Karina Hendren

March 5, 2025

The 2025-26 Budget

Department of Developmental Services

Summary

The Department of Developmental Services (DDS) coordinates a wide variety of services for about 450,000 Californians with intellectual or developmental disabilities or similar conditions. In this brief, we provide some basic background on DDS and a brief summary of the proposed DDS budget (there are no proposed new initiatives), before addressing ongoing oversight and implementation issues. Specifically, we provide background and issues for legislative consideration on the following four issues: (1) the full implementation of service provider rate reform, including quality incentives; (2) the development of the Master Plan for Developmental Services; (3) the department’s ongoing proposed information technology project; and (4) the phase out of an employment program authorized to pay a subminimum wage to individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Background

Lanterman Act Lays Foundation for “Statutory Entitlement.” California’s Lanterman Developmental Disabilities Services Act (Lanterman Act) originally was passed in 1969 and substantially revised in 1977. It amounts to a statutory entitlement to services and supports for individuals ages three and older who have a qualifying developmental disability. Qualifying disabilities include autism, epilepsy, cerebral palsy, intellectual disabilities, and other conditions closely related to intellectual disabilities that require similar treatment, such as a traumatic brain injury. To qualify, an individual must have a disability that began before the age of 18 and is substantial and expected to continue indefinitely. There are no income‑related eligibility criteria. As of December 2024, DDS serves about 380,000 Lanterman‑eligible individuals and another 10,000 children ages zero through four who are provisionally eligible.

California Early Intervention Services Act Ensures Services for Eligible Infants and Toddlers. DDS also provides services via its Early Start program to any infant or toddler under the age of three with a qualifying developmental delay or who are at risk of a developmental disability. There are no income‑related eligibility criteria. As of December 2024, DDS serves about 60,000 infants and toddlers in the Early Start program.

Regional Centers (RCs) Coordinate and Pay for Individuals’ Services. DDS contracts with 21 nonprofit RCs, which coordinate and pay for the direct services provided to “consumers” (the term used in statute). Services are delivered by a large network of private for‑profit and nonprofit providers. In addition to state General Fund and some smaller funding sources, these services are purchased in part through federal funding obtained through the Medicaid Home‑ and Community‑Based Services (HCBS) waiver. The HCBS waiver provides Medicaid funding for eligible individuals to receive services and supports in home‑ and community‑based settings, rather than in institutions.

State Began Implementing a Major Overhaul of Service Provider Rates in 2021‑22. For decades, the state paid DDS direct care staff (also referred to as direct service professionals) according to an outdated and overly complicated rate structure that had not kept up with rising costs over time. In an attempt to modernize and rationalize this structure, the state commissioned a study of service provider costs that was published in January 2020. The 2021‑22 budget began a multiyear, phased‑in implementation of a modernized rate model to pay direct service professionals. The 2022‑23 budget accelerated the phase‑in of this plan, with full implementation of the new rate model scheduled for July 1, 2024. The Governor’s 2024‑25 budget then proposed to delay the final stage of service provider rate reform implementation by one year (to July 1, 2025). The adopted 2024‑25 budget modified this proposal, delaying the final stage of implementation by six months, rather than one year (to January 1, 2025). The final stage of implementation has been in effect since January 1, 2025.

Service Provider Rates Must Include Quality Incentive Structure. Beginning January 1, 2025, statute requires that provider rates consist of two components: (1) a base rate equal to 90 percent of the rate model, and (2) a quality incentive payment equal to 10 percent of the rate model. Providers must satisfy specified performance metrics in order to receive the 10 percent of the rate model reserved for quality incentive payments. Providers can earn the 10 percent portion of the rate model from January 1, 2025 through June 30, 2026 by enrolling in DDS’s new Provider Directory. DDS is in the process of establishing the performance metric(s) that providers will have to satisfy after June 30, 2026 to earn the 10 percent portion of the rate.

2025‑26 Budget Proposal

Overview

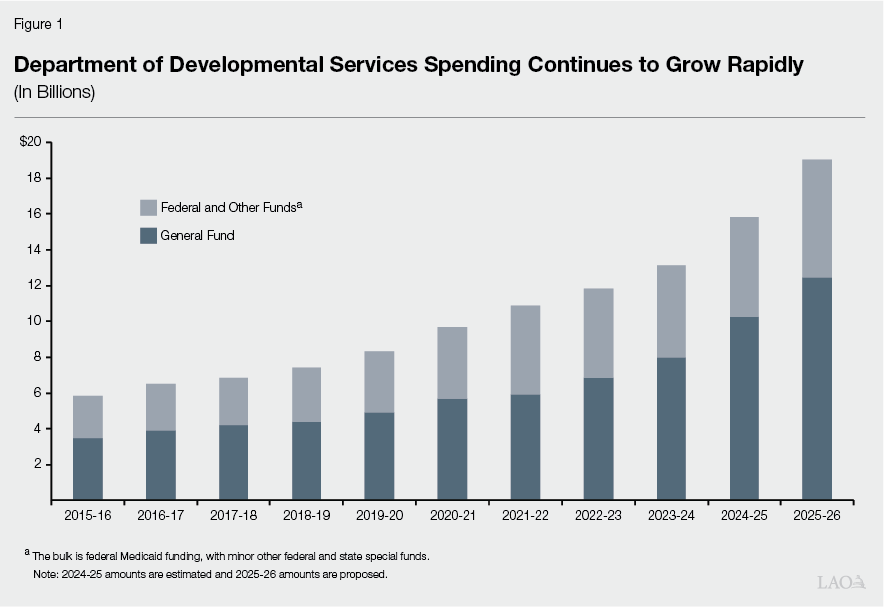

Proposed Budget Reflects Significant Growth. The Governor’s budget proposal includes $19 billion total funds in 2025‑26, up $3.2 billion (20 percent) over the revised 2024‑25 level ($15.8 billion). Of the proposed 2025‑26 total, $12.4 billion is from the General Fund, up $2.2 billion (21 percent) over the revised 2024‑25 level ($10.2 billion General Fund). Significant year‑over‑year growth in DDS spending is a feature of DDS budgets over the past 10 years, as shown in Figure 1.

A portion of the year‑over‑year increase—about $500 million ($307 million General Fund)—reflects the annualization of the first fiscal year of fully funded rate models under rate reform (in 2024‑25, the fully funded rate models were in effect for half a fiscal year). The majority of the increase largely reflects growth in caseload and increases in the utilization of services; available data do not provide sufficient information to differentiate the cost impacts of these factors independently.

The administration projects that it will serve about 500,000 individuals in 2025‑26, an increase of about 40,000 individuals compared to 2024‑25. This caseload projection appears to be reasonable and, according to the administration, reflects growth in the Early Start population due to community outreach efforts.

No Significant New Spending Proposals. Relative to other recent budgets, the Governor’s budget contains very few proposals. The Governor’s budget proposes $8.3 million in ongoing General Fund to implement the Disability Equity, Transparency, and Accountability Act (Chapter 902 of 2024 [AB 1147, Addis]). The proposal does not include any spending solutions beyond those adopted in 2024.

Oversight Issues

In recent years, the DDS system has undergone some significant changes that warrant continued legislative oversight. Below, we highlight four areas of particular interest for the Legislature. For each, we provide general background and updates on the implementation of recent initiatives. We also raise issues for legislative consideration.

Service Provider Rate Reform and the Quality Incentive Program

Background

Rate Reform Intended to Increase Access to Services. The rate study initiated in 2016 was undertaken, in part, because the historical rate structure did not result in funding levels for service providers that kept pace with system growth or supported an adequate supply of providers. (A series of rate freezes and rate reductions—beginning in the early 2000s as budget solutions—meant that the rates had not kept up with rising costs over time.) The funding first allocated in 2021‑22 was intended to support a sufficient supply of quality service providers by raising funding levels for providers via increased rates. Increased provider rates, by extension, were also intended to improve outcomes for consumers by improving the availability and quality of services and supports. These services and supports include residential services, day programs, employment support, transportation, independent and supported living, and personal assistance.

Statute Requires Focus on Quality and Outcomes. Chapter 76 of 2021 (AB 136, Committee on Budget) establishes legislative intent that rate reform implementation should help the developmental services system move from a compliance‑based system to an outcomes‑based system. This change was intended to put greater focus on meeting individual goals and preferences based on person‑centered planning. To achieve this shift, Chapter 76 specifies that service provider payments under rate reform should be linked to consumer outcomes. Specifically, statute provides that the fully‑funded provider rate models will be implemented using two payment components: a base rate equaling 90 percent of the rate model and a quality incentive payment equaling up to 10 percent of the rate model, the latter of which is to be implemented through the quality incentive program. This structure is intended to improve service provider performance, the quality of services, and, ultimately, consumer outcomes. (Prior to the implementation of the quality incentive payment as 10 percent of the total rate, the state began providing some smaller, one‑time quality incentive payments on top of providers’ baseline rates in 2022‑23.) Chapter 76 additionally specifies that performance metrics should evolve from initially being more process‑related, such as meeting deadlines, to eventually include outcome measures, such as whether individual consumers are able to achieve their goals. (The goals of individual consumers can vary widely and span from short to long term. Such goals could include living in an apartment, getting and maintaining a job, and participating in music or art classes.) The metrics and benchmarks for individual outcomes must be established with input from stakeholders through public meetings and 30‑day public comment periods.

Quality Component in Rates Began on January 1, 2025. The final phase of rate reform has been implemented as of January 1, 2025. Beginning on January 1, rate models are fully funded, with the 90 percent (base rate) and 10 percent (quality incentive payment) structure set out in Chapter 76. In last year’s analysis, we provide more context on the time line of rate reform implementation since 2021‑22.

DDS Has Determined Initial Quality Incentive Metrics. For the period spanning from January 1, 2025 through June 30, 2026, providers can earn the quality incentive portion of rate models by enrolling in DDS’s new Provider Directory. The Provider Directory is an online portal that will store and display information about service providers statewide. DDS required providers to complete a data collection survey by October 4, 2024 and then validate the submitted data in the Provider Directory in order to satisfy this performance metric. The department has been engaging in technical assistance with providers to clarify whether they have completed the necessary steps to enroll in the Provider Directory and receive the 10 percent of rates reserved for this metric.

Future Quality Incentive Metrics Under Development. After June 30, 2026, enrollment in the Provider Directory will no longer suffice to qualify for the quality incentive portion of rate models. Chapter 76 requires that quality measures must evolve to include individual‑level outcome measures by the conclusion of the 2025‑26 fiscal year. DDS is still determining how to define these individual‑level outcome measures for 2026‑27. A starting point is the department’s Quality Incentive Program workgroup, which began meeting in 2021 to help select and define outcome measures for one‑time incentive payments available from 2023 through 2026. The workgroup selected the following measures that providers can satisfy to earn one‑time incentive payments through 2026:

- Health checks in specified residential facilities.

- DSP workforce survey participation.

- Competitive integrated employment placements.

- Employment Specialist training completion.

- Timely service delivery for early intervention services.

The department has stated that these one‑time measures will help collect baseline data that will inform the ongoing, individual‑level measures in place starting July 2026. The department also stated that it intends to build upon lessons learned from one‑time incentive payment measures when selecting the ongoing measures to begin in 2026‑27. Additionally, DDS plans to conduct focus groups in 2025 with RCs, providers, consumers, and other stakeholders to collect feedback on the outcomes important to consumers and families. The department also stated that it will collect feedback on ways it could update the one‑time incentive measures.

Assessment

Provider Directory Could Shed Some Light on Access to Services... Previously, DDS lacked a centralized mechanism to store statewide provider information (including service location address, phone number, email address, and organization type). The state’s 21 RCs stored this information separately for their own unique service areas. The creation of the Provider Directory will therefore be a first step in providing a more comprehensive view of the state’s network of providers. Once the information in the Provider Directory is linked to RC service areas, the department could identify potential gaps in service availability throughout the state.

…But Is Only the First Step Towards Measuring Quality. While the Provider Directory has the potential to provide useful information about availability of services by type and region, it alone will not shift the developmental services system from a compliance‑based system to an outcomes‑based system. DDS has acknowledged that enrollment in the Provider Directory is a process‑oriented measure, rather than a measure of individual outcomes. The department has also stated that it intends to build out the Provider Directory’s functions over time to include a portal in which consumers and their families can search for providers based on their location and preferences such as language.

Quality Can Be Challenging to Measure. While quality might be relatively simple to conceptualize, in practice it can be challenging to measure given the expansive nature of an individual’s well‑being and the many outcomes involved. In concept, greater access to services could translate to better outcomes for consumers. However, assessing outcomes can be challenging given the myriad ways that consumers could define their needs and goals across the range of services and supports that they receive. In response to the absence of existing quality measures in the developmental services system, the 2021‑22 budget included $10 million General Fund in one‑time pilot funding for the Person‑Centered Advocacy, Vision, and Education (PAVE) project. This pilot project aims to develop a system to measure the outcomes consumers experience and to evaluate the impact of DDS services on these outcomes. While the pilot shows promise in helping to measure individual outcomes, the development of the PAVE system will not necessarily align with the statutory deadline to utilize individual‑level outcome measures for quality incentive payments by July 1, 2026.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

What Service Gaps Are Identified by Assessing Provider Directory’s Findings? An assessment of the findings from the Provider Directory could shed light on service gaps in the developmental services system statewide. Currently, there is no requirement for DDS to conduct such an assessment and report to the Legislature with its findings. We think this would be valuable information for the Legislature to have in order to prioritize efforts that improve access to services. We therefore recommend that the Legislature direct the department to complete this analysis.

How Does DDS Plan to Use Findings From an Assessment of the Provider Directory? DDS has stated that findings from the Provider Directory might inform its allocation of Community Placement Plan (CPP) and Community Resource Development Plan (CRDP) funding. The CPP and CRDP programs were originally created to support the closure of developmental centers by expanding the services and supports available to help individuals transition into the community. Each year, DDS determines the areas of highest need for community services and supports, then develops guidelines to determine how to allocate CPP and CRDP funding to RCs. RCs submit budget requests to DDS to provide supplemental CPP/CRDP funding on top of their baseline budgets. DDS assesses CPP and CRDP submissions from RCs based on their alignment with the department’s guidelines, including each RC’s need to develop new and innovative service models.

We recommend that the Legislature ask DDS to share details on the way that findings from the Provider Directory could inform the criteria for CPP and CRDP project selection. The Legislature could also establish its priorities and work with the department on determining future CPP and CRDP criteria. This could help ensure that the Provider Directory supports the Legislature’s goal of improving consumer outcomes by expanding access to services. Additionally, we recommend that the Legislature ask DDS to explain its plans for other ways that findings from the Provider Directory will be used to address any barriers to accessing services (aside from CPP and CRDP funding).

Monitor Development of Future Quality Measures. Chapter 76 establishes the Legislature’s interest in using rate reform to improve consumer outcomes, service provider performance, and the quality of services. Given this priority, the Legislature may wish to track the development of individual‑level outcome measures over the next several years. Questions to ask the administration could include: How will the data collected from the one‑time quality incentive payments inform the ongoing quality incentive payments that will be put in place as of 2026? What data are necessary to measure individual‑level outcomes, and how will the department collect this data? How will the department ensure that quality measures do not incentive providers to prioritize “easier to serve” consumers with relatively fewer support needs at the expense of consumers with more significant support needs? What steps will the department take to assist providers that fail to fully satisfy quality metrics?

Master Plan for Developmental Services

Background

Master Plan Will Provide Recommendations to Improve Experiences of Individuals Receiving Developmental Services. The Governor’s 2024‑25 budget proposed that DDS develop a Master Plan for Developmental Services with the intent to improve the experience of individuals and families receiving developmental services. (We addressed this proposal in last year’s analysis.) Subsequently, the Secretary of California Health and Human Services (CalHHS) appointed members to the Master Plan for Developmental Services Committee. These members were assigned to one of five workgroups; each workgroup developed recommendations pursuant to a specific goal for the developmental services system. The administration has stated that these recommendations will be compiled into a draft report to be released no later than March 19, 2025.

Legislature Codified the Master Plan for Developmental Services as a Cross‑Agency Effort Focused on Equity. Budget‑related legislation codified the Legislature’s findings and declarations establishing the foundation for the Master Plan (Chapter 47 of 2024 [AB 162, Committee on Budget]). Importantly, Chapter 47 acknowledges that consumers and their families rely on services provided through multiple state and local entities, including the State Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), the California Department of Aging, the California Department of Social Services, the Department of Rehabilitation (DOR), and the State Department of Education. Because individuals receive services from these various entities, Chapter 47 states that CalHHS should work across state agencies and departments to identify policies, efficiencies, and strategies necessary to implement the Master Plan. Additionally, Chapter 47 states the Legislature’s intent that the Master Plan should serve all consumers and their families regardless of their language spoken, demographic group, geographic region, or socioeconomic status. Finally, the legislation establishes that any funding needed to support program enhancements proposed in the Master Plan is subject to an appropriation by the Legislature.

Assessment and Issues for Legislative Consideration

Has the Master Plan Development Process Reflected Legislative Intent? We recommend that the Legislature ask the administration to provide detailed information on the extent to which the development of the Master Plan has aligned with legislative intent as set out in the provisions of Chapter 47. The Master Plan process as envisioned by Chapter 47 is a multi‑departmental, multi‑agency effort, with CalHHS serving in a key coordinating and leadership role. Questions to ask the administration could include: How did CalHHS exercise its oversight authority to lead the Master Plan development process? What specific steps has CalHHS taken to fulfill its cross‑departmental, cross‑agency coordination role? Which state agencies and departments have been directly involved in the development of the Master Plan, and what have their unique contributions been? To what extent have Master Plan committee members been given the opportunity to receive technical assistance from multiple state departments when developing recommendations? How has CalHHS ensured that Master Plan committee members have access to input provided by a broad crossection of consumers and their families, given the intent of Chapter 47 that all consumers and their families be served equitably?

What Is the Administration’s Vision for the Master Plan Going Forward? Given that the Master Plan development process set out in Chapter 47 prioritizes community involvement and public feedback, the final product submitted to the Legislature and Governor in March will not be (and was not intended to be) a plan of action from the administration. The administration has stated that the final product will be solely comprised of recommendations generated by the community. While these recommendations form a key starting point, the Master Plan cannot be put into action without initiative from the administration. A critical missing piece, therefore, is a roadmap for how to translate the community’s recommendations into a workable set of policy and budget proposals for legislative consideration.

The administration has stated that it will consider the Master Plan’s recommendations in future policy and fiscal planning. The details of this process, however, have not been shared publicly. For example, the administration has not yet provided details on how it plans to prioritize the Master Plan’s recommendations when developing near‑term versus long‑term proposals. In order to understand the full scope of the Master Plan and its implications for the developmental services system, the Legislature will want to request this information from the administration.

For budget planning purposes and in light of projected budget deficits through 2028‑29, the Legislature will need to understand the potential policy and fiscal impacts of any proposals resulting from Master Plan. To this end, the Legislature could ask the administration how it plans to prioritize the Master Plan’s recommendations when developing future budget and policy proposals, as well as the administration’s plans for the timing for these proposals (for example, will any proposals be submitted at May Revision in 2025?). Questions to ask the administration could include: How does the administration plan to weigh recommendations from the Master Plan that might require new spending in comparison to DDS’s existing spending commitments? How will the administration differentiate recommendations that could be implemented in the near term compared to recommendations that will take longer to implement? How will the administration reconcile the community’s recommendations with its own priorities?

Legislature Could Delineate a Process on How to Move Forward. At the time this analysis was prepared, the administration has not clearly articulated a roadmap to implement the community’s recommendations that will be presented in the Master Plan. This presents an opportunity for the Legislature to help establish next steps after the Master Plan is published. This will give the Legislature a chance to provide direction before the administration potentially submits future budget proposals resulting from the Master Plan. To this end, we recommend that the Legislature consider introducing trailer bill legislation, similar to that introduced in Chapter 47, to ensure that the Master Plan implementation process reflects legislative priorities. This legislation could include requirements for additional analysis and reporting to the Legislature on topics such as the feasibility or the costs and benefits of the Master Plan’s recommendations.

Ongoing Proposed Information Technology (IT) Project

Background

DDS Recently Received Funding for Proposed IT Project to Replace Outdated Case Management and Accounting Systems. The department has recently started a multiyear effort to modernize the IT systems used in California’s 21 RCs. RCs currently use separate IT systems for accounting and case management. Both of these systems are outdated and rely on technology from the 1980s, making it challenging and time‑consuming for RCs to perform their responsibilities. The case management systems are not consistent across the 21 RCs, as some RCs have adopted various “workarounds” to overcome shortcomings of the legacy system. Further, the existing systems do not allow consumers or their families to access their records electronically. To address these issues, DDS proposed an IT project for a modern, integrated case and financial management system that will be consistent across regional centers and allow consumers to view their own records. The department has received the following funding for this IT project planning since 2021‑22:

- 2021‑22 Spending Plan. California’s Home and Community‑Based Services Spending Plan, using enhanced federal funding from the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act, allocated $6 million in one‑time federal funding to help modernize DDS’s IT systems. Specifically, the funding supported the initial planning process to update the regional center fiscal system and implement a statewide Consumer Electronic Records Management System. This funding was available through 2023‑24.

- 2023‑24 Spending Plan. The spending plan provided $12.7 million ($12.2 million General Fund) one‑time funding to support continued planning efforts for the IT project. The budget package also included supplemental report language requiring the department to provide quarterly written updates to the Legislature on several project details, including project development, stakeholder engagement, and any identified project risks.

- 2024‑25 Spending Plan. The spending plan provided $1 million General Fund and authorized up to $5 million in provisional authority for continued IT project planning, pending the potential approval of federal funding. We note that the department also canceled its Reimbursement System Project, a separate IT project that first received funding in 2019‑20. Please see the nearby box for more information on the Reimbursement System Project.

Reimbursement System Project

In 2024, Department of Developmental Services Canceled Reimbursement System Project Due to Problems With Contractor. In 2019‑20, the Department of Developmental Services (DDS) received $12 million ($11.8 million General Fund) in each of 2020‑21 and 2021‑22 to develop the Reimbursement System Project. This information technology (IT) project was intended to improve DDS’s ability to process and claim federal reimbursements for its Medicaid waiver‑eligible services, as the “legacy” IT system used to claim federal reimbursements was not meeting the department’s programmatic needs. In 2024, the department requested that the California Department of Technology (CDT) cancel the project because the chosen contractor was not able to deliver the agreed‑upon product, despite the use of correction plans and remediation efforts. The project ended on June 30, 2024 with the expiration of the contract. DDS has stated that it is evaluating whether to incorporate parts of the canceled Reimbursement System Project into its ongoing IT project for regional centers’ case management and accounting systems.

Department Has Submitted Two IT Project Approval Lifecycle (PAL) Documents to Date. DDS has completed the first two stages in the California Department of Technology’s (CDT’s) PAL process (the state’s IT project approval process): the Stage 1 Business Analysis and Stage 2 Alternatives Analysis. Stage 1 of the PAL process requires the department to justify the project by documenting existing barriers to operations and service delivery, opportunities to address identified barriers, and desired outcomes from the project. Stage 1 additionally requires the department to identify stakeholders affected by the project and describe how these stakeholders will be involved in the planning process. Stage 2 requires the department to conduct market research to determine which IT solution would be able to meet the project’s desired outcomes. In this step, the department must also provide detailed project plans, including a financial analysis for the project that compares the cost of maintaining the existing system with the recommended IT solution cost. Taken together, planning documents developed during the PAL process give the Legislature information necessary to evaluate the merits of the proposed IT project.

Although Some Stakeholder Engagement Has Already Taken Place, Department Recently Announced Plans to Solicit More Input in 2025. DDS has stated that, although it has conducted some discussions on desired outcomes for the project (pursuant to Stage 1 of the PAL process), the conversations to date have not adequately captured the range of feedback from all stakeholders (including department staff, RC staff, and families served by the department). The department therefore intends to reopen these conversations in 2025. DDS stated that it already began this effort with internal meetings in January, and that it plans to solicit feedback from regional centers and consumers over the first several months of 2025. As part of this approach, the department also renamed the project from the “Uniform Fiscal System Modernization” and the “Consumer Electronic Records Management System” to the “Life Outcomes Improvement System (LOIS)”. (According to the department, LOIS pays tribute to Lois Curtis, one of the plaintiffs in the Olmstead v. L.C. Supreme Court case that established the right for people with disabilities to live in the least restrictive environment appropriate to meet their needs.)

Separate From State PAL Process, Department Also Seeking Enhanced Federal Funding. In its original PAL Stage 2 document, DDS estimated that this IT project will cost about $135 million to $180 million in total funds (excluding future maintenance and operations costs). In addition to state funding for this project, DDS is requesting enhanced funding from the federal government through the Advanced Planning Document process. This process allows the state to request a 90 percent match in federal funding (rather than California’s standard 50 percent match) to develop IT systems that enable the state to more efficiently administer Medicaid benefits. DDS is eligible to request this support because nearly all home‑ and community‑based services for DDS consumers receive federal Medicaid matching funds. DDS has stated that it started this process by working with DHCS to create a Planning Advanced Planning Document (PAPD). The PAPD provides funding for planning activities before the project is implemented. According to federal regulations, a state’s PAPD submission must clearly state the purpose and objectives of the IT project, as well as identify the state’s planning activities and resource needs.

Assessment and Issues for Legislative Consideration

Legislative Oversight of IT Project Can Help Ensure Success of Important Project. We recommend that the Legislature exercise its oversight authority to help ensure that this multiyear IT project can be successfully completed on time and within budget. The IT system will directly impact a vulnerable population, which means there is a heightened level of risk associated with the project. The new IT system will eventually help facilitate the use of quality incentive payments as part of rate reform implementation, thereby helping the developmental services system as a whole to move towards individual‑level outcomes. Additionally, the cancelation of the Reimbursement System Project in 2024 demonstrates the challenges that can occur in complex IT projects and the level of time and care needed to help these complex projects succeed. For these reasons, legislative oversight throughout the planning, development, and implementation of this project will be critical.

Ensure Department’s PAL Documents Reflect Outcomes From 2025 Stakeholder Outreach Efforts. The department’s efforts to reengage the community in 2025 likely have merit, as these efforts will help ensure that stakeholders can provide input on the goals and outcomes of the IT project. By reopening these conversations, however, it is likely that the department’s desired outcomes for the project will end up differing from what has already been provided in the existing PAL Stage 1 and Stage 2 documents. The department has stated that it plans to submit its findings from the 2025 stakeholder outreach and a revised fiscal estimate to CDT and the Department of Finance for approval.

We recommend that the Legislature clarify in budget hearings whether the department intends to update its PAL documents (which the Legislature receives) as part of this process. To effectively perform legislative oversight of the project, the Legislature must receive project plans that reflect the most recent actions taken by the department to plan, develop, and implement a project. Without updated plans, the Legislature cannot determine whether or not the needs of the department, RCs, and the community are being met by the project. Specifically, in budget hearings, the Legislature could clarify whether the department plans to revise its Stage 1 document to incorporate its plans for stakeholder outreach in 2025. Additionally, the Legislature could clarify whether the department plans to resubmit its Stage 2 document, which would include market research on the best IT solution to meet the additional needs identified by stakeholders and an updated cost estimate.

Consider Funding Options for 2025‑26 and Outyears Based on Receipt of Additional Supporting Documentation. We recommend that the Legislature engage with the administration to determine whether DDS’s stakeholder engagement efforts for this project in 2025 will require reappropriation of previously approved funds. Given the potential change in the project’s direction based on these efforts, this decision must involve the Legislature, rather than being decided solely by the administration. To help inform its consideration of a potential reappropriation of funds, the Legislature could consider requesting a detailed expenditure plan for the funding that was already appropriated for PAL Stages 1 and 2 through provisional budget bill language. As part of this exercise, the Legislature could ask the department to provide detail on the type of stakeholder feedback it plans to solicit in 2025 (and how this input might differ from the feedback the department already collected in PAL Stage 1). This expenditure plan would help the Legislature determine whether the proposed activities funded by the reappropriation adequately support the new direction of the project. Any additional funding for the remaining steps in the PAL process would be contingent upon, at a minimum, the Legislature’s review of this plan.

Ensure Department’s Submission for Federal Funding Aligns With State Documentation. As of January 2025, the department stated that it was aiming to submit its PAPD to the United States Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in early 2025. (These submissions are not publicly available.) Once the PAPD is submitted, CMS typically provides a written decision to the state within 60 days. We recommend that the Legislature ask the department to provide a status update on the PAPD process in budget hearings. Much of the information required in the PAPD submission overlaps with the information required in the PAL Stages 1 and 2 documents. As a result, any updates to the state’s PAL Stages 1 and 2 documents should be mirrored in the federal PAPD submission to ensure consistency. This consistency will help avoid any potential delays or reductions in the receipt of enhanced federal funding.

Employment of DDS Consumers and Subminimum Wage Phase‑Out

Background

California Adopted an “Employment First” Policy for DDS Consumers in 2013. Chapter 667 of 2013 (AB 1041, Chesbro) created California’s employment first policy, which makes competitive, integrated employment (CIE) the highest priority for working age individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities, regardless of the severity of their disability. (CIE refers to employment at a workplace mostly employing individuals without disabilities and for prevailing market wages.) This was followed by federal action in 2014 when Congress passed the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act, which promotes CIE and increased training and supports for individuals with disabilities.

DDS Oversees Multiple Employment Programs for Consumers. DDS provides a variety of services to help consumers find and maintain employment if they desire to work. Supported employment services provide job coaching to consumers (in both group and individual placements) who typically are working in a community setting (for example, a hotel or a grocery store). Paid internships allow DDS to pay the wages of and provide job coaches to consumers (either individually or in groups) placed short‑term in a community employment setting. Tailored day services help consumers develop skills for employment through customized training. Work activity programs are sometimes held in “sheltered workshops,” which are work areas specifically employing only individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities. In other cases, work activity programs may take consumers out to community workplaces to work together as a group.

Some DDS Consumers Previously Participated in Federal Subminimum Wage Program. The Fair Labor Standards Act, which establishes the federal minimum wage, creates a process (known as the 14(c) certification process) for certifying some employers to pay employees with intellectual and developmental disabilities less than the minimum wage. Most subminimum wage employers in California were nonprofit organizations that also offered a broad suite of other services, including other employment supports and day programs (which provide education, community engagement, and entertainment during the day for consumers who are not regularly employed). Many subminimum wage employers operated work activity programs.

In 2021, State Committed to Ending Subminimum Wage Employment by 2025. Chapter 339 of 2021 (SB 639, Durazo) calls for the transition of employees working under subminimum wage into CIE by January 2025. The bill required the State Council on Developmental Disabilities (SCDD) to establish a multiyear plan for phasing out the use of 14(c) certificates in California. By the end of the multiyear plan (once 14(c) certificates are phased out), any DDS consumers who are employed must be paid at least minimum wage. When SB 639 was enacted, the number of individuals receiving subminimum wage was not clearly documented due to data limitations. As of January 2023, it was estimated that at least 4,000 people with disabilities (many of whom were DDS consumers) were employed in subminimum wage jobs in fiscal year 2021‑22.

The SCDD’s multiyear plan was published in January 2023. Among other recommendations, SCDD’s plan called for the state to increase state funding for job developers (those who identify and help develop employment opportunities for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities) and job coaches, fund counseling to help consumers understand how employment will or will not affect the benefits they receive, and provide more transportation options for individuals seeking employment at competitive wages.

As of 2025, All Consumers Have Transitioned Out of Subminimum Wage Employment… DDS has been systematically tracking the number of remaining consumers employed in subminimum wage settings since July 2023. The department estimated that there were about 2,900 consumers employed and earning less than minimum wage. The department has worked with RCs to track these individuals and help them transition out of subminimum wage. As of December 2024, the department reports that there are no longer any consumers earning less than minimum wage.

…Yet About 10 Percent of Consumers Have Not Found Other RC‑Supported Activities in Their Place. Of the consumers previously employed in subminimum wage jobs, about 270 individuals have not yet engaged in another RC‑supported service in place of employment. Remaining consumers are engaged in a variety of other activities (with some individuals participating in multiple activities). Many are working and earning at least minimum wage, with about 75 individuals now engaged in CIE, about 700 employed in group settings, about 240 employed in work activity programs, and about 70 participating in paid internships. For these individuals who are employed, the department is not able to provide details on the average number of hours worked. Many other consumers previously employed in subminimum wage jobs are not currently working. About 850 consumers are receiving a type of day program service. Another 600 are participating in a “Community Integration Training Program,” which is a service that can be adapted for a variety of purposes. Another 150 consumers have retired, moved, or no longer have a case with a RC. About 20 individuals are receiving training or support towards employment.

Department Recently Created New Service for Consumers Leaving Subminimum Wage Employment or Transitioning From Secondary Education. After SB 639 was enacted, the 2022‑23 spending plan allocated $8.4 million ($5.1 million General Fund) one‑time available over three years for DDS to establish a service model focused on individuals transitioning out of subminimum wage or recently graduating from high school. This funding resulted in a new service called Coordinated Career Pathways (CCP), which aims to help individuals achieve CIE after exiting subminimum wage employment or completing secondary education. CCP includes two new service options: a Career Pathway Navigator and a Customized Employment Specialist. The department states that these services are time‑limited to 18 months but can be extended to a maximum of 24 months.

Assessment and Issues for Legislative Consideration

While the administration has not proposed any changes to its employment programs in the budget year, we provide the following topics for legislative consideration given the recent phaseout of subminimum wage. It is important to acknowledge that, as SCDD notes in its January 2023 transition plan, centralized statewide leadership is needed for CIE to succeed, and meaningful change is not the responsibility of one agency alone. The following discussion is limited to issues that fall within DDS’s scope of responsibility.

Has the Implementation of SB 639 Reflected Legislative Intent? Given that the deadline established in SB 639 only recently passed, it would be unrealistic to expect that every consumer previously earning subminimum wage would already be fully transitioned to CIE. Nonetheless, it is important to acknowledge that placing DDS consumers who desire to work in CIE remains the ultimate goal of SB 639. We recommend that the Legislature ask DDS to provide regular updates on the status of individuals who recently transitioned out of subminimum wage employment and whether they have been placed in CIE. A particular focus is warranted on the 270 consumers who have not found alternative RC‑supported activities as of January 2025. DDS, SCDD, and DOR have stated that they remain committed to finding services for these individuals. In addition to administrative efforts, the Legislature could use its oversight authority to track whether these individuals have found alternative activities.

Is the New CCP Service Capable of Effectively Serving Consumers Statewide? While the new CCP service has potential, it is still too early to assess its effectiveness in helping individuals obtain CIE. DDS stated that, as of January 2025, about 25 providers have been approved to provide CCP. A small number of consumers have recently started to receive the service. The department said that it has needed time to set up this new service, and that it intends to survey RCs on the service in the spring of 2025.

DDS noted that, in order to offer this service, providers must have skilled staff capable of offering customized employment approaches beyond traditional job coaching. In light of this required level of skill, some RCs and providers have expressed interest in receiving technical assistance to better understand and implement CCP. The Legislature could ask DDS whether it would be able to offer this type of technical assistance to interested RCs and providers so that they can take full advantage of the new service’s potential. Expanding the availability of this service could potentially help consumers transition from day programs to employment, which in turn would further progress towards the intent of SB 639.