LAO Contact

November 16, 2022

The 2023‑24 Budget

Fiscal Outlook for Schools and

Community Colleges

Summary

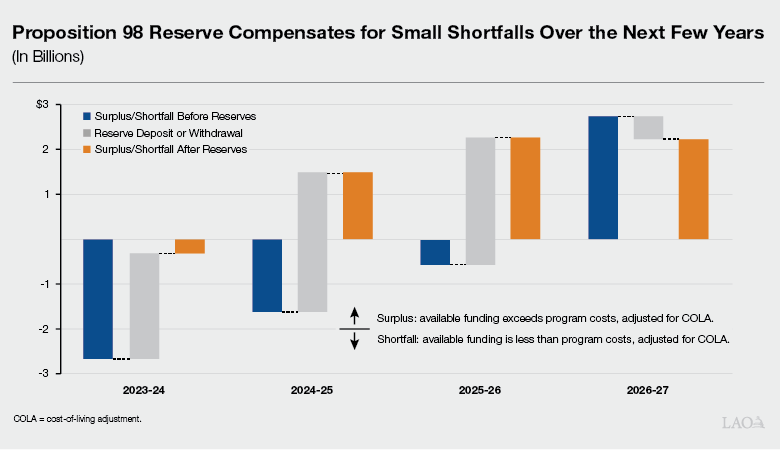

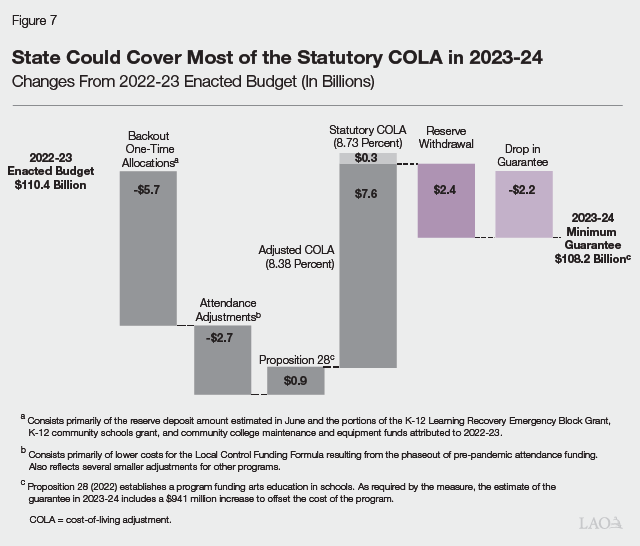

State Could Fund Increases for Existing Programs Despite Decline in Proposition 98 Guarantee. Each year, the state calculates a “minimum guarantee” for school and community college funding based upon a set of formulas established by Proposition 98 (1988). Based upon recent signs of weakness in the economy, we estimate the guarantee in 2023‑24 is $2.2 billion (2 percent) below the 2022‑23 enacted budget level. Despite this drop, $7.6 billion would be available to provide increases for school and community college programs. This funding is available due to three key adjustments—backing out one‑time costs, reducing expenditures to reflect student attendance changes, and making a required withdrawal from the Proposition 98 Reserve. In 2023‑24, the available funding could cover a cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) of up to 8.38 percent, which is slightly below our estimate of the statutory rate (8.73 percent). Over the next several years, growth in the guarantee and required reserve withdrawals would be just enough to cover the statutory COLA (see the figure below). Given this relatively precarious balance, we outline a few ways the Legislature could create a larger cushion to protect against revenue declines in the future.

Introduction

Report Provides Our Fiscal Outlook for Schools and Community Colleges. State budgeting for schools and the California Community Colleges is governed largely by Proposition 98. The measure establishes a minimum funding requirement for K‑14 education commonly known as the minimum guarantee. This report provides our estimate of the minimum guarantee for the upcoming budget cycle. The report has four parts. First, we explain the formulas that determine the guarantee. Next, we explain how our estimates of the guarantee in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 differ from the June 2022 estimates. Third, we estimate the guarantee over the 2023‑24 through 2026‑27 period under our economic forecast. Finally, we compare the funding available under the guarantee with the cost of existing educational programs and identify some issues for the Legislature to consider in the upcoming budget cycle. (The 2023‑24 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook contains an abbreviated version of this report, along with the outlook for other major programs in the state budget.)

Background

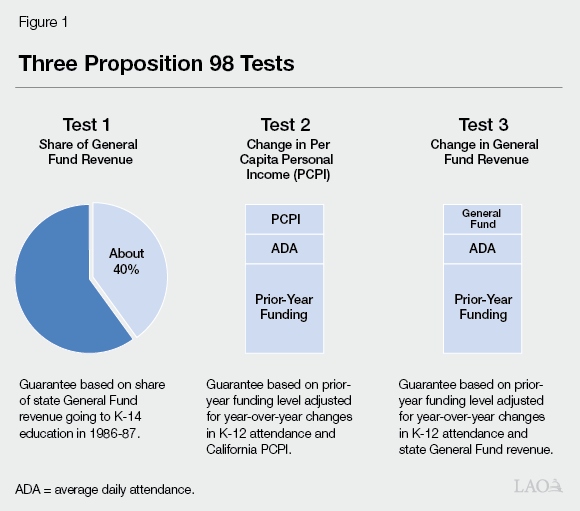

Minimum Guarantee Depends Upon Various Inputs and Formulas. The California Constitution sets forth three main tests for calculating the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. Each test takes into account certain inputs, including General Fund revenue, per capita personal income, and student attendance (Figure 1). Whereas Test 2 and Test 3 build upon the amount of funding provided the previous year, Test 1 links school funding to a minimum share of General Fund revenue. The Constitution sets forth rules for comparing the tests, with one of the tests becoming operative and used for calculating the minimum guarantee that year. Although the state can provide more funding than required, it usually funds at or near the guarantee. With a two‑thirds vote of each house of the Legislature, the state can suspend the guarantee and provide less funding than the formulas require that year. The guarantee consists of state General Fund and local property tax revenue.

Legislature Decides How to Allocate Proposition 98 Funding. Whereas Proposition 98 establishes a minimum funding level, the Legislature decides how to allocate this funding among school and community college programs. Since 2013‑14, the Legislature has allocated most funding for schools through the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). A school district’s allotment depends on its size (as measured by student attendance) and the share of its students who are low income or English learners. The Legislature allocates most community college funding through the Student Centered Funding Formula (SCFF). A college district’s allotment depends on its enrollment, share of low‑income students, and performance on certain outcome measures.

At Key Points, State Recalculates Minimum Guarantee and Certain Proposition 98 Costs. The guarantee typically changes from the level initially assumed in the enacted budget as the state updates the relevant Proposition 98 inputs. The state updates these inputs until May of the following fiscal year. The state also revises its estimates of certain school and community college costs. When student attendance changes, for example, the cost of LCFF tends to change in tandem. If the revised guarantee is above the revised cost of programs, the state makes a one‑time payment to “settle up” for the difference. If program costs exceed the guarantee, the state can reduce spending if it chooses. After updating the guarantee and making any final spending adjustments, the state finalizes its Proposition 98 calculations through an annual process called “certification.” Certification involves the publication of the underlying Proposition 98 inputs and a period of public review. The most recently certified year is 2020‑21.

School and Community College Programs Typically Receive COLA. The state calculates a statutory cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) each year using a price index published by the federal government. This index reflects changes in the cost of goods and services purchased by state and local governments across the country. Costs for employee wages and benefits are the largest factor affecting the index. Other factors include costs for fuel, utilities, supplies, equipment, and facilities. The state finalizes the statutory COLA rate based upon the data available in May prior to the start of the fiscal year. State law automatically increases LCFF by the COLA unless the guarantee—as estimated in the enacted budget—is insufficient to cover the associated costs. In these cases, the state reduces the COLA for LCFF (and other K‑12 programs) to fit within the guarantee. Though statute is silent on community college programs, the state typically aligns the COLA rate for these programs with the K‑12 rate.

Proposition 98 Reserve Deposits and Withdrawals Required Under Certain Conditions. Proposition 2 (2014) created a state reserve specifically for schools and community colleges—the Public School System Stabilization Account (Proposition 98 Reserve). The Constitution requires the state to deposit Proposition 98 funding into this reserve when the state receives high levels of capital gains revenue and the minimum guarantee is growing relatively quickly (see the box nearby). In tighter fiscal times, the Constitution requires the state to withdraw funding from the reserve. Unlike other state reserve accounts, the Proposition 98 Reserve is available only to supplement the funding schools and community colleges receive under Proposition 98.

Overview of Proposition 98 Reserve

Deposits Predicated on Two Basic Conditions. To determine whether a deposit is required, the state estimates the amount of revenue it will receive from taxes on capital gains (a relatively volatile source of General Fund revenue). Deposits are required only when the state projects capital gains revenue will exceed 8 percent of total General Fund revenue. The state also identifies which of the three tests will determine the minimum guarantee. Deposits are required only when Test 1 is operative. (Test 1 years often are associated with relatively strong growth in the guarantee.)

Required Deposit Amount Depends on Formulas. After the state determines it meets the basic conditions, it performs additional calculations to determine the size of the deposit. Generally, the size of the deposit tends to increase when revenue from capital gains is relatively high and the guarantee is growing quickly relative to inflation. More specifically, the deposit equals the lowest of the following four amounts:

- Portion of the Guarantee Attributable to Above‑Average Capital Gains. The state calculates what the Proposition 98 guarantee would have been if the state had not received any revenue from “excess” capital gains (the portion exceeding 8 percent of General Fund revenue). Deposits are capped at the difference between the actual guarantee and the hypothetical guarantee without the excess capital gains.

- Growth Relative to Prior‑Year Base Level. The state calculates how much funding schools and community colleges would receive if it adjusted the previous year’s funding level for changes in student attendance and inflation. For this calculation, the inflation factor is the higher of the statutory cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) or growth in per capita personal income. Deposits are capped at the difference between the Test 1 funding level and the prior‑year adjusted level.

- Difference Between the Test 1 and Test 2 Levels. Deposits are capped at the difference between the higher Test 1 and lower Test 2 funding levels. (The inflation factor for Test 2 is based upon per capita personal income, so in practice, this calculation tends to be less restrictive than the previous calculation.)

- Room Available Under a 10 Percent Cap. The Proposition 98 Reserve has a cap on required deposits equal to 10 percent of the funding allocated to schools and community colleges. Deposits are required only when the balance is below this level.

Withdrawals Required Under Certain Conditions. The Constitution requires the state to withdraw funds from the reserve if the guarantee is below the previous year’s funding level, as adjusted for student attendance and inflation. The amount withdrawn equals the difference between the prior‑year adjusted level and the actual guarantee, up to the full balance in the reserve. The Legislature can allocate withdrawals for any school or community college purpose. (The withdrawal may be more or less than the amount required to cover the COLA for school and community college programs because the calculation depends upon changes in the guarantee rather than changes in costs for those programs.)

Additional Withdrawals Possible if State Experiences a Budget Emergency. If the Governor declares a budget emergency (based upon a natural disaster or downturn in revenue growth), the Legislature may withdraw additional amounts from the reserve or suspend required deposits.

Proposition 98 Reserve Linked With Cap on School Districts’ Local Reserves. A state law enacted in 2014 and modified in 2017 caps school district reserves after the Proposition 98 Reserve reaches a certain threshold. Specifically, the cap applies if the funds in the Proposition 98 Reserve in the previous year exceeded 3 percent of the Proposition 98 funding allocated to schools that year. When the cap is operative, medium and large districts (those with more than 2,500 students) must limit their reserves to 10 percent of their annual expenditures. Smaller districts are exempt. The law also exempts reserves that are legally restricted to specific activities and reserves designated for specific purposes by a district’s governing board. In addition, a district can receive an exemption from its county office of education for up to two consecutive years. The cap became operative for the first time in 2022‑23.

2021‑22 and 2022‑23 Updates

Weakening Economy Affecting State Revenue Estimates. Over the past year, high levels of inflation have led the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates significantly. Recent rate hikes already have led to weakness in certain parts of the economy, particularly housing and financial markets. Many economists expect this weakness to continue over the next year and have downgraded their outlook for the economy. State tax collections in recent months also have been weaker than the state estimated in June. Estimated income tax payments for 2022 so far have been notably weaker than 2021, likely due in part to falling stock prices. Consistent with this economic environment, our estimates of the General Fund revenues that affect the Proposition 98 guarantee are $15.1 billion below the June 2022 estimates across 2021‑22 and 2022‑23.

Proposition 98 Guarantee Revised Down in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23. Compared with the estimates made in June 2022, we estimate the guarantee is down $204 million in 2021‑22 and $5.4 billion in 2022‑23 (Figure 2). These declines are due to our lower General Fund revenue estimates. Test 1 remains operative in both years, with the decrease in the General Fund portion of the guarantee equating to nearly 40 percent of the revenue drop. Our estimates of local property tax revenue, by contrast, are up slightly in both years. (When Test 1 is operative, changes in local property tax revenue directly affect the Proposition 98 guarantee. They do not offset General Fund spending.)

Figure 2

Updating Prior‑ and Current‑Year Estimates of the Minimum Guarantee

(In Millions)

|

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

||||||

|

June |

November |

Change |

June |

November |

Change |

||

|

Minimum Guarantee |

|||||||

|

General Fund |

$83,677 |

$83,306 |

‑$371 |

$82,312 |

$76,811 |

‑$5,501 |

|

|

Local property tax |

26,560 |

26,727 |

167 |

28,042 |

28,112 |

70 |

|

|

Totals |

$110,237 |

$110,033 |

‑$204 |

$110,354 |

$104,923 |

‑$5,431 |

|

|

General Fund tax revenue |

$220,109 |

$219,134 |

‑$975 |

$214,887 |

$200,767 |

‑$14,120 |

|

Program Cost Estimates Down Over the Two Years. For 2021‑22, the latest available data show that costs for LCFF are down $566 million compared with the June 2022 estimates (Figure 3). For 2022‑23, we estimate LCFF costs are down $1.4 billion. Two factors account for most of this reduction: (1) the lower costs in 2021‑22 carry forward, and (2) we make an additional downward adjustment of about 1 percent to account for the phaseout of a policy funding school districts according to the attendance they reported prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic. We also assume somewhat fewer newly eligible students enroll in transitional kindergarten (based upon enrollment trends over the past few years) and reduce our cost estimates accordingly. For all other K‑14 programs, our cost estimates are similar to the June estimates.

Figure 3

Revised Spending Is Above the Guarantee in Prior and Current Year

(In Millions)

|

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

||||||

|

June |

November |

Change |

June |

November |

Change |

||

|

Minimum Guarantee |

$110,237 |

$110,033 |

‑$204 |

$110,354 |

$104,923 |

‑$5,431 |

|

|

Funding Allocations |

|||||||

|

Local Control Funding Formulaa |

$68,249 |

$67,682 |

‑$566 |

$77,476 |

$76,055 |

‑$1,422 |

|

|

Other K‑14 programs |

38,000 |

37,995 |

‑5 |

30,654 |

30,656 |

2 |

|

|

Proposition 98 Reserve deposit |

3,988 |

4,976 |

988 |

2,224 |

14 |

‑2,210 |

|

|

Totals |

$110,237 |

$110,653 |

$416 |

$110,354 |

$106,724 |

‑$3,630 |

|

|

Spending Above Guarantee |

— |

$620 |

$620 |

— |

$1,801 |

$1,801 |

|

|

aIncludes school districts, charter schools, and county offices of education. |

|||||||

Proposition 98 Reserve Deposit up in 2021‑22 but Down in 2022‑23. The June budget plan anticipated the state would make large reserve deposits in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 due to strong revenue from capital gains. For 2021‑22, we estimate the required deposit has increased from $4 billion to $5 billion. This increase reflects our estimate that capital gains revenue was higher than the June estimate even though overall state revenue is down slightly for the year. For 2022‑23, we estimate that capital gains revenue will be significantly weaker and barely exceed the 8 percent threshold. Due to this lower estimate, the required deposit drops from $2.2 billion to $14 million. These two deposits—combined with deposits in previous years—would bring the total balance in the reserve to $8.3 billion. This reserve level represents 7.9 percent of our revised estimate of the guarantee in 2022‑23.

School Spending Would Exceed the Guarantee in Both Years. After accounting for decreases in the minimum guarantee, lower program costs, and modified reserve deposits, school spending would be $620 million above the guarantee in 2021‑22 and $1.8 billion above in 2022‑23. If the Legislature chooses to reduce spending, it could do so in ways that would not disrupt ongoing programs. For example, it could reduce certain one‑time grants the state has not yet allocated to schools or community colleges. The 2022‑23 budget also funded several grants that will be allocated in installments over the next several years. The Legislature could reduce funding for future installments and cover those costs from future budgets instead.

Multiyear Outlook

In this section, we estimate the minimum guarantee for 2023‑24 and the following three years under our economic forecast. We also examine how the Proposition 98 Reserve would change and the factors affecting costs for school and community college programs.

Economic Assumptions

Weak Economic Picture Weighs Down Revenue Estimates Over the Next Two Years. Current economic conditions point to an elevated risk of a recession starting next year. This risk weighs down our economic outlook and accounts for our estimate of flat General Fund revenues in 2023‑24 and sluggish growth in 2024‑25. Notably, however, our outlook does not specifically assume a recession occurs, which would result in more significant revenue declines. Our forecast also anticipates improvement in subsequent years, with revenue estimates reflecting normal levels of growth in 2025‑26 and 2026‑27.

The Minimum Guarantee

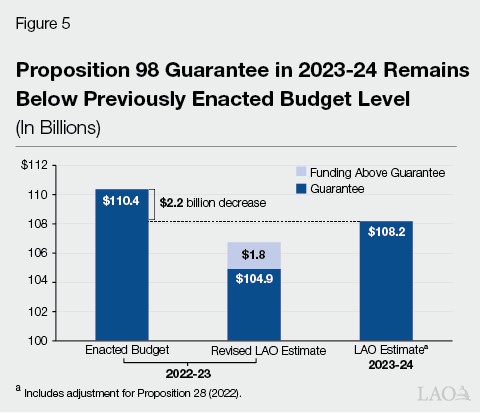

Guarantee Grows Slowly in 2023‑24 but Remains Below Previously Enacted Budget Level. The minimum guarantee under our forecast is $108.2 billion in 2023‑24 (Figure 4). Compared with our revised estimate of Proposition 98 funding in 2022‑23, the guarantee is up $1.5 billion (1.4 percent). This increase is attributable to growth in local property tax revenue and partially offset by lower General Fund spending. Despite this increase, the guarantee in 2023‑24 remains $2.2 billion below the enacted budget level for 2022‑23 (Figure 5).

Figure 4

Proposition 98 Outlook

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

|

|

Proposition 98 Funding |

|||||

|

General Funda |

$78,613b |

$78,098 |

$81,829 |

$87,258 |

$95,354 |

|

Local property tax |

28,112 |

30,077 |

31,627 |

32,573 |

33,927 |

|

Totals |

$106,724 |

$108,175 |

$113,456 |

$119,831 |

$129,281 |

|

Change From Prior Year |

|||||

|

General Fund |

‑$5,313 |

‑$515 |

$3,732 |

$5,429 |

$8,096 |

|

Percent change |

‑6.3% |

‑0.7% |

4.8% |

6.6% |

9.3% |

|

Local property tax |

$1,385 |

$1,965 |

$1,550 |

$946 |

$1,354 |

|

Percent change |

5.2% |

7.0% |

5.2% |

3.0% |

4.2% |

|

Total funding |

‑$3,929 |

$1,451 |

$5,281 |

$6,375 |

$9,450 |

|

Percent change |

‑3.6% |

1.4% |

4.9% |

5.6% |

7.9% |

|

General Fund Tax Revenuec |

$200,767 |

$200,080 |

$207,884 |

$219,187 |

$239,523 |

|

Growth Rates |

|||||

|

K‑12 average daily attendanced |

3.1% |

1.2% |

1.4% |

1.8% |

0.7% |

|

Per capita personal income (Test 2) |

7.6 |

2.0 |

1.2 |

1.8 |

3.4 |

|

Per capita General Fund (Test 3)e |

‑8.7 |

1.4 |

2.8 |

3.2 |

7.4 |

|

Proposition 98 Reserve |

|||||

|

Deposit (+) or withdrawal (‑) |

$14 |

‑$2,351 |

‑$3,110 |

‑$2,830 |

$510 |

|

Cumulative balance |

8,292 |

5,941 |

2,830 |

— |

510 |

|

a Beginning in 2023‑24, General Fund estimates include an increase for Proposition 28. b Includes $1.8 billion in funding above the minimum guarantee. c Excludes non‑tax revenues and transfers, which do not affect the calculation of the minimum guarantee. d Estimates account for the expansion of transitional kindergarten eligibility. e As set forth in the State Constitution, reflects change in per capita General Fund plus 0.5 percent. |

|||||

|

Notes: Test 1 is operative throughout the period. No maintenance factor is created or paid. |

|||||

Growth in the Guarantee Accelerates After 2023‑24. Increases in the guarantee become larger after 2023‑24, with year‑over‑year growth of 4.9 percent in 2024‑25, 5.6 percent in 2025‑26, and 7.9 percent in 2026‑27. By 2026‑27, the guarantee would be $129.3 billion, an increase of $22.6 billion (21.1 percent) compared with the revised 2022‑23 level. Of this increase, more than $16.7 billion is attributable to the General Fund portion of the guarantee and more than $5.8 billion is attributable to the local property tax portion. Test 1 is operative throughout the period, with the General Fund portion of the guarantee increasing about 40 cents for each dollar of additional revenue. Our estimates also account for two other adjustments. First, we assume the state continues to adjust the guarantee for the expansion of transitional kindergarten. This adjustment increases required General Fund spending by approximately $2.6 billion by the end of the period. Second, we account for preliminary election results indicating the voters have approved Proposition 28. This proposition increases required General Fund spending by approximately $1 billion per year beginning in 2023‑24 (as discussed later in the report).

Local Property Tax Estimates Reflect Trends in the Housing Market. Growth in property tax revenue is linked with growth in the housing market, but this growth typically lags the market by a few years. (This lag exists for three main reasons: (1) properties are not reassessed until sold, (2) new construction projects started in response to rising prices take time to complete, and (3) property tax bills are based on the assessed value of a property during the previous year.) Our forecast anticipates relatively large increases in property tax revenue of 7 percent in 2023‑24 and 5.2 percent in 2024‑25. These increases reflect the housing boom that began in the summer of 2020 and continued until early 2022. Our forecast anticipates weaker growth of 3 percent in 2025‑26 and 4.2 percent in 2026‑27. These slower increases account for cooling trends in the housing market that began in the spring of 2022.

Guarantee Is Moderately Sensitive to Changes in General Fund Revenue. General Fund revenue tends to be the most volatile input in the calculation of the Proposition 98 guarantee. For any given year, the relationship between the guarantee and General Fund revenue generally depends on which Proposition 98 test is operative and whether another test could become operative with higher or lower revenue. Under our forecast, Test 1 remains operative throughout the period, meaning the guarantee would change about 40 cents for each dollar of higher or lower General Fund revenue. In 2022‑23 and 2023‑24, Test 1 is likely to remain operative even if General Fund revenue or other inputs vary significantly from our forecast.

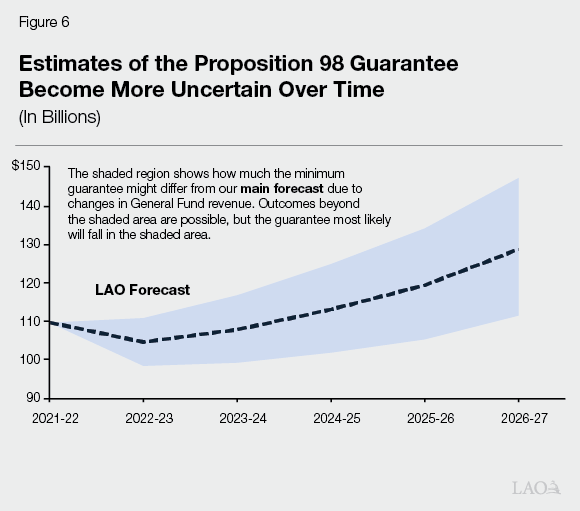

Estimates of the Guarantee Become More Uncertain Over Time. Our forecast builds upon the revenue estimates we think are most likely, but these estimates in all likelihood will be wrong to some extent. For example, our forecast assumes a relatively smooth transition to faster revenue growth over the next four years. In practice, however, revenue tends to be volatile from year to year even if it follows a general upward trajectory over time. Figure 6 shows how far the minimum guarantee could differ from our forecast based upon swings in General Fund revenue. For this analysis, we examined the historical relationship between previous revenue estimates and actual revenue collections, and then calculated the minimum guarantee under the different revenue scenarios. (Technically, the bottom of the shaded area corresponds to the 10th percentile of potential scenarios and the top corresponds to the 90th percentile.) The uncertainty in our estimates increases significantly over the outlook period. For example, the range for the guarantee in 2026‑27 is about twice as large as the range in 2023‑24.

State and School Reserves

Proposition 98 Reserve Withdrawals Begin in 2023‑24. Under our outlook, growth in the guarantee is somewhat slower than increases in student attendance and inflation for the next several years. This slower growth triggers reserve withdrawals of $2.4 billion in 2023‑24, $3.1 billion in 2024‑25, and $2.8 billion in 2025‑26. The state would begin building back the reserve balance once the guarantee begins to grow more quickly. Under our outlook assumptions, the state makes a small deposit in 2026‑27. Reserve deposits and withdrawals, however, are relatively sensitive to assumptions about revenue and inflation.

Proposition 98 Reserve Mitigates Some Volatility in the Guarantee. The reserve provides a modest cushion for school and community programs when the minimum guarantee changes. On the downside, a lower guarantee likely would lead to larger withdrawals. These withdrawals would reduce the likelihood of reductions to existing programs. This cushioning effect is relatively limited, however, because the reserve would be exhausted in 2025‑26. If the guarantee were below our estimates in 2024‑25, for example, the increase in withdrawals that year would come at the expense of withdrawals the following year. On the upside, if the guarantee were to exceed our forecast because of higher General Fund revenues, the required withdrawals likely would decrease.

Local Reserve Cap Remains Operative. Under our outlook, the school district reserve cap would remain in effect through 2024‑25. In that year, the balance in the Proposition 98 reserve would drop below 3 percent of the Proposition 98 funding allocated to schools. The cap, in turn, would become inoperative in 2025‑26. Although statewide data are not yet available, our understanding is that school district reserves currently are at relatively high levels despite the cap. County offices of education and other local experts indicate that most districts with reserves above the cap took board action to designate their reserves for specific future purposes (as the law allows), rather than spending them down immediately.

Program Costs

Very Large Statutory COLA Estimated for 2023‑24. For 2023‑24, we estimate the statutory COLA is 8.73 percent. This COLA rate—the highest since 1979‑80—reflects the significant price inflation recorded in most parts of the economy over the past year. Costs for energy and other “nondurable goods” are the fastest growing component of the index. Available data show that in the third quarter of 2022, this component increased by 25 percent compared with the same quarter in 2021. By comparison, the other components of the price index grew by an average of 6.9 percent over that period. In making our estimate of the statutory COLA, we relied upon published federal data for six of the eight quarters that determine the COLA, and our own projections for the final two quarters. The federal government will publish data for these final two quarters at the end of January and the end of April, respectively.

Statutory COLA Would Remain High Over the Next Several Years. Although most economic forecasters expect price inflation to moderate by the end of 2022‑23, evidence suggests there is a risk inflation could remain above the historical average for an extended period. Our corresponding COLA estimates are 5.3 percent in 2024‑25, 4.5 percent in 2025‑26, and 4.2 percent in 2026‑27. By comparison, the average statutory COLA over the past 20 years has been 2.8 percent.

Partial Recovery in K‑12 Attendance Assumed. Under our outlook, K‑12 student attendance grows by an average of 1.6 percent per year from 2022‑23 through 2026‑27. This growth, however, follows a steep attendance decline in 2021‑22. Data from the California Department of Education show that statewide average daily attendance totaled 5.35 million students in 2021‑22—a drop of about 550,000 students (9.3 percent) compared with the levels reported in 2019‑20 prior to the start of the COVID‑19 pandemic. (The state did not collect attendance data in 2020‑21.) Approximately three‑quarters of this drop seems attributable to a surge in absenteeism. Whereas school attendance rates averaged about 95 percent of enrollment prior to the pandemic, they dropped to around 90 percent in 2021‑22. We think much of this drop reflects the emergence of the Omicron variant of COVID‑19 in the middle of the 2021‑22 school year. Our outlook assumes districts recover about half this drop in 2022‑23, with incremental improvements in subsequent years. The remaining quarter of the attendance drop appears attributable to students who left public schools entirely, including students who left the state, enrolled in private school or homeschool, or dropped out. Our outlook does not assume any of these students return to California public schools.

Transitional Kindergarten Expansion Also Affects Statewide Attendance Over the Next Few Years. Another factor affecting statewide attendance is the expansion of transitional kindergarten. State law began expanding eligibility for this program in 2022‑23. All four‑year olds will be eligible by 2025‑26. Under our outlook, students newly eligible for this program account for slightly less than half of our estimated attendance growth over the period.

LCFF Costs Decrease as Pre‑Pandemic Attendance Funding Phases Out. For the purpose of allocating LCFF funding in 2021‑22, the state credited school districts and most charter schools with at least as much attendance as they reported in 2019‑20. This policy insulated most schools from the fiscal effects of attendance declines. Beginning in 2022‑23, the state will fund school districts according to their actual attendance in the current year, prior year, or average of the three prior years (whichever is highest). In practice, this new policy means districts’ higher pre‑pandemic attendance levels will phase‑out over the 2022‑23 through 2024‑25 period. Our outlook accounts for these changes with a $1.6 billion (2.2 percent) downward adjustment to LCFF costs in 2023‑24. This adjustment builds upon our lower revised estimate of LCFF costs in 2022‑23. (For charter schools, the state is allocating funding according to current‑year attendance only, beginning in 2022‑23.)

Outlook Assumes New Funding for Arts Education. Preliminary results from the November 8 election indicate that the voters have approved Proposition 28. This proposition creates a new ongoing program to fund arts education beginning in 2023‑24 (described in the nearby box). The measure also increases the minimum guarantee to cover the additional costs. Throughout this report, we account for Proposition 28 in our estimates of school spending and our estimates of the minimum guarantee.

Proposition 28 (2022)

Establishes New Program to Fund Arts Education. Proposition 28 establishes a program to provide additional funding for arts instruction and related activities in schools, beginning in 2023‑24. The annual amount for the program equals 1 percent of the Proposition 98 funding allocated to schools in the previous year. For 2023‑24, we estimate the program will receive an allocation of $941 million. Under our estimates of growth in K‑12 funding, this amount would grow by approximately 4 percent per year over the next several years.

Provides Rules for Allocating and Using Funds. The measure allocates 70 percent of its funding to school districts, charter schools, and county offices of education through a formula based on prior‑year enrollment of students in preschool, transitional kindergarten, kindergarten, and grade 1 through grade 12. The measure allocates the remaining 30 percent based upon the share of low‑income students enrolled in those entities in the prior year. School principals are responsible for developing expenditure plans describing how they will use their share of the funds, subject to two requirements. First, the measure requires schools with at least 500 students to use their funds primarily to hire new arts staff. Second, schools must use their funds to supplement any existing funding they already provide for their arts education programs.

Adjusts the Proposition 98 Guarantee Upward. In addition to creating a new program funded within Proposition 98, the measure adjusts the minimum guarantee upward. This adjustment occurs in two steps. In 2023‑24, the state adds the cost of the program to the minimum guarantee otherwise calculated for the year. The state then converts this amount to a percentage of General Fund revenue. Beginning in 2024‑25, the state adds this percentage to the minimum percentage of General Fund revenue allocated to schools under Test 1. Under our outlook, the $941 million cost of the program in 2023‑24 would result in an ongoing increase to the guarantee of 0.47 percent of General Fund revenue.

Legislature Can Reduce Funding if it Suspends the Guarantee. The measure allows the Legislature to reduce funding for arts education if it suspends the minimum guarantee. In this case, the percentage reduction for arts education cannot exceed the percentage reduction in overall funding for school and community college programs.

Key Considerations

In this part of the report, we highlight a few issues for the Legislature to consider as it prepares for the upcoming budget cycle. Specifically, we (1) compare the funding available under the minimum guarantee with the cost of existing school and community college programs, (2) provide context for the budget decisions the state will make in 2023‑24, and (3) identify a few issues the Legislature may want to think about when planning for the upcoming budget cycle.

The Budget Picture in 2023‑24 and Beyond

State Could Cover Existing Programs and Most of the Statutory COLA in 2023‑24. Figure 7 shows our estimate of the changes in funding and costs relative to the 2022‑23 enacted budget level. Although the minimum guarantee drops $2.2 billion, a few key adjustments free‑up significant amounts of funding. Most notably, the 2022‑23 budget allocated a significant amount of ongoing Proposition 98 funding for one‑time activities. These activities expire in 2023‑24, freeing‑up the underlying funds. We also score savings from attendance‑related changes to LCFF and account for the required reserve withdrawal. After making these adjustments, $7.6 billion in funding is available. Regarding cost increases, we estimate that covering the 8.73 percent statutory COLA would cost $7.9 billion. Consistent with current law, we assume the state reduces the COLA rate to 8.38 percent—lowering the cost by approximately $300 million—to fit within the $7.6 billion available.

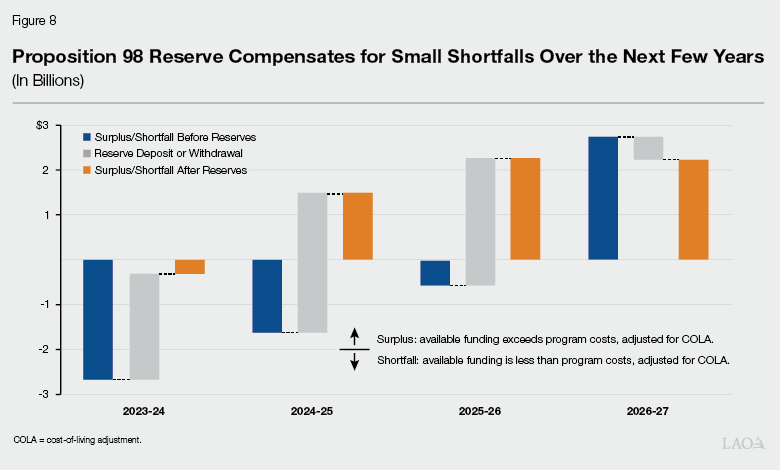

Reserve Withdrawals Cover Gap Between Guarantee and Program Costs for the Next Few Years. Figure 8 shows how the funding available for school and community college programs changes over the period under our forecast. The blue bars represent the amount by which the Proposition 98 guarantee is above or below the cost of covering existing programs as adjusted by the statutory COLA. Negative bars indicate a “shortfall” (the guarantee is insufficient to cover these costs) and positive bars indicate a “surplus” (the guarantee is more than sufficient). The gray bars account for required withdrawals and deposits from the Proposition 98 Reserve. The orange bars represent the surplus or shortfall after accounting for the reserve. As the figure shows, a small shortfall exists each year through 2025‑26, but reserve withdrawals provide additional funding that reduces the shortfall in 2023‑24 and more than offset the shortfalls in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26.

Budget Picture Stabilizes by the End of the Period, Assuming No New Ongoing Commitments. Under our forecast, the gap between the minimum guarantee and program costs shrinks over the period. In 2026‑27, the guarantee is above the cost of existing programs and the state begins making reserve deposits rather than withdrawals. The picture could improve sooner if the economy grows more quickly than our forecast or the statutory COLA rate is smaller. Alternatively, it might improve after 2026‑27 if the state experiences a recession during the forecast period. In making these estimates, we also assume the state makes no new ongoing commitments.

The Education Budget in Context

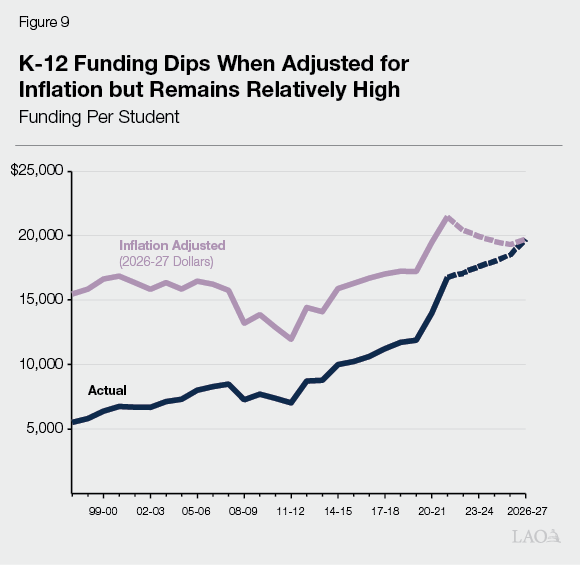

Tighter Outlook Follows Two Years of Extraordinary Growth. Although our outlook estimates a drop in the guarantee in 2022‑23 and slow growth in 2023‑24, these changes build upon two previous years of historic growth. Between 2019‑20 and 2021‑22, the minimum guarantee grew $31.3 billion (39.5 percent)—the fastest increase over any two‑year period since the passage of Proposition 98 in 1988. The drop in 2022‑23 erodes only a small portion of this gain. By historical standards, the school funding picture remains strong. Figure 9 illustrates this point by comparing our estimate of K‑12 funding per student under our outlook with funding levels over the previous 25 years. After accounting for the effects of inflation and changes in student attendance, school funding would dip in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24 but remain relatively high over the remainder of the period.

Multiyear Block Grants Provide Further Support to Districts. The June 2022 budget plan funded two large block grants to address the effects of the COVID‑19 pandemic on schools and community colleges. These grants are intended to support district activities over the next several years. For schools, the state provided $7.9 billion for the Learning Recovery Emergency Block Grant (averaging about $1,500 per student). Schools can use their funds broadly to support academic learning recovery, staff and student social and emotional well‑being, and other costs attributable to the pandemic. For community colleges, the state provided $650 million (about $730 per student) to fund student support, reengagement strategies, professional development, technology, equipment, and other specified activities. Although both block grants are provided on a one‑time basis, they represent an additional source of funding districts can use to supplement other funding over the next several years.

Previous Budget Actions Significantly Improve the Budget Picture in 2023‑24. Our estimate of the funding available in 2023‑24 highlights the importance of preparing for economic downturns during stronger fiscal times. The budget adopted by the Legislature in June contained two major components that improved budget resiliency. Specifically, the budget (1) set aside some ongoing funds for one‑time activities and (2) made the Proposition 98 Reserve deposits required by Proposition 2. If the state had not set aside any ongoing funds and lacked the Proposition 98 Reserve, the budget picture in 2023‑24 would look much different. Under that alternative scenario, we estimate that the available Proposition 98 funding would have been at least $8.3 billion—rather than about $300 million—below the level necessary to cover existing programs and the statutory COLA. Facing such a scenario, the state might have needed to eliminate the 2023‑24 COLA or fund a much smaller COLA and take other actions to reduce spending.

Rest of the State Budget Faces Large Problem. The rest of the state budget—consisting of the programs not funded through Proposition 98—is in a difficult position under our outlook. Specifically, the rest of the budget faces a $25 billion problem in 2023‑24. This shortfall represents the difference between available resources and the cost of currently authorized programs and services. The problem is due primarily to reductions in General Fund revenue, partially offset by (1) lower required spending to meet the Proposition 98 guarantee and (2) lower required deposits into the state’s general‑purpose reserve. Moreover, the rest of the budget faces an ongoing deficit over the next several years. Even with relatively strong revenue growth in 2025‑26 and 2026‑27, the resources available in those years are less than the estimated cost of current programs and services. Given these issues, the state would have difficulty funding school and community college programs beyond the amounts required to meet the guarantee.

State Appropriations Limit Is Not a Significant Issue This Year… Proposition 4 (1979) places constraints on how the state can spend tax revenues that exceed a certain limit. Specifically, if the state collects revenue in excess of the limit, the Constitution allows the Legislature to respond by lowering tax revenues, increasing spending on activities excluded from the limit, or splitting the excess revenues equally between taxpayer refunds and one‑time payments to schools and community colleges. Due primarily to our lower General Fund revenues, we estimate the state is below the limit in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24.

…But Would Affect State Budgeting in the Future. Assuming General Fund revenues follow the trajectory in our forecast, the state appropriations limit would begin to affect state budgeting in 2025‑26. The main reason is that our estimates of General Fund revenue grow faster than the limit itself over the next several years. Our Proposition 98 outlook does not make any explicit adjustment for the appropriations limit, in part because the state must fund the minimum guarantee even if the limit requires reductions to other programs in the state budget. The state, however, could respond to future excess revenues in ways that would affect school funding. For example, it could reduce General Fund tax revenue, which also would lower the guarantee. Alternatively, it could split excess revenues between refunds and one‑time payments, which would provide schools and community colleges with additional funding on top of the minimum guarantee. Estimates of the state appropriations limit also are subject to significant uncertainty beyond the budget year.

Planning for the Upcoming Year

Economic Uncertainty Abounds as Legislature Prepares for Upcoming Budget Cycle. The current economic environment poses a substantial risk to state revenues. In the past, economic conditions similar to the conditions we have observed over the past several months have typically resulted in subsequent revenue declines. On the other hand, we do not think a recession next year is inevitable. Even if a recession does occur, its exact timing and severity are uncertain. Our outlook takes a middle approach—assuming economic weakness but not a recession. For 2023‑24, this uncertainty means the Proposition 98 guarantee could be billions of dollars above or below our current estimates. Although the state will have a better sense of revenues and the guarantee by June when it adopts the budget, the economic picture beyond 2023‑24 remains murky.

Building a Larger Budget Cushion Would Mitigate Future Downside Risk. Our outlook makes spending estimates for school and community college programs based upon current laws and policies. Two important assumptions are embedded in this forecasting approach: (1) the state maintains existing programs at their current levels except for formula‑driven adjustments, and (2) the state applies all available Proposition 98 funding (including reserve withdrawals) toward covering the statutory COLA. Using this approach to set ongoing spending levels in 2023‑24, however, would leave the Proposition 98 budget precariously balanced over the coming years. For example, our estimate of the guarantee in 2024‑25 is just large enough to cover existing programs and the statutory COLA after accounting for a reserve withdrawal. In approximately half of all the potential economic scenarios that could unfold that year, the guarantee ends up below our estimate. Although the Proposition 98 Reserve might cushion a minor decrease, a larger drop would pose risks to ongoing programs. To build up somewhat more protection against such downside risks, the Legislature could consider some adjustments next year to create a larger budget cushion. Specifically, it could reduce certain ongoing expenditures and increase one‑time spending. Below, we outline a few options for reducing ongoing expenditures.

Consider Reductions to Expanded Learning Opportunities Program (ELOP). The state created ELOP in the 2021‑22 budget to fund academic and enrichment activities for K‑12 students outside of normal school hours. As part of the 2022‑23 budget, the state increased ongoing funding for the program from $1 billion to $4 billion. The program allocates funding to districts based on their attendance in the elementary grades and share of low‑income students and English learners. Although statewide data are not available, initial feedback from districts suggests not all low‑income students and English learners are interested in the program. We think the state could improve the program and reduce costs by allocating funding based on actual participation instead of districtwide attendance. The state also could reduce ELOP allocations by accounting for other state and federal funds districts receive for before and after school programs. To achieve additional savings on a one‑time basis, the state could further require districts to spend all their ELOP funding from 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 before they receive funding in 2023‑24. Any of these actions could achieve savings without requiring districts to serve fewer students.

Consider Reductions to Community College Programs That Are Under Capacity or Lower Priority. Over the past few years, the state has provided some funding that may not be earned by colleges or may be a lower legislative priority. The 2021‑22 budget, for example, provided a $24 million base augmentation to SCFF for enrollment growth. Based on preliminary data, only about $1 million of this funding will be earned by districts. The Legislature could revert any unearned funds—and reduce systemwide base funding by a like amount—once final data is reported by the Chancellor’s Office in spring 2023. Similarly, this spring the Legislature could identify other community college programs that may be under capacity, such as the California Apprenticeship Initiative or other grant programs the Legislature has authorized in recent years. The Legislature also may want to target for reductions certain programs that may be a lower priority given the students served. For example, the 2022‑23 budget provided $25 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund to expand eligibility for the California College Promise. This program allows colleges to waive enrollment fees for returning students enrolled full time who do not have financial need given their higher income level.

Consider Funding Smaller COLA. Another option would involve reducing the COLA rate below the 8.38 percent increase we estimate the state could fund in 2023‑24. One reason the state might consider this option is that the surge in energy prices appears to be responsible for a notable portion (likely at least 2 percentage points) of the high COLA rate. Although district energy costs are likely up too, these costs typically account for a small share of district budgets. The Legislature could consider funding a COLA that is below the statutory rate but still large enough to allow schools and community colleges to address their cost pressures and local priorities. We estimate that each 1 percent reduction in the COLA rate equates to approximately $910 million in lower ongoing spending.

Legislature Could Advance Its Priorities Next Year Through Oversight. Over the past two years, the Legislature has allocated Proposition 98 funding to more than 50 new school and community college activities. Some of the largest allocations have involved learning loss recovery, community schools, the teaching workforce, infrastructure, and community college financial aid and student support services. The Legislature could use the upcoming budget cycle to conduct oversight of these activities. In particular, the Legislature might want to examine: (1) whether these activities are having their intended effects on students and programs, (2) how these activities fit with broader goals (such as reducing historical funding disparities among districts, improving student achievement, and closing achievement gaps), and (3) any challenges districts face implementing these activities. By conducting oversight and exploring changes in these areas, the Legislature could continue to advance its priorities despite the tighter budget picture we anticipate next year.