LAO Contact

February 23, 2023

The 2023-24 Budget

California Student Aid Commission

- Introduction

- Overview

- Cal Grants

- Middle Class Scholarships

- Golden State Education and Training Grants

- Golden State Teacher Grants

- State Operations

Summary

Brief Covers the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC). This brief analyzes the Governor’s budget proposals for Cal Grants, Middle Class Scholarships (MCS), Golden State Education and Training Grants, Golden State Teacher Grants, and CSAC state operations.

Recommend Determining Now Whether to Proceed With Cal Grant Reform. Last year, the state crafted a plan to potentially restructure the Cal Grant program in 2024‑25. The program changes, which are estimated to cost $365 million ongoing, would be triggered if the state determines in spring 2024 that sufficient General Fund is available. Based on our budget projections, the Cal Grant program changes are very unlikely to be triggered. Moreover, the timing of the trigger is problematic for incoming students, some of whom would need to make college enrollment decisions without knowing whether they will be eligible for a Cal Grant award or how much aid they will receive. We recommend the Legislature instead determine during this year’s budget process whether to proceed with Cal Grant reform in 2024‑25. Expanding the program would benefit many additional low‑income students, but the expansion entails difficult fiscal trade‑offs. Given the state’s projected out‑year operating deficits, funding to support the expansion in 2024‑25 likely would need to be redirected from other existing ongoing purposes.

Recommend Any MCS Expansion Be Supported With Ongoing Funding. Consistent with last year’s budget agreement, the Governor’s budget increases MCS funding by $226 million one‑time General Fund in 2023‑24. Using one‑time funds for an ongoing financial aid program has notable drawbacks, especially for continuing students who would see their award amounts reduced in 2024‑25. In contrast, ongoing funding would provide greater certainty to students and families, while also better reflecting the out‑year cost pressures for the state to maintain the higher funding level. We recommend the Legislature weigh expanding the MCS program against its other financial aid priorities, taking into account the state’s budget condition. We further recommend the Legislature provide ongoing funding for any MCS expansion, while rejecting the proposed one‑time funding and counting this as a budget solution.

Recommend Discontinuing Golden State Education and Training Grants. Since the state first created this program to provide grants to workers displaced by the pandemic, the underlying need for the program has diminished. Notably, the labor market has improved, and the program is reaching far fewer recipients than intended. Moreover, displaced workers have various other options for affordable education and training. Whereas the Governor proposes delaying the bulk of program funding ($400 million out of $500 million one‑time General Fund) to future years, we recommend the Legislature instead discontinue this program and remove any remaining funding (an estimated $470 million) at the end of 2022‑23.

Brief Includes Several Other Recommendations. Regarding the Golden State Teacher Grants, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposed trailer bill language that would expand grant eligibility. The administration’s rationale for the expanded eligibility is to increase program uptake, but data indicate the program is already fully subscribed. Regarding CSAC state operations, we recommend adopting the Governor’s proposals to increase staffing and funding for cybersecurity and human resources, as CSAC has provided adequate associated workload justification. However, we recommend rejecting the Governor’s proposal for CSAC to distribute financial aid toolkits to high schools, as the state is already taking several other actions to help high schools increase the number of their students completing financial aid applications.

Introduction

Brief Focuses on CSAC Budget. CSAC administers many of the state’s student financial aid programs. This brief is organized around the Governor’s 2023‑24 budget proposals for CSAC. The first section provides an overview of CSAC’s budget. The remaining sections focus on Cal Grants, MCS, Golden State Education and Training Grants, Golden State Teacher Grants, and state operations, respectively. This brief is the fifth in our series of higher education budget analyses. All of our 2023‑24 budget reports can be accessed online.

Overview

Governor’s Budget Provides $3.2 Billion for CSAC in 2023‑24. As Figure 1 shows, the proposed 2023‑24 funding level is $178 million (5 percent) lower than the revised 2022‑23 level. The lower funding level is primarily due to changes in one‑time funding, with ongoing funding remaining roughly flat from the previous year. The two main fund sources for CSAC are state General Fund and federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). In 2023‑24, state General Fund would comprise 87 percent of CSAC funding and federal TANF would comprise 12 percent. The remainder would come from various sources, including reimbursements from other departments.

Figure 1

Ongoing General Fund Support for CSAC Remains About Flat in 2023‑24

Spending by Program and Funding by Source (Dollars in Millions)

|

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

Change From 2022‑23 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Spending |

|||||

|

Local Assistance |

|||||

|

Cal Grants |

$2,233 |

$2,269 |

$2,259 |

‑$10 |

—a |

|

Middle Class Scholarships |

105 |

630 |

856b |

226 |

36% |

|

Learning‑Aligned Employment Programc |

200 |

300 |

— |

‑300 |

‑100 |

|

Golden State Teacher Grantsc |

56 |

147 |

49d |

‑98 |

‑67 |

|

Golden State Education and Training Grantsc |

95e |

— |

— |

— |

N/A |

|

Other programs |

38 |

46 |

38 |

‑7 |

‑16 |

|

Subtotals |

($2,727) |

($3,392) |

($3,203) |

(‑$190) |

(‑6%) |

|

State operations |

$23 |

$22 |

$34f |

$12 |

54% |

|

Totals |

$2,750 |

$3,414 |

$3,236 |

‑$178 |

‑5% |

|

Funding |

|||||

|

General Fund |

|||||

|

Ongoing |

$1,974 |

$2,538 |

$2,529 |

‑$9 |

—a |

|

One‑time |

354 |

455 |

286 |

‑169 |

‑37% |

|

Federal TANF |

400 |

400 |

400 |

— |

— |

|

Other funds and reimbursements |

22 |

21 |

21 |

—a |

—a |

|

aLess than $500,000 or 0.5 percent. bIncludes $226 million in one‑time funds. cOne‑time initiatives. dThe administration intends to correct this to $98 million at the May Revision. eIn addition to the $95.3 million provided in local assistance grants, $4.7 million is included in state operations for this program. fIncludes $10.2 million in carryover funds for administration of certain multiyear initiatives. |

|||||

|

CSAC = California Student Aid Commission and TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. |

|||||

Governor’s Budget Reflects Several Changes to CSAC Spending. Figure 2 shows the ongoing and one‑time spending changes proposed for CSAC in 2023‑24. The largest ongoing change is a baseline adjustment for Cal Grants, reflecting the most recent program estimates. The largest one‑time change is an augmentation for MCS consistent with last year’s budget agreement. The Governor also has a few state operations proposals for CSAC. In addition to the 2023‑24 changes shown in the figure, the Governor has a proposed budget solution to delay $400 million General Fund for Golden State Education and Training Grants from 2021‑22 to the out‑years. Though not affecting program funds, the Governor also has a trailer bill proposal to expand eligibility for Golden State Teacher Grants.

Figure 2

Largest CSAC Spending Changes Are One Time

General Fund Changes, 2023‑24 (In Millions)

|

Ongoing Spending |

|

|

Cal Grant baseline adjustments |

‑$10 |

|

State operations augmentations |

1 |

|

Other financial aid program adjustments |

—a |

|

Subtotal |

(‑$9) |

|

One‑Time Initiatives |

|

|

Middle Class Scholarship augmentation |

$226b |

|

Golden State Teacher Grants |

49c |

|

State operations augmentations |

1 |

|

Subtotal |

($276) |

|

Other One‑Time Adjustments |

|

|

Remove 2022‑23 one‑time funding |

‑$455 |

|

Carryover funds |

10 |

|

Subtotal |

(‑$444) |

|

Total |

‑$178 |

|

aLess than $500,000. bThe 2022‑23 budget agreement included intent to provide these funds. cThe 2021‑22 Budget Act appropriated a total of $500 million to be spread out evenly from 2021‑22 through 2025‑26. The amount shown reflects anticipated spending in 2023‑24. The administration intends to correct this to $98 million at the May Revision to align with program estimates. |

|

|

CSAC = California Student Aid Commission. |

|

Cal Grants

In this section, we begin by covering the state’s current Cal Grant program. Then, we discuss the potential implementation of Cal Grant reform in 2024‑25.

Current Cal Grant Program

Below, we first provide background on the current Cal Grant program and then discuss cost estimates for this program under the Governor’s budget.

Background

Cal Grant Program Is the State’s Largest Financial Aid Program. The Cal Grant program is intended to help students with financial need cover college costs. The program offers multiple types of Cal Grant awards. As Figure 3 on the next page shows, the amount of aid students receive depends on their award type and the segment of higher education they attend. Cal Grant A covers full systemwide tuition and fees at public universities and a fixed amount of tuition at private universities. Cal Grant B provides the same amount of tuition coverage as Cal Grant A in most cases, while also providing an “access award” for nontuition expenses such as food and housing. Cal Grant C, which is only available to students enrolled in career technical education programs, provides lower award amounts for tuition and nontuition expenses. Across all award types, larger amounts of nontuition coverage are available to students with dependent children as well as current and former foster youth.

Figure 3

Cal Grant Amounts Vary by Award Type,

Sector, and Student Characteristics

Maximum Annual Award Amount, 2022‑23

|

Amount |

|

|

Tuition Coverage |

|

|

Cal Grant A and Ba |

|

|

UC |

$13,104b |

|

Nonprofit institutions |

9,358 |

|

WASC‑accredited, for‑profit institutions |

8,056 |

|

CSU |

5,742 |

|

Other for‑profit institutions |

4,000 |

|

Cal Grant C |

|

|

Private institutions |

$2,462 |

|

Nontuition Coverage |

|

|

Cal Grant A |

|

|

Students with dependent childrenc |

$6,000 |

|

Foster youthc |

6,000 |

|

Cal Grant B |

|

|

Students with dependent childrenc |

$6,000 |

|

Foster youthc |

6,000 |

|

All other students |

1,648 |

|

Cal Grant C |

|

|

Students with dependent childrenc |

$4,000 |

|

Foster youthc |

4,000 |

|

Other CCC students |

1,094 |

|

Other private‑institution students |

547 |

|

aCal Grant B recipients generally do not receive tuition coverage in their first year. bReflects award amount for new UC students. Award amounts for continuing students are based on the tuition levels set in the year the student first enrolled at UC. cStudents attending private for‑profit institutions are ineligible for these awards. |

|

|

WASC = Western Association of Schools and Colleges. |

|

Cal Grants Have Financial and Academic Eligibility Criteria. To qualify for Cal Grants, students must meet certain income and asset criteria. These criteria vary by family size and are adjusted annually for inflation. For example, in the 2022‑23 award year, a dependent student from a family of four must have an annual household income of under $116,800 to qualify for Cal Grant A or C, and under $61,400 to qualify for Cal Grant B. In most cases, students must also meet a grade point average (GPA) requirement. The specific GPA requirement varies by award type. Most award types require a minimum high school GPA of 2.0 or 3.0 or a minimum community college GPA of 2.0 or 2.4.

Most Cal Grants Are Entitlements, but Some Are Awarded Competitively. For more than 20 years, the state has provided Cal Grants as entitlements to recent high school graduates as well as transfer students under age 28. In 2021‑22, the state also began providing Cal Grants as entitlements to community college students regardless of their age and time out of high school. The state currently provides approximately 140,000 new entitlement awards annually. The state also provides a limited number of competitive awards (13,000 new awards annually) to students who do not qualify for an entitlement award—typically older students attending four‑year universities. Students generally may renew their Cal Grant awards for four years of full‑time study (or the equivalent).

Cost Estimates

Governor’s Budget Reflects Large Downward Adjustment to 2022‑23 Cal Grant Spending. From the 2022‑23 Budget Act level, the Governor’s budget revises current‑year Cal Grant spending down by $210 million (8.5 percent) to align with CSAC’s most recent cost estimates. As Figure 4 shows, spending is adjusted downward across all the higher education segments. The largest adjustment (in dollar terms) is at the California State University (CSU), consistent with the enrollment declines that segment is experiencing in 2022‑23. The next largest adjustment is at the California Community Colleges (CCC). The CCC adjustment is primarily attributable to community college entitlement awards. Since the state began providing those awards in 2021‑22, costs have been notably lower than expected, reflecting depressed CCC enrollment levels and low paid rates. (Across all segments—and especially at CCC—some students who are initially offered awards are not paid for various reasons, such as deciding not to enroll, no longer meeting eligibility requirements, or administrative barriers.)

Figure 4

2022‑23 Cal Grant Spending Is Adjusted Downward at All Segments

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2022‑23 |

2022‑23 |

Change |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

UC |

$1,011 |

$986 |

‑$24 |

‑2% |

|

CSU |

829 |

764 |

‑65 |

‑8 |

|

CCC |

307 |

255 |

‑53 |

‑17 |

|

Private nonprofit |

251 |

235 |

‑17 |

‑7 |

|

Private for‑profit |

31 |

29 |

‑3 |

‑9 |

|

Othera |

49 |

— |

‑49 |

‑100 |

|

Totals |

$2,478 |

$2,268 |

‑$210 |

‑8% |

|

aThe 2022‑23 Budget Act provided $49 million on top of baseline estimates to account for more students potentially returning to college following recent enrollment declines. It did not specify how these costs would be distributed by segment. The Governor’s budget removes these funds to align with the most recent cost estimates. |

||||

Governor’s Budget Reflects Small Spending Decrease in 2023‑24. From the revised 2022‑23 spending level, the Governor’s budget further decreases Cal Grant spending by $9.5 million (0.4 percent) in 2023‑24 to align with CSAC’s cost estimates. We summarize the projected changes by segment and award type in our Cal Grant Spending and Cal Grant Recipients tables. The lower spending reflects a projected decline in renewal recipients in 2023‑24. This decline, however, is largely offset by an assumed increase in new recipients. The cost estimates also reflect higher tuition award amounts for the two most recent cohorts of University of California (UC) recipients, accounting for an estimated $46 million in additional Cal Grant costs in 2023‑24.

Cost Estimates Will Be Updated at May Revision. The Cal Grant cost estimates underlying the Governor’s budget were prepared by CSAC in October. We believe the estimates for 2022‑23 and 2023‑24 are reasonable based on the information available at that time. In the spring, CSAC will update its estimates based on more recent program data. Among other changes, this will include an adjustment to reflect that UC has adopted higher systemwide charges than originally assumed—$13,752 instead of $13,628. The administration is expected to update its Cal Grant spending levels at the May Revision accordingly.

Cal Grant Reform

Below, we first provide background on the Cal Grant reform provisions in the 2022‑23 budget agreement. Then, we provide an update on Cal Grant reform under the Governor’s budget, assess the implications, and make associated recommendations.

Background

State Might Restructure Cal Grant Program in 2024‑25, Subject to Trigger Provision. In the 2022‑23 budget package, the state adopted new rules for the Cal Grant program that would become operative in 2024‑25 only if certain conditions are met. Specifically, the new program—commonly referred to as Cal Grant reform—would be triggered on if the state (1) determines in spring 2024 that sufficient General Fund is available to support the program changes and (2) enacts future legislation providing a corresponding appropriation. (This trigger is separate from the trigger restoration proposed in the Governor’s budget as part of his approach to addressing the state’s budget problem.) Under the new program, the existing Cal Grant award types are replaced with a Cal Grant 2 award that provides nontuition coverage to community college students and a Cal Grant 4 award that provides tuition coverage at all other segments. All awards under the new program would be provided to eligible recipients as entitlements, with no awards offered on a competitive basis. The new rules would apply to all new applicants for Cal Grant awards beginning in 2024‑25, with renewal applicants continuing to receive awards under the current rules. The changes are estimated to increase net Cal Grant costs by $365 million in 2024‑25.

Cal Grant Reform Involves Several Key Eligibility Changes. The eligibility requirements of the new Cal Grant program differ in several ways from those of the current program. First, whereas the current program has its own income and asset ceilings, the new program has the same income ceilings as the federal Pell Grant program is to have beginning in 2024‑25. The new Cal Grant income ceilings generally are lower than the current ones. (For example, the income ceiling for a dependent student with married parents in a family of four under the new program is expected to be approximately $76,300 in 2024‑25.) Second, whereas the current program provides only a limited number of awards to older students attending the universities, the new program has no restrictions related to age or time out of high school at any segment. Third, whereas the current program generally requires students to have a minimum GPA, the new program does not have a GPA requirement for community college students. If the new program is triggered, these changes are expected to lead to a net increase of 150,000 award offers in 2024‑25.

Cal Grant Reform Also Involves Changes to Award Amounts and Coverage. For Cal Grant recipients attending community colleges, the new program initially provides the same award amounts (a $1,648 access award for nontuition expenses) as the current program. Under the new program, however, these award amounts will be adjusted annually for inflation. For Cal Grant recipients attending universities, the new program involves more immediate changes to award amounts and coverage. Whereas some first‑year university recipients do not receive tuition coverage under the current program, all university recipients receive tuition coverage under the new program. No university recipients in the new program, however, receive Cal Grant nontuition coverage. The segments are instead expected to provide nontuition coverage through their institutional aid programs. This policy change is substantial as roughly half of university recipients receive nontuition coverage under the current Cal Grant program.

Proposal

Governor Proposes No Changes to Cal Grant Reform Provisions. The Governor’s budget does not include any changes to the Cal Grant reform provisions included in last year’s budget agreement. Consistent with that agreement, the new program would be triggered on in 2024‑25 only if sufficient General Fund is available to support the action over the next several years.

Assessment

State Budget Condition Has Changed Since Last Year’s Agreement. When it enacted the 2022‑23 Budget Act, the state had a notable surplus. Even at that time, however, the state did not know whether it would be able to support certain program expansions in the out‑years. As a result, the state tied these program expansions to trigger language. As we discuss in The 2023‑24 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, the state now faces a budget problem. Moreover, under the Governor’s budget, the state faces operating deficits in the out‑years (2024‑25 through 2026‑27). Based on our budget projections, Cal Grant reform is very unlikely to be triggered.

Trigger Creates Significant Timing Problem Within Admissions Process. Campuses generally aim to send financial aid offer letters to students shortly after they are admitted. This allows students and their families to consider the amount of financial aid they will receive when deciding whether to go to college and which institution to attend. Students considering four‑year universities often must make these decisions by May 1 of the preceding academic year, as this is traditionally the national deadline to accept admissions offers at selective institutions. Under the trailer legislation adopted last year, the state will determine in spring 2024 whether Cal Grant reform is triggered. The legislation does not specify an exact date for the determination, but the state often waits until after the May Revision is released in mid‑May to make key budget decisions. This means that campuses likely would not know whether Cal Grant reform has been triggered when they begin sending financial aid offer letters to students and their families for 2024‑25.

Some Students Are Likely Not to Receive Accurate Award Information on Time. Until the Cal Grant reform trigger is determined, campuses will not be able to determine which students are eligible for awards and what award amounts they will receive in 2024‑25. This will make it difficult for campuses to provide clear and accurate information on financial aid offers to students and their families. Some students will likely need to make enrollment decisions based on financial aid offers that could change in the coming weeks, depending on the trigger determination. This is particularly problematic for students who would lose eligibility or receive smaller awards under Cal Grant reform. These students might end up receiving less financial aid than they had expected at the time of their enrollment decision, if their campus cannot cover the difference with institutional aid or other sources.

Trigger Creates Administrative Challenges for CSAC and Campuses. Until the trigger is determined, both CSAC and campus financial aid offices need to be prepared to administer either version of the Cal Grant program in 2024‑25. For example, they will need to implement the new rules in the software they use to administer financial aid programs, while also keeping the current rules available. Campuses vary in their capacity to implement these changes. At the community colleges, for example, campuses have different information technology systems and different financial aid staffing levels. Any administrative challenges at CSAC or the campuses could lead to delays in making award decisions and disbursing awards to students.

Recommendations

Determine Now Whether to Proceed With Cal Grant Reform. Under the budget provisions adopted last year, Cal Grant reform is very unlikely to be triggered in 2024‑25. Moreover, even if Cal Grant reform were triggered, the timing of that determination could significantly undermine the program’s effectiveness in the first year. In light of these factors, we recommend the Legislature revisit the trigger. Rather than subjecting Cal Grant reform to a spring 2024 trigger determination, we recommend the Legislature instead determine during this year’s budget process whether to proceed with Cal Grant reform in 2024‑25. Making this determination one year in advance would allow the state to send a clearer message to students and their families about the financial aid available to them. It would also give CSAC and the segments more time to implement any changes effectively, reducing potential delays in making award decisions and disbursing awards to students. Given the state budget condition, proceeding with Cal Grant reform in 2024‑25 would involve difficult trade‑offs. If the Legislature decides to support Cal Grant reform beginning in 2024‑25, it likely would need to redirect funds (an estimated $365 million) from other ongoing purposes to avoid exacerbating the state’s projected out‑year operating deficits.

Consider Cal Grant Reform Together With Other Potential Financial Aid Expansions. The Legislature has multiple options for expanding financial aid. For example, it could increase Cal Grant access awards in addition to or in place of implementing Cal Grant reform. It also could expand the MCS program, which we discuss in the next section. These options would result in certain students receiving more assistance with their living costs, which has been a legislative priority over the past few years. Whether the Legislature decides to proceed with financial aid expansion in the near term or wait until the state budget condition improves, we encourage it to weigh these various options before deciding which approach to pursue. Notably, the various options impact different groups of students and have different associated costs. For example, implementing Cal Grant reform is projected to benefit more low‑income students, older students, and community college students relative to the current program. The various options also interact with one another. For example, implementing Cal Grant reform would change the number of access award recipients and thus the cost of increasing those awards. Any Cal Grant augmentations at UC and CSU also would reduce the cost of the MCS program at full implementation.

Middle Class Scholarships

In this section, we provide background on the MCS program, describe the one‑time augmentation for the program under the Governor’s budget, assess the proposed approach, and make an associated recommendation.

Background

State Recently Revamped MCS Program. The state created the original MCS program in the 2013‑14 budget package to provide partial tuition coverage to certain UC and CSU students. Originally, MCS awards were for students who were not receiving tuition coverage through the Cal Grant program or other need‑based financial aid programs. In the 2021‑22 budget package, the state adopted a plan to revamp the MCS program to focus on total cost of attendance rather than tuition only. Under the revamped program, students may use MCS awards for nontuition expenses, such as housing and food. The state is implementing the revamped program for the first time in 2022‑23.

Award Amounts Are Now Calculated Based on a Multicomponent Formula. As Figure 5 shows, calculating a student’s award amount under the revamped program involves several steps. First, CSAC accounts for other available gift aid, a student contribution from part‑time work earnings, and parent contribution for dependent students with a household income of over $100,000. It then deducts these amounts from the student’s total cost of attendance to determine whether the student has remaining costs. Finally, it determines what percentage of each student’s remaining costs to cover based on the annual state appropriation for the program. Under this formula, award amounts vary widely among students, with each student’s award reflecting their costs and available resources.

Figure 5

Middle Class Scholarships Are Calculated Using Multicomponent Formula

Illustrative CSU Dependent Students Living Off Campus, 2022‑23

|

Household Income |

Example 1 |

Example 2 |

|

Cost of attendance |

$30,380 |

$30,380 |

|

Other federal, state, and institutional gift aida |

‑11,035 |

— |

|

Student contribution from work earnings |

‑7,898 |

‑7,898 |

|

33% of parent contribution from federal EFCb |

— |

‑8,528 |

|

Student’s Remaining Costs |

$11,447 |

$13,954 |

|

Percentage based on annual appropriationc |

26% |

26% |

|

Award Amounts |

$2,976 |

$3,628 |

|

aThe amount also includes any private scholarships in excess of the sum of the student contribution and parent contribution. bOnly applies to dependent students with a household income of more than $100,000. cState law requires CSAC to determine what percentage of each student’s remaining costs to cover each year based on the annual appropriation for the program. Under CSAC’s most recent estimates, the program is estimated to cover 26 percent of each student’s remaining costs in 2022‑23. |

||

|

EFC = expected family contribution and CSAC = California Student Aid Commission. |

||

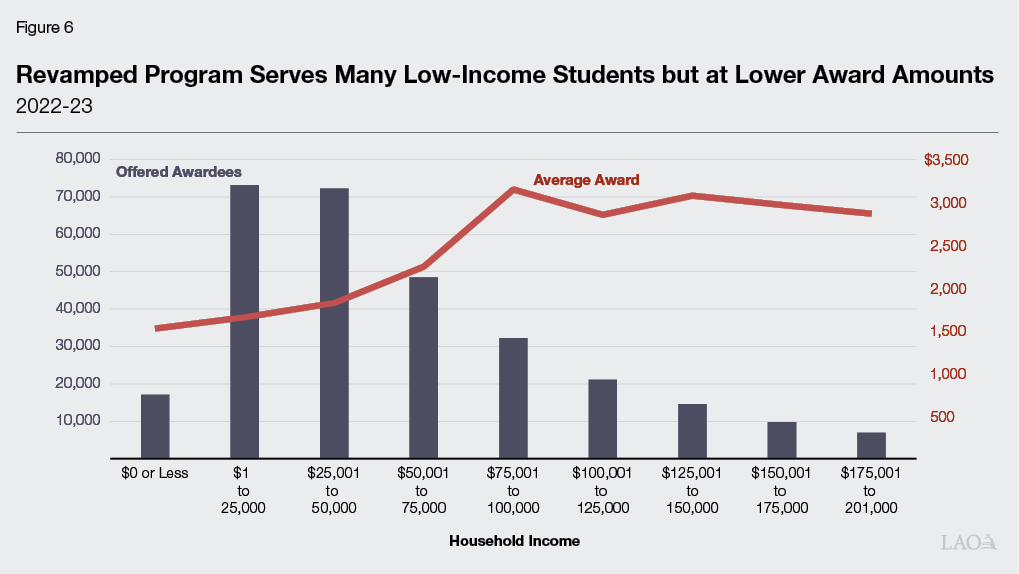

Revamped Program Serves Broader Group of Students. The revamped MCS program generally maintains the income and asset ceilings of the original program, adjusted for inflation. The maximum annual household income to qualify for an MCS award is $201,000 for dependent students in 2022‑23. However, the program is now serving considerably more low‑income students than before. This is because students receiving tuition coverage through Cal Grants or other financial aid programs are newly eligible for MCS awards to help cover nontuition expenses under the revamped program. As Figure 6 shows, more than half of students offered MCS awards in 2022‑23 have a household income of $50,000 or less, and more than 80 percent have a household income of $100,000 or less. Students with lower household incomes, however, receive smaller MCS awards on average because they tend to receive more gift aid from other programs (such as Cal Grants, Pell Grants, and institutional aid).

Current Funding Covers About One‑Quarter of Full Implementation Costs. Last year, CSAC estimated it would cost $2.6 billion to cover 100 percent of each student’s remaining costs under the MCS formula. The 2022‑23 Budget Act provided $632 million ongoing General Fund to cover an estimated 24 percent of each student’s remaining costs. The budget agreement also included intent to provide $227 million one‑time General Fund in 2023‑24 to increase coverage to 33 percent of each student’s remaining costs in that year.

Proposal

Governor’s Budget Provides One‑Time Augmentation for MCS Program. The Governor’s budget first adjusts MCS spending to $630 million ongoing General Fund in 2022‑23 to align with CSAC’s most recent cost estimates, which indicate program funding is sufficient to cover 26 percent of each student’s remaining costs. This is the maximum coverage possible without going over the amount appropriated in the 2022‑23 Budget Act. Then, consistent with last year’s agreement, the Governor’s budget provides $226 million one‑time General Fund to increase program funding to $856 million in 2023‑24. Based on CSAC’s cost estimates, the proposed funding level would be sufficient to cover the intended 33 percent of each student’s remaining costs. Figure 7 shows CSAC’s estimate of recipients, spending, and average awards by segment under the Governor’s budget.

Figure 7

Proposed Augmentation Would Increase MCS Average Award Notably

Key Information by Segmenta

|

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

Change From 2022‑23 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Recipients |

|||||

|

CSU |

44,481 |

184,240 |

197,137 |

12,897 |

7% |

|

UC |

10,511 |

88,200 |

94,374 |

6,174 |

7 |

|

Totals |

54,992 |

272,440 |

291,511 |

19,071 |

7% |

|

Spending (in Millions) |

|||||

|

CSU |

$74 |

$447 |

$608 |

$160 |

36% |

|

UC |

32 |

183 |

248 |

66 |

36 |

|

Totals |

$105 |

$630 |

$856 |

$226 |

36% |

|

Average Award |

|||||

|

CSU |

$1,654 |

$2,429 |

$3,083 |

$654 |

27% |

|

UC |

3,015 |

2,074 |

2,633 |

558 |

27 |

|

aData reflect California Student Aid Commission (CSAC) estimates. |

|||||

|

bThe Middle Class Scholarship (MCS) program was revamped beginning in 2022‑23, with the new rules significantly affecting the number of eligible recipients and award amounts. |

|||||

Assessment

MCS Implementation Challenges Have Impacted Program Effectiveness in 2022‑23. As CSAC and campus financial aid offices implemented the revamped MCS program for the first time this year, several challenges emerged. In spring 2022, while students were considering their admissions offers, CSAC did not have the necessary data to estimate MCS award amounts under the new formula. As a result, students and families were not notified of their award amounts in time for it to influence their enrollment decisions or their financial planning around covering college costs. (CSAC did, however, send a general notification to students considering a UC or CSU campus to inform them of their potential eligibility for an MCS award.) After CSAC began processing award offers in September, further delays affected when students received payments. For example, the segments needed time to implement changes to the software their campuses use to administer financial aid programs. UC reports its campuses disbursed fall‑term awards from October through December, while CSU reports its campuses disbursed fall‑term awards the following January. As a result of this timing, the awards were not yet available as students and families began incurring costs for the fall term.

Implementation Could Go More Smoothly in 2023‑24, but Some Challenges Remain. Some of the MCS implementation challenges that CSAC and campus financial aid offices experienced in 2022‑23 are expected to ease with time. For example, the disbursement process will likely go faster next year, now that the segments have made the necessary changes in their financial aid management software. However, CSAC and the segments indicate that other challenges could persist under the current program structure. One notable challenge is that MCS award amounts often need to be adjusted throughout the year. These adjustments may happen for various reasons, including to reflect any new gift aid a student receives (such as merit scholarships or emergency grants), to comply with certain federal financial aid packaging requirements, or to keep MCS spending within the annual appropriation. These adjustments create significant workload for CSAC and campus financial aid offices. Moreover, they create frustration and potential hardship among students, particularly when award amounts are reduced partway through the year. CSAC and the segments are exploring legislative changes to simplify program administration.

One‑Time MCS Augmentation Has Key Drawbacks for Students. Though the proposed one‑time MCS augmentation would help those college students enrolled in 2023‑24 cover a portion of their cost of attendance, using one‑time funds for ongoing grant programs has key drawbacks. For students and their families, receiving a certain amount of aid in one year can create an expectation of receiving a similar amount in future years. With the one‑time MCS augmentation, however, students would receive more aid in 2023‑24 only to have their award amounts decrease when the funds are removed the following year. This arrangement could create an unexpected financial strain for continuing students in 2024‑25. Using one‑time funds for a temporary increase in aid also creates inequities among student cohorts, with incoming students in 2024‑25 receiving less aid than the students before them.

One‑Time MCS Augmentation Also Will Create Out‑Year State Cost Pressures. To avoid reducing aid for students, the state likely would face significant pressure to retain the higher award levels in 2024‑25. This could lead to difficult trade‑offs, particularly as the state is facing a projected operating deficit that year. These trade‑offs could be heightened because the Legislature is also interested in implementing a significant expansion to the Cal Grant program in that year.

Recommendation

If Expanding MCS Program, Adopt Ongoing Funding. As we discuss in the “Cal Grants” section of this brief, we recommend the Legislature first weigh all its options for expanding student financial aid—across both the Cal Grant and MCS programs. If the Legislature chooses to proceed with expanding the MCS program, we recommend it designate ongoing funding for this purpose. Compared to the one‑time funding included in the Governor’s budget, ongoing funding would provide greater certainty to students and families about the financial aid available to them, while also better reflecting the cost pressures associated with expanding aid in any given year. Given the state budget condition, however, increasing ongoing MCS funding in 2023‑24 would involve difficult trade‑offs. To avoid exacerbating the state’s projected out‑year operating deficits, the Legislature would likely need to redirect funds from other ongoing purposes to support any ongoing MCS expansion. In the meantime, we recommend the Legislature reject the $226 million in one‑time MCS funding and count this toward its budget solutions in 2023‑24.

Golden State Education and Training Grants

In this section, we provide background on the Golden State Education and Training Grant program, describe the Governor’s proposal to delay funding for this program, assess that proposal, and provide an associated recommendation.

Background

State Has Extensive Workforce Development System. California’s public higher education segments are part of this system. The community colleges provide workforce education and training as part of their primary mission, while the universities also provide programs that prepare students for careers. Outside of higher education, many other state and local agencies also provide services to job seekers. Notably, under the federal Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), California has a network of local workforce development boards. These boards operate one‑stop centers providing various job services, including training benefits. The state maintains a list of where workers may use these WIOA‑funded training benefits, called the Eligible Training Provider List (ETPL). In addition to public higher education institutions, the ETPL includes various other providers, such as private career colleges, adult schools, and trade associations.

State Created New CSAC Program to Help Workers Displaced by Pandemic. The 2021‑22 budget package created the Golden State Education and Training Grant program at CSAC. The program provides one‑time grants of up to $2,500 to individuals who lost employment due to the pandemic and were not already enrolled in an education or training program. To qualify for the program, individuals must meet the income and asset criteria associated with a Cal Grant A award. (For example, in 2022‑23, the income ceilings are $42,800 for a single independent student and $116,800 for a student in a family of four.) The program is intended to help grant recipients cover the cost of enrolling at CCC, CSU, or UC or obtaining training from another provider on the ETPL that meets certain performance outcomes. Specifically, other providers on the ETPL must demonstrate that the majority of training participants have obtained living‑wage employment within one year of program completion.

Program Is Supported by One‑Time General Fund. The 2021‑22 Budget Act provided $500 million one time for the program, initially consisting of $472.5 million federal American Rescue Plan Act funds and $27.5 million General Fund. However, the 2022‑23 Budget Act authorized the administration to swap the federal funds for General Fund, bringing the General Fund amount to $500 million. This fund swap was intended to maximize flexibility in program administration and reporting. Current law requires CSAC to report to the Legislature by December 31, 2023 on the number of grants provided under the program.

Proposal

Governor Proposes Delaying Bulk of Program Funding. As a budget solution, the Governor proposes to delay $400 million of the $500 million in program funding from 2021‑22 to later years. Specifically, the Governor proposes to provide $200 million in 2024‑25, $100 million in 2025‑26, and $100 million in 2026‑27. The administration suggests this budget approach aligns more closely with the actual pace of program spending. The administration does not expect the proposal to have any programmatic impact. Given that program spending would continue through 2026‑27, the Governor also proposes trailer bill language changing the deadline for CSAC to report on grants from December 31, 2023 to September 30, 2027.

Assessment

Proposed Approach Contributes to State’s Out‑Year Budget Deficits. Although the Governor’s proposed budget solution reduces near‑term spending by $400 million General Fund, it does so by shifting those costs into the out‑years. In doing so, it contributes to projected operating deficits in 2024‑25 through 2026‑27. As a result, the state would need to find additional solutions to balance the budget in those years.

Underlying Need for Program Has Diminished. The state created the Golden State Education and Training Grant program to address a spike in job losses during the pandemic. Many of these job losses were in close‑contact industries—such as personal care services, accommodations and food services, and entertainment and recreation—that tend to employ workers with lower education levels. The program was intended to help these displaced workers pursue additional education and training. Since the height of the pandemic, however, the labor market has improved significantly. Whereas the state unemployment rate peaked at 16 percent in May 2020, it is down to 4.1 percent as of December 2022. This is comparable to pre‑pandemic lows. Moreover, because the labor market has been very favorable for people looking for jobs, displaced workers are more likely to have the option to find other jobs rather than returning to school. (The tight labor market has been a key factor contributing to steep declines in community college enrollment over the past couple of years.)

Program Is Reaching Far Fewer Recipients Than Intended. Of the $500 million initially appropriated for the program, $485 million was reserved for grants (with the remainder for program administration and outreach). The $485 million is sufficient to provide grants to 194,000 recipients, assuming each recipient gets the maximum grant. As of January 2023, only about 5,000 recipients had received grants at a total cost of $12.5 million (2.6 percent of the available funding).

Other Programs Are Available to Support Training for Displaced Workers. Separate from this program, displaced workers have various other options for affordable education or training. Community colleges provide noncredit adult education courses at no charge, while also providing full tuition waivers for students with financial need to take credit courses. Many students with financial need are also eligible for federal and state financial aid—including Pell Grants and Cal Grants—to help with their education and living costs. Notably, Cal Grant C awards are available in career technical education programs as short as four months. Individuals can also access federally funded job services, including training from providers on the ETPL, through one‑stop job centers.

Program Has Been Costly to Administer. CSAC has incurred relatively high start‑up costs for this program. As of January 2023, CSAC had encumbered or spent $7.2 million for program administration and marketing, with the majority going toward an external contract to promote the program to prospective applicants. While these administrative costs remain within the statutory allowance ($15 million), they account for over one‑third of total program spending to date. The program’s high administrative costs are partly because CSAC is working with a new set of potential beneficiaries—specifically, displaced workers not yet connected to higher education. As a result, CSAC is spending a relatively high amount for marketing. In addition, administrative costs are high because CSAC is required to work with a new set of training providers—specifically, ETPL providers that are ineligible for the traditional financial aid programs that CSAC administers. CSAC has dedicated staff time to establishing processes for working with these providers for the first time.

Recommendation

As Budget Solution, Recommend Discontinuing Program and Removing Remaining Funds. Given the above considerations, we recommend the Legislature discontinue the Golden State Education and Training Grant program at the end of the current year and remove any remaining funding at that time. Based on program spending to date, we estimate roughly $470 million in one‑time General Fund would remain unspent at the end of 2022‑23. Removing these funds would provide an estimated $70 million in immediate solution beyond the Governor’s budget. It would also reduce spending by an additional $400 million in the out‑years, thereby improving the state’s out‑year budget condition. Under this approach, the Legislature could retain the reporting deadline relating to the number of grants awarded that is in current law (December 31, 2023), as the program would end prior to that date.

Golden State Teacher Grants

In this section, we provide background on the Golden State Teacher Grant program, describe the Governor’s proposed trailer bill language making various changes to the program, assess those changes, and provide associated recommendations.

Background

California Has Teacher Shortages in Certain Subject Areas and Schools. Over the years, some school districts have experienced challenges finding credentialed teachers. These challenges have been concentrated in certain subject areas and schools. The state has identified persistent teacher shortages in special education, science, and math. Additionally, urban schools and rural schools in low‑income areas tend to experience greater difficulties with staffing and are more likely than other schools to hire underprepared teachers. Although these challenges are long‑standing, teacher shortages have worsened since the start of the pandemic, which prompted teachers to leave the workforce at accelerated rates.

State Recently Created Grant Program for Prospective Teachers. In the 2019‑20 budget package, the state created the Golden State Teacher Grant program administered by CSAC. This is one of several initiatives the state created in recent years to address teacher shortages. The program provides grants of up to $20,000 to students in professional preparation programs leading to preliminary teaching credentials who commit to a certain service requirement. Under current law, the service requirement involves working for four years at a “priority school”—defined as a school where at least 55 percent of students are low‑income, English learners, or foster youth. Originally, recipients were also required to commit to teaching in certain subject areas—special education; science, technology, engineering, and math; bilingual education; elementary school; and transitional kindergarten (TK). However, the 2022‑23 budget package expanded eligibility to recipients who agree to teach in any subject area. It also expanded eligibility to recipients pursuing a pupil personnel services credential, such as school counseling, social work, or school psychology. In contrast to most other state financial aid programs, this program does not have financial eligibility criteria (such as an income ceiling).

State Appropriated Five Years of Program Funding in 2021‑22. Although the program was created in 2019‑20, the original appropriation was rescinded in 2020‑21 to address a projected budget deficit stemming from the pandemic. In that year, the state provided a small amount of federal funding for a narrower version of the program focused on special education. Then, in 2021‑22, the state provided $500 million one‑time General Fund for the program. Trailer legislation authorized CSAC to spend $7.5 million (1.5 percent) of these funds on program administration. The remaining amount was to be spread evenly over five years, equating to approximately $98 million annually through 2025‑26.

State Is Expanding Early Education Programs. The 2021‑22 budget agreement included plans to gradually expand TK to all four‑year olds. This expansion will result in greater demand for early educators. The state requires early educators to meet certain qualifications. Many positions, including in the State Preschool program, require a child development permit. The state offers six types of child development permits, ranging from assistant permit (requiring six units of relevant coursework) to program director permit (requiring a bachelor’s degree or higher). Beginning in August 2023, TK teachers also must have at least 24 units of child development coursework or a child development permit, in addition to the current requirements of a bachelor’s degree and elementary school teaching credential. In 2021‑22, the state provided $100 million one‑time Proposition 98 General Fund to increase the number of highly qualified State Preschool and TK teachers.

Proposal

Governor Proposes Changing Service Requirement for Grant Recipients. The proposed trailer bill language would make two changes to the current requirement for Golden State Teacher Grant recipients to commit to working for four years at a priority school. First, it would allow recipients to instead commit to working for four years at any school, beyond only priority schools. Second, for recipients who still choose to work at a priority school, the proposed language would reduce the length of their service requirement from four years to three years. The administration indicates these changes are intended to ensure sufficient demand for the program, while also maintaining some incentive for grant recipients to teach at a priority school.

Governor Proposes Expanding Eligibility to Certain Child Development Permits. The proposed trailer bill language would also expand program eligibility to students pursuing certain child development permits—specifically for master teachers, site supervisors, and program directors. These permits are required for nonentry‑level, supervisory positions within State Preschool. To qualify for a grant, students pursuing these permits must be concurrently pursuing a bachelor’s degree. (Students pursuing required coursework or child development permits for assistants, associate teachers, and teachers would remain ineligible for grants.) Grant recipients could complete their associated service requirement at any elementary school or at a state or federally funded preschool program. The administration indicates these changes are intended to address early educator workforce needs.

Assessment

Program Demand Is Robust Under Current Eligibility Requirements. In 2021‑22 (the first of the five years covered by the General Fund appropriation), CSAC spent only $42 million of the $98 million available for grants. Program demand, however, has increased notably following the significant eligibility expansions enacted in the 2022‑23 budget package. In 2022‑23, CSAC has spent $90 million on grants as of January. Given CSAC will continue to receive applications and process payments in the coming months, it is likely to spend not only the $98 million available for grants in 2022‑23, but also some or all of the remaining funds from 2021‑22. CSAC further projects that it will fully spend the $500 million allocation before the end of the five‑year period. This suggests no further eligibility expansions are needed to ensure sufficient demand for the program. Moreover, further eligibility expansions could lead demand to exceed available funding. The proposed trailer bill language does not specify how CSAC is to prioritize among applicants in this event.

Proposed Changes Would Likely Reduce Benefits to Priority Schools. The current service requirement is designed to address the disproportionate staffing challenges at priority schools. The proposed trailer bill language would reduce the program’s effectiveness in meeting this objective in two ways. First, it would reduce the number of years that recipients are expected to work at a priority school from four years to three years. Second, it would allow recipients to instead complete their service requirement at a school that is not on the priority list. To the extent that recipients choose this option, the program’s benefits would be redistributed from priority schools to higher‑income schools that have less acute staffing challenges. Although the program might still support the expansion of the teacher workforce overall, its impact would not be as targeted toward the areas of greatest need.

Proposed Changes Do Not Effectively Address Early Educator Workforce Needs. Though school districts will need more early educators over the next few years, the Governor’s proposed trailer bill language is not likely to be an effective way to address this objective. The proposed requirement that recipients concurrently pursue a bachelor’s degree with their permit would exclude current elementary school teachers returning to school to complete additional child development coursework necessary to teach in a TK classroom. The proposed language also excludes individuals seeking coursework and entry‑level child development permits to teach in State Preschool. More broadly, it is unclear what is the added value of this proposal relative to current early educator workforce programs that have less restrictive eligibility requirements. Those other programs could potentially be more effective ways to address the objective of expanding the early educator workforce.

Proposed Changes Could Make Program Costlier to Administer. The proposed program changes would have some administrative costs. CSAC would need to notify a new set of preparation programs that their students now qualify for grants. CSAC would also need to track grant recipients across a broader set of schools to monitor whether the service requirement was being met. Moreover, having two different lengths of service requirements (three years at a priority school versus four years at all other schools) could also increase monitoring costs. In addition, CSAC would need to implement the new grant rules in the software system it uses to administer financial aid programs. Although incurring additional administrative costs is sometimes necessary, higher administrative costs are harder to justify when proposed program changes are not warranted.

Recommendation

Reject Proposed Eligibility Expansion and Change to Service Requirement. Given the above considerations, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposed trailer bill language changing the Golden State Teacher Grant program eligibility and service requirement. Based on CSAC’s projections, demand likely is sufficient under the current program structure to fully spend grant funds by the expenditure deadline (and possibly sooner). Moreover, expanding the service requirement to include non‑priority schools undermines the primary program objective of supporting schools facing the most acute teacher shortages. The Governor’s proposal also is not well tailored to early educator workforce issues. A more direct approach would be to ask the California Department of Education for an update on the state’s recent initiative to increase the number of highly qualified State Preschool and TK teachers. To the extent this initiative is proving to be effective, the Legislature could increase funding for the initiative depending on its other budget priorities.

State Operations

In this section, we begin by providing background on CSAC’s state operations. We then assess the Governor’s proposed augmentations for human resources, cybersecurity, and high school toolkits. We end by discussing a state operations issue relating to Cal Grant reform implementation and other potential financial aid expansions.

Background

CSAC Is Mid‑Sized State Agency. Like other state agencies, CSAC spends a majority of its state operations budget on staffing. In 2022‑23, CSAC has 145.5 authorized permanent positions. These positions span eight divisions, the largest of which are Program Administration and Services, Information Technology Services, and Fiscal and Administrative Services. Since 2017‑18, the number of authorized permanent positions at CSAC has increased by 23 positions (19 percent). Most of the positions added over the past five years were to address increased workload linked to financial aid program expansions.

About 18 Percent of Positions Are Currently Vacant. As of January 2023, CSAC reports that 25.5 (18 percent) of its permanent positions were vacant. This is somewhat higher than the statewide average vacancy rate, which has ranged between 10 percent and 15 percent over the past decade. CSAC indicates that it is actively working to fill most of its vacant positions, with 19 of these positions in various stages of the recruitment and hiring process.

Human Resources

Governor’s Budget Funds One New Human Resources Position. The Governor’s budget provides $121,000 ongoing General Fund for one Associate Personnel Analyst position. The position would support recruitment, hiring, onboarding, and other human resources activities.

Proposed Human Resources Position Is Reasonable, Recommend Approving. In recent years, as CSAC’s overall staffing has expanded, its human resources workload has also grown. CSAC currently has five permanent positions in its human resources office. In 2021‑22, it worked with the Department of Finance to administratively establish an additional limited‑term position in its human resources office to address recruitment, hiring, onboarding, and other related needs linked to recent program expansions. The Governor’s proposal would effectively convert the limited‑term position into an ongoing one. CSAC has provided a reasonable list of job duties and associated workload justifying the proposed position. We recommend approving the position.

Cybersecurity

Governor’s Budget Funds Two New Cybersecurity Positions and Related Support. The Governor’s budget provides $469,000 ongoing General Fund and $962,000 one‑time General Fund to improve cybersecurity at CSAC. The ongoing funds are primarily for two Information Technology Specialist positions. The one‑time funds are primarily for consulting services to assess CSAC’s information technology systems for cybersecurity risks and develop a roadmap to address those risks. In addition, some ongoing and one‑time funds would go toward security software and training.

Proposed Cybersecurity Augmentations Are Reasonable, Recommend Approving. CSAC maintains a large and growing volume of sensitive data on students and their families. In recent years, CSAC’s cybersecurity needs have increased because of various factors, including updated state security standards, the migration of systems to the cloud, and the expansion of telework during the pandemic. Currently, CSAC has only one position dedicated to cybersecurity. The administration and CSAC have provided a reasonable list of job duties and associated workload justifying the two proposed positions. They also have provided a reasonable plan for the proposed one‑time funds. We recommend approving all components of the proposal.

High School Toolkits

Governor’s Budget Provides Ongoing Funding for High School Toolkits. The 2021‑22 budget package created a new requirement for school districts to verify that all high school seniors complete a college financial aid application, unless the student submits an opt‑out form or receives an exemption from the district. The Governor’s budget provides $120,000 ongoing General Fund to CSAC to distribute toolkits to high schools to support them in fulfilling the requirement. CSAC indicates these toolkits would include various materials that provide information on and promote awareness of student financial aid—including resource guides, posters, postcards, notepads, and stickers. CSAC intends to send these toolkits to high schools that have lower financial aid application completion rates.

State Recently Expanded CSAC’s High School Outreach Efforts. The 2022‑23 Budget Act provided several augmentations to CSAC to expand high school outreach around financial aid. First, it provided an increase of $2.4 million ongoing General Fund for the California Student Opportunity and Access Program (Cal‑SOAP), which provides financial aid information to low‑income middle school students and high school students. These funds are to support Cal‑SOAP activities in the Inland Empire. Second, it provided $500,000 one‑time General Fund to expand the Cash for College Program, which provides workshops to help students and their families complete financial aid applications. Third, it added three new positions at CSAC to support school districts in implementing the new financial aid application requirement.

State Is Also Funding Other High School Outreach Efforts. The 2022‑23 Budget Act also included augmentations for other agencies that could support the implementation of the new financial aid application requirement. Most notably, it provided $9.3 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund and $4.4 million one‑time Proposition 98 General Fund to the California Department of Education to support school districts’ participation in the California College Guidance Initiative (CCGI). This initiative provides online tools to help middle school students and high school students with various aspects of college planning, including the financial aid process. CCGI’s financial aid planning tool provides students with financial aid lessons and application assistance. (The Governor’s budget proposes an additional $3.9 million Proposition 98 General Fund to increase CCGI personnel and further support CCGI operations and ramp‑up activities.)

Proposed High School Toolkits Lack Strong Justification, Recommend Rejecting. As mentioned above, the state took several actions last year intended to help high schools in fulfilling the new financial aid application requirement. For example, school districts can already leverage the existing financial aid resources within CCGI to increase awareness of student financial aid opportunities and assist students with the application process. It is too soon to determine whether gaps or challenges remain for high schools. Moreover, the administration has not demonstrated that the proposed toolkits are likely to be an effective way to help high schools on an ongoing basis. The proposal also lacks key details, including the number of toolkits that could be provided at the proposed funding level. Based on these concerns, we recommend rejecting the Governor’s proposal to provide $120,000 ongoing General Fund for high school toolkits. The Legislature could reconsider this proposal in a future year if the administration were to return with stronger justification.

Cal Grant Reform Implementation

Governor’s Budget Includes Ongoing Funding for Cal Grant Reform Implementation. The state provided CSAC with $500,000 one‑time General Fund in 2022‑23 to begin implementing Cal Grant reform. The Governor’s budget does not remove these one‑time funds. The administration indicates it will determine at the May Revision whether to retain these funds on an ongoing basis to address CSAC’s workload needs.

Align Administrative Funding for CSAC With Program Expansions. As we discuss in the “Cal Grants” and “Middle Class Scholarships” sections of this brief, the Legislature faces key decisions about whether and how to proceed with financial aid program expansions in the near term. These decisions will in turn impact CSAC’s administrative workload. For example, if the Legislature decides to proceed with Cal Grant reform, then ongoing administrative funding for CSAC to implement the larger program could be warranted. On the other hand, if it decides not to proceed with Cal Grant reform given the state budget condition, then ongoing administrative funding would not be needed. We recommend withholding action on administrative funding for CSAC to implement financial aid expansions until later in the budget process, when decisions have been made about which, if any, expansions to pursue. At that time, the Legislature could align any administrative funding for CSAC with those program expansion decisions.