LAO Contact

January 4, 2024

Assessing Early Implementation of Urban Water Use Efficiency Requirements

Executive Summary

Legislation approved in 2018 established a long‑term urban water use efficiency framework to “Make Conservation a California Way of Life.” This framework—which is one component of the state’s overall water management strategy—creates new requirements for about 405 urban retail water suppliers that supply water to nearly 95 percent of state residents. This report responds to a requirement contained in the 2018 legislation for our office to assess implementation of the framework. (Our report is not able to address every aspect requested in the legislation due to framework implementation delays.)

Establishes New Requirements for Urban Retail Water Suppliers. Under the new framework, each supplier’s actual water use for the previous year will be evaluated against a “water use objective” (WUO), which represents the amount of water its customers would have needed that year if water were being used efficiently. Beginning in 2027, the state can assess penalties against suppliers whose actual water use exceeds their WUOs. A supplier’s unique WUO is the sum of several factors: calculated standards for residential indoor and outdoor water use, commercial outdoor water use, and a certain amount of water that is lost due to system leaks. It also allows suppliers to use additional water for certain unique purposes and encourages water reuse. Additionally, the framework requires suppliers to implement a variety of performance measures for its commercial customers and report on that progress annually.

Tasks State Agencies With Implementation and Oversight Responsibilities. The 2018 legislation requires the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) to adopt regulations to implement the framework, informed by studies and recommendations by the Department of Water Resources (DWR). The board released proposed regulations in August 2023 and expects to adopt final regulations in the summer of 2024 (regulations would then take effect October 1, 2024). Based on the board’s proposed rules and published data, suppliers collectively will have to reduce statewide water use by 14 percent to achieve the aggregate 2035 WUOs, with certain suppliers facing much higher reductions—particularly many that are located in the inland regions of the state. These cutbacks will be on top of significant urban water use reductions achieved over the past two decades.

SWRCB’s Proposed Regulations Create Implementation Challenges and Go Beyond What Legislation Requires or DWR Recommends. We find that SWRCB’s proposed regulations will create challenges for water suppliers in several key ways, in many cases without compelling justifications. Specifically, the proposed regulations:

- Add Complexity. The performance measures suppliers must implement for commercial customers are unnecessarily complex, lack clarity in places, and will be administratively burdensome to implement. Outdoor water use by these customers represents only a small fraction (less than 3 percent) of the state’s total water use. Any savings achieved would be small and come at a large cost to suppliers.

- Could Be Difficult to Achieve. Although suppliers only have to achieve an aggregate WUO—and not each of the individual standards for indoor and outdoor use—SWRCB proposes such stringent standards for outdoor use that suppliers will not have much “wiggle room” in complying. That is, suppliers may necessarily have to achieve each individual standard if they hope to achieve their overall WUOs.

- Add Significant Costs. The new framework is estimated to result in cumulative costs in the low tens of billions of dollars from 2025 through 2040. These costs will be borne primarily by suppliers, wastewater agencies, and customers. Particularly in the near term, suppliers’ costs will increase as they attempt to implement the new requirements, such as from providing incentives for residents to make behavioral changes like converting their lawns to more drought tolerant landscapes. Whether the benefits of the new rules ultimately will outweigh the costs is unclear. While an assessment from SWRCB estimates a cumulative net benefit of $2.5 billion, an independent review conducted by a private consulting firm—which raises credible questions about SWRCB’s estimates—projects net costs of $7.4 billion. Moreover, even if benefits outweigh costs in the long run, whether they merit the amount of work and costs to implement the requirements as currently proposed is uncertain.

- Could Disproportionately Affect Lower‑Income Customers. To cover added costs and offset potential revenue reductions from selling less water, suppliers likely will have to increase customer rates. This could adversely impact lower‑income customers, who may have more trouble affording the increases and may have less ability to further reduce water use to compensate. Existing constitutional rules make it difficult for suppliers to offer rate assistance programs.

- Build in Aggressive Time Lines. Although the requirements are phased in over multiple years, the time line for full implementation may be too aggressive given the number of changes that will have to occur to achieve the level of conservation envisioned. In addition, although SWRCB is two years behind adopting final rules, suppliers’ deadlines (which are set in statute) have not been correspondingly adjusted.

Even Modest Water Savings Could Help With Resilience, but Will Depend on How the State Manages Those Savings. SWRCB estimates the state could conserve about 440,000 acre‑feet of water annually at full implementation, which represents about 1 percent of total state water use. Although this amount of water conservation is modest, it could increase the state’s overall drought resilience if it helps align demand with lower water supplies in dry years. In wet years, the water potentially could be stored for use during drought periods. However, the 2018 legislation did not address how to track and manage these potential water savings. Doing so will be key to maximizing the benefits of these conservation efforts. Urban water savings during wet years will only help local suppliers and/or the state better manage and meet California’s water needs during periods of drought if they are targeted effectively.

Recommendations for Legislative Consideration. To ease suppliers’ administrative burden and potentially reduce costs, we recommend the Legislature use its oversight authority to make several changes to the framework in the near term as well as at key milestones over the coming years. In early 2024, the Legislature could direct SWRCB to simplify several aspects of the framework, such as requirements concerning suppliers’ commercial customers. We also suggest that the Legislature require DWR to provide more technical assistance to suppliers, direct SWRCB to make several of the proposed requirements less stringent (such as the residential outdoor standard), consider how to target state funding to assist lower‑income customers, and extend some of the deadlines for suppliers to ensure they can actually achieve the framework’s goals. Finally, to increase the state’s resilience during droughts, we recommend the Legislature develop a strategy to manage and take advantage of any water saved due to these regulations. This is a fundamental step in ensuring that water conserved during wet years is effectively helping to meet the state’s ultimate goals.

Introduction

Two Laws Approved in 2018 Require Long‑Term Water Use Efficiency. Chapters 14 (SB 606, Hertzberg) and 15 (AB 1668, Friedman) of 2018 established a framework to guide the creation and implementation of new long‑term urban water use efficiency requirements. They require urban water suppliers to develop and achieve objectives for efficient water use based on local conditions and population. (While these laws primarily concern urban water use, to a lesser degree they also address agricultural water use efficiency, require drought contingency planning, and seek improvements for small rural communities.)

This Report Responds to a Statutory Requirement. Senate Bill 606 required our office to assess implementation of urban water use efficiency standards and urban water supplier reporting by submitting a report by January 10, 2024 to the appropriate policy committees of both houses of the Legislature and to the public. Figure 1 displays the specific statutory reporting requirements.

Figure 1

Legislative Analyst Directed to Evaluate Implementation of Water Conservation Laws

LAO Statutory Reporting Requirements Contained in Chapter 14 of 2018 (SB 606, Hertzberg)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Implementation Delays Limit the Scope of Our Report. The time line for implementation of the urban water use efficiency framework has been delayed somewhat—in part due to the COVID‑19 pandemic—and final regulations now are not scheduled to take effect until October 1, 2024. Consequently, we are unable to conduct the data analysis called for by SB 606 or to comment on the rate of compliance among urban water suppliers or the frequency of use of the bonus incentive since regular reporting will not begin in earnest until 2025. However, we are able to provide an early assessment of the proposed regulations and potential implementation challenges.

Overview of Report. This report has three major sections. In the “Background” section, we describe urban water suppliers, how water use efficiency fits into the state’s approach to water supply management, and the 2018 laws that created the urban water use efficiency framework. In the “Assessment” section, we discuss potential impacts to various urban water suppliers, the regulations proposed by the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB), challenges urban water suppliers face in complying with the proposed regulations, and impacts on lower‑income communities. We also consider potential water savings that could result from the implementation of this framework. In the “Recommendations” section, we suggest some changes the Legislature could make through its oversight authority to ease administrative burdens and potentially reduce costs for suppliers. We also recommend the Legislature plan for how any water savings that result from these new requirements could be tracked and used.

Background

Urban Water Suppliers Serve Residents and Businesses

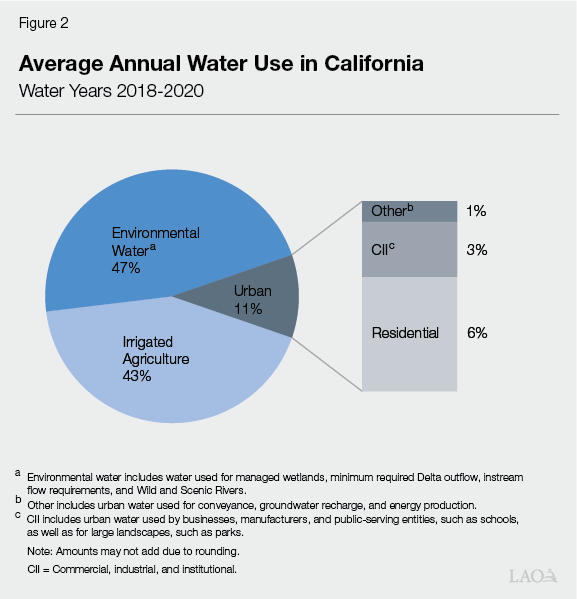

Urban Water Use Represents About 10 Percent of Overall State Water Use. As shown in Figure 2, urban water use typically accounts for around 10 percent of the state’s annual water use. By comparison, around 40 percent is typically used for agricultural irrigation and about 50 percent for environmental water. (Environmental water includes water used for managed wetlands, minimum required Delta outflow, instream flow requirements, and Wild and Scenic Rivers.) As the figure also shows, the majority of urban water consists of residential use (which makes up about 6 percent of total state water use), with less going toward commercial, industrial, and institutional (CII) purposes (about 3 percent of total state use) and for conveyance, groundwater recharge, and energy production (about 1 percent of total state use). (CII includes water used by businesses, manufacturers, and public‑serving entities, such as schools, as well as for large landscapes, such as parks.)

Urban Water Suppliers Provide Water to Most Californians. More than 400 urban water suppliers provide potable (drinkable) water to most of the state’s population. Statute defines an urban water supplier as one that provides water for municipal purposes and has at least 3,000 service connections or provides at least 3,000 acre‑feet of water annually. (An acre‑foot is the amount of water that would cover one acre of land to a depth of one foot.) These include retail water suppliers (that provide water directly to customers) and wholesale water suppliers (that sell water to retail suppliers). Some wholesale suppliers are also retail providers. Many urban water suppliers are public entities—such as cities, counties, or special districts—while some are private investor‑owned utilities. Public water suppliers serve about eight in ten Californians.

Suppliers Serve Residential and CII Customers. Urban water suppliers provide water for indoor and outdoor purposes for residents, as well as for CII customers. Some suppliers may work with customers to encourage the use of dedicated irrigation meters to track and manage the amount of water used for outdoor irrigation of lawns and landscapes, but most residents and many businesses use meters that capture indoor and outdoor water use together (“mixed‑use” meters).

Suppliers Rely Primarily on Rate‑Paying Customers to Support Operations. Ratepaying customers provide the primary source of revenue that urban water suppliers use to support their operations. The California Constitution and state statute govern how public water suppliers set rates, while the California Public Utilities Commission governs rates set by investor‑owned utilities. In both cases, the state places limits on how much suppliers can charge customers. For example, in the case of public water suppliers, voter‑approved Proposition 218 (1996) amended the State Constitution such that rates cannot be higher than the cost of providing service and must be in proportion to the amount of service provided to an individual customer. Although suppliers might use rate structures to manage demand (as discussed below), they can do so only within these limitations. Some suppliers have other sources of revenue. For example, suppliers with land holdings might lease property to other businesses, such as ranching operations or cell phone companies for placement of cell towers. When suppliers need to make a capital improvement, such as repairing an aqueduct or increasing storage, they might increase rates and/or use debt financing.

Suppliers Use a Variety of Approaches to Manage Demand. Urban water suppliers employ various strategies to meet and manage customers’ water use needs, including strategies to reduce demand, especially during times of drought. These include:

- Using Different Rate Structures or Raising Rates. While some suppliers might charge a flat rate (a single charge that does not vary based on the amount of water used), others use their rate structures to help manage demand. A simple example is a uniform rate for each unit of water used. A more complex rate structure, often called a tiered rate structure, can be designed to discourage overuse (so long as it adheres to Proposition 218 requirements). For example, the rate per unit of water used might increase after a certain total volume of water is exceeded. During droughts, suppliers might increase rates or assess a surcharge for excessive water use.

- Offering Rebate and Incentive Programs. Many water suppliers offer rebates for participating in conservation programs. For example, to reduce indoor water use they might offer rebates for replacing older model toilets, showerheads, or other fixtures and appliances with more efficient models. To reduce outdoor water use, they might offer rebates for converting lawns to more water‑efficient landscapes. To access rebates, customers typically pay for the cost of the project themselves and apply for some amount of reimbursement after the project is completed. Rebates typically do not cover installation costs. In some more limited cases, a supplier might provide a “direct installation” program where it pays the up‑front costs (instead of reimbursing the customer later) and manages and pays for installation. Rebates are typically limited in amount (for example, lawn conversion rebates usually do not cover the full project cost) and could be limited in number (such as if the supplier has a set total amount they can spend on rebates each year).

- Conducting Outreach and Education to Encourage Efficiency. Many suppliers (and the state) run campaigns, such as through television and radio ads, mailers, and social media posts, to encourage conservation and efficient use of water. They also might hold community events or conduct educational workshops, for example, to teach people how to convert lawns to drought‑resilient landscapes or access rebates.

- Implementing Restrictions. Particularly during droughts, water suppliers might seek to limit their customers’ water use through any number of different strategies, which could be stricter than state requirements. For example, they might limit the times of day or number of days per week that residents can water their lawns or require that leaks be fixed within a certain time frame. Some suppliers might issue fines if a customer uses too much water.

- Increasing Supplies. Suppliers might consider ways to increase supplies through banking groundwater, expanding surface storage, building desalination facilities, or importing additional water. (Due to the significant associated cost and/or geographical or practical limitations, expanding surface storage and increasing ocean desalination are options only for certain suppliers.)

- Increasing Water Recycling. Another key method for managing demand is through water recycling to increase the amount of available potable or non‑potable reuse water. (Recycled non‑potable water can be used for irrigation and other non‑drinking uses.)

Urban Water Conservation Is One Component of the State’s Water Management Strategy

Climate Change and Groundwater Management Requirements Have Increased Need to Manage Water Resources Effectively. Exacerbated by climate change, droughts are expected to become more frequent, prolonged, and severe in California. The state spent about 9 of the previous 11 years in drought (2012‑2016 and 2019‑2022). During the most recent drought, California experienced the driest three winter months on record (January through March 2022). In 2022, the Department of Water Resources (DWR) received reports of approximately 1,400 household wells having gone dry, up from about 970 in 2021 and from an average of about 80 in each of the previous four years. Rising temperatures due to climate change also mean that less of the state’s water will be stored in snowpack (which historically has been available as additional water supply in dry summer and fall months). Additionally, the state’s regulation of groundwater, authorized by the 2014 passage of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), will limit the amount of groundwater pumping allowed and require that more water be used for groundwater recharge. This combination of factors requires that Californians maximize efficient use and effective management of available water resources.

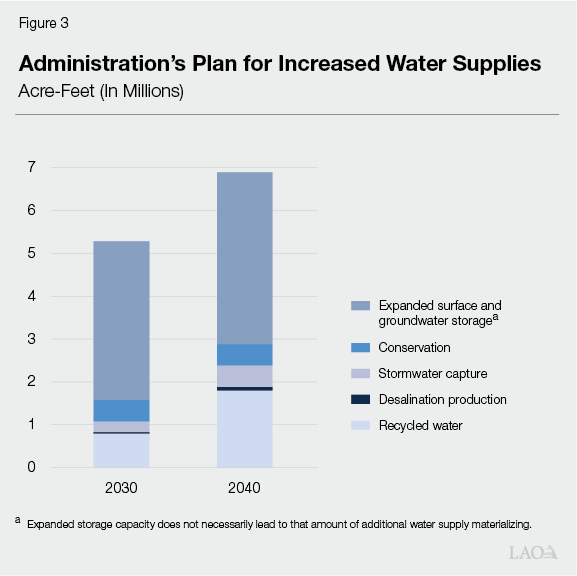

State’s Multifaceted Water and Drought Resilience Policies Emphasize Urban Water Conservation. To deal with the factors noted above, the state’s intended approach for decreasing water demand and boosting supply includes increasing water recycling, desalination, stormwater capture, and conservation, as well as expanding above‑ and below‑ground storage. In August 2022, the Newsom administration released California’s Water Supply Strategy; Adapting to a Hotter, Drier Future, which includes estimates—as shown in Figure 3—for the amount of additional water that could be conserved, recycled, produced, captured, and stored by 2030 (about 5 million acre‑feet) and 2040 (about 7 million acre‑feet).

State Has Implemented Numerous Policy Changes to Increase Water Conservation. As shown in Figure 4, over the past 15 or so years, the state has implemented a number of policies to support and increase water conservation through executive action, legislation, and regulations. Among the more significant changes in the urban water context was the Water Conservation Act of 2009, which mandated a 20 percent reduction in per capita urban water use by 2020 (“20x2020”). (The state achieved this goal by 2014.) In addition, the Legislature enacted laws to limit the amount of water lost through system leaks, establish the long‑term efficiency framework that is the subject of this report, and ban using potable water for nonfunctional turf on CII landscapes. (Nonfunctional turf is grass that is not used for specific functions such as recreation.) While SGMA did not identify urban water conservation as one of its primary goals, it still will have significant impacts in some nonagricultural regions. Specifically, urban water suppliers that rely on groundwater will be affected if their groundwater pumping is reduced in the coming years.

Figure 4

Select State Policies That Seek to Increase Water Conservation

|

2009 |

Chapter 4 (SB X7‑7, Steinberg) |

Known as the Water Conservation Act of 2009, required development of urban water use targets to achieve a 20 percent reduction in water use per capita by 2020 (“20x2020”). |

|

2014‑2015 |

Proclamations (1/17/14 and 4/25/14) Executive Orders B‑26‑2014, B‑28‑2014, B‑29‑2015, and B‑36‑2015 |

Proclaimed a drought state of emergency. Authorized various emergency activities, including mandating a 25 percent reduction in potable urban water use through February 2016, relative to 2013 levels. SWRCB issued emergency regulations in May 2015 to effectuate this rule. |

|

2014 |

California Water Action Plan |

Five‑year plan laying out ten priority actions to increase the reliability and resilience of the state’s water supply and restore important species and habitat. Called for increasing efficiency beyond what SB X7‑7 envisioned. The plan was updated in 2016 and a final implementation report was released by CNRA in 2019. |

|

2014 |

Sustainable Groundwater Management Act: Chapter 346 (SB 1168, Pavley) Chapter 347 (AB 1739, Dickinson) Chapter 348 (SB 1319, Pavley) |

Requires monitoring and operating groundwater basins to avoid overdraft with the goal of achieving long‑term groundwater resource sustainability beginning in 2040. |

|

2015 |

Chapter 679 (SB 555, Wolk) |

Requires urban retail water suppliers to submit water loss audit reports and limit water losses by meeting volumetric standards. SWRCB approved regulations in November 2022 that require suppliers to meet the standards starting in 2028, with subsequent assessments every three years. |

|

2016 |

Executive Order B‑37‑16 (May 16) |

Established goal of “Making Conservation a California Way of Life.” Directed the administration to develop water use targets as part of a permanent long‑term conservation framework. |

|

2018 |

Chapter 14 (SB 606, Hertzberg) Chapter 15 (AB 1668, Friedman) |

Codified conservation framework and established urban water use objectives and reporting requirements. |

|

2019 |

Chapter 239 (AB 1414, Friedman) |

Amended the timing for suppliers’ annual water use efficiency reporting and required suppliers to describe their demand management strategies in their 2024 reports. |

|

2021‑2023 |

Proclamations (4/21/21, 5/10/21, 7/8/21, and 10/19/21) Executive Orders (N‑10‑21, N‑7‑22, N‑3‑23, N‑4‑23, and N‑5‑23) |

Proclaimed a drought state of emergency, ultimately expanding across the entire state. Among several emergency activities, instituted conservation requirements for water suppliers under their drought contingency plans. Called on residents to voluntarily reduce water use by 15 percent (relative to 2020 levels) in summer 2021. |

|

2022 |

Chapter 679 (SB 1157, Hertzberg) |

Made amendments to AB 1668, including tightening indoor residential water use standards used in water use objectives. |

|

2023 |

Chapter 849 (AB 1572, Friedman) |

Prohibits use of potable water to irrigate nonfunctional turf on CII landscapes, phasing in the prohibition from 2027 to 2031. |

|

SWRCB = State Water Resources Control Board; CNRA = California Natural Resources Agency; and CII = commercial, industrial, and institutional. |

||

State Also Has Approved Funding for a Variety of Conservation Activities. Along with policy changes to increase water use efficiency and conservation, the Legislature, Governor, and voters have approved approximately $1 billion in state funding over the past decade to support these goals, as shown in Figure 5. This includes about $100 million from Proposition 1 (2014 water bond) for various water conservation projects and activities. The state also provided significant General Fund resources, including $275 million for urban drought and water conservation programs, $75 million for turf replacement, $75 million for the state’s Save Our Water campaign, and nearly $450 million in grant funding for water recycling projects. Additionally, the state has provided General Fund to support DWR and SWRCB in implementing the water conservation framework enacted by SB 606 and AB 1668.

Figure 5

Select State Funding for Water Conservation Activities

General Fund, Unless Otherwise Noted

|

Year |

Activity |

|

2015 |

|

|

2019 |

|

|

2021 |

|

|

2022 |

|

|

2023 |

|

|

aFunding from Proposition 1 (2014). |

|

|

bOf total, $7 million from Proposition 1. |

|

|

DWR = Department of Water Resources and SWRCB = State Water Resources Control Board. |

|

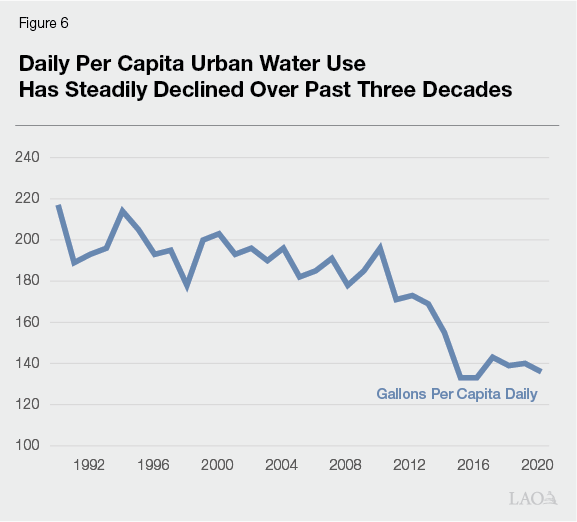

State and Local Actions Have Led to Water Use Reductions. As shown in Figure 6, between 1990 and 2020, daily per capita water use in California declined by 37 percent, from 217 gallons to 136 gallons. (In this context, water use measured in “gallons per capita daily” includes most urban water use. Later we discuss a new standard which uses the same terminology but which is calculated based only on indoor residential water use.) Much of this reduction occurred after the 20x2020 requirement was established (a goal the state has far exceeded). Because of the decline in per capita water use, the total amount of urban water used statewide has plateaued despite an increase in the state’s population. The state uses roughly the same total amount of urban water now as it did in 1990.

2018 Laws Created New Urban Water Use Efficiency Framework

Senate Bill 606 and AB 1668—the subjects of this report—created the statutory framework for “Making Conservation a California Way of Life.” The Governor initiated this effort in 2016 via an executive order, which required DWR and SWRCB to develop water use targets as part of a permanent water use efficiency framework. DWR and SWRCB—along with several other departments—issued a report in 2017 about implementing the framework, which then led to its codification in 2018. SWRCB will adopt final regulations next year to implement the framework’s requirements. Two subsequent bills were approved that either amended certain aspects of the original laws or added to them. These are Chapters 239 of 2019 (AB 1414, Friedman) and 679 of 2022 (SB 1157, Hertzberg).

The section below provides an overview of the legislation (including updates made by AB 1414 and SB 1157) as well as details about the new requirements that urban retail water suppliers will face over the coming years.

Overview of Legislation

Requires Suppliers to Increase Water Use Efficiency. Senate Bill 606 and AB 1668 require urban retail water suppliers to develop a water use objective (WUO) based on the local characteristics of their service areas. (We discuss in more detail below how the WUO is calculated and various other aspects of the legislation’s requirements.) The WUO represents the total amount of water a supplier would have delivered to customers in the previous year if water had been used efficiently (based on the four efficiency inputs described below). It is akin to a water budget. The supplier’s reported actual water use for the previous year will be assessed against its WUO and ultimately SWRCB can issue penalties against suppliers that do not achieve their objectives. The legislation also requires suppliers to implement performance measures for water use on CII landscapes. Finally, it requires each supplier subject to the requirements to report a variety of information to DWR annually, including its WUO for the previous year, its actual water use, progress made toward achieving the WUO, and implementation of CII performance measures. Figure 7 describes the major components of the legislation.

Figure 7

Major Components of 2018 Water Use Efficiency Legislation

|

Develop and Achieve Water Use Objectives (WUOs) |

On an annual basis beginning in 2024, suppliers must (1) calculate their WUOs for the previous year, (2) report actual water use for the previous year, and (3) achieve their WUOs (with penalties for noncompliance beginning in 2027). The WUO is based on four efficiency inputs: |

|

|

|

Implement CII Performance Measures |

Phased in over the 2025 through 2030 period, suppliers must begin to: |

|

|

|

Report Annually |

Suppliers must report their WUOs and actual water use annually. Annual reporting must also include descriptions of progress made toward implementing CII performance measures. |

|

CII = commercial, industrial, and institutional. |

|

Applies to Urban Retail Water Suppliers. The legislation concerns the state’s approximately 405 urban retail water suppliers (those with at least 3,000 connections or that provide at least 3,000 acre‑feet of water annually). This includes about 15 wholesale providers that are also retail suppliers. These suppliers serve about 95 percent of the state’s population.

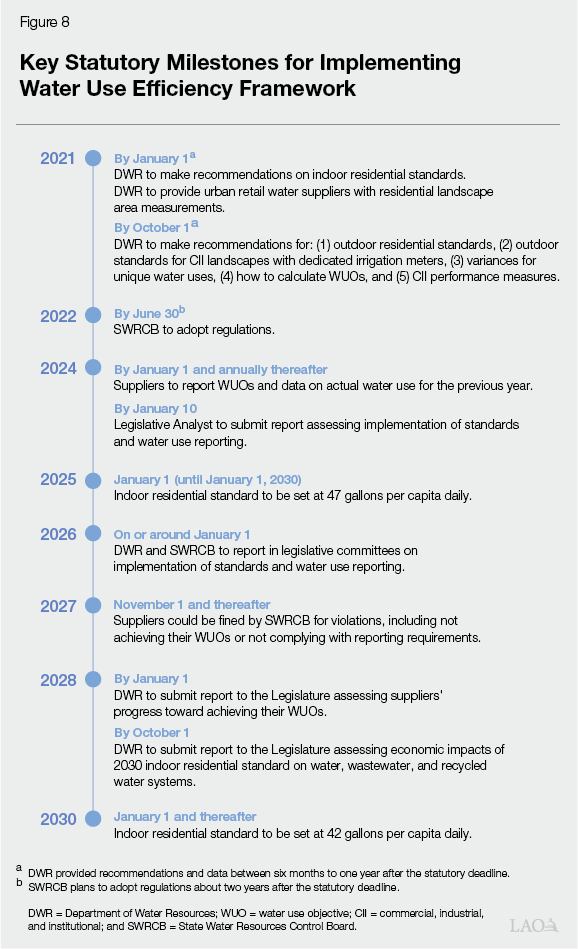

Phases in Requirements and Standards Over Multiple Years… The legislation created a multiyear phase‑in period, as shown in Figure 8. In the initial years it required DWR, in collaboration with SWRCB, to conduct the necessary studies to make recommendations for developing the standards (such as for outdoor residential water use) and other inputs that comprise the WUO calculation. DWR also was required to collect and provide data to suppliers about residential landscape area measurements so they would know how much land in their service area is “irrigable.” The first statutory reporting deadline for suppliers was January 1, 2024. By that date, they had to report their WUO for the prior year along with actual water use.

…Although Delayed Regulations Are Resulting in Interim Reporting for 2024. The departments were unable to meet several of the initial statutory deadlines noted in Figure 8, in part due to the COVID‑19 pandemic. For example, DWR was about seven months behind in making recommendations for indoor residential water use standards and about a year behind in making recommendations for other inputs to the WUO calculation. It also was delayed by about a year in providing data to suppliers about residential landscape area measurements. Given that SWRCB’s process relied on DWR recommendations, the board’s development of regulations—which will lay out the specific requirements that suppliers must follow—consequently was delayed as well. The legislation called for adoption of final regulations by June 30, 2022, yet SWRCB expects this will not occur until summer of 2024, with regulations taking effect October 1, 2024. (The board released proposed regulations in August 2023 and has one year to adopt them.) Despite these delays, none of the other implementation milestones or deadlines for suppliers have been changed. This created a unique circumstance for suppliers—they faced a statutory reporting deadline of January 1, 2024, but did not have final requirements to follow in compiling these reports. Because of this, DWR developed an interim reporting template that suppliers could use in 2024 to meet the reporting requirement. Following adoption of final regulations, the process will be more refined. Authorizes Civil Penalties to Be Assessed Beginning in 2027. As the regulatory agency, SWRCB is responsible for enforcing the new requirements. The enforcement process ramps up over several years. SWRCB may issue informational orders beginning in January 2024 (to gather more information about why a supplier is not meeting its WUO), written notices beginning in January 2025 (to warn the supplier it is not meeting its WUO and request that it address particular areas of concern in its next report), and conservation orders beginning in January 2026 (to require that the supplier undertake certain actions to improve efficiency). Ultimately, SWRCB may issue monetary penalties ($1,000 per day under regular conditions or $10,000 per day during specified drought years) for violations that occur after November 1, 2027.

Creates Responsibilities for Both DWR and SWRCB. As noted, the legislation required DWR and SWRCB to conduct specific activities to implement the water use efficiency framework. Recent budgets have provided each with funding for staffing and external contracts to support these activities. Of note is the standardized regulatory impact assessment that SWRCB completed. This assessment—essentially a benefit‑cost analysis—is required when the economic impact of a proposed regulation on California businesses and individuals is likely to exceed $50 million in any 12‑month period following adoption of regulations. In addition to the activities required by statute, DWR and SWRCB also have conducted other activities to facilitate implementation. For example, SWRCB has developed a Water Use Objective Exploration Tool, which helps to estimate WUOs statewide and for individual suppliers. Both DWR and SWRCB have created various other online resources, such as fact sheets and training videos. In addition, DWR is in the process of collecting CII landscape area measurement data and will offer technical assistance to suppliers on a pilot basis on how to use that information.

Includes Legislative Controls and Oversight of Framework and Implementation. The legislation included some specific ways for the Legislature to shape and conduct oversight of the water use efficiency framework. As shown in Figure 9, it stipulated certain components of the framework in statute, including setting standards for indoor residential water use, maintaining previously approved standards for water losses, and requiring new legislation for any revisions to standards initially set by the administration. The legislation also includes reporting by the administration at several points, including progress updates and a report on the economic impacts of indoor residential water use standards. If the administration believes the 2030 indoor residential standard should be delayed based on its findings, statute notes that it can recommend that the Legislature set an alternative date for implementation.

Figure 9

Legislative Oversight Included in Water Use Efficiency Laws

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DWR = Department of Water Resources; SWRCB = State Water Resources Control Board; and WUOs = water use objectives. |

How the Urban Water Use Objective Is Defined

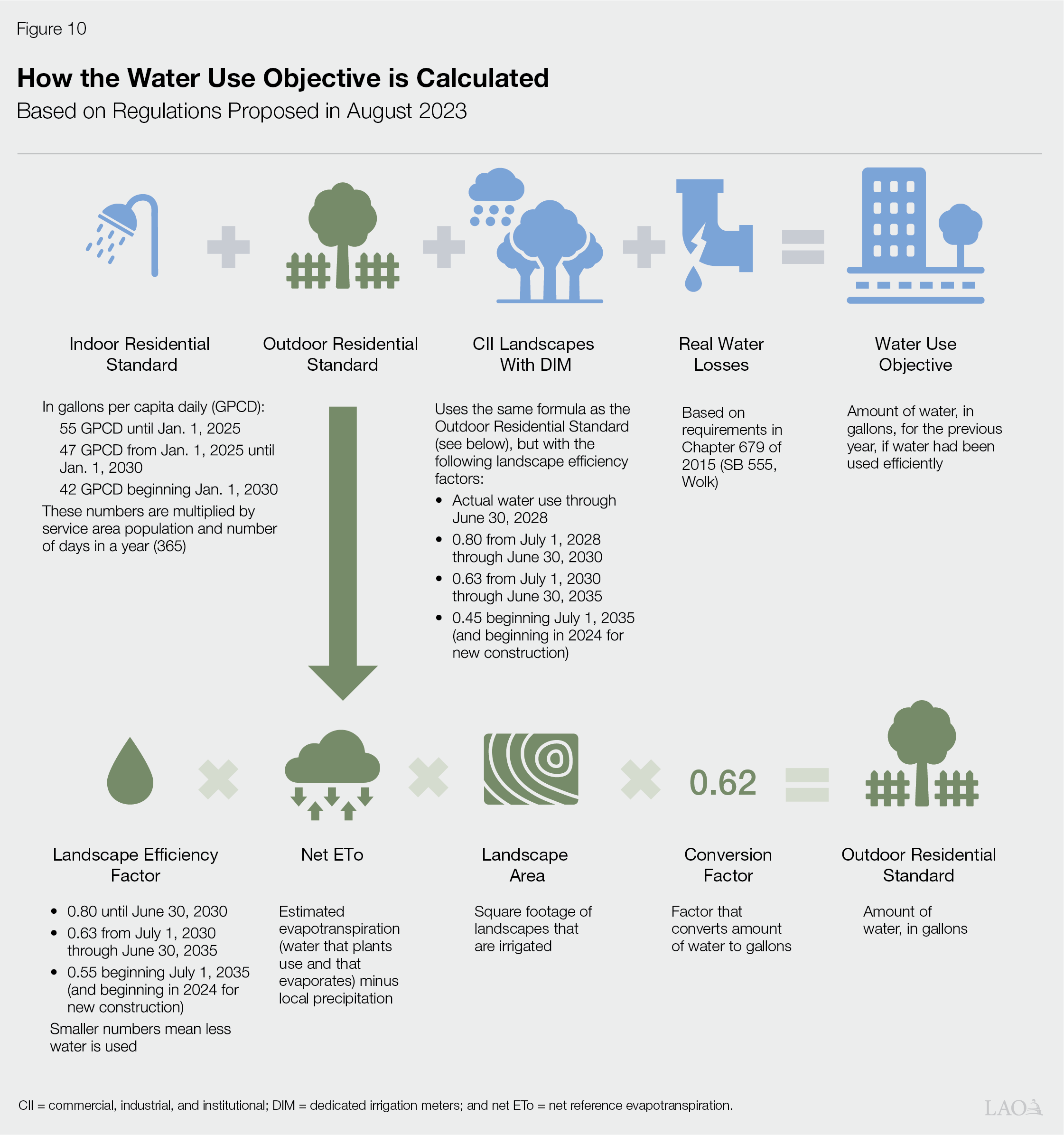

The WUO Is Analogous to a Water Budget for Efficient Use. The WUO is a volumetric measure of water, in gallons, that a supplier’s customers would have required in the previous year if water was being used efficiently. The WUO can be thought of as an annual water budget. This total amount of water is the sum of the four individual standards described below. However, with one exception (real water loss standards, as discussed below), suppliers do not need to achieve each of these individual standards; rather, they only must achieve the aggregate WUO. Achieving the WUO would mean the supplier did not use more water than “budgeted” by the WUO amount. In addition, individual customers are not required to meet any of the individual standards; the requirements for the WUO only pertain at the supplier level (although suppliers will rely on customers making behavioral changes to reduce water use). Figure 10 displays how the total WUO is calculated, based on statutory requirements and SWRCB’s proposed regulations.

- Indoor Residential Use. This standard is an amount of water that would be used indoors if water was being used efficiently and is measured in gallons per capita daily (GPCD). These standards were set by SB 1157, based on recommendations from DWR.

- Outdoor Residential Landscapes. This standard is based on four inputs, as shown in Figure 10, to factor in local conditions. This includes a “landscape efficiency factor,” which is a fractional number reflecting water use efficiency, with smaller numbers indicating less water used. This factor will be set in regulations. The second input (“net reference evapotranspiration”) is a measure of local precipitation, the water needs of plants, and estimated evaporation. The third input is a measure of irrigable residential land area, in square footage. The final input is a factor used to convert the amount of water into gallons. Legislation requires this standard to incorporate the principles of existing rules concerning newly constructed residential landscapes.

- CII Landscapes With Dedicated Irrigation Meters. This standard applies to CII customers’ outdoor landscapes, but only those that use a dedicated irrigation meter. (These meters measure only the amount of water used outdoors as compared to a mixed‑use meter which measures indoor and outdoor use together.) While the CII standard uses the same formula as the outdoor residential calculation, the specific metrics and time line differ. These standards also will be set in regulations. Legislation requires this standard to incorporate the principles of existing rules concerning newly constructed landscapes.

- Real Water Losses. This standard is an amount of water a supplier is allowed to lose through leakages in its system. Over time, the amount of lost water that is allowed and can be included in the WUO will decrease. Unlike the three previous inputs, suppliers must achieve the specified targets for real water losses, which are governed by previously approved statute (Chapter 679 of 2015 [SB 555, Wolk]) and corresponding regulations. In other words, they must not have water losses that are more than the amount in this standard, regardless of whether they can achieve their overall WUO through the other standards.

The WUO Can Be Increased to Account for Certain Local Factors. The above four standards are the primary inputs that comprise the annual WUO (or water budget) for a supplier. However, additional factors could increase a supplier’s WUO, including:

- Bonus Incentive for Potable Water Reuse. If a supplier augments its groundwater, reservoirs, or other sources of water supply with potable reuse water (that is, recycled water that is of drinking water quality), the proposed regulations would allow it to increase its WUO—by up to 15 percent of the WUO if the potable reuse water is produced at an existing facility or by up to 10 percent if it is produced at a new facility.

- Variances. Proposed regulations would allow a supplier to apply for a variance to increase its WUO if water for a specified unique use accounts for 5 percent or more of the supplier’s WUO, such as for evaporative coolers, significant seasonal population changes, or significant populations of horses or other livestock. On an annual basis, suppliers would have to apply for variances and receive approval from SWRCB to include the extra amount of water in their WUOs.

Suppliers With Lower‑Income Residents May Qualify for Five‑Year Extension on Outdoor Standards. Under the proposed regulations, suppliers whose service area has an average household income at or below 80 percent of the state’s median household income may be able to wait until 2040 (rather than 2035) to implement the lowest outdoor residential and CII landscape standards. This extension also could apply to suppliers that would otherwise be facing water reductions of 20 percent or more to comply with the 2035 requirements. Suppliers granted extensions still would have to demonstrate continued progress toward achieving their annual WUOs.

CII Performance Measures Create a Benchmarking System

The legislation not only requires water suppliers to include the amount of water used on CII outdoor landscapes as part of their annual WUOs, but also to implement performance measures for this use of water. The legislation requires SWRCB to adopt regulations for CII performance measures that (1) define a CII water use classification system, (2) identify best management practices for certain CII customers, and (3) set size thresholds above which a CII customer would have to convert from a mixed‑use irrigation meter to using a dedicated irrigation meter. Below, we describe how SWRCB has proposed to carry out these three legislative requirements, along with three additional requirements the board is proposing related to CII customers that were not required by statute.

Classify CII Water Users. Proposed regulations would require suppliers to classify their CII customers according to the federal Energy Star Portfolio Manager categories. (Currently, these consist of 18 categories, such as banking/financial services, health care, public services, retail, and technology/science.) In addition, proposed regulations would require suppliers to identify businesses that are associated with: (1) CII laundries, (2) large landscapes, (3) water recreation, and (4) car washes. Suppliers would have to classify at least 20 percent of CII customers by 2026, at least 60 percent by 2028, and 100 percent by 2030. After that, they would have to maintain classification of at least 95 percent of CII customers on an annual basis.

Implement Best Management Practices for Top CII Water Users. For top water users within each of the classification categories described above, proposed regulations would require suppliers to design and implement a conservation program for each customer that includes best management practices (such as bill inserts, rebates, irrigation system maintenance, collaboration with tree‑planting organizations, or changes to billing systems) from five different categories.

- For CII customers in the 80th percentile of water use, the program would need to include at least one best management practice from each of five categories.

- For CII customers in the 97.5th percentile of water use, the program would need to include at least two best management practices from each of the five categories.

Suppliers would have to achieve 20 percent compliance by 2026, at least 60 percent compliance by 2028, and 100 percent by 2030. After that, they would have to maintain at least 95 percent compliance on an annual basis.

Ensure Certain CII Customers Convert to Dedicated Irrigation Meters or Accepted Alternative. Proposed regulations would require suppliers to identify CII customers with large landscapes (defined as those that use 500,000 gallons of water or more annually) that use mixed‑use meters and convert those to dedicated irrigation meters or accepted alternatives. (These alternatives are a combination of practices from a menu of choices. For example, it could include using a water budget‑based rate structure and smart irrigation controllers, along with irrigation scheduling.) Suppliers would have to ensure that at least 20 percent of large landscapes in their service areas are converted by 2026, 60 percent by 2028, and 100 percent by 2030. Thereafter, each year they would have to ensure that at least 95 percent of large landscapes have a dedicated irrigation meter or an approved alternative. Water use associated with these landscapes would then be included in the annual WUO.

Ban Using Potable Water to Irrigate Nonfunctional Turf on CII Landscapes. Proposed regulations would ban irrigation of nonfunctional turf with potable water beginning on July 1, 2025. SWRCB’s regulations were proposed before approval of Chapter 849 of 2023 (AB 1572, Friedman), which has a similar prohibition that is phased in beginning in 2027.

Identify All “Disclosable” Buildings and Report Information About These Buildings. Proposed regulations would require suppliers to identify certain large CII buildings that are considered disclosable according to the California Code of Regulations. (A disclosable building has more than 50,000 square feet of area and has either no residential utility accounts or at least 17 residential utility accounts for each type of energy—electricity, natural gas, steam, fuel oil—serving the building.) For each disclosable building, suppliers would then have to provide to the building owner its water use data for the previous year. Suppliers would have to provide data for at least 20 percent of disclosable buildings by 2026, at least 60 percent by 2028, and 100 percent by 2030. This proposed requirement was not included in the water use efficiency legislation.

Report on Estimated Water Savings Achieved as a Result of Various Practices. For several of the above requirements, proposed regulations would require suppliers to report to the administration annually on the estimated amount of water saved. For example, suppliers would have to estimate water savings from having implemented best management practices with top water users.

Assessment

In this section we discuss our assessment of implementation of the water use efficiency framework to date, including some of the requirements in SWRCB’s proposed regulations. We highlight some of the challenges associated with the new requirements and, toward the end of this section, raise some questions for the Legislature to consider about the framework’s ultimate potential effects. Figure 11 summarizes our primary findings.

Figure 11

Assessment of Draft Framework

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Impacts to Individual Suppliers Will Vary Significantly

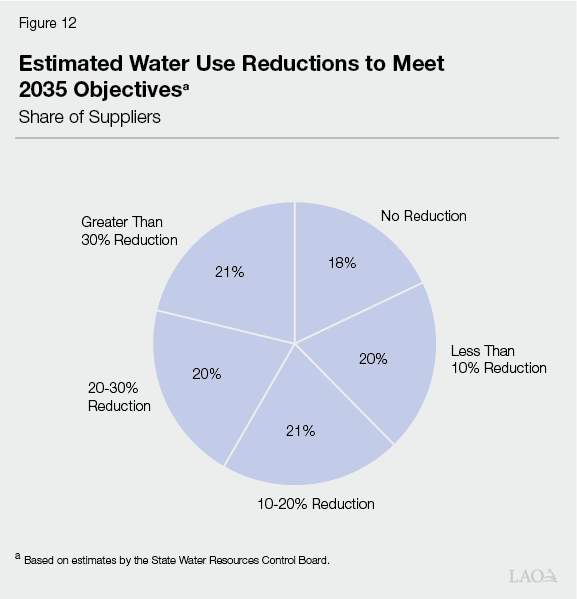

Statewide Reductions Needed to Meet Overall Water Use Objectives. SWRCB has developed a model (the Water Use Objective Exploration Tool) that takes water use data from 2017 through 2021 and creates estimates of what individual suppliers’ water use should be based on the various proposed standards. Cumulatively, SWRCB’s data indicate that suppliers across the state will need to make reductions of about 14 percent to meet 2035 WUOs. However, the actual reductions suppliers will need to make to achieve their individual WUOs will vary. As shown in Figure 12, the board estimates that some suppliers (18 percent) will not need to make any reductions to current water use to achieve the 2035 objective, and a similar share will need to make reductions of less than 10 percent. The board projects that the majority, however, will have to make reductions of at least 10 percent, and that about one in five providers will face reductions of 30 percent or more.

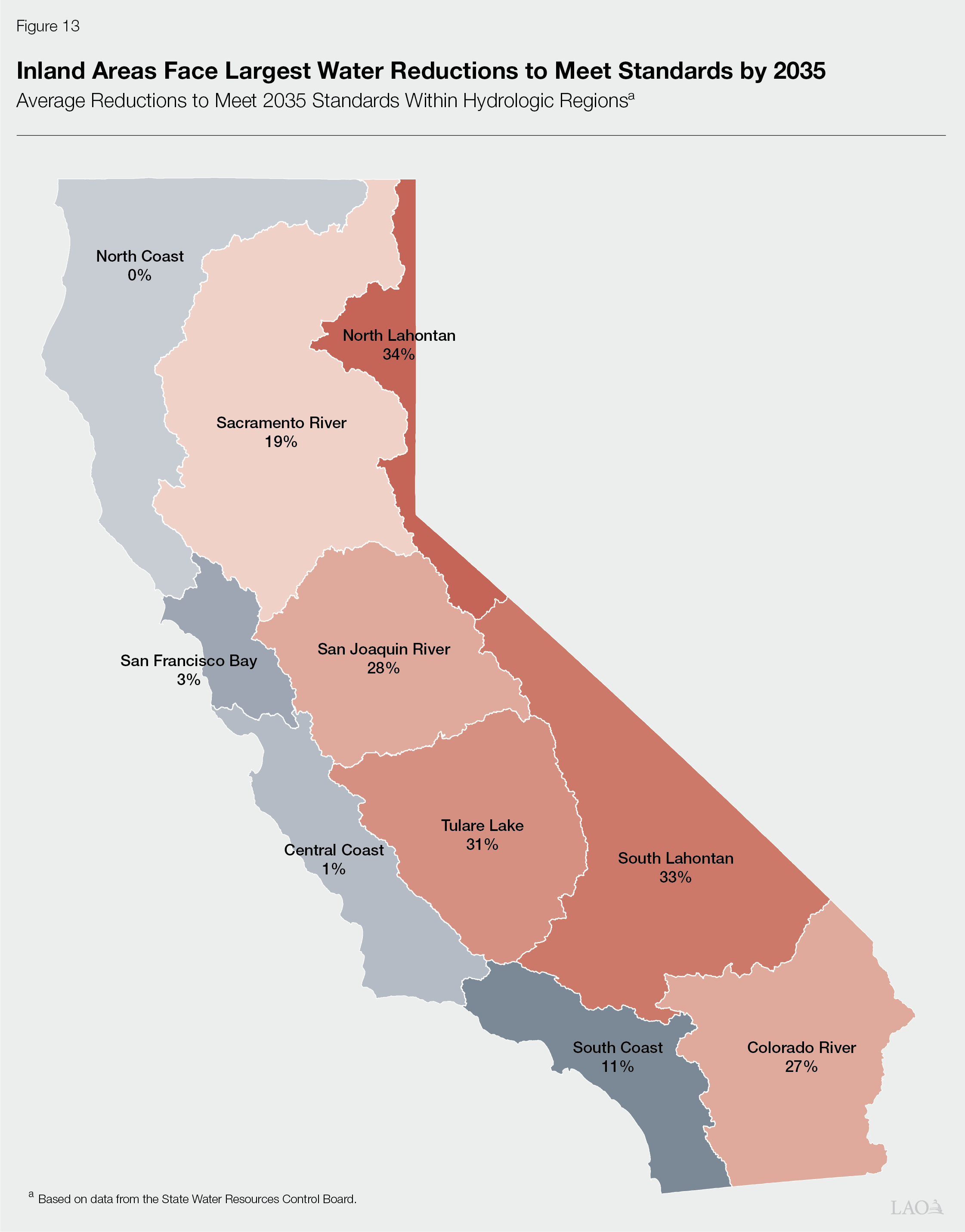

Size of Required Reductions Differs by Hydrologic Region. SWRCB’s data highlight some geographic trends in the water conservation actions needed to meet WUOs. Specifically, in aggregate, the inland hydrologic regions face much larger reductions than coastal regions, as shown in Figure 13. In particular, suppliers in the North Lahotan, South Lahotan, Tulare Lake, and San Joaquin River regions will need to make the largest cumulative reductions to meet their WUOs. However, notable variation also exists within regions. For example, although in the aggregate it appears that the 13 suppliers in the North Coast region do not face reductions, two of the individual suppliers serving more than 1.6 million customers will need to reduce water use by more than 25 percent to meet their 2035 objectives. (This distinction is because water use for 7 of the 13 suppliers already falls below their estimated 2035 WUOs, which masks the deficiencies for the remaining suppliers when all are considered together.)

Magnitude of a Supplier’s Reductions Depends on Several Factors. Each supplier’s WUO for the previous year will be unique due to the distinctive values entered into the WUO calculation. The amount by which an individual supplier must reduce water use also depends on its baseline water use, which in turn is contingent on several factors. For example, does the supplier already have conservation programs in place? Does it have water recycling facilities that produce potable reuse water so that it can access the bonus incentive? What are the characteristics of the supplier’s climate and are its customers used to having lawns?

Some Regions With Declining Water Use Still Face Additional Reductions. What does not appear tightly correlated to upcoming requirements is the magnitude of the previous water use reductions (in terms of percentage or GPCD) that were mandated by the Water Conservation Act of 2009. Specifically, while one might expect that regions that have already made significant water use reductions over the past several years would be closer to their efficient use targets and therefore face less steep additional reductions under the new standards, that does not necessarily seem to be the case. For example, water use in the Colorado River hydrologic region declined by 34 percent from the early 2000s to 2020, going from 386 GPCD to 256 GPCD. Under the new requirements, suppliers there must reduce water use by another 27 percent on average by 2035. In comparison, suppliers in the South Lahotan region both cumulatively already reduced water use by an even higher percentage than the Colorado River region—39 percent between the early 2000s and 2020, from 256 to 156 GPCD—and will have to reduce aggregate water use by an even higher percentage (33 percent) to achieve their 2035 WUOs.

Proposed Regulations Are Overly Complicated and in Places Lack Clarity

Pathway to Efficiency Is Unnecessarily Complex. The proposed regulations create undue complexity for water suppliers in several areas, without compelling justification. As one example, the CII performance measures and best management practices are particularly prescriptive and complicated, especially given the relatively small potential for outdoor water savings from this sector (which makes up less than 3 percent of statewide water use). For instance, the rationale for requiring suppliers to work with top water users within each of 22 different CII categories is unclear. Allowing them to focus on the top users overall, regardless of category, would be simpler and less prescriptive and likely could achieve as much or more water savings. Similarly, a supplier might wish to focus on all CII water users within a particular category. While still achieving water savings, they would have more flexibility in how they target and implement best management practices.

Additionally, the data and information that suppliers would have to collect to comply with the proposed CII performance measures would be extensive. While some of these data could be useful (as would a better understanding of how much water is used on outdoor CII landscapes), whether the significant amount of work and cost associated with its collection would be worth the small amount of water savings it might yield is questionable. Similarly, we have been unable to identify a strong justification for why SWRCB chose to include new reporting requirements related to disclosable buildings, given this was not a statutorily required activity.

SWRCB’s proposed approach to addressing variances (which allow a supplier to increase the amount of water in its WUO for unique uses of water) also is unnecessarily complicated. The proposed regulations would require a high threshold (5 percent of the total WUO) for requesting a variance, which could exclude some suppliers that might merit this accommodation. Moreover, the proposed approach would create a cumbersome data submission, application, and approval process, likely resulting in substantial work for both suppliers and SWRCB—and would require conducting these activities every year. For some of the variances, the process could be prohibitively burdensome for suppliers and dissuade them from applying for the adjustment even when it might be appropriate and help them meet their WUOs. Why SWRCB is proposing such an extensive process when the same policy goals likely could be achieved in a simpler fashion is not clear.

Certain Implementation Details Remain Unclear in Statute and Proposed Regulations. Certain details about how the state and local suppliers would implement the proposed regulations have not yet been clarified. Below are two examples.

- Who Will Collect Residential Landscape Data Going Forward? The total square footage of irrigable land included in the outdoor residential standard has a significant impact on a supplier’s total WUO. Yet measuring these landscapes and determining how much is currently irrigated is a challenging and labor‑intensive undertaking. DWR worked with a contractor to conduct these measurements for outdoor residential landscapes in 2018 using aerial imagery and other techniques (at a cost of about $7 million, covered by the state’s General Fund). This was a point‑in‑time assessment. Given the importance of this information to the total WUO calculation, the question remains of how often these data should be updated and by whom. Some providers—particularly the smaller ones—might not have the capacity to collect this information and conduct the analyses for their service areas, yet whether the state can and will prioritize funding for DWR to continue to do it on a statewide basis also is uncertain.

- How Will the Proposed Regulation Work With a New Law Limiting Nonfunctional Turf on CII Landscapes? Since SWRCB proposed the water use efficiency regulations, the Legislature enacted separate legislation—AB 1572—to prohibit the use of potable water for irrigation of nonfunctional turf on CII landscapes. This statutory ban will begin in 2027 for public properties, 2028 for other CII properties, and 2029‑2031 for remaining properties. SWRCB’s proposed ban, which is similar in nature, would begin in 2025, raising questions around which deadlines suppliers will need to follow.

Proposed Reporting Periods Could Create Accounting Challenge. Some water suppliers operate on a calendar‑year basis (January to December), while others operate on a fiscal‑year basis (July to June). Although statute technically allows suppliers to use either time frame for the new required water use efficiency reporting, the proposed regulations would require them to report using only the fiscal year time line. SWRCB indicates it made this decision to align with changes enacted through AB 1414 in 2019. (Assembly Bill 1414 changed the water use efficiency reporting deadline from November 1 each year to January 1 each year, meaning it would be impractical for suppliers to submit a report for the previous calendar year ending December 31 on the next day, January 1.) Suppliers that operate on a calendar‑year basis have noted that this proposed approach could create an accounting challenge and would be inconsistent with other state reporting requirements—such as Urban Water Management Plans, water loss reporting, and electronic annual reports—for which water suppliers have discretion about which time frame to use.

Achieving the Water Use Objective Likely to Be Challenging and Costly

Some Suppliers Lack the Staffing or Expertise Needed to Comply With New Rules. Based on numerous interviews we conducted for this report—including with the Governor’s administration, an association representing water suppliers, researchers, consultants, and some individual suppliers—we learned that a sizeable share of suppliers lack awareness about what is required of them under the proposed regulations and may be challenged to fulfill the requirements. While some suppliers have staff dedicated to water conservation programs, others—particularly those that are smaller—have fewer staff and no one to focus primarily on these efforts. Even larger suppliers indicated they likely will need more staff and/or outside consulting contracts to comply with the requirements. Moreover, existing staff may lack the capacity or expertise to collect and analyze relevant data to develop the WUO and implement the CII performance measures. For example, staff will need to be deployed to locate dedicated irrigation meters and delineate which areas are irrigated. If they are not using DWR‑provided data, they will need to measure outdoor landscapes; if they are using the information DWR provided, they need to be able to analyze the data. These activities require sufficient time and expertise that some suppliers do not have.

Standards Could Be Difficult to Achieve. The WUO is built on numerous individual inputs, which get increasingly stringent over time. These standards could be hard to achieve, especially in later years. This might create unrealistic expectations for the state about the amount of water savings that are possible. This is particularly true for the proposed 2035 outdoor residential water use standard for existing landscapes. The 2035 standard proposed by SWRCB for existing outdoor residential landscapes uses the current standard for the design of newly constructed landscapes (per legislation approved in 2015). Under that 2015 design standard, however, the newly constructed landscapes do not ultimately have to perform to that level. Indeed, suppliers have noted that the performance of these landscapes often falls short of their design, meaning they end up using more water than intended. This can be due to a variety of factors. For example, if a resident does not maintain the landscape properly or waters at the wrong time, or if a subsequent resident at the same property adds new plants or trees, this can increase water use over time.

The 2018 water use efficiency legislation called for the outdoor residential standard to incorporate principles of the existing design rules, meaning it should take into account factors such as evapotranspiration and landscape area. However, the legislation did not stipulate that the outdoor residential standard for existing landscapes specifically use the same efficiency factor (0.55) required by the 2015 statute for newly constructed landscapes. Moreover, in its report to SWRCB, DWR recommended setting the standard at a less stringent level (0.63) than the design standard. Yet, SWRCB proposes using the design requirements as the standard for the new WUO. Given the challenges in achieving that standard in practice on newly designed landscapes, achieving it on existing landscapes likely will be even more challenging for residents (and, in aggregate, for suppliers).

Theoretically, Flexibility Is Built Into the Framework… Certain components of the water efficiency framework are designed to offer suppliers flexibility around how they meet the new requirements. Specifically, as described earlier, suppliers must achieve the WUO in the aggregate; except for the water loss standard, they need not achieve each of the individual standards. For example, a particular supplier’s residential customers might use more water outdoors than the established standard, but less water indoors. In such a case, the supplier still could achieve its WUO since the lower indoor use would offset the greater outdoor use. In addition, they have some flexibility about which data to use in the WUO calculations. For example, they can use the data provided by DWR for outdoor residential landscapes, or they can conduct their own surveys and use that data (provided it is of sufficient quality). Suppliers also have choices about how to make the water use reductions necessary to achieve their WUOs. For example, statute does not prescribe specific conservation programs or activities.

…However, Tightened Individual Standards in SWRCB’s Proposed Regulations Could Reduce Local Options. While AB 1668 expressed legislative intent for suppliers to retain flexibility in how they design and implement water conservation strategies, SWRCB’s proposed regulations likely reduce flexibility in actual practice. One key challenge is that SWRCB is proposing to set individual standards at more stringent levels than DWR recommended in the report it submitted to the board to inform development of the regulations. Specifically, as displayed in Figure 14, the proposed regulations would require water suppliers to comply with even more rigorous thresholds for outdoor residential use (as noted above), CII landscapes, and CII performance measures. These more stringent requirements will remove much of the “wiggle room” that suppliers might have been able to take advantage of under DWR’s less severe recommended standards. That is, in practice, suppliers might have to achieve each individual standard if they hope to achieve the aggregate WUO under the proposed regulations. Moreover, the proposed regulations lack any allowance for inaccuracies in the data that define the inputs, which summed together comprise the WUO. In only one instance are suppliers provided a buffer—if they would not otherwise be able to achieve the WUO, they can include up to 20 percent of residential land area that is currently unirrigated, but could have been irrigated in the past or could be irrigated in the future. However, this buffer is allowed only through June 30, 2027. Although DWR recommended distinguishing between irrigated and unirrigated when assessing irrigable landscapes—which goes beyond what was included in AB 1668—it recommended always including a 20 percent buffer. Under SWRCB’s more stringent approach, the lack of cushion around the data (where inaccuracies could have an impact on the WUO calculation) further reduces supplier flexibility in achieving the WUO.

Figure 14

How SWRCB’s Proposed Regulations Differ From DWR’s Recommendations

|

DWR Recommendationa |

SWRCB Proposed Regulation |

|

|

Residential Outdoor Standard |

Include 20 percent of land area that could be irrigated, but is not currently, in the WUO.b |

Until June 30, 2027, allow up to 20 percent of land area that could be irrigated, but is not currently, to be included in the WUO, if the supplier would otherwise not achieve the WUO. No unirrigated land area could be included after that date. |

|

Set the final landscape efficiency factor at 0.63 beginning in 2030. |

Adopt DWR recommendation until 2035 but further reduce the landscape efficiency factor to 0.55 beginning July 1, 2035. |

|

|

CII Landscapes With Dedicated Irrigation Meters |

Set the final landscape efficiency factor at 0.63 beginning in 2030. |

Adopt DWR recommendation until 2035 but further reduce the landscape efficiency factor to 0.45 beginning July 1, 2035. |

|

CII Performance Measures |

Require conversion to dedicated irrigation meter (or alternative) if land area is one acre or more in size. |

Require conversion to dedicated irrigation meter (or alternative) if the customer uses 500,000 gallons or more per year. |

|

N/A |

Require suppliers to provide water use data to owners of “disclosable buildings” (certain types of large buildings). |

|

|

aBased on statutory reports DWR submitted to SWRCB in September 2022. bStatute does not distinguish between irrigated and unirrigated landscapes, but rather requires the residential outdoor standard be applied to “irrigable” landscapes. |

||

|

SWRCB = State Water Resources Control Board; DWR = Department of Water Resources; WUO = water use objective; and CII = commercial, industrial, and institutional. |

||

An additional impediment to suppliers’ flexibility stems from legislation, not the proposed regulations. Specifically, the statutory requirement for a standalone water loss standard established by SB 555 in 2015 prohibits a supplier from potentially exceeding this threshold but meeting its overall WUO by reducing more water under one or more of the other three individual standards.

Water Reductions Are Dependent on Customer Behavior, and Many of the Easy Changes Already Have Been Made. To achieve WUOs, suppliers will depend on customers making changes to reduce their water use. For example, customers will need to fix water leaks, replace inefficient appliances and toilets with more efficient models, convert lawns and landscapes to use less water, and use more efficient outdoor watering systems. To help achieve these actions, suppliers can encourage, support, and incentivize behavioral change, or they can mandate or prohibit certain activities (for example, they can ban watering on certain days or require the use of hoses with shut‑off valves). Mandating that customers take on major projects, such as lawn conversions, likely is not a practical or feasible approach. To comply with the earlier 20x2020 requirements, many suppliers created voluntary rebate programs and customers responded. However, that means many customers—particular early adopters—have already replaced appliances and fixtures (and to a lesser degree, turf) with higher efficiency alternatives and suppliers therefore will not be able to gain much more savings from them. Suppliers could have more difficulty convincing the remaining customers to modify their residences and behaviors, particularly lower‑income customers who are less able to afford to make significant changes as well as customers who are less motivated by incentives.

Compliance Will Raise Costs for Suppliers—Potentially Significantly—at Least in the Near Term. Suppliers’ costs likely will increase over the next decade as they approach the 2035 compliance deadline. Such costs will include offering incentive programs, conducting education and outreach, and repairing system leaks. In addition, suppliers may need to increase staffing and/or contract out to comply with the new requirements. At the same time, their revenues likely will decrease if they are selling less water as customers conserve, since their rates typically are charged on a volumetric basis. (Their overall costs could be offset to some degree if decreased demand results in a drop in how much water they need to procure or produce.) Costs to implement the requirements could be significant, particularly for suppliers that already are comparatively behind in their conservation practices or do not have potable reuse water they can use to supplement their water supply and access the bonus incentive. Some suppliers have outside sources of revenue (such as land leases or hydropower energy facilities), but some rely exclusively on customer ratepayers to support their operations. The latter group will feel the cost pressures more acutely than those that can turn to other revenue options to undertake water conservation activities.

State Technical Support Cannot Address Toughest Local Challenges. Although DWR and SWRCB have provided many public forums, educational materials, and online tools, these forms of assistance do not directly lower costs for suppliers, nor aid suppliers in addressing some of the tougher challenges associated with achieving WUOs. For example, ensuring that residents effectively maintain drought‑tolerant landscapes likely will be costly and difficult for suppliers, and—absent providing additional funding—there is not much that the state can do to induce these individual‑level actions.

Overly Aggressive Time Lines Could Have Unintended Consequences. Although SWRCB’s regulations are scheduled to be finalized two years later than statute originally intended, none of the subsequent deadlines for suppliers have been changed. These statutory time lines likely will be difficult for suppliers to meet—particularly given the delay in defining specific regulatory requirements—and could lead to adverse outcomes. For example, a significant shift in how residents design, redesign, and maintain their yards will be required to achieve the state’s desired outcomes and many lawn conversions will be required. If this process is rushed, it could have unintended consequences, such as customers simply not watering their landscapes and trees (rather than converting them to drought‑tolerant landscapes) or replacing grass with artificial turf or other surfaces that increase heat. The potential negative impacts associated with these outcomes are not what the state is seeking with the water use efficiency framework.

Framework Could Create Disproportionate Impacts on Lower‑Income Californians

Potential Rate Increases Could Be Particularly Burdensome for Lower‑Income Customers. Affordability already is a problem for some Californians. In its 2022 Drinking Water Needs Assessment, which examined affordability among community water systems, SWRCB found that more than one‑third of the 2,868 water systems it assessed had at least one indicator of unaffordability. Leveraging rates to achieve conservation can be an effective tool in some cases. To the degree suppliers increase rates to cover the cost of implementing and achieving the WUO, however, the existing affordability problem could be exacerbated for lower‑income customers. For example, if lower‑income customers already limit their water use as a cost savings measure, they may have less room to make further reductions to compensate for potential rate increases. In a recent study of Santa Cruz County, Stanford University researchers found that during the multiyear drought that ended in 2016, increased water rates and drought surcharges raised water bills for lower‑income customers while simultaneously lowering bills for higher‑income customers (who were able to reduce their water use to more than offset higher charges).

Many Suppliers Cannot Offer Customer Assistance Programs. Suppliers that rely exclusively on their ratepayers for revenue cannot offer customer assistance programs to help offset cost increases associated with implementing the new framework. This limitation is due to rules that were added to the state Constitution by voter‑approved Proposition 218 in 1996 requiring that property‑related fees, such as water rates, benefit the ratepayer directly. Consequently, a supplier cannot use the rate revenues collected from higher‑income customers to subsidize the rates charged to lower‑income customers. Some suppliers use revenues from other sources (such as land leases) to lower the bills of qualifying lower‑income customers, but this option is not available for all suppliers. This means that some suppliers have limited options for helping ameliorate the impacts that higher costs stemming from water conservation activities might bring for lower‑income households.

Incentive Programs Can Be Challenging for Lower‑Income Customers to Use. The types of strategies that water suppliers historically have used to reduce water use may present difficulties for lower‑income households. Suppliers typically provide incentive programs (such as rebates for replacing inefficient fixtures, appliances, or lawns with more efficient options) as reimbursements to customers. This means the customer pays for the replacement and then applies for reimbursement. Moreover, rebates typically do not cover the full cost of the replacement materials and labor. For lower‑income customers, this model may not work because they may struggle to afford both the up‑front costs and the difference between the rebate amount and the total cost of replacement.

Water Savings Due to Conservation Framework Likely to Be Modest

Some Reductions Will Continue to Occur Regardless of This Framework. As noted previously, urban water use already has declined in recent years, in large part due to several multiyear droughts; the 20x2020 requirements; and customers replacing inefficient appliances, fixtures, and lawns. In addition, a previous law established requirements that landscapes at new developments be designed more efficiently. These existing local programs and behavioral changes in water use by customers likely will result in additional water savings over time, even without the new requirements. For example, SWRCB estimates that even without the proposed new regulations, annual water use in 2035 would be 7.4 percent lower than average annual water use over the 2017‑2019 period.

California Continues to Have Some Untapped Conservation Potential… Additional opportunities for conservation exist, however. For example, not all customers have replaced inefficient appliances or converted their lawns and landscapes. Recent research from the Pacific Institute estimates that future annual urban water use could be reduced by 30 percent to 48 percent compared to average annual levels between 2017 and 2019. (This research was not specifically predicting the impacts of the new requirements, but rather the potential for water savings more generally, given available technologies and practices.)

…However, Total Amount of Water Conserved Due to This Framework Likely to Be Modest. Relative to what annual urban water use would otherwise be in 2035 if the proposed regulations were not enacted, SWRCB estimates that the new requirements will result in a reduction of approximately 440,000 acre‑feet annually. Although this would reflect a 9 percent additional decline compared to SWRCB’s estimated baseline declining trends, the estimated amount of water saved would represent only a small fraction—about 1 percent—of the state’s current total water use. For comparison, as displayed earlier in Figure 2, the agricultural sector uses about four times as much water as the urban sector.

Unclear How Any Water Savings Would Be Used

The 2018 Legislation Does Not Directly Address How to Use Any Water Savings. If the state were able to conserve several hundred thousand acre‑feet of water due to these new requirements, how it should account for or redirect those savings is unclear. Senate Bill 606 and AB 1668 did not speak to this issue. In drought years, when less water is available, water conservation practices would help align demand with the lower supply. In wetter years, however, the decreased demand would presumably result in more available unused water. This raises a key question: how should the state account for that freed‑up water and how should it be used, if at all? For example, if a local supplier is able to store the excess water, this would increase its resilience during the next dry period. However, the location of water savings will not necessarily align with where future shortages might occur. If a particular supplier saves significant water in a wet year but has nowhere to store it, those savings will not help buffer its shortages during a drought. Who will or should benefit from those savings?

As Water Use Efficiency Increases, Fewer Options for New Water Use Reductions Are Available During Droughts… Although prior and newly adopted water conservation practices will help reduce ongoing demand for water—which could alleviate pressure on the system during droughts—they also mean that fewer new, immediate options will be available to respond to acute drought conditions. For example, once appliances have been replaced with more efficient models and lawns have been converted to drought tolerant landscapes, suppliers cannot turn toward those options during a severe or prolonged drought if supplies are running low and additional reductions are needed. This will represent a contrast in how the state has responded to droughts in the past, when it has turned to residents to take both temporary and permanent actions to immediately reduce water use in response to limited supplies. That is, the state and local suppliers will have fewer new “levers to pull” to further reduce demand if needed.

…However, Even Modest Water Savings Could Help Facilitate Greater Drought Resilience, Depending on Local Circumstances. During wet years, the water saved due to this framework—even if modest—could be banked for use during dry years. For example, excess water could be used for groundwater recharge or added to surface storage. However, not all suppliers have this option, depending on their facilities, resources, and specific circumstances. Greater conservation could benefit suppliers that import water (because they do not have their own dedicated water source) in both wet and dry years, as they will need to buy less water for their customers as the efficient use of water increases. As such, the amount of drought resilience that water conservation provides both at a local level and statewide will depend on the water sources and storage options available.

Unclear if Framework’s Benefits Will Outweigh the Costs

Although SWRCB Estimates That the Benefits of Implementing the Framework Will Outweigh Associated Costs… As shown in Figure 15, SWRCB estimates that the framework will result in cumulative statewide benefits of $16 billion over the 2025 through 2040 period and cumulative costs of $13.5 billion. The board estimates the benefits would accrue to both urban water suppliers (from having to supply less water) and residential customers (from having to buy less water). The costs will be borne primarily by suppliers, wastewater agencies, and customers. The costs to suppliers would result from paying for various incentive programs coupled with lost revenues from selling less water. Costs to wastewater treatment agencies would result from less water entering the system (we do not address these costs in this report, although legislation requires the administration to prepare a separate report related to this issue by October 1, 2028). Suppliers and wastewater agencies will pass much of their costs on to customers through raising rates. The costs to residential customers would result from higher rates and paying to replace inefficient fixtures, appliances, and lawns (the portion not covered by rebates).

Figure 15

SWRCB’s Estimates of the Costs and Benefits

of the Water Use Efficiency Framework

Cumulative Costs and Benefits From 2025 Through 2040 (In Billions)

|

Entity |

Cost |

Benefit |

|

Urban retail water suppliers |

$9.9 |

$10.6 |

|

Wastewater management agencies |

2.5 |

Not quantified |

|

Residential customers |

1.0 |

5.5 |

|

Urban forestry and landscape management agencies |

0.1 |

Not quantified |

|

Totals |

$13.5 |

$16.0 |

|

Note: Amounts may not add due to rounding. |

||

|

SWRCB = State Water Resources Control Board. |

||