Ann Hollingshead

November 20, 2024

The 2025‑26 Budget

California’s Fiscal Outlook

- Introduction

- Revenues Run Ahead of Broader Economy

- 2025‑26 Budget Roughly Balanced

- No Capacity for New Commitments

- Appendix

Executive Summary

The Fiscal Outlook gives the Legislature our independent estimates and analysis of the state’s budget condition for the 2025‑26 budget process. We evaluate the budget condition based on current law and policy at both the state and federal level. This means we are assessing the state’s spending and revenues assuming no new laws or policies are enacted. This is not a prediction of what will happen—state and federal laws and policies will change in the coming years—but rather serves as a baseline to help the Legislature understand its starting place. Further, while changes in federal policy are being actively discussed, we cannot predict which changes may be enacted and therefore cannot estimate the effects on California’s budget.

Legislative Action Last Year Addressed Anticipated Budget Problem Proactively. In the 2024‑25 budget process, the Legislature not only addressed the budget problem for that fiscal year, but also made proactive decisions to address the anticipated budget problem for 2025‑26. These choices included about $11 billion in spending‑related solutions and $15 billion in all other solutions, including $5.5 billion in temporary revenue increases and a $7 billion withdrawal from the state’s rainy‑day fund. After these solutions, the spending plan assumed the 2025‑26 budget would be balanced.

Revenues Running Ahead of Broader Economy. Despite softness in the state’s labor market and consumer spending, earnings of high‑income Californians have surged in recent months. Income tax collections have seen a similar bounce. This recovery in income tax revenues is being driven by the recent stock market rally, which calls into question its sustainability in the absence of improvements to the state’s broader economy.

Revenue Improvement Offset by Higher Costs, 2025‑26 Budget Remains Roughly Balanced. Although revenues are running ahead of budget act assumptions, those improvements are roughly offset by spending increases across the budget. On net, our assessment finds the state has a small deficit of $2 billion. Given the size and unpredictability of the state budget, we view this to mean the budget is roughly balanced. If a budget problem of this magnitude were to materialize by the end of the budget process in June, relatively minor budget solutions would be needed.

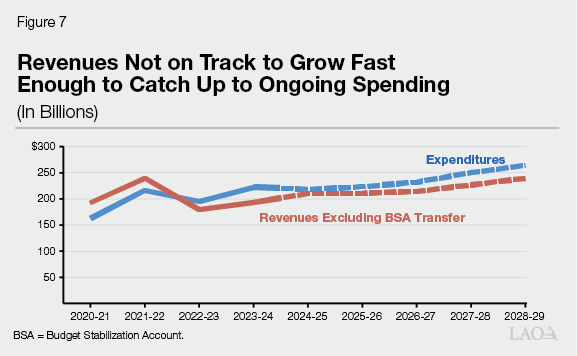

Revenues Are Unlikely to Grow Fast Enough to Catch Up to Atypically High Spending Growth. While the budget picture is fair for the upcoming year, our outlook suggests that the state faces double‑digit operating deficits in the years to come. By historical standards, spending growth in this year’s outlook is high. Our estimate of annual, total spending growth across the forecast period—from 2025‑26 to 2028‑29—is 5.8 percent compared to an average of 3.5 percent in other recent outlooks. Meanwhile, revenue growth over the outlook window is just above 4 percent—lower than its historical average largely due to policy choices that end during the forecast window. Taken together, we view it as unlikely that revenue growth will be fast enough to catch up to ongoing spending.

No Capacity for New Commitments. While out‑year estimates are highly uncertain, we anticipate the Legislature likely will need to address deficits in the future, for example by reducing spending or increasing taxes. In our view, this year’s budget does not have capacity for new commitments, particularly ones that are ongoing.

Introduction

Every year, our office publishes the Fiscal Outlook in anticipation of the upcoming budget season. This report gives the Legislature our independent estimates and analysis of the state’s budget condition with the goal of helping lawmakers prepare for the 2025‑26 budget process. As always, our Fiscal Outlook evaluates the budget’s condition based on current law and policy at both the state and federal level. This means we are assessing the state’s spending and revenues assuming no new laws or policies are enacted. This is not a prediction of what will happen—state and federal laws and policies will change in the coming years—but rather serves as a baseline to help the Legislature understand its starting place. Further, while changes in federal policy are being actively discussed, we cannot predict which changes may be enacted and therefore cannot estimate the effects on California’s budget.

This year, our report has three takeaways:

- Revenues Running Ahead of Broader Economy. Despite softness in the state’s labor market and consumer spending, earnings of high‑income Californians have surged in recent months. Income tax collections have seen a similar bounce. This recovery in income tax revenues is being driven by the recent stock market rally, which calls into question its sustainability in the absence of improvements to the state’s broader economy.

- 2025‑26 Budget Roughly Balanced. In the 2024‑25 budget process, the Legislature not only addressed the budget problem for that fiscal year, but also made proactive decisions to address the anticipated budget problem for 2025‑26. Although revenues are running ahead of budget act assumptions, those improvements are roughly offset by spending increases across the budget. This means the budget is roughly balanced this year.

- No Capacity for New Commitments. While the budget picture is fair for the upcoming year, our outlook suggests that the state faces double‑digit operating deficits in the years to come. While these out‑year estimates are highly uncertain, this is an indication that the Legislature might need to address deficits in the future, for example, by reducing spending or increasing taxes. In our view, this year’s budget does not have capacity for new commitments, particularly ones that are ongoing.

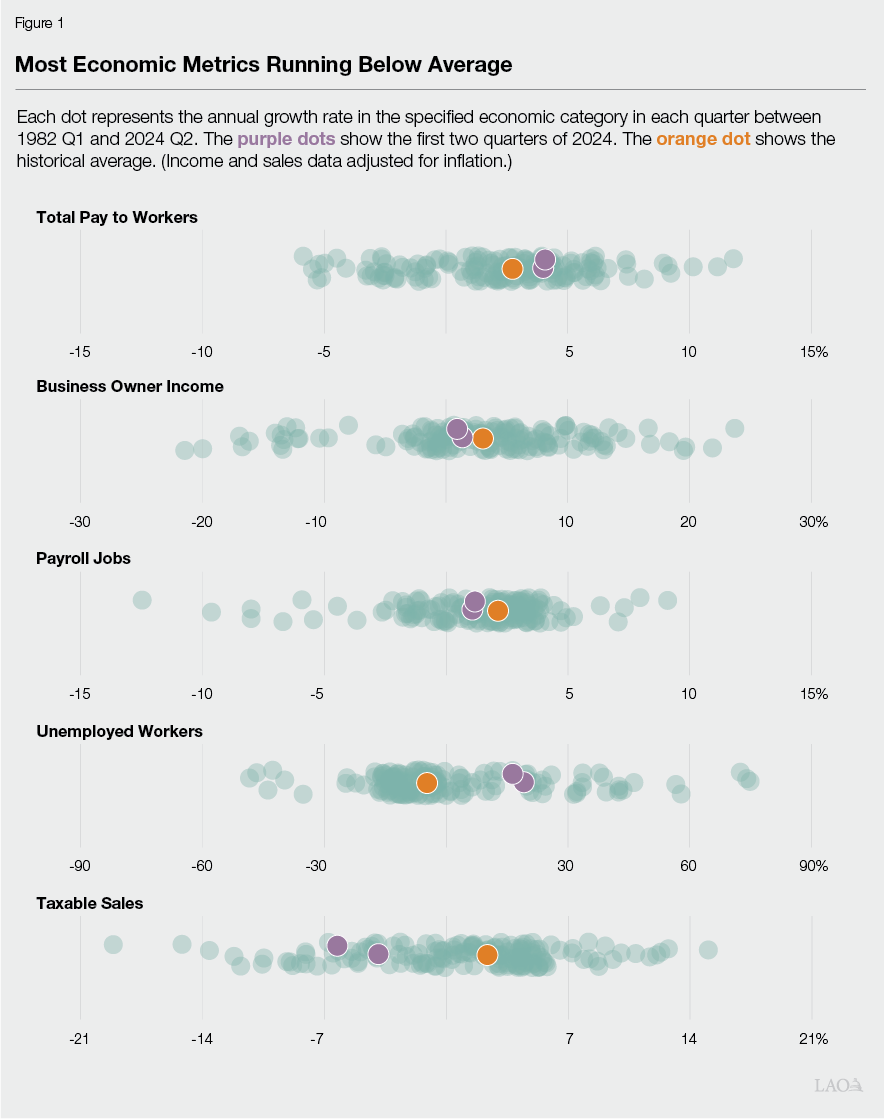

Revenues Run Ahead of Broader Economy

State’s Job Market and Consumer Spending Remain Lackluster… California’s economy has been in an extended slowdown for the better part of two years, characterized by a soft labor market and weak consumer spending. While this slowdown has been gradual and the severity milder than a recession, a look at recent economic data—as in Figure 1—paints a picture of a sluggish economy. Outside of government and health care, the state has added no jobs in a year and a half. Similarly, the number of Californians who are unemployed is 25 percent higher than during the strong labor markets of 2019 and 2022. Consumer spending (measured by inflation‑adjusted retail sales and taxable sales) has continued to decline throughout 2024.

…And Yet Incomes Are Growing Rapidly for High‑Income Californians. Alongside these downbeat trends, a bright spot has emerged: strong growth in total pay to California workers. Total pay grew at a well above‑average rate in the first half of 2024. The first quarter was especially strong, with 17 percent annualized growth in total pay, among the sharpest quarterly growth rates on record. Income tax receipts have followed suit, with withholding collections nearing 10 percent growth so far this year. Yet this pay bounce does not appear to be connected to the hourly wages and salaries that most workers receive. Estimates suggest pay from these traditional forms grew at an annualized rate of only a few percentage points in the first quarter. Instead, much of the bounce appears to be tied to special forms of pay for high‑income workers, such as bonuses and stock compensation.

Booming Stock Market Driving Income Growth. The recent run‑up in the stock market, which appears tied to optimism surrounding artificial intelligence, is a primary driver of the rapid growth in pay to high‑income workers. Stock compensation has become an increasingly important form of pay among California’s high‑income workers, especially those at major technology companies. In the first half of 2024, stock pay alone at four major technology companies accounted for almost 10 percent of the state’s total income tax withholding. Because this form of compensation is tied to the company’s stock price, it rises when stock prices rise. Other forms of pay, such as bonuses to workers in the financial sector, also tend to rise when financial markets are doing well. Early evidence suggests this has been the case in 2024 as well.

Without Broader Economic Improvements, Recent Gains Are on Shaky Ground. With a boost from the booming stock market, our forecast puts tax collections on track to beat expectations by $7 billion over the budget window (that is, from 2023‑24 through 2025‑26). This is entirely due to improving income tax collections, which would, under our forecast, end the current year 20 percent higher than two years ago. That being said, the ultimate outcome is highly uncertain. It is entirely plausible for revenues to end up above or below our estimates by $30 billion across the budget window. Contributing to the uncertainty this year is the fact that a recovery built on a stock market rally is especially precarious. We cannot predict with any confidence what the stock market will do next. Still, some cautionary observations are warranted. Current stock prices relative to companies’ past earnings (a common measure of how “expensive” stocks are) are at levels rivaled only by the transitory booms of 1999 and 2021. Furthermore, a single company (Nvidia) accounts for about one‑third of the total gains in the S&P 500 stock index over the last year. Overall, without more positive signs from the broader California economy, it is difficult to be highly confident in the recent revenue recovery.

Possible Paths to a Broader Economic Recovery. Over the coming months, if California’s labor market and consumers begin to show signs of a broadening recovery, the state’s fiscal position is likely to be on better footing. It remains to be seen whether this will occur, but there are some conceivable paths toward broader improvements. One path is falling interest rates and expansion of money available for lending and investment. A key driver of California’s economic slump over the last two years has been the Federal Reserve’s efforts to tamp down inflation by raising interest rates and shrinking how much money is available for lending and investment. As inflation has eased, the Federal Reserve recently has reversed course. Should inflation remain subdued and the Federal Reserve continue down its path toward looser money, California’s economy could be lifted. Another potential path is continued strength in the stock market. Should enthusiasm around artificial intelligence prove warranted, stocks could solidify around current high levels. The solidification of this new wealth could encourage Californians to consume more and businesses to hire more workers.

2025‑26 Budget Roughly Balanced

Legislative Action Last Year Addressed Anticipated Budget Problem Proactively. In the 2024‑25 budget process, the Legislature not only addressed the budget problem for that fiscal year, but also made proactive decisions to address the anticipated budget problem for 2025‑26. These choices included about $11 billion in spending‑related solutions and $15 billion in all other solutions, including $5.5 billion in temporary revenue increases and a $7 billion withdrawal from the state’s rainy‑day fund, the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA). After these solutions, the spending plan assumed the 2025‑26 budget would be balanced.

We estimate the 2025‑26 budget remains roughly balanced this year. On a technical basis, the budget bottom line condition is the accumulated change in General Fund revenues and spending across the three fiscal years in the budget window—this year, 2023‑24 through 2025‑26—and reflected in the ending balance in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU) in 2025‑26 in Figure 2. On net, our assessment of the budget condition finds the state would have a small deficit of $2 billion. Given the size and unpredictability of the state budget, we view this to mean the budget is roughly balanced. If a budget problem of this magnitude were to materialize by the end of the budget process in June, relatively minor budget solutions would be needed.

Figure 2

General Fund Condition Under Fiscal Outlook

(In Millions)

|

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$47,119 |

$15,875 |

$13,881 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

191,536 |

215,951 |

217,970 |

|

Expenditures |

222,781 |

217,944 |

223,303 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$15,875 |

$13,881 |

$8,549 |

|

Encumbrances |

$10,569 |

$10,569 |

$10,569 |

|

SFEU balance |

$5,306 |

$3,312 |

‑$2,020 |

|

Reserves |

|||

|

BSA balance |

$22,796 |

$17,870 |

$10,770 |

|

Safety Net Reserve |

900 |

— |

— |

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties. |

|||

Higher Revenues Offset by Higher Costs. Our assessment reflects some key assumptions, which we describe in the box below. At a higher level, there are a few factors, some offsetting, that result in the roughly balanced budget. These are shown in Figure 3 and include:

- Small End Balance for 2025‑26. The starting place for this year’s budget is the planned spending and revenue level established by last year’s budget package. In this case, the June 2024 budget package planned for a small balance in the SFEU—$1.5 billion—for the end of 2025‑26.

- Revenues Exceed Budget Act Projections by $7 Billion. Collections data to date show stronger‑than‑anticipated revenue growth across 2023‑24 and 2024‑25, although our forecast for 2025‑26 is mostly flat. Overall, our revenue projections are up by about $7 billion relative to the June 2024 estimates with more than half of that total attributable to the current year.

- Spending on Schools and Community Colleges Higher by $2.5 Billion. Proposition 98 (1988) establishes a minimum annual funding requirement for schools and community colleges, met with state General Fund and local property tax revenue. When General Fund revenue increases, the minimum requirement usually grows in tandem. Higher revenues, especially in 2024‑25, result in a higher spending requirement on schools and community colleges. The box below describes overall spending on K‑14 education under our outlook.

- All Other Spending Higher by $8 Billion. We estimate spending across the rest of the budget will be higher than the administration’s June 2024 projections by about $8 billion over the budget window. The largest contributors include: the fiscal effects of recently passed propositions, higher‑than‑expected caseload in Medi‑Cal and In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS), an assumption that the state does not achieve all of the state operations savings planned in the 2024 budget, and higher‑than‑expected costs for fighting fires.

- BSA Deposit Slightly Higher. The State Constitution typically requires the state to deposit funds into the BSA when revenues are higher. Consistent with legislative choices from last year, we assume the state suspends deposits into the BSA in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26, which means that changes in revenues for those years have no effect on the BSA. In 2023‑24, a small upward revenue revision results in an additional deposit for that year.

Key Assumptions Underlining This Outlook

How We Reflect Current Law and Policy. Our Fiscal Outlook uses a current law and policy baseline so as to give the Legislature a clear understanding of the budget’s condition based on its most recent set of actions. Typically, our definition of “current law and policy” includes: (1) enacted law and (2) policies the Legislature has a track record of repeatedly enacting, including those to maintain current services. (So, our outlook does not reflect recent proposals by the Governor, like the expansion of the film tax credit.) In recent years, we have expanded this definition to include the costs associated with legislative intent language, as long as it meets certain conditions. This expansion was warranted due to the multiyear plans adopted by the Legislature when the state anticipated significant surpluses. Specifically, we include intent language when: (1) the Legislature voted on and approved the policy, (2) the policy is referred to in budget‑related statutes (for example, in trailer bill) that have force of law, and (3) the policy as described in statute is specific and implementable. In addition, we include intent reflected in floor reports of the adopted budget when they include specific information regarding planned spending. This year, our expanded approach applies to legislative choices made for 2025‑26 to proactively address the deficit anticipated for that year.

Includes Fiscal Effects of Recently Passed Ballot Measures. Our outlook reflects the fiscal effects of propositions approved by voters on the November 5, 2024 ballot. In particular, we have incorporated cost estimates for the two bond measures—one for school facilities and one for climate‑related projects—Proposition 35, which extends the tax on managed care plans, and Proposition 36, which increases penalties for certain theft and drug crimes. Under our estimates, these measures together result in nearly $3 billion in added costs over the budget window, which are nearly exclusively due to increased costs as a result of Proposition 35.

Assumes Administration Does Not End Limitations on Deductions and Credits. The 2024‑25 budget package enacted a temporary increase in corporation tax revenues by not allowing: (1) any businesses to use tax credits to reduce their taxes by more than $5 million and (2) businesses with $1 million or more in income to use net operating loss deductions. These limits apply to tax years 2024, 2025, and 2026; however, statute also gives the Department of Finance the discretion to trigger off these temporary limitations in the event the budget has the capacity to do so. Our projections indicate the budget does not have this capacity, so we have assumed these limitations remain in place. Under our estimates, this results in around $5 billion in revenue in 2025‑26.

After 2025‑26, Assumes Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) Deposits Are Not Suspended. As noted earlier, our outlook reflects the legislative decision to suspend BSA deposits and instead withdraw funds from the account in 2024‑25 and 2025‑26. However, our outlook does not assume that the state continues to suspend BSA deposits in 2026‑27 and later. Suspending those deposits would result in an improvement in the budget bottom line condition by about $3 billion per year.

Does Not Account for Future Disasters. Our outlook accounts for higher costs associated with fighting forest fires as the state’s fire season has become longer and more severe. However, we do not attempt to predict the occurrence of unanticipated, major disasters, for example, an earthquake, pandemic, or fire involving significant destruction of many buildings and other structures. In recent years, the state has experienced disasters—including the COVID‑19 pandemic—that involved historically significant losses of life and carried increased budgetary costs. State costs associated with these and other major disasters are mostly offset by federal funds, although the level of funding for this purpose is contingent on decisions made by the federal government.

Figure 3

Higher Revenues Offset by Higher Costs

(In Billions)

|

End Balance Assumed in 2024 Spending Plan |

$1.5 |

|

Revenues Higher |

$7.1 |

|

School and Community College Spending Higher |

‑2.5 |

|

All Other Spending Higher |

‑7.9 |

|

Rainy Day Fund Deposit Higher |

‑0.2 |

|

Budget Problem at LAO Fiscal Outlook |

‑$2.0 |

|

Note: Positive values improve the budget condition. Negative values |

|

Funding for Schools and Community Colleges

Proposition 98 Creates School and Community College Budget Within Broader State Budget. By requiring the state to set aside certain amounts of funding each year, Proposition 98 (1988) creates a budget for schools and community colleges within the state’s larger budget. The minimum size of this budget—the “minimum guarantee”—is determined by a set of constitutional formulas. Individual school and community college programs, in turn, represent the costs paid out of this budget. This budget also has its own reserve account earmarked exclusively for schools and community colleges. The state must deposit funding into this account when it receives high levels of capital gains revenue and the minimum guarantee is growing quickly relative to inflation.

Proposition 98 Guarantee Revised Up in 2024‑25, Nearly All of the Increase Deposited Into Reserve. Compared with the estimates in the June 2024 budget, our estimate of the minimum guarantee is up $3 billion (2.6 percent) in 2024‑25 (see figure below). Most of this increase reflects our higher estimates of General Fund revenue, but faster growth in local property tax revenue also contributes. Due to our higher estimate of capital gains revenue, nearly all of the growth in the guarantee must be deposited into the Proposition 98 Reserve. The balance in the reserve by the end of 2024‑25 would be $3.7 billion.

Growth in School and Community College Funding

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

|||||||

|

Enacted Budget |

LAO Estimates |

Change |

LAO Estimates |

Change From 2024‑25 Enacted |

||||

|

Amount |

Percent |

Amount |

Percent |

|||||

|

Minimum Guarantee |

$115,283 |

$118,255 |

$2,973 |

2.58% |

$116,799 |

$1,516 |

1.3% |

|

|

General Fund |

$82,612 |

$84,796 |

$2,183 |

2.64% |

$81,747 |

‑$866 |

‑1.0% |

|

|

Local property tax |

32,670 |

33,460 |

789 |

2.42 |

35,052 |

2,382 |

7.3 |

|

Proposition 98 Guarantee Grows Modestly in 2025‑26. We estimate the guarantee in 2025‑26 is $116.8 billion, an increase of $1.5 billion (1.3 percent) from the 2024‑25 enacted budget level. Growth in General Fund revenue and local property tax revenue both contribute to the higher guarantee. An additional contributing factor is the expansion of transitional kindergarten. The June 2021 budget established a plan to expand this program to all four‑year old children by 2025‑26. The Legislature and Governor also agreed to adjust the guarantee upward for the additional students enrolling in the program each year. This adjustment accounts for nearly $800 million of the increase in the guarantee in 2025‑26.

Legislature Would Have $2.8 Billion Available for New Commitments in 2025‑26. Separate from the growth in the guarantee, $3.7 billion in existing Proposition 98 funding becomes freed‑up in 2025‑26. This adjustment is due to the expiration of one‑time spending and several other offsetting changes. After accounting for the freed‑up funding and the cost of providing a 2.46 percent statutory cost‑of‑living adjustment for existing programs, we estimate that $2.8 billion is available for new commitments. The Legislature could allocate this funding for any combination of one‑time or ongoing school and community college priorities. For example, the Legislature could use a portion to eliminate the payment deferrals it enacted in the June 2024 budget.

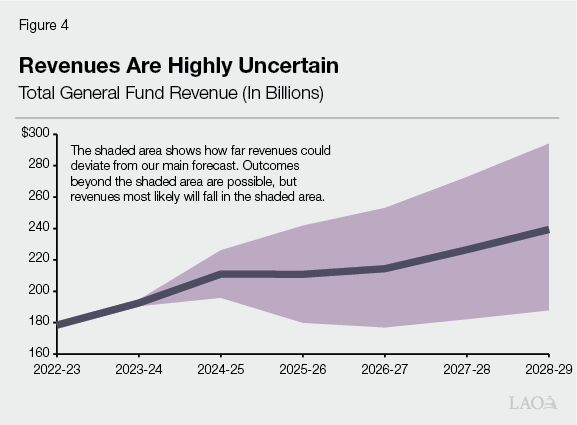

Revenue Uncertainty Always Present in Our Budget Outlook. Our Fiscal Outlooks are always highly uncertain. The main source of that uncertainty is our revenue forecast. As mentioned earlier, in the budget window alone, revenues could easily end up above or below our estimates by $30 billion. Further, as shown in Figure 4, uncertainty only grows into the future.

A Few Key Spending Uncertainties Impact Budget Bottom Line. In addition to revenue uncertainty, the state faces some key uncertainties in the spending estimates:

- Will State Operations Efficiencies Materialize? The 2024‑25 budget package directed the Department of Finance (DOF) to: (1) reduce General Fund state operations expenditures by $2.2 billion ongoing beginning in 2024‑25 and (2) revert $763 million to the General Fund associated with vacant positions in 2024‑25 (this action was made ongoing through permanent reductions of state positions starting in 2025‑26). To date, we have not been able to obtain any information from DOF about the implementation of these reductions among state departments. As such, it is not clear to us how much of these cost savings will materialize. While our outlook assumes the state is able to score some savings associated with each of these actions, the extent of those savings is still unknown. Ultimately, action by the administration could improve or erode those savings relative to our assumptions.

- How Much Will the Healthcare Minimum Wage Ultimately Increase Costs? Late last year, the Legislature passed a bill to increase the minimum wage for many health care workers, and those increases took effect in October of this year. The timing and magnitude of the costs associated with these wage increases—and in particular the costs to the Medi‑Cal program—are uncertain. Estimates of the General Fund share of this cost have ranged from the low hundreds of millions of dollars to the low billions of dollars. Our outlook assumes a figure in between these estimates, but actual costs could be significantly lower or higher than this.

- Why Is the Senior Medi‑Cal Population Growing Rapidly? In the first seven months of 2024, the senior caseload in Medi‑Cal has increased sharply. The average monthly growth of 14,500 senior enrollees during this period is about nine times faster than in the prior six‑month period. We believe that the key driver of this caseload surge is the recent full elimination of the asset limit test—a condition of Medi‑Cal eligibility for seniors that existed to some degree through December 2023. (In addition, IHSS enrollment recently has accelerated, however, readily available data do not specify whether the increased enrollment is concentrated to seniors.) The surge also aligns with the implementation of additional federal flexibilities meant to limit the impacts of eligibility redeterminations being conducted by counties for the first time since the beginning of the pandemic. We assume that the elevated senior caseload continues for a three‑year period, roughly in line with the phase‑in of past eligibility expansions. However, given only several months of data, projecting the exact trend is subject to uncertainty. To the extent that events play out differently, costs could differ significantly from those reflected in our outlook, particularly in 2025‑26.

Further Improvements in Budget Condition Depend on Revenue Timing. Further improvements in revenues are possible, but this year, those improvements have a complicated effect on the budget’s condition. Typically, as a rule of thumb, we say that when revenues improve by $1, the budget bottom line improves by $0.50 to $0.60. This is due to the state’s constitutional formulas, mainly Proposition 98, which typically requires the state to spend an additional $0.40 on schools and community colleges for each $1 of additional revenue. This year, however, the dynamic is more complicated due to “maintenance factor,” which is created when the state has provided less growth in K‑14 funding than the growth in the economy. As a result of maintenance factor, all else equal, improvements in revenues in 2024‑25 could result in a near dollar‑for‑dollar increase in school spending in that year with minimal benefit to the budget bottom line. Upward revisions in 2025‑26, however, would have the typical effect of $0.50 to $0.60 in overall budget improvement for each dollar of new revenue. These dynamics are explained further in our report, The 2025‑26 Budget: Fiscal Outlook for Schools and Community Colleges.

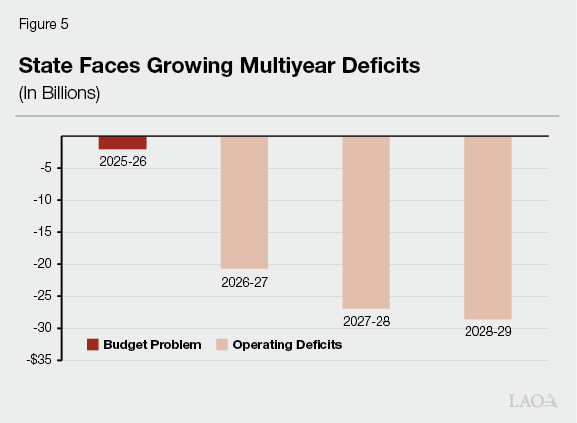

No Capacity for New Commitments

State Faces Annual Multiyear Deficits of Around $20 Billion. Figure 5 shows our forecast of the multiyear condition of the budget. While the budget is roughly balanced in the upcoming fiscal year, the state faces annual operating deficits beginning in 2026‑27—growing from about $20 billion to about $30 billion. Although highly uncertain, these represent additional budget problems the Legislature would need to address in the coming years, for example by reducing spending, increasing taxes, shifting costs, or using more reserves. The magnitude of these deficits also indicates that, without other changes to spending or revenues, the state does not have capacity for new commitments.

Remaining Reserves Could Cover Much of Deficit in 2026‑27. The state has faced significant budget problems over the last two years—by our estimate, a $27 billion deficit in 2023‑23 and a $55 billion deficit in 2024‑25 (excluding early action taken this year). Yet, over this time, the Legislature did not use much of the state’s reserves. Under our outlook, even assuming the state uses $7 billion in reserves in 2025‑26, nearly $11 billion would remain in the BSA. Assuming the Legislature also suspended the otherwise required deposit in 2026‑27, the state could cover about two‑thirds of that year’s budget problem with reserves alone. However, in years thereafter, the state would need to make other changes to address the shortfalls.

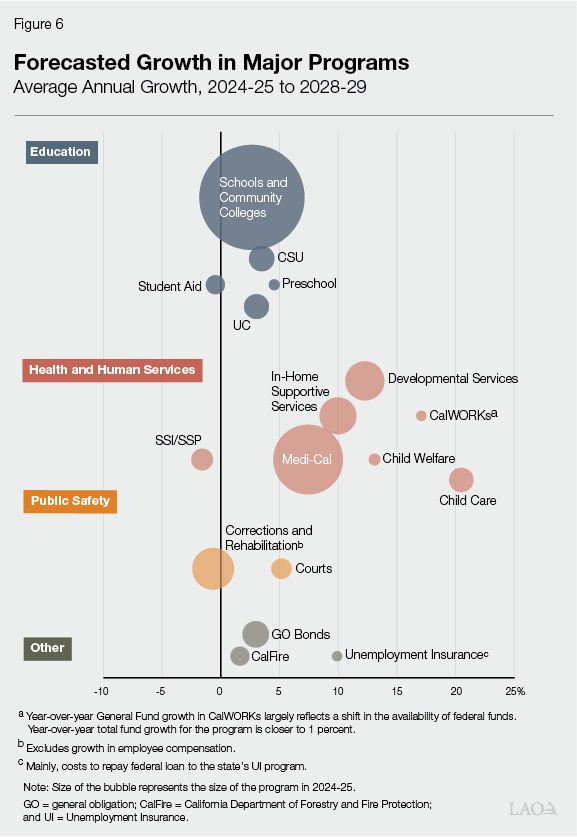

Faster Than Normal Spending Growth Contributing to Deficits. One reason the state faces operating deficits is growth in spending. Our estimate of annual total spending growth across the forecast period—from 2025‑26 to 2028‑29—is 5.8 percent (6.3 percent excluding K‑14 education). By historical standards, this is high. For example, in our last five Fiscal Outlooks, the total annual spending growth rate was 3.5 percent and only 3 percent for spending excluding K‑14 education. While there are always idiosyncrasies in spending patterns that can influence these growth rates—for example, the timing of one‑time spending reductions or anomalies in federal funding—the increase in this growth is contributing to the state’s multiyear deficits.

Spending Growth Driven by Past Program Expansions and Underlying Growth. Figure 6 shows some of the programs that are key drivers of the growth in spending. In some cases, for example IHSS and developmental services, faster growth is standard and largely due to underlying trends in caseload, utilization, and price. However, recent ongoing program expansions are also contributing factors. This includes, for example, the expansion of services, eligibility, and rates in Medi‑Cal; an expansion of child care, including an increase in slots; and several other expansions to human services programs. (For context, our handout, How Program Spending Grew in Recent Years, provides more information on augmentations, including those that are ongoing, in recent budgets.)

Revenues Are Unlikely to Grow Fast Enough to Catch Up to Spending. The state typically faces a deficit when spending exceeds revenues in the budget window and an operating deficit when spending exceeds revenue in future years. An operating deficit—like the ones we currently anticipate—can arise either because of a difference in the levels of revenues and spending (a stable gap over time) or a difference in growth rates (a gap that grows over time). Both are an issue currently, as seen in Figure 7. Our forecasted spending growth is about 6 percent over the forecast period—a growth rate that is high by historical outlook standards and slightly above what we consider to be long‑term revenue growth. Meanwhile, revenue growth over the outlook window is just above 4 percent—this is lower than its historical average largely due to policy choices, namely the limitations on deductions and credits that end during the forecast window. Taken together, we view it as unlikely that revenue growth will be fast enough to catch up to ongoing spending. This means that although the state does not face much of a budget problem this year, in the coming years, legislative action could be necessary to close this gap.

Oversight Key to Budget Management. Understanding which programs are working well and those which are in need of adjustment is a key starting place for considering future budget solutions. As we anticipate future budget problems are more likely than not, we recommend the Legislature conduct robust oversight of programs this budget season. Doing so can provide the Legislature necessary insight for whether the administration is implementing programs according to legislative intent as well as whether programs are achieving the desired outcomes. Particularly given the significant program expansions in recent years and the state’s constrained fiscal capacity, the Legislature now has a key opportunity—if not a necessity—to assess the efficiency, effectiveness, equity, and priority of some of its recent augmentations and longer‑standing programs.

Appendix

Appendix Figure 1

General Fund Spending by Agency Through 2028‑29

(Dollars in Billions)

|

Agency |

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

2027‑28 |

2028‑29 |

Average |

|

Legislative, Executive |

$9.2 |

$4.4 |

$4.3 |

$3.3 |

$3.3 |

$2.7 |

‑14.3% |

|

Courts |

3.4 |

3.2 |

3.5 |

3.6 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

4.2 |

|

Business, Consumer Services, and Housing |

3.5 |

1.3 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

0.2 |

‑8.6 |

|

Transportation |

0.7 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

— |

— |

— |

‑43.6 |

|

Natural Resources |

10.3 |

4.1 |

3.7 |

3.8 |

3.9 |

4.0 |

3.2 |

|

Environmental Protection |

2.3 |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

‑0.1 |

|

Health and Human Services |

73.4 |

74.2 |

78.7 |

82.8 |

93.6 |

100.7 |

8.5 |

|

Corrections and Rehabilitation |

14.9 |

13.9 |

13.4 |

13.4 |

13.5 |

13.5 |

0.2 |

|

Education |

20.6 |

20.2 |

19.5 |

20.7 |

22.0 |

22.3 |

4.6 |

|

Labor and Workforce Development |

1.4 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

1.3 |

1.3 |

12.2 |

|

Government Operations |

4.6 |

2.5 |

4.5 |

4.0 |

3.0 |

5.3 |

5.7 |

|

General Government |

|||||||

|

Non‑Agency Departments |

2.8 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.7 |

1.2 |

‑0.7 |

|

Tax Relief/Local Government |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.7 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

3.8 |

|

Statewide Expenditures |

2.0 |

‑0.4 |

4.4 |

5.3 |

6.6 |

7.0 |

16.9 |

|

Capital Outlay |

0.8 |

0.6 |

— |

0.1 |

— |

0.1 |

32.3 |

|

Debt Service |

5.3 |

5.9 |

6.1 |

6.3 |

6.5 |

6.8 |

3.7 |

|

Non‑98 Spending Total |

$155.7 |

$133.1 |

$141.6 |

$146.9 |

$160.5 |

$170.1 |

6.3% |

|

Proposition 98a |

$67.1 |

$84.8 |

$81.7 |

$85.2 |

$89.7 |

$94.1 |

4.8% |

|

Proposition 2 Infrastructure |

0.7 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Total Forecasted Spending |

$222.8 |

$217.9 |

$223.3 |

$232.1 |

$250.3 |

$264.2 |

5.8% |

|

aReflects General Fund component of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. bFrom 2025‑26 to 2028‑29. |

|||||||