December 2, 2024

- Introduction

- California’s UI System Is Broken

- How Did We Get Here?

- Financing Issues Also Undermine Some Objectives of the Program

- Recommendations

- Final Considerations

- Infographic - Fixing Unemployment Insurance

Executive Summary

The State’s Unemployment Insurance (UI) Financing System Is Broken. The state’s UI program is supposed to be self‑sufficient—that is, the system should collect enough funds to pay for benefits over time. This means, in some years, the system will collect more than necessary so that, during most economic downturns, there is enough money to pay for rising benefit costs. That system is broken: tax collections routinely fall short of covering benefit costs. (The state’s fiscal problems are unrelated to the widespread fraud that affected temporary federal UI programs during the pandemic.) Both our office and the administration expect these annual shortfalls to continue for the foreseeable future. Under our projections, deficits would average around $2 billion per year for the next five years. This outlook is unprecedented: although the state has, in the past, failed to build robust reserves during periods of economic growth, it has never before run persistent deficits during one of these periods.

Mounting Consequences of the State’s Broken UI Financing System. The state’s broken UI system now presents mounting consequences:

- Annual Shortfalls Will Balloon Outstanding Federal UI Loan. Anticipated annual shortfalls will add to the state’s looming $20 billion outstanding federal UI loan. We expect the loan to grow by billions of dollars before federal surcharge UI taxes are high enough for the state and employers to begin making progress toward repaying the loan.

- Loans Will Become a Permanent Feature of UI and a Major Ongoing Taxpayer Cost. The state will need to borrow from the federal government in most years to make up the gap between UI benefits and contributions. This means that businesses could face a perpetually outstanding federal loan, on which the state must make interest payments. These interest costs will be significant, likely around $1 billion per year, and paid by the state’s taxpayers.

- UI Program Will Be Unable to Build Reserves Ahead of Next Recession. Although a federal surcharge on businesses will help repay the federal loan, the surcharge cannot help the state build reserves after the loan is repaid. This is because the surcharge turns off once the loan balance reaches zero. Absent the federal surcharge, little or no reserves would be on hand at the start of the next recession, further increasing the state’s reliance on costly federal loans.

Broken Financing System Also Undermines Key Objectives of the UI Program. The state’s UI system faces other problems, too. First, state UI benefits cannot keep up with inflation or provide the intended wage replacement of half of workers’ wages. Second, the state’s approach to setting employer tax rates (a system called “experience rating”) has the effect of depressing take‑up of UI benefits among eligible, unemployed workers. Third, the state’s lowest‑in‑the‑nation taxable wage base deters employers from hiring lower‑wage workers. In each case, our proposed fixes to the UI financing system would eliminate, or at least mitigate, these related shortcomings.

Four Recommendations to Fix the System. The state’s UI tax system requires a full redesign so that contributions: (1) cover benefit costs in most years and (2) build up a reserve that can be drawn down during recessions. We recommend four main areas of change:

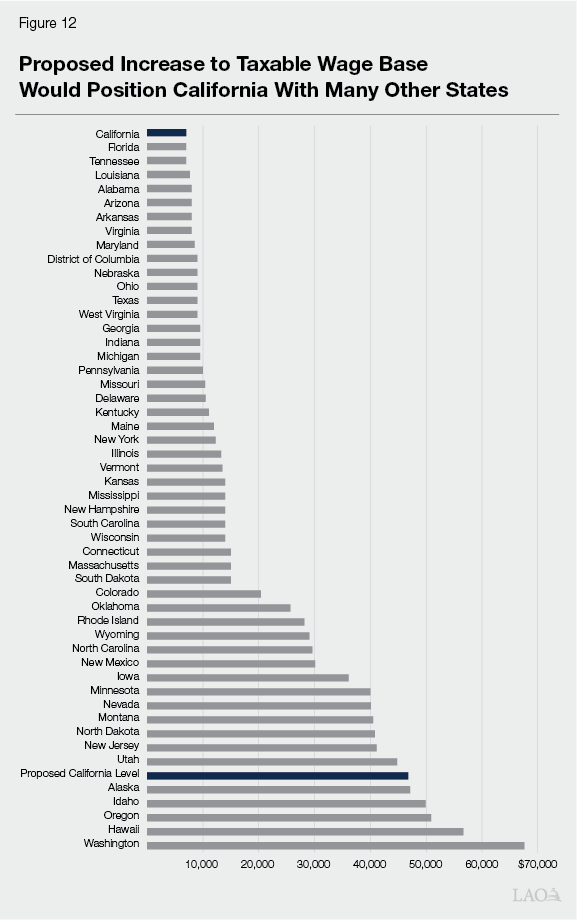

- Substantially Increase the Taxable Wage Base. We recommend the Legislature increase the taxable wage base from $7,000 to $46,800, tying the taxable wage base to the amount of UI benefits a worker can actually receive ($450 per week). Taxing this level of earnings means no taxes would be paid on wages that are not covered by UI. This taxable wage base level would place California among the ten states with taxable wages bases above $40,000 and all other Western states. While necessary, this step alone would not be sufficient to address the state’s solvency problems.

- Redesign Employer Tax Rates Using Standard Rate and Reserve‑Building Rate. Following federal guidelines, we recommend the state adopt a simple, robust UI tax structure comprised of a standard tax rate and a reserve‑building tax rate. The standard tax rate would cover typical UI benefit costs. The reserve‑building rate would help the state build up a robust reserve that can be drawn down during recessions. Under current conditions, the standard tax rate would be 1.4 percent and the reserve‑building rate would be 0.5 percent, for a total of 1.9 percent UI tax rate applied to our proposed $46,800 taxable wage base.

- Transition to Experience Rating System with Fewer Downsides. We recommend the Legislature transition to a new experience rating system that bases employers’ tax rates on increases or decreases in their employment, rather than an exact accounting of their former workers’ UI costs (as the current system operates). This approach would continue to reflect, indirectly, employers’ costs to the UI system because business that reduce employment tend to have higher UI usage. Thus, this alternative approach maintains the policy goals of experience rating but does not suffer from the main downsides of the current system.

- Refinance the Federal Loan With Shared Participation Between Businesses and the State. The outstanding federal loan complicates the state’s efforts to fix its broken UI financing system: as long as the federal loan remains outstanding, even an improved tax system would probably not be able to build reserves ahead of the next recession. To address this, and in acknowledgment of the unique nature of the pandemic that caused the significant UI loan, we outline a shared approach to refinancing the federal loan. This would involve two equal parts: (1) a revenue bond paid back by employers and (2) new borrowing from the Pooled Money Investment Account paid back by the General Fund.

Our Approach Could Still Involve Loans, but They Would Be Smaller and Less Frequent. Our approach would help the state build reserves ahead of recessions, but does not represent an overly cautious tax system designed to avoid federal loans at all costs. If the state adopted our approach, there would be some years that California would run out of reserves during a recession and require a loan from the federal government. Yet these loans would be smaller and less frequent. For example, if California had entered the pandemic with equivalently sized reserves, it still would have required a federal loan, but that loan would have reached $9 billion, rather than $20 billion. As a result, our approach represents a significant improvement over the status quo, which likely involves near‑permanent outstanding federal loans for decades to come.

Magnitude of Tax Increase and New Borrowing an Honest Reflection of UI Program’s Imbalance. The scope and magnitude of our recommendations reflect the deep problems in the existing UI system. These include: (1) the staggeringly large and growing loan from the federal government and (2) the fact that the system is currently running a deficit even during an economic expansion. These are significant problems in isolation, let alone in combination. The significant changes proposed in this report are an honest reflection of these problems. However, whether or not the Legislature takes action, employers will soon pay more in UI taxes than they do today due to escalating charges under federal law. Making changes now will allow the Legislature to make strategic choices about how to repay the federal loan, while also replacing the UI financing system with one that is simpler, balanced, and flexible.

Introduction

California’s Unemployment Insurance (UI) program provides temporary wage replacement to unemployed workers. In so doing, UI helps alleviate temporary economic challenges for workers and their families and also bolsters the state economy during economic downturns. Despite its importance to workers and the economy, the state’s UI program financing system is broken. Unemployment benefits now routinely outpace incoming tax contributions, leading to a costly reliance on federal loans and constraining the state’s options to improve the program. This report describes the problems with the system in greater detail, including offering historical context and our projections of the future. We then offer four recommendations that would fix the state’s broken UI system.

California’s UI System Is Broken

California’s UI Program Is Funded by Taxes and Pays Unemployment Benefits. The state’s UI program is a state‑federal partnership under which workers receive partial wage replacement if they lose their job through no fault of their own. Employers pay a payroll tax on each worker to fund benefits. These payroll taxes—the tax rate currently averages 3.5 percent on the worker’s first $7,000 in annual wages, or about $250 per year for each worker—are paid into the state’s UI trust fund. On average, employers pay a total of $5 billion to $6 billion into the fund each year. When an eligible worker becomes unemployed, the state pays the workers’ benefits out of the trust fund. Unemployed workers can receive 50 percent of their regular wages, up to a maximum of $450 per week, for up to 26 weeks. (Due to the $450 weekly benefit maximum, about half of workers receive less than 50 percent of their regular wages.)

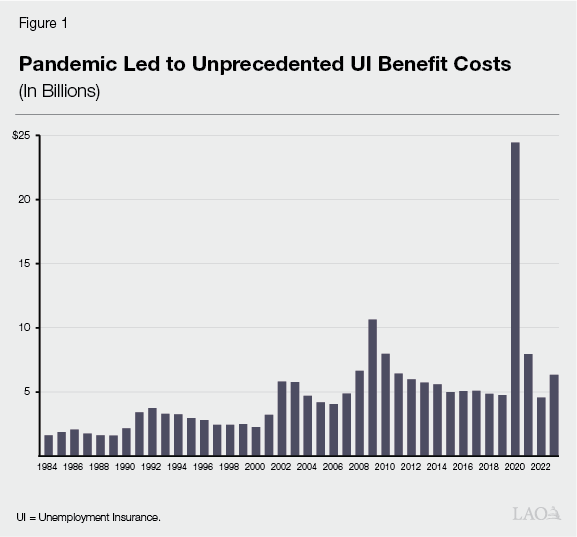

With Small Reserves, System Experienced Massive Benefit Costs in 2020. While the state’s UI system has faced fiscal hurdles for decades, the pandemic represented an unprecedented challenge to the system. The state entered the pandemic with about $3 billion of reserves in the UI trust fund. This was not nearly enough to cover the heightened benefit costs that occur during a normal recession, let alone one of this scale, in which about 1 in 5 California workers would eventually receive UI benefits. By the end of 2020, as shown in Figure 1, the state had distributed $24 billion in UI benefits to unemployed workers and quickly ran through its reserves. Under federal rules, states must borrow federal dollars to pay benefits when state reserves run out. Over the course of the pandemic, the state borrowed about $20 billion to keep paying benefits associated with the state’s UI program. (The federal government expanded benefits during the height of the pandemic, and some of these expanded benefits were subject to significant levels of fraud. These fraudulent payments are not a contributor to the state’s outstanding loan, however.)

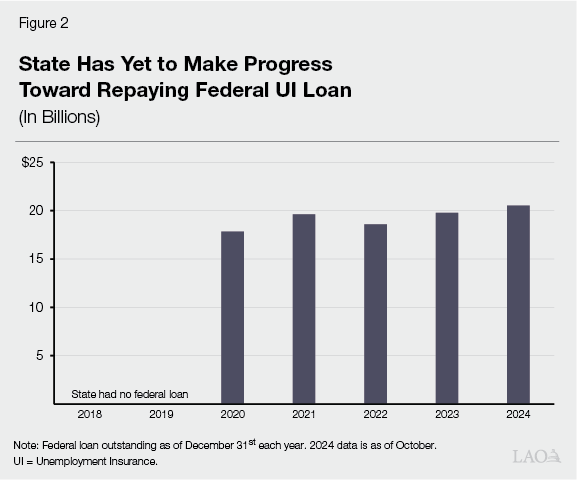

State Now Has $20 Billion Loan Outstanding… Since the pandemic ended, employer contributions have not been large enough to make progress toward repaying the federal loan. As Figure 2 shows, the outstanding loan balance has remained essentially the same since late 2021. Under the federal loan repayment rules, employers now face escalating federal UI taxes that will be directed toward repaying the loan principal. This federal surcharge—technically referred to as the Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) tax credit reduction—will keep increasing by 0.3 percent each year (up to 5.4 percent in total) until the loan is repaid. (The state’s General Fund customarily makes annual interest payments on the loan.) The state is entering its fourth year of repayments, and so employers will pay an additional 1.2 percent federal surcharge in 2025 (equivalent to $84 per worker).

…Which Will Continue to Grow. The state will eventually repay the outstanding federal loan, but not until the federal surcharge gets high enough to generate substantial contributions for repayment. The outstanding loan is very likely to grow by billions of dollars over the next several years before the federal surcharge contributions are large enough to begin making progress toward repayment. During this period, state General Fund interest costs will likely be about $1 billion per year.

Concerns Over Trust Fund Solvency Have Impeded Benefit Increases and Expansions. In recent years, the Legislature has expressed interest in increasing UI benefit levels. Benefits were last increased in 2004 and have not been adjusted for cost‑of‑living increases since, including through the recent period of historically high inflation. The Legislature also has pursued expanding UI coverage to workers who have not typically received benefits, including striking workers, undocumented workers, and independent contractors. The imbalance in the current financing system has stymied these efforts, however. For example, the Governor recently vetoed a bill to expand UI to striking workers, citing fiscal challenges with the state’s UI trust fund. To move forward with these types of changes or others, the state needs to fix the system.

Our Approach to Fixing the State’s UI System. Although the pandemic pushed the state’s UI system past the breaking point, the genesis of this crisis traces back decades—as early as the 1980s. In this report, we: (1) present the evidence showing that the state’s UI financing system is broken; (2) detail how chronic insolvency in the current system undermines some of the program’s core objectives; and (3) recommend a path forward with a simpler, balanced, and flexible UI financing system.

How Did We Get Here?

State UI programs are supposed to be self‑sufficient—that is, the system should collect enough funds to pay for benefits over time. This means, in some years, the system will collect more than necessary so that, during economic downturns, there is enough money to pay for rising benefit costs. To ensure revenues match benefits over time, states enacted UI financing systems. These systems are comprised of three elements: (1) a tax rate “schedule” that adjusts up or down to match revenues and benefit costs, (2) a taxable wage base level to which the tax rate applies, and (3) an experience rating factor to ensure employers pay their fair share of UI costs. In this section, we present the evidence that California’s UI financing system is broken—that is, it is not self‑sufficient and cannot collect enough funds to pay for benefits over time.

Tax System Has Not Withstood the Test of Time

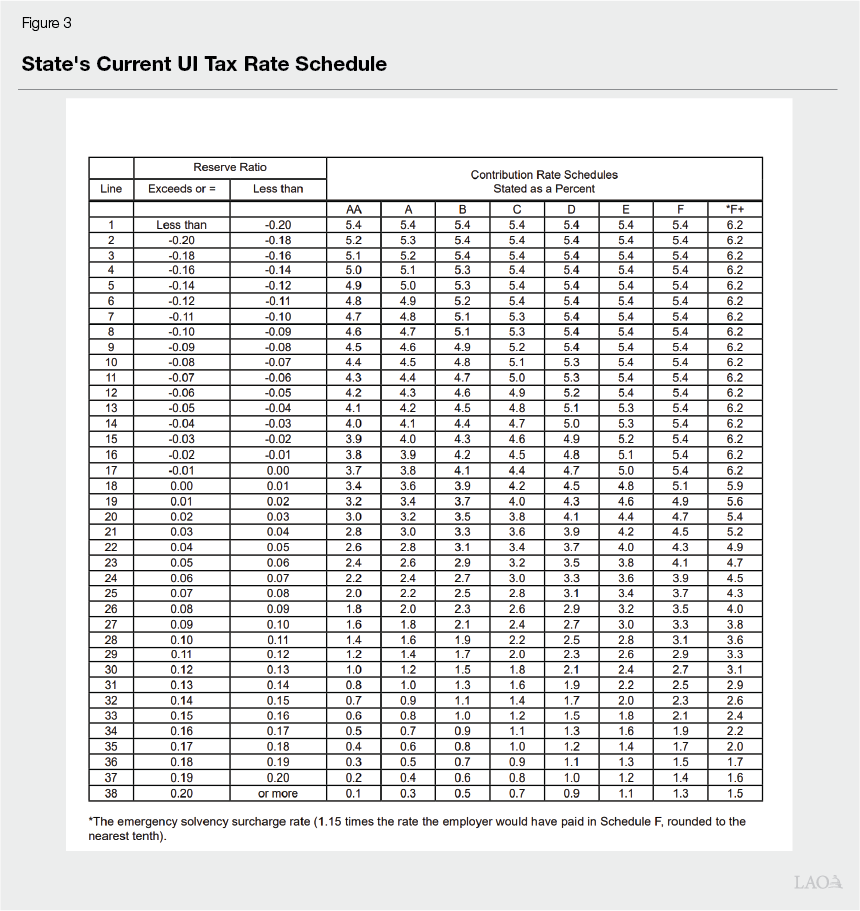

Tax System Dates Back to 1984. California’s state‑federal UI program was first enacted after the Great Depression. The state’s modern UI tax system dates back to 1984, when the state instituted a new tax system to conform with federal UI changes. This legislation set the taxable wage base at $7,000, the minimum amount allowed under the federal changes. (The taxable wage base is the amount of earnings that are taxed to fund benefits. That is, employers do not pay UI payroll taxes on worker earnings above the taxable wage base.) The legislation also created a system of tax schedules, ranging from Schedule AA to Schedule F+. The schedule is intended to shift tax rates higher when the UI trust fund is depleted and lower when the trust fund has enough reserves. Employer tax rates are lowest (Schedule AA) when the UI trust fund has large reserves and highest (Schedule F+) when the fund has a negative balance. When first established, the state was toward the bottom of the schedules (Schedule D)—corresponding to relatively high rates—and had a sizable reserve for the time.

1984 Legislation Also Put Forth State’s Current Experience Rating System. Experience rating is a standard feature of UI and functions similarly to risk‑based pricing in an insurance market. As with car insurance, for example, where premiums are adjusted based on an individual’s risk profile (that is, driving history), experience rating aims to adjust employers’ tax rates based on their “risk” of future layoffs. Under this idea, employers with a higher risk of their workers claiming UI benefits should be viewed as riskier and charged higher premiums (that is, higher UI tax rates). The state’s 1984 legislation put forth the state’s current system of experience rating, known as a reserve‑ratio experience rating system. Under this approach, the Employment Development Department (EDD), the state’s UI administrator, keeps track of each employers’ cumulative UI costs and cumulative UI contributions since the company formed. When costs and contributions are equal, the business’ reserve “ratio” is zero. Businesses with a positive reserve ratio (contributions higher than costs) pay a lower UI tax rate and businesses with a negative ratio (costs higher than contributions) pay a higher tax rate. State law sets out 38 different tax rates for businesses based on their reserve ratio (shown as rows in Figure 3). When overlaid with the state’s eight statutory tax schedules (shown as columns in the figure, which change based on the UI trust fund balance), California businesses pay 1 of 304 UI tax rate options.

Early Tax System Was Able to Weather First Recession. After the 1984 reforms, the state entered its first recession with the new UI financing system in place in the early 1990s. The state was able to cover benefit costs for heightened UI caseload during this recession without depleting the trust fund. There are two main reasons the system successfully weathered its first recession. First, the state entered this recession with a relatively robust reserve on hand with much of this reserve balance built before the tax changes enacted in 1984. Second, at the time, the state offered more limited UI benefits (the state would soon increase benefits, as discussed below). The tax rate schedule still had room to adjust during this time, as intended, to keep contribution levels sufficient to maintain an ongoing reserve.

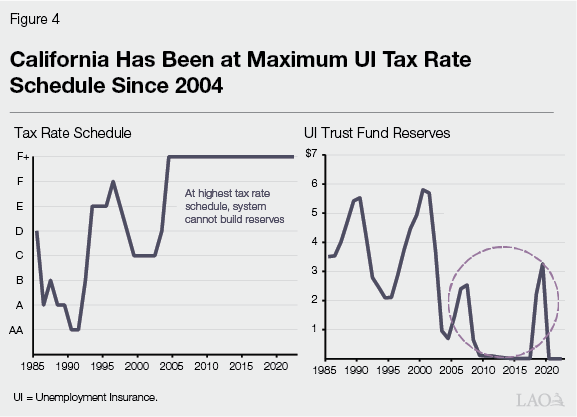

Benefit Increases Coincided With 2001 Recession. Coming out of the recession in the early 1990s, California’s UI benefits (as a share of average wages) were the lowest in the country. At the time, average benefits replaced roughly 20 percent to 25 percent of workers’ average wages. In response, the state increased UI benefits in 2001. This legislation: (1) increased the maximum weekly benefit from $230 per week to $450 per week and (2) increased the wage replacement rate from 39 percent to 50 percent. These increases were phased in between 2001 and 2005. During the phase‑in period, the state also entered the dot‑com recession. These two cost pressures absorbed the remaining flexibility in the state’s UI tax system. As shown in Figure 4, the state began this period in Schedule C but quickly moved to Schedule F+, the highest tax schedule, where it has remained since.

Tax System Had No Room to Work in the Great Recession. When the state entered the Great Recession, the UI tax system already was at the maximum tax rate schedule (Schedule F+). Although the state had a small reserve leading up to the recession, it was not sufficient to lower the tax rate schedule. Moreover, given the reserve was modest, it was quickly depleted as unemployment and benefit costs increased during the Great Recession. To continue paying UI benefits, the state borrowed $11 billion from the federal government. From 2011 through 2018, California businesses paid the federal surcharge to repay the loan principal while the General Fund made a total of $1.4 billion in interest payments.

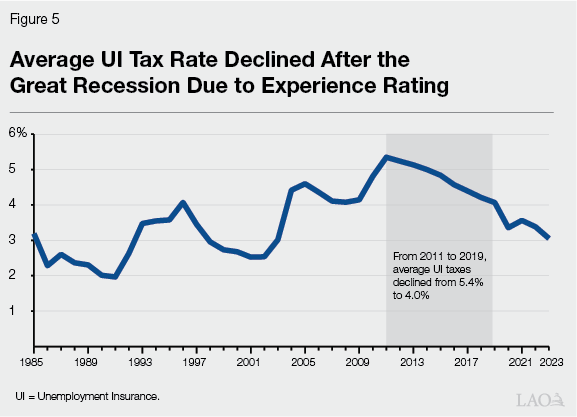

After Great Recession, Tax Rates Declined, Worsening an Already Poor Position. Although the long economic recovery that followed the Great Recession should have provided the system with an opportunity to build reserves, experience rating prevented the system from functioning as intended. The state remained in the F+ schedule for this entire period. Yet, as the state’s economy recovered, employers’ experience rating reserve ratios began to improve because fewer workers were receiving UI benefits. In other words, paradoxically, businesses’ improving reserve balances moved them to lower tax rate rungs within the F+ schedule, which had the effect of lowering state UI tax rates, as shown in Figure 5. (This occurred even as those businesses were paying the escalating federal surcharge to repay the outstanding loan.) Statewide, these lower tax rates prevented the state from building the UI trust fund reserve during this historically long economic expansion. In short, the F+ schedule carries insufficient tax rates to build reserves, which means the state has remained stuck at this rate schedule.

After Historically Long Economic Expansion, State Entered Pandemic With Minimal Reserves. The state entered the pandemic with $3 billion in the UI trust fund. The pandemic resulted in a historic surge in unemployment and, as a result, unprecedented state UI costs. The state distributed a total of $24 billion in state UI payments in 2020—more than double the former peak from the Great Recession. (This amount does not include payments from the temporary federal UI programs that were the subject of widespread fraud.)

Pandemic‑Era Polices Exacerbated Underlying Shortcomings of Tax System. During the pandemic, the Legislature passed a new policy to disregard pandemic benefit costs when calculating employers’ experience rating tax rates. The intention was that businesses should not face higher UI costs due to layoffs related to the public‑health shutdowns that were clearly outside of their control. This policy, which we refer to as “non‑charging,” had the effect of substantially lowering employers’ tax rates relative to what they otherwise would have been. As shown in Figure 6, absent the non‑charging policy, we estimate that average tax rates would have been above 5 percent rather than around 3 percent.

These lower‑than‑expected tax rates have exacerbated the state’s long‑standing imbalance between benefits and contributions, contributing to the state’s current structural deficit. This is not a temporary problem. Under the state’s experience rating system, non‑charging will keep UI tax rates artificially low for many years because businesses’ reserve ratio calculations are cumulative—that is, they weigh the businesses’ lifetime UI costs and contributions—and those balances will forever exclude the pandemic‑era non‑charged benefits.

Why Hasn’t the State’s Tax System Worked? The state’s UI tax system—including its tax rates, tax schedule, taxable wage base, and experience rating—cannot generate sufficient employer contributions to build and maintain adequate reserves. In a well‑functioning system, an employer’s experience rating reflects their individual costs to the UI program, while the tax schedule adjusts to ensure that the fund receives enough contributions overall to cover benefit payments. However, in the state’s system, both mechanisms have broken down. Each year, between 10 percent and 40 percent of employers reach the maximum UI tax rate, capping their contributions despite their benefit costs exceeding those contributions. Ordinarily, the tax schedule would increase when trust fund reserves decline, raising contributions for all employers to offset these shortfalls. But in the current system, the tax schedule is constrained and unable to rise further. As a result, the system cannot accommodate these unaccounted‑for costs or generate the reserves needed to safeguard against future shortfalls. This breakdown means that the experience rating system, instead of ensuring higher contributions from employers with higher UI costs, actually contributes to lowering the average tax rate at a time when increased funding is crucial to rebuilding reserves.

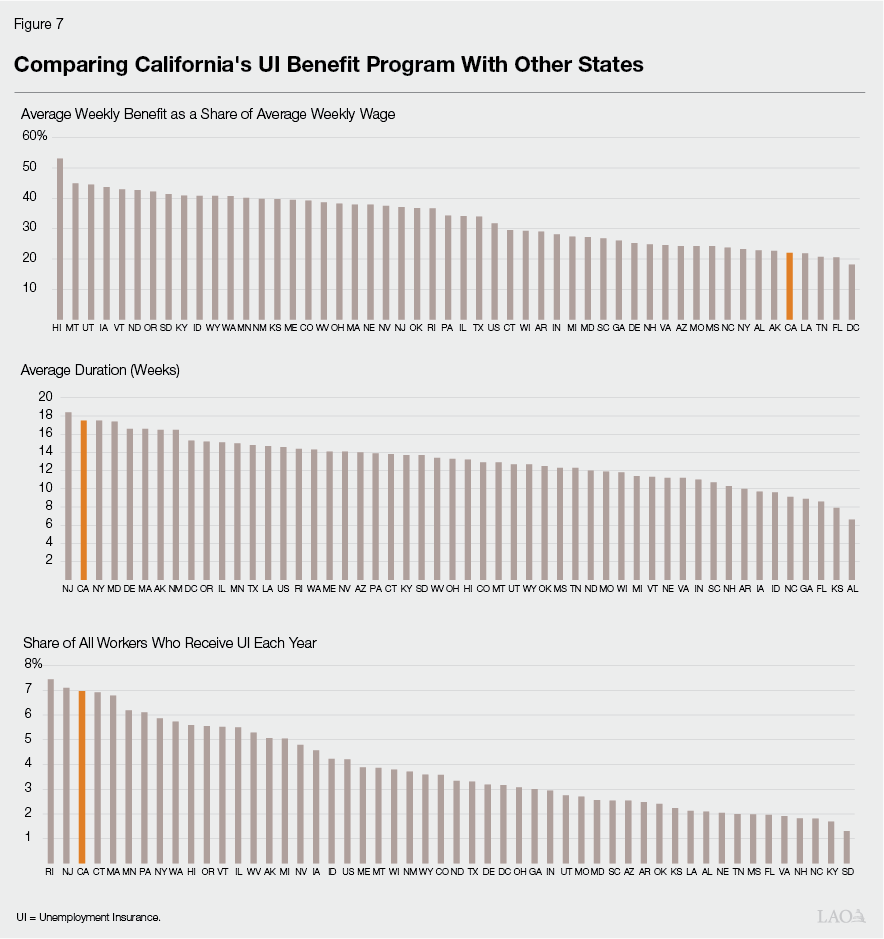

Comparing California’s UI System to Other States Sheds Additional Light on Program Imbalance. Comparing California’s UI system to other states offers another perspective on these fiscal challenges. Relative to other states, California’s UI system:

- Pays Relatively Low Benefits, Yet Has High Total Costs. While California’s UI program provides lower weekly benefits relative to wage levels than almost every other state, the program tends to pay benefits for a slightly longer‑than‑average duration and to a larger‑than‑average caseload (see Figure 7). In part, this is due to structural elements of the state’s economy: unemployment tends to be slightly higher in California than elsewhere. Additionally, although the state’s benefit levels are low relative to state wages, wages in California are among the highest in the country. This means that absolute weekly benefit amounts remain higher than average. As a result of these dynamics, the state’s UI program has higher‑than‑average total costs.

- Has a Below Average Tax Burden. Despite many employers paying the maximum UI tax rate, the state’s UI tax burden is below average compared to the rest of the United States. Even at the state’s maximum tax rate of 5.4 percent, when offset by the state’s low taxable wage base, employers’ tax payments are comparable to the national average. For example, in 2023, California employers contributed 0.33 percent of their employees’ total wages toward UI, on average. This is somewhat lower than the national average (among U.S. states) of 0.47 percent.

When compared to other states, California’s UI system combines high total costs with a below average tax burden. Unsurprisingly, this has resulted in an imbalanced UI system.

Going Forward, Imbalance Expected to Worsen

Administration Forecasts Continued Structural Deficit for Next Several Years. Both the administration and our office expect the UI trust fund to run annual operating deficits over the next several years. The administration’s forecast, which assumes a steady economy, estimates deficits of a bit under $1 billion through 2025. Our assessment, which examines many potential future paths for the state’s economy, similarly finds deficits are very likely to persist regardless of the trajectory of the economy, with an average outcome yielding deficits of around $2 billion per year for the next five years. This outlook is unprecedented: although the state has, in the past, failed to build robust reserves during periods of economic growth, it has never before run persistent deficits during one of these periods.

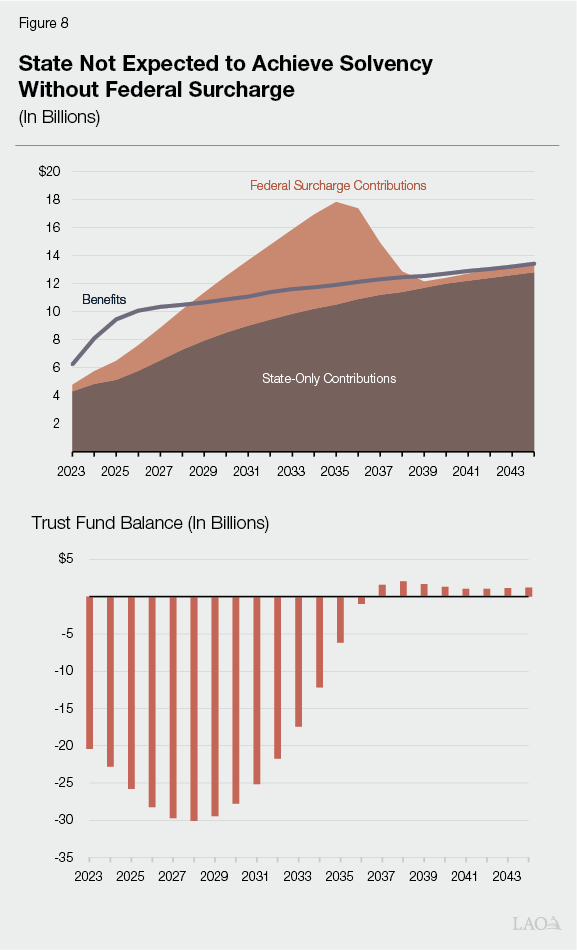

With Imbalance, Federal Surcharges Are State’s Only Path to Repay Federal Loan. The state’s UI system already has a significant outstanding loan owed to the federal government—currently $20 billion—and these projected deficits will only add to that balance. Not only will the state’s tax system fall short of repaying that loan, the balance is set to grow due to the ongoing gap between contributions and benefits. As such, the state’s only path to repaying the loan is through the federal surcharge that will continue to ramp up until the loan is repaid. The state’s loan is so significant that it is likely to remain outstanding, and the federal surcharge in place, for at least another decade. Figure 8 shows how this would play out if contributions and benefits continue to track with historical trends over the next two decades. As the figure shows, we do not expect the state to achieve solvency without the federal surcharge.

State Tax System Cannot Build Reserves Ahead of Next Recession. The federal surcharge is designed to temporarily increase employer contributions to repay the federal loan, and it drops to zero once the trust fund balance reaches zero (meaning the loan has been repaid). The federal surcharge, therefore, cannot help the state build reserves. As a result, the state’s UI tax system is now stuck in an insolvency cycle. Each time businesses repay the federal loan relying on the federal surcharge, their state UI contributions will again fall short of covering benefits. Once this occurs, the state will need to once again turn to federal loans to cover normal, annual program costs with no opportunity to build up much in reserves. Given that a recession is likely to occur in the next decade, California will almost certainly enter the next recession with a federal loan outstanding. Even if the state manages to repay the pandemic‑era loan before the next recession, little or no reserves would be on hand at the start of that downturn.

Loans Will Become a Permanent Feature of UI and a Major Ongoing State Cost. Although federal law intends the UI program to be self‑sufficient, it also prohibits states from using UI trust funds to pay the interest costs associated with a UI loan. California has customarily paid these costs with the General Fund, although some interest costs could, in theory, be covered by other state funds. Either way, UI loan interest costs are paid by a broad base of California taxpayers, rather than employers. Over the next decade, these interest costs will be significant, with the state’s General Fund likely paying around $1 billion per year. This will become a near‑permanent feature of the state’s UI program and a major ongoing cost for state taxpayers.

Financing Issues Also Undermine Some Objectives of the Program

While the biggest problem with the state’s broken financing system is a failure to fulfill its fundamental purpose—sustainably funding unemployment benefits—this system also has several other drawbacks that undermine core objectives of the program. Specifically: (1) state benefits do not keep pace with inflation or meet the federal standard for wage replacement; (2) although ensuring broad and equitable access is a legislative priority, the tax system depresses take‑up in the program; and (3) although one goal of the UI system is to stabilize employment, California’s UI tax system deters hiring of low wage workers. We review these issues in this section.

Benefits Do Not Keep Up With Inflation or Hit Wage Replacement Target

California’s Benefits Are Not Indexed to Inflation. UI benefits increase with income, but the maximum amount a worker can receive is $450 per week—a level set in legislation passed in 2001. If this benefit level had been adjusted for inflation, the state’s maximum weekly benefit amount would be $765 today. This means that California’s maximum benefit has, in real terms, fallen by nearly half over the last two decades.

California’s Benefits Meet Federal Standard for Only Half of Workers. The UI program is intended to replace half a worker’s wages for 26 weeks. A worker will receive the maximum weekly benefit if they make at least $900 per week or $46,800 per year. Workers who make more than this amount will receive less than half of their earnings in UI benefits. When the current benefit levels were enacted in 2004, a minority of workers in California—about 30 percent—had wage income greater than this level. Today, it is about 50 percent. While it is reasonable to expect that some workers would make too much money for UI to replace half of their earnings, California’s benefit levels only meet the federal wage replacement standard for half of the state’s workers.

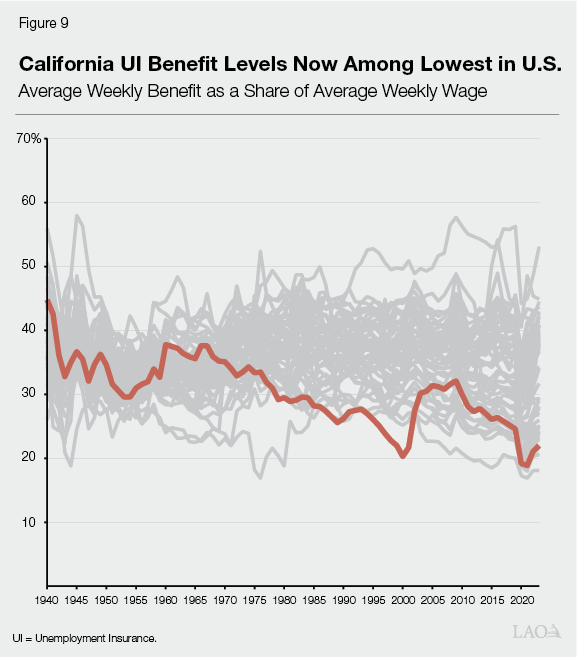

California’s Wage‑Adjusted Average Benefit Is Near the Bottom of U.S. States. In unadjusted dollar terms, at $380 per week, California’s average weekly benefit rank around the middle of U.S. states. However, wages are higher in California than they are in most other states. As a result, California’s average weekly UI benefits as a share of average weekly wages rank near the bottom, as shown in Figure 9.

Although Benefit Increases May Be Warranted, Changes Are Unworkable Under Current System. The state’s benefit levels are low compared to other states, benefits meet wage replacement standards for only half of workers, and benefits have not kept pace with inflation for the past two decades. Amid this bleak backdrop, the state’s UI system is insolvent and even minimal benefit adjustments are unworkable. A functioning UI tax system should, at a minimum, have the capacity to fund the state’s current benefit levels and provide enough flexibility to allow those benefits to be inflation‑adjusted over time. The state’s current financing systems falls far short of this modest standard.

Depresses Take‑Up

Less Than Half of Unemployed Workers Receive UI Benefits. According to federal program reporting, each year about 40 percent of unemployed workers in California receive unemployment insurance (this is the state’s take‑up rate among all unemployed workers). Some unemployed workers are not eligible for UI for various reasons, so the federal tally understates take‑up among eligible unemployed workers. In relative terms, California’s take‑up rate is high when compared to other states. However, in absolute terms, and as described in the nearby box, the state’s take‑up rate is not particularly high and thus many eligible workers do not apply for or receive benefits. The four most common reasons why eligible workers do not apply for UI include: (1) they did not think they were eligible, (2) they expected to get a new job soon, (3) they expected their employer to rehire them soon, or (4) their employer told them they were not eligible.

California’s Unemployment Insurance (UI) Take‑Up Rate in Context

State’s Take‑Up Rate Above Average When Compared to U.S. On average across all states, about 30 percent of unemployed workers receive UI benefits. In California, about 40 percent of all unemployed workers receive UI benefits—ranging from 35 percent to 50 percent over time—giving California the 10th highest take‑up rate nationally among all workers. However, many unemployed workers are not eligible for UI benefits. This includes, for example, workers who voluntarily left their jobs or were dismissed for misconduct. Nationally, take‑up among this smaller group—eligible unemployed workers—has recently been measured close to 70 percent. We do not have a similar figure for California specifically.

UI Take‑Up Rate Is In‑Line With Other State and Federal Benefit Programs. The national UI take‑up rate among eligible unemployed workers is roughly similar to estimated statewide take‑up rates in other programs. These include the state’s food assistance program (CalFresh, 77 percent take‑up rate), the state’s cash assistance program (California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids [CalWORKs], 60 percent), and the federal tax credit for low income tax filers (the federal Earned Income Tax Credit, 80 percent). These take‑up rates, including the estimate for CalWORKs produced by our office in 2021, are calculated using different methodologies and so may not be exactly comparable. They nevertheless represent a useful comparison to provide additional context for the state’s UI program.

Current Tax System Creates an Incentive for Employers to Limit UI Costs. Under the state’s experience rating system, individual employers’ tax rates increase when their former employees collect UI benefits. Among other goals, this was intended to provide a financial incentive for employers to limit UI costs by discouraging the employer from laying off workers. However, the same incentive to limit layoffs also leads some employers to appeal their workers’ UI claims, even valid ones, and provides no encouragement for employers to assist former workers in accessing benefits. These incentives prompt some employers to hire third‑party companies to manage the employers’ UI claims, including representing the employer at appeals, to limit UI costs. As a result, many workers believe they are ineligible (or are told they are ineligible) and are less likely to apply for UI benefits at all. Moreover, some employers dispute all UI claims, regardless of validity, which might also result in some eligible workers not receiving benefits.

Fewer Eligible Workers Apply for UI at Businesses That Regularly Appeal Claims. Recent research conducted in Washington State, with a similar experience rating system as California, shows that some businesses limit UI take up by appealing a large share of claims or discouraging workers from claiming UI. The researchers found that fewer workers apply for UI when their former employer regularly appeals UI claims—an apparent “deterrent effect.” Overall, the underlying incentive in the state’s current experience rating system to limit UI costs works against the state’s objective to maximize take‑up among eligible unemployed workers, although the extent of this effect is unknown.

Deters Hiring of Low‑Wage Workers

Economists Focus on the “Economic Incidence” of Taxes. Tax incidence refers to who bears the burden of a tax. Tax incidence can take two forms: economic and legal. “Legal incidence” is simply who initially pays the tax. In the case of UI taxes, it is always the employer. Economic incidence refers to the entity that ultimately bears the cost of the tax and therefore is more important for policymaking. The economic incidence of the UI tax can mainly fall on either (or both) employers and workers. In general, when the incidence mostly falls on the employer, it results in increased costs for them. Employers can respond to these cost increases by reducing employment (for example, through reduced hiring or increased layoffs) or by reducing profits. When it mostly falls on the employee, it has the effect of reducing wages. These effects can vary in size.

Empirical Evidence Suggests Payroll Taxes Generally Reduce Employment, Especially of Low Wage Workers. The best available empirical evidence suggests that the burden of payroll taxes mainly falls on employers and that increases in those taxes result in reductions in employment. That research also has found these effects, while small, are especially noticeable among low‑wage workers. This is because payroll taxes owed on behalf of these workers are relatively large compared to their overall wages.

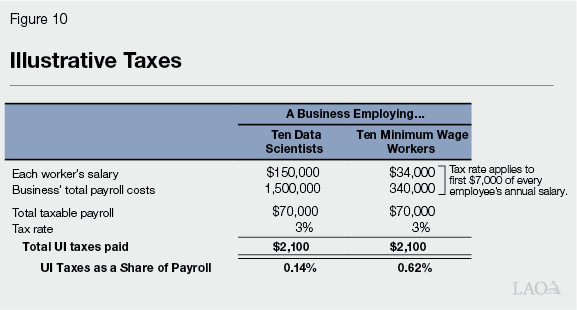

California’s UI Tax Essentially Operates Like an Employment Tax. California’s low taxable wage exacerbates this effect. Employers pay UI taxes on the first $7,000 of each worker’s earnings, but the vast majority of workers earn more than $7,000 in each job annually. As a result, employers pay the same amount in UI taxes on behalf of basically every employee in the state, regardless of how much that employee earns. This creates a once‑annual cost on employers applied to each new hire. As Figure 10 shows with some illustrative numbers, this employment tax raises the cost of adding a new employee to a business and that cost is proportionately higher for a low wage worker than a high wage worker. This likely further exacerbates the already existing negative employment effects of a payroll taxes and means the state’s current tax system could be unnecessarily deterring hiring of lower wage workers.

Recommendations

In Light of Challenges, State’s UI Tax System Needs Full Redesign. A UI tax system should generate sufficient contributions to: (1) cover typical benefit costs each year and (2) build up a reserve during expansions that can be drawn down during recessions when benefit costs exceed contributions. In this section we recommend a path forward to fix the state’s broken UI system and achieve these goals, replacing it with one that is simpler, balanced, and flexible. In addition, while the focus of these recommendations is on solvency, we have also aimed to mitigate each of the three other issues that undermine some of the core objectives of the program.

Recommended Approach. Our recommended approach, as summarized in Figure 11, has four parts: (1) increase the taxable wage base, (2) redesign employer tax rates, (3) rethink employer experience rating, and (4) refinance the federal loan. In putting together these recommendations, we started with the best practice principles outlined in the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) report Guidelines for the Construction and Analysis of State Unemployment Insurance Financing Structures. However, our recommendations are customized to California’s unique UI system. We describe each of our recommendations below.

Figure 11

Recommended Approach to Fix State’s UI System

|

|

|

|

|

UI = Unemployment Insurance. |

Increase the Taxable Wage Base

Recommend Substantially Increasing the Taxable Wage Base. We first recommend the Legislature substantially increase the state’s taxable wage base, which is currently set to the federal minimum of $7,000. Nationwide, the average taxable wage base is around $21,000. States at the top of the distribution include other Western states: Washington ($67,600), Hawaii ($56,700), Oregon ($50,900), and Alaska ($47,100). Substantially raising the state’s taxable wage base would: (1) improve solvency and (2) mitigate the disincentive for businesses to hire low wage workers. However, raising the taxable wage base, even substantially, would not in and of itself be enough to dependably result in solvency, as we discuss in the nearby box. That is, we view raising the taxable wage base as a necessary but not sufficient condition to fixing the state’s broken UI system.

Why Isn’t Raising the Taxable Wage Base Enough to Fix the Financing Problem?

Tax Rates Under Experience Rating Based on Employer Contributions and Benefits. Under the state’s experience rating system, employers’ annual tax rates are based on both how much that employer has contributed to the system and how much in benefits are attributable to its previous employees for all previous years. This means employers’ tax rates are sensitive to two factors: their individual contributions made and benefits paid. That is, employers’ tax rates will increase when benefits paid out to their former employees increase and decline when their contributions to the system increase.

Tax Rate Automatically Declines in Response to Policy Changes That Raise Contributions. A tax rate that decreases in response to higher contributions made and increases in response to higher benefits paid makes intuitive sense throughout an economic cycle. For example, during a recession when unemployment rises, benefit payments rise, and therefore employers’ tax rates also will tend to rise, resulting in the system collecting more money. These relationships are less intuitive, however, in response to policy changes. Specifically, if the Legislature increases the state’s taxable wage base, it will result in higher employer contributions, but this in turn will result in an automatic reduction in employers’ tax rates in the following year. These lower tax rates result in lower contributions, thereby eroding the effect of the initial policy change. Our estimates suggest this offsetting effect is substantial and much larger than previously understood.

Even a Substantial Increase in the Taxable Wage Base Would Not Dependably Result in Solvency. As a result of these factors, increases in contributions that result from increasing the taxable wage base would lessen the fund’s annual operating deficits, but would not dependably result in solvency. For example, even if the state raised the taxable wage base to $50,000, it would continue to routinely rely on federal loans—and the associated federal surcharge—to pay benefits. In our view, changes to tax rates are therefore also necessary.

Recommend Tying Taxable Wage Base to Maximum Weekly Benefit Level. Although there are clear arguments to substantially raise the taxable wage base, it has no single “correct” level. One reasonable approach would be to connect the state’s taxable wage base to the amount of UI benefits a worker can actually receive. Under this idea, an employer would not pay taxes on a worker’s income in excess of the income on which a worker is eligible for wage replacement under UI. In other words, no taxes would be paid on wages that are not covered by UI.

At Current Benefit Levels, Taxable Wage Base Would Correspond to $46,800. Assuming the $450 maximum weekly benefit and a 50 percent wage replacement rate, the state would adopt a taxable wage base of $46,800. Figure 12 shows how the state’s current taxable wage base and our recommendation compare to other states. If the state raised the maximum weekly benefit amount, the corresponding taxable wage base would also need to increase. To that end, we recommend the Legislature change statute to explicitly tie the taxable wage base to maximum weekly benefits going forward. This would mean that any future changes to benefits would automatically trigger an increase to the taxable wage base. Further, we suggest the Legislature consider annually adjusting both the taxable wage base (and maximum weekly benefit amounts) for inflation, so that benefits maintain their purchasing power.

Redesign Employer Tax Rates

Recommend Redesigned Employer Tax Rates. We recommend the state adopt a simple, robust UI tax structure composed of a standard tax rate and a reserve‑building tax rate. In this section, we describe the two tax rates, how they work together, and present the tax rates that would go into effect should these recommendations be adopted. (All of the figures in this section assume a taxable wage base of $46,800.)

Standard Rate to Fund Typical UI Costs. Federal guidelines recommend that states set a standard, base UI tax rate to fund typical UI benefit costs. We recommend the state define this base cost by first calculating the average number of weeks of UI benefits paid to covered employees over time—this accounts for both duration of benefits and take‑up rate. Over the last ten years, the UI program each year has paid an average of 1.4 weeks of benefits per covered employee. (We recommend excluding 2020 from this calculation given the abnormality of UI costs that year.) Then, we multiply this rate by current covered employment and current average weekly benefit amounts to define a “typical benefit cost year.” This is currently about $7 billion.

- Standard Rate Would Be 1.4 Percent. Under current conditions, but assuming our proposed taxable wage base of $46,800, the standard UI tax rate would be 1.4 percent. (To raise the same amount of money under the state’s current taxable wage base of $7,000, the standard tax rate would need to be 5 percent, well above the state’s current tax rate of 3.5 percent.) This rate would be updated annually, adjusting gradually to changes in the state’s long‑term UI benefit costs.

Reserve‑Building Rate to Prepare for Next Recession and Minimize Federal Loans. Following best practices, the state’s UI tax system should also include a temporary state surcharge tax rate, known as the reserve‑building rate, to build up and maintain modest reserves that can be drawn down during recessions when benefits exceed typical contribution levels. Federal officials recommend targeting a reserve amount equal to the average of the three highest benefit cost years over the past two decades. In our recommended approach, we again use the “average number of weeks of UI benefits paid to covered employees” calculation described earlier. To determine the reserve target, we take the average of three highest years of this measure over the last 20 years (excluding 2020) and again update for current employment and benefit levels. This gives a current reserve target of around $15 billion. In other words, the state would need $15 billion in reserves today to cover one year of typical recession‑level UI costs. (The box below describes the rationale behind this recommendation.) Under the federal guidelines, when trust fund reserves are below this target, states should attempt to build this reserve over a three‑ to five‑year period.

- Reserve‑Building Rate Would Be 0.5 Percent. Under current conditions, but assuming our proposed taxable wage base of $46,800 and assuming the state aimed to reach the reserve target in five years, the reserve‑building tax rate today would be 0.5 percent. (To raise the same amount of money under the state’s current taxable wage base of $7,000, the reserve‑building tax rate would need to be an additional 1.9 percent.) Once the state reaches its reserve target, the reserve‑building rate would turn‑off and employers would only pay the standard rate.

A Balanced Approach to Building Reserves

Our recommended approach would help the state build robust reserves ahead of recessions, but does not represent an overly cautious tax system designed to avoid federal loans at all costs. While the state could pursue a more cautious approach, one in which the Unemployment Insurance (UI) program avoids federal loans entirely, doing so would require the state to institute even higher employer payroll taxes. We take a more balanced approach. Should the state adopt our approach, California could run out of reserves during some recessions and require a loan from the federal government to pay for UI benefits. In these cases, the state’s reserve cushion would cover most UI costs, meaning the state would depend only minimally on federal loans. Relative to the current system, our approach would reduce the chances loans are needed and diminish their size. For example, if California had had equivalently sized reserves going into the Great Recession, it still would have required a federal loan, but that loan would have been $5 billion rather than $11 billion. Similarly, had the state entered the pandemic with a similar reserve target ($14 billion in that case), the total federal loan would have reached $9 billion, rather than $20 billion.

Total UI Tax Rate Would Be 1.9 Percent Under Current Conditions. Combining the state’s standard tax rate (1.4 percent) with the temporary reserve building tax rate (0.5 percent) would yield a total UI tax rate of 1.9 percent (see Figure 13). For any worker making more than our proposed taxable wage base ($46,800 per year), their employer would pay around $900 per year under this total UI tax rate. For a worker making less—say, for example, minimum wage—employers would pay around $600 per year under this rate.

Figure 13

Recommended UI Average Tax Rates

Assumes Taxable Wage Base of $46,800

|

Standard rate |

1.4% |

|

Reserve‑building rate |

0.5 |

|

Total |

1.9% |

|

Note: These rates reflect current conditions and would go up or down |

|

|

UI = Unemployment Insurance. |

|

Rethink Employer Experience Rating

Recommend State Transition to an Experience Rating System With Fewer Downsides. As discussed above, California’s current system of experience rating has created unintended problems, including undermining the system’s solvency and depressing take up. We recommend the Legislature transition to a similar method of experience rating that has fewer downsides. This section describes our recommendation for an alternative system.

Recommend Setting Employers’ Tax Rates Based on Increases or Decreases in Employment. The state’s current experience rating system is accounting based: it scores each employer according to how much they have paid into and out of the UI trust fund, requiring EDD to trace every UI claim back to the worker’s former employer and maintain these records in separate “accounts” on behalf of each employer. We recommend the state take a broader approach to experience rating: assign tax rates to employers based on increases or decreases in their employment in recent years. Although no states currently have this precise experience rating model in place, it is similar to the payroll decline system in Alaska, which assigns employers’ tax rates based on whether or not their payroll declined in previous years.

How Our Alternative Would Work. Under our recommended system, the state would assign each employer a rating based on the change in that employer’s number of employees in the previous 12 quarters. (The rating would adjust to account for seasonality.) Employers with the largest increases in employment would pay the lowest tax rates. Employers with the largest employment declines would pay the highest tax rates. Each year, EDD would set tax rates that correspond to each rating to ensure the average tax rate is equal to the standard rate. Experience rating would not affect employers’ reserve‑building rate.

Recommended Improvement Maintains Policy Goal of Experience Rating, but Without Main Downsides. This experience rating method would continue to account, indirectly, for employers’ individual costs to the UI system. Businesses that reduce employment tend to have higher UI usage. Those same businesses also would pay higher taxes. Yet this recommended system does not suffer from the two main downsides of the state’s current experience rating system. Tax rates would not automatically adjust downward in response to higher contributions (thereby undermining solvency efforts). And the new system would remove the incentive for employers to dispute valid claims. This is because, under our experience rating system, an individual UI claim would have no impact on the business’ tax rate. Our alternative system could also be less costly for EDD to administer.

Would This System Make It Harder for EDD to Prevent Fraud? One potential concern with this new approach is that employers might be less likely to cooperate with EDD’s fraud detection efforts via employer verification because they no longer have a strong incentive to participate. While this is a valid concern, employer cooperation and fraud do not appear to be substantial concerns in Alaska, which has a similar experience rating system. In Canada, where the national UI program includes no experience rating, employers nevertheless cooperate with officials to prevent fraudulent claims from going forward. Further, although employer verification plays an important role in fraud detection, that role has been minimized recently due to the changing nature of UI fraud. Today, the most common UI fraud scheme involves identity theft—that is, when someone gains access to a person’s identity information and uses the information to file a claim—rather than workers seeking benefits which they are not eligible to receive. Identity theft must be managed by EDD itself and these efforts will be enhanced by EDDNext, a new information technology project to manage the UI program. That being said, if fraud remains a concern, the Legislature could implement other mechanisms to require or strongly incentivize employers to participate, such as penalty tax rates levied only on employers who refuse to participate in EDD’s fraud detection communications.

Refinance the Federal Loan

Even Under Improved Tax System, State Must Pay Off Federal Loan Before Building Reserves. The currently outstanding federal loan complicates the state’s efforts to fix its broken UI financing system: as long as the federal loan remains outstanding, even an improved tax system would probably not be able to build reserves ahead of the next recession. This is because new contributions under the improved tax system would first go toward paying off the loan rather than building reserves. With this timing issue in mind, we suggest the Legislature consider alternatives to repay the federal loan that allow the state to start building reserves for the next recession immediately. We put forward one approach to this problem here.

Outstanding Loan Stems From Pandemic Shutdown, Suggesting State May Have Some Responsibility for Repaying It. The unique nature of the pandemic stay‑at‑home period raises the question: what role does the state have in sharing the burden of repaying pandemic UI costs? The wave of UI claims in the spring of 2020 did not stem, as UI claims often do, from cyclical business layoffs. Instead, these claims stemmed from an unprecedented effort to minimize the spread of the virus. Together, Californians decided to temporarily prioritize public health at the expense of nearly all in‑person economic activity. One reasonable conclusion from this unique experience is that there is shared responsibility for paying down the outstanding UI loan, which could be achieved through state action.

Recommend a Shared Approach to Refinancing Outstanding Federal Loan. Below, we outline a shared approach that would split the costs of paying off the federal loan between businesses and the taxpayers:

- Revenue Bond Paid Back by Employers. First, the state would issue a revenue bond for approximately $10 billion to be repaid by employers. (A similar strategy has been used by other states—including Colorado, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Texas—which used loans like these after the Great Recession.) We think it’s reasonable to assume such a bond could be issued with a 15‑year maturity at a fixed interest rate of around 5 percent. In addition, to attain the highest rating—and lowest interest rate—the state would need to raise revenue in excess of the minimum debt service (this is called a coverage ratio). Assuming a coverage ratio of 1.25, the total cost to businesses (on top of the tax rates above) would be around $1.2 billion annually (roughly $80 per covered employee). Businesses would make bond payments with a flat surcharge tax rate on top of their UI payroll taxes. As long as the bond is repaid using payroll taxes only, and not state tax revenues more broadly, it would not require voter approval.

- Pooled Money Investment Account (PMIA) Borrowing Paid Back by the General Fund. Second, the state would borrow approximately $10 billion from its cash resources, the PMIA. If this borrowing were repaid over 15 years and the interest rate were set to float with the PMIA yield, the total cost to the General Fund could be around $14 billion, or nearly $1 billion annually. (This is a few billion dollars more, in total, than the General Fund is expected to pay in total interest payments on the federal loan under current law.) The state has used PMIA borrowing for some financial arrangements in the past. While our office has cautioned the Legislature against using PMIA borrowing in some circumstances and borrowing from the PMIA at this magnitude would involve clear downsides, we think it is reasonable to use this option in this case where there is a fiscal benefit to the state and businesses. The state would repay the PMIA borrowing and associated interest from the General Fund. Importantly, this approach is only merited when paired with larger reforms to the system. This recommendation also assumes the state does not have a General Fund surplus to allocate to this purpose. If the budget condition significantly improves before the Legislature takes action on UI reform, we would recommend using surpluses instead of PMIA borrowing.

Although We Propose an Even Split Between Bond and PMIA Borrowing, State Could Move Forward With Different Approach. In this report, we suggest the state evenly split repayment of the federal UI loan between a revenue bond repaid by employers and PMIA borrowing repaid by the General Fund. However, there is no single, correct approach to determining this balance. If this recommendation were adopted, the Legislature could move forward with a different mix that optimally balances trade‑offs at that time.

Shared Approach Would Spread Out Cost of Paying Off Loan and Allow State to Build UI Reserves Immediately. Under our shared approach to refinancing the loan, proceeds from the $10 billion revenue bond and the $10 billion PMIA borrowing would immediately go to paying off the outstanding federal loan. As a result, the federal surcharge tax rates employers are currently paying (and set to pay for many years) would end. The state’s UI trust fund balance would be reset to $0 instead of negative $20 billion. Due to the longer repayment schedule and shared responsibility with the General Fund, businesses would pay a lower surcharge compared to the federal surcharge they would pay under current law. Alongside our proposed UI tax system changes, the state would also begin to immediately build reserves ahead of the next recession instead of spending the next several years slowly paying off the loan before the next recession starts.

Final Considerations

Our Recommendations Would Result in Significant Tax Increases for Employers. In this report, we have recommended the Legislature make a number of changes to the UI financing system. These recommendations, taken together, would have the effect of substantially increasing UI taxes paid by California’s employers. For example, an employer pays about $250 per year in UI taxes per employee making minimum wage. This amount will increase to about $450 in the coming years to repay the federal loans. Under our recommended approach, the same employer would pay about $700 per year in the short term while the state is building a reserve and employers are repaying the revenue bond. (Employer taxes would decline thereafter.) For an employee making any amount more than $46,800, employers’ taxes would increase to around $1,000 per year. (Under our proposed experience rating alternative, actual taxes paid by each individual employer would vary above and below these averages based on their employment track record.)

Our Recommendation That the State Take on New Borrowing Also Has Serious Trade‑Offs. In recognition of the significance of these tax increases, coupled with the unique circumstances of the pandemic, we also recommend the state reduce the burden on businesses of repaying the existing loans. This recommendation requires the state use two new sources of borrowing: a revenue bond, backed by businesses, and borrowing from the PMIA, to be repaid by the General Fund. However, these recommendations have notable risks and trade‑offs and so we do not make them lightly. New PMIA borrowing, in particular, could involve downsides for the state, particularly if the loan is not repaid before the next recession begins as it reduces the state’s cash on hand both in the short and long term. It also limits the capacity of the state to use the account for other purposes in the future.

Magnitude of Tax Increase and New Borrowing an Honest Reflection of UI Program’s Imbalance. We acknowledge that the scope and magnitude of this package of recommendations—including sizeable increases in state payroll taxes as well as new forms of borrowing—are not insignificant. However, they also reflect the deep problems in the existing UI system. These include: (1) the staggeringly large and growing loan from the federal government and (2) the fact that the system is currently running a deficit even during a period of economic expansion. These are significant problems in isolation, let alone in combination. They also are not temporary or short term, rather they are likely to compound in the coming years. Looking ahead, these challenges threaten to erode the UI program’s long‑standing goals to provide some temporary cushion for unemployed workers and their families and to help stabilize the broader economy by supporting consumer spending during economic downturns.

State’s Employers Will Pay Higher UI Costs One Way or Another. Even if the Legislature does not adopt our recommended solutions, employers will soon pay substantially more in UI taxes than they do today. The reason for this is the state’s significant UI loan, which will need to be repaid with an annually escalating federal surcharge that is likely to reach at least 3 percent and could climb as high as 5.4 percent. (This will be levied on top of the state’s tax rate, which we expect to increase to around 5 percent in the coming years under current law.) Compared to the state’s recent approach—wherein artificially low tax rates left the UI trust fund insolvent—these unavoidable higher tax contributions will be jarring cost increases for employers. However, employers will pay higher UI taxes one way or another—either through a streamlined state tax system or through escalating federal charges. Making changes now will allow the Legislature to make strategic choices about how to repay the federal loan, while also replacing the UI financing system with one that is simpler, balanced, and flexible.