The Governor proposes to dramatically restructure the way the state allocates funding to school districts, charter schools, and COEs. Similar to his proposal from last year, the Governor’s plan would replace existing revenue limit and categorical funding with a streamlined formula based on uniform per–pupil rates and supplemental funding for certain student groups. The proposal also would fund COEs to provide regional services to their local districts. The Governor refers to his collection of proposals as the LCFF. Perhaps most notably, the Governor’s proposed approach would contain very few spending or programmatic requirements.

This report is divided into two main sections—one focused on the changes that apply to school districts and charter schools and one focused on the changes that apply to COEs. In each of these sections, we begin by explaining the current funding system, then describe the Governor’s proposals, next assess the strengths and weaknesses of his approach, and finish by offering recommendations for how the Legislature might improve his proposals.

As described below, the Governor proposes major changes to the way the state allocates funding to school districts and charter schools.

Being familiar with both the basic components and widespread criticisms of the state’s existing school funding system is an essential first step in understanding the rationale behind the Governor’s proposed changes.

Current Funding System Based on Revenue Limits and Categorical Programs. The state’s current approach to allocating funding to school districts consists primarily of revenue limits (general purpose funds) and categorical programs (grants that carry specific spending and programmatic requirements). In 2012–13, the state spent about $47 billion in Proposition 98 funds for K–12 education, of which approximately three–quarters (roughly $36 billion) was provided through revenue limits and about one–quarter (roughly $11 billion) was allocated via individual categorical grants. (As described below, however, almost half of this categorical funding has essentially become general purpose funding in recent years.) Revenue limits currently are continuously appropriated, while most categorical programs currently are appropriated through the annual budget act.

Spending Requirements Temporarily Suspended for Some Programs. To assist districts in dealing with tight budgets, in 2009 the state suspended categorical program requirements for roughly 40 of the state’s 60 categorical programs. As a result, districts were granted discretion to use the $4.7 billion associated with these programs for any purpose. (A small portion of these funds are allocated to COEs.) According to surveys our office has conducted in recent years, most districts have responded to this flexibility by redirecting the majority of funding away from most of the affected categorical programs to other local purposes. The current flexibility provisions are scheduled to expire at the end of 2014–15.

Categorical System Has Major Shortcomings. As our office has discussed numerous times in prior years, the existing approach—particularly having so many categorical programs—has major shortcomings. First, little evidence exists that the vast majority of categorical programs are achieving their intended purposes. This is in part because programs are so rarely evaluated. Second, separate categorical programs often contain overlapping goals but distinct requirements. This magnifies the difficulty districts have in offering comprehensive services to students. It also blurs accountability and increases administrative burden. Third, having so many different categorical programs with somewhat different requirements creates a compliance–oriented system rather than a student–oriented system. These problems are further exacerbated by categorical programs that have antiquated funding formulas, which over time have become increasingly disconnected from local needs.

Broad Consensus That Current Funding System Is Deeply Flawed. For all these reasons, several research groups over the last decade have concluded that California’s K–12 finance system is overly complex, irrational, inefficient, and highly centralized. Although recent categorical flexibility provisions have temporarily decentralized some decision making, the provisions have done little to make the funding system more rational, linked to student needs, or efficient.

Generally, the Governor proposes to replace the numerous streams of funding the state currently sends to school districts with one simplified formula. (All proposals for districts also would apply to charter schools.) Below, we begin with a general overview of the Governor’s proposal and then describe the various components of the proposal in greater detail.

Replaces Existing System With New Funding Formula, Removes Most Spending Requirements. The Governor’s new LCFF would replace revenue limits and most categorical programs with a more streamlined formula and remove most existing spending restrictions. As a result, the majority of currently required categorical activities—including purchasing instructional materials, conducting professional development, and providing supplemental instruction—instead would be left to districts’ discretion. Figure 1 displays the existing Proposition 98–funded categorical programs that would be eliminated and the associated funding that would become part of the new formula. (Federally funded grants would remain unaffected by the LCFF.) As shown, the proposal affects most of the programs and an associated $3.8 billion currently subject to flexibility provisions, as well as an additional six programs and $2.3 billion for which programmatic requirements currently still apply. (As described in more detail later, the Governor also would allow two programs totaling $1.3 billion to remain as permanent add–ons to the new formula.)

Figure 1

Categorical Programs Governor Would Consolidate Into Local Control Funding Formulaa

2012–13 (In Millions)

|

Program

|

Amount

|

|

Currently Flexible

|

|

|

Adult Education

|

$634

|

|

Regional Occupational Centers and Programs

|

384

|

|

School and Library Improvement Block Grant

|

370

|

|

Summer School Programs

|

336

|

|

Instructional Materials Block Grant

|

333

|

|

Charter School Block Grant

|

282

|

|

Deferred Maintenance

|

251

|

|

Professional Development Block Grant

|

218

|

|

Grade 7–12 Counseling

|

167

|

|

Teacher Credentialing Block Grant

|

90

|

|

Arts and Music Block Grant

|

88

|

|

School Safety

|

80

|

|

High School Class Size Reduction

|

79

|

|

Pupil Retention Block Grant

|

77

|

|

California High School Exit Exam Tutoring

|

58

|

|

California School Age Families Education

|

46

|

|

Professional Development for Math and English

|

45

|

|

Gifted and Talented Education

|

44

|

|

Community Day School (extra hours)

|

42

|

|

Community–Based English Tutoring

|

40

|

|

Physical Education Block Grant

|

34

|

|

Alternative Credentialing

|

26

|

|

Staff Development

|

26

|

|

School Safety Competitive Grant

|

14

|

|

Educational Technology

|

14

|

|

Certificated Staff Mentoring

|

9

|

|

Specialized Secondary Program Grants

|

5

|

|

Principal Training

|

4

|

|

Oral Health Assessments

|

4

|

|

Otherb

|

5

|

|

Subtotal

|

($3,804)

|

|

Newly Consolidated

|

|

|

K–3 Class Size Reduction

|

$1,326

|

|

Economic Impact Aid

|

944

|

|

Partnership Academies

|

21

|

|

Foster Youth Programs

|

15

|

|

Community Day Schools (for mandatorily expelled)

|

7

|

|

Agricultural Vocational Education

|

4

|

|

Subtotal

|

($2,318)

|

|

Total

|

$6,122

|

|

Maintained as Permanent Add–Ons to Formula:

|

|

|

Targeted Instructional Improvement Block Grantc

|

$855

|

|

Home–to–School Transportationc

|

491

|

Maintains a Few Categorical Programs. While the Governor’s proposed new funding formula would incorporate most existing state categorical programs, he would maintain a few Proposition 98 programs, totaling $5.7 billion, with their existing allocation formulas and requirements. Figure 2 lists these programs and the rationale for excluding them from the new formula. As described in the figure, these programs tend to serve unique populations or involve specialized spending requirements. Not listed in the figure are two existing K–12 activities—adult education and apprenticeship programs—which under the Governor’s proposal would remain as discrete categorical programs but would be administered by community colleges instead of school districts. (For more information on these proposals, please see our report,

The 2013–14 Budget: Proposition 98 Education Analysis.)

Figure 2

Governor Would Exclude a Few Categorical Programs From New Formula

2013–14 (In Millions)

|

Program

|

Reason for Exclusion

|

Amounta

|

|

Special Education

|

Federal law requires state to track and report specific expenditure level. Also, majority of funding is allocated to regional entities rather than individual LEAs.

|

$3,740b

|

|

After School Education and Safety

|

Voter–approved initiative precludes major changes to funding allocation or activities (Proposition 49, 2002).

|

547

|

|

State Preschool

|

Funding supports unique population and set of activities. Not part of core K–12 mission.

|

481

|

|

Quality Education Investment Act

|

Scheduled to sunset in 2014–15.

|

313

|

|

Child Nutrition

|

Federal law requires state to track and report specific expenditure level.

|

157

|

|

Mandates Block Grant

|

Linked to constitutional requirements to fund mandates.

|

267

|

|

Assessments

|

Necessary to meet state and federal accountability requirements.

|

75

|

|

American Indian Education Centers and Early Childhood Education Program

|

Funding supports unique population and set of activities. Not part of core K–12 mission.

|

5

|

|

Total

|

$5,685

|

New Formula Would Build Towards Uniform Per–Pupil Rates, Four Supplemental Grants. Under the current system, districts receive notably different per–pupil funding rates based on historical factors and varying participation in categorical activities. In contrast, under full implementation of the new system proposed by the Governor, all districts and charter schools would receive the same per–pupil rates, adjusted by a uniform set of criteria. Figure 3 highlights the major characteristics of the Governor’s proposal, which we describe in detail below. As shown in the figure, the proposal would provide a base per–pupil rate for each of four grade–span levels. These base rates would be augmented by four funding supplements. The Governor’s proposal establishes target base rates that, when combined with the proposed supplements, exceed the per–pupil funding levels the vast majority of districts currently receive. As such, the administration estimates it would take several years to reach the target funding levels. The Governor’s 2013–14 budget includes $1.6 billion to begin building towards the target rates. Initial implementation of the new formula—and removal of categorical spending requirements—would begin in 2013–14. Moreover, all LCFF funds would be continuously appropriated beginning in 2013–14.

Figure 3

Overview of Governor’s Local Control Funding Formula for School Districtsa

|

Formula Component

|

Proposal

|

|

Target amount for base grant (per ADA)

|

- K–3: $6,342

- 4–6: $6,437

- 7–8: $6,628

- 9–12: $7,680

|

|

Supplemental funding for specific student groups (per EL, LI, or foster youth)

|

- 35 percent of base grant.

- Provides EL students with supplemental funding for maximum of five years (unless students also are LI).

|

|

Supplemental concentration funding

|

- Each EL/LI student above 50 percent of enrollment generates an additional 35 percent of base grant.

|

|

Supplemental funding for K–3 and high school students (per ADA)

|

- K–3: 11.2 percent of base grant.

- High school: 2.8 percent of base grant.

|

|

Higher level of funding for necessarily small schools

|

- Provides minimum grant (rather than ADA–based funding) for very small schools located in geographically isolated areas.

|

|

“Add–ons” to new formula

|

- Locks in existing Targeted Instructional Improvement Block Grant and Home–to–School Transportation district–level allocations and provides as permanent add–ons to the new formula.

|

|

Spending requirements

|

- Removes all categorical spending requirements for programs included in formula and two add–ons, effective 2013–14.

- Requires that EL/LI and concentration supplemental funds be spent for a purpose that benefits EL/LI students.

- When fully implemented, only provides K–3 supplement if district’s K–3 class sizes do not exceed 24 students, unless collectively bargained to another level.

- Requires districts to develop, make publicly available, and submit to the local COE an annual plan for how they will spend funding and improve student achievement.

|

|

Transition plan

|

- Uses portion of annual growth in Proposition 98 funding to gradually increase each district’s funding rate up to the target level. Districts that currently have lower rates would get larger per–pupil funding increases each year.

- Estimates full implementation by 2019–20.

|

Sets Grade–Specific Target Base Grants. Figure 3 displays the proposed per–pupil target base funding rates for each of the four grade spans. The proposed variation across the grade spans is based on the proportional differences in existing charter school base rates. The distinctions are intended to reflect the differential costs of providing education across the various grade levels. The target rates reflect current statewide average undeficited base rates. That is, the targets reflect what average revenue limit rates would be in 2012–13 if the state restored all reductions from recent years (roughly $630 per pupil) and increased rates for cost–of–living adjustments (COLAs) that school districts did not receive between 2008–09 and 2012–13 (roughly $940 per pupil). The Governor also proposes to annually adjust these rates by the statutory COLA rate, beginning in 2013–14. (The current estimated COLA rate for 2013–14 is 1.65 percent.) Base rate funds would be allocated based on average daily attendance (ADA) in each grade level.

Provides Four Supplemental Grants. In addition to the base funding rate districts would receive for each student they serve, the LCFF would provide supplemental funds based on four specific criteria. Specifically, districts would get additional funding for certain student groups, high concentrations of these groups, K–3 students, and high school students. We describe each of these four funding supplements in detail below.

Provides Supplemental Funding for Certain Student Groups. Under the current system, districts receive funding through the Economic Impact Aid (EIA) program to provide supplemental services for students who are EL and from LI families. In lieu of EIA, the proposed LCFF would provide districts with an additional 35 percent of their base grant for these same student groups. For example, an EL or LI student in grades K–3 would generate an additional $2,220 for the district (35 percent of $6,342, the K–3 target base rate). The Governor would provide these supplements for students who (1) are EL, (2) receive free or reduced price meals (FRPM), or (3) are in foster care. The formula would count each student only once for the purposes of generating the supplement. (Because all foster youth are eligible for FRPM, throughout this report we typically include them when referencing the LI student group.) As shown in Figure 4, the Governor’s proposed EL/LI supplement differs from the existing EIA program in several notable ways.

Figure 4

Comparing Proposed and Existing Methods of Funding EL and LI Students

|

|

- Changes Measure of LI. For the purposes of calculating the EL/LI funding supplement, the Governor’s proposal would count students as LI if they receive a free or reduced price meal. The current Economic Impact Aid (EIA) formula instead uses federal Title I student counts as the measure for funding students from LI families.

|

- Includes Funding for Foster Youth. Under the Governor’s proposal, supplemental funding for foster youth would be funded through the EL/LI supplement. Currently, special services for foster youth are funded through a separate categorical grant, not through EIA.

|

- Individual Students Generate Only One Supplement. The Governor’s proposal would count each student who meets more than one of the EL/LI characteristics only once for the purposes of calculating supplemental funding. In contrast, the EIA formula currently provides double funding for EL students who also are from LI families.

|

- Provides Notably More Supplemental Funding. The proposed 35 percent supplement would generate notably more funding for most districts than the supplemental funds provided through existing categorical programs. Currently, EIA provides districts with an average of $350 per EL or LI student, or an average of $700 for students who meet both criteria. Additional existing categorical programs intended to serve these students provide an average of $75 per EL/LI student. The new formula rates would range from $2,220 to $2,688 per EL/LI student, depending upon the grade level.

|

- Links Supplement to Level of Funding for General Education. The Governor’s proposed approach explicitly would link the amount the state provides in supplemental funding to the amount provided for general education services, such that when the base amount increases, so would the supplement. Currently, the amount provided for EIA is not directly connected to how much is provided for other education services.

|

- Institutes Time Limit for EL Funding. The Governor’s proposal would cap the amount of time an EL student could generate supplemental funds at five years (though districts could decide to continue spending more on the student and the student would continue to generate more funding if also LI). Currently, EL students can generate EIA funding until they are reclassified as being fluent in English, even if this takes 13 years.

|

- Provides More Flexibility Over How Supplemental Funds Could Be Spent. The Governor’s proposal provides districts with greater discretion over how to use the EL/LI funds compared to current requirements for EIA funds. Districts would be required to use the supplemental funds to meet the needs of their EL/LI student groups, but they would have broad flexibility in doing so. Current law is more stringent, in that the state requires and monitors that districts use EIA funds to provide supplemental services for the targeted student groups beyond what other students receive.

|

Calculates EL/LI Student Supplement Based on Districtwide Averages, Not Grade–Specific Student Counts. To calculate each district’s EL/LI student supplement, the formula assumes the districtwide proportion of EL/LI students also applies in each grade span level. For example, if 60 percent of the students enrolled in a unified district were EL/LI, the formula would calculate a supplement for 60 percent of students in each grade span level—even if the actual proportions of EL/LI students differ across the grade spans.

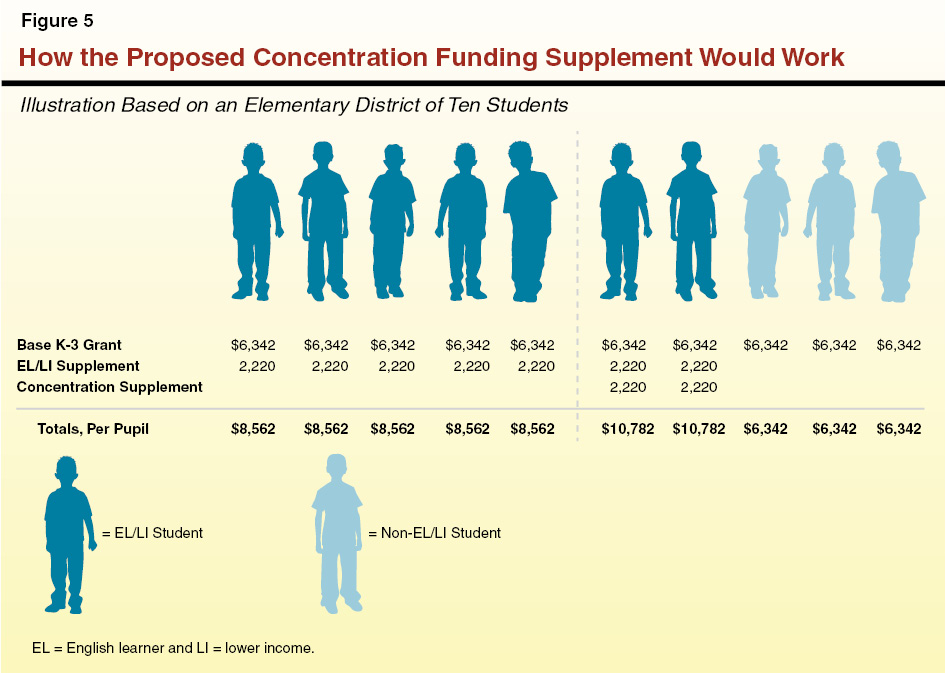

Provides Supplemental Funding to Districts With Higher Concentrations of EL/LI Students. The Governor’s proposal provides an additional funding supplement to districts whose EL/LI student populations exceed 50 percent of their enrollment. Specifically, districts would receive an additional 35 percent of their grade span base grant for each student above the 50 percent threshold. (For the purposes of calculating this supplement, a charter school’s EL/LI concentration could not exceed that of the closest school district.) Figure 5 illustrates how concentration funding would work. As shown, all EL/LI students in the illustrative district would generate a $2,220 supplement (35 percent of the base grant), but those comprising more than half of the district’s enrollment would generate an additional $2,220. (As with the EL/LI student supplement, the concentration supplement also would be calculated assuming the districtwide proportion of EL/LI students is applied to each grade span.) The existing EIA formula also provides supplemental funds for districts where more than half of the student population are EL/LI; however, students over the 50 percent threshold only generate an additional half EIA supplement, rather than double the supplement.

Requires That Districts Use EL/LI and Concentration Supplemental Funds to Benefit EL/LI Students. The Governor would require that districts use the supplemental EL/LI and concentration funds for purposes that “substantially benefit” the target student groups. These spending parameters are somewhat broader than current EIA constraints, which explicitly require that EIA funds be used to provide supplemental services beyond what other students receive. In the initial implementation years of the LCFF, interim spending requirements would apply. Specifically, in 2013–14 and until target funding levels have been achieved, districts would have to demonstrate they spent at least as much on services for EL/LI students as they did in 2012–13.

Provides Supplemental Funding for K–3 Students. Currently, the state funds a categorical program designed to provide additional funding to districts if they offer smaller class sizes in grades K–3. The proposed LCFF would continue this practice. Specifically, the formula would provide an additional 11.2 percent of the K–3 base grant for students in these grades ($710 per ADA based on the target K–3 rate). The Governor intends that districts use these funds to maintain classes of 24 or fewer students in these grades. Once all districts have reached their LCFF funding targets, a district only would receive these funds if it maintains K–3 class sizes of 24 or less—unless the district and local teachers’ union agreed through collective bargaining to larger class sizes. (In the years before the formula is fully implemented, districts would have to “make progress” toward K–3 class sizes of 24, unless collectively bargained otherwise.)

Provides Supplemental Funding for High School Students. The Governor also proposes to provide districts with supplemental funding for high school students—in addition to the higher 9–12 per–pupil base rate. This supplement is intended to replace the categorical program funding high schools currently receive for career technical education (CTE) services. (Regional Occupational Centers and Programs, or ROCPs, is the largest of the existing CTE programs proposed for consolidation under the Governor’s approach.) Specifically, the supplement would provide districts with an additional 2.8 percent of the high school base grant (or about $215 per ADA based on the target 9–12 rate). The proposal intends this funding be used to provide CTE, but districts would have discretion to spend the funds for any purpose.

Maintains Two Large Existing Grants as Add–Ons to New Formula. The Governor proposes to maintain existing funding allocations for two of the largest categorical programs—Targeted Instructional Improvement Block Grant (TIIG) ($855 million) and Home–to–School (HTS) Transportation ($491 million)—separate from the new LCFF. Unlike the other categorical programs the Governor explicitly excludes from the new formula, however, spending requirements for these two programs would be permanently repealed. Additionally, existing district allocations would be permanently “locked in,” regardless of subsequent changes in student population.

Modifies Basic Aid Calculation. The Governor proposes to change how local property tax (LPT) revenue factors into K–12 funding allocations, which could change whether districts fall into basic aid status. (See the nearby box to learn about basic aid districts and how they are treated under current law.) Currently, a district’s LPT allotment serves as an offsetting revenue only for determining how much state aid it will receive for revenue limits, not for categorical aid. The Governor proposes to count LPT revenues as an offsetting fund source for the whole LCFF allocation—base grant and supplements. The proposal, however, has one notable exemption. All districts (including basic aid districts) would be given the same level of per–pupil state categorical aid they received in 2012–13 into perpetuity. Thus, in the future a basic aid district with LPT revenue that exceeded its total LCFF grant would maintain this additional LPT revenue and also receive its 2012–13 per–pupil state allocation.

In most school districts, revenue limit funding is supported by a combination of both local property tax (LPT) revenue and state aid. For some districts, however, the amount of LPT revenue received is high enough to exceed their calculated revenue limit entitlements. These districts are referred to as basic aid or “excess tax” districts. (The term basic aid comes from the requirement that all students receive a minimum level of state aid, defined in the State Constitution as $120 per pupil, regardless of how much LPT revenue their district receives.) Generally, basic aid districts are found in communities that have (1) historically directed a higher proportion of property taxes to school districts, (2) relatively higher property values, and/or (3) comparatively fewer school–age children. In 2011–12, 126 of the state’s 961 school districts were basic aid. These districts retained the LPT revenue in excess of their revenue limits and could use it for any purpose. The amount of excess tax revenue each basic aid district received in 2011–12 varied substantially, but was typically about $3,000 per pupil. Under current law, basic aid districts do not receive any state aid for their revenue limits, but they do receive state categorical aid similar to other school districts.

Continues Alternative Funding Approach for Necessarily Small Schools (NSS), but Tightens Eligibility Criteria. Under current law, schools that are located specified distances from a comparable school in the same district and whose ADA falls below certain thresholds are defined as NSS. Because of their small size, an ADA–based funding formula would not generate sufficient revenue for NSS to operate. As such, NSS currently receive a general purpose block grant instead of—and in an amount exceeding—per–pupil revenue limits. The Governor proposes to maintain this practice, providing NSS with a block grant in lieu of an ADA–based LCFF grant. The Governor’s proposal changes the definition for NSS, however, such that only geographically isolated schools would be eligible for the additional funds. This would eliminate an existing statutory clause that allows a school to claim NSS status (and additional funding) even if it is located near a similar public school, provided it is the only school in the district. Many schools currently receive NSS funding by virtue of being a school district consisting of a single school, not because they are geographically isolated.

Permanently Repeals Facility Maintenance Spending Requirements. Spending requirements related to facility maintenance are among the many existing activities slotted for elimination under the Governor’s proposed approach. Prior to 2009, school districts receiving state general obligation bond funding for facilities were required to deposit 3 percent of their General Fund expenditures in a routine maintenance account. In addition, districts received one–to–one matching funds for deferred maintenance through a discrete categorical program. Under the temporary categorical flexibility provisions adopted in 2009, the routine maintenance requirement decreased from 3 percent to 1 percent. These flexibility provisions also allowed school districts to use deferred maintenance categorical funds for any purpose and suspended the local match requirement. The Governor’s proposal would permanently remove all state spending requirements as well as dedicated funding for both routine maintenance and deferred maintenance. How much LCFF funding to dedicate for facility needs would be left to individual districts’ discretion.

Reestablishes Minimum School Year of 180 Days in 2015–16. In addition to suspending facility maintenance requirements, in recent years the state temporarily allowed districts to reduce their school year by up to five instructional days without incurring fiscal penalties—dropping the requirement from 180 to 175 days. These provisions currently are scheduled to expire in 2015–16. The Governor’s proposal would maintain this plan and reestablish the 180 day requirement after two more years.

Replaces Most State Spending Restrictions With Annual District Plans. As opposed to specific programmatic requirements, the Governor’s proposal would require districts to document how they plan to educate their students. Specifically, concurrent with developing and adopting their annual budgets, districts would annually develop and adopt a “Local Control and Accountability Plan.” Figure 6 displays the required components of this plan. The Governor would require the State Board of Education to adopt a specific template for these district plans that also incorporates existing federal plan requirements. District accountability plans would be approved by local school boards, made publicly available for community members, and submitted to COEs for review.

Figure 6

Required Components of Proposed Local Control and Accountability Plans

|

|

|

Goals and Strategies for:

|

- Implementing the Common Core State Standards.

|

- Improving student achievement, graduation rates, and school performance.

|

- Providing services for EL students, LI students, and children in foster care.

|

- Increasing student participation in college preparation, advanced placement, and CTE courses.

|

- Employing qualified teachers, providing sufficient instructional materials, and maintaining facilities.

|

- Providing opportunities for parent involvement.

|

|

Analysis of:

|

|

|

- Progress made in implementing goals since the prior year.

|

|

Cost Projections for:

|

|

|

- Meeting the needs of EL, LI, and foster students (projected costs must equal amount of supplemental funds received for those groups).

|

Requires That COE Budget Approval Process Incorporate Review of District Accountability Plans. The COEs would be required to review district plans in tandem with their annual review and approval of district budgets. While the COE would not have the power to approve or disapprove a district’s accountability plan, approval of the district’s budget now would be additionally contingent on the COE confirming that (1) the plan contains the required components listed in Figure 6 and (2) the budget contains sufficient expenditures to implement the strategies articulated in the plan.

Most Districts Currently Funded Below LCFF arget Levels. The administration estimates the cost of fully implementing the new system to be roughly $15.5 billion, plus additional funding for annual COLAs moving forward. As the state does not yet have sufficient available funds to meet this need, the proposal would gradually increase districts’ funding until they reached their target levels. Each district’s “current base” would be calculated according to the amount it received in 2012–13 from revenue limits and the categorical programs included in the LCFF. Based on the administration’s estimates, this calculation yields an amount lower than LCFF target levels for about 90 percent of districts. Most districts, therefore, would receive per–pupil funding increases in 2013–14 and future years. In contrast, districts with current funding bases that meet or exceed their new LCFF targets (plus COLA) would not receive additional funds in 2013–14, but they would be held harmless against per–pupil funding losses.

Phases–In New Formula as New Funding Becomes Available. The proposed 2013–14 budget provides $1.6 billion—or about 10 percent of the total implementation cost—to begin the process of implementing the new formula. Consequently, in 2013–14 most districts would receive funding increases such that they move about 10 percent closer to their new funding targets. Districts whose existing funding levels are close to their target levels would receive less new funding per pupil than those that currently are farther away from their targets, but the same proportional share of each district’s individual funding “gap” would be reduced. The Governor plans that over the next several years, roughly half of the annual growth in K–12 Proposition 98 funds would be allocated to implement the new funding system (with the other half used to pay down deferrals). Under this approach (and based on the administration’s revenue estimates), the Governor estimates the new funding formula could be fully implemented—with each district funded at the COLA–adjusted target levels plus supplemental grants—by 2019–20.

We believe the Governor’s proposed LCFF represents a positive step in addressing the many problems inherent in the state’s existing K–12 funding approach. As such, we believe many components of the proposal merit serious legislative consideration. We are concerned, however, that some elements of the Governor’s approach either miss opportunities to address existing issues or could create new problems. Below, we discuss our assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the Governor’s proposed funding formula for school districts and charter schools. Figure 7 summarizes our assessment.

Figure 7

Strengths and Weaknesses of Governor’s Approach

|

|

|

Strengths

|

- Is simple and transparent.

|

- Funds similar students similarly.

|

- Sets reasonable target base rates.

|

- Links funding to students’ needs.

|

- Sets reasonable supplemental EL/LI rate.

|

- Sets reasonable expectations for EL students.

|

- Provides more flexibility in addressing local priorities.

|

- Refocuses state and local responsibilities.

|

- Increases funding for vast majority of districts while progressing towards uniform target rates.

|

|

Weaknesses

|

- Perpetuates irrational funding differences by preserving two add–on programs.

|

- Does not ensure supplemental funding translates to supplemental services for EL/LI students.

|

- Does not target concentration funding to those districts with highest concentrations of EL/LI students.

|

- Supplement calculation could more accurately reflect student need.

|

- Adds unnecessary complexity by including separate K–3 and high school supplement.

|

- Maintains historical advantages for basic aid districts.

|

- Does not adequately protect investments in facilities.

|

Is Simple and Transparent. Currently, the state’s categorical programs, as well as the broader education funding system, are based on overly complex and complicated formulas. Very few policy makers, taxpayers, school board members, or parents understand or can explain why a particular district receives a particular level of funding. In contrast, the Governor’s proposed LCFF would distribute the vast majority of K–12 funds at uniform per–pupil rates with a few easily understandable, consistently applied adjustment factors. The transparency of such a simple system could in turn help engender greater public understanding, involvement, and confidence in local school budgets and decisions.

Funds Similar Students Similarly. Because today’s K–12 funding system largely is based on outdated data and historical formulas, funding across districts varies in illogical ways. For example, similar students attending similar schools may be funded at different rates simply because they attend (1) a charter school rather than a district school, (2) a single–school district rather than a multi–school district, or (3) a district that applied to participate in a particular categorical program decades earlier. Under the Governor’s proposal, funding rates would be based on current data and consistent criteria. This approach would address longstanding and arbitrary funding distinctions across districts (including single–school districts currently claiming NSS funding located close to other districts) and between districts and charter schools. Subsequent funding differences would be due to differences in student populations, such that similar students attending similar schools would receive similar levels of funding.

Sets Reasonable Target Base Rates. The Governor’s approach to developing target base rates generally is reasonable. The proposed rates would restore reductions made over recent years, including foregone COLAs, and subsequently would increase funding levels for the vast majority of districts. The Legislature could use other methods to set the target base rates, however, which also would be reasonable. (See nearby box for a description of one alternative approach.) Regardless of the specific approach, we believe the policy of setting target rates that exceed existing levels but are attainable within a few years is reasonable.

The Governor proposes to set target base funding rates based on the statewide average undeficited revenue limit rate. This generates a statewide average target rate of about $6,800, which the Governor then converts into four unique grade span rates. An alternative approach would be to set the target rate based on the amount the state currently provides for general education services plus funding to address base reductions made in recent years. The average rate derived by this alternative approach totals about $6,200, or approximately $600 lower than the Governor’s proposed rate. Under this approach the state would develop target rates by adding:

- Existing average revenue limit levels ($5,250).

- An amount equal to the average base revenue limit reductions made in recent years ($630).

- Average per–pupil categorical funding that districts currently receive to serve the general student population ($320). This estimate includes average funding rates for programs intended to benefit all students, such as the Professional Development Block Grant, the Instructional Materials Block Grant, and the Arts and Music Block Grant.

We suggest this approach as an option because it approximates what the state is providing in general purpose funding today plus funding to address recent base reductions in general purpose funding. We exclude from these estimates the funding associated with existing programs intended to serve specific student groups, given that the Governor’s proposed supplements would be designed to take the place of most of those programs. This approach also excludes funding associated with foregone cost–of–living adjustments (COLAs), as no other state program is receiving foregone COLAs.

Links Funding to Students’ Needs. While the administration’s specific grade span differential rates and 35 percent supplemental funding rate for EL/LI students might not exactly reflect associated costs, we believe the underlying policy of providing additional funds based on student needs makes sense. Providing increasing levels of funding for different grade spans recognizes the higher costs of providing an education to older students. Specifically, instructional minute requirements and facility and equipment needs tend to increase as students progress through the grades. (High school costs are particularly high because they must offer college and career readiness training, which tends to require more specialized classes, facilities, and materials.) Similarly, providing supplemental funds for EL and LI students recognizes that to be successful, these students frequently require services above and beyond the education program the district provides to all students. (These supplementary support services often include tutoring, counseling, health services, smaller class sizes, and specialized educational materials.)

Sets Reasonable Supplemental EL/LI Rate. In an attempt to assess the appropriateness of the Governor’s proposed EL/LI supplement, we conducted a review of “weights” used in other states and suggested by relevant academic literature. Our research found that the Governor’s proposed 35 percent supplement is somewhat high but falls within the range of practices used and mentioned elsewhere. (Please see the nearby box for a more detailed discussion of our findings.) The lack of agreement across states and the literature, however, indicates there is no “perfect” or “correct” amount of funding for EL/LI students. These findings suggest the Legislature reasonably could adopt the Governor’s proposed rate or opt for a somewhat different rate and still meet the important policy objectives addressed by his proposal.

Other States’ Supplements Vary Widely. California is not the first state to grapple with how much additional funding to provide for meeting the additional needs of EL/LI students. Our review of the roughly 60 percent of other states that provide such supplements found that funding rates vary notably. States also vary in their approaches to providing supplemental funding, with some taking the “weighted” approach the Governor proposes using in his new formula, and others providing block grants similar to California’s existing Economic Impact Aid categorical program. Additionally, most states provide separate supplemental funding streams for EL and LI students rather than a combined supplement to serve both populations as proposed by the Governor. Based on our review, the Governor’s proposed supplemental rate (35 percent of the general education rate) is higher than the rate provided for either EL or LI students in most other states. A few states, however, provide notably more for EL–specific supplements.

Research Findings Also Differ Significantly. Our review of academic research on EL/LI students revealed a similar lack of consensus regarding the “right” level of supplemental funding to provide. For example, one California–specific study suggested an additional 23 percent of “base” education funding would be sufficient to support the needs of LI students, but an additional 32 percent would be needed for EL students. Another study (conducted in a different state) found that LI students require twice as much funding as their mainstream peers, and EL students require three times as much.

Sets Reasonable Expectations for EL Students. Having a working knowledge of English is crucial if students are to be able to access the school curriculum. By establishing a five–year time limit for EL students to generate supplemental funds, the Governor appropriately focuses attention on providing intensive initial services. (Because of the spending discretion built into the Governor’s proposal, the new timeline would not preclude districts from continuing to provide language services for those students who continue to need them after five years.) Moreover, almost two–thirds of EL students across the state (and many more in some districts) also are LI, so most districts would continue to receive supplemental funding for most EL (and former EL) students even after five years. As such, we believe the Governor’s proposal sends an important message and creates a corresponding fiscal incentive for districts to focus on EL students’ language needs in their initial schooling years, while in most cases maintaining supplemental funds for students who may continue to require additional services thereafter.

Provides More Flexibility in Addressing Local Priorities. As a result of the state’s approach to categorical funding, today’s K–12 educational delivery system largely is state–directed—districts’ activities and programs are prescribed rather than developed based on local needs. While the state has temporarily suspended many spending requirements in recent years, most of these flexibility provisions currently are scheduled to expire at the end of 2014–15. The Governor’s plan would allow districts to retain and increase local discretion over almost all Proposition 98 funds, enabling districts to more easily dedicate resources to local priorities. This flexibility would give districts the opportunity to pursue innovative and locally driven activities that may not be feasible under current state programmatic requirements.

Refocuses State and Local Responsibilities. Given the state now has a rather extensive accountability system for monitoring student outcomes, the rationale for the state to so closely monitor educational inputs—or specific district activities—has become less compelling. The Governor’s proposal to repeal most categorical spending requirements would help to refocus responsibilities at both the state and local levels. The state’s primary focus could shift from monitoring compliance with spending rules to monitoring student performance and intervening when districts show signs of struggling. Districts could shift their focus from complying with state requirements to best meeting the needs of their students. Moreover, communities could more confidently hold local school boards and superintendents accountable for district outcomes, since under the new system local entities—not the state—would largely be in charge of designing instructional programs.

Increases Funding for Vast Majority of Districts While Progressing Towards Uniform Target Rates. By simultaneously raising funding levels for the vast majority of districts and equalizing rates across districts, the Governor’s approach concurrently addresses two important policy goals. Over the past few years, all districts have experienced budget cuts. While addressing existing disparities across districts is important, so too is ensuring that all districts are able to address the programmatic effects of recent budget reductions, such as larger class sizes and shorter school years. The Governor’s proposal recognizes these needs and would increase funds across the majority of districts. At the same time, the proposed approach would provide districts that are further away from their targets with comparably greater annual funding increases. This approach is similar to how the state has equalized disparities in district revenue limit rates in prior years.

Perpetuates Irrational Funding Differences by Preserving Two Add–On Programs. To improve a funding system he describes as “deeply inequitable,” the Governor consolidates the majority of existing categorical programs into his new formula. Excluding two of the largest and most outdated among them, however, perpetuates funding disparities across districts. Both the TIIG and HTS Transportation programs have outdated formulas that allocate funds disproportionately across districts for no justifiable reason. For example, HTS Transportation allocations are based more on historical costs than existing transportation needs, and nearly 60 percent of funding from the $855 million TIIG program is allocated to just one school district. Furthermore, removing the spending requirements and locking–in existing allocations negates any argument that the programs are being maintained because they currently serve an important function.

Does Not Ensure Supplemental Funding Translates to Supplemental Services for EL/LI Students. We are concerned that the Governor’s proposed approach to ensuring districts serve EL/LI students—requiring them to document how they plan to spend funding for these students—does not provide sufficient assurance that EL/LI students would receive services in addition to those that all students receive. While COE budget reviews presumably would confirm that supplemental funds would somehow benefit EL/LI students, the COE would not be empowered to intervene if the funds were not being used effectively or in a targeted way. Under the proposal, for example, a district could choose to spend the supplemental funds to provide an across–the–board salary increase for teachers, justifying this approach by stating that offering higher salaries would provide EL/LI students (and all other students in the district) with higher quality teachers. This type of approach, however, “spreads” the benefit of the supplemental funds and does not result in additional services for the students with additional needs who generated the additional funding.

Does Not Target Concentration Funding to Those Districts With Highest Concentrations of EL/LI Students. The Governor’s proposal recognizes that as a district’s concentration of EL/LI students increases, the need for, intensity of, and costs associated with supplemental services also tend to go up. We believe the Governor’s threshold for providing the concentration supplement, however, is too low to focus additional funds on those districts that face disproportionately greater challenges. Currently, half of all districts in the state have EL/LI student populations making up at least 50 percent of their enrollment. Thus, under the Governor’s proposal, half of all districts would receive supplemental concentration funding. By setting this relatively low threshold, the Governor does not prioritize funding for districts facing extraordinary levels of additional need over those facing what are essentially average levels of need (which the base grant itself presumably is intended to address).

Supplement Calculation Could More Accurately Reflect Student Need. The Governor’s approach to calculating individual districts’ EL/LI student supplement misses an opportunity to more closely align funding with student need. The Governor’s proposal uses districtwide averages of EL/LI students to calculate supplements across grade spans, rather than using the counts of how many EL/LI students actually are enrolled in each grade level. Grade–specific information on EL/LI students is available and would allow a more accurate calculation of supplements across grade spans. Moreover, the Governor’s proposed approach may overestimate costs and provide excessive funding in some districts. For example, in many unified districts, applying the district average across all grades likely would overstate the actual proportion of EL/LI students in high school and understate the actual proportion in elementary school, since EL students tend to be more concentrated in the lower grades. Consequently, this likely would result in many unified districts receiving a larger supplement than actual student counts would generate, because a larger portion of their supplements would be calculated from the higher high school base grant rate.

Adds Unnecessary Complexity by Including Separate K–3 and High School Supplements. The Governor’s plan provides grade–span adjusted base funding rates to address differing costs across grades. Applying K–3 and high school supplements in addition to the unique base grants therefore adds complexity to what is an otherwise relatively straightforward formula. Additionally, because the Governor’s proposal does not provide any assurance that the additional funds would be used for their intended purposes, the programmatic rationale for maintaining the two supplements is not particularly compelling. In the case of K–3, given that districts and local bargaining units would be able to jointly determine any class size—even exceeding 24 students—and still receive the proposed K–3 funding supplement, offering this funding outside the K–3 base rate would not necessarily lead to smaller class sizes. In the case of high school, the supplement would not contain any spending requirements to ensure that the funds would be used to provide CTE services.

Maintains Historical Advantages for Basic Aid Districts. Despite an implied intention to remove the historical funding advantages currently benefiting basic aid districts, the “hold harmless” clause included in the Governor’s proposal would preserve a historical artifact in a new system that is intended to reflect updated data. Guaranteeing that all districts would forever receive the same amount of per–pupil state aid as they did in 2012–13 would continue to augment basic aid districts’ per–pupil funding at a level that exceeds that of other districts.

Does Not Adequately Protect Investments in Facilities. The Governor’s proposal would leave the decision of how much (or how little) to spend on maintaining their facilities up to districts. We are concerned that repealing spending requirements for maintenance would jeopardize the large local and state investments in school facilities made over the past decade. Data on how districts have responded to recent categorical flexibility provisions suggest that competing spending priorities at the local level can lead districts to underinvest in maintaining their facilities. Such practice could result in unsafe conditions, a push to pass new state bonds, and/or additional lawsuits against the state. (The 2001 Williams v. California class–action lawsuit was related to improper conditions at school facilities.)

We think the Governor offers a helpful framework for restructuring the funding system, and therefore recommend the Legislature adopt most components of his proposal. We believe, however, that the proposed approach would be improved by some notable modifications. Figure 8 summarizes our recommended changes to the Governor’s proposed LCFF, described in more detail below.

Figure 8

Recommended Modifications to Governor’s School District LCFF Proposal

|

|

- Include TIIG and HTS Transportation funding in new formula.

|

- Require that EL/LI supplemental funds be used to provide supplemental services for EL/LI students.

|

- Target concentration funding to districts with highest concentrations of EL/LI students.

|

- Calculate EL/LI student supplement based on actual grade–level data, not districtwide averages.

|

- Reject K–3 and high school supplements.

|

- Minimize historical advantages for basic aid districts.

|

- Maintain basic requirements for facility maintenance.

|

Include TIIG and HTS Transportation Funding in New Formula. To maintain consistent funding policies across districts, we recommend the Legislature include both the TIIG and HTS Transportation programs in the proposed categorical consolidation and new funding formula. This would treat these two categorical programs comparably to the vast majority of other existing categorical programs. Excluding these programs would permanently maintain significant funding differences across districts without a rational basis for doing so.

Require That EL/LI Supplemental Funds Be Used to Provide Supplemental Services for EL/LI Students. To help ensure that EL/LI students receive additional services—beyond those that all students receive—we recommend the Legislature place somewhat stronger restrictions on how districts may use the supplemental and concentration funds generated by EL/LI students. Specifically, we recommend adopting broad–based requirements—similar to those of EIA or the federal Title I and Title III programs—that require the supplemental funds be used for the target student groups to supplement and not supplant the basic educational services that all students receive. (Title I provisions allow schools with sufficiently high proportions of EL/LI students to use the funds to enhance services for all students. The Legislature could consider developing similar “schoolwide” provisions for the new state supplement.)

Target Concentration Funding to Districts With Highest Concentrations of EL/LI Students. To better align funding with the greatest need, we recommend the Legislature raise the threshold at which districts qualify for supplemental concentration funding. For example, the additional supplement could be limited for districts in which 70 percent of the student population is EL/LI, rather than 50 percent. We estimate that raising the eligibility threshold in this way would narrow the beneficiaries of the concentration supplement to one–quarter of all districts, as opposed to half of all districts under the Governor’s proposal. The Legislature could thereby target the supplemental funds for those districts facing the greatest challenges. Limiting the concentration supplement in this way would free up funds that could be used for other elements of the formula (such as increasing all districts’ funding levels to more quickly attain the target rates). Alternatively, the Legislature could consider providing tiered concentration funding rates, such that the districts with the highest concentrations of EL/LI students get the greatest amount of additional resources. For example, districts with 75 percent EL/LI students might get 20 percent more funding for their additional students, whereas districts with 90 percent EL/LI students might get 35 percent more funding.

Calculate EL/LI Student Supplement Based on Actual Grade–Level Data, Not Districtwide Averages. To improve the accuracy of the new funding formula, we recommend the EL/LI student supplement be calculated based on the actual rates of EL/LI students by grade. This approach—in contrast to the Governor’s proposal to apply districtwide average rates of EL/LI students across all grade spans—would fund districts in a way that more closely reflects actual student need and associated costs.

Reject K–3 and High School Supplements. To avoid adding unnecessary complexity, we recommend against including the proposed K–3 and high school funding supplements in the new funding formula. Should the Legislature wish to facilitate districts’ abilities to offer lower K–3 class sizes or high school CTE courses, we recommend it simply increase the applicable base rates above the levels proposed by the Governor. (This would have the effect of increasing funding for EL/LI students as well, since the 35 percent supplement would be calculated off of higher base rates.) As the Legislature considers whether to adjust the proposed base rates, we would note that the Governor’s proposed 9–12 base rate already is nearly 16 percent (or about $1,000) above the 7–8 rate. This amount may already be sufficient to provide a full high school program, including CTE services.

Minimize Historical Advantages for Basic Aid Districts. To prioritize limited state funds for those districts that do not benefit from excess LPT revenue, we recommend rejecting the Governor’s proposal to guarantee districts the same level of state aid they received in 2012–13. We do, however, recommend adopting the Governor’s proposal to count LPT revenue towards a district’s entire LCFF grant, including both the base and supplemental grants. Under our modified approach, basic aid districts whose LPT revenues exceed their calculated LCFF levels would not receive any state aid beyond the minimum constitutional obligation of $120 per pupil. This would end the current practice of providing basic aid districts with state categorical aid in addition to their excess LPT revenue—often resulting in notably higher per–pupil funding rates compared to other districts.

Maintain Basic Requirements for Facility Maintenance. To ensure that districts continue to protect state and local investments and maintain safe school facilities, we recommend the Legislature require districts to dedicate a portion of their General Fund expenditures—between 3 percent and 4 percent—to facility maintenance. This approach would establish requirements not included in the Governor’s approach, but would be more streamlined than previous practice (which included two distinct spending requirements, one for routine and one for deferred maintenance).

This section describes and assesses the changes the Governor proposes for COEs.

Below, we provide background on the four major functions of COEs. These functions encompass a range of activities and are funded by a variety of sources.

California’s 58 COEs Serve School Districts and Students. The State Constitution establishes the County Superintendent of Schools position in each of the state’s 58 counties. Most county superintendents are elected, but five are appointed locally. All county superintendents have established COEs to fulfill their duties. Initially, these duties consisted of broadly defined responsibilities, such as to “superintend the schools” of the county and to “enforce the course of study” at those schools. Over time, however, the state has tasked COEs with some more specific responsibilities and funded them to provide numerous regional services.

COEs Have Multiple Responsibilities. The COEs conduct a variety of activities, some of which serve school district staff and some of which serve students directly. In 2012–13, COEs received roughly $1 billion in state funds and LPT revenue to support these activities. Figure 9 provides an overview of current COE responsibilities and their associated funding. These activities generally fall into four major areas: (1) regional services, (2) alternative education, (3) additional student instruction and support, and (4) academic intervention. Given the notable diversity of district and student characteristics across counties, the extent of these activities varies widely by COE. Below, we describe each of these responsibilities in greater detail.

Figure 9

County Offices of Education (COEs) Have Several Responsibilities

Approximate Funding Levels in 2012–13

|

|

|

Regional Services ($380 Million)

|

- Administrative Services for School Districts ($300 Million). Administrative and business services provided to school districts within the county.

|

- Additional Services for Small Districts ($10 Million). Additional administrative services for small school districts within the county.

|

- Programmatic Services for Districts ($60 Million). Certain types of support provided for school districts within the county, such as professional development, services for beginning teachers, and technology support.

|

- District Oversight ($10 Million). Oversight of district budgets and monitoring district compliance with two education lawsuits.

|

|

Alternative Education ($300 Million)

|

- Juvenile Court Schools ($100 Million). Instruction and support for incarcerated youth.

|

- County Community and County Community Day Schools ($160 Million). Instruction and support for students who cannot or opt not to attend district–run schools, including those who have been expelled or referred by a probation officer or truancy board.

|

- Categorical Funding for Alternative Education ($40 Million). Additional funding for services in COE alternative settings. Examples of specific funding grants include the Instructional Materials Block Grant, Economic Impact Aid, and the Arts and Music Block Grant.

|

|

Additional Student Instruction and Support (Funding Varies)

|

- Regional Occupational Centers and Programs ($150 Million). Career technical education and training for high school students.

|

- Other Student Services (Funding Varies). Includes instruction and services for specific student populations, including foster youth, pregnant and parenting students, adults in correctional facilities, migrant students, and young children needing child care and preschool.

|

|

Academic Intervention (Funding Varies)

|

- Support and Intervention (Funding Varies). Various services for schools and districts identified as needing intervention under the state or federal accountability systems. Specific initiatives include the State System of School Support, District Assistance and Intervention Teams, and Title III assistance.

|

All COEs Provide Some Administrative Services for School Districts. The COEs provide a variety of administrative and business services for districts in their counties. Some of these activities are required by state law, such as verifying the qualifications of teachers hired by school districts. Additionally, many COEs have opted to provide other administrative services based on local circumstances and district needs. For example, most COEs operate countywide payroll systems and provide human resources support for their districts. Generally, these activities are funded by a base revenue limit grant of general purpose funds, although some districts also purchase some services from COEs on a fee–for–service basis. The base grant provides each COE with a per–pupil funding rate based on countywide ADA. These per–pupil rates range from $24 to $465 per ADA and are determined primarily by historical factors. The base grant also supports general COE operational costs.

Many Small Districts Require Additional Services. The COEs tend to provide greater levels of administrative support for smaller school districts. Smaller districts often lack economies of scale and tend to rely on their COEs to provide such services as school nurses, guidance counselors, and librarians, instead of hiring these personnel on their own. In addition to the base grant, COEs located in counties containing smaller school districts receive supplemental general purpose funding. For the purposes of this funding, a small school district is defined as one serving 1,500 or fewer ADA. (Lower ADA thresholds apply for elementary and high school districts.) The COEs receive between $52 and $143 per ADA in these districts, with the specific rates differing across counties. Like the base revenue limit grants, these per–pupil funding rates are determined largely by historical factors.

Most COEs Provide Programmatic Services for Their Districts. The COEs also perform a variety of other tasks to meet the needs of school districts within their counties. Examples include providing professional development, support for beginning teachers, technology services, and technical assistance for various district–run categorical programs. Many of these activities are funded through state categorical grants, the largest of which are the Beginning Teacher Support and Assessment (BTSA) program and the California Technology Assistance Program (CTAP). The amount of funding each COE receives to provide programmatic support varies based on historical participation in individual programs. Additionally, districts sometimes purchase these types of services from COEs. For example, some COEs charge fees when a district’s teachers attend professional development sessions.

All COEs Tasked With Overseeing Some District Activities. The state has established three specific district oversight roles for all COEs—funded through three discrete categorical grants—relating to monitoring districts’ fiscal status and compliance with two lawsuits. Legislation adopted in 1991 requires all COEs to review and approve the annual budgets of school districts within their county. The legislation further requires COEs to monitor districts during the year and intervene if their financial situations begin to deteriorate. (These responsibilities sometimes are referred to as “AB 1200” requirements after the establishing legislation.) Additionally, the state requires COEs to monitor school districts’ activities associated with two lawsuits (Williams v. California and Valenzuela v. O’Connell). The Williams requirements relate to maintaining adequate school facilities, sufficient instructional materials, and qualified teachers. The Valenzuela requirements relate to providing supplemental services for high school seniors who fail to pass the high school exit examination.

The COEs Run Alternative Schools for Certain Students. Besides providing support services for districts, one of the primary functions of COEs is to provide classroom instruction for students who cannot (or, in some limited cases, opt not) to attend their local district–run schools. These students need alternative settings for a variety of reasons, including chronic truancy, expulsion, or incarceration. Most individual districts are not equipped to provide such services for the few students in the district who require them.

Three Types of COE Alternative Schools. The COEs operate three types of alternative schools—juvenile court schools, county community schools, and community day schools (CDS)—for students needing alternative education settings. In these schools, the COE employs the teachers, oversees the students’ instructional program, and runs the facility. The basic funding model for these programs is similar to school districts—the state provides the COEs with a per–pupil revenue limit and various categorical grants for the students attending their schools. The revenue limit rate for most students in COE alternative education programs is roughly 40 percent higher than the average revenue limit rate in a high school district. (Most, but not all, students in alternative settings are in high school.) This higher rate is intended to support smaller class sizes, individualized student support, and more rigorous security precautions. Below, we describe some of the basic components of each type of COE alternative school. Generally, the schools represent a continuum—with court schools serving the students with the most severe challenges in the most secure settings, and CDS serving students with relatively fewer challenges in less restrictive school settings.

- Juvenile Court Schools. These programs serve students under the authority of the juvenile justice system. All students generate a higher revenue limit rate, which averaged $8,550 per ADA in 2012–13. These schools must offer at least four hours of daily instruction.

- County Community Schools. These programs serve several types of students. Students who have been mandatorily expelled, referred by a probation officer, or are on probation generate funding at the same rate as court school students ($8,550 per ADA). In contrast, students who are expelled for non–mandatory reasons, referred by a truancy board, or voluntarily placed in a community school generate the revenue limit rate of their home school district (on average, $6,000 per ADA in a high school district). These schools must offer at least four hours of daily instruction.

- COE CDS. These programs serve students who have been expelled for any reason, referred by a probation officer, or referred by a truancy board. Students at these schools generate $12,750 per ADA—consisting of the base court school rate ($8,550 per ADA) plus $4,200 per ADA for providing a longer school day (six hours). Some school districts also operate CDS for similar students, but district CDS are funded at the district’s revenue limit rate plus additional funding for the fifth and sixth hour. (Since 2009, most CDS funding allocations for the fifth and sixth hour have been “frozen” and subject to categorical flexibility provisions.)

Alternative schools are the largest COE instructional programs, and students attending those programs are the only students for whom COEs maintain full responsibility for educating. Yet many COEs also operate specialized programs that provide instructional services to other types of students. All of these activities are funded through discrete state or federal categorical grants.

Many COEs Provide ROCP Services for Students Attending Local Districts. The ROCPs are among the most substantial of COE–run instructional activities. The ROCPs provide CTE services to students ages 16 and older. Coursework typically takes place both in traditional classroom settings as well as at employer job sites. About half of total state funding for ROCPs is allocated to 38 COEs to provide services mostly for students who attend district–run high schools in the region. (The remaining ROCP funds are provided to individual school districts and consortia of districts.) The ROCP grant is among the programs affected by recent categorical flexibility provisions. Since 2009, COEs receiving ROCP grants have been allowed to use the funds for any purpose.

Other Student Services. Many COEs provide direct instruction or support services for special groups of students. For example, the state funds many COEs to provide educational support for foster youth, pregnant and parenting students, and adults in correctional facilities. A federal grant funds many COEs to provide educational support for migrant students, and child care services are funded through a combination of state and federal sources.

The COEs Support Struggling Schools and Districts. In recent years, the state has tasked COEs with providing specialized support and intervention for schools and districts that have been flagged as low performers in the state and federal accountability systems. Generally, these initiatives require COEs to provide intensive professional development, data analysis, curriculum review, monitoring, and other technical assistance to schools and/or districts. Specific initiatives have included the State System of School Support, District Assistance and Intervention Teams, and Title III accountability intervention. Most of the funding to support these activities has been provided through federal grants.

The Governor proposes to change the state’s approach to funding many COE responsibilities. Specifically, he would collapse many existing funding streams into a simplified, two–part formula.

Replaces Much of Existing System With Two–Part Funding Formula. The Governor proposes replacing the existing COE funding model with a new two–part funding formula. As shown in Figure 10, the formula includes funding to (1) provide regional services to districts and (2) educate students in COE–run alternative schools. While the amounts associated with these two responsibilities would be calculated through two separate formulas, the funds would be combined into one allocation that COEs could use for either purpose. Consistent with his overall approach for districts, the Governor would establish funding targets for each COE and build toward those targets over a number of years. Each COE’s funding target would be the sum of its calculated allotments under the regional services formula and the alternative education formula. The Governor’s 2013–14 budget proposal includes a $28 million augmentation to begin this process for COEs.

Figure 10

Overview of Governor’s Local Control Funding Formula for COEs

|

Formula Component

|

Proposal

|

|

Regional Services

|

|

|

Target amount per COE

|

- $655,920 for base grant.

- Additional $109,320 per school district in the county.

- Additional $40 to $70 per ADA in the county (less populous counties would receive higher per–ADA rates).

|

|

Required oversight activities

|

- Reviewing school district budgets and accountability plans.

- Monitoring district activities related to Williams v. California lawsuit.

|

|

Alternative Education

|

|

|

Eligible student population

|

- Students who are (1) incarcerated, (2) on probation, (3) probation–referred, or (4) mandatorily expelled.

|

|

Target amount for base grant (per ADA)

|

|

|

Supplemental funding for EL, LI, and foster youth

|

- Additional 35 percent of COE base grant.

- Juvenile court schools: assumes 100 percent of students fall into these groups (provides additional 35 percent grant for all students).

|

|

Supplemental concentration funding

|

- Additional 35 percent of COE base grant for EL/LI students above 50 percent of enrollment.

- Juvenile court schools: assumes 100 percent of students are EL/LI (provides additional 35 percent grant for half of all students).

|

|

Annual Plan and Transition

|

- Annual local accountability plan would be submitted to State Superintendent of Public Instruction.

- Transitions to target amounts within a few years.

|