LAO Contact

December 7, 2023

The 2024‑25 Budget

California’s Fiscal Outlook

- Introduction

- California Entered a Downturn Last Year

- The Budget Problem

- Solving the Budget Problem

- Comments

- Appendix 1: Outlook for School and Community College Funding

- Appendix 2

Executive Summary

California Faces a $68 Billion Deficit. Largely as a result of a severe revenue decline in 2022‑23, the state faces a serious budget deficit. Specifically, under the state’s current law and policy, we estimate the Legislature will need to solve a budget problem of $68 billion in the upcoming budget process.

Unprecedented Prior‑Year Revenue Shortfall Creates Unique Challenges. Typically, the budget process does not involve large changes in revenue in the prior year (in this case, 2022‑23). This is because prior‑year taxes usually have been filed and associated revenues collected. Due to the state conforming to federal tax filing extensions, however, the Legislature is gaining a complete picture of 2022‑23 tax collections after the fiscal year has already ended. Specifically, we estimate that 2022‑23 revenue will be $26 billion below budget act estimates. This creates unique and difficult challenges—including limiting the Legislature’s options for addressing the budget problem.

Legislature Has Multiple Tools Available to Address Budget Problem. While addressing a deficit of this scope will be challenging, the Legislature has a number of options available to do so. In particular, the state has nearly $24 billion in reserves to address the budget problem. In addition, there are options to reduce spending on schools and community colleges that could address nearly $17 billion of the budget problem. Further adjustments to other areas of the budget, such as reductions to one‑time spending, could address at least an additional $10 billion or so. These options and some others, like cost shifts, would allow the Legislature to solve most of the deficit largely without impacting the state’s core ongoing service level.

Legislature Will Have Fewer Options to Address Multiyear Deficits in the Coming Years. Given the state faces a serious budget problem, using general purpose reserves this year is merited. That said, we suggest the Legislature exercise some caution when deploying tools like reserves and cost shifts. The state’s reserves are unlikely to be sufficient to cover the state’s multiyear deficits—which average $30 billion per year under our estimates. These deficits likely necessitate ongoing spending reductions, revenue increases, or both. As a result, preserving a substantial portion—potentially up to half—of reserves would provide a helpful cushion in light of the anticipated shortfalls that lie ahead.

Introduction

Each year, our office publishes the Fiscal Outlook in anticipation of the upcoming budget season. The goal of this report is to give the Legislature our independent estimates and analysis of the state’s budget condition as lawmakers begin planning the 2024‑25 budget. This year, this report has three key takeaways:

- California Faces a Serious Deficit. Largely as a result of a severe revenue decline in 2022‑23, the state faces a serious budget deficit. Specifically, under the state’s current law and policy, we estimate the Legislature will need to solve a budget problem of $68 billion in the coming budget process.

- Unprecedented Prior‑Year Revenue Shortfall. Typically, the budget process does not involve large changes in revenue in the prior year (in this case, 2022‑23). This is because prior‑year taxes usually have been filed and associated revenues collected. Due to the state conforming to federal tax filing extensions, however, the Legislature is only gaining a complete picture of 2022‑23 tax collections after the fiscal year has already ended. Specifically, we estimate that 2022‑23 revenue will be $26 billion below budget act estimates.

- Legislature Has Multiple Tools Available to Address Budget Problem. While addressing a deficit of this scope will be challenging, the Legislature has a number of options available to do so. In particular, the Legislature has reserves to withdraw, one‑time spending to pull back, and alternative approaches for school funding to consider. These options, along with some others, would allow the Legislature to solve most of the deficit largely without impacting the state’s core ongoing service level.

California Entered a Downturn Last Year

Higher Borrowing Costs and Reduced Investment Have Cooled California’s Economy. In an effort to cool an overheated U.S. economy, the Federal Reserve has taken actions over the last two years to make borrowing more expensive and reduce the amount of money available for investment. This has slowed economic activity in a number of ways. For example, home sales are down by about half, largely because the monthly mortgage to purchase a typical California home has gone from $3,500 to $5,400. Some effects of the Federal Reserve’s actions have hit segments of the economy that have an outsized importance to California. In particular, investment in California startups and technology companies is especially sensitive to financial conditions and, as a result, has dropped significantly. For example, the number of California companies that went public (sold stock to public investors for the first time) in 2022 and 2023 is down over 80 percent from 2021. As a result, California businesses have had much less funding available to expand operations or hire new workers.

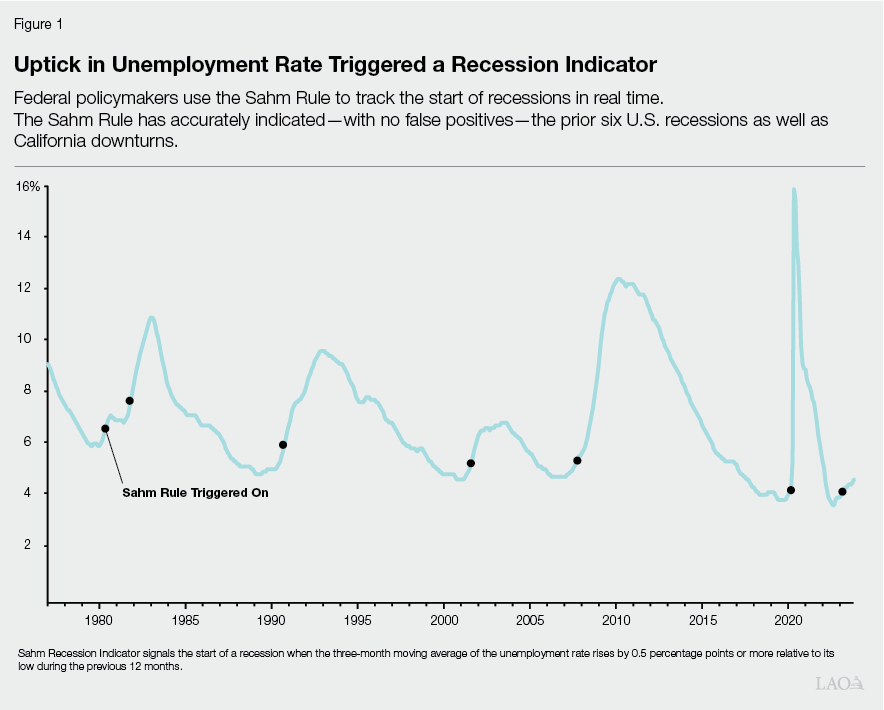

State’s Economy Entered a Downturn in 2022. These mounting economic headwinds have pushed the state’s economy into a downturn. The number of unemployed workers in California has risen nearly 200,000 since the summer of 2022. This has resulted in a jump in the state’s unemployment rate from 3.8 percent to 4.8 percent, as Figure 1 shows. Similarly, inflation‑adjusted incomes posted five straight quarters of year‑over‑year declines from the first quarter of 2022 to the first quarter 2023.

Recent Revenue Collections Show Impact of Economic Downturn. With the state’s conformity to federal actions postponing deadlines for tax payments on investment and business income for much of the past year, the state adopted the 2023‑24 budget without a clear picture of the impact of recent economic weakness on state revenues. Regardless, there have been signs of revenue weakness over the past year. The portion of income taxes collected directly from workers’ paychecks was down 2 percent over the last twelve months compared to the preceding year. Sales tax collections have been essentially flat, despite above‑average growth in consumer prices. The full extent of revenue weakness, however, came into full focus recently with the arrival of the postponed tax payments. With the deadline passed, collections data now show a severe revenue decline, with total income tax collections down 25 percent in 2022‑23. This decline is similar to those seen during the Great Recession and dot‑com bust. While the slowdown of investment in California companies and corresponding broader economic weakness likely were primary drivers of this decline, another important factor was financial market distress in 2022. Overall, the experience of the last few years suggests California’s economy and revenues are uniquely sensitive to Federal Reserve actions.

Significant Risk That Weakness Could Persist Into Next Year. Whether the recent weakness will continue is difficult to say. However, the odds do not appear to be in the state’s favor. Past downturns similar to this recent episode have tended to be followed by additional weakness. For instance, as Figure 1 shows, an increase in the unemployment rate similar to the recent period has consistently been followed by an extended period of elevated unemployment. Similarly, in the past, years with large revenue declines typically have been followed by an additional year of lackluster revenue performance. History does not always repeat itself and might not this time. Nonetheless, there is a significant risk the current weakness could continue into next year.

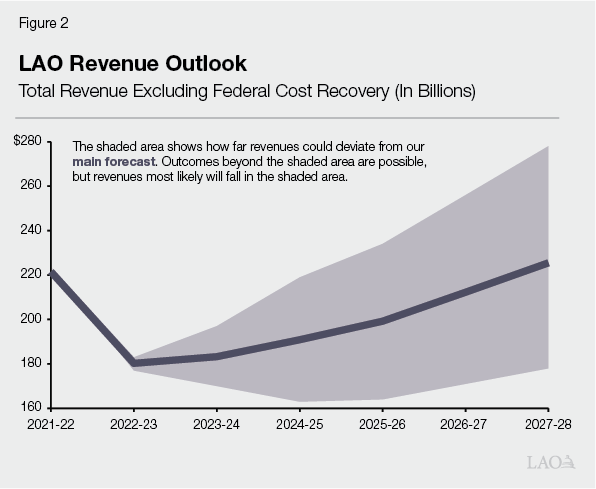

Revenue Outlook Reflects Risk of Continued Weakness. Reflecting the risk of continued weakness, our revenue outlook—shown in Figure 2—anticipates collections will be nearly flat in 2023‑24, after falling 20 percent in 2022‑23. Our outlook then has revenue growth returning in 2024‑25 and beyond. Based on this trajectory, our revenue outlook expects collections to come in $58 billion below budget act assumptions across 2022‑23 through 2024‑25, with about half of this difference ($26 billion) attributable to 2022‑23. As always, this forecast is highly uncertain. It is entirely possible that revenues could end up $15 billion higher or lower than our forecast for 2023‑24 and $30 billion higher or lower for 2024‑25.

The Budget Problem

Budget Year

In this section, we describe our estimates of California’s budget condition for the upcoming fiscal year: 2024‑25. We expect the state will face a serious deficit, also known as a budget problem. A budget problem occurs when resources for the upcoming budget are insufficient to cover the costs of currently authorized services.

State Faces a $68 Billion Deficit. Under current law and policy, we estimate the state faces a budget problem of $68 billion. Figure 3 reflects the budget problem in the 2024‑25 ending balance in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties. The budget problem is the net effect of the following factors:

- State Anticipated a Deficit of Around $14 Billion. The 2023‑24 Budget Act planned for a spending level in 2024‑25 that was higher than expected revenue collections. Put another way, last year’s budget planned for a deficit in 2024‑25. That anticipated deficit of $14 billion is the starting place for the upcoming budget process and therefore adds to the calculation of the budget problem.

- Revenues Are Lower Than Budget Act Projections by $58 Billion. As described earlier, collections data to date show a severe revenue decline, with total income tax collections down 25 percent in 2022‑23. Reflecting the risk of continued economic weakness, our forecast anticipates flat revenue growth for 2023‑24, with positive growth returning in 2024‑25 and beyond. Based on this trajectory, our revenue outlook expects collections to come in $58 billion below budget act assumptions across the budget window. This is the major driver of the budget problem.

- School and Community College Spending Is Lower by More Than $4 Billion. Proposition 98 (1988) establishes a minimum annual funding requirement for schools and community colleges, met with state General Fund and local property tax revenue. When General Fund revenue declines, the minimum requirement usually declines in tandem. Most school spending, however, does not automatically decrease when the minimum requirement drops in the current or prior year. As described in the text box below, the state could decide to reduce Proposition 98 General Fund spending by nearly $21 billion under our outlook, but the automatic reduction is about $4 billion. The budget problem is therefore lower by about $4 billion in our deficit calculation.

- Other Spending Is Lower by $4 Billion. We estimate spending across the rest of the budget will be lower than the administration’s June projections by about $4 billion over the budget window. The major driver of this difference is spending on health and human services (HHS) programs, where our estimates are lower by about $3 billion. We do not have department‑ or program‑level detail on the administration’s HHS spending forecast, so we cannot give more detail about the nature of this difference. This lowers the budget problem by a like amount.

- Entering Fund Balance Is Lower by $3 Billion. Budgetary changes to years before the budget window are reflected in the 2022‑23 entering fund balance. (These changes occur due to accounting rules, which sometimes result in the state “accruing” or attributing revenues or spending to earlier years, based on when the underlying economic activity is estimated to have occurred.) Our estimate of the budget problem reflects a $3 billion downward adjustment in the entering fund balance as a result of lower revenues. This adds to the budget problem.

- Reserve Deposits Are Higher by $400 Million. Proposition 2 (2014) requires the state to set aside minimum amounts to deposit into its reserve, pay down debts, and (under certain conditions) spend money on infrastructure. These requirements are determined by a set of relatively complex formulas. Ordinarily, the required set asides increase when revenues increase and drop when revenues decrease. This year, however, due to a variety of idiosyncratic issues, under current law and policy, the state’s reserve requirements would increase in response to our revenue forecast. The nearby box describes the reasons why. As we discuss later, in response to a budget emergency, the Legislature and Governor can decide to suspend these deposits and/or withdraw funds from the reserve.

Figure 3

General Fund Condition Under Fiscal Outlook

(In Millions)

|

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$52,561 |

$167 |

‑$32,792 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

179,961 |

189,062 |

193,255 |

|

Expenditures |

232,355 |

222,021 |

222,782 |

|

Ending Fund Balance |

$167 |

‑$32,792 |

‑$62,318 |

|

Encumbrances |

$5,272 |

$5,272 |

$5,272 |

|

SFEU balance |

‑$5,105 |

‑$38,064 |

‑$67,590 |

|

Reserves |

|||

|

BSA balance |

$21,515 |

$22,074 |

$22,809 |

|

Safety Net Reserve |

900 |

900 |

900 |

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties and BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

|||

Only Modest Automatic Spending Changes

in Response to Lower Revenues

State Has Two Constitutional Reserves with Formula‑Driven Requirements. Proposition 2 (2014) governs deposits into (and withdrawals from) the state’s two constitutional reserves: the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA), a general purpose reserve, and the Proposition 98 Reserve, which is dedicated to schools and community colleges. In both cases, reserve requirements tend to go up when revenues increase, particularly when capital gains taxes rise, and vice versa. These requirements are automatically adjusted in response to changes in revenue estimates and both reserves have maximum thresholds. In the case of the BSA, requirements above the maximum threshold must be spent on infrastructure instead. In the case of the Proposition 98 Reserve, reserve withdrawals are sometimes required, especially in tighter fiscal times.

Proposition 2

This Year, Most Declines in BSA‑Related Requirements Do Not Impact Budget’s Bottom Line. Typically, drops in revenue would result in lower BSA and infrastructure requirements. Under our estimates, the state’s required payments on infrastructure decline by billions of dollars, but because of the way these payments are scored, these changes have no impact on the budget’s bottom line. In addition, BSA deposits increase largely because of the significant downward revenue adjustment to 2022‑23. The large downward revenue adjustment means the state must continue to make reserve deposits to reach the 10 percent threshold (under our understanding of the administration’s interpretation of Proposition 2) after 2022‑23.

Proposition 98

Proposition 98 Sets Minimum Level of School Funding. Proposition 98 (1988) amended the California Constitution to establish a minimum annual funding requirement for schools and community colleges. The state calculates the minimum requirement using formulas that account for various inputs, including General Fund revenue. The state meets the requirement through a combination of General Fund spending and local property tax revenue. The state recalculates the minimum requirement at the end of the year based on revised estimates of these inputs, followed by a second recalculation at the end of the following year. When the minimum requirement decreases, the state can leave school spending at the level it initially approved in the budget or reduce spending to the lower requirement.

Estimate of Minimum General Fund Spending Requirement Under Proposition 98 Is Down $21 Billion… Under our outlook, the decline in General Fund revenue reduces the minimum required General Fund spending under Proposition 98 by $21 billion from 2022‑23 through 2024‑25, which represents a reduction of nearly 38 cents for each dollar of lower revenue. This reduction includes $9.6 billion in 2022‑23, $7 billion in 2023‑24, and $4.4 billion in 2024‑25. The magnitude of the downward revision in 2022‑23 is unprecedented for a fiscal year that is already over. Although the state has experienced large swings in the minimum requirement for fiscal years that are currently in progress, revisions to prior fiscal years are typically minor and rarely exceed a few hundreds of millions of dollars.

… But Automatic Reduction in School Spending Is Only $4.3 Billion. Although the constitutional minimum funding requirement is down $21 billion, the automatic reduction in school spending over the period is only $4.3 billion. Most of this reduction relates to the automatic elimination of required deposits into the Proposition 98 Reserve in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24. After accounting for the effects of lower reserve deposits—along with several smaller adjustments—General Fund spending over the three years is down $4.3 billion compared with the June 2023 estimates. This reduction leaves school spending nearly $16.7 billion above the levels that would exist if the state only funded at the constitutional minimum each year of the period.

Multiyear

In this section, we describe our estimates of California’s budget condition for the multiyear period through 2027‑28. This projection is based on our main revenue forecast, as shown in Figure 2, and spending forecast, as shown in Appendix 2.

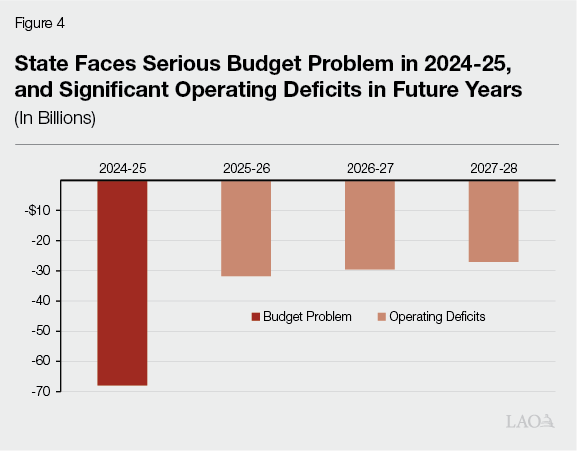

State Faces Significant Operating Deficits. Figure 4 shows our projections of the multiyear condition of the budget under our main revenue forecast. As the figure shows, in addition to the $68 billion budget problem we have identified for 2024‑25, the state faces annual operating deficits of around $30 billion per year. These operating deficits represent additional budget problems the Legislature would need to address in the coming years, either by reducing spending, increasing revenues, shifting costs, or using reserves. Although highly uncertain, our projection of the state’s deficits would accumulate to $155 billion across the forecast window, which is significantly more than the amount of reserves the state has available (about $24 billion).

Extent of Future Deficits Depends on Legislative Decisions This Year. The multiyear deficits shown in Figure 4 are subject to substantial uncertainty. First, revenue estimates can easily differ from our estimates by tens of billions of dollars in either direction. Second, these deficits are based on our assessment of the costs of the state’s programs under current law and policy. The state’s actual costs will be higher or lower depending on decisions made by the Legislature, including, for example, about how to fund schools and community colleges in 2022‑23.

Solving the Budget Problem

State Has Various Options to Address the Budget Problem. While addressing a deficit of $68 billion will be challenging, the Legislature has a number of options available to do so. In this section, we describe some of the key ones. (Some of the solutions here assume a budget emergency is declared.) These solutions include:

- Withdraw Reserves. Under our estimates, the state would have about $24 billion in reserves to help address the budget problem (assuming a budget emergency is declared).

- Reduce Proposition 98 Spending. Over the three‑year period, the state could reduce General Fund costs by $16.7 billion if it were to lower school spending to the constitutional minimum allowed under Proposition 98. One option for implementing some of this reduction would be to use the Proposition 98 Reserve to cover school‑related costs that exceed the Proposition 98 minimum requirement in 2022‑23.

- Reduce Other One‑Time Spending. We estimate the state has at least $8 billion in one‑time and temporary spending in 2024‑25 that could be pulled back to help address the budget problem. In addition, there are potentially billions of dollars more in spending from prior years that has been committed but not yet distributed, and therefore also could be reduced to help address the budget problem.

- Identify Other Solutions. Even after using most or all of these solutions, the Legislature still would need to find more solutions to address the remainder of the budget problem. Other options include additional cost shifts (such as more loans from special funds), revenue solutions, and ongoing spending reductions.

Withdraw Reserves

State Could Withdraw Up to $24 Billion in General Purpose Reserves. As shown in Figure 3, the state has $23 billion in the BSA under our estimates, plus about $1 billion in the Safety Net Reserve, to address the budget problem. The Safety Net Reserve is available to fund program costs in HHS programs, like Medi‑Cal, while the BSA can only be accessed in a budget emergency, as described below.

Budget Emergency Available Under Our Estimates. The Legislature can only suspend mandatory deposits or make withdrawals from either of its two constitutional reserves—the BSA and the Proposition 98 Reserve—if the Governor declares a budget emergency. The Governor may declare a budget emergency in two cases: (1) if estimated resources in the current or upcoming fiscal year are insufficient to keep spending at the level of the highest of the prior three budgets, adjusted for inflation and population (a “fiscal budget emergency”), or (2) in response to a natural or man‑made disaster. Under our forecast, a fiscal emergency would be available both in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. In the case of a fiscal budget emergency, the Legislature only can withdraw the lesser of: (1) the amount of the budget emergency, or (2) 50 percent of the BSA balance (in each year). As of this writing, the Governor has not called a fiscal budget emergency for 2023‑24 or 2024‑25.

Reduce Proposition 98 Spending

Spending Reductions Would Help Balance the Budget but Involve Trade‑Offs. If the Legislature reduced school spending to the constitutional minimum allowed by Proposition 98, it would address up to $16.7 billion of the budget problem. To obtain these savings, the state would have to reduce spending it previously approved in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24. In previous downturns, the state relied heavily on two main approaches for implementing such reductions: (1) across‑the‑board reductions to per‑pupil allocations and (2) payment deferrals. These options, however, tend to be disruptive for school operations, particularly when the state announces them on short notice. In addition, the state’s options for reductions in 2022‑23 are relatively limited because the state has allocated most of the funding attributable to the prior year already. Before resorting to cuts or deferrals, however, the state could reduce spending in other ways that would be less disruptive for schools.

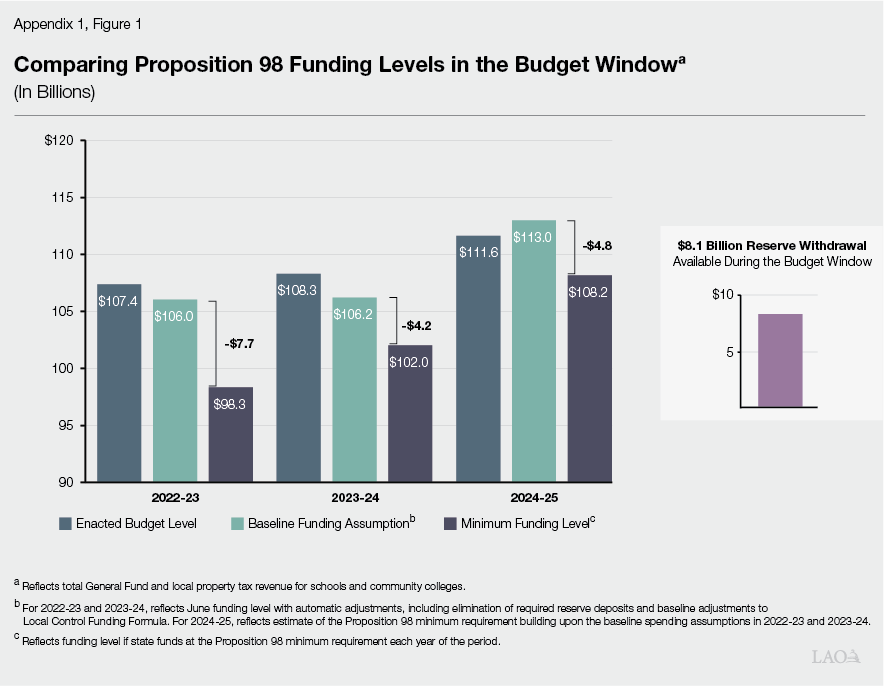

Proposition 98 Reserve Could Cover Spending Above the Minimum Requirement in 2022‑23. Based on deposits the state made in 2020‑21 and 2021‑22, the Proposition 98 Reserve currently holds a balance of $8.1 billion. (This amount excludes the additional deposits the state had anticipated making in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24 prior to our lower revenue estimates.) The state could use up to $7.7 billion of this balance to cover school spending that exceeds the Proposition 98 minimum requirement in 2022‑23. Using the Proposition 98 Reserve in this way would allow the state to lower General Fund spending to the constitutional minimum level in the prior year without reducing the funding allocations it previously approved. From an accounting perspective, Proposition 98 Reserve withdrawals also do not count as spending for the purpose of determining the minimum funding requirement in future years. This means using the Proposition 98 Reserve for 2022‑23 also would reduce the constitutional minimum requirements in 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. (The formulas governing the Proposition 98 Reserve would require the state to withdraw the remaining amount in the reserve—about $450 million—in 2023‑24.)

State Could Make Reductions to Programs With Unallocated Funds. Although the Proposition 98 Reserve could allow the state to reduce General Fund spending with minimal disruption to school programs, the reserve balance is not large enough to obtain $16.7 billion in savings by itself. If the state wanted to obtain the maximum possible savings, it would need to make additional reductions. One option is to reduce program funding that has not yet been allocated to schools. For example, the state previously approved $1.1 billion for grants to community schools that count as spending in 2022‑23 but have not yet been awarded. (This funding is in addition to the roughly $3 billion in funding for community schools that the state approved prior to 2022‑23.) In addition, several hundreds of millions of dollars in State Preschool funding provided in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24 is currently not obligated for any specific purpose. Over the coming months, the state likely will be able to identify additional grants and programs with unspent funds. Reducing grants that have not yet been allocated to schools could allow the state to reduce General Fund spending while minimizing reductions to funding that schools were already planning to receive. As we explain in the Appendix, if the Legislature took these actions, Proposition 98 funding would be sufficient to cover all but $1 billion of ongoing program costs in 2024‑25.

Reduce One‑Time Spending

Pulling Back One‑Time and Temporary Spending Could Provide More Than $10 Billion in Solutions. We estimate the state has $8.6 billion in one‑time and temporary spending slated for 2024‑25 that can be reduced entirely in order to address the serious budget problem. This includes spending of: $2.2 billion in transportation, $1.9 billion in natural resources and environment, and $1.8 billion in various education programs. In addition, the Legislature has committed tens of billions of dollars in previous years to one‑time and temporary purposes, including billions of dollars in the current year. Some of these funds could be withdrawn to address the deficit, but the Legislature would need to request more information from the administration to know the precise amounts that could be feasibly reduced. To maximize flexibility and mitigate disruption, some of these pullbacks could merit early action in 2024.

Identify Other Solutions

State Might Have Some Cost Shift Options Remaining. Cost shifts occur when the state moves costs between fund sources or entities—for example, shifting spending from the General Fund to special funds or, as has been done in prior budgets, shifting costs from the state to local governments. The state used about $10 billion in cost shifts to address last year’s budget problem and could have some additional capacity to shift additional costs again this year. For example, we think the state would have more capacity to make loans from special funds if those loans were made on a pooled basis, rather than on an individual fund basis.

State Has Used Revenue Increases to Address Past Budget Problems. For example, in 2020‑21, the state temporarily suspended net operating loss (NOL) deductions, preventing corporations with net income over $1 million from using NOLs. The state also limited businesses from claiming more than $5 million in tax credits. The state also has increased broad‑based taxes on a temporary and permanent basis in similar revenue downturns.

Other Spending Reductions. Given the extent of the deficit, the state might also have to reduce other spending—including cuts into its core service level—in order to balance the budget. In facing budget problems of similar magnitudes, the state in the past has made reductions to employee compensation and lowered spending on higher education and the judicial branch. The Legislature also could explore using more of the state’s recently reauthorized tax on managed care organization to offset the General Fund costs of Medi‑Cal, rather than for other costs, such as increasing provider rates.

Comments

Unprecedented Prior‑Year Revenue Revision Creates Unique Challenges. Typically, the budget process does not involve large changes in revenue in the prior year (in this case, 2022‑23). This is because usually prior‑year taxes already have been filed and associated revenues collected. Due to the federal tax filing extensions, however, the Legislature is gaining a complete picture of 2022‑23 tax collections after the fiscal year has already ended. This creates unique and difficult challenges. Had the Legislature had complete information about 2022‑23 tax collections in May, as would be typical, it would have solved much of this deficit in June 2023. At that time, the Legislature would have had more options available to reduce spending. Now that the fiscal year has ended, adjusting spending for 2022‑23 across a broad range of programs will be more challenging, including for schools and community colleges and much of the rest of the budget.

Early Action Could Increase Flexibility. Given the scale of the budget problem, we suggest the Legislature immediately begin evaluating past spending to find monies that have been committed but not yet distributed. These could be pulled back to help address the budget problem. Taking early action on these reductions could increase the choices available to the Legislature. Once more money has been distributed, fewer options will be available by May.

Legislature Will Have Fewer Options to Address Multiyear Deficits in the Coming Years. Given the state faces a serious budget problem, using general purpose reserves this year is merited. That said, we suggest the Legislature exercise some caution when deploying tools like reserves and cost shifts. The state’s reserves—which total $24 billion—are unlikely to be sufficient to cover the state’s multiyear deficits—which average $30 billion per year under our estimates. These deficits likely necessitate ongoing spending reductions, revenue increases, or both. As a result, preserving a substantial portion—potentially up to half—of reserves would provide a helpful cushion in light of the anticipated shortfalls that lie ahead.

Appendix 1: Outlook for School and Community College Funding

Total Proposition 98 Funding Requirement Down $18.8 Billion Compared With June Estimates. Under our outlook, the minimum funding requirement for schools across 2022‑23, 2023‑24, and 2024‑25 is $18.8 billion lower than the estimates from June 2023. This reduction reflects two main adjustments: (1) a $21 billion decrease in required General Fund spending and (2) a $2.2 billion increase in local property tax revenue. The reduction in required General Fund spending reflects our significantly lower estimates of General Fund revenue, with the minimum funding requirement decreasing nearly 38 cents for each dollar of lower revenue. The increase in local property tax revenue reflects preliminary data showing growth in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24. Appendix Figure 1 and Figure 2 provide more detail on these changes by year. As the bottom of Appendix Figure 2 shows, the total reduction in the minimum funding requirement is $9 billion in 2022‑23, $6.3 billion in 2023‑24, and $3.5 billion in 2024‑25. These amounts represent the maximum reductions in school funding—relative to June 2023 estimates—the state could make while still meeting the Proposition 98 minimum funding requirement.

Appendix 1, Figure 2

Comparing Proposition 98 Funding Estimates

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

Three‑Year Totals |

|

|

Proposition 98 Estimates |

||||

|

June 2023 Enacted Budget |

||||

|

Proposition 98 Funding: |

||||

|

General Fund |

$78,117 |

$77,457 |

$79,739 |

$235,314 |

|

Local property tax |

29,241 |

30,854 |

31,881 |

$91,977 |

|

Totals |

$107,359 |

$108,312 |

$111,621 |

$327,291 |

|

General Fund tax revenueª |

$204,533 |

$201,213 |

$203,116 |

$608,862 |

|

K‑12 average daily attendance |

0.1% |

0.3% |

‑0.2% |

— |

|

Per capita personal income |

7.6 |

4.4 |

3.1 |

— |

|

Per capital General Fundb |

‑6.2 |

‑0.8 |

1.4 |

— |

|

Operative test |

1 |

1 |

1 |

— |

|

LAO December Outlook With Baseline Adjustments Only |

||||

|

Proposition 98 Funding: |

||||

|

General Fund |

$76,244 |

$74,651 |

$80,111 |

$231,007 |

|

Local property tax |

29,778 |

31,543 |

32,867 |

94,189 |

|

Totals |

$106,022 |

$106,195 |

$112,979 |

$325,195 |

|

General Fund tax revenueª |

$179,091 |

$182,747 |

$190,099 |

$551,938 |

|

K‑12 average daily attendance |

0.9% |

0.7% |

0.7% |

— |

|

Per capita personal income |

7.6 |

4.4 |

4.3 |

— |

|

Per capital General Fundb |

‑17.8 |

2.9 |

5.3 |

— |

|

Operative test |

1 |

3 |

2 |

— |

|

LAO December Outlook With Funding Reduced to Minimum Level |

||||

|

Proposition 98 Funding: |

||||

|

General Fund |

$68,553 |

$70,491 |

$75,295 |

$214,338 |

|

Local property tax |

29,778 |

31,543 |

32,867 |

94,189 |

|

Totals |

$98,330 |

$102,035 |

$108,162 |

$308,527 |

|

General Fund tax revenueª |

$179,091 |

$182,747 |

$190,099 |

$551,938 |

|

K‑12 average daily attendance |

0.9% |

0.7% |

0.7% |

— |

|

Per capita personal income (Test 2) |

7.6 |

4.4 |

4.3 |

— |

|

Per capital General Fund (Test 3)b |

‑17.8 |

2.9 |

5.3 |

— |

|

Operative test |

1 |

1 |

2 |

— |

|

Funding Comparisons |

||||

|

Difference From Enacted Budget to LAO Baseline |

||||

|

General Fund |

‑$1,873 |

‑$2,806 |

$372 |

‑$4,307 |

|

Local property tax |

536 |

689 |

986 |

2,211 |

|

Totals |

‑$1,336 |

‑$2,117 |

$1,358 |

‑$2,096 |

|

Difference From LAO Baseline to Proposition 98 Minimum Level |

||||

|

General Fund |

‑$7,692 |

‑$4,160 |

‑$4,816 |

‑$16,668 |

|

Local property tax |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

‑$7,692 |

‑$4,160 |

‑$4,816 |

‑$16,668 |

|

Difference From Enacted Budget to Proposition 98 Minimum Level |

||||

|

General Fund |

‑$9,565 |

‑$6,966 |

‑$4,445 |

‑$20,975 |

|

Local property tax |

536 |

689 |

986 |

2,211 |

|

Totals |

‑$9,028 |

‑$6,277 |

‑$3,459 |

‑$18,764 |

|

aExcludes non‑tax revenues and transfers, which do not affect the Proposition 98 calculations. bAs set forth in the State Constitution, reflects change in per capita General Fund plus 0.5 percent. |

||||

Under Baseline Assumptions, State Would Provide $11.9 Billion More Than the Revised Minimum Requirement in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24. Although the Proposition 98 funding requirement changes automatically based on updated revenue estimates, the law does not automatically adjust most school spending in the current or prior year. For 2022‑23, we estimate that automatic adjustments only reduce Proposition 98 spending by $1.3 billion compared with the level anticipated in June 2023. This reduction mainly reflects the elimination of the required deposit into the Proposition 98 Reserve (the deposit is no longer required due to our lower estimates of capital gains revenue). It also reflects a small increase in costs for the Local Control Funding Formula and various smaller adjustments. Accounting for the $9 billion decrease in the Proposition 98 funding requirement and the $1.3 billion decrease in costs, overall spending in the prior year is $7.7 billion above the minimum requirement. This funding above the minimum level also becomes part of the base for calculating the minimum requirement in 2023‑24. Specifically, it increases the 2023‑24 requirement by $4.2 billion relative to the amount the state otherwise would have to provide. Across both years combined, funding under our baseline assumptions is $11.9 billion higher than the amount the state would provide if it were to fund at the minimum level only.

Decision About Spending in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24 Affects Calculation of the Funding Requirement in 2024‑25. The Legislature’s decision about whether to reduce funding to the lower minimum requirement in the current and prior year has significant implications for the calculation of the funding requirement in 2024‑25. We estimate that if the state leaves funding $11.9 billion above the Proposition 98 minimum requirement across 2022‑23 and 2023‑24 (consistent with our baseline assumptions), the funding requirement in 2024‑25 would be $113 billion. This level of funding would be slightly higher than the estimate the state made in June 2023. Conversely, if the state were to lower funding in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24 to the minimum levels allowed under Proposition 98, the funding requirement in 2024‑25 would be $108.2 billion. This level of funding would be about $3.5 billion less than the estimate the state made in June 2023. If the state were to lower spending somewhat but not to the minimum levels in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24, the funding requirement in 2024‑25 would fall somewhere between $108.2 billion and $113 billion.

Total Costs for Existing Programs and Statutory Cost‑of‑Living Adjustment (COLA) Estimated at $109.3 Billion. Separate from our calculations of the Proposition 98 funding requirement, we also estimated the cost of maintaining existing school and community college programs in 2024‑25. In making this estimate, we accounted for cost increases and decreases related to (1) changes in student attendance and community college enrollment, (2) an estimated statutory COLA of 1.27 percent, and (3) the expiration of various one‑time costs and savings included in the June 2023 budget plan. Under our estimates, the total cost for existing programs in 2024‑25 is $109.3 billion. Of this amount, $1.3 billion is the cost specifically associated with the 1.27 percent statutory COLA. Under our baseline assumption (in which the state does not reduce funding to the minimum level in the current or prior year), the Proposition 98 funding requirement in 2024‑25 would be more than enough to cover the statutory COLA. If the state were to reduce spending to the minimum level, however, the 2024‑25 funding requirement would be about $1 billion less than the cost of existing programs adjusted for COLA.

State Estimated to Withdraw Entire Proposition 98 Reserve Balance. Under our outlook, the reductions in Proposition 98 funding require the state to withdraw the entire $8.1 billion balance in the Proposition 98 Reserve. Under our baseline assumption—that is, absent any special action by the Legislature—the constitutional formulas would require withdrawals of nearly $5.5 billion in 2023‑24 and nearly $2.7 billion in 2024‑25. Alternatively, the state could decide to withdraw funds preemptively and use them to cover costs that exceed the Proposition 98 requirement in the prior year. Under this approach, the state would withdraw $7.7 billion from the reserve for use in 2022‑23 (it would be required to withdraw the remaining $450 million in 2023‑24). This approach would allow the state to reduce General Fund spending on schools in the prior year without cutting school programs below previously approved levels. (This approach also assumes a budget emergency is declared.) Under the Constitution, the Legislature may use withdrawals from the Proposition 98 Reserve for any school or community college purpose.

Appendix 2

Appendix 2, Figure 1

General Fund Spending Through 2024‑25

(In Billions)

|

2023‑24 |

Outlook |

||

|

2024‑25 |

Change From 2022‑23 |

||

|

Legislative, Executive |

$6.1 |

$5.2 |

‑15% |

|

Courts |

3.5 |

3.7 |

6 |

|

Business, Consumer Services, and Housing |

2.6 |

0.5 |

‑79 |

|

Transportation |

0.9 |

0.1 |

‑94 |

|

Natural Resources |

5.7 |

4.6 |

‑20 |

|

Environmental Protection |

0.6 |

0.4 |

‑33 |

|

Health and Human Services |

73.4 |

75.4 |

3 |

|

Corrections and Rehabilitation |

14.2 |

13.5 |

‑4 |

|

Education |

21.2 |

21.4 |

1 |

|

Labor and Workforce Development |

0.9 |

1.2 |

43 |

|

Government Operations |

4.0 |

2.3 |

‑42 |

|

General Government |

|||

|

Non‑Agency Departments |

1.8 |

1.7 |

‑3 |

|

Tax Relief/Local Government |

0.6 |

0.6 |

6 |

|

Statewide Expenditures |

4.8 |

5.7 |

18 |

|

Capital Outlay |

0.5 |

0.3 |

‑37 |

|

Debt Service |

5.8 |

5.9 |

2 |

|

Non‑98 Spending Totals |

$146.4 |

$142.7 |

‑3% |

|

Proposition 98a |

$75.6 |

$80.1 |

6% |

|

Totals |

222.0 |

222.8 |

0% |

|

aReflects General Fund component of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. |

|||

Appendix 2, Figure 2

General Fund Spending by Agency Through 2027‑28

(In Billions)

|

Agency |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

2027‑28 |

Average |

|

Legislative, Executive |

$14.1 |

$6.1 |

$5.2 |

$3.1 |

$2.5 |

$2.5 |

‑22.0% |

|

Courts |

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.7 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

4.1 |

3.5 |

|

Business, Consumer Services, and Housing |

3.9 |

2.6 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

‑28.8 |

|

Transportation |

1.5 |

0.9 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

‑17.7 |

|

Natural Resources |

13.7 |

5.7 |

4.6 |

4.9 |

3.5 |

3.3 |

‑10.9 |

|

Environmental Protection |

3.9 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

‑28.0 |

|

Health and Human Services |

61.2 |

73.4 |

75.4 |

79.4 |

84.3 |

89.9 |

6.0 |

|

Corrections and Rehabilitation |

14.8 |

14.2 |

13.5 |

13.1 |

13.1 |

13.0 |

‑1.2 |

|

Education |

20.0 |

21.2 |

21.4 |

20.3 |

21.3 |

22.2 |

1.2 |

|

Labor and Workforce Development |

1.3 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

‑5.5 |

|

Government Operations |

5.5 |

4.0 |

2.3 |

3.4 |

7.0 |

8.1 |

52.0 |

|

General Government |

|||||||

|

Non‑Agency Departments |

2.3 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

‑13.9 |

|

Tax Relief/Local Government |

0.7 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

3.9 |

|

Statewide Expenditures |

1.3 |

4.8 |

5.7 |

6.9 |

8.2 |

9.1 |

16.9 |

|

Capital Outlay |

3.3 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.0 |

‑48.3 |

|

Debt Service |

5.2 |

5.8 |

5.9 |

5.9 |

5.9 |

6.0 |

0.6 |

|

Non‑98 Spending Totals |

$156.1 |

$146.4 |

$142.7 |

$145.1 |

$152.9 |

$161.5 |

4.2% |

|

Proposition 98a |

$76.2 |

$75.6 |

$80.1 |

$84.5 |

$87.3 |

$89.7 |

3.8% |

|

Proposition 2 Infrastructureb |

$0.0 |

$0.2 |

$0.7 |

$1.7 |

$4.8 |

$5.4 |

95.7% |

|

Total Forecasted Spending |

232.4 |

222.0 |

222.8 |

229.6 |

240.3 |

251.2 |

4.1% |

|

aReflects General Fund component of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. bIn 2022‑23 and 2023‑24, amounts are distributed across agencies. In 2024‑25 and after, Proposition 2 infrastructure requirements are assumed to offset existing costs, for example for bond debt service, and so do not result in higher total state costs. |

|||||||