LAO Contact

January 5, 2023

Promoting Equity in the

Parole Hearing Process

- Introduction

- Background on Parole Hearings

- Aspects of Parole Hearing Process Could Lead to Inequitable Outcomes

- Recommendations to Promote Equity in the Parole Hearing Process

- Conclusion

- Appendix: Selected References

Executive Summary

Parole Hearings Determine if People Can Be Released From Prison Based on Risk

The purpose of the state’s parole hearing process is to decide if eligible people (referred to as parole candidates) can be released from state prison based on a determination of whether they pose an unreasonable risk to the public. Parole hearings are conducted by commissioners who work for the Board of Parole Hearings (BPH). Statute gives parole candidates the right to an attorney at parole hearings. BPH appoints and pays for an attorney for candidates who do not retain a private attorney.

Aspects of Parole Hearing Process Could Lead to Inequitable Outcomes

Potential Bias From Overly Broad Discretion. We find that the parole hearing process affords BPH commissioners and other key actors in the process overly broad discretion. This level of discretion could result in biased decisions in various ways. For example, a large body of research has found that people can exhibit implicit bias, meaning they tend to unconsciously associate certain groups of people with specific attributes. To the extent that implicit bias affects key actors’ thinking in the parole hearing process, candidates who are subject to negative implicit biases would be disproportionately disadvantaged in the process. Moreover, we find that the current process does not adequately provide safeguards on the use of discretion. Specifically, BPH does not publish data on hearing outcomes disaggregated by candidate subgroups, such as race or ethnicity. In addition, there is no regular external monitoring of the extent to which there are differences in release rates between groups that are likely the result of bias.

Potentially Inequitable Access to Effective Legal and Hearing Preparation Services. Available data raise concerns that candidates who rely on state‑appointed attorneys have worse hearing outcomes and may be receiving less effective legal and other hearing preparation services relative to candidates who are able to access a private attorney. This means that two candidates who are otherwise identical might have different hearing outcomes based on their ability to access a private attorney. While the state has recently taken steps to improve state‑appointed attorney effectiveness and candidate access to hearing preparation services, it is currently unclear whether these steps are sufficient due to lack of data and evaluation.

Recommendations to Promote Equity in the Parole Hearing Process

Consider Reducing Commissioner Discretion and Add Key Safeguards. Currently, commissioners can deny parole if they can point to any evidence—even if based on subjective determination—that a candidate may pose a current risk of dangerousness. We recommend that the Legislature consider changing statute to reduce this discretion somewhat, such as by increasing the standard that commissioners must meet to deny parole. In addition, we recommend that the Legislature require BPH to release public data on outcomes by subgroups as well as support periodic quantitative and qualitative studies of the parole process by independent researchers.

Ensure Consistent Access to Effective Legal and Hearing Preparation Services. We recommend that the Legislature first assess the impact of recent changes intended to improve access to and effectiveness of legal and hearing preparation services. We further recommend using the results of this assessment to inform whether future legislative action is needed. Finally, we provide various options that the Legislature could consider if the assessment does not reveal adequate improvements, such as shifting responsibility for providing attorneys to an external entity.

Introduction

While in state prison, certain people become eligible for possible release onto supervision in the community. The purpose of the state’s parole hearing process is to decide if these people can be released—based on a determination of whether they pose an unreasonable risk to the public. For about 40 percent of people held in California’s prison system, the amount of time they ultimately serve in prison—in many cases including whether or not they will spend the rest of their lives in prison—is determined through the parole hearing process. (The remaining portion are generally released automatically from state prison onto supervision in the community.) Accordingly, decisions made in the parole hearing process have major implications for the lives of a significant portion of the state prison population and their loved ones, as well as victims and the safety of the general public. In addition, by determining when people are released from prison, parole decisions impact the size of the prison population and, in turn, state correctional costs.

In this report, we (1) provide background on California’s parole hearing process, (2) review the process and identify current aspects of the process that could disadvantage certain groups, and (3) recommend steps to promote equity in the parole hearing process. In preparing this report, we consulted with leaders who oversee the parole hearing process, attorneys who represent people who receive parole hearings, researchers, and other stakeholders. We also analyzed data on outcomes of state parole hearings. Finally, we reviewed various research studies on parole in California and other states and observed parole hearings.

Background on Parole Hearings

Overview of Board of Parole Hearings

The Board of Parole Hearings (BPH) within the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) is composed of 21 commissioners who are appointed by the Governor and subject to confirmation by the Senate. Statute specifies that these appointed commissioners should reflect, as nearly as possible, a cross section of the racial, sexual orientation, gender identity, economic, and geographic features of the population of the state. Appointed commissioners work with civil service deputy commissioners (who are hired by BPH rather than appointed by the Governor) to administer parole hearings. (For the purposes of this report, we refer to both appointed commissioners and deputy commissioners collectively as commissioners.) The purpose of parole hearings is to decide whether to release certain people (referred to in this report as “parole candidates”) from state prison. Statute specifies that commissioners should have broad backgrounds in criminal justice with varied professional and educational experience in fields such as corrections, sociology, law, law enforcement, health care, or education. While not the focus of this report, we note that BPH has various other responsibilities, such as advising the Governor on applications for clemency.

Eligibility for Parole Hearings

Depending on their crime and criminal history, people in prison have one of four types of sentences: (1) death, (2) life without the possibility of parole (LWOP), (3) indeterminate, and (4) determinate. As of November 2022, CDCR was incarcerating a total of roughly 96,000 people. This includes about 700 people (1 percent) sentenced to death; 5,100 (5 percent) sentenced to LWOP; 31,000 (32 percent) with indeterminate sentences; and 59,000 (62 percent) with determinate sentences. People with death sentences are not eligible for parole hearings. People with the other three types of sentences may be eligible for parole hearings for various reasons, as discussed below.

People With Indeterminate Sentences. People with indeterminate sentences—typically given for severe crimes such as murder—have a prison term that includes a minimum number of years but no specific maximum, such as “30‑years‑to‑life.” They can only be released from prison if found suitable for release through a parole hearing. All people with indeterminate sentences are eligible for parole hearings once they serve the minimum term in their sentences. However, three types of indeterminately sentenced people could become eligible to begin receiving parole hearings earlier. Specifically, people who:

- Were Under Age 26 When Committing Their Crime. These people generally become eligible for parole hearings after serving 25 years in prison. These parole hearings are called youth offender hearings and can lessen the sentences of people who committed crimes while, according to research, their brains were still developing. As we discuss further below, youth offender parole hearings are slightly different from standard parole hearings as they involve consideration of certain factors related to candidates’ growth in maturity. As of November 2022, about 5,800 (19 percent) of those with indeterminate sentences are receiving or are expected to receive parole hearings earlier than otherwise because they qualify for youth offender hearings.

- Served More Than 20 Years in Prison and Are Age 50 or Over. These people are generally eligible for hearings called elderly parole hearings, which can lessen the sentences of people whose age, according to research, makes them less likely to commit additional crimes. As we discuss below, elderly parole hearings are also slightly different from standard parole hearings in that they involve consideration of certain factors related to candidates’ advanced age. About 10,000 (33 percent) of those with indeterminate sentences are receiving or are expected to receive parole hearings earlier than otherwise because they qualify for elderly parole hearings.

- Were Not Convicted of a Violent Crime. These people can become eligible for parole hearings before serving the minimum term in their sentence. The precise amount of time they must serve before this hearing depends on what crimes they were convicted of. This primarily applies to people who received indeterminate sentences for nonviolent felonies under the state’s Three Strikes Law. (For more on the Three Strikes Law, see the box below.) About 2,700 (9 percent) of those with indeterminate sentences are receiving or are expected to receive parole hearings earlier than otherwise because they were not convicted of a violent crime.

Three Strikes Law

In 1994, the California Legislature and voters (with the passage of Proposition 184) changed felony sentencing law to impose longer prison sentences on people who have certain prior felony convictions (commonly referred to as the Three Strikes Law). Specifically, a person who is convicted of a felony and who previously has been convicted of one or more specific felonies classified as “violent” or “serious” is currently sentenced as follows:

- Second Strike Offense. If the person has one previous serious or violent felony conviction, the sentence for any new felony conviction (not just a serious or violent felony) is twice the term otherwise required under law for the new conviction. People who receive this sentencing enhancement are referred to as “second strikers.”

- Third Strike Offense. If the person has two or more previous serious or violent felony convictions, the sentence for any new serious or violent felony conviction is a minimum sentence of 25‑years‑to‑life in prison. In addition, people with two or more previous serious or violent convictions who commit a new nonserious, nonviolent felony can be similarly sentenced to a life term if (1) the new felony is a certain offense (such as selling large quantities of illegal drugs) or (2) the person’s prior offenses included certain crimes (such as homicide or certain severe sex crimes). People who receive the above sentencing enhancements are referred to as “third strikers.”

As of September 2022, there were about 21,900 second strikers and 5,700 third strikers in state prison. While state law requires the sentences described above, courts can, under certain circumstances, choose not to consider prior felonies during sentencing—resulting in shorter prison sentences than required under the Three Strikes Law.

If they are released from prison, people with indeterminate sentences are supervised in the community by state parole agents.

People Previously Sentenced as Minors to LWOP. People can be sentenced to LWOP for certain severe crimes, such as murder involving torture. People with LWOP sentences are not eligible for parole hearings, with the exception of those who received an LWOP sentence for a crime they committed while under 18 years of age. This is due to U.S. Supreme Court rulings in 2012 and 2016, which prohibited LWOP sentences for such people and required that those who had previously received them be given a meaningful opportunity for release. Accordingly, such people are eligible for youth offender parole hearings after serving 25 years in prison. About 200 (4 percent) of those sentenced to LWOP are receiving or expected to receive youth offender parole hearings because they committed their crime before the age of 18. If released from prison, these people are supervised in the community by state parole agents.

Certain People With Determinate Sentences. Most people in prison have determinate sentences. People with determinate sentences are sentenced to a fixed number of years in prison and are released after serving that time. However, they can become eligible for parole hearings to potentially be released earlier. This can occur in two ways. First, people with determinate sentences who were under the age of 26 when they committed their crime are generally eligible to begin receiving youth offender parole hearings after serving 15 years in prison. About 4,400 (7 percent) of those with determinate sentences are eligible for possible release earlier than otherwise through youth offender parole hearings. Second, people with determinate sentences who are age 50 or over and have served at least 20 years in prison can generally become eligible to begin receiving elderly parole hearings. About 2,000 (3 percent) of those with determinate sentences are eligible for possible release earlier than otherwise through elderly parole hearings. Regardless of whether they are released after completing their entire sentence or earlier by BPH, people with determinate sentences are supervised in the community for a period of time by either state parole agents or county probation officers, depending on the crime they committed.

Key Decisions Made in Parole Hearings

At each parole hearing, BPH commissioners must decide whether the parole candidate would pose an unreasonable risk of danger if released from prison. If the candidate is not released, the commissioners must then decide when the candidate’s next parole hearing should occur.

Would the Candidate Pose an Unreasonable Risk of Danger if Released? In deciding whether candidates are suitable for release, commissioners are guided in large part by case law. In particular, the California Supreme Court has ruled that the central question in determining suitability is whether a candidate would currently pose an unreasonable risk of danger to the public if released. In addition, the court has ruled that a decision to find a candidate unsuitable for release must be based on “some evidence” that the candidate represents an unreasonable risk. As a result, BPH is not permitted to base decisions solely on the heinousness of the crime, the opinions of victims, or public outcry—unless there is a clear nexus between those factors and candidates’ current dangerousness.

To assist commissioners in this decision, BPH regulations outline factors that tend to show suitability for release (such as signs of remorse) and factors that tend to show unreasonable risk to the public (such as in‑prison misconduct). However, in youth offender parole hearings, statute requires commissioners to give great weight to the diminished culpability of juveniles as compared to adults and any subsequent growth and increased maturity of candidates. Similarly, in elderly parole hearings, statute requires commissioners to give special consideration to candidates’ advanced age, long‑term confinement, and potentially diminished physical condition.

If Not Released, When Should Candidate’s Next Hearing Occur? When commissioners find a candidate unsuitable for release, state law requires them to set the date for the candidate’s next hearing. Specifically, commissioners are required to set the next hearing 3, 5, 7, 10, or 15 years in the future based on evidence supporting the amount of additional incarceration needed to protect the safety of the public and the victim. The number of years until a candidate’s next parole hearing is often referred to as the “denial period.”

Key Steps in Parole Hearing Process

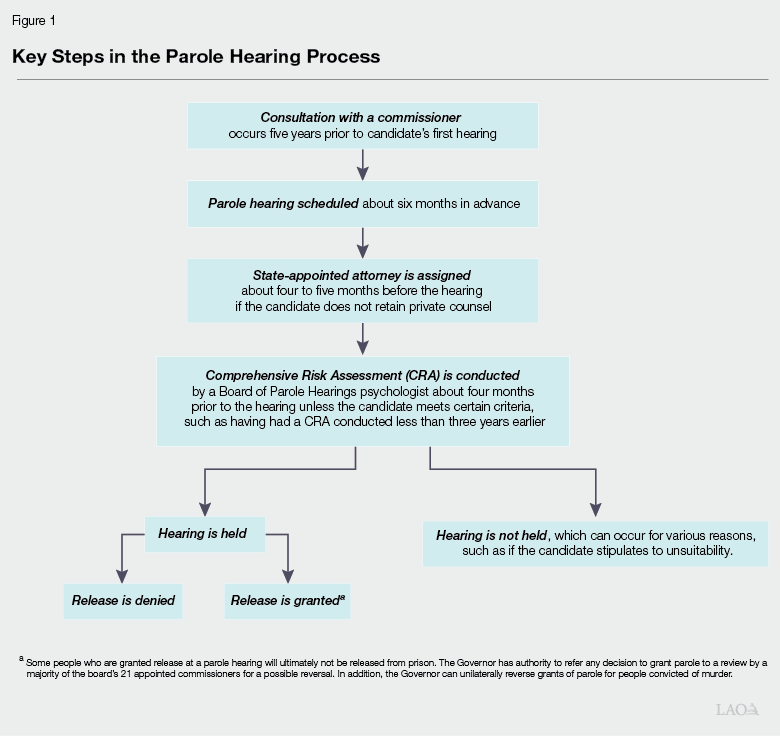

As shown in Figure 1 and described below, there are several key steps in the parole hearing process.

Consultation With Parole Commissioner. Five years prior to a parole candidate’s first parole hearing, a commissioner consults one‑on‑one with the candidate to explain the process and legal factors relevant to suitability. Commissioners also provide recommendations to candidates on how they can increase their chances of being found suitable for release, such as by following prison rules and participating in certain rehabilitation programs and work assignments. In 2021, commissioners conducted 2,158 consultations.

Scheduling of Hearing. About six months prior to when a candidate is expected to receive a hearing, BPH staff schedule the hearing for a particular week. There were 8,722 parole hearings scheduled to occur in 2021.

Assignment of Legal Counsel. Statue gives parole candidates the right to an attorney at parole hearings. About four to five months before their hearing, BPH appoints an attorney for candidates who do not hire a private attorney or receive free services from a private attorney. Private attorneys that provide free services are often affiliated with nonprofit organizations specializing in parole hearings. We note that 7,697 (about 90 percent) candidates who had parole hearings scheduled to take place in 2021 relied on a state‑appointed attorney.

State‑appointed attorneys are required to provide basic legal services to their clients. These tend to include ensuring that candidates’ procedural rights are protected, objecting to factual errors or legal issues, and making a closing statement during the hearing to argue why candidates are suitable for parole. In doing so, they are required to complete certain activities, such as reviewing records about their clients and meeting with their clients prior to the hearing.

In addition to the basic legal services that state‑appointed attorneys are required to provide, private attorneys typically provide additional legal services. For example, in some cases, private attorneys hire external consultants to provide expert opinions, such as on their clients’ risk level. Private attorneys also tend to provide hearing preparation services focused on helping their clients demonstrate suitability to the board. For example, they may advise clients on writing letters of remorse to their victims, preparing relapse prevention plans, and gathering letters of support (such as from family members or prospective employers). These hearing preparation services can involve guiding clients through a process of introspection with the goal of building insight into the causes of their behavior, understanding the role of trauma in their lives, and taking accountability for their actions. Finally, whereas the services of state‑appointed attorneys end after hearings conclude, private attorneys often continue working for their clients between hearings if they are denied release. For example, private attorneys may review the hearing transcript to ensure that any errors are corrected as well as meet with their clients to debrief and discuss next steps to prepare for the subsequent hearing.

Risk Assessment by BPH Psychologist. About four months before their hearing, candidates are generally interviewed by a BPH psychologist to assess their long‑term potential for future violence as well as factors that could minimize their risk of violence if released. Through this assessment—called the Comprehensive Risk Assessment (CRA)—psychologists classify a candidate as having low, moderate, or high risk of violence. (The CRA is not administered in certain cases, such as if the candidate has had a CRA conducted less than three years prior.) Currently, in implementing the CRA, BPH psychologists primarily rely on a tool called the Historical Clinical Risk Management‑20, Version 3 (HCR‑20V3). This tool guides psychologists in evaluating various factors—such as substance use or violent attitudes—that research has found are associated with risk of violence. Psychologists then combine the result of the HCR‑20V3 with any other information they find to be relevant and reliable to produce a single CRA risk level for each candidate. All completed CRAs are reviewed by senior BPH psychologists. In 2021, BPH psychologists completed 4,428 CRAs.

Voluntary Waiver of Hearing or Stipulation to Unsuitability. No later than 45 days before their parole hearing, candidates may choose to waive their right to a hearing for one to five years. In other words, they can choose to essentially delay their parole hearing. Alternatively, candidates may stipulate to unsuitability—effectively requesting to be denied parole without a hearing. They may stipulate to being unsuitable for a period of 3, 5, 7, 10, or 15 years. Candidates might strategically choose to waive their hearing or stipulate to unsuitability to achieve a potentially shorter amount of time until their next hearing, relative to the denial period that they could get if they choose to receive a hearing. Of the 8,722 hearings that were scheduled to occur in 2021, candidates waived their hearing in 1,758 (20 percent) cases and stipulated to unsuitability in 301 (3 percent) cases. We note that hearings may not occur or be completed as originally scheduled for other reasons, such as a candidate being sick on the day of the hearing. Specifically, 2,146 (25 percent) hearings originally scheduled to occur in 2021 were postponed to later in 2021 or 2022. In addition, 328 (4 percent) were continued (meaning that the hearing was started but could not be completed for some reason) or cancelled.

Parole Hearing. As previously mentioned, parole hearings are typically conducted by two commissioners (one appointed commissioner and one deputy commissioner). During hearings, commissioners ask candidates questions about their social history, past and present mental state, past and present attitude toward their crime, and plans for work and housing if they are released. Since 2019, commissioners have used a Structured Decision‑Making Framework (SDMF) that is intended to help focus their questions to candidates on factors found in research to be most associated with risk of violence, such as candidates’ risk level as determined by the BPH psychologists and their participation in rehabilitation programs. Victims or their representatives, as well as prosecutors from the county that committed the candidate to prison, may choose to attend and speak at the parole hearing. The hearing concludes when the commissioners issue their decision regarding the candidate’s suitability for release. (We provide information in the box below on how parole processes vary across other states and the federal government.)

How Does California’s Parole Hearing Process Compare to Other Jurisdictions?

Processes in Other Jurisdictions Can Differ. There is substantial variability in how discretionary release processes—like California’s parole hearing process—are structured and operate. For example, a 2015 survey of state parole boards and the U.S. Parole Commission (which makes release decisions about federal prisoners) found that while a majority of parole boards reported incorporating some form of risk assessment into their decision‑making process, there was substantial variation between jurisdictions in the specific assessments used. In addition, about half of the boards in other jurisdictions reported using some kind of decision‑making tool like the Board of Parole Hearings’ Structured Decision‑Making Framework. While nearly two‑thirds of respondents reported allowing candidates’ attorneys to attend hearings, only about one‑quarter reported that indigent candidates are provided with attorneys at state expense.

Differences in Processes Can Stem From Variation in Sentencing Frameworks. While differences in parole hearing processes can be caused by various factors, one significant factor is the variation in sentencing frameworks across jurisdictions. As discussed earlier in this report, sentencing frameworks are often characterized as either determinate or indeterminate. Accordingly, the number and types of crimes subject to indeterminate sentencing in each jurisdiction are primary factors in determining the number of people who need a parole hearing to be released. In the 2015 survey, 26 percent of jurisdictions reported that they had a determinate system, 29 percent reported that they had an indeterminate system, and 45 percent—including California—reported having elements of both.

In 2021, of the 4,188 hearings held, 1,424 (34 percent) resulted in a decision to grant release and 2,764 (66 percent) resulted in a denial. (The percentage of hearings held that resulted in a decision to grant release has remained relatively consistent in recent years.) Decisions are later reviewed by BPH’s chief counsel for errors of law or fact. If the commissioners do not agree on a decision, cases are referred to a review by a majority of the board’s 21 appointed commissioners.

Governor’s Review. The Governor has statutory authority to refer any decision to grant parole to a review by a majority of the board’s 21 appointed commissioners for a possible reversal. In addition, since 1988, the Governor has had constitutional authority to unilaterally reverse grants of parole for people convicted of murder. Case law requires that the Governor’s decision to reverse a grant of parole be based on some evidence that the candidate would pose an unreasonable risk to the public. (The State Constitution also gives the Governor power to grant reprieves, commutations, and pardons for people convicted of crimes, though these are not the subject of this report.)

Aspects of Parole Hearing Process

Could Lead to Inequitable Outcomes

In our review of California’s parole hearing process, we identified two aspects of the process that could lead to inequitable outcomes. First, we find that there is overly broad discretion exercised by BPH commissioners and other key actors in the process, which could result in biased decisions. This is particularly concerning given the lack of certain key safeguards in the process on the use of this discretion. Second, we find that there is potentially inequitable access to effective legal and hearing preparation services for parole candidates. While some steps have recently been taken to address this problem, it is unclear whether these steps are sufficient.

While the primary focus of this report is equity, the concerns we discuss below could have implications beyond inequitable outcomes. For example, to the extent that the parole hearing process could inequitably disadvantage certain candidates, it would mean that the state is paying to continue to incarcerate them without a public safety need to do so. Conversely, to the extent that some inequities could work in favor of certain candidates, it would mean that BPH is releasing them despite the potentially high risk they represent to public safety.

Potential Bias From Overly Broad Discretion

Process Affords Significant Discretion to Key Actors

Discretion Afforded to Parole Commissioners. As noted above, since 2019, BPH has instructed commissioners to use the SDMF to guide their decision‑making process during parole hearings. This may have improved consistency of decision‑making and narrowed commissioner discretion somewhat, though the SDMF has not been formally evaluated. However, even with the implementation of the SDMF, we find that commissioners still retain significant discretion for three key reasons. First, some of the factors included in the SDMF—such as the amount by which candidates have changed since they committed their crimes—are inherently subjective. Second, commissioners can consider factors that are not explicitly included in the SDMF, such as whether and how the candidate expresses remorse about the crime. Third, commissioners retain full discretion in how to weight the various factors that they choose to consider to produce a decision on whether to grant release. In other words, even if most information suggests that a candidate is not dangerous, as long as one piece of information provides some evidence of possible of dangerousness, commissioners have the discretion to deny release.

Discretion Afforded to Other Key Actors. In addition to parole commissioners, various other actors in the parole hearing process maintain substantial discretion. This includes the BPH psychologists who assign a single CRA risk level to each candidate—low, moderate, or high violence risk. As noted above, this classification is largely based on the results of the HCR‑20V3 and any other information that they find to be relevant and reliable. This allows BPH psychologists to exercise substantial discretion in three primary ways. First, some of the individual risk factors in the HCR‑20V3—such as the degree of candidates’ insight into the causes of their behavior—are inherently subjective. Second, psychologists have flexibility in how to weigh the various factors in the HCR‑20V3 to produce a single risk level. Third, they have discretion in terms of whether and how to incorporate information outside of the HCR‑20V3 to produce a risk level.

We also find that the Governor has significant discretion in being able to unilaterally overturn commissioners’ decisions for candidates convicted of murder. While the Governor is limited to considering the same factors that the commissioners considered in determining suitability, the Governor has virtually no restrictions with respect to how factors are weighted or the process by which decisions are made. We note that different Governors often take dramatically different approaches to reviewing BPH decisions. For example, in 2003, Governor Davis reversed about 95 percent of parole decisions in murder cases, while Governor Brown reversed about 14 percent in 2015.

Current Level of Discretion Could Allow Biases to Affect Parole Decisions

On the one hand, discretion allows decision makers to interpret information in a more nuanced way than a formulaic approach. For example, a BPH commissioner could assess the details of a disciplinary infraction and conclude that the issue should be disregarded as it was due to unique circumstances in prison unrelated to how the candidate would behave if released. On the other hand, discretion allows decisions to be influenced by the idiosyncrasies, values, or conscious or unconscious biases of decision makers. This creates the potential for decisions to be arbitrary or biased. Below, we discuss certain types of bias that could be affecting decisions made in the parole hearing process given the overly broad discretion currently provided.

Potential Cognitive Biases of Key Actors. Psychologists have identified various common, systematic errors in thinking that tend to arise when people are processing and interpreting information in the world around them. These errors—referred to generally as cognitive biases—often operate without people’s awareness or conscious control and can reduce the accuracy of decisions and judgements. The wide discretion afforded to key actors in the parole hearing process creates the potential for cognitive biases to affect their decisions. Below, we discuss two examples of such cognitive biases—implicit bias and the fundamental attribution error—and how they could impact the parole hearing process.

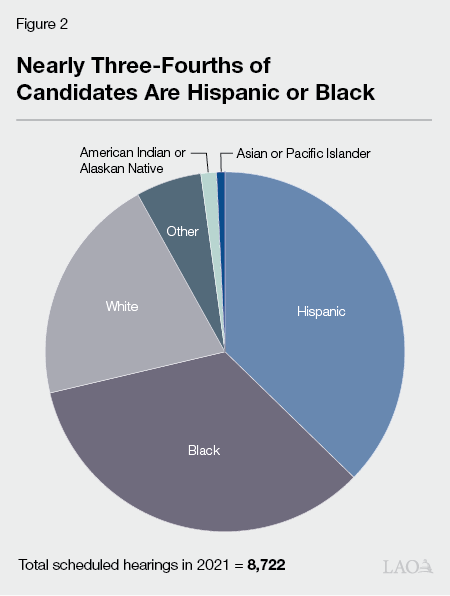

A large body of research has found that people tend to unconsciously associate certain groups of people with specific attributes. These associations tend to be based on stereotypes—generalized beliefs about a particular group of people, which can be acquired through social influences, media, or personal experiences. This is referred to as implicit bias. For example, research done on a diverse, national sample of jury‑eligible adults, found that they significantly associated Latino and Black men with danger and white men with safety. This is notable given that CDCR data indicate almost three‑fourths of people who receive parole hearings are Hispanic or Black, as shown in Figure 2. To the extent that implicit bias affects key actors’ thinking in the parole hearing process, candidates who are subject to negative implicit biases (such as Black and Latino men) would be disproportionately disadvantaged in the parole hearing process. Similarly, it could mean that parole candidates who are unconsciously associated with positive attributes are being released from prison at a higher rate than justified by their assessed level of risk.

Psychologists have also found that in assessing the reasons behind others’ behavior, people tend to over‑emphasize dispositional, or personality‑based, explanations while under‑emphasizing situational explanations. This is known as the fundamental attribution error. Consistent with this psychological finding, researchers who interviewed a sample of BPH commissioners between 2011 and 2013, found that commissioners tended to attribute candidates’ crime or subsequent behavior to internal character flaws. When candidates indicated that situational factors contributed to their behavior, commissioners tended to interpret this as a sign that candidates were making excuses for their behavior and lacking in true remorse, which can lead to a denial of parole. To the extent it is caused by the fundamental attribution error, this commissioner tendency could disadvantage candidates who truly have been impacted by situational factors, such as trauma. For example, transgender people tend to face a high risk of victimization in prison. This can lead them into fighting to defend themselves from those victimizing them, which can be interpreted and recorded by prison staff as misconduct. Accordingly, candidates may see their behavior as a situational response to the failure of the prison system to protect them from violence. In contrast, to the extent that the fundamental attribution error causes commissioners to under‑weight situational explanations, commissioners may see the behavior as misconduct and interpret candidates’ attitudes toward it as an indicator that they lack remorse and deny them release, even if this is not warranted based on their risk. Likewise, candidates who do not point to situational factors (such as a history of trauma, victimization, or mistreatment as a partial cause of their behavior) could be more likely to be found genuinely remorseful by decision makers and released even if they have similar risk levels to people who are not released.

Potential Institutional Biases of Key Actors. It is possible that key actors may be influenced by their institutional context. For example, it is possible that appointed commissioners either consciously or subconsciously are influenced by what they believe are the values of the Governor, knowing that they will eventually need to be reappointed by the Governor in order to continue to serve on the board. To the extent commissioners are affected by this bias, this could lead them to deny or grant parole to candidates based on factors they believe are important to the Governor even if they are not based on candidates’ actual risk of violence. In addition, to the extent BPH psychologists view the board as being inclined or disinclined to release candidates, this could affect how they administer the CRA. We note research on other criminal justice risk assessments that, like the CRA, involve substantial subjectivity has found that administering psychologists tend to assign higher risk scores if they believe they are working for the prosecution as opposed to the defense in a given case.

Process Lacks Key Safeguards on the Use of Discretion

Given the current level of discretion in the parole hearing process, it is important to have safeguards in place that can mitigate the impacts of possible biases in release decisions. BPH currently maintains some safeguards on the use of discretion. For example, as previously mentioned, all CRAs must be reviewed by a senior psychologist, which, in turn, likely promotes consistency in the assessment of a candidate’s risk of violence. In addition, BPH provides commissioners with training on various topics, such as implicit bias. While these practices likely promote quality and consistency in parole decision‑making, as well as seek to limit the potential for bias, we find that the current process does not adequately provide safeguards on the use of discretion. Specifically, BPH does not publish data on the outcomes of scheduled hearings (including grants, denials, waivers, and stipulations) disaggregated by candidate subgroups, such as race or ethnicity. Having such data would help the Legislature and stakeholders monitor the parole process and ensure that the discretion provided does not result in different subgroups being treated differently. In addition, while there have been a few limited studies done at the discretion of external researchers, there is no regular external monitoring of the extent to which there are differences in release rates between groups that are likely the result of bias in the parole hearing process.

Potentially Inequitable Access to Effective Legal and Hearing Preparation Services

Data Raise Concerns About Attorney Effectiveness and Lack of Hearing Preparation Services

Candidates With State Appointed Attorneys Have Worse Outcomes. Available data indicate that candidates who rely on state‑appointed attorneys are (1) less likely to be granted parole and (2) when not granted parole, wait a longer time until their next parole hearing, as compared to candidates who have private attorneys. Specifically, of the parole hearings that were scheduled to occur in 2021, candidates who were represented by state‑appointed attorneys were granted parole at around half the rate of those represented by private attorneys. Of those who were denied parole, candidates with state‑appointed attorneys received denial periods that were six months (15 percent) longer on average than candidates with private attorneys. In addition, candidates with state‑appointed attorneys were more than twice as likely to waive their right to a parole hearing and four times as likely to stipulate to unsuitability, compared to candidates with private attorneys. Of those who chose to waive their parole hearing, candidates with state‑appointed attorneys waived their hearings for an average of three months longer (30 percent) than those with private attorneys. (For those who stipulated to unsuitability, denial periods were comparable between candidates with state appointed and those with private attorneys.)

Potentially Due to Lower Level of Legal and Hearing Preparation Services Received From State‑Appointed Attorneys. It is possible that some of the above disparities are driven by actual differences in risk of violence between the two groups. For example, candidates with a better chance of release may be more willing to pay for an attorney. However, a 2020‑21 survey of parole candidates suggests that state‑appointed attorneys may not be meeting the minimum expectations for legal services. Specifically, only about 8 percent of survey respondents confirmed that their state‑appointed attorney had met all of the minimum expectations outlined in BPH policies, such as meeting with the candidate at least once for 1 to 2 hours within 30 days of being appointed. In addition, the survey data suggest that many state‑appointed attorneys might not be providing basic forms of assistance to their clients. For example, while candidates have an opportunity to give a closing statement in hearings, only 27 percent of survey respondents reported that their state‑appointed attorney had discussed this closing statement with them prior to the hearing. (While a comparable statistic on private attorneys was not available, we understand it to be a common practice for private attorneys to talk with their clients about the closing statement.)

As discussed above, in addition to providing basic legal services, private attorneys sometimes provide more extensive services. For example, private attorneys sometimes hire an external consultant, such as a psychologist, to provide an expert opinion on a factor relevant to their clients’ risk. In addition, private attorneys tend to provide hearing preparation services, such as helping clients prepare relapse prevention plans. Private attorneys also tend to work with their clients over longer periods of time—including between parole hearings—rather than just the four months leading up to a hearing. Accordingly, it is possible that some of the difference in outcomes between state‑appointed and private attorneys could be driven by the fact that private attorneys simply provide more extensive legal and hearing preparation services.

Inequitable Access to Private Attorneys. To the extent that state‑appointed attorneys provide less effective legal and/or fewer hearing preparation services to candidates, it raises an equity concern. This is because it would mean that two candidates who are otherwise identical might have different hearing outcomes based on their (or their families’) ability to either afford a private attorney or access a private attorney free of charge, such as through a nonprofit organization. This could create inequities for a variety of different groups, including parole candidates who are impoverished and those who lack the mental capacity or language skills necessary to secure an attorney free of charge.

Reinforcement of Other Biases in the Process. Without competent and zealous advocacy and/or hearing preparation services, candidates may be more vulnerable to the potential disadvantages discussed above. For example, a competent and zealous attorney serving a transgender candidate could counsel them about how to best address commissioners’ questions about their disciplinary history. Without access to these services, such a candidate could be inequitably denied release due to their history of victimization in prison.

Unclear Whether Recent Steps to Improve Attorney Effectiveness and Access to Hearing Preparation Services Are Sufficient

Efforts to Improve State‑Appointed Attorney Services. In 2019, BPH reported difficulty attracting and retaining competent attorneys and indicated that it had to reprimand or even discontinue appointing some attorneys for providing inadequate representation. According to BPH, this was primarily because attorney pay had not kept up with the increasing amount of work that attorneys must do on each case—largely due to more requirements related to documenting a candidate’s disability accommodation needs. The board also indicated that the attorney pay structure was problematic as it discouraged stipulations and waivers of parole hearings even if they were in a candidate’s best interest. This is because attorneys received a relatively significant increase in compensation if a case proceeded to the hearing stage.

In response to the above concerns, the 2019‑20 budget provided BPH with a $2.5 million General Fund augmentation to implement the following changes:

- Increase Attorney Pay From $400 to $750 Per Case and Modify Pay Structure. To help attract and retain better performing attorneys, BPH increased the total compensation per case for state appointed attorneys from $400 to $750 in 2020. To avoid discouraging stipulations and waivers, BPH shifted to a new pay structure under which attorneys receive the full $750 payment regardless of whether the case proceeds to a hearing.

- Increase Training and Mentorship for Attorneys. In 2020, BPH contracted with a nonprofit organization—Parole Justice Works (PJW)—to provide ongoing training and mentorship to state‑appointed attorneys. In addition, PJW staff periodically observe parole hearings to monitor attorney effectiveness and provide feedback to attorneys.

Efforts to Increase Access to Hearing Preparation Services. The 2019‑20 budget provided $4 million from the General Fund on a one‑time basis for UnCommon Law—a nonprofit organization that provides free legal representation to parole candidates—to implement a pilot program to deliver hearing preparation services to candidates separate from the traditional attorney‑client relationship. The program, which is currently being implemented, delivers services through group workshops and individual counseling with the goal of helping participants (1) understand and express how their traumatic experiences contributed to their actions in harming others and (2) develop new thinking patterns and coping skills. Though the program experienced significant implementation delays due to the COVID‑19 pandemic, it is currently serving a cohort of about 30 people at California State Prison Los Angeles County in Lancaster. UnCommon Law is hoping to expand the program to a prison in Northern California sometime in 2023. In addition, it is considering offering a less intensive version of the program—in the form of shorter workshops—at several other prisons. If this program is shown to be successful and can be scaled to serve the entire prison system, it could improve equity in access to hearing preparation services by increasing their availability to people without private attorneys.

Over the past several years, the state has also expanded the availability of programs that generally focus on helping people in prison understand the impact of crime, build empathy, and develop insight into the causes and consequences of their behavior. For example, the 2019‑20 budget provided $5 million ongoing General Fund for the California Reentry and Enrichment grant, through which CDCR funds programs that focus on insight and accountability. These programs engage people in prison through a wide range of modes and topics, including peer‑led discussion groups and the arts. In some cases, programs are explicitly designed to incorporate hearing preparation services. In many other cases, programs do not explicitly focus on parole candidates, yet nevertheless incorporate elements that may help candidates prepare for their parole hearings. For example, programs often attempt to help participants gain insight into the effects of past traumas on their lives, take accountability for their actions, and build healthy coping skills. Accordingly, it is possible that some of these programs are effectively providing hearing preparation services to candidates who would otherwise not have access to them.

Insufficient Data to Determine Whether Attorney Effectiveness Is Improving. While it is possible that some of the above steps may have improved the services provided by state‑appointed attorneys, it is unclear at this time whether they are sufficient. The 2020‑21 survey that raised concerns about state‑appointed attorney effectiveness concluded after BPH began implementing the changes intended to improve service. While this could indicate that the above changes did not sufficiently improve attorney effectiveness, it is unclear if sufficient time had elapsed to allow the impact of the changes to be observed in the survey data. Moreover, no comprehensive data is currently available to fully examine the extent to which the various changes have improved attorney effectiveness.

Unclear if Hearing Preparation Services Are Effective or Accessible. As discussed above, UnCommon Law’s pilot project is currently underway. In 2023, UnCommon Law expects to complete a report on the program’s effectiveness in improving participants’ emotional and physical wellbeing so they are able to engage in the process of preparing for parole and ultimately require less support from their state‑appointed attorneys. However, until the project is completed and evaluated, it is not clear whether the model is effective. Similarly, hearing preparation services that are potentially being provided by other community‑based organizations that have partnered with CDCR have not been evaluated. Finally, even if some of these programs are effective in delivering hearing preparation services, it is unclear whether they have enough capacity to serve all of the parole candidates that need them.

Recommendations to Promote

Equity in the Parole Hearing Process

In view of the above concerns we identified with California’s parole hearing process, we recommend that the Legislature take key steps to promote greater equity in the process. First, to help reduce potential biases, we recommend that the Legislature consider reducing commissioner discretion and add key safeguards on the use of discretion by key actors. Second, to ensure equitable access to effective legal and hearing preparation services for candidates, we recommend that the Legislature assess the impact of recent changes intended to improve their quality and availability. The results of this assessment can then be used to inform potential future legislative action. To the extent the Legislature finds further improvements are needed, we provide various options.

Consider Reducing Commissioner Discretion and Add Key Safeguards

As discussed above, some amount of discretion in the parole hearing process is valuable as it allows decision makers flexibility to accommodate individual circumstances and to interpret nuanced information in ways that pre‑set rules or formula cannot. However, despite its advantages, discretion creates an entry point for bias in decision‑making. On balance, we found that the current process provides overly broad discretion to decision makers. To address this concern, we recommend that the Legislature take a two‑pronged approach by (1) considering limiting the discretion of parole commissioners and (2) creating greater transparency and oversight of how commissioners and other key actors use their discretion.

Consider Limiting Discretion of Parole Commissioners. Currently, commissioners can deny parole if they can point to any evidence—even if based on subjective determination—that a candidate may pose a current risk of dangerousness. We recommend that the Legislature consider changing statute to somewhat reduce commissioners’ discretion to deny parole, particularly based on subjective factors. The Legislature could take various approaches to do so. For example, the Legislature could increase the standard that must be met—which is currently established through case law as some evidence—to “a preponderance of evidence” or “clear and convincing evidence” that a candidate poses a current risk. For example, if the Legislature were to require decisions to be supported by a preponderance of evidence, decisions to deny release would need to be backed by evidence showing that candidates are more likely than not to be an unreasonable risk to public safety. If clear and convincing evidence is required, then decisions to deny release would need to be backed by evidence showing that candidates are substantially more likely to be an unreasonable risk to public safety than not.

Discretion could be limited in all cases or just for those who meet certain criteria, such as having been assessed by BPH psychologists to be low risk or remaining discipline free for five years. If the Legislature chooses to make this change only for low‑risk candidates, we also recommend requiring BPH to report on the numbers of parole candidates assessed as low, moderate, and high risk before and after the change. This would ensure that BPH does not respond to this change by altering how psychologists assesses risk (such as by assessing fewer candidates to be low risk).

Provide Greater Transparency and Oversight of How Commissioners and Other Key Actors Use Their Discretion. We recommend that the Legislature adopt legislation requiring BPH to release public data on CRA, parole hearing, and Governor review outcomes by subgroups, such as race and ethnicity. This data would help the Legislature, BPH, and stakeholders better monitor the parole decision‑making process for any potential disparities. Making such data publicly available would likely create some new costs for BPH, which we estimate to be minor and likely absorbable for the board.

In addition, we recommend that the Legislature support periodic quantitative and qualitative studies by independent researchers of both the CRA and parole hearings. Quantitative analysis should assess whether (1) the CRA and SDMF are being implemented consistently with best practices and between individual psychologists and commissioners and (2) whether certain groups are more or less likely to receive favorable outcomes, even after controlling for relevant factors that legitimately impact outcomes. Qualitative analysis would help reveal the nature of key actors’ interactions with candidates and how key actors are assessing subjective factors, such as remorse. This could give insight into why certain groups might have higher or lower grant rates after controlling for relevant factors as well as how to address such issues.

Ensure Consistent Access to Effective Legal and Hearing Preparation Services

As discussed above, parole process and outcome data raise concerns that candidates who rely on state‑appointed attorneys may be receiving fewer and/or less effective legal and hearing preparation services than those who are able to retain private attorneys. While the state has implemented recent changes in an effort to address these concerns, the lack of ongoing data on the effectiveness and accessibility of legal and hearing preparation services makes it difficult to assess whether the changes have been effective. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature (1) assess the impact of recent changes and (2) use the results of this assessment to guide its future actions. We provide various options it could consider depending on what is found in the assessment.

Assess Impact of Recent Steps to Improve Effectiveness of Legal and Hearing Preparation Services. We recommend that the Legislature require an assessment by an external researcher to (1) evaluate the effectiveness of legal services provided by state‑appointed attorneys and (2) identify any remaining barriers to ensuring equitable access to effective legal services. This assessment could include evaluating the extent to which BPH’s expectations for state‑appointed attorneys are consistent with best practices. In addition, the assessment could include surveying and/or interviewing parole candidates about their experience with state‑appointed attorneys, auditing state‑appointed attorneys to assess whether or not they are meeting minimal requirements (such as attending meetings with their clients), as well as collecting measures of the effectiveness of legal services (such as through observations of attorney performance during parole hearings).

As mentioned above, a report by UnCommon Law on the implementation of its pilot program is forthcoming. However, CDCR does not collect information about the extent to which hearing preparation services are currently being provided through other existing programs. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to report on the extent to which such programs provide hearing preparation services. Specifically, the report should include information about (1) how many people (and at what prisons) each program serves, (2) how many parole candidates (as opposed to all incarcerated people) the program has served or intends to serve, (3) the program cost per participant, (4) what types of hearing preparation services the program provides, (5) whether the hearing preparation services address the needs of any specific sub‑populations such as transgender and nonbinary candidates, and (6) any information available about the effectiveness of the program model or the program itself in providing hearing preparation services.

Use Analyses to Determine Future Legislative Action. If an analysis of recent efforts to improve attorney effectiveness and access to parole hearing preparation services does not reveal adequate improvements, the Legislature could consider pursuing different options. In doing so, it would want to consider any underlying problems and recommended solutions identified through the external research we recommend commissioning. It would also be important to consider any trade‑offs associated with each option, such as cost and effectiveness. Potential legislative options include:

- Shift Responsibility for Providing Attorneys to Indigent Candidates to an External Entity. If the external researcher finds that inadequate oversight and accountability of state‑appointed attorneys is undermining the effectiveness of legal services, the Legislature could consider shifting the responsibility to provide legal representation to a third party. For example, the Legislature could create a new entity within the state or fund an external entity (such as a nonprofit or a law school) to provide representation for all indigent candidates. This entity could be budgeted based on caseload estimates—similar to how BPH is currently budgeted—and would be responsible for determining how to deploy resources in the best interests of its clients. Because attorneys would be its employees, this entity would be responsible for monitoring and disciplining them to ensure provision of effective legal services.

- Further Increase Attorney Pay. If the external researcher identifies challenges with attracting and retaining competent attorneys and/or concludes that attorney caseloads are too high for them to be able to provide the desired legal services, the Legislature could consider further increasing attorney pay. Alternatively, rather than increasing pay for all cases, the state could allow attorneys to apply for additional pay for cases that are unusually complex.

- Provide Funding for Attorneys to Seek Expert Opinions in Some Cases. Payment for state‑appointed attorneys does not contemplate that an attorney may need to seek out an expert opinion—such as from an external psychologist or medical doctor—to provide important context around a candidate’s case factors. Moreover, any money that an attorney uses to pay an expert would come directly out of their pay, creating a strong disincentive to do so. It is possible that the external researcher’s assessment will reveal that some of the outcome disparity between state‑appointed and private attorneys stems from private attorneys’ occasional use of external experts. If so, the Legislature could designate funding that attorneys could apply for in order to pay for expert opinions in cases where doing so could make a significant impact on candidates’ chance of release.

- Expand Hearing Preparation Services Outside of the Attorney‑Client Relationship. If evaluation of the UnCommon Law pilot program shows that it is effective in providing hearing preparation services outside of the traditional attorney‑client relationship, the Legislature could consider expanding it in the future. However, in doing so, it would want to consider information reported by CDCR on what other hearing preparation services are being provided by grant‑funded programs. To the extent these programs use similar approaches as the UnCommon Law pilot program, the Legislature could prioritize expanding the UnCommon Law program at prisons that do not already have such programs. This would help the state reach sufficient system‑wide capacity faster and avoid duplication of services. Alternatively, to the extent these programs appear to be more cost‑effective than the UnCommon Law pilot program, the Legislature could consider expanding those programs instead.

Conclusion

The parole hearing process has significant implications for a substantial share of the state prison population. In many cases, it determines whether or not people will spend the rest of their lives in prison. In addition, it has implications for public safety and state spending on prisons. In our review, we identified two primary aspects of the current process that could lead to inequitable outcomes. Specifically, overly broad discretion afforded to key actors could allow biases to influence the outcomes of hearings. In addition, inequitable access to effective legal and hearing preparation services may be disadvantaging candidates who cannot access private attorneys and reinforcing other potential biases in the process. To mitigate these issues, we recommend that the Legislature consider limiting discretion and improve transparency and oversight of the process. To ensure equitable access to effective legal and hearing preparation services, we recommend that the Legislature first assess the impact of recent changes intended to improve service quality. We further recommend using the results of this assessment to inform whether future legislative action is needed.

Appendix: Selected References

Levinson, Justin D., G. Ben Cohen, and Koichi Hioki. “Deadly “toxins”: A national empirical study of racial bias and future dangerousness determinations.” Georgia Law Review 56 (2021): 225.

Murrie, Daniel C., et al. “Are forensic experts biased by the side that retained them?” Psychological Science 24.10 (2013): 1889‑1897.

Ratliff, K. A., & Smith, C. T. “Lessons from two decades of Project Implicit.” In Krosnick, J. A., Stark, T. H., & Scott, A. L. (Eds.) (in press). The Cambridge Handbook of Implicit Bias and Racism. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Ruhland, Ebony, et al. “The continuing leverage of releasing authorities: Findings from a national survey.” (2016).

Young, Kathryne M., and Hannah Chimowitz. “How parole boards judge remorse: Relational legal consciousness and the reproduction of carceral logic.” Law & Society Review 56.2 (2022): 237‑260.