Part 1

In this part of the report, we analyze major budget issues involving Proposition 98, which largely governs how much funding is provided for K–12 education, child care and development (CCD), and the California Community Colleges (CCC). Voters enacted Proposition 98 in 1988 as an amendment to the California Constitution. The measure, which was later modified by Proposition 111, establishes a minimum annual funding level to support K–14 education. Proposition 98 funding constitutes around two–thirds of total K–14 funding, with the remainder of support coming from federal funds, special funds (such as lottery revenues), fee revenue (such as CCC enrollment fees), and non–Proposition 98 General Fund dollars (which are largely dedicated to debt service on school facilities and costs for teacher retirement).

We begin this part by providing some background information on the mechanics of Proposition 98. We then discuss an ongoing controversy regarding certain constitutional provisions relating to Proposition 98. Next, we summarize the Governor’s Proposition 98 plan as well as provide our assessment of that plan. Lastly, we offer an alternative plan intended to provide the Legislature with more options for crafting its education budget.

The minimum Proposition 98 funding requirement—commonly called the minimum guarantee—is determined by one of three formulas (or “tests”) set forth in the Constitution. Figure 1 briefly explains these tests. The five major factors underlying the Proposition 98 tests are (1) General Fund revenues, (2) state population, (3) personal income, (4) local property taxes, and (5) K–12 average daily attendance (ADA). In most years, the key determinants of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee are changes in K–12 ADA, per capita personal income, and per capita General Fund revenues.

Figure 1

Proposition 98 Basics

|

|

|

Three Formulas (“Tests”) Used to Determine K–14 Funding:

|

|

Test 1—Share of General Fund. Provides roughly 40 percent of General Fund revenues to K–14 education. From 1988–89 through 2007–08, this test was applied only once (1988–89).

|

|

Test 2—Growth in Per Capita Personal Income. Adjusts prior–year funding for changes in attendance and per capita personal income. This test was operative 13 of the last 20 years.

|

|

Test 3—Growth in General Fund Revenues. Adjusts prior–year funding for changes in attendance and per capita General Fund revenues. Generally, this test is operative when General Fund revenues grow more slowly than per capita personal income. This test was operative 6 of the last 20 years.

|

Applicable Test Determined Automatically. The applicable test used to determine the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee is triggered automatically depending on the inputs. Until inputs are finalized (which can take up to 12 months after the close of a fiscal year for revenue and K–12 attendance factors), the applicable test can fluctuate and the minimum guarantee can change significantly.

State Can Provide More or Less Than Minimum Guarantee. Although the Proposition 98 tests apply automatically, the Legislature can provide more or less funding than the tests require. For example, in 1999–00, when state revenues were booming, the Legislature decided to spend $1.8 billion more than the minimum guarantee. Alternatively, in 2004–05, the Legislature suspended the minimum guarantee and provided less than would have been required. To suspend the minimum guarantee requires a two–thirds vote of each house of the Legislature and creates out–year obligations to return K–14 funding to where it otherwise would have been absent the suspension.

State Creates “Maintenance Factor” Obligation in Certain Years. Over the long run, Proposition 98 has grown annually by attendance and growth in the economy (Test 2). The provisions of Proposition 98 allow the state to provide less funding than the Test 2 level in certain situations. This has occurred in Test 3 or suspension years. In these years, the state has created a maintenance factor obligation—a long–term commitment to restore Proposition 98 funding to what it otherwise would have been had funding been determined by Test 2. The state keeps track of the total amount of funding required to return schools to funding levels had it grown with the economy. At the end of 2007–08, the state had an outstanding maintenance factor obligation of $1.3 billion. As we will discuss later, the outstanding maintenance factor obligation entering 2009–10 is a subject of contention.

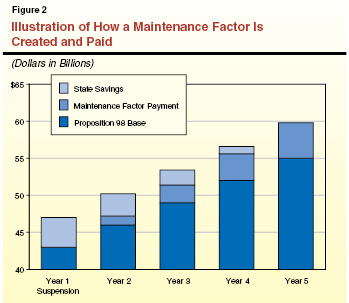

Maintenance Factor Payments Based on Growth in General Fund Revenues. Figure 2 illustrates how maintenance factor payments are made. Proposition 98 requires the state to provide additional payments in future years until funding has been built up to the level it otherwise would have reached under Test 2 or absent suspension. (Until all maintenance factor is paid off, the state generates savings each year compared to the level it otherwise would have been required to spend.) The required maintenance factor payment depends on how quickly state revenues grow. When state revenues grow quickly, larger payments are made and the obligation is paid off in a shorter period of time.

During the course of the 2008–09 fiscal year, conflicting interpretations of the constitutional provisions of Proposition 98 led to uncertainty over the amount of maintenance factor owed at the close of 2008–09. The Legislature and Governor made two attempts to resolve the issue. Below, we discuss the different constitutional interpretations as well as the state’s two responses to the controversy.

2008–09 Scenario Leads to Uncertainty. When budget and economic data was updated as part of the February 2009 budget package, an unprecedented Proposition 98 scenario arose. Test 1 was applicable, though the Test 1 funding level provided substantially less than if funding had grown with the economy and attendance (Test 2). As discussed earlier, in the past a maintenance factor obligation has been created when Test 3 applies, which is lower than Test 2. Different opinions exist as to whether a maintenance factor is created when Test 1 applies and is lower than Test 2. The administration believes that no maintenance factor is created in this situation. Others, however, believe that a maintenance factor obligation is created in any situation where funding is below Test 2 (whether Test 1 or Test 3 be applicable). Whether maintenance factor is or is not created in 2008–09 changes the state’s long–term obligation to schools by billions of dollars.

Proposition 1B Attempted to Resolve Issue Constitutionally. To resolve the issue on a one–time basis, the February 2009 budget agreement placed Proposition 1B on the May 2009 ballot. The measure proposed to amend the State Constitution to require $9.3 billion in supplemental payments beginning in 2011–12. In essence, the measure was a compromise to acknowledge a large 2008–09 maintenance factor obligation but to delay the start of payments for a few years. The measure, however, was rejected by voters.

July Budget Agreement Attempted to Resolve Statutorily. An alternative solution was adopted in the July budget. This agreement statutorily set the 2008–09 Proposition 98 minimum guarantee at $49.1 billion, without specifying the applicable test. It also established a maintenance factor obligation of $11.2 billion at the end of 2008–09—$1.3 billion from previously existing obligations and a new $9.9 billion obligation created in 2008–09. The agreement also required that associated maintenance factor payments be made as otherwise specified in the Constitution. As we discuss below, the Governor’s budget departs from this agreement—in essence reopening the controversy surrounding the creation and payment of a potential 2008–09 maintenance factor obligation.

Figure 3 shows Proposition 98 spending from 2007–08 (actual) to 2010–11 (proposed) for K–12 education, CCC, and other Proposition 98–supported agencies (including the state special schools and juvenile justice). As shown in the figure, the Governor‘s January proposal has total Proposition 98 spending virtually flat from 2009–10 to 2010–11. Despite this, the state’s General fund share would increase (4.1 percent). This is caused by local property tax revenues decreasing (8.7 percent) due to sagging property tax values and a one–time shift of local government revenues in 2009–10.

Figure 3

Proposition 98 Spending Stays Virtually Flat Under Governor’s Plan

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2007–08

Final |

2008–09

Final

|

2009–10

Revised

|

2010–11

Proposed

|

Change From 2009–10

|

|

|

Amount

|

Percent

|

|

K–12 Education

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$37,752

|

$30,260

|

$30,844

|

$32,023

|

$1,179

|

3.8%

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

12,592

|

12,726

|

13,237a

|

11,950

|

–1,287

|

–9.7

|

|

Subtotals

|

($50,344)

|

($42,986)

|

($44,082)

|

($43,974)

|

(–$108)

|

(–0.2%)

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

General Fund

|

$4,142

|

$3,918

|

$3,722

|

$3,981

|

$259

|

7.0%

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

1,971

|

2,011

|

1,953

|

1,913

|

–40

|

–2.0

|

|

Subtotals

|

($6,112)

|

($5,929)

|

($5,675)

|

($5,895)

|

($219)

|

(3.9%)

|

|

Other Agencies

|

$121

|

$105

|

$94

|

$85

|

–$9

|

–9.1%

|

|

Totals, Proposition 98

|

$56,577

|

$49,019

|

$49,851

|

$49,954

|

$103

|

0.2%

|

|

General Fund

|

$42,015

|

$34,282

|

$34,660

|

$36,090

|

$1,430

|

4.1%

|

|

Local property tax revenue

|

14,563

|

14,737

|

15,191a

|

13,864

|

–1,327

|

–8.7

|

The Governor states his plan funds K–14 education at the minimum guarantee in both 2009–10 and 2010–11. His plan, however, makes various assumptions and policy changes that affect the minimum guarantee. Most notably, his plan departs in several ways from the July budget agreement. Coupled with other components, these budget assumptions result in a lower minimum guarantee in 2008–09, 2009–10, and 2010–11. Each of these assumptions is described in more detail below.

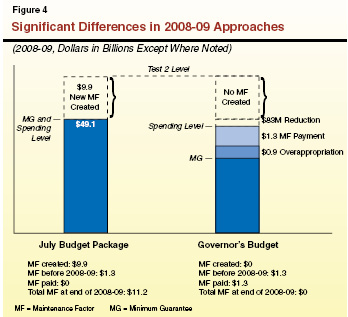

Governor Does Not Recognize New Constitutional Maintenance Factor Obligation in 2008–09, Retires Old Obligation. The Governor’s budget makes several changes associated with 2008–09. Figure 4 shows these changes—comparing the July budget plan with the Governor’s January plan. One of the major changes is associated with the amount of new maintenance factor believed to have been created in 2008–09. As shown, under the July budget agreement, the state recognizes a large new obligation whereas no new 2008–09 maintenance factor is believed to have been created under the Governor’s plan. Not only does the Governor’s plan assume no new maintenance factor is created in 2008–09, it also assumes that old maintenance factor ($1.3 billion created in prior years) can be retired. (This is possible because the minimum guarantee for 2008–09 has dropped even further since the July budget package, leaving an “overappropriation” that can count toward old maintenance factor obligation.)

Actions in 2008–09 Lower Minimum Guarantee in 2009–10 and 2010–11. If the state were to have a large maintenance factor obligation entering 2009–10, it would be required to make payments in 2009–10 and 2010–11. (These payments need to be made because the year–to–year growth rates in the state General Fund are relatively healthy due to the various revenue increases adopted by the state.) Under the Governor’s plan, the state would enter 2009–10 with no outstanding constitutional maintenance factor as a result of his proposed 2008–09 actions. By not having to make these payments, the minimum guarantee drops and the Governor is able to generate substantial state savings. Although the Governor does not recognize a constitutional maintenance factor obligation entering 2009–10, he does propose to make $11.2 billion of “in lieu” payments starting in 2011–12.

Minimum Guarantee in 2010–11 Further Lowered Due to Loss of Transportation Revenues. The 2010–11 Proposition 98 minimum guarantee is also affected by the Governor’s proposal to eliminate the sales tax on fuel (which is currently counted as General Fund revenue for purposes of calculating the minimum guarantee) and replace it with an excise tax (which would not be counted as General Fund revenue). The elimination of the sales tax reduces General Fund revenues by $1.6 billion in 2010–11, which reduces the minimum guarantee by either $640 million or $830 million (depending on related maintenance factor assumptions).

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009 provided California with almost $5 billion in general purpose education funding through the State Fiscal Stabilization Fund (SFSF). As a condition of receiving SFSF monies for education, states are required to maintain state support for both K–12 and higher education at or above the level provided in 2005–06. This maintenance–of–effort (MOE) requirement applies through 2010–11. For K–12 education and CCC, state support is defined in California’s approved SFSF application as all funding provided to districts through Proposition 98 (excluding local property taxes) and the Quality Education Investment Act (QEIA). For the University of California (UC) and California State University, the calculation is based on state General Fund support.

Proposal Includes Fund Shift to Meet 2009–10 MOE Requirements. As approved in the July budget, 2009–10 spending for K–12 and higher education was only slightly above the MOE levels ($125 million and $3 million, respectively). As discussed in more detail below, the Governor proposes to reduce K–12 spending in 2009–10, which, when combined with various other technical adjustments, would drop the state below the K–12 MOE requirement by slightly more than $200 million. To stay above the MOE level, the Governor proposes to make an early payment for the 2010–11 QEIA program. Specifically, the proposal would shift $250 million in K–12 QEIA payments that would otherwise have been provided in October 2010 to June 2010. As a result, the funds would count toward 2009–10 support and keep 2009–10 funding above the MOE level. The administration proposes a similar shift of $30 million in CCC QEIA funding to ensure the state meets the 2009–10 MOE requirement for higher education. (The administration estimates that state higher education funding would otherwise fall below the MOE requirement due to an unanticipated current–year drop in UC’s lease–revenue payments.)

Proposed K–12 Funding Level Requires Waiver. In 2010–11, the administration’s proposed level of K–12 spending is roughly $600 million below the K–12 MOE requirement. By comparison, the administration’s proposal for higher education is almost $900 million above the higher education MOE requirement. To provide fiscal relief to states, the federal government can waive K–12 and/or higher education MOE requirements. However, to be eligible for a waiver, states must maintain the same or more support for education (K–12 and higher education combined) as a share of total state support as in the prior fiscal year. Based on preliminary estimates, the state would qualify for a waiver in 2010–11. The administration has submitted the required application to seek federal permission to spend below the K–12 MOE level. Final approval will not be granted until several months after the close of 2010–11, when final expenditure data are available.

Figure 5 summarizes the major components of the Governor’s Proposition 98 proposal. Despite a small year–to–year increase in Proposition 98 funding, a heavy reliance on one–time solutions in 2009–10 necessitates large reductions to existing programs. The major pieces of the plan are discussed below.

Figure 5

Proposition 98: Governor’s Major Spending Proposals

(In Millions)

|

|

|

|

Midyear 2009–10 Proposals

|

|

|

Recognize K–3 Class Size Reduction (CSR) savings

|

–$340

|

|

Make various other baseline adjustments

|

–228

|

|

Total Changes

|

–$568

|

|

2010–11 Proposals

|

|

|

Backfill prior–year one–time solutions

|

$1,908

|

|

Make various other adjustments

|

238a

|

|

Reduce K–12 revenue limits:

|

|

|

Spend less on noninstructional activities

|

–1,184

|

|

Remove restrictions on contracting out

|

–300

|

|

Consolidate County Office of Education functions

|

–45

|

|

Make K–14 cost–of–living adjustments (–0.38 percent)

|

–230

|

|

Recognize additional K–3 CSR savings

|

–210

|

|

Reduce CalWORKs Stage 3 child care funding

|

–123

|

|

Reduce child care reimbursement rates

|

–77

|

|

Fund CCC apportionment growth (2.21 percent)

|

126

|

|

Total Changes

|

$103

|

Small Midyear Reductions. The Governor proposes to reduce 2009–10 Proposition 98 spending by $568 million. The reduction, which includes two major components, largely reflects a recapturing of funding expected to go unused and thus would have no programmatic effect on school districts. One part of the reduction is $340 million in savings from the K–3 Class Size Reduction (CSR) program. Beginning in 2008–09, the state allowed school districts to increase class size above the previous 20–student cap but provides reduced levels of funding (“penalties”) to those who choose to do so. As some districts increased K–3 class sizes for the 2009–10 school year, these funding reductions are leading to sizeable statewide savings. The remainder of the reduction is due to various technical adjustments, which are due primarily to K–12 attendance being slightly lower than projected.

One–Time Solutions in 2009–10 Lead to More Than $2 Billion in 2010–11 Reductions. Although the Governor proposes to keep overall Proposition 98 spending virtually flat across the two years, his plan contains $2.2 billion in budget–year programmatic reductions (detailed in Figure 5). These reductions are necessitated by the heavy reliance on one–time solutions in 2009–10. Most notably, the state achieved $1.8 billion in one–time Proposition 98 savings in 2009–10 by deferring K–12 revenue limit payments and community college payments. These deferrals essentially allowed school districts to operate a program in 2009–10 that the state could not afford. In 2010–11, the Governor’s proposal would require school districts to reduce their ongoing program consistent with available ongoing resources.

Most of Reduction Is to K–12 Revenue Limits. The largest of the proposed reductions for 2010–11 is a $1.5 billion cut to K–12 general purpose funding (commonly known as revenue limits). The reduction is tied to three policy changes the administration expects will provide savings at the local level. First, his plan would require school districts to spend less on noninstructional activities, for anticipated savings of $1.2 billion. His plan also would ease existing restrictions on the contracting out of noninstructional services, with $300 million in expected local savings. (The Governor’s budget eases similar restrictions for CCC, but does not propose a corresponding reduction in CCC apportionments.) Both of these reductions would be made uniformly to all school districts, regardless of whether the district is able to achieve savings from these new policy changes. Third, his plan would require county offices of education (COEs) to consolidate certain functions, for anticipated savings of $45 million. As with the proposed cut to school district revenue limits, this reduction would be made uniformly to all COE revenue limits, regardless of the level of county savings achieved.

Makes $200 Million Reduction to Child Care. The Governor proposes two major changes to the state’s child care and development programs. He proposes to eliminate roughly 18,000 slots from California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs) Stage 3 child care, for savings of $123 million. In addition, he proposes to reduce reimbursement rates for voucher–based child care programs, for $77 million in Proposition 98 savings (and $55 million in non–Proposition 98 savings). Specifically, he proposes to lower reimbursement rates for licensed providers from the 85th percentile of the regional market rate (RMR) to the 75th percentile. He proposes to lower the reimbursement rate for license–exempt providers from 90 percent of the licensed rate to 70 percent. He proposes to link both licensed and licensed–exempt rates to the 2005 RMR survey.

Other Adjustments. The Governor proposes to apply a cost–of–living adjustment (COLA) of –0.38 percent to most K–14 programs. Applying the negative COLA results in savings of $230 million ($201 million for K–12 education, $23 million for CCC, and $6 million for CCD). Partly offsetting these reductions, the administration proposes funding increases in two major areas. The Governor proposes to fund 2.2 percent growth in community college enrollment (for a cost of $126 million). He also proposes to fund three K–12 mandates (for a cost of $79 million). Specifically, he would fund the mandates associated with behavioral intervention plans for special education students ($65 million), inter– and intradistrict transfers ($7.7 million), and the California High School Exit Exam ($6.8 million). The administration proposes to suspend all other K–14 mandates, except for a mandate related to high school science graduation requirements, which the administration is challenging in court.

New Flexibility Options Proposed for 2010–11. To provide some help to districts as they respond to another tight budget, the administration proposes new flexibility options, which primarily relate to the state’s teacher policies. For K–12 teachers, the Governor proposes to: (1) extend the layoff notification window specified in state law to the last day of the school year and eliminate layoff hearings; (2) amend state law to eliminate teacher seniority rules that apply to layoffs, as well as assignments, reassignments, transfers, and hires; (3) eliminate state rules regarding priority and pay for laid–off teachers serving as substitute teachers; (4) extend the observation window for probationary teachers to four years; and (5) make numerous changes to the teacher dismissal process. For CCC faculty, he proposes to suspend requirements related to the number of full–time faculty that districts must employ. The administration’s proposal also increases the number of categorical programs in the CCC’s “flex item” from 12 to 14 (out of 21 total programs).

The Governor’s overall Proposition 98 funding plan is tenuously held together. As a result, the plan could quickly unravel under certain circumstances related to constitutional interpretation, revenue assumptions, and federal requirements. If any of the Governor’s key assumptions do not come to pass, then the plan would no longer be workable. Below, we discuss each of these major risks and then lay out two alternative courses of action.

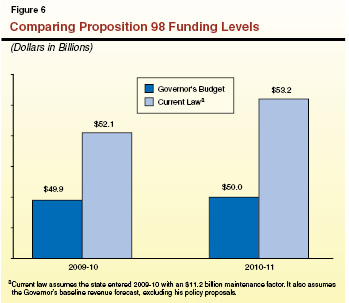

Governor’s Proposal Has Some Legal Risk. As mentioned previously, the Governor’s proposed funding level is based on his interpretation of the constitutional provisions of Proposition 98 regarding the creation and payment of maintenance factor. If a different interpretation were to prevail, the minimum guarantee would be significantly higher. Figure 6 compares what the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee is under the Governor’s plan with what it would be under current law. (By current law, we mean that the state entered 2009–10 with an $11.2 billion maintenance factor. We also assume the Governor’s baseline revenue forecast, excluding his policy proposals.) As the figure shows, the minimum guarantee would be $2.2 billion higher in 2009–10 and more than $3.2 billion higher 2010–11.

Minimum Guarantee for 2010–11 Could Increase Due to Interaction With Revenue Proposals. Apart from issues of constitutional interpretation, the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee could be significantly affected by changes to state General Fund revenues. If the Governor’s proposal to eliminate the sales tax on fuel were not adopted, then the minimum guarantee would increase by $640 million (if no outstanding maintenance factor exists) or $830 million (if outstanding maintenance factor does exist). The minimum guarantee also would increase if the Governor’s “trigger” proposals were to go into effect. The Governor’s proposal includes $2.3 billion in revenue increases that would be implemented if the state did not receive a total of $6.9 billion in federal funds. Should the trigger go into effect, the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee would increase by $900 million to $1.3 billion (also depending on maintenance factor assumptions).

State Needs Education Waiver, Which Is Connected to All Other State Spending. Apart from assumptions about state constitutional issues and state revenue proposals, the Governor’s plan also assumes the state will meet the federal criterion for receiving a waiver from the ARRA education MOE requirement. To qualify for this waiver, the state must show that state support for education (K–12 and higher education combined) as a share of total state support does not decrease from 2009–10 to 2010–11. Though the administration’s January plan meets the waiver criterion, changes to state spending—either in education or in other areas of state government—could affect the state’s ability to qualify for a waiver. For instance, should the state choose to spend $6 billion in other areas of the state budget in 2010–11, education’s share of state support would be reduced and leave the state unable to qualify for a waiver.

Given how tenuously the pieces of the Governor’s funding plan are held together, the Legislature will want to consider other possible courses of action. While accepting the Governor’s approach would help the state balance its budget, it would come with serious risks. The Legislature has two basic alternatives—both of which involve their own difficult choices. First, one alternative would be to suspend the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee. This option is the safest legal course of action and offers the Legislature the most flexibility in building both the education and the overall state budget. A second option would be to spend more on education than the Governor proposes to meet the higher current–law funding requirements—either by reducing spending more in other areas or by raising additional revenues.

Suspend Proposition 98. Suspending Proposition 98 in 2009–10 and 2010–11 would allow the state to decide the level of funding it could afford for K–14 education, regardless of the Proposition 98 formulas, constitutional interpretations of maintenance factor, and otherwise interacting revenue proposals. Suspension requires a two–thirds vote of each house of the Legislature. (Under suspension, the state creates a new maintenance factor obligation, which would require additional payments in future years.)

Raise Additional Revenues or Cut Other Spending to Meet Higher Current–Law Funding Levels. The Legislature could take another course of action and either raise enough additional revenues or make further spending reductions elsewhere in the budget to meet the higher current–law K–14 funding level for 2010–11 ($3.2 billion). To the extent the Legislature used new tax revenues to provide this supplemental funding, the initial $3.2 billion gap would grow. This is because without suspending Proposition 98, every new dollar of General Fund revenue increases the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee by 40 cents to 50 cents. For example, if the Legislature were to take this approach relying entirely on tax revenues, it would need to raise roughly $6 billion in new revenues, with essentially all of the new funding used for K–14 education. (We assume the state would be able to meet a higher funding obligation in 2009–10 through “settle–up” payments in future years.)

Generally Headed in Right Direction. After determining how much total Proposition 98 funding to provide, the state will need to decide how to spend available monies. We believe the Governor’s overall Proposition 98 spending plan has some merit. Specifically, we think the Governor’s overall plan heads in the right direction by finding some ways to reduce costs, providing additional flexibility, and seeking additional federal funding. In these ways, the administration tries to help local education agencies in responding to another tight budget. The administration’s Proposition 98 plan also does not rely on any new borrowing. Instead, the administration proposes ongoing solutions to align ongoing program with ongoing resources.

…But Misses Many Opportunities. Though the Governor’s spending plan appears to be headed in generally the right direction, we believe it misses many opportunities. Specifically, we believe the Governor’s plan misses opportunities to increase flexibility, undertake meaningful reform, align state and federal programs, and leverage additional federal funding. Moreover, the plan makes rather tenuous links between state cuts and local savings. Below, we discuss each of these shortcomings in more detail. In “Part 2” of this report (which covers K–12 education and child care), as well as in the “Community Colleges” section of our companion higher education report, we discuss each of the Governor’s specific K–14 spending proposals. Figure 7 lists each of the Governor’s specific spending proposals, indicates our accompanying recommendation, and includes the page reference where our more detailed analysis can be found.

Figure 7

Summary of Governor’s 2010–11 Proposals and Accompanying LAO Recommendations

|

Governor's Proposal

|

LAO Recommendation

|

Detailed Analysis

|

|

K–12 Education

|

|

|

|

Mandates. Suspends all but three K–12 mandates.

|

Modify

|

ED–23

|

|

Noninstructional Spending. Reduces school district revenue limits by $1.2 billion and caps noninstructional spending.

|

Reject

|

ED–28

|

|

Contracting Out. Reduces school district revenue limits by $300 million and removes restrictions on contracting out for noninstructional services.

|

Modify

|

ED–29

|

|

County Services. Reduces county office of education revenue limits by $45 million and encourages consolidation of more functions.

|

Modify

|

ED–30

|

|

Class Size Reduction. Recognizes $550 million in savings due to new program rules.

|

Modify

|

ED–31

|

|

Negative COLA. Applies –0.38 percent cost–of–living adjustment (COLA) to most K–12 and child care programs, for savings of $207 million.

|

Reject

|

ED–32

|

|

Child Care Reimbursement Rates. Lowers maximum amount state will reimburse child care providers ($132 million savings, including $77 million Proposition 98 savings).

|

Modify

|

ED–33

|

|

CalWORKs Stage 3 Child Care. Reduces by $123 million and eliminates 18,000 slots.

|

Modify

|

ED–36

|

|

Layoff Notifications. Changes date for final notification from May 15 to last day of school.

|

Modify

|

ED–40

|

|

Layoff Hearings. Eliminates Reduction–in–Force hearings.

|

Adopt

|

ED–41

|

|

Teacher Seniority. Removes requirement that seniority be used in making certain personnel decisions.

|

Modify

|

ED–42

|

|

Priority for Substitute Teaching. Removes requirement that laid–off teachers get priority for positions and paid at pre–layoff rate.

|

Adopt

|

ED–43

|

|

Probationary Period. Would increase the probationary period from two to four years, with the option of granting tenure after two years.

|

Adopt

|

ED–44

|

|

Dismissal Notices. Allows district to notice teachers of dismissal over summer months.

|

Reject

|

ED–46

|

|

Dismissed Teacher Salary. Allows districts to cease paying salary and benefits to a teacher once the dismissal notice is served.

|

Modify

|

ED–46

|

|

Dismissal Hearings. Lifts the four–year limit on evidence introduced in dismissal hearings.

|

Adopt

|

ED–46

|

|

Commission on Professional Competence. Eliminates two teachers from panel and makes administrative law judge’s ruling advisory to the local governing board.

|

Modify

|

ED–46

|

|

Federal Special Education Funding. Seeks $1 billion in one–time funding to reimburse state for past special education costs.

|

Modify

|

ED–47

|

|

California Community Colleges

|

|

|

|

Enrollment Growth. Provides $126 million in Proposition 98 General Fund support for 2.2 percent enrollment growth.

|

Modify

|

HE–21

|

|

Negative COLA. Applies –0.38 percent COLA to apportionments and certain categorical programs, for savings of $23 million.

|

Reject

|

HE–27

|

|

Contracting Out. Removes certain restrictions on contracting out for noninstructional services. (Unlike K–12, Governor does not propose a corresponding reduction to apportionments.)

|

Adopt

|

HE–36

|

|

Mandates. Suspends all CCC mandates.

|

Modify

|

HE–36

|

|

Categorical Program Flexibility. Places three currently protected categorical programs in CCC flex item.

|

Modify

|

HE–40

|

|

Base Reduction to Categorical Programs. Applies base cut to two categorical programs (both proposed to be in flex item) and redirects these funds to augment funding for Career Technical Education (CTE) "pathways" initiative.

|

Reject

|

HE–41

|

|

Quality Education Investment Act. Provides $48 million in non–Proposition 98 funds for CTE pathways initiative.

|

Adopt

|

HE–41

|

|

Full–Time Faculty Hiring Requirements. Suspends law and corresponding regulations that require districts to meet certain hiring targets for full–time faculty.

|

Adopt

|

HE–41

|

Misses the Mark on Flexibility Proposals. The Governor proposes several additional flexibility options. For example, the Governor proposes several changes to state teacher policies as well as expanding the CCC flex item. We believe these proposals have several shortcomings. Perhaps most importantly, a few of the Governor’s proposals would result in less rather than more flexibility. For example, the Governor proposes adding three programs to the CCC flex item, only to cut that item and use the freed–up funds for a restricted categorical program. Similarly counterproductive, one of the K–12 proposals would place new strings on previously unrestricted monies. While a few of the Governor’s other proposals would increase flexibility, some of the near–term benefit would be quite limited. For example, given state teacher provisions often have similar counterparts in local bargaining agreements, we think changes in the state provisions would offer districts little initial increase in flexibility (though the proposals still could be worthwhile for other reasons).

Takes Expedient Rather Than Thoughtful Approach to Reform. The Governor’s plan is packed with policy changes. Among the most significant of these changes is the Governor’s proposal to suspend virtually all education mandates in 2010–11. We have two serious concerns with this approach. First, suspension treats virtually all currently mandated activities alike regardless of policy merits. For example, suspension would temporarily remove restrictions that students receive potentially lifesaving immunizations before entering school—treating these immunizations comparably to a duplicative physical education reporting requirement. Second, suspending mandates for one year creates confusion for districts. Districts would be left guessing as to which activities are likely to be reinstituted in 2011–12 and which ones are likely gone permanently. If a district guesses wrong, it either loses potential savings or incurs added costs to reconstruct processes that it prematurely dismantled.

Misses Opportunities to Align Program Efforts. In a few cases, the Governor’s plan is notable for the absence of strategic, coordinated proposals. For example, the administration spends more than $400 million in state funding for school improvement while not building a budget plan for $650 million in available federal funding for school improvement. Despite the obvious nexus between these program efforts, the administration does nothing to align them, reduce associated administration burden, and achieve state savings. The Governor’s budget also includes no plan for spending available federal funding for local education technology efforts, nor does it attempt to coordinate those local efforts with state efforts. Moreover, the administration misses opportunities to combine various K–12 career technical education programs as well as various programs for K–12 and CCC low–income students.

Could Go Further in Leveraging Federal Aid. The Governor’s plan seeks $1 billion in additional federal funding associated with special education, but the proposal has several shortcomings. It seeks one–time rather than ongoing relief, requests funding only for California even though California has not been particularly disadvantaged relative to other states, and does not use the funds for education. Moreover, the Governor’s K–14 budget plan includes no other proposals for maximizing or leveraging federal aid. Among the most obvious missed opportunity is the failure to leverage more federal aid (through a newly expanded tax credit) by raising CCC fees. (Although not part of his budget plan, the administration has applied for federal Race to the Top funds for K–12 education.)

Makes Tenuous Link Between State Cuts and Local Savings. The Governor also makes almost $2 billion in state cuts to K–12 education—proposing various associated policy changes to help local education agencies absorb these cuts. For example, the Governor would restrict how much school districts spend on noninstructional services, relax rules on contracting out for noninstructional services, and consolidate county–based services. While we think some of the proposals have policy merit, we question linking them to specific state cuts. Moreover, these proposals have virtually no chance of producing as much local savings as assumed. In addition, the Governor misses at least a few opportunities to further reduce local costs (for example, by changing the kindergarten start date) as well as state costs (for example, by reorganizing the California Department of Education).

This section lays out an alternative to the Governor’s Proposition 98 plan. We do not link our alternative to a specific funding level in recognition that the Legislature could choose to suspend Proposition 98 and fund at whatever level it deemed appropriate, take various actions to meet the higher current–law Proposition 98 funding requirement, or adopt the Governor’s funding level. Instead, we offer a strategy for building the education budget that could be used regardless of the exact dollar amount ultimately provided for K–14 education. Our alternative is intended to provide the Legislature with both a better overall approach toward crafting its education budget and recommendations for addressing specific K–14 budget issues.

Alternative Makes Various Improvements to Governor’s Plan. The alternative builds on the positive aspects of the Governor’s plan but tries to make various improvements. In particular, the alternative identifies additional ways to reduce costs and expands flexibility for schools and colleges. Moreover, the alternative includes comprehensive mandate reform, strategically aligns certain existing program efforts, and seeks opportunities to increase federal support. Figure 8 summarizes the basic building blocks of the Proposition 98 budget. Each component is discussed in more detail below.

Figure 8

Building Blocks of Proposition 98 Budget

|

|

- Weigh priorities among K–12 education, child care and development, and the community colleges.

|

- Make targeted reductions.

|

- Make additional reductions, as needed, to apportionments and/or categorical programs.

|

|

|

- Undertake comprehensive education mandate reform.

|

|

|

- Leverage additional federal funding.

|

Weigh Overall Proposition 98 Priorities. The first challenge the Legislature faces in building its Proposition 98 plan is to establish priorities among CCD, K–12 education, and community colleges. Given all three areas have experienced reductions in programmatic funding over the last few years, evaluating where to make additional cuts likely will be particularly difficult. From 2007–08 (actual) to 2010–11 (proposed by Governor), programmatic funding would decline almost 3 percent per child care slot and more than 10 percent per K–12 student. Community college programmatic funding would decline almost 5 percent based on budgeted per student counts and up to roughly 10 percent based on actual per student counts. Aside from these comparisons, the Legislature obviously will want to weigh other considerations, such as the different populations, needs, programmatic quality, and public benefits of the three areas. Whereas the Governor makes all 2010–11 spending reductions to CCD and K–12 education, our alternative cuts CCD less than the Governor, while also raising student fees to provide more overall CCC funding, thereby preventing even deeper cuts to K–12 education.

Make Targeted Reductions. After developing an overall plan for allocating funds among the segments, we recommend making as many targeted reductions as possible. Figure 9 lists the almost $1.1 billion of targeted reductions included in our alternative (about $800 million in Proposition 98 and almost $300 million in non–Proposition 98 General Fund reductions). Most of these reductions involve difficult policy decisions. For example, the alternative achieves savings by lowering the eligibility ceiling for families to receive subsidized child care from 75 percent to 60 percent of the state median income. A few of the reductions, however, merely reflect savings from programs being overbudgeted. For example, given the decline in K–12 ADA, Economic Impact Aid is now overbudgeted by more than $100 million. Similarly, if the state were to continue funding the Charter School Facility Grant program on a reimbursement basis, it would have overbudgeted significantly in 2009–10 and 2010–11. (The Governor’s budget assumes a funding change will be adopted in the 2009–10 special session.) As discussed in more detail in the nearby box, we also recommend changing the kindergarten start date, beginning in 2011–12. (Given lead time is needed to implement the change without serious disruption, and 2011–12 looks to be another difficult budget year, we recommend enacting the authorizing legislation this year.)

Figure 9

LAO–Recommended Reductions

2010–11 (In Millions)

|

Program

|

Recommendation

|

Reduction

|

|

Proposition 98–Funded Programs

|

|

|

K–3 Class Size Reduction

|

Reduce 2007–08 level by 20 percent (consistent with other flex programs), then fold into K–12 flex item.

|

$382

|

|

CCC fees

|

Use increase in fee (from $26 to $40 per unit) to fund "overcap" enrollments and reverse the Governor’s proposed negative cost–of–living adjustment.

|

125

|

|

Economic Impact Aid

|

Align funding with eligible student counts.

|

101a

|

|

Child care eligibility ceilings: Non–CalWORKs programs

|

Reduce from 75 percent to 60 percent of state median income for $115 million savings. Redirect $55 million to expand access to lowest–income families. Results in net loss of about 8,000 slots.

|

60

|

|

Child care reimbursement rates: CalWORKs Stage 2 and 3, Alternative Payment programs

|

Reduce license–exempt rates from 90 percent to 70 percent of licensed rates.

|

45

|

|

County offices of education (COE)

|

Reduce general purpose revenue limit allocation by 10 percent. Redirect additional 10 percent into new COE regional revenue limit.

|

33

|

|

Charter School Facility Grant program

|

Align funding with program cost.

|

34b

|

|

Child care eligibility ceilings: CalWORKs Stage 3

|

Reduce from 75 percent to 60 percent of state median income. Results in loss of about 4,000 slots.

|

15

|

|

Migrant child care

|

Align funding with program need.

|

7

|

|

Subtotal

|

|

($802)

|

|

Non–Proposition 98–Funded Programs

|

|

|

Quality Education Investment Act

|

Fund eligible schools using federal school improvement monies.

|

$231

|

|

Child care reimbursement rates: CalWORKs Stage 1

|

Reduce license–exempt rates from 90 percent to 70 percent of licensed rates.

|

35

|

|

California Department of Education: State operations

|

Reduce by roughly 150 positions to align staffing with program needs.

|

10

|

|

Subtotal

|

|

($276)

|

|

Total General Fund Savings

|

$1,078

|

|

In California, a child can begin kindergarten as young as four years and nine months. This is because California’s current cut–off date for entering kindergarten is December 2 of the year in which the child turns five years old. This is one of the latest kindergarten entry dates in the nation. In recent years, the California Performance Review, the Governor’s Committee on Education Excellence, and numerous legislative proposals have suggested moving the kindergarten entrance date back to September 1 (requiring a child to have turned five prior to entering kindergarten). We recommend the Legislature take action this year to make this change beginning in the 2011–12 school year. (As is current policy, we recommend allowing parents to seek a waiver if they want to enroll a younger child.)

Research Suggests Positive Effects on Children. Many have argued that entering kindergarten before turning five years of age is too young, and beginning school at an older age would benefit children’s academic performance and social development. Data suggest children who are older when they start kindergarten tend to perform better on standardized tests. Some research suggests this change also may lead to other positive student outcomes, including less chance of grade retention and higher earnings as an adult. The research is somewhat varied on the factors that contribute to these positive effects, mentioning family characteristics, preschool experience, and the relative age of the child as important influences on later student outcomes. Taken together, this body of research suggests that changing the kindergarten entry age would be generally positive, with no overall negative effect on children’s academic achievement.

Change Could Lead to Budgetary Savings. Our economic forecast suggests the state and schools will face another tight budget situation in 2011–12. Because of the ambiguity surrounding the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee, we are not certain that changing the kindergarten start date would have any effect on the amount the state is required to spend on schools in 2011–12. Even if the change does not result in state savings, however, it could help ease the budget crunch for schools. Changing kindergarten eligibility for roughly 100,000 children born between September and December would mean schools would be required to serve fewer students. We estimate that having 100,000 fewer kindergarteners in 2011–12 could free up roughly $700 million from revenue limits and categorical programs. These funds could be redirected for other K–12 purposes, including a portion for subsidized preschool for any affected low–income children. |

Between Apportionments and Categorical Programs, Decide Mix of Remaining Reductions. If the Legislature decides that additional reductions are needed beyond the $1.1 billion we have identified (the Governor’s plan has almost $2 billion in Proposition 98 cuts), then we recommend it make additional reductions to apportionments and/or the categorical flex items. The Legislature relied on these approaches in 2008–09 and 2009–10 to generate large amounts of savings. Exactly how the cut is applied will have distributional effects among districts. Because categorical program funding varies significantly by district—with certain large districts receiving more than small districts (and charter schools)—electing to cut categorical flex funding will have a different impact than electing to cut apportionments. Given the varying distributional effects, the Legislature might want to use some combination of the two strategies. For CCC, the Legislature also could consider certain targeted reductions to apportionments. For example, it could reduce funding for physical education and other lower–priority enrichment classes.

Maximize Flexibility. Our alternative includes a dozen flexibility options to help districts cope with another tight budget. Figure 10 briefly describes each option. (In the nearby box, we provide additional detail on a few of these recommendations, with the remainder discussed elsewhere in this report and our companion higher education report.) In several cases, we recommend folding more programs into the K–12 and CCC flex items. (These flex items allow K–12 districts to use associated funding for any education purpose and allow CCC districts to use associated funding for any categorical program purpose.) In several other cases, we recommend easing or removing specific state requirements. For example, we recommend easing existing restrictions associated with contracting out for noninstructional services and CCC’s “50 Percent” law, as well as removing restrictions that laid–off teachers be given priority for substitute teaching assignments. In the remaining cases, we recommend specific policy changes to remove certain restrictions while preserving some of the underlying policy objectives. For example, we recommend eliminating certain K–12 career technical education (CTE) program requirements and reorienting the CTE system around performance outcomes. We also recommend eliminating many K–14 mandates (as discussed in more detail below).

Figure 10

LAO Flexibility Package

|

Program/Provision

|

Recommendation

|

|

After School Education and Safety (ASES)

|

Repeal certain provisions of Proposition 49 and include ASES in K–12 flex item. (Requires voter approval.)

|

|

Career Technical Education (CTE)

|

Combine funding from two CTE programs in K–12 flex item and three CTE programs outside K–12 flex item.

|

|

English Learner Acquisition Program

|

Shift funding into Economic Impact Aid.

|

|

Home–to–School Transportation

|

Include in K–12 flex item.

|

|

K–3 Class Size Reduction

|

Include in K–12 flex item.

|

|

Priority for substitute teaching positions

|

Remove requirement that districts give laid–off teachers priority for these positions and pay them at pre–layoff rates.

|

|

Quality Education Investment Act (QEIA)

|

Allow QEIA schools qualifying for federal school improvement funding to be subject only to federal requirements (that is, free from state QEIA requirements).

|

|

Contracting out for K–12 and CCC noninstructional services

|

Ease restrictions on contracting out for noninstructional services.

|

|

K–12 and CCC mandates

|

Eliminate many K–14 education mandates.

|

|

CCC categorical flexibility

|

Add to the "flex item" the Basic Skills Initiative, Extended Opportunity Programs and Services, Fund for Student Success, and Financial Aid Administration.

|

|

CCC full–time faculty

|

Suspend requirements on the number of full–time faculty that districts must employ.

|

|

CCC "50 Percent" law

|

Give districts more ability to hire faculty that provide direct support services to students by including expenditures on counselors and librarians as part of instructional costs. Alternatively, suspend the law until 2012–13.

|

|

The state excluded roughly 20 categorical programs from the K–12 “flex item” created during the 2009–10 budget process—leaving in place the existing restrictions on how districts must spend the associated dollars. We believe districts would benefit from relaxing categorical rules for several of these programs. We also recommend aligning California Department of Education (CDE) staff levels with categorical flexibility decisions. Our specific recommendations are detailed below.

Add Home–to–School (HTS) Transportation and After School Education and Safety (ASES) Programs to Flex Item. Last year, the Legislature excluded the HTS transportation program from the flex item because at the time the program was being funded with special funds that had to be used for transportation purposes. Under the Governor’s 2010–11 proposal, the HTS program is funded with Proposition 98 monies. As such, we see no reason to continue to treat this program differently from most other K–12 programs. We therefore recommend adding the program and its associated funding (roughly $500 million) to the flex item. Similarly, we continue to recommend the Legislature ask voters to repeal the existing restriction that roughly $550 million in K–12 funds be used solely for after school services. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature place a measure on the ballot to repeal Proposition 49 (which created the automatic ASES funding requirement), and, if it passes, to add the ASES program into the flex item. Relaxing restrictions on the HTS and ASES programs would provide districts with discretion over about $1 billion in previously restricted categorical funds.

Shift English Learner Acquisition Program (ELAP) Into Economic Impact Aid (EIA). Currently, ELAP must be used to provide services to English learner (EL) students in grades 4 through 8. We recommend merging ELAP and its associated funding ($50 million) into the more broad–based EIA program, which supports various activities benefiting EL and low–income students. While continuing to dedicate funds for the state’s most at–risk students, this change would grant districts flexibility to spend the funds on EL and low–income students of any grade level, depending on their areas of greatest need.

Streamline Funding for Career Technical Education (CTE), Focus on Student Outcomes. In 2008–09, the state allowed funds associated with two CTE programs serving high school students to be used for any educational purpose while maintaining detailed requirements for three other high school CTE programs. To better coordinate the state’s fractured CTE system and increase local flexibility, we recommend consolidating all high school CTE funding ($427 million) and eliminating programmatic requirements in favor of monitoring related student outcomes. (One such consolidation approach would be to roll the funds into high schools’ revenue limits.) Under this approach, districts receiving CTE funding would be held accountable for various student outcomes, including the percentage of high school students that enter postsecondary education or begin employment in a high–wage industry. By holding districts more accountable for student engagement and outcomes, the state could ensure students receive the positive benefits of CTE while providing more flexibility to districts in developing effective high school programs.

Align CDE Staff Levels With Categorical Flexibility Decisions. Despite the state’s decision last year to essentially eliminate the programmatic and funding requirements associated with roughly 40 state categorical programs, the state has made no corresponding changes to CDE’s staffing of those programs. In short, CDE now has hundreds of staff members assigned to administering programs that the state is not now operating. (This disconnect would be amplified if the Legislature were to adopt a more expansive flexibility package this year.) To reflect the impact of consolidating categorical programs on state operations, we recommend decreasing CDE’s budget by $10 million and eliminating roughly 150 positions. |

Undertake Comprehensive Reform of Education Mandates. As one way to help districts free up funds for high priorities, we recommend the Legislature undertake comprehensive education mandate reform. As detailed in our recent report, Education Mandates: Overhauling a Broken System (February 2010), we assess each of the 51 existing K–14 mandates on a case–by–case basis. In the few cases mandates are serving essential purposes, we recommend funding them using a simplified reimbursement process. For some mandates, the underlying policy objective appears worth preserving, but we think the mandate process is not the best means of achieving the objective. In these cases, we find a more effective means of achieving largely the same goal. We recommend eliminating the remaining mandates either in whole or part. By relieving schools from performing the vast majority of K–14 mandate requirements, our package of recommendations would result in about $375 million in annual savings. We think this is a far superior approach to merely suspending virtually all mandates with little regard for their policy merits (as the Governor proposes).

Find Ways to Better Align Programs. One way to promote flexibility as well as maximize efficiency and potential program effectiveness is to align complementary programs. We have identified several areas in which existing state and/or federal policies suffer from a lack of alignment. One of these areas is K–12 school improvement. In this area, we recommend a number of policy changes that would align state and federal programs—essentially freeing districts from state rules while still complying with federal rules. This would both streamline the improvement process for struggling schools as well as generate state savings. Another area suffering from misalignment is education data and technology. In this area, we recommend changes that would ensure various state and local efforts are working in concert.

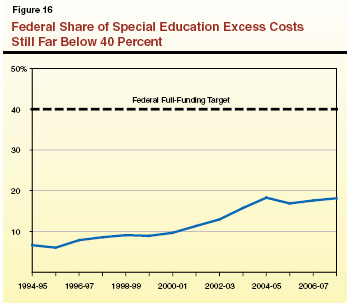

Leverage More Federal Funding. Lastly, our alternative includes two specific components designed to increase federal funding for education. For K–12 education, we recommend the state request that the federal government increase federal special education funding, such that the federal appropriation covers 40 percent of the excess cost of educating a special education student on an ongoing basis for all states—consistent with longstanding federal policy. For CCC, we recommend leveraging more federal support via a recently enacted tax credit. Specifically, we recommend raising the CCC fee from $26 to $40 per unit. This would generate roughly $150 million to help support CCC programs while having only a modest impact on students. This is because most students would qualify either for a state fee waiver or the federal tax credit, which provides full reimbursement of fee costs. (Even at this higher amount, California’s fee rate would remain the lowest in the country.)

Part 2

In this part of the report, we offer a brief retrospective on major developments relating to K–12 school finance. We then analyze the Governor’s proposals to reduce K–12 and CCD spending, modify several state teacher policies, and dedicate federal funding for various K–12 purposes.

Over the last couple years, school districts have faced significant budget challenges. In 2008–09 and 2009–10 combined, the state reduced ongoing K–12 Proposition 98 spending by over $16 billion. As a result, virtually all districts had to make programmatic reductions. School districts did, however, have various means to mitigate the effect of these reductions. Most importantly, school districts relied heavily on other revenue sources—including federal ARRA funds, categorical program reserves, and one–time state funds—to offset part of the reductions. State deferrals also allowed districts to avoid reductions by paying for programs using revenues from the next year. Finally, districts were able to use categorical flexibility provided in the February and July agreements to shift funding from lower to higher priorities. Below, we discuss each of these budget responses in more detail, discuss the current cash position of school districts, and describe the fiscal outlook for school districts in 2010–11.

ARRA Funds Mitigate Reductions. Perhaps the most significant source of relief for school districts came from federal stimulus funding provided through ARRA. In total, ARRA provided $6.1 billion in one–time funding for school districts to operate programs in 2008–09, 2009–10, and 2010–11. Of that amount, approximately $3.1 billion can be used by school districts for any purpose. The remaining $3 billion must be used for specific federal education programs, which primarily serve special education and economically disadvantaged students.

Restricted Reserves Freed Up for Any Educational Activity. The February 2009 budget also freed up additional resources for districts by allowing reserves from many restricted categorical programs to be used for any purpose. Based on data from the California Department of Education (CDE), school districts relied heavily on these funds to operate during the 2008–09 year. Entering 2008–09, districts statewide had approximately $3.1 billion in total restricted categorical reserves. Of this amount, the state freed up $2.2 billion that could be used for any education purpose. By June 30, 2009, only $291 million of the freed–up categorical reserves remained. (Although most of these funds were transferred out of restricted accounts in 2008–09, they will likely be spent over both 2008–09 and 2009–10.)

Districts Use One–Time State Revenues to Cover Costs. In addition, the state provided $2.2 billion in one–time state funds for school districts. These one–time funds supported existing programs in 2008–09, thereby reducing the need for school districts to make midyear reductions or dip into emergency reserves.

Deferrals Allow Districts to Continue Spending. Beyond relying on new revenue sources, the state and school districts also relied heavily on borrowing. A large component of the K–12 spending reductions reflected payment deferrals ($2.9 billion in 2008–09 and $1.7 billion in 2009–10). That is, to allow districts to continue their current spending levels but still achieve state savings, the state delayed several K–12 education payments until the next fiscal year. As a result of this borrowing, school districts were able to sustain existing programs and postpone additional program cuts.

Districts Rely Heavily on Categorical Flexibility. The February and July packages made several significant policy changes to loosen restrictions and give school districts more discretion in making spending decisions. Among the biggest changes was the elimination of spending restrictions for roughly 40 categorical programs. Based on preliminary survey data collected by our office, school districts relied heavily on this newly granted flexibility. Generally, it appears many districts used the additional flexibility to transfer funding away from categorical programs to their core instructional activities. In particular, numerous school districts reduced their allocations for adult education, deferred maintenance, arts and music, and school and library improvement.

Reductions to Programs Still Needed. Although school districts were able to avoid many reductions because of the availability of one–time funds, borrowing, and additional categorical flexibility, many districts still had to make reductions to their programs in 2009–10. Based on preliminary information, school districts appear to be increasing class sizes across the board and laying off teachers. According to the California Teacher’s Association, 17,000 teachers (roughly 5 percent) were laid off at the end of the 2008–09 school year. Many districts also made reductions to classified noninstructional staff, such as custodians and bus drivers. Statewide summary data on the effect of these reductions, however, are not yet available.

As a result of budget reductions, an increasing number of school districts are having a difficult time remaining solvent. Based on reporting data from fall 2009, 117 districts are currently at risk of not meeting their financial obligations for the next two fiscal years. At this point last year, 90 school districts were at risk. This increase, however, is lower than anticipated considering the level of reductions districts have faced. At the time of the February 2009 budget, it was anticipated that the large budget reductions and deferrals could significantly affect the cash solvency of school districts. Since February 2009, however, only one school district has needed an emergency loan from the state to remain solvent. The large influx of ARRA funding has helped many school districts maintain favorable cash positions and meet monthly payment obligations despite state reductions.

Although larger funding reductions were made in prior years, most school districts are not likely to feel the full effects of Proposition 98 funding reductions until 2010–11. Figure 11 shows our estimates of “programmatic” funding for school districts from 2007–08 through 2010–11. These numbers reflect the amount of K–12 funding available for school districts to spend each year. As Figure 11 shows, most of the one–time revenues that were used in prior years will no longer be available in 2010–11. Based on a recent school finance survey we conducted, school districts spent approximately 20 percent of ARRA funds in 2008–09, are planning to spend 60 percent in 2009–10, and reserved 20 percent for 2010–11. Many also will have used up the restricted reserves that were made available by the flexibility proposals enacted last year. Given the loss of these funds, school districts would have roughly 11 percent less funding in 2010–11 under the Governor’s Budget compared to 2007–08 funding levels.

Figure 11

K–12 “Programmatic” Fundinga

(Dollars in Millions)

|

|

2007–08 Final

|

2008–09 Revised

|

2009–10 Revised

|

2010–11 Proposed

|

|

Programmatic Funding

|

|

|

|

|

|

K–12 ongoing fundingb

|

$48,883

|

$43,215

|

$40,765

|

$42,708

|

|

Payment deferrals

|

—

|

2,904

|

1,679

|

—

|

|

One–time fund swaps

|

862

|

1,766

|

—

|

64

|

|

Freed–up restricted reservesc

|

—

|

1,100

|

1,100

|

—

|

|

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) fundsc

|

—

|

1,192

|

3,575

|

1,192

|

|

Totals

|

$49,745

|

$50,176

|

$47,118

|

$43,964

|

|

Per–Pupil Programmatic Funding

|

|

|

|

|

|

K–12 attendance

|

5,947,758

|

5,957,111

|

5,921,510

|

5,927,728

|

|

K–12 per–pupil funding

|

$8,364

|

$8,423

|

$7,957

|

$7,417

|

|

Percent Changes From 2007–08

|

—

|

0.7%

|

–4.9%

|

–11.3%

|

The 2010–11 Governor’s Budget includes $1.9 billion in programmatic reductions to K–12 education. Three of the reductions are associated with policy proposals relating to school district and COE revenue limits. Specifically, the Governor proposes to limit the amount districts can spend on noninstructional activities, modify state restrictions on contracting out for noninstructional services, and consolidate COE services. The Governor also proposes to capture savings from the K–3 CSR program as well as apply a negative COLA to most K–12 programs. We find the Governor’s general approach toward making these reductions highly problematic, and, as discussed in Part I of this report, we recommend the Legislature take a more straightforward and transparent approach. In this section, we discuss our concerns with each of the Governor’s specific reduction proposals and offer alternative recommendations.

Under current law, revenue limit funding is provided to local school districts as unrestricted money with few strings attached. Based on the amount of revenue limit funding the state provides in a given year, local school districts decide how to allocate these general purpose dollars among competing priorities. These priorities typically include staffing levels at school sites as well as the central district office, staff compensation, materials and supplies, and other operating expenses.

Governor Proposes to Limit Amount of Funding That Can Be Spent on Noninstructional Activities. The Governor proposes to cut $1.2 billion from K–12 revenue limits and impose new limits on the local decision–making process. Specifically, each school district would be cut roughly $200 per ADA and required to reduce its total noninstructional spending by at least 12 percent from 2008–09 levels. The Governor specifies the categories of expenditures from which a district must make its reductions, including general administration, instructional supervision, and plant maintenance and operations. The 12 percent target is derived by taking $1.2 billion as a share of statewide spending on these categories (roughly $10 billion). On average, districts currently allocate about 19 percent of their budgets for these types of expenses. This share, however, differs significantly by district. For example, Plumas Lake Elementary, a district of about 1,000 ADA in Yuba County, spends about 31 percent of its budget on these categories, whereas Garden Grove Unified, a district with 47,500 ADA, spends about 17 percent, and Los Angeles Unified, a district of about 650,000 ADA, spends about 22 percent.

Proposal Has Serious Implementation Problems. We have serious concerns with how this proposal would be implemented. First, every district would be required to make the same proportional reduction to the targeted expenditure categories regardless of its current mix of spending on administration and instruction. Districts currently spending 30 percent of their budgets on these activities are treated the same as those spending 20 percent. Moreover, no allowance is made for districts that have recently made large reductions in these areas. (The Governor, however, would allow districts to apply for a waiver from this policy if they currently spend less than 15 percent of their total budget on these activities or if making the specified reductions would cause a district to require an emergency loan from the state.) Furthermore, it is unclear who would review expenditure data to ensure districts made reductions in the required places, how this policy would be enforced, and what the penalties would be for noncompliance. That district expenditure data are not available until several years after the close of the fiscal year makes monitoring compliance even more complicated.

Proposal Would Counteract Recent Flexibility Provisions. The Governor’s proposal also would work at cross–purposes with the flexibility options the state has recently granted to school districts. To help school districts respond to tough fiscal times, the 2009–10 budget package included numerous measures intended to increase local spending discretion. These included easing restrictions associated with more than 40 categorical programs and granting access to categorical fund balances. As it would place new limits on how districts can use general purpose funding, the Governor’s “one size fits all” proposal is antithetical to these other efforts.

Recommend Legislature Reject Governor’s Proposal, Preserve Local Decision–Making Power. We recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to place new limits on how much districts spend on noninstructional activities. Districts confronting budget reductions need new options for how to respond, not new constraints. Local school boards and their constituencies—through public budget meetings, the local education agency planning process, and local elections—are better positioned to decide how available monies should support districts’ specific needs and priorities.

Under current law, school districts can contract out for many noninstructional services (such as food service, maintenance, clerical functions, and payroll) only if certain conditions are met. For example, contracting out for services cannot result in the layoff or demotion of existing district employees.

Governor Proposes to Modify State Restrictions on Contracting Out. The Governor proposes to cut an additional $300 million from school district revenue limits (roughly $50 per ADA) and to modify restrictions that prohibit districts from contracting externally for noninstructional services. For example, districts would no longer be prohibited from contracting out based solely on savings they would get from lower contractor pay rates or benefits. They also would be able to layoff or demote a district employee who used to perform the service to be contracted out. Easing these restrictions would allow districts to more frequently bid on the open market for noninstructional services.

Proposal Could Result in Some Local Savings but $300 Million Overly Optimistic. To the extent local districts took greater advantage of contracting out, they likely would realize some cost savings at the local level. However, contractor availability, collective bargaining agreements, and existing service arrangements differ across the state, such that it is uncertain how much savings could be realized or how many districts would take advantage of the new flexibility. In a recent school finance survey we conducted, about 40 percent of responding districts indicated they likely would contract out for services if the restrictions were removed. Their estimates for how much they could save, however, varied greatly by district. We think assuming $300 million in associated savings is overly optimistic. Depending on the percent of noninstructional services contracted out and the incremental reduction in cost, we estimate total savings statewide could be as high as $250 million or as low as $50 million.

Savings Generated and Cut Applied Unlikely to Match. Given the proposed cuts are to be spread across all districts regardless of the amount of contract savings they are able to achieve, we also think it is highly unlikely that the savings a particular district generates will be well aligned with that district’s $50 per ADA revenue limit reduction.

Recommend Approving Contracting Out Proposal but Without Link to Revenue Limit Reduction. We think allowing districts to identify the most cost–effective options for meeting their needs makes sense. We therefore recommend the Legislature approve the Governor’s proposal to waive the restrictions on contracting out for noninstructional services. Nonetheless, we believe it is inappropriate to equate this proposal with an across–the–board revenue limit savings estimate, as individual districts could save more or less than their share of the $300 million cut. Thus, we recommend the Legislature make the statutory change on contracting without establishing any link to district revenue limit funding levels.

Under current law, the state provides COEs with general purpose funding—budgeted at about $330 million statewide—to provide statutory and discretionary services to their local school districts. While each COE uses this unrestricted portion of its revenue limit differently, activities generally include business support services, professional development, technology services, and credential monitoring for certificated staff.