longstanding tenants of the state’s labor market. Instead, targeted changes to state practices could improve the experience unemployed workers have when they need UI. In prioritizing getting payments to eligible workers, these changes also would help bolster the state economy during downturns, by distributing economic support broadly and quickly to lessen the economic impact of job losses. In this report, we outline how incentives to contain UI costs make it difficult to get benefits, trace these consequences back to the UI program’s basic design, and lay out changes to place greater priority on getting payments to eligible workers.

California’s UI Program

What Is Unemployment Insurance?

The state’s UI program provides weekly wage replacement to workers who have lost their jobs through no fault of their own. The state’s EDD oversees and operates UI. The program is intended to replace half of workers’ wages for up to 26 weeks. State law sets the maximum benefit at $450 per week. The average benefit is about $330 per week. Unemployment insurance covers traditional employees. Independent contractors, self‑employed individuals, informal workers, and undocumented workers are not covered.

Who Is Eligible to Receive Benefits, and How Much?

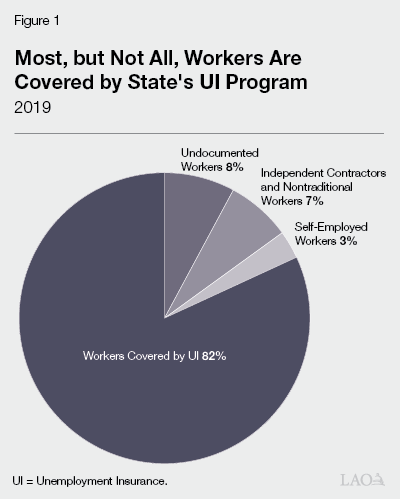

Most Workers Are Eligible to Receive UI Benefits… Most California workers are covered by UI and therefore eligible for benefits when they become unemployed. Under state law, all traditional employees are covered by UI. Traditional employees are workers who work for the same business day to day. Most workers in California fall under this category. As shown in On Figure 1 , the state’s UI program covered more than 80 percent (or 17.4 million) of California workers in 2019.

…But Some Workers Are Not Covered by State’s UI Program. Nontraditional workers are not eligible for UI. As shown in Figure 1, between 3 million and 4 million workers are not covered. Ineligible workers include: undocumented workers (about 8 percent of all workers), independent contractors and other nontraditional workers (about 7 percent), and self‑employed workers (about 3 percent).

Despite Broad Coverage, Workers Must Meet Certain Requirements. Despite broad coverage, workers covered by UI must meet certain requirements to get payments. Workers must meet three requirements to get payments:

- Recent Work History. Workers must have made at least $1,300 in one quarter during the worker’s “base period.” Set by state law, the base period is the first four of the last five completed calendar quarters prior to the job loss. Some workers also may be eligible under the state’s alternative base period, which is the last four completed calendar quarters prior to the job loss. Workers who started working recently—for example, recent school graduates or workers returning to work after looking after children—often do not meet this requirement.

- Stopped Working Through No Fault of Their Own. Workers must have been laid off (including for poor performance), had their hours reduced, or quit with good cause. Good cause covers quitting to (1) care for a family member, (2) relocate for a spouse’s work, (3) avoid unsafe working conditions, (4) flee domestic violence, or (5) respond to a large pay cut. Businesses may dispute a worker’s UI claim if they believe their former worker does not meet these requirements.

- Able and Available to Work if Another Opportunity Comes Up. To get benefits initially, and to continue getting benefits each week, unemployed workers must be “able and available” to work. Workers are able to work if they are capable of performing work in their usual job field. Illnesses and injuries are common reasons a worker would not meet this requirement. Workers are available to work if they are willing to accept reasonable work. Common reasons a worker would not meet the available requirement include (1) caring for a child at home, (2) not having legal work status, (3) seeking part‑time work when the prior job was full time, (4) not commuting longer distances for a new job, and (5) using the period of unemployment to change careers. Once UI payments begin, unemployed workers must “certify” with EDD every two weeks that they are still able and available to work.

UI Payments Intended to Replace Half of Prior Wages. The state sets weekly UI payments based on prior earnings. Workers receive half of their average weekly earnings, based on their highest earning quarter of their base year. State law set in 2005 also caps the maximum payment at $450 per week. Due to the cap, many workers—those who make more than $46,000 per year—get payments that are less than half their usual earnings. In 2019, about 40 percent of UI recipients earned enough to get the maximum state UI payment.

Who Pays UI Taxes, and How Much?

Businesses Pay Payroll Taxes to Cover UI Payments and Overhead Costs. Businesses pay state and federal UI payroll taxes. Revenue from the state tax, which averages 3.6 percent on the first $7,000 in wages (equal to $252 per worker each year), goes into the UI trust fund to pay out future benefits. Federal law requires states to tax the first $7,000 in wages at a minimum. Most states tax a higher amount—only California, Tennessee, Florida, and Arizona tax the minimum. Revenue from the federal tax is collected by the federal government and redistributed to states to cover UI overhead costs.

Federal UI Tax Is Applied Uniformly to All Businesses. The federal UI tax applies uniformly to all businesses, regardless of the amount of UI payments made to their former workers. The federal tax rate is 0.6 percent on the first $7,000 in wages. This equals $42 per worker each year. Federal law allows states to take on federal loans to keep making UI payments if their state trust fund runs out of reserves. To repay state loans, the federal tax rate paid by businesses in the state goes up incrementally. During the pandemic, many states, including California, used federal loans to keep making UI payments.

State Tax Rates Depend on Trust Fund Condition… State UI tax rates also apply to the first $7,000 in wages but vary based on two factors. The first factor is the condition of the state’s UI trust fund. Higher tax rates apply when the condition of the UI trust fund is poor, theoretically so that the fund’s reserve can be replenished. However, due to the trust fund’s longstanding poor condition, the highest tax rate schedule—known as the F+ schedule, which carries a 6.2 percent maximum rate—has been in effect every year since 2004.

…And How Often Their Workers Become Unemployed and Get UI Payments. The second factor that affects businesses’ state UI tax rate is the businesses’ “experience.” To allocate the program costs to businesses that use the program most, each employer’s tax rate goes up when their former workers get UI. Tax rates also go down if few workers become unemployed and get UI payments. (Under this practice, known as “experience rating,” a business’ annual tax rate can range from 1.5 percent to 6.2 percent depending on how many prior workers get UI benefits.) Businesses have a clear incentive under this design to minimize UI payments that to go their former employees.

What Is the Role of the Federal Government?

Federal Government Oversees Program, but Policies and Rules Set by the State. The federal government created the unemployment insurance system in 1935 as part of the same law that created the Social Security retirement system. The federal government provides funds to states to run their UI program. In exchange, states must operate their UI programs within broad federal guidelines. Within the broad guidelines, however, states have ample room to set the important policy and program rules that affect unemployed workers and their former employers.

Federal Government Suggests State Performance Targets. State programs must be certified to receive federal administrative funding. As part of its certification process, the federal government tracks state UI program performance and suggests targets to monitor how well states operate their UI programs. Although the federal government tracks key metrics and suggests performance targets, there are no penalties for states that do not meet the standards.

Why Is Getting UI Benefits Difficult?

For recently unemployed workers, applying for and getting UI payments can be a difficult process for various reasons. First, the application itself is lengthy and requires workers to report detailed, unnecessary information. Second, as a follow up to the application, workers often must submit back‑up documents to prove their eligibility or that they are who they say they are. Waiting for the state to request and review these documents can take weeks or months. Third, businesses frequently contest their former workers’ claims, triggering eligibility interviews with the department that can lead to long wait times. Fourth, workers who appeal the department’s decision to deny their claim must attend a hearing and, if successful, wait for the department to eventually restore their payments. Finally, unemployed workers must regularly certify with the department to keep getting benefits.

In this section, we explore potential explanations for why the process of getting UI payments has become so difficult.

EDD Faces Competing Objectives

Striking a Balance Between Fraud Prevention and Paying Eligible Claims. In administration of the state’s UI program, EDD must balance the need to prevent fraud and limit business costs with the priority to deliver payments in a timely and easy manner. Eliminating all fraud and overpayments would require onerous eligibility standards and a frustrating application process. On the other hand, a program without fraud controls would expose the state and businesses to financial risk.

Fraud in State UI Program Historically Uncommon. The most common type of overpayment is when a worker does not end their UI payments when they take a new job. These overpayments are relatively easy to detect because employers must report new hires to the state. On the other hand, relatively few overpayments occur because workers lied about being unemployed—for instance, if a worker quits their job but tells the department they were laid off. Until recently, fraudulent payments received using a stolen identity were rare. While stolen identity UI fraud increased during the pandemic, this was tied to a now expired federal program. In general, fraudulent claims in the state UI program are relatively uncommon—probably representing less than 1 percent of claims. The box nearby includes more information about the recent spike in identity theft fraud cases related to a temporary federal UI benefit program.

A Closer Look at Recent Identity Theft Fraud

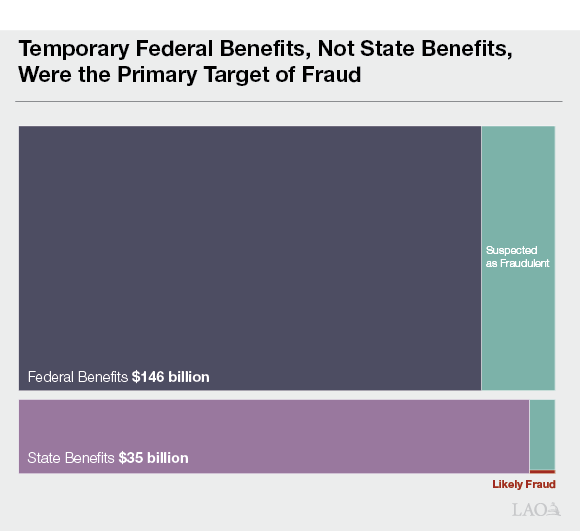

Recent Identity Fraud Concentrated in Temporary Federal Benefits That Have Ended. In California and across the country, an unprecedented level of identity fraud targeted Unemployment Insurance (UI) payments during the pandemic. The figure below shows the administration’s estimate of suspicious or confirmed UI benefit fraud that occurred during the pandemic. However, the vast majority of fraud occurred in the temporary, 100 percent federally funded programs that now have ended. The federal program did not require the basic fraud safeguards found in the state’s regular UI program. According to the administration, $18.7 billion (94 percent) of UI benefit fraud during the pandemic may have occurred in the federally funded programs, while the Employment Development Department (EDD) suspects $1.3 billion (6 percent) in state UI benefits fraud. Furthermore, the department’s estimate of state UI fraud ($1.3 billion) is likely overstated. EDD counted state UI claims as fraud if the worker did not confirm their identity when EDD asked. Yet there are several reasons why workers with legitimate claims may not have followed up with EDD. Many workers had already run out of benefits, giving them little reason to respond to EDD’s requests. Other workers may have given up in frustration after trying unsuccessfully to send in documents. An alternative estimate of state UI fraud, based on the administration’s strike team report, suggests that state UI fraud may have been much smaller, perhaps as little as $100 million. (The small red area of the figure represents this smaller fraud estimate.)

EDD Puts Significant Focus on Fraud Prevention. Due to a concern that workers may lie to get UI payments, EDD’s practices have evolved over time to meticulously scrutinize worker eligibility. This emphasis is often at odds with making sure eligible workers get benefits quickly and easily. Indeed, this emphasis hindered the state’s response to the pandemic. According to the administration’s own review of EDD practices, “In interviews and observations, stories and anecdotes about fraud and/or suspected fraud were often used to explain why EDD could not act quickly to avoid the growth of the [claims] backlog.” The added benefit of these lengthy reviews—that is, how much additional fraud they prevent—may be very small. Viewed alongside the state’s competing priority to deliver payments quickly and easily, the benefits of this level of emphasis may not justify the costs these practices carry for other eligible workers.

Program Design Encourages Disproportionate Focus on Fraud Prevention

State Policies and Practices Have Evolved to Make Getting Benefits Difficult. The key factor behind why getting benefits has become difficult is the UI program’s basic structure, which encourages EDD to disproportionately focus on stopping fraud and minimizing business costs. Without safeguards to make sure eligible workers can get benefits easily, the state’s policies and actions have tilted the UI program out of balance. Individually, policies and actions aimed at preventing fraud may appear justified and reasonable. Viewed as a whole, however, the collection makes getting benefits unreasonably difficult for eligible workers. Below, we outline how the UI program’s basic design has led to state policies and actions that make getting benefits difficult.

- EDD Operates UI Program With Orientation Toward Businesses, Which Have Incentive to Contain Their Costs. Under the UI program’s basic design, businesses fund the program, meaning their payroll taxes increase when former employees get UI. Businesses therefore have an understandable incentive to limit UI claims to help contain their operating costs. Due to their role as program funder, businesses also are EDD’s main customer. As such, the state has formed an explicit partnership with employers to run the UI program. The department’s 100‑page guidebook for employers, titled Managing Unemployment Insurance Costs, clarifies that businesses are an “important branch of the UI program partnership.” (This partnership does not include workers. Instead, workers “must also assume responsibility for their role in the UI program by meeting all UI requirements.”) The department also provides a training video for business titled “How to Protect Your Business from Higher UI Taxes” that provides tips on how to minimize their UI costs. The department also maintains an “Employer Bill of Rights” that sets out steps employers can take to dispute worker claims or EDD decisions to issue UI benefits. (Workers do not have a corresponding document.) State policies and practices formed under this orientation would tend to emphasize holding down business costs potentially at the expense of making sure eligible workers can get benefits easily.

- Federal Pressure to Avoid Errors Creates Incentive to Conduct Lengthy Reviews. The federal government is the primary funder of EDD’s costs to administer the UI program. As such, EDD faces pressure to meet the federal government’s goal of upholding “program integrity” by eliminating errors, overpayments, and fraud. This pressure creates an incentive for the state to conduct exhaustive reviews. For example, the state often requests follow‑up information to document worker identities or work history. The state also applies intricate rules to determine whether workers are eligible for UI. These steps probably minimize errors and improper payments in a small number of cases. For the vast majority of unemployed workers, though, these steps make getting UI payments challenging and time‑consuming. As discussed later, these steps also may result in the department improperly denying some eligible workers. In so doing, federal pressures on the department to eliminate errors and fraud may interfere with the goal of getting payments to eligible workers.

- To Keep the UI Trust Fund Solvent, State May Look for Ways to Contain Costs. Under longstanding state tax and benefit rules, the UI trust fund does not build large enough reserves in normal times to cover the increase in claims during a recession. This imbalance has become more severe in recent years. During the strong economic years leading up to the pandemic, the state trust fund accumulated only minimal reserves each year. With an absence of legislative action to address this imbalance, the department may feel pressure to use tools within its control to prevent the fund from becoming insolvent during normal economic times. Policies and practices that tend to contain state UI costs also would have the effect of helping to keep the UI trust fund solvent.

Antiquated Computer Systems Also Contribute to Difficulties. Like many state departments, EDD’s reliance on outdated technology limits its ability to respond swiftly to changing circumstances or even manage routine tasks quickly and automatically. Although the key factors that make getting benefits difficult are operational—that is, departmental policies, practices, and actions—the use of outdated and inefficient technology adds further complication, delay, and frustration for eligible workers trying to get benefits.

Signs of Imbalance in the UI Program

In this section, we discuss several clear indications—that is, practical effects of the incentives laid out above—that state policies and actions make it difficult for eligible workers to get benefits. These include: (1) the department’s tendency to improperly deny claims, (2) widespread payment delays, (3) the administration’s own assessment that the UI program is difficult for workers to navigate, (4) state rules that make it unreasonably difficult for workers to prove eligibility, and (5) recent actions that suggest that ensuring eligible workers get benefits is not a top priority.

Improper Claim Denials

Workers and Employers Can Appeal EDD’s Eligibility and Process Determinations. State staff decide whether workers are eligible for UI based on the worker’s application and EDD’s internal records. If a worker or employer disagrees with EDD’s eligibility decision, they may appeal to an administrative law judge (ALJ) at the California Unemployment Insurance Appeals Board (CUIAB). The appeals board interprets and applies state and federal UI law. At the hearing, the ALJ reviews the original application, interviews both parties, and issues a ruling. The ruling either upholds or overturns EDD’s decision. Each year, roughly 200,000 workers and businesses file UI appeals.

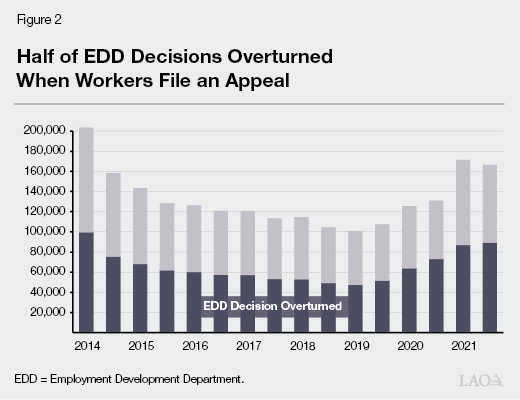

Half of EDD Decisions Overturned on Appeal. As shown in Figure 2, ALJs at the appeals board overturn EDD’s decision about 50 percent of the time. This means that, in most years, between 5 percent and 10 percent of all workers who apply for UI benefits are denied by EDD before being approved by an ALJ at the appeals board.

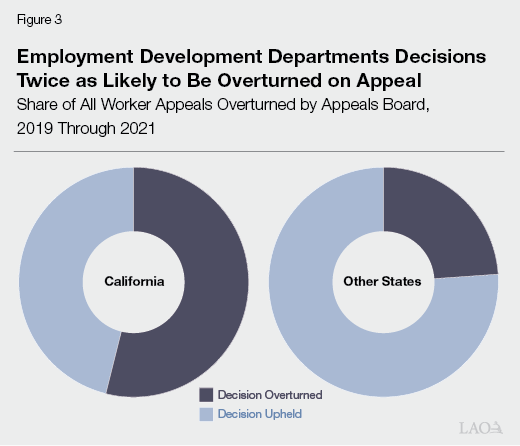

Relative to Other States, EDD’s Denials Decisions Twice as Likely to Be Overturned. Figure 3 shows the outcome of all worker appeals of UI benefit or eligibility decisions since 2019 in California and the rest of the country. More than half of EDD’s decisions to deny eligibility or limit benefits were overturned. In contrast, less than one‑quarter of other states’ decisions to deny eligibility or limit benefits were overturned. Over this same period, employer appeals resulted in overturned decisions less often (32 percent of the time) than worker appeals. California’s employer appeals result in overturned decisions about as often as other states (35 percent). We illustrate the potential magnitude of overturned denials in the box below.

What Amount of UI Payments Went Unpaid Due to Improper Denials?

The total amount of payments eligible workers do not receive because of improper denials is unknown. However, the financial cost of improper denials on eligible unemployed workers and the state likely is large. The figure below shows our best guess of the range of unpaid Unemployment Insurance (UI) benefits each year. These are payments that eligible unemployed workers would have received had the state not denied their application. As shown in the figure, likely between $500 million and $1 billion annually in UI payments went unpaid in recent years. (This figure does not account for workers who were eligible for UI but did not apply.)

Some Denials Appear Inconsistent With State Law. Our office has reviewed several EDD claim denials in cases where the worker was clearly eligible for UI. In one case, EDD denied a claim based on the rationale that statewide employment in the unemployed worker’s occupation was forecast to decline by 0.9 percent. (State eligibility rules require that a job market is available, not that an opening is available.) In another case, EDD denied the claim because the worker was caring for her children while unemployed. Thus, according to the decision, the worker was unavailable for work. (State eligibility rules allow parents to look after their children while unemployed, so long as they arrange child care when they get hired.)

While our review does not allow us to know how extensive these types of cases are, these examples raise questions about (1) the quality of staff training; (2) the complexity of current eligibility rules; (3) the extent to which EDD managers review staff eligibility decisions; and (4) whether the department’s concern about fraud leads eligibility staff to err on the side of denying claims, even claims that have very limited fraud risk.

Delayed Payments

During normal economic times, state practices lead to payment delays for 15 percent to 20 percent of workers who apply for UI. However, during the economic downturns of the Great Recession and the pandemic, state policies caused much worse payment delays. Figure 4 shows the percentage of payments delayed by more than 21 days during the last two downturns. During the Great Recession, about 25 percent of workers seeking UI received delayed payments. During the pandemic, delays were more common—affecting between 30 percent and 50 percent of workers applying for UI. (These figures do not account for delays that occur when a claim is denied and later overturned. Including improperly denied claims would increase the share of workers whose payments the state delayed.) Routine payment delays indicate that state practices, as shaped by the program’s basic design, do not prioritize getting benefits to workers quickly.

Steps That Make Proving Eligibility Difficult

At several steps in the application process, the burden of proof is placed on workers to show that they are eligible for UI. Some of these steps require workers to submit extensive and potentially unnecessary information, while other steps seem to encourage businesses to dispute UI claims made by their former employees. While each of these elements may appear reasonable individually, when taken together they make it unduly difficult for eligible workers to get benefits.

Matching Identity Information. When an unemployed worker submits a claim for UI payments, EDD confirms the worker’s identifying information with the federal Social Security Administration and the state Department of Motor Vehicles. EDD is able to quickly process many claims using these automated steps. In many cases, however, a worker’s identity cannot be confirmed to EDD’s standards, often due to incomplete information or minor discrepancies. One example of a minor discrepancy is if a worker applies using their middle initial instead of their full middle name as found on their driver’s license. When worker documents do not match, EDD mails a notice to the worker requesting more documents. The worker then must submit the documents. Due in part to this high standard for identity documentation, EDD redirects about 40 percent of all UI applications to manual staff processing. In many cases, the worker returns the requested information and gets their UI payment, albeit after a delay. However, if the worker is unable to return the documents promptly (or if EDD cannot locate or process their documents), state staff disqualify the worker’s claim.

Duplicative Requests for Work History. Even though employers are required to report employees’ wage and work history to EDD, unemployed workers also must independently provide this information to EDD. This information includes addresses, total pay, hours worked, and hourly wage for each job in the past 18 months. EDD uses this information to decide if the worker is eligible for UI payments and, if so, for what amount. When information provided by the worker does not match EDD’s records, EDD may divert the claim to manual review. Like identity reviews above, claims that need work history review are almost always delayed by 21 days, and often longer.

Disputes of Worker’s Claim. When a worker applies for UI, EDD sends a notice to each business the claimant worked for in the past 18 months. Businesses can respond to the notice if they dispute the worker’s eligibility. The most common scenario is a dispute about whether the worker quit or was fired. If they do not dispute the claim, businesses do not need to respond. However, the notice wording may encourage businesses to respond. The notice states “ACTION REQUIRED” and “Failure to respond may result in an increased employment tax rate and employer penalties.” As a result, businesses may respond to the notices when they do not dispute the claim, causing unnecessary delays. When a business responds to the notice, the business and worker must respond to questions during interviews scheduled by EDD. These interviews often lead to payment delays, up to several months in some cases.

State Proactively Investigates Certain Claims. When applying for UI payments, unemployed workers must describe how they became unemployed. Often the work separation is due to a lay off. Sometimes, though, the worker quit for good cause or was terminated. When a worker applies after quitting or being terminated, it is our understanding that it is the department’s practice to investigate the claim. This occurs even if the business does not dispute the claim. This practice may be inconsistent with state law. State law says that workers who quit for good cause or were terminated are eligible unless the business disputes the claim in writing. The investigation includes phone interviews with the business and the worker (similar to the investigation described above). These interviews often lead to payment delays.

Unusual Application Questions Can Create Confusion. The UI application includes questions that affect eligibility for a very small number of applicants yet add complexity for all applicants. The unusual questions relate to obscure program rules. As an illustration, Figure 5 shows a few questions that rarely affect eligibility. Other unusual questions relate to: (1) disaster unemployment assistance, a special federal program for workers in disaster areas; (2) pension income; (3) workers’ compensation and disability benefits for injured workers; (4) the worker’s prospects of starting a self‑employment business; (5) whether the worker is the officer of a private corporation; (6) whether the worker is a substitute teacher for Los Angeles Unified School District; or (7) whether the worker is an exempt appointee of the Governor.

Administration’s Own Strike Team Identifies Imbalance at EDD

On July 29, 2020, the Governor announced the formation of a “strike team”—jointly chaired by Yolanda Richardson, Secretary of the California Government Operations Agency, and Jennifer Pahlka, founder of Code for America—to learn more about struggles at EDD and to make immediate improvements. In September 2020, the strike team published an exhaustive, critical assessment of struggles at EDD and issued key recommendations to improve the UI program.

Key Findings.

- EDD is routing more claims to manual processing than it has capacity to process.

- EDD’s anti‑fraud measures delay payments to all claimants and do not prevent fraud.

- EDD’s cultural focus on fighting fraud interferes with the delivery of benefits to legitimate claimants.

- EDD denied claims for not mailing in requested documents while an average of 450 pounds of unopened mail sat in each EDD field office.

- Little or no assistance available to people who do not speak English as a first language, and fluent English speakers struggle to understand EDD notices.

- Unclear questions on UI application and other notices cause workers “extreme confusion and stress” and drive avoidable workload at EDD.

Key Recommendations.

- Purchase identity verification software to reduce the need for manual processing.

- Pause all new claims for two weeks to allow staff to work existing claim backlog.

- Assess ways that current practices to minimize improper payments and fraud affect legitimate claimants.

- Develop an “ideal” UI claim application and recertification form to simplify process.

LAO Perspective. The strike team’s findings were generally consistent with our office’s understanding of the major causes of the processing delays and backlog at EDD. Similar to our analysis, the strike team report identifies longstanding practices and one‑time actions at EDD that are inconsistent with the priority of ensuring eligible workers get benefits.

Recent Actions Suggest Getting Payments to Workers Is Not a Top Priority

In addition to longstanding policies and procedures that make it difficult for eligible workers to get benefits, recent actions during the pandemic also suggest that getting payments to eligible workers is not a top priority for the state. Below, we describe these actions in more detail and present simple steps the state and the department could have taken instead had getting payments to eligible workers been a top priority.

EDD Denied 3.4 Million Workers for Not Sending Documents Via Mail at Time When Department Could Not Process Its Mail. During the pandemic, the department struggled to process incoming mail and phone calls from workers. According to the strike team report, each EDD field office had an estimated 450 pounds of unopened mail and had no system for processing unopened mail. Further, at the state’s call centers, less than 1 percent of callers reached an EDD staff member. Of those, few were able to resolve their issues. Despite its inability to process incoming mail or answer phone calls, EDD disqualified 3.4 million UI claims during this time for failing to respond to EDD requests for additional information. This amounts to about one in four UI claims during the pandemic. The department made these disqualifications under a broad state law, UI Code 1253(a), which states that a claim is not eligible unless submitted “in accordance with authorized regulations.” Almost all 1253(a) disqualifications were made because workers did not submit, or EDD was unable to process, additional identity documents within the allotted time frame. Many of these disqualified workers may have been eligible for UI: of workers who appealed (about 200,000), the appeals board overturned EDD’s action 78 percent of the time. Had getting payments to eligible workers been a top priority, the state could have taken a different approach. For instance, the department could have extended the deadline for sending in identity documents or issued provisional payments while documents awaited processing. Further, with lessons learned from the Great Recession in hand, the state could have upgraded document processing, mail sorting, and call center capabilities prior to the pandemic.

EDD Mischaracterized Figures in Legislative Reports, Showing Far Fewer Denials. In response to initial reports of claim delays, the Legislature passed Chapter 264 of 2020 (AB 107, Committee on Budget) to improve oversight of EDD. The law directed the department to issue weekly reports to the Legislature about the UI claim backlog and the number of workers found to be ineligible, including workers who were disqualified. From the start of the pandemic to June 30, 2021 (the final report date), the department reported it had disqualified or denied 705,000 UI claims. Yet during that same period, the department disqualified 3.4 million claims under Section 1253(a) alone. When asked about this discrepancy, the department told our office that it interpreted “found ineligible” to mean workers who were ineligible under state and federal eligibility rules but not under state procedural rules. As a result of this narrow interpretation, the Legislature was unaware of the widespread reliance on procedural denials at a time when the department could not process incoming mail and phone calls. Had getting payments to eligible workers been a top priority, the department could have reported the full scope of claims that were found ineligible—instead of the narrowest scope—to bring the issue to the Legislature’s attention and begin work toward a solution.

Based on a Third‑Party Assessment, Department Froze Benefits for Eligible Workers. In December 2020, EDD hired a fraud consultant to review nearly 10 million claims issued during the pandemic for potentially fraudulent characteristics. In its review, the consultant flagged 1.1 million claims as potentially fraudulent. Without notifying workers ahead of time, EDD stopped payments for these claims. To reopen their accounts, workers had to verify their identity using a new identity verification service or their accounts would be closed. Ultimately, more than half of the claims—600,000 of the 1.1 million—flagged as fraudulent were confirmed as legitimate. For these workers, the process to reestablish their UI payments took several weeks (during which they received no UI payments). Had getting payments to eligible workers been a top priority, the department could have notified these workers beforehand and provided a 30‑day period to prove their identity prior to turning off UI payments.

Addressing State Practices

That Make it Difficult to Get UI

With recent lessons in hand, the state now has the opportunity to rebalance California’s UI program so that getting UI payments to eligible workers is a top priority. In this section, we lay out targeted steps the state could take to reduce improper denials, minimize delays, and simplify the UI application.

Steps to Limit Improper Claim Denials

Improper denials are a direct consequence of state policies and practices that have evolved alongside business, state, and federal incentives to contain UI costs. Denials are twice as likely to be overturned in California than in other states. Below, we lay out several specific steps the Legislature could take to minimize improper denials.

First, Policymakers Should Learn Why Claims Are Denied. Little is known about claims that EDD denies. To learn more about what types of claims the state denies, policymakers should direct the State Auditor to independently assess UI applications that EDD denies. Claims are denied for two main reasons: the worker is ineligible or the worker did not follow EDD procedures. As discussed below, the eligibility review would assess whether EDD follows current laws when determining eligibility, while the procedural review would identify the most common procedural reasons claims are disqualified.

- State Auditor Reviews Sample of Eligibility Denials. To learn more about claims where the worker was found ineligible, the State Auditor could audit eligibility denials from recent years. To do so, ALJs at the independent CUIAB would work with the State Auditor to review a random sample of denied claims to assess whether EDD denied the claim properly—that is, consistent with state eligibility law and regulations. Based on this review, the state could learn more about how often, and under what circumstances, workers are found ineligible. Further, the assessment would uncover any potential patterns behind improper eligibility denials. These findings could guide changes that improve EDD policies and practices.

- State Auditor Reviews Procedural Rules That Lead to Denials. To learn more about procedural denials, the state will need to learn more about the circumstances that lead to procedural denials. If procedural rules lead frequently to denials but provide few other benefits, reassessing these procedural rules could make getting UI benefits faster and easier at little cost.

Then, With Oversight, Give Appeals Board Authority to Set Policy and Practices. State law requires EDD to apply UI policy in accordance with precedent decisions made by the full appeals board of the CUIAB. However, only a small fraction of appeals goes to the appeals board. Further, longstanding EDD practice is to not appeal ALJ rulings that overturn their determination, meaning these cases are never escalated to the full appeals board. As a result, the appeals board has limited practical authority to direct EDD policy to correct broader appeals trends. For example, although ALJs overturned EDD staff’s procedural denials roughly 80 percent of the time during the pandemic, state law does not require EDD to revisit the procedures that led to such a high overturn rate. To correct state practices that have the effect of limiting UI payments, the state should give the appeals board the authority and responsibility to set UI policy and practices. Such a step would represent an expansion of the appeals board’s duties relative to current law. As such, the Legislature may wish to consider providing the appeals board additional legal and policy staff and closely overseeing the appeals board’s transition to setting UI policy.

Steps to Minimize Delays

Unneeded delays between application and first payment are one consequence of state policies and practices that have evolved alongside incentives to contain UI costs. The section below lists steps the state could take to limit these delays.

Reassess Requirements for Initial Identity Matches. One step to reduce delays due to manual processing is to reevaluate the usefulness of current identity requirements. To do so, the department could catalog why claims go to manual processing and what occurred after. For issues that workers frequently resolved, the department could relax that requirement. This process would build on improvements the department accomplished during the pandemic. For example, EDD discovered that many workers were misreporting their birthdates. (Workers were listing date, month, year as is customary in many parts of the world.) EDD sent these applications to manual review. In response, the department improved its online application to reduce confusion. Birthdate misreporting and the corresponding delays dropped.

Reword Employer Notice to Clarify That No Action Is Required. One step to limit EDD investigations that cause delays is to clarify employer UI notices. As discussed earlier, the department’s employer notices strongly encourage businesses to dispute UI claims. Rewording these notices to be clearer could potentially limit the number of unneeded eligibility investigations.

Limit Practice of State‑Led Investigations. An additional step to address claim delays is to limit the practice of investigating all “quit” or “fired” UI claims. (The state often investigates these claims even when the business does not dispute the claim.) The departmental practice of investigating these applications may unduly delay claims.

Reassess Practice of Allowing All Prior Employers to Dispute UI Claims. In addition to notifying workers’ most recent employer, EDD also sends notices to any other employers the worker had in the past 18 months. These notices show former employers the amount EDD will charge their reserve account (based on wages earned by the worker when they worked for the employer). Prior employers may dispute these charges. As discussed in more detail later, state law requires businesses to report payroll information to the department. As such, the department maintains all prior employment records. Given that the state already maintains these records, it is unclear what past employers would dispute. One additional way to limit payment delays would be to review whether past employer disputes frequently delay claims and reassess this practice if it furthers no clear state interest.

Assess Surcharge to Discourage Unsubstantiated Disputes and Appeals. Unsubstantiated business disputes (that trigger an EDD eligibility interview) and appeals (that trigger an ALJ review) delay claims and cause extra workload for EDD staff. Current state law does not discourage these types of delays. In fact, by requiring businesses to submit a claim dispute in order to maintain their right to appeal, state law may actually encourage these actions. As such, some businesses may view disputes and appeals as a no‑cost step to limit their UI costs. To ensure that businesses reserve disputes and appeals for substantiated disagreements, the state could assess a surcharge on unsubstantiated disputes and appeals. A surcharge could be in the form of a fee or an increased charge to their UI reserve account, such as 125 percent of the claim cost instead of the standard 100 percent.

Steps to Simplify Application and Clarify EDD Decisions

One clear byproduct of a UI program that does not prioritize getting benefits to eligible workers is that the UI application and ongoing requirements are not user‑friendly. EDD notices, decisions, and case file materials (that it shares before appeals) are technical and unclear. Further, workers who do not understand the state’s complex eligibility rules may not grasp why the state asks seemingly unrelated questions. As a result, some workers may answer mistakenly, leading to unnecessary delays or denials. Below, we offer steps to simplify these materials to ensure that they are not a hurdle to receiving UI.

Drop Work History From Application… The state’s application for UI asks workers to list exhaustive information about prior employers. For each employer in the last 18 months, workers must report: employer name, address, and telephone number; start date and end date; whether paid weekly, bi‑weekly, or monthly; total wages paid; and hours worked per week. The department requires workers to fill out these questions despite having this same information in their own database.

…And Make First Payment Based on EDD Records Instead. Asking workers to list out prior wages that the state already maintains serves little purpose and has the effect of lengthening the UI application. Because the state already maintains employer‑provided wage and hour information for all workers, the department could instead make first payments based on EDD records. After the department has started paying benefits based on its records, it could give workers the option to update EDD if they earned wages that were not reported by their employer.

In Addition to Existing Hiring Report, Set Up Layoff Report to Speed‑Up UI Application. Under state law, businesses must report all new hires to EDD within ten days. The department uses this information to make sure formerly unemployed workers do not continue getting UI payments after they have been hired. To rebalance the UI program, the state could also require businesses to report layoffs with ten days. The department could use this information to automatically connect newly unemployed workers with the UI payments for which they are eligible. Layoff reporting could have the effect of speeding up applications and ensuring that all eligible workers get benefits.

Reevaluate the Need for Extra Questions on the UI Application. The state’s application for UI includes questions that rarely affect UI eligibility. In many cases, the state could forego these questions and instead cross‑match applications against related state databases. For instance, EDD oversees the state’s temporary disability insurance program. As such, as part of the UI application review, the department could check to ensure that UI applicants are not also receiving disability payments. Eliminating unusual or duplicative questions would shorten the application and limit misunderstandings that cause delays.

Build on Recent Work to Rebalance Notification Procedures. Chapter 516 of 2021 (AB 397, Mayes) requires EDD to tell unemployed workers how to correct errors before the state disqualifies their claim based on those errors. (Before the law, workers often mistakenly answered questions about their ongoing eligibility. Without prior notice, the state charged the worker for an “overpayment” and disqualified the worker from future benefits.) Building on this improvement, the state may want to set clear standards for all EDD notifications. Rebalanced standards might set: (1) minimum number of days to respond to notices; (2) minimum requirements for EDD attempts to call, text, or e‑mail workers before denying or reducing UI claims; (3) what information EDD must share about why it denied a claim; and (4) readability standards for “Record of Claim Status Interview” reports (EDD shares its internal case file report with parties before appeal, but the internal documentation is incomprehensible).

Conclusion

Despite its importance to workers and the economy, the UI program faltered during the Great Recession and the pandemic. This caused hardship for unemployed workers and their families, held back the economic recovery during both periods, and spurred frustration among Californians with their state government. These failures trace back to the UI program’s basic design, which has encouraged EDD to adopt policies and practices that make it unreasonably difficult for eligible workers to get benefits. Although these problems are not new, the pandemic has highlighted the need for the state to rebalance the UI program in ways that make getting benefits to eligible workers a top priority.

Some of the changes we suggest in this report could be made quickly to immediately improve the process of getting benefits. Narrowing the instances when former employers can contest a worker’s claim is one example. Other changes we put forth here will take time to develop and implement and require broad participation from businesses, workers, and the department. Simplifying the application for UI benefits is an example of a more involved, substantial change. Given these differences, improving the UI program will require the state to pursue several approaches at the same time and carefully assess progress. In the end, though, undertaking this work would put the UI program in a better position to support workers and the economy during the next economic downturn.