LAO Contact

September 22, 2022

Assessing the Provision of

Criminal Indigent Defense

- Introduction

- Indigent Defense in California

- Recent Developments Impacting Indigent Defense in California

- State Lacks Information to Assess Indigent Defense Service Levels

- Recommendations

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

Individuals charged with a crime have a right to effective assistance of legal counsel under the U.S. and California Constitutions. This is to ensure they receive equal protection and due process under the law. The government is required to provide and pay for attorneys for those individuals who are unable to afford private attorneys. This is known as “indigent defense.”

Importance of Effective Indigent Defense. In addition to being a constitutional right, effective indigent defense in criminal proceedings can help mitigate or eliminate major consequences that defendants face regardless of whether they are convicted, such as losing a job due to being held in jail until their case is resolved. Effective indigent defense can also help ensure that all individuals are treated equitably in criminal proceedings, particularly lower‑income individuals and certain racial groups who are at greater risk of experiencing serious consequences from being involved in the criminal justice system.

Counties Primarily Responsible for Indigent Defense. In California, counties are primarily responsible for providing and paying for indigent defense. However, recent litigation suggests that the state could be held responsible for ensuring that effective indigent defense is being provided. Indigent defense is generally provided in a combination of three ways: (1) public defender offices operated by the government, (2) private law firms or attorneys that contract with the government to provide representation in a certain number of cases and/or over a certain amount of time, or (3) individual private attorneys who are appointed by the court to specific cases. The actual provision of indigent defense services, however, varies by county.

State Lacks Information to Assess Indigent Defense Service Levels. The state currently lacks comprehensive and consistent data that directly measures the effectiveness or quality of indigent defense across the state. This makes it difficult for the Legislature to ensure effective indigent defense is being provided.

Analysis of Limited Data Raises Questions About Effective Provision of Indigent Defense. In the absence of consistent statewide data and metrics more directly measuring the effectiveness or quality of indigent defense, we analyzed limited available data comparing funding, caseloads, and staffing of indigent defense providers with district attorneys who prosecute cases, allowing for a rough, indirect assessment of existing indigent defense service. The identified differences are notable enough that they raise questions about the effective provision of indigent defense in California. For example, in 2018‑19, spending on district attorney offices was 82 percent higher than on indigent defense.

Recommend Three Key Steps for Legislative Action. We recommend three key steps that the Legislature could take to ensure it has the necessary information to determine whether a problem exists with indigent defense service levels, what type of problem exists, and how to effectively address such a problem. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature: (1) statutorily define appropriate metrics to more directly measure the quality of indigent defense; (2) require counties collect and report data to the state’s Office of the State Public Defender; and (3) use the data to determine future legislative action, such as identifying whether resources are needed to ensure effective indigent defense as well as how such resources could be targeted to maximize their impact.

Introduction

Individuals charged with a crime have the constitutional right to effective assistance of legal counsel to ensure that they receive equal protection and due process before being deprived of their liberty. The government is required to provide and pay for attorneys for those individuals who are unable to afford private attorney representation. This is known as “indigent defense.” In this report, we: (1) provide background information on the provision of indigent defense in California; (2) discuss existing indigent defense service levels and the lack of information to assess indigent defense levels; and (3) make recommendations to improve the state’s oversight of indigent defense by defining appropriate metrics to more directly measure the quality of indigent defense, requiring the collection and reporting of data, and using such data to inform future legislative actions. In preparing this report, we consulted with indigent defense providers, researchers, and other stakeholders. We also analyzed data reported by counties to the State Controller’s Office and the California Department of Justice. Finally, we reviewed various papers and studies examining indigent defense in California as well as other jurisdictions.

Indigent Defense in California

What Is Indigent Defense?

Government‑Funded Representation of Defendants Unable to Afford Private Attorneys. The U.S. Constitution prohibits individuals from being deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. It also prohibits individuals from being denied equal protection under law. The U.S. Constitution further guarantees specific rights to individuals in criminal cases, including the right to a speedy trial and the right to have the assistance of an attorney. In combination, these constitutional rights have been interpreted to mean that defendants in criminal cases are entitled to receive effective assistance from an attorney when their life or liberty is at stake, unless this right is knowingly and intelligently waived. (We note, however, that what specifically constitutes effective assistance is generally undefined. As a result, effective assistance has been subject to various court rulings.) If a defendant is unable to afford an attorney, the government is responsible for providing an attorney to ensure that the defendant has the opportunity for a fair trial.

The California Constitution contains nearly identical provisions. State statutes contain provisions to ensure that both federal and state constitutional standards are met. For example, if individuals appear without an attorney for their first court hearing (known as arraignment) which is generally 48 hours from arrest, California courts are required to (1) inform them of their right to have an attorney before being arraigned at the end of the first hearing, (2) ask if they would like to have an attorney appointed, and (3) appoint an attorney to represent them if they desire one and are unable to pay for their own attorney. Indigent defense, as used in this report, refers to government‑funded representation of defendants who are unable to hire private attorneys.

How Is Indigent Defense Provided?

Representation Provided in Three Major Ways. States have developed systems for providing attorneys to defendants who are unable to pay for representation in criminal cases. In California, indigent defense systems provide representation in one, or a combination, of three ways: (1) public defender offices operated by the government, (2) private law firms or attorneys that contract with the government to provide representation in a certain number of cases and/or over a certain amount of time, or (3) individual private attorneys who are willing to take on indigent criminal cases and are appointed by the court to specific cases with compensation ordered by the court. (As we discuss below, the state recently authorized the Office of the State Public Defender [OSPD] to assist trial court indigent defense providers.)

Counties Primarily Responsible for Indigent Defense. In California, counties are primarily responsible for providing and paying for indigent defense services. Most counties use at least two of the three ways described above to provide representation. California law authorizes counties to establish a public defender office to provide representation within the county. Currently, as shown in Figure 1, 34 of the 58 counties have chosen to establish public defender offices. The remaining counties do not have public defender offices. In counties with public defender offices, the Chief Public Defender is appointed by the county board of supervisors unless the board decided the position was to be elected at the time the office was created. Currently, only the Chief Public Defender of San Francisco County is elected. State law requires that public defenders defend individuals who are (1) charged with a criminal offense that can be tried in the trial courts and (2) financially unable to pay for attorney representation. Upon an individual’s request or a court order, counties must also provide representation in other specified cases where liberty may be at stake, such as mental health civil commitments. Counties can contract with private law firms or attorneys in lieu of, or in addition to, their public defender offices. Finally, state law authorizes the court to determine reasonable compensation for private attorneys providing indigent defense representation that must be paid by the county.

Figure 1

34 of 58 Counties Operate Public Defender Offices

|

Counties With a Public Defender Office (34 Counties) |

||

|

Alameda |

Monterey |

Santa Cruz |

|

Contra Costa |

Napa |

Shasta |

|

El Dorado |

Nevada |

Siskiyou |

|

Fresno |

Orange |

Solano |

|

Humboldt |

Riverside |

Sonoma |

|

Imperial |

Sacramento |

Stanislaus |

|

Kern |

San Bernardino |

Tulare |

|

Lassen |

San Diego |

Tuolumne |

|

Los Angeles |

San Francisco |

Ventura |

|

Marin |

San Joaquin |

Yolo |

|

Mendocino |

Santa Barbara |

|

|

Merced |

Santa Clara |

|

|

Counties Without a Public Defender Office (24 Counties) |

||

|

Alpine |

Lake |

San Mateo |

|

Amador |

Madera |

Sierra |

|

Butte |

Mariposa |

Sutter |

|

Calaveras |

Modoc |

Tehama |

|

Colusa |

Mono |

Trinity |

|

Del Norte |

Placer |

Yuba |

|

Glenn |

Plumas |

|

|

Inyo |

San Benito |

|

|

Kings |

San Luis Obispo |

|

In counties with populations of more than 1.3 million people, state law requires courts appoint attorneys to defendants in a particular priority order. Public defender offices, if established by the county, have first priority. (A public defender office can refuse cases in various circumstances. For example, a public defender office can only represent one defendant in a multi‑defendant case.) The second priority is to county‑contracted private law firms or attorneys. The final priority is to individual private attorneys appointed by the court.

Actual Provision of Indigent Defense Varies by County. The provision of indigent defense service varies by county. For example, some counties provide indigent defense representation through criminal defense attorneys primarily focusing on addressing the immediate legal charge(s) facing the defendant. Other counties provide indigent defense services in a holistic manner in which a defendant’s legal issues are addressed along with underlying social or other needs that could lead to future criminal activity (such as the loss of employment, housing needs, mental health assistance, or immigration consequences). In this holistic defense model, defense attorneys—as well as investigators, social workers, and other staff—work collectively on a defendant’s case. Additionally, the manner in which indigent defense staff are used can also vary. For example, some public defender offices that employ social workers use them to connect clients with services while others use them to identify mitigating factors to assist with clients’ legal defense (such as a defendant’s history of having been abused).

OSPD Recently Authorized to Assist Trial Court Indigent Defense Providers. OSPD is a state agency that historically represented defendants appealing their death penalty convictions. The mission of the agency was expanded in 2020 to include representation in trial court indigent defense cases—which is in addition to the representation provided by counties discussed previously. Additionally, the state also expanded OSPD’s mission to include providing assistance and training to indigent defense attorneys as well as other efforts to improve the quality of indigent defense representation. The extent to which OSPD intends to use this expanded authority is currently unclear.

Why Is Effective Indigent Defense Important?

Constitutionally Guaranteed Equal Protection and Due Process Right. As discussed above, the U.S. and California Constitutions guarantee the right to effective attorney assistance (unless knowingly and intelligently waived) to ensure that defendants in criminal proceedings receive equal protection under law and due process before being deprived of life or liberty. The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) found that the right to counsel is “fundamental and essential to fair trials” in the United States and that defendants who are too poor to hire attorneys cannot be assured of a fair trial unless attorneys are provided by the government. The U.S. Supreme Court further noted that even an intelligent and educated person would be in danger of conviction due to a lack of skill and knowledge for adequately preparing a defense to establish innocence. As such, effective defense counsel is necessary to ensure a defendant has a fair trial against government‑funded and trained prosecutors—irrespective of their income level.

Stakeholders argue that the right of due process is important in criminal proceedings because prosecutors have significant flexibility to determine whether and how to charge individuals (such as for a misdemeanor versus a felony), how a defendant’s case will proceed through the courts, and how cases will be resolved. Stakeholders further argue that effective assistance of counsel is even more important as the majority of criminal cases are resolved prior to trial—such as through plea bargains. This means these cases are typically decided through negotiations between prosecutors and defendants. Accordingly, without effective assistance of counsel, defendants would be at a significant disadvantage against legally trained prosecutors and would have difficulty obtaining a fair outcome. We note that, in 2019‑20, 97 percent of felony cases were resolved prior to trial. Of this amount, 80 percent were guilty pleas. Similarly, 99 percent of misdemeanors were resolved prior to trial over the same time period.

Helps Mitigate Potential Serious Consequences. Research demonstrates that involvement with the criminal justice system can have major consequences for defendants, regardless of whether they are ultimately convicted of a crime. For example, various interactions—such as being arrested, appearing in court routinely for proceedings, completing required community service, and being incarcerated both pre‑trial and post‑trial—can have consequences for defendants’ employment, child custody, housing, or immigration status (such as the loss of legal status and deportation). These consequences can have a disproportionate impact on lower‑income individuals. For example, such individuals may not have jobs willing to provide sufficient time off to come to court. As such, these defendants may choose to settle a case and avoid losing their jobs rather than contesting the case and going to trial. These consequences can also have a disproportionate impact on certain racial groups in California as well. This is because these groups are more likely to be (1) involved with California’s criminal justice system due to the racial disparities that currently exist in the system and (2) lower‑income due to economic disparities that have existed historically. (Please see the box below for additional information on racial disparities in the criminal justice system.) Collectively, this means that lower‑income individuals and certain racial groups are at greater risk of experiencing these serious consequences.

Racial Disparities in the Criminal Justice System

Research indicates that racial disparities exist at various points of California’s criminal justice system—including in law enforcement stops, arrests, and prosecutions. Such racial disparities are particularly notable for African Americans and Hispanics. Examples of such research are provided below.

- Stops. In its 2022 annual report, the state Racial Identity and Profiling Advisory Board evaluated data collected in 2020 from 18 law enforcement agencies, including the 15 largest agencies in California. The board found that a greater proportion of African Americans were stopped (17 percent of stops) relative to their proportion of the population (about 7 percent of the population).

- Arrests. In a September 2019 report, the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) found racial disparities in arrests statewide. For example, PPIC found that the African American arrest rate in 2016 was three times the white arrest rate. PPIC also found that African Americans have higher arrest rates than whites in nearly all California counties—with arrests rates that are on average about six times higher in counties with the largest disparities and nearly two times higher in counties with the lowest disparities.

- Felony Prosecutions. In a 2021 report, Judicial Council found that African American and Hispanic adults were disproportionately represented in felony defendants. Specifically, African Americans made up 19 percent of felony defendants and about 6 percent of the state’s adult population. Hispanics made up 45 percent of felony defendants and 36 percent of the state’s adult population.

Additionally, research suggests that African Americans and Latinos could also be less likely to afford a private defense attorney due to economic disparities. Specifically, in a 2016 report examining the Los Angeles area, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco—in partnership with several universities and research organizations—found that the median net worth of U.S. African American households ($4,000), Mexican households ($3,500), and other Latino households ($42,500) were substantially lower than white households ($355,000).

Effective assistance of counsel can help mitigate or eliminate such impacts, which is a factor that affects whether individuals actually receive equal protection and due process of law. For example, effective assistance can result in an individual being released from jail pending criminal proceedings that can take months or years to conclude. This allows the individual to avoid serious life impacts—such as losing a job or child custody—that otherwise may have resulted if the individual remained detained. It also reduces the pressure for individuals to settle cases to avoid such impacts and allows them the ability to determine whether and how to contest their cases, which could result in a not guilty verdict. Additionally, effective assistance can result in the identification of mitigating circumstances or relevant defenses that can lead to better plea deals, lesser charges, or dismissal of cases—all of which can help mitigate the major life consequences that could be experienced by individuals. As such, effective defense, including indigent defense, is a key tool to help ensure that all individuals are treated equitably in criminal proceedings.

Recent Developments Impacting Indigent Defense in California

Recent Legal Challenge

Concerns have been raised in various jurisdictions regarding whether effective indigent defense assistance is being provided. A recent challenge by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in California, in which Fresno County and the state were sued, suggests that the state could be held responsible for ensuring that effective indigent defense is being provided. Specifically, the state and Fresno County recently settled a case alleging a failure to provide constitutionally required indigent defense service levels. Notably, the court ruled that the state could not say it was not responsible for meeting its constitutional responsibilities just because the services are primarily provided by counties. It is unclear the extent to which other counties (and by extension the state) could face similar allegations in the future. Below, we discuss the recent legal challenge in more detail.

ACLU Filed Case Against Fresno County and the State. The ACLU filed a case against Fresno County and the State of California in 2015 alleging that Fresno County’s indigent defense system failed to comply with minimal constitutional and statutory requirements to provide effective assistance of counsel to indigent defendants. As shown in Figure 2, the lawsuit listed nine ways—such as excessive caseloads and a lack of support staff—in which these requirements were allegedly violated. It also asserted that the state abdicated its responsibility to ensure that effective assistance of counsel for indigent defendants was being provided by the county.

Figure 2

Alleged Ways Fresno County Failed to Provide Effective

Indigent Criminal Defense Service Levels

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

State and Fresno County Settled Case in January 2020. This case was not fully litigated and ultimately settled in January 2020. Prior to settlement, the state filed a petition asking the court to dismiss some of the allegations against it. The court refused to do so and specifically found that the state could not say it was not responsible for meeting its constitutional responsibilities just because the responsibilities had been delegated to the counties. The state settled by agreeing to expand the mission of OSPD so that it would be authorized to provide support for county indigent defense systems—including providing training and technical assistance, and identifying steps to improve the state’s provision of indigent criminal defense. The state also agreed to seek funding through the annual budget process for such purposes. A total of $4 million from the General Fund was provided in 2020‑21 ($3.5 million ongoing) for these purposes. As this case was settled, it is unclear whether other California counties are similarly situated—resulting in potential state liability in those cases as well.

We note that Fresno County also settled by agreeing to various requirements that it must comply with for four years. These requirements include: (1) providing a minimum amount of annual funding to the Fresno County Public Defender’s Office, (2) specifying goals for employing a certain number of supervisorial staff, (3) regularly reviewing and reporting case files, (4) adopting certain policies (such as related to the use of non‑attorney staff and to trial performance standards), and (5) the regular reporting of specified caseload and other data (such the number of cases opened and closed).

Increased State Involvement

Despite primarily being a county responsibility, the state has increased its involvement with the indigent defense system in recent years by providing funding and requiring certain assessments. As discussed previously, the state expanded OSPD’s mission to provide training and other assistance to trial court indigent defense counsel. Additionally, the 2020‑21 budget included $10 million one‑time General Fund for a pilot program to provide grants to eligible county public defender offices for indigent defense services. Additionally, the 2021‑22 budget included $50 million annually for three years for indigent defense providers to address certain post‑conviction proceedings. The budget also required counties to report on how the funding was used and that an independent evaluation be conducted to assess the impact of the provided funding by August 1, 2025. Finally, Chapter 583 of 2021 (AB 625, Arambula) directed OSPD—upon appropriation—to undertake a study to assess appropriate workloads for indigent defense attorneys and to submit a report with findings and recommendations to the Legislature by January 1, 2024. The 2022‑23 budget subsequently provided $1 million for this purpose.

State Lacks Information to Assess Indigent Defense Service Levels

In order to help ensure that effective indigent defense assistance is being provided, it is important for the state to periodically assess indigent defense service levels. However, as we discuss below, the lack of consistent data and metrics makes it difficult to fully evaluate existing service levels at this time. Although, some available data, which we present below, raise questions about the adequacy of current service levels and whether the state and counties are providing effective indigent defense assistance.

Lack of Consistent Data and Metrics to Fully Evaluate Indigent Defense Service Levels

The state lacks comprehensive and consistent data that directly measures the effectiveness or quality of indigent defense representation provided across the state. This makes it difficult for the Legislature to assess the specific levels and effectiveness of indigent defense being provided across counties.

County Choices Impact Data and Metrics Collected. Counties operate independently from one another and can make very different choices in the priorities and operations of various county programs—including their indigent defense systems. As a result, counties have taken different approaches to evaluating and monitoring the provision of indigent defense services. This means that the type of indigent defense data collected, how it is collected, and how it is used varies by county. The specific approach selected generally reflects how counties plan on using the information. For example, some counties collect data for budgeting purposes while others may collect data to monitor the quality of service provided (such as to ensure attorneys are not assigned to cases that exceed their experience levels).

Challenges Collecting Data. There are challenges in collecting data on the quality of indigent defense. In some cases, counties may not be collecting data in a robust and usable manner. For example, technology programs used by different actors (such as the public defender office, sheriff’s office, or court) may be not be programmed to capture certain data. There are also challenges coordinating data collection from private law firms or attorneys providing indigent defense. Finally, there are also challenges with collecting consistent data. For example, counties (and their departments) may not define a case or track cases in the same manner. The magnitude of such data collection challenges differs by county based on how each county administers and conducts oversight of indigent defense services. This makes it difficult to fully and fairly evaluate the effectiveness of indigent service levels currently being provided across the state.

Lack of Consensus on Appropriate Metrics. While there appears to be consensus on the overarching goals of providing effective defense representation, there seems to be a lack of consensus in California (and the nation generally) on what metrics should be used to directly measure the effectiveness of indigent defense representation—further contributing to the variation in data and metrics collected across counties. This is because there are different ways to measure whether effective assistance is being provided—such as whether it is legally effective (including whether a different outcome could have been obtained) or perceived to be effective (such as whether the defendant felt they received adequate representation). (In the box below, we discuss the various metrics and standards currently used across the nation to measure the effective provision of indigent defense representation.)

Wide Range of Metrics and Standards Used to Measure Effective Provision of Indigent Defense Services

Workload, Efficiency, and Quality Metrics

State and local jurisdictions across the country, including in California, use a wide range of metrics to evaluate the effective provision of indigent defense services. These metrics are not mutually exclusive and can be used concurrently with one another. For example, efficiency metrics should be used in combination with quality (or effectiveness) metrics. Below, we describe in more detail the categories of such metrics.

Workload Metrics. Workload metrics provide more objective and actionable ways of evaluating indigent defense performance as they generally help measure what activities an office and/or individual has worked on or completed. Workload metrics capture specific tasks (such as the number of active and closed cases), actions that indigent defense providers should engage in (such as the number of cases investigated), or a sense of the quality of representation provided (such as the number of motions filed to dismiss a case). Workload metrics are generally easy to collect as they frequently only involve tracking events. As such, these metrics are frequently used to manage an indigent defense office or to help justify budget requests. These metrics can also be used for comparisons within offices, across jurisdictions, or over time.

Efficiency Metrics. Efficiency metrics are intended to measure the extent to which resources are used in a manner that minimizes costs and maximizes benefit. Efficiency metrics can draw comparisons between various pieces of data (such as cost per case by case type) and reflect jurisdictional decisions for acceptable benchmarks for how workload is completed (such as the percent of cases resolved within a specific number of days from attorney appointment). Such metrics can also give a sense of how representation is provided to clients (such as the average time needed to completely resolve cases).

Measuring efficiency can be relatively difficult because it typically involves the comparison of data (such as data collected by various stakeholders who use different definitions) or requires the collection of more detailed data (such as when or how cases are resolved). Certain efficiency metrics (such as cost per case) also assume that service is being provided effectively. Additionally, certain efficiency metrics can be impacted by factors outside of the control of indigent defense providers. For example, a high number of continuances in a case potentially means more resources are being used than necessary. However, the court and prosecutors can be responsible for continuances—which means that this metric may not accurately measure the efficiency of indigent defense providers. Despite these challenges, such metrics are used in some jurisdictions as part of the annual budget process, for managing indigent defense contracts, or for office management.

Quality (or Effectiveness) Metrics. Quality (or effectiveness) metrics generally measure the value or impact of indigent defense services. Such metrics can be used to ensure that desired service levels are achieved by attempting to assess the effort of indigent defense attorneys (such as the number of days between arrest and first meaningful attorney and client interview), the benefit of outcomes achieved (such as the average percent of sentences avoided), or the avoidance of outcomes not directly related to sentencing (such as job loss or immigration consequences).

These metrics are frequently the most difficult to measure and collect data for, as well as to analyze and draw conclusions from, for various reasons. First, these metrics can be highly contextual as they can be impacted by prosecutors and other governmental parties involved in cases, as well as the priorities, decisions, and available resources within a given jurisdiction.

For example, the average percent of sentences avoided could be higher in jurisdictions where there is more aggressive prosecutorial charging. Second, these metrics can be impacted by choices made by defendants—such as some defendants accepting a plea offer in order to resolve a case as quickly as possible. Finally, such metrics can be highly subjective—such as whether a case was resolved prior to trial where the client benefits from not engaging in litigation and receives a less serious penalty.

In recognition of some of the challenges with these above metrics, other metrics focus on obtaining information directly from defendants through survey mechanisms (such as the percent reporting that they felt their attorney listened to their needs). In a slightly different approach, one California indigent defense provider has chosen to evaluate the quality of their services by surveying criminal justice stakeholders—such as judges and other criminal defense attorneys—to obtain their perspectives on how effectively their attorneys are representing their clients.

Given the challenges associated with this type of data, it appears that only a few jurisdictions actually collect and use such data on an ongoing basis. However, our understanding is that more jurisdictions and organizations are beginning to put greater focus on identifying appropriate effectiveness metrics and overcoming the challenges associated with them.

Guidelines and Standards

In addition to the metrics described above, various guidelines and standards are used by state and local jurisdictions across the country, including in California, to help ensure that minimum levels of effective indigent defense service are being provided. The metrics listed above can be used to ensure these guidelines or standards or met, or used to inform the setting of the standard. We describe a couple categories of such guidelines and standards below.

Minimum Quality Guidelines or Standards. Minimum quality guidelines or standards have been established by various international and national organizations (such as the American Bar Association and the National Legal Aid and Defender Association) as well as state and local entities (such as the California State Bar and the Michigan Indigent Defense Commission). The goal of such standards is to help ensure minimum quality service levels. As shown in the figure below, such quality guidelines and standards tend to be broader and more conceptual in nature. Jurisdictions may differ in how they interpret, implement, and determine whether the standards have been met. For example, one standard is to ensure competent representation. However, the specific metrics that should be used to determine whether competent representation is provided are undefined and left to interpretation. Enforcement of these guidelines and standards has been attempted through litigation in various states and jurisdiction or in cases brought by individual defendants.

Different jurisdictions ensure compliance with such guidelines and standards in various ways. One such method is through management or performance reviews of indigent defense providers. Another method used is screening attorneys for competency and monitoring billing. For example, the Alameda, Kern, and San Mateo County Bar Associations review applications of private attorneys, determine which cases match their experience and ability levels, and review compensation requests to ensure attorneys are engaging in activities that are considered to be essential in providing effective defense counsel.

Caseload Standards. Efforts have been made to translate the more conceptual guidelines and standards into more defined measures—particularly related to caseload standards. In 1976, the National Study Commission of Defense Services established maximum attorney standards—such as annual caseload not exceeding 150 felony cases or 400 misdemeanor cases (excluding traffic cases)—that have been used as a comparison for decades. In more recent years, various jurisdictions have used weighted

time‑study methodologies to establish maximum caseload standards tailored to the specific jurisdiction, their court processes, and specific case types. These studies are based on (1) the amount of time practitioners believe should be spent on specific tasks in cases, (2) the number of work hours available, and (3) assumptions about appropriate attorney‑to‑staff ratios. For example, a time‑study in Virginia recommended annual caseloads not exceed 45 non‑capital murder or homicide cases, 145 violent felony cases, 257 nonviolent felony cases, and 757 misdemeanor cases.

Jurisdictions have used such caseload standards in different ways to help ensure that minimum levels of effective indigent defense service are being provided. The most common way is to determine staffing levels (and how staff should be distributed) and to justify budget requests. There have also been efforts to more rigorously enforce such standards—such as indigent defense providers limiting their availability by not taking new cases when maximum caseload standards are exceeded regularly. In contrast to the quality metrics described above, these methodologies reflect assumptions about the time needed to provide effective and quality representation and do not actually evaluate the provision of indigent defense services.

Examples of Quality Guidelines and Standards

|

The International Legal Foundation |

|

|

|

|

|

American Bar Association (ABA) Ten Principles of a Public Defense Delivery System |

|

|

|

|

|

ABA Guidelines of Public Defense Related to Excessive Workloads |

|

|

|

State Bar of California Guidelines on Indigent Defense Services Delivery Systems |

|

|

|

Comparisons of Limited Data Raise Questions About Service Levels

As discussed in the prior section, there is a lack of consensus on what data and metrics should be used to directly measure the effectiveness of indigent defense representation—including whether legal effectiveness, the perception of effectiveness, and/or some other definition of effectiveness should be measured. However, effectiveness is likely correlated with the amount of time and resources available for indigent defense providers to spend on cases. For example, sufficient resources can enable indigent defense providers to spend the time necessary to develop a trusting relationship with their clients in order to obtain information that can be critical to a defense, to assess what outcomes are desired (such as to minimize time spent incarcerated or to avoid immigration consequences), and to assist clients to determine how they would like to proceed in their cases. In addition, the ability of indigent defense providers to effectively represent their clients can be undermined if they have significantly less resources than the prosecutors seeking to convict their clients. For example, if indigent defense providers have less resources than prosecutors to employ investigative services, it means they might not be able to fully explore mitigating circumstances that could impact a client’s defense regardless of whether it results in a different outcome. This is because a defendant might not feel their case was fairly and fully argued.

In the absence of consistent statewide data and metrics more directly measuring the effectiveness or quality of indigent defense, we compare limited available data related to the resources available to indigent defense providers as well as the district attorneys who prosecute cases. We also compare such data between counties. Examining differences in funding, caseloads, and staffing allows for a rough, indirect assessment of existing indigent defense service levels by considering the amount of time and resources available for each client. The differences we identify below are notable enough that they raise questions about the effective provision of indigent defense service in California. (Please see the box below for a discussion of limitations of the data used for this assessment.) In this section, we use the term indigent defense to refer collectively to (1) county‑funded public defender offices, (2) contracts with attorneys, and (3) court‑appointed private attorneys.

Limitations of Available Data

There are certain data limitations that offer important context for the comparisons provided in this report regarding indigent defense service levels. Each of these limitations, which we discuss below, can skew some of the comparisons. We note that the workload and staffing data is through 2018‑19 as this is the last full fiscal year before the COVID‑19 pandemic, which had significant—likely limited term—impacts on the processing of criminal cases, meaning that workload and staffing data from that time period may not accurately reflect ongoing trends in the provision of indigent defense.

Spending Data Limitations. First, the spending data for district attorney offices and indigent defense providers is generally pulled from data reported by counties to the state. Our understanding is that most of the reported spending is supported by county funds. However, the state and others (such as federal grants) provide some support—which can differ by county and between district attorney offices and indigent defense—creating differences that are not solely based on county choices. Second, spending on district attorney offices may not represent all prosecutorial resources. For example, certain city attorneys within Los Angeles County generally prosecute misdemeanors and funding for these offices are not captured in the data below. It is unclear how widespread this practice is. Additionally, we note that prosecutorial offices also have access to law enforcement resources as well—such as for the investigation of cases. It is unclear how much is spent on such prosecutorial purposes. Accordingly, the total resources available for prosecution are likely greater than reflected in the available data. Third, we note that some individuals may choose to pay directly for private attorneys for representation instead of making use of the indigent defense system. This means that the amount of funding spent per person or per arrest for indigent defense may be higher than reflected by the data. The extent to which they do likely varies by county. Additionally, some spending on indigent defense providers is used to support noncriminal and/or certain juvenile‑related workload (such as mental health civil commitments). This means that the amount of funding directly related to criminal proceedings is lower than reflected by the data. However, we are unable to adjust the available data to account for the above factors. As such, this data reflects a trend to inform the Legislature.

Staffing Data Limitations. First, the staffing data that counties provide to the California Department of Justice (DOJ) does not include individuals providing service through contracts or direct payments. Most, notably, it excludes indigent defense attorneys and staff not employed by a public defender office. This limits our staffing comparisons to the 32 out of the 33 counties that chose to operate public defender offices and reported data to DOJ between 2009‑10 and 2018‑19. (The data excludes Santa Cruz County as it began operating a public defender’s office in 2022. Additionally, we exclude Shasta County since it does not appear any data was reported during this time period.) Second, the staffing data is reported on June 30 of every year and may not fully reflect the number of positions each office is budgeted for. For example, it is unclear whether positions that are temporarily vacant—such as from a retirement—are counted in the data. Third, it appears that agencies may also differ in how they categorize and report their staffing levels—which can then impact the reported staffing ratios.

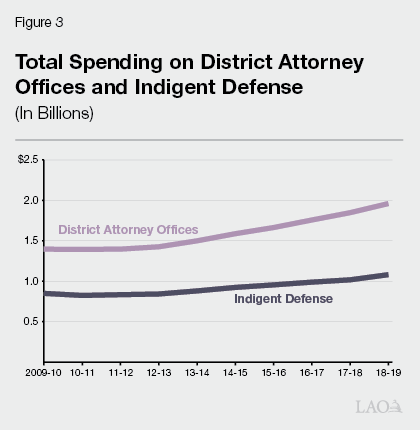

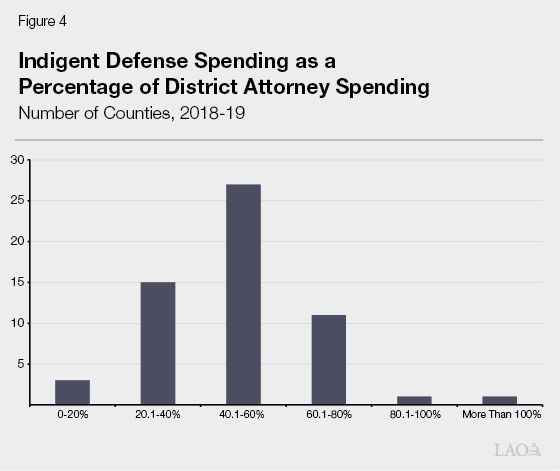

Differences in Spending Levels. Similar spending levels between prosecutors and indigent defense could indicate that there is a level playing field which ensures that both sides have the ability to explore all evidence as well as prosecution/defense arguments. In 2018‑19, nearly $3 billion was spent statewide to support district attorney offices ($2 billion) and indigent defense ($1.1 billion). (As we note later in this report, various potential justifications have been offered by stakeholders for differences in resource levels between district attorney offices and indigent defense.) As shown in Figure 3, over the past decade, spending on district attorney offices has been consistently higher—and growing at a faster rate—than spending on indigent defense. One common way used to compare differences in indigent defense and district attorney office spending is to calculate how much is spent on indigent defense as a percentage of how much is spent on district attorney offices. In 2018‑19, spending on indigent defense across the state was about 55 percent of the amount spent statewide on district attorney offices. In other words, spending on district attorney offices was 82 percent higher than on indigent defense. As shown in Figure 4, this percentage varies by county, with 27 counties (almost half) reporting that spending on indigent defense in 2018‑19 was between 40.1 percent to 60 percent of the amount spent on district attorney offices.

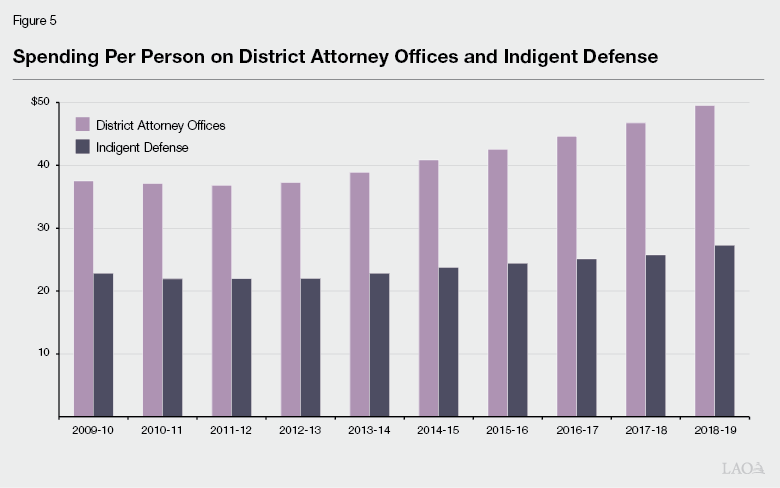

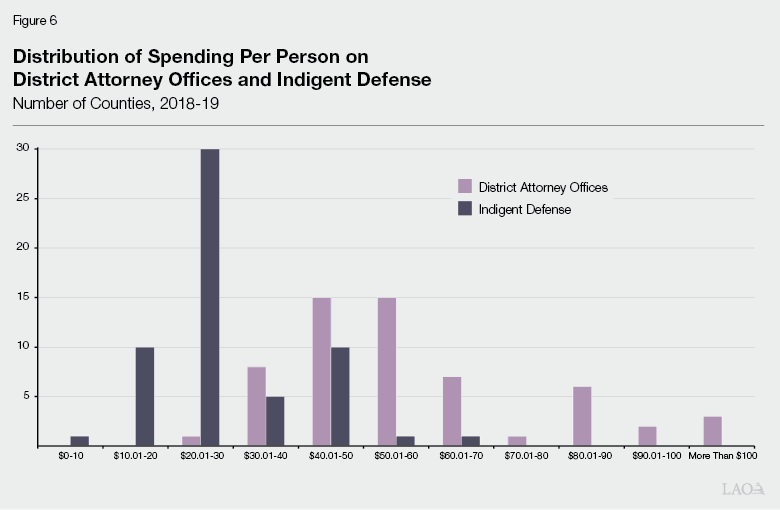

Another way to compare spending is on a per person basis (total county spending compared to total county population) to account for differences in population. As shown in Figure 5, between 2009‑10 and 2018‑19, the amount spent statewide on district attorney offices and indigent defense per person increased, with the amount spent on district attorneys being higher. Specifically, spending on district attorney offices was nearly $50 per person in 2018‑19—an increase of about $12 per person (or 32 percent) from 2009‑10. In contrast, spending on indigent defense was about $27 per person in 2018‑19—an increase of about $4 per person (or 20 percent) from 2009‑10. As shown in Figure 6, per person spending in 2018‑19 varies by county with greater variance in per person spending on district attorney offices as compared to indigent defense. This means that the magnitude of the difference in spending on the district attorney office and indigent defense can be much greater in certain counties. Most counties spent around $10 to $50 per person on indigent defense. In contrast, per person spending on district attorney offices for more than three‑fourths of counties was between $30 to $70.

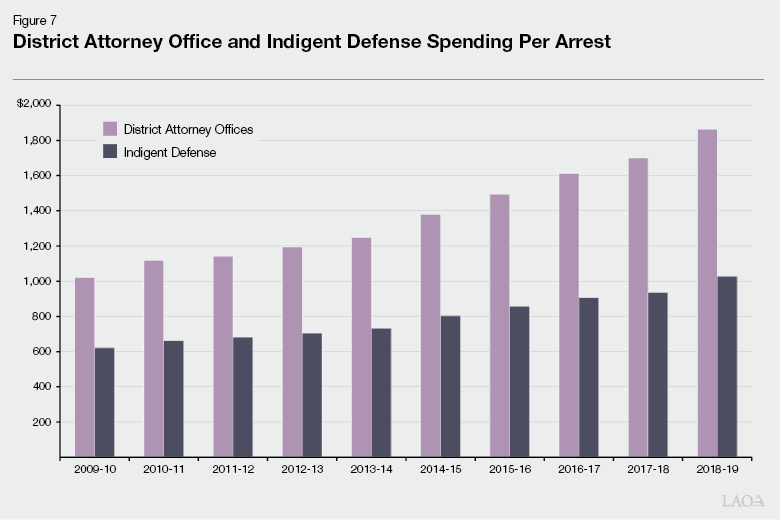

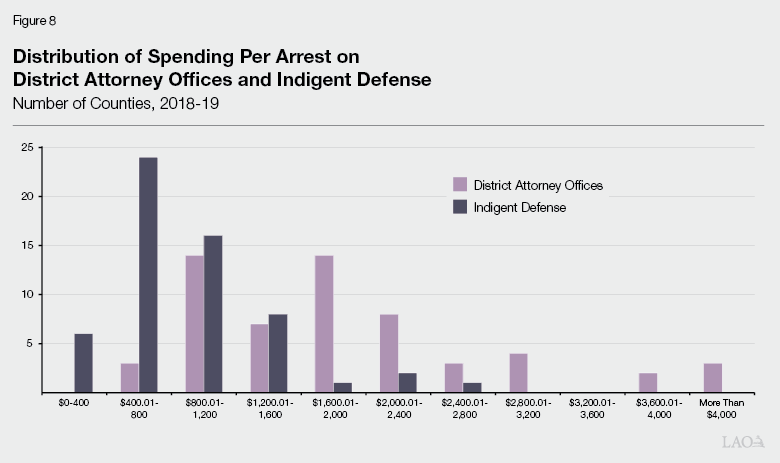

A third way to compare spending is on a per arrest basis, as arrests can be a strong indicator of potential workload. Despite a statewide decrease of approximately 315,000 arrests (or 23 percent) between 2009‑10 and 2018‑19, the amount spent statewide on district attorney offices and indigent defense per arrest increased significantly during this period. The amount spent on district attorney offices per arrest is nearly double the amount spent on indigent defense. As shown in Figure 7, nearly $1,900 was spent on district attorney offices per arrest in 2018‑19, an increase of nearly $842 per arrest (or 82 percent) from 2009‑10. In contrast, about $1,000 was spent on indigent defense per arrest in 2018‑19, an increase of about $400 per arrest (or 65 percent) from 2009‑10. As shown in Figure 8, spending per arrest in 2018‑19 varies across counties, with greater variance in per arrest spending on district attorney offices as compared to indigent defense. This means that the magnitude of the difference in spending on district attorney offices and indigent defense can be much greater in certain counties. Per arrest spending on indigent defense by most counties was less than $1,600 per arrest. In contrast, per arrest spending on district attorney offices for almost three‑fourths of all counties was between $800 to $2,400 per arrest.

All three comparisons discussed above demonstrate greater levels of funding for district attorney offices than indigent defense. These comparisons also show that there is greater variation in resource levels for district attorney offices than indigent defense across counties. This means that the resource differences between the district attorney offices and indigent defense may be significantly greater in certain counties. These trends raise questions regarding whether defendants across the state are receiving similar levels of service and are likely to face similar outcomes (such as convictions or the amount of times spent in jail or prison).

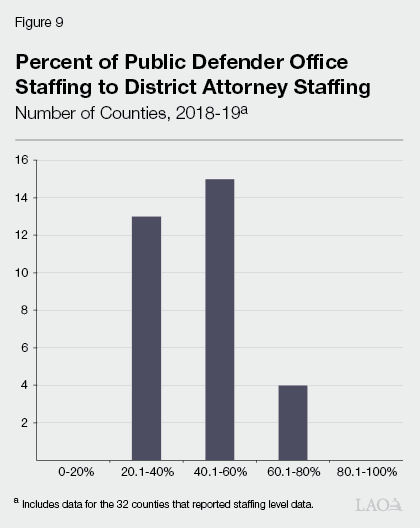

Differences in Total Staffing Levels. Staffing levels can provide a sense of the total number of people available to work on cases. In 2018‑19, counties reported significantly more employees in district attorney offices than in public defender offices across the state—10,500 employees compared to 4,305 employees. As shown in Figure 9, in 2018‑19, staffing levels in 28 of 32 counties with public defender officers were between 20.1 percent to 60 percent of those of their counterpart district attorney offices. Staffing levels in the remaining counties were between 60.1 percent to 80 percent of those of their counterparts.

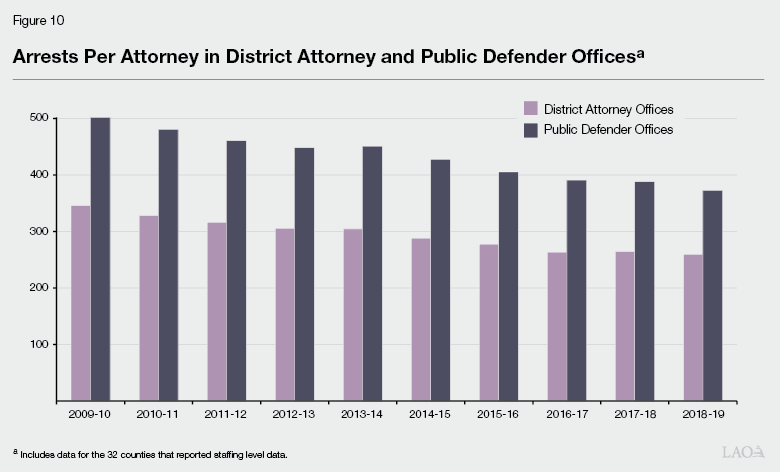

Differences in Caseloads. Caseloads can represent the amount of time attorneys have to spend with their clients to explore their cases or explain the potential ramifications of certain actions (such as accepting a plea deal for certain charges). This can impact the extent to which defense attorneys can fully litigate a case and whether defendants feel that they have been effectively represented. One method of comparing caseload is to examine the number of arrests to the number of attorneys for both district attorney offices and indigent defense. This is because arrests can be a strong indicator of potential workload given that prosecutors determine whether charges will be filed following arrest and indigent defense counsel is typically appointed within 48 hours of arrest. As shown in Figure 10, the number of arrests per attorney in district attorney and public defender offices in the 32 reporting counties declined between 2009‑10 an 2018‑19, indicating that caseloads were decreasing. However, the number of arrests per attorney in public defender offices were consistently higher across this period. In 2018‑19, there were 372 arrests per attorney in public defender offices and 260 arrests per attorney in district attorney offices.

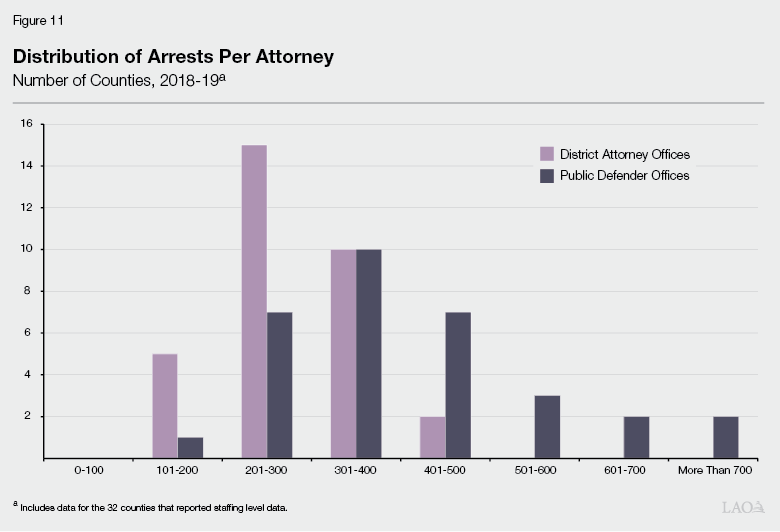

Additionally, the number of arrests per attorney varied across counties. As shown in Figure 11, in 2018‑19, arrests per attorney in 25 of 32 district attorney offices clustered between 201 to 400. Arrests per attorney in public defender offices reflected greater variation across counties, with 24 of 32 public defender offices reporting ranging between 201 to 500 arrests. This variation suggests that the difference between caseloads for public defender and district attorney offices can be much greater in certain counties, which raises questions regarding whether defendants across the state are receiving similar levels of service and quality of service.

Differences in Staffing Ratios. Every individual receiving indigent defense services is represented by an attorney. The availability of investigators, clerks, paralegals, social workers, and other staff to support attorneys can reduce the level of work that must be completed by attorneys as well as increase the level of service that is provided. For example, high attorney‑to‑investigator ratios—meaning each investigator must assist many attorneys—decreases the likelihood that there are sufficient investigators to fully examine or collect evidence to support a particular defense. As such, a common measurement of effective assistance of counsel often cited by stakeholders is the number of attorneys supported by each of the various classifications of support staff.

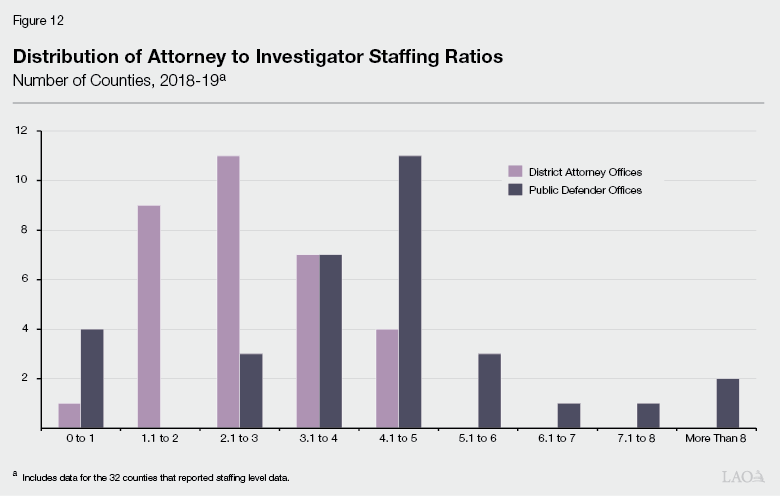

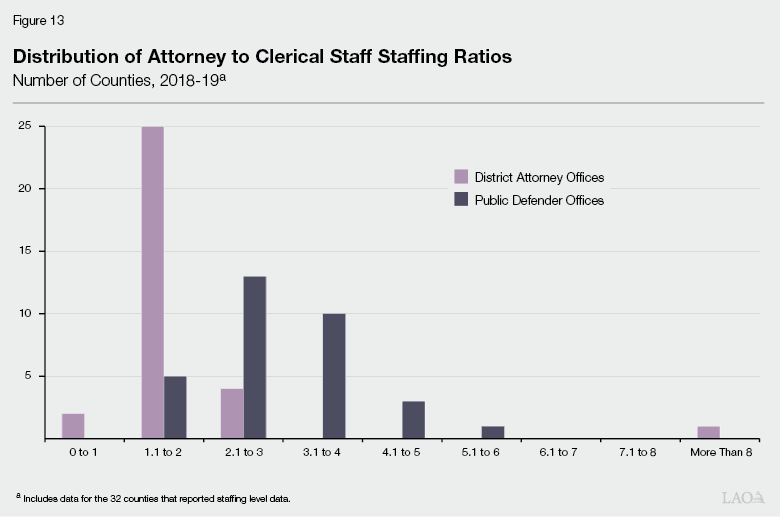

Figure 12 shows the distribution of the ratio of attorneys to investigators for the 32 counties that reported data for both public defender and district attorney offices. In 24 of the public defender offices, there were between 2.1 and 6 attorneys per investigator. In 27 of the district attorney offices, there were between 1.1 and 4 attorneys per investigator. Additionally, Figure 13 shows the distribution of the ratio of attorneys to clerical staff. In 23 of the public defender offices, there were between 2.1 and 4 attorneys per clerical staff. In contrast, in 29 of the district attorney offices, there were between 1.1 and 3 attorneys per clerical staff. In both of the investigator and clerical staff ratios, public defender offices generally had greater ratios than district attorney offices—meaning public defenders were assisted by fewer support staff. The data also show greater variation in the ratio of support staff to attorneys in public defender offices. This means that the magnitude of the difference in staffing levels between public defender and district attorney offices can be much greater in certain counties. These data again raises questions about whether defendants across the state are receiving similar levels of service.

Potential Justifications for Spending, Caseload, and Staffing Differences. In talking to stakeholders and reviewing papers on this topic, various opinions were offered to justify the differences in resources between district attorney offices and the indigent defense system, as well as the differences between counties in the level of resources provided to indigent defense. The lack of statewide, comprehensive, and comparable data, however, makes it difficult to fully assess these claims.

On the one hand, some assert that district attorney offices require more resources because they must determine whether or not individuals should be charged (and at what level) and must engage in various activities to demonstrate that defendants should be convicted. Additionally, some assert that certain district attorney offices support specific programs and activities—such as forensic laboratories or providing advice to grand juries—that may not be required by the indigent defense system. On the other hand, some assert that the indigent defense system needs similar or more resources than district attorney offices because the system does not have the benefit of significant support from other governmental entities—such as law enforcement agencies that investigate and present cases to district attorney offices or forensic laboratories that test potential evidence. Furthermore, some assert that more resources are also potentially necessary for the indigent defense system to fully investigate and effectively represent their clients. For example, indigent defense investigators and social workers may need to identify mitigating circumstances to help with obtaining less severe consequences for a defendant. Additionally, some assert that indigent defense attorneys are responsible for certain workload—such as resentencing filings, expungements, or mental health civil commitments—that requires significantly less or no workload from the district attorney office.

Since indigent defense workload is driven by local actions, there can also be major differences between counties in the levels of resources needed by the system. County priorities and funding decisions impact arresting, charging, and prosecutorial decisions that the indigent defense system must react to. For example, a District Attorney that sets office policies to limit early settlements of cases could mean that indigent defense attorneys must invest more time and resources to more fully investigate and defend their clients in order to limit incarceration. Similarly, county priorities and funding decisions in other local agencies can impact the level of resources that are available. For example, those counties that prioritize funding for mental health services, sheriff‑operated alternative custody programs, or other programs could have greater availability of diversion programs, collaborative courts, and alternatives to incarceration. This, in turn, could change how indigent defense attorneys represent their clients as they potentially have more options to address their clients’ cases. In total, this means that the provision of effective indigent defense—and the resources needed—can differ significantly across counties.

Recommendations

While there is a lack of consistent data and metrics to fully evaluate indigent defense service levels, the available data raise questions about the effectiveness of existing levels. This is particularly problematic given the potential that the state could be responsible for ensuring the provision of effective indigent defense. Below, we recommend steps that the Legislature could take to ensure it has the necessary information to determine whether a problem exists with indigent defense service levels, what type of problem exists, and how to effectively address the problem.

Define Appropriate Metrics to More Directly Measure the Quality of Indigent Defense. Having clearly defined metrics would dictate the specific data that needs to be collected in order to evaluate existing indigent defense service levels. Defining such metrics and data collection needs at the statewide level can also ensure that data is collected consistently, which would allow for accurate and fair comparisons across the state. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature statutorily define those metrics it believes are necessary to more directly evaluate the quality of indigent defense statewide. To assist with this, the Legislature could direct OSPD to convene a working group with key stakeholders (such as public defender offices and community‑based organizations) to make recommendations on appropriate metrics. The Legislature could also provide guidance to the working group to shape the scope of its work, such as defining the outcomes it desires from an effective indigent defense system or specifying the types of metrics it would like the group to evaluate and consider. Alternatively, the Legislature could contract with external researchers to help establish specific outcome and performance measures.

We further recommend that the metrics reflect the state’s definition of what constitutes effective legal assistance as well as expectations for meeting those goals. For example, the Legislature could determine that procedural justice (or the perception of a fair process) is equally important as legal effectiveness. This could then lead to the collection of certain data or metrics, such as data on whether defendants understood what was happening in their case and felt they were fairly represented. Additionally, if equity is a key legislative concern, the Legislature could require that metrics be broken out by key factors—such as by race, income, and/or type of offense—in order to enable assessment of whether and how certain groups are being disproportionately impacted by the level of resources supporting the indigent defense system and how indigent services are provided. This, in turn, could help identify areas where additional legislative action is warranted.

Require Counties Collect and Report Data. After identifying what data should be collected to directly measure indigent defense service levels, we recommend the Legislature require counties collect and report that data to OSPD. Such statewide reporting is critical to ensure the state has the necessary information to conduct oversight of how effectively indigent defense services are provided across the state. As part of this requirement, the state or OSPD should establish clear definitions for how to track and report data (such as ensuring that all jurisdictions count the number of cases in the same way). This would provide the state with comprehensive data that can be compared across counties. This, in turn, would provide a much clearer picture of whether indigent defense representation is resourced or provided in a manner that ensures effective assistance is being provided across the state. Such data could also help the state better understand some of the underlying reasons for the differences, where improvements can be made, and where policy changes or additional resources should be targeted. We note that such data could also help counties manage and improve how they operate their indigent defense systems. For example, such data could indicate that structuring and funding a public defender office in a particular way could generate more effective representation at a comparatively lower cost.

We acknowledge that state funding could be needed to collect and report such data, which we estimate could reach into the low tens of millions of dollars annually. However, we believe that it is critical for the state to receive accurate and comprehensive data in order to determine whether federal and state constitutional requirements are being met. Moreover, providing resources specifically for obtaining such data increases the likelihood that it is collected accurately and consistently. Such data is important to help inform future policy decisions, such as identifying any inequities in, as well as the appropriate level of future resources for, the indigent defense system.

Use Data to Determine Future Legislative Action. The data collected above would help the Legislature refine its specific definitions and goals for effective indigent defense levels as well as what actions are needed to take to achieve those goals. This could include the Legislature taking a stronger role to mitigate any negative differences in the provision of indigent defense services across the state. Such actions would dictate whether, and how much, additional state resources could be needed to support indigent defense. To the extent the Legislature determined that additional resources were necessary, the data could help the Legislature determine where and how to target such additional resources to maximize their impact.

If the state is interested in acting in this area, it has various options depending on its goals. Examples of such options are provided below. These are not mutually exclusive, which means that multiple actions could be taken.

- Establishing Statewide Standards. The Legislature could establish and require counties to meet certain statewide standards or authorize another entity (such as OSPD) to do so. These standards could focus on different areas of the indigent defense system and can differ in their specificity. Such standards could include minimum funding or staffing standards—such as requiring that prosecutors and indigent defense providers receive similar levels of funding or attorney‑to‑investigator ratios. Such standards could also include maximum caseloads based on case types as well as minimum outcome or quality standards.

- Grants. Grants could be provided to support start‑up costs for new technology or new programs, ongoing costs for specific activities (such as having indigent defense representation prior to arraignment) or specific costs (such as social workers), or to test or further expand innovative practices or programs (such as holistic defense teams). Grants can also be provided as incentives to improve performance or outcomes or to increase local spending (such as providing a state match for local spending above a certain level).

- Further Expansion of OSPD. As discussed above, the state recently took action to expand OSPD’s indigent defense responsibilities. After reviewing how OSPD has used its existing expanded authority, the state could further expand OSPD’s authority and responsibilities and provide it with additional resources. This could allow OSPD to, for example, provide further statewide trainings, conduct oversight of indigent defense providers and intervene where necessary, and/or provide representation at the local level.

- Evaluations. The Legislature could contract for evaluations to assess existing or new indigent defense practices. These could help the Legislature determine the most effective and equitable practices for providing indigent defense services. For example, certain counties operate holistic defense models while others do not. Others operate the model in different ways. Additionally, a new participatory defense model—in which the community actively participates in the defense of an individual—has been implemented in certain jurisdictions. Evaluations of these models, as implemented in California, could help identify their benefits and costs. This, in turn, could help the Legislature determine whether it would like to encourage or require that certain practices are implemented statewide. Similarly, such evaluations could help counties assess and improve how they provide indigent defense.

Conclusion

Indigent criminal defendants have the constitutional right to effective assistance of counsel provided by the government. California currently lacks comprehensive and accurate data directly measuring the effectiveness of the state’s indigent defense system. However, analysis of limited data raises questions about existing indigent defense service levels. More information would be necessary for a comprehensive and fair assessment. As such, we recommend the Legislature define the metrics necessary to more directly measure the quality of indigent defense currently provided; require counties collect and report the necessary data; and, finally, use that data to guide future legislative action.