LAO Contact

December 13, 2022

Redesigning California’s

Adult Education Funding Model

Summary

State Began Restructuring Adult Education System Almost a Decade Ago. The primary purpose of adult education is to serve as a first point of entry for Californians seeking to acquire basic skills and potentially move into more advanced instruction or the workforce. School districts (through their adult schools) and community colleges are the state’s main providers of adult education. Due to longstanding concerns with a lack of coordination among providers, the state began restructuring its adult education system in 2013‑14. Though the new adult education delivery system based on regional consortia has benefits, we believe the way the state funds adult education is fundamentally flawed and at odds with the state’s program goals.

Various Drawbacks of Current Funding Model, Recommend New Approach. The figure below identifies the main shortcomings of the existing funding model and our recommended new funding model. The new model we present is better aligned with the state’s existing program objectives of enhanced regional coordination and improved student outcomes. Moreover, it could be implemented such that it costs, on net, no more or less than the existing adult education funding model. To help adult schools and community colleges adjust to the new funding model, we recommend the state phase in implementation over several years. A multiyear transition would give providers and consortia time to improve their programs and adjust their budgets. We believe now is an opportune time to undertake the transition, as providers overall currently are receiving substantial funding beyond their program costs, likely making the transition more manageable for them.

Redesigning the State’s Adult Education Funding Model

|

Drawback of Existing Funding Model |

Recommended Funding Model at Full Implementation |

|

|

Adult school funding is not linked to student attendance, and adult schools have widely different per‑student funding rates without justification. |

→ |

Adult schools are funded based on student attendance, with a uniform base per‑student rate that is the same as the CCC noncredit funding rate. |

|

No CAEP or CCC noncredit funding is linked to provider performance (though federal adult education funds and CCC credit funds are linked to performance). |

→ |

Adult schools and community colleges earn a portion of their CAEP and noncredit funding, respectively, based on their student outcomes. |

|

Adult schools charge fees, even though most adult students are low income and community colleges serving a similar population of students either do not charge such fees or waive them. |

→ |

Adult schools do not charge fees. (The new, uniform base funding rate would cover all expected program costs.) |

|

No CAEP funding is allocated directly to consortia for regional coordination and successful student transitions to collegiate courses. |

→ |

Consortia receive a minimum fixed CAEP amount, plus an amount based on size. Consortia also earn CAEP funds based on their student outcomes (specifically, how well they transition adult education students from precollegiate to collegiate courses). |

|

Adult school funding is not adjusted annually for changes in student demand (though CCC credit and noncredit funding is adjusted accordingly). Neither adult school nor CCC noncredit funding is adjusted based on performance. |

→ |

Adult school funding is adjusted annually for changes in student demand. Both adult school and CCC noncredit funding are adjusted annually for changes in student outcomes. |

|

CAEP = California Adult Education Program. |

||

Introduction

Adult Education Serves Several Purposes. Adult education is intended to provide adults with the precollegiate knowledge and skills they need to participate in civic life and the workforce. Adult education serves state residents who have educational objectives such as learning to speak English; passing the oral and written exams for U.S. citizenship; earning a high school diploma; receiving job training; and obtaining the prerequisite proficiency in reading, writing, and mathematics to enter collegiate coursework. Adult education students come from many backgrounds, though the vast majority are from lower‑income households, often speaking languages other than English at home. The most typical student is female, Hispanic, low income, and between 25 and 45 years old. Adult schools (primarily through school districts) and community colleges are the main providers of adult education in California.

Brief Examines Funding Model for Adult Education. Historically, adult schools and community colleges generally had little coordination—neither coordinating their precollegiate course offerings nor their pathways for students from adult schools to collegiate courses at community colleges. In 2013‑14, the state restructured its adult education system with the key objectives of fostering greater communication and coordination and producing better student outcomes. Under the new structure, providers must join a local adult education consortium as a condition of receiving state funds. As California’s restructured adult education system approaches its tenth year, this brief reexamines the state funding model and assesses how effectively it promotes state objectives. This brief has three main parts. The first part provides background on adult education funding. The second part assesses the current funding model, and the third part offers recommendations to improve the state funding model.

Background

The state has funded school districts and community colleges in notably different ways for adult education. In this section, we first describe the state funding rules for school districts’ adult schools, then turn to the funding rules for community colleges. Next, we discuss how certain regional coordination activities are funded. At the end of this section, we discuss federal funding for adult education. (In our 2012 report Restructuring Adult Education in California, we provide more detail on the history of adult education in California and the major coordination challenges and other problems with the old system.)

Adult Schools

Prior to 2008‑09, the State Funded Adult Schools on a Per‑Student Basis. In 2007‑08, about one‑third of school districts in the state operated adult schools. Geographically, the 276 adult schools operating that year canvased most areas of the state. (Adult schools typically are located at their own sites—separate from, but sometimes adjacent to, other schools in a district.) Funding for adult schools was based on average daily attendance (ADA), with one ADA equivalent to 525 instructional hours. In 2007‑08, districts received $2,645 in state funding per ADA (about $3,900 per ADA in today’s dollars). Adult schools received this funding rate regardless of the specific courses they offered, with basic English and math, English as a second language (ESL), career technical education (CTE), and citizenship courses commonly offered.

During This Period, Adult Schools Had Enrollment Caps. Prior to 2008‑09, school district adult education programs had funding caps on the total number of ADA they were paid for each year. Per statute (initially adopted in 1979‑80), each district’s ADA cap was increased by 2.5 percent annually. If a school district failed to reach its cap for two consecutive years, that district’s cap would be reduced and the amount of enrollment monies that went unused would be redirected to other districts serving students in excess of their funding caps. This redistributive approach was intended to help align school district allocations with statewide demand for adult education services. Schools with enrollment over their caps generally tended to reduce their enrollment gradually down to their caps if funding was not forthcoming. Schools tended to view supporting over‑cap enrollment as otherwise unsustainable over the long term.

During Great Recession, Certain State Actions Had Significant Implications for Adult School Funding. In 2007‑08, the state provided a total of $754 million (Proposition 98 General Fund) to school districts (and a few county offices of education) for their adult education programs. Beginning in 2008‑09, the state reduced funding for school districts due to declining revenues. That fiscal year, the state implemented a 15 percent across‑the‑board cut to most school district categorical programs, including adult education. This cut deepened to 20 percent in 2009‑10 and remained at that reduced level in 2010‑11 and 2011‑12. In a corresponding action reflecting a major departure from earlier budgetary practices, the state allowed school districts to use their adult education funding for any education purpose. The amount of adult education funding that school districts redirected for K‑12 purposes varied considerably—from a few districts redirecting no funds to other districts redirecting all their funds. By 2012‑13, school districts collectively were spending an estimated $337 million on adult education—slightly more than half of the $635 million nominally provided in Proposition 98 adult education categorical funds that year.

State Embarked on Major Adult Education Restructuring in 2013‑14. Due to a desire by the Legislature to preserve local spending on adult education but longstanding concerns with a lack of coordination among providers, the 2013‑14 budget package mapped out a new state strategy for funding and operating adult education. Specifically, the budget provided one‑time funds to school districts and community colleges for the purpose of forming consortia and developing regional delivery plans. In a related action, the 2013‑14 budget package eliminated school districts’ adult education categorical program and consolidated all associated annual funding ($635 million Proposition 98 General Fund) into a new school district Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). The budget package, however, contained a requirement for school districts to maintain at least their 2012‑13 level of state spending on adult education in 2013‑14 and 2014‑15. Finally, the 2013‑14 budget package included intent language for the Legislature to provide funding to the regional consortia beginning in 2015‑16 “to expand and improve the provision of adult education.”

State Created New Dedicated Funding Stream for Adult Education in 2015‑16. After giving providers two planning years, the 2015‑16 budget created the Adult Education Block Grant—later renamed the California Adult Education Program (CAEP). The state initially provided $500 million (ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund) for the revamped program. This funding was on top of LCFF funding, effectively resulting in school districts being able to repurpose all their previous adult education funding for K‑12 purposes. In 2015‑16, 72 consortia (later 71 consortia) participated in the adult education program. Under the program, each consortium is tasked with serving adults according to its regional delivery plan. Each consortium includes at least one community college district, along with neighboring adult schools, with consortia having an average of about six members. (Only community colleges, county offices of education, school districts, and joint powers authorities—such as regional occupational centers administered by multiple school districts—may be consortia members. Some consortia, however, subcontract with partners such as libraries and community‑based organizations to provide adult education services.)

New Adult Education Program Has Two‑Part Funding Formula. Of the initial $500 million appropriation, $337 million was allocated directly to adult schools in the newly formed consortia based on their level of state spending on adult education in 2012‑13. The remaining $163 million was distributed to consortia based on a calculation of regional need. (This post describes the state allocation method in more detail.) Consortia were given wide discretion both in how to use these needs‑based funds and how to allocate them among their members. Consortia commonly used a portion of their needs‑based funds for coordination activities, with the remainder passed through to consortia members for direct services. Under the new program, all CAEP funds must be spent on adult education and cannot be redirected for K‑12 or other non‑CAEP purposes.

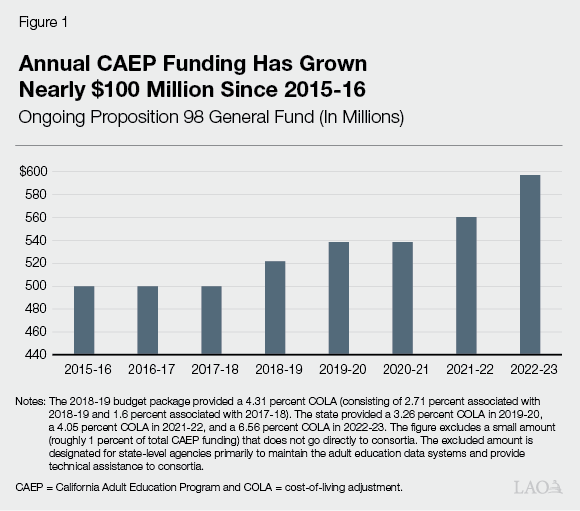

State Has Increased CAEP Funding Over Time but Has Not Made Attendance Adjustments. Figure 1 shows that annual CAEP funding increased from $500 million in 2015‑16 to almost $600 million in 2022‑23. Since 2015‑16, each consortia member generally has received its original CAEP amount plus certain cost‑of‑living adjustments (COLA). (Statute generally requires each CAEP member to receive at least the same level of funding as it did in the prior year.) Though the state has provided COLAs to the program over this period, it has not provided funding for enrollment growth or other attendance‑related adjustments.

Under CAEP, Adult Schools Are No Longer Funded on Per‑Student Basis. Currently, about 300 adult schools receive about $525 million in CAEP funding. (This amount equates to 88 percent of all CAEP funding, with community colleges receiving the remainder.) Adult schools use the bulk of their CAEP funding for direct instruction. Unlike in the past, however, the state has no set per‑student funding rate. Each adult school determines for itself how many students to serve with its CAEP allocation and how much to spend per student. In 2021‑22, adult schools served a total of about 50,000 ADA, equating to an average of about $10,000 in CAEP funding per ADA (though rates varied widely across schools). This per‑student funding average is considerably higher than pre‑pandemic levels. In 2018‑19, adult school enrollment was much higher (about 80,000 ADA), with average CAEP funding per ADA at about $5,800.

School Districts May Charge Fees for Some Adult Education Courses. Statute permits adult schools to supplement their CAEP funding by charging fees for CTE courses. (Schools may not charge fees for any other adult education courses, such as ESL and high school diploma courses.) Generally, adult education students do not qualify for state aid when taking these CTE courses, though in some instances they may qualify for federal aid. Fees for CTE courses vary among adult schools and type of program, with fees ranging from a few hundred dollars to several thousands of dollars. For example, Hacienda La Puente Adult School (Los Angeles County) charges $2,980 for a medical assistant program (which takes about a year to complete) compared to $600 at Visalia Adult School (Tulare County). Sweetwater Adult School (San Diego County) currently assesses no charge for the program. Adults schools reported collecting about $20 million statewide in fee revenue in 2021‑22.

Community Colleges

Funding for Adult Education at the Community Colleges Depends on Type of Courses Offered. Besides adult schools, adults in California can access precollegiate instruction at the California Community Colleges (CCC). Historically, most community colleges have offered at least some precollegiate instruction, though some colleges have operated very large adult education programs (accounting for more than 20 percent of all their instruction). The state provides community colleges with apportionment funding (ongoing Proposition 98 funding) to support their precollegiate (and collegiate) instruction. The funding method used and amount provided for adult education instruction depends on whether a community college classifies a particular precollegiate course as “noncredit” or “credit.”

Community College Noncredit Instruction Is Based Solely on Student Enrollment. In 2022‑23, the published funding rate for most types of noncredit courses (including basic English and math, ESL, and CTE) is about $6,800 per full‑time equivalent (FTE) student. The published funding rate for the remaining noncredit courses (including citizenship courses) is about $4,100. (We discuss the difference between “published” and “effective” funding rates later in this section.) For both types of noncredit instruction, apportionment funding generally is calculated based solely on student attendance. (The nearby box provides more detail on the various ways adult education providers calculate student attendance.)

Calculating Adult Education Attendance

Historically, Adult Education Providers Calculated Attendance in One of Three Ways. Funding for adult schools historically has been based on average daily attendance (ADA), with one ADA equivalent to 525 instructional hours. Similarly, funding for community colleges’ noncredit programs has been based on students’ daily course attendance, known as “positive attendance.” One full‑time equivalent student count in a community college noncredit program also equates to 525 hours of course instruction. Prior to the pandemic, calculating attendance in adult schools and community college noncredit programs was straightforward because the vast majority of instruction was in person and the attendance calculations basically relied on counting the number of in‑person course hours. Counting student attendance for the purpose of funding community colleges’ credit programs has been different. Attendance in credit courses generally has been calculated based on the number of students enrolled at a given point in the academic term (commonly known as the census date), which is typically the third or fourth week of the term.

Recent Changes in Instructional Modality Have Led to Additional Ways to Calculate Attendance. As a result of the pandemic, many adult schools and noncredit programs shifted their classes from an in‑person to online modality. Attendance in online classes that were synchronous (meaning the teacher and student communicate with each other in real time) continued to be calculated based on contact hours. In cases in which the teacher and student interact asynchronously (that is, when a student can choose when to access lessons and send communications to the teacher), adult education providers needed to use a different set of rules in place of contact hours. Adult schools and noncredit providers ended up using different approaches. Specifically, based on teachers’ determinations, adult schools are assigning a fixed number of class hours for each assignment or lesson mastered by students. In contrast, community college noncredit programs are using a census approach, which is based on the average number of students enrolled in an asynchronous online class at two points during the term. (Credit instruction already was using a census approach to calculate student enrollment in both synchronous and asynchronous online courses. Over the past few years, these programs have made no changes to their attendance calculations.)

Community College Credit Instruction Is Funded Based on Three Factors. Historically, state funding for both noncredit and credit courses was based solely on student enrollment. In 2018‑19, the state changed how it allocated funding for credit courses—creating the Student Centered Funding Formula (SCFF). Under SCFF, funding for most types of credit instruction, including precollegiate credit courses such as ESL, is now based only partly on student enrollment. In 2022‑23, colleges receive a base rate of about $4,800 per FTE student enrolled in credit courses. On top of this base rate, colleges receive additional funding for each student enrolled who is low income and additional funding based on performance, as measured by graduation rates and various other student outcomes. The overall credit per‑student rate—comprised of all three allocation components—is similar to the rate provided for most types of noncredit instruction (about $6,800 in 2022‑23). (In a 2017 report, we provide more information on the noncredit funding rate, how it has compared over time to the credit funding rate, and the rationale for equalizing the two rates.)

Noncredit Courses Account for Larger Share of Precollegiate Instruction Than Credit Courses. In 2021‑22, the state provided about $330 million (Proposition 98 apportionment funding) for about 50,000 noncredit FTE students served at the community colleges. (Though adult schools also served about 50,000 ADA that year, the counts are not entirely comparable, for reasons discussed in the nearby box.) By comparison, we estimate the state provided approximately $315 million (Proposition 98 apportionment funding) for about 40,000 precollegiate credit FTE students in 2021‑22. (We had to derive these precollegiate credit estimates because community colleges do not classify their credit CTE courses as precollegiate or collegiate.)

Two Important Caveats When Comparing Attendance Estimates

Different Course Offerings. One reason why adult school average daily attendance (ADA) counts are not entirely comparable with community colleges’ noncredit full‑time equivalent (FTE) student counts is that statute has different rules for the courses each of these providers is allowed to offer. Statute allows community colleges to offer certain noncredit courses, including home economics and enrichment courses designed for older adults. In contrast, statute prohibits adult schools from offering these types of courses using their California Adult Education Program funds. As a result, the community college noncredit FTE student counts include students who are not included in the adult school ADA count. For this reason, one might view the noncredit FTE student count as somewhat overstated relative to the adult school ADA count.

Different Attendance Accounting. Another reason the counts are not entirely comparable is due to the differences in how adult schools and community college noncredit programs are calculating attendance in their asynchronous online classes. Though these methodological differences likely are having an impact on student counts, we are unaware of any research that has been done on which method is yielding higher/lower student counts.

Colleges’ Effective Funding Rates Are Higher Than Published Rates. In 2021‑22, community colleges’ effective funding rates per student were notably higher than the state’s published rates that year. This is because college enrollment—in both noncredit and credit programs—has dropped significantly since 2018‑19, but the state has allowed colleges to use their pre‑pandemic enrollment levels for funding purposes. (This funding protection currently is set to expire at the end of 2022‑23.) As a result of these funding rules, we estimate colleges in 2021‑22 effectively received $6,600 per noncredit student (for most noncredit courses), compared to the published noncredit rate of $5,900 that year. The difference in rates was even greater for credit courses, with colleges’ effectively receiving $7,900 per credit student, compared to an average total credit rate of about $6,000 (reflecting the combined published base, supplemental, and student outcome rates).

Community Colleges Also Receive Some CAEP Funding. In addition to apportionment funding, most community colleges have received some of the needs‑based CAEP funding since the program was created in 2015‑16. Currently, 67 community college districts collectively receive about $70 million (12 percent) of CAEP funding. (Five community college districts have decided with fellow consortium members not to receive any CAEP funds.) Community colleges typically use their CAEP funding to provide additional support for their noncredit students and, depending on the consortium, for CAEP coordination activities. (The next section provides more detail on these coordination activities.) Additional student support commonly includes tutoring and career counseling. Some community colleges also use CAEP funds—supplemented with apportionments funds—to cover instruction‑related costs of certain higher‑cost noncredit classes. For example, a district may use CAEP funds to cover the costs of a supplemental ESL instructor embedded in a CTE course aimed at English learners.

Community Colleges Generate Little Fee Revenue From Precollegiate Courses. Unlike adult schools, statute prohibits community colleges from charging any enrollment fees for noncredit instruction. For credit instruction, statute establishes a community college enrollment fee ($46 per unit in 2022‑23). The credit enrollment fee is waived for students who are financially needy or enrolled in a minimum of 12 credit units per term. Because most students enrolled in precollegiate credit courses are likely low income and receiving fee waivers, little associated fee revenue likely is generated from these courses systemwide.

Consortium‑Level Activities

Some CAEP Activities Occur at the Consortium Level. Whereas adult schools and community colleges provide adult education instruction, certain CAEP activities occur at the consortium level. For example, a consortium commonly has a director to organize meetings and lead the regional planning process. A consortium might also have other staff such as data analysts and “transition specialists” who help students transition from precollegiate programs to collegiate coursework or the workforce. Other common consortium‑level activities include marketing to prospective students and coordinated professional development (such as joint CCC‑adult school workshops). Statute limits the amount that can be spent on administrative activities to 5 percent of a consortium’s total CAEP allocation, but no spending cap is placed on programmatic activities. Within these parameters, each consortium chooses how much to spend in these areas.

Funding for Consortium‑Level CAEP Activities Can Be in Various Members’ Budgets. Most often, funding for these types of consortium activities is part of a community college member’s CAEP budget. In a smaller number of cases, funding for consortium‑level services is part of a school district’s or county office of education’s CAEP budget. In other cases, funding for consortium‑level activities is part of each member’s budget, with each member annually contributing an agreed‑upon amount toward these activities.

Federal Funds

Federal Funds Supplement Many Providers’ Budgets. Beyond CAEP funding, fee revenue, and apportionment funding, some adult education providers also receive federal funding. In 2021‑22, California received $108 million in federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) Title II funds. Of the $108 million, the California Department of Education (CDE) used $12 million for administration of the grant and certain statewide activities. The remainder was distributed directly to adult education providers. Pursuant to CDE policy, adult education providers must apply for WIOA Title II funds. Successful applicants are those that use data to inform their instructional practices and have qualified teachers, among other factors. Historically, CDE has approved most applications. Grant recipients tend to use WIOA Title II funds primarily to hire additional teachers to expand their adult education course offerings and additional staff to expand their student support services. About half of adult schools and one in four community college districts receive WIOA Title II funds.

State Allocates Federal Adult Education Funds to Providers Based on Performance. Although the federal government does not require it, CDE allocates WIOA Title II funds to grant recipients using a pay‑for‑performance approach. Under this approach, specified student outcomes earn a provider performance point. For example, adult education providers earn points each time one of their students attains a high school diploma or when one of their students improves literacy pre‑ and post‑test scores by a set amount. Figure 2 lists the performance measures CDE uses. CDE then takes the state’s annual WIOA grant and divides available funding by the total points earned across all grant recipients in a given year to determine a per‑point rate. Grants are determined by multiplying the per‑point rate by the number of points earned by a particular provider. This approach is meant to create a strong incentive for providers to deliver services that improve academic performance, program completion rates, and student transitions to the workforce.

Figure 2

CDE Uses Several Performance Measures to

Allocate Federal WIOA Title II Funds

|

|

|

|

|

|

CDE = California Department of Education and WIOA = Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act. |

Assessment

In this section, we provide our assessment of the current funding model for adult education. Overall, we think the consortium‑based delivery approach has merit, but the state’s approach to funding adult education is flawed.

Some Positive Aspects of Consortia. After decades of little coordination between adult schools and community colleges, the state’s move to a consortium‑based approach has improved communication and collaboration among many providers. In developing regional plans, for example, a number of consortia have identified unmet needs of certain groups—such as adults with disabilities—and sought to expand programs to meet that need. Consortium members also are more likely to discuss ahead of time proposals to start a new adult education program, thereby potentially reducing duplication of effort. In a few cases, providers within a consortium plan out which course sections each will offer in a given year. Consortia’s transition specialists also are focused on promoting the state objectives of greater coordination and improved student success. Moreover, a number of consortia have added local workforce development boards as partners. Under these partnerships, the workforce boards (through their federally funded America’s Job Centers) refer dislocated or other unemployed workers to an adult school or community college for training. Adult education providers, in turn, refer their students to the centers to find jobs. Often, strategies and relationships such as these emerged from the regional planning processes required by the state.

CAEP Funding Model Is Disconnected From Student Demand. Though the consortium‑based delivery approach has positive aspects, the CAEP funding model has several significant flaws. One flaw is that the CAEP funding model is based primarily on school districts’ adult education spending levels from a decade ago. Those spending levels, in turn, were based on decisions made by school districts during the Great Recession about how much adult education funding to shift to K‑12 programs. As a result, funding for certain adult schools is significantly below “pre‑flex” levels and does not necessary align with student demand. For example, Sacramento Unified School District received $14 million in 2007‑08 but repurposed the vast majority of that funding in subsequent years when the state allowed funding flexibility. As a result, even with the additional funding it received as part of the needs‑based CAEP appropriation in 2015‑16, the school currently is receiving only about $1.4 million in CAEP funds. At this lower funding level, the district had to reduce the number of adult education sites it operates, refer adults seeking to enroll in a high school diploma program to a neighboring district (Elk Grove), and reduce the number of ESL classes it offers. In 2021‑22, its ADA was less than 400—down substantially from the approximately 5,400 ADA it served in 2007‑08. A related disadvantage of this historically based funding model is that adult schools with increased student demand—such as those in areas of the state experiencing an influx of refugees and other immigrants—do not have an opportunity to earn additional enrollment funds from the state. Instead, adult schools wanting to accommodate this increased enrollment demand must either spend less per student or ask fellow consortium members (some of which also might be facing greater enrollment demand) to relinquish some of their own funds.

Funding Model Lacks Fiscal Incentive to Provide Access. Under current CAEP rules, adult schools receive a set amount of funding regardless of how many students they serve. This funding model does not create a strong incentive for adult schools to enroll students. Though data are limited, they suggest a small share of eligible adults currently are enrolled in adult education courses. For example, more than 6 million adults in California are estimated to lack English proficiency, whereas fewer than 140,000 adults enrolled in ESL courses in 2021‑22. Similarly, more than 4 million adults in California are estimated to lack a high school diploma or its equivalent, whereas fewer than 115,000 adults were enrolled in secondary education courses leading to such a diploma in 2021‑22. Based on our conversations with various consortium members, although some adult schools strive to connect with potential students, others are less responsive. For example, some consortium members have commented on the lengthy amount of time some fellow consortium members take to open new classes or start new adult education programs. This lack of a strong fiscal incentive to provide access also manifests itself in some schools opening adult education programs to new student enrollment only a few times during the year or eschewing other innovative strategies to attract and accommodate students.

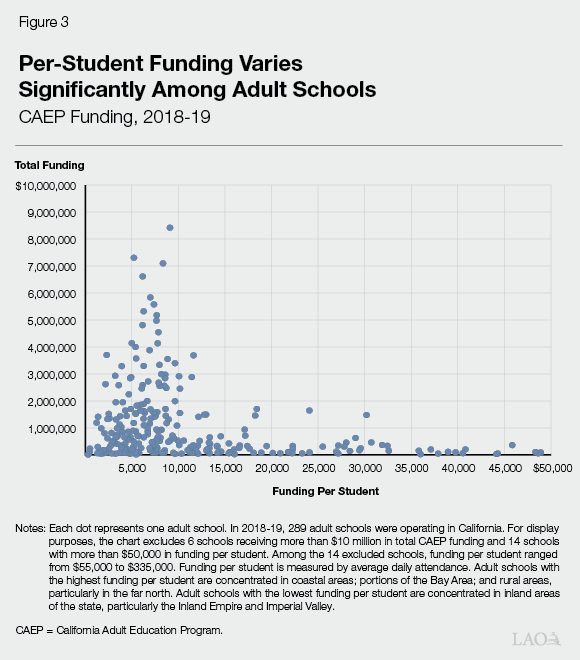

Funding Model Results in Uneven Program Quality. Figure 3 shows that funding per student at adult schools varies considerably, even among adult schools receiving similar levels of total CAEP funding. Funding differences among adult schools, as well as between adult schools and community colleges, can result in uneven quality of programs for adults across the state. For example, two schools with a similar level of CAEP funding can serve a notably different number of students. The school choosing to serve fewer students could have full‑time teachers and many support staff (such as counselors) available to students. In contrast, the school choosing to serve more students could be relying almost exclusively on part‑time teachers and have very limited student support services. We saw examples of these program quality differences on our visits to several adult schools.

Differences in Fee Policies Make Matters Worse. The rationale for different CTE fee policies among adult schools and community colleges is not particularly compelling. The rationale for different fee policies appears to be that community colleges can claim apportionment funds to cover their costs, as well as supplement their programs with CAEP funds, whereas adult schools receive state funds only through CAEP. Moreover, some adult schools have much lower per‑student CAEP funding amounts than other schools—amounts that might be insufficient to cover their associated costs. By allowing adult schools to collect fees for CTE courses, some of these schools therefore might be able to maintain courses they otherwise would have to cancel due to a lack of state funding. Fees, however, could be an impediment for some students and contribute further to both unequal access and considerable variation in program quality.

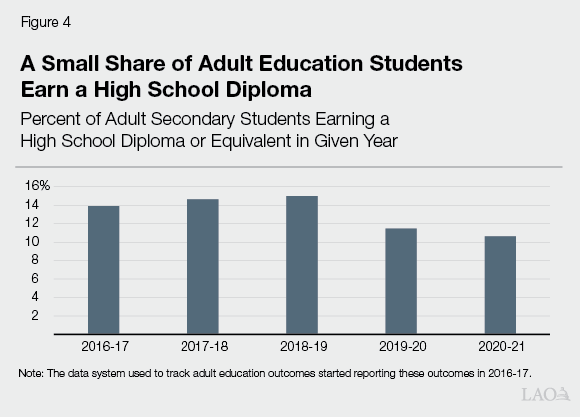

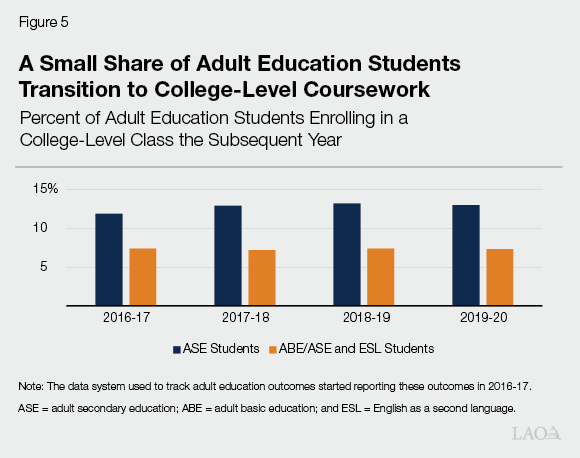

Weak Incentives Are in Place to Improve Student Outcomes. Though the restructuring of adult education that the state began in 2013‑14 was intended to improve student outcomes, providers and consortia generally have been making little, if any, progress on key performance measures. This was the case even before the onset of the pandemic. As Figure 4 shows, from 2016‑17 through 2018‑19, the share of adult students earning a high school diploma or its equivalent increased only 1.1 percentage point (before dropping by more than 4 percentage points over the next two years). As Figure 5 shows, the share of adult students transitioning into college‑level coursework has fared about the same. One reason why student outcomes might not have improved is that CAEP and CCC noncredit funding are not linked to performance. Without performance‑based funding or some other form of state accountability for student outcomes, consortia members lack strong incentives to improve their results.

No Funding Is Provided Specifically for Consortium‑Level Activities. Despite seeking to improve coordination among providers and streamline student pathways between adult schools and community colleges, the state provides no CAEP funding specifically for consortium‑level activities. Instead, when needs‑based funding was provided in 2015‑16, consortium members had to decide how much to allocate to their own budgets for direct student services and how much to use for consortium‑level activities. Though data is very limited, budgeted amounts for consortium‑level activities appear to vary widely across the state, with some consortia spending notably larger shares of their CAEP budgets on these activities. Those consortia spending more on these activities generally appear to be offering their members greater programmatic benefits (such as coordinated student outreach and professional development).

Recommendations

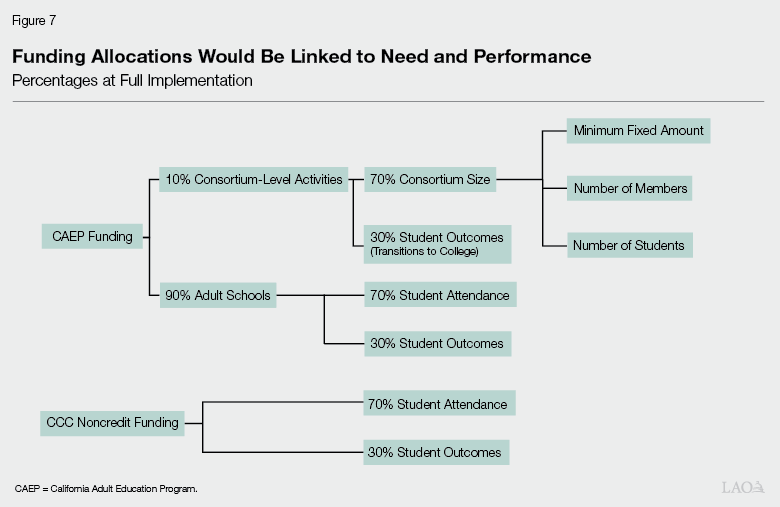

Given the notable shortcomings with the existing adult education funding model, we believe a full redesign is warranted. In this section, we recommend creating a new model consisting of several components. The new model we present is better aligned with the state’s existing program objectives of enhanced regional coordination and improved student outcomes. Moreover, it could be implemented such that it costs no more or less than the existing adult education funding model. Given the multiple components of the new model and the associated redistributive implications, the state could phase it in over several years. Figure 6 summarizes our recommendations and Figure 7 shows how funding would be allocated under the new model. We describe the components of the new model throughout the remainder of this section, ending with an illustrative phase‑in plan.

Figure 6

New Adult Education Funding Model

|

Summary of Recommendations |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

WIOA = Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act; CTE = career technical education; and CAEP = California Adult Education Program |

Begin by Setting Uniform Base Per‑Student Rate for Adult Education Providers. We think the most important first step is to set a uniform funding rate per student. We recommend the state provide the same base per‑student funding rate for adult schools and community college noncredit courses. The state might start with the existing CCC noncredit rate of $6,788 per student. This rate is about the same as the overall CCC credit rate and about the same as the average per‑student rate that adult schools received in 2018‑19 after adjusting for inflation since that time. Providing a uniform base per‑student funding rate and funding providers based on attendance would better connect funding with student demand, incentivize and reward providing student access, and create more consistent program services across California. A uniform base rate also would send clearer signals about the basic quality of programs that the state expects providers to offer. This, in turn, could help in establishing a consistent corresponding fee policy (discussed later in this section), treating providers and students more similarly across the state.

Build Performance Component for Providers Into New Funding Model. A potential downside to a funding model that relies solely on a uniform per‑student rate is that it could create an incentive for providers to “hold on” to their students (such as ESL students) longer than necessary to continue generating funding—even if that is not best for students. To create a stronger financial incentive for adult education providers to serve students well and collaborate in ways that accelerate student success, we recommend adding a performance‑based component to both CAEP and CCC noncredit apportionment funding. This performance‑based funding would be in addition to the base uniform funding per student that providers would receive. To keep the model cost neutral, the state could reduce base funding gradually over the phase‑in period, building up performance funding in tandem. The performance component we envision is somewhat akin to the performance‑based components that already exist for CCC credit apportionment funding and federal WIOA Title II funding. Whereas the CCC credit apportionment formula allocates 10 percent of funds based upon performance and WIOA Title II funds are allocated entirely based upon performance, we recommend 30 percent of the CAEP and CCC noncredit funding be linked to performance. Though a different amount could be justified, we think 30 percent is high enough to promote improvement in student outcomes (which have not shown much improvement) but not so high that providers’ funding levels fluctuate over time too notably or unpredictably.

Tailor Performance Component to Key Adult Education Outcomes. As a starting point in creating this new performance‑based funding component, we recommend using the performance measures that CDE already uses to allocate federal WIOA Title II funds to providers. All adult schools—even those that do not participate in the WIOA Title II program—are required to collect data on these performance measures. In addition, a majority of community colleges currently collect these data either because they are required to as WIOA Title II recipients or volunteer to do so as part of CAEP. (These data from adult schools and community colleges are publicly reported in LaunchBoard, a state‑funded adult education data system.) To the WIOA Title II measures, we recommend adding one performance measure for providers—the number of CTE certificates earned by adult education students. To allocate performance funding, the state could set a dollar value to each performance point and adjust by COLA each year. This is similar to how the state adjusts student success funding under SCFF, but varies from how CDE administers WIOA, in which the point value can fluctuate year to year depending on the number of points earned and the total size of the WIOA grant. The approach we recommend would give providers more funding stability from year to year.

Eliminate Fees at Adult Schools. Given the vast majority of adult education students are low income, we recommend the Legislature make fee policies for adult schools consistent with the zero‑fee policy for CCC noncredit instruction. We recognize that requiring students to pay a fee can be associated with positive behavioral tendencies, such as making students more deliberate in their selection of courses. Given that students do incur costs to attend school—including transportation, child care, and the opportunity cost of not being able to work while they attend classes—we believe adult learners already have sufficient “skin in the game.” Though some adult schools would lose fee revenue under this recommendation, the new uniform base rate per student described above would be designed to fully cover providers’ expected program costs. Moreover, the state would not necessarily face higher overall program costs. This is because current state funding rates per student are elevated due to recent enrollment drops not being accompanied by state funding reductions. (In response, some providers have revisited their fee policies—suspending or lowering them in some cases.)

Allocate Some CAEP Funding Directly for Consortium‑Level Activities. In addition to an allocation to providers based on student attendance and certain performance outcomes, we recommend the new funding model allocate a portion of total CAEP funding (such as 10 percent) directly to consortia. Consortia would have flexibility in how they spent these funds for administrative and programmatic purposes, with possible activities including regional planning, conducting student outreach, building partnerships with workforce organizations, and providing student transition services. Under our recommendation, consortium members could choose to augment funding using their own CAEP allotments if they desired to undertake more of these types of activities.

Link Funding for Consortium‑Level Activities to Three Main Components. Specifically, we recommend the state provide each CAEP consortium with a fixed amount to cover a minimum level of staff for planning and coordination purposes. On top of this fixed allotment, we recommend the state provide additional funding to consortia based on the number of members and students served. Consortia with larger memberships and programs would receive larger allotments, in recognition that coordination and joint programmatic activities (such as marketing and professional development) tend to require more time and be costlier the larger the consortium. Lastly, we recommend allocating some amount of consortium‑level funding (such as 30 percent) based on outcomes. Specifically, we recommend consortia be evaluated based upon how successful they are at transitioning students into college‑level instruction. Providing some performance‑based funding at the consortium level would create a stronger incentive for adult schools and community colleges to work together to identify strategies that improve pathways for students. To implement this recommendation in a cost‑neutral manner, the state could consider re‑designating CAEP funding from community colleges. A large share of these funds is already being used for similar purposes.

Annually Adjust CAEP Funding Based on Key Cost Drivers. We recommend a new CAEP funding model include the opportunity for adult schools and consortia to earn growth funding if they are facing heightened enrollment demand. Specifically, we recommend the state budget for overall CAEP enrollment growth based on underlying demographic and economic changes, such as changes in the adult population and unemployment rate. Currently, the state considers similar factors when providing enrollment growth funding for CCC apportionments, including CCC noncredit instruction. The state also could adjust adult education funding annually based upon the change in the number of performance points that providers and consortia have earned in recent years (such as by using a lagged three‑year rolling average).

Phase In New Funding Model Over Several Years. Figure 8 provides an illustration of how the state might phase‑in the components of the new model. To help adult schools and community colleges adjust to the new funding model, we recommend the state phase in implementation of the new model over a multiyear period, for example, five years. A multiyear phase in would give providers and consortia time to adopt new strategies designed to increase funding (such as to improve student outcomes and recover enrollment lost during the pandemic) and adjust their budgets. The state could begin with small changes the first year, giving providers time to re‑size their programs. The state gradually could align funding with enrollment over the five‑year period. About halfway through the phase‑in, the state could begin implementing the new performance components of the model, both at the provider and consortium level.

Figure 8

State Could Phase In a Redesigned Adult Education Funding Model

Illustrative Phase‑In Plan

|

Component of New Model |

Phase In of New Model |

||||

|

Year 1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

Year 4 |

Year 5 |

|

|

Uniform base rates for providers |

Have providers begin internally adjusting their budgets and programs in anticipation of rate changes. |

Gradually adjust provider rates such that by year 5 all adult schools are funded at the same base per‑student rate as the noncredit funding rate, with their funding tied to actual enrollment. |

|||

|

Provider performance funding |

Adopt new performance measures and calculate associated funding rates. |

Give providers an opportunity to improve their performance in these areas. |

Gradually lower program funding that is linked to base per‑student rate while raising amount linked to performance (for example, having performance linked to 10 percent of program funds in year 3, 20 percent in year 4, and 30 percent in year 5). |

||

|

Adult school fees |

Have providers begin internally adjusting their budgets and programs in anticipation of new fee policy. |

Prohibit adult schools from charging enrollment fees. |

|||

|

Funding formula for consortia |

Adopt new three‑part consortium‑level funding formula (base amount as well as supplemental rates linked to consortium size and performance). |

Give consortia an opportunity to improve their regional coordination and student transitions. |

Gradually replace CAEP funds going to community colleges with funding based on new formula. Gradually increase share linked to performance (for example, 10 percent in year 3, 20 percent in year 4, and 30 percent in year 5). |

||

|

Annual funding adjustments |

Moving forward, adjust funding for providers and consortia based on changes in students served and performance points earned. |

||||

|

CAEP = California Adult Education Program. |

|||||

Impact on Providers Would Vary. Like nearly all funding model redesigns, the new adult education funding model would impact some adult education providers and consortia more than others. For adult schools, the specific impact on any particular provider would depend upon how much it currently was spending per student, the extent to which it could increase enrollment over the transition period, and its performance over time in serving students. The specific impact on community colleges would depend mostly on their performance in serving students (at both the college and consortium level).

Now Is Opportune Time to Implement New Model. Given enrollment levels across adult education providers are depressed and per‑student funding rates are substantially elevated given pandemic‑related funding protections, providers overall currently are receiving substantial funding beyond their program costs. This is evident by the amount of CAEP funding adult schools have been carrying over. Unspent CAEP program funds grew from $83 million at the end of 2018‑19 to $162 million at the end of 2021‑22. Given these factors, we believe now is an opportune time to implement the new model, as the impact likely will be less disruptive than it would be during a period in which enrollment levels were high and program reserves were small.