LAO Contact

May 7, 2024

Update on Student Housing Assistance

Summary

State Recently Created Student Housing Assistance Programs. In 2019‑20, the state created rapid rehousing programs at the University of California (UC), California State University (CSU), and California Community Colleges (CCC) to assist students experiencing housing insecurity or homelessness. In addition, the state created basic needs programs at UC in 2019‑20 and at CSU and CCC in 2021‑22 primarily to provide students with housing and food assistance. In 2023‑24, the state is providing a total of $31 million ongoing General Fund for rapid rehousing programs and $85 million ongoing General Fund for basic needs programs across the segments. State law requires each segment to report annually on these programs, with specific reporting requirements varying by segment and program. In this brief, we examine how each segment is implementing these programs and review the available outcomes data.

UC Implementation Update. UC is allocating both rapid rehousing and basic needs funds to all ten of its campuses. Campuses are using these funds to provide various types of housing assistance, including emergency grants, emergency housing, and case management. Given UC (like the other segments) is receiving state funding to provide these types of services for the first time, a notable share of program costs is for staffing and building the capacity to implement the programs. Relative to the other segments, UC is more likely to provide housing assistance using on‑campus resources, including its own staff and residence halls. In 2022‑23, UC reports 6,604 students received housing assistance through its basic needs program and 4,706 students received housing assistance through its rapid rehousing program, with likely duplication among the two counts.

CSU Implementation Update. In contrast to UC, CSU awarded rapid rehousing funds competitively to 8 of its 23 campuses. These campuses are hiring program staff as well as working with community partners to provide housing identification, rental subsidies, and case management to a small number of high‑need students. Across the first two years of the program, CSU reports 342 students enrolled in its rapid rehousing program. CSU is allocating basic needs funds to all 23 of its campuses to provide various types of housing assistance (including temporary emergency housing and emergency grants) to a broader group of students. In 2022‑23, CSU reports about 14,000 students received housing assistance through this program.

CCC Implementation Update. Like CSU, CCC awarded rapid rehousing funds competitively, with 25 of the 115 local community colleges currently participating in the program. In 2021‑22, CCC reports 519 students received rapid rehousing assistance across the 14 participating colleges. CCC is allocating basic needs funds to all 115 local colleges, with the majority of these funds going toward staffing and operating colleges’ basic needs centers. CCC reports students accessed housing assistance through these basic needs centers 4,156 times during summer and fall 2022 across the 60 colleges participating in the first round of reporting.

Recommend Refining Program Reporting Requirements. Although the segments are generally reporting helpful information on campus funding allocations, use of funds, and program participation, key information is lacking—particularly on outcomes. We recommend refining statutory reporting requirements for the these programs in several ways, including requiring each segment to report on a consistent and clearly defined set of measures related to participants’ housing outcomes and academic outcomes. For example, the Legislature could require each segment to report how many participating students maintain stable housing through the academic term and graduate or remain enrolled the following year. These types of data would allow the Legislature to better understand the cost‑effectiveness of these programs.

Introduction

Brief Focuses on Rapid Rehousing and Student Basic Needs Programs. In this brief, we cover the student housing assistance provided through the rapid rehousing and basic needs programs at UC, CSU, and CCC. The state began funding these programs within the past five years. This brief reviews the available information about how these recently created programs are working and the extent to which they are meeting program objectives. We begin by providing background on student housing insecurity, the rapid rehousing program, and the basic needs program. Then, we provide an implementation update on the housing assistance provided through both programs at UC, CSU, and CCC. We end by recommending certain changes to statutory reporting requirements that could help the Legislature monitor and improve the programs moving forward.

Background

In this section, we first discuss the available data on student housing insecurity and homelessness. We then describe the higher education programs that can help students with housing.

Student Housing Insecurity

Students Facing Various Types of Challenges Are Considered Housing Insecure. “Housing insecurity” can refer to a range of challenges related to an individual’s living arrangements. At California’s higher education segments, students are commonly described as housing insecure if they face challenges such as difficulty paying rent or utilities, living in overcrowded units, or needing to move frequently. The higher education segments tend to use “homelessness” to refer more specifically to lacking a stable place to stay at night. The segments’ definitions of homelessness typically include students without a permanent home who are temporarily staying with relatives or friends (“couch surfing”), at hotels or motels, in emergency shelters or transitional housing, and in places not meant for habitation (such as cars or tents).

Some of Students’ Housing Challenges Overlap With Those of Other Californians. Housing affordability is a widespread challenge in California, where the average monthly rent is about 50 percent higher than in the rest of the nation and about 2.5 million low‑income households spend more than 30 percent of their incomes on housing. While many factors have a role in driving California’s high housing costs, the most important is the significant shortage of housing, particularly within urban coastal communities. Like other Californians, college students face housing challenges stemming from this shortage of housing and the associated high housing costs. Like other people age 18 to 24, traditional college‑age students also could be moving away from their families for the first time, which could make them more vulnerable to housing insecurity.

Other Housing Challenges Are Unique to Students. Despite these commonalities, college students differ from their nonstudent peers in that they might relocate to attend college, and they might live in different places during the academic year and summer. These factors can complicate the search for stable housing. College students of all ages also are likely to have distinct financial circumstances. Because they are taking classes, they typically do not work as many hours and have lower earnings. They may also have additional costs associated with tuition, books, and supplies. Though facing higher costs, many college students qualify for financial aid to help with tuition and nontuition costs—another factor distinguishing them from their nonstudent peers.

Data on Student Housing Insecurity Has Limitations. Despite a high degree of legislative interest in student housing insecurity, the state does not have a definitive count of the number of higher education students experiencing housing insecurity or a reliable measure of changes over time. To derive estimates, UC, CSU, CCC, and the California Student Aid Commission have all begun conducting surveys. The data from these surveys, however, have limitations. Most of the surveys had low response rates, such that the respondents might not be representative of the broader student population. Moreover, some surveys limited their sample to specific student groups (such as financial aid applicants) that might have a different likelihood of experiencing housing challenges. Additionally, all of the surveys were administered electronically, which might have resulted in certain students (such as those with less technology access) being less likely to respond. Furthermore, few of the surveys have been undertaken regularly, with results tracked over time to determine whether student housing insecurity is increasing or decreasing.

Survey Data Suggest Notable Share of Students Face Housing Insecurity. Recognizing these data limitations, a notable share of students surveyed at each segment have reported experiencing housing insecurity and homelessness. Figure 1 summarizes reported rates from the most recent survey administered by each agency. Rates of students reporting homelessness at some point over the past 12 months ranged from 8 percent of respondents at UC to 24 percent of respondents at CCC. (These results may not be directly comparable across the segments due to differences across surveys in methodology, questions, and when they were conducted.) Rates of reported housing insecurity or homelessness varied among certain student groups. For example, surveys at all three segments found that Black students and students receiving Pell Grants (federal financial aid for low‑income students) reported higher‑than‑average rates of homelessness. In addition, the CCC and UC surveys disaggregated the data by sexual orientation and found that students who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ) reported higher‑than‑average rates of homelessness. The CCC survey also disaggregated the data by age group and found that reported rates of homelessness were highest among students age 26 to 30.

Figure 1

Data on Student Housing Insecurity Come From Various Surveys

Summary of Most Recent Survey From Each Agency

|

Agency |

Survey Date |

Survey Sample |

Response Ratea |

Reported Housing Insecurity and |

|

CSAC |

May 2023 |

Financial aid applicants from all segments |

5 percent |

|

|

CCC |

March ‑ April 2023 |

CCC students from 88 colleges |

Not specifiedc |

|

|

CSU |

October 2016 ‑ February 2017 |

CSU students from all campuses |

6 percent |

|

|

UC |

April ‑ August 2022 |

UC undergraduates from all campuses |

24 percent |

|

|

aIncludes completed responses only. Respondents may not be representative of broader student population. bSurveys measured whether respondents experienced housing insecurity and/or homelessness at some point over the past 12 months. Surveys generally defined housing insecurity to cover a range of challenges, including difficulty paying rent or utilities, overcrowding, and needing to move frequently. Surveys generally defined homelessness to include students who are couch surfing or staying at hotels or motels, in emergency shelters or transitional housing, and in places not meant for habitation (such as cars or tents). cAlthough the survey does not specify a response rate, we estimate the respondents reflect 6 percent of total headcount at participating colleges. dA high share of students reporting homelessness also could have reported housing insecurity. eSurveys do not provide estimates of overall housing insecurity rates. |

||||

|

CSAC = California Student Aid Commission. |

||||

Segments’ Surveys Are Not Comparable to Statewide Estimates of Homelessness. The most commonly cited measure of homelessness in California comes from a point‑in‑time count required every other year by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Based on the most recent point‑in‑time count, 181,399 people in California (0.5 percent of the total population) experienced homelessness on a single night in January 2023. This measure likely undercounts the state’s homeless population because of various factors, including difficulty reaching all homeless individuals. Notably, the point‑in‑time count is not comparable to the reported homelessness rates in the higher education segments’ surveys. Whereas the point‑in‑time count measures people experiencing homelessness on a single night, the segments’ surveys measure people experiencing homelessness at any point in the past 12 months. The latter figure is higher because many people experience temporary episodes of homelessness. Moreover, the point‑in‑time count generally does not capture people who are couch surfing or staying in hotels or motels. Couch surfing was by far the most common form of homelessness reported in the CCC and UC surveys, and staying in hotels or motels was the second most common. (The CSU survey did not report on specific forms of homelessness.)

Student Housing Programs

State Involvement in Student Housing Issues Has Grown in Recent Years. For many decades, the state’s primary strategy for promoting college affordability was to keep student tuition charges low, while providing grants that covered tuition charges for low‑income students. Over the last decade, however, students have been calling greater attention to their nontuition costs, including their housing costs. The growing amount of information and advocacy around student housing insecurity (including the surveys described above) has prompted the state to create new higher education programs. Some of these programs focus directly on student housing insecurity and homelessness. As the segments are implementing these types of programs for the first time, much of their initial efforts have centered around hiring the staff and building the capacity to implement them. Beyond California, some other states also have been exploring ways to address student housing insecurity. Most of these efforts are relatively recent too, with little information compiled nationally about their program designs and effectiveness.

State Recently Created Student Rapid Rehousing Programs. In 2019‑20, the state created rapid rehousing programs at UC, CSU, and CCC to help address student housing insecurity and homelessness. Traditionally, the term “rapid rehousing” refers to a specific model for moving people who are homeless into permanent housing. This model entails (1) finding them housing; (2) providing move‑in assistance and rental subsidies, typically for six months or less; and (3) offering case management to help them maintain stable housing and connect them with other relevant support (such as financial literacy, employment, and health care assistance). The rapid rehousing programs at the higher education segments, however, are somewhat broader. State law authorizes the segments to use program funds for various types of housing assistance, not limited to the components of the traditional rapid rehousing model. For example, the segments may also use the funds for temporary emergency housing and emergency grants to prevent students from losing their current housing. The target population for student rapid rehousing is also broader than for the traditional rapid rehousing model, with the segments allowed to use program funds to support students who are housing insecure but not homeless.

State Has Been Increasing Funding for Student Rapid Rehousing Programs. As the top part of Figure 2 shows, the state has increased funding for these programs over the past few years. In 2023‑24, the state is providing a total of $31 million ongoing. State law requires the segments to report annually on various aspects of their rapid rehousing programs, including campus funding allocations, the number of students served, and relevant outcomes. State law does not require the segments to report more specific fiscal data, such as the average amount spent to find a student stable housing or the average monthly housing subsidy provided to participating students.

Figure 2

State Has Increased Funding for

Rapid Rehousing and Student Basic Needs

Ongoing General Fund (In Millions)

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

|

|

Rapid Rehousing |

|||||

|

CCCa |

$9.0 |

$9.0 |

$9.0 |

$19.0 |

$20.6 |

|

CSU |

6.5 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

6.5 |

6.8 |

|

UC |

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

3.7 |

|

Totals |

$19.0 |

$19.0 |

$19.0 |

$29.0 |

$31.1 |

|

Student Basic Needs |

|||||

|

CCCa |

— |

— |

$30.0b |

$40.0 |

$43.3 |

|

CSU |

—c |

— |

15.0 |

25.0 |

26.3 |

|

UC |

$15.0 |

$15.0 |

15.0 |

15.0 |

15.8 |

|

Totals |

$15.0 |

$15.0 |

$60.0 |

$80.0 |

$85.4 |

|

aProposition 98 General Fund. bState also provided $100 million one‑time Proposition 98 General Fund. cState provided $15 million one‑time non‑Proposition 98 General Fund. |

|||||

State Also Recently Created Student Basic Needs Programs. In addition to the rapid rehousing programs, the state created an ongoing student basic needs program at UC in 2019‑20 and at CSU and CCC in 2021‑22. The statutory language for the basic needs programs varies by segment. In general, these programs are to support the establishment of a basic needs center on campus where students can access relevant resources; the hiring of campus basic needs coordinators to help students navigate those resources; and direct assistance to students, primarily with covering food and housing costs. State law does not specify the types of housing assistance the segments are to provide through the basic needs program, meaning the segments could use the funds for similar or different types of housing assistance than they are providing through the rapid rehousing program. As the bottom part of Figure 2 shows, the state also has increased funding for basic needs over the past few years. In 2023‑24, the state is providing a total of $85 million ongoing. State law requires each segment to report annually on its basic needs program. The reporting requirements are somewhat different for UC and CSU compared to CCC, but all segments are required to report on the use of program funds. (The box nearby describes other programs that help students with housing while in college.)

Other Programs Also Help Students With Housing

State Recently Began Funding Construction of Student Housing Facilities. Beyond the rapid rehousing and basic needs programs covered in this brief, the state also recently began supporting the construction of student housing at all three segments. Such support marks a significant departure from historical practice. Historically, the higher education segments’ student housing facilities have been self‑supported, generating their own fee revenue to cover their capital and operating costs. Under the new Higher Education Student Housing program, the state has approved 35 new student housing construction projects (consisting of 15 CCC projects, 11 CSU projects, 5 UC projects, and 4 intersegmental projects). By subsidizing project costs, the program intends to increase the supply of student housing while also lowering housing charges for some students. Across the segments, the state share of project costs totals $2.2 billion. Most of the projects are to be debt financed (using university bonds or state lease revenue bonds), with the state paying the associated debt service. The 2023‑24 Budget Act provides $164 million ongoing General Fund for those debt service costs.

Several Financial Aid Programs Help Students With Nontuition Costs. Though the state recently has created several new programs to address student housing insecurity, the state also has longer‑standing programs intended to help students cover their costs while in college. The state’s longest‑standing and largest financial aid program—the Cal Grant program—is serving an estimated 404,000 students in 2023‑24, of whom 279,000 are receiving nontuition awards generally worth up to $1,648 annually. In addition, the state’s recently expanded Middle Class Scholarship program is providing awards that average about $2,800 annually to an estimated 308,000 students combined at UC and CSU, with many students using their awards for nontuition costs. The state is also providing nontuition awards of up to $8,000 annually to more than 80,000 full‑time CCC students through the Student Success Completion Grant program. In addition to these state programs, many students receive nontuition assistance through federal programs, including Pell Grants and student loans. Some students, particularly at UC, also receive nontuition assistance through institutional grants. Due to the limited availability of basic needs funding, some campuses encourage or require students to maximize aid from these financial aid programs prior to receiving emergency grants through basic needs programs.

Implementation Updates

In this section, we provide an implementation update on the student housing assistance provided through the rapid rehousing and basic needs programs at UC, CSU, and CCC. For each segment, we review the available information on campus funding allocations, use of funds, program participation, and student outcomes.

UC

Background on UC System. The UC system has ten campuses, consisting of nine general campuses offering a broad array of academic programs for undergraduate and graduate students, plus one health sciences campus located in San Francisco that enrolls primarily graduate students. Across the ten campuses, UC currently enrolls a total headcount of approximately 296,000 students. The San Francisco campus is the smallest (enrolling approximately 3,000 students), whereas the Los Angeles campus is the largest (enrolling approximately 47,000 students). Among the three public higher education segments, UC has the largest share of students living on campus, with its residence halls housing nearly 40 percent of all undergraduates.

UC Is Allocating Rapid Rehousing and Basic Needs Funds to Every Campus. UC uses a similar allocation formula for both programs. First, it provides each of its ten campuses with a base amount of funding ($150,000 for rapid rehousing and $500,000 for basic needs). Then, it allocates the remainder of the funds largely based on the estimated number of students experiencing food or housing insecurity at each campus according to UC’s surveys. In 2022‑23 (the most recent year reported), rapid rehousing allocations ranged from $168,000 at the San Francisco campus to $472,000 at the Berkeley campus. Basic needs allocations ranged from $563,000 at the San Francisco campus to $1.8 million at the Davis campus. UC also retained $700,000 from the basic needs funds for systemwide activities, including technical assistance, coordination, and research and assessment.

Campuses Developed Coordinated Spending Plans Across Two Programs. In 2019‑20, UC directed each campus to develop spending plans simultaneously for both the rapid rehousing and basic needs funds. Campuses chose to use funds from both programs to provide various types of housing assistance. (Campuses are also using the basic needs funds to provide other types of assistance, most notably food assistance.) Common types of housing assistance that campuses are providing include financial assistance with rent and deposits, emergency housing, case management, and tenant education workshops (covering topics such as searching for housing and understanding leases). Housing assistance is often provided on a short‑term basis, such as through one‑time emergency grants or temporary emergency housing. Some campuses also offer long‑term housing assistance, such as ongoing rental subsidies. Variation among campuses in the types of housing assistance provided likely reflects differences in their local housing market, on‑campus housing inventory, and availability of community partners, among other factors.

Program Funding Primarily Supports Staffing and Direct Student Assistance. UC reports campuses are budgeting 32 percent of basic needs funding for staffing—the largest category of budgeted expenses. Based on campus spending plans, program staff have a variety of roles, including managing basic needs programs, operating basic needs centers (including food pantries), and providing case management to students. In addition to professional staff, many campuses are employing student staff to support basic needs center operations and outreach. After staffing, UC reports the second largest category of budgeted expenses (27 percent) is for direct student assistance, including emergency grants and emergency housing. The remaining funds are budgeted for other program costs, such as equipment and supplies, outreach activities, and evaluation. UC has not reported a similar systemwide breakdown of rapid rehousing funds by expense category. Based on a review of campus spending plans, we estimate a somewhat higher share (more than half) of rapid rehousing funds are going toward direct student assistance.

UC Uses Campus Staff and Facilities to Provide Significant Amount of Housing Assistance. Relative to the other segments, UC is more likely to provide housing assistance using on‑campus resources. For example, nearly all UC campuses employ their own case managers who support housing insecure students and use their own residence halls for emergency housing. Beyond these efforts, UC campuses also work to varying extents with community partners, including nonprofit organizations that provide housing services to the general population. The types of housing assistance that community partners provide (including emergency housing, rental subsidies, case management, and tenant education) appear generally similar to those commonly provided by UC campuses.

Small but Growing Number of UC Students Are Receiving Housing Assistance. Students interested in receiving housing assistance tend to learn about the rapid rehousing and basic needs programs through word‑of‑mouth and campus outreach efforts. These campus outreach efforts include promoting the programs at new student orientations, at campus events, on social media, through faculty and staff, and through peers. In 2022‑23, UC reports 6,604 students received housing assistance through its basic needs program. This represents a small subset of the 78,070 UC students who received any basic needs service, with most of those students likely receiving food assistance. In addition, UC reports its rapid rehousing program served 4,706 UC students, though it indicates there is likely duplication between this count and the count of students served through the basic needs program. The number of UC students receiving housing assistance has increased since 2019‑20, when an estimated 2,150 students received housing assistance through either program.

Campuses Have Discretion in Prioritizing Among Students. UC does not have a systemwide approach for prioritizing among students seeking housing assistance. Instead, campuses have discretion in how they prioritize among students and the amount and duration of assistance they provide. Program administrators at some campuses indicate they have more student demand for housing assistance than they can accommodate, citing funding, staffing, and housing availability as constraints. Some of these campuses indicate they are maintaining program waitlists or using triage systems to differentiate among various levels of student need. Anecdotally, some campuses have shared that they ask interested students to complete an intake form, which can help in tailoring services to them.

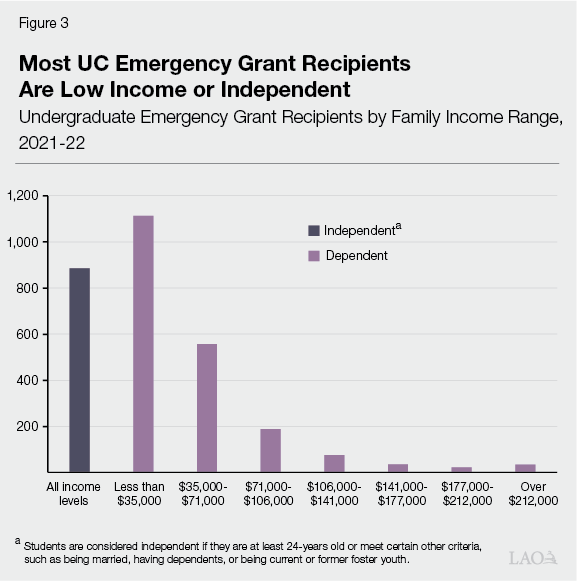

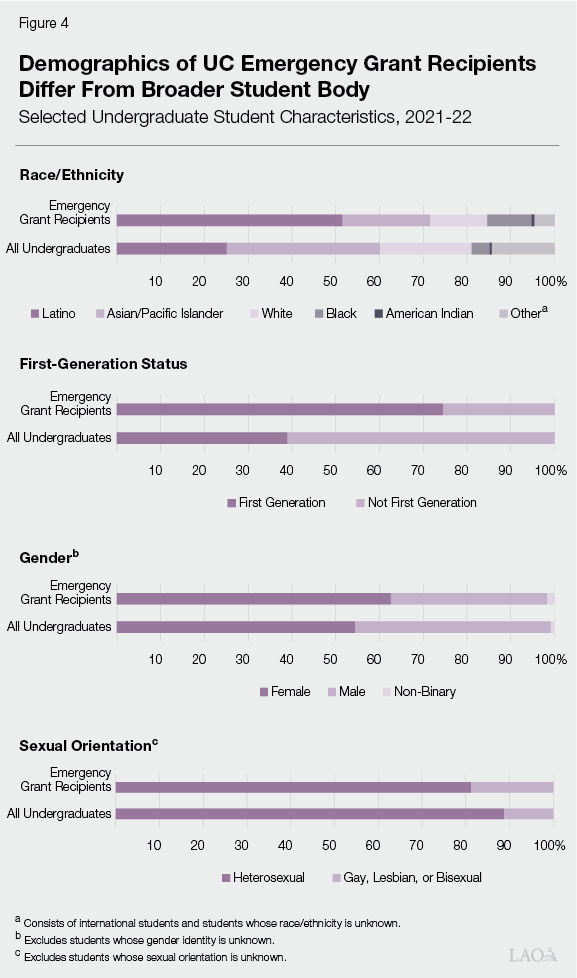

Demographics of Emergency Grant Recipients Differ From Broader Student Body. Though UC is not required to report annually on the demographics of students receiving housing assistance, it did report these data for 2021‑22 in response to a one‑time statutory requirement. The data reported is specific to students receiving emergency grants, excluding students receiving other forms of housing assistance. Of the 3,605 students who received emergency grants in 2021‑22, 2,906 (81 percent) were undergraduates and the remaining were graduate students. As Figure 3 shows, about two‑thirds of undergraduate emergency grants recipients either had a family income of less than $35,000 or were financially independent. Figure 4 compares selected demographic characteristics of the undergraduates who received emergency grants in 2021‑22 with those of UC’s broader undergraduate student body. Compared to the broader student body, emergency grant recipients were more likely to be Latino or Black, first‑generation, female, and LGBTQ. These student groups align with those reporting higher rates of homelessness in UC surveys, except that female students report similar rates of homelessness as male students.

Data on Students’ Academic and Housing Outcomes Are Incomplete. UC’s most recent annual program report includes some outcomes data for the 6,604 students who received housing assistance through the basic needs program in 2022‑23. (UC indicates campuses are not tracking outcomes separately for students who receive housing assistance through the rapid rehousing program.) These outcomes data are reported by campus basic needs staff. Of the 6,604 students, UC estimates at least 1,700 (26 percent) remained enrolled after receiving assistance and at least 400 (6 percent) graduated. UC notes that the academic outcomes data available to basic needs staff varies by campus, which suggests these figures might be inconsistently reported and incomplete. Regarding housing outcomes, UC estimates at least 1,700 students (26 percent) gained permanent housing. UC does not have a consistent definition of gaining permanent housing. Instead, it indicates that campuses may include students in this measure if they signed a lease, maintained housing for at least 30 days, or maintained housing through the end of the term. It is unclear whether students who received assistance to remain in their current housing (rather than to obtain new housing) are included in this measure. Moreover, the housing outcomes data could be incomplete because not all students confirm their housing outcomes after receiving assistance.

CSU

Background on CSU System. The CSU system has 23 campuses, consisting of 22 campuses offering a broad array of academic programs for undergraduate and graduate students, plus one campus that offers a specialized set of maritime‑related programs. CSU currently enrolls a total headcount of approximately 455,000 students. Of the CSU campuses, 7 enroll fewer than 10,000 students, 5 enroll between 10,000 and 20,000 students, and 11 enroll more than 20,000 students. Although variation exists among CSU campuses, many CSU campuses have a majority of their students commuting to campus. In fall 2022, the number of on‑campus beds at CSU equated to 13 percent of all students systemwide, with the share ranging from 4 percent at the Fresno campus to 49 percent at the Sonoma campus. The Maritime campus, which is designed to be residential, had enough beds for all of its students.

At CSU, Rapid Rehousing and Basic Needs Programs Are Distinct. While the rapid rehousing and basic needs programs have significant overlap at UC, they are more distinct at CSU. CSU received ongoing funding for the rapid rehousing program first in 2019‑20. Rather than spreading the initial $6.5 million in rapid rehousing funds across all 23 campuses, CSU chose to allocate it to a subset of campuses that would work with community partners to provide certain types of housing assistance. Then, when CSU began receiving $15 million in ongoing basic needs funds in 2021‑22, it allocated those funds across all campuses to support broader types of assistance (described in more detail later in this section). Nonetheless, the implementation of the two programs is coordinated. At campuses participating in both programs, the programs are typically administered by the same office. When students go to the basic needs center seeking housing assistance, staff determine whether to direct them toward the rapid rehousing program versus other types of housing assistance supported by basic needs funds.

CSU Awarded Rapid Rehousing Funds Competitively to Certain Campuses. Of CSU’s 23 campuses, 14 applied for rapid rehousing funds. The Chancellor’s Office evaluated these applications based on student need at the campus, the availability of community partners, implementation readiness, the planned use of funds, and the method of evaluating the program’s impact. Based on these criteria, CSU initially selected seven campuses (Chico, Long Beach, Pomona, Sacramento, San Diego, San Francisco, and San Jose) to receive funding. These campuses began implementing the rapid rehousing program in 2020‑21. CSU then selected an eighth campus (Northridge) to receive funding beginning in 2021‑22. All eight campuses are receiving annual awards ($870,000 per campus, in most cases) for a grant period lasting through 2023‑24. CSU indicates it is currently developing a request for proposals for a new four‑year grant period beginning in 2024‑25.

At CSU, Rapid Rehousing Funds Support a Specific Model of Housing Assistance. This model is based on the traditional rapid rehousing model for moving people who are homeless into permanent housing. Every participating CSU campus is working with one to two community partners to implement this model. For example, the Long Beach, Northridge, and Pomona campuses are all working with Jovenes, Inc., an organization that provides support services to youth experiencing homelessness in Los Angeles County. Meanwhile, the Chico campus is working with two organizations, True North Housing Alliance and the Chico Housing Action Team, both of which provide support services to people experiencing homelessness in Butte County. Typically, students seeking housing assistance first interact with campus staff. Campus staff determine whether to refer students to a community partner for enrollment in rapid rehousing. For students who are referred, the community partner provides housing identification, rental subsidies, and case management.

Rapid Rehousing Funds Are Used by Campuses and Community Partners. Of each campus’s annual funding allocation, 25 percent is retained by the campus and 75 percent goes to its community partner. At both campuses and community partners, the rapid rehousing funds support program staffing and administration as well as direct student assistance (including rental subsidies). Based on a data request to CSU, campuses on average spent about two‑thirds of their 2022‑23 allocations on program staffing and administration while spending one‑third on direct assistance, though this varied notably among campuses. In contrast, community partners on average spent about one‑third of their 2022‑23 funding allocation on program staffing and administration while spending two‑thirds on direct assistance, also with notable variation among organizations. In the first two years of the program, CSU reports that participating campuses added a total of 15 new staff positions, while their community partners added a total of 18 new staff positions. CSU indicates significant staffing is required to provide case management services to students.

CSU Rapid Rehousing Program Serves Small Number of High‑Need Students. CSU’s rapid rehousing program is targeted toward students who are homeless or otherwise facing long‑term housing challenges. Campuses direct only a small share of students seeking housing assistance to community partners for enrollment in the rapid rehousing program. Most students instead receive other forms of housing assistance from the campus, such as temporary emergency housing or one‑time emergency grants through the basic needs program. Across the first two years of the rapid rehousing program’s implementation (2020‑21 and 2021‑22), CSU reports 2,725 students engaged with program staff on campus. Of these students, 342 were referred to a community partner and eventually enrolled in the rapid rehousing program, while the remaining students received other forms of assistance.

CSU Tracks Housing and Academic Outcomes of Rapid Rehousing Participants. Of the 342 students who enrolled in the rapid rehousing program across the first two years of implementation, CSU reports that 173 students (51 percent) moved into permanent housing. CSU indicates it considers students to have moved into permanent housing once they are paying for their own housing independently from the program. (This differs from the definitions used by UC.) Of the 342 students, CSU reports 162 students (47 percent) remained enrolled in school at the end of the second year, and 97 students (28 percent) had graduated. The remaining 83 students (24 percent) were no longer participating in the rapid rehousing program, and it is not known whether they remained enrolled in school or had dropped out.

CSU Allocates Basic Needs Funds to All Campuses. In 2021‑22 (two years after the state began providing rapid rehousing funds), the state also began providing ongoing basic needs funds to CSU. While only 8 CSU campuses are receiving funding for rapid rehousing, all 23 campuses are receiving funding for basic needs. CSU allocated the initial $15 million ongoing for basic needs to all campuses based on the number of Pell Grant recipients at each campus. Then, after receiving a $10 million ongoing augmentation for basic needs in 2022‑23, CSU allocated the additional funds to all campuses based on the number of students with zero expected family contribution—a federal measure that identifies students with the greatest financial need. Under this approach, basic needs allocations ranged from about $26,000 at the Maritime campus to $2.9 million at the Long Beach campus in 2022‑23 (the most recent year reported).

CSU Basic Needs Funds Support Various Types of Housing Assistance. CSU reports all campuses are offering some form of housing assistance through the basic needs program. Nearly all campuses offer on‑campus emergency housing for temporary stays, typically between two weeks to one semester. Most campuses also offer off‑campus emergency housing, including for students with children or other circumstances not well‑suited to residence halls. Campuses also commonly provide emergency grants for housing. In addition, some campuses are using basic needs funds for long‑term housing assistance (such as ongoing rental subsidies), though this is somewhat less common than emergency assistance.

Housing Assistance Accounts for Small Share of CSU Basic Needs Services. CSU reports about 14,000 students received some form of housing assistance through the basic needs program in 2022‑23. This number is relatively small compared to the number of students accessing food pantries (67,500) or receiving CalFresh application support (22,835) through the basic needs program that year. To date, CSU has not reported on the demographics of students accessing housing assistance or other basic needs services.

Efforts Are Under Way to Collect Outcomes Data on CSU Basic Needs Recipients. Whereas CSU’s rapid rehousing reports include academic and housing outcomes of students participating in that program, CSU’s basic needs reports do not contain comparable data. Program administrators indicate efforts are underway to develop a standard approach across campuses for better tracking student participation in basic needs services and evaluating the impact of those services on student outcomes. While these evaluation efforts remain in early stages, CSU notes that nearly 90 percent of the 20,000 students who accessed basic needs services (including, but not limited to, housing assistance) in fall 2022 remained enrolled the subsequent term.

CCC

Background on CCC System. The CCC system consists of 116 community colleges. Of these colleges, 115 offer a broad array of lower division academic programs and career technical education programs. Each of these colleges is locally governed by one of 72 community college districts. The one remaining college is a fully online statewide college governed at the state level. CCC currently enrolls a total annual headcount of approximately 1.9 million students. Of the colleges, 27 enroll fewer than 10,000 students, 47 enroll between 10,000 and 20,000 students, and 42 enroll more than 20,000 students. Nearly all community college students are commuters. Only 13 community colleges currently offer on‑campus housing, with most of these located in rural areas that are more difficult to access (due to geography and weather) than other campuses. These 13 colleges combined have about 2,700 beds.

Rapid Rehousing and Basic Needs Programs Are Also Distinct at CCC. CCC’s approach to administering the rapid rehousing and basic needs programs is generally similar to CSU’s approach. Like CSU, CCC has allocated rapid rehousing funds to a subset of colleges to provide targeted housing assistance, while allocating basic needs funds across all colleges to provide a broader range of assistance. CCC is also similarly working with community partners to implement the rapid rehousing program.

CCC Awarded Rapid Rehousing Funds Competitively to Certain Colleges. Of the 116 community colleges, 64 applied to participate in the rapid rehousing program after it was initially created. The CCC Chancellor’s Office evaluated the applications based on several metrics related to county‑level need (such as the percentage of the county population living below the poverty line) and institutional need (such as the percentage of students who are Pell Grant recipients, foster youth, veterans, or students with disabilities). As Figure 5 shows, CCC selected an initial cohort of 14 colleges, with their award amounts based entirely on college size. After the state significantly increased funding for the rapid rehousing program in 2022‑23, CCC used similar metrics to select 14 additional colleges and invited them to participate in a second cohort. Of the 14 colleges invited, 11 chose to participate. Each college in the second cohort received a base amount of funding ($150,000), with the remaining funds allocated based on student headcount.

Figure 5

25 Community Colleges Currently Are

Receiving Rapid Rehousing Funds

2023‑24 Allocations (In Thousands)

|

Campus |

Allocation |

|

Cohort 1 |

|

|

Antelope Valley College |

$700 |

|

Butte College |

700 |

|

Cerritos College |

700 |

|

Long Beach City College |

700 |

|

Los Angeles Southwest College |

700 |

|

Riverside City College |

700 |

|

Fresno City College |

700 |

|

Victor Valley College |

700 |

|

Modesto Junior College |

700 |

|

Imperial Valley College |

600 |

|

San Diego City College |

600 |

|

Barstow College |

500 |

|

Gavilan College |

500 |

|

College of the Redwoods |

500 |

|

Subtotal |

($9,000) |

|

Cohort 2 |

|

|

American River College |

$1,864 |

|

Santa Rosa Junior College |

1,361 |

|

Southwestern College |

1,099 |

|

Santa Barbara City College |

1,085 |

|

Los Angeles Trade‑Tech College |

904 |

|

San Bernardino Valley College |

797 |

|

Los Angeles Harbor College |

641 |

|

Shasta College |

625 |

|

Oxnard College |

587 |

|

College of Marin |

474 |

|

West Hills Lemoore College |

393 |

|

Subtotal |

($9,830) |

|

Total |

$18,830 |

Participating Colleges Are Working With Community Partners on Rapid Rehousing. Each college participating in the CCC rapid rehousing program has developed or is developing a memorandum of understanding with at least one community partner. In these partnerships, the college tends to focus on student intake and academic support while relying on community partners to provide housing assistance. Program administrators suggest this approach allows each agency to focus on the areas in which they have greatest expertise. Specific partnership arrangements vary among participating colleges. For example, Cerritos College directs a majority of its annual rapid rehousing funds to its community partner, Jovenes, Inc. In turn, Jovenes, Inc. uses a small portion of funds for staffing, then uses the remainder for direct assistance (including ongoing rental subsidies, move‑in assistance, and short‑term grants to prevent homelessness). Some other colleges have partnerships that are narrower in scope, such as providing funding to a community partner to support one staff position that helps students find housing and provides tenant education workshops.

Colleges Are Using Rapid Rehousing Funds for Various Types of Housing Assistance. The CCC Chancellor’s Office reports colleges and their community partners are implementing the key components of the traditional rapid rehousing model, consisting of housing identification, rental subsidies, and case management. In addition, colleges are using rapid rehousing funds to provide other forms of housing assistance, including temporary emergency housing. Assistance through CCC’s rapid rehousing program is available to students who are either homeless or housing insecure and at imminent risk of becoming homeless.

CCC Is Tracking Some Outcomes for Rapid Rehousing Recipients. CCC reports its implementation of the rapid rehousing program was delayed after the onset of the pandemic. Given these delays, the first year for which CCC reported program data was 2021‑22. In that year, CCC reports the 14 colleges in the first cohort provided housing assistance to 519 students, consisting of 224 students who were homeless and 295 students who were housing insecure. Of the 519 total students, CCC reports that 116 students (22 percent) subsequently maintained stable housing for at least six months. It is unclear whether the remaining students were unable to maintain stable housing or whether program staff lacked data on their housing outcomes. CCC has not reported academic outcomes for students receiving assistance through the rapid rehousing program. CCC indicates it is beginning to collect program data centrally using its student information system, which will allow for improved reporting in future years.

Since 2021‑22, All Colleges Have Received Funding for Basic Needs Centers. In 2021‑22, the state enacted a requirement for every college to designate a basic needs coordinator and establish a basic needs center that serves as a central location on campus for students to access related resources. (The requirement applies to CCC only, but all UC campuses and most CSU campuses also have basic needs centers.) The state provides ongoing funding to CCC to support this requirement. CCC allocates these basic needs funds by formula to all 115 colleges with a physical campus. Under the formula, CCC first provides each college with a base amount of funding ($130,000), then allocates half of the remaining funds based on the total number of students enrolled and the other half based on the number of Pell Grant recipients. Under this approach, college allocations in 2023‑24 ranged from $157,255 at Feather River College to $978,124 at Mount San Antonio College.

Basic Needs Funding Supports Staffing, Operations, and Direct Assistance. Similar to UC, the largest expense category for basic needs funding at CCC is staffing. In 2021‑22, colleges reported spending 56 percent of basic needs funding on salaries and benefits. Colleges also spent a combined 32 percent of basic needs funding on supplies and materials (including food pantry supplies), other operating expenses, and capital outlay. A small share of basic needs funds (about 12 percent) went toward direct student assistance, such as emergency grants, grocery store gift cards, and transit vouchers.

Housing Assistance Accounts for Small Share of CCC Basic Needs Services. To date, CCC has reported program participation data from basic needs centers at 60 colleges. Students at these colleges accessed housing assistance 4,156 times during summer and fall 2022, with housing assistance representing about 6 percent of the 64,777 contacts for basic needs services during that time. (As at the other segments, food assistance was by far the most common category of basic needs service provided at colleges.) The specific types of housing assistance provided vary by college. Examples include emergency grants for housing costs and referrals to housing resources in the community. Based on conversations with program administrators, the housing assistance provided by colleges using basic needs funds is typically short term, in contrast to the ongoing rental subsidies that may be provided using rapid rehousing funds.

CCC Is Beginning to Collect Data on Students Receiving Basic Needs Services. As with the rapid rehousing program, CCC is beginning to track participation in the basic needs program through its student information system. This allows it to link program participation to student demographic data and academic outcomes. Based on data from the 60 colleges that participated in the first round of reporting, students receiving any basic needs service in summer and fall 2022 generally resembled the broader student population in terms of race/ethnicity, gender, and age group. (Demographic data were not reported for students receiving housing assistance specifically.) Regarding academic outcomes, CCC reports students receiving any basic needs service had an average course success rate in fall 2022 of 66 percent, compared to 71 percent for the broader student body. Because CCC began to track basic needs participation in 2022‑23, persistence and graduation data were not yet available at the time the first report was due in May 2023. The report also does not cover housing outcomes for participating students.

Improving Reporting Requirements

Reports Provide Some Helpful Program Information. The rapid rehousing and basic needs reports the segments have submitted to the Legislature to date include some key information. The reports generally identify how the segments are allocating funds among campuses and describe how campuses are using program funds, including the types of services provided and, in some cases, the associated expenditures. The available data indicate the segments are using a notable share of program funds to support staffing and other operational costs, in addition to direct student assistance. The reports also provide some data on the number of students served. These data indicate that each segment is serving a small number of housing insecure students. Some of these students are served entirely by on‑campus services, including temporary on‑campus emergency housing or emergency grants. Other students are referred by on‑campus staff to off‑campus community partners that help with finding and covering the cost of housing.

State Has Incomplete Data for Evaluating Program Effectiveness. Although the required reports provide some information on the services provided through the rapid rehousing and basic needs programs, less data have been provided to date on program outcomes. While this is partly because these programs are relatively new and the segments are still working to improve data collection, it is also because of gaps in statutory reporting requirements. As Figure 6 shows, current reporting requirements are inconsistent among segments and programs, leaving key information missing. For example, CCC is the only segment required to report annually on the number and demographics of students receiving basic needs services. Furthermore, the requirements for the segments to track participants’ housing and academic outcomes are vague. In most cases, statutory language suggests possible outcome measures (“such as persistence or completion” or “such as the number of students that were able to secure permanent housing”) without requiring the segments to use any of them specifically. The suggested measures also are not clearly defined, leading to inconsistencies in how these measures are interpreted across and even within segments. For example, in collecting data on housing outcomes, campuses have interpreted “securing permanent housing” to mean anything from signing a lease to maintaining housing for at least six months.

Figure 6

Current Reporting Requirements Vary by Program and Segment

Data Required to Be Submitted in Annual Program Reports

|

Rapid Rehousing |

Basic Needsa |

|||

|

All Segments |

UC and CSU |

CCC |

||

|

Campus funding allocations |

Distribution of funds by campus. |

Distribution of funds by campus. |

— |

|

|

Use of funds |

Description of the types of services funded. Number of coordinators hired. |

Description of the types of services funded. List of campuses offering emergency housing or long‑term housing assistance. Programmatic budget by campus. |

Description of the types of services funded. |

|

|

Participation |

Number of students served by campus. |

— |

Number of students served. |

|

|

Demographics of participants |

— |

— |

Socioeconomic and demographic backgrounds of students served.b |

|

|

Housing outcomes |

Relevant outcomes, such as the number of students that were able to secure permanent housing.c |

An analysis describing how funds reduced homelessness among students.c |

— |

|

|

Academic outcomes |

Relevant outcomes, such as whether students remained enrolled or graduated.c |

If feasible, an analysis describing how funds impacted student outcomes such as persistence or completion.c |

Whether students remained enrolled or graduated. |

|

|

aIn addition to these measures, the segments are required to report certain information specific to food assistance and student mental health services, how they leveraged or coordinated with other state or local resources (UC and CSU only), and other findings and best practices. bCCC has discretion to determine what specific student characteristics it reports. cThe segments have discretion to determine the specific outcomes they report. |

||||

Recommend Refining Statutory Reporting Requirements for Both Programs. Given the above gaps and inconsistencies, we recommend refining the statutory reporting requirements. Figure 7 shows an illustrative set of data that the state could require of all three segments for both the rapid rehousing and basic needs programs. The Legislature could continue to require the segments to report on campus funding allocations and the use of program funds. It could also require the segments to report participation data for each of their campuses. In addition, the Legislature could require each segment to report systemwide data on the demographics of students receiving housing assistance, allowing it to monitor whether programs are reaching the students most likely to be facing housing challenges. Furthermore, it could require each segment to report on a consistent and clearly defined set of certain housing and academic outcomes for participating students, disaggregated by campus. This would allow the Legislature to better understand the extent to which program objectives were being met. Improved outcomes data also would help the Legislature compare the cost‑effectiveness of these programs by campus and potentially identify campuses with promising approaches that could be replicated. Though we recommend the Legislature statutorily require the segments to provide data in all of the key areas of funding, participation, and outcomes, it may want to add or refine outcome measures as it learns more about housing programs across the state.

Figure 7

Illustrative Reporting Requirements on

Housing Assistance

Rapid Rehousing and Basic Needs Programs at UC, CSU, and CCC

|

Topic |

Required Dataa |

|

Campus funding allocations |

|

|

Use of funds |

|

|

Participation |

|

|

Demographics of participants |

|

|

Housing outcomes |

|

|

Academic outcomes |

|

|

aSegments would be required to report participation and outcomes data by campus. bStudents would be considered homeless if they lack a stable place to live at night, including if they are couch surfing or staying at hotels or motels, in emergency shelters or transitional housing, and in places not meant for habitation (such as cars or tents). Students would be considered housing insecure (but not homeless) if they are experiencing other housing challenges, such as difficulty paying rent or utilities, overcrowding, and needing to move frequently. |

|

Recommend Aligning Report Due Dates Across Programs. Currently, the due dates of the annual reports on rapid rehousing and basic needs vary across segments and programs, as Figure 8 shows. In some cases, these due dates hinder program oversight. At CSU and CCC, the rapid rehousing and basic needs reports have different due dates, leading these segments to report separately on the two programs despite their overlapping goals and activities. In addition, the CCC rapid rehousing and basic needs reports are likely due too late in the state budget process to inform the Legislature’s decisions, while the CSU rapid rehousing report has no due date at all. We recommend requiring each segment to submit one consolidated report covering the two related programs by the spring following the close of each fiscal year. Setting a due date of no later than April 1 annually for each segment’s report would likely allow sufficient time for these reports to inform state budget decisions for the upcoming year.

Figure 8

Existing Due Dates Vary by

Program and Segment

Statutory Due Dates for Annual Reports

|

Rapid Rehousing |

Basic Needs |

|

|

UC |

February 1 |

February 1 |

|

CSU |

Unspecified |

March 1 |

|

CCC |

July 15 |

May 1 |