LAO Contact

February 27, 2023

Effect of Returning to

Historical Estimated Tax Payment Schedule

Background

Some Taxpayers Make Estimated Tax Payments Throughout the Year. State law requires taxpayers to pay income taxes as they earn income. Most taxpayers meet this requirement through income tax withholding that is taken out of their regular paycheck. Businesses and some individuals with significant capital gains or other nonwage income instead make quarterly estimated tax payments to meet this state requirement. This prepayment of corporate and personal income tax throughout the year improves compliance and helps align the timing of tax payments with earnings. For many years, the state directed taxpayers to make four roughly equal estimated tax payments. These payments are made in April, June, and September of the year the income is earned, as well as January of the following year.

State Changed Payment Schedule During Great Recession to Address Budget Problem. The 2008‑09 budget changed the quarterly estimated tax payment schedule. The budget increased the required payment amount for April and June from a total of 50 percent to 60 percent (and reduced the required amount for the rest of the year). This change had the effect of accelerating tax collections from 2009‑10 into 2008‑09, thereby improving the 2008‑09 budget condition. As the state’s fiscal situation continued to deteriorate in 2009, the 2009‑10 budget package again changed the quarterly estimated tax payment schedule to collect 70 percent in the first half of the fiscal year and 30 percent in the second, improving the 2009‑10 budget condition. Figure 1 below summarizes these changes.

Figure 1

Overview of Changes to Estimated Tax Payment Schedule

|

Payment |

Payment Due on the 15th Day of: |

Percent of Total Estimated Tax Due: |

||||

|

Personal Income |

Corporation |

Prior to 2009 |

2009 |

Current |

||

|

1 |

April |

4th month, typically April |

25% |

30% |

30% |

|

|

2 |

June |

6th month, typically June |

25 |

30 |

40 |

|

|

3 |

September |

9th month, typically September |

25 |

20 |

— |

|

|

4 |

January |

12th month, typically December |

25 |

20 |

30 |

|

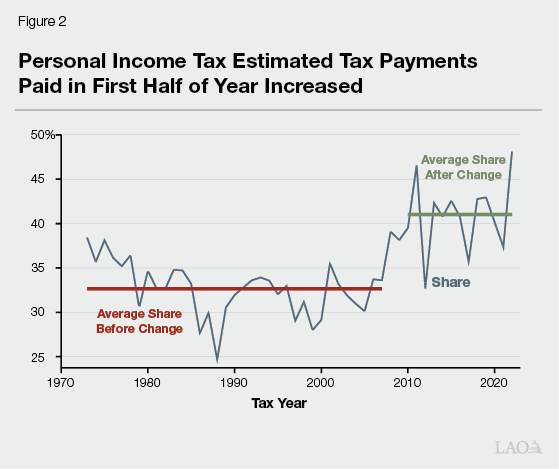

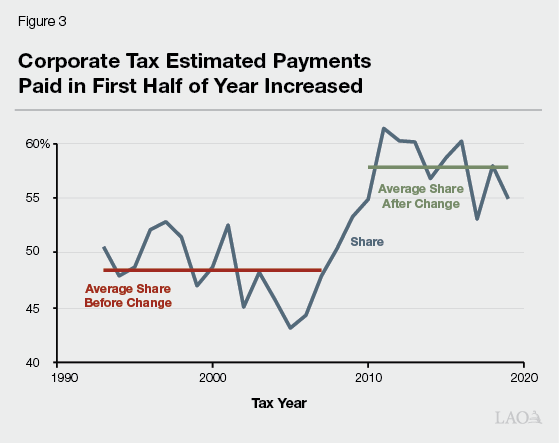

Actual Estimated Tax Payments Differ From Schedule. Some people make extra tax payments in months other than April, June, and January. For example, tax filers make estimated tax payments when they realize gains that they had not anticipated. Also, about one-quarter of tax filers make regular payments in September, even though state law no longer requires a September payment. In part, the variation from the state payment schedule is driven by the federal payment schedule, which is still made up of four equal payments Many taxpayers also make larger estimated tax payments at the end of the tax year. Due to this divergence from the schedule, tax filers pay significantly less than 70 percent of their estimated tax liability in the first half of the year and significantly more than 30 percent of their estimated tax liability in the second half of the year. In fact, tax filers typically pay less than half of their tax liability in the first half of the year, despite the schedule changes instituted in 2008 and 2009. (While there are penalties for underpaying estimated taxes, taxpayers with uneven income timing can avoid or minimize penalties if they make full estimated payments when they earn the income.) Figure 2 shows the share of estimated personal income tax liability paid in the first half of the year before and after the timing changes made in 2008 and 2009. Similarly, Figure 3 shows the share of estimated corporation tax liability paid in the first half of the year before and after these changes.

Due to Divergence From Equal Payments, Great Recession Changes Led to Modest Shift. As a result of the divergence from equal payments discussed above, in practice, the 2008 and 2009 timing shifts yielded relatively small tax payment shifts. Specifically, instead of shifting 20 percent of estimated tax payments into the first half of the year, the 2008 and 2009 changes had the effect of shifting an average of about 8 percent of personal income estimated payments and about 13 percent of corporation estimated payments.

Fiscal Effect of Returning Estimated Payments to 25 Percent Per Quarter

Revenue Shift. Returning personal and corporate income tax estimated payment amounts to four equal payments, beginning in tax year 2024, would shift about 8 percent of personal income tax estimated payments and 13 percent of corporation estimated payments from 2023‑24 to 2024‑25. This would occur because taxpayers would make fewer estimated payments in the first half of 2024 and more estimated payments in the second half of 2024. These amounts are lower than the 20 percent change that would be reflected in statute due to the payment divergence discussed in the previous section. Based on our November revenue forecasts, this change would reduce General Fund revenues by roughly $5 billion in 2023‑24. Returning to the historical payment schedule would have little net effect on revenue in 2024‑25. Specifically, while the change would shift roughly $5 billion from 2023‑24 to 2024‑25, the change also would have the effect of shifting a similar amount from 2024‑25 to 2025‑26. As a result, the net impact on 2024‑25 and later years would minimal.

Changes to Constitutional Budget Requirements. The revenue shift described above would result in changes to the state’s constitutional minimum funding requirement for schools. Specifically, the minimum funding requirement would go down by roughly $2 billion in 2023‑24 and remain the same amount in 2024‑25. The revenue shift also would have minor effects on Proposition 2 (2014) reserve requirements.

Administrative Costs. The Franchise Tax Board estimates that returning estimated payments to four equal payments would result in one-time administrative costs of $151,000 in 2023‑24.