2013

Other Budget Issues

| Last Updated: | 5/18/2013 |

| Budget Issue: | Analysis of the Governor's CalWORKs Early Engagement Proposal |

| Program: | CalWORKs |

| Finding or Recommendation: | Adopt the Governor's proposal, with several modifications. |

Further Detail

Analysis of the Governor’s CalWORKs Early Engagement Proposal

The California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) program provides cash assistance and welfare-to-work services to families whose income is insufficient to meet their basic needs. In the May Revision to the 2013-14 Governor’s Budget, the Governor proposes to make changes to welfare-to-work processes in the early stages of CalWORKs participants’ involvement with the program in an effort to improve participant engagement. (The concept of improving the effectiveness of the initial welfare-to-work experience is known informally as early engagement.) The proposal drives off of policy changes approved by the Legislature in the 2012-13 budget and is an attempt to more fully achieve the benefits of those changes. The Governor also proposes to significantly expand CalWORKs subsidized employment. We find that the proposal merits serious consideration by the Legislature, but also raise several issues related to implementation. We recommend that the Legislature adopt the proposal with several modifications.

Background

The 2012-13 Budget Resulted in Significant Changes to CalWORKs

Chapter 47, Statutes of 2012 (SB 1041, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), implemented changes in human services programs that were made necessary by the 2012-13 Budget Act. Chapter 47 included major changes to the CalWORKs program.

Introduction of Welfare-to-Work 24-Month Time Clock Restricted Adult Eligibility, But Broadened Flexibility in Work Participation Rules. The most significant of the CalWORKs changes included in Chapter 47 was the introduction, beginning January 2013, of a new prospective 24-month limit on adult eligibility for assistance under state work participation rules. Able-bodied adults may continue to receive cash assistance and services after the 24 months have been exhausted, but only if they comply with federal work participation rules. Federal rules are more restrictive than state rules and place a heavier emphasis on employment, as opposed to education, training, or barrier-removal activities. Barrier-removal activities are intended to address recipient characteristics or situations such as low English proficiency, limited educational attainment, substance abuse, poor mental health, and domestic violence. At the same time, Chapter 47 altered state work participation rules to make them more flexible than they were previously. This new flexibility is intended to help CalWORKs families overcome barriers and find employment that would allow them to either (1) earn sufficient income to leave the program or (2) become compliant with federal work rules and continue to receive aid for an additional 24 months (up to the maximum 48-month adult time limit on aid). For more information on the implementation of the welfare-to-work 24-month time clock, refer to our February report, The 2013-14 Budget: Analysis of the Health and Human Services Budget.

Stakeholder Workgroup Formed to Identify Best Practices to Improve Early Engagement. Chapter 47 also required the Department of Social Services (DSS) to convene a stakeholder workgroup that would examine strategies to make the initial months of welfare-to-work participation as meaningful as possible. Such strategies would ideally result in a greater number of CalWORKs recipients beneficially taking advantage of the flexible 24-month period (as opposed to becoming sanctioned due to noncompliance) and transitioning successfully either to compliance with federal work rules or out of the program (due to exceeding the program’s income requirements). Chapter 47 specifically recommended that the workgroup examine the existing flow of welfare-to-work processes in the program’s early stages, as well as the program rules and activities that apply in later stages of welfare-to-work participation. The DSS was to report to the Legislature by January 10, 2013 on the recommendations of the workgroup and how these recommendations could be implemented. The workgroup met from November 2012 through February 2013, and in April, DSS submitted a draft concept sheet in fulfillment of the reporting requirement (albeit late). That concept sheet forms the basis of the May Revision early engagement proposal.

State Law Outlines General Welfare-to-Work Flow

The sequence of events that CalWORKs recipients experience in the initial stages of welfare-to-work is defined in state law. The main steps are as follows:

- Orientation and Appraisal.Welfare-to-work participants first receive an orientation to the welfare-to-work program that describes participants’ rights and responsibilities and services that are available. Orientation is followed by an appraisal. The purpose of the appraisal is to gather information about the participant’s employment history, skills, and need for supportive services (including child care and help with transportation and other expenses).

- Job Search and Job Readiness.Following appraisal, participants engage in up to four consecutive weeks of job search activities. In addition to searching for employment, job search activities can include job readiness activities intended to prepare participants to find work. State law provides that the required period of job search may be shortened if it is determined that job search is not beneficial. Regulations further clarify that participants may forego job search entirely if it is determined to not be beneficial.

- Assessment and Development of Welfare-to-Work Plan.If a participant does not find employment through job search activities, or does not participate in job search activities because it was determined not to be beneficial, state law directs that an assessment should take place. The assessment, while similar in some ways to the initial appraisal, is more comprehensive and leads to the selection of the welfare-to-work activities (including, in some cases, barrier removal activities) that will become part of a welfare-to-work plan that directs the participant’s activities going forward.

Counties Vary in Their Implementation of the Welfare-to-Work Flow. Although the state is responsible for policy making and oversight, counties administer CalWORKs and have flexibility in the implementation of certain aspects of the program, including the initial welfare-to-work flow. Some counties closely follow the default flow described in state law, while others have adjusted the basic flow to meet local needs, using the flexibility that state law affords. All counties have built upon the basic flow in individualized ways. For example, counties differ with respect to determining when job search is beneficial or when participants should move directly to assessment. Counties use different processes to identify barriers to employment. Some use paper-based questionnaires to screen for substance abuse, mental health, and domestic violence issues as part of the initial appraisal, while others require that all participants have an individual discussion with a trained social worker to identify these issues.

Subsidized Employment’s Role Has Changed Over Time

Subsidized employment is a welfare-to-work activity that consists of an employment arrangement in which part or all of an employer’s wage and training costs associated with employing a CalWORKs recipient are reimbursed by the county. Subsidized employment positions can be with private employers or in public agencies and generally last for six months, but can be extended to one year at county option. Not all counties choose to offer subsidized employment and its role in the welfare-to-work program has fluctuated over time as the state has altered its approach to how the subsidized positions are financed.

Partial State Reimbursement of Wage Subsidy Established Under AB 98. Chapter 589, Statutes of 2007 (AB 98, Niello), established a structure (referred to as AB 98) under which the state would reimburse counties for 50 percent of the wage subsidy paid to the employer, up to 50 percent of a participant’s grant. Assembly Bill 98 forms the basis of CalWORKs subsidized employment as it exists today. Around the time AB 98 was initially implemented, there were approximately 1,000 subsidized positions in the state and relatively few counties participated.

Subsidized Employment Dramatically Expanded Under Federal Stimulus Funding. Shortly after AB 98 was enacted, subsidized employment changed again due to new federal policy. As part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009, the state received $423 million from August 2009 through September 2010 to fund subsidized positions for CalWORKs participants and other low-income individuals. These positions were generally funded fully with federal funds, with employers expected to make a 20 percent contribution (generally in kind).While federal funding was available, the state reimbursement under AB 98 was suspended. Subsidized employment expanded dramatically during this period, to approximately 36,000 positions (about 7,000 positions CalWORKs participants) at the peak, with most counties participating.

Maximum State Reimbursement Under AB 98 Subsequently Increased. After federal funding under ARRA ended in 2010, state reimbursement under AB 98 was reinstated and the number of subsidized employment positions fell. The AB 98 reimbursement structure was subsequently modified by Chapter 8, Statutes of 2011 (SB 72, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), to allow counties to claim up to 50 percent of total wages, and to increase the maximum reimbursement to the amount of the participant’s entire grant. An income disregard was also added to the reimbursement calculation that made the reimbursement budget neutral, meaning that state reimbursements are offset by decreases in the grants received by participants. As of July 2012, there were over 2,000 subsidized positions in CalWORKs throughout the state.

The Governor’s Proposal

In the May Revision, the Governor proposes changes to CalWORKs related to three concepts discussed by the early engagement workgroup: (1) creating a more comprehensive and robust appraisal process, (2) providing additional case management for families experiencing crisis situations, and (3) enhancing and expanding subsidized employment.

Robust Appraisal—$9.4 Million. The Governor proposes to make the up-front appraisal more comprehensive by introducing a new appraisal tool. This tool would be customized by the state to include components designed to more effectively identify barriers to employment. This in turn would allow case workers to connect participants with the existing barrier removal services and welfare-to-work activities that best align with their needs. The administration has indicated that it currently plans acquire the Online Work Readiness Assessment (OWRA) tool, which was developed by the federal government and is available to states free of charge. The OWRA tool is a web-based application that can be used for a variety of functions relevant to the proposal, including gathering recipient background information, identifying barriers to employment, and constructing appropriate plans based on this information. Additionally, OWRA is designed to track and report data on recipients’ barriers and how these barriers are addressed. The tool is customizable and is intended to be modified to include whatever screening tools and processes a state wishes to use, as well as integrate with existing systems if needed.

Under the Governor’s proposal, DSS would acquire the tool in July and begin modifying it to fit state needs. Once modified, county workers would be trained on the use of the tool. Customization and training would be completed by January 1, 2014, at which point the tool would be rolled out in all 58 counties. The May Revision includes one-time automation costs of $600,000 (General Fund) and one-time training costs of $2.2 million (General Fund). Once the tool is rolled out, the May Revision assumes that counties will spend one hour with new participants using the tool, at a cost of $6.6 million in 2013-14. Funding for added caseworker time would be provided through the county employment services portion of the CalWORKs single allocation. The total cost in 2013-14 for the robust appraisal portion of the proposal would be $9.4 million.

Family Stabilization—$10.8 Million. To further adapt the up-front welfare-to-work experience to the needs of participants, the Governor proposes a new approach for assisting families that are experiencing an acute crisis situations (such as homelessness or severe and immediate substance abuse, mental health challenges, or domestic violence). This approach would involve creating “stabilization plans” that would focus directly on stabilizing family needs by providing services that are already available under state law and that would be accompanied by more intensive case management. The May Revision assumes that initially the number of participants requiring a stabilization plan will roughly equal the number of cases estimated to use substance abuse, mental health, and domestic violence services, but that this number will increase somewhat over time as the new appraisal tool becomes more fully and effectively utilized. The May Revision would provide counties with an additional $10.8 million in the employment services component of the single allocation in 2013-14 to allow for additional caseworker contact and follow-up with these participants.

Enhanced Subsidized Employment—$28.1 Million. The Governor proposes to substantially increase the role of subsidized employment by building on the state’s experience with federal ARRA funding. The proposal would establish a fixed number of subsidized employment positions that would be fully funded by the state, representing significantly greater state support than is currently available under AB 98. The amount of funding assumed per position was derived from past experience under ARRA funding, and includes participant wages, payroll taxes, employer non-wage costs, and additional county funding to manage relationships with employers and to support participants. The May Revision assumes that initially 250 enhanced subsidized employment positions would be available beginning in November 2013, eventually increasing to 8,250 positions in June 2014. After accounting for state savings resulting from a decrease in participants’ grants (due to increased earned income), the proposal would result in General Fund costs in 2013-14 of $28.1 million.

The administration has also submitted trailer bill language to implement enhanced subsidized employment. This language anticipates that the enhanced subsidized employment positions would be distributed among counties through a process developed collaboratively with the County Welfare Directors Association. The proposal would also change state law to require that counties accepting additional funding for enhanced subsidized employment would be required to maintain their current level of expenditure on AB 98 subsidized employment. This is intended to ensure that the enhanced positions do not displace existing AB 98 positions.

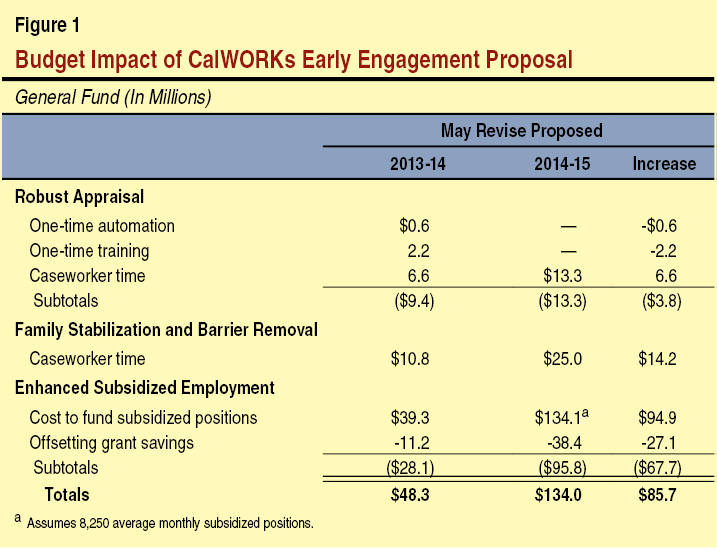

Administration’s Estimate Of Full-Year Costs—$134 Million. Each of the components of the early engagement proposal is phased in over 2013-14. As a result, ongoing costs to maintain the proposed changes will be different than what is estimated for the 2013-14, as shown in Figure 1. Specifically, if the proposal were implemented without modification, costs in 2014-15 as estimated by the administration would be $13.3 million for robust appraisal, $25 million for family stabilization, and $95.8 million for enhanced subsidized employment (assuming an average of 8,250 positions per month and reflecting offsetting grant savings), for a total of $134 million.

LAO Assessment

The Governor’s proposal has merit and warrants serious consideration. The proposal constructively builds on the work of the early engagement workgroup and we believe that it could result in improved services for CalWORKs recipients. However, the proposal also raises some concerns. In general, the proposal lacks needed detail on county implementation. Several important decisions about how the proposal would be implemented would be left either to the administration or to individual counties, and we think these decisions warrant legislative input. The proposal, in its current form, also does not adequately provide for data collection and reporting that would be valuable to the Legislature for oversight and policy making purposes. Finally, while the expansion of subsidized employment does have its policy merits, we believe it would be appropriate to approach the creation of fully state-funded subsidized positions more cautiously by limiting the expansion proposed by the Governor until there is more conclusive evidence on the long-term effectiveness of this welfare-to-work activity.

Robust Appraisal

New Appraisal Tool Would Likely Lead to Improved Barrier Identification… Appraisals and assessments are an important component of addressing barriers to sustainable employment. However, reliably identifying these barriers can be challenging. Research indicates that recipients with barriers often fail to self-identify issues that could be addressed through services provided by the program. Passive, questionnaire-based appraisals, a somewhat common method of barrier identification, have been shown to be relatively less effective. Rather, specialized clinical assessments performed by trained professionals have been shown to be a more effective method of diagnosing and addressing barriers. It would likely be cost-prohibitive for every CalWORKs participant to undergo a clinical assessment for all possible barriers. One option is to use validated screening tools administered by caseworkers. This is a promising way to identify individuals with a high risk of having a barrier and who would be good candidates for a more comprehensive clinical assessment. County processes currently operate by referring recipients with suspected or self-reported barriers to a clinical assessment. We believe that adopting a new appraisal tool that contains validated screening tools and is administered by caseworkers as proposed in the May Revision would likely increased counties’ ability to identify barriers to employment.

Furthermore, making the appraisal more comprehensive is promising because the appraisal occurs early in the welfare-to-work experience. Earlier identification of barriers could lead to more recipients receiving services to address barriers that, if not addressed, could lead to sanctions and disengagement with the welfare-to-work program. Adopting the tool would also result in increased uniformity of appraisals throughout the state. While county variation is beneficial in some aspects of the CalWORKs program, we believe that it makes sense for all participants to have a similar experience with the appraisal process, since the same barriers are likely to occur to some degree in all areas of the state.

…But May Not by Itself Result in More Productive Activity Assignments. The CalWORKs program was created with a work-first focus, and the welfare-to-work flow outlined in state law, which emphasizes job search following appraisal, is consistent with this policy. State law that defines the purpose and features of the appraisal and specifies the welfare-to-work flow has not substantially been altered since the initial implementation of CalWORKs. A substantial body of research suggests that work-first approaches are generally at least as effective as education-and-training-first approaches at increasing employment and earnings of welfare recipients. More recent research additionally concludes that a mixed approach, which encourages recipients to enter either work or work-focused training based on individual characteristics, can potentially be more effective than either work-first or education-and-training-first approaches. In practice, the CalWORKs program generally reflects a type of mixed approach, in light of the flexibility afforded to counties in implementing the welfare-to-work flow. The added flexibility in work rules that was created in conjunction with the welfare-to-work 24-month time clock further appears to represent a state-level policy of a mixed approach. However, since state law that defines the welfare-to-work flow continues to reflect a more uniformly work-first approach, we are concerned that the state is sending a mixed message about its policy in this regard. This may prevent the robust appraisal tool from being used as effective as it could be because some counties, administrators, and workers may not use the results of the appraisal in a way consistent with the flexibility intended under the changes adopted by the Legislature in the prior-year budget.

Analyst’s Recommendation. The administration is not proposing trailer bill language to implement the aspect of its proposal dealing with robust appraisals. In light of the concern raised above, we recommend that the Legislature update state law that defines the appraisal in particular, and the up-front welfare-to-work flow in general, to better reflect and be internally consistent with the flexibility inherent in recent statutory changes establishing the 24-month time clock. For example, language could be adopted to redefine the appraisal as a robust, comprehensive process that uses a statewide tool in order to determine the welfare-to-work flow on a more individualized basis. Language could also be adopted that would clarify that if job search activities were determined to not be beneficial for a participant, job search could be bypassed altogether, instead of just shortened. It might also be necessary to examine how the appraisal and subsequent assessment relate to one another and whether changes to the definition of assessment might be beneficial as well.

Development of Robust Appraisal Tool Presents Valuable Opportunity for Data Collection. As noted previously, the OWRA tool includes data collection and reporting capabilities. As far as we are aware, the state currently does not collect data on the incidence of various barriers to employment and what services are provided to address these barriers. Information about which barriers are most prevalent and the counties’ collective response to these barriers would be very valuable in making future policy decisions and improvements in the CalWORKs program. Such data collection could likely be facilitated by integration with existing county automated welfare systems. However, it is unlikely that plans for data collection and system integration could be developed and adequately executed in the proposed six-month rollout period.

Analyst’s Recommendation. In order to start achieving the benefits to CalWORKs participants from a more robust appraisal process, we recommend that the Legislature adopt the administration’s proposal to roll out the appraisal tool by January 1, 2014. However, we further recommend that the Legislature require DSS to report at hearings on the 2014-15 budget on what steps could be taken to upgrade the appraisal tool to have increased integration with county welfare automation systems (as is determined to be beneficial) as well as data collection and reporting capability.

Family Stabilization Services

Crisis Situations Likely Interfere With Welfare-to-Work Engagement. In order to qualify for CalWORKs assistance, households must have extremely low income and assets, and children in the household must be deprived of the support of one or both parents, through unemployment or other reasons. It is likely that some households apply for CalWORKs assistance because they are experiencing a destabilizing crisis situation that contributes to the inability to meet their own basic needs. Such crisis situations could include homelessness, severe mental health or substance abuse problems, or domestic violence. While the CalWORKs program is designed to address these issues, anecdotal evidence suggests that recipients experiencing such a crisis situation may find it difficult to connect with needed services. If crisis situations are not resolved and families are not stabilized, productive engagement in welfare-to-work may be less likely to occur.

Enhanced Case Management Could Result in More Effective Crisis Stabilization. We find that the Governor’s proposed increase in funding for case management activities with households in need of stabilization could positively affect these households’ ability to participate in welfare-to-work activities. To the extent that families in crisis struggle to manage the complexity of their life situation and welfare-to-work participation, allowing counties to spend more time on case management is a logical step.

Governor’s Proposal Lacks Needed Detail on County Implementation. However, the current proposal contains very little detail on what form stabilization services would take. As the proposal is currently formulated, it appears that a family receiving stabilization services would simply sign a welfare-to-work plan that contains activities appropriate to stabilization and counties would receive an increase in single allocation funding to provide additional case management. Given the lack of detail in the proposal, we are concerned that the proposal lacks the definition and focus needed to be effective. The administration has indicated that regulatory guidance would be provided to counties at a future date. We believe that the Legislature should weigh in during the budget process on how stabilization services are defined and carried out.

Providing Definition Could Draw on Early Engagement Workgroup Discussions. Discussions in the early engagement workgroup resulted in several concepts that could be useful in more clearly defining family stabilization. These concepts include a distinct stabilization component of the welfare-to-work flow that would feature a stabilization plan. The plan would determine activities that would result in stabilizing the family and specify the length of time that stabilization services would be provided.

Analyst’s Recommendation. We recommend that the Legislature adopt language to specifically define a stabilization component in state law. The stabilization component could feature a stabilization plan that consists of specified activities. Allowable activities for the stabilization plan could be defined in such a way as to maximize county flexibility to determine appropriate services. For example, the stabilization plan could be defined to last from one to six months at county discretion. We recommend that the Legislature approve the level of funding proposed by the Governor for enhanced case management, as we think that the methodology used to arrive at this level of funding is reasonable for the time being. It is difficult to accurately determine in advance the costs and demand for enhanced case management under a stabilization component. Therefore, future funding levels should be reassessed as more data become available, as discussed below.

Increased Reporting Would Be Necessary for Accountability and Future Policy Adjustment. As previously noted, the Governor’s proposal would provide increased funding for case management through the single allocation. Since single allocation funding can be flexibly expended on numerous activities, including program administration and child care, we are concerned that it could be difficult to assess in the future how counties are utilizing funds for stabilization and whether funding intended for this purpose is at appropriate levels. For the purposes of oversight and policy making, information about county expenditures and the number of cases participating in stabilization services would be critical.

Analyst’s Recommendation. To provide for legislative oversight and to assist legislative policy making, we recommend that the Legislature adopt language requiring DSS to collect and publish data on actual county expenditures for stabilization services and the number of cases participating in stabilization services.

Enhanced Subsidized Employment

Subsidized Employment Has Beneficial Aspects… Several aspects of subsidized employment can be beneficial to participants and to the state. Similar to unsubsidized employment, participants receive wages, which increase total family resources. (Since the calculation used to determine a household’s grant disregards a portion of the household’s income, the grant decreases by a smaller amount than the additional income.) Subsidized positions can also provide valuable real work experience that is different from what might be available in other unpaid work experience placements and that might otherwise be difficult to obtain for those who have been unsuccessful finding unsubsidized employment. Finally, as a federally approved work activity, a CalWORKs recipient’s participation in subsidized employment (1) can have a positive impact on the state’s federal work participation rate and (2) stops the 24-month time clock, such that individuals that do not successfully transition off of aid following subsidized employment could potentially continue to participate under more flexible state work rules to continue to work to address barriers to employment.

…But Evidence on Long-Term Effectiveness Is Less Certain. Evaluations of the effectiveness of subsidized employment programs to date have generally found that, while such programs increase employment and earnings in the short run, they may have limited impact on employment and earnings in the long run. Given the magnitude of the subsidized employment created under ARRA, the federal government is currently pursuing a Subsidized and Transitional Employment Demonstration project that will include randomized experimental evaluations of the effectiveness of subsidized employment programs. Los Angeles County is serving as one of the project sites. Unfortunately, the demonstration is in its early stages and will not conclude until 2017.

Evidence Supports Cautious Expansion, but May Not Warrant Proposed Level of Investment. Under the Governor’s proposal, the approximately 2,000 current partially state-funded subsidized positions would be supplemented by 8,250 fully state-funded subsidized positions by June of 2014. (The number of fully state-funded subsidized positions would gradually ramp up during the course of 2013-14.) Given the benefits of subsidized employment in general as discussed above, we believe that the proposal to expand subsidized employment has merit, and should be considered by the Legislature. However, we are concerned that the evidence around the long-term effectiveness of subsidized employment does not currently support an investment at the level that the administration proposes. Instead, a more limited expansion would still provide benefits while allowing the state to gain additional experience with enhanced subsidized employment on a trial basis so that the level of investment can be reevaluated as new evidence on its long-term effectiveness becomes available.

Analyst’s Recommendation. We recommend that the Legislature adopt this aspect of the proposal, but at a lower funding level. For example, if the Legislature were to approve a gradual expansion of the number of fully state-funded subsidized slots to 3,000 by the end of 2013-14, we estimate that the cost in 2013-14 would be approximately $13 million. If this number of slots were maintained in 2014-15, the ongoing cost would be approximately $35 million.