November 8, 2023

Overview and Update on the

Prison Receivership

- Summary

- Receivership Established in 2006

- Changes to Prison Medical Care Under the Receivership

- Changes in Prison Medical Care Spending and Staffing Under the Receivership

- Exiting the Receivership—Steps Specified by Federal Court

- Issues for Legislative Consideration

Summary

California’s prison medical system has been under direct management of a Receiver appointed by a federal court since 2006 because the state was found to be providing unconstitutional levels of care in a case now referred to as Plata v. Newsom. Since the establishment of the Receivership, the Receiver has implemented significant changes in the delivery of prison medical care in order to bring the state into compliance with constitutional standards. In this brief, we provide an overview of the establishment of the Receivership and the key changes to prison medical care made by the Receiver to date. In addition, we provide a summary of the key steps that the state needs to complete in order to exit the Receivership as outlined by the federal court. Finally, we raise some issues for legislative consideration related to the Receivership.

Receivership Established in 2006

Federal Court Found State Provided Inadequate Prison Medical Care. In 2001, a class‑action lawsuit, later renamed Plata v. Newsom, was filed in federal court contending the state violated the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution prohibiting cruel and unusual punishment by providing inadequate medical care in the state’s prisons. The state agreed in 2002 to take a series of actions to address the deficiencies in order to settle the case. These actions included hiring additional medical staff, auditing prison medical records, and staffing emergency clinics in prisons 24 hours a day year‑round. An estimated $194 million was added to the state budget from 2002‑03 through 2006‑07 to address the problems identified in prison medical care. However, upon further review of the state’s performance, the federal court found that the state had failed to comply with its orders. Specifically, the court found, among other problems, that the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) prison medical system was poorly managed; provided inadequate access to medical care; had deteriorating facilities and disorganized medical record systems; and lacked sufficient qualified physicians, nurses, and administrators to deliver medical services. The court concluded that, on average, one person died every week in state prisons and that many more had been injured by the lack of reliable access to quality medical care. In addition, a federal three‑judge panel—created at the request of plaintiffs in both the Plata case and the case now known as Coleman v. Newsom (involving prison mental health care)—in 2009 ruled that the state must reduce prison overcrowding as it was the primary reason that CDCR was unable to provide adequate health care, which was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court. (See the box below for additional details on this ruling.)

Federal Court Orders State to Reduce Prison Overcrowding

In November 2006, plaintiffs in the cases now known as Plata v. Newsom (involving prison medical care) and Coleman v. Newsom (involving prison mental health care) filed motions for the federal courts to convene a three‑judge panel pursuant to the U.S. Prison Litigation Reform Act to determine whether (1) prison overcrowding was the primary cause of the California Department of Correction and Rehabilitation’s (CDCR’s) inability to provide constitutionally adequate prison health care and (2) a prison release order was the only way to remedy these conditions. In August 2009, the three‑judge panel declared that overcrowding was the primary reason that CDCR was unable to provide adequate health care. Specifically, the court ruled that, in order for CDCR to provide such care, overcrowding would have to be reduced to no more than 137.5 percent of the design capacity of the prison system. (Design capacity generally refers to the number of beds that CDCR would operate if it housed only one person per prison cell and did not use bunk beds in dormitories.) At the time of the three‑judge panel ruling, the state prison system was operating at roughly 188 percent of design capacity—or about 39,000 people more than the limit established by the three‑judge panel. Since that time, the state implemented various policy changes—such as shifting responsibility for various felony populations from the state to the counties through the 2011 realignment—that significantly reduced the prison population. As a result of these actions, the state prison population has been below the 137.5 design capacity limit since February 2015. As of August 30, 2023, the state’s prison population is about 14,000 people below the limit established by the court.

Federal Court Appointed Receiver to Take Over Management of State Prison Medical Care. In February 2006, a few years prior to the state’s fiscal crisis caused by the Great Recession, the federal court appointed a Receiver to take over the direct management and operation of the state’s prison medical system from CDCR. The appointment of a Receiver is a legal remedy in lawsuits seeking to reform jails and prisons that is typically used as a last resort by courts. Courts appoint a Receiver in order to place a neutral expert in control of some aspect of prison or jail operations. The Receiver appointed by the Plata court has a mandate to bring the department’s provision of medical care into compliance with federal constitutional standards. To do so, the federal court suspended the authority of the Secretary of CDCR for prison medical care and provided the Receiver with executive authority in hiring and firing medical staff, entering contracts with community providers, and acquiring and disposing of property. In addition, the court granted the Receiver the authority to “determine the annual CDCR medical health care budgets” and to spend money to implement changes in medical care. The court requires the state to pay “all costs incurred in the implementation of the policies, plans, and decisions of the Receiver.” In addition, the Receiver has the authority to seek waivers through the court of any state or contractual requirements that are impeding progress in improving the prison medical system. However, the creation of the Receivership did not change the Legislature’s role of authorizing positions and appropriating funds for, enacting legislation related to, or exercising oversight of prison medical care. For example, each year the Receiver requests funds for proposals through the budget process. The Legislature can and has made changes to these proposals. However, the Receiver may request a court order to require the state to provide funding for proposals in cases where the Receiver believes it to be necessary.

Changes to Prison Medical Care Under the Receivership

To remedy the issues identified by the courts, the Receiver has changed various aspects of prison medical care. Many of the changes received funding through the state’s annual budget process. Below, we highlight a few of the significant changes to prison medical care under the Receivership (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Significant Changes to

Prison Medical Care Under Receiver

|

✓ Construction of Various Health Care Facilities |

|

✓ Creation of Integrated Substance Use Disorder Treatment Program |

|

✓ Implementation of Information Technology Improvements |

|

✓ Changes to Pharmaceutical Services |

|

✓ Changes to Improve Recruitment and Retention |

|

✓ Changes to Supervision of Prison Medical Care Staff |

|

✓ Initiation of Office of Inspector General Medical Inspections |

Construction of Various Health Care Facilities. Among the obstacles to providing a constitutional level of care identified by the court were inadequate and insufficient health care facilities. In order to address this, the Receiver initiated the construction of health care facilities throughout the prison system. These projects were funded both directly from the General Fund and borrowing through lease revenue bonds, which are gradually repaid with interest each year from the General Fund. Some of the major facility initiatives include:

- Health Care Facility Improvement Program (HCFIP)—$1.5 Billion. HCFIP is a collection of 31 projects at various prisons to address medical infrastructure deficiencies across the state prison system. According to the Receiver, these projects are necessary to support timely, competent, and effective health care delivery. Projects vary in scope and have included construction of new medical buildings that expand treatment capacity; renovation of existing buildings; and ancillary improvements at facilities, such as adding clinic workstations for staff or creating soiled and clean utility rooms for infection control. The first project started in 2007 and all projects were originally scheduled to be completed by 2017. However, the projects have required numerous changes from their original design due to various factors, including errors during the design process and other changes necessary to bring the projects into compliance with fire, life, and safety requirements. As a result, 22 of the 31 projects are currently complete, with the remainder expected to be completed by 2025. The state has authorized a total of about $1.5 billion, primarily in lease revenue bonds, for these projects.

- California Health Care Facility (CHCF)—$900 Million. CHCF in Stockton was designed to provide care to people with the most severe medical and mental health conditions in prison. At the time of construction, the Receiver indicated the facility was necessary to increase CDCR health care capacity and create efficiencies by consolidating the population needing the highest levels of care. The facility has a design capacity of about 3,000 beds largely for medical and mental health services in both inpatient and outpatient settings. The construction of CHCF started in 2011 and was completed in 2013. The state authorized about $900 million in lease revenue bonds for the project and spends about $660 million annually to operate the facility.

- Medication Rooms—$90 Million. Medication rooms are rooms inside of or near housing units where medication is prepared and/or distributed to patients. Since being appointed, the Receiver has identified various shortcomings with CDCR’s medication rooms. As a result, medication rooms are being constructed or improved at most prisons in two phases. Phase one started in 2012 and is expected to be completed before the end of 2023. Phase two is currently underway with the last project expected to be complete by the end of 2024. The state has dedicated a total of about $90 million for the two phases.

Creation of Integrated Substance Use Disorder Treatment Program (ISUDTP). ISUDTP was first funded for systemwide implementation in 2019‑20 to provide a continuum of care to people in prison to address their substance use disorder (SUD) and other rehabilitative needs. This program was spearheaded by the Receiver and received funding for medical positions to support the implementation. Prior to ISUDTP, CDCR generally assigned people to SUD treatment based on whether they had a “criminogenic” need for the program—meaning the person’s SUD could increase their likelihood of recidivating (committing a future crime) if unaddressed through rehabilitation programs. In contrast, ISUDTP is designed to transform SUD treatment from being structured as a rehabilitation program intended to reduce recidivism into a medical program intended to reduce SUD‑related deaths, emergencies, and hospitalizations. For example, under ISUDTP, medication assisted treatment is made available at all prisons to people with an assessed SUD need. The state currently spends about $281 million annually on ISUDTP.

Implementation of Information Technology (IT) Improvements. The federal court found that the IT (such as electronic files that track appointments) to complete essential medical care tasks was “practically non‑existent” in California prisons. To address these deficiencies, the Receiver procured various IT systems. The largest of the IT projects was the Electronic Health Record System (EHRS). The EHRS was developed to provide an electronic health record for each patient that would (1) be available at all prisons, (2) eliminate the need for paper files that must be transported between prisons, (3) provide real‑time data on the level of care provided, and (4) standardize and coordinate medical record entries that were previously difficult to access in the paper‑based system. Development of the EHRS began in 2013 and was first implemented statewide in 2017, with additional improvements to the system in later years. The has state dedicated a total of about $400 million to the project including the addition of functionality after completion. The state spent about $34 million in 2022‑23 to operate the EHRS, including maintenance and vendor licensing fees.

Changes to Pharmaceutical Services. When establishing the Receivership, the federal court found that there were “serious, long‑standing problems with dispensing medication, renewing prescriptions, and tracking expired prescriptions” and that chronically ill patients were not able to refill their prescriptions in a timely manner. To address these deficiencies, the Receiver took several steps to standardize and centralize pharmaceutical practices across the prison system. For example, the Receiver established a drug formulary to improve consistency in prescribing practices and introduced a central‑fill pharmacy to coordinate pharmaceutical services across prisons. Notably, from 2004‑05 (the year before the Receivership) through 2021‑22 (the most recent year for which complete data exist), the pharmaceutical budget increased from $212 million to $319 million after adjusting for inflation—an increase of 50 percent. (The pharmaceutical budget reflects only the cost of pharmaceuticals and not the cost of medication management or administration.) The level of inflation‑adjusted spending on pharmaceuticals per person also increased over this time period from $1,300 in 2004‑05 to $3,200 (more than double) by 2021‑22.

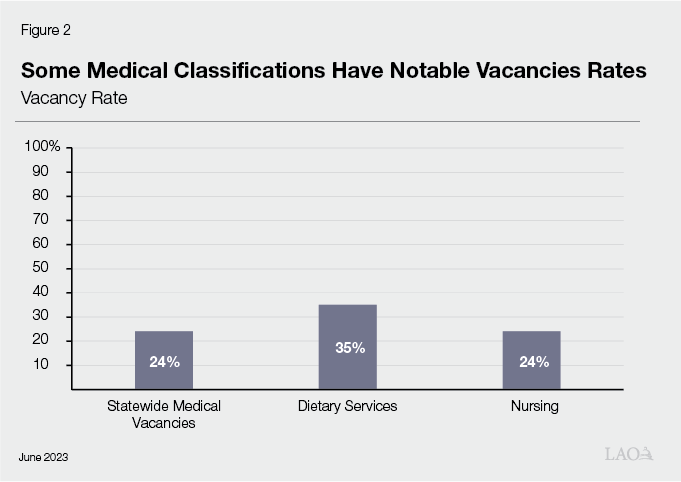

Changes to Improve Recruitment and Retention. The court expressed concern about vacancy rates in medical positions and noted that there were vacancy rates as high as 80 percent for registered nurses at some prisons. To reduce the chronic medical vacancies, the Receiver increased salaries across several medical positions to be more competitive and to improve recruitment and retention. In order to expedite the salary increases that are typically subject to bargaining agreements between the state and a union, the Receiver used executive authority to waive state laws and regulations in 2006 to increase the compensation levels of medical staff between 5 percent and 64 percent. For example, the Receiver increased physician base pay from $150,000 to as much as $300,000. The state provided about $30 million in 2007‑08 for these salary increases. The Receiver has also increased work flexibility to improve recruitment, such as expanding the use of telemedicine in CDCR, which is the delivery of health care via interactive audio and video technology. This allows staff to be hired in areas where medical providers are easier to recruit while allowing such providers to treat people in remote prisons. The efforts to improve recruitment and retention have resulted in reduced vacancies, though CDCR still has difficulty recruiting permanent state civil service employees. This has often required the Receiver to rely on contract staff—rather than permanent state civil service employees—to address workload when there are vacancies. Despite the use of contract staff, vacancies in many medical positions remain notably high, as shown in Figure 2.

Changes to Supervision of Prison Medical Care Staff. The federal court found “that the lack of supervision in the prisons is a major contributor to the crisis in CDCR medical delivery.” Accordingly, the Receiver has established about 200 new executive medical positions to oversee medical operations within prisons and statewide. In doing so, the Receiver geographically grouped prisons to establish prison health care regions. Each region was established with dedicated staff to provide oversight, coordination, and additional support to the prisons in the region. In addition, at both the prison and headquarter level, the Receiver created managerial positions to establish more clear lines of accountability among the health care staff working in the prisons. Additionally, the processes for providing supervision to medical staff changed as well. For example, the Nursing Professional Practice Program was established to evaluate nursing staff and review any departures from standards in prison nursing care.

Initiation of Office of Inspector General (OIG) Medical Inspections. At the request of the federal court and the Receiver, the OIG—which is tasked with conducting various types of oversight of CDCR—developed an inspection program to evaluate the quality of medical care at each prison. These inspections result in the care at each prison being classified as proficient, adequate, or inadequate and serve as an additional tool for the Receiver to monitor medical care. In 2008, the OIG began its statewide inspections using teams of physicians, registered nurses, deputy inspector generals, and analysts. In 2011, the Legislature codified in statute the OIG’s medical inspection function. To date, the OIG has completed six audit cycles. As of October 2023, there are no prisons categorized as proficient, 23 as adequate, and 11 as inadequate. While the state has spent about $3.8 million annually on the medical inspection unit, the 2022‑23 budget included an additional $3.3 million annually for three years to increase staffing in order to reduce the amount of time medical inspections take to complete. The OIG reports that this funding will allow it to complete an audit cycle in two rather than three years.

Changes in Prison Medical Care Spending and Staffing Under the Receivership

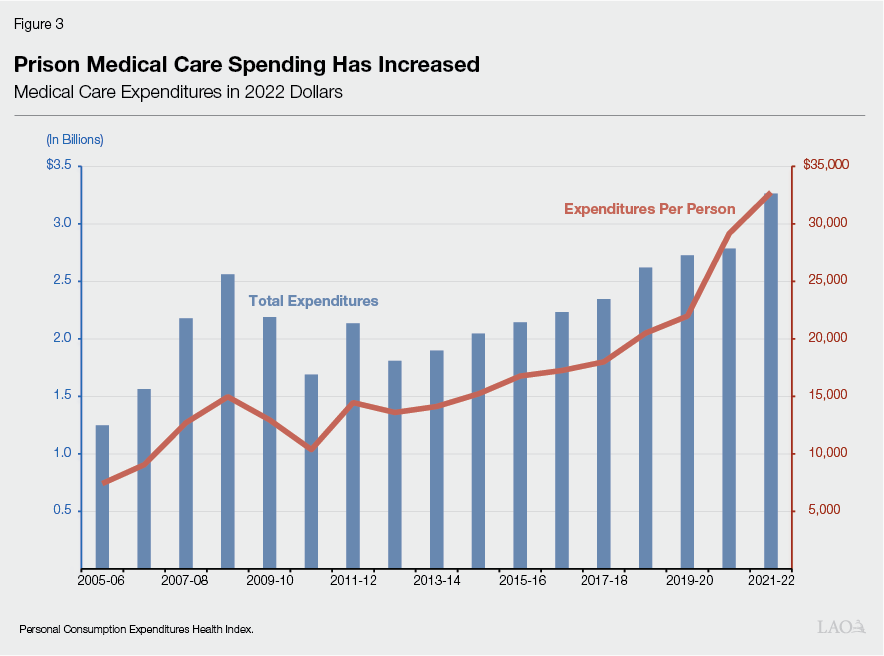

State Spending Has Increased Substantially Since the Receivership. As a result of the various changes initiated by the Receiver, including those discussed above, state spending on prison medical care has increased substantially since 2005‑06 (the first year of the Receivership). The state spent about $1.3 billion from the General Fund—about $7,400 per person in prison—on medical care in 2005‑06, adjusted for inflation. In contrast, the state spent about $3.3 billion (more than double) and $32,700 per person (four times more) in 2021‑22. (We note that about $170 million of this increase is due to spending related to the COVID‑19 pandemic in 2021‑22.) As shown in Figure 3 below, inflation‑adjusted spending on medical care increased every year over this time period, with the exception of 2009‑10 and 2010‑11—when spending was reduced in response to the Great Recession—and 2012‑13—when spending declined due to a reduction in the prison population associated with the 2011 realignment.

Prison Medical Staffing Has Also Increased Substantially. A significant portion of the increased spending is related to increases in staffing. This is because the number of prison health care positions (including medical staff such as doctors and nurses) per person in prison has dramatically increased. Specifically, CDCR staffing of health care positions has increased from about 3 positions for every 100 people in prison in 2005‑06 to about 15 positions for every 100 people in 2021‑22.

Exiting the Receivership—Steps Specified by Federal Court

Several orders have been issued by the Plata court outlining the benchmarks that must be met for the state to take full responsibility for prison medical care back from the Receiver. The most recent court order, issued in October 2021, supersedes the previous orders and clarifies the current procedure to end the Receivership and terminate the Plata court case. Below, we summarize the steps that the court has indicated the state must complete before exiting the Receivership.

State Must Adopt Laws and Regulations to Reduce or Eliminate Need for Waivers. When the Receivership ends, the executive authority used by the Receiver to waive state laws and regulations will expire. Accordingly, the October 2021 order specifies that the state and the Receiver shall implement any changes in laws and regulation necessary to eliminate the need for the waivers implemented by the Receiver as much as possible. As such, there may need to be various changes made to CDCR regulations and state law prior to the end of the Receivership. For example, the Plata court waived laws that specify disciplinary proceedings of state employees and established new policies related to the delivery of prison medical care as proposed by the Receiver. It is possible that some of the changes will be need to be made permanent through modification to statute or regulations.

Receiver Must Delegate Responsibility for Each Prison Back to the State. Over the past decade, the court has refined the process for assessing the adequacy of medical care at individual prisons. The current process requires plaintiffs in the Plata case, CDCR staff, and the Receiver to meet and confer on whether responsibility for medical care at a specific prison is ready to be delegated back to the state. The Receiver identifies which prisons are suitable for these meet and confer discussions based on regular reviews of about 25 medical care indicators, including the OIG’s medical inspection reports and medical care data collected by CDCR staff. After the parties meet and confer, the Receiver determines whether a prison is adequately providing medical care and can continue to do so without the direct management of the Receiver. If the Receiver decides that a prison meets these criteria, the responsibility for medical care at the prison is restored back to the Secretary of CDCR. Otherwise, the prison’s provision of medical care continues to be managed by the Receiver. As shown in Figure 4, the Receiver has delegated responsibility for care at 21 prisons to date. (We note that one of these prisons has been deactivated and two are scheduled to be deactivated.)

Figure 4

Prisons Delegated Back to State

|

2015 |

Folsom State Prison |

|

2016 |

Correctional Training Facility |

|

Chuckawalla Valley State Prisona |

|

|

California Correctional Institution |

|

|

Pelican Bay State Prison |

|

|

Centinela State Prison |

|

|

Sierra Conservation Center |

|

|

California Institution for Men |

|

|

Avenal State Prison |

|

|

2017 |

San Quentin Rehabilitation Center |

|

California Institution for Women |

|

|

Kern Valley State Prison |

|

|

California City Correctional Facilityb |

|

|

Pleasant Valley State Prison |

|

|

Calipatria State Prison |

|

|

2018 |

California Correctional Centerc |

|

California Men’s Colony |

|

|

Valley State Prison |

|

|

California State Prison Corcoran |

|

|

2022 |

Wasco State Prison |

|

2023 |

Ironwood State Prison |

|

aTo be deactivated in 2025. bTo be deactivated in 2024. cDeactivated in 2023. |

|

Receiver Must Delegate Responsibility for Headquarter and Systemwide Medical Functions Back to the State. In addition to delegating responsibility for care at individual prisons back to the state, the Receiver must also delegate all existing headquarter and systemwide functions under the authority of the Receivership back to the state. The Receiver’s staff indicated that 14 headquarter and systemwide functions remain to be delegated. Some of these systemwide functions include managing and overseeing prison medical and nursing services, human resources activities, as well as quality and risk management. To date, the Receiver has delegated two systemwide functions: construction and activation of prison health care infrastructure and the procurement of medical vehicles. However, no additional systemwide delegations have happened since 2012. Based on conversations with Receiver staff, the Receiver could delegate responsibility for headquarter and systemwide functions on a piecemeal basis or all at once.

Receivership Ends One Year After Delegations and After Post‑Receivership Plan Established. After delegation of individual prisons as well as headquarter and systemwide functions to the state, the Receiver continues to monitor them for compliance and has the ability to revoke any delegation granted. Within 30 days of the Receiver certifying that all prisons, headquarter, and systemwide functions have been delegated back to the state, the state must file a post‑Receivership plan with the court outlining how the state will maintain a system of providing constitutionally adequate medical care. The 2021 court order encouraged the parties to begin meeting and conferring on such a plan. If the Receiver leaves all delegations in place for one year after certifying all delegations—and the plaintiffs do not raise additional objections at least 120 days before that year is over—the Receivership and the Plata v. Newsom case will end.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

Below, we provide issues for the Legislature to consider as it continues to monitor prison medical care under the Receiver. We also raise other issues for consideration as the state moves closer to exiting the Receivership.

Time Line for End of Receivership Unclear. Although notable progress has been made by the state, the following factors make it difficult to pinpoint exactly when the Receivership could end:

- Delegation of Care at Remaining Prisons Could Be Lengthy Process. The Receiver would be unlikely to delegate care at a prison found by OIG to be inadequate. Accordingly, when a prison is found to be inadequate—as California State Prison, Sacramento was in October 2022—it will not likely be delegated until OIG finds it to be adequate. However, under the OIGs current approach to inspections, such a prison will not be reviewed again for roughly two years. Moreover, the prisons that remain to be delegated will likely be those most in need of improvement. As such, these prisons could take longer to reach constitutional levels than those that have already been delegated.

- Unclear When Delegation of Headquarter and Systemwide Functions Could Occur. The most recent court order does not outline a detailed process for delegating headquarter and systemwide functions. According to the Receiver’s staff, the court provides the Receiver with discretion in delegating those functions. As a result, there is no way to estimate how close the Receiver is to delegating such functions back to the state.

- Further Health Care Infrastructure Delays Could Extend Receivership. As previously discussed, health care infrastructure projects—most notably the HCFIP projects—have required numerous changes from their original design due to errors and these changes have led to substantial delays and cost increases. Receiver staff have indicated that the infrastructure projects are an important factor in determining whether CDCR is able to provide constitutionally adequate care. To the extent there are further delays in HCFIP projects, medication rooms, or other construction projects, it could delay delegations of care at individual prisons, which could extend the Receivership.

Despite it being unclear when the Receivership will end, the Legislature can exercise oversight to ensure the state is progressing toward the benchmarks specified by the courts. For example, the Legislature could request periodic updates from the Receiver at budget hearings on various issues such as planned meet and confer dates and the development of a post‑Receivership plan. Such hearings could help the Legislature oversee and facilitate the end of the Receivership.

Ensure Legislative Priorities Are Reflected in Post‑Receivership Plan. As mentioned above, CDCR will need to develop a post‑Receivership plan for the court to approve. Because this plan is supposed to guide prison medical care delivery after the end of the Receivership, it will likely have significant fiscal and policy implications for CDCR. Accordingly, the Legislature should ensure that any post‑Receivership plan developed and implemented by the administration is consistent with its priorities and allows for sufficient legislative oversight going forward. To do so, the Legislature could require that the administration (1) provide updates at various stages of the development of the proposed plan and (2) submit the plan to the Legislature prior to its submission to the court along with an estimate of the cost of implementing the plan. This would allow the Legislature an opportunity to ensure prison medical care is delivered in a manner consistent with its priorities following the end of the Receivership.

Prison Medical Care Will Likely Require Ongoing Independent Oversight Post‑Receivership. After the Receivership ends, there will likely be a need for some level of independent oversight and evaluation of the prison medical care provided by CDCR. Failure to establish effective oversight mechanisms could limit the ability of the Legislature to ensure that emerging problems are addressed early and the quality of prison medical care is maintained. This could result in renewed litigation. Moreover, we expect that the establishment of independent oversight will also be a priority of the federal court. Given that the OIG already conducts prison medical inspections and audits, it could make sense for the OIG to continue to provide this external oversight following the Receivership. However, there are other forms of oversight that could supplement or replace the OIG’s medical inspection monitoring. For example, the state could rely on medical accreditation as a form of oversight. The accreditation process uses an external, independent body that applies standardized criteria to ensure that organizations provide care consistent with the criteria. Once accredited, an organization must continue to meet the quality standards every audit cycle to maintain its accreditation. The 2023‑24 budget includes $3.2 million (increasing to $6.1 million annually in 2027‑28) to support accreditation from The Joint Commission, which accredits about 80 percent of U.S. hospitals for various types of health care services.

Medical Staffing Could Continue to Be a Challenge. As discussed above, hiring and retaining sufficient permanent state civil service medical staff has been a challenge for CDCR including during the Receiver’s tenure. This is at least partially due to the fact that statewide shortages have been identified for some of the medical classifications CDCR has trouble recruiting, such as nurses. Accordingly, it is possible that these challenges will persist post‑Receivership. To the extent that the department is not able to maintain sufficient medical staff, it could present a barrier to maintaining adequate care. As such, the Legislature will want to continue to provide oversight in this area. Some key metrics that the Legislature could monitor to assess recruitment and retention challenges in the medical workforce include vacancy, turnover, and tenure rates; the number of qualified applicants to jobs; and well‑designed compensation studies comparing CDCR pay and benefits to those offered by other medical care providers. Monitoring such metrics could help the Legislature identify factors potentially contributing to recruitment and retention difficulties and address issues as they are identified. (We note that under Chapter 890 of 2023 (SB 525, Durazo), the minimum wage for certain health care facility employees in both the private and public sectors will increase beginning in June 2024. This will increase CDCR staffing costs. While this could have an effect on prison medical vacancies, the effect is unclear at this time.)

Prison Medical Care Infrastructure Will Need to Be Considered Amid Prison Deactivations. As discussed above, the state implemented various policy changes that significantly shrank the prison population, allowing it to achieve compliance with the federal three‑judge panel court order on prison overcrowding. As a result of this decline in the population, the state has deactivated two prisons, is in the process of deactivating two more, and will likely be in a position to deactivate additional prisons in the future. While deactivating prisons can create significant savings for the state, it can also affect the department’s ability to deliver adequate medical care in the remaining prisons to the extent prisons with unique health care infrastructure are deactivated. For example, the California Health Care Facility is critical to delivering adequate care. Accordingly, the Legislature will want to ensure that any future prison deactivations consider the medical needs of the prison population such that the state can maintain the infrastructure necessary to provide constitutionally adequate medical care.