March 14, 2024

Increasing Transparency of County

Office of Education Spending

Summary

County Offices of Education (COEs) Have Two Distinct Missions. COEs provide direct instruction to students in juvenile court and county community schools. These schools serve students who are placed in county juvenile facilities, on probation, referred by a probation department, or mandatorily expelled from their school district. COEs also provide oversight and support to school districts in their county. Some of these activities are required by law, while others are optional and vary across the state. COEs receive state funding primarily through the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Similar to COEs’ two‑part mission, the LCFF has two main components—an alternative education grant based on the number of students attending juvenile court and county community schools and an operations grant based on the number of school districts and number of students in the county. COEs generally have flexibility to use their LCFF funding from either part of the formula for any purpose.

COEs Must Adopt Local Control and Accountability Plans (LCAPs). To provide transparency regarding how LCFF funding is spent, COEs must annually adopt LCAPs for their spending on juvenile court and county community schools. LCAPs, must include goals related to several state priority areas and specify actions COEs will take to meet these goals. COEs also must include information demonstrating that they are increasing or improving services for English learners (ELs), low‑income students, and foster youth.

State Law Requires Review of COE Plans. Chapter 48 of 2023 (SB 114, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) requires our office to make recommendations to change the COE LCAP or require alternative reporting requirements outside of the LCAP. The recommendations are primarily intended to increase transparency of COE operations and activities.

Recommend an Annual Report That Describes Major COE Activities. Existing COE budget data does not provide helpful information on how COEs support school districts and students. COE budgets often include significant amounts of revenue for which COEs simply pass through funding to school districts and other local governments. These pass‑throughs make it more difficult to understand what variation in funding and spending is due to a COE’s specific role in the county. To better understand each COE’s role, we recommend an annual report that includes a narrative of the major activities and services COEs conduct, allowing local partners and the state to understand the key work COEs do to support school districts and students.

Recommend Several Changes to LCAP. We find several issues with current LCAPs. In particular, some spending information can be difficult to interpret, focusing on increases in services for specific student groups is arbitrary given the COE student population, and some state‑required metrics are not particularly relevant for assessing COE‑run programs. We recommend a variety of changes to LCAPs that would make spending information easier to interpret, allow state and local partners to better understand existing programs and services to students, streamline certain aspects of the LCAP, and use metrics for COEs that would be a better indication of performance in COE‑run schools.

Recommend Expenditure Report on Operations Grant Funding. The LCFF operations grant has no reporting requirements and is unrestricted, which means the state knows very little about how these funds are spent. We recommend COEs develop a report specifically on how the LCFF operations grant was spent. The report should disaggregate spending into three categories: (1) oversight and support to school districts, (2) juvenile court and county community schools, and (3) direct services to students not enrolled in juvenile court and community schools. The report should also be in a format that is comparable across the state.

Introduction

COEs Have Two Distinct Missions. COEs provide direct instruction to students in juvenile court and county community schools. These schools serve students placed in county juvenile facilities, as well as students who are on probation, referred by a probation department, or mandatorily expelled from their school district. In addition to serving these specific students, COEs provide a range of oversight and support to school districts in their county. Some of these activities, such as fiscal and academic oversight, are required by state law. Many other activities COEs conduct are optional, with the specific activities conducted by COEs varying significantly across the state. COEs receive most of their state funding for activities aligned with these missions through the LCFF. The formula includes two components intended to align with COEs’ two‑part mission, although COEs generally have flexibility to use their LCFF funding from either part of the formula for any purpose.

COEs Must Adopt LCAPs. To provide transparency regarding how LCFF funding is spent, COEs are required to annually adopt LCAPs for their spending on juvenile court and county community schools. In their LCAPs, COEs must set goals related to several state priority areas and specify actions they will take to meet these goals. COEs also must include information demonstrating that they are increasing or improving services for ELs, low‑income students, and foster youth.

State Recently Enacted COE Funding Increases and New Reporting for COE‑Run Programs. The 2022‑23 and 2023‑24 budget plans included increases to the COE LCFF beyond the statutory cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA). This included increases to rates in both components of the formula, new minimum grant amounts for COEs that operate juvenile court and county community schools, and an attendance policy designed to cushion COEs from declines in attendance and reduce year‑to‑year fluctuations in funding. In addition, the state created a new student support and enrichment block grant for students enrolled in juvenile court and county community schools. The 2023‑24 budget package also included several state actions related to juvenile court and county community schools. Most notably, the budget package required the California Department of Education (CDE) to begin reporting certain access and outcome data for juvenile court and county community schools and contract for an independent evaluation of these schools. The department must provide a report to the Legislature and administration regarding this evaluation by November 1, 2025.

State Law Requires Report on Transparency of COE LCAPs. Chapter 48 requires our office to recommend changes to the LCAP for COEs or, to the extent feasible, recommendations for alternative reporting requirements outside of the LCAP. The recommendations are to (1) increase transparency of COE operations and programs, (2) provide methods to shorten and simplify the LCAP, (3) increase transparency of COE responsibilities and activities, (4) identify methods to display all funds apportioned to COEs, and (5) track spending increases and their impact on student outcomes. This report responds to the statutory requirement.

Background

Overview of COEs

State Constitution Establishes Role of County Superintendents in Schools. The State Constitution establishes county superintendents of schools. County superintendents are either elected by voters in their counties or appointed by their county’s board of education. The Constitution authorizes voters to elect these county boards of education. State law requires these boards to consist of five or seven members representing different areas of the county. Currently, all but five county superintendents are elected rather than appointed by the boards. County superintendents and their staff are commonly referred to as COEs. County superintendents manage the daily operations of these COEs.

County Boards of Education Have Certain Constitutional and Statutory Responsibilities. The Constitution gives county boards of education authority to set their county superintendent’s salary and state law tasks them with approving annual COE operating budgets. State law further tasks county boards of education with approving certain academic plans developed by the COE. County boards of education also effectively serve as an appellant body, hearing disputes among local groups that have been unable to be resolved at the district level. For example, a group can appeal to the county board of education if a school district denies its application to open a charter school. Similarly, parents can appeal to the county board if their home district has expelled their child and they would like the decision overturned.

Juvenile Court and County Community Schools

Many COEs Operate Juvenile Court Schools. State law makes COEs responsible for ensuring students placed in county juvenile facilities are provided with an educational program. To comply with this requirement, COEs may directly educate students at juvenile court schools or arrange for another COE or school district to educate the students. Since juvenile court school students are in county‑run facilities, COEs operate these programs in partnership with county probation departments. Preliminary data for 2023‑24 shows that 43 COEs (and one school district) currently operate court schools. Of these COEs, 39 operate one court school and four operate two or more court schools. Altogether, these schools serve an average of 3,402 students per day as measured by average daily attendance. On average, each COE serves 85 students per day across their juvenile court schools, though this varies significantly by county, from seven students to 577 students. The cumulative number of students served in court schools throughout the year is much higher, as students often attend these schools for short periods of time while they await trial—a few days to a few weeks in many cases. For example, in 2022‑23, roughly 2,200 students were enrolled across all juvenile court schools on census day (the first Wednesday of October) compared with roughly 12,400 students cumulatively enrolled throughout the school year (about five and a half times census day enrollment).

COEs Also Typically Operate County Community Schools. State law designates COEs as a provider of education for students who are on probation, referred by a probation department, or mandatorily expelled from their school district. (State law requires students to be expelled if they commit certain violent or drug‑related offenses.) COEs receive direct funding for these students, who typically are served at COE‑run county community schools, or at charter schools authorized by the COE. (In cases where COEs do not operate county community schools, students receive another placement, such as a district‑run program.) The state also allows COEs to enroll other students in their county community schools. For these other students, COEs must develop local agreements under which the students’ home districts reimburse them for associated education costs. Preliminary data from 2023‑24 shows that 51 COEs operate 74 county community schools serving an average of 19,964 students per day statewide. Like juvenile court schools, the cumulative enrollment of students at these schools is higher. COEs receive direct funding for 6,993 of these students and receive funding for 7,115 students through local agreements negotiated with school districts. The remaining 5,856 students attend charter schools for which COEs do not receive direct funding. The size of the community school student population varies significantly by COE, with about half of COEs that operate county community schools averaging less than 65 students attending per day and the largest COE serving an average of 6,007 students per day.

Oversight and Support

State Law Requires COEs to Provide Fiscal Oversight of School Districts. The second column of Figure 1 shows all the services COEs are required to provide to school districts within their jurisdictions. Most notably, Chapter 1213 of 1991 (AB 1200, Eastin) established the current fiscal oversight process, whereby COEs regularly monitor district solvency. Specific associated responsibilities include the review and approval of school district budgets, the review of interim financial reports during the year, additional monitoring and technical assistance for districts identified as being at risk for fiscal insolvency, and more extensive intervention when districts are in severe fiscal distress. Additionally, state law requires COEs to support districts in various other ways, including assisting them on certain pension and insurance‑related issues.

Figure 1

State‑Required and Optional Activities

|

Required |

Optional |

|||

|

Alternative Education |

District Services |

Common Direct Instruction |

Common District Services |

|

|

Juvenile Court Schools |

District LCAP review, approval, and related technical assistance |

Career technical education |

Teacher professional development |

|

|

County Community Schoolsa |

Support of districts identified as needing improvement |

Child care and preschool |

District LCAP development and implementation |

|

|

Fiscal oversight |

Migrant education programs |

Leadership training |

||

|

Oversight of basic learning conditionsb |

Adult education |

Standards implementation |

||

|

Review of school staff assignments and credentials |

Indian education programs |

Dissemination of information about state policies |

||

|

Support of county board of education on appeal issues |

After school programs |

Internet connectivity and technology assistance |

||

|

Review of certain district audit findings |

Foster youth services |

Data support |

||

|

Review of districts’ LCFF unduplicated pupil counts |

Violence and drug prevention programs |

Assessment support |

||

|

Support of County Committee on School District Organization |

Charter school monitoring and investigation |

|||

|

CalSTRS and CalPERS retirement reporting |

Legal and business services |

|||

|

Support of unemployment insurance management system |

Printing and production services |

|||

|

Technical assistance for after school, drug prevention, and foster youth programs |

||||

|

aCOEs receive funding to operate these schools if they serve students with certain characteristics. bCOEs are required to review the condition of facilities, availability of textbooks, and teacher assignments in designated low‑performing schools. |

||||

|

LCAP = Local Control and Accountability Plan; LCFF = Local Control Funding Formula; and COEs = county offices of education. |

||||

COEs Also Must Review and Approve School District Plans. Chapter 47 of 2013 (SB 859, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) tasked COEs with reviewing and approving school district LCAPs. As part of this process, state law requires COEs to verify that district LCAP documents use the state‑approved format; align with districts’ adopted budgets; and appropriately direct funds to ELs, low‑income students, and foster youth. If district LCAPs meet these requirements, COEs must approve them. If a COE rejects an LCAP, it must provide the district with technical assistance in modifying its plan.

State Also Tasks COEs With Academic Oversight and Support. Chapter 32 of 2018 (AB 1808, Committee on Budget) established a system of support for school districts and charter schools identified for “differentiated assistance.” School districts and COEs are identified for differentiated assistance based on the performance of their student subgroups. Under current practice, a district or COE enters differentiated assistance if they have at least one student group that has received the lowest performance level in two or more priority areas. (We describe state priority areas in more detail later in this report). In 2023, 466 school districts and COEs and 203 charter schools were identified for differentiated assistance. For each of the districts and charter schools within its county identified for differentiated assistance, the COE is to take at least one of four actions: (1) assist the school district in identifying its strengths, weaknesses, and student groups that are low performing or experiencing disparities from other student groups; (2) secure an academic, programmatic, or fiscal expert; (3) ask for assistance from the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence; or (4) identify the strengths and weaknesses in a school district’s LCAP. (Identified COEs receive assistance from either CDE, a consortium of COEs, or another COE.)

COEs Historically Have Fulfilled Other Functions Voluntarily. As the next two columns of Figure 1 show, many current COE activities are not required by state law. Virtually all COEs provide one or more optional services to school districts. Optional services commonly include staff training, data support, and legal and business support. Exactly what optional services COEs provide varies across the state and is highly dependent on services needed within the county. For example, some COEs serving many small school districts cover basic business services (such as payroll and procurement) for districts in the county. For the districts that receive these services, the COE is providing an essential function. Many COEs also historically have applied for various state grants to provide direct student instruction to students that reside in the county. Most commonly, COEs have provided career technical education, child care and preschool programs, migrant education programs, and adult education. These programs tend to be offered regionally to students attending schools within the county.

COEs Vary Greatly in Terms of the Number of School Districts They Serve. In California, COEs have an average of 16 school districts within their jurisdictions, but the range is large. Los Angeles County has the most school districts (80). In contrast, seven counties (Alpine, Amador, Del Norte, Mariposa, Plumas, San Francisco, and Sierra) have a single district within their jurisdictions. Though each of these counties still has a county superintendent of schools and a county board of education, its COE typically functions more like an extension of the school district office. In recognition of these especially tight district‑county relationships, CDE—rather than the COEs—undertakes required oversight activities on behalf of the seven districts.

State Often Tasks Certain COEs to Take on Regional or Statewide Roles. The state has given regional or statewide roles to COEs for a wide range of educational issues. For example, in 2004, Imperial COE was selected as the grantee tasked with helping schools across the state connect to high‑speed broadband internet and continues to do these activities two decades later. The state also provides funding for nine COEs to serve as geographic leads that help build capacity of other COEs within their region to effectively provide differentiated assistance to school districts. Typically, COEs taking on additional state level and regional roles are selected through a competitive application process and receive additional funding for these new activities.

Funding

LCFF Is Primary Source of State Funding for COEs. In crafting LCFF in 2013, the state consolidated most state funding for COEs and replaced most of the former funding formulas with a new, two‑part formula. As Figure 2 shows, the alternative education grant provides funding based on the average daily attendance of students enrolled in juvenile court and county community schools. For funding purposes, the state credits COEs with their average daily attendance in the current year, prior year, or the average of three prior years, whichever is higher. Beginning in 2023‑24, COEs also began receiving minimum grants if they operated at least one juvenile court school and at least one county community school. (These minimum grants are technically considered add‑ons, separate from the alternative education grant.) The operations grant provides funding based on the number of school districts and number of students in the county. COEs also receive add‑on funds associated with two categorical programs—the Targeted Instructional Improvement Block Grant and the Home‑to‑School Transportation program—that existed prior to LCFF. COEs that received funding from these programs in 2012‑13 continue to receive that same amount of funding in addition to what the LCFF provides each year. (Home‑to‑School Transportation began receiving an annual COLA in 2022‑23.) Each COE’s target funding level is the sum of the alternative grant, operations grant, and add‑ons. Like the school district LCFF, the COE LCFF is funded by a combination of state General Fund and local property tax revenue, with the proportion of each fund source varying by county. Although the two components are intended to cover costs of alternative education programs and district support services, respectively, COEs generally have flexibility to use the their LCFF funding from either part of the formula for any purpose. (The one exception is related to supplemental and concentration grant funds which we discuss in greater detail later in this section.)

Figure 2

Components of Local Control Funding Formula for

County Offices of Education (COEs)

2023‑24

|

Alternative Education Grant |

|

|

Eligible student population |

Students who are (1) under the authority of the juvenile justice system, (2) probation referred, (3) on probation, or (4) mandatorily expelled. |

|

Base funding |

$16,395 per student.a |

|

Supplemental funding |

Provides 35 percent of the base rate for each student that is an English learner, low income, or foster youth.b |

|

Concentration funding |

Each English learner, low‑income student, and foster youth above 50 percent of enrollment generates an additional 17.5 percent of the base rate for juvenile court schools and 35 percent for county community schools.b |

|

Minimum grantsc |

$200,000 for COEs that operate at least one court school and $200,000 for COEs that operate at least one county community school. |

|

Operations Grant |

|

|

Base funding of $872,151 per COE. |

|

|

Plus $347,167 per school district in the county. |

|

|

Plus $69 to $109 per student in the county (less populous counties receive higher per‑student rates). |

|

|

aAs measured by average daily attendance. bFor juvenile court schools, all students are considered low income. cMinimum grants technically considered add‑ons separate from the alternative education grant. |

|

|

Note: COEs also receive funding from add‑ons associated with the Targeted Instructional Improvement Block Grant and Home‑to‑School Transportation. |

|

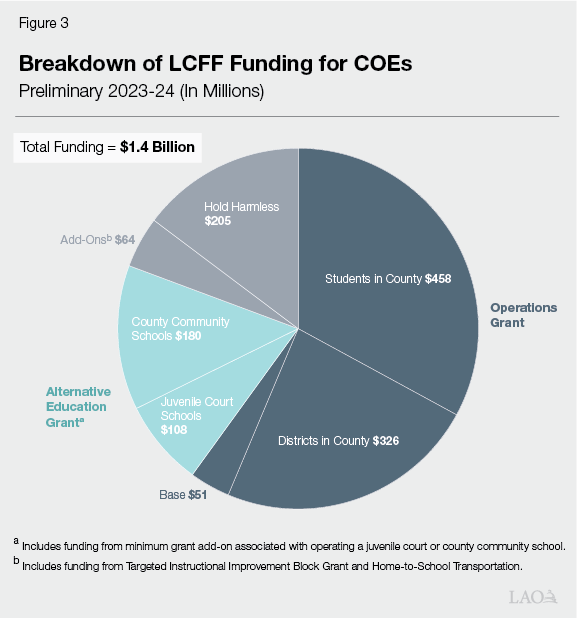

COEs Also Receive “Hold Harmless” Funding Through LCFF. When the state transitioned to LCFF, it included two provisions intended to hold harmless COEs that otherwise would have received less funding under the new formula. The first provision guarantees that each COE will continue to receive at least as much total funding as it received from revenue limits and categorical programs in 2012‑13. The activities formerly associated with this funding, however, are no longer required. Preliminary data from 2023‑24 shows that 47 COEs (81 percent) are funded at the levels specified by their LCFF targets, with the remaining 11 being funded at their higher 2012‑13 funding levels. Beginning in 2022‑23, the state began growing the 2012‑13 funding levels with an annual statutory COLA. The second provision, known as minimum state aid, ensures that each COE will continue to receive at least as much state General Fund as it received in 2012‑13 for categorical programs. The amount of minimum state aid to which each COE is entitled varies based on historical participation in categorical programs, with those that ran more and/or larger programs receiving larger amounts of state aid. Over one‑third of COEs (22 of 58) receive minimum state aid funding. Similar to the first hold‑harmless provision, COEs are not required to provide the services that originally generated the minimum state aid allotment. Almost half of COEs (26 of 58) receive funding from one or both hold harmless provisions. This funding can be used for any purpose. As Figure 3 shows, the preliminary hold harmless funding for 2023‑24 is $205 million—15 percent of all LCFF funding. In the rest of this report, we refer to additional LCFF allotment beyond the alternative education and operations grant as hold harmless funding.

COEs Receive Other Funding to Provide Direct Services to Students. In addition to their LCFF alternative grant funding, COEs also receive funding from various other sources to provide direct services to students. In most cases, these programs allocate funding to school districts, COEs, and charter schools. Several notable sources include:

- Student Support and Enrichment Block Grant. In 2023‑24, the state began providing COEs with $3,000 per student in juvenile court and county community schools. Funds can be used for a variety of activities, such as expanding access to career technical education, elective, world language, and A‑G courses; college/career or transition counseling; mental health support services; and providing postsecondary options for incarcerated youth who have a high school diploma or high school equivalency certificate. Based on preliminary data, COEs received $34 million in 2023‑24 for this purpose.

- Equity Multiplier. In 2023‑24, the state began providing $300 million annually to schools that have student populations with relatively high shares of poverty and mobility. Funding must be used for evidence‑based services and supports for students, and must result in increased or improved services compared to what otherwise would have been provided to students in these schools. Schools receiving equity multiplier funding must set specific goals for improving performance of low‑performing student subgroups. About $29 million of the total allocation in 2023‑24 is provided to 103 COE‑run juvenile court and county community schools. This represents 81 percent of all juvenile court and county community schools operated by COEs.

- Federal Title I Funding. The federal government provides funding to schools for improving academic achievement and providing support to high‑needs students. In 2023‑24 COEs received $31 million from Title I, Part A to support students in schools with high shares of low‑income students, and $17 million from Title I, Part D, Subpart 2 to support students who are neglected, delinquent, or at risk.

- Special Education. Many COEs coordinate special education services within their region. These COEs receive funding for providing services to students with disabilities from various federal and state sources. The exact role COEs have depends on regional decisions about how funding will be administered and how special education services will be provided to students. In some cases, the COE serves as an administrative agent that initially receives funding and then passes funds through to school districts that provide the special education services. In other cases, COEs are directly hiring and providing services to students in the county. COEs also receive special education funding for students with disabilities enrolled in juvenile court and county community schools.

- State Preschool and Head Start. COEs operate a substantial number of preschool programs. About 71 percent of COEs operate State Preschool, the state funded preschool program for three‑ and four‑year olds. Many COEs also operate federally funded Head Start programs.

- Career Technical Education. Many COEs receive funding from state and federal grant programs to provide career technical education opportunities to students. For example, in 2023‑24, about half of COEs received funding from the Career Technical Education Incentive Grant totaling roughly $22 million. Additionally, in 2022‑23, nine COEs received federal Perkins V funding either individually or as part of a consortia, totaling about $1 million.

COEs Also Receive Other Funds for School District Support Services. COEs also receive some additional funding outside of LCFF for specific services provided to school districts.

- Differentiated Assistance. The state provides COEs with additional funding for their differentiated assistance activities through a formula based in part on the number of districts in need of assistance. In 2023‑24, the state provided COEs $84 million for this purpose.

- Foster Youth Services Coordinating Program. The state provides COEs with funding to coordinate support services to foster youth in their county. Each COE receives funding based on the number of foster youths in their county and the number of school districts in the county. Total statewide funding for this purpose is about $32 million ongoing.

- Fee‑for‑Service Contracts. COEs generate revenue locally through fee‑for‑service contracts. For example, some COEs have contractual agreements to provide payroll or accounting services to their districts. (Other COEs provide these services at no charge as part of their palette of optional services.)

Local Control and Accountability Plans

State Required LCAPs Beginning in 2014‑15. To provide transparency regarding how LCFF funding is spent, the state requires COEs, school districts, and charter schools to adopt LCAPs. The state sets specific requirements for engagement with educational partners in developing and adopting LCAPs. In their LCAPs, COEs, school districts, and charter schools must set goals in state priority areas and specify actions they will take to meet these goals. Although we focus on COEs in this section, all of the LCAP requirements generally apply to school districts and charter schools unless otherwise noted.

COEs Must Adopt LCAPs for Their Juvenile Court and County Community Schools. The LCAP is a three‑year plan that outlines each COE’s strategy to improve outcomes for students enrolled at its juvenile court and county community schools. The plans are intended to hold COEs accountable for serving these students and provide information to the public about the services students receive. In addition, students attending alternative schools participate in the state’s standardized testing system.

COEs Must Adopt LCAPs Every Three Years and Update Them Annually. LCAPs are three‑year plans that school districts must update annually. Through a vote of their local governing board, COEs must adopt (or update) their LCAP by July 1 every year, in conjunction with their annual budget adoption. COEs also are required to hold at least two public hearings to discuss and adopt (or update) their LCAPs. The COE must first hold at least one hearing to solicit recommendations and comments from the public regarding expenditures proposed in the plan. It then must adopt (or officially update) the LCAP at a subsequent hearing. COEs are also required to annually present a midyear report on the LCAP to their governing board, no later than February 28. The report must include a midyear update for metrics identified in the current LCAP and midyear expenditure and implementation data on all actions identified in the LCAP.

COE LCAPs Based on Ten State Priority Areas and Associated Performance Measures. The legislation enacting LCFF establishes a framework for LCAPs based around goals in ten state priority areas. (Eight of these ten priority areas apply to school districts and charter schools, while two apply only to COEs.) Statute also directs the State Board of Education (SBE) to address several implementation details, such as developing an LCAP template that all COEs must use. As shown in Figure 4, some priority areas focus on academic success (such as student achievement and course access), while others address issues outside of academics (such as parental involvement and school climate). SBE also has established 13 performance measures in the state priority areas intended to monitor performance. Seven of the performance measures are metrics that COEs report to the state and are measured consistently statewide. The remaining six measures are local indicators for which COEs report locally developed metrics or qualitative information describing their progress in the priority area. In addition to these required state and local measures, COEs may include other performance measures in their LCAPs.

Figure 4

State Has Performance Measures in

Ten State Priority Areas

|

State |

Local |

|

|

Basic Conditions of Learning |

||

|

Access to instructional materials, appropriately assigned teachers, and facility conditions |

X |

|

|

Implementation of State Standards |

||

|

Implementation of academic standards |

X |

|

|

Parent Engagement |

||

|

Parent and family engagement |

X |

|

|

Pupil Achievement |

||

|

English Language Arts assessment |

X |

|

|

Mathematics assessment |

X |

|

|

English learner progress |

X |

|

|

College and career readiness |

X |

|

|

Pupil Engagement |

||

|

High school graduation rate |

X |

|

|

Chronic absenteeism |

X |

|

|

School Climate |

||

|

Suspension rate |

X |

|

|

Local climate survey |

X |

|

|

Course Access |

||

|

Access to a broad course of study |

X |

|

|

Other Student Outcomes |

||

|

No specific indicators adopted |

X |

|

|

Coordination of Instruction for Expelled Studentsa |

||

|

No specific indicators adopted |

X |

|

|

Coordination of Services for Foster Youtha |

||

|

No specific indicators adopted |

X |

|

|

aThis state priority area only applies to county offices of education. |

||

Statute Requires COEs to Set Goals in State Priority Areas. For each of the state and local measures, statute requires COEs to establish performance targets for its students, student subgroups, and schools. (Statute identifies 13 student subgroups—eight racial and ethnic groups as well as ELs, low‑income students, foster youth, students with disabilities, and homeless students.) Statute requires that COEs establish these targets for the coming school year as well as the next two years. COEs are required to evaluate progress towards meeting the goals specified in LCAPs over a three‑year period.

COEs Required to Develop Additional “Focused Goals” in Certain Circumstances. Beginning in 2024‑25, COEs are required to develop focused goals for: (1) schools receiving equity multiplier funding; (2) schools that received the lowest performance level based on one or more state indicators; and (3) student subgroups that received the lowest performance level based on one or more state indicators, either across all the COE’s schools or at a specific school. Focused goals for equity multiplier schools must be specific to improving performance for low‑performing student subgroups and addressing any issues with teacher credentialing and preparation.

COEs Must Specify Actions They Will Take to Achieve Goals. A COE’s LCAP must specify the actions the COE plans to take to achieve its goals. The specified actions must be aligned with the COE’s adopted budget. For example, a COE could specify that it intends to provide individualized transition plans for its juvenile court school students upon release. To ensure the LCAP and adopted budget are aligned, the COE would be required to include sufficient funding for staff positions to develop transition plans and assist in the coordination of services for families. COEs are required to assess the effectiveness of actions taken to achieve goals specified in their LCAP and are required to change actions that have not been effective towards meeting their intended goal over a three year period.

COEs Must Ensure “Proportionality” When Spending Supplemental and Concentration Grant Funds. COEs must include information demonstrating that they are increasing or improving services for ELs, low‑income students, and foster youth in proportion to their supplemental and concentration funding. As part of these requirements, COEs also must provide justification if they plan to spend their supplemental and concentration funding for schoolwide purposes or for all COE‑run programs. SBE is required to develop regulations implementing these provisions. The existing regulations allow COEs to reflect their increase or improvement in services in quantitative or qualitative ways. (The LCAP template allows COEs to include spending information and a narrative description to demonstrate how services will increase or improve.) COEs must report the total amount of supplemental and concentration funding they expect to receive, as well as describe how they plan to use their supplemental and concentration funding for the benefit of ELs, low‑income students, and foster youth. They also must report how the proportional increase in supplemental and concentration funding meets a proportional increase in services for these students. COEs are required to track whether any supplemental and concentration funding goes unspent in any given year, and must set aside any unspent funds for increasing and improving services in future years.

COEs Must Solicit Input in Developing Plan. COEs also must follow a process for soliciting input in adopting their LCAPs. One of the main requirements is that a COE consult with its school employees, local bargaining units, parents, and students. As part of this consultation process, COEs must present their proposed plans to a parent advisory committee and, in some cases, a separate EL parent advisory committee. (EL parent advisory committees are required if ELs comprise at least 15 percent of the district’s enrollment and the district has at least 50 EL students.) Beginning in 2024‑25, COEs are required to establish student advisory committees if they had not had one established or do not have two positions for students on the parent advisory committee. The advisory committees can review and comment on the proposed plan. COEs must respond in writing to the comments of the advisory committees. COEs also are required to notify members of the public that they may submit written comments regarding the specific actions and expenditures proposed in the LCAP. The LCAP must include a description of how the COE engaged with educational partners, and describe how the engagement resulted in changed to goals and actions set forth in the LCAP.

LCAPs Must Include an LCFF Budget Overview for Parents. Beginning in 2019‑20, COEs must include in their LCAPs a short summary for parents. This summary must include projected total revenue for the upcoming fiscal year (including LCFF and other state, local, and federal funding), projected expenditures, and budgeted expenditures for planned actions and services. The summary must also specify how much of the COE’s total LCFF funding is projected to be from supplemental and concentration grants, and provide estimates of current‑year expenditures to increase or improve services for ELs, low‑income students, and foster youth. Beginning in 2024‑25, the overview must contain plans on how funding from the Student Support and Enrichment Block Grant will be spent. In addition, the overview must contain a brief description of the activities or programs supported by general fund expenditures that are not included in the LCAP.

CDE Must Review and Approve a COE’s LCAP. Each COE must submit its LCAP to CDE for review. (School districts submit their LCAPs to COEs and charter schools submit their LCAPs to their authorizing school district or COE.) The department must approve a COE’s LCAP if it determines that (1) the LCAP adheres to the required template, (2) the COE’s budgeted expenditures are sufficient to implement the strategies outlined in the LCAP, and (3) the LCAP adheres to the expenditure requirements for supplemental and concentration funding. As part of its review, the department can then seek clarification from the COE about the contents of its LCAP. If the department seeks such clarification, the COE must respond in writing. Based on a COE’s response, the department can submit recommendations for amendments to the LCAP back to the COE. The COE must consider any of the department’s recommendations at a public hearing, but the COE is not required to make changes to its plan. The annual deadline for approval or rejection of a COE’s LCAP by the department is October 8.

Other Reporting

Required Plan for Supporting School Districts in Continuous Improvement. Chapter 32 established a requirement for county superintendents to prepare a summary of how the COE plans to assist all school districts within the county. The plan describes actions the COE will take in approving all LCAPs. The plan also describes actions the COE will take to provide assistance to school districts identified for differentiated assistance and how it will support other districts in moving further ahead in their LCAP goals. COEs are also to report goals and an expenditure plan for providing this assistance. By November 1 of each year, CDE is to compile COE descriptions of the support they are providing and post them in a single document on the CDE website.

COEs Have Reporting Requirements for Specific Categorical Programs. Many COEs participate in categorical programs that provide funds for specific purposes. These programs each have specific reporting requirements. For example, if a COE operates a State Preschool program it must submit annual information on spending and program enrollment.

2023‑24 Budget Package Requires State Actions Related to Juvenile Court and County Community Schools. Trailer legislation included in the 2023‑24 budget package adds three requirements relating to juvenile court and county community schools. Specifically, the budget package requires:

- Additional Statewide Reporting. Beginning in 2024‑25, CDE will be required to report additional information for students in juvenile court and county community schools on a statewide, countywide, and school level basis. This information includes: (1) the number and percentage of students who leave juvenile court or county community schools without a high school diploma or equivalent and subsequently enroll in a school district or charter school; (2) the number and percentage of students enrolled in a juvenile court or county community school without a high school diploma or equivalent and do not transfer to another public school; (3) access to and completion of A‑G approved courses, high school equivalency tests, and accredited college coursework; and (4) a summary of outcomes aligned with the California School Dashboard indicators for students served by COE alternative schools, with the ability to display information by all juvenile court schools, or by all county community schools.

- An Evaluation of Juvenile Court and County Community Schools. CDE is required to contract for an independent evaluation of juvenile court and county community schools and provide a report to the Legislature and administration by November 1, 2025. The report is to include a number of components, including an analysis of state and federal funding available for these schools and a sample cost‑sharing agreement between COEs and county probation departments.

- Convening of a Workgroup for Students With Disabilities. CDE is required to convene a workgroup to examine existing law and current practices around the education of students with disabilities enrolled in juvenile court schools and county community schools, and provide a report to the Legislature and administration by February 25, 2025. This report is to include recommendations for improvements on several aspects, such as timely transfer of pupil records to and from county juvenile court schools and collaboration between COEs and other agencies.

Assessment

In this section, we provide our assessment of the transparency of COE budgets and plans. Our assessment was based on a review of COE LCAPs and other budget documents, as well as interviews with COE staff and other experts in COE spending and programs.

COE Budgets

COE Budgets Can Be Difficult to Interpret. Reviewing a COE’s overall revenues and expenditures does not provide helpful context for understanding the ways COEs choose to spend their discretionary funding. COE budgets often include significant amounts of revenue for which COEs simply pass through funding to school districts and other local governments. (For example, with special education funding that is transferred to school districts and certain local property tax transferred to trial courts.) In addition, COEs conduct a wide range of activities with LCFF—their primary state funding source. As such, overall budget documents do not separate out funding based on specific activities, such as direct services to students and district support. Given these issues, the Legislature cannot determine from budget documents if unique aspects of COE funding and spending are due to pass‑through funding or because of the COE’s specific role within the county.

Many COEs Provide High‑Level Summaries of Spending to Their Boards. Based on our conversations with COE staff, most COEs provide high‑level information on the entirety of their budgets to their superintendents and county boards of education. These high‑level summaries are intended to provide leadership with a sense of the various activities that COEs conduct. Given there is no state requirement for how to display this information, COEs take different approaches in categorizing their spending. For example, some COEs distinguished between required and optional activities, while others focused on whether spending was directly benefitting students or supporting school districts.

COE LCFF Funding Provides Significant Degree of Flexibility. COE LCFF funding is unique in that it has two components intended to address two distinct activities (operating juvenile court and county community schools and providing district support), while also allowing COEs to use the funding for any purpose. This means that COEs can spend funding generated based on juvenile court school programs on district support, and vice versa. COEs may also use their LCFF funds for other activities, such as offering career technical education classes to students in the county. This flexibility provides COEs with a great deal of discretion to determine what activities would be of most benefit in their county and results in significant variation across the state. However, this flexibility also makes state oversight of COE activities more difficult.

Juvenile Court and County Community Schools

LCAP Overview for Parents Can Be Difficult to Interpret. Although intended to provide greater context to the spending described in the LCAP, the required overview for parents can be difficult to interpret. The first figure included in the template—Projected Revenue by Fund Source—shows the COE’s overall LCFF (including supplemental and concentration funding) as a share of total revenue. The figure, however, includes pass‑through funding not spent by the COE and does not disaggregate how much of the LCFF funding they receive is from the alternative grant, operations grant, or from the hold harmless funding. The second figure—Budget Expenditures in the LCAP—shows the share of total COE expenditures included in the LCAP. Since only the spending on juvenile court and county community schools is included in COE LCAPs—and COEs receive more funding through their operations grant—a very small portion of LCFF funding is typically shown to be included. Rather than helping provide context for parents, the documents raise questions as to why such a small share of LCFF funding is included in the LCAP, even though COEs are complying with the requirements. Displaying total COE revenues and expenditures—including funding for district support and funding that is passed through to districts—makes it more challenging to assess spending specifically related to juvenile court and county community schools. This issue is unique to COEs, as school districts primarily spend funding on services to students and do not have such a large share of spending that is passed through to other entities. By including all revenues in the totals, the summary makes it more challenging to see how COE spending on juvenile court and county community schools compares with the amount they receive from the alternative education grant and other funding specifically for these programs.

Interest in Understanding Overall Alternative Education Spending. In our conversations with COEs, they indicated that many educational partners are particularly interested in understanding the current services that are available for students and whether these services are consistently provided. For example, parents may be interested in knowing whether their child will be able to receive counseling services, the types of courses the student can access at a court school, and whether a student with a high school diploma would have access to higher education. These questions are likely common because students are enrolled in these schools on short notice and juvenile court schools are not as accessible to parents as a traditional school. The spending in the LCAP, however, focuses on new spending and does not comprehensively describe services available to students. Moreover, some services that students receive may not be included in the LCAP because they are funded by county government or other external entities. (For example, facilities costs and other services for juvenile court schools that are covered by county probation departments.) The LCAP template includes a “general information” section that provides a space for COEs to describe their schools and the students they serve. COEs sometimes use that section to more broadly describe available services for students. The template also includes a section for COEs to summarize their spending that is not included in the LCAP. COEs are not required to share any specific details in either of those sections, so the level of detail varies by COE.

Given COE Student Population, Distinction Between Base Program and Increased and Improved Services Seems Arbitrary. The increased and improved services section is intended to demonstrate how a COE plans to use supplemental and concentration grant increases to increase or improve services for students generating the additional funding. Creating a distinction between specific student groups and all students, however, is difficult given the vast majority of COE students are in one of these three categories. All juvenile court school students are categorically considered low income and generate supplemental and concentration funding. For county community schools, 82 percent of students statewide in 2023‑24 are ELs, low income, or foster youth. Moreover, virtually all students in both settings enter COE‑run schools with significant needs. Given the needs of these students, COEs are typically integrating additional supports within their base program. Requiring separate reporting creates an arbitrary distinction that is not consistent with COE operations. COEs also are already required to include goals and actions to address the needs of their lowest‑performing subgroups in other sections of the LCAP. For example, they must set focused goals for the lowest‑performing subgroups in all schools receiving equity multiplier funding.

Required COE Metrics Not Particularly Relevant for Assessing Quality of Programs. Given the student population that COEs serve, the existing state‑required metrics are not well suited to assessing the quality of their educational programs. Students typically have relatively short stays and can enroll in these schools at any point in the year. In 2022‑23, 75 percent of juvenile court and county community schools were considered “nonstable”—they are enrolled at their school for less than 245 continuous days or leave the school due to truancy or expulsion. This is compared with 8.8 percent of students statewide who are considered nonstable. This data is consistent with our conversations with COEs, in which they indicated that their students are typically enrolled for short periods of time, particularly for juvenile court schools. Given these short stays, the four‑year graduation rate metric is not a particularly useful metric for assessing a juvenile court or county community school. (Schools, however, are required to report this metric for federal accountability purposes.) Moreover, given the high degree of mobility, only a small share of students are enrolled long enough to take the standardized tests in math and English language arts. In addition, many students are significantly behind grade level and will show low performance on the standardized tests, even if they made substantial academic progress while they were enrolled in the juvenile court or county community school. Although not required, many COEs use local metrics to monitor their own progress based on short‑term measures of performance, including the number of credits students earn and whether students successfully transition back to their traditional schools. The challenge of finding useful metrics is not unique to COE‑run programs. This also applies to other schools operated by school districts and charter schools that are designed to serve students who are behind on credits and are at risk of dropping out.

LCFF Operations Grant and Hold Harmless Funds

COEs Regularly Communicate With School Districts Regarding Available Support Activities. Many COEs meet with school districts or have public meetings to communicate to local partners the support activities that are offered. These meetings are also forums for COEs to obtain feedback on school district needs. Several COEs put together annual reports or strategic plans to enhance this communication and transparency locally.

Little Transparency for How LCFF Operations Grant and Hold Harmless Funds Are Spent. Most state categorical and federal funds that COEs receive have specific spending restrictions and reporting requirements. For example, COEs that operate a State Preschool program must report enrollment and expenditure information to CDE and spend the associated funds on the State Preschool program. Conversely, the operations grant and hold harmless components of the LCFF have no reporting requirements and are unrestricted, which means the state knows very little about how these funds are spent. Although COEs provide unaudited expenditure data annually, this information cannot answer important questions, such as the level of funding and activities provided for district support, or the degree to which COEs use these funds to provide services to students across the county. The annual expenditures also do not distinguish the operations grant and hold harmless funding from the alternative education grant. Moreover, unlike school district LCFF and the alternative education grant included in the COE LCFF, there are no broad requirements to submit a plan or describe how the operations grant and hold harmless funding is being spent, nor do COEs have to report on any outcomes associated with these funds. The lack of information makes it difficult for the Legislature to assess whether the amount of funding provided to COEs is aligned with state requirements and expectations.

Recommendations

In this section, we describe our recommendations for improving transparency of COEs’ spending. Specifically, these recommendations are intended to provide greater clarity around each COE’s major activities and services, better monitor spending and outcomes through the LCAP, and increase transparency regarding how LCFF operations grant and hold harmless funding is spent.

Require an Annual Report That Describes Major COE Activities. We recommend requiring COEs to publish a report annually at the start of each school year that includes a narrative of the major activities and services COEs conduct. This would allow state and local partners to understand at a high level the key work COEs do to support districts and students, and provide an opportunity for COEs to describe the specific role they play in their region. This report would include any major activities or priority initiatives, regardless of funding source. The report would also include a description of the various ways the COE serves in a statewide or regional role, such as operating as a geographic lead or operating countywide State Preschool programs. We recommend providing COEs with flexibility in determining the format and content of this report. This would allow them to better explain their mission and key goals for the academic year.

Limit Funding in Overview for Parents to Alternative Education Grant and Related Funds. We recommend the revenues and expenditures listed in the overview for parents be limited to those related to funding from the alternative education component of the LCFF (including minimum grant funds), the Student Support and Enrichment Block Grant, and equity multiplier. Under this approach, it would be easier to see how the funding COEs receive based on their juvenile court and county community schools compares with the costs of operating these programs.

Require LCAP Include Description of Services and Courses Students Can Access. We recommend requiring that, in the general information section of the LCAP, COEs be required to include a description of services available to students and the range of courses that students can access. The services provided would include those funded outside the LCFF, as well as partnerships the COEs have with external entities that provide services to students. COEs could describe the courses that students can access, including career technical education courses, or A‑G courses. COEs could also describe whether they partner with a community college to provide access to dual enrollment for students. This would allow state and local partners to understand at a high level the existing programs and services to students, in addition to the new spending included in the LCAP.

Eliminate the Increased and Improved Services Section. We recommend eliminating the increased and improved services section of the LCAP. Virtually all students enrolled in juvenile court and county community schools are students with high needs, and COEs are providing additional support through their base program. COEs would still report the actions they are taking to achieve goals around state priority areas. Most COEs also would still be required to set focused goals for equity multiplier schools and schools with low‑performing subgroups on the School Dashboard. This action would shorten the LCAP by eliminating a section that is duplicative of other portions of the plan. Implementing this change would require modifying statute to exclude COEs from the requirements associated with tracking increased and improved services within the LCAP.

Establish Set of COE‑Specific Outcome Metrics. We recommend that state reporting requirements for these schools include academic performance data that measure how well they serve short‑term students. The state could take a variety of approaches to measuring outcomes for students at juvenile court and county community schools. Two promising metrics that many schools already use include (1) scores on pre‑ and post‑tests of skills, and (2) credits gained while enrolled. Various pre‑ and post‑tests exist and currently are used by some COEs. Should the Legislature choose to adopt pre‑ and post‑tests as a state‑required performance measure, we recommend the state approve a specific set of tests and require that schools select their tests from the approved list. This would allow the state to compare the short‑term academic progress of students across juvenile court and county community schools. The number of credits gained while at a juvenile court or county community school is another short‑term academic measure that would provide the state with valid information about students’ academic progress and whether alternative schools are meeting their primary objective of helping students overcome credit deficiencies. The state could consider soliciting input from COEs and other experts on alternative education or other relevant outcome metrics that could be added to the Dashboard that would be a better indication of performance at COE‑run schools. We recommend that any metrics take into consideration the amount of time that students are enrolled. (For example, by displaying the average number of credits gained for each 15‑day period of enrollment.)

Require Expenditure Information on LCFF Operations Grant and Hold Harmless Funding. In addition to the annual report, we recommend COEs develop a report specifically on how the LCFF operations grant and hold harmless funding was spent. These reports should be publicly available on COE websites six months after the close of the fiscal year and should disaggregate spending by the following categories:

- Oversight and Support. This would include any district support or oversight activities COEs conduct. Examples of activities that would fall in this category would be fiscal oversight, academic oversight and support, business and information technology services, or training of district staff.

- Juvenile Court and County Community Schools. This would include any operations grant or hold harmless funding used to support juvenile court and county community schools.

- Direct Services for Students Not Enrolled in Juvenile Court and County Community Schools. This would include spending on career technical education, adult education, preschool, and other programs that are directly provided to students enrolled in school districts and charter schools within the county.

COEs also should be required to include spending from their alternative education grant, if those funds are not used for students enrolled in juvenile court and county community schools. We recommend COEs be required to report this expenditure information in a format that is comparable across the state. The Legislature could add subcategories of spending to address specific interests. For example, the Legislature could require disaggregating oversight and support spending based on whether the activity is required by law or optional. The Legislature could also require spending on services for students be disaggregated by program type (career technical education, special education, et cetera).

Make Continuous Improvement Report Publicly Available. We find value in the information COEs are providing in the current required continuous improvement report per Chapter 32. We recommend these reports be made publicly available in their entirety. Currently CDE compiles COE descriptions of support they are providing. Based on our conversations with COE staff, it does not seem to be major workload to post these plans since they are already being developed.