LAO Contact

January 6, 2023

The California State Bar

Assessment of Proposed Disciplinary

Case Processing Standards

Executive Summary

On October 28, 2022, the State Bar provided our office with its proposed (1) caseload processing standards for resolving attorney discipline cases within its Office of Chief Trial Counsel (OCTC), (2) establishment of a backlog goal and metrics to measure such a goal, and (3) staffing requirements needed to achieve the new standards. As required by Chapter 723 of 2021 (SB 211, Umberg), this report presents our assessment of the State Bar’s proposal.

State Bar Licenses Attorneys and Regulates Their Professional Conduct. The State Bar functions as the administrative arm of the California Supreme Court for the purpose of admitting individuals to practice law in California and regulating the professional conduct of attorneys by adopting and enforcing rules of professional conduct. As of December 2022, there were more than 286,000 members of the State Bar—of which about 196,000 (or 69 percent) have elected to actively practice law in California.

State Bar Administers Own Disciplinary Process. The State Bar administers its own disciplinary system primarily through OCTC and the State Bar Court (SBC). OCTC receives, investigates, and prosecutes cases against attorneys, while the SBC adjudicates these cases. Generally, the disciplinary process consists of four stages: (1) Intake, in which complaints are received; (2) Investigation, in which cases are investigated; (3) Charging, in which OCTC determines whether to formally file charges; and (4) Hearing, in which OCTC prosecutes cases in the SBC. OCTC currently prioritizes the processing of cases based on potential risk to members of the public. State law currently requires the State Bar to complete the first three stages of the disciplinary process—specifically for OCTC to dismiss a complaint, admonish an attorney, or file formal charges against an attorney—within 180 days after receipt of a written complaint for “noncomplex” cases and 365 days for “complex” cases.

State Bar Proposal. In its report, the State Bar proposes the following changes related to its attorney disciplinary process:

- New Case Processing Standards. The State Bar proposes that disciplinary cases be prioritized based on both risk to members of the public as well as case complexity. It also proposes average case processing time standards across six case categories based on when a case is closed, the stage at which it is closed, and the case risk/complexity (such as high‑risk, complex cases closed in the Investigation Stage).

- Establishment of a Backlog Goal and Metrics. The State Bar proposes a backlog goal of 10 percent or fewer cases as well as a backlog standard for each of the new case processing standards.

- Defers Comprehensive Staffing Analysis. The State Bar defers a comprehensive staffing analysis to 2023 in order to incorporate legislative direction on the proposed case processing standards as well as various OCTC operational changes that are currently in progress or are being considered. However, the State Bar preliminarily calculates that an additional 78 to 119 additional OCTC staff could be needed, which would cost between $10.6 million to $16.3 million.

Analyst’s Review of State Bar Proposal. We reviewed the State Bar’s proposal and identified key questions for legislative consideration on the overall proposal as well as its three key components.

- Overarching Comments—Consider Whether Changes for Additional Oversight Are Warranted. The State Bar’s proposal assumes that the existing disciplinary process is generally reasonable. However, the Legislature will want to consider whether it believes changes are warranted. Additionally, we note that the lack of legislative approval of the State Bar budget can make oversight difficult. Accordingly, the Legislature will want to consider what level of oversight it wants to exercise over State Bar processes and funding.

- New Case Processing Standards—Partially Reasonable, but Raises Several Concerns. We found it reasonable to include both risk and complexity when prioritizing cases. However, we identified several concerns related to the proposed standards. For example, we find it unclear whether the aggressive time lines reflected in the standards are reasonable. In light of these concerns, we raised five key questions for legislative consideration. For example, the Legislature will want to consider how aggressive they believe case processing standards should be.

- Establishment of Backlog Goal and Metrics—Partially Reasonable, but Also Raises Several Concerns. We found that alternative definitions of backlog could also be reasonable and identified several concerns with the State Bar’s proposal. For example, the State Bar’s proposed backlog metrics measure closed, rather than pending, workload. Based on our review, we identified three key questions for legislative consideration. For example, the Legislature will want to consider how backlog should be defined and calculated.

- Staffing Analysis—Makes Sense to Delay Analysis. We found that it was reasonable that the State Bar report only provides a preliminary estimate of staffing and resource needs. However, we are concerned with the State Bar’s plan to conduct a staffing analysis in 2023 given that the full impact of various operational changes will likely not be known at that time. Based on our review, we identified two key questions for legislative consideration. For example, the Legislature will want to consider when would be the most appropriate time for the State Bar to conduct the staffing analysis.

Introduction

Chapter 723 of 2021 (SB 211, Umberg) required the State Bar to propose (1) case processing standards for resolving attorney discipline cases within the Office of Chief Trial Counsel (OCTC) in a timely, effective, and efficient manner while allowing for small backlogs of attorney discipline cases and (2) the OCTC staffing requirements needed to achieve these standards. Senate Bill 211 also required that the State Bar’s analysis and recommendations be submitted to our office for review. Finally, SB 211 required we report to the Senate and Assembly Judiciary Committees on our review.

On October 28, 2022, the State Bar provided our office with its proposed case processing standards. This report presents our required assessment of these standards. Specifically, in this report, we first provide background on the State Bar and the attorney discipline system. We then summarize the key provisions of the State Bar’s proposal. Finally, we provide our assessment of the overall proposal, as well as the individual provisions, and identify key questions for legislative consideration.

Background

What Is the State Bar?

Oversees the Practice of Law in California. The California Constitution requires attorneys to be members of the State Bar to practice law in the state. The California Supreme Court has the power to regulate the practice of law in the state—including establishing criteria for admission to the State Bar and disbarment. The State Bar functions as the administrative arm of the Supreme Court for the purpose of admitting individuals to practice law in California and regulating the professional conduct of attorneys by adopting and enforcing rules of professional conduct. The State Bar is established by the Constitution as a public corporation. The State Bar currently is governed by a 13‑member board of trustees. As of December 2022, there were more than 286,000 members of the State Bar—of which about 196,000 (or 69 percent) have elected to actively practice law in California.

How Are State Bar Activities Funded?

Fees Are Assessed to Support Activities. State Bar activities are generally funded by various fees paid by attorneys—most notably the annual mandatory licensing fee. These fees are deposited into the State Bar’s General Fund—its main operating account which can be used for various purposes—as well as various special funds that support specific programs administered by the State Bar. For example, the fee collected for the Client Security Fund is used to reimburse clients who suffer financial losses due to attorney misconduct. Other State Bar revenue sources include grants and lease revenue.

The State Bar’s adopted 2022 calendar year budget estimates total revenues of $244 million and total expenditures of $257 million, with the difference requiring the use of funds from its reserve. In its 2022 budget, the State Bar estimates that its General Fund will receive $91 million (or 37 percent) of total revenues. Remaining revenues will go to various special funds. Of this amount, $84 million (or 92 percent) will come from a portion of the mandatory annual license fee. As shown in Figure 1, the 2023 maximum annual fee that can be charged is $515 for active attorneys and $182.40 for inactive attorneys. The majority of this amount—$415 of the fee paid by active attorneys and $117.40 of the fee paid by inactive attorneys associated with licensing and discipline—is deposited into the State Bar’s General Fund. The General Fund, however, is used to support a major portion of State Bar operations. For example, the State Bar estimates total 2022 personnel costs of $95 million—of which $81 million (or 86 percent) will be supported from the General Fund.

Figure 1

Summary of 2023 Maximum Annual License Fee

|

Active |

Inactive |

|

|

Mandatory Fees |

||

|

Licensing |

$390.00 |

$92.40 |

|

Discipline |

25.00 |

25.00 |

|

Client Security Fund |

40.00 |

10.00 |

|

Lawyer Assistance Program |

10.00 |

5.00 |

|

Subtotals |

($465.00) |

($132.40) |

|

Voluntary Feesa |

||

|

Legal Services Trust Fund |

$45.00 |

$45.00 |

|

Lobbying activities |

5.00 |

5.00 |

|

Subtotals |

($50.00) |

($50.00) |

|

Total Fees That May Be Charged |

$515.00 |

$182.40 |

|

aAttorneys are able to choose whether to pay these fees. |

||

Legislature Establishes Annual Fees, but Does Not Approve State Bar’s Annual Budget. Each year, the judiciary policy committees of the Legislature set the license fees charged to members of the State Bar for the coming year through the annual “fee bill.” When a fee bill is not enacted, the California Supreme Court has authority to set the license fees. Under current law, if either the Legislature or the Supreme Court does not approve these fees for a given year, the State Bar does not have authority to levy fees on its members in that year. In contrast, the State Bar’s budget is approved by the board and does not require approval by the Legislature. As such, the annual budget of the State Bar is not reviewed by legislative budget committees through the annual state budget process. This is different than the process for nearly all other state licensing entities that regulate other professions, which generally involves an entity’s fee structure (such as fee levels) and proposed expenditure levels being approved by the Legislature and the Governor. Moreover, these other entities generally need to provide written budgetary justification for any substantive changes to existing budget levels (such as to cover increased costs of operations or to support new activities) as well as explain why additional revenues in the form of higher fees are needed to support these costs. Annual legislative oversight of both revenues and expenditures allows the Legislature to conduct ongoing oversight of an entity’s operations as well as to ensure that any approved funding is used accountably and consistently with legislative expectations.

How Does the State Bar Oversee Attorney Conduct?

Attorneys Required to Meet Various Professional and Ethical Requirements. California—similar to other states—has various professional and ethical requirements for attorneys practicing law in the state. Examples of such requirements include: providing competent service to existing and former clients, prohibiting false or misleading communication or advertising of legal services, keeping certain information provided by clients confidential, and ensuring appropriate use of client monies held in trust accounts. These requirements are outlined in state law, California Rules of Court, rules approved by the board, and the California Rules of Professional Conduct. Claims of attorney misconduct—specifically, complaints that such professional and ethical requirements were violated—are adjudicated by the State Bar.

State Bar Administers Own Disciplinary Process. The State Bar administers its own disciplinary system primarily through OCTC and the State Bar Court (SBC). OCTC—consisting of teams of attorneys, investigators, and other legal administrative staff—receives, investigates, and prosecutes cases against attorneys—which we describe in more detail below. The SBC—consisting of judges, attorneys, and other legal and administrative staff—adjudicates these cases. (We note that the Supreme Court reviews and issues the final order when SBC recommends the suspension or disbarment of an attorney.) Various other departments within the State Bar—such as the Probation Department that supervises attorneys who are required to comply with certain conditions set by the SBC or the Supreme Court—also support the disciplinary system.

Disciplinary Process Consists of Four Stages. The disciplinary system consists of four stages. We describe each of these stages in greater detail below.

- First Stage: Intake. The Intake Stage (also known as the Inquiry Stage) generally begins with a written complaint filed with OCTC that an attorney has violated a professional or ethical requirement. The State Bar also may initiate its own investigations against attorneys. After an initial review and limited information‑gathering on the complaint, OCTC will either close the complaint (for example, notifying the complainant that no action is to be taken or issuing a warning letter to the accused attorney) or refer the case for investigation. The State Bar reports that about 63 percent of complaints are closed at this stage and require an average of 42 days to close.

- Second Stage: Investigation. The Investigation Stage consists of OCTC investigators, under the guidance and supervision of OCTC attorneys, analyzing the case through interviews, subpoenas, document review, and other activities to determine whether there is clear and convincing evidence that attorney misconduct has occurred or if the case should be closed. Cases are closed in various ways, such as notifying the complainant and the accused attorney of the reasons why no action is to be taken or reaching an agreement in lieu of discipline for low‑level violations. The State Bar reports that about 33 percent of complaints are closed at the Investigation Stage and require an average of 230 days to close.

- Third Stage: Charging. The Charging Stage (also known as the Pre‑Filing Stage) begins with OCTC evaluating the evidence collected in the Investigation Stage as well as internally documenting potential charges and appropriate levels of discipline to seek. If the case is closed, the complainant and the accused attorney receive letters explaining why no action is to be taken. If OCTC determines there is sufficient evidence to file charges against an accused attorney, OCTC will notify the attorney in writing of its intent to file formal charges with SBC. Before the charges can be filed, the accused attorney is entitled to request a confidential meeting(s)—also known as an Early Neutral Evaluation Conference (ENEC)—in which the attorney and OCTC appear before an SBC hearing judge to evaluate the facts and charges and potentially try to resolve the case by negotiating a settlement. Such meetings are mandatory if requested by accused attorneys. If the accused attorney does not request an ENEC, informal negotiations may still occur between the accused attorney and OCTC. The State Bar reports that about 4 percent of complaints processed by OCTC were closed at the Charging Stage, reached negotiated settlement, or resulted in the filing of charges. Such actions required an average of 449 days to achieve.

- Hearing Stage. When disciplinary charges are formally filed with the SBC, the Hearing Stage begins. OCTC is responsible for filing the changes and prosecuting the cases. SBC adjudicates the case and imposes the appropriate level of discipline—which can include case dismissal, public or private reprovals, probation, suspension, and disbarment. (The SBC also reviews settlement terms reached at the end of the Charging Stage.) For cases where the proposed discipline involves the suspension or disbarment of the attorney, the California Supreme Court reviews the SBC’s findings and recommended disciplinary action and issues a final order.

How Much Does the Disciplinary System Cost to Operate?

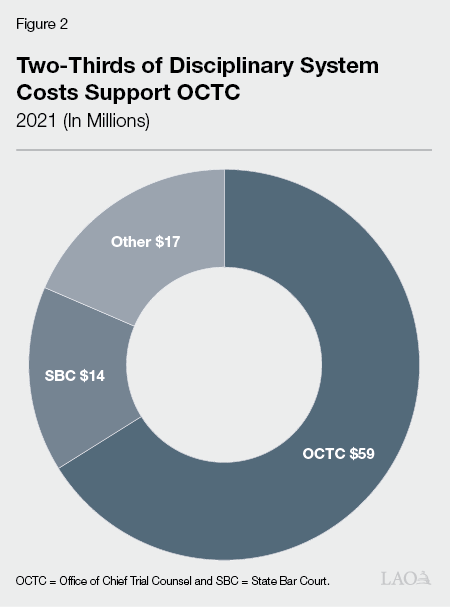

System Costs About $89 Million. The State Bar reports it cost $89 million (or 45 percent of total expenditures) to operate its entire disciplinary system in 2021—most of which came from its General Fund. As shown in Figure 2, $59 million (or 66 percent) of this total amount supported about 279 positions in OCTC and $14 million (or 15 percent) supported about 42 positions in SBC. The remaining 19 percent supported various other departments involved with the disciplinary system.

How Much Disciplinary Workload Is Processed Annually?

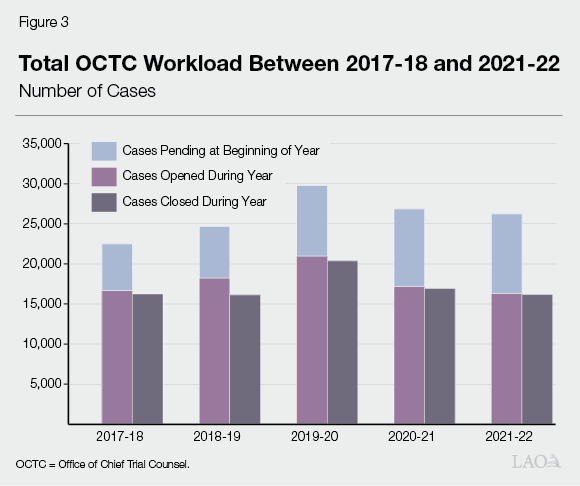

OCTC Workload. Total OCTC workload steadily increased from 2017‑18 through 2019‑20. The total number of cases opened peaked in 2019‑20 with 20,979 cases. The cases opened decreased in the subsequent years. In 2021‑22, 16,355 cases were opened—a decrease of 4,624 cases (or 22 percent) from 2019‑20. These opened cases are added to OCTC workload that remained unresolved from prior years. As shown in Figure 3, the number of cases closed have not matched the number of cases opened annually. This generally resulted in an increase in the number of the cases pending at the end of the year. This increase has generally slowed between 2019‑20 (9,668 pending cases) and 2021‑22 (10,054 cases).

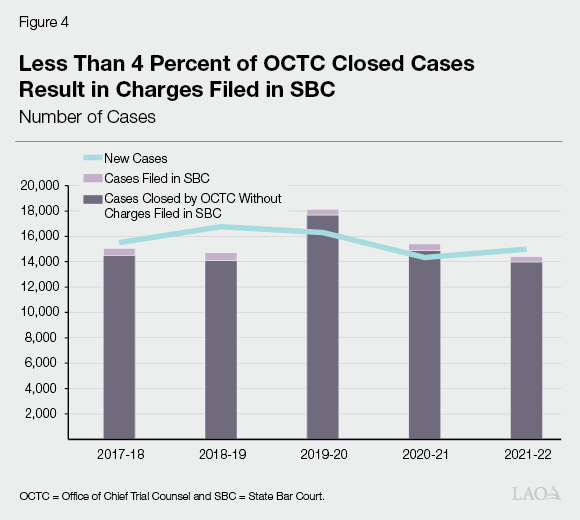

As reported by the State Bar, Figure 4 shows the number of cases that are opened and closed by OCTC as well as the number of cases that resulted in the filing of charges. State law allows OCTC to exclude certain types of workload (such as resolving complaints related to the unauthorized practice of law) when reporting certain workload data. Accordingly, Figure 4 excludes such data, which means that the workload numbers will not be the same as those shown in Figure 3, which reflects total workload. As shown in Figure 4, the number of cases opened and closed have fluctuated in recent years. In 2021‑22, the State Bar reports opening 14,989 cases and closing 14,409 cases. Of the cases closed, 13,979 cases (or 97 percent) were closed without charges being filed and 430 case (or 3 percent) resulted in charges being filed in the SBC. Less than 4 percent of OCTC cases closed annually resulted in charges filed in SBC between 2017‑18 and 2021‑22.

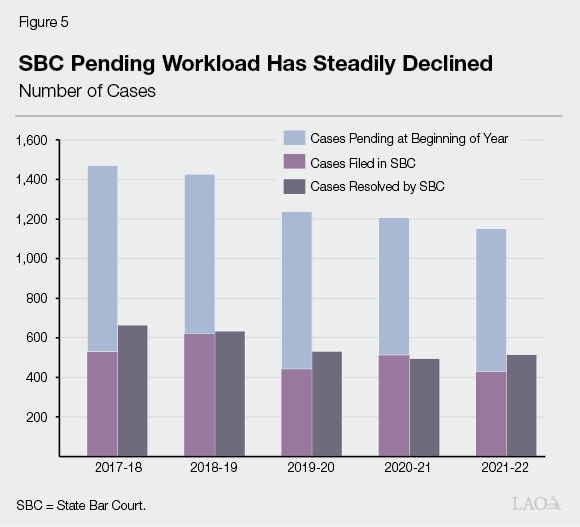

SBC Workload. As shown in Figure 5, the number of cases received and resolved annually by SBC has fluctuated in recent years. In 2021‑22, SBC received a total of 430 cases and closed 514 cases. Of the cases closed, about 89 percent were closed with SBC imposing disciplinary action. The number of cases closed has generally exceeded the number of cases opened in recent years. This has resulted in a steady reduction in the number of cases pending at the end of the year. Specifically, SBC had 637 cases pending at the end of 2021‑22—a decrease of nearly 22 percent from 2017‑18.

Case Processing Time Frame Established by Statute for OCTC Workload. State law currently requires the State Bar to complete the first three stages of the disciplinary process—specifically, for OCTC to dismiss a complaint, admonish an attorney, or file formal charges against an attorney—within six months (or 180 days) after receipt of a written complaint for “noncomplex” cases and 12 months (or 365 days) for “complex” or “complicated” cases. The Chief of OCTC determines which cases are complex or complicated.

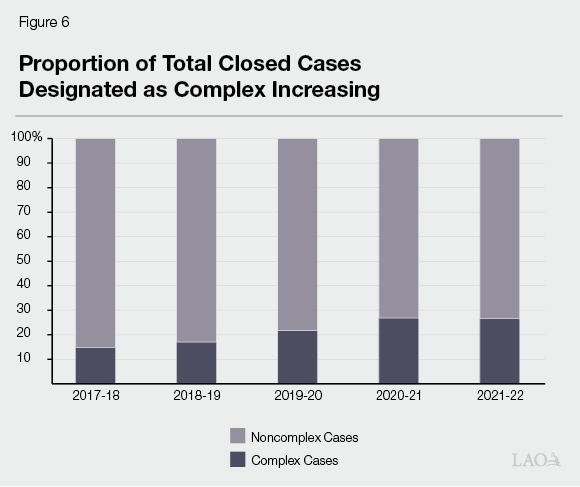

The majority of OCTC closed cases are designated as noncomplex. In 2021‑22, OCTC closed 14,409 cases—10,593 noncomplex cases (or 74 percent) and 3,816 complex cases (or 27 percent). However, as shown in Figure 6, the proportion of total cases closed that are designated as complex has increased in recent years. In 2017‑18, the State Bar reports closing a total of 15,052 cases—which included 2,241 complex cases (or 15 percent). This means that the proportion of complex closed cases has increased by 12 percentage points since 2017‑18.

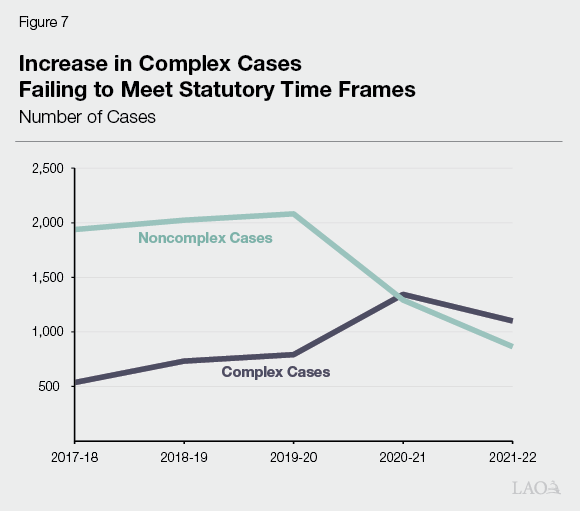

The State Bar reports that the majority of its closed cases meet the time frames specified in statute for the first three stages of the disciplinary process. Specifically, in 2021‑22, the State Bar reports that 12,444 closed cases (or 86 percent) met these time frames and 1,965 closed cases (or 14 percent) did not. The number of noncomplex closed cases not meeting these time frames has decreased in recent years. Specifically, 865 noncomplex cases (or 8 percent) closed in 2021‑22 did not meet these time frames—a decrease from the 1,938 noncomplex cases (or 15 percent) closed in 2017‑18 that did not meet these time frames. In contrast, as shown in Figure 7, the number of complex closed cases not meeting these time frames increased in recent years. Specifically, the number of closed complex cases not meeting such time frames increased from 536 cases (or 24 percent) in 2017‑18 to 1,344 cases (or 33 percent) in 2020‑21, before decreasing slightly to 1,100 cases (or 29 percent) in 2021‑22.

How Does OCTC Operate?

OCTC Generally Structured Around Teams. In 2021, OCTC reported 280 staff positions. This amount consisted of 96 attorneys (34 percent); 82 investigators (29 percent); 73 support staff (26 percent), such as paralegals; and 29 other administrative staff (10 percent). The majority of attorneys, investigators, and support staff are organized by teams, with each team reporting to a single supervising attorney. Staff physically located in the State Bar’s San Francisco and Los Angeles offices are fully integrated within these teams.

For example, a couple members of a team may be physically located in San Francisco while the rest are located in Los Angeles.

In general, there are two different types of OCTC teams based on their responsibilities—intake teams and trial teams. Intake teams are responsible for the Intake Stage. OCTC maintains two intake teams that each consist of around seven to nine attorneys and four to five support staff. Trial teams are responsible for the Investigation, Charging, and Hearing Stages. OCTC maintains 13 trial teams that each generally consist of around 4 to 6 attorneys, 6 investigators, and 3 to 4 support staff. The one exception is the trial team designated as an “expeditor team” responsible for addressing complaints OCTC believes can be resolved quickly. This expeditor trial team consists of four attorneys, eight investigators, and one support staff. Of the 13 trial teams, three of them each respectively specialize in addressing immigration, unlawful practice of law, and client trust account matters. (The team specializing in client trust account matters is currently a pilot program.) The remaining trial teams (including the expeditor trial team) are typically generalists capable of processing nearly all complaint types.

Cases Prioritized Based on Potential Public Risk. OCTC currently prioritizes cases into three categories based on the risk of potential impact on members of the public. Priority One cases involve serious misconduct or other behavior with the potential for significant or ongoing harm to members of the public. According to the State Bar, the number of cases referred to the trial teams for investigation that can be designated as Priority One is capped at 20 percent due to the availability of resources. Priority Two cases are those that can be easily resolved or have been identified as needing quick (or “expedited”) investigation to determine if significant harm could occur. According to the State Bar, Priority Two cases are expedited by assigning them specifically to the expeditor trial team and eliminating certain OCTC tasks. For example, formal investigation plans, investigator reports, and closing memos prepared by investigators and approved by attorneys may be waived for such cases. The State Bar estimates that Priority Two cases represent about 20 percent of cases not closed in the Intake Stage. Priority Three cases consist of all other cases. Irrespective of their priority designation, some cases may be designated as “major” cases—typically cases those that meet certain criteria such as those alleging significant public harm, likely to generate publicity, or likely to be of special interest to the public.

Cases Referred for Investigation Prosecuted Vertically. OCTC’s two intake teams typically review submitted complaints, resolve those that can be closed, and assign case prioritization to those being referred to the trial teams. Cases are typically assigned to trial teams based on the size of the team. When a case is assigned to a specific trial team, the supervising attorney of the team typically assigns both an investigator and attorney to the case in a vertical prosecution model—meaning assigned staff stay with a case from the case initiation to resolution. (In contrast, a horizontal prosecution model has different staff assigned to specific activities or stages of the case.) During the Investigation Stage, the investigator generally obtains necessary evidence, while the attorney approves documents (such as investigative plans and closing memos) and provides legal advice on the case. During the Charging Stage and Hearing Stage, the attorney typically determines whether additional investigation is needed, files charges and/or settles the case, and prosecutes the case in the SBC.

Workload Formula Developed and Used to Identify OCTC Staffing Need. In 2018, the State Bar implemented a workload study to identify the staffing needs for its disciplinary system. Specifically, for OCTC, the State Bar used a random time‑study methodology—similar to one used by the judicial branch—to identify all staff activities required to process a case as well as the amount of staff time associated with these activities. The State Bar then used these data to calculate one set of “case weights” for all case types that represent the average amount of staff time each component of a case is expected to take. For example, the State Bar calculated that intake activities average 110 minutes per case while enforcement activities average 3,332 minutes per case. The State Bar then used (1) historical data to identify patterns between the number of filled investigator positions and the median amount of time required to close a case and (2) staffing ratios (such as a staffing ratio of 1.4 attorneys for every investigator) to calculate the number of staff needed to meet the existing statutory time frame of 180 days to dismiss a complaint, admonish an attorney, or file formal charges against an attorney after receipt of a written complaint for noncomplex cases.

In 2021, the State Bar reviewed the workload formula and identified potential areas of refinement. For example, the State Bar examined six broad categories of case types—such as the notification from banks about insufficient funds in client trust accounts and certain general complaints filed by members of the public—and identified that the number of staff and resources needed to process cases could differ by case types.

How Does the Legislature Conduct Oversight of the Disciplinary Process?

Legislature Has Various Tools Available. The Legislature has various tools to conduct oversight of the disciplinary process. This includes conducting policy hearings, confirming the appointment of the Chief of OCTC, imposing reporting or other requirements on the State Bar through statute, and directing other state entities—particularly the California State Auditor’s Office (CSA) and our office—to conduct evaluations and assessments. Key reporting or evaluation requirements in recent years include:

- Annual Discipline Report. State law requires the State Bar to submit an annual report by October 31 describing the performance of the disciplinary system for the most recent fiscal year. State law requires the report to include a range of information—such as the number of inquiries received and their disposition, the median and average processing times, and formal disciplinary outcomes. The statistical information must be presented in a consistent manner for year‑to‑year comparison and, if available, must include the required information for the preceding five years. This annual report is presented to the Chief Justice, the Governor, the Speaker of the Assembly, the President pro Tempore of the Senate, and the Assembly and Senate Judiciary Committees. The specific requirements included in statute have been modified over time to reflect legislative oversight needs.

- State Auditor Performance Audits. State law requires the State Bar to contract with CSA to conduct a performance audit of the State Bar’s operations every two years. State law can require certain information be included in particular years. For example, state law requires the 2023 CSA audit (currently in progress) to evaluate the operations of each program—such as OCTC—supported by the annual licensing fees and whether there are appropriate program performance measures in place. The 2023 audit is also required to evaluate how the State Bar administers discipline cases that require an outside investigator or prosecutor and how that process can be improved, including the cost‑effectiveness and timeliness of such investigations and prosecutions. The audit in progress shall be presented by April 2023 to the State Bar Board of Trustees, the Chief Justice, and to the Assembly and Senate Judiciary Committees.

- One‑Time Evaluations. Statute has been enacted in recent years to require one‑time evaluations related to aspects of the State Bar’s disciplinary process. For example, SB 211 required CSA to submit a report by April 2022—which has been completed—evaluating whether the disciplinary process adequately protects the public from attorney misconduct, including whether the State Bar takes reasonable steps to determine the existence and extent of alleged misconduct. Additionally, our office was directed to conduct an evaluation of the State Bar’s proposed fee increase in 2019, since a portion of the increase would support additional OCTC disciplinary staff.

Reports Consistently Raised Concerns With Disciplinary Process and Level of Resources Needed. Various CSA reports have regularly raised concerns with the efficacy of the disciplinary process, the reporting of data, and the use and/or level of resources. Similarly, our office also raised some concerns in 2019. Key findings and recommendations from these recent reports include:

- Some Attorneys Not Held Accountable for Misconduct. The April 2022 CSA report found that (1) some cases were prematurely closed that warranted further investigation and potential discipline, (2) weak processes allowed attorneys who engaged in misconduct in other states to continue practicing in California, and (3) information that the State Bar provided its staff limits their ability to identify patterns of complaints. The report also found that weak safeguards have hampered the State Bar’s ability to prevent repeated violations associated with client trust accounts. To address these concerns, CSA presented various recommendations including directing the State Bar revise policies to (1) define specific criteria for the closure of cases using nonpublic disciplinary measures, (2) begin using complaint type categories when determining whether to investigate a complaint in order to more easily identify patterns of similar complaints against an accused attorney, and (3) require staff take certain actions when investigating client trust account complaints.

- Organizational Changes Decreased Operational Efficiency. In April 2021, CSA found that the State Bar’s changes to its disciplinary system—specifically, converting OCTC trial teams from specialist teams that handle particular case types to generalist teams who generally handle all case types and promoting some of its most senior attorneys to full‑time supervisors in 2017—significantly reduced the efficiency of the system by significantly increasing case processing times and the backlog of cases even with attorneys being disciplined at a significantly lower rate. To address these concerns, the report made various recommendations, including directing the State Bar to (1) assess how OCTC’s current organizational structure has impacted its ability to efficiently resolve cases and determine whether additional changes are needed and (2) establish a backlog metric, determine appropriate backlog goals, and determine the level of resources needed to meet such backlog goals.

- Annual Discipline Report Needs Improvement. The April 2021 CSA report also found that the State Bar’s lack of adequate monitoring has hampered its ability to detect problems in its disciplinary system. CSA also raised concerns with the annual discipline report submitted by the State Bar, including that the report does not fully and consistently provide information about the disciplinary system. To address these concerns, CSA made various recommendations, including requiring appropriate State Bar review and approval of the annual discipline report to ensure information is accurate, complete, and consistent.

- Request for Additional Resources Premature. In 2019, the State Bar proposed increasing the annual licensing fee by $40 for active attorneys to support 58 additional OCTC staff to improve disciplinary case processing times. Both the April 2019 CSA report and our June 2019 report found that this request was premature since recently implemented operational changes—such as to the existing organizational structure and case prioritization methodology—were still in the process of being implemented and would not be reflected in the workload study used to calculate the additional resources requested. As such, both offices recommended a fewer number of positions until the impact of the recently implemented changes were known. This resulted in a lower fee increase than originally proposed.

- Workload Formula May Require Revision. In 2019, both CSA and our office raised concerns that the State Bar’s workload study may not accurately identify staffing needs. Our office specifically found that (1) the case weights capture the average amount of time it takes for OCTC to process a case with existing staffing levels, rather than the time that would be needed to process cases within existing statutory time frames; (2) different case weights may be needed for different complaint types or priority categories to the extent they require different levels or combinations of disciplinary tasks; and (3) fewer staff could be required if the Legislature changed the statutory time frames.

- Proposal for Annual Inflationary Adjustment Lacked Justification. In 2019, the State Bar requested the authority to annually adjust the annual licensing fee, including the existing $25 disciplinary fee (as shown in Figure 1 above), to account for inflation. Our office found that there was a lack of justification for the proposed authority and that the request could severely limit legislative oversight over State Bar operations. Our overall review of State Bar programs indicated that increased legislative oversight could be beneficial and suggested various options for legislative consideration—including potentially including the State Bar in the annual state budget process or approving a fee specifically to support the disciplinary process.

The Legislature has used these various reports in different ways—including changing existing state law, determining the appropriate fee level to approve, and informing discussions with the State Bar. For example, as recommended by CSA, the Legislature amended state law to change the due date for submission of the State Bar’s annual discipline report from April 30 to October 31 of each year in order to provide the Legislature with sufficient time to review the discipline report before considering action on the annual fee bill.

State Bar Proposal

Analysis Required by SB 211. Senate Bill 211 expressed the Legislature’s intent to codify new case processing standards (or time frames) to replace the existing statutory time frames for OCTC to dismiss a complaint, admonish an attorney, or file formal charges against an attorney. To assist with this, SB 211 required the State Bar to propose case processing standards by October 31, 2022 for review by our office. Specifically, the legislation directed the State Bar to propose standards with the goals of (1) resolving cases in a timely, effective, and efficient manner within OCTC; (2) allowing for only small backlogs of attorney discipline cases; and (3) protecting the public. Certain case types—such as the unauthorized practice of law—would be excluded from these standards. The new standards should also consider all relevant factors—including the mechanics of the discipline process, public risk, reasonable public expectations for the resolution of cases, and the complexity of cases. In preparing the standards, the State Bar was required to review attorney disciplinary system case processing standards in at least five states with strong and effective systems, consult with experts on attorney discipline, and review relevant CSA and LAO reports. Finally, SB 211 required that the report from the State Bar include the staffing requirements needed to achieve the new case processing standards being proposed.

The State Bar provided its report on October 28, 2022. In this section, we summarize the key components of the report: (1) new case processing standards, (2) the establishment of a backlog goal and metrics for measuring it, and (3) a staffing analysis.

New Case Processing Standards

Prioritizes Cases Based on Both Risk and Complexity. As discussed earlier, cases are currently prioritized based on risk to members of the public. The State Bar proposes to instead prioritize cases based on both risk and case complexity. Higher‑risk cases would include those where the alleged attorney’s behavior has caused, or has the potential to cause, significant harm to clients and members of the public. Such cases could include those where clients may have been misled when settling cases, misappropriation of client funds for which restitution has not been paid, or allegations of misconduct to vulnerable populations (such as immigrants and seniors). It could also include cases in which there are multiple complaints or recurring complaints against the same attorney. The State Bar estimates that 30 percent to 40 percent of cases not closed in Intake would be designated as higher‑risk cases.

Higher‑complexity cases tend to require longer investigation. For example, such cases could include those cases (1) where multiple charges against an attorney arise from multiple events, (2) designated as “major cases,” (3) requiring subpoenas to banks or other third‑party entities; (4) where analysis of a large number of documents (such as bank records) may be needed; or (5) where an accused attorney is unresponsive. According to the State Bar, these are the same factors it currently uses to designate cases as complex.

Proposes Average Case Processing Times in Six Categories. The State Bar proposes six case categories based on when a case is closed, the stage at which it is closed, and the case risk/complexity. Specifically, the six case categories are: (1) closed in Intake; (2) high‑risk, noncomplex cases closed after Investigation; (3) low‑risk, noncomplex cases closed after Investigation; (4) high‑risk, complex cases closed after Investigation; (5) low‑risk, complex cases closed after Investigation; and (6) cases closed or filed in Charging. As shown in Figure 8, for each case category, the State Bar proposes an average case processing standard. For example, the State Bar proposes a 120‑day average case processing standard for closing high‑risk, noncomplex cases after Investigation—a decrease of 47 days (or 28 percent) from the current average. Across all six categories, the State Bar proposes to reduce average case processing times by 24 percent to 33 percent. Times in which cases are deferred (or suspended) pending separate criminal or civil litigation are excluded from the case processing standards.

Figure 8

State Bar Proposed Average Case Processing Times Compared to

Current Average Case Processing Times

|

Case Category |

Average Case Processing Times |

|||

|

Proposed |

Current |

Difference |

Percent |

|

|

1: Closed in Intake |

30 |

42 |

‑12 |

‑29% |

|

2: Closed After Investigation—High‑Risk, Noncomplex Cases |

120 |

167 |

‑47 |

‑28 |

|

3: Closed After Investigation—Low‑Risk, Noncomplex Cases |

150 |

197 |

‑47 |

‑24 |

|

4: Closed After Investigation—High‑Risk, Complex Cases |

180 |

248 |

‑68 |

‑27 |

|

5: Closed After Investigation—Low‑Risk, Complex Cases |

210 |

307 |

‑97 |

‑32 |

|

6: Closed or Filed in Charging |

300 |

449 |

‑149 |

‑33 |

The State Bar calculated the proposed average case processing standards by taking current case processing times for cases closed or filed between 2018 to 2021 (four years) and adjusting them in various ways. First, the State Bar did not include the number of days between case processing events—meaning from the end of one processing event to the start of the next processing event—if the number of days exceeded 59 days. Specifically, if the time period between two different events was 60 days or more, the entire time period would be removed before average processing times were calculated. For example, if a case took 300 days but had a 65 day time period between processing events, the case processing time for that case would be adjusted to 235 days. According to the State Bar, 44 percent of cases closed or filed between 2018 to 2021 were impacted by this adjustment. Second, the processing times were adjusted to be more similar to the caseload processing standards of six other states: Arizona, Colorado, Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey, and Texas. The times were further adjusted based on the State Bar’s consultation with three experts on attorney discipline and the State Bar’s review of reports by CSA and our office related to the disciplinary system. Finally, the State Bar conducted five internal focus groups of OCTC attorneys and investigators to solicit feedback on the proposed standards, compared the proposed standards to the standards used by Department of Consumer Affairs (DCA) licensing boards and bureaus, and solicited public feedback.

Changes Definition of “Filing Charges” for Case Processing Standards. The State Bar proposes to change the definition of filing charges for the purpose of the case processing standards. (This impacts the proposed case category: “Closed or Filed in Charging.”) As discussed above, if requested by the accused attorney, at least one ENEC is mandatory before charges can be filed. Since such meetings require coordination with both the accused attorney and the SBC, the State Bar asserts that OCTC loses control over the timeliness of the charging process at that time. As such, the State Bar proposes to change the definition of “Filed in Charging” to mean the date the accused attorney is notified of their right to request an ENEC—if one is ultimately conducted. If an ENEC is not conducted, the definition remains the date on which OCTC files charges or negotiated resolution with the SBC. If this proposed definition is not adopted, the State Bar recommends increasing the proposed average case processing standard for “Cases Closed or Filed in Charging” from 300 to 330 days.

Establishment of Backlog Goal and Metrics to Measure Goal

Proposes Backlog Goal of 10 Percent or Less. The State Bar proposes defining an appropriate backlog goal of 10 percent or fewer cases. According to the State Bar, this means that no more than 10 percent of cases should be in backlog status at any time.

Proposes Backlog Standards for Each Proposed Case Processing Standard. For each of the proposed case processing standards discussed above, the State Bar proposes a calculated backlog time standard. Specifically, the State Bar proposes backlog standards that are 150 percent of the proposed average case processing time for each case category. For example, as shown in Figure 9, the State Bar proposes an average case processing standard of 120 days for high‑risk, noncomplex cases closed in the Investigation Stage and a backlog standard of 180 days. This means that high‑risk, noncomplex cases that take longer than 180 days to close in the Investigation Stage would be deemed to be “closed in backlog” or “not meeting goals.” The number of such cases in each case category would be added together to calculate a single backlog measure.

Figure 9

State Bar Proposed Backlog Standards

|

Case Category |

Average Case Processing Times |

Backlog Standard |

|

1: Closed in Intake |

30 |

45 |

|

2: Closed After Investigation—High‑Risk, Noncomplex Cases |

120 |

180 |

|

3: Closed After Investigation—Low‑Risk, Noncomplex Cases |

150 |

225 |

|

4: Closed After Investigation—High‑Risk, Complex Cases |

180 |

270 |

|

5: Closed After Investigation—Low‑Risk, Complex Cases |

210 |

310 |

|

6: Closed or Filed in Charging |

300 |

450 |

Staffing Analysis

Defers Comprehensive Staffing Analysis to 2023. Senate Bill 211 required that the State Bar provide a staffing analysis to identify the resources needed to achieve the proposed case processing standards. The State Bar states that a comprehensive final staffing study will be deferred and instead initiated in 2023. The reasons for this delay are to incorporate legislative direction on the proposed case processing standards as well as various OCTC operational changes that are currently in progress or are being considered. Examples of such operational changes include:

- Potential changes related to OCTC’s generalist teams after analyzing various opinions and concerns raised by employees, stakeholders, and others about these teams.

- Potential changes to reduce or simplify unnecessary steps, as well as use the appropriate staff for certain tasks (for example, whether certain tasks are best conducted by attorneys or support staff).

- Distribution of fliers to all accused attorneys advising them of the importance of having counsel in State Bar disciplinary proceedings in January 2022. (We note that this change resulted from a State Bar contracted study on racial disparities in attorney discipline that found accused Black attorneys were less likely to be represented by counsel than white attorneys.)

- Deployment of operational reports to track key performance measures in 2022 and plans on continuing to develop and test new data reports to help OCTC staff improve efficiency.

The State Bar indicates that the comprehensive staffing analysis will consider a range of factors. These include: risk and complexity to ensure that different cases receive case weights; staffing needs, responsibilities, and expertise (such as the impact experience, turnover, and training has on workload processing speed and the amount of time available for work); the appropriate ratios of staff types (such as attorneys versus administrative support staff); and the allocation of staff time across complaint types and case processing activities.

Provides Preliminary Estimates of Staffing and Resource Need. To meet the requirements of SB 211, the State Bar provides preliminary estimates of the level of staffing and resources needed to meet the proposed case processing standards. Two different methods were used to calculate these preliminary estimates—the workload formula and a mathematical calculation. Figure 10 summarizes the estimated staffing needs under each method.

- Workload Formula. This method is based on the existing workload formula developed by the State Bar. The workload formula calculated a need for an additional 119 positions (or a 44 percent increase in staff based on filled positions)—47 attorneys, 25 investigators, 40 support staff, and 7 supervisors. An estimated $16.3 million would be needed to support these additional positions. To support this increased cost, an estimated $83 increase in the annual licensing fee paid by active attorneys would be required.

- Mathematical Calculation. This method mathematically compares the changes in the current and proposed case processing standards, and assumes that a similar increase in staffing levels would be needed to achieve them. Specifically, the State Bar noted that the proposed caseload standards would result in the reduction of the average case processing times by 29 percent. The State Bar then assumed that a similar percentage increase in investigator staffing levels would be needed to achieve the proposed caseload processing standards. Increases to other positions, such as attorneys, were based on ratios similar to the workload formula. For example, the calculation included a staffing ratio of one attorney for every investigator. In total, this method calculated a need for an additional 78 positions (or a 29 percent increase in staff based on filled positions)—23 attorneys, 23 investigators, 25 support staff, and 7 supervisors. An estimated $10.6 million would be needed to support these additional positions. To support this increased cost, an estimated $55 increase in the annual licensing fee paid by active attorneys would be required.

Figure 10

State Bar Preliminary Estimate of Additional Staffing Needs

|

Staff Type |

Filled Positions (2021)a |

Workload Formula Calculation |

Mathematical Calculation |

|||

|

Additional |

Percent |

Additional |

Percent |

|||

|

Attorney |

80 |

47 |

59% |

23 |

29% |

|

|

Investigator |

79 |

25 |

32 |

23 |

29 |

|

|

Support |

88 |

40 |

45 |

25 |

28 |

|

|

Supervisor |

25 |

7 |

28 |

7 |

28 |

|

|

Totals |

272 |

119 |

44% |

78 |

29% |

|

|

aDiffers slightly from earlier‑referenced numbers due to various factors, such as whether positions were filled. |

||||||

Analyst’s Review of State Bar Proposal

The State Bar’s submitted report fulfills the requirements specified in SB 211. Specifically, the State Bar developed the standards after considering the timely and effective processing of cases, potential impacts on public protection, and the allowance of small backlogs of attorney discipline cases. As required, to inform this work, the State Bar reviewed disciplinary systems in six other states, consulted with experts on attorney discipline, reviewed CSA and LAO reports, and solicited public feedback on the proposed standards.

In this section, we provide our review of the State Bar’s report. Specifically, we provide our assessment and identify key questions for legislative consideration for the entire proposal as well as for each of the three key components of the report: (1) the proposed new case processing standards, (2) the establishment of a backlog goal and metrics to measure the goal, and (3) the staffing analysis.

Overarching Comments

Assessment

Assumes Existing Disciplinary Process Is Generally Reasonable. While the State Bar continues to consider operational and procedural changes to improve OCTC efficiency and efficacy, the State Bar’s proposed case processing standards generally assume that the existing steps of the disciplinary process are reasonable and should be maintained.

Lack of Legislative Approval of State Bar Budget Can Make Oversight Difficult. As discussed above, unlike nearly all other state licensing entities that regulate professions, the State Bar’s budget is not reviewed by legislative budget committees through the annual state budget process. The State Bar is also not required to justify changes to existing budget levels and requests for additional revenues in the same manner as these other entities. This can make it difficult for the Legislature to ensure that the fees authorized annually align with expenditure levels that match legislative priorities and expectations for how such funding will be used.

Key Questions for Legislative Consideration

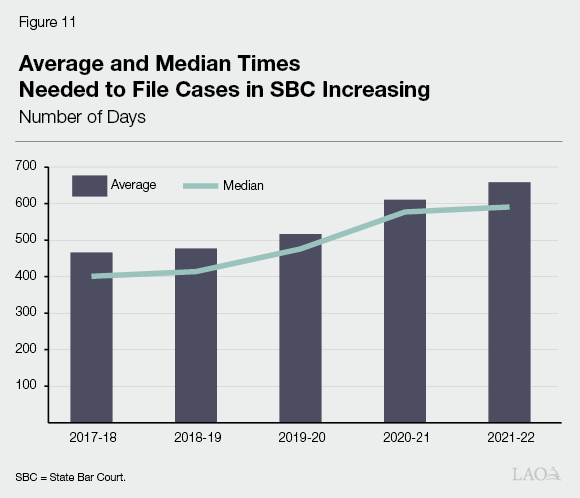

Are Existing Disciplinary Procedures Reasonable? The Legislature will want to consider whether the existing disciplinary procedures are reasonable or if changes are warranted. This is because the specific steps in the process impact how long it takes to resolve cases, how OCTC should be organized and operated, and the specific level of resources needed. For example, as shown in Figure 11, the average amount of time needed to file cases in the SBC increased by 41 percent between 2017‑18 (466 days) and 2021‑22 (658 days), and the median amount of time increased by 47 percent between 2017‑18 (401 days) and 2021‑22 (591 days). To the extent that that Legislature would like to reduce such times, it could consider eliminating ENECs. We note that the attorney discipline experts consulted by the State Bar noted that California is the only jurisdiction that they are aware of which uses a formal ENEC before charges are filed. The experts suggested eliminating the ENEC prior to charging and shifting it to after charges have been filed in the SBC. Prior to charges being filed, accused attorneys would continue to be able to informally pursue settlement discussions with OCTC (which they currently are able to do).

What Level of Legislative Oversight Is Needed? The Legislature will want to consider what level of oversight it wants to exercise over State Bar processes and funding. As noted above, we previously indicated in 2019 that increased legislative oversight could be beneficial. One such option to consider is including the State Bar in the annual state budget process to increase legislative oversight by leveraging the expertise of the budgetary committees to evaluate State Bar funding requests in a manner similar to other state departments. (The Assembly and Senate Judiciary Committees would retain policy oversight. This would be similar to what is in place for certain other state licensing departments.) Additionally, requiring the State Bar to submit budgetary information in a manner similar to other state departments would enable easier comparison to ensure standardized or similar treatment across the various departments responsible for licensing professions. Another option to increase transparency and oversight is to consider a fee specifically to support the disciplinary system to ensure the State Bar uses the funding for this specific purpose. The current $25 disciplinary fee generates around $5.7 million annually—significantly less than is needed to support the entire disciplinary system. The Legislature could consider adjusting this fee and directing that this fee be placed in a special fund specifically for disciplinary system purposes. This would enable the Legislature to ensure that the authorized level of funding was used to support legislatively expected service levels.

New Case Processing Standards

Assessment

Reasonable to Include Both Risk and Complexity in Case Prioritization System… We find that it is reasonable for OCTC to prioritize cases based on both the actual or potential risk of public harm and case complexity. Prioritizing and more quickly addressing high‑risk cases can help stop an attorney from continuing to engage in problematic behavior and can help obtain justice or restitution for those who are wronged. Additionally, it is reasonable to expect more complex cases to take more time than noncomplex cases to thoroughly investigate, obtain clear and convincing evidence, and resolve. The failure to dedicate sufficient investigatory and prosecutorial time to high‑risk and complex cases could result in harm to the public to the extent accused attorneys do not ultimately receive the appropriate level of discipline. We would note, however, that the specific definitions of what types of cases constitute high/low risk as well as complex/noncomplex will be important and should be consistently defined over time. Without clear and consistent definitions, this could result in data reporting fluctuating over time and make comparison difficult—thereby making it difficult to conduct meaningful oversight of OCTC performance. As noted before, existing statute authorizes the Chief of OCTC to determine which cases are complex.

…But Unclear Why Proposed Case Processing Standards for Cases Closed or Filed in Charging Do Not Incorporate Risk. Two of the six case categories—specifically those closed in Intake and those closed or filed in Charging—for which the State Bar proposes case processing standards do not explicitly differentiate cases based on risk and complexity. As such, only one case processing standard is proposed for those two case categories—in contrast to the four different standards proposed for cases closed after Investigation. According to the State Bar, cases closed in Intake should inherently be cases that are low risk and noncomplex. Cases of greater risk and complexity should be referred for investigation. We find this logic to be reasonable. For cases closed or filed in Charging, the State Bar believes that cases that reach this stage are inherently more complex in nature and that risk does not greatly impact the amount of time needed to process the cases. However, if high‑risk cases are prioritized in the Investigation Stage, it would be reasonable to assume that those cases would be referred to the Charging Stage more quickly for resolution. This means that the overall amount of time needed to process high‑risk cases would likely be less than the amount of time needed to process low‑risk cases. Arguably, such cases should be expected to be resolved more quickly given the actual or potential for public harm.

Case Processing Standards Do Not Reflect Full OCTC Workload. Both the existing statutory time frames and the proposed case processing standards do not reflect full OCTC workload. Specifically, the case processing standards do not include the Hearing Stage in which OCTC staff engage in activities to prosecute and resolve cases in SBC. Such a metric would be helpful to capture how long it takes to resolves cases generally. For example, DCA includes a formal discipline performance benchmark of 540 days from the complaint receipt through the completion of the entire disciplinary process for cases that are forwarded to the Attorney General for disciplinary proceedings (including intake and investigation).

OCTC should not be solely responsible for achieving a particular time standard as case processing in the Hearing Stage requires coordination with SBC and accused attorneys. However, OCTC is a key participant whose actions will impact the overall ability to effectively resolve cases in the Hearing Stage. As such, OCTC should continue to monitor and to improve the efficacy and efficiency of its actions in this stage. A time standard would provide an expectation for how long it should take to resolve those cases that may result in the most severe disciplinary actions. This serves as a benchmark to measure against actual completion times. In combination with other reporting requirements, the State Bar and Legislature would be better positioned to monitor and identify the particular areas where delays are occurring or where operational, procedural, or staffing changes could improve case processing efficiency or quality.

For example, the Department of Justice (DOJ)—who is responsible for representing DCA licensing boards and bureaus before the Office of Administrative Hearings—reports annually on key metrics to provide greater insight into DOJ‑specific actions contributing to overall formal discipline case processing times. Such metrics include the average, median, and standard deviation number of days (as well as the number of cases) for fully adjudicated matters from receipt of the complaint from investigators to when charges are filed; from the filing of an accusation to when a stipulated agreement is reached; from the filing of charges to when a hearing date is requested; and from the date a hearing was requested to when a hearing commenced. We note that OCTC and SBC are fully located within the State Bar, which should make cooperation easier, in contrast to DCA licensing disciplinary processes that require coordination across several separate state entities.

New Filed in Charging Definition Further Reduces Measurement of OCTC Workload. As discussed above, the State Bar proposes to change the definition of filed in Charging to mean the date an accused attorney is notified of their right to request an ENEC—if such a meeting is ultimately conducted. If a meeting is not conducted, the definition remains the date on which OCTC files charges or a negotiated resolution with the SBC. This new definition could exclude a potentially significant amount of time and OCTC workload from the proposed case processing standards. According to the State Bar, more than half of cases that request an ENEC will require multiple ENECs. Multiple ENECs can add an average of 79 days to case processing times for cases to close or for charges to be filed in the Charging Stage.

Unclear Extent to Which Proposed Standards Are Reasonable. In developing the proposed case processing standards, the State Bar assumed that it was unreasonable for there to be time periods of 60 days or more between case processing events. This is because, during such time periods, cases were effectively sitting idle awaiting OCTC staff to take action. The State Bar acknowledges that this is an aggressive approach that assumes that such idle time periods will no longer occur—rather than assuming that idle periods will be shorter in length. It also acknowledges that this approach could mean that time needed for the investigation process may have been mathematically removed as well. However, the State Bar believes that this is an appropriate starting point as it is reasonable to expect that such idle periods should not exist in cases that have not been deferred and that it provides an estimate of the minimum amount of time required for thorough investigation when there is sufficient staff and resources.

We find that it is reasonable to attempt to minimize the amount of time that cases are sitting idle. However, it is unclear to us how much necessary investigatory or charging time was removed as part of this analysis. For example, conversations with State Bar staff indicated that it could sometimes take more than 60 days for banks to provide documents that are subpoenaed to investigate cases that involve client trust accounts. Such cases that require this investigatory step likely are forced to sit idle while OCTC staff wait for documents to be provided. However, the cases processing standards assume no unavoidable idle times like this take place despite the delays being arguably justified as OCTC requires such information (and cannot obtain it via alternative means) to fully investigate and resolve such cases. Similarly, an April 2021 CSA report documented that the State Bar indicated that it typically takes six months (180 days) or more for the federal government to provide requested immigration records. It is unclear the extent to which OCTC will be able avoid such idle times and/or if they impact particular types of cases. As such, it is unclear the extent to which these case processing standards are reasonable. If case processing standards are unreasonable, it is possible that the quality of case processing—such as the thoroughness of investigations or the proposed disciplinary action—will decrease in order to meet the standards. For example, a July 2015 CSA audit found that the State Bar’s focus on reducing an excessive backlog of disciplinary cases in the years preceding the audit resulted in a decrease in the severity of discipline imposed.

We note that alternative approaches may have also been possible. For example, the State Bar could have identified those cases that it believed to be accurate representations of the amount of time needed to process specific types of complaints and used them to calculate proposed case processing standards. In such an approach, there may be time periods where a case sits idle for more than 60 days—which is reasonable if there is a clearly identified rationale and need for the case to sit idle. The benefit of such an approach is that the resulting case processing standards would be based on actual investigatory and prosecutorial need.

Unclear Impact of Implemented or Potential Operational and Procedural Changes. As noted above, various operational and procedural changes to OCTC processes have recently been implemented. The full impacts of some of these changes are unknown—such as the practice of providing flyers to all accused attorneys notifying them of the benefits to hiring legal counsel as of January 2022. To the extent more legal counsel is hired, it could result in cases taking more time (such as if the accused attorney refuses to settle and chooses to fight the case) or less time (such as if hired counsel helps an accused attorney realize that early settlement of a case would be beneficial). Other changes have drawn concern and/or require additional evaluation. For example, CSA recently identified concerns that the organizational shift to generalist teams decreased operational efficiency, even with attorneys being disciplined at a lower rate. Additionally, the State Bar notes that other potential changes—such as those raised in conversations with staff and stakeholders during the preparation of the State Bar’s case processing report—are in the process of being considered and/or implemented. We also note that other changes could be forthcoming as a new Chief of OCTC joined the State Bar in October 2021. Lacking information on the impact of such changes makes it difficult to assess whether they will help staff achieve the proposed case processing standards.

Annual Reporting Requirements Will Need to Be Updated. State law requiring reporting of data and metrics in the State Bar’s annual discipline report will need to be updated, regardless of which specific case processing standards are finally adopted by the Legislature. Specific data and metrics will be needed to measure annual performance against any adopted benchmarks.These include those directly related to the proposed standards. For example, such data and metrics could include average processing times for cases closed at the various disciplinary stages categorized by their risk and complexity, as well as the number of cases deferred and the amount of time that passes while the cases are deferred. Other data and metrics would also provide helpful context. For example, it could be helpful to have mean, median, and standard deviation data between specific steps taken by staff in the disciplinary process—such as the time period between complaint receipt and referral to investigation, as well as the time period between the completion of investigation to the notification of the accused attorney of their right to an ENEC before charges can be filed. Without such metrics, it will be difficult for the Legislature to conduct meaningful and consistent oversight of the disciplinary process and identify potential areas of improvement or concern.

Additionally, to ensure that data is comparable across reports, it is important to clearly specify the definitions for the statistics and metrics included in the report. This should include a requirement for the State Bar to provide clear explanations any time changes are made in the definitions, criteria, or methodologies used to pull and report data. This will ensure that the Legislature receives the necessary information and that performance can be compared consistently and accurately. It would also address CSA concerns that the annual discipline report does not fully and consistently provide information about the disciplinary system.

Key Questions for Legislative Consideration

Should There Be Case Processing Standards for the Entire Disciplinary Process? The Legislature will want to consider whether there should be case processing standards to monitor the entire disciplinary process or simply OCTC. Focusing on the entire system places responsibility on the State Bar to ensure that OCTC and SBC coordinate effectively with one another. It also provides OCTC with an incentive to comprehensively consider the efficacy and efficiency of actions throughout the disciplinary process. Finally, standards for the entire system would also enable the Legislature to identify whether operational or procedural changes or additional resources are needed by SBC to effectively resolve discipline cases in their entirety—arguably what members of the public would be most concerned about.

Are Greater Differentiations in the Case Processing Standards Needed? In additional to risk and complexity, the Legislature may want to consider whether additional factors should be considered in the establishment of new case processing standards. This would help ensure that disciplinary workload is measured against appropriate benchmarks. For example, the Legislature could have cases that are closed or filed at the Charging Stage incorporate risk as well. The Legislature could also have separate standards for certain types of cases to be prioritized (such as complaints related to client trust funds) or “repeater” cases where there are numerous prior or current complaints against the same attorney.

Are Changes to OCTC’s Organization and Operation Needed? The Legislature will also want to consider whether changes to OCTC’s current organization and operation are warranted. This is because how OCTC is structured impacts how effectively and efficiently it operates. For example, the Legislature could prefer more specialized trial teams based on case type or approach (such as more expeditor teams) or the use of horizontal prosecution in certain case types or at certain stages of the disciplinary process. Specialized teams or specializing in particular tasks through the use of horizontal prosecution focuses staff work in particular areas which could result in the processing of cases more efficiently and effectively as staff would be more familiar with how to investigate (such as what evidence is needed and how to obtain that evidence) and prosecute such cases.

How Aggressive Should Case Processing Standards Be? The Legislature will want to consider how aggressive case processing standards should be. More aggressive standards will either require a greater increase in resources or more significant operational and/or procedural changes. We note that State Bar staff indicated in focus groups that the State Bar’s proposed case processing standards were only achievable if staff caseload was generally lower than existing caseload levels.

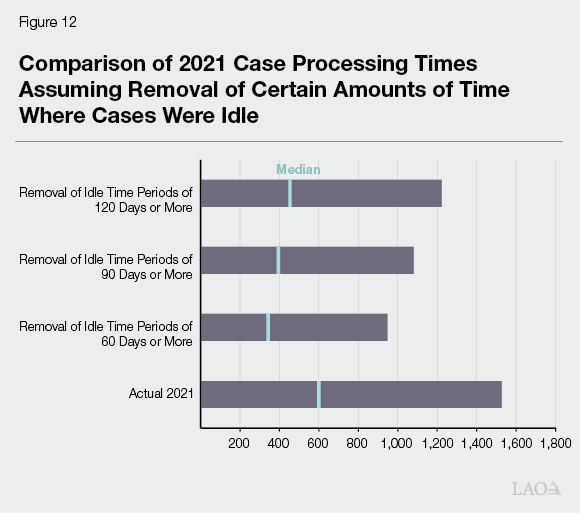

At the same time, if the standards are unreasonable (or even unachievable), the quality of investigations and the severity of discipline obtained may suffer. Accordingly, the Legislature may want to consider adopting less aggressive case processing standards. For example, the State Bar identified that about 26 percent of cases that closed after the Intake Stage or resulted in charges being filed between 2018 to 2021 had time periods of 90 days or more where cases were sitting idle and 16 percent had time periods of 120 days or more where cases were sitting idle. As shown in Figure 12, if the Legislature chooses the same approach as the State Bar in which idle time periods of a certain duration are mathematically removed, selecting one of these less aggressive standards—in which times periods of (1) 90 days or more or (2) 120 days or more, respectively, are mathematically removed—would still likely result in improved case processing times but reduce the likelihood that necessary investigatory or charging time is eliminated.

What Data and Metrics Are Needed to Conduct Legislative Oversight? The Legislature will want to consider what specific data and metrics should be required by state law in the annual discipline report to enable effective legislative oversight. The State Bar completed implementation of a new case management system in 2019 that captures more case processing information. As such, more data is potentially available for reporting. In developing such metrics, the Legislature will want to consider what level of detail is necessary to comprehensively and accurately assess disciplinary workload and processing. For example, the Legislature could include some of the statutory reporting requirements related to DCA licensing cases referred to DOJ for prosecution. Additionally, the Legislature could place requirements on the State Bar to ensure that data is being pulled and reported consistently and accurately from year to year. Clearly specifying specific data and metrics, as well as other requirements (such as requiring descriptions of any changes in methodology in pulling and reporting data or prohibiting such changes without legislative approval) will ensure the State Bar consistently and accurately reports the information desired by the Legislature. Such metrics would help the Legislature to conduct meaningful and consistent oversight of the disciplinary process, hold the State Bar accountable for its performance, and identify potential areas of improvement or concern.

Establishment of Backlog Goal and Metrics to Measure Such Goal

Assessment

Alternative Definition of “Small Backlog” Could Also Be Reasonable. The State Bar proposes that a small backlog of cases should constitute 10 percent or fewer cases. This was generally selected as a statistical indicator of outliers—cases that take significantly more time to process than other cases. It would be equally reasonable to select a different percentage. For example, it could be reasonable to define a small backlog as 15 percent or fewer cases. As noted above, in 2021‑22, 14 percent of total closed cases did not meet the statutory time frames to dismiss a case, admonish an attorney, or file formal charges against an attorney within 180 days for noncomplex cases and 365 days for complex cases.

Proposed Standard Effectively Sets an Upper Limit Goal for Processing Cases. The State Bar’s proposed case processing standards are based on averages, which means that there are cases that will take both more and less time. In order to ensure that only 10 percent or fewer cases in each case category exceed the proposed backlog standards, the State Bar expects 90 percent of cases closed or filed in the SBC will not exceed these proposed standards—meaning a certain number of cases are expected to exceed these standards. As such, the proposed standards effectively set an upper limit goal for processing cases. For example, the State Bar proposes an average case processing standard of 120 days for high‑risk, noncomplex cases closed in the Investigation Stage and a backlog standard of 180 days. This means that nearly all such cases should aim for closure in under 180 days. Such an upper bound can help limit the number of cases that could otherwise drag on without valid reasons.

Backlog Metrics Tend to Measure Pending, Rather Than Closed, Workload. Our understanding is that backlog metrics tend to measure pending workload in order to provide administrators, policymakers, and others with timely information on when workload is outstanding and/or not able to be completed in a timely manner. For example, state law prior to 2021 generally defined annual backlog as cases that were pending—meaning that OCTC did not dismiss a complaint, admonish an attorney, or file formal charges against an attorney—six months after complaint receipt as of December 31 of the preceding year. State law required reporting on this backlog, including the age of the cases in the backlog. By focusing on pending workload, such metrics provide a sense of how much work has not been started or remains unaddressed (such as due to long gaps between case processing events).

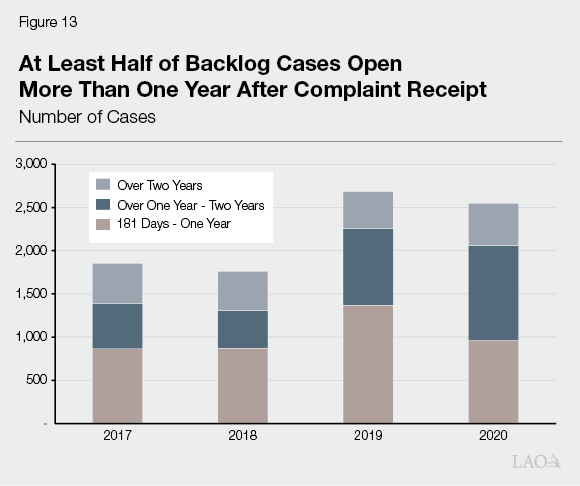

In contrast, the proposed backlog time standards are based on closed workload. This means that cases that remain open, for whatever reasons, will not be captured. For example, a case that remains open in the Investigation Stage for over a year—such as due to a lack of staff to investigate the case or because the investigation is complicated and lengthy—would not be reflected as backlog. Such a case would only be reflected under the proposed standards once it was closed after Investigation or in Charging, or if charges were filed—which could be some time in the future. As shown in Figure 13, backlog data reported in 2020 under the prior state definition demonstrates that at least half of cases remained open longer than one year after complaint receipt. About 20 percent to 25 percent of cases remained open for more than two years—including some that were pending for more than five years. Measuring pending workload helps ensure that all cases are being captured and monitored in real time. This provides administrators, policymakers, and others with the ability to conduct effective and timely oversight.