LAO Contact

April 24, 2024

California's Child Welfare System:

Addressing Disproportionalities and Disparities

- Introduction

- Background

- Inherent Challenges of the Child Welfare System

- Disproportionalities in Child Welfare

- High‑Level Factors Contributing to Disproportionalities

- Front‑End Policies Impacting Child Welfare System Involvement

- Options to Begin to Address Disproportionalities

- Conclusion

- Appendix: Selected References

Executive Summary

Child Welfare System Serves to Keep Children Safe and Strengthen Families. When children experience abuse or neglect, the state provides a variety of services to protect children and strengthen families. The state provides prevention services—such as substance use disorder treatment and in‑home parenting support—to families at risk of child removal to help families remain together, if possible. When children cannot remain safely in their homes, the state provides temporary out‑of‑home placements through the foster care system, often while providing services to parents with the aim of safely reunifying children with their families. If children are unable to safely return to their parents, the state provides assistance to establish a permanent placement for children, for example, through adoption or guardianship. These various services constitute the state’s child welfare system.

Child Welfare System Intervention May Be Necessary for Child Safety, but Also May Result in Additional Trauma. Families who come to the attention of the child welfare system often are experiencing poverty and other significant challenges, such as substance use disorder or domestic violence, which can cause trauma to the children and family. Given the shorter‑ and longer‑term negative impacts of experiencing trauma and maltreatment, child welfare system intervention may be necessary to help keep children safe from these potentially harmful situations. At the same time, involvement with the child welfare system also may result in trauma, particularly when a child is removed from their parent(s) or caregiver(s). How best to ensure child safety in a way that minimizes and mitigates trauma and ideally keeps the child with their parent(s)/caregiver(s) is a core challenge inherent to the child welfare system.

California’s Child Welfare System‑Involved Families Are Disproportionately Black, Native American, and Low Income. Black and Native American children are significantly overrepresented in California’s child welfare system relative to their shares of California’s child population. Moreover, these children and their families tend to have worse child welfare outcomes, such as longer time spent in out‑of‑home care and higher likelihood of termination of parental rights. In addition, most families involved with the child welfare system are experiencing poverty or otherwise facing significant economic hardship. These demographic and outcome trends have persisted for many years. Understanding which California communities and families are impacted at disproportionate rates—and the possible reasons why—can help the Legislature consider which policy interventions may be most effective at addressing these disproportionalities and disparities.

Drivers of Disproportionalities Are Complex. The causes of the disproportionalities and disparities across California’s child welfare system are complex and nuanced, reflecting challenges and risk factors that certain groups are more likely to experience. Research finds that the presence of risk factors can create stressors and result in conditions wherein maltreatment is more likely to occur. Importantly, however, the presence of risk factors alone does not mean maltreatment will occur, and families also may benefit from the presence of protective factors. How to differentiate between families in need of supports to address risk factors, as opposed to families who require child welfare system‑level intervention, is an inherent challenge for decision makers across the child welfare system. This report describes some broader, high‑level social and economic factors—beyond the child welfare system itself—that may contribute to why certain racial/ethnic groups are disproportionately represented in the child welfare system today. In particular, we focus on poverty and correlated risk factors, which certain groups are more likely to experience as a result of historical polices and other factors. We also examine certain groups’ disproportionate exposure to mandated reporters, as well as the role that implicit bias may play in reporting and decision‑making.

Front‑End Policy Areas Impacting Child Welfare System Involvement. In identifying policy levers that can help address disproportionalities and disparities, this report focuses on decision‑making and policies at the “front‑end” of the system. We define front‑end as all policies and decision points prior to and including a social worker’s decision to remove a child and place them into foster care. Thus, this definition includes services and supports for families prior to allegations of maltreatment, as well as protocols and decisions around reporting, investigating, and substantiating allegations, and possible removal and foster care placement. We focus on these areas because addressing front‑end system issues could help mitigate the growing disparities at later stages of the system. In addition, a number of recent legislative actions already have aimed to address challenges at later stages of the system.

Options to Begin Addressing Front‑End Disproportionalities and Disparities. We lay out a number of options for the Legislature to consider, all while aiming to continue ensuring child safety is prioritized while mitigating trauma and preventing unnecessary child welfare system involvement. Given the complex and interwoven factors contributing to disproportionalities and disparities, addressing them will require broad efforts both across the child welfare system and policy areas external to the system. Many of the options would introduce new costs. Accordingly, the Legislature would need to consider the fiscal implications and associated trade‑offs.

Introduction

Child Welfare System’s Primary Goal Is to Keep Children Safe. The child welfare system serves to protect children from maltreatment—including by removing children from their home and placing them into temporary foster care when deemed necessary—and to strengthen families so that children can remain safely with their families whenever possible. When responding to allegations of maltreatment, social workers use a variety of tools and training to assess the child’s safety on a case‑by‑case basis, determining whether or not a child can remain safely at home.

California’s Child Welfare System‑Involved Families Are Disproportionately Black, Native American, and Low Income. Black and Native American children are significantly overrepresented in California’s child welfare system relative to their shares of California’s child population. Moreover, these children and their families tend to have worse child welfare outcomes, such as longer time spent in out‑of‑home care and higher likelihood of termination of parental rights. In addition, most families involved with the child welfare system are experiencing poverty or otherwise facing significant economic hardship. These demographic and outcome trends have persisted for many years.

This Report Examines Front‑End Disproportionalities and Disparities. Disproportionalities persist at all levels of the child welfare system, alongside disparities in outcomes. A disproportionality occurs when a group’s percentage in a target population (for example, California’s child welfare population) differs from that group’s percentage in the base population (for example, the state of California), while disparities refer to groups experiencing inequities relative to one another (for example, children of different racial/ethnic groups experiencing different outcomes). This report focuses on disproportionalities and disparities at the front end of families’ involvement with the child welfare system—that is, allegations, investigations, substantiations, and decisions to place a child in foster care—as well as families’ circumstances prior to system involvement. We focus on these areas as the subject of this report because addressing front‑end system issues could help mitigate disparities at later stages of the system, which are greater. In addition, a number of recent legislative actions already have aimed to address challenges at later stages of the system.

Roadmap for This Report. After providing background on the child welfare system and recent areas of legislative focus, this report examines some of the complex factors contributing to the pervasive disproportionalities and disparities across California’s child welfare system. The report then identifies specific policy and implementation areas that may be contributing to front‑end disproportionalities and disparities. Finally, the report presents options for the Legislature to consider to begin to help address disproportionalities and disparities, while maintaining a system that ensures and prioritizes the safety and well‑being of children.

Background

Child Welfare System Overview

Child Welfare and Foster Care Programs Serve to Keep Children Safe and Strengthen Families. When children experience abuse or neglect, the state provides a variety of services to protect children and strengthen families. The state provides prevention services—such as substance use disorder treatment and in‑home parenting support—to families at risk of child removal to help families remain together, if possible. When children cannot remain safely in their homes, the state provides temporary out‑of‑home placements through the foster care system, often while providing services to parents with the aim of safely reunifying children with their families. If children are unable to safely return to their parents, the state provides assistance to establish a permanent placement for children, for example, through adoption or guardianship.

California’s Child Welfare System Serves Nearly 100,000 Children and Their Families in Any Month. In 2023‑24, the estimated average monthly caseloads for various child welfare system service components include:

- 32,000 in‑person investigations, in response to maltreatment allegations.

- 13,000 children with families receiving family maintenance services to help keep children safely at home.

- 17,000 children in foster care whose families are receiving reunification services.

- 33,000 children in foster care for whom the child welfare system is working toward permanent placement.

In addition, many families participate in voluntary family strengthening programs through the child welfare system or community‑based organizations, which is not captured by these caseload figures. The child welfare system also provides monthly maintenance payments to children in adoptive and guardianship placements, which are not included in the above figures.

California’s Child Welfare System Is Locally Implemented, With Requirements and Oversight From State and Federal Governments. Local child welfare agencies implement child welfare programs on behalf of the state Department of Social Services (DSS), with oversight from the state and federal governments. Local agencies include county child welfare departments, county probation departments, and certain tribes. (We will refer to the various types of local child welfare agencies as “counties” throughout this report for simplicity.) Funding for child welfare programs comes from the federal and state governments, along with local funds. The federal and state governments set standards in terms of the service components that all local child welfare agencies must implement and oversee the quality of service delivery.

Child Maltreatment May Take the Form of Abuse or Neglect. “Maltreatment” refers broadly to any action or failure to act by a caregiver that puts a child at risk of or results in serious physical or emotional harm. Federal law outlines minimum definitions of what constitutes child maltreatment, but leaves more detailed definitions and legislation to states. California law specifies treatment constituting physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect (both general neglect and severe neglect). Specifically, Section 300 of the Welfare and Institutions Code describes the circumstances under which children may come under the jurisdiction of the California juvenile court, while Sections 11165.1‑11165.6 of the Penal Code describe the acts and omissions that comprise different types of child abuse and neglect. The box below provides an overview of the definition of maltreatment focused on neglect, as that is a primary focus of this report.

California’s Definition of Neglect, One Form of Child Maltreatment

State statute defines various types of child abuse and neglect, which include parent/caregiver actions or failures to act resulting in serious physical or emotional harm or illness (or substantial risk of such harm or illness). In particular, statute defines neglect as due to:

- The failure or inability of the child’s parent or guardian to adequately supervise or protect the child.

- The willful or negligent failure of the parent or guardian to provide the child with adequate food, clothing, shelter, or medical treatment.

- The inability of the parent or guardian to provide regular care for the child due to the parent’s or guardian’s mental illness, developmental disability, or substance abuse.

Statute also specifies that certain circumstances in and of themselves do not amount to abuse or neglect:

- Homelessness or the lack of an emergency shelter for the family.

- The failure of the child’s parent or alleged parent to seek court orders for custody of the child.

- Indigence or other conditions of financial difficulty, including, but not limited to, poverty, the inability to provide or obtain clothing, home or property repair, or child care.

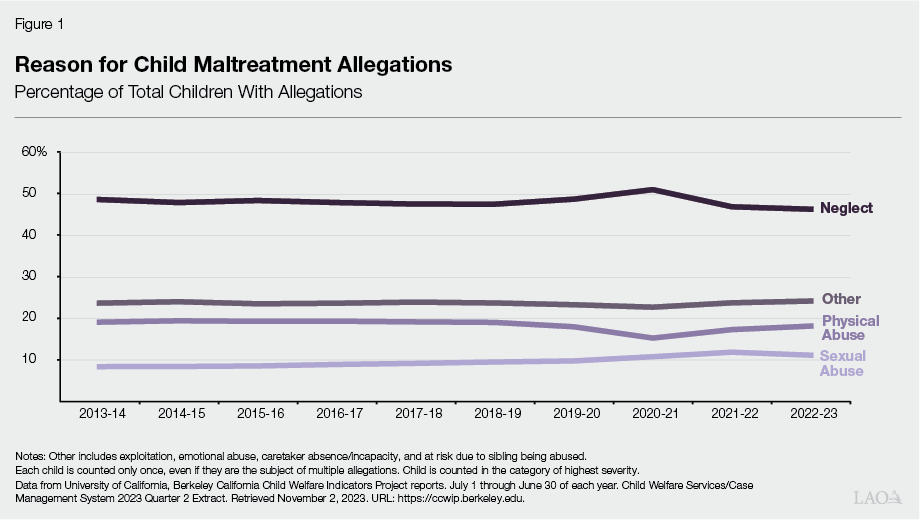

Neglect Is Most Common Type of Maltreatment Allegation. A near majority of maltreatment allegations—and ultimately the vast majority of placements into foster care—are due to neglect rather than due to physical or sexual abuse or another reason. This has long been the case, as illustrated by Figure 1. This trend is more pronounced for foster placements: more than 80 percent of foster placements over the past decade have been due to neglect.

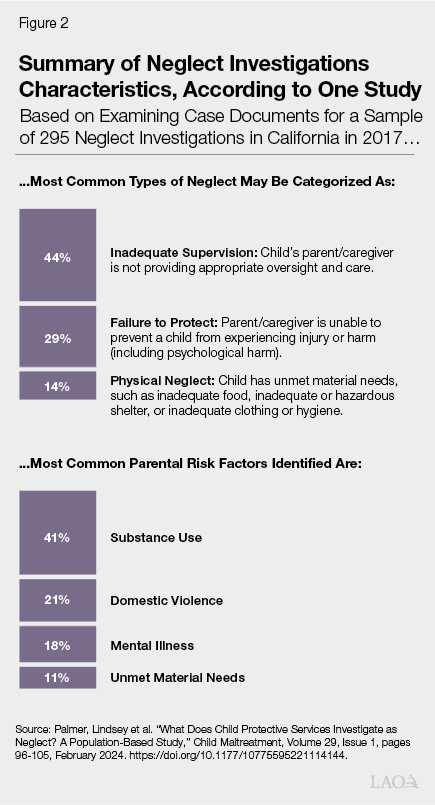

Given that most child welfare cases involve the broad category of neglect, a recent study sought to characterize various types of neglect and define the factors most commonly associated with neglect. Based on examining narrative reports written by social workers and other case file information for a representative sample of 295 neglect investigations in California in 2017, the study identified common types of neglect as inadequate supervision, failure to protect, and physical neglect. Common parental risk factors in these investigations included behavioral health needs, domestic violence, and economic/material need. The study’s findings are summarized in Figure 2.

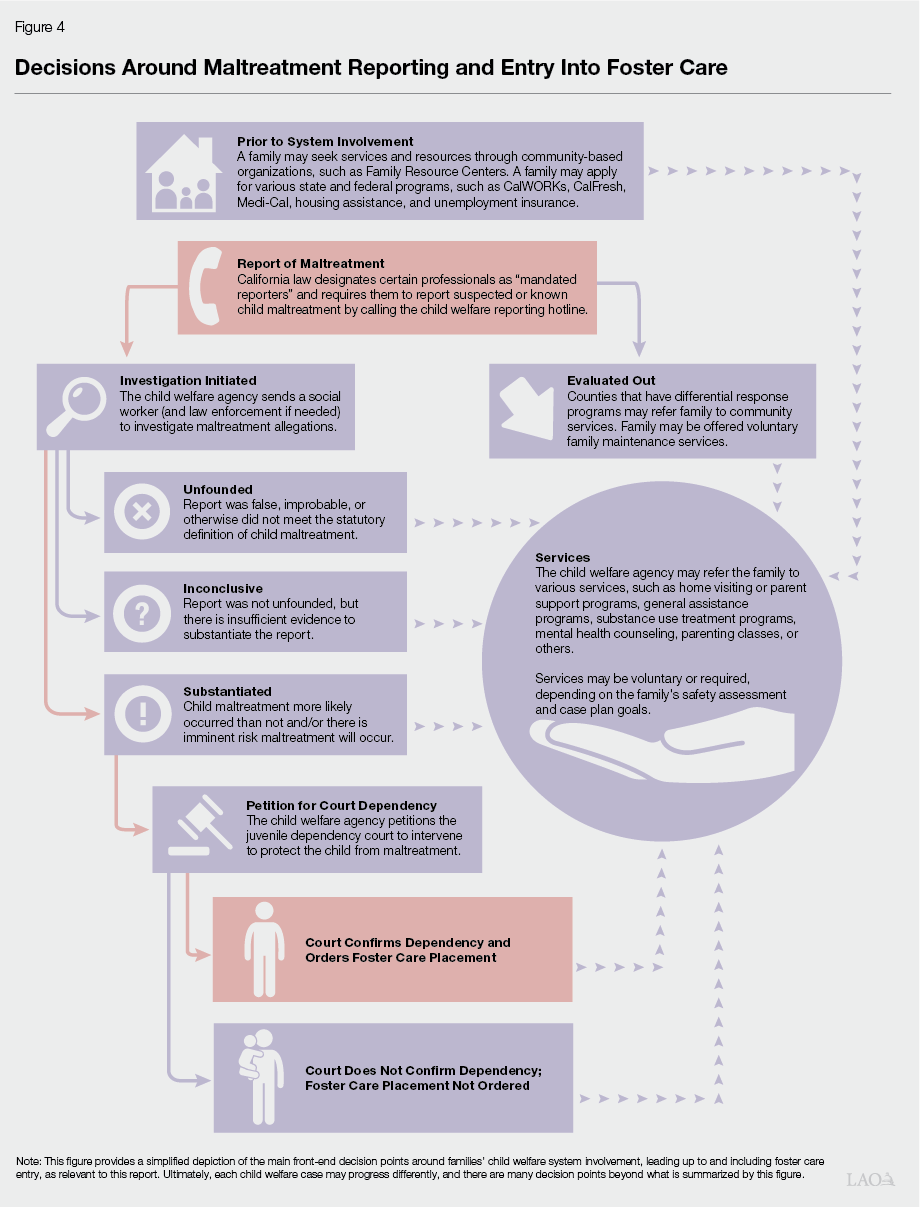

Suspected Maltreatment Is Reported to Local Child Welfare Agencies, Which Investigate Allegations and Determine Next Steps. California’s counties operate child welfare hotlines, which receive reports of suspected maltreatment. Once an allegation of suspected maltreatment is reported, child welfare social workers decide whether the allegation merits investigation along with appropriate next steps. In making these decisions—along with other decisions throughout a family’s involvement with the child welfare system (including foster care)—social workers across all counties use their professional training and knowledge and employ standardized decision‑making tools, which are designed to help social workers navigate child welfare system decisions in a more uniform manner across cases. Decisions also may be reviewed collaboratively with other social workers and supervisors.

Substantiated Investigations Can Result in Support Services to Families and Possibly Foster Placements. For roughly three‑quarters of children with allegations, the allegations result in an in‑person investigation from a social worker. In roughly 20 percent of those investigations, social workers determine that maltreatment is more likely than not to have occurred or that the child faces substantial risk of harm—this is referred to as substantiation. Substantiated cases generally follow one of two possible paths: (1) services and monitoring while the child remains at home if it is determined it is safe to do so (for around 60 percent of substantiations), or (2) foster care placement (for around 40 percent of substantiations). These two paths are described in additional detail in the next paragraphs.

Counties May Provide Preventative Services and Access to Other Supports in Lieu of Removing a Child. Counties may offer a variety of services to families with substantiated maltreatment allegations aside from foster placement, as long as social workers determine the child can remain safely in the home with intervention. Below, we describe some of these programs. Importantly, access to these programs may be obtained only after a family has been the subject of an allegation of child maltreatment.

- Family Maintenance (FM). The FM program offers time‑limited protective services to families whose children are at potential risk of maltreatment, but for whom the county/court has determined the children can safely remain in the home. Specific services are detailed in the child’s case plan and the county oversees a family’s progress. Services may include, for example, counseling, parent training, transportation, emergency shelter care, respite care, and more. FM is a core child welfare services component required to be provided by all counties; however, specific services vary across counties. FM services may be offered to a family on a voluntary basis at any point of a family’s child welfare system involvement, or may be court mandated as a condition of a child remaining in the home.

- Differential Response (DR). After assessing an allegation and finding a family is at relatively low risk, rather than offering services through the child welfare system, counties may opt to refer families to community‑based organizations, such as Family Resource Centers, as described in more detail in the box below. DR, also referred to as alternative response, is an optional service element and currently 38 counties operate a DR program.

Family Resource Centers (FRCs)

FRCs are defined in California statute as community‑based organizations with the goal of preventing child maltreatment and strengthening families. An FRC may be located in, or administered by, different entities, such as a local educational agency or a community/neighborhood resource center. California has nearly 500 FRCs, which are funded in a variety of ways, including through philanthropy and local grants. Recent state funding in response to the pandemic also supported FRCs: around $15 million General Fund was provided across the 2019‑20, 2020‑21, and 2021‑22 budget years. Because FRCs aim to serve their direct communities, services offered vary center by center, but may include services such as parenting classes and support groups, one‑on‑one counseling and support, emergency assistance, child care, and access to behavioral health programs and supports.

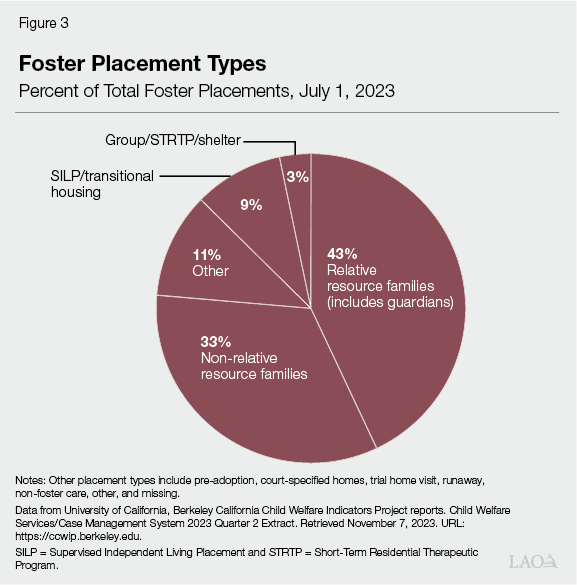

Substantiated Allegations May Result in Foster Placement. When a county substantiates an allegation and determines that the child cannot remain safely in the home, the county may remove the child from the custody of the parent(s)/caregiver(s) and place the child into foster care. (A juvenile court ultimately must confirm the maltreatment allegation, but prior to a court hearing, a county may place a child into foster care on an emergency basis.) Depending on the needs of the child, foster placement may be with a resource family (formerly known as foster families in California), in a congregate care setting (a more group‑like setting), or in a more independent placement for older youth. State and federal policies over time increasingly have aimed to place youth with resource families (or more independent placements for older youth) and to reserve congregate care placements for youth whose behavioral health needs are unable to be met in a home‑based setting. In particular, state and federal policies prioritize placements with a child’s relatives or kin when possible, based on research finding that these placements tend to be more stable and are more likely to help a child achieve positive well‑being outcomes. Figure 3 shows the distribution of foster youth across placement types.

Figure 4 summarizes the processes around child maltreatment allegation reporting and social worker response and decision‑making leading up to and including foster care placement. The figure depicts a simplified overview; each case may progress through the process differently. Importantly, there continue to be many decision points beyond what is summarized by this figure, such as case planning and decisions around reunification or permanent placement. However, this figure illustrates the main front‑end process as relevant to this report.

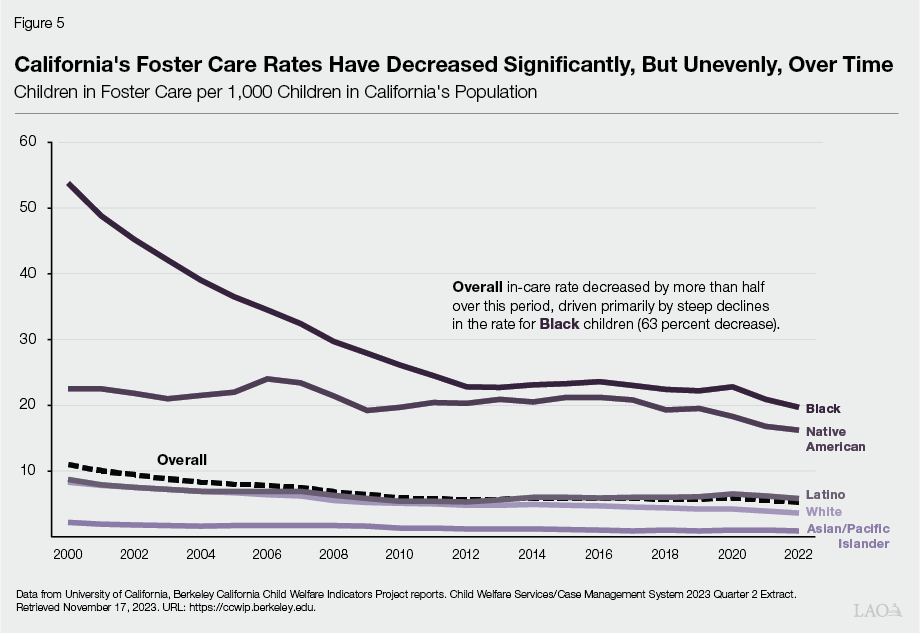

Number of Youth in Foster Care Has Decreased Over Time… Figure 5 illustrates how the rate of children in foster care (compared to total children in California) has changed over the past couple of decades and compares these rates for different racial/ethnic groups. As shown, the overall rate of children in foster care has decreased by more than half. This is primarily driven by steep declines for Black children (63 percent decrease), while changes for other racial/ethnic groups have been smaller. (In particular, the rate of Native American children in foster care decreased the least of all racial/ethnic groups [28 percent].)

…Driven By Various Policy and Practice Changes. Various factors have contributed to these decreases across groups, such as federal policy changes limiting the amount of time children can remain in foster care. Notably, the policy and practice changes that have resulted collectively in the decreases shown in Figure 5 have done so by increasing exits from care more so than by reducing entries. Overall, these trends demonstrate that policy choices over time have had an impact on disproportionalities and disparities in California’s foster care system, and illustrate that further reducing entries into care—that is, focusing on the front‑end of the system—may be an important area for additional reform.

Child Welfare Funding

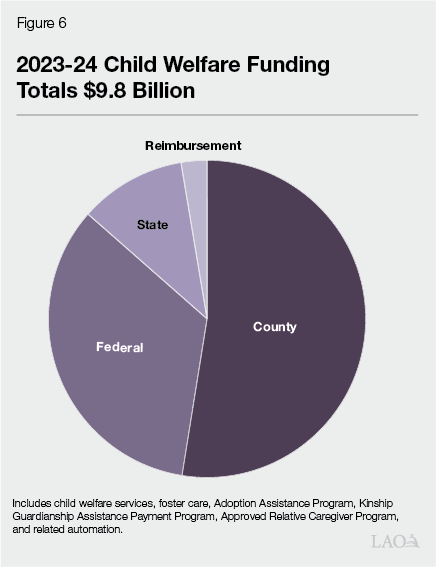

California’s Child Welfare System Is Funded by a Mix of Federal, State, and Local Funds. The state’s diverse array of child welfare programs is funded by federal, state, and local funds, as illustrated by Figure 6. The proportional mix of funds used to fund any particular child welfare payment or service varies depending on whether a family is eligible for federal financial participation (a determination generally based on the income of the family from which a child was removed in foster care cases). Furthermore, the cost of services and supports may vary greatly based on the needs of the individual child and family (and whether the family is participating in Family Maintenance or the child has been placed into foster care). For example, in 2023‑24, the estimated average monthly assistance payment for foster care across all placement types is around $3,000, although for an individual child that payment may range from around $1,200 to more than $16,000 depending on where a child is placed and the level of care needed. In addition to the monthly assistance payment amount, other costs related to the child and parents’ needs may include, for example, Medi‑Cal coverage for behavioral health services.

Federal Funding. When a family requires child welfare services or foster care, and that family meets federal eligibility standards based on income and other factors, states may claim federal funds for part of the cost of providing care and services for the child and family. State and local governments provide funding for the portion of costs not covered by federal funds, based on cost‑sharing proportions determined by the federal government. These federal funds are provided pursuant to Title IV‑E (related to foster care) and Title IV‑B (related to child welfare) of the Social Security Act. Other federal funding sources that California receives for child welfare purposes include some Temporary Assistance for Needy Families dollars and various federal grants (such as the Child Abuse Prevention Program and Promoting Safe and Stable Families Program).

2011 Realignment. Until 2011‑12, the state General Fund and counties shared significant portions of the nonfederal costs of administering child welfare programs. In 2011, the state enacted legislation and the voters adopted constitutional amendments (in 2012) known as 2011 realignment, which gave counties fiscal responsibility for child welfare. The legislation also dedicated a portion of the state’s sales and use tax and vehicle license fee revenues—along with a portion of the associated growth in these revenues—to counties to administer these programs (along with some public safety, behavioral health, and adult protective services programs). In addition to dedicated 2011 realignment dollars, counties also may choose to spend other local funds (such as county general fund resources) on child welfare programs. As a result of Proposition 30 (2012), under 2011 realignment, counties either are not responsible or only partially responsible for child welfare programmatic cost increases resulting from federal, state, and judicial policy changes. Proposition 30 establishes that counties only need to implement new state policies that increase overall program costs to the extent that the state provides the funding for those policies. Counties are responsible, however, for all other increases in child welfare costs—for example, those associated with rising caseloads. Conversely, if overall child welfare costs fall, counties retain those savings. Parameters set by realignment and Proposition 30 have resulted in the state choosing to implement many new child welfare program components as county options and consequently also result in California’s 58 counties making different implementation choices for child welfare programs.

Some Recent Major Initiatives

This section describes some policy areas of recent legislative focus. The policy areas described here are not inclusive of all of California’s major child welfare initiatives, but rather are those most relevant to this report.

Implementing Continuum of Care Reform (CCR). Beginning in 2012, the Legislature passed a series of legislation implementing CCR. This legislative package makes fundamental changes to the way the state cares for youth in the foster care system. Namely, CCR aims to: (1) end long‑term congregate care placements; (2) increase reliance on home‑based family placements, including those with relatives/kin; (3) improve access to supportive services regardless of the type of foster care placement a child is in; and (4) utilize universal child and family assessments to improve placement, service, and payment rate decisions. Under 2011 realignment, the state pays for the net costs of CCR, which include up‑front implementation costs. CCR is a multiyear effort—with implementation of the various components of the reform package beginning at different times over several years—and the state continues to work toward full implementation currently.

Accessing Federal Funds for Prevention Services. Historically, one of the main federal funding streams available for foster care—Title IV‑E—has not been available for states to use on services that may prevent foster care placement in the first place. Instead, the use of Title IV‑E funds has been restricted to support youth and families only after a youth has been placed in foster care. Passed as part of the 2018 Bipartisan Budget Act, the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) expands allowable uses of federal Title IV‑E funds to include certain evidence‑based and federally approved services to help prevent children and families from entering (or re‑entering) the foster care system.

California is in the process of implementing the state’s FFPSA program. In particular, the 2021‑22 budget provided $222 million for block grants to counties (on an opt‑in basis) to help them develop comprehensive prevention plans (CPPs) and begin implementing optional Title IV‑E prevention services, as well as any other non‑federally eligible prevention services they choose to implement. In developing CPPs, counties are required to conduct needs and capacity assessments, map current services and providers, define the specific prevention services they will implement and who the target populations will be, and more. Counties opting into the state block grant program were required to submit their CPPs to DSS in July 2023. As of January 2024, DSS had approved CPPs for 49 counties and 2 tribes (with 1 additional county’s plan still pending approval). Counties will continue to scope their programs and build the needed capacities in the coming years.

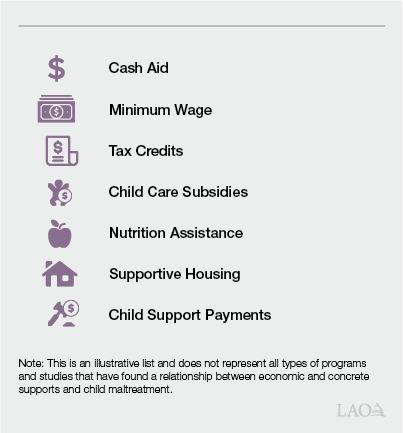

Improving the Economic Stability of Child Welfare Families. The Legislature has taken several budget actions and passed policy bills over the past few years that aim to improve the economic supports for child welfare system involved families. Some examples of recent legislative actions include: time‑limited cash assistance for families at risk of child removal, the creation of a new tax credit for former foster youth, policy changes to continue providing cash assistance to California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) families for six months after a child is removed, policy changes and additional funds to support relative caregivers, and policy changes to help older foster youth access Supplemental Security Income/State Supplementary Payment benefits. California also updated state policy to conform with federal guidance to allow more child support dollars to flow to families participating in reunification services.

Supporting Placements With Relatives. As noted, research finds that foster youth placed with family members or kin tend to experience more stability and better longer‑term outcomes than those placed in congregate care or with non‑relative foster families. Accordingly, a number of recent legislative actions and budget augmentations aim to support family members to be able to provide care for relative children who are placed into foster care. For example, Chapter 687 of 2021 (SB 354, Skinner) aims to reduce barriers for relatives to become resource families, while certain budget augmentations in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 aim to provide enhanced supports for finding and engaging relatives, home‑based placement options for foster youth with complex behavioral health needs, and case‑by‑case flexible funding for resource families to help sustain foster placements.

Clarifying Differences Between Neglect and Conditions of Poverty. In some cases, poverty can be mistaken for neglect. (We discuss this tension in more detail in the next section of this report.) For instance, a mandated reporter may make a report to the child welfare hotline based on observing a child who appears malnourished—which may or may not ultimately meet the statutory definition of reportable neglect. Given the potential to conflate poverty and possible neglect, some recent policy bills—namely, Chapter 770 of 2022 (AB 2085, Holden) and Chapter 832 of 2022 (SB 1085, Kamlager)—have focused on clarifying that experiencing poverty is distinct from child maltreatment, in particular general neglect. These bills, described in the box below, have amended relevant sections of the Welfare and Institutions Code and Penal Code accordingly.

Recent Bills Aim to Distinguish Poverty From Reportable Neglect

Chapter 770 of 2022 (AB 2085, Holden) clarified that a parent’s economic disadvantage in and of itself does not constitute neglect and added that “general neglect” entails a situation in which a child is at substantial risk of suffering serious physical harm or illness. Similarly, Chapter 832 of 2022 (SB 1085, Kamlager) prohibits a child from being found to be within the jurisdiction of the juvenile court solely on the basis of conditions of financial difficulty unless the court determines there is willful or negligent action or failure to act resulting in a substantial risk the child will suffer serious physical harm or illness. Stated legislative intent of these new laws is to: (1) decrease the number of unsubstantiated general neglect allegations that disproportionately impact Black and Native American children (AB 2085), and (2) ensure that families are not subject to the jurisdiction of the juvenile court and children are not separated from their parents based on conditions of economic hardship (SB 1085).

Increasing Focus on Behavioral Health. Beyond the child welfare system itself, significant legislative efforts have focused on California’s health care system—including behavioral health programs and services. Ongoing efforts include multiyear initiatives led by the Department of Health Care Services, such as California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal, proposed changes to the Mental Health Services Act, and the Children and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative. Although most behavioral health services are delivered outside of the child welfare system, this policy area is a notable area of legislative focus given that: (1) services for mental health and substance use disorder can be important forms of child maltreatment prevention, and (2) many parents/caregivers and children who become involved with the child welfare system require these services as components of their overall child welfare case plans.

Inherent Challenges of the Child Welfare System

Decisions made within the child welfare system must prioritize safety, which may in some cases mean children cannot remain with their parent(s)/caregiver(s), at least on a temporary basis. At the same time, the child welfare system aims to strengthen families and keep children with their parent(s)/caregiver(s) whenever possible. As such, these goals of keeping children safe and keeping children with their parent(s)/caregiver(s) sometimes may seem at odds with one another. Getting it wrong—either removing a child who could remain safely at home with the right supports, or leaving a child in a harmful or dangerous situation—can have dire consequences and result in trauma to children and families. In this section, we lay out some issues related to these key tensions inherent to the child welfare system.

Mitigating Trauma

Public Health Research on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) Links Maltreatment With Negative Health Outcomes. ACEs are associated with a range of negative physical and behavioral health outcomes long term, such as increased risk of heart disease, diabetes, stroke, substance abuse, and mental health challenges. These negative impacts become much more likely for individuals having four or more ACEs. Research specifies that children who experienced various forms of maltreatment and family instability faced 16 percent to 28 percent higher risk for premature death depending on the type of maltreatment/instability. Research also has shown ACEs and excessive or prolonged exposure to stressors—known as toxic stress response—can make individuals more prone to certain health issues and impact parental behaviors. Furthermore, some studies have focused on how the impacts of trauma may be passed down, potentially increasing risk for trauma and maltreatment—and the various associated negative impacts—across generations within certain families and communities.

Research Shows Youth Who Experience Maltreatment Are More Likely to Experience Other Negative Outcomes. Children who have experienced the traumas associated with child maltreatment—whether or not they are placed into foster care—are significantly more likely to experience negative longer‑term life outcomes. In particular, research has found that youth experiencing maltreatment are less likely to graduate high school, less likely to attend college or university and to graduate, more likely to experience homelessness, more likely to be incarcerated, and more likely to be referred to substance use disorder treatment. In addition, research has found these outcomes are worse for foster youth compared to other youth experiencing poverty who did not experience foster care.

Child Welfare System Intervention May Be Necessary for Child Safety, but Also May Result in Additional Trauma. Families who come to the attention of the child welfare system often are experiencing significant challenges, such as substance use disorder or domestic violence, which can cause trauma to the children and family. Given the shorter‑ and longer‑term negative impacts of experiencing trauma and maltreatment, child welfare system intervention may be necessary to help keep children safe within these potentially harmful situations. At the same time, involvement with the child welfare system may result in additional trauma, particularly when a child is removed from their parent(s)/caregiver(s). In spite of the trauma that may result from foster placement, removals nonetheless are necessary to protect children in some situations. For example, a child experiencing repeated physical abuse would experience continued harm if left in their situation. While intervention may introduce additional or different trauma, it may be less than if there were no intervention. How best to ensure child safety in a way that minimizes and mitigates trauma and ideally keeps the child with their parent(s)/caregiver(s) is a core tension inherent to the child welfare system.

California Increasingly Has Focused on Trauma‑Informed Care and Prevention. Many of California’s policies and recent budget augmentations in the child welfare system focus on preventing maltreatment and providing trauma‑informed care when maltreatment has occurred. In addition, California’s policies (along with federal policies) increasingly have focused more on prevention services. When removals are necessary, policies and funding also have focused on lessening the trauma of child welfare system involvement by aiming to increase foster placements with relatives (as opposed to unrelated resource families or congregate care).

Poverty and Risk Factors for Maltreatment

Poverty or Economic Hardship Is a Key Risk Factor for Child Maltreatment. Economic hardship creates conditions in which the risk of maltreatment is higher due to stress, lack of resources, and other factors. Throughout the history of the child welfare system, the vast majority of system‑involved families have been low or very low income. Research has found both individual family poverty as well as neighborhood/community poverty are risk factors for child maltreatment. A study from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that children living in poverty are at seven times higher risk for neglect, three times higher risk for physical abuse, and two times higher risk for sexual abuse.

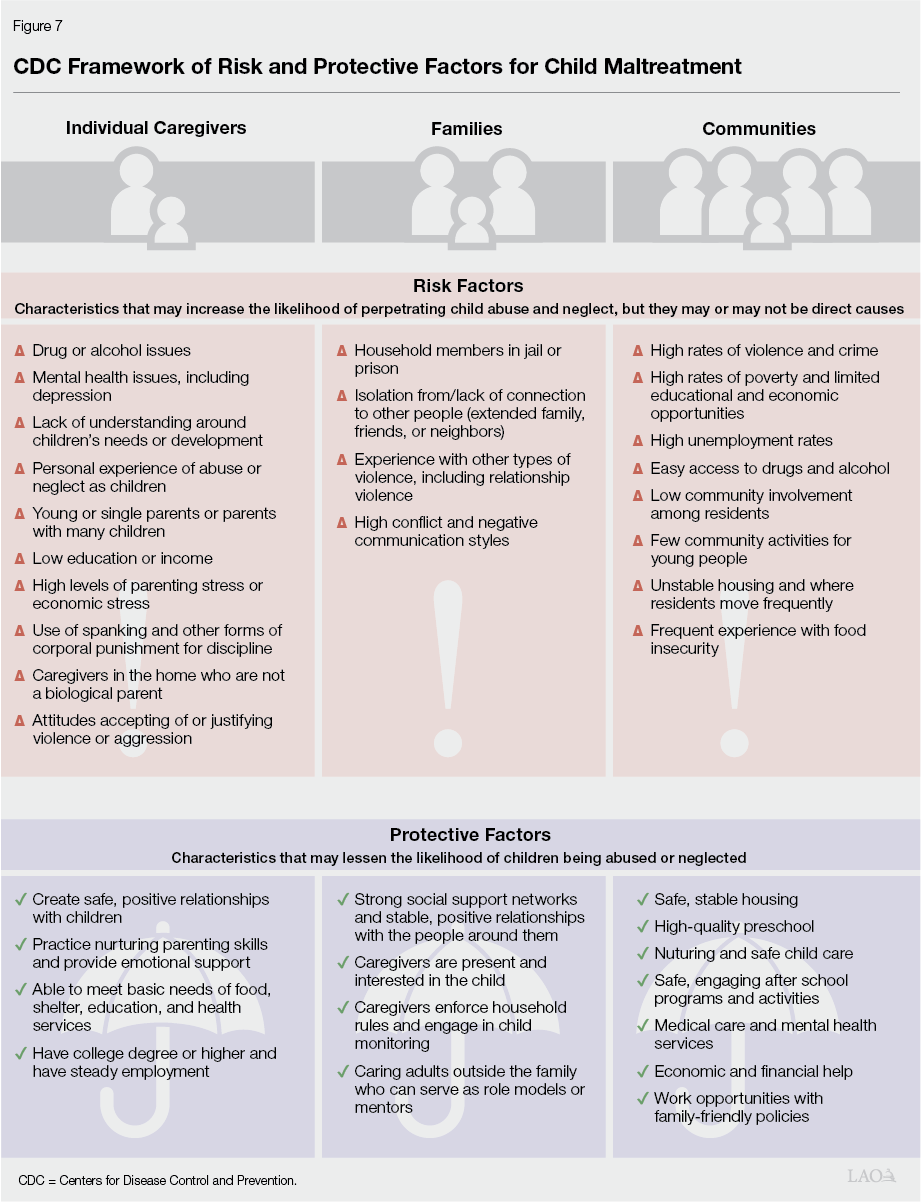

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Framework Lays Out How Poverty Correlates With Other Risk Factors. The national CDC developed a framework of risk and protective factors for child maltreatment, shown in Figure 7. Many of the risk factors derive from or otherwise strongly correlate with experiencing poverty or economic hardship. According to the CDC, “Risk factors are characteristics that may increase the likelihood of experiencing or perpetrating child abuse and neglect, but they may or may not be direct causes. A combination of individual, relational, community, and societal factors contribute to the risk of child abuse and neglect.” Importantly, the presence of risk factors does not necessarily mean that child maltreatment will occur, but rather indicates increased risk that maltreatment may occur. Different families may experience the same combination of risk factors but have different outcomes.

Differentiating Between Poverty and Possible Maltreatment Key Challenge. A key challenge of decisions made within the child welfare system is how best to support families with poverty‑related risk factors for maltreatment. Research finds that children experiencing poverty and other correlated factors are at greater risk for maltreatment, and maltreatment is linked with many negative life outcomes. As such, intervening in cases of maltreatment is imperative. At the same time, child welfare system involvement itself can cause trauma. How to differentiate between families in need of economic and other supports, as opposed to families who require child welfare system‑level intervention for substantial risk of harm due to maltreatment, is an inherent challenge for decision makers across the child welfare system.

Disproportionalities in Child Welfare

In this section, we describe the disproportionalities and disparities in California’s child welfare system as they relate to income, race, and ethnicity. Understanding which California communities and families are impacted at disproportionate rates—and the possible reasons why—can help the Legislature consider which policy interventions may be most effective at addressing these disproportionalities and disparities. The box below provides additional context around the language used in this report to describe disproportionalities and disparities in California’s child welfare system.

General Notes on Language Used in This Report

In this report, where disaggregated data are available, we use the racial and ethnic groupings currently employed by the U.S. Census and in state data sources, namely: white, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian and Alaska Native (or Native American), Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, Hispanic or Latino, and other. We note that some groups may prefer different terminology to refer to racial and ethnic groupings. However, this report uses these categorizations because they reflect available state and national data. Examining child welfare experiences based on these categories is important because peoples’ race and ethnicity—as well as other characteristics—can influence both their experience in society and with government policy.

We also refer to disproportionalities and disparities throughout this report. A disproportionality occurs when one group’s percentage in a target population differs from that group’s percentage in the base population. In the child welfare system, disproportionality occurs when, for example, one group’s representation in foster care is larger than (overrepresented) or smaller than (underrepresented) that group’s share of the general child population. Disparity, on the other hand, refers to groups experiencing inequities relative to one another. Disparity occurs when the ratio of one group experiencing an event is not equal to the ratio of another group experiencing the same event. In the child welfare system, for example, disparity is often used to describe inequitable outcomes experienced by different groups, such as the average amount of time that children of different racial/ethnic groups spend in foster care or the likelihood of reunifying successfully with their parent(s)/caregiver(s).

Lower‑Income Families Disproportionately Represented

Most of California’s Families Involved With the Child Welfare System Live in Poverty. We do not have aggregated data about family income level for those involved with the child welfare system, but available data reflect that the majority of children in foster care live in deep poverty. Specifically, an estimated 53 percent of youth in foster care in 2023‑24 are removed from families who meet 1996 federal Aid to Families with Dependent Children eligibility requirements. This roughly equates to earnings of under $1,000 per month for a family of four. Nationally, researchers estimate around 85 percent of families involved with the child welfare system have incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty level, which is around $5,000 per month for a family of four in 2023.

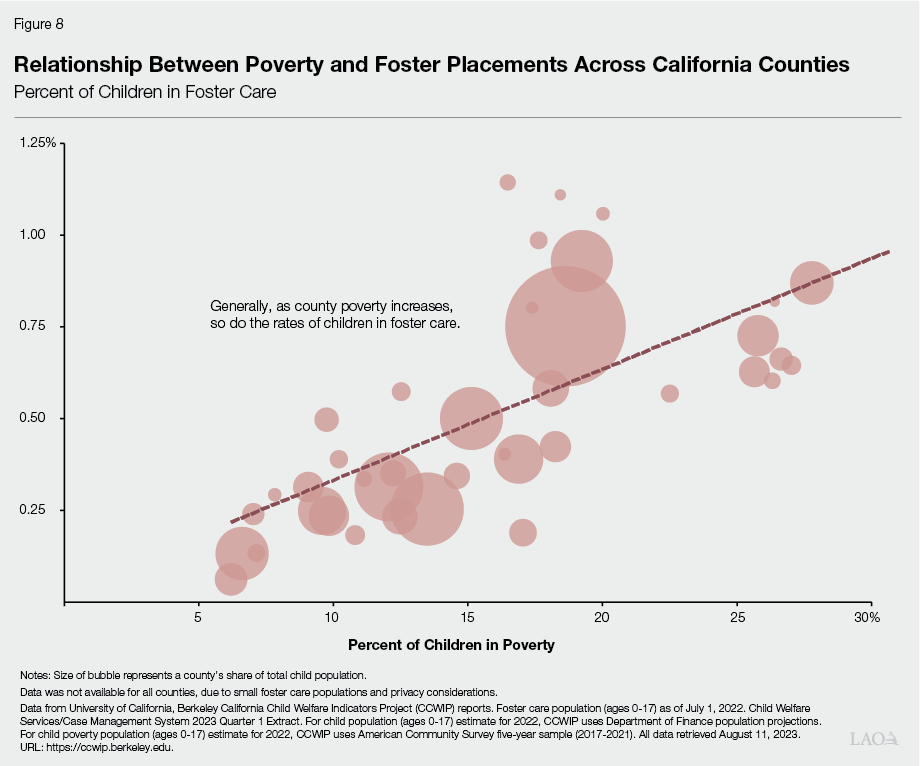

Rates of Child Welfare System Involvement Correlate With Rates of Poverty in California. Throughout all levels of the child welfare system, families experiencing poverty are more likely to come to the attention of and be impacted by the child welfare system. For example, across California, foster placements by county increase as the rate of poverty increases, as shown in Figure 8. As another example, recent research found that lower‑income California children—that is, those with public health insurance (Medi‑Cal)—experienced child welfare involvement at more than twice the rate of those with private insurance. These findings reflect the CDC framework, given that poverty and correlated factors are known risks that increase the likelihood of child maltreatment. Therefore, the fact that lower‑income families are more likely to become involved with the child welfare system is not surprising and to a large extent reflects differences in exposure to risks.

Black and Native American Children Significantly Overrepresented

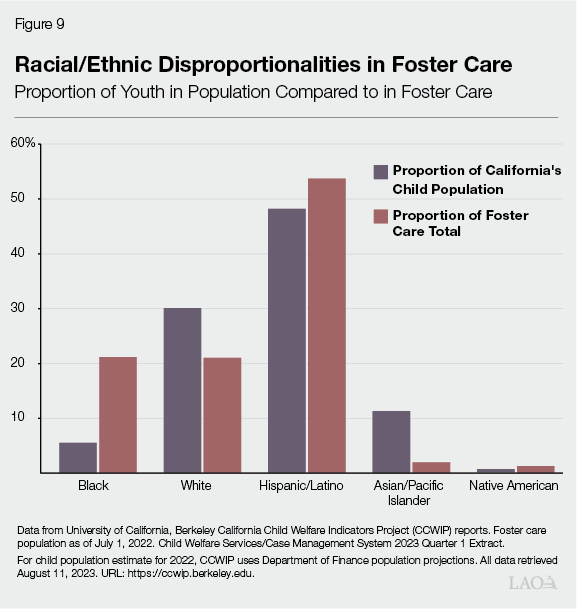

Black and Native American Children Disproportionately Experience Foster Care Placement. The proportions of Black and Native American youth in foster care are around four times larger than the proportions of Black and Native American youth in California overall. Figure 9 illustrates these disproportionalities. While the figure displays aggregated state‑level data, disproportionalities differ across counties. These disproportionalities have persisted over time.

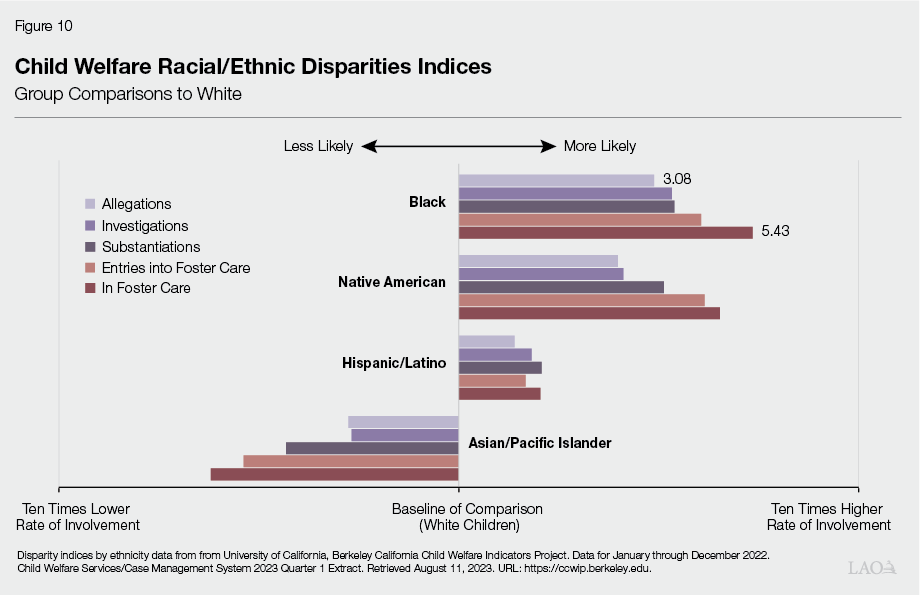

Disparities Are Present at All Stages of Child Welfare System Involvement, Becoming More Pronounced at Later Stages. In addition to disproportionate representation, disparities between racial and ethnic groups also are present across the child welfare system. As shown by Figure 10, disparities are present beginning with allegations and are maintained through all stages of child welfare system involvement, becoming most pronounced for children who are removed from their home and are in foster care. Figure 10 shows the relative extent to which children of different racial/ethnic groups are involved with various levels of the child welfare system, compared to white children. Bars to the right of center indicate relatively higher rates of involvement, while bars to the left of center indicate relatively lower rates of involvement. For example, a bar extending to the far right of the figure would indicate ten times higher likelihood of involvement. Similarly, a bar extending all the way to the far left of the figure would indicate ten times lower likelihood of involvement. Specifically, the top set of bars indicates that Black children are around three times more likely to be the subject of an allegation and nearly five‑and‑a‑half times more likely to be in foster care compared to white children.

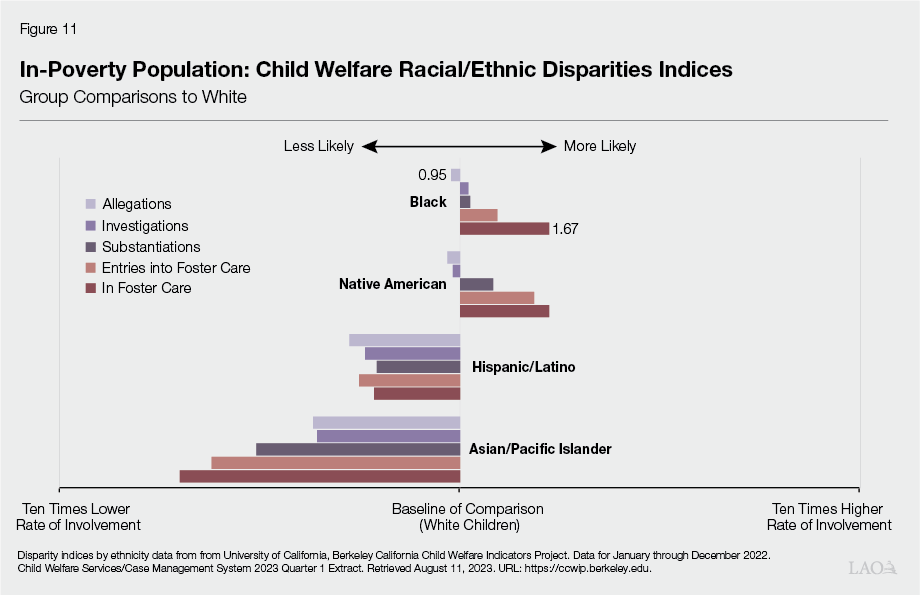

After Accounting for Poverty, Disparities Remain for Certain Groups. When adjusting for poverty, disparities are diminished as shown in Figure 11, although Black and Native American youth are still more likely than all other racial/ethnic groups to have substantiated allegations, enter into, and be in care. In addition, when controlling for poverty, the overall trend for Hispanic/Latino children changes and they are less likely, relative to white children, to become involved with the child welfare system. Notably, these data reflect the federal poverty level. Rates of deep poverty—that is, families with incomes lower than 50 percent of the federal poverty level—also vary by race/ethnicity. In California, Black, Native American, and Hispanic/Latino children are more likely than children of other races/ethnicities to experience this more extreme level of deprivation. For example, in 2021, Black children were roughly three times more likely than white children to experience deep poverty (16 percent compared to 5 percent).

Cumulative Lifetime System Involvement Also Disproportional and Disparate. Recent research on cumulative child welfare involvement of California’s 1999 birth cohort found nearly one‑in‑two Black and Native American children experienced some level of child welfare system involvement (meaning they were at least the subject of an investigated allegation) by the time they turned 18 (compared to around 29 percent of Hispanic/Latino children, 22 percent of white children, and 13 percent of Asian/Pacific Islander children). This means Black and Native American children are more than twice as likely as white children to have experienced some level of child welfare system involvement by the time they turn 18.

Racial Disparities Persist in Outcomes. In addition to disproportionate and disparate representation of certain groups’ involvement with all levels of the child welfare system, disparities in terms of child welfare outcomes also are well documented. For example, the same research referenced in the preceding paragraph also found that 3.2 percent of Black children in California and 3.8 percent of Native American children in California experienced termination of parental rights, compared to 1.3 percent of white children (and 0.8 percent and 0.3 percent for Hispanic and Asian children, respectively). This means California’s Native American children were more than three times more likely than white children, and more than 12 times more likely than Asian children, to have their legal relationship with their biological parents severed by the time they turned 18.

High‑Level Factors Contributing to Disproportionalities

The disproportionate and disparate involvement of some racial/ethnic groups in California’s child welfare system is concerning because race/ethnicity alone is not a determining factor of the need for child welfare system involvement. The causes of these disproportionalities and disparities are complex and nuanced, reflecting challenges and risk factors that certain groups are more likely to experience. In this section, we describe some broader, high‑level social and economic factors—beyond the child welfare system itself—that may contribute to why certain racial/ethnic groups are disproportionately represented in the child welfare system today.

While the factors described in this section reflect some issues impacting families, the child welfare system makes decisions on a case‑by‑case basis and every case is unique. Each family is dealing with its own set of circumstances, risks, challenges, and supports/lack thereof, and each county/individual social workers are making decisions based on their own experiences and training. This individualized decision‑making in many ways represents a strength of the system, while simultaneously adding complexity in terms of understanding the drivers of disproportionalities at the system level.

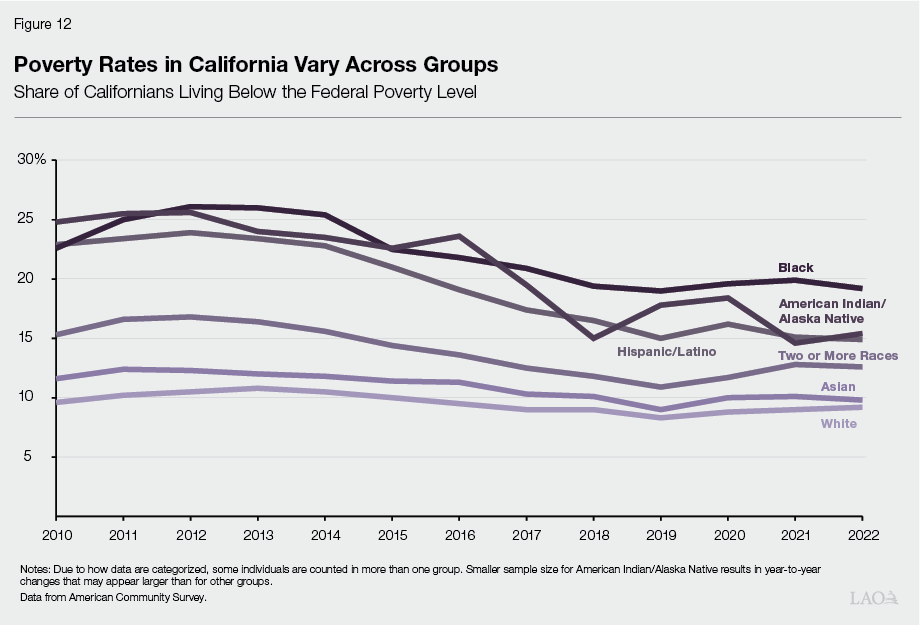

Disproportionate Exposure to Risk Factors

Some Groups More Likely to Be in Low‑Income Families and Experience Broader Risk Factors. Certain individual, family, and community characteristics increase the likelihood that child maltreatment may occur. For example, as shown in Figure 7, one factor associated with higher risk for maltreatment is economic stress. Black, Native American, and Hispanic/Latino communities in California are more likely to experience poverty, as shown in Figure 12, and deep poverty. Increased exposure to poverty is in part due to policies and practices that disproportionately impacted these communities over time. For example, discriminatory housing and lending practices significantly reduced Black families’ ability to accumulate wealth. Black Californians today are less likely than other racial/ethnic groups to own homes, with less than 40 percent of Black Californians living in homes that they own, relative to nearly 65 percent of white and Asian Californians. Absent the wealth accumulated through home ownership, families may be more likely to experience economic instability and stress.

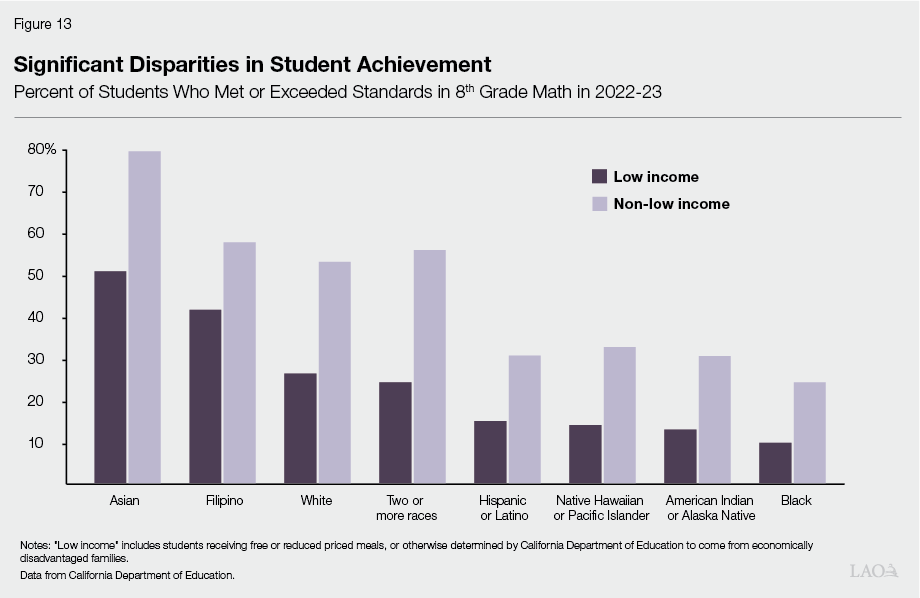

As shown in Figure 7, another factor associated with higher risk for maltreatment is low education. Research finds that income and racial segregation across schools is associated with lower levels of educational proficiency and attainment for Black, Native American, and Hispanic/Latino students. Notably, these racial/ethnic groups continue to experience less desirable educational outcomes when accounting for income. For example, as illustrated by Figure 13, across both higher‑income and lower‑income families in California, Black, Native American, and Hispanic/Latino students are significantly less likely than white and Asian students to meet or exceed 8th grade math proficiency levels.

Native American Children Were Systematically Removed From Families. Studies estimate that 25 percent to 35 percent of all tribal children were removed from their parents and communities under federal policies that existed through the 1970s. Specifically, these policies aimed to displace and assimilate tribal communities by placing children in white, English‑speaking settings. Due in part to these policies, Native American families disproportionately continue to experience risk factors for child maltreatment such as isolation from family and community. While the federal and state governments have taken steps to address these discriminatory policies, they continue to impact Native American communities in California. The box below describes these federal and state steps to protect and strengthen Native American children’s connections to their tribes.

Child Welfare Policy Toward Native American Tribes

Historical federal policies overtly sought to displace and assimilate tribal communities. The child welfare system was used as a policy tool to this end: through Indian boarding schools and later the Indian adoptions project, federal government policy was to remove children from their homes, tribes, languages, and culture and place them into white, English‑speaking settings. Specifically, studies have found that 25 percent to 35 percent of all tribal children were being removed from their parents and communities through these policies, and of those removed, 85 percent were placed outside of their families and communities—even in cases when relative or other tribal placements were available. Research has found these policies contributed to intergenerational trauma, disproportionate exposure to risk factors for child maltreatment within Native American communities, and persistent child welfare system overrepresentation.

In response to Congressional testimony detailing the impacts of these policies, the federal Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) was enacted in 1978 and seeks to preserve cultural connections for tribal children involved with the child welfare system.

Since 2006, the California Legislature has passed a series of state laws which incorporate (and expand upon) ICWA’s protections for tribal communities within the child welfare context. The Department of Social Services (DSS) continues to work toward fully updating child welfare guidance and regulations in line with these state laws as well as the federal ICWA. As a recent example, since May 2023, DSS has been issuing a series of letters to county welfare directors with guidance around implementing specific requirements for partnering and collaborating with tribes in child welfare cases subject to ICWA. In addition, other recent laws have sought to improve various other elements of California’s government‑to‑government relations with tribes, including, for example, Chapter 475 of 2022 (AB 923, Ramos), which encourages state agencies to cooperate with tribes on matters of economic development and other programs.

Disproportionate Exposure to Mandated Reporters

Low‑Income Groups More Likely to Come Into Contact With Social Workers. Some child welfare policy experts have raised the idea that certain groups are more likely to come into regular contact with professionals, such as social workers, who are required by law to report any suspected child maltreatment. For example, given Black, Native American, and Hispanic/Latino families are more likely to be low income, they may be more likely to come into contact with social workers serving these families through programs like CalWORKs. These interactions may contribute to the disproportionate involvement of these groups in child welfare by resulting in additional referrals.

Some Communities More Likely to Come Into Contact With Criminal Justice System. Families living in high‑crime neighborhoods and areas otherwise experiencing higher levels of criminal justice system involvement—which tend to be lower‑income Black, Native American, and Hispanic/Latino communities—are more likely to come into contact with police. Police officers commonly refer families to the child welfare system in situations of domestic violence, substance use, and other circumstances when children may be unsafe in their home. In addition, arrest and incarceration rates in California for Black and Native American men and women, as well as for Hispanic/Latino men, are significantly higher than for other racial/ethnic groups. When a parent/caregiver is incarcerated and no other caregiver is present, foster care placement may be necessary. Overall, Black, Hispanic/Latino, and Native American communities’ disproportionate exposure to and involvement with the criminal justice system may contribute to disproportionate child welfare system involvement by resulting in additional referrals and necessitating foster placement when a parent/caregiver is incarcerated.

Role of Implicit Bias

Implicit Bias May Impact Child Welfare Decisions. Psychological and sociological research has documented that all individuals have biases, including implicit/subconscious biases, which impact individuals’ decision‑making. Research has tried to identify the role these implicit biases may have on child welfare‑related decisions. For example, some studies find that despite similar assessment of risk and other family characteristics, caseworkers were more likely to substantiate allegations for and remove Black children compared to white children, and less likely to offer preventative services to Black families. In contrast, however, other research finds that accounting for family and case characteristics explains most racial disparities in substantiations and removals. Other research examining decisions made by medical professionals finds implicit bias may play a role. For example, research found that medical professionals examining similar injuries were significantly more likely to report suspected abuse for Black children compared to white children.

Front‑End Policies Impacting Child Welfare System Involvement

In this section, we lay out “front‑end” child welfare system policy areas potentially impacting disproportionalities and disparities. In some cases, the Legislature already took some actions to enact policies aiming to mitigate the overrepresentation of certain groups in foster care. We define front‑end policies as all policies prior to and including a social worker’s decision to remove a child and place them into foster care. Thus, this definition includes services and supports for families prior to allegations of maltreatment, as well as protocols and decisions around reporting, investigating, and substantiating allegations, and possible removal and foster care placement. We focus on these areas because addressing front‑end system issues could help mitigate the growing disparities at later stages of the system. As described in the background section of this report, some recent legislative bills and budget augmentations have focused on reducing disparities at later stages of the system, often by supporting placements with relatives. Continuing to implement reforms beyond the front‑end of the system will be important to help improve outcomes for youth once they are in foster care; however, this report focuses on disproportionalities and disparities prior to that point.

Mandated Reporting of Suspected Child Maltreatment

State Law Defines Certain Professionals as Mandated Reporters and Requires Them to Report Any Suspected Maltreatment to Child Welfare Agency. Federal law requires states to have provisions or procedures for reporting known or suspected child maltreatment. However, federal law does not specify who should be required to report or the standards for making a report, leaving this to states’ discretion. In California, the Child Abuse and Neglect Reporting Act (CANRA) (Penal Code Sections 11164‑11174.3) defines numerous professionals as “mandated reporters” and lays out the specific procedures for required reporting. The state’s mandated reporters include teachers and other school personnel, medical professionals, social workers, law enforcement, child care workers, and numerous other professionals who may be in regular contact with children and their families. CANRA specifies that mandated reporters must report to their local child welfare agency (or police/sherriff department) as soon as possible upon suspecting maltreatment. CANRA further specifies that mandated reporters may face consequences for failing to report, including up to six months jail time and a $1,000 fine.

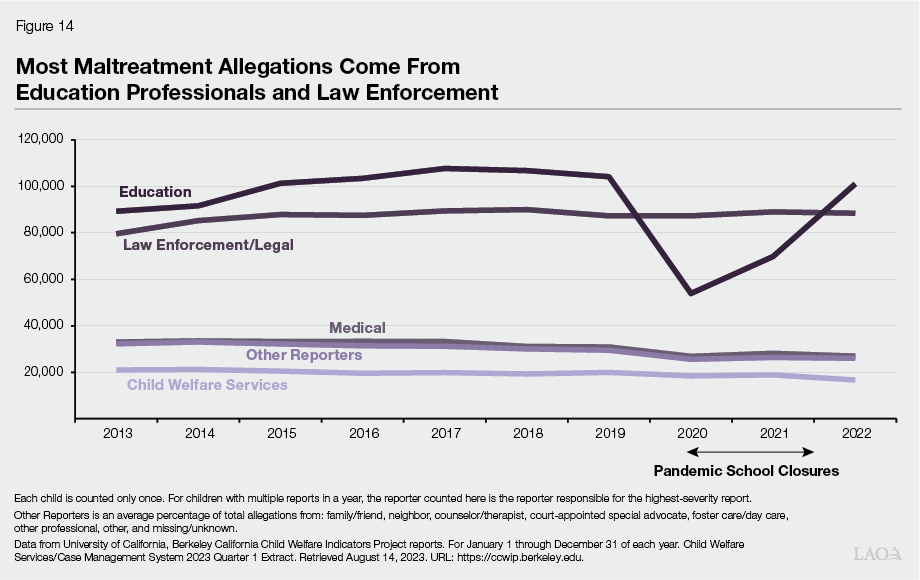

Large Number of Mandated Reports Each Year, Mostly Coming From Teachers. Annually, around half a million reports are made to the state’s child abuse hotlines. As shown in Figure 14, in most years, the largest percentage of these reports are made by teachers and other school personnel (around 20 percent) with the second largest percentage coming from law enforcement and other legal professionals (also around 20 percent in recent years). The COVID‑19 pandemic period saw the number of reports from teachers/school personnel drop sharply, likely in large part due to school closures which resulted in less in‑person contact between teachers and children.

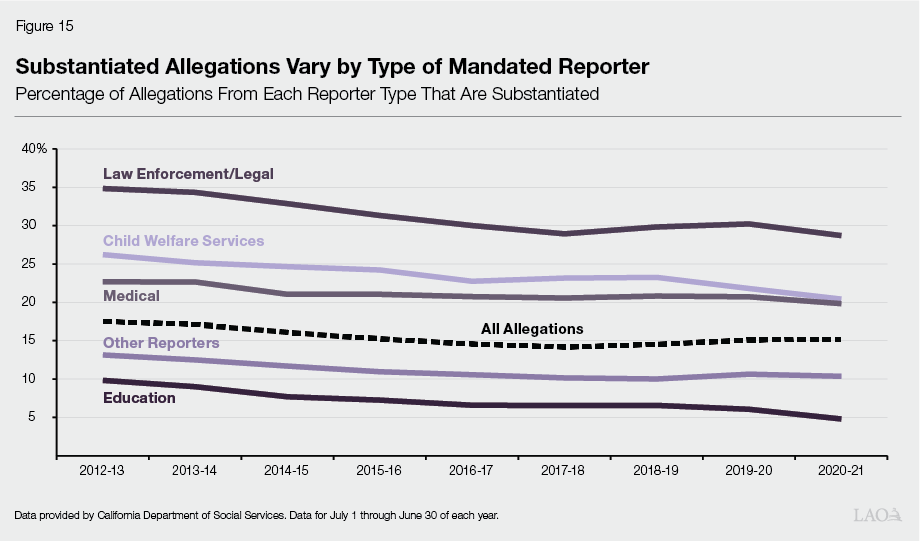

Substantiation Rates Vary Significantly by Reporter Type. Allegations from certain reporter types, relative to other reporter types, are much more likely to be substantiated and result in entries to care. In particular, as shown in Figure 15 , reports from law enforcement are the most likely to be substantiated (around 30 percent substantiation rate in recent years), while reports from teachers and other school personnel are around five to six times less likely to be substantiated (around 5 percent in recent years). Reports from child welfare and medical professionals also are substantiated at relatively high rates (around 20 percent in recent years). Part of this difference across reporter types likely is related to the circumstances under which the mandated reporter has contact with the child. For example, medical professionals may be more likely to report allegations of physical abuse based on observing certain types of fractures or patterns of bruising, which may be more straightforward for child welfare social workers to substantiate compared to some other types of allegations, such as general neglect.

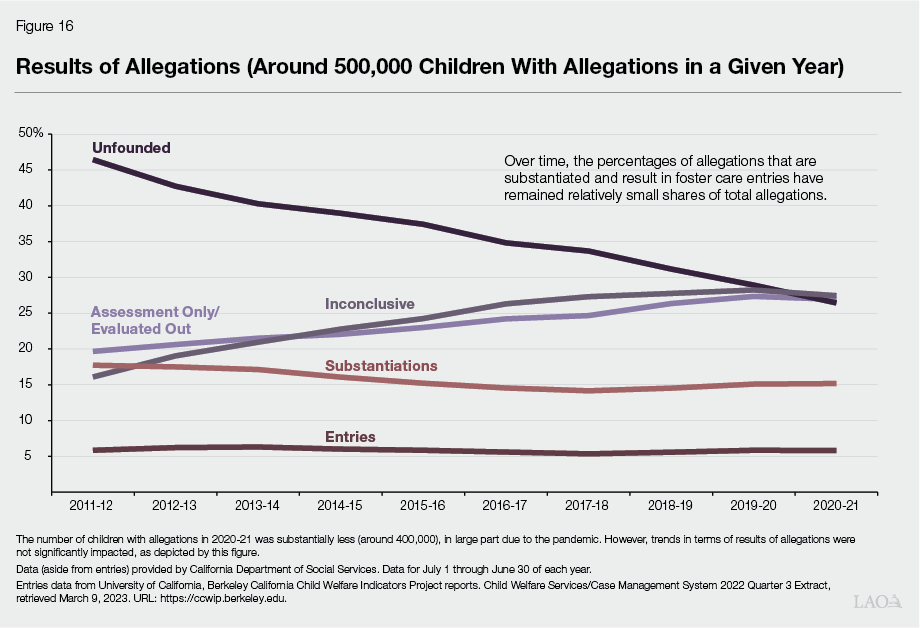

In Total, Small Percentage of Allegations Are Substantiated and Result in Foster Placement. Ultimately, a large share of families who are the subject of a maltreatment allegation are not found to have mistreated their children. As shown in Figure 16, while there are around half a million California children who are the subjects of allegations in any given year, only around 15 percent of allegations are substantiated, and around 6 percent result in foster care entry, with the remainder of allegations determined to be unfounded, evaluated out, or inconclusive. Some portion of allegations that do not result in foster placement are referred to family strengthening services (which could be court‑mandated FM, voluntary FM, or provided by community organizations as part of a county’s DR program—as described previously).

State Law Does Not Require Most Mandated Reporters to Receive Specific Training. CANRA requires employers of mandated reporters to inform their employees of their legal responsibilities to report suspected or known maltreatment. However, the law does not require most mandated reporters to complete any training related to these responsibilities (although the law does “strongly encourage” employers to provide such training). One notable exception is for teachers and other school employees: the Education Code (Section 44691) specifies that school employers shall annually train their employees regarding mandated reporting duties. While the required training must be in line with guidance provided by the California Department of Education and DSS’s Office of Child Abuse Prevention (OCAP), there is not a specific training curriculum that school employers must use. OCAP has developed standard training modules (including a general training as well as modules tailored for teachers, child care providers, social workers, and more), which are available online and meet all state requirements. However, most school employers (around 60 percent of school districts) use a training other than the state‑developed standard modules.

Additionally, for certain professions, training around recognizing child maltreatment and understanding mandated reporting responsibilities is a part of professional education and development. For example, social workers learn about reporting responsibilities and protocols as part of their foundational training (described above in Front–End Policies Impacting Child Welfare System Involvement). In addition, many medical and nursing school programs teach students about pediatric injuries commonly associated with child abuse, and California’s peace officer training academies introduce candidates to various state reporting requirements, including CANRA.

Administration Beginning Efforts Focused on Mandated Reporter Reforms. Improving mandated reporting practices is currently a focal point of the state’s Child Welfare Council (CWC). CWC is an advisory body statutorily responsible for improving collaboration across the multiple agencies and the courts that serve the children in the child welfare system. CWC is co‑chaired by the Secretary of the California Health and Human Services Agency and the designee of the Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court. In March 2023, CWC voted to form a “Mandated Reporting to Community Supporting Task Force,” which will provide a final report with implementation recommendations to CWC by June 30, 2024. The new task force began meeting in September 2023. In addition, in September 2023, DSS publicly announced plans to review and redesign the standard mandated reporter trainings. To inform the redesign, DSS will conduct focus groups with various stakeholders beginning in fall 2023 through spring 2024 “to ensure the online training provides the most upstream and supportive content to mandated reporters for having the necessary resources to adequately report only when necessary.”

Neglect: Definition and Data

Statutory Definition of General Neglect May Be Broadly Interpreted and Confused With Conditions of Poverty and Other Factors. California law defines neglect as one form of child maltreatment. Although the law specifies that a parent’s economic disadvantage does not itself constitute general neglect, the definition nonetheless may be broadly interpreted. For example, OCAP’s standard mandated reporter training module describes some examples of neglect to include failing to provide enough healthy food and drink, failing to provide clothes that are appropriate to the weather, failing to ensure adequate personal hygiene, and exposing a child to unsafe/unsanitary environments. Within these parameters, individuals working with children may have difficulty distinguishing between a family’s need for support (due to poverty and other risk factors) or need for child welfare system involvement.

Guidance and Protocol Changes Resulting From Recent Legislative Actions Beginning Implementation. Given the complex relationship between poverty and interpretations of neglect, the Legislature in 2022 enacted AB 2085 and SB 1085, which aim to distinguish reportable neglect from a family’s challenges related to experiencing poverty (as described in the box above titled "Recent Bills Aim to Distinguish Poverty From Reportable Neglect"). Ultimately, outcomes of these statutory amendments will depend on changes in practice. To this end, in December 2023, DSS issued updated guidance to county welfare directors in accordance with these new laws. Specifically, All‑County Letter 23‑105 encourages local child welfare agencies to: refer families with economic needs to available services; develop clear policies and procedures for determining what constitutes “economic disadvantage,” and when a child may be at substantial risk of suffering serious physical harm or illness; and otherwise review their existing policies and procedures to align with these legislative provisions.

State‑Level Aggregated Data Around Underlying Causes of Neglect Are Limited. As shown by Figure 1, the majority of families who become involved with the child welfare system are referred to the system due to allegations of neglect. However, the state’s current child welfare data system does not provide quantifiable data about the harm or risk to the child underlying neglect cases. Instead, understanding the basis of investigated and substantiated neglect allegations requires reviewing counties’ narrative reports for individual cases. As shown by Figure 2, one recent study reviewed a sample of qualitative information from investigations and offers insight into common types of investigated neglect and parental risk factors; however, systematic data are not available.

Decision‑Making Tools and Training for Social Workers

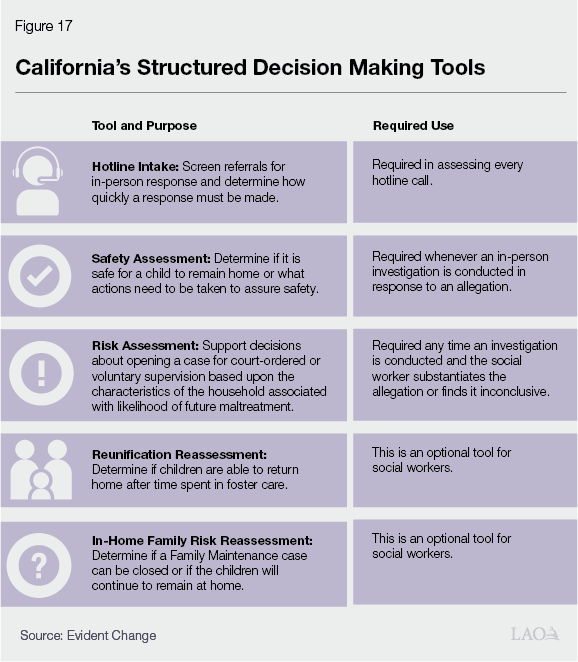

Structured Decision Making® (SDM) Tools Employed by Social Workers Help Guide Various Decisions. As noted below, California’s child welfare social workers use standardized decision‑making tools, which are designed to help them navigate decision points and employ more uniform standards across cases. The specific tools used in California are called SDM tools. (These are proprietary tools developed and maintained by a third‑party contractor.) Since 2016, all of California’s 58 counties have been using a suite of SDM tools, including a number of specific point‑in‑time decision‑making assessments, each aiming to guide social workers in determining the best next steps for the youth and family in question. California’s SDM assessment tools currently include the specific tools outlined in Figure 17.

Each tool includes a series of questions and decision trees that guide social workers to recommended actions and next steps based on calculated risk scores. However, social workers make the ultimate decision about next steps. For example, if a social worker believes that the risk score does not accurately portray the household’s actual risk level, the social worker may increase or decrease the risk level and provide an explanation for the decision. Most of California’s SDM tools were developed through a process involving the proprietor, state, and local stakeholders, informed by statute, policy, and child welfare practice in the state. However, the risk assessment tool was developed by the proprietor using data pertaining to the characteristics of families who have had ongoing involvement with the child welfare system after an initial investigation.

DSS and Proprietor Review and Update SDM Tools. DSS and the proprietor have access to SDM tools data, and also review and update the suite of tools as deemed necessary. Notably, in December 2023, DSS and the proprietor made a number of changes to some of the tools to align with the recent departmental guidance around AB 2085 and SB 1085 (described above in Neglect: Definition and Data), as well as with recent guidance related to communication and collaboration with tribes in cases potentially subject to the federal Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) (described in the box above titled Child Welfare Policy Toward Native American Tribes). DSS communicated these changes to counties via All‑County Letter 23‑101.

State Beginning to Use Blind Decision‑Making Tools in Some Policy Areas. Another approach to attempting to mitigate individual implicit biases in child removal decisions is known as “blind removal,” which some counties (and other states) have begun to pilot. (Examples of blind removal initiatives, and other types of “blind” decision‑making, are described more in the box below.) In the child welfare context, blind removal refers to the practice of having a social worker (different from the social worker who conducted the initial investigation) review allegation reports and removal decisions without having access to racially/ethnically identifiable information about the family/child. The aim of this practice is to ensure that a decision maker focuses only on the specifics of an allegation and risk factors, without exposure to race/ethnicity information, which could result in subconscious bias.

“Blind” Review and Decision‑Making

Blind removal practices were first implemented as a pilot program in 2009 in Nassau County, New York, where at the time, Black children were nearly 15 times more likely to be placed into foster care compared to their white peers. An assessment of program outcomes found that the rate of Black children removed (per 1,000 Black children in the general population) declined from 5.5 in 2009 to less than 2.0 in 2019. We note that there may have been other policy, practice, and external changes that occurred during this same period. As such, the decline may not have been solely the result of the blind removal pilot. New York’s governor in 2020 directed the state administration to begin implementing blind removal practices statewide.

In 2021, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted to implement a similar blind removal pilot program. The pilot, which concluded in fall 2023, was implemented at two regional county child welfare offices. To evaluate the pilot, the county partnered with the University of California, Los Angeles’ Pritzker Center for Strengthening Children and Families. The evaluation, published in March 2024, found some limitations of the pilot including data limitations and that other simultaneous initiatives with similar goals made identifying the specific impacts of the pilot challenging. That said, the evaluation noted some promising qualitative outcomes, such as changes to case worker practices based on an increased awareness of the role that race may play in decision‑making. Furthermore, the evaluation highlighted some lessons learned that could be applied to future blind removal efforts in other counties, such as the importance of dedicated staffing resources and consistent data management.

Beyond the child welfare system, other types of blind review and decision‑making also have been piloted in the criminal justice system. For example, in 2022, the Legislature unanimously approved Chapter 806 of 2022 (AB 2778, McCarty), which requires the Department of Justice to develop “Race‑Blind Charging” guidelines beginning January 1, 2024, with implementation by local law enforcement agencies slated to begin January 1, 2025. According to the legislation, race‑blind charging refers to processes whereby prosecuting agencies review cases for charging based on information from which all means of identifying the race of the suspect, victim, or witness have been removed or redacted. This legislation follows race‑blind charging pilot programs in certain jurisdictions, including San Francisco and Yolo Counties.

Training Around Recognizing and Mitigating Biases. While a specific implicit bias training is not required by state statute or regulations, recognizing and mitigating bias is intertwined throughout the mandated statewide curriculum that all new child welfare social workers complete to ensure they have the foundational training necessary for competence in the field. DSS contracts with the California Social Work Education Center and the statewide Regional Training Academies to provide this initial training and continuing education to child welfare social workers. Various optional trainings—such as those provided by different DSS‑contracted vendors—are also available and may address topics related to implicit bias and uniform decision‑making. Previous budgets also have provided funding for implicit bias training for certain program staff, such as for CalWORKs social workers.

Prevention

Availability of Prevention Services Within the Child Welfare System Is Limited. As noted earlier, some recent legislative actions and budget augmentations focus on preventing child maltreatment and the associated trauma. While FFPSA presents a significant potential expansion of Title IV‑E dollars, certain key limitations exist. In particular, FFPSA allows Title IV‑E funds to be used only for prevention services provided to eligible “candidates”—children and families assessed by child welfare agencies as at risk of child maltreatment and who meet specific eligibility criteria—not for broader implementation of programs that could help reduce the risks of child maltreatment for whole communities. In addition, currently there are limited culturally relevant federally approved services that are specifically designed to serve the families/communities who are most overrepresented in California’s child welfare system. State block grant dollars included in the 2021‑22 budget to help counties begin implementing their CPPs may be used more broadly, although these are one‑time funds.

Access to Prevention Services Within the Child Welfare System Is Uneven. In addition, the state gave counties flexibility over whether and how to implement prevention services. This means access for California’s youth, families, and communities to Title IV‑E prevention services and other supports will vary depending on geography and participating counties’ CPPs. For example, for the 50 counties and 2 tribes that have opted into prevention services under FFPSA, the Title IV‑E eligible prevention services that child welfare agencies most commonly selected to implement include:

- Motivational Interviewing (25 agencies), a method of counseling designed to promote behavior change and improve physiological, psychological, and lifestyle outcomes.

- Parents as Teachers (21 agencies), a home‑visiting parent education program that teaches new and expectant parents skills intended to promote positive child development and prevent child maltreatment.

- Healthy Families America (16 agencies), a home‑visiting program for new and expectant families with children who are at‑risk for maltreatment or adverse childhood experiences.