LAO Contact

Update (11/22/22): The original version of this report identified a $25 billion—instead of a $24 billion—budget problem, which reflected an error in the way we accounted for student housing grant program funding.

November 16, 2022

The 2023‑24 Budget

California’s Fiscal Outlook

- Introduction

- Economic Conditions Weigh on Revenues

- The Budget Problem

- Inflation‑Related Adjustments Vary Across Budget

- Save Reserves for a Recession

- Appendix

Executive Summary

Economic Conditions Weigh on Revenues. Facing rising inflation, the Federal Reserve—tasked with maintaining stable price growth—repeatedly has enacted large interest rate increases throughout 2022 with the aim of cooling the economy and, in turn, slowing inflation. The longer inflation persists and the higher the Federal Reserve increases interest rates in response, the greater the risk to the economy. The chances that the Federal Reserve can tame inflation without inducing a recession are narrow. Reflecting the threat of a recession, our revenue estimates represent the weakest performance the state has experienced since the Great Recession.

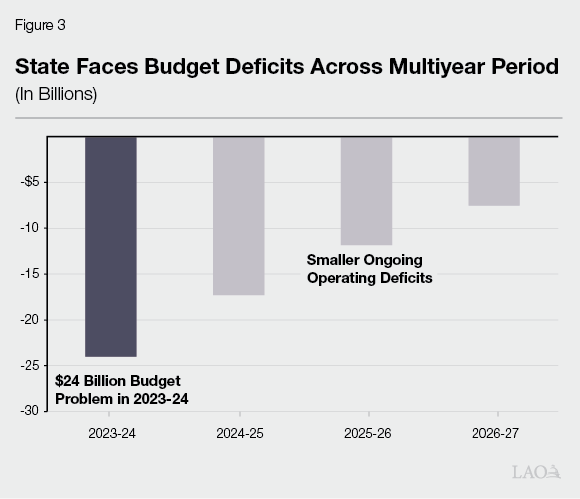

State Faces $24 Billion Budget Problem and Ongoing Deficits. Under our outlook, the Legislature would face a budget problem of $24 billion in 2023‑24. (A budget problem—also called a deficit—occurs when resources for the upcoming fiscal year are insufficient to cover the costs of currently authorized services.) The budget problem is mainly attributable to lower revenue estimates, which are lower than budget act projections from 2021‑22 through 2023‑24 by $41 billion. Revenue losses are offset by lower spending in certain areas. Over the subsequent years of the forecast, annual deficits would decline from $17 billion to $8 billion.

Inflation‑Related Adjustments Vary Across Budget. The General Fund budget can be thought of in two parts: (1) the Proposition 98 budget for schools and community colleges, representing about 40 percent of General Fund spending, and (2) everything else. Under our estimates, the state can afford to maintain its existing school and community college programs and provide a cost‑of‑living adjustment of up to 8.38 percent in 2023‑24. The extent to which programs across the rest of the budget are adjusted for inflation varies considerably. Because our outlook reflects the current law and policy of the Legislature, our spending estimates only incorporate the effects of inflation on budgetary spending when there are existing policy mechanisms for doing so. Consequently, our estimate of a $24 billion budget problem understates the actual budget problem in inflation‑adjusted terms.

Save Reserves for a Recession. The $24 billion budget problem in 2023‑24 is roughly equivalent to the amount of general‑purpose reserves that the Legislature could have available to allocate to General Fund programs ($23 billion). While our lower revenue estimates incorporate the risk of a recession, they do not reflect a recession scenario. Based on historical experience, should a recession occur soon, revenues could be $30 billion to $50 billion below our revenue outlook in the budget window. As such, we suggest the Legislature begin planning the 2023‑24 budget without using general purpose reserves.

Recommend Legislature Identify Recent Augmentations to Pause or Delay. Early in 2023, we suggest the Legislature question the administration about the implementation and distribution of recent augmentations. If augmentations have not yet been distributed, the Legislature has an opportunity to reevaluate those expenditures. Moreover, in light of the magnitude of the recent augmentations, programs may not be working as expected, capacity issues may have constrained implementation, or other unforeseen challenges may have emerged. To address the budget problem for the upcoming year, these cases might provide the Legislature with areas for pause, delay, or reassessment.

Introduction

Each year, our office publishes the Fiscal Outlook in anticipation of the upcoming state budget process. The goal of this report is to help the Legislature begin crafting the 2023‑24 budget. Our analysis relies on specific assumptions about the future of the state economy, its revenues, and its expenditures. Consequently, our estimates are not definitive, but rather reflect our best guidance to the Legislature based on our professional assessments as of November 2022. This year’s report addresses four main topics for lawmakers:

- Economic Conditions and the Revenue Picture. We discuss the implications of persistently high inflation for the economy and, in turn, the effects of the economic environment on our revenue estimates. In short, although our revenue estimates do not assume a recession occurs, they are lower than budget act estimates due to the heightened risk of an economic downturn.

- The Budget Problem. We then discuss the implications of lower revenue estimates for the budget condition in 2023‑24 and beyond. Specifically, lower revenues are expected to lead to a deficit of $24 billion in the budget window. Over the subsequent years of the forecast, annual deficits decline from $17 billion to $8 billion.

- The State Budget and Inflation. We also discuss the implications of persistently high inflation on the state’s spending programs. Given that many program areas do not account for inflation without direct legislative action, we advise the Legislature keep in mind the programmatic impacts of inflation as it considers budget solutions to address the deficit.

- Reserves. We conclude with a discussion of the state’s reserves, which are the key tool the state has available to address budget problems. We urge lawmakers to begin planning the 2023‑24 budget without using general purpose reserves and, instead, to save those reserves for when the state faces a recession.

Economic Conditions Weigh on Revenues

Booming Economy Has Led to High Inflation. Spurred by pandemic‑related federal stimulus, the U.S. economy entered a period of rapid expansion in the summer of 2020 that extended through 2021. Over the last year, however, evidence has mounted that this rapid economic expansion was unsustainable. Amid record low unemployment and continued global supply chain challenges, businesses have strained to meet surging consumer demand. As a result, consumer prices have risen 8 percent over the last year, more than three times the norm of the last three decades.

Efforts to Tame Inflation Are Slowing the Economy. Facing rising inflation, the Federal Reserve—tasked with maintaining stable price growth—repeatedly has enacted large interest rate increases throughout 2022 with the aim of cooling the economy and, in turn, slowing inflation. Higher interest rates dampen economic activity by increasing borrowing costs for home buyers, consumers, and businesses, as well as depressing the value of riskier assets like stocks. The impacts of recent interest rate hikes are apparent in certain areas of the economy: home sales have dropped by one‑third, car sales are at the lowest level in over a decade, and stock prices are down 20 percent from recent highs. Some impacts also can be seen in state tax collections. For example, estimated income tax payments for 2022 so far have been notably weaker than 2021, likely due in part to falling stock prices.

Inflation Pressures Remain, Raising Risk of a Recession. While these slowdowns in certain areas of the economy have not yet spread more broadly, similar historical episodes have ended in recessions. The longer inflation persists and the higher the Federal Reserve increases interest rates in response, the greater the risk to the economy. The chances that the Federal Reserve can tame inflation without inducing a recession are narrow. Despite recent interest rate increases, inflation remains well above the Federal Reserve’s stated price stability goal. Further, factors that tend to predict future inflation—such as recent changes in consumer spending, incomes, and prices for food and energy—suggest that heightened inflation pressures could remain for some time. These observations suggest that the Federal Reserve will take additional steps to curb inflation in the coming months, further raising the risk of a recession.

Economic Environment Creates Challenges for the Legislature. The current economic environment poses a substantial risk to state revenues. In the past, when economic conditions have been similar to today, revenues subsequently have tended to decline. This presents the Legislature with the challenge of balancing two key risks when selecting a revenue assumption for the 2023‑24 budget. On the one hand, adopting overly optimistic revenues which fail to account for the potential of an economic downturn would create a high risk of shortfalls in future years. On the other hand, while it appears likely a recession will occur, it is far from certain. Further, the exact timing and severity of a possible recession are unknowable. Because of this, adopting revenues consistent with the abrupt onset of a recession would run the risk of making cuts to public services before they are necessary.

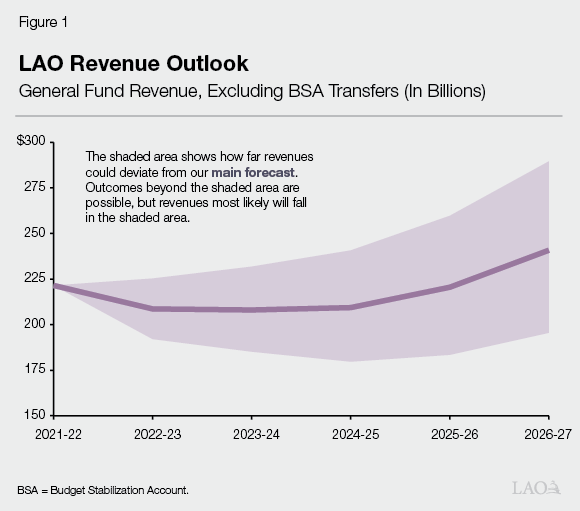

Fiscal Outlook Revenues Balance Competing Risks. Our revenue outlook—displayed in Figure 1—weighs equally the risks of excess optimism and excess pessimism. Reflecting the threat of a recession, our revenue estimates represent the weakest performance the state has experienced since the Great Recession. At the same time, our revenues stop short of reflecting an abrupt recession. Were a recession to occur soon, revenue declines in the budget window very likely would be more severe than our outlook.

The Budget Problem

In this section, we describe our estimates of California’s budget condition in the near term (in 2023‑24) and over a multiyear period (through 2026‑27). Over both time horizons, we expect the state will face deficits, also known as budget problems.

Budget Year

We Anticipate the Legislature Faces a Budget Problem of $24 Billion in Upcoming Year. Figure 2 shows that, under our revenue estimates, the state would have a budget problem of $24 billion in 2023‑24. The nearby box describes what the term “budget problem” means in more detail. As the figure shows, the state also would end 2023‑24 with nearly $22 billion in the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA)—the state’s general‑purpose reserve. These funds are available to address a budget emergency. (Under the State Constitution, the Governor can declare a budget emergency when estimated resources in the current or upcoming fiscal year are insufficient to keep spending at the level of the highest of the prior three budgets, adjusted for inflation and population. The Legislature cannot access the BSA without this declaration.)

Figure 2

General Fund Condition Under Fiscal Outlook

(In Millions)

|

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$38,334 |

$19,885 |

‑$1,166 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

224,089 |

208,280 |

208,252 |

|

Expenditures |

242,539 |

229,331 |

226,486 |

|

Ending Fund Balance |

$19,885 |

‑$1,166 |

‑$19,400 |

|

Encumbrances |

$4,276 |

$4,276 |

$4,276 |

|

SFEU Balance |

$15,609 |

‑$5,442 |

‑$23,676 |

|

Reserves |

|||

|

BSA balance |

$21,925 |

$21,925 |

$21,925 |

|

Safety Net Reserve |

900 |

900 |

900 |

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties. |

|||

What Is a Budget Problem?

A budget problem—also called a deficit—occurs when resources for the upcoming budget are insufficient to cover the costs of currently authorized services. As such, calculating the budget problem involves two main steps:

- Projecting Anticipated Revenues. First, we estimate how much revenue will be available for the remainder of the current and upcoming year. This means using assumptions about how the economy is likely to perform over the coming 20 months and then using those assumptions to project revenue collections.

- Estimating Current Service Level. Second, we compare those anticipated revenues to the level of spending to support the current service level under the state’s current law and policy. Projecting current service spending, which we also call “baseline spending,” has several components. For example, it requires us to project how caseload will change for means‑tested programs, estimate how much federal funding will come to the state based on current federal policy, and make many other assessments.

When current service level spending exceeds anticipated revenues, the state has a budget problem. In this document, the budget problem is reflected in the 2023‑24 ending balance in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties, shown in Figure 2.

Budget Problem Must Be Addressed. The State Constitution requires the Legislature to pass a balanced budget. As a result, if—earlier in the process—the state faces a budget problem, the Legislature must solve the problem using a combination of tools. In a recession, the main tool for solving a budget problem is the state’s reserve. If reserves are insufficient to cover the budget problem, however, the Legislature must take other actions to bring the budget into balance. These actions include reducing spending, increasing revenues, and/or shifting costs, for example, between funds, time periods, or entities of government.

Budget Problem Driven by Lower Revenue Estimates. The budget problem for 2023‑24 mainly is attributable to lower revenue estimates. More specifically, however, the budget problem arises as a result of the offsetting effects of five main factors:

- Planned Deficit of Nearly $3 Billion for 2023‑24. Under the 2022‑23 Budget Act assumptions, the state would have ended 2023‑24 with a deficit of nearly $3 billion in 2023‑24. Revenue losses compound this already negative starting point.

- Revenues Losses Add to Deficit by $41 Billion. Across 2021‑22, 2022‑23, and 2023‑24, our estimates of revenues and transfers (excluding transfers to the BSA) are lower than budget act projections by $41 billion.

- Formula‑Driven Spending on Schools and Community Colleges Offsets Revenue Losses by $13 Billion. General Fund spending on schools and community colleges is determined by a set of constitutional formulas under Proposition 98 (1988). Under our outlook, the state allocates about 40 percent of General Fund revenue to K‑14 education each year of the budget window. Relative to budget act estimates and consistent with lower revenue, our estimate of required General Fund spending on schools and community colleges for 2021‑22 through 2023‑24 decreases by $13 billion.

- Formula‑Driven BSA Deposits Offset Revenue Losses by an Additional $5 Billion. Relative to the budget act, under our revenue estimates, the state’s required deposits into the BSA would be lower by $5 billion across the three‑year period. This decline is driven by three factors: (1) higher capital gains revenues in 2021‑22 result in a $1.6 billion increase in the deposit that year; (2) significantly lower revenues in 2022‑23 cause that year’s $3.4 billion deposit to be reduced to zero; and (3) our assumption that the state suspends the otherwise required BSA deposit in 2023‑24, due to the budget problem, originally estimated to be $2.9 billion.

- Other Spending Lower by Nearly $3 Billion. Across the rest of the budget, our estimates of spending are lower than the administration’s by $2.6 billion across the three‑year period. This figure reflects the net effect of a number of different factors moving in both directions.

Under Our Revenue Estimates, No SAL Requirement in 2023‑24. In recent years, the state appropriations limit (SAL) has placed considerable limitations on how the Legislature can use revenues that exceed a specific threshold. Mainly due to lower revenues, the SAL is less likely to be a significant constraint in this year’s budget process. The box below describes our SAL estimates for 2022‑23 and over the multiyear period.

November 2022 State Appropriations Limit (SAL) Estimates

How the SAL Works. The SAL calculation involves comparing (1) the limit to (2) appropriations subject to the limit. The limit is calculated by adjusting last year’s limit for a growth factor that includes economic and population growth. Appropriations subject to the limit are determined by taking all proceeds of state taxes and subtracting excluded spending. If appropriations subject to the limit are less than the limit, there is “room.” If the converse is true, the state has a SAL requirement. The Legislature can meet SAL requirements in one of three ways: (1) lowering proceeds of taxes (for example, by providing taxpayer rebates), (2) spending more on excluded purposes (for example, for capital outlay or funding to local governments), or (3) issuing taxpayer rebates and providing more funding to schools and community colleges. For more information about the SAL and its recent implications on the state budget, see our reports The State Appropriations Limit and The 2022‑23 Budget: State Appropriations Limit Implications.

Under LAO Revenue Estimates, State Has Room Across the Budget Window… Under our estimates of revenues and spending, including special funds, the state would have room of $27 billion in 2021‑22 and $23 billion in 2022‑23. In 2022‑23, this is somewhat more room than was anticipated at budget act, mainly due to lower General Fund revenues. In 2023‑24, the state still would have $19 billion in room due to a few factors: (1) relatively flat General Fund tax revenues, (2) continued capital outlay spending from recent budget acts, (3) modest growth in other baseline exclusions, and (4) some growth in the limit itself.

…But if Revenues Grow Again, State Most Likely Would Face SAL Requirements Again. Under our multiyear outlook, the state would have much less room in 2024‑25, about $4 billion, and then face SAL requirements in 2025‑26 and 2026‑27 of $4 billion and $18 billion, respectively. These SAL requirements occur largely because our estimates of General Fund tax revenues grow faster than the limit itself in these years. Under our outlook, the state also would face budget deficits in these years, making these SAL requirements considerably more difficult to address. That said, while these estimates are highly uncertain and revenues could be significantly higher or lower than our estimates in any given year, on a long‑term basis, we expect the state to continue to reach the limit. This will reoccur because historical revenue growth rates exceed the growth in the limit itself.

Multiyear

State Faces Operating Deficits Over the Multiyear Period. Figure 3 displays our estimates of the budget’s condition over the outlook period. As the figure shows, in addition to the $24 billion budget problem the state faces in 2023‑24, the state faces annual operating deficits which decline from $17 billion to $8 billion by 2026‑27. The remainder of this section describes some of the key multiyear trends that result in these bottom line estimates.

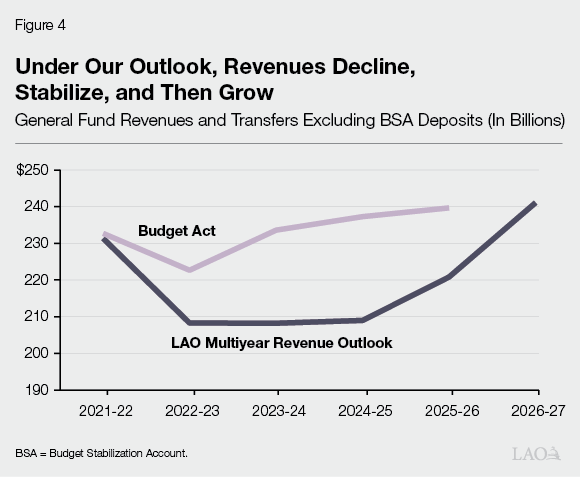

Revenues Decline, Stabilize, and Then Grow. The key assumption underlying our multiyear outlook is our estimate of revenues. As we discussed earlier, our revenue outlook balances competing risks. It reflects the threat of a downturn, but stops short of reflecting an abrupt recession. As Figure 4 shows, we anticipate revenues will decline between 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 by more than the budget act anticipated, but then remain largely flat between 2022‑23 and 2024‑25, before growing again in the last two years of the outlook.

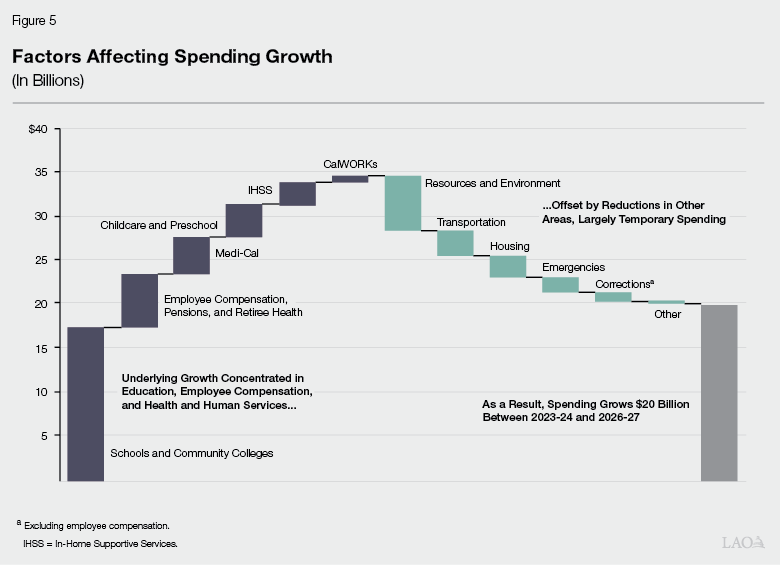

Significant Underlying Program Growth Somewhat Offset by Reductions in Temporary Spending. We estimate spending growth assuming current law and policy remains in place, meaning we assume the Legislature enacts no new policies over the period. Under our assumptions, General Fund spending would grow from $227 billion in 2023‑24 to $246 billion in 2026‑27—an increase of about $20 billion or an average annual growth of 2.9 percent. (The next section describes some of the other major spending assumptions that are embedded in these estimates, including specific differences with the administration’s budget act assumptions.) The relatively slow overall growth in expenditures is the result of many offsetting factors, shown in Figure 5. Namely, faster growth in ongoing programs, such as in education, employee compensation, and health and human services programs, would total nearly $35 billion over the period. But this growth is offset by about $15 billion in lower spending in other areas—including in natural resources, transportation, and housing. In these areas, the state allocated significant portions of recent budget surpluses to temporary augmentations, which “turn off” over the period, resulting in declines relative to the 2023‑24 level.

Recent Budgets Committed to Growing Ongoing Augmentations. The spending growth in Figure 5 reflects a combination of underlying program growth and recent legislative augmentations. While recent budgets have committed a significant share of new spending to one‑time or temporary purposes, those budgets also consistently allocated some funds to ongoing purposes—many of which grow significantly. For example, the 2021‑22 budget allocated $3.4 billion to new, ongoing spending, expected to grow to about $12 billion by 2025‑26. Similarly, the 2022‑23 budget allocated $2.3 billion to new, ongoing spending, expected to grow to nearly $5 billion by 2026‑27. With mostly flat revenue growth, these recent, sizeable, ongoing augmentations place significant pressure on the out‑year condition of the budget.

Major Spending Assumptions

Our Fiscal Outlook reflects current law and policy. This means our spending estimates incorporate the fiscal effects of all enacted policies. In addition, we include the fiscal effects of those policies which the Legislature has repeatedly enacted (absent statutory commitments to ongoing spending). The remainder of this section describes some of the other key spending assumptions in this Fiscal Outlook.

Assume Spending Enacted With Clear Legislative Intent Occurs... In the Fiscal Outlook, we aim to estimate the costs of the state’s commitments under current law and policy. For this analysis, we include the costs associated with legislative intent language as current policy if it meets certain conditions. Specifically, (1) the Legislature voted on and approved the policy, (2) the policy is included in budget‑related statutes (for example, in trailer bill) that have force of law, and (3) the policy as described in statute is specific and implementable.

…Which Results in Some Differences With the Administration. The administration’s spending estimates at the time of the budget act included some expenditures that did not meet these criteria. Consequently, those items are not included in our expenditure estimates. The largest expenditures included in the administration’s estimates but excluded from our analysis are: (1) spending $1.7 billion to accelerate the repayment of bond debt service in 2024‑25, (2) setting aside additional reserve deposits of $1 billion in 2024‑25 and $3 billion in 2025‑26, and (3) spending $1.9 billion in 2023‑24 to shift capital outlay projects currently authorized for lease revenue bonds to General Fund cash. In addition, the administration included an unallocated set aside for inflation‑related costs in their estimates. We do not make a similar adjustment because those costs do not reflect current law and policy. (If we had included these amounts in baseline spending, the budget problem would have been larger.) On the other hand, we do reflect spending on school facilities of $2 billion in 2023‑24 and $875 million in 2024‑25, and broadband spending of $300 million in 2023‑24 and $250 million in 2024‑25, in which enacted legislative intent language met our criteria.

Assume BSA Deposit and Infrastructure Spending Requirement Are Not Suspended After 2023‑24. Under the constitutional rules of Proposition 2 (2014), the state must make annual payments toward certain state debts, deposits into the BSA, and, in some years, infrastructure payments. While the debt payments are required until 2029‑30 regardless of the condition of the budget, BSA deposits and infrastructure payments can be suspended if the state faces a budget emergency. Our outlook assumes these payments are suspended in 2023‑24, but not in 2024‑25 or later. That said, in at least one of these years, the Legislature might have the option to suspend deposits and infrastructure spending if certain conditions are met. Suspending BSA deposits and infrastructure spending would result in an improvement in the budget condition by an average of roughly $1 billion each year.

Make CalPERS Contribution Assumptions Consistent With Recent Experience and LAO Forecasts. Our outlook assumes the state makes required pension contributions to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) based on the most recent actuarial valuation—in this case, as of June 30, 2021, which establishes the state’s contribution rates for 2022‑23. Using CalPERS’ online tool, we adjust these contribution rates based on recent investment returns, our assessment of economic conditions, and expected Proposition 2 debt repayments under our forecast. The net effect of these assumptions is that the outlook assumes that state pension contribution rates are significantly higher than the projected rates published in CalPERS’ most recent actuarial valuation. Specifically, annual General Fund contributions to CalPERS would be higher by $1.7 billion by the last year of our outlook. (A corresponding upward adjustment to The California State Teachers’ Retirement System was not necessary due to differing funding mechanisms and investment returns.)

Assume Enhanced Federal Match for Medicaid Ends Midway Through 2022‑23. Medicaid is an entitlement program whose costs generally are shared between the federal government and states. In 2020, Congress approved a temporary 6.2 percentage point increase in the federal government’s share of cost for most state Medicaid programs. This funding enhancement lasts until the end of the quarter in which the national public health emergency (PHE) declaration ends. For the purposes of this analysis, we assumed the declaration would expire in January 2023, resulting in an increase in General Fund costs of Medicaid programs in the fourth quarter of 2022‑23. However, as we completed this analysis, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services did not notify states the PHE would end in January. Given the federal administration committed to providing states 60 days’ notice regarding the end of the public health emergency, the PHE is likely to remain in place after January 2023. We estimate a one‑quarter extension results in lower General Fund costs of about $450 million—improving the budget bottom line condition by that amount (this figure is subject to uncertainty).

Inflation‑Related Adjustments Vary Across Budget

The General Fund budget can be thought of in two parts: (1) the Proposition 98 budget for schools and community colleges, representing about 40 percent of General Fund spending, and (2) everything else. In this section, we discuss the budget conditions of each of these parts of the budget—accounting for inflation—and the implications of those differences.

Under Proposition 98 Estimates, State Can Maintain Program Spending to Schools Even Adjusted for Inflation. Under our outlook, the Proposition 98 funding requirement for schools and community colleges is $108.2 billion ($78 billion General Fund) in 2023‑24, a decrease of $2.1 billion (2 percent) compared with the enacted 2022‑23 level. Despite this decrease, the state could afford to maintain its existing school and community college programs and provide a cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) of up to 8.38 percent in 2023‑24. (This COLA represents a slight reduction in the statutory rate that would apply if the Proposition 98 funding requirement were larger.) The key reasons this COLA can be afforded are: (1) the June budget allocated a sizeable amount of funding to one‑time activities, which expire in 2023‑24; (2) program costs decline from 2022‑23 to 2023‑24 due to an adjustment for school attendance; and (3) a constitutionally required withdrawal from the Proposition 98 Reserve supplements the regular Proposition 98 funding level. The nearby box gives more detail about the out‑year condition of the Proposition 98 budget.

Proposition 98 Multiyear Outlook

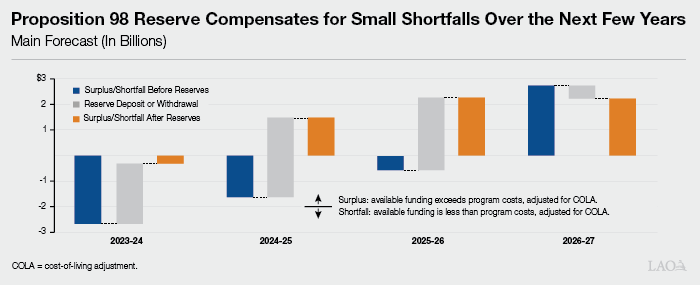

Proposition 98 Establishes “Budget Within a Budget.” By requiring the state to set aside certain amounts of funding, Proposition 98 (1988) creates a budget for schools and community colleges within the state’s larger budget. The minimum size of this budget—the “minimum guarantee”—is determined by a set of constitutional formulas. Individual school and community college programs, in turn, are paid out of this budget. A “shortfall” in the context of the Proposition 98 budget means that funding under the guarantee is insufficient to cover the costs of existing educational programs, as adjusted by changes in student attendance and inflation. A “surplus,” by contrast, means that the guarantee exceeds these program costs.

Guarantee Grows Over the Outlook Period. Our estimate of the total Proposition 98 spending on schools and community colleges in 2022‑23 is $106.7 billion ($78.6 billion from the General Fund and $28.1 billion from local property taxes). The minimum funding requirement grows by an average of $5.6 billion (4.9 percent) per year over the next four years. Most of this growth comes from the state General Fund, but increases in local property tax revenue also contribute. The increases in the guarantee are relatively slow early in the period and faster near the end.

Growth in General Fund Portion of the Guarantee Driven by Three Factors. The General Fund portion of the guarantee grows by $16.7 billion from 2022‑23 to 2026‑27. Most of this increase reflects our General Fund revenue estimates, with the constitutional formulas generally directing about 40 percent of state revenue growth toward the Proposition 98 guarantee. Our estimates also account for two smaller adjustments: (1) an increase of $2.6 billion for the expansion of transitional kindergarten and (2) an increase of approximately $1 billion beginning 2023‑24 to fund arts education (based on preliminary Proposition 28 results).

Reserve Withdrawals Compensate for Small Shortfalls. The figure summarizes the overall condition of the Proposition 98 budget under our forecast. The negative blue bars early in the period correspond with small shortfalls. Reserve withdrawals, however, reduce the shortfall in 2023‑24 and eliminate it entirely in the following two years. (Proposition 2 [2014] created a reserve for schools and community colleges and established rules requiring deposits into and withdrawals from the fund under certain conditions.) The orange bars show the surplus or shortfall after accounting for these withdrawals. By the end of the period, the Proposition 98 budget is back in balance and the state makes a small reserve deposit. Overall, our outlook suggests that the school and community college budget generally is balanced but does not have capacity for new ongoing commitments.

In Contrast, the Remainder of the Budget Has a Budget Problem Without Universal Adjustments for Inflation. In some areas across the rest of the budget, programmatic spending is adjusted somewhat automatically for inflation—either through formulas or administrative decisions. Examples of these adjustments include actuarially determined increases in Medi‑Cal managed care rates and administrative discretion over increases to capital outlay. In other cases, spending increases are determined through legislative deliberation and are directly approved by the Legislature. Because our outlook reflects the current law and policy of the Legislature, our spending estimates only incorporate the effects of inflation on budgetary spending when there are existing policy mechanisms for doing so. This means that the actual costs to maintain the state’s service level are higher than what our outlook reflects. Consequently, our estimate of a $24 billion budget problem understates the actual budget problem in inflation‑adjusted terms. That is, assuming the Legislature wanted to maintain its current level of services, additional spending would be necessary.

Consider Inflation When Addressing the Budget Problem. As the Legislature works to address the budget problem, we suggest policymakers consider the unique impacts of inflation on each of the state’s major spending programs in conjunction with possible budget solutions. On the one hand, pausing automatic adjustments could free up resources and mitigate the need for other reductions. On the other hand, for those programs whose costs have not recently been adjusted for inflation, budget reductions would result in greater reductions in service. If the Legislature wants to provide inflation adjustments in some areas in response to higher prices, the size of the budget problem would increase, meaning corresponding reductions to other areas also would be required.

Save Reserves for a Recession

A Recession Would Result in Much More Significant Revenue Declines. While the heightened risk of a recession weighs down our revenue outlook, our estimates do not reflect a recession. Were a recession to begin within the next several months, revenue declines would be greater than shown in our revenue outlook. Based on historical experience, should a recession occur soon, revenues could be $30 billion to $50 billion below our revenue outlook in the budget window.

General Purpose Reserves Are Adequate to Cover Budget Problem, but Not if a Recession Occurs. Consistent with lower revenue estimates, the Legislature faces a budget problem of $24 billion in 2023‑24—roughly equivalent to the amount of general‑purpose reserves it could have available to allocate to General Fund programs ($23 billion). Despite this, we suggest the Legislature begin planning the 2023‑24 budget without using general purpose reserves. We say this for two reasons. First, the state will have more information about the budget condition in May. At that time, revenues could be higher or lower than our current estimates and the Legislature will need to enact the final budget in a very compressed time frame. If revenues are significantly lower, the Legislature will need both reserves and other budget solutions to address the deficit. If revenues are higher, the Legislature will not need to make as many spending reductions or revenue increases. Using the beginning months of the year to deliberate difficult budgetary choices about spending reductions or revenue increases would give the Legislature more time to weigh these decisions. Second, we would urge the Legislature to consider saving reserves for a recession when the budget problem could be twice as large as the one identified in our outlook.

In the Meantime, Recommend Legislature Identify Recent Augmentations to Pause or Delay. Recent budgets allocated significant funds to one‑time and temporary purposes, with many large augmentations planned for 2022‑23 and 2023‑24. For example, the 2021‑22 budget committed $39 billion in General Fund resources to one‑time or temporary purposes and the 2022‑23 budget committed $36 billion to similar types of activities. Early in 2023, we suggest the Legislature question the administration about the implementation and distribution of these augmentations. If augmentations have not yet been distributed, the Legislature has an opportunity to reevaluate those expenditures. Moreover, in light of the magnitude of the recent augmentations, programs may not be working as expected, capacity issues may have constrained implementation, or other unforeseen challenges may have emerged. To address the budget problem for the upcoming year, these cases might provide the Legislature with areas for pause, delay, or reassessment.

Appendix

Appendix Figure 1

General Fund Spending Through 2023‑24

(In Billions)

|

2022‑23 |

Outlook |

||

|

2023‑24 |

Change From |

||

|

Legislative and Executive |

$10.9 |

$9.2 |

‑15% |

|

Courts |

3.5 |

3.7 |

5 |

|

Business, Consumer Services, and Housing |

2.3 |

1.3 |

‑43 |

|

Transportation |

0.6 |

0.4 |

‑37 |

|

Natural Resources |

8.6 |

7.4 |

‑15 |

|

Environmental Protection |

1.5 |

2.0 |

35 |

|

Health and Human Services |

66.4 |

68.2 |

3 |

|

Corrections and Rehabilitation |

13.6 |

13.1 |

‑4 |

|

Education |

18.7 |

20.9 |

12 |

|

Labor and Workforce Development |

1.5 |

2.0 |

35 |

|

Government Operations |

4.9 |

3.6 |

‑26 |

|

General Government |

|||

|

Non‑Agency Departments |

1.8 |

3.3 |

78 |

|

Tax Relief/Local Government |

0.7 |

0.6 |

‑7 |

|

Statewide Expenditures |

7.6 |

6.7 |

‑20 |

|

Capital Outlay |

2.8 |

0.5 |

‑82 |

|

Debt Service |

5.4 |

5.6 |

4 |

|

Agency Spending Total |

$150.7 |

$148.4 |

‑2% |

|

Schools and Community Collegesa |

$78.6 |

$78.1 |

‑1% |

|

Totals |

$229.3 |

$226.5 |

‑2% |

|

aReflects General Fund component of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. |

|||

Appendix Figure 2

General Fund Spending by Agency Through 2026‑27

(In Billions)

|

Agency |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

Average |

|

Legislative and Executive |

$15.5 |

$10.9 |

$9.2 |

$5.2 |

$2.8 |

$2.4 |

‑35.8% |

|

Courts |

3.3 |

3.5 |

3.7 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

4.1 |

3.8 |

|

Business, Consumer Services, and Housing |

2.2 |

2.3 |

1.3 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

‑46.9 |

|

Transportation |

2.4 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

‑27.2 |

|

Natural Resources |

11.4 |

8.6 |

7.4 |

4.4 |

4.6 |

2.9 |

‑26.5 |

|

Environmental Protection |

4.2 |

1.5 |

2.0 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

‑56.2 |

|

Health and Human Services |

52.5 |

66.4 |

68.2 |

73.5 |

77.5 |

81.9 |

6.3 |

|

Corrections and Rehabilitation |

13.7 |

13.6 |

13.1 |

12.4 |

11.9 |

11.8 |

‑3.3 |

|

Education |

20.8 |

18.7 |

20.9 |

21.0 |

20.6 |

21.7 |

1.3 |

|

Labor and Workforce Development |

1.6 |

1.5 |

2.0 |

1.8 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

‑17.1 |

|

Government Operations |

20.1 |

4.9 |

3.6 |

3.9 |

4.0 |

3.8 |

1.4 |

|

General Government |

|||||||

|

Non‑Agency Departments |

1.8 |

1.8 |

3.3 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

‑33.2 |

|

Tax Relief/Local Government |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.1 |

|

Statewide Expenditures |

1.7 |

7.6 |

6.7 |

8.1 |

8.5 |

11.7 |

20.4 |

|

Capital Outlay |

1.6 |

2.8 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

— |

|

Debt Service |

5.2 |

5.4 |

5.6 |

5.8 |

6.0 |

5.8 |

1.2 |

|

Agency Spending Total |

$158.6 |

$150.7 |

$148.4 |

$142.9 |

$143.8 |

$149.9 |

0.3% |

|

Schools and Community Collegesa |

$83.9 |

$78.6 |

$78.1 |

$81.8 |

$87.3 |

$95.4 |

6.9% |

|

Proposition 2 Infrastructureb |

— |

— |

— |

$0.8 |

$0.5 |

$1.3 |

‑100.0% |

|

Total Forecasted Spending |

$242.5 |

$229.3 |

$226.5 |

$225.5 |

$231.6 |

$246.6 |

2.9% |

|

aReflects General Fund component of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. bIn 2022‑23, amounts are distributed across agencies. In 2023‑24, we assumed required infrastructure payments were suspended under Proposition 2 budget emergency provisions. |

|||||||

Appendix Figure 3

LAO Multiyear Revenue Outlook

(In Billions)

|

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

|

|

Personal Income Tax |

$135.9 |

$125.2 |

$122.6 |

$127.1 |

$144.1 |

$171.9 |

|

Corporation Tax |

45.5 |

37.0 |

38.6 |

40.6 |

33.8 |

25.1 |

|

Sales Tax |

32.9 |

33.3 |

33.1 |

34.1 |

35.3 |

36.5 |

|

Total “Big Three” Revenue |

($214.3) |

($195.5) |

($194.3) |

($201.8) |

($213.1) |

($233.5) |

|

Federal Cost Recovery |

$1.3 |

$6.9 |

$7.0 |

$0.5 |

$0.3 |

$0.1 |

|

Other Revenues |

6.0 |

6.2 |

6.8 |

7.1 |

7.1 |

7.2 |

|

Total Revenues |

($221.5) |

($208.7) |

($208.1) |

($209.4) |

($220.6) |

($240.8) |

|

Transfers |

$2.6 |

‑$0.4 |

$0.2 |

‑$1.2 |

‑$0.8 |

‑$1.7 |

|

Total Revenues and Transfers |

$224.1 |

$208.3 |

$208.3 |

$208.2 |

$219.7 |

$239.1 |