LAO Contacts

- Ian Klein

- University of California

- Lisa Qing

- California State University

- California Student Aid Commission

- Paul Steenhausen

- California Community Colleges

January 31, 2023

The 2023-24 Budget

Higher Education Overview

Summary

Governor’s Budget Plan Focuses on Core Operations. This brief provides an overview and initial analysis of the Governor’s proposed higher education budget plan. This plan contains $1.5 billion in new higher education spending ($1.3 billion ongoing, $200 million one time). For the California Community Colleges (CCC), California State University (CSU), and University of California (UC), the Governor proceeds with the second year of his multiyear budget plans. The main element of the CCC roadmap and university compacts is annual unrestricted General Fund base increases for core operations. In 2023‑24, the Governor proposes $653 million for an 8.13 percent cost‑of‑living adjustment to CCC apportionments and $227 million and $216 million, respectively, for 5 percent base increases at CSU and UC. For the California Student Aid Commission, the Governor’s budget includes a slight decrease due to Cal Grant caseload adjustments, as well as $226 million in one‑time spending for the Middle Class Scholarship program agreed to last year. In response to the state’s projected deficit, the Governor also proposes a $2.3 billion package of funding delays and cost shifts, mostly affecting certain university facility projects.

Plan Has Some Positive Aspects, Some Risks and Shortcomings. We believe a positive aspect of the Governor’s plan is that it has a strong focus on access and preserving the segments’ core operations. The Governor’s budget also does not support any new ongoing higher education costs with one‑time funding. One risk with the plan, however, is that the base increases for the universities are contributing factors to the state deficits that arise under the multiyear outlook. Another, related risk is that the proposed budget solutions provide General Fund savings in 2023‑24, but they do so by pushing out costs such that budget challenges are exacerbated over the subsequent few years. A third risk is that the administration might be underbudgeting CCC apportionment costs. A shortcoming of the plan is that it has no compelling cost basis for the notably different base funding increases proposed for the segments. The plan also does not link university funding increases to specific budget priorities. Moreover, the plan does not update enrollment expectations across the segments despite updated data indicating sustained enrollment challenges. Furthermore, the proposed budget solutions create odd timing issues for certain UC capital projects and difficult trade‑offs among certain CSU capital projects.

Legislature Could Consider Various Improvements to Plan. We believe one improvement would be to link university funding increases to budget priorities. Another improvement would be to develop a plan to keep existing campus facilities in good condition—an issue on which the Governor is silent. The Legislature also could consider whether to move forward with certain CSU and UC capital projects given the state’s revised fiscal outlook. Additionally, it could consider recognizing savings from lower‑than‑expected enrollment across the segments in 2022‑23. Moreover, to help with budget preparation in the case state revenues fall, the Legislature could identify additional budget solutions. Furthermore, the Legislature could consider supporting a new tuition policy at CSU in 2023‑24 or 2024‑25 that would help expand budget capacity.

Introduction

Brief Focuses on the Governor’s Proposed Higher Education Budget Plan. Along with the rest of his budget plan, the Governor recently released his budget proposals for higher education. This brief highlights his major budget proposals for the California Community Colleges (CCC), the California State University (CSU), the University of California (UC), and the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC). The brief has three main sections. The first section provides an overview of the Governor’s higher education budget plan. The second section provides an initial high‑level assessment of that plan, and the last section identifies various ways the Legislature could consider improving the Governor’s plan. Over the coming weeks, our office plans to release additional budget briefs that delve more deeply into the Governor’s higher education proposals. Our EdBudget website contains a first batch of higher education budget tables reflecting the Governor’s proposals, with additional tables forthcoming.

Overview

In this section, we first identify funding designated for higher education, then discuss major higher education spending proposals, and conclude by summarizing the Governor’s proposed higher education budget solutions (including those related to student housing) that are designed to help the state solve a projected budget deficit in 2023‑24.

Funding by Source

Total Ongoing General Fund Support for Higher Education Increases. As Figure 1 shows, the Governor’s budget for 2023‑24 includes a total of $21.9 billion in ongoing General Fund support for the three segments and CSAC. The proposed 2023‑24 funding level is $584 million (2.7 percent) higher than the 2022‑23 level. All three segments see year‑over‑year funding increases, whereas CSAC sees a small decline. Of the annual increase, $539 million is non‑Proposition 98 General Fund and $45 million is Proposition 98 General Fund. Whereas CSU, UC, and CSAC generally receive state support entirely from non‑Proposition 98 General Fund, the state supports CCC primarily from Proposition 98 General Fund. (Proposition 98 is a measure that established a constitutional funding formula for K‑14 education that is commonly called the “minimum guarantee.” The state typically provides a set share of Proposition 98 funding—11 percent—to community colleges.)

Figure 1

Governor’s Budget Increases General Fund Support for Higher Education

Ongoing General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

Change From 2022‑23 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

CCCa |

$9,442 |

$9,315 |

$9,357 |

$43 |

0.5% |

|

CSUb |

4,606 |

5,050 |

5,344 |

294 |

5.8 |

|

UCb |

4,011 |

4,374 |

4,630 |

256 |

5.9 |

|

CSAC |

1,974 |

2,538 |

2,529 |

‑9 |

‑0.3 |

|

Totals |

$20,033 |

$21,276 |

$21,860 |

$584 |

2.7% |

|

Non‑Proposition 98 |

$11,243 |

$12,563 |

$13,102 |

$539 |

4.3% |

|

Proposition 98c |

8,790 |

8,713 |

8,758 |

45 |

0.5 |

|

aConsists of Proposition 98 funds for CCC programs as well as non‑Proposition 98 funds for CCC state operations, certain pension costs, and debt service. |

|||||

|

bConsists of non‑Proposition 98 funds for all ongoing purposes, including pensions, retiree health benefits, and debt service. |

|||||

|

cReflects General Fund that counts toward the minimum guarantee. The state sometimes designates some of this General Fund support for one‑time purposes. |

|||||

|

CSAC = California Student Aid Commission. |

|||||

Total Core Funding Provides a More Comprehensive Fiscal Picture. Whereas CSAC receives most of its funding from the state, the three segments receive substantial core funding from sources other than the state. For CCC, the largest nonstate fund source is local property tax revenue (most of which counts toward the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee). For CSU and UC, the largest nonstate core fund source is student tuition revenue. As Figure 2 shows, total core funding grows 1.6 percent for CCC, 3.8 percent for CSU, and 4.4 percent for UC. Whereas local property tax growth at CCC is outpacing growth in Proposition 98 General Fund, growth in tuition revenue at CSU and UC is lower than growth in non‑Proposition 98 General Fund.

Figure 2

Total Core Funding Also Increases

Ongoing Core Funds (Dollars in Millions)

|

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

Change From 2022‑23 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

CCC |

|||||

|

General Funda |

$8,790 |

$8,713 |

$8,758 |

$45 |

0.5% |

|

Local property taxa |

3,512 |

3,648 |

3,811 |

164 |

4.5 |

|

Additional General Fundb |

653 |

602 |

599 |

‑3 |

‑0.4 |

|

Additional local property taxb |

418 |

443 |

465 |

22 |

5.0 |

|

Student fees |

409 |

409 |

411 |

1 |

0.3 |

|

Lottery |

302 |

264 |

264 |

—c |

‑0.1 |

|

Subtotals |

($14,084) |

($14,079) |

($14,308) |

($229) |

(1.6%) |

|

CSU |

|||||

|

General Fundd |

$4,606 |

$5,050 |

$5,344 |

$294 |

5.8% |

|

Student tuition and fees |

3,240 |

3,061 |

3,077e |

$16 |

0.5% |

|

Lottery |

74 |

65 |

65 |

—c |

—c |

|

Subtotals |

($7,920) |

($8,176) |

($8,485) |

($310) |

(3.8%) |

|

UC |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$4,011 |

$4,374 |

$4,630 |

$256 |

5.9% |

|

Student tuition and fees |

5,295 |

5,335 |

5,530f |

195 |

3.6 |

|

Lottery |

53 |

46 |

46 |

—c |

‑0.1 |

|

Otherg |

395 |

395 |

395f |

— |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($9,754) |

($10,149) |

($10,600) |

($451) |

(4.4%) |

|

Totals |

$31,758 |

$32,404 |

$33,394 |

$990 |

3.1% |

|

aProposition 98 funds. |

|||||

|

b“Additional General Fund” refers to non‑Proposition 98 funds for CCC state operations, certain pension costs, and debt service. “Additional local property tax” refers to “excess” revenue for basic aid districts that does not count toward the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. |

|||||

|

cLess than $500,000 or 0.05 percent. |

|||||

|

dIncludes funding for pensions and retiree health benefits. |

|||||

|

eReflects Governor’s assumed level adjusted to reflect CSU’s estimate of additional revenue from proposed enrollment growth. |

|||||

|

fStandard budget displays are not yet available for UC. Amounts shown reflect LAO estimates based upon the information that is currently available |

|||||

|

gIncludes a portion of overhead funding on federal and state grants and a portion of patent royalty income. |

|||||

Governor Assumes No Tuition Increases at CCC and CSU. The Governor takes the same approach to tuition increases as he did last year. Specifically, the Governor proposes no increase in community college enrollment fees—retaining the existing per unit enrollment fee of $46, with annual enrollment fees for a student enrolled full time (30 units) totaling $1,380. (Enrollment fees at CCC were last raised in summer 2012, at which time the state increased the fee from $36 to $46 per unit.) The Governor’s budget also assumes no tuition increase at CSU—retaining annual systemwide tuition for a full‑time undergraduate student of $5,742. (Tuition charges at CSU were last raised in 2017‑18, with a 4.9 percent increase in undergraduate tuition assessed that year.)

Governor Assumes Tuition Increases Only at UC. In contrast to CCC and CSU, the Governor’s budget continues to assume UC increases tuition annually for certain students, consistent with the Board of Regents’ tuition policy. This policy pegs annual tuition increases to inflation (with certain caps). Incoming undergraduate students and all academic graduate students are subject to the tuition increases. Tuition charges are held flat for continuing undergraduate students. Under the policy, 2023‑24 tuition and systemwide fee rates are set at $13,752 for new undergraduate students and $13,104 for continuing undergraduate students, reflecting a $648 (4.9 percent) increase for new students. In 2023‑24, UC estimates generating an additional $147 million in revenue from tuition increases. It plans to use $58 million of this additional revenue for institutional student financial aid. (In addition, the CSAC budget reflects higher associated Cal Grant costs at UC. This Cal Grant cost increase is entirely offset by Cal Grant reductions associated with overall caseload.)

Freed‑Up One‑Time Funds Increase Amount Available for Community Colleges. Under the Governor’s budget, Proposition 98 funding for the community colleges grows $209 million (1.7 percent). The annual Proposition 98 growth rate, however, understates the amount of new funding available for the colleges’ ongoing programs. The state sometimes designates a portion of Proposition 98 funds for one‑time purposes. Last year, the state took this approach—providing nearly $700 million that counted toward the minimum guarantee for various one‑time community college initiatives. Those expiring one‑time funds are available in 2023‑24 for any Proposition 98 priority, including, at the state’s discretion, ongoing CCC programs. Under the Governor’s budget, these funds effectively are repurposed in this way.

Major Spending Proposals

Majority of New Spending Is for Community Colleges. Figure 3 shows the Governor’s major higher education spending proposals. Of the $1.5 billion in new higher education spending proposed over the period, $1.3 billion is for ongoing purposes and $200 million is for one‑time purposes. Of the ongoing spending increases, approximately 60 percent is for community colleges, with approximately 20 percent each for CSU and UC. All of the newly proposed one‑time spending is for CCC, with no proposed one‑time initiatives for CSU and UC this year. For CSAC, the Governor’s budget includes a slight decrease ($10 million) in ongoing Cal Grant spending due to caseload adjustments. It also includes an additional $226 million in one‑time spending for the Middle Class Scholarship program that the Governor and Legislature agreed to last year. Beyond these spending proposals and adjustments, the administration indicates an intent to introduce another community college proposal this spring. The administration indicates the proposal would provide colleges more flexibility in implementing certain categorical programs relating to academic and student support services. The overarching objective of the proposal would be to help colleges serve students more holistically, efficiently, and effectively.

Figure 3

Governor Proposes to Increase Spending in a Few Areas

Major General Fund Changes, 2023‑24 (In Millions)

|

Ongoing Spending |

|

|

CCC apportionments (8.13 percent) |

$653 |

|

CSU core operations (5 percent) |

267a |

|

UC core operations (5 percent) |

216 |

|

CCC categorical programs (8.13 percent) |

92 |

|

UC nonresident enrollment reduction (902 students) |

30 |

|

CCC enrollment growth (0.5 percent) |

29 |

|

Subtotal |

($1,286) |

|

One‑Time Initiatives |

|

|

CCC student enrollment and retention strategies |

$200 |

|

Total |

$1,486 |

|

aIncludes funding for pensions and retiree health benefits. |

|

Proposition 98 Outlook

Growth in Guarantee Might Be Lower Than Inflationary‑Driven Costs. Under the Governor’s budget, the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee grows at an average annual rate of 3.9 percent from 2023‑24 through 2026‑27. After accounting for baseline adjustments, the effective increase available for new spending commitments averages 3.2 percent per year. This rate of growth could be insufficient to fully cover the cost‑of‑living adjustments (COLAs) that the state typically applies to major K‑14 education programs. When the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee grows more slowly than the full statutory COLA rate, the Department of Finance has the authority to reduce the COLA rate such that it can be supported within the guarantee. Based upon current projections, a shortfall appears more likely than not in 2024‑25, with the state potentially providing only a partial COLA to community colleges (and school districts) that year. Shortfalls also are possible in 2025‑26 and 2026‑27. We discuss these issues in more detail in our forthcoming Proposition 98 budget brief.

Governor Proposes Second Year of CCC Roadmap and University Compacts. Last year, the Governor proposed multiyear budget plans for each of the segments. Though the Legislature did not codify these multiyear plans, the Governor’s 2023‑24 higher education budget proposals are consistent with them. The largest component of these plans is annual unrestricted base increases. These base increases are loosely linked with performance expectations in certain areas, including student access, success, and equity; intersegmental coordination; and workforce alignment. Per the multiyear agreements, the segments are to report their performance in these areas each year through 2026. CSU and UC released their first progress reports in fall 2022, with CCC expected to release its first progress report in summer 2023.

Proposed Base Increase for Colleges Is Higher Than for Universities. As Figure 3 shows, for CCC apportionments (unrestricted base funding), the Governor proposes a $653 million increase to cover an 8.13 percent cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA). This proposed rate increase is linked to a measure of inflation that will be updated in late April. (The Governor also proposes to grant an 8.13 percent COLA to certain CCC categorical programs as well as certain K‑12 programs.) For CSU and UC, the Governor proposes $227 million and $216 million, respectively, to cover 5 percent base General Fund increases. In addition, the Governor’s budget provides CSU with $39 million ongoing General Fund to cover certain benefit cost increases ($36.7 million for retiree health benefits and $2.6 million for certain pension costs). The three segments can use base funding increases for any of their core operations, including employee salaries and benefits, utilities, supplies, and equipment.

Governor Proposes Enrollment Growth at All Three Segments. For CCC, the Governor’s budget includes $29 million to cover 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth in 2023‑24, equating to 5.496 additional full‑time equivalent (FTE) students. The Governor also expects CSU and UC to increase resident undergraduate enrollment. For CSU, the Governor assumes growth of 3,434 additional FTE students (1.1 percent) from 2022‑23 to 2023‑24. For UC, the Governor assumes growth of 4,203 additional FTE students (2.1 percent). Although the Governor proposes budget bill language referring to the CCC enrollment funds and growth target, he proposes no such budget provisions for the universities. (The budget provisions for CSU and UC include much broader language specifying that the base funding increases are “to support operational costs.”)

Governor Takes Different Enrollment Funding Approach for Colleges and Universities. Whereas the Governor proposes a separate enrollment growth appropriation for CCC, he expects the universities to cover the cost of enrollment growth from within their 5 percent base increases. Though consistent with the approach specified in the Governor’s compacts, this approach differs from the one the state historically has used to fund CSU and UC enrollment growth. Typically, the state has provided CSU and UC with separate appropriations specifically for this purpose on top of the universities’ base increases for core operations.

Governor Proposes “Grace Period” for Segments to Reach Enrollment Targets. All three segments are expected to have soft enrollment levels in 2022‑23. Though preliminary systemwide CCC data are not yet available, data from a sample of community colleges suggests systemwide enrollment could be either about flat or up somewhat in 2022‑23 from a depressed 2021‑22 level. At CSU, resident undergraduate enrollment is expected to fall by about 5 percent, whereas it is expected to remain about flat at UC (down 0.1 percent). The 2022‑23 Budget Act included language requiring the administration to reduce enrollment growth funding proportionally to any enrollment shortfalls at the universities. Specifically, these budget provisions directed the administration to reduce funding for enrollment shortfalls at CSU in 2022‑23 and at UC in 2023‑24. The Governor, however, is not proposing to reduce any 2022‑23 enrollment growth funding at any of the segments. Instead, the administration effectively is letting each of the segments retain their associated enrollment growth funding in 2022‑23 ($81 million at CSU, $52 million at UC, and $27 million at CCC) and use all or a portion of those funds for other purposes. Though the Governor proposes no fiscal repercussions for any of the segments missing their enrollment targets in 2022‑23, he has certain expectations moving forward. For CCC, he signals community colleges that continue missing their targets should plan for associated funding reductions beginning in 2024‑25. For UC and CSU, he expects cumulative enrollment growth targets to be reached by the final year of the compacts (2026‑27).

Governor Has Only a Few Other Higher Education Spending Proposals. Beyond base increases and enrollment growth, the Governor has only a few other higher education spending proposals this year—a stark contrast to the number of higher education spending proposals he has introduced in previous years. Of these remaining proposals, the two most notable ones are related to enrollment. One of these proposals has UC continuing to replace some nonresident students with resident students at its three most selective campuses (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego). The second of these proposals has the community colleges continuing efforts to regain enrollment.

Proposed Funding Delays and Shifts

Governor Proposes Actions in Response to Projected State Budget Deficit. The proposed actions, taken together, would enable the state to meets its constitutional requirement to adopt a balanced budget in 2023‑24. As we discuss in The 2023‑24 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, the proposed actions, however, are insufficient to keep the state budget balanced in future years, with projected out‑year deficits in the $4 billion to $9 billion range. Within higher education, the Governor proposes only non‑Proposition 98 budget solutions, with no proposed Proposition 98 budget solutions. (The Governor proposes to reduce one‑time Proposition 98 funding for community college facility maintenance projects, but he effectively repurposes that funding for another one‑time community college initiative relating to student enrollment and retention strategies.) Though the Governor’s package of budget solutions in 2023‑24 contains no Proposition 98 components, the Proposition 98 side of the budget also is expected to face challenges in future years, as discussed in the nearby box.

Governor Proposes Various Higher Education Budget Solutions. Within the non‑Proposition 98 side of the budget, the administration proposes three major types of budget solutions: (1) funding reductions (some of which are linked to certain trigger conditions), (2) funding delays, and (3) fund or cost shifts. Of the higher education budget solutions, none are funding reductions—the Governor classifies all of them as either funding delays or shifts. Figure 4 shows the proposed higher education budget solutions. The proposed solutions involve several specific CSU and UC capital outlay projects, two housing‑related programs that affect all three segments, and one CSAC program. These proposed budget actions yield a total of $2.3 billion in General Fund savings over the 2021‑22 through 2023‑24 period. Though the proposed funding delays and cost shifts generate immediate savings, they do so by pushing costs out to future years, with $2 billion in associated General Fund costs emerging over the 2024‑25 through 2026‑27 period.

Figure 4

Governor Proposes Several Higher Education Budget Solutions

General Fund Impacta (In Millions)

|

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

|

|

Financing Changesb |

||||||

|

CSU Bakersfield Energy Innovation Center |

— |

$83 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

CSU San Diego Brawley Center |

— |

80 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

CSU San Bernardino Palm Desert Center |

— |

79 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

CSU University Farms |

— |

75 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

CSU Fullerton Engineering and Computer Science Innovation Hub |

— |

68 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

CSU San Luis Obispo Swanton Pacific Ranch |

— |

20 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

CSU new associated debt service |

— |

— |

‑$27 |

‑$27 |

‑$27 |

‑$27 |

|

Subtotals |

(—) |

($405) |

(‑$27) |

(‑$27) |

(‑$27) |

(‑$27) |

|

Funding Delays |

||||||

|

California Student Housing Revolving Loan Fundc |

— |

— |

$900 |

$250 |

‑$1,150 |

— |

|

Higher Education Student Housing Grant Programc |

— |

— |

250 |

‑250 |

— |

— |

|

CSAC Golden State Education and Training Grants |

$400 |

— |

— |

‑200 |

‑100 |

‑$100 |

|

UC Los Angeles Institute of Immunology and Immunotherapy |

— |

$100 |

100 |

‑200 |

— |

— |

|

UC Berkeley Clean Energy Project |

— |

— |

83 |

‑83 |

— |

— |

|

UC Riverside and UC Merced campus expansion projects |

— |

— |

83 |

‑83 |

— |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($400) |

($100) |

($1,416) |

(‑$566) |

(‑$1,250) |

(‑$100) |

|

Totals |

$400 |

$505 |

$1,389 |

‑$593 |

‑$1,277 |

‑$127 |

|

aPositive amounts indicate General Fund savings. Negative amounts indicate General Fund costs. |

||||||

|

bThe administration proposes reducing CSU funding by $405 million, having CSU sell systemwide revenue bonds of a like amount, and providing $27 million ongoing to cover the associated debt service. |

||||||

|

cCCC, CSU, and UC campuses may apply to these programs for help financing their housing projects. |

||||||

|

CSAC = California Student Aid Commission. |

||||||

Comparing Proposed Funding and Projected Cost Increases

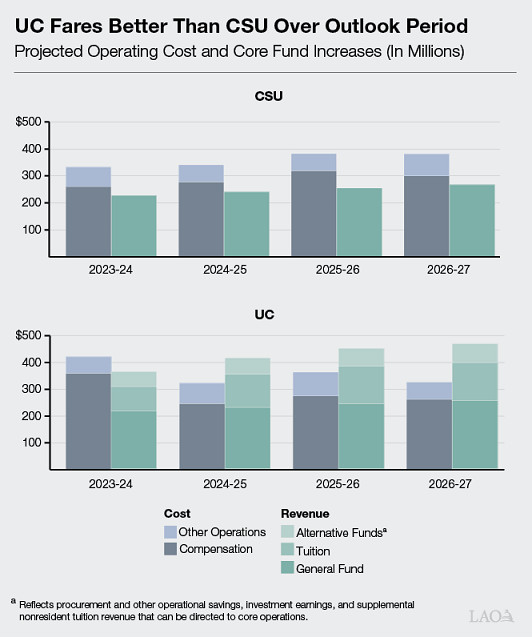

We compare the Governor’s proposed base funding increases for the universities under the compacts to their projected operating cost increases from 2023‑24 through 2026‑27. For this analysis, we assume annual salary growth of approximately 4 percent, growth in annual health care costs in the 4 percent to 7 percent range, and growth in operating equipment and other expenses of approximately 4.5 percent (on average over the period). We also account for estimated increases in the universities’ pension and debt‑service costs. We assume any enrollment growth funding and associated cost is treated separately. The figure below shows the results of this analysis.

For 2023‑24, projected operating cost increases at the California State University (CSU) exceed the Governor’s proposed 5 percent base increase by more than $100 million. At the University of California (UC), projected operating cost increases in 2023‑24 are approximately $60 million higher than increases in General Fund, tuition, and alternative fund sources combined. (Each year, UC aims to identify procurement and other operational savings, investment earnings, and supplemental nonresident tuition revenue that it can direct to its core operations.) Whereas CSU’s operating cost increases consistently exceed the Governor’s proposed base increases over the outlook period, the pattern for UC changes over the last three years of the period. Those years, UC’s operating cost increases consistently are lower than what we project UC would receive from General Fund, tuition, and alternative fund sources combined. The main difference between the segments over the period is that UC raises additional revenue from tuition increases, whereas CSU does not.

Budget Solutions Are Not Expected to Create Issues With State Appropriations Limit (SAL). The California Constitution imposes a limit on the amount of revenue the state can appropriate each year. The state can exclude certain capital outlay appropriations from the SAL calculation, effectively making it more manageable to meet the overall SAL requirement. Last year, the state approved many capital outlay projects in an effort to meet its SAL requirement. Under the Governor’s budget, some of these projects would be financed differently or delayed. Though these proposed actions would reduce the amount excluded from the SAL calculation in the near term, many other factors are affecting the state’s overall SAL requirement. While we are still reviewing the administration’s SAL estimates, we understand the Governor’s budget continues to meet near‑term SAL requirements even with the proposed capital outlay‑related budget solutions. At this time, SAL requirements are not expected to present significant challenges for the state in crafting its 2023‑24 budget.

Different Budget Solution Approaches Taken for CSU and UC. Though all the proposed budget solutions for CSU and UC involve capital outlay projects, the specific approach taken by the administration varies. For CSU, the Governor proposes to change how the projects are financed. Rather than providing General Fund upfront for the projects, the Governor proposes to have CSU sell systemwide revenue bonds and have the state provide a General Fund augmentation to cover the associated debt service. In contrast, the Governor proposes to delay funding for the UC projects. The administration indicates that it did not propose debt‑financing for the UC projects because those projects were at earlier phases with more unknown factors.

Assessment

In this section, we identify positive aspects of the Governor’s proposed higher education plan, then identify shortcomings of that plan, including highlighting certain drawbacks of the Governor’s proposed higher education budget solutions.

Positive Aspects of Plan

Governor Focuses on Core Operations. We believe a positive aspect of the Governor’s higher education spending plan is that it has relatively few proposals and those proposals have a strong focus on access and preserving the segments’ core operations. We believe focusing on core operations and not scattering funds across many programs and new initiatives is a better budget approach, especially given the current state fiscal context. By focusing new spending on core operations, the Governor makes handling key budget challenges more manageable for the segments. In particular, focusing on core operations helps the segments address inflationary pressures; respond to employee recruitment, retention, and compensation issues; and sustain program quality.

Higher Education Spending Plan Has No New Structural Shortfalls in 2023‑24. The Governor’s budget does not support any new ongoing higher education costs with one‑time funding. (The Governor’s budget funds some ongoing Middle Class Scholarship costs with one‑time funding, but the Legislature previously agreed to this action.) Though no new structural shortfalls emerge within higher education, the Governor proposes funding $1.4 billion in ongoing K‑12 Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) costs with one‑time funds (an issue we discuss in more detail in our forthcoming Proposition 98 budget brief). This structural shortfall in the K‑12 budget would heighten budget challenges for school districts in 2024‑25. Importantly, the main reason the Governor is able to avoid a structural shortfall for community colleges (despite the colleges also being funded within the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee) is because the state took a less risky budget approach for them last year. Last year, the community college budget had a proportionally larger budget cushion than school districts. Because the Governor’s higher education spending plan does not have any new core operating shortfall akin to the LCFF shortfall, the higher education segments would be in a stronger fiscal position than school districts entering 2024‑25. (The Governor’s budget, however, might have underbudgeted CCC apportionments, as discussed in the next section.)

More Flexibility Could Enable Community Colleges to Serve Students Better. Over the past several years, the state has created many additional CCC categorical programs. The proliferation of these programs has increased colleges’ administrative burden and exacerbated program silos, which, in turn, likely have generated greater inefficiencies. Were the Governor this spring to introduce a flexibility proposal for the colleges, we believe it could be worth pursuing. We think a promising proposal would strike a balance between focusing on outcomes and accountability while providing more flexibility for districts in how they achieve those outcomes. Additional flexibility in operating programs and reporting on the outcomes of those programs might allow the colleges to better serve students, including by allowing them to dedicate more time to student support rather than administration.

Shortcomings of Plan

Ongoing Proposals Present a Risk to State Budget Moving Forward. Though we believe the Governor’s higher education spending plan has certain positive aspects, it also has some risks and shortcomings. One risk is linked to the proposed CSU and UC base increases, as these ongoing General Fund augmentations are contributing factors to the state budget deficits that arise under the multiyear outlook. Were the state revenue situation to deteriorate further, any ongoing General Fund augmentations made in 2023‑24 will become harder for the state to sustain over the near term. Under some revenue scenarios, the state would face difficulty affording future base increases for CSU and UC over the next few years.

Proposed Budget Solutions Provide Temporary Fix. A second, related risk emanates from the Governor’s proposed higher education budget solutions. The proposed funding delays and cost shifts (for example, with certain CSU and UC capital projects) provide General Fund savings in 2023‑24, but they do so merely by shifting costs out one or more years. Importantly, nearly all the higher education budget solutions in 2023‑24 immediately turn into budget challenges in 2024‑25.

Community College Apportionment Costs Might Be Underbudgeted. A third risk in the Governor’s budget relates to how it implements a “funding stability” provision that applies to community colleges. This provision protects community college districts from sudden drops in funding due to uncontrollable events. Over the past several years, relatively few community college districts have been affected by this statutory protection, in part because extraordinary pandemic‑related hold harmless provisions have been in place. In 2023‑24, for various reasons (including the expiration of these other hold harmless provisions), many districts could be affected by the funding stability provision. The way the Governor’s budget calculates the cost of this provision differs from the Chancellor’s Office’s interpretation, and we believe it could understate the cost of funding CCC apportionments. The Legislature likely will want to investigate these differences more closely in the coming weeks to determine if an apportionment shortfall exists in 2023‑24 and, if so, identify options for responding. We plan to cover this issue in more detail in our forthcoming community college budget brief.

Community Colleges and Universities Are Treated Differently Despite Similarities. Under the Governor’s budget, community colleges receive larger base funding increases than the universities, with the 8.13 percent COLA for the colleges roughly comparable to the universities’ approximately 4 percent increases in core funding. Though different base increases for each of the segments could be justified, the administration offers no compelling cost or program basis for such differences this year. (The higher COLA rate for community colleges is due entirely to the colleges being a part of Proposition 98 calculations. These calculations, however, do not have a strong nexus to underlying community college cost pressures.) Moreover, the three segments have similar cost drivers. All are experiencing salary pressures, increases in their health care premiums, increases in their pension contribution rates, and inflationary pressures in other key areas, including utilities, supplies, and equipment.

University Augmentations Are Not Clearly Tied to Budget Priorities. Whereas the community college apportionment formula is designed so that districts effectively are required to earn their base funding increases, the state has no such funding requirements for the universities. Specifically, for community colleges, the Student Centered Funding Formula allocates funds based upon enrollment counts, certain student group counts (including low‑income student counts), and performance outcomes (including transfer rates and degree attainment rates). Colleges with more enrollment, serving more low‑income students, and achieving better outcomes (including for their low‑income students) generally earn more funding than other colleges. In contrast, no formula links the funding the Governor proposes for CSU and UC to their actual enrollment levels, the composition of their student bodies, or their specific performance outcomes. Furthermore, the Governor’s proposed base increases for CSU and UC generally are not linked to any specific cost increases (such as for salaries, utilities, and equipment)—reducing both budget transparency and accountability.

Governor Does Not Update Enrollment Plans Despite Better Data Being Available. The segments are reporting important enrollment trends. In particular, over the past few years, the number of transfer students, retention rates, and credit load per term all have fallen. During this period, the labor market also has been historically strong, with many job openings. Though the incoming freshman class at CSU rebounded from fall 2021 to fall 2022, those rebounds have not been enough to offset the enrollment declines driven by these other factors. At UC, the total incoming freshman class dropped by 6.1 percent from fall 2021 to fall 2022 (with resident undergraduates about flat and nonresident undergraduates dropping 26 percent from a peak 2021 level). The combined effect of all these factors is that the segments have smaller existing student cohorts that are likely to remain for the next few years as the cohorts work their way through college. Despite these indicators, the Governor proposes no changes to his enrollment expectations either for 2023‑24 or the next few years.

UC Budget Solutions Have Odd Timing Issues. Typically, capital projects move through standard phases, beginning with preliminary plans and working drawings, followed by construction. State funding, in turn, is linked with these phases. The state tends to provide a relatively small amount of funding the first year or two of projects as planning work is undertaken and construction cost estimates are refined. It then provides the bulk of project funding in year two or three once construction commences. In contrast to these standard budget practices, UC capital outlay projects under the Governor’s budget solution proposals would get a substantial round of initial funding in 2022‑23 (much more than needed for preliminary plans and working drawings), no funding in 2023‑24, and then substantial funding again in 2024‑25. As of the time of this writing, it was not yet clear how UC would respond to these fluctuations in project funding. The proposed approach, however, is questionable, as it disconnects funding from specific project activities—likely providing too much project funding too soon and then delaying funding even when projects could be shovel ready. It also places UC projects in a particularly risky position, with large amounts already provided for each project, but large amounts of remaining project funding not guaranteed.

CSU Budget Solutions Could Be Crowding Out Higher‑Priority Projects. As part of his budget solutions, the Governor is proposing to provide CSU with an ongoing $27 million General Fund augmentation to cover debt service on six capital budgets (rather than providing $405 million upfront for the projects). Though the Governor’s budget includes this augmentation for debt service, it does not include any augmentation for debt service on the capital outlay projects that CSU submitted through the standard state review process last fall. The CSU Board of Trustees requested a $50 million General Fund augmentation for these latter projects. Many of these project proposals are for renovating existing facilities and infrastructure that are in poor condition. By comparison, most of the six projects that would receive financing in 2023‑24 under the Governor’s budget are for new facilities or expansions. Moreover, some of these projects were not identified in CSU’s 2022‑23 five‑year capital plan, indicating that the campus and the system had not considered them among their highest and most urgent capital priorities.

Recommendations

In this section, we first identify various ways in which the Legislature could improve the Governor’s proposed spending plan for higher education. We then identify several options the Legislature has for improving the Governor’s package of higher education budget solutions. We end by highlighting major higher education initiatives for which the Legislature might wish to conduct oversight.

Improve Key Components of Spending Plan

Link University Funding Increases More Tightly With Spending Priorities. Overall, we continue to recommend the Legislature take a more transparent budget approach for the universities. In contrast to the Governor’s approach, the Legislature could identify its budget priorities in 2023‑24 and provide funding linked to those priorities. For example, with the same total ongoing funding increase that the Governor proposes for CSU ($227 million), the Legislature could fund a 3 percent increase in CSU’s employee compensation pool ($157 million), certain health benefit increases ($51 million), and some capital renewal projects ($20 million). (Growing resident undergraduate enrollment by 1 percent would cost approximately $35 million, but CSU is not expecting to grow its enrollment in 2023‑24 above already funded levels.)

Consider Expanding Budget Capacity at CSU Through Tuition Increases. Under the Governor’s budget, CSU fares worst among the segments from a fiscal perspective, receiving a smaller base increase than CCC and no additional revenue from tuition increases as UC does. Moreover, CSU is unable to cover all of its projected operating cost increases within the Governor’s proposed 5 percent base funding increase. (We compare CSU’s and UC’s funding and operating cost increases in the nearby box.) Given this shortfall, the state could consider expanding CSU’s budget capacity by supporting tuition increases beginning either in 2023‑24 or 2024‑25. Importantly, pursuing tuition increases in 2023‑24 would require quick action over the next few months whereas pursuing them for 2024‑25 would allow ample time for consultation and notification. Whether begun in 2023‑24 or 2024‑25, the state could encourage CSU to develop a tuition policy similar to UC’s tuition policy—that is, a policy that results in gradual, predictable, and moderate increases in student charges. Such a tuition policy would not only expand budget capacity at CSU but also would help avoid the tuition spikes and plateaus that have been common historically.

Begin Developing a Plan to Keep Existing Campus Facilities in Good Condition. Though each of the higher education segments has an extensive footprint, with some building components reaching the end of their useful life each year, neither the state nor the segments have a plan for funding these capital renewal projects. Moreover, neither the CCC roadmap nor university compacts include any discussion of how the segments and state should address capital renewal. Furthermore, the Governor’s budget includes no funding increases specifically for keeping colleges’ or universities’ existing academic facilities and infrastructure in good condition. (It does contain a proposed decrease in facility maintenance funding for the colleges.) Perhaps unsurprisingly given these factors, spending on capital renewal to date has been insufficient to keep pace with emerging needs, and project backlogs have been large and growing. Absent a plan to address these issues moving forward, project backlogs very likely will continue to grow—leading to higher costs and greater risk of programmatic disruptions. We recommend the Legislature work with the segments to begin developing capital renewal plans. Such plans likely would involve several key elements, including setting a funding target that is aligned with emerging needs, sharing the cost between the state and the segments, and phasing in funding increases over time. (We discuss these plans and related issues in more detail in our recent brief, Addressing Capital Renewal at UC and CSU.)

Explore a Revised Package of Budget Solutions

Could Revisit Whether to Move Forward With Certain University Capital Projects. Rather than changing how certain capital projects are financed or delaying some of their funding, the Legislature could reconsider whether to move forward with them. Many factors have changed since these projects were first considered. Most notably, the state’s budget situation has deteriorated, construction costs have escalated at a historically fast pace, and interest rates are higher. All of these factors make the trade‑offs among capital projects and across the capital and operating sides of the segments’ budgets more difficult.

Could Change Approach to Financing University Capital Projects. Were the Legislature to decide that certain capital projects are worth approving in 2023‑24, it could consider the most advantageous way to finance those projects. If the Legislature were to choose to provide upfront General Fund cash for the projects (as the Governor proposes for the UC projects), overall project costs would be lower given no interest costs would be incurred. If the Legislature were to choose to have the segments sell systemwide revenue bonds with the state covering the associated debt service (as the Governor proposes for CSU projects), then overall project costs would be higher given the associated interest costs. More projects, however, likely could be financed over the near term. Given these significant trade‑offs, the Legislature could consider establishing some criteria for when to finance a project using upfront cash versus borrowing. The method the state selects for financing projects could depend in part upon its relative near‑term and long‑term fiscal outlook, with borrowing more preferable if the near‑term situation is poor but the long‑term outlook is strong. As it has typically done, the state also could require projects to meet criteria such as addressing a critical life‑safety issue or mitigating overcrowding, with a somewhat more stringent threshold used for projects that incur interest costs. (It could apply such criteria to many proposed capital projects, including ones outside of higher education.)

Could Recognize Savings Due to Enrollment Declines. Rather than allowing the segments to use enrollment growth funding in 2022‑23 for other purposes, the Legislature could reduce enrollment funding proportionally to enrollment declines or, for CCC, sweep unearned growth funding. Once the segments begin growing their enrollment, the Legislature could provide corresponding funding at that time. Under this approach, the state could achieve up to an additional $133 million in non‑Proposition 98 General Fund savings ($81 million at CSU and $52 million at UC), while potentially freeing up several millions of dollars in Proposition 98 funding at CCC.

Could Consider Adding Other Budget Solutions. The Legislature could identify other potential higher education budget solutions to give it more options moving forward. The Legislature might prefer some of its new options to the ones the Governor proposes. Moreover, considering additional budget solutions now would allow the state to better prepare for a possible deterioration of the state’s budget condition given the heightened risk of revenue shortfalls. Furthermore, developing a larger set of potential budget solutions now allows the Legislature to do so deliberately rather than under the pressure of the May Revision. One way the Legislature could start identifying additional budget solutions is by revisiting recent augmentations. In some cases, large augmentations authorized in 2021‑22 or 2022‑23 might not yet have been spent or might be viewed in a different light given the projected state budget deficit. Figure 5 lists temporary spending authorized over the past couple of years. For the initiatives listed in the figure, the Legislature could decide whether to reduce funding or delay funding relative to the Governor’s already proposed levels. In some cases, such as with UC’s climate change initiatives, the Legislature likely would want to learn more about implementation to date before proceeding. In most cases, the Legislature also would first need to confirm the availability of funding to ensure savings could be achieved.

Figure 5

Adding to List of Potential Solutions Helps With Budget Preparation

Major, One‑Time, Non‑Proposition 98 General Fund Higher Education Augmentations (In Millions)

|

Segment/ Department |

Description |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

|

Various |

California Student Housing Revolving Loan Fund |

— |

— |

$900 |

|

Various |

Higher Education Student Housing Grant Program |

$700 |

$752 |

750 |

|

CSU |

CSU Humboldt transition to polytechnic universitya |

458 |

25 |

25 |

|

CSU |

Deferred maintenance and energy efficiency projects |

325 |

125 |

— |

|

CSU |

CSU Dominguez Hills capital outlay projects |

60 |

— |

— |

|

CSU |

CSU Stanislaus Stockton Center Acacia Building replacement |

54 |

— |

— |

|

CSU |

CSU Bakersfield Energy Innovation Center |

— |

83 |

— |

|

CSU |

CSU San Diego Brawley Center |

— |

80 |

— |

|

CSU |

CSU San Bernardino Palm Desert Center |

— |

79 |

— |

|

CSU |

CSU University Farms |

— |

75 |

— |

|

CSU |

CSU Fullerton Engineering and Computer Science Innovation Hub |

— |

68 |

— |

|

UC |

Deferred maintenance and energy efficiency projects |

325 |

125 |

— |

|

UC |

UC Los Angeles Institute for Immunology and Immunotherapy |

— |

200 |

200 |

|

UC |

Climate change initiatives |

— |

185 |

— |

|

UC |

UC Riverside and UC Merced campus expansion projects |

— |

83 |

83 |

|

UC |

UC Berkeley Clean Energy Project |

— |

83 |

83 |

|

UC |

Charles R. Drew University medical education buildings |

50 |

— |

— |

|

CSAC |

Golden State Education and Training Grants |

500 |

— |

— |

|

CSAC |

Golden State Teacher Grants |

500 |

— |

— |

|

CSAC |

Learning‑Aligned Employment Program |

200 |

300 |

— |

|

CSAC |

Middle Class Scholarships |

— |

— |

227 |

|

DGS |

Regional K‑16 Education Collaboratives |

250 |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$3,422 |

$2,263 |

$2,268 |

|

|

a2021‑22 augmentation consists of $433 million one time and $25 million ongoing. |

||||

|

CSAC = California Student Aid Commission and DGS = Department of General Services. |

||||

Conduct Oversight of Major Initiatives

Closely Monitor Implementation of Major Higher Education Initiatives. Though the Governor’s budget for 2023‑24 proposes few new initiatives, the state over the past several years has launched many higher education initiatives, including major expansions of student financial aid programs. The Legislature has expressed interest in keeping apprised of the implementation of these initiatives and monitoring their outcomes. Figure 6 contains a list of major higher education initiatives undertaken the past several years. This list focuses on ongoing programs as well as large, one‑time initiatives that likely have a considerable amount of funds still available to be spent over the next few years. The Legislature could have informational hearings or otherwise collect related information about some or all of these initiatives. Key oversight questions include:

- What implementation activities have been undertaken to date? What major activities have yet to be launched? What is the time line for launching those remaining activities?

- Is the program over‑ or under‑subscribed? To what factors does the segment/department attribute the mismatch between funded slots and program demand?

- Have any previously unknown or unexpected factors affected program costs? Are costs per participant (or outcome) notably different from budget assumptions?

- What have been program outcomes to date? Is certain data being collected that will enhance program assessment over the coming years?

- Has the segment/department identified ways the programs could be improved?

Figure 6

Legislature Could Monitor New and Expanded Programs

Major Initiatives, 2019‑20 Through 2022‑23

|

CCC |

|

Cybersecurity strategies |

|

Foster youth programs |

|

Health Care Pathways for English Learners |

|

High Road Training Partnerships |

|

Part‑Time Faculty Health Insurance |

|

State operations |

|

Strong Workforce and apprenticeship program expansions |

|

Student Basic Needsa |

|

Student enrollment and retention strategies |

|

Student Housing Construction Grants |

|

Student Housing Planning Grants |

|

Student Success Completion Grants |

|

Student support program expansions |

|

Transfer and common course numbering reforms |

|

Zero‑textbook‑cost degrees |

|

CSU |

|

Foster youth programs |

|

Graduation Initiative 2025 |

|

Student Basic Needsa |

|

Student Housing Construction Grants |

|

UC |

|

Climate change initiatives |

|

Foster youth programs |

|

Nonresident enrollment reduction plan |

|

Programs in Medical Education (PRIME) |

|

Student Basic Needsa |

|

Student Housing Construction Grants |

|

UC Merced medical school project |

|

UC Riverside medical school project |

|

CSAC |

|

Cal Grant CCC Expanded Entitlement Awards |

|

Cal Grant nontuition awards for foster youth and SWDC |

|

Golden State Education and Training Grant Program |

|

Golden State Teacher Grant Program |

|

Learning‑Aligned Employment Program |

|

Middle Class Scholarship Program |

|

State operations |

|

aConsists of programs to address student housing and food insecurity as well as student mental health. |

|

CSAC = California Student Aid Commission and SWDC = students with dependent children. |