Natalie Gonzalez

February 17, 2026

The 2026‑27 Budget

California Student Aid Commission

Summary

Brief Covers the California Student Aid Commission (CSAC). This brief provides an update on cost estimates for the Cal Grant program and analyzes the Governor’s budget proposal for the Middle Class Scholarship (MCS) program.

Cal Grant and MCS Costs Have Increased Over the Past Decade. Since 2015‑16, spending has increased by more than $600 million for the Cal Grant program and by more than $950 million for the MCS program. We analyze the underlying drivers of this higher spending. For the Cal Grant program, much of the increase is attributable to several policy changes the state made over the past decade, together with tuition increases that the two public university systems have implemented. (Cal Grants cover full tuition at in‑state public universities.) These changes have resulted both in larger Cal Grant award amounts and more students being eligible for Cal Grant awards. Similarly, the state revamped the MCS program in 2022‑23, which generally increased award amounts and expanded program eligibility. The eligibility changes resulted in a seven‑fold increase in the number of MCS recipients.

Cal Grant Spending Continues to Increase Under Governor’s Budget. The Governor’s budget revises 2025‑26 Cal Grant spending upward by $107 million (3.8 percent) relative to the enacted level. From the revised 2025‑26 level, the Governor’s budget increases Cal Grant spending by $337 million (12 percent), bringing total program spending to $3.2 billion in 2026‑27. Though the Governor does not propose any further Cal Grant expansions, tuition increases at the public universities continue to raise Cal Grant costs. CSAC also assumes that the number of recipients will continue to increase in 2026‑27, particularly in the California Community College (CCC) Expanded Entitlement and High School Entitlement programs.

Governor’s Budget Proposes a Reduction in MCS Award Coverage. MCS awards reflect a certain percentage of students’ remaining cost of attendance after accounting for their available resources (including any gift aid they receive). MCS awards cover 35 percent of a student’s remaining cost of attendance in 2025‑26. In 2026‑27, the Governor proposes reducing award coverage to 17.5 percent. The administration estimates that this would reduce program spending from $1.1 billion in 2025‑26 to $513 million in 2026‑27 (a $541 million reduction in spending). Last year, the state adopted a new budgetary approach for the MCS program. Under the new budgetary approach, the state began funding the MCS program one year in arrears. As a result, the state would not achieve the identified General Fund savings until 2027‑28.

Recommend Legislature Consider Adopting Proposal to Reduce MCS Award Coverage. Given projected out‑year budget deficits, the Legislature likely will have to consider budget‑balancing proposals over the next couple of years. The Governor, however, has only one proposed budget solution in all of higher education that would help balance the budget in 2027‑28. Beyond facing a deficit, the MCS program has certain drawbacks. It has significant overlap with the Cal Grant program, but is less targeted to lower‑income students, while being more complex to convey and administer than other financial aid programs. For all these reasons, reducing MCS award coverage could be among the least disruptive choices the Legislature faces.

Consider Funding Program Using More Standard Budget Practice. The new budgetary approach of paying for MCS one year in arrears creates a debt obligation for the state. We recommend the Legislature give high priority to retiring this debt once one‑time funding becomes available. The state could still set MCS award coverage in advance to provide greater clarity for campuses and students. However, rather than funding the program one year in arrears, the state could budget based on an estimate of MCS program costs for the coming fiscal year. It could then allow CSAC to access a small loan towards the end of the fiscal year if the budget appropriation falls short of covering program costs and then true up the actual cost the following year. This is how the state budgets for the Cal Grant program.

Introduction

Brief Focuses on CSAC Budget. CSAC is the primary state agency that administers student financial aid programs. This brief analyzes the Governor’s 2026‑27 budget proposals for CSAC. The brief contains two sections covering CSAC’s two largest programs. The first section focuses on the Cal Grant program whereas the second section focuses on the MCS program. Our CSAC Budget and Changes in CSAC General Fund Spending tables provide more detail on CSAC’s budget.

Cal Grants

In this section, we first provide background on the Cal Grant program and discuss trends over the past decade. We then discuss the Governor’s cost estimates for the program in the current year and the budget year.

Background

Cal Grant Program Is the State’s Longest‑Standing and Largest Financial Aid Program. The state created the Cal Grant program to increase college access by making college more affordable for California students with financial need. The program gives these students choice in where they attend school, as students can use their Cal Grant award at any of the state’s three public segments, private nonprofit institutions, and private for‑profit institutions. The program began in 1956 with 600 students receiving awards to assist with the cost of college. In 2024‑25, the program served more than 450,000 students and spent $2.5 billion.

Grant Amounts Vary by Award Type and Segment. As Figure 1 shows, there are three types of Cal Grant awards (Cal Grant A, B, and C) that cover certain kinds of college costs. Cal Grant A awards cover full systemwide tuition and fees at public universities and a fixed amount of tuition at private universities. Cal Grant B awards provide the same amount of tuition coverage as Cal Grant A awards in most cases, while also providing an “access award” for nontuition costs such as food and housing. Cal Grant C awards, which are only available to students enrolled in career technical education programs, provide lower amounts of tuition and nontuition coverage. Across all award types, larger amounts of nontuition coverage are available to students with dependent children as well as current and former foster youth. (The Cal Grant Award Coverage table provides more detail.)

Figure 1

Cal Grant Amounts Vary by Award Type,

Sector, and Student Characteristics

Maximum Annual Award for a New, Full‑Time

Undergraduate Student, 2026‑27

|

Tuition Awards |

|

|

Cal Grant A and B |

|

|

UC |

$15,588 |

|

Nonprofit institutions |

9,358 |

|

WASC‑accredited for‑profit institutions |

8,056 |

|

CSU |

6,838 |

|

Other for‑profit institutions |

4,000 |

|

Cal Grant C |

|

|

Private institutions |

$2,462 |

|

Access Awardsa |

|

|

Cal Grant A |

|

|

Students with dependent children |

$6,000 |

|

Foster youth |

6,000 |

|

Cal Grant B |

|

|

Students with dependent children |

$6,000 |

|

Foster youth |

6,000 |

|

Other students |

1,648 |

|

Cal Grant C |

|

|

Students with dependent children |

$4,000 |

|

Foster youth |

4,000 |

|

Other CCC students |

1,094 |

|

Private institution students |

547 |

|

aAccess awards generally may cover any living cost, including housing, food, transportation, books, and supplies. Cal Grant C awards for students attending private institutions may cover only books, supplies, and equipment. Students attending private for‑profit institutions are ineligible for “students with dependent children” and “foster youth” awards. |

|

|

WASC = Western Association of Schools and Colleges. |

|

Cal Grants Have Financial and Academic Eligibility Criteria. Students apply for Cal Grant awards by submitting a Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) or, in certain cases, a California Dream Act Application (CADAA). To qualify for an award, students must demonstrate “financial need,” which, for most students, is determined through a federal calculation using information submitted on the FAFSA. (This financial need calculation is used for many needs‑based financial aid programs across the country.) Students have financial need if their total cost of attendance exceeds their Student Aid Index, which is a proxy for what households can contribute toward college costs. In addition, students must have household income and assets below specified Cal Grant caps. The state uses these caps both to target aid and contain program costs. The income and asset caps vary by family size and are adjusted annually for inflation. In the 2025‑26 award year, the annual household income cap for a dependent student from a family of four is $135,900 to qualify for Cal Grant A or C awards and $71,500 to qualify for Cal Grant B awards. Beyond financial criteria, students must also meet a minimum grade point average (GPA) requirement to qualify for a Cal Grant. The specific GPA requirement varies by award type. Most award types require a minimum high school GPA of 2.0 or 3.0 or a minimum community college GPA of 2.0 or 2.4.

Most Cal Grants Are Entitlements, but Some Are Awarded Competitively. In 2001‑02, the state began guaranteeing Cal Grants to recent high school graduates as well as transfer students under age 28 who met the financial and academic criteria. In 2021‑22, the state began guaranteeing Cal Grants to community college students regardless of their time out of high school or age. In 2024‑25, the state provided a total of approximately 425,000 Cal Grant entitlement awards (consisting of 196,000 new awards and 229,000 renewal awards for continuing students). Besides the entitlement awards, the state has a small number of competitive Cal Grant awards for students who do not qualify for entitlement awards—typically older students who enroll directly at four‑year universities. This program provides a fixed number of new awards (13,000 annually). CSAC uses a scoring system to select students for competitive awards. A student’s score is based on multiple factors, including GPA, household income and size, parental education, and family/environmental indicators (such as students experiencing homelessness).

Trends

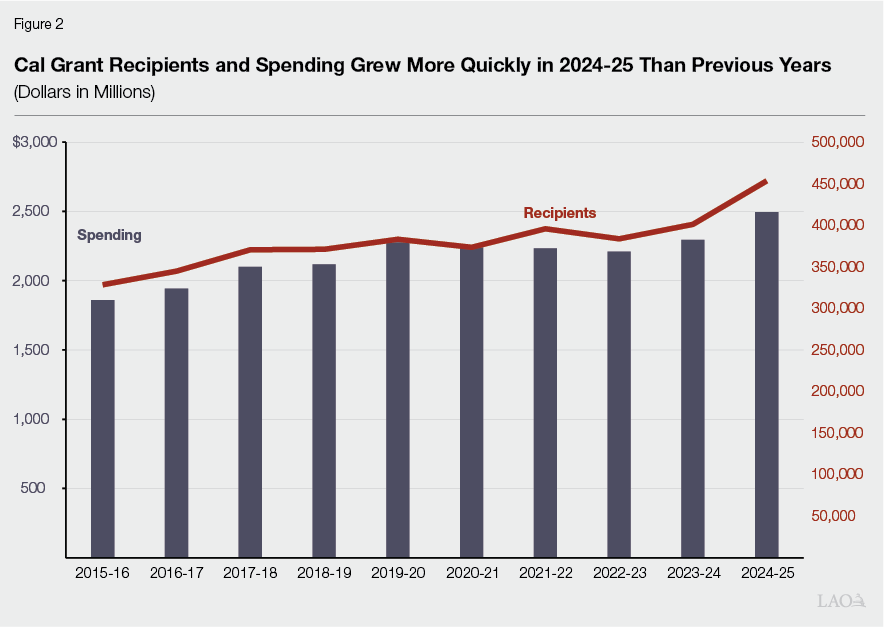

Number of Cal Grant Recipients and Spending Have Been Rising. As Figure 2 shows, the number of Cal Grant recipients and Cal Grant spending have increased over the past decade. The number of recipients grew from approximately 328,000 in 2015‑16 to 453,000 in 2024‑25—a 3.7 percent average annual increase. Spending grew from $1.9 billion to $2.5 billion over the same period—a 3.1 percent average annual increase. Growth in both recipients and spending were particularly high in 2024‑25 (the most recent year of actual data). In 2024‑25, Cal Grant recipients increased by 13 percent and spending increased by 8.7 percent.

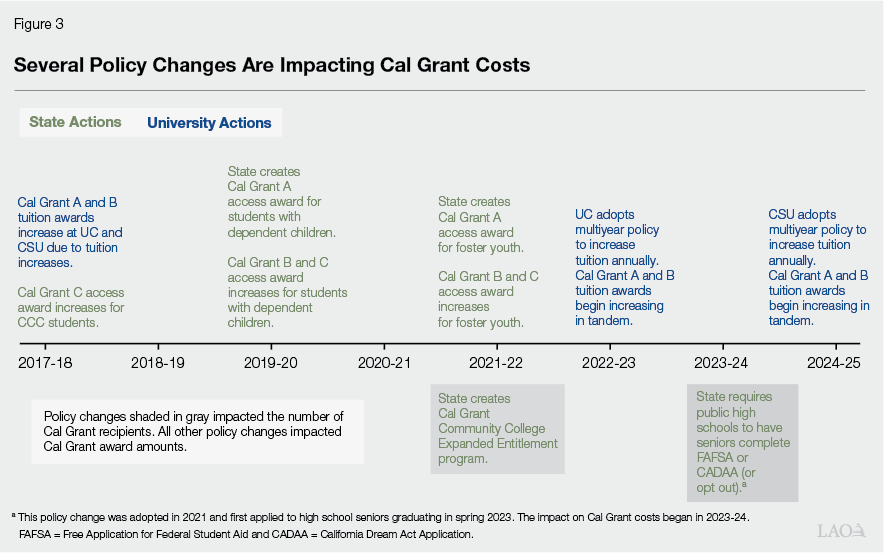

Notable Policy Changes Have Contributed to Higher Cal Grant Costs. As Figure 3 shows, there have been multiple policy changes to the Cal Grant program over the past decade. These changes have increased both award amounts and number of recipients. In most cases, the state directly adopted a policy change, but the universities themselves have adopted tuition increases, which has the effect of increasing award amounts. In the rest of this section, we look at what changes the state and universities have made that are contributing to rising Cal Grant costs. Understanding these underlying factors is important for budget makers, especially as the state faces projected deficits and a structural budget imbalance. This information could help the Legislature this year or in future years as it contemplates how to accommodate growing Cal Grant costs amidst its other budget priorities.

Tuition Increases at UC and CSU Are Resulting in Larger Cal Grant Awards. One reason Cal Grant spending is higher is because students are receiving larger Cal Grant awards. Larger awards are due in part to the tuition increases the University of California (UC) and California State University (CSU) have adopted, which translate directly into higher Cal Grant tuition awards. Both UC and CSU raised tuition for all undergraduates in 2017‑18. Both UC and CSU also have taken action more recently to implement tuition increases. At UC, a new multiyear tuition policy first took effect in 2022‑23, then was revised and extended through 2032‑33. Under both the original and revised UC tuition policies, tuition charges increase annually for new undergraduates (while staying flat for continuing undergraduates for up to six years). Annual increases are tied to a three‑year rolling average of the California Consumer Price Index and capped at 5 percent. The CSU Board of Trustees also recently adopted a multiyear tuition policy. Under CSU’s policy, tuition charges increase 6 percent annually for all students beginning in 2024‑25 and extending through 2028‑29. We estimate that larger Cal Grant awards from UC and CSU tuition increases account for roughly one‑quarter of the growth in Cal Grant costs between 2015‑16 and 2024‑25.

State Also Increased and Expanded Access Awards for Student Parents. In 2019‑20, the state increased the access award amount for students with dependent children from $1,648 to $6,000 for Cal Grant B awards and from $1,094 to $4,000 for Cal Grant C awards. Additionally, that same year, the state created the Cal Grant A access award for students with dependent children. This allowed student parents receiving a Cal Grant A tuition award to also qualify for an access award of $6,000. (Originally, these larger access awards were only available to students at UC, CSU, and CCC but were extended to students at private nonprofit institutions in 2022‑23.) In 2024‑25, approximately 34,000 students with dependent children received access awards (with 3,177 students receiving Cal Grant A awards, 28,433 students receiving Cal Grant B awards, and 2,437 students receiving Cal Grant C awards). In the same year, the state spent $108 million on the new Cal Grant A access awards and higher Cal Grant B and C access awards for students with dependent children.

Similarly, State Increased Access Awards for Foster Youth. As with the access awards for students with dependent children, in 2021‑22, the state increased the access awards for current and former foster youth students from $1,648 to $6,000 for Cal Grant B awards and from $1,094 to $4,000 for Cal Grant C awards. The state also made foster youth eligible for the Cal Grant A access award of $6,000. (While originally available only to foster youth at UC, CSU, and CCC, these awards were extended to foster youth at private nonprofit institutions in 2022‑23.) In 2024‑25, approximately 4,000 foster youth students received a Cal Grant access award with an associated cost of $14 million.

Cal Grant Eligibility Increased Substantially With Creation of CCC Expanded Entitlement Program. Beyond Cal Grant awards becoming larger, Cal Grant spending also has increased due to more recipients. Some of the growth in recipients is due to the state creating the CCC Expanded Entitlement program in 2021‑22. Prior to this program, students were eligible for a Cal Grant entitlement award if they had just graduated high school or were one year out of high school (under the High School Entitlement program). These students could use their award at CCC, UC, CSU, or private institutions. Students who were a few years out of high school and under age 28 were also eligible for a Cal Grant entitlement award once they transferred from CCC to UC, CSU, or private institutions (under the Transfer Entitlement program). All students age 28 or older were ineligible for Cal Grant entitlement awards, though they could apply for a fixed number of competitive awards. The CCC Expanded Entitlement program expanded Cal Grant eligibility by (1) allowing students to receive a Cal Grant entitlement award at CCC regardless of how many years they had been out of high school and (2) allowing students of any age to keep their Cal Grant entitlement award upon transferring from CCC to UC or CSU. These two eligibility expansions have resulted in a considerable increase in Cal Grant recipients.

CCC Expanded Entitlement Program Is Large Contributor to Higher Cal Grant Spending. In 2024‑25, an estimated approximately 157,000 students are receiving Cal Grant awards under the CCC Expanded Entitlement program, accounting for 35 percent of all Cal Grant recipients that year. Since the program’s inception, associated costs have increased considerably each year—rising from $82 million in 2021‑22 to $335 million in 2024‑25. The continuing annual growth in program spending is likely due to it not yet having reached full implementation, as the number of program recipients transferring their awards to UC and CSU is continuing to increase. Of the $335 million in spending in 2024‑25, we estimate that about half would have occurred under the Transfer Entitlement and Competitive programs. The remainder, however, would not have occurred absent the policy change.

FAFSA Requirement for California High School Seniors Also Is Likely Impacting Cal Grant Costs. Starting with the 2023‑24 financial aid cycle (spring 2023 high school graduates), the state required local educational agencies to confirm all graduating high school seniors complete and submit the FAFSA or CADAA (or opt out). According to a PPIC report, during the 2023‑24 financial aid cycle, the number of FAFSA and CADAA applications submitted by high school graduates increased by 16 percent for the UC/CSU deadline (March 2, 2023) and by 11 percent for the CCC deadline (September 2, 2023). Additionally, the report found that the largest increase in applications was from the state’s lowest‑income students. Unlike the CCC Expanded Entitlement Program, this policy change did not make more students eligible for Cal Grants. However, the increase in high school students completing the FAFSA and CADAA, especially those from low‑income families, likely is still increasing the number of Cal Grant recipients and spending. This is because eligible Cal Grant students who may not have previously applied for financial aid are now applying. The number of recipients for Cal Grant High School Entitlement awards increased by 1.3 percent in 2023‑24 and by 5.6 percent in 2024‑25.

Bulk of Cal Grant Growth Over the Past Decade Is Attributable to Policy Changes. From 2015‑16 to 2024‑25, Cal Grant spending increased by $636 million. We estimate roughly half of this growth is due to larger Cal Grant award amounts, including the tuition increases at UC and CSU and changes relating to access awards for students with dependent children and foster youth. We estimate that about one‑quarter of this growth is attributable to more students being eligible for a Cal Grant award under the CCC Expanded Entitlement program. The remainder of the increase in spending is primarily driven by underlying Cal Grant caseload growth at UC and CSU.

Governor’s Budget Cost Estimates

Current‑Year Cal Grant Spending Revised Upward. The Governor’s budget adjusts 2025‑26 Cal Grant spending upward by $107 million (3.8 percent) to align with CSAC’s most recent cost estimates. Since budget enactment, spending is coming in higher than budgeted in all program areas (except for competitive awards), with the largest increases in the High School Entitlement and CCC Expanded Entitlement programs. Higher spending in the High School Entitlement program is due to an 8.1 percent increase in the expected number of recipients. For the CCC Expanded Entitlement program, higher spending is particularly concentrated at CSU (due to more recipients transferring to CSU and their average awards increasing).

Governor’s Budget Reflects Further Spending Increases in 2026‑27. The Governor does not propose any further Cal Grant policy expansions, but the proposed budget covers higher anticipated Cal Grant costs in 2026‑27. Specifically, the Governor’s budget provides a $337 million (12 percent) ongoing General Fund augmentation (over the revised 2025‑26 spending level). Figure 4 summarizes the projected changes for 2026‑27 by segment and award type. The higher spending reflects a 9.1 percent projected increase in recipients and a 2.3 percent projected increase in average Cal Grant award amounts, primarily due to UC’s and CSU’s planned tuition increases. (Under CSAC’s estimates, $65 million of the Cal Grant spending increase in 2026‑27 is attributable to covering higher tuition costs at UC and CSU.)

Figure 4

Cal Grant Spending Is Estimated to Be Up 12 Percent in 2026‑27

Reflects Cost Estimates in Governor’s Budget (Dollars in Millions)

|

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

Change From 2025‑26 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Totals |

$2,496 |

$2,898 |

$3,235 |

$337 |

11.6% |

|

By Segment: |

|||||

|

California Community Colleges |

$1,082 |

$1,232 |

$1,365 |

$133 |

10.8% |

|

California State University |

844 |

1,026 |

1,188 |

161 |

15.7 |

|

University of California |

315 |

362 |

388 |

26 |

7.3 |

|

Private nonprofit institutions |

228 |

247 |

261 |

14 |

5.8 |

|

Private for‑profit institutions |

25 |

30 |

33 |

2 |

7.3 |

|

Other public institutions |

1 |

1 |

—a |

—a |

‑63.7 |

|

By Program: |

|||||

|

High School Entitlement |

$1,762 |

$2,044 |

$2,317 |

$273 |

13.4% |

|

CCC Expanded Entitlement |

426 |

515 |

562 |

46 |

9.0 |

|

Competitive |

148 |

150 |

155 |

5 |

3.2 |

|

Transfer Entitlement |

145 |

167 |

180 |

12 |

7.4 |

|

Cal Grant C |

16 |

21 |

22 |

1 |

4.6 |

|

By Award Type: |

|||||

|

Cal Grant B |

$1,170 |

$1,379 |

$1,558 |

$179 |

13.0% |

|

Cal Grant A |

1,310 |

1,498 |

1,656 |

157 |

10.5 |

|

Cal Grant C |

16 |

21 |

22 |

1 |

4.6 |

|

By Renewal or New: |

|||||

|

Renewal |

$1,662 |

$1,940 |

$2,219 |

$279 |

14.4% |

|

New |

834 |

958 |

1,016 |

58 |

6.1 |

|

aLess than $500,000. |

|||||

|

Notes: Data reflect California Student Aid Commission estimates. |

|||||

Cost Estimates Will Be Updated at May Revision. CSAC prepared the Cal Grant cost estimates underlying the Governor’s budget in October 2025. In the spring, CSAC plans to update its estimates based on more recent program data for the 2025‑26 award cycle. The administration is expected to update its Cal Grant spending levels at the May Revision accordingly. Given the projected out‑year deficits, covering existing Cal Grant costs could be challenging even if estimates come in lower in May. As a result, the state will likely not have the capacity for further program expansion over the next few years.

Middle Class Scholarships

In this section, we first provide background on the MCS program and discuss program trends. We then describe the Governor’s proposal for 2026‑27 awards, assess the proposal, and provide two associated recommendations.

Background

Original MCS Program Covered Partial Tuition Costs for Higher‑Income Students. During the Great Recession, UC and CSU notably raised tuition, partly in response to declines in state funding. Cal Grants generally covered these tuition increases for students from low‑ and middle‑income households. In 2013, the Legislature created the original MCS program to provide partial tuition coverage for higher‑income UC and CSU students who generally did not qualify for tuition assistance under the Cal Grant program. First implemented in 2014‑15, students with household incomes of up to $100,000 could have 40 percent of their tuition covered (when combined with all other public financial aid). Tuition coverage was graduated downward as household income rose, with students receiving 10 percent tuition coverage at $150,000.

Original MCS Program Did Not Require Students to Demonstrate Financial Need. Whereas most federal and state financial aid programs require undergraduates to demonstrate financial need, the original MCS program did not. To be eligible for MCS awards, students only had to have household income and assets under specified program caps. These income and asset caps were adjusted annually for inflation. They did not vary by family size. State law capped spending for the original MCS program at $117 million annually and directed CSAC to prorate award amounts to remain under the cap, if needed.

Revamped MCS Program Retained a Few Key Aspects of Original Program. In 2021, the state adopted legislation revamping the MCS program, with implementation beginning in the 2022‑23 academic year. Under the revamped program, students still do not have to demonstrate financial need. Moreover, students still are subject to the original income and asset cap rules. In 2025‑26, the maximum annual household income for dependent students to qualify for an MCS award is $234,000. This income level equates to roughly the top 90th percentile of households in California (meaning only about one in ten households makes above that level). Lastly, under the revamped program, students at private universities remain ineligible for MCS awards.

Revamped MCS Program Contains Two Key Policy Changes. One major change was shifting from focusing only on tuition coverage to focusing on a student’s total cost of attendance. Under the revamped program, students may use their MCS awards for tuition or nontuition expenses, such as housing and food. A second major change was expanding eligibility to students receiving Cal Grant awards. For Cal Grant recipients (who already have their tuition, and, in some cases, a portion of their nontuition costs covered), MCS provides additional aid for nontuition costs. Though less notable given relative magnitude, the revamped program also expanded eligibility to CCC students in bachelor’s degree programs.

Revamped MCS Award Calculation Is More Complex. Calculating each student’s award amount involves several steps. Starting with a student’s total cost of attendance, CSAC deducts the student’s available resources, consisting of other need‑based and non‑need‑based gift aid. The formula also deducts a student contribution from part‑time work earnings. Specifically, the MCS calculation assumes a student works 15 hours per week, 39 weeks per year, at the state minimum wage rate, as adjusted annually. For dependent students with household incomes of more than $100,000, the MCS calculation also deducts a parent contribution. This parent contribution is one‑third of the expected parent contribution calculated according to the federal student aid index methodology. After making all of these deductions, this formula derives the student’s remaining costs. (Page 19 of this CSAC MCS 2024‑25 handbook shows illustrative MCS award amounts for students at different segments with different levels of financial means.)

MCS Award Coverage Has Been Determined in Two Ways. Under the revamped program, every student receives the same percentage of their remaining costs covered (except foster youth, who receive awards that cover 100 percent of their remaining costs). From 2022‑23 through 2024‑25, CSAC determined what percentage of each student’s remaining costs to cover based on the annual MCS appropriation. In 2022‑23, award coverage was 26 percent, followed by 36 percent in 2023‑24, and 35 percent in 2024‑25. Using this approach, CSAC could not finalize the percentage of award coverage until August when it received enrollment rosters from campuses. This issue made it challenging for campuses to inform students of their estimated MCS award amounts prior to the start of the academic year. As a result, students often did not know their full financial aid package prior to the start of the academic year. To help mitigate this issue, in 2025‑26, rather than setting the appropriation for MCS and adjusting award coverage accordingly, the state locked in the percentage of award coverage that year at 35 percent. The state is now responsible for covering whatever is the associated cost.

Last Year, State Began Funding Program in Arrears. The state also adopted a new budgetary approach for the MCS program last year. Under the new budgetary approach, the state began funding the MCS program one year in arrears. As a result, the state will pay for the cost of MCS awards for the 2025‑26 academic year in 2026‑27. The state is covering costs in 2025‑26 using a General Fund loan.

Trends

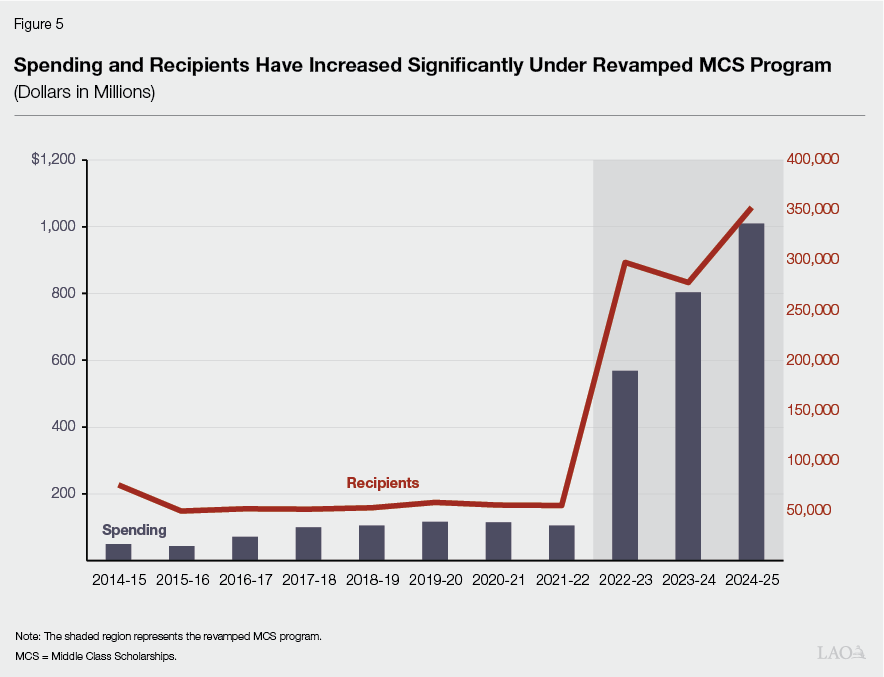

MCS Recipients and Costs Increased Substantially Under Revamped Program. As Figure 5 shows, the revamped program resulted in a sharp increase in the number of MCS recipients and the amount of spending. For the eight years in which the state implemented the original MCS program, the program gave awards to an average of about 56,000 recipients each year. The state appropriated approximately $100 million annually over this period. In 2024‑25 (three years into the revamped program), the program gave awards to more than 350,000 recipients—about a seven‑fold increase. In 2024‑25, the state provided $1 billion General Fund for the MCS program—reflecting about a ten‑fold increase.

Increase in MCS Spending Stems Primarily From Expanding Eligibility to Cal Grant Recipients. In 2024‑25, about 190,000 (55 percent) MCS recipients were also Cal Grant recipients (that is, students who were not eligible for awards under the original program). These recipients account for roughly 80 percent of the increase in MCS spending. Though much of the increase in MCS recipients under the revamped program is due to expanded eligibility, some is due to higher enrollment at UC and CSU. Specifically, from 2021‑22 (the year before MCS was revamped) to 2024‑25, resident undergraduate enrollment increased by 7.5 percent and 2.1 percent at UC and CSU, respectively.

Average MCS Award Amount Increased by About Half Between Original and Revamped Program. Across all MCS recipients, the average MCS award in 2024‑25 was $3,673—50 percent higher than in 2021‑22. In 2024‑25, the average MCS award for CSU students was 70 percent higher than it had been under the original program. By comparison, the average MCS award for UC students was slightly lower than under the original program. These changes in average award amounts are due to switching the program from partial tuition coverage to a share of remaining cost of attendance.

Proposal

Governor Proposes Reducing Award Coverage to 17.5 Percent in 2026‑27. The Governor’s budget reduces MCS award coverage by half—from 35 percent to 17.5 percent—for the 2026‑27 award year. This is the only proposed higher education budget solution. The solution does not come with any associated new out‑year obligations (unlike certain other solutions that effectively push out costs). The proposed funding level is $513 million ongoing General Fund. The reduction in award coverage would decrease MCS spending by $541 million, resulting in a like amount of General Fund savings. The administration scores the $541 million as one‑time savings. (For the past three years, the state has supported the program using a mix of ongoing and one‑time General Fund.) The Governor’s budget maintains the new budgetary approach of funding MCS awards one year in arrears. Given this budgetary approach, the state would not achieve the identified one‑time General Fund savings until 2027‑28.

Assessment

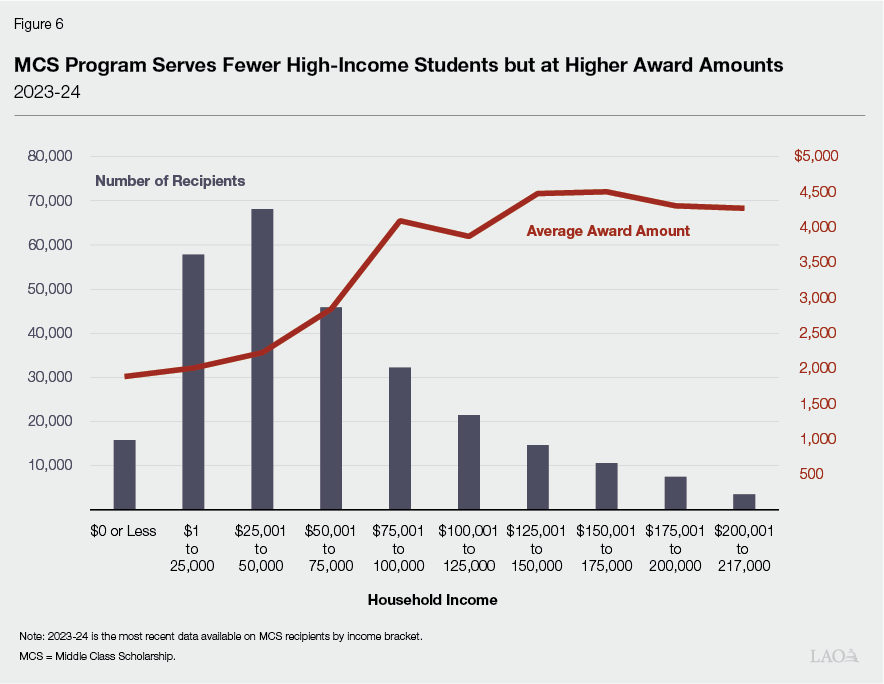

Impact of Reducing Award Coverage Would Vary Among Students. At the proposed award coverage of 17.5 percent, the average MCS award amount is expected to decrease by about half. Our office estimates the average award in 2026‑27 would be $1,432 at CSU, $1,586 at UC, and $2,198 at CCC. Estimating the impact of lower MCS awards is difficult given the specific impact will depend on each student’s unique financial situation. On the one hand, students with higher MCS awards may be more sensitive to the reduction than students with smaller MCS awards. On the other hand, as Figure 6 shows, students with higher awards are likely to be from households with higher incomes. These students tend to receive less gift aid, resulting in larger MCS awards than students from lower‑income households. Higher‑income students may be less affected by a reduction to their MCS awards because they have more financial resources to substitute the loss in award amount. Though the impact of the award reduction will be felt differently among students, students might work a couple more hours per week or take out larger loans to compensate for smaller MCS awards.

Program Has Considerable Overlap With Cal Grant Program. When MCS was originally created, it was targeted to help moderate‑income students who did not receive Cal Grants cover tuition costs. Thus, the original MCS program was intended to have little, if any, overlap with the Cal Grant program. When the MCS program was revamped in 2022‑23 and eligibility was extended to Cal Grant recipients, program overlap became notable. In 2024‑25, 55 percent of MCS recipients also received a Cal Grant award. This creates multiple inefficiencies. It leads to higher administrative costs for the state as it is administering two financial aid programs that are serving much of the same population. Similarly, campuses must administer two programs and issue two different awards to many of the same students. Lastly, students receive two different awards for largely the same purpose (and they might not understand the distinction between the awards). As the Legislature prepares for potential out‑year deficits, it likely will want to begin identifying where efficiencies can be achieved and duplicative or overlapping programs can be streamlined.

MCS Does Not Target Aid Based on Financial Need. Requiring financial need criteria to be met has long been used by governments to target assistance to those most likely to benefit from it. In contrast, MCS does not have a financial need eligibility component, and its income and asset thresholds are much higher than those the Cal Grant program uses. As a result, the program is less targeted to lower‑income students. Lower‑income students, however, are the ones least likely to be able to attend and complete college without financial support.

Program Is More Challenging to Convey and Administer Than Other State Aid Programs. Unlike other state financial aid programs, MCS is not a set award amount. Additionally, as a “last‑dollar‑in” program, the award amount is subject to variability as long as any component of the formula still could potentially change. This makes it challenging for students and families to plan ahead, as they will likely not know the award amount prior to the start of the academic year. As a result, the impact of the program on a student’s decision to attend college may be limited. The complex and multicomponent nature of the MCS formula also makes it more cumbersome for campuses to administer than other financial aid programs.

Funding Program in Arrears Could Put State in Challenging Budget Situation. Under the new budgetary approach for the program, the state is providing MCS awards to students in one year but paying for those awards a year later. To do so, the state is using a General Fund cash loan to cover the payments to students. This approach only works if the state is in a strong cash position. If the state’s cash position weakens, which has happened during previous fiscal downturns, the state could find that internal borrowing is no longer an option. In this situation, the state might decide to turn to external borrowing. Such borrowing would come with interest, resulting in higher program costs at a time when the state has fewer budgetary resources. In turn, the impact on the rest of the budget would be exacerbated. Paying for awards in the year the costs are incurred would mitigate this situation, as the state would not have to rely on borrowing to cover annual program costs.

Recommendations

Consider Adopting Proposal to Reduce MCS Award Amounts Given Projected Budget Deficits. Both our office and the administration are projecting notable out‑year budget deficits. The Governor’s budget, however, has only one proposed budget solution in the higher education area addressing these deficits. Given the state’s fiscal outlook, the Legislature likely will need to consider not only this MCS proposal but many other budget‑balancing proposals over the next couple of years. Given the MCS program has significant overlap with the Cal Grant program, is less targeted to lower‑income students, and is more complex to convey and administer than other financial aid programs, reducing MCS award coverage could be among the least disruptive choices the Legislature faces.

Consider Funding Program Using More Standard Budget Practice. Paying for MCS costs one year in arrears effectively creates a debt obligation for the state. Once one‑time funding becomes available, we recommend the Legislature give high priority to retiring this debt. We recommend the state return to paying for MCS the way it pays for other state programs—in the year in which the costs are generated. Even funding MCS in the traditional way, the state could still set the award coverage percentage for each award year. Setting award coverage would provide greater clarity to campuses and students. As it does with other state programs, the state could budget based on an estimate of MCS program costs for the coming fiscal year. It could then allow CSAC to access a small loan towards the end of the fiscal year if the budget appropriation falls short of covering program costs. The state could then true up the actual cost the following year. This would be similar to how the Cal Grant program is funded.