August 17, 2023

Proposed Bond to Fund Behavioral Health Facilities and Veterans Housing

Summary. This post is one of a series of analyses on the various components of the Governor’s Behavioral Health Modernization proposal. Earlier posts analyzed SB 326 (Eggman), which would make far-reaching changes to the Mental Health Services Act (MHSA). This post focuses on that bill’s counterpart, AB 531 (Irwin), as amended on June 19, 2023, which proposes a $4.7 billion bond for behavioral health facilities and housing for veterans. The Governor’s proposed bond uses an appropriate funding mechanism to address a well-documented need for behavioral health facilities and veterans housing—priority areas for the Legislature. These elements of the Governor’s proposal are broadly reasonable. The Governor, however, proposes a limited role for the Legislature in the design and implementation of the bond. We recommend amendments that would ensure the Legislature would have an active and ongoing role in ensuring the bond’s success.

Background

Public Community Behavioral Health Services

Counties Are Primarily Responsible for Funding and Delivering Community-Based Services for Low-Income Individuals With the Highest Service Needs. Counties play a major role in the funding and delivery of public behavioral health services. In particular, counties generally are responsible for arranging and paying for community behavioral health services for low-income individuals with the highest service needs through Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid program. Community behavioral health services comprise publicly funded outpatient and inpatient mental health and substance use disorder (SUD) treatment and medications provided primarily in community settings.

Individuals Receive Treatment in Many Facility Types Across Behavioral Health Continuum. As an individual’s behavioral health needs change, the level of service they receive and setting in which they receive care also ideally change. In order to provide individuals appropriate care, the behavioral health system must offer a wide range of services in a variety of settings, commonly referred to as a continuum of care. Ideally, behavioral health services would be offered in sufficient supply to allow for individuals to move through this continuum as their needs change. Otherwise, individuals may receive care at a higher or lower level of acuity than they need.

Various Types of Entities Provide Services in Hundreds of Facilities Statewide. In January 2022, the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) released a report titled Assessing the Continuum of Care for Behavioral Health Services in California. The report examines the statewide capacity to provide behavioral health services across the full spectrum of behavioral health care. Based on data from the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, DHCS estimated that over 600 facilities provide outpatient mental health services and nearly 800 facilities provide substance use disorder services. DHCS also estimated that over 100 facilities provided inpatient care—ranging from psychiatric units within general acute care hospitals, freestanding psychiatric acute care hospitals, and psychiatric health facilities. Behavioral health facilities are operated by various entity types, including public, private nonprofit, and private for-profit entities.

Counties Can Use a Variety of Funding Sources for Community Behavioral Health Facilities. Counties rely on a variety of major, dedicated, ongoing fund sources to finance their community behavioral health activities, including facilities. These sources include (1) dedicated vehicle license fee and sales tax revenue streams known as “realignment” funds, (2) revenues from the Mental Health Services Fund (MHSF)—established by the MHSA and funded through a 1 percent tax on incomes over $1 million, and (3) federal funding accessed through Medi-Cal. (In addition, counties may use local funds to supplement these state dollars, although the extent of this local funding contribution is unknown.) Although each of these funding sources has its own set of objectives and rules dictating how funds can be spent, there is sufficient overlap in purpose between these funding sources for counties to use them relatively flexibly to meet their community behavioral health service obligations. Notably, under current law, funding that counties receive from the MHSF is required to be spent according to certain parameters, including (1) direct services and (2) prevention and early intervention activities. Up to 20 percent of the amount counties receive from the MHSF for direct services can be used on capital (including facility acquisition and renovation), technology, workforce development, or to build reserve funding. However, the amount within this allowance (and of counties’ overall behavioral health funding) that counties spend on acquiring or renovating community behavioral health facilities is unknown.

Recent Budgets Have Included Major Funding for New Behavioral Health Infrastructure. Recent state spending plans have included billions of dollars for behavioral health facilities. In particular, the 2021‑22 budget included $2.2 billion ($1.7 billion General Fund and $530 million federal funds) on a one-time basis for the Behavioral Health Continuum Infrastructure Program (BHCIP). Funding for five rounds have been awarded as follows: (1) $145 million for mobile crisis infrastructure, (2) $16 million for county and tribal planning grants, (3) $519 million for “launch ready” projects, (4) $481 million for projects targeted at children and youth, and (5) a general-purpose round totaling $480 million. The 2023‑24 budget delayed the sixth and final round totaling $481 million to 2024‑25 ($240 million) and 2025‑26 ($240 million).

Shortage of Adult Psychiatric and Community Residential Beds

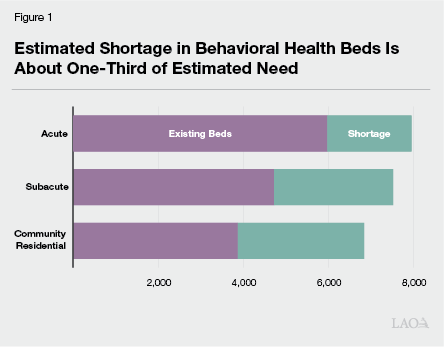

Recent Study Estimated Shortage in California. A recent study released by the RAND Corporation assesses the state of adult psychiatric and community residential beds in California. The study was funded by the California Mental Health Services Authority, a county-level joint powers authority, to assess both the capacity and unmet needs of key components of the public behavioral health system. Generally, the researchers used state licensure data to estimate the current (as of 2021) capacity of adult beds in the state. RAND used three approaches for estimating the shortage of beds: (1) surveying psychiatric facilities to gather data on bed occupancy, wait list volume, and other information; (2) convening an expert panel to estimate bed need based on available research; and (3) assessing national and state survey data concerning the prevalence of serious mental illness to determine the regional variation in the need for beds. The study classifies psychiatric beds in three categories: acute (individuals with the highest level of needs, typically served for days to weeks), subacute (moderate to high level of needs for multiple months), and community residential (lower level of need for up to multiple years). The researchers estimated that the shortage of adult beds totals about 2,000 beds at the acute level, 2,800 beds at the subacute level, and about 3,000 beds at the community residential level. As shown in Figure 1, the estimated shortage is significant and particularly severe at the community residential level. RAND notes that the shortage in beds results in occupancy rates that are higher than generally accepted levels, long wait lists, and facilities unable to transfer patients to settings of more appropriate levels of care. Other key findings and recommendations from, as well as limitations of, the study include:

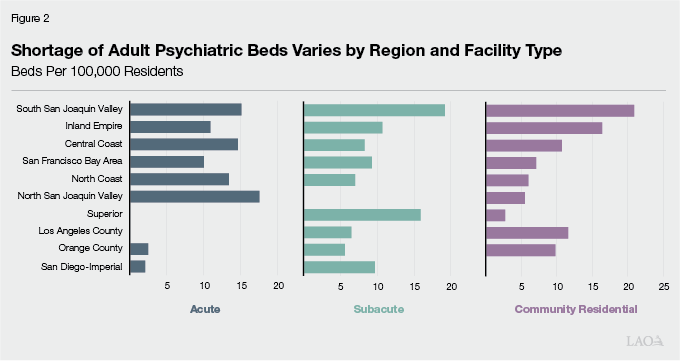

RAND Estimates Shortage Varies Substantially by Region. RAND found that the shortfall of beds varied widely across regions and by categories of beds. On a per-100,000 residents basis, RAND estimates the statewide need for beds to be about 26 beds at the acute level, 24 beds at the subacute level, and 22 beds at the community residential level. Figure 2 displays RAND’s estimates of the regional shortfall by facility type. In the South San Joaquin Valley, Inland Empire, Central Coast, and San Francisco Bay Area, RAND estimates a general shortfall across all categories. The shortage is generally most severe in these regions. In other areas—such as in Los Angeles County, North San Juaquin Valley, San Diego-Imperial, and the Superior region (northern inland counties)—RAND estimates a shortage in some categories but a surplus in other categories.

RAND Recommends Focusing on Hard-to-Place Populations. RAND found that one-half of facilities were unable to place adults with co-occurring conditions, such as dementia, and two-thirds of facilities were unable to place justice-involved individuals. In addition, facilities struggle to place individuals with unique needs, such as those requiring oxygen. These hard-to-place populations contribute to bottlenecks in the system. RAND recommends that efforts to address the shortfall in adult beds be designed with this particular problem in mind.

Study Did Not Estimate Need for Beds for Children and Adolescents. The RAND researchers did not include children and adolescents in the scope of their analysis. The researchers indicated that children and adolescents have “subtle but important differences” in care needs and thus the sufficiency of facilities for this population should be assessed separately from adults.

Researchers Stressed Significant Data Limitations. While the RAND research approach generally appears reasonable, the researchers indicated that poor state licensure data casts significant uncertainty upon their estimates of existing facilities. Notably, based on information from county officials, the researchers removed 30 percent (about 1,800) of facilities from the state data. Reasons that facilities were removed from the state data included facility closures, an absence of licensed psychiatric beds, or facilities not accepting patients with mental health conditions.

Housing and Homelessness Programs for Veterans and Others With Behavioral Health Needs

Many Individuals Experiencing Homelessness Also Have Behavioral Health Needs… Although housing affordability is the most significant factor in the state’s homelessness crisis, there are many individuals experiencing homelessness who also have behavioral health needs. Estimates vary on exactly how many individuals experiencing homelessness also suffer from behavioral health disorders. According to the U. S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s 2022 point-in-time count, 23 percent (39,700) of the 171,500 people experiencing homelessness in California suffered from severe mental illness and 21 percent (36,000) suffered from a chronic SUD. (There is likely overlap between these two populations, the degree to which is unknown.) Furthermore, the same point-in-time count found 6 percent (10,400) of people experiencing homelessness in California were veterans and over 70 percent of these veterans experienced unsheltered homelessness. How many veterans also had behavioral health needs is unclear. However, the prevalence of behavioral health disorders appears to differ for distinct categories of people experiencing homelessness. For example, researchers have estimated that the prevalence of mental illness and SUD is higher for people experiencing unsheltered homelessness than sheltered homelessness. Available research also indicates that experiencing homelessness may lead some individuals to develop or exacerbate existing behavioral health issues due to the chronic stress of living without stable housing.

…And Could Benefit From Receiving Housing Support Paired With Behavioral Health Services. For individuals who both experience homelessness and have behavioral health needs, behavioral health services could be an essential component of addressing their homelessness. As discussed earlier, the chronic stress of living without stable housing may lead an individual to develop a behavioral health disorder. In turn, this can make it more difficult for an individual to exit homelessness as their behavioral health issues make it even more challenging to maintain housing stability. Accordingly, these individuals could particularly benefit from a more comprehensive approach to care that includes housing supports paired with behavioral health services.

State Housing and Homelessness Programs for Veterans and People With Behavioral Health Needs. The state administers various housing and homelessness programs for veterans and people experiencing or at risk of homelessness with behavioral health needs.

No Place Like Home (NPLH) Act of 2018. The NPLH Act of 2018 (Proposition 2) authorized $2 billion in bonds to construct new, and rehabilitate existing, permanent supportive housing for people who need mental health services and are experiencing homelessness or are at risk of homelessness. The housing support provided through NPLH is paired with mental health services. All bond funding has been allocated as of August 2022. The bonds will be repaid over time using MHSA funds. NPLH has supported 247 projects and 7,852 housing units are anticipated. As of August 2022, 119 projects are under construction, 30 projects have been completed, and 498 units have units have been completed and are occupied.

The Veterans and Affordable Housing Bond Act of 2018. The Veterans and Affordable Housing Bond Act of 2018 (Proposition 1) authorized $4 billion in general obligation bonds for various housing programs. The bond set aside $1 billion for veteran homeownership, which is administered by the California Department of Veterans Affairs (CalVet). Based on data provided by CalVet in March 2023, the department has lent $364 million to veterans for home purchases. There is $636 million in bond authority remaining and the next release of funding is anticipated in fall 2023.

Veterans Housing and Homeless Prevention Bond Act of 2014. The Veterans Housing and Homeless Prevention Bond Act of 2014 (Proposition 41) restructured $600 million in existing general obligation bonds for veteran multifamily rental housing. The funding is administered through the Department of Housing and Community Development’s (HCD’s) Veterans Housing and Homelessness Prevention Program (VHHP). (The restructuring was necessary because $900 million in general obligation bonds authorized in 2008 for veteran homeownership did not experience the demand that was projected before the housing downturn during the Great Recession.) HCD indicates that, of the $600 million that was restructured for VHHP funding, $62 million remains available. According to HCD, it has accepted applications for this remaining VHHP funding from Proposition 41. The applications HCD has received have collectively requested $109 million in funding, more than is available for award. Once HCD selects awardees, Proposition 41 funds are expected to be exhausted.

State Infrastructure Financing

Two Ways the State Usually Pays for Infrastructure Projects. The state’s infrastructure spending relies on various financing approaches and funding sources.

Pay-As-You-Go. Under the pay-as-you-go approach, the state funds infrastructure up front through direct appropriations of tax and fee revenues. Pay-as-you-go spending from special funds makes up a significant share of the state’s infrastructure spending, primarily in the transportation sector. (The recent funding for behavioral health infrastructure noted above is funded on a pay-as-you-go basis.)

General Fund-Supported Bonds. The state traditionally has sold two types of bonds that are typically paid off from the General Fund: voter-approved general obligation bonds and lease revenue bonds approved by the Legislature. (The state also sells bonds repaid from special funds.)

How Bonds Work. Bonds are a way that the state (as well as local governments and private companies) borrows money. The state sells bonds to investors to receive “up-front” funding for projects and then repays investors, with interest, over a period of time.

When and Why the State Uses Bonds to Finance Infrastructure Projects. A main reason for issuing bonds to finance infrastructure projects is that infrastructure typically provides taxpayers with a public benefit over many years. Thus, it is reasonable for taxpayers, both currently and in the future, to help contribute to the financing costs. Bonds can therefore promote intergenerational equity by spreading costs across generations of taxpayers roughly proportionate to the benefits that they receive. Another advantage to bond financing over pay-as-you-go financing is the full access to funding up front to complete a project rather than in stages over a longer period of time based on funding availability.

The Costs of Bond Financing. After selling bonds, the state makes annual payments over the following few decades until the bonds are paid off. (This is similar to the way a family pays off a mortgage.) Although when compared with the pay-as-you-go approach, the up-front cost to the state of bond financing a project is significantly lower, overall costs are higher due to the interest on the debt. The amount of additional cost depends primarily on the interest rate and the time period over which the bonds have to be repaid. For example, assuming that a bond carries an interest rate of 4 percent, the cost of paying it off over 20 years is close to $1.50 for each dollar borrowed—$1 for repaying the principal amount and about $0.50 for interest. This cost, however, after adjusting for inflation is considerably less—about $1.10 for each $1 borrowed.

About $71 Billion in Principal Outstanding From Issued General Obligation Bonds. As of July 1, 2023, the total amount of authorized general obligation bond debt that remains outstanding was $95.2 billion. This is the combination of $70.7 billion in bonds that have been issued but not fully repaid and $24.5 billion in bonds that have been authorized by the voters but not yet sold to investors.

Annual Debt Service Currently Represents Less Than 3 Percent of General Fund Spending. The 2023‑24 budget package reflects $6.5 billion in debt service on general obligation bonds, or 2.6 percent of General Fund revenues. These debt service costs are about as low as they have been in recent decades, and roughly half of debt service costs at their recent peak of about 6 percent in 2010‑11.

Several Bond Proposals Currently Under Consideration in the Legislature. There are several bills currently moving their way through the Legislature that would place general obligation bonds before the voters. In the aggregate, the bonds that would be authorized by these bills exceeds $100 billion. (We expect the amount of bonds that the Legislature ultimately will place before the voters will be lower than this amount.) Most relevant to AB 531, the proposals include $25 billion for home ownership and construction (SB 834 [Portantino]), $10 billion for affordable rental housing and home ownership programs (AB 1657 [Wicks]), and $5.2 billion for substance use treatment and other behavioral health programs (AB 1510 [Jones-Sawyer]).

Proposal

Governor Proposes Major Changes to Behavioral Health System and Additional Behavioral Health Beds and Veterans Housing. In March, the Governor provided the Legislature with a broad outline of a proposed package of changes intended to modernize the state’s behavioral health system, combined with additional funding for behavioral health housing. The proposal is currently moving through the Legislature in two companion bills—SB 326 (Eggman) and AB 531 (Irwin). Senate Bill 326 would make far-reaching changes to the MHSA, including a restructuring of funding categories that would require counties to allocate more MHSA funding towards Full-Service Partnerships and housing interventions. By making more activities compete for a smaller, flexible category of funding, the bill may also make it harder for counties to prioritize capital facility needs. This post focuses on that bill’s counterpart, AB 531, which proposes a general obligation bond for behavioral health facilities and housing for veterans.

The Proposed $4.7 Billion Bond for Behavioral Health Beds and Veteran’s Housing. The Governor proposes a $4.7 billion general obligation bond for the March 2024 ballot to construct or rehabilitate up to 10,000 behavioral health beds in residential settings and housing units for veterans and other individuals experiencing or at risk of homelessness. The total cost of the bond, including interest, would be around $5.1 billion (in inflation-adjusted terms). Bond proceeds would be continuously appropriated, meaning that the Legislature would not be required to appropriate the bond proceeds in the annual budget act to allow for their expenditure. Up to 3 percent of the bond proceeds could be used for administrative costs. Principal and interest on the bonds would be repaid by the state General Fund. Projects funded by the bonds would be deemed in conformity with local zoning rules and would be exempt from California Environmental Quality Act requirements provided the projects meet specified criteria. Grant recipients would be required to operate the facilities and units added by the bond for at least 30 years. The proposal is silent on the types of entities that would be eligible to receive grants. The bond proceeds would be used as follows:

Up to $865 Million Dedicated to Housing Grants. Assembly Bill 531 sets aside up to $865 million for HCD to award grants to construct and rehabilitate housing for veterans and others who are experiencing or at risk of homelessness and are living with a behavioral health challenge. HCD would not be required to award grants on a competitive basis.

Remainder Would Be Used for Beds in Community-Based Treatment Settings and Residential Care Settings. Bond proceeds remaining after distribution to HCD—at least $3.8 billion—would be used for DHCS to award grants to construct and rehabilitate beds in unlocked, voluntary, community-based treatment and residential care settings. The bond would not fund acute-care psychiatric facilities. DHCS could choose whether to require matching funds or real property as a condition of receiving a grant.

Assessment and Issues for Legislative Consideration

Bond Appears Broadly Reasonable and Worthy of Consideration…

Proposal Addresses Well-Documented Need That Is a Legislative Priority. The state has previously funded housing and homelessness programs for veterans and others with behavioral health needs. Similarly, the state has recently created the BHCIP to fund additional behavioral health facilities. The shortage in both housing and behavioral health facilities is well documented and a pressing need. Addressing these issues is a priority for the Legislature. As such, we think it is appropriate for the state to have a role in funding the types of projects proposed to be funded by the bond. The facilities and housing units would provide a public benefit over a multi-decade period. Thus, we think financing the projects with a bond and asking future taxpayers to share in the costs to develop the funded infrastructure is reasonable. In our view, these elements of the Governor’s proposed bond are broadly reasonable.

…But Also Raises Questions for Legislative Consideration

How Would Local Governments Fund Ongoing Costs to Support Permanent Housing? The veterans housing portion of the bond is intended to support permanent housing development for veterans and others who are experiencing or at risk of homelessness and are living with a behavioral health challenge. Accordingly, local entities would be responsible for funding the ongoing costs associated with maintaining the properties and providing any associated services to occupants. Local entities’ capacity to fund such new ongoing costs is unclear and calls into question the state’s ability to preserve these units in the long term. The Legislature may wish to ask the administration for its perspective on the local capacity to fund these new ongoing costs and what oversight of services and maintenance would be provided.

To What Extent Do Recent Budget Augmentations Address Estimated Shortage of Behavioral Health Facilities? The RAND study was conducted in late 2021, around the time when the state began to infuse the behavioral health system with billions of dollars. We understand that the administration’s intent is for the bond to address the remaining shortage after the BHCIP has run its course. In addition, the RAND researchers identified other factors that could reduce the estimated shortfall over time—notably, the availability of mobile crisis response teams, which are being implemented as a Medi-Cal benefit. In considering the Governor’s proposal, the Legislature may wish to ask the administration for detailed estimates of the extent to which recent state efforts are expected to address the shortage of behavioral health facilities and how the bond would fill in remaining gaps.

What About Behavioral Health Facilities for Children and Adolescents? The RAND study focused on the adult psychiatric and community residential bed shortage and specifically excluded needs for children and adolescents from the scope of research. The administration has noted that the bond could be used to fund community residential beds for children and youth. The Legislature may wish to ask the administration about the extent, if any, of a shortage of beds for children and adolescents and to what degree the administration anticipates using bond proceeds to fund beds focused on this population.

What About the Shortage of Acute Psychiatric Beds? By focusing on unlocked, voluntary, community-based treatment and residential care settings, the Governor’s proposed bond would not address the nearly 2,000 acute bed shortage identified by RAND. As such, the bond itself seemingly would do comparatively little for the North San Joaquin Valley and North Coast regions where the acute bed shortfall is greatest but where the need for other bed types is relatively small. The administration has indicated that the BHCIP is intended to address the shortage in acute beds. The Legislature may wish to request more detail from the administration on how it plans to address the acute bed shortage.

Will New Behavioral Health Facilities Reach Hard-to-Place Populations? RAND found that challenges with placing certain populations—those with co-occurring conditions, such as a traumatic brain injury, certain justice-involved individuals, and individuals with unique needs—can result in bottlenecks in the behavioral health system. The RAND researchers recommended that facilities be added to the behavioral health system with these populations in mind. The Legislature may wish to ask the administration how the beds funded by the bond would address these particular challenges.

Weighing Proposal Against Other Funding Priorities

No One “Right” Level to Spend on Infrastructure. The amount of infrastructure spending should reflect the state’s priorities for infrastructure compared with other state spending. Authorizing General Fund-supported bonds, however, obligates future General Fund resources for those bonds, meaning that fewer resources will be available in the future for other priorities.

Proposal to Fund Behavioral Health Facilities With General Obligation Bonds Is a Novel Approach. While general obligation bonds are a common tool for financing infrastructure in K-12 and higher education, resources, transportation, housing, and other areas, the state has very little experience with using such bonds to finance health facilities. Funding health infrastructure with General Fund-supported bonds may put pressure on the state in the future to use bonds to fund similar health infrastructure. For example, hospitals have long cited the financial challenges associated with meeting state seismic safety standards, which have resulted in multiple delays in the enforcement of these standards. The state could face additional pressures to use bond funding to cover a portion of these costs, which currently are not a state responsibility. The Legislature will want to weigh this precedent-setting action carefully.

Consider Where Proposal Ranks Among Bonds Currently in Legislative Process. With the state budget condition tightening this year and bond debt service costs at a relatively low level, it is understandable that the Legislature may want to look to bond financing for certain infrastructure priorities. That said, the Legislature will want to prioritize among the various bond proposals that are currently under consideration. The Legislature will also want to consider leaving some capacity for additional bonds in the coming years, as a currently unanticipated need could arise and a voter-approved bond commits General Fund resources for multiple decades.

Consider Reprogramming Recent Commitments. In recent years, and in particular in the 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 budget packages, the state made tens of billions of dollars in one-time or temporary commitments. While much of the funding has been encumbered or liquidated, a significant share remains available to reprioritize. Should the Legislature agree with the Governor that this proposal is a funding priority, given the constrained budget situation and competing priorities for bond dollars, the Legislature may wish to consider the extent to which temporary commitments in recent budgets could be reprogrammed for this purpose.

Legislative Role in Bond Implementation and Oversight

Governor’s Proposal Would Give Administration Broad Latitude in Implementing the Bond. While the administration generally has a broad plan for administering the bond funds, many key details are missing from the statutory proposal. For example, while we understand that the administration plans to base grant eligibility on recent housing and behavioral health programs, the statutory proposal is silent on what types of entities, such as public agencies and private entities, could receive grants from the proceeds of the bond. Other details that are missing from the statutory proposal include the methodology for allocating grant funds, the anticipated implementation time line, the extent to which a portion of the bond proceeds would be set aside for veterans housing, and the prioritization of bond proceeds for various types of behavioral health facilities. The statutory proposal defers to the administration key decisions such as whether matching funds or real property should be required as a condition of receiving grants for behavioral health facilities. The statutory proposal also continuously appropriates the bond proceeds, meaning the administration would not have to seek further authority from the Legislature to award behavioral health facility and veterans housing grants.

Important for Legislature to Have Active Role in Implementation. Data limitations and the limited scope of the RAND study make the precise extent of the shortfall in behavioral health facilities uncertain in terms of facility types, target population (adults versus children and adolescents), and geographical region. In addition, recent state efforts have already begun to fund new behavioral health facilities, making the shortage a moving target. These efforts include the BHCIP, which has awarded $1.6 billion in behavioral health infrastructure grants, and mobile crisis response teams, which are being implemented as a Medi-Cal benefit and can help to alleviate the need for behavioral health facilities. The Legislature will want to have an ongoing and active role in monitoring these developments and potentially adjusting the focus of the bond to ensure the dollars are targeted at the areas of highest need.

Recommend Increased Legislative Role in Bond Implementation and Oversight. Should the Legislature agree with the Governor that this bond proposal should be prioritized this year, we recommend that the Legislature amend the statutory proposal to provide more direction to the administration and ensure an ongoing legislative role in the bond’s implementation. First and foremost, this should include making the bond funds subject to appropriation in the annual budget act rather than the proposed continuous appropriation. Requiring the administration to submit proposals to spend the bond proceeds will help the Legislature ensure that the administration is on the right track in its targeting of funds. In addition, the Legislature will want to consider having an increased role—either by providing more direction in AB 531 or tabling certain key decisions for the second year of the legislative session—in determining:

The types of entities eligible for grants.

The methodology for allocating grant funding.

The extent to which bond proceeds should be spent on veterans housing versus behavioral health facilities.

Any required legislative approval to transfer funds between the HCD and DHCS administered portions of the bond.

Whether matching funds or real property should be required as a condition of receiving grants for behavioral health facilities and whether HCD should be required to award grants on a competitive basis.

The Legislature will also want to consider oversight and reporting requirements to gauge the extent to which the bond is meeting legislative goals now and in the future.

Conclusion

Governor’s Proposed Bond Merits Consideration, but Larger Role for Legislature Needed. The Governor’s proposed bond uses an appropriate funding mechanism to address a well-documented need for behavioral health facilities and veterans housing—priority areas for the Legislature. The Governor’s proposal is broadly reasonable and merits legislative consideration. The proposed bond, however, could set new expectations for the state in funding future health infrastructure, which the Legislature will want to consider carefully. The Governor also proposes a limited role for the Legislature in the design and implementation of the bond. We recommend amendments that would ensure the Legislature would have an active and ongoing role in ensuring the bond’s success.