LAO Contact

Update (3/1/24): Figure 6 updated to correct number of districts that are between one and ten times the district's ADA.

February 29, 2024

Review of the Funding Determination Process for Nonclassroom-Based Charter Schools

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Background

- Analysis of Funding Determination Process

- Analysis of Other Charter School Oversight Issues

- Conclusion

Executive Summary

Background

Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools Must Submit Funding Determination Requests to the California Department of Education (CDE). State law classifies charter schools as nonclassroom‑based if more than 20 percent of instructional time is offered through means that are outside of an in‑person classroom setting. To generate funding for its nonclassroom‑based attendance, the school must submit a funding determination request to the state using data from the prior year.

Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools Must Meet Three Criteria to Receive “Full” Funding. In order to be eligible to receive full funding for its nonclassroom‑based attendance, a nonclassroom‑based charter school must meet three criteria: (1) spend 40 percent of annual revenue on certificated staff compensation, (2) spend 80 percent of annual revenue on instruction and related activities, and (3) maintain a student‑to‑teacher ratio of 25‑to‑1 in most cases. If a school does not meet these thresholds, they would receive a prorated amount (typically either 85 percent or 70 percent).

State Law Requires Evaluation of Process Used to Determine Funding for Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools. Chapter 48 of 2023 (SB 114, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) requires the Legislative Analyst’s Office and the Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team to study the funding determination process for nonclassroom‑based charter schools and report their findings by March 1, 2024. The statute specifies that this study shall “identify and make recommendations on potential improvements to the [process], including recommendations for enhancing oversight and reducing fraud, waste, and abuse.”

Findings and Assessment

“Nonclassroom‑Based” Term Is a Misnomer. In 2023‑24, 204 nonclassroom‑based charter schools reported they offer no virtual instruction or are primarily a classroom‑based program. These schools represent half of the statewide attendance at nonclassroom‑based charter schools. In our conversations with nonclassroom‑based charter schools, many indicated they offer different types of educational programs (primarily in‑person, blended, or primarily virtual) that students can choose from. Some indicated they preferred the nonclassroom‑based designation because of the flexibility they had in deciding how to serve each student. For these schools, the term nonclassroom‑based does not necessarily reflect the experience of students enrolled in their programs. These schools also often have a cost structure that is similar to traditional brick‑and‑mortar schools.

Funding Determination Process Has Gaps. The funding determination process also has several gaps that make it less effective in monitoring school spending. Most notably, nonclassroom‑based charter schools usually are only required to submit one out of every four years of expenditure data, which limits the state’s ability to comprehensively assess their spending patterns. Additionally, CDE does not have the capacity to verify the accuracy of the various data submitted that is self‑certified.

Current Process Is Not an Effective Way to Address Other Concerns With Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools. The funding determination process can be a helpful tool to monitor the overall cost structure of a nonclassroom‑based charter school and to ensure funding is being spent on staffing and other services that benefit students. The process, however, is not an effective approach for ensuring that charter schools are complying with other state laws. Given the funding determination process is based on the review of audited expenditures and attendance data, it relies on other aspects of the system to be working effectively. These other aspects of oversight—such as annual audit requirements and oversight from authorizers, county superintendents, and the state—are more appropriate ways to monitor these issues.

Recommendations

Recommend Several Changes to Improve Funding Determination Process. We provide several specific recommendations the Legislature could enact to improve the funding determination process. Our recommendations are intended to narrow the process to a smaller subset of schools, improve the comprehensiveness and quality of data submitted to CDE, and streamline some aspects of the process. Most significantly, we recommend the Legislature:

- Narrow the Definition of a Nonclassroom‑Based Charter School. We recommend narrowing the definition of a nonclassroom‑based charter school so that the designation excludes those schools that provide the majority of their instruction in person. This would exclude charter schools whose programs have cost structures that are similar to traditional classroom‑based programs.

- Improve Quality of Data Submitted to CDE. To assist CDE in efficiently reviewing and processing funding determination forms, we recommend requiring data submitted by charter schools be consistent with their annual audits. We also recommend several changes that would require information submitted to CDE be subject to annual audits.

- Use Multiple Years of Data for Funding Determinations. We recommend the funding determinations take into consideration a school’s aggregate spending for all years since the previous funding determination. This would ensure school expenditures are aligned with the funding determination thresholds consistently over time.

Consider Changes to Charter School Oversight. We also provide several recommendations for the Legislature to consider regarding broader oversight of charter schools. These issues generally apply to all charter schools, though in a few cases we highlight specific issues related to nonclassroom‑based charter schools and virtual charter schools. Most significantly, we recommend the Legislature consider the following:

- Improvements to Oversight by Charter School Authorizers. We recommend the Legislature consider several changes to improve the quality of authorizer oversight. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature set limits on district authorizers by district size and grade, increase minimum requirements for authorizers, and consider an alternative authorizing structure for virtual schools.

- Enhancements to Charter School Audits. Current audit requirements often do not address the complexities and unique flexibilities of charter school finances. We recommend the Legislature align the audit process for charter schools to that of school districts and add audit requirements that would address issues specific to charter schools.

Introduction

State Provides Flexibility Over Instructional Approaches. Under current law, charter schools and school districts have flexibility to provide instruction in a variety of settings. Although school districts are required to operate traditional in‑person instruction, they also have the option of additionally operating independent study programs which can take on many different forms that range from fully online virtual academies to hybrid programs that combine on‑site and off‑site instruction. Charter schools have more flexibility in structuring their programs as they are not required to provide in‑person instruction.

State Classifies Some Charter Schools as Nonclassroom‑Based. State law classifies charter schools as either classroom‑based or nonclassroom‑based. Specifically, a school is nonclassroom‑based if more than 20 percent of instructional time is offered through means that are outside of an in‑person classroom setting. In 2022‑23, 313 schools (25 percent of all charter schools) were nonclassroom‑based. These schools accounted for 38 percent of statewide charter school attendance that year.

State Law Requires Additional Scrutiny Over Funding for Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools. Chapter 892 of 2001 (SB 740, O’Connell) required the State Board of Education (SBE) to establish a system for determining the appropriate funding level for nonclassroom‑based charter schools that, at a minimum, considers the percentage of total expenditures for certificated staff salaries and benefits and the school’s student‑to‑teacher ratio. The state board adopted thresholds for these criteria, and also required that funding determinations be based on the percentage of total expenditures for instruction and related services.

State Law Requires Evaluation of Processes Used to Determine Funding for Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools. Chapter 48 of 2023 (SB 114, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) requires the Legislative Analyst’s Office and the Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team to study the processes used to determine funding for nonclassroom‑based charter schools and report their findings by March 1, 2024. The statute specifies that this study shall “identify and make recommendations on potential improvements to the [funding determination] processes, including recommendations for enhancing oversight and reducing fraud, waste, and abuse.”

Report Has Three Main Sections. This report responds to the statutory requirement. The first section provides a brief overview of charter schools and outlines the main features of the funding determination process. The second section describes our findings, assessment, and recommendations specifically related to the funding determination process. The final section describes our assessment and recommendations related to broader issues of oversight for charter schools.

Background

In this section, we provide a brief overview of charter schools and how they are funded, as well as how charter schools are classified as nonclassroom‑based. We then discuss the funding determination process used to determine the level of funding for these schools.

Charter Schools

California Established Charter Schools in 1992. Charter schools are publicly funded elementary and secondary schools operating under locally developed agreements (or “charters”) that describe their educational programs. The state created charter schools to offer parents or guardians an alternative to traditional public schools and encourage local leaders to explore innovative educational programs. All charter schools must provide nonsectarian instruction, charge no tuition, and admit all interested California students up to school capacity. If the charter school receives more student applications than they have capacity to enroll, the school must implement a lottery system.

Charter Schools Are Held Accountable to Their Local Charter. To both be established and renewed, a charter school in California must have an approved charter that sets forth a comprehensive vision for the school, including its educational program, student discipline policy, employee policies, governance structure, and fiscal plans. Charter schools are exempt from many state laws and regulations that apply to school districts. For example, they are not required to collectively bargain with employees or select members of their governing board through local elections.

Interested Groups Initiate Petition Process. Charter school petitions must set forth a comprehensive vision for the school, including its educational program, student discipline policy, employee policies, governance structure, and fiscal plans. Petitions must be signed by at least half of the number of parents or guardians of students that the charter school estimates will enroll in the school for its first year of operation or by half of the number of teachers that the charter school estimates will be employed at the school during its first year of operation.

Charter Schools Must Be Authorized by a School District or County Office of Education (COE). Every charter school has an authorizer that is responsible for approving the school’s charter. In most cases, an interested group looking to establish a charter submits its petition to the local governing board of the school district where the charter school will be located. In 2023‑24, districts authorize 83 percent of active charter schools. Under certain conditions, a group may submit a petition to the governing board of the COE, such as a charter school that is seeking to serve students from across the county. Initial authorization may be for a period of up to five years. The authorizer monitors the charter school and may deny a renewal if the school does not adhere to the terms of its charter, performs poorly on state measures of academic performance, or violates the law. (An authorizer can also revoke a charter in certain circumstances.)

Under Certain Conditions, an Authorizer Can Reject a Petition. State law specifies that school districts can deny the approval of a new charter petition for one of eight specific circumstances. Most notably, petitions may be denied if the proposed educational program is unsound, the charter school would undermine or be duplicative of existing programs currently offered by the authorizer, or the establishment of the charter would fiscally impact the authorizer to the point they would be unable to meet their financial obligations. If a school district denies a charter petition, the interested groups can appeal the denial with the COE in which the school district operates. In this case, a COE will review the charter petition and the statement from the school district on why they denied the petition. COEs in this case conduct their own review of the charter petition and may authorize the charter if they disagree with the district’s assessment. Appeals may also be filed with SBE, though their level of review depends on whether or not the charter petition was denied by both the school district and COE, or just the school district. If SBE approves a petition on appeal, they must designate whether the chartering authority will be granted to the school district or COE in which the charter will operate. As described in the nearby box, the state recently enacted various changes to rules related to authorization and oversight of charter schools.

Recent Legislation Impacting Charter School Authorization and Oversight

Since 2019, the state has enacted several changes that have impacted the authorization and oversight of charter schools. Below, we describe three bills that made significant changes specifically related to charter schools.

Chapter 486 of 2019 (AB 1505, O’Donnell). Assembly Bill 1505 included several changes to laws regarding charter schools. Most notably, the bill made changes in four areas:

- Additional Circumstances for Denying a Petition. This legislation added two circumstances under which an authorizer can deny a charter petition for the establishment of a new charter school (providing authorizers with a total of eight circumstances for denying a petition). Specifically, AB 1505 now allows an authorizer to deny a petition if (1) the charter school would undermine or be duplicative of existing programs currently offered by the authorizer, or (2) the establishment of the charter would fiscally impact the authorizer to the point they would be unable to meet their financial obligations.

- Delegation of Oversight for Charter Schools Authorized by the State Board of Education (SBE). Assembly Bill 1505 removed SBE’s authority to approve statewide benefit charter schools and required SBE to delegate oversight of charter schools to school districts and county offices of education (COEs). Charter schools previously authorized by SBE are now required to renew their charter with the school district or COE in which they operate. Additionally, when SBE approves a charter on appeal, they must designate, in consultation with the charter school, whether the school district or COE in which the charter operates will provide oversight.

- Change to SBE’s Approach to Some Appeals. Prior to AB 1505, SBE reviewed appeals for new charter schools by conducting its own independent review of the charter petition, similar to that of school districts and COEs. Under AB 1505, if the charter petition was denied by a school district and a COE, then SBE only evaluates whether the school district or COE may have abused its discretion—SBE does not conduct an independent review of the charter petition. SBE must conduct their own independent review of appeals for new charter schools in single‑district counties. SBE also must conduct their own independent review of appeals for renewal related to schools that were previously authorized by SBE.

- Renewals of Existing Charter Schools Tied to Performance. Assembly Bill 1505 required charter authorizers to consider the charter school’s performance on the indicators included in the California School Dashboard when evaluating a petition to renew a charter school. The legislation establishes three tiers of performance based on the School Dashboard indicators. These tiers must be used to determine whether the charter will be renewed and to determine the length of a charter renewal. For schools not in the highest performance tier, the authorizer must consider certain verified data related to year‑to‑year growth in student academic achievement and postsecondary outcomes (in addition to indicators on the School Dashboard).

Chapter 487 of 2019 (AB 1507, O’Donnell). Prior to AB 1507, charter schools could operate facilities outside of their authorizing school district in certain circumstances, as well as operate a resource center in an adjacent county. Assembly Bill 1507 prohibits new charter schools from operating facilities outside of their authorizing school district. As part of their renewal process, charter schools that were already operating outside of their authorizing school district were required to obtain approval from the district where their site or resource center is located. Alternatively, charter schools were also able to renew their charter with the authorizer in which their additional site is operated.

Chapter 3 of 2019 (SB 126, Leyva). Senate Bill 126 required charter schools and charter management organizations to comply with the same public record disclosure requirements, open meeting requirements, and conflict of interest laws that apply to school districts and COEs, including the California Public Records Act, The Ralph M. Brown Act, and the Political Reform Act of 1974.

Authorizers Are Responsible for Ongoing Oversight. At a minimum, each authorizer must fulfill five basic responsibilities: (1) identify a contact person at the charter school; (2) visit the charter school at least annually; (3) ensure the charter school completes all required reports, including the Local Control and Accountability Plan; (4) monitor the charter school’s finances; and (5) notify SBE if a charter is renewed, revoked, or the school closes. Authorizers may charge a fee of up to 1 percent of a charter school’s Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) revenue to cover the actual cost of their oversight activities. If a charter school utilizes substantially rent‑free facilities offered by their authorizer, then their authorizer can be reimbursed for the actual cost of providing oversight, up to 3 percent of the charter school’s LCFF revenue.

Charter Schools Periodically Up for Renewal. At the end of a charter’s initial authorization period, the authorizer must decide whether to renew the charter. Charter schools typically must be renewed every five years. The criteria for the renewal process generally are similar to that for approving a new charter, with the exception that charter schools seeking renewal must demonstrate a minimum level of academic performance. When a charter is up for renewal, the authorizer will review the schoolwide and student subgroup performance data of the charter school for the two years preceding the renewal decision. Under certain conditions, academic performance can dictate whether the authorizer must deny or approve the charter renewal—unless the authorizer finds that the charter school cannot implement its program or is breaking the law. For schools with the lowest academic performance on state indicators, statute specifies that authorizers must deny the renewal of the charter school. Conversely, for schools with the highest performance levels on state indicators, statute specifies that the authorizer must renew the charter school for a period of between five and seven years. For all other charter schools, they must set growth targets regarding academic performance on state indicators and the authorizer has the authority to decide to renew the charter for a term of up to five years.

Charter Schools Have Limits on Where They Can Locate and Which Students They Can Enroll. Charter schools must be located in the geographic boundary in which their authorizer operates. This restriction applies to any school facilities, resource centers, meeting spaces, and satellite facilities. Charter schools are able to enroll students from within the county their authorizer operates, as well as from all adjacent counties.

Some Charter Schools are Part of Networks. Some schools are managed by entities as part of charter school networks. Charter schools that are part of networks are legally separate schools, each with their own authorizer and governing board. The exact relationship of a charter network varies. For example, a network could have one organization that is involved in operating all programs and another network might have schools that share their educational model but each school operates independently. In some virtual programs, the network of schools operates as one school in practice where costs are shared across schools and one teacher may have students assigned in their caseload from different schools that are part of the same network. Since charter schools can enroll students from within their authorizer’s county and adjacent counties, a charter network can serve large portions of the state by having schools authorized in several key counties across the state.

Charter School Audit Requirements Differ From School Districts. Every school district, charter school, and COE in California must undergo an annual audit to verify the accuracy of its financial records and determine if it has spent funds in accordance with various state and federal laws. They must hire an auditor from a list of firms approved by the State Controller’s Office. The auditor then conducts an independent review following procedures in the audit manual developed by the state known as the Guide for Annual Audits of K‑12 Local Education Agencies and State Compliance Reporting (known as the audit guide). The audit guide includes procedures for school districts, charter schools, and COEs, such as verification of various compliance tests, including attendance records. Charter school financial reporting requirements differ in some ways from that of school districts. For example, charter schools that are organized as a nonprofit public benefit corporation follow the Financial Accounting Standards Board statements whereas school districts follow the Governmental Accounting Standards Board statements. Charter school auditing requirements are informed by both the audit guide and details specified in their charter school petition, whereas audits of school districts are informed by the audit guide and statute. Depending on the content of their charter, the specific elements of a charter school’s audit may differ from the requirements of school districts.

Charter School Funding

As With School Districts, Charter Schools Are Mostly Supported by LCFF. School districts and charter schools receive most of their LCFF apportionment through a per‑student formula that provides a base amount of funding by different grade spans. The per‑student rates for school districts and charter schools are applied to their average daily attendance (ADA)—the average number of students that attend throughout the school year. Almost one‑fifth of LCFF funding for school districts and charter schools is provided through two separate calculations based on the proportion of their student population that is an English learner, from a low‑income family, or a foster youth. Charter schools receive about $8 billion (11 percent) of total school district and charter school LCFF funding.

Charter Schools Can Be “Directly Funded” or “Locally Funded.” When a charter school is authorized, they can elect to receive their state funding in one of two ways: (1) from the county treasurer in which their authorizer operates (directly funded) or (2) from its authorizer (locally funded). The selection may also affect how a charter school applies for state and federal grants. In 2022‑23, 255 charter schools (21 percent) were locally funded. Some locally funded charter schools are operationally integrated into their authorizing school district or COE. These schools are sometimes referred to as “dependent” charter schools. A dependent charter school also commonly has its expenditure data integrated within the authorizer’s data, not reported separately. Conversely, “independent” charter schools report their expenditure data separately from their authorizers and are likely to be directly funded.

Charter Schools Have Three Options for Obtaining Facilities. When a charter school is projected to have more than 80 students attending in person in a school year, the authorizer is required to offer reasonably equivalent facilities sufficient to accommodate all of the in‑district students attending the school. Many charter schools occupy facilities provided by their authorizing district, typically paying either nominal or below‑market rent. Most remaining charter schools occupy privately leased facilities, often paying market‑rate rent. A relatively small share of charter schools have constructed or purchased their own facilities.

Some Charter Schools Have Access to Facility Funding. Unlike school districts, charter schools are unable to authorize local bonds for school facilities. However, the state provides some funding to help certain charter schools with their facility costs. The Charter School Facility Grant Program is available to charter schools that enroll or are located in the attendance area of an elementary school where at least 70 percent of students are low income. Eligible schools are reimbursed for up to 75 percent of lease and other qualifying facility expenditures incurred in the prior year, but are capped at a certain amount ($1,420 per student in 2022‑23). Additionally, the federal Charter School Facilities Program provides charter schools with funding for constructing, acquiring, or renovating new facilities through the district in which they operate. The California School Finance Authority administers both of these programs. (The Charter School Facilities Program is jointly administered with the Office of Public School Construction.) In some cases, school districts have included charter school facilities in their local bond program.

Charter Schools Have Somewhat Different Rules for Independent Study. School districts, charter schools, and COEs typically receive funding based on student attendance in an in‑person instructional program, where they receive direct supervision from a certificated teacher. In addition, they can receive funding to operate programs with a more flexible structure through independent study. Although most independent study rules apply to all entities, charter schools have somewhat different rules. Most notably, they do not have a minimum amount of instruction or work that must be completed in one day to generate funding. (See the box nearby for more detail regarding current independent study rules.)

Independent Study

Independent study programs provide students an alternative to traditional classroom‑based instruction. Rather than generating funding solely based on attendance, independent study programs also generate funding based on the work completed by students. Independent study programs range from fully online virtual academies to hybrid programs that combine on‑site and off‑site instruction. State law allows local education agencies (LEAs)—school districts, charter schools, and county offices of education (COEs)—to decide whether to provide these programs.

Basic Requirements of Independent Study Programs. Below are some of the basic requirements for all independent study programs.

- Certificated Teachers. Students must work under the general supervision of certificated teachers. State law also specifies that only certificated teachers may evaluate the seat‑time equivalent of an independent study student’s work for the purposes of generating average daily attendance (ADA).

- Individual Written Agreement. LEAs must maintain a written agreement with each student (and parent or guardian) that specifies the dates of participation, methods of study and evaluation, and other resources to be made available to the student.

- Synchronous Instruction. LEAs must offer synchronous instruction—instruction that involves real‑time interaction between students and teachers—to independent study students throughout the school year, with frequency varying by grade level. These requirements range from daily instruction for transitional kindergarten through grade three to weekly instruction for high school students.

- Student Reengagement Strategies. LEAs must establish procedures for reengaging with independent study students who do not meet certain requirements, such as students who have completed less than 60 percent of their assigned work in one week, participated in less than 60 percent of scheduled synchronous instruction in one month, or violated their independent study agreement. These procedures are to include several elements, such as notification to parents or guardians regarding lack of participation and a standard for when a student’s enrollment in independent study should be reevaluated.

- Student‑to‑Teacher Ratios. Current law limits the average number of students each independent study teacher may supervise, unless an alternative ratio is collectively bargained. These limits vary by LEA. For school districts, the student‑to‑teacher ratio for independent study programs may not exceed the overall student‑to‑teacher ratio in the district. For charter schools, the ratio cannot exceed 25 to 1. The limit for COEs is based on the overall student‑to‑teacher ratio in the high school or unified school district with the largest ADA in the county.

- Educational Standards. State law prohibits independent study from using an “alternative curriculum.” This restriction implies that independent study students must be held to the same standards as other district students. Current law, however, does not clarify what an alternative curriculum means or provide a means of enforcing the prohibition.

Charter Schools and School Districts Have Different Flexibilities. Unlike school districts, charter schools do not have a daily minimum instructional minute requirement for school days. (The daily minimum instructional minute requirement for school districts varies by grade span, from 180 minutes for kindergarten to 240 minutes for grades 9‑12.) Therefore, to claim attendance for funding purposes, charter schools only need to show that a student completed some work during each school day. (However, charter schools must follow the same minimum number of instructional minutes for the school year as school districts.) School districts must show that the work completed by a student satisfies the minimum amount of instruction for the day. However, school districts may have agreements in place where students submit work weekly and the work submitted does not need to be attributed to specific days to generate funding.

Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools

Senate Bill 740 Established New Requirements Governing Funding for Nonclassroom‑Based Instruction in Charter Schools. In the early 2000s, after a few high‑profile cases, education leaders were concerned that some charter schools offering independent study were “profiteering.” Specifically, some independent study programs spent less than the amount of funding generated by students and allowed the school operators to keep funding for personal gain. To address these issues for charter schools, the Legislature enacted Chapter 892. Most notably, SB 740 established a definition for what constitutes a nonclassroom‑based charter school and required nonclassroom‑based charter schools to request a funding determination from the California Department of Education (CDE) to receive their full apportionment. We discuss these in more detail below.

Senate Bill 740 Defined Classroom‑Based and Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools. For purposes of calculating charter school attendance for classroom‑based instruction apportionments, SB 740 requires that (1) instruction is provided by a certificated teacher, (2) at least 80 percent of instruction is offered at the school site, (3) the charter school’s schoolsite is a facility that is used principally for instruction, and (4) the charter requires its students to attend the schoolsite for at least 80 percent of the minimum instructional time required by law. Attendance that does not meet all four of the above criteria is considered nonclassroom‑based. Charter schools must designate each unit of attendance as either classroom‑based or nonclassroom‑based. For example, a student who receives in‑person instruction four days and one day of independent study would be credited with four days of classroom‑based attendance and one day of nonclassroom‑based attendance. However, for students who participate in independent study more than 20 percent of their instructional time, all of their attendance is considered nonclassroom‑based. For example, a student who receives in‑person instruction three days a week and independent study for two days a week would be credited with five days of nonclassroom‑based attendance weekly. A charter school is classified as “nonclassroom‑based” if more than 20 percent of its total annual ADA is nonclassroom‑based.

Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools Not Eligible for Some State Programs. Nonclassroom‑based charter schools are ineligible to receive funding from certain grant programs, including the Expanded Learning Opportunities Program, Charter School Facility Grant Program, and the California Community Schools Partnership Program. This is in part due to the assumption that nonclassroom‑based charter schools do not have facilities to provide classroom‑based instruction and cannot comply with the requirements of some programs that provide services to students in person.

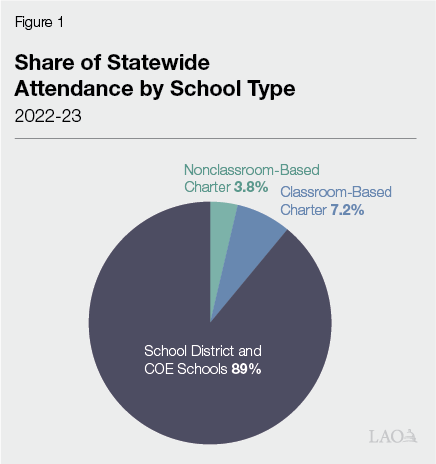

Nonclassroom‑Based Charter School Programs Vary. Nonclassroom‑based charter school programs can range from hybrid programs with a combination of on‑site and off‑site instruction to fully online virtual academies. (The level of in‑person and remote instruction that hybrid programs offer vary.) Additionally, a nonclassroom‑based charter school may offer multiple types of programs to students. In 2022‑23, the state had 313 nonclassroom‑based charter schools (25 percent of all charter schools) that served a total of roughly 222,000. These schools accounted for 38 percent of statewide charter school attendance and about 4 percent of attendance statewide that year. (Figure 1 below.) From 2018‑19 to 2022‑23, statewide nonclassroom‑based charter school attendance has increased 5 percent (about 9,500 students), whereas classroom‑based charter school attendance has decreased 3 percent (about 12,800 students).

State Commissioned a Study of Funding Determination Process Shortly After Establishment. In 2005, RAND evaluated the state’s funding determination process and found that the process had reduced misuse of funds by nonclassroom‑based charter schools and increased their spending on instruction. RAND found that nonclassroom‑based charter schools substantially increased both instructional spending and spending on certificated‑staff salaries as a proportion of total revenues in an effort to meet thresholds for full funding.

A Few High‑Profile Cases of Recent Fraudulent Activity in Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools. Over the past decade, there have been a few cases where fraudulent activity or misuse of public funds were found in nonclassroom‑based charter schools. One notable recent case is related to the A3 charter school network, where the schools were found to have fabricated attendance data that resulted in generating roughly $400 million in state funding through attendance fraud. Several former employees of the schools were subsequently convicted of crimes related to these actions.

State Enacted a Moratorium on New Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools in 2019, Set to Expire in 2026. Due, in part, to the concerns arising from high‑profile cases, Chapter 486 of 2019 (AB 1505, O’Donnell) imposed a two‑year moratorium on the establishment of new nonclassroom‑based charter schools (from 2019 to 2021). The moratorium has since been extended twice—Chapter 44 of 2021 (AB 130, Committee on Budget) extended the moratorium to January 1, 2025, and SB 114 further extended the moratorium to expire in January 1, 2026.

Funding Determination Process

Statute Directed SBE to Develop Regulations Governing Nonclassroom‑Based Charter School Funding. Senate Bill 740 directed SBE to adopt regulations that govern funding for nonclassroom‑based charter schools by February 1, 2002. SBE was required to appoint an advisory committee consisting of representatives of school district superintendents, charter schools, teachers, parents or guardians, members of the governing boards of school districts, county superintendents of schools, and the State Superintendent of Public Instruction to make recommendations to SBE on developing regulations. The legislation specified that the regulations shall include considerations for the amount of the charter school’s total budget expended on certificated employee salaries and benefits and the school’s student‑to‑teacher ratio. The legislation also authorized SBE to include other considerations for making funding determinations, as well as other conditions or limitations on what constitutes nonclassroom‑based instruction.

Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools Must Submit Funding Determination Requests to CDE. Nonclassroom‑based charter schools are ineligible to receive any funding for their nonclassroom‑based ADA without receiving an approved funding determination from SBE. (Nonclassroom‑based charter schools automatically generate full funding for any classroom‑based ADA.) To generate funding for its nonclassroom‑based ADA, the school must submit a funding determination request to CDE through a form on the department’s website using data from the prior year. Typically, these forms must be submitted to the department by February 1 in the year when a school’s funding determination is set to expire. CDE reviews the information submitted on the funding determination form, and can ask charter schools for clarifying or additional information as well as use information from the charter school’s audit to verify information on the form. After reviewing the funding determination form, CDE presents its funding determination recommendation to the Advisory Commission on Charter Schools (ACCS) who then make recommendations to SBE on the level of funding based on three thresholds discussed below. ACCS typically adopts its recommendations in April. In turn, SBE typically votes on the funding determinations in May.

Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools Must Meet Three Criteria to Receive “Full” Funding. In order to be eligible to receive full funding for nonclassroom‑based ADA, charter schools must meet three criteria:

- Spend 40 Percent of Annual Revenue on Certificated Staff Compensation. Charter schools must show that their total prior‑year expenditures on certificated staff represent at least 40 percent of total prior‑year revenues. Certificated staff costs include salaries and benefits for employees who possess a valid teaching certificate, permit, or other equivalent and who work in the charter school in a position required to provide direct instruction or direct instructional support to students. A charter school’s total revenue includes federal, state, and local funding.

- Spend 80 Percent of Annual Revenue on Instruction and Related Services. Charter schools must show that their prior‑year expenditures on instruction and related services represents at least 80 percent of prior‑year total revenue. Instruction and related services may include, but are not limited to, (1) administrative, technical, and logistical support to facilitate and enhance instruction; (2) student support services; (3) school‑sponsored extra‑curricular or co‑curricular activities; and (4) instructional materials, supplies, and equipment. Additionally, charter schools can elect to have a portion of their spending on facilities be counted towards this requirement. A charter school’s total revenue includes federal, state, and local funding.

- Certain Student‑to‑Teacher Ratios. Charter schools are required to maintain a student‑to‑teacher ratio of 25‑to‑1 (or equivalent to the largest unified school district in the county in which the charter school operates).

If a school receives full funding, all of its nonclassroom‑based ADA counts towards key funding calculations, including the school’s LCFF allotment and lottery‑based apportionment. SBE may reduce funding determinations to either 85 percent or 70 percent of full funding—meaning 85 percent or 70 percent of a school’s ADA is counted in the applicable funding calculations. Figure 2 shows the criteria for funding determinations at lower levels than full funding.

Figure 2

Funding Determination Thresholds

|

Requirement |

Funding Level |

|||

|

100 percent |

85 percent |

70 percent |

Denial |

|

|

Share of revenue spent on certificated staff |

At least 40 percent. |

At least 40 percent. |

At least 35 percent. |

Less than 35 percent. |

|

Share of revenue spent on instruction and related services |

At least 80 percent. |

Between 70 percent and 80 percent. |

Between 60 percent and 70 percent. |

Less than 60 percent. |

|

Student‑to‑teacher ratio |

25 to 1, or highest ratio in the county. |

Not applicable. |

Not applicable. |

Not applicable. |

Schools Periodically Go Through Funding Determination Process. SBE generally has the authority to grant funding determinations for up to five years. The regulations also require funding determinations of specific lengths in certain cases. New charter schools, for example, must receive their first funding determination for two years. Regulations also require the state to provide schools a five year funding determination if they meet certain performance standards. However, the specific measure of performance referenced in the regulations—the Academic Performance Index—is no longer calculated by the state. Thus, no schools are automatically eligible for five year funding determinations.

Schools May Count Facility Costs Towards Spending on Instruction. Charter schools may elect to have some of their facilities costs included towards their spending on instruction and related services. In order to be eligible, charter schools must provide information on: (1) total facility costs, (2) square footage, (3) classroom‑based ADA, and (4) the total number of hours that nonclassroom‑based students spent at school sites. The formula allows up to $1,000 per classroom‑based ADA and a prorated amount for nonclassroom‑based ADA based on the amount of time these students physically spend within the charter’s facilities.

State Board Considers Mitigating Circumstances When Making Funding Determinations. A nonclassroom‑based charter school may present additional information to CDE and SBE to request an increase in its funding level if other special or mitigating circumstances resulted in a smaller proportion of its total revenue being spent on certificated staff compensation or instruction and related services. For example, SBE considers circumstances such as a one‑time investment in a facility, extraneous special education costs, or school bus purchases. If a school can show that these types of expenses resulted in the school not meeting the expenditure, SBE typically gives the school a higher funding determination than would otherwise be assigned, but for a shorter period of time.

Specific Rules for New Charter Schools. New nonclassroom‑based charter schools must submit their funding determination request by December 1 in their first year of operation using “reasonable” estimates of their expenses. The approved funding determination for new charter schools is effective for two fiscal years. Ninety days after the end of the first fiscal year of operation, the charter school must submit unaudited actual expense reports for the first year and a funding determination form based on the school’s second‑year budget. This may result in a revision to the funding determination if the thresholds were not met in either the first year expenses or in the adopted second‑year budget. The SBE may terminate a determination of funding if updated or additional information requested by CDE and/or the ACCS is not made available by a charter school within 30 calendar days or if credible information from any source supports termination.

Schools Must Submit Additional Information in Funding Determination Forms. In addition to the spending and staffing data needed to determine a school’s funding level, nonclassroom‑based charter schools also must include additional information in their forms. This information is not intended to affect a school’s funding determination but serve as a way to screen for any potential issues that CDE may want to share with charter school authorizers. The additional information includes:

- Governing Board Composition. Charter schools are required to list the members of their current governing board. For each member, the charter must provide name, type of member (for example, parent/guardian or teacher), how the member was selected, and their term. Additionally, charter schools must identify whether any member of the board has any affiliations with entities that the charter school contracts with above certain spending thresholds. Charter schools must also indicate whether or not the governing board has adopted and implemented conflict of interest policies and procedures.

- Contracts Above Certain Spending Thresholds. Charter schools are required to list any external contracts from the previous year that were $50,000 or more, or represented at least 10 percent of total expenditures. For any contract that meets this criterion, charter schools must list the name of the entity, amount provided, details of the contract, and whether the contract payments are based on specific services rendered or based on an amount per ADA or another percentage. CDE may request copies of the contract agreements.

- Certain Excess Reserves. Charter schools must classify their reserves in several categories, including reserves for economic uncertainties, facilities acquisition or capital projects, and reserves required by the charter authorizer. Charter schools are required to report the ending fund balance in all these categories. Charter schools that have ending fund balances in either their reserves for economic uncertainties or facilities acquisition exceeding the greater of $50,000 or 5 percent of total expenditures must justify why their reserves are in excess of these thresholds.

Analysis of Funding Determination Process

In this section, we provide our overall findings and assessment regarding the funding determination process, specifically as a way to reduce profiteering. We then provide recommendations to improve the process.

Findings and Assessment

Our findings and assessment were developed based on interviews we conducted with nonclassroom‑based charter school operators and other charter school experts, review of existing data, and a review of various publications related to these issues.

Overall Findings and Assessment

Process Likely Affects School Spending. The spending thresholds and staffing ratios schools must meet to receive full funding likely have some effects on nonclassroom‑based charter school spending. Likewise, the periodic nature of submitting funding determinations likely affects school spending in specific years. Some charter schools indicated they took some specific actions to ensure they were meeting these thresholds in years that would apply to the funding determination. This is also consistent with findings from the 2005 RAND report the state commissioned on this issue. Based on our review, we are unable to determine whether this change in behavior necessarily results in better student outcomes or limits profiteering.

Process Is Not Well Targeted, but Also Has Gaps. Given the state’s broad definition of a nonclassroom‑based charter school, we find that the funding determination process is applied to many schools that operate similar to a traditional brick‑and‑mortar school and have a cost structure that make profiteering unlikely. The process also does not account for specific issues many schools face, such as facility costs and use of one‑time funding. However, the process also has notable gaps that make it less effective in monitoring school spending. Most notably, nonclassroom‑based charter schools are only required to submit one year of expenditure data, which limits the state’s ability to comprehensively assess their spending patterns. We discuss these concerns in more detail later in this section.

Process Is Not an Effective Way to Address Other Concerns With Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools. The funding determination process can be a helpful tool to monitor the overall cost structure of a nonclassroom‑based charter school and to ensure funding is being spent on staffing and other services that benefit students. The process, however, is not an effective approach for ensuring that charter schools are complying with other state laws and not committing fraud. The process may be manipulated and does not contain the checks and balances that would otherwise prevent profiteering. Other aspects of oversight, such as annual audit requirements and authorizer, county superintendent, and state oversight, are more appropriate ways to monitor these issues. Given the funding determination process is focused on reviewing periodic audited expenditures and ADA reporting, the process relies on other aspects of the system to be working effectively.

Definition of Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools

California’s Definition of a Nonclassroom‑Based School Is Broader Than Other States. In our review of policies in other states, we found that approximately 40 out of 50 states allow nonclassroom‑based charter schools (although a few of these states currently have none in operation). The remaining ten states have either not adopted a charter school law or have adopted a law specifically prohibiting nonclassroom‑based charter schools. Most states with laws pertaining to nonclassroom‑based charter schools focus specifically on schools where most or all of the instructional program is delivered virtually. The California definition—encompassing all charter schools in which more than 20 percent of instruction takes place off‑site—is broader than the definition in all other states.

“Nonclassroom‑Based” Term Is a Misnomer. The state does not collect information on the types of instructional models operated by nonclassroom‑based charter schools. It does, however, collect self‑reported data on the degree to which the schools offer virtual instruction. (This data is collected and reported to the federal government.) As Figure 3 shows, 204 nonclassroom‑based charter schools reported they offer no virtual instruction or are primarily a classroom‑based program. These schools represent half of the attendance at nonclassroom‑based charter schools. In our conversations with nonclassroom‑based charter schools, many indicated that their programs were primarily classroom‑based, with instruction and student support provided in a brick‑and‑mortar school. In other cases, schools offered remote instruction but had physical locations that students could use to collaborate with other students or meet with teachers and other support. The cost structure of these programs can be similar to that of a traditional school. Nonclassroom‑based charter schools often indicated they offer different types of educational programs (primarily in person, blended, or primarily virtual) that students can choose from. Some indicated they preferred the nonclassroom‑based designation because of the flexibility they had in deciding how to serve each student. For these schools, the term “nonclassroom‑based” does not necessarily reflect the experience of students enrolled in their programs.

Figure 3

Small Share of Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools

Are Fully Virtual

2023‑24

|

Number of Schools |

Share of Schools |

Total ADA |

Share of ADA |

|

|

Not virtual |

152 |

49% |

91,967 |

41% |

|

Primarily classroom |

52 |

17 |

26,078 |

12 |

|

Primarily virtual |

67 |

22 |

68,097 |

31 |

|

Exclusively virtual |

40 |

13 |

36,088 |

16 |

|

Totals |

311 |

100% |

222,229 |

100% |

|

ADA = average daily attendance. |

||||

Application Review

CDE Relies on Audit Reports to Verify Some Submitted Expenditure Data. To verify the validity of expenditure information included in charter school funding determination forms, CDE routinely compares the submitted information with information from their prior‑year audits. The department indicated that data in the vast majority of funding determination requests match up with the expenditure data from their audits. As long as these schools meet the spending thresholds and the student‑to‑teacher ratio threshold, they will generally be recommended to receive full funding without having to submit any additional information. When discrepancies exist between the information listed on the funding determination form and the audit report, CDE requests additional information or documentation. CDE indicated that in many cases, charter schools made an error on the funding determination form but did actually meet the requirements. CDE also indicated that in many of these cases, the charter schools just needed to update their submission. However, in some cases, CDE requests backup documentation to substantiate information listed on the form.

In Other Cases, CDE Relies on Self‑Certified Data. Although CDE can use a charter school’s audit to verify certain data (such as some expenditure data and ADA), other information reported in the funding determination form cannot be as easily verified. Based on our review of the forms and conversations we had with CDE, we identified three key components that are self‑certified and cannot be verified by annual audits: (1) spending on certificated salaries and benefits for positions required to provide direct instruction or instructional support to students, (2) the number of student hours attended by nonclassroom‑based students at a school site (used to count facilities costs as instruction related), and (3) the student‑to‑teacher ratio. CDE indicated they do not have the capacity to independently verify the information they receive from charter schools is accurate. Audits and other reports often include total spending on certificated staff, as well as the number of full‑time equivalent certificated staff employed by the charter school. These reports, however do not include data specifically for certificated staff who work directly with students, as is required in the funding determination form. CDE indicated that charter schools are not required to submit specific information about each employee that would allow the department to verify whether employees are correctly counted. In cases where CDE has concerns over accuracy of information provided by a charter school, they indicated that they reach out to the charter school’s authorizer. However, charter school authorizers are not required to be involved in the funding determination process.

Verifying Information From Some Locally Funded Charter Schools Can Be Difficult. CDE stated they had difficulty with verifying information from some locally funded charter schools. (These schools are also more likely to be dependent charter schools that have their operations integrated with that of their authorizer.) This is because expenditure data from these locally funded charter schools was included in the audit of their authorizer, and often spending is not separated out from the authorizer’s spending on its other schools. Both the Standardized Account Code Structure and the audit guide provide a mechanism for districts and COEs to separate out their spending on charter schools, but if the district has multiple locally funded charter schools they operate, then the charter school spending numbers often do not disaggregate by charter school site. CDE indicated that they will commonly ask locally funded charter schools to provide additional information to substantiate the information listed in the form.

Vast Majority of Schools Receive Full Funding. As Figure 4 shows, the vast majority of active nonclassroom‑based charter schools receive 100 percent funding. Of the schools that received full funding, 12 percent (38 schools) did not meet the spending thresholds but were granted a higher level of funding based on mitigating circumstances described in their form. CDE indicated they will recommend 100 percent funding for those that have mitigating circumstances as long as the charter school can provide a reasonable justification and previously has met the spending thresholds. (CDE can ask for additional backup information to substantiate the charter’s justification.) Despite CDE’s typical approach, several charter schools indicated that they make spending decisions specifically to comply with the spending requirements and avoid having to use mitigating circumstances at all.

Figure 4

Active Funding Determinations

2023‑24

|

100 |

85 |

70 |

Denial |

|

|

Without mitigating circumstances |

270 |

2 |

3 |

— |

|

With mitigating circumstances |

38 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

308 |

2 |

3 |

— |

|

Source: California Department of Education. |

||||

CDE Has Guidelines for Setting Length of Determinations, but They are Not Codified in Statute or Regulations. One common concern we heard from nonclassroom‑based charter schools was the lack of clarity regarding the length of their funding determination. This was often due to concerns that they did not receive a determination for the maximum of five years. In our conversations with CDE, they indicated they have used consistent guidelines in recent years when deciding on the length of a funding determination: two years for new charter schools (as required by law), two years for those with mitigating circumstances, three years for schools on their second funding determination, and four years for all others. They also indicated that, given the Academic Performance Index is no longer valid, they do not issue any five year determinations. (Based on our review of statute, we believe CDE has the authority to provide five year determinations if they chose to do so.) CDE indicates they regularly communicate these guidelines in presentations to nonclassroom‑based charter schools. However, these general guidelines are not reflected in statute or regulations, which can create confusion for schools.

Process Can Be Burdensome Initially. In our conversations with charter schools, we found that schools going through the process for the first time, particularly smaller charter schools, found the process burdensome. For larger charter schools and those that have gone through the process a few times, the process was not as burdensome. As charter schools become more familiar with the process, they structure their program around the specific requirements and regularly monitor expenses relative to the spending thresholds. Moreover, many charter schools that contract with vendors for business services were able to rely on these vendors to fill out the form and monitor any potential issues.

Only Reviewing Prior‑Year Spending Limits Effectiveness of Oversight. In accordance with current regulations, CDE generally requires charter schools to only submit data for the prior fiscal year. (They may ask for multiyear data in some cases, such as if the charter is seeking a higher funding determination for mitigating circumstances.) For a school that receives a funding determination of four years, this means that the state would not review spending in the three intervening years. Lack of reporting in the years between funding determinations limits the state’s ability to ensure schools are consistently meeting the spending criteria in line with their funding determination.

Oversight for Charter Networks Is Fragmented. Oversight via the funding determination process is more challenging for networks of schools—particularly for networks of fully virtual schools—that effectively operate as one school system. Under current law, schools that are part of a network submit separate funding determinations for each legally distinct school, even if the schools operate as one entity. These funding determinations can have different time lines, with each application representing a fraction of total spending by the school. This can make it more challenging for CDE to identify whether spending of the network as a whole is in compliance with the funding determination levels it has received, and provides an opportunity for the charter schools within the network to manipulate data relevant to the various spending thresholds and the student‑to‑teacher ratio threshold.

Funding Determination Process Not Aligned to Charter Renewal Process. Charter schools may be renewed for a period of five to seven years by their authorizer. In contrast, most charter schools receive funding determinations between two and four years (and never for five years under current practice). This means that charter schools often have to go through the charter renewal process and funding determination process at different intervals. Being subjected to these separate processes at different intervals can be administratively burdensome for schools.

Supplemental Information Provides Helpful Context. The additional required information on charter board composition, contracts above certain spending thresholds, and governing board members that have dealings with contractors provides useful information for the state to identify potential issues of fraud. CDE routinely shares this information with authorizers to make sure they are aware of any possible issues.

Instruction and Related Spending

Schools Cite Three Key Challenges for Meeting Instruction and Related Thresholds. In our conversations with nonclassroom‑based charter schools, the 80 percent threshold for instruction and related services was the most difficult requirement to meet. Schools mainly cited three issues that made meeting this requirement more difficult:

- Facilities Costs. Schools often cited their spending on facilities as a key challenge with meeting the 80 percent requirement. Although schools can have a portion of the facilities costs included towards the calculation, this can represent only a share of their actual casts. Some schools also had more difficulty meeting the 80 percent threshold when they were setting aside funds over a multiyear period to purchase a facility. These issues were more common for schools with larger facility footprints that provided more of their instruction and support in person.

- One‑Time Funding. In recent years, the state has provided several one‑time grants that can be spent over a multiyear period. If a nonclassroom‑based charter school receives these revenues in one year but does not spend them until subsequent years, this can reduce their reported spending on instruction and related services. (This can also make it more challenging to meet the certificated salaries threshold.) Because of the effect on the spending threshold, schools have an incentive to spend the bulk of these funds in the first year, even if they might be better spent slowly over a multiyear period.

- Reserves. Several charter schools indicated they planned to increase the amount they hold in reserve to deal with fluctuations in state funding and student attendance or to save for major purchases. Setting aside funding for reserves, however, reduces their spending on instruction and related services.

Virtual Programs May Have Less Difficulty Meeting Instruction‑Related Requirements. Given their specific cost model, virtual programs are less likely to have challenges meeting the 80 percent threshold. Virtual programs typically have no costs associated with instructional facilities. Compared with brick‑and‑mortar schools, they are more likely to spend on software and technology—expenses which count towards the instruction‑related requirements.

Student‑to‑Teacher Ratio Requirements

Highest Staffing Ratio in County Is Not Easily Accessible. Although regulations allow nonclassroom‑based charter schools to adhere to a 25‑to‑1 student‑to‑teacher ratio or the highest ratio for a district in the county, in practice, schools adhered to the 25‑to‑1 threshold. This is because information on the student‑to‑teacher ratios of districts in their county was often not readily available or could not be verified.

Recommendations

Summary of Recommendations. In this section, we provide specific recommendations the Legislature could enact to improve the funding determination process (Figure 5). Some changes would require modifying state law, while others could be implemented by directing SBE to adopt new regulations. Our recommendations are intended to narrow the process to schools with instructional models more likely to create the opportunity for profiteering, improve the comprehensiveness and quality of data submitted to CDE, and streamline some aspects of the process. These changes likely will affect CDE’s workload, but the specific impact will depend on implementation details. In the box nearby, we also describe an alternative approach that would eliminate the funding determination process. While this approach would have negative consequences for some charter schools, it would be easier for the state to administer.

Figure 5

Recommendations for Improving the Funding

Determination Process

|

Definition of Non‑Classroom‑Based Charter Schools |

|

|

|

|

Funding Determination Process |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alternative to the Existing Funding Determination Process

This report responds to the Legislature’s request that we make recommendations to improve the funding determination process for nonclassroom‑based charter schools. The recommendations we set forth in this report would achieve this purpose. Under these recommendations, the process would continue to require additional workload for the state, nonclassroom‑based charter schools, and authorizers. Below, we set forth an alternative that would eliminate most state‑level administration. This approach, however would negatively affect nonclassroom‑based charter schools with higher cost models, particularly those with higher facility costs. This approach would also eliminate some ways the state currently monitors spending for nonclassroom‑based charter schools.

Set a Fixed Percentage of Funding for Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools. As an alternative to the funding determination process, the Legislature could provide a prorated amount of funding to nonclassroom‑based charter schools, regardless of their expenditures. This would eliminate the need for the funding determination process entirely. The Legislature could provide the same prorated amount for all nonclassroom‑based charter schools (for example, based on 85 percent funded ADA, consistent with the middle category in the current process). Alternatively, the Legislature could create a sliding scale based on the amount of in‑person instruction a school provides. This change could be implemented in conjunction with a change in the definition of a nonclassroom‑based charter school. (Narrowing the definition would mean that fewer schools would receive a prorated funding amount.)

Allow Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools to Obtain Funding for Instructional Facilities. In our conversations with nonclassroom‑based charter schools, many had substantial facility blueprints, which often resulted in relatively higher costs. To provide these schools with access to facility funding, the Legislature could allow them to participate in the Charter School Facility Grant Program. This would allow nonclassroom‑based programs where 70 percent or more of their students are low income to be eligible for additional funds. Those with lower proportions of low‑income students, however, would be ineligible.

Consider Alternative Spending Requirements. If the Legislature were to eliminate the existing funding determination process, nonclassroom‑based charter schools would no longer be required to meet the spending thresholds for certificated salaries and instruction and related services. The Legislature could alternatively apply the “current expense of education” calculations to nonclassroom‑based charter schools and require that at least 40 percent of their expenditures are spent on salaries and benefits of classroom teachers and instructional aides. (This is similar to recommendation we make in this report for improving the existing funding determination process.)

Definition of Non‑Classroom‑Based Charter Schools

Narrow the Definition of a Nonclassroom‑Based Charter School. We recommend narrowing the definition of a nonclassroom‑based charter school so that the designation excludes those schools that primarily provide instruction in person. Although all nonclassroom‑based charter schools are mostly funded under independent study rules, many of them provide a substantial portion of instruction and other support services to students in person. These programs often have cost structures similar to that of more traditional classroom‑based charter schools. Compared to the existing definition, a narrower definition would allow charter schools funded primarily on independent study to be excluded from the funding determination process if they can demonstrate they have a significant portion of their instruction provided in person. To implement this recommendation, we recommend the Legislature develop a specific definition based on the proportion of instruction provided in person and require a school’s percentage to be included in the annual audit process. Although the Legislature could consider a variety or definitions, we think a reasonable starting point is to designate a school as nonclassroom‑based if less than half of its instruction occurs in person. (Compared with less than 80 percent under current law.) We also recommend that the narrower threshold of nonclassroom‑based be used when determining whether ADA is classroom‑based or nonclassroom‑based. The Legislature could create an even narrower definition if it wanted to focus the funding determination on those that are primarily virtual programs. Charter schools no longer classified as nonclassroom‑based would become eligible for other state programs, such as the Charter School Facility Grant Program and the Expanded Learning Opportunities Program.

Make the Definition of a Virtual Charter School Subject to the Annual Audit. We recommend the Legislature define a virtual charter school in statute, require each charter school to report whether or not they meet this definition, and make the designation subject to the annual audit process. Having a specific definition would help the state better track changes in virtual programs over time and make it easier to set specific requirements for these programs in the future. The state currently collects self‑reported data related to virtual programs, but does not verify the results. Existing state regulations also include a definition of a virtual charter school (where at least 80 percent of instruction occurs online), but this definition has no current practical use and also is not verified by an external entity. We recommend the Legislature use this latter definition as a starting point, though it could modify the threshold.

Establish a Definition of a Virtual Charter Network in Statute. To better monitor issues related to networks of charter schools operating as one school system, we recommend adding a specific definition in statute and requiring the definition be verified in annual audits. We recommend this definition focus on networks of virtual charter schools that provide instruction to students from across the state in virtual courses taught by one instructor, regardless of the student’s location.

Funding Determination Process

Require Additional Review of Data Submitted to CDE. To assist CDE in efficiently reviewing and processing funding determination forms, we recommend requiring additional verification of information submitted to CDE. Specifically, we recommend requiring data submitted by charter schools be consistent with their annual audits. If the information in the funding determination form is not consistent with the information reported in their annual audit, charter schools would be required to provide clarification and backup documents along with their form. We further recommend that charter school funding determinations be submitted concurrently to the charter school’s authorizer, and that the authorizer be required to review the request and notify CDE of any concerns, such as discrepancies with data.

Require Authorizers to Separately Track Data for All Their Nonclassroom‑Based Charter Schools. Given CDE’s concerns with obtaining expenditure data for some dependent, locally funded charter schools, we recommend authorizers be required to separately track expenditure and staffing data for each of their nonclassroom‑based charter schools included in their annual audits. This would make it easier for CDE to verify the information submitted in the funding determination form for these schools. (Authorizers have several options for tracking these expenditures separately. For example, they can track revenues and expenditures using a separate fund for their nonclassroom‑based charter school.)

Use Multiple Years of Data for Funding Determinations. We recommend the funding determination take into consideration a school’s aggregate spending for all years since the previous funding determination. This would ensure school expenditures are aligned with the funding determination thresholds consistently over time. (Not just in the year prior to the funding determination.) We recommend schools continue to submit forms to CDE in the intervening years. CDE could review them on an interim basis and could notify schools that are at risk of not meeting the spending thresholds. In cases where a school is significantly below the thresholds, CDE could revisit a school’s funding determination in one of the intervening years.

Require Networks Operating as One School System to Apply Concurrently. For any networks that effectively operate as one school system, we recommend requiring they submit their funding determination forms in the same year. This would allow for a more comprehensive view of program expenditures.

Align Funding Determination With Charter Renewals, Codify Rules in Statute. We recommend maintaining the current requirement that new nonclassroom‑based charter schools receive funding determinations for two fiscal years. Moving forward, we recommend the length of funding determinations be aligned with the time line for a charter school’s renewal. Aligning the time line to a charter renewal would likely result in longer funding determinations, reducing the administrative burden for schools and CDE. (Under our recommended approach, CDE would still have the authority to flag schools in the intervening years based on interim reporting.) To ensure consistency and transparency, we also recommend codifying in statute the rules regarding the length of a funding determination. (Even if the Legislature does not take our approach for setting the length of determination, we recommend the rules be set in statute.)

Use an Existing Calculation for Measuring Spending on Certificated Staff. To create consistency and make it easier for CDE to verify, we recommend the Legislature take a different approach for measuring spending of certificated staff. Specifically, we recommend nonclassroom‑based charter schools be required to meet the 40 percent spending threshold using the “current expense of education” calculations and to have those calculations included in their annual audit. Under current law, school districts must report their current expense of education annually using a methodology specified by CDE, and are expected to spend a certain percentage on salaries and benefits of classroom teachers and instructional aides. (The requirements range from 50 percent for high school districts to 60 percent for elementary school districts.) These calculations must be included in a district’s annual audit. Using this approach for nonclassroom‑based charter schools would use an existing calculation that has a clear methodology and is already included in audits for school districts. (Given the variety of instructional models that nonclassroom‑based programs use, we recommend keeping the threshold at 40 percent, rather than the higher thresholds for school districts.)