Jason Constantouros

April 3, 2025

The 2025-26 Budget

Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Spending

Summary

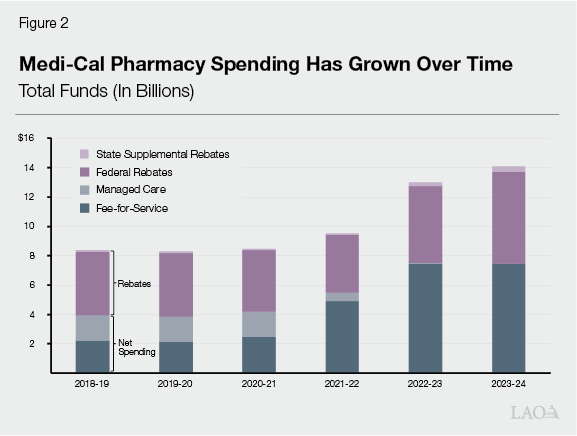

Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Spending Has Grown Over Time. Medi‑Cal, California’s Medicaid program, covers the cost of prescription drugs (among other health care services) for low‑income people. From 2018‑19 through 2023‑24, we estimate Medi‑Cal pharmacy spending nearly doubled. Nearly half of this growth was associated with certain drugs treating diabetes, obesity, and inflammatory diseases. Accordingly, the Governor’s budget assumes continued growth in pharmacy spending through 2025‑26, including a substantial upward revision in estimated spending in 2024‑25.

Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Data Could Be More Transparent. On a total funds basis (both state and federal funds), the assumed overall growth in pharmacy spending under the Governor’s budget appears to be roughly in line with recent data highlighting growth in utilization and cost. However, given data constraints, assessing some of the administration’s underlying cost assumptions is difficult. For example, the administration assumes growth in drug utilization among undocumented beneficiaries. While this growth is plausible, historical data on pharmacy use for this population is limited. Also, limited data on drug price discounts and rebates makes assessing the transition to Medi‑Cal Rx in 2022 difficult. In light of these limitations, we recommend the Legislature (1) direct the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) to report specified data annually and (2) withhold action around Medi‑Cal pharmacy spending in 2025‑26 until May Revision, when updated data are available.

State Could Better Prepare for Drug Spending Volatility. Though the full effects of Medi‑Cal Rx are uncertain, it is likely the new system has increased budget volatility and uncertainty in the Medi‑Cal program. This is because the state now pays for all drug costs directly under Medi‑Cal Rx, which are highly variable year to year. (Prior to the creation of Medi‑Cal Rx in 2022, the state indirectly paid for most prescription drugs, like most Medi‑Cal benefits, through contracts with health plans that cover the cost of care for beneficiaries.) As a result, significant midyear revisions—much like the one in the current‑year budget—may be more common moving forward. To help manage this volatility, the state in 2019‑20 created a new fund account to reserve a portion of drug rebate funds. To date, however, reserve amounts have been inconsistent. To better prepare for budget volatility moving forward, we recommend the Legislature tighten the mission and rules around this fund account in state law.

State Has Limited Control Over Pharmacy Spending. Given the state’s constrained fiscal situation, the Legislature may face pressure to limit General Fund spending growth, including in the Medi‑Cal program. The state has limited ways of doing so with regard to Medi‑Cal pharmacy spending specifically. For example, the Legislature could adjust coverage of optional drugs (such as anti‑obesity drugs) or impose certain utilization controls (such as requiring copays). That said, there are limitations and trade‑offs to consider. Most notably, federal rules limit how states can control pharmacy spending, and the federal government is contemplating whether to impose additional constraints. Also, caution is warranted when reacting to emerging trends, given the historical volatility of the drug market. To this end, we recommend the Legislature continue to monitor spending trends, particularly around optional drugs. To the extent the Legislature takes actions this year to limit spending, it will want to ensure such actions have measurable and likely impacts on long‑term state costs.

Introduction

Pharmacy Is Key Driver Behind Higher‑Than‑Anticipated Medi‑Cal Spending. State spending on Medi‑Cal—California’s Medicaid program—is expected to be higher in 2024‑25 than originally anticipated. Specifically, the Governor’s budget estimates General Fund spending for this program in 2024‑25 to be $2.6 billion (7.5 percent) higher than the level assumed at budget enactment last June. The administration estimates half of this growth to be from spending on prescription drugs, with the other half largely due to higher caseload levels.

Increase Raises Questions About Recent Delivery System Change. Over the years, the state has undertaken efforts to control Medi‑Cal pharmacy spending. Most notably, the state consolidated the way it pays for drugs into one fee‑for‑service system. The new system—known as Medi‑Cal Rx—was intended to result in lower drug costs and higher rebates. Initial projections of savings, however, have not been validated by actual data. Moreover, since the transition to the new system in 2022, newer, relatively costly drugs have become a bigger portion of Medi‑Cal pharmacy spending.

Brief Analyzes Pharmacy Spending Trends and Estimates. Given the above issues, this brief analyzes the recent pharmacy spending increases in the Governor’s budget. It begins with background on prescription drugs and Medi‑Cal’s pharmacy benefit. Next, it provides key historical spending trends and summarizes assumptions in the Governor’s budget. It then provides our assessment of these trends and associated recommendations.

Background

In this section, we describe: (1) the prescription drug market and (2) Medi‑Cal’s pharmacy benefit.

Prescription Drugs

“Prescription Drugs” Generally Refers to Drugs Purchased at a Pharmacy. Generally, prescription drugs are drugs prescribed by a doctor and purchased at a pharmacy. Coverage of prescription drugs often is referred to as a pharmacy benefit. (Drugs provided during inpatient settings, such as at the hospital, are considered to be part of the inpatient service.) Prescription drugs represent around 10 percent of personal health care spending in the United States and in California.

Drug Market Is Complex and Opaque. Many health care services involve transactions between providers, patients, and payors (such as private health insurance and government programs) that reimburse providers for services. For prescription drugs, however, there are additional entities involved. These entities include (1) the drug makers, generally large manufacturing companies; (2) wholesalers, large companies that help distribute drugs into the market; and (3) pharmacies, entities that purchase drugs and dispense them to patients. Moreover, many health care payors contract with third parties (known as pharmacy benefit managers) to manage their enrollees’ drug benefits and claims. Different kinds of financial transactions occur between these entities—many of which are confidential. As a result of this complex and opaque system, it can be difficult to track drug prices and costs over time.

Drug Market Is Constantly Evolving. The drug market has been a major source of innovation within the health care sector. This is because drug makers continue to research and develop new drugs for patients. This evolving market can have different effects on costs. For example, new brand name drugs that enter the market can be quite expensive, driving up costs. On the other hand, drugs makers lose their exclusive rights to sell the brand drugs over time, allowing competitors to sell generic versions and drive down costs.

Medi‑Cal’s Pharmacy Benefit

Medi‑Cal Covers Health Care Services for Low‑Income People. Medi‑Cal is California’s combined Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Both Medicaid and CHIP are joint federal‑state programs that cover health care services to low‑income people. In California, the Medi‑Cal program is a particularly large part of the health care sector, currently enrolling nearly 15 million people (more than one‑third of the state’s population).

Medi‑Cal Coverage Includes Pharmacy Benefits. Under federal law, state programs must cover a minimum set of health care services (such as doctor’s visits and hospital stays). Services beyond this minimum are optional. Pharmacy is one key benefit that is optional—meaning that states are not required to cover the cost of prescription drugs to operate their Medicaid programs. Nonetheless, all states—including California—cover pharmacy benefits in their Medicaid programs.

California Has Little Control Over Pharmacy Benefits, With Some Exceptions. Once choosing to cover pharmacy benefits in their Medicaid programs, states must cover most drugs available to patients. Specifically, states must cover nearly all drugs from drug makers that participate in the federal Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (described further a little later). With this restriction in place, states have limited ability to adjust pharmacy spending levels over time. That said, there are two key flexibilities that offer states limited control:

- Optional Drugs. Under federal law, certain kinds of drugs, such as weight loss drugs, are optional for states to cover. As Figure 1 shows, California has chosen to cover many, but not all, of these optional drugs.

- Utilization Controls. Federal law also allows states to implement policies that help limit utilization of drugs. For example, most states (including California) maintain lists of preferred drugs. Drugs that are not on these lists (known as the “contract drugs list” in Medi‑Cal) are subject to certain constraints, such as having to get special approval to prescribe to patients. States also can enact other tools, such as by limiting the number of monthly prescriptions and requiring copays. Historically, Medi‑Cal included some of these tools (such as by charging $1 copays). As part of the 2020‑21 budget, however, the Legislature eliminated these tools, with the aim of simplifying pharmacy benefits and increasing access.

Figure 1

Medi‑Cal Covers Some Kinds of

Optional Drugs

|

Optional Drug |

Medi‑Cal Coverage? |

|

Anorexia/weight loss or gain |

Yes |

|

Cosmetic/hair growth |

No |

|

Cough/cold relief |

Yes |

|

Fertility |

No |

|

Nonprescription drugs |

Yes |

|

Vitamins and minerals |

Yesa |

|

aOnly certain products, subject to prior authorization or other restrictions. |

|

State Recently Created New “Medi‑Cal Rx” System to Pay for Drugs. Most Medi‑Cal beneficiaries are enrolled in the program’s managed care system, in which the state pays health plans each month to cover services for beneficiaries. A small share of people (less than 10 percent) are not enrolled in a health plan, and instead have their services paid for directly by the Medi‑Cal program on a fee‑for‑service basis. Historically, the state also took this bifurcated approach to pay for prescription drugs. Beginning in 2022, however, the state consolidated pharmacy benefits under one system called Medi‑Cal Rx. Under this approach, the state pays for all drug claims on a fee‑for‑service basis—including for people in the managed care system. The new Medi‑Cal Rx system was intended to lower costs and increase savings on drugs. The state contracts with a third party (Magellan Medicaid Administration) to help manage the Medi‑Cal Rx system. Though initially enacted via executive order, Medi‑Cal Rx later became permanent in state law when voters enacted Proposition 34 (2024).

Net Spending on Drugs Driven by Two Key Components. Medi‑Cal pharmacy spending generally consists of two key components:

- Gross Payment for Drugs and Pharmacy Services. First, the state pays pharmacies for delivering drugs to patients. For each prescription, there are two payments: (1) the cost of the drug, generally based on the cost to the pharmacy of purchasing the drug; and (2) a set rate to pharmacies (either $10 or $13, depending on the size of the pharmacy) for the cost of dispensing the drug.

- Savings From Negotiated Rebates. After paying pharmacies for the drugs, Medi‑Cal submits claims to drug makers for negotiated rebates. These rebates provide money back to the Medi‑Cal program, effectively helping to offset some of the cost of the drugs. Most of the savings come from federally negotiated rebates. In addition, the state also negotiates supplemental rebates. The nearby box provides more information on how rebates work in the Medi‑Cal program.

How Do Drug Rebates Work in Medi‑Cal?

Federal Rebates Are Mandatory and Determined by Formula. Created in 1990 and revised over time, the federal Medicaid Drug Rebate Program determines federal rebates for drugs in the Medicaid program. Drug makers must agree to participate in this program as a condition of having their drugs covered by state Medicaid programs. Rebates for specific drugs, which are considered confidential, are set by formulas. Under these formulas, a drug’s initial rebate is between 13 percent and 23 percent of its price, depending on the type of drug. Over time, the initial rebate increases if the drug’s price rises faster than inflation. Consequently, older drugs (which have tended to have price increases over time in excess of inflation) can come with much higher rebates. Drug makers pay their rebates to states, which then submit the federal share of savings to the federal government.

State‑Negotiated Supplemental Rebates Are Voluntary. In addition to the mandatory federal rebates, the state (through the Department of Health Care Services) negotiates additional rebates with manufacturers. Unlike for federal rebates, drug makers are not required to provide state‑negotiated supplemental rebates. To induce participation, California leverages its negotiating power by including drugs with supplemental rebates in its preferred drug list. State supplemental rebates historically have comprised just a fraction of the overall savings from Medi‑Cal rebates.

State and Federal Government Share Pharmacy Costs and Rebate Savings. As a joint federal‑state program, Medi‑Cal’s costs are shared between federal and state funds. The federal share of cost in each state generally is determined by a formula, with the share in California at 50 percent. Each state’s specific federal share (in California’s case, 50 percent) also applies to gross pharmacy costs and drug rebate savings, with some exceptions. For example, drugs associated with childless, nondisabled adults (as well as most other services for this population) come with a 90 percent federal share. On the other hand, the state generally pays for the full cost of drugs for undocumented beneficiaries (as is the case for many other services to this population). Drugs to undocumented beneficiaries also generally are not eligible for rebates. The state’s General Fund covers the state share of cost and savings for drugs.

Key Trends

In this section, we summarize key historical and projected trends in Medi‑Cal pharmacy spending. As the nearby box explains, we analyzed trends by combining data from federal and state sources. Because we combined data from different sources, some of which use different methodologies, our findings have some limitations. As such, the below trends should be treated as rough estimates. Below, we summarize trends on overall pharmacy spending and spending by type of drug.

How Did We Compile Estimates in This Brief?

For Overall Spending, Two Key Sources. To measure overall Medi‑Cal pharmacy spending trends over the last few years, we used two key sources of data. (Our methodology largely follows the approach taken by other health policy organizations, such as the Kaiser Family Foundation.)

- Gross Spending—State Drug Utilization Data. Under federal law, states must report to the federal government quarterly drug utilization information in their Medicaid programs. These data include the number of prescriptions and gross Medicaid spending for each drug. The data are publicly available. Accordingly, we downloaded California’s drug utilization data from the first quarter of 2018 through the second quarter of 2024 (the latest quarter available at the time of our analysis).

- Rebates—Federal Financial Management Reports. Federal law also requires states to submit annual financial information on their Medicaid programs. These financial reports, which also are available to the public, include line‑item information on federal and state supplemental drug rebate savings. Accordingly, we downloaded available financial reports through federal fiscal year 2023 (the last year available at the time).

For Drug‑Level Spending, Federal Drug Classifications. We also used drug utilization data to track which drugs have driven changes in pharmacy spending. However, the data on their own are not conducive to effective trend analysis. This is because each quarter of data contains around 40,000 line items, and some drugs are spread across multiple lines. To better simplify these data, we used each drug’s classification as identified under the Food and Drug Administration’s National Drug Code Directory. These classifications generally categorize drugs based on how they work, how they are used, and other factors. There are over 1,000 such classifications in the federal directory.

Analysis Likely Omits Some Key Kinds of Drug Claims. Generally, states are required to report Medicaid drug utilization data connected to federal drug rebates. Federal guidance directs states to exclude reporting certain drug claims outside of the rebate system. For example, states are to exclude drugs that come with federal price discounts (known as 340B discounts). These drugs do not come with rebates, because federally required price reductions already occurred at the front end when the pharmacy purchased the drugs. Federal guidance also directs states to exclude claims that do not come with a federal share of cost. For example, drugs for undocumented immigrants do not qualify for federal cost sharing or rebates. As such, these kinds of drugs likely are excluded from our trend analyses.

Overall Spending

Pharmacy Spending Has Grown in Recent Years, in Line With Medi‑Cal Program. Over the years, Medi‑Cal pharmacy spending has continued to grow, both on a gross basis and after netting out rebates. As Figure 2 shows, we estimate (based on historical federal data) that Medi‑Cal pharmacy spending in 2023‑24 was nearly double the level in 2018‑19. Pharmacy spending continued growing even after the roll out of Medi‑Cal Rx in 2022. While this growth seems fast in isolation, it is roughly in line with overall Medi‑Cal spending over the same time period.

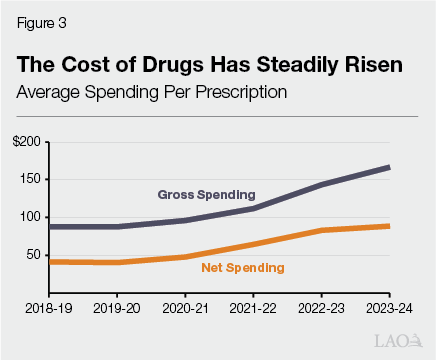

Average Drug Costs Have Been Key Driver of Spending Increase. Spending on Medi‑Cal services is driven by caseload, service utilization, and service costs. Based on historical trends, the growth in pharmacy spending specifically appears to be driven by higher drug costs. As Figure 3 shows, we estimate the average cost per drug nearly doubled over the period, with the growth somewhat lower on a net spending basis. While overall Medi‑Cal caseload also increased over the same period, the increase was much slower (17.6 percent).

Federal Rebates Appear to Have Ebbed and Flowed Over Time. Based on limited data, the level of federal rebates also appears to have grown over time. As a percent of gross spending, however, the trend appears to be somewhat variable, fluctuating between 40 percent to 50 percent over the period. These estimates are imprecise, however. Several factors can drive changes in federal rebates. For example, increasing use of generic drugs, which come with lower costs and lower rebates than brand name drugs, can drive down rebates.

State Supplemental Rebates Appear to Be Increasing. Our imprecise estimates also suggest that state supplemental rebates have ebbed and flowed somewhat over time, but generally in the upward direction. In 2023‑24, we estimate these rebates comprised 3 percent of gross spending, up from as low as 1 percent in some years. This increase was expected following the switch to the Medi‑Cal Rx system in 2022. This is because the state did not receive state supplemental rebates on drug claims in the managed care system.

Spending by Drug Type

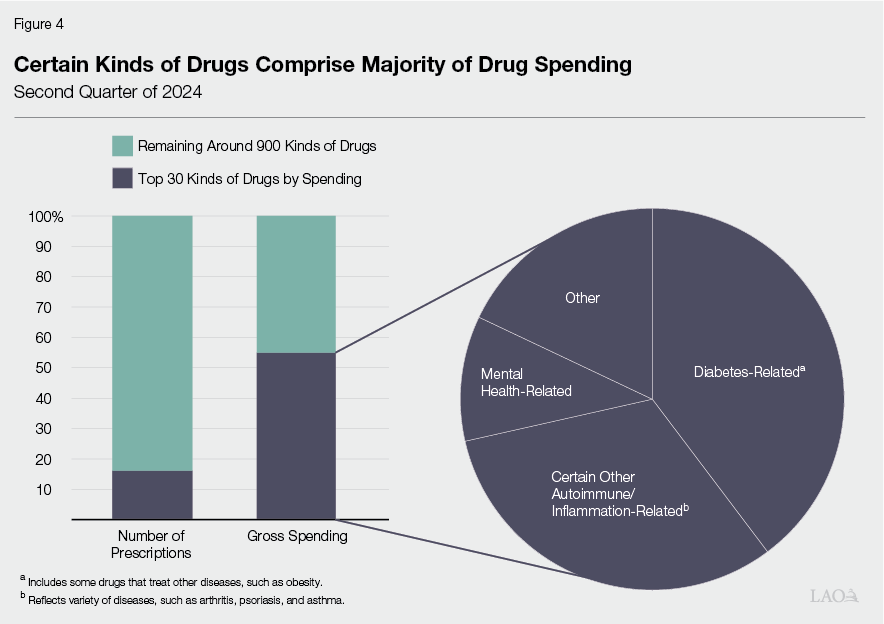

Several Kinds of Drugs Represented Bulk of Spending. Spending on drugs is fairly lopsided, with certain kinds of drugs representing much of the spending. To gauge this effect, we looked at the kinds of drugs that represented the most gross spending in the Medi‑Cal program. As Figure 4 shows, the top 30 drugs in terms of spending (out of about 950 drug categories) represented less than 20 percent of all prescriptions (left column) but more than 50 percent of gross spending (right column). Within these 30 kinds of drugs, the majority treat diabetes (or other related issues, described further below), certain other autoimmune or inflammatory diseases (such as arthritis or psoriasis), and mental illness.

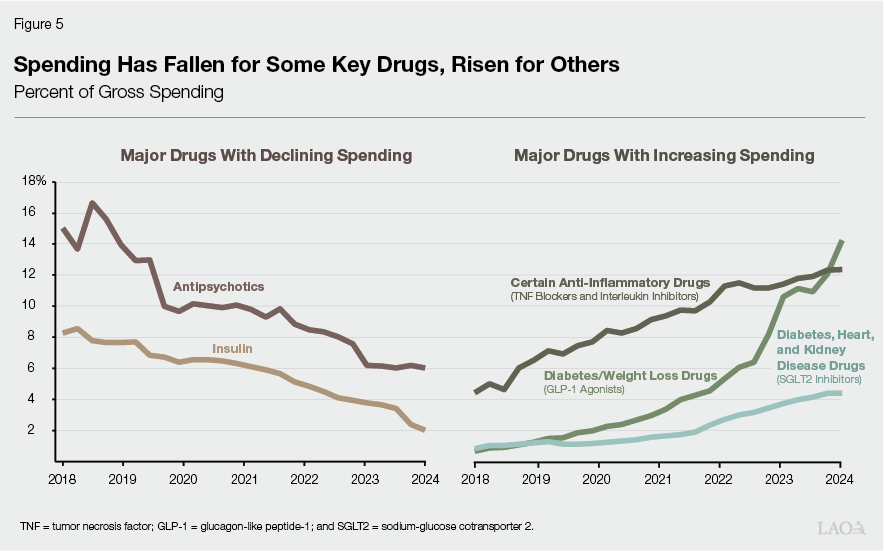

Three Kinds of Drugs Comprised Bulk of Spending Increases. When looking at the start of the period and the end of the period, different kinds of drugs represented the most gross spending. As Figure 5 shows, at the start of 2018, antipsychotics (drugs that treat certain mental health conditions) and insulin (drugs that help regulate blood sugar for diabetics) represented around one‑quarter of gross spending. By 2024, however, these drugs represented a smaller percentage. In their place, newer specialty anti‑inflammatory and diabetes‑related drugs represented around one‑third of gross spending. In all, we estimate these newer specialty drugs accounted for around half of the growth in overall gross pharmacy spending over the period.

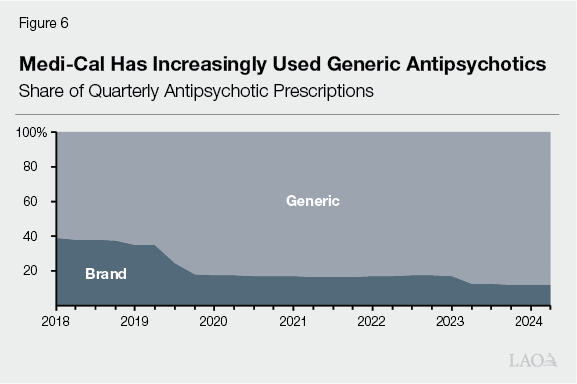

Increasing Use of Generic Drugs Helped Limit Spending on Antipsychotics. Antipsychotics historically have represented a large portion of pharmacy spending in Medi‑Cal and in other state Medicaid programs. This is in part because of their relative cost. In particular, a few decades ago, relatively expensive second‑generation versions of these drugs (known as “atypical antipsychotics”) entered the market. Over time, the initial brand drugs have lost their patent exclusivity and generic competitors have entered the market. As Figure 6 shows, generic versions have become a growing share of antipsychotic prescriptions. Because these generic drugs are notably less expensive than their brand counterparts, their increasing use has helped limit spending on antipsychotics, driving down their share of overall gross pharmacy spending in Medi‑Cal.

Spending on Insulin Is Down… Historically, insulin also has comprised a substantial share of gross spending on drugs. Over time, however, we estimate that this share has fallen. A few factors seem to be behind this trend. Most importantly, utilization appears to have declined somewhat. More recently, some of the largest makers of insulin notably reduced prices, yielding declines in average cost. The notable reduction has been attributed to recent federal policy changes around Medicaid drug rebates.

…While Newer Blood Sugar‑Regulating Drugs Have Increased Spending. Though the share of spending on insulin appears to have declined, spending on certain other diabetes‑related drugs increased considerably. The most notable increase (alone comprising 25 percent of the growth in overall spending over the period) was for specialty diabetes and weight loss drugs (known as Glucagon‑Like Peptide‑1, or GLP‑1, agonists). As the nearby box explains, these drugs stimulate insulin production and lower appetite. As a result, some of these drugs also are approved for obesity treatment, even for patients without diabetes. Somewhat less notably, spending also has increased for drugs that help control blood sugar, kidney disease, and heart disease among diabetics (known as Sodium‑Glucose Cotransporter 2, or SGLT2, inhibitors). For both kinds of drugs, rapid growth in utilization has driven the higher spending levels.

What Are Glucagon‑Like Peptide‑1 (GLP‑1) Agonists?

GLP‑1 agonists are a type of drug that help regulate blood sugar, generally by stimulating the release of insulin in the body. Use of these drugs also can result in weight loss among patients. Accordingly, in recent years, newer brands of drugs specifically focused on treating obesity have entered the market. As the nearby figure shows, there are three key GLP‑1 agonists, each with different brand names for treating diabetes and obesity. Within the Medi‑Cal program, semaglutide has comprised most of the utilization of GLP‑1 agonists, mostly for Ozempic (which primarily treats diabetes). That said, utilization could increase for other GLP‑1 agonists over time. This is because tirzepatide and its associated brands entered the market only a few years ago.

Different Brands Treat Obesity and Diabetes

Glucon‑Like Peptide‑1 (GLP‑1) Agonists

|

Drug |

Maker |

Brand |

|

|

Obesity |

Diabetes |

||

|

Semaglutide |

Novo Nordisk |

Wegovya |

Ozempic, Rybelsus |

|

Tirzepatide |

Eli Lily |

Zepbound |

Mounjaro |

|

Liraglutide |

Novo Nordisk |

Saxenda |

Victoza |

|

aAlso approved for cardiovascular disease. |

|||

Certain Kinds of Anti‑Inflammatory Drugs Also Drove Up Spending. Some of the most‑used drugs in Medi‑Cal address inflammatory diseases and conditions. Many of these drugs are not particularly expensive and therefore comprise relatively smaller shares of overall spending. In recent years, however, we estimate certain kinds of relatively costly anti‑inflammatory drugs (including tumor necrosis factor, or TNF, blockers, and interleukin inhibitors) helped drive up spending over time. Over the period, utilization increased (particularly for interleukin inhibitors) and costs rose. Recent entry of newer brand drugs partly has contributed to these trends.

Drug‑Level Net Spending Trends Are Uncertain. All of the above spending trends reflect gross pharmacy spending, before rebates. Because drug‑level rebate information is not publicly available, it is not certain how drug‑level spending trends differ on a net spending basis. Limited evidence, however, suggests that some the above trends hold even after factoring rebates. For example, research suggests that Medicaid rebates have been growing as a share of gross spending for major insulin brands.

Governor’s Budget

Assumes Increase in Gross Drug Spending. Under the Governor’s budget, gross pharmacy spending in Medi‑Cal in 2024‑25 is estimated to be $19.4 billion total funds, a $1.6 billion (9 percent) increase over the level assumed at budget enactment last year. This revision is the result of having six additional months of data in 2024 to estimate spending. From this revised level, gross spending rises by $1.2 billion (6 percent) to $20.6 billion in 2025‑26. The administration’s back up does not readily provide the portion of this spending attributable to General Fund. However, we understand based on limited information from the administration that the 2024‑25 revision reflects an increase of $1.3 billion General Fund.

Increase Driven Both by Higher Caseload and Costs. Generally, the uptick in spending in the Governor’s budget is from higher caseload and the higher cost of drugs. Specifically, in the last two quarters of 2023, the number of enrollees using drugs and average monthly cost of drugs came in higher than initial predictions. This uptick in actual data, in addition to DHCS assumptions around Medi‑Cal caseload, shifted the department’s pharmacy projection model. According to the administration, a sizable portion of the increase in caseload is attributable to undocumented beneficiaries, though drug utilization patterns among this population is not publicly available. The department attributes the uptick in average drug costs to increasing use of specialty diabetes/obesity drugs.

Assumes Higher Rebates, but Lower State Savings. Similar to the increase in gross drug spending, the Governor’s budget assumes a rise in drug rebate savings. Specifically, drug rebates are estimated to be $6.8 billion in 2024‑25, a $145 million (2.2 percent) increase over the assumed level at budget enactment. Rebates further increase in 2025‑26. The increases largely are attributable to assumed higher savings from state supplemental rebates. Despite increasing on a total funds basis, the state’s share of savings is expected to be lower in 2024‑25 (by 13 percent) and then to further decline (by 0.8 percent) in 2025‑26. Federal savings, in turn, are projected to be higher over the period. The department attributes the lower state savings to a larger share of rebates coming from claims associated with childless adults. (For this population, 90 percent of rebate savings go to the federal government, instead of 50 percent for most other populations.)

Assessment and Recommendations

In this section, we provide our assessment and associated recommendations of the Governor’s budget pharmacy estimate and recent spending trends. As Figure 7 shows, we raise three key points. Below, we describe each issue.

Figure 7

We Raise Three Key Issues Around

Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Spending Trends

LAO Assessment

|

|

|

Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Data Could Be More Transparent

In Some Ways, Pharmacy Data Is More Robust Than for Medi‑Cal Services. Generally, data on utilization and cost are fairly limited for most Medi‑Cal services. This is because Medi‑Cal primarily relies on the managed care system to deliver services, in which contracted health plans manage provider claims and payments. In this regard, the state has relatively richer data on Medi‑Cal pharmacy spending, which is entirely now fee‑for‑service. Also, longstanding federal rules require states to report on drug utilization, including in their managed care systems. Given these richer data, the Legislature has relatively robust information to track and assess pharmacy spending trends over time.

In Other Ways, However, Pharmacy Data Are Limited. Despite having relatively rich data on drug utilization, California lacks complete data in some areas related to pharmacy spending. Most notably, actual data on federal and state rebates are notably limited. This in part reflects the fact that drug‑level rebate information is confidential, though even actual data on aggregate rebates—which are not confidential—are limited. These limitations make it difficult to comprehensively assess Medi‑Cal pharmacy spending over time.

Data Limitations Hinder Full Assessment of Governor’s Budget Estimates… Operating within these data limitations, the Governor’s budget assumptions around Medi‑Cal pharmacy spending generally appear reasonable on a total fund basis. The administration’s modelling generally reflects updated data around utilization and costs. That said, some parts of the administration’s projections are difficult to assess. For example, though the administration historically has reported overall fee‑for‑service utilization and spending trends by major Medi‑Cal population, these data have not included breakouts for undocumented populations. For this reason, while growth in drug utilization and cost is plausible for this population, it is difficult to fully assess how changes in undocumented enrollment are driving General Fund spending on pharmacy benefits. Also, the lack of complete actual data on drug rebates complicates assessing DHCS’s assumptions around federal and state rebates in the current year and budget year.

…and Savings From Change to Medi‑Cal Rx. Data limitations also hinder more comprehensive assessment of the savings from the switch to the Medi‑Cal Rx delivery system in 2022. Though a topic of interest to the Legislature, the assumed savings from the adoption of Medi‑Cal Rx have not been validated with actual data. As Figure 8 shows, Medi‑Cal Rx was intended to save the state money in a few different ways. Most of these effects remain uncertain, even with a few years of implementation underway.

Figure 8

Most Intended Effects of Medi‑Cal Rx Remain Uncertain

Key Areas of Intended Savings Under Medi‑Cal Rx

|

Area of Pharmacy Spending |

Intended Fiscal Effect |

|

|

Description |

Has It Happened? |

|

|

State savings from federal price discounts |

Increase. Savings accrue to state (rather than to providers under managed care system). |

Yes, but Effect Limited. State likely earned savings from price discounts, though total savings unknown. Portion of savings was redirected back to nonhospital providers as supplemental Medi‑Cal payment. |

|

Supplemental rebates |

Increase. Increased state supplemental rebates (which state could not claim in managed care system), resulting in more savings. |

Uncertain. State rebates appear to have increased, but managed care plan‑negotiated supplemental rebates have ended. Net effect of these two factors is unknown. |

|

Administrative costs savings |

Increase. Reduced costs for managed care plans. |

Uncertain. Net savings to plans have not been documented. |

Given Limitations, Recommend Stronger Transparency Around Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Spending. Given the above issues, we recommend the Legislature take actions to further enhance transparency around pharmacy spending in Medi‑Cal. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature direct DHCS to annually report on the following information: (1) complete drug utilization data in the Medi‑Cal program, including for claims excluded in the federal data; (2) data on fee‑for‑service average monthly prescription drug users, claims, and costs by major Medi‑Cal population, including breakouts for undocumented beneficiaries; and (3) actual annual aggregate federal and state drug rebate trends. Moreover, we recommend the Legislature direct DHCS to report on the estimated savings resulting from the implementation of Medi‑Cal Rx, with a potential due date in spring 2026. While such reporting could come with heightened administrative costs at DHCS, it also would better inform legislative discussions and decisions in future budgets.

Recommend Withholding Action on Budget‑Year Spending. Given the uncertainty around projecting pharmacy spending, we recommend the Legislature withhold final action on Medi‑Cal spending (including pharmacy spending) in 2025‑26 until after the release of the May Revision. At that point, more updated data on pharmacy spending trends will be available to better inform decisions.

State Could Better Prepare for Drug Cost Volatility

Managed Care System Is Intended to Reduce Volatility. Originally, Medi‑Cal paid for most services on a fee‑for‑service basis. Over time, however, the state has shifted most enrollees and services into the managed care system. The managed care system is intended to bring several advantages to the state and to Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. From a fiscal perspective, the chief intended advantage is to limit the state’s exposure to the financial risk from swings in service utilization and costs. Instead, the managed care system enables the state to shift some of this risk onto health plans. That is, the managed care system, in concept, helps reduce budget volatility in the Medi‑Cal program.

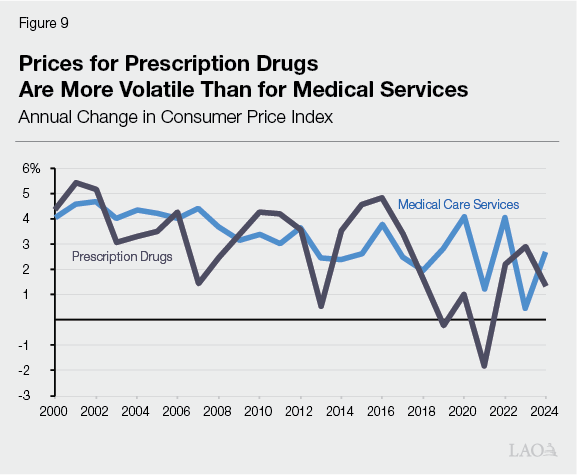

Shifting Pharmacy to Fee‑for‑Service Likely Increased Volatility and Uncertainty. While the overall fiscal effects of Medi‑Cal Rx remain uncertain, it is likely the transition to the fee‑for‑service approach in 2022 increased budget volatility in Medi‑Cal. This is because the state now bears the full risk of swings in pharmacy spending. As Figure 9 shows, as measured by the consumer price index, prescription drug prices tend to rise and fall much more substantially than for medical services. These swings in part are driven by the relatively dynamic drug market, with new entrant brand drugs and generic competitors pushing up and pulling down costs. As such, significant upward and downward revisions in pharmacy spending—much like the one in the current‑year budget—may be more common moving forward.

While Fund Exists to Managed Drug Spending Volatility and Uncertainty… In recent years, the administration and the Legislature have sought to develop tools to mitigate spending volatility in Medi‑Cal. In the case of pharmacy spending, volatility is managed in part through a special fund called the Medi‑Cal Drug Rebate Fund, created in 2019‑20 trailer bill legislation. The state share of drug rebate savings is deposited into the special fund. (Previously, these savings would directly offset General Fund spending, without being deposited in a special account.) According to analyses at the time, the purpose of the fund was to hold some of the monies in reserve during years of relatively high rebate savings. The state could then draw from this reserve during years of relatively lower rebates.

…Effect of Fund Has Been Limited. Though apparently agreed to in concept by the Legislature and administration, the rebate fund’s mission is not specified in the existing authorizing statute. Moreover, the statute does not specify target reserve levels for the fund. Accordingly, reserve levels have been determined each year as part of the annual budget process. These levels have been somewhat inconsistent in the six years since the fund’s creation, ranging from 0 percent to around 25 percent of state drug rebate savings each year. This inconsistency stems in part from the state using the reserves to address broader budgetary problems. In fact, the state has swept the fund’s planned reserve three times (in 2020‑21, 2023‑24, and 2024‑25) as a budget solution. As a result, the fund had a relatively small reserve at the end of 2023‑24 ($127 million) available to help manage the significant upward revision in pharmacy spending in 2024‑25.

Recommend Tightening Rules Around Drug Rebate Fund. To better prepare for pharmacy spending volatility and uncertainty moving forward, we recommend the Legislature enact tighter rules around the Medi‑Cal Drug Rebate Fund’s reserve levels. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature codify the fund’s mission to better manage pharmacy spending volatility and uncertainty. Moreover, we recommend the Legislature set forth target reserve levels and guidelines around when to draw down money from the reserve.

State Has Limited Control Over Pharmacy Spending

Rising Pharmacy Spending Comes at Time of State Fiscal Constraints. As we have noted in other publications, the Legislature faces a constrained General Fund budget with limited capacity for new ongoing spending. This is because, while roughly balanced in the short run, the Governor’s budget assumes a structural deficit in the out‑years. The upward revision in Medi‑Cal spending could further exacerbate these constraints.

Some Cost Pressure Appears to Be From Optional Drugs. The Legislature appears to have some—though limited—control over the growth in Medi‑Cal pharmacy spending. In particular, some of the growth appears to be driven by optional anti‑obesity drugs. To date, these drugs have been a small share of pharmacy spending. In 2023‑24, we estimate the state spent in the low‑to‑mid hundreds of millions of dollars in total funds on Wegovy, the main anti‑obesity drug. The state cost was likely less than half of this amount, particularly after netting out rebates. However, pharmacy spending has grown rapidly due to growing utilization. Moreover, newer high‑cost, anti‑obesity brands have entered the market. Entry of new brands tends to drive up spending. As a result, spending on these drugs could be quite a bit higher in the future. California also covers some other kinds of optional drugs, though we are not aware of more comprehensive spending estimates for these drugs.

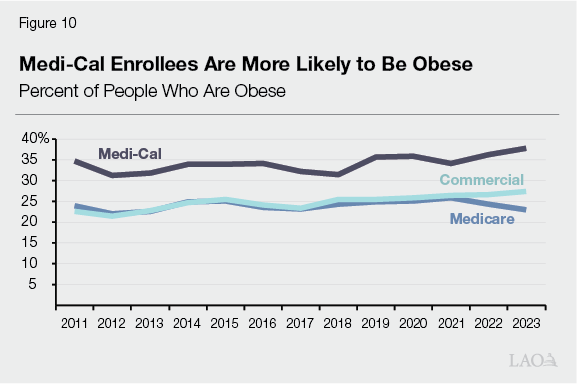

Covering Anti‑Obesity Drugs Comes With Trade‑Offs. In considering whether to turn to the state’s current coverage of anti‑obesity drugs to limit growth in pharmacy spending, the potential savings from eliminating coverage would need to be weighed against its policy benefits. The fact that Medi‑Cal’s coverage of anti‑obesity drugs appears to be much more extensive than other payors suggests that this might be a reasonable place to turn for savings. Historically, the Medicare program has not covered the cost of weight loss drugs, and a recent University of California analysis found most private health plan enrollees similarly lack comprehensive coverage. California also appears to stand out from most other states, with just 12 other state Medicaid programs covering these drugs as of August 2024. On the other hand, California’s policy reflects the recognition of obesity as a disease. Also, as Figure 10 shows, nearly 40 percent of adults in Medi‑Cal report being obese, a higher rate than for Californians with private insurance or Medicare.

Anti‑Obesity Drugs May Become Mandatory, Limiting the Availability of a Savings Option. When assessing the trade‑offs of covering anti‑obesity drugs, it is important to consider that the federal rules may change soon. In particular, in late 2024 the federal administrators proposed new rules to reinterpret federal statute around anti‑obesity drugs. The new interpretation would no longer exclude covering these drugs in Medicare. In addition, it would require coverage in Medicaid—effectively no longer making these kinds of drugs optional. To date, the federal government has not finalized these proposed rules. Adoption of these rules is particularly uncertain given that a new federal administration began its term in early 2025.

State Also Can Consider Other Tools to Control Drug Utilization. Beyond weighing the trade‑offs of covering optional drugs, California likely has other tools at its disposal to control drug utilization. This is because federal law allows for some limited tools, such as by charging copays. However, the potential effects of these tools are uncertain, and some tools may only have limited effect. For example, federal rules cap copays for preferred drugs to a small amount relative to the cost of many high‑cost drugs.

Recommend Legislature Continue to Monitor Trends Related to Optional Drug Coverage… Given the trade‑offs at hand and inherent uncertainty with predicting drug spending, we recommend the Legislature focus on monitoring trends in the short term. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature require DHCS to annually report on utilization and spending on optional drugs, including anti‑obesity drugs, to track their fiscal impacts. (This information could be included as part of DHCS’s annual data transparency reporting we recommend earlier.) With more consistent information at hand, the Legislature could better weigh the trade‑offs of choosing to cover these drugs over time.

…And Exercise Caution When Reacting to Emerging Trends. Given the state’s current fiscal constraints, the Legislature may face pressure to take actions to control Medi‑Cal pharmacy spending, such as by scaling back coverage (where allowed) or imposing new utilization controls. While taking some actions now could be reasonable, we also urge caution when reacting to emerging pharmacy spending trends. This is because the drug market is dynamic and tends to change significantly over time. As our own analysis suggests, many of the recent cost‑driving drugs comprised relatively minimal portions of gross spending several years ago. To this end, the Legislature will want to ensure that any actions taken this year have measurable and likely impacts on long‑term state costs.