February 22, 2024

The 2024‑25 Budget

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

- Overview

- State Prison and Parole Population and Other Biannual Adjustments

- Prison Capacity Reduction

- Voice Calling

- Utilities

- COVID‑19 Health Care Costs

- Prison Medical Care Budget Shortfall

- Contract Medical Services

- Parole Support Staffing

Summary

In this brief, we provide an overview of the total amount of funding in the Governor’s proposed 2024‑25 budget for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), as well as assess and make recommendations on several specific budget proposals. Below, we provide a summary of some of our major recommendations.

Prison Capacity Reduction. The Governor proposes reductions to CDCR’s funding to account for previous capacity reductions and for the planned deactivation of a prison in March 2025. In addition, the budget reflects operation of nearly 15,000 empty beds in 2024‑25, which is projected to grow to about 19,000 by 2028. This means the state could deactivate around five additional prisons. However, the administration indicates that doing so could create challenges, such as reducing the availability of treatment and reentry programs. We find that, while mitigating such challenges could create some new costs, these would be far less than the nearly $1 billion needed to continue operating five prisons. Accordingly, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to begin planning to reduce capacity by deactivating prisons and report on how to mitigate any resulting challenges.

COVID‑19 Health Care Costs. The Governor proposes $38 million ongoing General Fund for CDCR COVID‑19 health care costs. We find that the department’s proposed methodology to estimate its funding need is flawed because it does not factor in recent trends in COVID‑19 prevalence or projected declines in the prison population. Additionally, CDCR has not explored options to reduce costs by leveraging employee health insurance. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature withhold action on the budget‑year request and direct CDCR to update the proposal to address our concerns. We also recommend that the Legislature reject the funding proposed for the future years.

Prison Medical Care Budget Shortfall. The Governor proposes a $40 million one‑time General Fund augmentation in 2024‑25 to cover projected overspending in the prison medical care budget. We find that, in recent budget years, CDCR has been able to address its overspending without an augmentation by using savings elsewhere in its budget. However, the proposal does not make it clear why the department cannot continue to do so. In addition, the department did not provide adequate justification on how it projected the shortfall. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal.

Contract Medical Services. The Governor proposes various changes to the budgeting methodology used in the biannual adjustment process that would result in a net increase of $24 million for contract medical services in 2024‑25. We find that some of the proposed changes appear reasonable and would better align the department’s budget with its actual needs. However, we find that other changes are lacking because they would not account for changes in the size or makeup of the prison population. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature withhold action on the proposal and direct CDCR to submit a revised proposal at the May Revision that addresses our concerns.

Overview

Roles and Responsibilities. CDCR is responsible for the incarceration of certain adults convicted of felonies, including the provision of rehabilitation programs, vocational training, education, and health care services. As of January 17, 2024, CDCR was responsible for incarcerating about 93,900 people. Most of these people are housed in the state’s 32 prisons and 34 conservation camps. The department also supervises and treats about 35,300 adults on parole and is responsible for the apprehension of those who commit parole violations. In addition, the department operates the Pine Grove Youth Conservation Camp to provide wildland firefighting skills to justice‑involved youth from counties that have entered into contracts with CDCR.

Operational Spending Proposed for 2024‑25. The Governor’s January budget proposes a total of about $14.5 billion to operate CDCR in 2024‑25, mostly from the General Fund. Figure 1 shows the total operating expenditures estimated in the Governor’s budget for the prior and current years and proposed for the budget year. As the figure indicates, the proposed spending level reflects a decrease of $493 million (3 percent) from the revised 2023‑24 level. This decrease primarily reflects proposed reductions associated with the declining prison population and deactivation of facilities, various proposed General Fund budget solutions, and expiration of previously authorized one‑time spending. These reductions are partially offset by various proposed augmentations, such as funding for increased costs associated with providing medical care to people in prison and paying for workers’ compensation claims. (The proposed $493 million decrease does not reflect anticipated increases in employee compensation costs in 2024‑25 because they are accounted for elsewhere in the budget.) The proposed budget would provide CDCR with a total of about 61,200 positions in 2024‑25, a decrease of about 1,000 (2 percent) from the revised 2023‑24 level.

Figure 1

Total Expenditures for Operation of CDCR

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2022‑23 Actual |

2023‑24 Estimated |

2024‑25 Proposeda |

Change From 2023‑24 |

|||||

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||||||

|

Adult Institutions |

$12,597 |

$13,243 |

$12,923 |

‑$321 |

‑2.0% |

|||

|

Adult Parole |

695 |

703 |

701 |

‑2 |

— |

|||

|

Administration |

842 |

956 |

789 |

‑167 |

‑18.0 |

|||

|

Juvenile Institutionsb |

212 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|||

|

Board of Parole Hearings |

70 |

79 |

76 |

‑3 |

‑4.0 |

|||

|

Totals |

$14,415 |

$14,982 |

$14,488 |

‑$493 |

‑3.3% |

|||

|

aDoes not reflect anticipated increases in employee compensation costs because they are accounted for elsewhere in the budget. bLegislation approved as a part of the 2020‑21 budget package realigned responsibility for youths previously housed in state institutions to the counties. |

||||||||

|

CDCR = California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. |

||||||||

Capital Outlay Spending Proposed for 2024‑25. The Governor’s budget proposes total expenditures of $83.3 million ($959,000 General Fund) for capital outlay projects in 2024‑25. This amount includes (1) $82.4 million in previously authorized General Fund lease revenue bonds for various counties to construct or renovate correctional facilities and (2) $959,000 in additional General Fund proposed for the preliminary plans phase of a project to construct a potable water treatment system at the California Health Care Facility in Stockton.

State Prison and Parole Population and Other Biannual Adjustments

Background

Adjustments Proposed Biannually Based on Projected Population Changes and Other Factors. As part of the Governor’s January budget proposal each year, the administration requests adjustments to CDCR’s budget based on projected changes in the prison and parole populations in the current and budget years. The adjustments are made both on the overall populations and various subpopulations (such as people housed in reentry facilities and sex offenders on parole). In addition, some adjustments include factors other than population trends, such as inflation adjustments. The administration then modifies both types of adjustments based on updated information each spring as part of the May Revision.

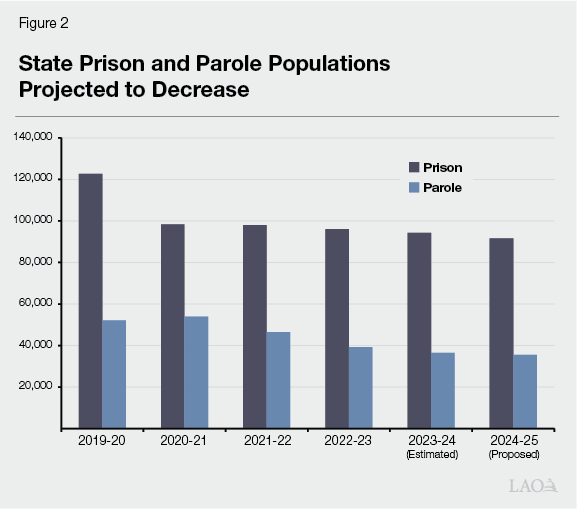

Prison and Parole Population Projected to Decrease in 2024‑25. As shown in Figure 2, the average daily prison population is projected to be 91,700 in 2024‑25, a decrease of about 2,500 people (3 percent) from the estimated current‑year level. The average daily parole population is projected to be 35,500 in 2024‑25, a decrease of 1,000 people (3 percent) from the estimated current‑year level. The projected decrease in the prison population is primarily due to the estimated impact of various sentencing changes enacted in recent years. The projected decrease in the parole population is primarily due to recent policy changes that have reduced the length of time people spend on parole by allowing them to be discharged earlier than otherwise.

Governor’s Proposal

Net Increase in Current‑Year Adjustments. The Governor’s budget for 2024‑25 proposes, largely from the General Fund, a net increase of $20.4 million in current‑year adjustments. The current‑year net increase in costs is primarily due to both a higher total prison population and increased pharmaceutical costs relative to what was assumed in the 2023‑24 Budget Act. This increase in costs is partially offset by various factors, including projected decreases in costs related to a lower‑than‑expected parole population and population receiving substance use disorder treatment in prison.

Net Increase in Budget‑Year Adjustments. The budget also proposes a net increase of $8.4 million in adjustments in the budget year. The budget‑year net increase is primarily due to increases in (1) pharmaceutical costs; (2) reimbursements to local governments for costs they incurred in connection with state prisons, such as by providing coroner services; and (3) the number of voice calling minutes used by people in prison. This increase in costs is partially offset by various factors, including projected decreases in costs related to declines in the prison and parole populations.

Recommendation

Withhold Recommendation Until May Revision. We withhold recommendation on the administration’s overall biannual adjustments until the May Revision. We will continue to monitor CDCR’s populations and the other factors affecting the proposed adjustments and make recommendations based on the updated information available at the May Revision, including the administration’s revised population projections. However, we have specific recommendations on adjustments related to voice calling, utilities, contract medical services, and parole support staffing, which we discuss elsewhere in this brief.

Prison Capacity Reduction

Background

State Currently Operating 32 Prisons. As of January 17, 2024, CDCR was responsible for incarcerating a total of about 93,900 people—89,100 men, 4,200 women, and 600 nonbinary people. Most of these people—about 90,800—are housed in 1 of 32 prisons owned and operated by the state. This includes 30 men’s prisons and 2 women’s prisons. (People who are transgender, nonbinary, or intersex are generally required to be housed in a men’s or women’s facility based on their preference.) The remaining people are housed in various specialized facilities outside of prisons, such as conservation camps and community reentry facilities.

Many Factors Affect Prison Housing Placements. Prisons are typically composed of multiple facilities (often referred to as “yards”) where people live in housing units, recreate, and access certain services (such as dental care). CDCR typically clusters people with similar needs (such the amount of security they require) in the same yard. Accordingly, prisons differ in their ability to meet specific needs based on the types of yards they are composed of. Some of the key needs that CDCR staff consider in identifying an appropriate housing placement for each person include:

- Security. CDCR categorizes most of its men’s yards into a range of security levels. (Women’s yards are not classified into different security levels as they generally have similar levels of security.) People housed in higher‑security yards live in cells, while people housed in lower‑security yards generally live in open dormitories. In some cases, people with the same security level must still be housed separately due to safety concerns. For example, this can be the case for members of opposing gangs who may try to harm each other.

- Health Care Treatment. Health care needs can affect which prisons people are housed in. For example, people with higher medical needs are typically placed at prisons designated as Intermediate Health Care institutions. This generally means that they are closer to community hospitals to facilitate access to specialty care. In addition, people receiving mental health care services are not housed at certain prisons located in desert regions of the state as they are more likely to be taking heat‑sensitive medications. Health care needs can also affect the specific yard within a prison that people are placed in. For example, people receiving the highest level of outpatient mental health care—referred to as the Enhanced Outpatient Program—are generally housed together in dedicated yards. These yards generally include housing units with medication distribution rooms that allow nurses to prepare and distribute medications inside the housing unit to improve medication compliance. In contrast, other people are typically expected to go to a centralized medication dispensary to receive their medications.

- Other Needs. Various other factors can affect where people are housed. For example, nine prisons have restrictions to mitigate the impact of Valley Fever—an infection caused by a fungus in the soil that enters people’s lungs when inhaled. Accordingly, people who have certain medical conditions that put them at higher risk of getting very sick or dying from Valley Fever are not housed at these prisons. In addition, certain prisons do not have the necessary physical features to accommodate people in wheelchairs.

People in Prison Are Typically Assigned to Work, Education, and/or Treatment and Reentry Programs. When people arrive in prison, they receive various assessments. These include assessments for substance use disorder, literacy, risk of recidivism (meaning their likelihood of reoffending after release), and criminal risk factors that contribute to their potential for recidivism (such as having challenges with anger management or a need for employment skills). Results of these assessments and other considerations—such as people’s interests and time before release—help CDCR staff match people to assignments, which fall into three general categories:

- Work. Some jobs assigned to people in prison—such as cleaning, maintaining, and repairing facilities; providing clerical support; and grounds keeping—are focused on supporting prison operations. Other jobs—such as manufacturing traffic signs and license plates—provide goods or services purchased by state agencies. Jobs typically pay between $0.08 and $1.00 per hour depending on various factors, such as the amount of skill required.

- Education. CDCR provides academic education classes ranging from adult basic education to college as well as technical education in a variety of career fields. Upon completion of a class, people receive credits that reduce the amount of time they must serve in prison. For example, people can earn one week of credit for completing a high school algebra course. In addition, upon completion of certain educational milestones, such as completion of a high school equivalency program, people can receive up to 180 days of credit.

- Treatment and Reentry Programs. CDCR provides cognitive behavioral treatment programs intended to help people change negative patterns of behavior, such as anger management or substance use disorder programs. In addition, CDCR offers courses focused on workforce readiness and financial literacy that are intended to help people prepare for reentry into their communities. People also receive credits for completing these treatment and reentry programs.

Assignments are reevaluated on a regular basis and can change throughout people’s time in prison. For example, someone may begin their prison sentence with an assignment to adult basic education so that they can improve their literacy skills to help make future education or treatment programs more accessible to them. After completing adult basic education classes, they may choose to work in the prison laundry in order to earn money. Finally, as they approach their release date they may be assigned to a cognitive behavioral treatment program to address their identified need for anger management skills.

CDCR Planning to Convert Majority of Full‑Time Work Assignments to Half Time. CDCR is in the process of promulgating regulations to convert about three‑quarters of full‑time work assignments to half‑time assignments. The department indicates that this will create more flexibility in scheduling and allow people to participate in both work and education or treatment and reentry programs at the same time. In addition, because this change will mean that many people who currently have jobs in prison will spend less hours working, the regulations would increase wages for most jobs so that their total pay is not reduced. These changes are expected to go into effect in April 2024.

Prisons Subject to Court‑Ordered Population Limit. State‑owned and operated prisons are subject to a federal court order related to prison overcrowding that limits the total number of people they can house to 137.5 percent of their collective design capacity. Design capacity generally refers to the number of beds CDCR would operate if it housed only one person per cell and did not use bunk beds in dormitories. Currently, this means that the state is prohibited from housing more than a total of 103,853 people in state‑owned prisons. It also means that when prisons or yards are activated or deactivated, this population limit is increased or decreased by 137.5 percent of the design capacity of the affected prison or yard.

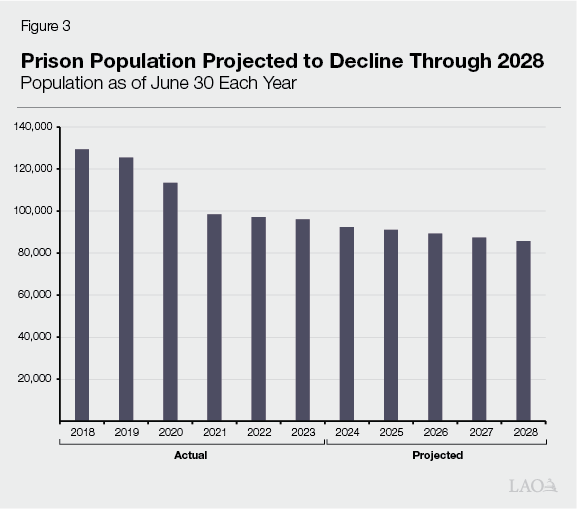

Prison Population Decline Allowing for Capacity Reductions. As shown in Figure 3, the prison population has declined significantly in recent years and is expected to remain low through June 2028. In 2021, CDCR completed a multiyear drawdown of people housed in contractor‑operated prisons made possible by the declining prison population. Since 2021, the administration has deactivated (1) two state‑owned prisons—the Deuel Vocational Institution (DVI) in Tracy and the California Correctional Center in Susanville, (2) eight yards at various state‑owned prisons, and (3) the California City Correctional Facility—a leased prison that was operated by CDCR staff. CDCR estimates that these deactivations resulted in ongoing General Fund savings totaling about $620 million annually. Deactivation also allowed the state to avoid funding infrastructure repairs that would otherwise have been needed to continue operating these facilities. For example, with the deactivation of DVI in Tracy, the state was able to avoid a water‑treatment project—estimated in 2018 to cost $32 million—that would have been necessary to comply with drinking water standards. The administration currently plans to deactivate Chuckawalla Valley State Prison (CVSP) in Blythe by March 2025.

Administration Has Cited Concerns With Further Capacity Reductions. Despite the above capacity reductions, CDCR projections have consistently showed that the population will remain well below the court‑ordered limit in future years. However, in response to suggestions that further capacity reductions should be considered, the administration has cited the following concerns:

- Increased Risk of Violating the Court‑Ordered Population Limit. Prison population projections are fairly uncertain in out‑years. If the state does reduce capacity but the population increases unexpectedly in the future, the administration is concerned that this could put the state at increased risk of violating the court‑ordered population limit.

- Increased Complexity in Housing Placement. As discussed above, CDCR typically clusters people with similar security, health care, or other needs in the same yard. Further capacity reductions would reduce the overall number of yards in operation. The administration is concerned that this could make it more challenging for CDCR to find appropriate housing placements, particularly for people with multiple complex needs.

- Reduction in the Number of Assignments. Further reductions in prison capacity would mean that, if use of the department’s remaining physical space and staffing levels remain unchanged, a smaller portion of the population would be able to have a full‑time or two half‑time assignments. This is because, in addition to reducing the number of beds in operation, capacity reductions remove physical space (such as classrooms or workshops) that is used for assignments. The administration argues such a reduction is a concern because assignments provide people in prison with a meaningful way to occupy their time. The administration also cites potential for a reduction in assignments to cause an increase in recidivism. This could occur if the reduction in assignments causes more people than otherwise to leave prison without having their assessed criminal risk factors addressed through effective interventions, such as treatment and reentry programs.

2023‑24 Budget Package Required Administration to Conduct Analysis of Prison Capacity Needs. In response to the above concerns cited by the administration, the 2023‑24 budget package added Penal Code Section (PC) 5033 to state law, which required CDCR to submit an assessment of its capacity needs by November 15, 2023 to help inform decisions related to further prison capacity reductions. PC 5033 states that it is the intent of the Legislature to deactivate additional prisons and that maintaining prison capacity beyond what is necessary for safety, operational flexibility, and to support rehabilitation is not cost effective. PC 5033 also directed the department to report, by prison, on the capacity needed to operate in a manner that is rehabilitative, safe, and cost efficient. In doing so, the statute specified CDCR shall include an assessment of available space for rehabilitative programming, health care services, specialized bed needs, space needed for quarantine or natural disasters, and space needed to comply with court requirements (such as the court‑ordered population limit).

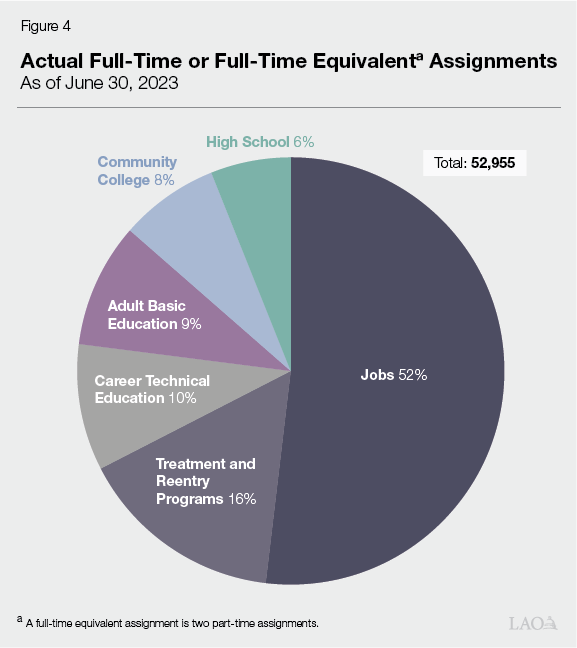

Analysis Inventoried Certain Types of Assignments. To prepare the report required by PC 5033, CDCR inventoried the number of full‑time and full‑time equivalent program and work assignments in operation at each prison as of June 30, 2023. (Two part‑time assignments were counted as one full‑time equivalent assignment.) As shown in Figure 4, these assignments include jobs, treatment and reentry programs, career technical education, adult basic education, community college, and high school equivalency courses. In total, CDCR identified 52,955 such assignments. We note that this does not include the 10,249 full‑time or full‑time equivalent assignments that on June 30, 2023 were budgeted but not in operation—such as due to an instructor vacancy or a classroom being under construction. In addition, the inventory did not include various other educational and/or rehabilitative activities that people may engage in while in prison, such as grant‑funded or volunteer‑led programs and college correspondence courses.

Analysis Calculated Percent of the Population That Can Receive Assignments. The analysis calculated, for each prison, the percent of the population that could have one of the above assignments if the prison were occupied at 120, 110, and 100 percent of its design capacity. This calculation was done with the following two different methodologies:

- Under the first methodology, the calculation only included the 52,955 assignments that were actually in operation on June 30, 2023. This methodology found that, if the prison system is occupied at 120 percent of design capacity, there would be enough assignments to serve 62 percent of its population based on the number of staff and classrooms in operation on June 30, 2023. In contrast, if the system was at 100 percent of design capacity, there would be enough assignments to serve 77 percent of its population on June 30, 2023.

- Under the second methodology, the calculation used budgeted assignment capacity instead of actual capacity as of June 30, 2023. Accordingly, it included the additional 10,249 full‑time or full‑time equivalent assignments that were budgeted but not in operation for various reasons (such as staff vacancies) as of June 30, 2023. This methodology found that if the prison system was occupied at 120 percent of its design capacity, there would be enough budgeted assignments to serve 74 percent of its population. In contrast, if the system was at 100 percent of its design capacity, there would be enough budgeted assignments to serve 91 percent of its population.

The report did not reach a conclusion about what percent of the population should have an assignment. We note that there could be various reasons why it would not be reasonable to maintain assignments for 100 percent of the population. For example, some people cannot participate in assignments due to age or health reasons.

Governor’s Proposal

Adjust Funding for Centralized Services to Account for Previous Capacity Reductions. The Governor’s budget reflects a reduction in 2024‑25 of $9.6 million from the General Fund and 57 positions (increasing to $11.1 million and 65 positions annually beginning in 2025‑26) to reflect reduced administrative support needs resulting from previous capacity reductions. For example, the reduction includes two positions in CDCR’s Office of Fiscal Services that are no longer needed to provide budget support to individual prisons as the total number of prisons has decreased.

Adjust CDCR Funding to Account for Planned Deactivation of CVSP. To reflect the planned deactivation of CVSP by March 2025, the Governor’s budget reflects a reduction in 2024‑25 of $33.2 million (largely from the General Fund) and 190.4 positions (increasing to $132.3 million and 743.2 positions annually beginning in 2025‑26).

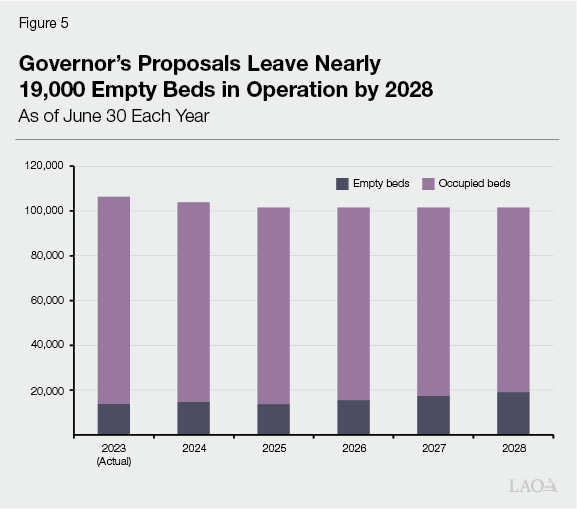

Continue Operating About 15,000 Empty Beds. The budget reflects operation of nearly 15,000 empty beds in 2024‑25. The department indicates that, while it intends to continue monitoring the issue, it is not planning further capacity reductions at this time.

Assessment

No Concerns With Adjustments Related to Previously Approved Deactivations. We have no concerns with the proposal to reflect savings for centralized services to account for previous deactivations. Similarly, we have no concerns with the proposal to reflect savings associated with the planned deactivation of CVSP by March 2025.

Number of Empty Prison Beds in Operation Projected to Grow to About 19,000 by 2028. As discussed above, the Governor’s proposals would leave about 15,000 empty beds in the near term. As shown in Figure 5, the projected long‑term decline in the prison population suggests that, after the proposed deactivations are completed, the state could have nearly 19,000 empty prison beds—comprising about one‑fifth of the state’s total prison capacity. This means that the state could be in a position to deactivate around five additional prisons by 2028 while still remaining roughly 2,500 people below the court‑ordered population limit.

Further Prison Capacity Reductions Would Create Significant Savings. Reducing the number of empty beds in operation by deactivating additional prisons or yards would allow for significant savings in three different areas:

- Prison Operational Costs. As the prison population declines, the state is able to spend less on certain things—such as food and clothing—that are directly tied to the number of people that need to be housed in state prisons. Specifically, the state saves roughly $15,000 per year each time one fewer person needs to be housed in a prison. These savings accrue as the population declines—regardless of whether prison capacity is reduced. However, there are many other types of costs—including most staffing costs—that are only saved when capacity is reduced. Specifically, when a whole prison is deactivated, the state can save several tens of thousands of dollars per capita annually in addition to the population‑driven savings. Per capita savings associated with yard deactivations are generally somewhat less than those associated with prison deactivations. This is because, while individual yard deactivations do allow staffing levels to be reduced, prisons have many centralized staffing costs—such as for administration and perimeter security—that must be maintained regardless of the number of yards in operation. As discussed above, after the planned deactivations, the state is projected to have enough excess capacity to allow for the deactivation of around five additional prisons. Deactivation of five prisons could generate nearly $1 billion in annual ongoing operational cost savings, depending on which prisons are deactivated.

- Prison Infrastructure Costs. As of January 2024, CDCR identified 44 deferred maintenance or capital outlay projects across 23 prisons at an estimated total cost of $2 billion that are expected to be needed over the next ten years. The majority of these projects are focused on issues related to safety (such as replacement of fire suppression systems) and critical infrastructure (such as kitchen renovations). Further capacity reductions would avoid the need to fund these projects at the prisons and/or yards that are deactivated.

- Staff Training Costs. CDCR’s staffing needs are affected by various factors, including the number of facilities being operated. Deactivating additional prison capacity would temporarily reduce the need for new correctional officers. This is because existing officers at the facilities that are deactivated would have the opportunity to fill vacancies throughout the prison system that would otherwise be filled by new officers. The Governor’s 2024‑25 budget maintains $140 million General Fund for CDCR to continue training new officers at the department’s 13‑week academy and delivering other training to existing officers. Accordingly, capacity reductions could allow the state to temporarily scale back these staff training costs.

These opportunities for savings are particularly notable given that the state is projected to face significant structural shortfalls—around $30 billion each year—in 2025‑26 through 2027‑28. Deactivating additional prison capacity would help the state avoid needing to reduce General Fund spending in other areas of the budget the Legislature prioritizes.

Administration’s Concerns With Further Capacity Reductions Could Be Mitigated. As discussed above, the administration has cited concerns with further reductions in prison capacity. However, we find that, with some advance planning and potential one‑time spending, these concerns could likely be mitigated as follows:

- State Can Take Steps to Reduce Risk of Violating Population Limit. As discussed above, the administration’s population projections indicate that the state could be in a position to deactivate around five additional prisons by 2028, while still maintaining a roughly 2,500 person “buffer” below the court‑ordered population limit. This would be the same size as the buffer typically maintained by CDCR prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic. (During the pandemic, the need for physical distancing in prisons temporarily necessitated a larger buffer.) This is notable because the population at that time was larger, meaning it was subject to potentially greater unexpected population swings. Nonetheless, the administration felt that a 2,500 person buffer was adequate. Moreover, in the event the population unexpectedly increases by more than 2,500 people, the state would have various options to avoid violating the population limit. For example, CDCR could contract with county jails to temporarily delay transfers of new prison commitments (according to data collected by the Board of State and Community Corrections, jails had a total population of about 59,700 in the first three quarters of 2023 and a total capacity of about 81,600); expand eligibility for people to be housed outside of state prisons, such as in conservation camps or community reentry facilities; and/or award credits in order to release certain people (such as those identified as posing a low risk to public safety) earlier than otherwise. We note that all of these steps have been used by CDCR in the past. If the unexpected increase in the population is sustained, CDCR could reactivate yards or prisons as deactivated state‑owned facilities are typically placed on “warm shutdown,” meaning they are still owned and being maintained by the state. Accordingly, deactivating prisons or yards and maintaining them on warm shutdown allows the state to save money on an annual basis without foreclosing the possibility of reactivating capacity if it is needed in the future.

- Housing Placement System and/or Infrastructure Could Be Modified to Increase Flexibility. To the extent that further capacity reductions would create challenges for CDCR in identifying appropriate housing placements, the department could consider changing housing placement policies to create more flexibility. CDCR has made such changes at various times in the past to accommodate shifts in population needs and reduce complexity. For example, CDCR recently promulgated regulations to consolidate its six types of restricted housing units into three types. (Restricted housing units can be used to temporarily house people as punishment for certain serious rule violations or who constitute a particular threat to prison security.) In addition, with advance planning, the department could build infill housing units at existing prisons and/or construct key infrastructure (such as specialized medical beds) to offset any losses in housing flexibility resulting from capacity reductions.

- Existing Assignment Infrastructure Could be Used More Effectively and/or More Assignments Could be Created. The state could mitigate the effect of capacity reductions on the number of assignments available by using its remaining assignment infrastructure more effectively. For example, as discussed above, vacancies and other and factors that prevent budgeted assignments from operating can substantially reduce the actual number of assignments available at a given time. Accordingly, CDCR could pursue strategies—such as recruitment efforts—to address these factors. In addition, CDCR could eliminate assignments associated with unproven or ineffective programs and use the freed‑up space to expand the number of assignments for programs known to be effective. Alternatively, the state could take steps to increase the number of assignments. For example, the state could create more assignments that do not require classrooms (such as gardening or activities done through tablets) or it could construct new classrooms.

While mitigating the administration’s concerns associated with capacity reductions could create some new costs for the state, these costs are largely temporary and would be far less than the nearly $1 billion dollars it would cost annually to operate around five prisons on an ongoing basis. Accordingly, we find that significant ongoing savings from pursuing further prison capacity reductions would likely far outweigh any costs associated with mitigating the potential negative effects of capacity reductions.

State Law Arguably Requires CDCR to Accommodate Population Declines Through Capacity Reductions. PC 2067 requires CDCR to accommodate projected population declines by reducing capacity in a manner that maximizes long‑term savings, leverages long‑term investments, and maintains sufficient flexibility to comply with the court‑ordered population limit. PC 2067 also requires CDCR to consider certain factors—such as operational cost and subpopulation‑specific housing needs—in determining how to reduce capacity. In view of the opportunity for significant savings and the possibility of mitigating negative effects on housing flexibility, PC 2067 arguably requires CDCR to further reduce capacity.

Recommendations

Direct CDCR to Deactivate Prisons. We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to begin planning to reduce capacity by the end of 2028. Deactivating whole prisons would create greater savings than deactivating yards at various prisons. We estimate that deactivating five prisons, for example, could allow the state to save nearly $1 billion in ongoing General Fund costs. This would not only help reduce the state’s structural budget shortfall in the years to come but would bring CDCR into compliance with PC 2067.

Direct CDCR to Report on Strategies to Mitigate Any Concerns. We recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to report by January 10, 2025 on (1) which specific prisons it plans to deactivate, (2) any specific concerns it identifies with these deactivations, as well as (3) strategies for and estimated costs of mitigating those concerns.

Direct CDCR to Plan for Reductions to Staff Training Costs. Deactivation of multiple prisons by 2028 would likely reduce CDCR’s need for new correctional officers over the period when the prisons are being deactivated. To ensure savings associated with this reduced need are captured, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to report by January 10, 2025 on (1) the projected impact of deactivations on its need for new correctional officers and (2) plans to scale back academy operations accordingly.

Approve Adjustments Related to Previously Approved Deactivations. We recommend the Legislature approve the proposed adjustments related to the previously approved deactivations, including the savings related to centralized services and the planned deactivation of CVSP by March 2025. This will help address the state’s budget problem in the budget and future years.

Voice Calling

Background

Various Ways for People in Prison to Communicate With Friends and Family. In addition to in‑person visiting and writing letters, there are various ways that people in prison can maintain contact with friends and family through electronic communication. These include voice calls, video calls, and electronic messages. Voice calls can be made from standard, hardwired telephones located at all prisons and portable tablet devices issued to each person. The department regulates the use of telephones and tablets among the prison population, such as the times of day when calls can be made.

CDCR Is Required to Provide Free Voice Calling to People in Prison. Chapter 827 of 2022 (SB 1008, Becker) specifies that CDCR shall provide accessible, functional voice calls free of charge. On January 1, 2023, CDCR began implementing this requirement by paying all charges accrued for voice calls. Though CDCR does not directly limit the number of minutes people can use, it does continue to restrict when calls can be made for operational reasons.

2023‑24 Budget Act Provided $28.5 Million General Fund Augmentation for Voice Calls. Based on calling data from January through March of 2023, CDCR estimated that about 93 million minutes would be used per month in 2023‑24. Based on this estimate, the budget included $28.5 million General Fund in 2023‑24 to pay for voice calls. This funding was authorized on an ongoing basis with the understanding that CDCR would adjust the level of funding for calling charges through the department’s biannual adjustment process. In addition, the budget act included provisional language allowing the Department of Finance (DOF) to augment or reduce this funding amount based on actual or estimated expenditure data.

Governor’s Proposal

$8.2 Million General Fund Augmentation in 2024‑25. CDCR reports that the prison population used about 119 million voice calling minutes in July 2023 and 125 million minutes in August. Based on the assumption that the August minute usage level will hold flat throughout the remainder of 2023‑24 and 2024‑25, CDCR estimates it will need an additional $7.4 million in the current year and $8.2 million in the budget year to pay for this higher than anticipated level of voice calling. CDCR will update these estimates at the May Revision based on additional months of actual calling usage data. To address any current‑year shortfall, the administration intends to use the authority provided by the provisional language in the 2023‑24 budget to augment the amount available for voice calls. To address the budget‑year shortfall, the Governor’s budget includes an $8.2 million General Fund augmentation, which would bring the total amount for voice calling to $36.7 million in 2024‑25. In addition, the proposed budget retains the provisional language allowing DOF to augment or reduce the funded amount after the budget is enacted.

Assessment

Funding Adjustment Methodology Does Not Account for Population Decline. As discussed above, the proposed $8.2 million augmentation in 2024‑25 assumes that the August 2023 calling level persists through June 2025. However, the prison population is projected to decline over this period. Specifically, on August 16, 2023, the population was about 95,700 and CDCR currently projects the average daily population in 2024‑25 to be about 91,700—a 4,000 (4 percent) person decline. Assuming that each person uses roughly the same number of calling minutes per month, the decline in the population will reduce the total number of minutes used. Accordingly, by not accounting for this population decline, the Governor’s budget likely over estimates the number of calling minutes and associated funding that will be used in 2024‑25.

Recommendations

Withhold Action and Direct CDCR to Update Methodology to Account for Population Changes. As discussed above, the administration plans to update its estimate of the 2024‑25 funding need at the May Revision based on additional months of actual calling usage. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature withhold action on the proposal until that time. Additionally, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to incorporate the effects of projected changes in the population into its methodology at the May Revision and in future biannual adjustments for voice calling costs. This methodology change would (1) help promote more accurate budgeting and (2) likely reduce the overall cost of the proposal in the budget year, freeing up General Fund resources that could be used to address the fiscal difficulties facing the state.

Utilities

Background

Utility Funding Currently Adjusted Based on California Consumer Price Index (CPI). CDCR facilities use various types of utilities such as natural gas, electricity, and water. The 2023‑24 budget provides about $140 million to pay for utilities. This funding level was established in 2022‑23 based on a three‑year average of CDCR’s actual utility expenditures and is updated annually through a technical adjustment using CPI. Prior to 2022‑23, utility funding was adjusted in proportion to increases or decreases in the prison population. However, this methodology was found to be inadequate after recent large declines in the population left CDCR underfunded for utilities.

Utility Prices Have Outpaced CPI. CDCR reports that while its utility usage has remained relatively constant, total costs have outpaced their funding level. This is because utility rate increases set by utility providers have generally outpaced CPI. The department currently projects a $44 million shortfall for utility costs in 2023‑24. It intends to pay for this shortfall using a combination of savings from staff vacancies and facility deactivations that occurred earlier in the current year than anticipated.

Governor’s Proposal

Adopt New Methodology for Adjusting CDCR Utility Funding. The Governor proposes to budget for CDCR’s utility costs based on actual prior expenditures through CDCR’s biannual adjustment process. Under the proposed methodology, the adjustment reflected in the Governor’s budget would be based on the prior fiscal year’s actual expenditures. The adjustment reflected in the May Revision would be based on expenditures from January through June of the prior fiscal year and July through December of the current year.

$22 million General Fund Augmentation for Increased Utility Costs. CDCR’s actual utility expenditures in 2022‑23 were about $184 million. As mentioned above, this is $44 million higher than the department’s current funding level of $140 million. Accordingly, under the proposed methodology, the Governor’s budget would reflect a $44 million increase relative to the enacted level. However, due to fiscal pressures currently facing the state, the administration is requesting $22 million, which is half of the anticipated need. Should actual 2024‑25 utilities costs surpass the budgeted amount, CDCR indicates that it would attempt to pay for the unfunded costs with savings in other areas of its budget, such as from staff vacancies, or request a supplemental appropriation if sufficient savings are not available.

Assessment

Proposed Augmentation and Methodology for Ongoing Adjustment Appear Reasonable. Given that utility prices are outpacing CPI, it appears that CDCR’s current methodology for adjusting its utility funding is not adequate. We find the administration’s proposal to adjust utility funding based on recent actual spending to be reasonable. We also find that making these adjustments through the biannual adjustment process will add transparency compared to adjusting funding through a technical adjustment as is currently done. In addition, while our office has recommended that the Legislature set a very high threshold for approving new spending, we find that the proposed $22 million augmentation meets this threshold. This is because utilities are closely linked to maintaining the health and safety of people who live and work in CDCR facilities.

If Actual Utility Costs Are Less Than Budgeted, Funding Could Be Redirected. If actual utility costs are lower than budgeted in a given year, the administration would be able to redirect the excess funding to other purposes. This is because CDCR’s utilities funding is budgeted in an item of appropriation that includes funding for various other purposes related to supporting the prison population.

Recommendations

Approve Proposal and Adopt Budget Provisional Language Limiting Use of Funding to Utilities. We recommend that the legislature approve the Governor’s proposed methodology and $22 million augmentation for utilities funding. However, to prevent potential excess funding from being redirected to other purposes, we recommend that the Legislature adopt budget provisional language to require any excess funding to revert to the General Fund.

COVID‑19 Health Care Costs

Background

COVID‑19 Had Major Impact on CDCR. Between the start of the pandemic and January 28, 2024, a total of about 96,000 COVID‑19 cases have been reported by CDCR as occurring within prisons. There have been 263 incarcerated people and 50 staff who have had COVID‑19‑related deaths. During this time period, CDCR implemented several restrictions and operational changes to reduce the spread of the virus within its institutions. For example, the department initially suspended visiting and rehabilitation programs, reduced the density of dormitories by housing some people in open areas (such as gymnasiums), and suspended nonurgent health care services. To reduce transmission, staff and people held in CDCR were generally required to be masked and regularly tested. However, some of these restrictions and changes are no longer in effect as the severity of the pandemic has abated. For example, the department has resumed visitation and rehabilitation operations and face coverings are generally optional in most areas of prisons.

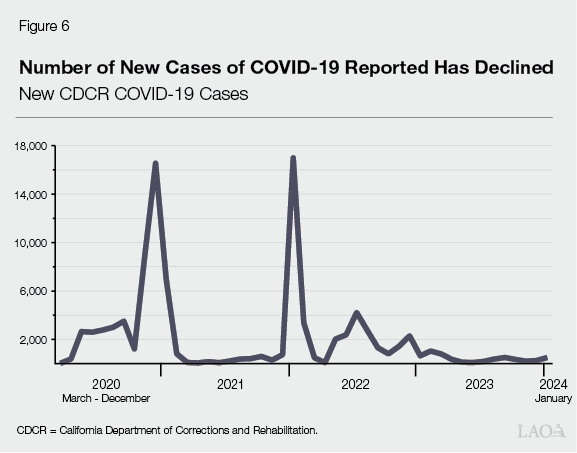

COVID‑19 Prevalence Down in Recent Years. According to data reported by CDCR, COVID‑19 continues to spread in prisons but at a lower rate than the initial years. Figure 6 shows CDCR’s reported number of new confirmed cases each month. As shown in the figure, new confirmed COVID‑19 cases have declined over time and the spikes in new cases observed annually in the months of December and January have also decreased in magnitude. For example, at its peak in the December to January period of 2020‑21, there were a total of about 23,500 new COVID‑19 cases compared to a total of about 500 new COVID‑19 cases reported in the December to January period of 2023‑24. The decrease in the prevalence of COVID‑19 in the prisons has resulted in reduced COVID‑19‑related workload. For example, January 2024 data shows that CDCR is testing about 400 people per week for COVID‑19, compared to about 3,600 per week in January 2023.

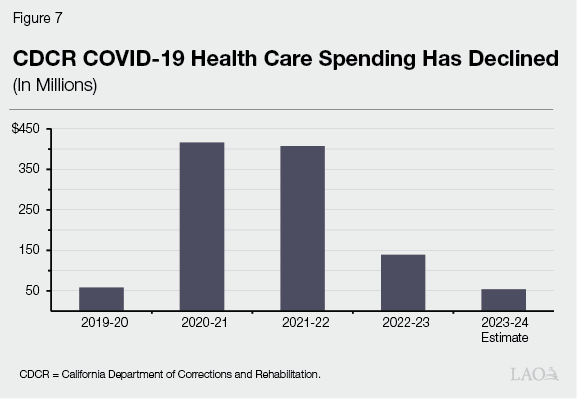

CDCR Spending on COVID‑19 Health Care Costs Declining. By the end of 2023‑24, CDCR expects to have spent a total of $1.1 billion since the beginning of the pandemic on COVID‑19 health care costs, including on testing, vaccinations, and cleaning. The majority of this amount occurred in the 2020‑21 ($416 million) and 2021‑22 ($407 million) budget years. (We note that a portion of these costs were supported by federal funding.) Figure 7 shows that, in subsequent years, COVID‑19‑related spending has declined significantly. For example, the 2023‑24 Budget Act provided $97 million one‑time from the General Fund for CDCR’s COVID‑19 response, of which the department estimates it will spend about $54 million.

Governor’s Proposal

$38 Million Ongoing for COVID‑19 Health Care Costs. The Governor’s budget proposes $38 million ongoing General Fund for CDCR COVID‑19 health care costs including testing, vaccination, staffing, treatment, and personal protective equipment. Figure 8 shows the requested level of funding for each activity. The requested level of funding is based on the average amount of expenditures the department has observed in certain months in 2023. For example, the department is requesting $20.6 million for statewide testing for staff ($7.4 million) and the prison population ($13.2 million). CDCR arrived at this estimate by adding the average expenditures on testing for staff between April 2023 and September 2023 and the prison population between April 2023 and August 2023 and assuming that the department would continue spending at that monthly rate in 2024‑25 and ongoing. CDCR applied a similar methodology for estimating its funding need for state response operations—which includes treatment, staff overtime costs, and wastewater testing—but used average expenditures from a different range of months in 2023. To estimate the funding needed for vaccines and personal protective equipment in 2024‑25 and ongoing, the department assumes it will spend the same amount it projects it will spend in the current year. In addition to the requested funding, the Governor’s budget proposes budget provisional language that would allow DOF to reduce CDCR’s funding for COVID‑19 health care costs based on actual or estimated expenditure data.

Figure 8

Proposed Level of Ongoing Funding

for CDCR COVID‑19 Response

|

Statewide testing |

$20,647,000 |

|

State response operationsa |

6,686,000 |

|

Vaccine distribution and administration |

6,253,000 |

|

Personal protective equipment |

4,802,000 |

|

Total |

$38,388,000 |

|

aIncludes treatment, staff overtime, and wastewater testing |

|

|

CDCR = California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. |

|

Assessment

Request Does Not Account for Recent Trends, Reflect a Standardized Methodology, or Projected Decline in Population. We find that the department’s proposed methodology to estimate its funding need does not factor in recent trends in COVID‑19 prevalence, is not based on a standardized methodology, and does not reflect projected declines in the prison population. For example, the department’s methodology to estimate its funding need for testing of the prison population factors in expenditures between April 2023 and August 2023. As a result, CDCR’s ongoing level of resources for testing of the prison population would be based on trends that do not reflect more recently available information given that CDCR indicates it will not update its request in the spring. This budgeting approach raises further concerns because it is not standardized to include the same months in the calculations for each of the expenditure categories. For example, it is unclear why the ongoing level of funding for testing of the prison population should be based on average expenditures between April 2023 and August 2023, while the funding for testing of staff should be based on average expenditures between April 2023 and September 2023. Moreover, the proposal assumes CDCR expenditures on COVID‑19 health care costs will remain the same despite the fact that the prison population is projected to decline both in 2024‑25 and future years, suggesting the department’s resource need will also decline going forward.

CDCR Has Not Explored Options to Reduce State Spending by Leveraging Employee Health Insurance. The state offers employer‑sponsored health insurance to state employees, including CDCR. As such, CDCR staff are able to receive vaccinations against COVID‑19 from their employer‑sponsored health insurance. Notably, all employer‑sponsored health insurance plans offered through the state provide COVID‑19 vaccinations at no‑cost to the employee. When asked whether the department could leverage employee health insurance to offset the vaccine costs for employees, CDCR indicated that it had not explored such an option. This is noteworthy given that the department is requesting resources for staff vaccinations against COVID‑19 on an ongoing basis.

Recommendations

Withhold Action on Budget‑Year Request and Direct CDCR to Provide Updated Proposal. We recommend that the Legislature withhold action on the Governor’s proposed resources for COVID‑19‑related health care costs in CDCR in 2024‑25. We also recommend the Legislature direct the department to update its 2024‑25 request in the spring to reflect more recent data. In doing so, the department should use a standard snapshot of months when calculating its need for each of the activities it is requesting resources for and provide justification for why that set of months is reflective of its costs. Additionally, the department should adjust the proposal to reflect the fact that the prison population is expected to decline between 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. Finally, we recommend the Legislature direct CDCR to explore options to leverage the state’s employer‑sponsored health insurance to reduce the funding needed for employee vaccines and further adjust the proposal as necessary to reflect any resulting savings from doing so. These adjustments would likely reduce the overall cost of the proposal, freeing up General Fund resources that could be used to address the fiscal difficulties facing the state in the budget year.

Reject Funding for Future Years. We recommend that the Legislature reject the funding proposed for the future and fund the department’s COVID‑19‑related health care workload on a one‑time basis. The department has provided little reason to think that its COVID‑19‑related funding needs will remain at 2023 levels in the future, particularly given the projected decline in the prison population. Moreover, funding such a request would increase the department’s baseline spending in the future, and we find that it is not prudent to make such a commitment given the fact that our office projects the state’s fiscal difficulties will continue in future years.

Prison Medical Care Budget Shortfall

Background

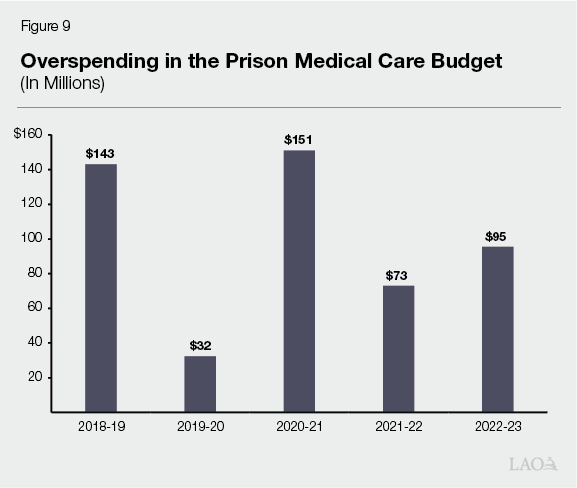

Department Consistently Overspends Prison Medical Care Budget. Since 2018‑19, CDCR reports that it has exceeded its General Fund prison medical care budget by tens of millions of dollars to hundreds of millions of dollars annually, as shown in Figure 9. According to the department, this shortfall is the result of overspending on personnel‑related expenditures. Specifically, the department cites costs related to vacancies including spending on overtime for staff that must complete workload associated with vacant positions and registry (contractors that provide services on an hourly basis when civil servants are unavailable). The department also cites costs related to workers’ compensation claims and lump sum payouts (payments made to employees to compensate them for unused leave when they leave state service) as contributing to the overspending in the prison medical care budget.

Department Has Addressed Overspending Without Additional Funding. CDCR indicates that it has been able to address the overspending in the prison medical care budget in previous years without requiring additional funding. According to the department, it has been able to redirect savings from vacancies elsewhere in the CDCR budget, including from mental health services, to cover the overspending in the prison medical care budget.

Governor’s Proposal

$40 Million One Time to Cover Projected Overspending in the Prison Medical Care Budget. The Governor’s budget proposes a $40 million one‑time General Fund augmentation in 2024‑25 to cover projected overspending in the prison medical care budget. The department indicates that personnel‑related cost pressures will continue in the budget year and that the savings used to offset the overspending in previous years will no longer be available. We note that the department estimates that it will not overspend the prison medical care budget in the current year.

Assessment

Unclear Why Department Needs Additional Funding to Address Potential Overspending. In recent budget years, CDCR has been able to address its overspending in the prison medical care budget within its existing budget authority by using savings elsewhere in its budget. The department has not provided any information on why redirected savings will not be available to do so in the budget year. Moreover, to the extent that the department does overspend in the prison medical care budget during the budget year and cannot redirect savings to address it, the department can seek additional funding through Item 9840‑001‑0001 in the Governor’s proposed budget. Specifically, Item 9840‑001‑0001 includes $55 million to augment departments’ General Fund budgets upon approval of the Director of DOF no sooner than 30 days after notification to the Joint Legislative Budget Committee. In the event that this $55 million is used for other contingencies and is unavailable to support the prison medical care budget, we note that Item 9840‑001‑0001 outlines a process through which the administration can request a supplemental appropriation to address these costs.

Inadequate Justification Provided for $40 Million. CDCR has not provided sufficient data supporting its need for the requested $40 million. For example, the department has not provided a back‑up calculation showing how it projected that $40 million in overspending would occur. As a result, it is difficult for the Legislature to assess whether this is a reasonable estimate, particularly because there is no discernable pattern in the department’s overspending in previous years. In addition, the fact that the department does not expect to overspend its prison medical care budget in the current year raises questions about why it expects to do so in the budget year. This lack of justification is particularly notable given that the state is currently facing a budget problem. Accordingly, proposals for new spending should meet a higher threshold before being approved. Given the lack of justification, the proposal does not meet this higher threshold in our view.

Recommendation

Reject. We recommend that the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal. We find that the proposal does not make it clear why CDCR needs additional funding to address potential overspending in the prison medical care budget and cannot redirect funding from elsewhere in its budget as it has done previously. Moreover, even if overspending cannot be addressed by redirecting funding, the department can seek additional funding through Item 9840‑001‑0001 or a supplemental appropriation. Finally, the proposal does not provide adequate justification for the requested $40 million, particularly given the budget problem facing the state. We note that rejecting this proposal will help the state address its budget problem.

Contract Medical Services

Background

CDCR Uses Contract Medical Services When Health Care Needs Cannot Be Met. When CDCR is unable to provide necessary medical services to people held in prison because it lacks the needed equipment or specialist providers, the department contracts for these services with external providers. These contract medical services are used in a number of circumstances ranging from trips to emergency departments for physical injuries to chronic medical issues that require specialized treatment. In some cases, providers are brought into facilities to deliver treatment. However, in many cases, people are transported out of a prison to receive care in the community, including inpatient care. Each time CDCR uses contract medical services, the department is charged the full medical costs plus a $19 fee for administrative claims related to processing a CDCR patient through a community specialty care provider network. CDCR pays for most contract medical services from the General Fund. However, in specific circumstances, such as when an eligible person receives services outside of prison for more than 24 hours, the department may offset a portion of these costs with federal reimbursements. These federal reimbursements are provided through Medi‑Cal, a program partially funded by the federal government that covers health care costs for low‑income people and families, including certain costs for eligible people in prison.

CDCR Contracts With Medical Providers to House People on Medical Parole. The medical parole program within CDCR allows medically incapacitated people to be placed in licensed health care facilities that the department contracts with in the community instead of prison. To be eligible for medical parole, various criteria must be met. For example, CDCR medical staff must determine the person is permanently medically incapacitated and the Board of Parole Hearings must determine that the person does not reasonably pose a threat to public safety. Once in the community, CDCR parole agents and medical staff monitor patients. In the event a patient shows significant improvements in their medical condition, the patient can be returned to prison. The department reports that, due to restrictions on the type of facilities it places patients in, it is unable to qualify for federal reimbursement through Medi‑Cal for the care provided to people on medical parole. As a result, the department pays for the cost of treating each patient—about $261,000 annually—entirely from the General Fund contract medical services budget. According to the department, there have been an average of 50 people on medical parole in the past three budget years and it has spent an average of $13 million annually on the program.

CDCR Reports Budgeting Methodology Does Not Accurately Reflect Costs. Through the biannual adjustment process, CDCR is typically budgeted for contract medical services based on the (1) size of prison population, (2) a fixed rate of $2,763 per person, and (3) a set amount of $54 million ongoing in federal reimbursement authority. For example, in 2023‑24, this budgeting methodology would have resulted in the department receiving about $337 million for contract medical services, including $282 million from the General Fund and $54 million in federal reimbursement authority. However, the department raised concerns that this methodology did not accurately reflect its costs for various reasons. First, CDCR reports that a decline in the prison population has led to reductions in the amount being budgeted for contract medical services. However, the department has not observed corresponding reductions in the number of people in its three highest medical risk categories (High‑1, High‑2, and Medium) who are more likely to use contract medical services. This is because the population reduction disproportionately occurred among people in the Low medical risk category. Furthermore, CDCR reports that the $2,763 per person fixed rate—which was established in 2012—is insufficient because it does not fully reflect the costs of medical parole or the $19 administrative claims fees. Finally, the department indicates it has been receiving less in federal reimbursements than reflected in the budget in recent years. To temporarily address these issues, the 2023‑24 budget provided CDCR with a one‑time General Fund augmentation of $40 million and a one‑time federal reimbursement authority reduction of $12 million, bringing the total budget for contract medical services to about $364 million.

Governor’s Proposal

$3.9 Million Current‑Year Augmentation Based on Existing Budgeting Methodology. The department is projecting that the prison population in the current year will be larger than was assumed in the enacted 2023‑24 budget. Accordingly, the Governor proposes a $3.9 million General Fund augmentation to the contract medical services budget based on the current budgeting methodology used in the biannual adjustment process. This would increase the budget from about $364 million to $368 million. Given the weaknesses in the methodology described above, CDCR indicates that this methodology would likely not fully fund the department’s contract medical service need for 2023‑24. However, CDCR is not requesting additional resources beyond the $3.9 million proposed in the current year. This is because the $40 million one‑time augmentation that the department received in the 2023‑24 Budget Act should minimize its need for such additional resources.

$24 Million Budget‑Year Augmentation Based on New Budgeting Methodology. The department is projecting a decline in the prison population in the budget year that would result in a $3.4 million reduction to CDCR’s contract medical services budget under the current methodology. However, the Governor proposes four changes to the budgeting methodology used in the biannual adjustment process that would result in a net increase of $24 million for contract medical services in 2024‑25. This reflects a $36 million General Fund augmentation and a $12 million decrease in federal reimbursement authority. This change is the result of the following:

- $8.2 Million General Fund Tied to New Budgeting Methodology Based on Medical Risk. First, the department is proposing to replace the fixed per‑person rate of $2,763 with a per‑person rate for each medical risk category. Specifically, the department would receive $21,168 for each High‑Risk 1 person, $6,323 for each High‑Risk 2 person, $2,230 for each Medium‑Risk person, and $1,009 for each Low‑Risk person. These amounts were calculated using a five‑year average of per‑person expenditures for each medical risk category. This funding would be adjusted biannually based on the size and medical risk of the prison population.

- $13 Million General Fund for Medical Parole Based on Medical Parole Population. The department is also proposing that it be funded for medical parole separately based on projections of the medical parole population. Under the proposed methodology, the department would receive $261,356 for every person expected to be on medical parole. The amount per person was calculated based on a three‑year average of expenses for the people on medical parole. In the budget year, the department projects 50 people will be on medical parole. This funding would be adjusted biannually based on the size of the medical parole population.

- $15 Million General Fund for Administrative Claims Fees. In addition, the budget includes funding to support the cost of administrative claims fees. Under the proposal, the department would receive ongoing funding for the $19 administrative claims fees associated with each contract medical service used. CDCR projects that it will use 800,000 contract medical services per year in the budget year and future years. This amount would not be adjusted biannually.

- $12 Million Reduction in Federal Reimbursement Authority. Lastly, the department is requesting that its federal reimbursement budget authority be reduced by $12 million on an ongoing basis. The Governor’s proposal would reduce the department’s federal reimbursement authority to $42 million, which it reports is more aligned with the actual level of federal reimbursements it is currently receiving. This amount would not be adjusted biannually.

Assessment

No Concerns With Proposed Current‑Year Funding Level. We do not raise any concerns with the proposed $3.9 million General Fund augmentation to the contract medical services budget based on the current budgeting methodology in 2023‑24. We acknowledge that the weaknesses in the current methodology could result in the department receiving insufficient funds for contract medical services. However, the $40 million in one‑time funding provided as part of the 2023‑24 Budget Act should minimize the extent to which this occurs.

Some Proposed Budget‑Year Changes to Funding and Methodology Appear Reasonable… We find that the proposed methodologies used to arrive at the $8.2 million General Fund requested based on the medical risk of the prison population and the $13 million General Fund requested for medical parole appear reasonable and would better align the department’s budget with its actual needs for those services. Moreover, because this improved methodology would be part of the biannual adjustment process, it would ensure the contract medical services budget remains tailored to the department’s needs going forward as the size and makeup of the prison population changes.

…Except Administrative Claims Funding and Federal Reimbursement Authority, Which Would Not Be Adjusted for Population Changes. We find that the Governor’s proposed funding methodology for administrative claims and federal reimbursement authority is lacking because it would not change based on changes in the size or makeup of the prison population. For example, the department would continue to receive $15 million General Fund to pay for 800,000 administrative claim fees and $42 million in federal reimbursement authority each year despite the fact that the prison population is expected to decrease in future years. This is problematic as the total number of contract medical claims will also likely decrease below 800,000, meaning the department will have more funding than it needs for these claims. Similarly, the department’s federal reimbursement authority could provide it with more funding than it will be able to qualify for as the population declines. (We note that adjusting the department’s reimbursement authority downward to account for reductions in the prison population would not exempt it from statutory requirements to maximize federal reimbursements.) Moreover, the methodology for these aspects of the contract medical services budget is inconsistent with the population‑driven methodology proposed for the other portions of the budget.

Recommendations

Withhold Action and Direct CDCR to Develop Population‑Based Budgeting Methodology for Federal Reimbursements and Administrative Claims. We recommend the Legislature withhold action on this proposal until it is adjusted based on updated population projections as part of the biannual adjustment process at the May Revision. In addition, given that the $15 million for administrative claims fees and the $42 million in reimbursement authority is not population‑driven, we recommend that the Legislature direct CDCR to develop a new methodology for those aspects of the contract medical services budget that account for changes in the size and/or makeup of the prison population. This revised proposal could be considered by the Legislature at the May Revision. Given that the state is currently facing a budget problem, we note that the Legislature will need to weigh any potential increase in spending related to this proposal against its other spending priorities as it will likely need to offset cost increases with spending reductions elsewhere in the budget. Accordingly, proposals for new spending should meet a high threshold before being approved.

Parole Support Staffing

Background

Division of Adult Parole Operations (DAPO) Employs Support Staff. In order to assist the work that parole agents do in the field, DAPO—within CDCR—employs various support staff that do not involve the direct supervision of people on parole—such as human resources analysts and office technicians. Some of these parole support staff are located at headquarters in Sacramento, while others are located across the state in one of DAPO’s 2 regional offices or 47 field offices.

Budget for Parole Support Staff Biannually Adjusted Based on Changes in Parole Population. Since the 2019‑20 fiscal year, CDCR has budgeted for parole support staff through the biannual adjustment process based on changes in the parole population. This is because, similar to most other parole positions, the need for many parole support positions is driven by changes in the parole population. For example, if the parole population increases, there is an increased need for parole supervision staff (which includes parole agents and their supervisors). This creates a greater need for parole support staff, such as human resource analysts, to process a potential increase in the number of workers’ compensation claims resulting from the additional parole supervision staff. Conversely, if the parole population declines, CDCR needs fewer parole support staff due to the decline in the number of parole supervision staff. Under the current methodology, an increase or decrease of about 5,000 in the parole population would result in a corresponding increase or decrease of about 11 parole support staff positions and about $1.4 million in funding. In the 2023‑24 Budget Act, CDCR received about $13 million and 99 parole support staff positions based on this budgeting methodology.

Department Has Raised Concerns About Reduction in Parole Support Staff Caused by Parole Population Declines. The parole population declined annually between 2020‑21—when the average daily parole population was 54,900—and 2022‑23—when it was 39,200. Moreover, the average daily parole populations is projected to continue to decline to 36,500 in the current year and 35,500 in the budget year and remain near this level in future years. As a result, the number of parole support staff is also declining. However, CDCR indicates that further decreases in the parole support staff budget and positions would be problematic. This is because CDCR reports that there are support staff positions that are eliminated when the population declines under the current methodology despite the fact that the workload for these positions is not decreasing. For example, the workload for support staff needed to manage statewide contracts required for various parole‑related services remains the same even when the parole population declines. CDCR reports that further reduction to these positions will mean it is unable to fully address such workload.

Governor’s Proposal

New Proposed Budgeting Methodology for Parole Support Staff. The department is projecting a continued decline in the parole population that would result in reductions to CDCR’s parole support staff positions and budget under the existing budgeting methodology. Specifically, it would result in about $200,000 less funding and 1.5 fewer positions in the current year and about $430,000 less funding and 4 fewer positions in the budget year. However, the department proposes to change the budgeting methodology beginning in the budget year for parole support staff given its concerns about further reductions to these positions. Under the proposed methodology, no downward or upward adjustments would be made to the parole support staff budget or positions when the parole population is below 42,222. This would roughly maintain parole support staff at existing levels in the budget year and onward because the parole population is projected to remain below 42,222 people during this time period. If the parole population were to increase in the future above 42,222, then the budget for support staff would once again increase under the proposed methodology, but would do so based on new ratios that would budget for slightly more support staff than under the current methodology. Specifically, every increase of 5,000 people on parole—over 42,222—would generate about 12 additional support staff and about $1.5 million in funding.

Assessment

While Existing Budgeting Methodology Needs Revision… We find that the existing budgeting methodology for parole support staff requires a revision. We agree with the department that there is some workload among support staff that does not change as the parole population increases or decreases, such as the managing of statewide contracts required for various parole‑related services. Accordingly, the current methodology is flawed and could lead to underbudgeting for some workload as the parole population continues to decline.

…Proposed Methodology Is Also Flawed. However, we find that the Governor’s proposed methodology for budgeting for parole support staff would continue to create a mismatch between the level of resources the department needs and the amount it is budgeted for. Specifically, under the Governor’s proposal, if the parole population decreases further, the department would retain its funding for parole support staff whose workload declines as the population shrinks. Similarly, if the population increases, then CDCR would receive additional funding for parole support staff whose workload does not increase with growth in the population. In either scenario, the methodology would result in the department being overbudgeted.

Recommendations

Reject. We recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal. We agree with the department that the existing methodology needs revision to account for some workload among parole support staff that does not change as the parole population changes. However, the proposed methodology is also flawed. It not only fails to properly account for workload that does not change when the parole population changes but also fails to account for workload that does change with changes in the parole population.