LAO Contact

September 30, 2022

The 2022-23 California Spending Plan

The State Appropriations Limit

In the late 1970s, voters passed Proposition 4 (1979), which established appropriations limits on the state and most types of local governments. (These limits also are referred to as “Gann limits” in reference to one of the measure’s coauthors, Paul Gann.) The limits later were amended by Proposition 111, which voters approved in 1990. Over the past few years, the state appropriations limit (SAL) has become a major feature in budget architecture and constraint on the Legislature’s use of surplus funds. For more information about the history of the appropriations limit, and an analysis of why the SAL is impacting budget decisions today, see our previous reports, here: The State Appropriations Limit.

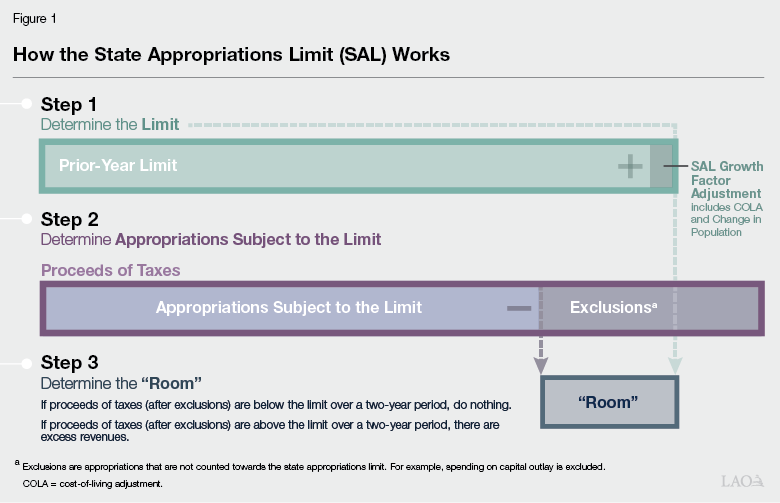

How the Formula Works. The SAL calculation involves comparing (1) the limit to (2) appropriations subject to the limit. Figure 1 shows the steps in the calculation. First, this year’s limit is calculated in Step 1 by adjusting last year’s limit for a growth factor that includes economic and population growth. In Step 2, appropriations subject to the limit are determined by taking all proceeds of taxes and subtracting excluded spending. In Step 3, the state compares the two. If appropriations subject to the limit are less than the limit, there is “room.” If appropriations subject to the limit exceed the limit (on net) over any two-year period, there are excess revenues.

How Does the State Meet the Constitutional Requirements Under the SAL? As implied by Figure 1, if appropriations subject to the limit are expected to exceed the limit, the Legislature can: (1) lower proceeds of taxes, (2) increase exclusions, or (3) split the excess revenues between additional school and community college district spending and taxpayer rebates. (Exclusions include: subventions to local governments, capital outlay projects, debt service, federal and court mandates, and certain kinds of emergency spending.)

Estimates of the Appropriations Limit

The SAL has two important components: the limit itself and appropriations subject to the limit. Both of these components are subject to estimate error, particularly for the budget year, and therefore change throughout the budget process. For example, the limit itself is based on estimates of personal income and population growth, which change based on economic and other conditions. In addition, appropriations subject to the limit change throughout the year depending on legislative decisions, administrative proposals regarding revenues and spending, and actual expenditures.

As a result, the estimates of whether state revenues would exceed the limit in the budget changed considerably over the course of the budget process. Figure 2 shows estimates of the appropriations limit, appropriations subject to the limit, and the resulting room under the limit at each point in the 2022-23 budget process. (Where applicable, the figure also shows excess revenues, which are calculated over a two-year period.)

Figure 2

Estimates of Appropriations Limit in 2022-23 Budget Process

|

Governor’s Budget |

May Revision |

Final Budget Act |

|||||||||

|

2020-21 |

2021-22 |

2022-23 |

2020-21 |

2021-22 |

2022-23 |

2020-21 |

2021-22 |

2022-23 |

|||

|

Appropriations limit |

$115,860 |

$125,695 |

$131,365 |

$115,860 |

$125,695 |

$135,637 |

$115,860 |

$125,695 |

$135,650 |

||

|

Appropriations subject to the limit |

134,858 |

109,303 |

125,675 |

132,624 |

106,296 |

139,052 |

133,036 |

96,907 |

123,452 |

||

|

Rooma |

-$18,998 |

$16,392 |

$5,690 |

-$16,764 |

$19,399 |

-$3,415 |

-$17,176 |

$28,788 |

$12,198 |

||

|

Excess Revenues |

-$2,606 |

No |

No |

||||||||

|

aA negative number indicates appropriations subject to the limit are above the limit. A positive number indicates the state has “room” under the limit. |

|||||||||||

Governor’s Budget. For 2020-21, the Governor’s budget reflected nearly $19 billion in “negative room,” meaning appropriations subject to the limit exceed the limit itself by this amount in this year. For 2021-22, the Governor’s budget reflected $16.4 billion in room—meaning appropriations subject to the limit are under the limit by this amount in this year. This means that, as the figure shows, at the time of the Governor’s budget, the administration estimated the state would have $2.6 billion in excess revenues associated with 2020-21 and 2021-22. The Governor’s budget did not include a proposal to address these excess revenues, but the administration stated it planned to put forward a plan to address these requirements at the May Revision.

May Revision. By the time of the May Revision, estimates of revenues subject to the limit had increased significantly. For example, for 2021-22, total SAL revenues and transfers increased from $223 billion at Governor’s budget to $256 billion at May Revision. As the figure shows, however, the May Revision did not reflect excess revenues across 2020-21 and 2021-22 because the administration also proposed a significant amount of new SAL-excludable spending, much of which was scored to 2021-22, that reduced appropriations subject to the limit. That said, as the figure also shows, the May Revision left $3.4 billion in unaddressed SAL requirements in 2022-23.

Final Budget Act. The final budget package does not reflect excess revenues across 2020-21 and 2021-22, nor does it include any unaddressed SAL requirements for 2022-23. In particular, as of July 2022, the administration estimates 2020-21 ended with appropriations subject to the limit above the limit by $16 billion. However, 2021-22 more than offsets this difference with positive room of $29 billion, for a net position of $13 billion in room across the two years. Further, under the spending plan, the administration estimates the state would have $12 billion in room in 2022-23. One of the key reasons for this change is the increase in SAL-excluded spending in the final spending plan. While we estimated the May Revision included $35 billion in discretionary spending that meets SAL requirements, the budget act includes $48 billion in discretionary SAL-excluded spending.

Major SAL-Related Decisions in the 2022-23 Budget Act

Excluded Spending

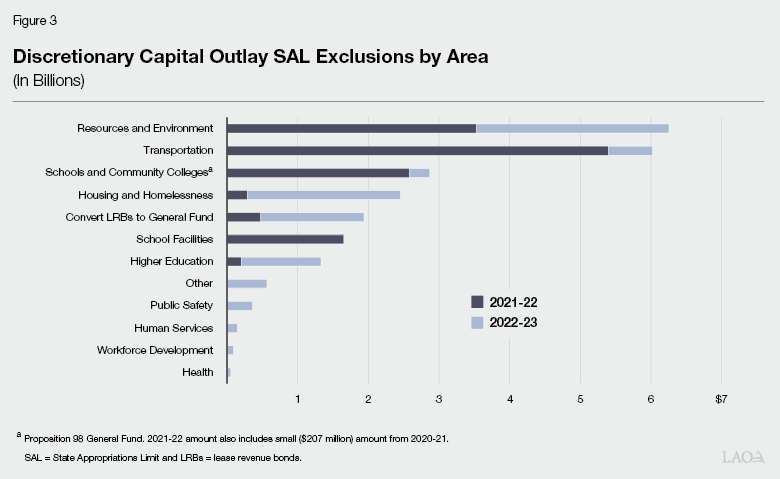

$23.7 Billion in Qualified Capital Outlay Spending. The Constitution allows expenditures on capital outlay projects to be excluded from appropriations subject to the limit. The spending plan includes $23.7 billion in discretionary spending (and debt repayments) that are excluded from the SAL (including $2.9 billion Proposition 98 General Fund and $20.9 billion non-Proposition 98 General Fund). Figure 3 shows how this capital outlay spending is distributed by policy area and year. Of this total, $14.1 billion is appropriated to 2021-22 and $9.6 billion is appropriated to 2022-23. By policy area, most SAL exclusions are dedicated to resources and environment, transportation, and schools and community colleges.

$9.5 Billion in Taxpayer Rebates. The Constitution allows refunds of taxes to be excluded from appropriations subject to limit (see: Section 8(a) of Article XIIIB of the California Constitution). As a result, these types of tax refunds are scored as spending rather than revenue reductions. The spending plan includes $9.5 billion General Fund for a one-time payment, the Better for Families tax refund. Payments will be made to taxpayers with adjusted gross income (AGI) below $500,000 (for joint filers) and $250,000 (for single filers). The payment amount is based on AGI, with larger payments going to taxpayers with lower income levels.

Emergency Expenditures. The Constitution allows expenditures on emergencies to be excluded from appropriations subject to the limit. Those expenditures must meet three specific conditions to qualify. Specifically, the spending must be: (1) related to an emergency declaration by the Governor, (2) approved by a two-thirds vote of the Legislature, and (3) dedicated to an account for expenditures relating to that emergency. The spending plan includes emergency spending from two different funds:

Emergency Spending Through California Emergency Relief Fund (CERF). Chapter 3 of 2022 (SB 113, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) created the CERF, a special fund related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Appropriations from this fund authorized with a two-thirds vote of the Legislature are excluded from the SAL. We understand the CERF includes direct COVID-19 response expenditures of $1.9 billion in 2021-22 and $2.5 billion in 2022-23, nearly $2 billion in emergency rental relief assistance (in 2021-22), just over $1 billion for healthcare worker retention payments (in 2021-22), $1.2 billion for energy utility arrearages (in 2022-23), and $1.1 billion for drought emergency expenditures ($1 billion in 2021-22). (We are still waiting for final information from the administration on overall spending in the CERF.)

Emergency Spending Through Learning Recovery Emergency Fund. Chapter 53 of 2022 (AB 182, Committee on Budget) created the Learning Recovery Emergency Fund, a special fund to assist schools and community colleges in the long-term recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Appropriations from this fund authorized with a two-thirds vote of the Legislature are excluded from the SAL. The spending plan includes $8.6 billion in Learning Recovery Block Grant funding, which counts toward the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. Of this, $7.9 billion is to be allocated to K-12 schools for a variety of academic and social-emotional activities, including increasing instructional learning time and providing tutoring. The remaining $650 million is to be allocated to community colleges for various purposes, including enhanced instructional and student support services as well as professional development for faculty teaching online classes. The K-12 funds are to be distributed based on the number of low-income students and English learners in each district, while community college funds are to be distributed based on overall enrollment in each district (as measured by the number of full-time equivalent students).

Other Excluded Spending. The Constitution requires subventions to local governments to be counted against that local government’s limit (instead of the state’s limit). The Constitution also requires federal and court-mandated spending to be excluded from appropriations subject to the limit. The spending plan includes about $800 million in new discretionary spending that counts as a subvention and $115 million in new discretionary spending that counts as a federal or court mandate. (The spending plan also begins excluding billions of dollars in existing spending as subventions as a result of an expansion of the definition of subvention, which we discuss in the next section.)

Additions to the Definition of Subvention

Last Year’s Budget Reflected Intent to Count Realignment Revenues as Subventions. The 2021-22 budget package reflected the intent of the Legislature to count realignment revenues to local government against local governments’ limits, in accordance with changes in the state-local fiscal relationship that have occurred since 1980. This change resulted in an additional $12.2 billion in room in 2021-22. In addition, Chapter 77 of 2021 (AB 137, Committee on Budget) prevented local governments from exceeding their appropriations limit as a result of state subventions.

This Year’s Budget Expanded the Definition of Subvention for SAL-Related Purposes. This year’s budget built on these changes to expand the definition of subvention also to include a variety of other specific streams of funds, as listed in Government Code 7903. Under Chapter 48 of 2022 (SB 189, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), subventions now include, for example, funds to counties for the administration of health and human services programs like Medi-Cal, Mental Health Services Act funding, and many other local grant programs across a broad range of issue areas. In addition, the new law requires local agencies to identify and report any new state subventions that would cause that entity to exceed its own appropriations limit so that the state can continue to count those amounts at the state level instead.

Other Technical Adjustments

Counts More School District Capital Outlay Expenditures. School districts, like local governments and the state, have their own appropriations limits. State law requires most school districts to set aside a portion of their general-purpose funding for the ongoing and major maintenance of their facilities. Districts currently set aside approximately $2.2 billion per year related to this requirement. These funds meet the definition of capital outlay for SAL purposes, and so the spending plan adopts a plan to require school districts to exclude this spending from their limits. Because of the way school district limits interact with the state’s limit, excluding this change results in dollar-for-dollar reductions in appropriations subject to the limit at the state level.

Counts Certain Information Technology (IT) Project Costs as Excluded. While previous spending plans did not characterize IT expenditures as excludable from the SAL, the administration now identifies some specific IT expenditures as a type of capital outlay, and therefore excludable. The nearby box describes the administration’s IT exclusion SAL methodology in more detail.

IT Expenditure SAL Exclusion Methodology

Specific IT Expenditures Now Identified as Qualified Capital Outlay Excluded From SAL. Applying the administration’s new methodology incorporated in the Governor’s May Revision budget, the spending plan identifies information technology (IT) expenditures totaling $226.5 million General Fund in 2021-22 and $478.8 million General Fund in 2022-23 as expenditures on qualified capital outlay that are excluded from the state appropriations limit (SAL) calculation. These excluded expenditures include most IT project development and implementation costs (excluding, for example, independent verification and validation services and training costs) and software licensing costs. Some costs for the ongoing development and operation of larger IT systems (once completed as IT projects) also were excluded from SAL. (For example, some of the development and operations costs for the California Health Eligibility, Enrollment, and Retention System are considered SAL excludable.)

Administration’s Methodology Might Exclude Additional IT Expenditures Over Time. The administration’s May Revision methodology for identifying and excluding some IT expenditures from SAL might be revised over time to exclude additional expenditures. Some IT expenditures are not readily identifiable from the current reports required by both the California Department of Technology and the Department of Finance for proposed and approved IT projects or systems, so some changes in reporting requirements likely will be required to exclude more expenditures.