LAO Contact

March 10, 2023

The 2023-24 Budget

Proposed Energy Policy Changes

Summary

In this brief, we assess the Governor’s proposed changes to how the state procures and pays for reliable clean energy. The Governor proposes to (1) establish a new central procurement role for the state to secure energy resources that would be used by electric utilities, for which costs would be recovered from ratepayers, and (2) require electric utilities that experience energy deficiencies to make payments in support of a new state‑operated program that provides emergency backup electricity resources. These proposals would represent significant changes in state‑level energy policy, as electric utilities have historically been responsible for procuring and paying for energy resources and reliability. As such, the proposals raise a number of key questions for the Legislature to consider, including: (1) how these policy changes might impact electricity rates; (2) whether these proposals are necessary in light of existing state procurement requirements and significant funding provided for electric reliability in the 2022‑23 Budget Act; (3) what risks the proposed new procurement role might pose to the state; and (4) the degree to which the proposals are needed now, as opposed to in a future year. We also recommend the Legislature weigh whether it may want to consider these proposals as part of the policy process, rather than the budget process, which could allow for more time for thoughtful deliberation.

Background

Greenhouse Gas and Clean Energy Goals

State Has Established Ambitious Greenhouse Gas (GHG) and Clean Energy Goals. Chapter 488 of 2006 (AB 32, Núñez/Pavley) established the goal of limiting GHG emissions statewide to 1990 levels by 2020. In 2016, Chapter 249 (SB 32, Pavley) extended the limit to 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030. Emissions have decreased since AB 32 was enacted and the state achieved its 2020 goal a year early. However, the rate of reductions needed to reach the SB 32 target are much greater. Chapter 337 of 2022 (AB 1279, Muratsuchi) established an additional objective, requiring the state to achieve carbon neutrality by 2045. In addition to these overall GHG reduction goals, the state has adopted particular emissions reduction goals for the electricity sector. Specifically, Chapter 312 of 2018 (SB 100, de León) established a state policy that 100 percent of retail electricity come from zero‑carbon sources by 2045. The Legislature set interim targets on the path to this goal via Chapter 361 of 2022 (SB 1020, Laird), which requires that zero‑carbon sources make up 90 percent of statewide electricity sales by 2030 and 95 percent by 2035. As discussed next, the electricity sector has been a driver of statewide emissions reductions thus far, but continued reductions are needed to meet these future goals.

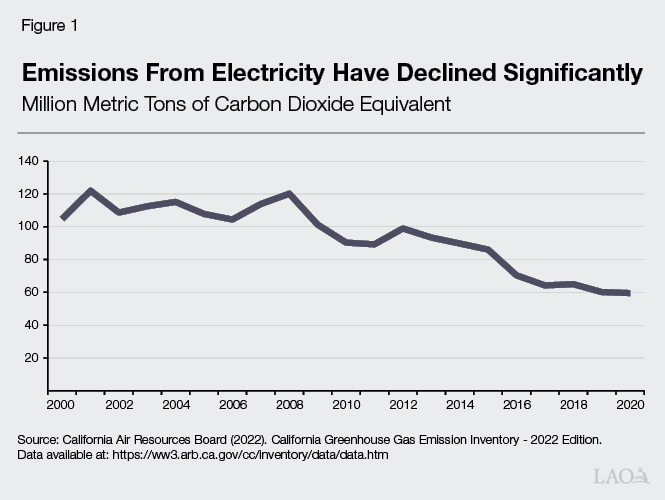

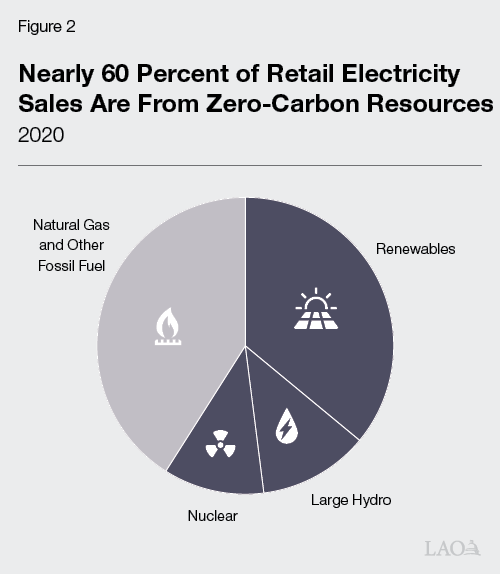

Electricity Sector Has Made Progress in Reducing Emissions Through Transitioning to Cleaner Sources. Over the last decade, the electricity sector has been a primary driver of statewide emissions reductions, as shown in Figure 1. Reductions mostly have resulted from changes in the mix of resources used to generate electricity—primarily increases in resources characterized as “renewables” (such as solar and wind) along with a decline in coal generation. A wide variety of factors have contributed to this shift, including technological advancements, federal policies, and state policies. As shown in Figure 2, nearly 60 percent of retail electricity sales came from zero‑carbon resources in 2020, including 36 percent from resources that qualify as renewable.

Reliability Challenges and Recent Funding

State Facing Some Energy Reliability Challenges. Climate change is contributing to demands on the state’s electric grid, with warmer temperatures leading to more calls for electricity during peak evening hours in the summer months. In August 2020, California experienced rolling power outages due to a heatwave and accompanying strain on the electric grid. The state avoided outages in 2021 and 2022, but energy resources were strained during summer heatwaves. A major heatwave in September 2022 caused the state to send an emergency text message alert to 27 million Californians to encourage energy conservation—the first time such a measure had been deployed. While the state has experienced significant growth in renewable energy sources in recent years, solar resources are not well‑positioned to supply energy during peak evening hours after the sun has gone down. Greater development of energy storage technology will be needed to help address the misalignment challenge of growing demand during times that a key renewable energy source is not available.

Significant Growth in New Energy Resources, but Also Project Delays. In recent years, the number of clean energy projects across the state has increased exponentially, with the amount of renewable energy supply more than tripling since 2005. Between 2020 and 2022, 130 new clean energy projects came online to serve customers in the California Independent System Operator network, which provides electricity to 80 percent of California. However, some projects also have experienced delays due to issues with the supply chain, permitting, and connecting new resources to the electric grid. While the state is on track to continue to develop new clean energy resources over the next decade, such delays in bringing these projects online could pose challenges in meeting the state’s clean energy, emissions, and reliability goals.

Recent Budgets and Policy Actions Provided Significant Funding for Clean Energy and Reliability. The 2022‑23 budget package planned for $9.6 billion over five years for clean energy programs and reliability efforts. The administration indicates that California also has received federal funds to support various energy efficiency efforts through the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, but has not yet provided specific details on the status of this funding or what types of projects it could support. The Governor’s budget proposes some reductions to state energy activities, but would maintain the majority of the planned funding ($8.7 billion). Moreover, a large share of this funding—$3.3 billion across five years—is for three programs intended to increase statewide electricity reliability, which the Governor does not propose reducing. Together, the administration refers to these three programs as the “Strategic Reliability Reserve,” and they include:

- Electricity Supply Strategic Reliability Reserve Program (ESSRRP, $2.3 Billion). This program funds the Department of Water Resources (DWR) to secure additional electricity resources to help ensure summer electric reliability. So far, these activities have included extending the life of gas‑fired power plants that were scheduled to retire, and procuring temporary diesel power generators and new energy storage. The ESSRRP provided between 554 megawatts (MW) and 1,416 MW of energy during last September’s extreme heat event. For context, the rotating outages in 2020 were caused by a shortfall of about 500 MW.

- Demand Side Grid Support ($295 Million). This new program, administered by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC), provides customer incentives to reduce net electricity load during extreme events. In the summer of 2022, utilities began enrolling participants in the program, which pays customers to reduce their energy usage during summer peak evening hours when the electric grid is strained.

- Distributed Electricity Backup Assets ($700 Million). This new program, administered by the California Energy Commission (CEC), provides incentives for certain distributed energy resources that can be used to support the state’s electrical grid during extreme events. The CEC is still developing the program, which is intended to fund zero‑ or low‑emissions technologies such as fuel cells and energy storage at both existing energy facilities and new facilities.

In addition to these budget actions, Chapter 239 of 2022 (SB 846, Dodd) authorized the extension of the Diablo Canyon Power Plant (DCPP)—which was scheduled to retire by 2025—through 2030. Diablo Canyon is California’s last remaining nuclear power plant, and the state has identified it as a valuable near‑term source of zero‑carbon energy during the transition to greater renewable resources. While the legislation authorized an extension, DCPP still has to receive required permits at the local, state, and federal levels in order to continue operations. SB 846 also authorized the following expenditures:

- Loan to Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) (up to $1.4 Billion). The Legislature specified intent to provide a General Fund loan of up to $1.4 billion to PG&E to support extended operations at Diablo Canyon. Of this total amount, the Legislature has authorized $600 million so far. The potential remaining $800 million is subject to a future appropriation. PG&E was awarded a $1.1 billion federal grant from the U.S. Department of Energy in November 2022 and is expected to use this award to pay back the state for loans it ultimately receives.

- Clean Energy Reliability Investment Plan (CERIP, $1 Billion). Senate Bill 846 also included legislative intent to provide a total of $1 billion General Fund from 2023‑24 through 2025‑26—$100 million in 2023‑24, $400 million in 2024‑25, and $500 million in 2025‑26—to support the CERIP, which CEC recently developed. The legislation required the plan to support investments that address near‑ and mid‑term reliability needs and the state’s GHG and clean energy goals. In accordance with the legislation, the administration proposes to provide $100 million in 2023‑24 for CERIP‑identified activities. Specifically, the Governor proposes: (1) $32 million for DWR to develop a proposed new central procurement role described below; (2) $33 million for extreme event support (including additional funding for the Demand Side Grid Support and Distributed Electricity Backup Assets programs); (3) $20 million for various administrative, community engagement, and planning expenditures; and (4) $15 million to help new energy resources come online.

Procuring Reliable Clean Energy Resources

State Generally Determines What Levels of Energy Resources Are Needed, Then Requires Regulated Local Entities to Procure Them. With regard to CPUC‑regulated electric utilities, the state generally has assumed responsibility for determining (1) how much energy will be needed to reliably meet statewide demand, and (2) what share of those resources must be from renewable sources to meet the state’s GHG reduction and clean energy goals. After the state determines these needs, it then requires local energy providers—known as Load Serving Entities, or LSEs—to procure them. (As described below, this process works slightly differently for publicly owned utilities [POUs].) LSEs can procure energy through purchasing contracts or by developing the resources themselves (such as by building solar arrays). Please see the nearby box for more background about LSEs.

Load Serving Entities (LSEs) in California

LSEs are entities that provide electricity to customers. They include the following types of organizational structures:

- Investor Owned Utilities (IOUs): The territory of California’s six privately owned IOUs covers about 75 percent of the state’s electricity needs. The three largest IOUs in the state are Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric. The California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) regulates IOUs by setting their electricity rates for customers and requiring them to procure and maintain a certain amount of energy resources.

- Community Choice Aggregators (CCAs). The CCA program allows cities, counties, and other government entities within the service area of an IOU to purchase and/or generate electricity for their residents and businesses. The intention of this program is to increase options for customers. The IOU continues to deliver the electricity through its transmission and distribution system and provides meter reading, billing, and maintenance services for CCA customers. CCA energy resource needs are regulated by CPUC. There currently are 25 CCAs in California.

- Electric Service Providers (ESPs). ESPs are non‑utility companies that provide electricity to large electric users within the service territory of an existing electric utility. They are regulated by CPUC and there are 20 ESPs in California.

- Publicly Owned Utilities (POUs): POUs are regulated by locally elected governing boards such as municipal utility districts, which govern POU energy resource needs and rates. The state has some authority over POU energy resources. POUs provide about 25 percent of the state’s electric services. Examples of large POUs include Sacramento Municipal Utility District and Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. There are 47 POUs in California.

State Has Adopted Numerous Requirements for LSEs to Help Ensure Reliability and Procurement of Clean Energy Resources. CPUC is responsible for a number of programs and activities designed to (1) grow the share of renewable resources used to generate electricity and (2) ensure regulated LSEs are procuring enough energy to both serve demand and meet state GHG goals. These programs and initiatives include:

- Resource Adequacy (RA) Program. The RA program was established in 2004 to promote electric reliability. CPUC establishes RA obligations for all LSEs within its jurisdiction, including Investor Owned Utilities (IOUs), Community Choice Aggregators (CCAs), and Electric Service Providers. LSEs are required to demonstrate compliance with RA requirements on both a monthly and annual basis and must pay penalties if they do not comply. The current RA program mandates a 16 percent planning reserve margin (that is, the amount of resources an LSE must have on reserve, as a percentage of peak total electricity load, in case of extreme events). The planning reserve margin will increase to 17 percent in 2024. This margin is also known as the planning standard or RA margin.

- Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS). The RPS was established by Chapter 516 of 2002 (SB 1078, Sher) with the initial requirement that 20 percent of retail electricity must be provided by renewable energy resources by 2017. The RPS program is overseen jointly by CEC and CPUC and has been updated numerous times. Senate Bill 100 increased the RPS requirement to 60 percent of retail electricity coming from renewable sources by 2030. All LSEs, including POUs, are required to comply.

- Integrated Resource Planning (IRP) Process. The IRP process was established in 2015 through Chapter 547 (SB 350, de León) to plan for how LSEs could meet mid‑ and long‑term energy procurement and GHG goals while maintaining reliability. As part of this process, CPUC conducts modeling that sets out a path for the state to meet its energy needs while reaching its emissions reduction goals. Regulated LSEs are then required to use CPUC’s model to develop their own individual IRPs. CPUC ultimately approves each LSE’s IRP and the process is updated every two years. The IRP process is CPUC’s primary planning tool to ensure that the state is meeting its emissions reductions goals from the electricity sector. CPUC initiated a related process, the IRP Procurement Track, in 2019. The IRP Procurement Track orders LSEs to undertake additional resource procurement beyond the normal IRP planning time line, recognizing that some newer clean energy resources have longer lead times (such as offshore wind and long duration storage).

Recognizing that the state’s growing electricity needs and emissions reduction goals will necessitate new resources, CPUC has used these processes to mandate unprecedented expansions in energy procurement in recent years. For example, between 2020 and 2022, CPUC’s IRP procurement orders resulted in more than 11,000 MW of new energy resources, most of which are coming from solar, wind, and battery storage projects. CPUC also has expanded its allowed time lines for LSEs to secure new energy resources in recognition of the timing difficulties in bringing these resources online. For instance, in February 2023, CPUC extended its deadline for a new procurement order that totals 4,000 MW of additional energy capacity from 2026 to 2028.

Public Utilities Also Subject to Some State Requirements for Energy Resource Procurement. Because POUs are outside of CPUC’s jurisdiction, some—although not all—of their reliability requirements differ from those of other LSEs, and their compliance with state requirements largely is overseen by CEC. Like other LSEs, POUs are subject to the RPS requirements for renewable energy procurement. Additionally, the state’s largest POUs (which account for 94 percent of POU electric load and customers) are required to submit an IRP every five years to CEC. In addition, Chapter 251 of 2022 (AB 209, Committee on Budget) required CEC to develop updated planning reserve requirements for POUs that account for the increased frequency of extreme weather events and reliability challenges the state has experienced in recent years. CEC is required to develop these requirements by December 2023.

IOUs Sometimes Play Centralized Procurement Role. LSEs generally are required to procure new energy resources themselves, but IOUs are legally authorized—and, in some cases, required—to procure resources on behalf of other LSEs. For example, a 2019 CPUC decision ordered LSEs to procure additional RA‑qualifying resources and allowed IOUs to act as a procurement backstop. In response to this order, between 2020 and 2022, 15 LSEs elected to have an IOU procure energy resources on their behalf. CPUC also has compelled IOUs to procure resources on behalf of other LSEs, because the relatively small size of some LSEs—in particular, many CCAs—can make procuring larger resources somewhat difficult. Over the past few years, IOUs have experienced challenges in centrally procuring resources due to associated costs, as they have simultaneously been facing growth in other types of costs such as those related to wildfire mitigation.

State Has Some Limited History of Undertaking Procurement Activities. While the state mostly tasks LSEs with procurement responsibilities, it has occasionally stepped in to undertake these activities in the past. For example, during the energy crisis of the early 2000s, California experienced electricity supply shortages and utilities struggled to attain capital for energy projects. In response, DWR financed energy purchases on behalf of IOUs and entered into long‑term contracts for electricity valued at over $40 billion. The last of these contracts terminated in 2015. In addition, as mentioned above, the 2022‑23 budget package committed $2.3 billion over five years for DWR to secure additional electricity resources intended to ensure summer electric reliability. So far, ESSRRP activities have mostly extended the life of natural gas plants that supply electricity—these plants are only turned on when the electric grid is experiencing major strain. The administration indicates that the ESSRRP also provided financing support to IOUs for their procurement of electricity imports last summer.

Clean Energy Goals and Growing Electricity Demand Will Necessitate Procuring New Types of Resources. While California has brought a significant amount of clean resources online in recent years, including wind and solar projects, new resources still will be needed to meet the state’s clean energy goals and satisfy electricity demand. The state’s electricity planning agencies anticipate that demand will grow significantly over the next decade due not only to climate change and higher temperatures, but also to a shift towards zero‑emission vehicles and more electric‑powered appliances and heating. This likely will necessitate adding larger “long‑lead time” resources (such as offshore wind, long duration storage, and geothermal electric generation) to the state’s portfolio. However, such resources typically are more expensive and take longer to develop. Moreover, fewer of these projects currently exist in California, so local entities do not have a proven history to rely upon when seeking to develop or procure them. Because of the expense and general risk associated with newer, large technologies, smaller LSEs face particular challenges in procuring these types of resources.

Governor’s Proposals

Governor Proposes Two Major New Energy Policy Changes. The Governor has put forward two major proposals related to procuring sufficient clean energy resources to meet reliability and GHG reduction goals. These proposals are contained in budget trailer legislation. The proposals include: (1) establishing a new centralized energy procurement role for the state, for which costs could be recovered from ratepayers, and (2) requiring “capacity payments” from LSEs that experience energy resource deficiencies during months when the state utilizes the ESSRRP. Figure 3 describes each proposal in detail.

Figure 3

Summary of Governor’s Major New Energy Policy Proposals

|

New Centralized Procurement Role for the State |

|

|

|

|

|

New Charges for LSEs That Do Not Procure Sufficient Energy Resources |

|

|

|

Some Initial Funding to Come From the General Fund. As described in the figure, the Governor proposes to fund the ongoing support and operational costs for DWR’s new procurement role from new charges to ratepayers. These charges also would be used to pay off any bonds that DWR might issue for large capital costs. In addition, the Governor proposes using General Fund in 2023‑24 to help “stand up” the new procurement function at DWR. Specifically, the CERIP that CEC recently submitted to the Legislature includes $32 million—of the intended $100 million budget‑year amount—to help establish this new central procurement office and process.

Other Technical Statutory Changes to Existing Energy Policies and Programs. The proposed trailer legislation also includes various statutory changes for the three Strategic Reliability Reserve programs and DCPP which the administration considers to be technical “clean up.”

Key Questions for Legislative Consideration

The Governor’s proposed changes to the way energy is procured and paid for in California represent a significant new role for the state. As we highlight below, the proposals raise a number of crosscutting questions that the Legislature will want to consider as it weighs whether or not to adopt any of these changes. As such, we recommend the Legislature take sufficient time to engage with the administration and stakeholders such that it feels confident it has answers to these questions. The Legislature has a number of options for undertaking such deliberations, including oversight hearings and both formal and informal information requests to the administration. Below, we summarize the key questions that we find merit legislative consideration.

How Would Ratepayers Be Affected? How electric ratepayers would be affected by the Governor’s proposals is unclear. In order to understand the potential impacts, we recommend the Legislature consider the following issues when evaluating the proposal:

- New Charges and Capacity Payments. Under the proposal, LSEs that do not procure sufficient energy resources would be required to make a capacity payment to support the ESSRRP. In addition, LSEs could be required to apply a non‑bypassable charge to ratepayers to cover DWR’s central procurement costs. The effects these charges would have on rates are unclear. Given that California’s electricity rates already are among the highest in the nation and rising faster than inflation, the Legislature will want to carefully consider the potential impacts on rates and whether the potential benefits merit those costs.

- Market Effects of Central Procurement. Under the proposal, DWR would be able to procure energy resources on behalf of the state and LSEs if requested by CPUC. The current market for energy resources is strained, with a large number of LSEs competing for a relatively small pool of projects that often will take years to develop. How the entrance of DWR—a large, well‑resourced entity with the backing of the state—would influence the market for new energy resources is unclear. The market for large, long‑lead time resources, which the administration says would be the priority for DWR’s procurement, is somewhat nascent and developing, as these types of resources are newer technologies and very expensive to build. This makes it even more difficult to predict the potential effects of the central procurement proposal. Because DWR likely would have more resources to expend than other purchasers, it is also unclear how energy resource developers may alter prices. Ultimately, how energy resources are priced will affect the rates customers are charged.

Are Current Processes and Resources Insufficient? The administration states that the procurement option and capacity payments to the ESSRRP are necessary to avoid energy shortfalls occurring among LSEs. However, these processes largely have been adequate thus far, and the state has taken numerous other actions in pursuit of the same goals. Yet the extent to which existing reliability requirements and procurement processes will be sufficient to meet future needs is uncertain. The following are existing processes and resources that are designed to support current and future electric reliability:

- Existing IRP and Planning Processes. As described above, LSEs are required to demonstrate sufficient energy capacity to the state through the IRP process, RA requirements, and—in the case of POUs not subject to those requirements—separate planning reserve margin targets administered by CEC. While the electric grid has been strained in recent summers, whether LSEs are actually at risk of a serious shortfall that could lead to reliability issues is unclear. The administration reports that no shortfalls have been identified by any LSE for IRP energy resource procurement recently. CPUC has recognized the need for more energy capacity and has issued numerous orders in recent years both for LSEs to procure more resources and to extend the time they have to do so, recognizing the delays in permitting and building new energy projects described above. In addition, as noted, efforts currently are underway at CEC to develop new planning reserve margin targets for POUs, which could support additional reliability.

- Existing Collective Action. LSEs have successfully banded together to procure resources in the past. For example, CCAs and POUs have formed joint powers authorities to procure power on a collective basis. Taking this approach to procure larger, long‑lead time resources may prove more challenging, as these resources can be very expensive and the market is limited. However, certain existing locally based collective approaches may be sufficient to meet reliability needs in the future.

- Existing IOU Central Procurement. IOUs have been directed to procure on behalf of other LSEs in the past, and CPUC has authorized them to recover their costs of doing so. Additionally, last summer, the state provided financing support for IOUs to procure through the ESSRRP. Some IOUs have reported challenges procuring energy resources on behalf of others due to the high capital costs of procuring larger resources and a more diverse landscape with the rise of CCAs. However, if the Legislature was concerned about the potential risks of DWR acting as a central procurement authority, expanding centralized procurement undertaken by IOUs could be an alternative option worth exploring. If the state were to provide financing support to IOUs, similar to how it did in the summer of 2022, cost issues could prove less of a barrier.

- DCPP. As described above, the Legislature has authorized the extension of DCPP through 2030, though the plant will have to overcome a number of regulatory hurdles before it can continue operations past its originally scheduled sunset date of 2025. Accordingly, the administration is not accounting for the availability of DCPP‑provided energy past 2025 in its reliability planning and modeling for the next decade. Given the remaining uncertainty around whether the extension will proceed, we find that this approach is reasonable. However, if DCPP continues operations as intended, the plant would provide a significant contribution to helping the state meet its reliability goals—2,280 MW, which is more than double the reliability benefits provided by the ESSRRP in 2023 and nearly five times the MW shortfall that resulted in the rotating outages of 2020. The availability of DCPP from 2025 through 2030 could significantly improve the state’s reliability outlook and reduce the urgency of the need that the administration has identified for these new policy proposals.

What Are the Risks to the State? The administration has expressed concerns that LSEs might be hesitant to procure large, long‑lead time resources because of their high cost and risk as newer technologies. The Governor’s proposal to have the state pursue procuring these resources instead essentially shifts this risk from the privately owned utilities (and their investors) to ratepayers and taxpayers. While this could help facilitate the development of these important resources, additional information is needed about the types of risks involved and their magnitude for the Legislature to determine if they are worth the potential benefits. Additionally, the Legislature could explore whether it might be able to adopt statutory “guardrails” or protections to help minimize potential risks to the state from pursuing unproven technologies. For example, this could include capping the amount of funding DWR could invest in newer and more uncertain types of technologies. The Legislature also could require DWR to prioritize certain types of resources that it believes to be safer types of investments, such as long duration storage projects. While the Governor’s proposal would require DWR to utilize project evaluation criteria, whether these would be sufficient to adequately assess and limit the potential risks to the state is unclear.

What Is the Status and Effectiveness of Recent Investments? The state invested heavily in reliability efforts in the 2022‑23 budget package and state departments still have not spent most of the associated funds. While the ESSRRP appears to have provided important reliability support during the September 2022 heat wave—primarily through utilizing natural gas plants—how it might provide support in future years still is unclear. More broadly, the Strategic Reliability Reserve programs have significant funds remaining in their balance. For example, as of February 2023, the ESSRRP had committed $654 million for specific expenditures, but $1.4 billion of funding the Legislature appropriated for 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 remained unspent. If the ESSRRP continues to be relatively slow to spend down its existing funds, asking ratepayers to provide the program with even more funds through the proposed capacity payments seems potentially unnecessary. Specifically, whether capacity payments in support of the ESSRRP—which LSEs would pass down to ratepayers—are needed seems questionable, given the availability of significant General Fund resources from the previous budget. Moreover, existing penalty requirements already are in place to help discourage LSEs from under‑preparing, so it is also not clear that these payments are needed to incentivize compliance with planning mandates.

Is a Central Procurement Function Necessary Now? Should the proposals be adopted as budget trailer legislation, the new authorities they grant to the state would take effect upon enactment of the statute, even though the administration estimates it would not utilize the procurement option in the 2023‑24 fiscal year. A rationale could exist for the state to take on central procurement authority to support the procurement of larger, long‑lead time resources—particularly given that these are difficult for individual LSEs to procure on their own or even banded together. However, whether this new authority is needed urgently this year is unclear. The Legislature may want to consider deferring a decision on these proposals beyond the coming budget discussion time line or even beyond the 2023 session. Delaying action could sacrifice some time that could be spent beginning to develop these resources, but given the many questions that remain about this proposal, taking more time to weigh the trade‑offs could be valuable.

Should the Governor’s Proposals Be Considered as Part of the Budget Process? The Governor’s proposals represent significant policy changes for the state and they do not have a particularly strong nexus with the budget. The Legislature will want to consider the most appropriate venue for discussing and deliberating these proposed changes. For example, the Legislature could consider these proposals through the policy process, rather than as part of the budget process. Ultimately, ensuring it has the time and opportunities for developing a greater understanding, sufficient input from stakeholders, and thoughtful deliberation will be vital to ensuring it can make an informed decision on these important proposals. Given the policy implications of the Governor’s proposals and the fixed constitutional time frame associated with adopting the annual budget—as well as the complicated fiscal decisions the budget process will involve this year, in the context of the General Fund shortfall—the budget process may not be the best venue for deliberating these proposals.