July 1, 2024

Assessing Community College Programs

at State Prisons

Executive Summary

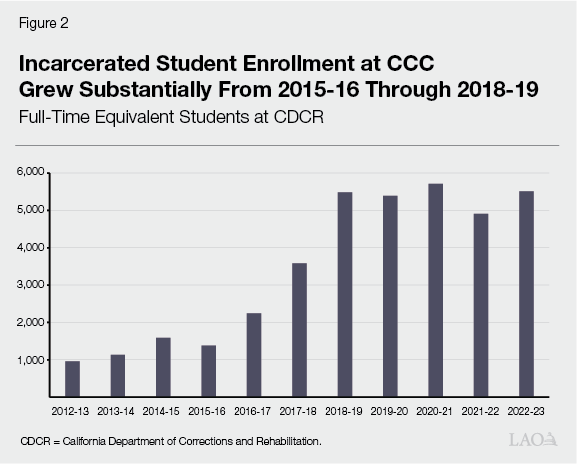

State Began Funding In‑Person Community College Instruction at State Prisons a Decade Ago. Prior to 2014, California Community Colleges (CCC) tended to provide only correspondence courses at state prisons. This was because colleges could receive state funding only for courses that were open to the general public. In 2014, the state approved Chapter 695 (SB 1391, Hancock), which allowed community colleges to receive state funding for in‑person courses at state prisons (even though those courses were closed to the general public). In the ensuing years, the availability of in‑person CCC courses in state prisons expanded significantly. Currently, 22 community colleges (about 30 percent of all community colleges) partner with the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) to provide in‑person courses. Most of these CCC programs lead to an associate degree, typically in the humanities, social sciences, and business. Throughout this period, CCC enrollment at state prisons increased markedly. Whereas about 1,400 full‑time equivalent (FTE) students were enrolled in 2015‑16, nearly 5,500 FTE students were enrolled in 2018‑19—reflecting a near quadrupling of enrollment within just four years.

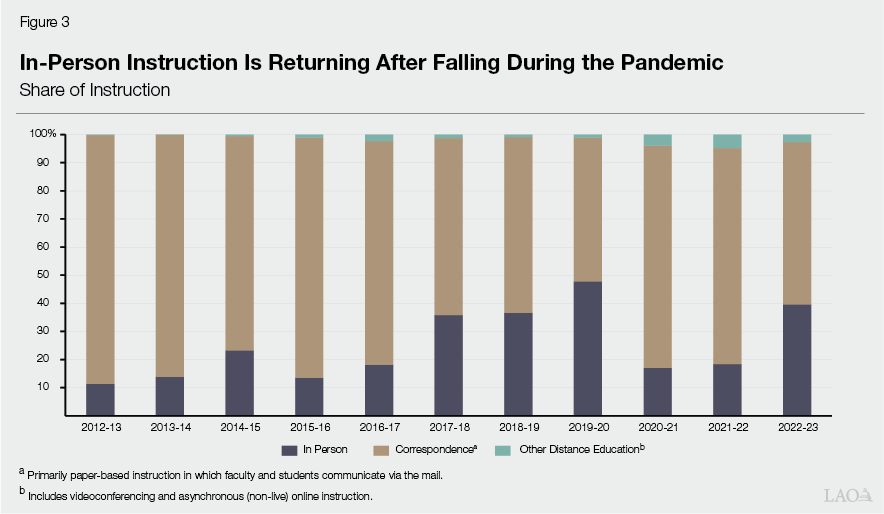

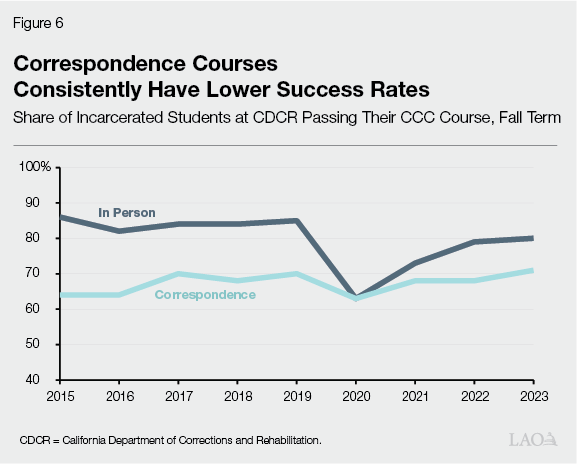

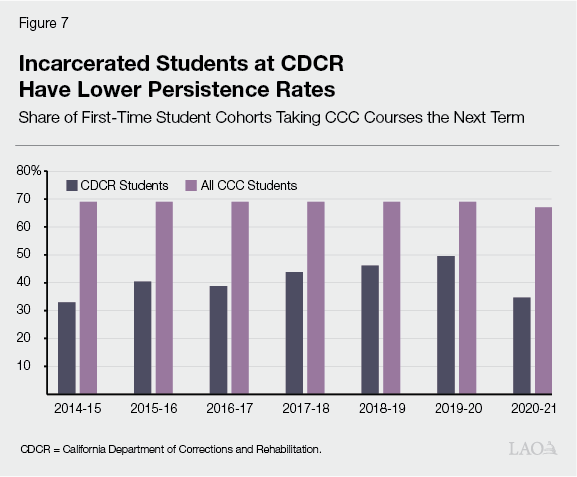

Student Outcomes in These Programs Are Mixed. In 2022‑23, 40 percent of CCC instruction at state prisons was delivered in person whereas 60 percent was delivered not in person (mostly through correspondence courses). As part of our analysis, we collected data on student outcomes. The data show that course success rates for CCC students at state prisons are about the same as the rates for CCC students overall. Success rates for correspondence courses at state prisons, however, are notably lower than for in‑person courses at state prisons. Term‑to‑term persistence rates for CCC students at state prisons also are much lower than for CCC students overall. Moreover, CCC graduation rates at state prisons are lower than for the CCC system overall, and the average time to degree among incarcerated students is longer. Data are lacking regarding the extent to which CCC programs are leading to some other key objectives, including reductions in recidivism, increases in employment, and higher wages for those released from CDCR.

Anecdotally, Students and Staff Believe CCC Programs Have Several Positive Aspects. Some research conducted at other correctional settings has identified benefits to postsecondary education during incarceration, including reductions in recidivism rates. To date, CDCR, however, has not conducted a rigorous evaluation of the impacts of CCC programs. As part of our assessment of these programs, we visited several state prisons and interviewed students and staff. Incarcerated students we interviewed indicated that these programs helped them develop critical thinking skills and enhance communication with their families. CDCR staff indicated that these programs created a better prison atmosphere and made incarcerated students more productive with their time. In addition, community college faculty noted that students tended to be motivated and generally came prepared for class. We also identified that several CCCs are piloting online models for incarcerated students that appear promising alternatives to correspondence courses.

These Programs Have a Number of Problems and Missed Opportunities. In assessing CCC programs at state prisons, we identified several problems, which the figure at the end of this box summarizes. Regarding enrollment, we discovered that some programs use a first‑come, first‑served approach rather than prioritizing those individuals without a first degree who are close to release. We also found that CDCR lacks a comprehensive assessment of its utilization of classroom space by prison, which could be inhibiting colleges’ ability to further expand their in‑person course offerings. Additionally, despite the state spending tens of millions of dollars annually to support CCC programs in state prisons, the state does not link any of this funding to student success. (By comparison, the state links funding to student success for nearly all student groups outside of the prisons.) Another missed opportunity is that the state is not leveraging available federal funding for college education at prisons. A final problem we identified is that CCC programs at state prisons lack an evaluation component.

Recommend Adopting Changes to Improve Programs. We recommend the Legislature take certain actions in response to these problems and missed opportunities. These recommendations also are included in the figure at the end of this box. Most of the recommendations we make could be adopted and implemented immediately. A few of the recommendations could take more time to implement and would place some new administrative requirements on CCC and CDCR. Overall, our recommendations would result in modest state General Fund savings (both to CCC’s and CDCR’s budgets), while incentivizing better student outcomes and improving legislative oversight.

Summary of Assessment and Recommendations for CCC Programs at State Prisons

|

Component |

Assessment |

Recommendation |

|

Enrollment prioritization |

Demand for CCC courses among incarcerated people generally exceeds supply, yet some colleges do not give enrollment priority to those people most likely to benefit. |

Adopt statutory enrollment priorities that apply at all state prisons. Give priority to students who are closest to obtaining their first degree and within five years of release. This approach could improve individuals’ post‑release outcomes, including by reducing the risk of recidivism and improving job prospects. |

|

Space utilization |

CDCR and CCC report a lack of sufficient space to hold in‑person courses, yet CDCR lacks a comprehensive assessment of its space utilization. |

Adopt statutory space and utilization standards. Direct CDCR to collect data and report biennially on space utilization. |

|

Online pilots |

Given the generally poor outcomes of correspondence courses, some community colleges and CDCR are working together to pilot new online instructional models. |

Require CCC and CDCR to report on pilot outcomes, including course success rates compared with in‑person and correspondence courses and impact on faculty recruitment to teach high‑demand courses in prisons. |

|

State funding |

State’s current CCC funding model lacks a strong incentive for colleges to promote incarcerated student success. |

Modify CCC funding formula to include a performance component. In the meantime, require CCC to report enrollment and outcomes data for incarcerated students. |

|

Federal funding |

State is missing an opportunity to draw down federal funds to support prison education costs. |

Begin charging incarcerated students to attend CCC and use federal Pell Grant funds to offset enrollment fees, textbooks, computers, and other allowable education costs. |

|

Program evaluation |

The state lacks an evaluation analyzing the impact of CCC education programs on recidivism, employment, and wages. |

Require CDCR to annually report data on recidivism, employment, and wage outcomes by educational program, provider, and risk level of reoffending. In addition, require CDCR to use external evaluators to assess the impact of CCC programs every five to ten years. |

|

CDCR = California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. |

||

Introduction

Report Focuses on Community College Programs at California’s Prisons. While incarcerated in prison, people often participate in various rehabilitation programs. Rehabilitation programs seek to improve the likelihood that people will lead productive, crime‑free lives upon their release from prison. These programs are intended to address the underlying factors that led to their criminal activity. These programs include substance use disorder treatment and anger management, as well as a range of programs aimed at cultivating academic skills and potential future employment opportunities. In this report, we focus on California Community College (CCC) programs at California’s state prisons. Notably, it has been ten years since the Legislature passed legislation allowing community colleges to receive state funding for providing instruction inside state prisons. In accordance with this legislation, the availability of postsecondary courses in state prisons has expanded significantly and incarcerated student enrollment has almost quadrupled. In this report, we first provide relevant background, cover key student trends at state prisons, and explain how CCC education programs at state prisons are funded. We then assess the strengths and weaknesses of these programs and conclude with recommendations aimed at improving them.

Background

In this section, we provide background on (1) community colleges, (2) the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), and (3) the educational partnership between CDCR and community colleges.

California Community Colleges

Community Colleges Are Located Throughout the State. The CCC system is the largest of California’s three public higher education segments in terms of both number of campuses and students. The system consists of 115 colleges operated by 72 locally governed districts. (The CCC system also has one statewide online college.) The state provides districts with significant autonomy in matters such as determining course offerings, hiring and compensating staff, and managing district property. The CCC system is overseen by a state‑level Board of Governors, which appoints a Chancellor to run day‑to‑day operations at the Chancellor’s Office (located in Sacramento).

Community Colleges Have a Broad Mission. Community colleges offer a breadth of academic programs, including lower‑division transferable coursework, career technical education, and literacy and other precollegiate basic skills instruction. Statute also allows community colleges to offer baccalaureate degrees in certain occupational fields as long as they do not duplicate the programs offered by the University of California (UC) or the California State University (CSU). In 2022‑23, community colleges provided instruction to about 1.9 million students in headcount terms (1 million full‑time equivalent, or FTE, students). The vast majority of CCC students are adults taking courses that are open to the public. Some CCC students, however, are younger, being dually enrolled in CCC and high school courses. Other CCC students are incarcerated (either in state prison, a local jail, or another correctional facility) and enrolled in courses that are not open to the public.

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

CDCR Operates State Prisons. As of the end of March 2024, CDCR was responsible for incarcerating a total of about 93,000 people convicted of certain serious or violent felonies. Most of these people (97 percent) are housed in one of the 32 prisons owned and operated by the state. Currently, the state has 30 men’s prisons and 2 women’s prisons. The remaining people incarcerated by the state are housed in various specialized facilities outside of prisons, such as conservation camps and community reentry facilities. Depending on the severity of the crime and several other factors (including the length of court proceedings), people can spend less than one year in prison or the remainder of their life. On average, a person spends about three to four years in prison before release.

CDCR Offers Rehabilitation Programs to Reduce Recidivism, Among Other Benefits. Some people reoffend after they are released from prison. Specifically, of the roughly 36,000 people released from California’s state prisons in 2018‑19, about 15,100 (42 percent) were convicted of a subsequent crime within three years of release. The primary goal of rehabilitation programs is to reduce the level of recidivism—the number of people that reoffend after release. If rehabilitation programs are successful at reducing recidivism, they in turn can result in fiscal benefits to the state, such as reducing incarceration costs and increasing employment. In addition, rehabilitation programs can serve other goals, such as increasing individuals’ educational attainment and reducing the prevalence of substance use disorders. Our report, Improving In‑Prison Rehabilitation Programs, provides more information on best practices for reducing recidivism.

State Law Requires CDCR to Make Education Programs Available at All Prisons. State law makes education programs a part of CDCR’s mission and governs how CDCR is to provide those programs. In compliance with state law, each prison offers adult basic and secondary education using CDCR‑employed teachers, librarians, and support staff. Many prisons also use CDCR staff to provide vocational education (such as plumbing and welding). Beyond these types of instruction, state law tasks CDCR with making postsecondary programs available at every prison for people who have obtained a high school diploma or equivalent. Specifically, Chapter 766 of 2021 (SB 416, Hueso) requires that postsecondary instruction be provided by CCC; CSU; UC; or other regionally accredited, nonprofit colleges or universities. Chapter 766 further requires CDCR to prioritize postsecondary programs that provide face‑to‑face instruction at no cost to incarcerated students (or their families) and provide comprehensive support services, such as advising and tutoring.

CDCR‑CCC Partnership

CDCR Has Agreements With Community Colleges for In‑Person Instruction. Figure 1 shows the 22 public community colleges providing in‑person instruction at 31 of the 32 state prisons, along with one nonprofit, two‑year college that provides in‑person instruction at the remaining state prison. Generally, prisons are located within the CCC district boundaries of their partnering college. A uniform memorandum of understanding (MOU) between each CDCR prison and its partnership community college outlines the responsibilities of each entity. As set forth in the MOU, community colleges are responsible for student enrollment, faculty recruitment, and instruction, while CDCR is responsible for identifying potential students, providing classroom space and classroom technology, and maintaining safety within the classroom. CDCR generally has discretion regarding when and where CCC instruction can take place within a prison. Based on CDCR practice, CCC courses are generally restricted to the afternoons and evenings—reserving mornings for other CDCR rehabilitation programs.

Figure 1

About Two Dozen Community Colleges Provide

In‑Person Instruction to Incarcerated Students at

State Prisons

As of April 2024

|

Prison |

Community College |

|

Avenal State Prison |

Coalinga |

|

California Correctional Institution (Tehachapi) |

Cerro Coso |

|

California Health Care Facility (Stockton) |

Modesto |

|

California Institution for Men (Chino) |

Chaffey |

|

California Institution for Women (Corona) |

Chaffey |

|

California Medical Facility (Vacaville) |

Solano |

|

California Men’s Colony (San Luis Obispo) |

Cuesta |

|

California Rehabilitation Center (Norco) |

Norco |

|

Calipatria State Prison |

Imperial Valley |

|

Central California Women’s Facility (Chowchilla) |

Merced |

|

Chuckawalla Valley State Prison (Blythe) |

Palo Verde |

|

Correctional Training Facility (Soledad) |

Hartnell |

|

California State Prison, Centinela (Imperial) |

Imperial Valley |

|

California State Prison, Corcoran |

Bakersfield |

|

California State Prison, Los Angeles (Lancaster) |

Antelope Valley |

|

California State Prison, Sacramento (Represa) |

Los Rios CCDa |

|

California State Prison, Solano (Vacaville) |

Solano |

|

Folsom State Prison (Represa) |

Los Rios CCDa |

|

High Desert State Prison (Susanville) |

Lassen |

|

Ironwood State Prison (Blythe) |

Palo Verde |

|

Kern Valley State Prison (Delano) |

Bakersfield |

|

Mule Creek State Prison (Ione) |

Los Rios CCDa |

|

North Kern State Prison (Delano) |

Bakersfield, Porterville |

|

Pelican Bay State Prison (Crescent City) |

Redwoods |

|

Pleasant Valley State Prison (Coalinga) |

Coalinga |

|

Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility (San Diego) |

Southwestern |

|

Salinas Valley State Prison (Soledad) |

Hartnell |

|

San Quentin Rehabilitation Center |

Mount Tamalpais (private college) |

|

Sierra Conservation Center (Jamestown) |

Columbia |

|

Substance Abuse Treatment Facility (Corcoran) |

Bakersfield |

|

Valley State Prison (Chowchilla) |

Merced |

|

Wasco State Prison |

Bakersfield |

|

aCan include faculty from district’s four colleges. |

|

|

CCD = Community College District. |

|

Prisons Also Have Arrangements With Certain Colleges to Provide Correspondence Courses. Currently, few community colleges offer online courses to students at state prisons. Instead, the most common form of distance learning continues to be correspondence courses. Five community colleges (Coastline, Feather River, Lake Tahoe, Lassen, and Palo Verde) provide the bulk of correspondence‑based instruction to the state prisons. These colleges generally have a broad reach. For example, Coastline College and Lassen College indicate they enroll at least one student from every or nearly every state prison. While the correspondence delivery model relies primarily on paper‑based instructional and assignment packages, in some cases instruction is delivered via closed circuit television within the prison. Under the correspondence model, the college typically uses a mailing service to send completed and graded assignments back and forth between the instructor and students.

Course Offerings Are Concentrated in a Few Academic Disciplines. Whether offered in person or via correspondence, CCC programs for students at state prisons primarily focus on providing courses leading to associate degrees in the humanities, social sciences, and business. Currently, few community colleges offer science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) degree programs to students at state prisons. Beyond the associate degree, we identified one community college—Bakersfield College—that is starting an in‑person bachelor’s degree program in industrial automation at one of the prisons. The Chancellor’s Office indicates other colleges might also be in the midst of initiating additional bachelor’s degree programs at state prisons. (As covered in the text box below, other colleges and universities offer various postsecondary programs, including bachelor’s degree programs, to students at state prisons.)

Additional Postsecondary Education Opportunities

An Increasing Number of Bachelor’s Degree Programs Are Offered In Person at State Prisons. Beyond partnering with community colleges, some state prisons have partnered with other colleges and universities to offer in‑person bachelor’s degree programs. For example, since 2014, Pitzer College, a private nonprofit institution, has been offering tuition‑free, in‑person courses that lead to a bachelor’s degree at the California Rehabilitation Center in Norco. In addition, the 2022‑23 Budget Act provided the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) $5 million one time and $4.7 million ongoing General Fund to offer tuition‑free, in‑person courses leading to a bachelor’s degree through the California State University (CSU) at seven prisons. More recently, a University of California campus (Irvine) has begun to offer tuition‑free, in‑person, bachelor’s degree coursework at a state prison. The nearby figure lists the prisons that currently have in‑person bachelor’s degree programs.

Nine State Prisons Offer In‑Person Bachelor’s Degree Programs

As of January 2024

|

Prison |

University |

|

California Institution for Women (Corona) |

CSU Los Angeles |

|

California Rehabilitation Center (Norco) |

Pitzer College |

|

California State Prison, Los Angeles (Lancaster) |

CSU Los Angeles |

|

Central California Women’s Facility (Chowchilla) |

CSU Fresno |

|

Folsom State Prison (Represa) |

CSU Sacramento |

|

Mule Creek State Prison (Ione) |

CSU Sacramento |

|

Pelican Bay State Prison (Crescent City) |

CSU Humboldt |

|

Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility (San Diego) |

UC Irvine |

|

Valley State Prison (Chowchilla) |

CSU Fresno |

Bachelor’s and Graduate Degrees Also Are Available Through Correspondence Programs. In addition to in‑person courses, incarcerated students can pursue bachelor’s degrees and master’s degrees through certain postsecondary institutions that offer correspondence courses. For example, some people incarcerated in a CDCR prison have reported earning master’s degrees through correspondence courses offered by Adams State University (located in Colorado). In addition, CSU Dominguez Hills recently began offering coursework primarily through correspondence and online modalities leading to a master’s degree in the humanities. CSU Dominguez Hills reports that 33 students across 11 prisons enrolled in the program in fall 2023. Typically, the student or the family cover tuition and associated costs, such as textbooks, for these types of programs.

Students

In this section, we cover enrollment in community college programs offered at state prisons and student outcomes in those programs.

Enrollment

Incarcerated People Who Have Completed High School‑Level Education Are Eligible to Be CCC Students. Upon arriving at state prison to begin serving a sentence, people are assessed for their rehabilitative needs, among other things. Many incarcerated people are assigned to mandatory CDCR‑provided rehabilitation programming, such as substance use disorder treatment. They also are asked what their educational and occupational interests are while in prison. Those who indicate an interest in college and already have a high school diploma (or equivalent) are identified by CDCR as potential students for postsecondary instruction. (Students may also express interest in college after earning a high school diploma, or the equivalent, while incarcerated.) People at state prisons who are interested in attending community college programs apply using a paper‑based application and enroll based upon course availability.

Enrollment Growth in CCC Courses Was Strong Leading Up to the Pandemic. As Figure 2 shows, CCC enrollment of incarcerated students in state prisons increased from about 1,400 FTE students in 2015‑16 to nearly 5,500 FTE students in 2018‑19—almost quadrupling within just four years. Growth in enrollment among incarcerated students can be attributed in part to two changes in state law that occurred during the 2010s. A 2014 statutory change allowed community colleges to be funded for in‑person instruction at state prisons (discussed more in the “Funding” section of this report). As Figure 2 shows, CCC enrollment growth at state prisons was most substantial starting in 2016‑17 (the first full year of colleges offering in‑person instruction) and the subsequent two years. In addition, beginning in 2014, various policy changes have increased people’s ability to earn time off of their prison sentences—known as “credits”—for participating in education programs. (The box below provides more information about these credits.) Whereas CCC enrollment at state prisons has increased over the past decade, overall enrollment across the CCC system has declined by 15 percent

Sentence‑Reduction Credits for Incarcerated Students

Credit‑Earning Opportunities Have Increased at State Prisons. Beginning in 2014, various policy changes have expanded the ability of people in prison to earn time off their sentences. For example, people can earn credits by participating in rehabilitative programs, such as community college programs. Notably, in 2016, Proposition 57 gave the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) constitutional authority to make changes to credit‑earning opportunities through regulations. CDCR used this authority to expand eligibility for credits and increased the amount of time that people can earn off their sentences through credits.

Incarcerated Students Can Earn Credits to Reduce Their Prison Sentences. Under current regulations, incarcerated students earn a Milestone Completion Credit (MCC) for every college course completed of at least three semester units (or 4 quarter units) with a grade of “D” or better. MCCs earned through a college course provide one week off a person’s sentence, with students able to earn up to three months off their sentences over a 12‑month period. In addition to MCCs, CDCR awards an Educational Merit Credit (EMC) when an incarcerated student earns a particular degree for the first time. Students can receive multiple EMCs. For example, students would earn four EMCs if they earned a high school diploma, an associate degree, a bachelor’s degree, and a master’s degree while in prison. They are not eligible to earn an additional EMC for a second degree at the same level (such as a second associate degree in a different subject). Each EMC reduces a person’s sentence by six months. With the exception of those sentenced to death or life without the possibility of parole, all people in prison are eligible to earn MCCs and EMCs.

Though In‑Person Instruction Has Grown Over Time, Correspondence Courses Remain Most Prevalent. Figure 3 shows that in‑person CCC instruction at CDCR has waxed and waned. In‑person instruction increased gradually—both overall and as a share of total instruction—between 2015‑16 and 2019‑20. At its peak, 48 percent of CCC instruction at prisons was provided in person. With the onset of the pandemic, however, in‑person instruction plummeted and the share of instruction provided via correspondence increased. This is primarily because CDCR suspended most of its in‑person rehabilitation programs, including CCC instruction, to mitigate the spread of COVID‑19. In 2022‑23, however, in‑person instruction recovered back to its 2018‑19 level in terms of FTE student enrollment, though it remained somewhat lower as a share of total enrollment (40 percent). Importantly, the increase of in‑person instruction at the state prisons occurred despite a significant reduction in the overall prison population since the start of the pandemic.

Students Generally Reflect Overall CDCR Prison Population. Figure 4 shows that people incarcerated at CDCR taking CCC coursework are overwhelmingly male, consistent with CDCR’s overall prison population. Blacks and Latinos are somewhat underrepresented as students, while Asians are slightly overrepresented. Students at CDCR tend to be in their 30s and 40s.

Figure 4

People in CDCR Taking CCC Classes

Generally Reflect Overall Prison

Population

|

CCC Students Incarcerated at CDCRa |

Overall CDCR Populationa |

|

|

Gender |

||

|

Male |

94% |

96% |

|

Female |

5 |

4 |

|

Otherb |

1 |

—c |

|

Race/Ethnicity |

||

|

Asian |

3% |

1% |

|

Black |

22 |

28 |

|

Latino |

43 |

46 |

|

White |

20 |

20 |

|

Otherd |

11 |

5 |

|

Age |

||

|

18 to 24 |

4% |

5% |

|

25 to 29 |

14 |

12 |

|

30 to 39 |

36 |

31 |

|

40 to 49 |

27 |

24 |

|

50 or older |

19 |

29 |

|

aData on CCC students incarcerated at CDCR are from 2022‑23, whereas data on the overall CDCR population is a snapshot from December 2023. bFor CCC students incarcerated at CDCR, reflects nonbinary individuals or students with an unreported gender. For CDCR population, reflects nonbinary individuals. cLess than 0.5 percent. dIncludes Native American, Pacific Islander, multi‑ethnic, or unreported. |

||

|

CDCR = California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. |

||

Many Incarcerated Students Have Long Sentences Remaining. Based on information received from CDCR, about 8,500 incarcerated students enrolled in a CCC course in spring 2023. Of those students, over half had more than five years remaining before release, as Figure 5 shows. Those with sentences of five years or longer enroll in CCC courses at higher rates than those with fewer years remaining in their sentences. Moreover, students sentenced to death or life without the possibility of parole represent a slightly higher share of CCC enrollment compared to their share of the overall CDCR prison population.

Figure 5

Over Half of CCC Enrolled Incarcerated Students Will

Not Be Released From CDCR in the Next Five Years

|

CCC Students Incarcerated at CDCRa |

Overall CDCR Populationa |

|

|

Sentence Remaining: |

||

|

Five years or less |

45% |

66% |

|

More than five years |

55 |

34 |

|

Life Without the Possibility of Parole and Death Penalty Sentences |

8 |

6 |

|

aData on CCC students incarcerated at CDCR are from the spring 2023 term, whereas the data on the overall CDCR population is a snapshot from October 31, 2023. |

||

|

CDCR = California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. |

||

Some Students Already Have Earned Many CCC Units and a College Degree. To earn an associate degree, students generally need to complete 60 units of coursework. While most incarcerated students at CDCR taking CCC coursework have accumulated fewer than 60 units, some students have accumulated notably more units. Specifically, in 2022‑23, 1,808 CCC students at CDCR (12 percent) had earned more than 60 units. Of these students, 418 (2.7 percent) had already earned 100 or more CCC units. Just over 100 of these students had already accumulated 150 or more units. Furthermore, of the 15,500 incarcerated CCC students enrolled in 2022‑23, 905 (5.8 percent) already had earned an associate degree in a prior year.

Student Outcomes

Course Success Rates Are Similar to Other CCC Students… The Chancellor’s Office currently does not provide public‑facing data on any outcomes related to CCC students at state prisons. Data requested by our office and provided by the Chancellor’s Office, however, indicate incarcerated CDCR students in CCC programs have course success rates (earning a passing grade or course credit) similar to those of other CCC students (72 percent on average).

…Though Incarcerated Students Do Worse in Correspondence Courses. Course success rates vary by instructional modality among incarcerated students. Figure 6 shows that success rates are consistently lower for students in correspondence courses. In fall 2019 (the year just before the pandemic), the gap in success rates between in‑person and correspondence courses was 15 percentage points. The gap shrunk temporarily during the pandemic as success rates for in‑person courses declined as a result of disruptions to in‑person programming.

Persistence Rates Are Lower for Incarcerated Students. Based upon our request, the Chancellor’s Office also provided data on the share of incarcerated students that continued their studies (either at CDCR; another correctional facility, such as a county jail; or in the community, if released). In higher education, these data are commonly referred to as student persistence rates. Figure 7 shows persistence rates for several cohorts that started their CCC education at CDCR. On average, incarcerated students have notably lower persistence rates compared with the average for CCC students.

Degree Earners Tend to Take a Long Time to Graduate. Community colleges typically report graduation rates by cohort over a three‑year or four‑year period. For incarcerated students, the graduation rate over these periods is very low—less than 5 percent. This is significantly lower than graduation rates for other CCC students (with an overall three‑year graduation rate approaching 20 percent). In 2022‑23, a total of 731 students at CDCR earned their first associate degree. The average time to degree for these students was about nine years.

Funding

In this section, we explain how community college programs, including those offered at state prisons, are funded.

Proposition 98 Is Colleges’ Main Source of Funding. Proposition 98 (1988) sets aside a minimum amount of funding for schools and community colleges based upon a set of constitutional formulas. Proposition 98 funding comes from the state General Fund and certain local property tax revenues. Most Proposition 98 funding is provided to community colleges through “apportionments,” which is general‑purpose funding used to pay for instruction and other core operating costs. The state also provides Proposition 98 funding through categorical programs. Categorical funding is restricted for specified purposes, such as targeted academic support for low‑income students, financial aid administration, and regional workforce development activities.

2014 Legislation Permits CCC to Receive State Funding for In‑Person Instruction at State Prisons. Statute generally requires CCC courses to be open to the public to be eligible for state apportionments funding. Historically, these provisions have allowed individuals incarcerated at state prisons to access only correspondence courses, which are also available to members of the general public. In 2014, the state approved Chapter 695 (SB 1391, Hancock), which opened the way for districts to provide in‑person instruction at state prisons by allowing them to receive regular state funding for closed‑to‑the‑public courses offered to incarcerated people. Correspondence and in‑person courses at the state prisons are funded at the same per‑student rate, as is the case for CCC courses provided to the general public. CCC courses at the state prisons are funded based entirely on how many FTE students are enrolled.

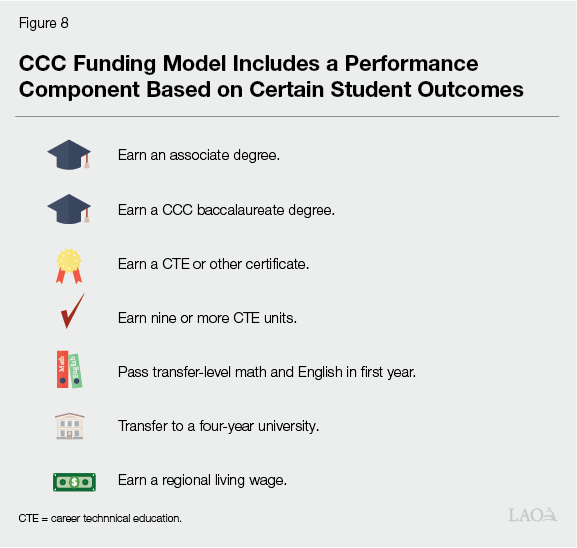

State Modified Funding Model for Most CCC Instruction. In 2018‑19, the state adopted a new apportionments funding model for community colleges, which placed more emphasis on students achieving positive outcomes and somewhat less emphasis on enrollment. The new formula has three main components. The components are: (1) a base allocation linked to enrollment (about 70 percent of formula funding), (2) a supplemental allocation linked to low‑income student counts (about 20 percent of formula funding), and (3) a student success allocation linked to specified student outcomes (about 10 percent of formula funding). Figure 8 lists the student outcomes the state uses for the student success allocation. For each of the three components of the formula, the state set new associated funding rates. Within the student success component, the state sets specific funding rates for each measured student outcome.

Model Left Unchanged How Colleges Are Funded for Incarcerated Students. The new funding model—known as the Student Centered Funding Formula (SCFF)—did not change how the state funds incarcerated students. Instead, funding for these students remains based entirely on enrollment, without any student success component. The funding rate for incarcerated students ($7,345 in 2023‑24) is similar to the average overall per‑student rate for CCC instruction under SCFF. In 2022‑23, the state provided districts a total of $37 million Proposition 98 General Fund for apportionments generated on behalf of CCC students incarcerated at state prisons.

Incarcerated Students Typically Do Not Pay CCC Enrollment Fee. Statute sets an enrollment fee of $46 per credit unit. The state, however, waives this fee for low‑income students. Students apply for a waiver by completing a CCC application (known as the “Community College Promise Grant Application”) or a federal application (known as the “Free Application for Federal Student Aid” or FAFSA). Given that the vast majority of incarcerated people have little to no income, very few CCC students within CDCR pay enrollment fees. Instead, community college staff process incarcerated students’ Promise Grant applications (providing assistance with completing the form, if needed), and the state covers the cost of the foregone revenues with Proposition 98 General Fund. While incarcerated students are eligible for a CCC enrollment fee waiver, they are not eligible for other state grants, such as Cal Grants or Middle Class Scholarships.

State Also Funds Two CCC Categorical Programs Supporting Incarcerated Students. Since 2021‑22, the state has provided $10 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund for the Rising Scholars Network. Currently, 80 community colleges—including all 25 colleges providing instruction to students at CDCR—receive a grant from this program. (The state also provides $15 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund for students in county juvenile correctional facilities for similar purposes.) Colleges typically use their grant funds to support a coordinator position as well as other purposes, such as professional development for faculty teaching incarcerated students. In addition, since 2016‑17, the state has provided $3 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund to colleges to pay textbook costs for incarcerated students at CDCR. (Beginning in 2023‑24, colleges may use these funds to cover textbook costs in other correctional settings too, including county jails and federal prisons located in the state.)

CDCR Is Funded to Provide Technology for Incarcerated Students. CDCR’s budget includes non‑Proposition 98 General Fund to cover technology and technology support for rehabilitation programs, including community college and other postsecondary courses. CDCR employs technology support staff primarily to (1) manage and maintain the technology infrastructure at state prisons or (2) serve as liaisons between the colleges and students. In these roles, technology support staff help coordinate and troubleshoot technology‑related issues throughout the prisons. Technology used by students in postsecondary education include:

- Computers. The 2021‑22 state budget provided $18 million ongoing funding and an additional $5 million one‑time funding to distribute 37,000 laptops at state prisons by 2024. Laptops are to be distributed in phases across all prisons, with every student participating in postsecondary education each term eligible for a computer, along with people participating in other rehabilitative programming. Students use the laptops to read, write, and submit assignments and can access them throughout the prison, including in the housing units. Students can also use desktop computers in some classrooms for similar purposes (whenever access is granted to that room).

- Division of Rehabilitative Programs Television (DRP‑TV). The state provided $3.5 million one‑time funding for equipment in 2016‑17 and provides about $400,000 ongoing funding for DRP‑TV, which is a closed‑circuit platform that delivers 24/7 televised programming content. DRP‑TV stations are available at all prisons and located throughout the prisons, including in most classrooms. DRP‑TV’s education channel televises college course content for students who are enrolled in correspondence classes.

- Internet and Wi‑Fi Connectivity. The state provides $5 million ongoing funding for students to have access to Wi‑Fi in common areas of a prison, such as day rooms, dining halls, gyms, libraries, and classrooms. Incarcerated students connect to the internet for various reasons, including completing research assignments, submitting coursework, or accessing academic support. Due to CDCR security restrictions, prisons only allow students to access websites that have been vetted and approved by the department.

- Digital Library Subscription. The state provides $500,000 ongoing funding for digital library subscriptions for incarcerated students at all CDCR prisons. Students have access to research databases, e‑journals, magazine subscriptions, peer‑reviewed articles, and e‑books that can be used to complete course assignments.

New Federal Policy Resumes Pell Grants for Eligible Incarcerated Students. Prior to 1994, eligible incarcerated students could receive a federal Pell Grant for their postsecondary studies. The funds were intended to cover tuition and other costs of attendance. In 1994, Congress passed legislation ending this policy. Recently, however, the federal government re‑instated Pell Grants for eligible incarcerated students (those that have a valid social security number, are a U.S. citizen or eligible noncitizen, and maintain satisfactory academic progress, among other requirements). Effective July 2023, incarcerated students may apply for a Pell Grant using the FAFSA. The maximum Pell Grant award is about $7,400 in 2023‑24, with the specific amount students are entitled to receive varying based on income level, cost of attendance, and status as full‑time or part‑time student. Students may receive a Pell Grant for up to six years of full‑time enrollment or the equivalent, with part‑time students eligible to receive prorated awards over a longer period. (For example, a student enrolled half time could receive about $3,700 annually for up to 12 years.) Incarcerated students may use Pell Grants to cover tuition, textbooks and other course materials, supplies and equipment (such as to buy or rent a personal computer), and costs to obtain a certification or other first professional credential. The federal government does not allow Pell Grants to be used for costs to house incarcerated students.

Assessment

In this section, we provide our assessment of community college education at state prisons. Overall, we found that these education programs have several positive aspects but also a number of problems and missed opportunities.

Anecdotally, Both Students and Staff Cite Benefits of Prison Education. In fall 2023, we visited several prisons (both men’s and women’s). We met with students, faculty, and staff. During these visits, students shared their challenges, such as having instruction disrupted by prison security incidences that required them to return to their cells and encountering technology glitches (such as having difficulty finding areas of the prison with a strong enough Wi‑Fi signal for their laptops). Despite these types of challenges, students commented that postsecondary education had offered them a number of notable personal benefits, including changing their image of themselves in a positive way, building confidence, developing critical thinking skills, and improving their prospects once they exit prison. Several students also mentioned that postsecondary education had helped them enhance communication with their families. Even those confined to life sentences shared that a CCC education had been beneficial in various ways, including by allowing them to serve as mentors to younger incarcerated persons and inspiring family members on the outside to go to college. Community college faculty we interviewed indicated that students tended to be motivated and generally came prepared for class. CDCR staff, including administrators and correctional officers, generally believe that prison education has created a better atmosphere in prison and made incarcerated students more productive with their time. Some research conducted at other correctional settings has identified similar benefits of postsecondary education during incarceration. (CDCR has not conducted a rigorous evaluation of the impacts of its postsecondary education programs.)

Course Offerings Are Insufficient to Meet Strong Enrollment Demand. Though neither CDCR nor CCC centrally report the data, based on discussions with CDCR and CCC administrators and our visits to prisons, incarcerated students’ demand for postsecondary courses exceeds the quantity of available courses. As a result of the high demand for these courses, some people can wait up to three years to take their first postsecondary CCC course while in prison. Community colleges and CDCR generally report a much greater ability to accommodate demand for correspondence courses, with typically much less wait time. (Later in this section, we identify the main limitations to expanding in‑person CCC course offerings.)

Some Colleges’ Enrollment Priorities Have Drawbacks. Because demand for a CCC education generally outstrips the number of in‑person slots, colleges must decide which incarcerated people have enrollment priority. Enrollment priority is determined by each college. We found that enrollment prioritization varies across prisons. Some colleges open up registration on a first‑come, first‑served basis. A first‑come, first‑served approach does not take into account whether a student already has a degree or has many years remaining on a sentence. Under this approach, students close to release who do not yet have a degree could be crowded out by students who already have a degree and/or have a significant amount of time left on their sentences. Other colleges avoid these drawbacks by giving enrollment priority to students closest to release and continuing students who are closest to finishing their first associate degree. Such an approach likely increases the number of people who have at least one degree when they are released from prison, which in turn can help reduce recidivism and improve employment opportunities.

Key Barriers to Expanding In‑Person Enrollment. Recognizing the relatively poor course success rates of correspondence‑based education, statute directs CDCR to focus on in‑person postsecondary instruction. Yet, some key issues prevent prisons from expanding in‑person CCC instruction, including:

- Prison Space Constraints. Most prisons have a limited number of classrooms, which hampers CDCR’s and CCC’s ability to offer additional in‑person courses. A lack of data, however, precludes the Legislature from determining if existing CDCR space is being used efficiently and if additional classroom space is warranted. In particular, CDCR lacks a comprehensive assessment of its utilization of classroom space by prison.

- Faculty Recruitment Challenges. Community college administrators indicate that finding enough faculty to teach inside state prisons tends to be difficult. Some faculty do not feel comfortable or do not want to work inside a prison. In addition, many prisons are in rural areas of the state with relatively small pools of individuals who are qualified to teach postsecondary courses. In particular, college administrators indicate they would offer more STEM courses but are limited due to lack of available faculty to teach those subjects. We did not hear the same level of challenges from colleges that provide instruction via correspondence education.

Several Colleges Are Piloting Online Models That Appear Promising. With the recent distribution of laptops to students, community colleges and CDCR have an opportunity to rethink how instruction is delivered to students from a distance. This year, several community colleges that are large providers of correspondence courses are piloting a form of online instruction in place of the traditional paper‑and‑mail model. For example, Lake Tahoe Community College is piloting an online synchronous (live) format in which students and faculty can communicate through videoconferencing and submit assignments online. For security purposes, each course section is being limited to students from the same section of a prison. Other colleges, such as Coastline College and Feather River College, are piloting online models using asynchronous instruction, in which students and faculty have the ability to communicate with and leave messages for each other electronically. Relative to traditional correspondence courses, these online pilots have the potential to provide more efficient and effective ways for students to complete their courses and receive feedback. Having access to a laptop also opens up greater opportunities for students to receive support from counselors and tutors in a more direct and timely way, which could improve student success.

CCC Funding Model Lacks Fiscal Incentive to Promote Success for These Students. Unlike CCC funding for most other student groups, CCC funding for incarcerated students is not linked to performance. Instead, the associated apportionments funding depends only on enrollment. Without performance‑based funding or some other form of state accountability for student outcomes, colleges lack strong incentives to improve their results. Moreover, given colleges only generate funding through instructional time, support services that might lead to better student outcomes likely are not being prioritized. While community colleges do not collect or report the number of services provided, based on our visits to prisons and our related meetings, relatively few counselors are provided to advise students, with some counselors having a caseload of more than 1,000 incarcerated students. As a result, students tend to have infrequent counseling sessions. Furthermore, incarcerated students typically do not have access to trained tutors, as students have in other community college settings.

State Is Missing Opportunity to Use Federal Funds for College Education at Prisons. Though the federal government is now offering Pell Grants to eligible incarcerated students, California is receiving no associated benefit from the policy change. This is because incarcerated CCC students generally have no reported costs of attendance. Instead, the state (through both CCC’s and CDCR’s budgets) covers their fees, textbooks, and other education costs. Were the state to begin charging incarcerated CCC students enrollment fees and certain other education expenses (such as laptops), the federal government would fully cover these costs. The state, in turn, would free up both Proposition 98 and non‑Proposition 98 General Fund that could be used for other purposes, including other education purposes.

CCC Education Programs at Prisons Lack an Evaluation Component. National research indicates that when postsecondary education is well designed and implemented effectively in correctional settings, it can reduce the rate of reoffending, along with increasing employment rates and wages when incarcerated students are released. Additionally, it can result in correctional savings that more than offset program costs. Although the partnership between CCC and CDCR has expanded community college enrollment at state prisons, there is not an existing evaluation component that analyzes the specific impact of a CCC education on recidivism, employment rates, and wages. Because of this lack of evaluation, it is not clear whether the CCC programs are producing the desired results.

Recommendations

Legislature Could Improve Policies in Several Ways. In this section, we make several recommendations aimed at addressing the problems and missed opportunities we have identified with CCC education at state prisons. Our recommendations, shown in Figure 9, are focused on enrollment prioritization, space utilization, instructional modality, funding, and oversight. From a technical perspective, most of the recommendations we make could be adopted and implemented immediately. Developing new space and utilization standards, however, could take more time. In addition, the Legislature likely would want to phase in any funding formula changes to ensure colleges have time to adjust their practices in response to the new fiscal incentives. Overall, our recommendations would result in modest Proposition 98 General Fund and non‑Proposition 98 General Fund savings, as discussed more at the end of this section.

Figure 9

Summary of Assessment and Recommendations for CCC Programs at State Prisons

|

Component |

Assessment |

Recommendation |

|

Enrollment prioritization |

Demand for CCC courses among incarcerated people generally exceeds supply, yet some colleges do not give enrollment priority to those people most likely to benefit. |

Adopt statutory enrollment priorities that apply at all state prisons. Give priority to students who are closest to obtaining their first degree and within five years of release. This approach could improve individuals’ post‑release outcomes, including by reducing the risk of recidivism and improving job prospects. |

|

Space utilization |

CDCR and CCC report a lack of sufficient space to hold in‑person courses, yet CDCR lacks a comprehensive assessment of its space utilization. |

Adopt statutory space and utilization standards. Direct CDCR to collect data and report biennially on space utilization. |

|

Online pilots |

Given the generally poor outcomes of correspondence courses, some community colleges and CDCR are working together to pilot new online instructional models. |

Require CCC and CDCR to report on pilot outcomes, including course success rates compared with in‑person and correspondence courses and impact on faculty recruitment to teach high‑demand courses in prisons. |

|

State funding |

State’s current CCC funding model lacks a strong incentive for colleges to promote incarcerated student success. |

Modify CCC funding formula to include a performance component. In the meantime, require CCC to report enrollment and outcomes data for incarcerated students. |

|

Federal funding |

State is missing an opportunity to draw down federal funds to support prison education costs. |

Begin charging incarcerated students to attend CCC and use federal Pell Grant funds to offset enrollment fees, textbooks, computers, and other allowable education costs. |

|

Program evaluation |

The state lacks an evaluation analyzing the impact of CCC education programs on recidivism, employment, and wages. |

Require CDCR to annually report data on recidivism, employment, and wage outcomes by educational program, provider, and risk level of reoffending. In addition, require CDCR to use external evaluators to assess the impact of CCC programs every five to ten years. |

|

CDCR = California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. |

||

Provide Statutory Guidance on Enrollment Prioritization Among Incarcerated Students. Given the different enrollment prioritization approaches that colleges are using to place individuals at state prisons into CCC courses and the notable drawbacks of the first‑come, first‑served approach, we recommend the Legislature adopt a set of statutory enrollment priorities for CCC students that would apply at all state prisons. We envision an approach that assigns priority for courses to new students who have less than five years left on their sentences and continuing students making good progress toward their first degree. Under our recommended approach, more individuals are likely to be released from state prison with an associate degree, which in turn could reduce their risk of recidivism and improve their job prospects.

Require CDCR to Collect and Report on Space Usage. To determine whether additional classroom space is warranted within state prisons, the state needs to know: (1) how much rehabilitation space is already available within prisons, (2) the extent to which that space is being used, and (3) how big of a space deficit or surplus exists at each prison and systemwide. Accordingly, we recommend the Legislature require CDCR to collect and report on its space utilization biennially, similar to how the three segments of higher education report utilization of their instructional facilities. In tandem, we recommend the Legislature adopt statutory space and utilization standards for rehabilitation spaces within prisons (as the Legislature has done for the three segments of higher education). Space standards would establish the amount of space (assignable square feet) that should be available on a per‑student basis for classroom purposes as well as other rehabilitation purposes, if space is being used for multiple types of rehabilitation programs. Utilization standards would establish the amount of time that rooms and “stations” (such as a desk or computer terminal) should be used. Having these standards and utilization reports would not only help guide decisions about the amount of classroom space needed but would also help assess the need for other rehabilitation space at a systemwide level and at particular prisons.

Require CCC and CDCR to Report on Online Education Pilots. Online education has the potential to alleviate a number of challenges for prison education. Online education, for example, could help address a potential lack of classroom space within prisons; limited in‑person faculty availability, particularly in STEM disciplines; and instructional disruptions related to prison security incidences and other circumstances generally unique to the correctional setting. Given that several community colleges are implementing online pilots with their CDCR prison partners, we recommend the Legislature request periodic updates on the outcomes of those pilots. The Legislature could request that CCC and CDCR report data on student outcomes (such as course success rates) in the pilots compared with similar courses offered via correspondence or in person. CCC and CDCR also could be tasked with reporting any security‑related concerns with the instructional model being piloted, whether the model creates a better‑quality teaching and learning experience compared with traditional correspondence education, and whether the model allows for community colleges to offer STEM or other high‑demand programs currently not offered. The Legislature could require such an update through an interim legislative report within two years and a final report within five years. To the extent the pilots yield better outcomes, CCC and CDCR could begin changing their programs accordingly.

Add Performance Component to Funding Formula Used for Incarcerated Students. We recommend the Legislature replace the existing CCC funding model for incarcerated students, which is based entirely on enrollment, with a model that builds in a performance component. Adding a performance component would create stronger incentive for colleges to focus on incarcerated student outcomes and provide robust support services. The Legislature could use the same three‑component model and funding rates currently in place for most other CCC students. (Since incarcerated students generally are low income, the vast majority of districts would receive the supplemental allocation.) We recommend the Legislature generally use the same student success metrics currently in place for most other CCC students. (The Legislature might exclude one outcome measure—earning a living wage—as it is not applicable to still‑incarcerated students.) The new funding model could be implemented such that it costs no more or less in total compared to the existing way the state funds incarcerated students. To provide time for community colleges to adjust to the new funding model, the state could commence funding adjustments one year after statutory adoption. It then could phase in funding changes over three years—gradually increasing the share of funding that is performance based until it reaches 10 percent of apportionments funding.

Until New Funding Model for Incarcerated Students Is in Place, Require CCC to Report Enrollment and Outcomes Data. Once a new apportionments funding formula is operative, the state and public will have regular access to enrollment and outcomes data on CCC students at state prisons, as this data is needed to determine funding allocations for each district. Until a new formula is operative, we recommend the Legislature require the Chancellor’s Office to report certain data by October 1 each year on the incarcerated students whom community colleges serve. Specifically, we recommend the Chancellor’s Office be required to report: the number of incarcerated FTE students served, broken out by instructional modality; course success rates, also broken out by instructional modality; term‑to‑term persistence rates; share of first‑year cohorts that pass college‑level math and English; and program completion rates (such as earning an associate degree or certificate). Such reporting would allow the Legislature to better exercise its oversight role in the near term.

To Leverage Federal Funding, Charge Enrollment Fees and Education‑Related Fees. We recommend charging incarcerated students the statutory enrollment fee ($46 per unit). Similarly, we recommended charging incarcerated students for their textbooks. In both cases, federal Pell Grants would reimburse colleges for these costs, with students paying nothing out of pocket. Together, these two recommendations would free up a combined approximately $9 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund. We further recommend directing CDCR to charge Pell Grant‑eligible students a computer equipment fee and other allowable technology fees, as Pell Grants also would cover these costs. We estimate this recommendation would reduce ongoing non‑Proposition 98 General Fund costs in CDCR’s budget by the low tens of millions of dollars. (Due to federal rules, prisons would need to coordinate with their CCC partners so the colleges charge Pell Grant‑eligible students the fee for the laptop rentals and other expenses. The college would then pass through the federal funding to the prison to cover these costs.) Given students need to complete a FAFSA to obtain a Pell Grant (which typically is due by March each year), the state could make these new fee policies operative commencing in 2025‑26. CCC staff would be responsible for assisting incarcerated students with completing the FAFSA, similar to the FAFSA support CCC staff already provide to other CCC students. Because Pell Grants are not available to certain individuals (such as undocumented immigrants), the state could continue to cover associated fees for those students.

Require CDCR to Evaluate CCC Education Programs. To help assess the effectiveness of CCC courses at state prisons, we recommend that the Legislature require CDCR to work with each of its education partners to track and report certain data. Specifically, we recommend CDCR track and report recidivism rates, employment rates, and wages by educational program and provider. We recommend CDCR report the results by the risk level of reoffending of the incarcerated students. All of this information could be reported in the existing recidivism reports CDCR conducts annually—typically released in the spring. In addition, we recommend that the education programs in state prisons be evaluated every five to ten years by external researchers to determine how effective postsecondary programs are and which degree programs are most effective at achieving positive outcomes. We note that CDCR has previously contracted with external researchers to assess the effectiveness of its services and programs.

New Administrative Workload Likely Comes With Little Added Cost. Taken together, these recommendations would place some new administrative requirements on CCC and CDCR. Both agencies, however, likely could accommodate the minor additional workload and minor associated costs within their existing budgets. This is because both agencies already need to collect much of the specified data for other purposes. For example, CDCR already knows which prison spaces it uses for rehabilitative purposes and how much time is scheduled for each rehabilitative program in that space. Moreover, both agencies already have some incentives to track the specified data and undertake the specified studies. For example, with more reliable space and utilization data, CDCR would be able to demonstrate more clearly when additional rehabilitation space (such as classroom space) is warranted. (As further context, the state does not provide the higher education segments with specific funding earmarks to complete their data collection requirements and facility utilization studies.) Given that the results of the recommended data and studies have the potential to notably improve legislative decision‑making on prison postsecondary education policy and programs moving forward, we believe the added administrative workload is warranted.