Michael Alferes

March 25, 2025

Overview of K‑12 Career Technical Education

- Introduction

- Overview of K‑12 CTE

- CTE Funding

- CTE Data and Accountability

- Issues for Legislative Consideration

- Conclusion

Summary

Schools Provide Career Technical Education (CTE) Programs for Students. CTE courses generally are designed to teach technical skills that can lead to further postsecondary education or employment, and to help produce skilled workers to meet industry needs. Local governing boards determine the courses that they offer students. The specific offerings vary based on several factors, such as student interest and local workforce needs.

Most Targeted CTE Funding Comes From the State. The primary source of funding for schools is the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). Schools use LCFF to pay for most of their general operating expenses. This typically includes costs associated with CTE programs. The state also provides roughly $500 million in ongoing funding specifically for CTE, primarily from two competitive grant programs. Additionally, in recent years, the state has provided almost $1 billion in total one‑time funding to support a variety of CTE initiatives.

State Collects Various Data on CTE Programs. The state annually collects a variety of CTE‑related information from school districts, county offices of education (COEs), and charter schools. This includes course offerings and course completion. These data show a significant increase in the share of CTE courses that fulfill the college preparatory coursework required to be eligible for freshman admission at the state’s public universities. As part of the state’s school accountability system, the state tracks performance on the College and Career Indicator, which combines information about a student’s course completion and test scores to determine whether a student is prepared for college and career. Additionally, all schools operating CTE programs are required to submit postsecondary status data for students who complete CTE pathways.

Issues for the Legislature to Consider. We raise three questions for the Legislature to consider in evaluating its approach to K‑12 CTE issues.

- How Should the Legislature Monitor Progress on CTE‑Related Goals? To the extent the Legislature wants to more closely monitor specific CTE outcomes, it could require that more detailed information be publicly reported. It also could require the collection of additional data that would help it monitor progress on key objectives. For example, the state could require district‑level reporting of data for students who complete CTE pathways.

- Is Categorical Funding an Effective Way to Achieve the Legislature’s Key Goals? Unlike other areas in K‑12 education, the state has largely retained its categorical funding structure for CTE after the enactment of LCFF. The Legislature may want to consider whether this approach has been effective in helping the state make progress on its key education goals.

- What Are the Benefits of Having Multiple Categorical Programs? If the Legislature wants to maintain CTE categorical funding, it may want to consider whether having multiple CTE categorical programs is an effective way to make progress on key CTE goals and whether modifications to the structure of these programs could help achieve these goals more effectively.

Introduction

Schools offer a variety of CTE programming that prepares students for postsecondary education and careers. Over the past several years, the Legislature has shown significant interest in these CTE programs. For example, the Legislature has introduced bills that would change the structure of the programs, conducted oversight hearings, and allocated significant amounts of ongoing and one‑time funding.

Furthermore, in August 2023, the Governor issued an executive order calling for various education and workforce agencies to convene and develop a Master Plan on Career Education. The forthcoming Master Plan is intended, in part, to identify opportunities for better alignment and coordination across programs. This brief is intended to give policymakers a high‑level overview of the state’s role in supporting K‑12 CTE programs and raise some key issues for consideration. (CTE programs that serve adults are not the focus of this report.) The brief is organized into the following four sections: (1) an overview of California’s K‑12 CTE programs, (2) CTE funding, (3) data and accountability related to CTE, and (4) issues for legislative consideration.

Overview of K‑12 CTE

Schools Required to Offer CTE Courses for Students in Grades 7‑12. State law sets forth requirements for the course of study that schools must offer to students. For students in grades 7‑12, schools must offer courses in a variety of subjects, including English, math, social sciences, science, world languages, physical education, visual and performing arts, applied arts, and CTE. According to state law, CTE courses are intended to help students attain employment skills that address state or local workforce needs in business or industry.

CTE Courses Help Students Meet High School Graduation Requirements. The state sets minimum course completion requirements in order for students to graduate from public high schools. As part of these requirements, students must complete one year‑long course in visual or performing arts, world language, or CTE. In addition, districts are required to offer a course of study that fulfills the college preparatory coursework required to be eligible for freshman admission at the University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) systems (known as the “A‑G” requirements). Although completing CTE coursework is not an A‑G requirement, some CTE courses may be designed to fulfill the A‑G requirements. For example, a CTE course in engineering could be designed to meet the A‑G science requirement.

K‑12 CTE Has Various Objectives. CTE courses generally are designed to teach technical skills that can lead to further postsecondary education or employment, and to help produce skilled workers to meet industry needs. In practice, schools may have various other objectives when offering CTE courses. For example, CTE programs may promote student engagement by teaching academic subjects in a hands‑on way; teach soft skills, such as teamwork and communication, that can better prepare students for additional education or the workplace; or provide an opportunity for students to gain exposure to different types of careers.

CTE Organized Around 15 Industry Sectors. The California Department of Education (CDE) defines CTE as sequenced coursework in one of 15 industry sectors. As Figure 1 shows, over 59,000 courses were taught across these industries in 2023‑24. The largest number of courses were in Arts, Media, and Entertainment; Health Science and Medical Technology; and Agriculture and Natural Resources. CDE has developed curriculum standards for each of the sectors. The CTE curriculum standards are aligned with the state’s academic content standards in English language arts, math, and science to prepare students for postsecondary education and employment. For example, the model curriculum for courses in architectural design is structured to prepare students to write informative texts in a way that is aligned with the state’s writing standards in English language arts.

Figure 1

Courses Taught by CTE Industry Sector

Total Courses Statewide, 2023‑24

|

Industry Sector |

Number |

Percent |

|

Agriculture and Natural Resources |

6,661 |

11% |

|

Arts, Media, and Entertainment |

13,530 |

23 |

|

Building and Construction Trades |

2,790 |

5 |

|

Business and Finance |

3,010 |

5 |

|

Education, Child Development, and Family Services |

2,190 |

4 |

|

Energy and Utilities |

279 |

— |

|

Engineering and Architecture |

2,755 |

5 |

|

Fashion and Interior Design |

889 |

2 |

|

Health Science and Medical Technology |

7,373 |

12 |

|

Hospitality, Tourism, and Recreation |

4,041 |

7 |

|

Information and Communication Technologies |

4,251 |

7 |

|

Manufacturing and Product Development |

1,640 |

3 |

|

Marketing, Sales, and Service |

1,353 |

2 |

|

Multiple Industry Sectors |

3,721 |

6 |

|

Public Services |

2,251 |

4 |

|

Transportation |

2,373 |

4 |

|

Totals |

59,107 |

100% |

|

CTE = career technical education. |

||

CTE Courses Are Designed Around Career Pathways. CDE has adopted pathway standards for 58 career pathways that fall under the 15 industry sectors. The pathway standards are each organized around a career focus and a sequence of learning to best meet the local demands of business and industry. These pathways also can serve as a way to transition into higher education. Each industry sector has between three and seven different pathways. For example, the business and finance sector has three recognized career pathways: business management, financial services, and international business. Students in the financial services career pathway will take a sequence of courses that can translate to employment after graduation in jobs such as bookkeeper or accounting clerk. Students can also further pursue their pathway by completing additional postsecondary coursework. With additional coursework at a community college, students can obtain a certificate or associate’s degree that would prepare them for jobs such as auditing clerk or associate financial advisor. With a bachelor’s degree, students would be prepared for jobs such as a financial analyst or could pursue a certified public accountant license.

CTE Course Offerings Vary Locally. While the state sets specific requirements associated with CTE and develops standards around career pathways, most other details related to CTE are determined locally. For example, local governing boards determine the courses and pathways that they offer students. The specific offerings may be based on a variety of factors, such as student interest and local workforce needs. Local governing boards may also choose to partner with other agencies to jointly offer CTE courses to their students. For example, some school districts partner with neighboring districts and their COE to offer CTE courses to students in the participating districts and COE. In some cases, these regional partnerships are administered jointly through regional occupational centers and programs (ROCPs). These regional partnerships can provide greater economies of scale that give students access to a broader set of courses.

CTE Offerings May Also Vary Based on Program Goals. CTE course offerings can also vary across the state based on the specific objectives local governing boards would like to prioritize. Over the past decade, the state has increasingly focused on ensuring that students have both college and career options upon graduating from high school. As a result, many CTE courses have become integrated into high school students’ regular instructional curriculum. For example, a college‑bound student may take high school CTE courses such as engineering and graphic arts to satisfy A‑G course requirements. To teach core academic subjects in a more applied manner, students may learn math and science as part of a health occupations pathway. Additionally, CTE programs in middle school and earlier grades of high school may focus more on career exploration, while the later years of high school may focus more on providing more specialized instruction in a specific career pathway.

Students Can Take College‑Level CTE Courses Through Dual Enrollment. Dual enrollment courses are college‑level classes that may count toward both a high school diploma and a college degree. By graduating high school having already earned college credits, students can save money and accelerate progress toward a postsecondary degree or certificate. Some dual enrollment programs have a specific CTE focus as part of a career pathway that leads to a certificate or associate’s degree at the community college. Dual enrollment has various models. California’s two most widely used models are traditional dual enrollment and College and Career Access Pathways (CCAP). Traditional dual enrollment typically consists of individual high school students taking college‑level courses on a community college campus. CCAP, on the other hand, allows cohorts of high school students to take college‑level classes on a high school campus. (CCAP was authorized by Chapter 618 of 2015 [AB 288, Holden].)

CTE Funding

In this section, we first provide an overview of state funding available for CTE. We then describe the various types of state funding specifically targeted for CTE, including the two major ongoing programs, smaller ongoing programs, and recent one‑time grants. Finally, we provide a brief summary of federal funding. Unless otherwise noted, all state funding is Proposition 98 General Fund.

Overview of Funding

LCFF Covers Core K‑12 Instruction Costs. LCFF is the primary source of funding for school districts and charter schools. The formula provides a base amount per student that varies by grade span, plus additional funding for low‑income students, English learners, and foster youth. LCFF base funding can be used for any educational purpose. The state requires school districts and charter schools to develop local plans for how they will use funding to best serve the needs of their students. School districts and charter schools pay for most of their general operating expenses—such as employee salaries and benefits, supplies, and student services—using LCFF. This typically includes costs associated with CTE programs. For 2024‑25, the state is estimated to spend more than $79 billion on LCFF. The high school base LCFF funding rate per student is $12,144 in 2024‑25. This includes a 2.6 percent adjustment that was intended to acknowledge the cost of CTE programs when LCFF was enacted. (See the nearby box for historical information about how CTE funding changed in the first few years of LCFF.) The state also provides additional funding for specific programs, such as CTE, special education, and before and after school programs.

Evolution of State Career Technical Education (CTE) Funding

Largest High School CTE Categorical Program Folded Into Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). For decades, the state funded several high school CTE categorical programs, each with their own allocation formulas, spending rules, and reporting requirements. The largest CTE categorical program was Regional Occupational Centers and Programs (ROCP), which provided $400 million annually to school districts and county offices of education (COEs) for regional CTE training to adults and high school students age 16 and older. As part of the adoption of LCFF in 2013‑14, ROCP funding was folded into LCFF. In the first two years of LCFF implementation, however, school districts and COEs were required to spend no less than they did in 2012‑13 on ROCPs. Several other smaller CTE categorical programs were not included in LCFF and retained their own spending and reporting requirements.

LCFF High School Rates Included Adjustment Related to CTE. Under LCFF, the state set a base per‑student rate for high schools that is notably higher than the rates set for the lower grades. This higher rate reflects the more specialized curriculum that high schools provide. On top of the already higher base rate for high schools, LCFF includes an additional 2.6 percent increase to the high school rate to reflect the higher costs associated with operating CTE programs. (CTE courses can have higher equipment and materials costs compared with core academic courses.) At the time LCFF was enacted, the value of this adjustment reflected the total statewide amount spent on ROCP (roughly $400 million). The state did not set any specific spending requirements on the CTE adjustment.

State Provided Three Years of Temporary CTE Funding. In 2015‑16, the state established the CTE Incentive Grant (CTEIG) to fund K‑12 CTE programs for a period of three years. The expressed intent of CTEIG was to help districts cover the costs of CTE as the state was implementing LCFF. The state allocated a total of $900 million to the program over the course of three years, with funding diminishing over the period ($400 million in 2015‑16, $300 million in 2016‑17, and $200 million in 2017‑18). At the same time, the local match requirements were increased each year. Funding was provided through competitive grants.

In 2018‑19, State Established Two Ongoing CTE Programs. The 2018‑19 budget package included $150 million to establish CTEIG as an ongoing program. In addition, the budget allocated $150 million to the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s office to establish a K‑12 component of the California Community College Strong Workforce Program. The program requirements have largely remained unchanged since 2018‑19. In 2021‑22, the state increased annual ongoing funding for CTEIG from $150 million to $300 million.

State Has Several K‑12 Programs Focused on CTE. As Figure 2 shows, the state provides almost $500 million in ongoing funding for six K‑12 CTE programs. The state also has provided one‑time funding for a variety of CTE initiatives. In the rest of this section, we describe these ongoing and one‑time programs in more detail.

Figure 2

State’s Ongoing K‑12 Career

Technical Education (CTE) Programs

2024‑25 (In Millions)

|

Program |

Funding |

|

Career Technical Education Incentive Grant |

$300 |

|

K‑12 Strong Workforce Program |

150 |

|

California Partnership Academies |

21 |

|

Career Technical Education Initiative |

15 |

|

Agricultural CTE Incentive Grant |

6 |

|

Specialized Secondary Programs |

5 |

|

Total |

$497 |

Major Ongoing CTE Programs

State Provides Most CTE Funding Through Two Programs. The vast majority of state funding targeted for CTE is provided through two programs: the CTE Incentive Grant (CTEIG) program, administered by CDE, and the K‑12 Strong Workforce Program (SWP), administered by the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office. CTEIG applications are reviewed by CDE, with final approvals made by the State Board of Education. For K‑12 SWP, funding is allocated from the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office to eight SWP regional consortia based on each region’s unemployment rate, share of statewide attendance in grades 7‑12, and share of projected job openings. Each consortium has a K‑12 selection committee that reviews applications and awards grants. (These regional consortia were initially established to administer community college CTE programs.) For both programs, school districts, charter schools, COEs and ROCPs that serve students in grades 7‑12 can apply for funding.

CTEIG and K‑12 SWP Have Several Similarities. The state’s two major CTE programs have several key similarities:

- Basic Goals and Program Rules. Both CTEIG and K‑12 SWP have similar goals of expanding and supporting high‑quality CTE programs across the state. Each program provides one‑time competitive grants, with similar allowable uses of funds. School districts, charter schools, COEs, and ROCPs that serve students in grades 7‑12 may apply for funding from either program. Applicants may partner with other entities, and may apply every year for funding. Both programs generally require applicants to provide a local match of $2 for every $1 they receive in funding. (For K‑12 SWP, ROCPs are only required to provide a local match of $1 for every $1 they receive in funding.)

- Minimum Eligibility Standards. Both programs have similar minimum eligibility standards that grantees must meet to receive funding. For example, both programs require grantees to have programs that are informed by the regional plan of the local SWP consortium.

Programs Also Have Several Key Differences. Although CTEIG and K‑12 SWP have several similarities, they also have some substantive differences related to programmatic and reporting requirements, as well as structural differences in how the grants are administered. Key differences include:

- Grant Allocation. Although both programs award grant amounts primarily based on a grantee’s student attendance, there are differences in how awards are made under each program. Most notably, K‑12 SWP regional selection committees have greater discretion in selecting grantees and determining individual grantee award amounts. For example, K‑12 SWP selection committees may deny applications that they determine do not align with regional workforce needs, or may award a lower amount of funding based on various factors including the proposed scope of the work plan and the committee’s responsibility to ensure a portfolio of awards that best meets the needs of the region’s economy. Under CTEIG, applicants are scored primarily on a holistic review of their CTE programs and how well they meet the minimum eligibility standards. Base grant amounts are determined by a grantee’s student attendance, and CDE does not award less to individual grantees based on other factors.

- Use of Funds for Maintaining Existing Programs. The K‑12 SWP application prioritizes grantees that expand existing pathways to serve more students or implement new pathways, whereas CTEIG provides more flexibility to use funds for maintaining existing programs (such as purchasing new equipment and materials and remodeling facilities that are related to CTE instruction).

- Partnerships With Community Colleges. K‑12 SWP grantees are required to have partnerships with a community college for implementation of their CTE programs. CTEIG grantees have more flexibility regarding their partnerships with postsecondary institutions.

Many Grantees Receive Funding From Both CTEIG and K‑12 SWP. In 2023‑24, 132 grantees (school districts, charter schools, COEs, and ROCPs) received funding from both CTEIG and K‑12 SWP. This represents 71 percent of the K‑12 SWP grantees and 32 percent of CTEIG grantees. Grantees that receive funding from both programs must set aside local matching funds for each program, as funding from one program cannot be counted as a local match for the other. (Both programs allow grantees to use other CTE categorical funding as a local match.)

State Funds One System of Technical Assistance for Both Programs. The state provides $13.5 million annually to the California Community College Chancellor’s Office for a system of technical assistance to support both CTEIG and K‑12 SWP. Specifically, each K‑12 SWP region has a K‑14 technical assistance provider that, among other responsibilities, serves as a liaison between the consortia and CDE and convenes grantees to share best practices. In addition, there are 72 K‑12 pathway coordinators across the eight regions that, among other things, facilitate collaboration between grantees and industry.

Other Ongoing CTE Programs

California Partnership Academies. The state provides $21 million ongoing to high schools to operate small learning communities that integrate a career theme with academic education in grades 10 through 12. Grantees must meet certain requirements, such as provide a local match from the district and business partners from direct and/or in‑kind supports, offer an internship or work experience for students, and establish a common planning period for academy teachers. Currently, the state funds over 300 programs across the state. Grant amounts are based on the number of students served, up to a maximum grant of $81,000 per program.

CTE Initiative (Career Pathways Program). The state provides $15 million ongoing for funding intended to improve linkages between CTE programs at schools, community colleges, universities, and local businesses. The state has funded a variety of projects with this funding, including additional partnership academies, online curriculum and resources for CTE courses (CTE Online) administered by Butte COE, a virtual platform for career exploration and counseling (California Career Center) administered by the San Joaquin COE, and various grants for CTE‑related professional development.

Agricultural CTE Incentive Grant. The state provides $6.1 million ongoing directly to schools to improve the quality of their agricultural vocational education programs. To qualify, programs must offer three instructional components: classroom instruction, a supervised agricultural experience program, and student leadership development opportunities. In addition, grantees must provide matching funds. To receive a grant renewal, high schools must agree to be evaluated annually on 12 program quality indicators (such as curriculum and instruction requirements, leadership development, industry involvement, career guidance, and accountability). As part of this process, six regional supervisors conduct on‑site reviews and provide ongoing technical assistance to grantees. In 2024‑25, CDE awarded grants to 232 school districts. Funds typically are used by grant recipients for instructional equipment and supplies. Other allowable uses of the funds include paying for field trips and student conferences.

Specialized Secondary Programs (SSP). The state provides $4.9 million ongoing for SSP to encourage high schools to create curriculum and pilot programs in specialized fields, such as technology and the performing arts. The program also funds two high schools that are affiliated with the CSU system. (This includes an arts‑themed high school affiliated with CSU Los Angeles and a math‑ and science‑themed high school affiliated with CSU Dominguez Hills.) Of the total provided, $3.4 million is awarded in competitive grants as “seed” funding for the development of specialized instruction and $1.5 million supports the state’s two SSP‑funded high schools. The SSP seed funding is distributed in four‑year grant cycles. School districts initially apply for a one‑year planning grant. Applicants then reapply for three‑year implementation grants. Funds are permitted to cover various costs, including equipment and supplies, instructor and staff compensation, and teacher release time to develop curriculum. After the grant cycle is complete, recipients are ineligible to reapply for SSP grants.

Recent One‑Time Spending on CTE

Since 2021, the state has provided a total of $950 million ($700 million Proposition 98 General Fund and $250 million non‑Proposition 98 General Fund) for various one‑time CTE initiatives. These funds are intended to provided start‑up funding to develop and establish new CTE pathways and programs locally.

Golden State Pathways Program. The state provided $500 million for a competitive grant program intended to improve college and career readiness. Specifically, the program is intended to increase the number of CTE‑aligned pathways for high‑wage, high‑demand jobs that incorporate A‑G course requirements and/or provide students with an opportunity to earn college credits. Grantees are expected to collaborate with employers and institutions of higher education to develop these pathways. Of the total amount provided, $425 million is for implementation grants to support grantees to collaborate with their program partners. Up to $50 million is for regional consortium development and planning grants (for grantees to collaboratively plan with their program partners). As of February 2025, CDE has awarded 367 implementation grants totaling $374 million, 149 planning grants totaling $30 million, and 20 consortium grants totaling $19 million. Grant recipients are required to annually report a variety of outcome data disaggregated by student subgroups. An evaluation of the program is required to be completed by June 30, 2028. CDE was also given authority to use up to $25 million to establish a system of technical assistance. CDE selected Tulare COE as the lead technical assistance provider, and selected eight COEs to serve as regional technical assistance centers.

K‑16 Education Collaboratives. The 2021‑22 budget package provided $250 million non‑Proposition 98 General Fund to the Department of General Services for a competitive grant program to support regional collaboratives. Each collaborative must include at least one school district, community college district, CSU campus, and UC campus. To receive grants, collaboratives must commit to creating new intersegmental academic pathways in at least two of the following occupational areas: health care, education, business management, and engineering/computing. Grant recipients must also adopt at least four of seven identified educational best practices, establish a steering committee that includes local employers, participate in the state’s Cradle‑to‑Career longitudinal data system (currently in development), and participate in a statewide evaluation of the collaboratives. Grants were awarded to 13 collaboratives across the state, totaling $243 million. The remaining funds were encumbered for administrative costs.

Dual Enrollment. In 2022‑23, the state provided $200 million for a competitive grant program aimed at increasing programs that provide high school students with access to college level courses. Of this amount, $100 million was available for grants of up to $250,000 to plan and start up middle and early college high schools on K‑12 school sites. (Middle college high schools operate on community college campuses and are targeted to students who are at risk of dropping out of high school. Early college high schools partner with a community college or public university that allows students to earn a diploma and up to two years of college credit by graduation.) The remaining $100 million was available for grants of up to $100,000 to establish CCAP agreements. As of February 2025, CDE has awarded 185 grants for middle college and early college high schools, totaling $46 million, and awarded 877 grants for CCAP agreements totaling $88 million. The grant program requires CDE to provide two programmatic reports, one by June 30, 2024 and the other by June 30, 2027. These reports must include the number of grants awarded, a qualitative description of how the funding was used, and various participation and outcome data for students participating in dual enrollment programs.

Federal Funding

Perkins V Funding. The federal government provides roughly $1.4 billion in ongoing funding to states and discretionary grantees for high school and postsecondary CTE programs. The Strengthening Career and Technical Education for the 21st Century Act (Perkins V) was signed into law in July 2018, reauthorizing the federal Perkins Career and Technical Education Act. To receive funding, a state must submit a plan to the Secretary of Education that outlines the state’s approach to CTE and confirms that the state complies with certain federal regulations. For example, states must ensure CTE programs are aligned with math and English language arts standards, agree to provide technical assistance to school districts, and submit student outcome data (such as pathway completion). Of the $142 million that California received in 2024‑25, $64 million was made available to CDE to allocate directly to schools that serve high school students. The remaining funds were provided to postsecondary CTE programs and for state‑level activities.

CTE Data and Accountability

In this section, we provide an overview of CTE data the state collects and how these data are used in the state’s accountability system.

Course Data

State Collects Data on CTE Course Offerings and Enrollment. The state annually collects information from school districts, COEs, and charter schools on student‑level enrollment and demographics, program and assessment data, course enrollment, course completion, and staff assignments. This information is reported to CDE through the state’s longitudinal data system, known as the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System (CALPADS). The course data that CDE collects reflects all courses taught at each schoolsite, and for each course includes information such as the name of the course, subject area, grade level, and whether the course meets A‑G requirements. For CTE courses, the course data include the associated CTE industry sector. Additionally, the information includes the number of students enrolled in each course, as well as specified information on the staff teaching the course.

Increasing Share of Courses Meet A‑G Requirements. Course data from CDE show that total CTE course offerings have increased by 3 percent from 2018‑19 to 2023‑24. As Figure 3 shows, the share of CTE courses that meet A‑G requirements has increased from 44 percent to 66 percent over the same time period. Additionally, the share of courses that meet A‑G requirements has increased in each of the 15 industry sectors, ranging from a 6 percentage point increase (Arts, Media, and Entertainment) to a 31 percentage point increase (Business and Finance).

Figure 3

Share of CTE Courses Meeting A‑G

Requirements Has Significantly Increased

Share of Courses That Meet A‑G Requirements

|

Industry Sector |

2018‑19 |

2023‑24 |

Difference |

|

Agriculture and Natural Resources |

53% |

72% |

19% |

|

Arts, Media, and Entertainment |

71 |

77 |

6 |

|

Building and Construction Trades |

20 |

47 |

26 |

|

Business and Finance |

38 |

69 |

31 |

|

Education, Child Development, and Family Services |

32 |

59 |

27 |

|

Energy and Utilities |

49 |

70 |

21 |

|

Engineering and Architecture |

65 |

78 |

13 |

|

Fashion and Interior Design |

32 |

51 |

19 |

|

Health Science and Medical Technology |

59 |

79 |

21 |

|

Hospitality, Tourism, and Recreation |

36 |

60 |

23 |

|

Information and Communication Technologies |

45 |

69 |

24 |

|

Manufacturing and Product Development |

33 |

61 |

28 |

|

Marketing, Sales, and Service |

40 |

65 |

25 |

|

Multiple Industry Sectors |

5 |

16 |

11 |

|

Public Services |

38 |

65 |

27 |

|

Transportation |

24 |

52 |

28 |

|

Totals |

44% |

66% |

22% |

|

CTE = career technical education. |

|||

Student Outcome Data

College and Career Indicator (CCI) Part of State’s Accountability System. As part of the state’s accountability system, school districts, charter schools, and COEs report various student outcome data to the state, which is then displayed on a public website known as the California School Dashboard. Under the state’s accountability system, school districts, charter schools, and COEs that have poor performance for one or more student subgroups based on these indicators must examine their root issues and access support to help them improve. The school dashboard includes a variety of data, including standardized test scores, graduation rates, and suspension rates. Another key indicator is the CCI, which combines information about a student’s course completion and test scores to determine whether a student is prepared for college and career. As Figure 4 shows, students can demonstrate they are “prepared” or “approaching prepared” for college and career in a variety of ways. Due to the suspension of various standardized tests during the COVID‑19 pandemic, the CCI was not available from 2020 through 2022.

Figure 4

Description of College and Career Indicator

|

Prepared |

|

High School Diploma and Any One of the Following Measures: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Approaching Prepared |

|

High School Diploma and Any One of the Following Measures: |

|

|

|

|

|

Not Prepared |

|

No High School Diploma or High School Diploma but No Measures Met |

|

CTE = career technical education. |

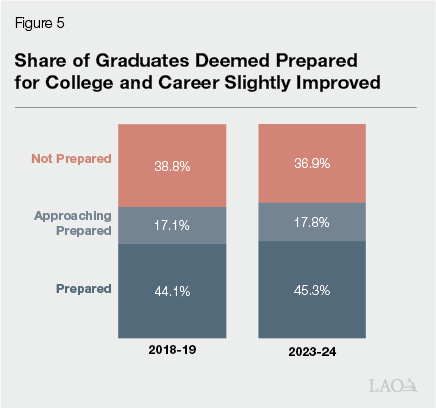

Share of High School Graduates Deemed Prepared or Approaching Prepared Has Slightly Improved. In 2023‑24, 45 percent of the state’s high school graduates were deemed prepared, 18 percent were approaching prepared, and 37 percent were not prepared. As Figure 5 shows, the share of graduates who were deemed prepared or approaching prepared increased by almost 2 percentage points from 2018‑19. The rates of preparation can vary substantially by school and by student subgroup. For example, in 2023‑24, only 37 percent of socioeconomically disadvantaged high school graduates were deemed prepared. Additionally, the share of graduates who are deemed prepared are far below the state average for homeless students (22 percent), foster youth (13 percent), and students with disabilities (14 percent).

Multiple Programs Require CTE Completer Data. Perkins V established new CTE performance indicators and modified federal reporting requirements related to CTE completers—students who have completed a sequence of courses in a CTE pathway totaling 300 hours, including a capstone course. All school districts, charter schools, and COEs operating CTE programs are required by federal law to submit postsecondary status data for their CTE completers, regardless of whether they received Perkins V funding. CTE completer data are collected through a survey of students developed by CDE. Data are submitted to the state through CALPADS and are included by CDE in statutorily required CTE reports. According to these data, 18 percent of graduating high school students in 2021‑22 completed a CTE pathway, while about 70 percent completed at least one CTE course.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

In this section, we raise three questions for the Legislature to consider in evaluating its approach to K‑12 CTE issues.

How Should the Legislature Monitor Progress on CTE‑Related Goals? Through the school dashboard, the state can monitor the share of high school graduates who are prepared for college and career. The CCI can be a useful tool to assess overall progress on this goal, as it concisely summarizes several outcome measures into one understandable metric. However, some of the data incorporated into the measure, such as completion of A‑G courses, are not related to CTE. Moreover, the CCI provides a high‑level summary of progress, but monitoring progress on more specific CTE outcomes—such as the share of students who graduate having completed a CTE pathway—can be more challenging to monitor. The state currently collects data on several of these measures through the CCI or through other means, such as the survey of CTE completers, but these outcomes are not always publicly available. In the case of other CTE objectives, such as career exploration, the state does not collect any specific outcome data. To the extent the Legislature wants to more closely monitor specific CTE outcomes, it could require that more detailed information be publicly reported. It also could require the collection of additional data that would help it monitor progress on key objectives.

Is Categorical Funding an Effective Way to Achieve the Legislature’s Key Goals? Unlike other areas in K‑12 education, such as professional development and instructional materials, the state has largely retained its categorical funding structure for CTE after the enactment of LCFF. The Legislature may want to consider whether this approach has been effective in helping the state make progress on its key goals. Funding CTE through restricted categorical grants provides some assurance that school districts will spend a certain level of funding on CTE programs, and the programs’ matching requirements can encourage districts to increase their total CTE spending. However, relying on categorical programs rather than providing more general purpose funding through LCFF is less flexible and more administratively burdensome for school districts. School districts must regularly apply for categorical funding and comply with various reporting requirements. In particular, the two major CTE programs have a substantial administrative burden because districts must apply annually for funding. Moreover, focusing the state’s oversight on how categorical funds are spent results in less attention on the outcomes the programs are intended to achieve.

What Are the Benefits of Having Multiple Categorical Programs? If the Legislature wants to maintain CTE categorical funding, it may want to consider whether having multiple CTE categorical programs is an effective way to make progress on key CTE goals. The state’s existing programs have different requirements that align with different CTE goals. For example, the K‑12 SWP is connected to regional workforce demand, while the California Partnership Academies provide specific funding to integrate CTE into core academic coursework. Creating distinct categorical programs ensures that some amount of funding is set aside for a particular priority, but provides districts with less flexibility to determine the best approach for their specific students. Moreover, several programs have very similar or overlapping requirements. For example, both K‑12 SWP and CTEIG require districts to work with regional higher education partners and align their programs with local labor market demands (though the exact requirements somewhat differ). If the Legislature is interested in modifying its current approach, it could consider consolidating programs and setting a uniform set of requirements. Alternatively, it could explore options to further distinguish programs so they each serve a distinct purpose.

Conclusion

K‑12 CTE programs have a variety of benefits for students and for the state. CTE courses can help students gain exposure to different occupations, prepare high school students for careers after graduation and provide students with specialized coursework that prepares them for matriculation into higher education. Additionally, robust CTE course offerings can help the state develop a skilled labor force to meet industry demands. The state has enacted a variety of programs intended to give students more opportunities to explore career options and complete CTE pathways that prepare them for entering the workforce or higher education. The state also collects a variety of outcome data related to CTE participation and completion. This includes the use of CCI—which tracks progress on how well students are being prepared for college and career—within the state’s accountability system. As the Legislature considers possible changes to CTE in response to the Governor’s Master Plan on Career Education, it may want to consider actions it could take to ensure that the state’s goals related to CTE are being met. The Legislature may also want to consider how the state can best allocate funding to support CTE programs and how existing data can be leveraged to better track student outcomes related to CTE.