Beginning January 1, 2014, the ACA gives state Medicaid programs the option to expand health coverage to most adults under age 65—including childless adults—with incomes at or below 133 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) who are not currently eligible. In California, counties generally have the fiscal and programmatic responsibility for providing health care to this population. The federal matching rate for coverage of this expansion population will be 100 percent for the first three years, but will decline between 2017 and 2020, with the state or counties eventually bearing 10 percent of the additional cost of health care services for the expansion population.

The Governor has proposed to adopt the optional expansion. He has also outlined two distinct approaches to implementing the expansion—a state–based approach and a county–based approach—but has not indicated a preference for either approach. Under both approaches, the Governor indicates that the expansion will require a reassessment of the state–local fiscal relationship.

In this report, we provide the Legislature with recommendations on three major issues related to the optional Medicaid expansion.

- Should the state adopt the optional Medicaid expansion?

- Should the state adopt the state–based or county–based approach?

- What changes to the state–county fiscal relationship would be appropriate under the expansion and how should they be implemented?

The existing allocation of federal, state, and local responsibilities and funding for health programs is complex. Below, we discuss: (1) the major programs administered by state and local governments that provide health services to low–income populations in California, (2) provisions of the ACA that have significant effects on these state and local programs, and (3) recent actions the state and counties have taken toward implementing the ACA.

Medi–Cal Is California’s Primary Health Coverage Program for Low–Income Individuals. Medicaid is a joint federal–state program that provides health coverage to certain low–income populations. The program is voluntary for states. In California, the Medicaid program is administered by the state Department of Health Care Services (DHCS), and is known as Medi–Cal. Currently, Medi–Cal provides health care services to over eight million qualified low–income persons—including families with children, pregnant women, seniors, and persons with disabilities. The income threshold used to determine eligibility varies. For some groups, such as parents, the income threshold is about 100 percent FPL. (In 2012, the FPL is $11,170 per year for an individual and $23,050 for a family of four.) For other groups, the income threshold is significantly higher—reaching up to 200 percent FPL for pregnant women and 250 percent FPL for children (when the transition of the state’s Healthy Families Program (HFP) into Medi–Cal is complete in 2013). Generally, a low–income childless adult who is not elderly or disabled does not qualify for Medi–Cal under current eligibility standards. As discussed in more detail below, the ACA gives California the option to significantly expand eligibility for the Medi–Cal Program beginning January 1, 2014, mainly to low–income childless adults, as well as some parents.

Medi–Cal Costs Split Between the State and Federal Government. The federal government pays for a share of the cost of each state’s Medicaid program. The percentage of program costs funded with federal funds is known as the federal medical assistance percentage (or “federal match”). The Medi–Cal Program currently—and historically—receives a 50 percent federal match for most services, meaning that the program generally receives one dollar of federal funds for each state dollar it spends on those services. The federal government also provides an enhanced federal match for certain program costs, such as certain types of health services and the implementation of information technology systems.

The federal government only pays for emergency and pregnancy–related services for certain populations that meet all current eligibility standards with the exception of certain immigration status requirements—including undocumented individuals and qualified aliens who have been in the country for less than five years (newly qualified aliens). In California, newly qualified aliens are eligible to receive full Medi–Cal benefits and the costs of the additional benefits are funded entirely with state General Fund monies. Medi–Cal does not pay for nonemergency and nonpregnancy–related services for undocumented individuals.

The Medi–Cal Delivery System. There are two main Medi–Cal systems for the delivery of health care: fee–for–service (FFS) and managed care. In the FFS system, a health care provider receives an individual payment for each service provided to a Medi–Cal enrollee. The FFS enrollees generally may obtain services from any provider who has agreed to accept Medi–Cal payments. In Medi–Cal managed care, DHCS contracts with certain managed care plans, also known as health maintenance organizations or “plans,” to provide health care coverage for Medi–Cal beneficiaries residing in certain counties. Plan enrollees may obtain services from providers who accept payments from the plan, also known as a plan’s “provider network.” Medi–Cal reimburses the plans on a “capitated” basis with a predetermined amount per person, per month and the plans reimburse providers for health care services delivered to enrollees.

Counties provide a wide variety of health services in California, including physical health care for medically indigent adults—or low–income individuals who cannot afford health insurance coverage and who are not eligible for Medi–Cal. Throughout this report, we focus on the counties’ role in providing physical health care services to the medically indigent—also known as indigent health care. Counties are also the primary providers of public health services and behavioral health services for low–income individuals in California. For more information on counties’ role in the provision of public health and behavioral health services, please see the nearby box.

Counties provide and finance a wide variety of health services in addition to physical health care for the medically indigent, including mental health services, substance use treatment, and public health services.

Mental Health Services. Counties are the primary providers of mental health services to the medically indigent (to the extent resources are available). Counties also provide mental health services to Medi–Cal enrollees, primarily for serious mental disorders that require treatment by licensed mental health care specialists such as psychiatrists. Services include medication support, case management, prevention programs, and crisis intervention. Counties are responsible for paying the nonfederal share of these specialty mental health treatments provided to Medi–Cal enrollees. The nonfederal share of funding for mental health services comes from various sources, including 1991 Realignment, Proposition 63 (Mental Health Services Act), 2011 Realignment, and county General Fund revenues.

Substance Use Treatment. Counties are the primary providers of substance abuse treatment services to the medically indigent (to the extent resources are available). Counties also provide substance abuse treatment services to Medi–Cal enrollees. The Drug Medi–Cal program offers services that include: outpatient drug free clinics and the Narcotic Treatment Program. Counties are responsible for paying the nonfederal share of drug and alcohol treatment provided to Medi–Cal enrollees. The nonfederal share of funding for substance use treatment services comes from various sources, including 1991 Realignment, 2011 Realignment, and county General Fund revenues.

Public Health Services. Many public health programs and services are delivered at the local level by county public health departments. These programs address public health issues, such as communicable disease control, environmental health, smoking cessation programs, childhood exposure to lead, and family planning services.

For most of the state’s history, counties have provided safety–net health care services to low–income individuals who do not have health insurance coverage—commonly referred to as the medically indigent. Counties’ indigent health responsibilities were statutorily established in the 1930s, with the enactment of Welfare and Institutions Code (WIC) Section 17000, which generally requires counties to provide health care to medically indigent individuals. With the establishment of the Medi–Cal Program in 1966, some county responsibilities for providing health care for low–income Californians shifted to the federal government and state. However, counties remained responsible for providing health care to medically indigent individuals who are not eligible for Medi–Cal or other state health programs—a population that consists primarily of childless, non–elderly adults. Many counties also provide indigent health services to undocumented individuals, although this is not specifically required by WIC Section 17000.

Over the years, the roles of the state and counties in providing health care to the medically indigent have been redefined several times. Below, we discuss the major historical developments that shaped the relationship between the state and counties in the delivery of indigent health care.

Medi–Cal Eligibility Expanded to Certain Medically Indigent Adults (MIAs). In 1971, the state enacted a package of reforms to the Medi–Cal Program. As part of this package, the state extended Medi–Cal eligibility to childless adults as a state–only program—shifting the responsibility of providing health care to this population from counties to the state. In conjunction, counties were required to assume a share of cost for the Medi–Cal Program. Following this shift of childless adults to Medi–Cal, county obligations under WIC Section 17000 decreased substantially. However, counties continued to incur costs for services provided to undocumented individuals and others unable to qualify for Medi–Cal.

Two Constitutional Amendments Substantially Altered State–County Relationship. In the late 1970s, voters approved two amendments to the State Constitution which substantially altered the state–local relationship: Proposition 13 (1978) and Proposition 4 (1979). Proposition 13 immediately reduced local government property tax revenues by more than 60 percent. Proposition 4 generally requires the state to reimburse local governments if the state mandates that local governments provide a new program or a higher level of service.

State Provided Aid to Counties Following Proposition 13. In response to the significant decline in local government revenues resulting from Proposition 13, the state took a variety of actions to provide fiscal relief to local governments. In 1979, the Legislature enacted Chapter 282, Statutes of 1979 (AB 8, L. Greene), which, among other things, provided fiscal relief to counties by: (1) eliminating the county share of cost for Medi–Cal and (2) establishing annual subventions to counties to support county public health programs and indigent health care. As a condition of receiving state aid for health programs under AB 8, counties were required to spend a specified amount of county purpose general revenues on county public health and indigent health programs.

MIAs Removed From Medi–Cal. In 1982, facing rising costs in the Medi–Cal Program and a significant budget deficit, the Legislature eliminated Medi–Cal eligibility for childless adults. Under WIC 17000, health care responsibilities for childless adults once again fell to the counties. To support county costs of providing health care to individuals no longer eligible for Medi–Cal, the Legislature established two new programs: (1) Medically Indigent Services Program (MISP), which provided state funding to support indigent health costs in larger counties, and (2) County Medical Services Program (CMSP), which allowed smaller counties to contract with the state to provide indigent health care. Both MISP and CMSP were funded with annual appropriations from the General Fund. In order to receive state funds under MISP or CMSP, counties were required to continue meeting the provisions in AB 8 related to the expenditure of county general purpose revenue on public health and indigent health programs.

State Enacted a Major Change to State–County Relationship. In 1991, the state enacted a major change in the state and local government relationship, known as realignment. The 1991 realignment package: (1) transferred several programs from the state to the counties, including health and mental health programs; (2) changed the way state and county costs are shared for social services and health programs; and (3) increased the sales tax and vehicle license fee (VLF) and dedicated these increased revenues for the increased financial obligations of counties. Under realignment, the original revenue allocations to counties were based on the amount of funding each county received for the realigned programs from the state just prior to realignment. Annual growth in realignment revenues is allocated based on a separate set of formulas, primarily intended to prioritize funding for costs due to increased caseload and to equalize funding levels across counties.

1991 Realignment Modified Indigent Health Funding. The 1991 realignment package dedicated a portion of the increased sales tax and VLF revenues to fund AB 8 health payments, MISP, and CMSP—eliminating state General Fund support for these programs. Consistent with county expenditure requirements under AB 8, the 1991 realignment package required counties to maintain a minimum level of expenditure—a maintenance–of–effort (MOE)—on public health and indigent health programs.

Currently, the manner in which each county finances and delivers health care to the medically indigent varies across the state. Counties have flexibility with respect to the services provided, the populations served, the method of delivering services, and the funding used to provide services. Figure 1 describes three broad categories of county–based programs that have provided coverage to MIAs in recent years. This section focuses on the characteristics of county medically indigent programs. We discuss the federally funded waiver programs later in this report.

Figure 1

County–Based Indigent Health Programs

|

Program

|

Description

|

|

Medically Indigent Programs

|

Longstanding County Programs That Pay for Health Services for Some Medically Indigent Adults. Characteristics of each county’s medically indigent program vary substantially, including the maximum income level and residency requirements necessary for eligibility.

|

|

Coverage Initiatives

|

Federally Funded Programs Authorized in Ten Counties Under a 2005 Medicaid Waiver. Beginning in 2007, counties were eligible for 50 percent federal funding for care provided to medically indigent adults enrolled in the Coverage Initiative. In return, counties were required to meet certain federal requirements related to improved system integration, quality, and coordination of care. In 2011, these programs were replaced by the Low Income Health Programs (LIHPs) authorized under the new Bridge to Reform waiver.

|

|

LIHPs

|

The Bridge to Reform Waiver Built Upon the Existing Coverage Initiatives in the Ten Counties by Authorizing Optional County–Based LIHPs in Every County, Beginning in July 2011. Most, but not all, counties currently operate a LIHP. Many counties that operate a LIHP have a separate medically indigent program for adults who are not eligible for the LIHP.

|

Counties Vary in How They Deliver Services to Medically Indigent Individuals. The manner in which counties deliver health services to the medically indigent varies from county to county. Counties are often characterized by the degree to which they directly provide health care services to the medically indigent population. For example, counties generally fall into one of the following categories:

- Provider Counties—MISP counties that own and operate inpatient hospitals and clinics that provide care to essentially all individuals, whether or not they have health coverage. Currently, there are 12 provider counties, including some of the most populous counties in California, such as Los Angeles County.

- Payer Counties—MISP counties that pay for medically indigent care services through contracts with private or University of California (UC) hospitals, community clinics, and/or private physicians. These counties generally do not own or operate facilities that provide physical health care services.

- Hybrid Counties—The MISP counties that do not operate a hospital, but that operate outpatient clinics that provide care to low–income populations. These counties also have contracts with hospitals and, in some cases, other community clinics and/or private physicians.

- CMSP Counties. As discussed above, a group of 35 rural and/or small counties that pays for medical care to MIAs in participating counties. The CMSP currently contracts with a third–party administrator (Anthem Blue Cross) to organize the delivery of health care services to certain medically indigent populations in these counties.

Figure 2 illustrates the degree to which each county directly provides care to its MIA population.

Historically, medically indigent programs have provided episodic care, with little emphasis on primary care services, preventative care, and care coordination. For example, some payer counties simply reimburse providers for services provided to individuals who show up at the hospital with an immediate need for care. In provider counties, many of the medically indigent program enrollees are indigent individuals who show up at the hospital emergency room with an illness or injury in need of treatment. In recent years, some counties have begun to place a greater emphasis on actively enrolling medically indigent individuals in the program as a way to emphasize preventative and primary care services.

Significant Differences in Eligibility for Medically Indigent Programs. Generally, potential enrollees are screened for Medi–Cal eligibility before they are determined eligible for medically indigent programs. Eligibility differs among counties in several ways, including the maximum income threshold and immigration status requirements. For example, some counties do not cover services for undocumented individuals, other counties cover limited services for undocumented individuals (such as emergency services), while other counties provide full services to undocumented individuals. Most medically indigent programs provided coverage to citizens and legal residents with incomes up to 200 percent FPL. However, several counties had income thresholds either above or below 200 percent FPL. In one county, the maximum income threshold was 63 percent FPL.

Counties Use Various Sources of Funding to Pay for Care for the Medically Indigent. In addition to 1991 health realignment funding described above, counties use a variety of funding sources to pay for medically indigent costs. Some of the most common sources of nonfederal funds are described in Figure 3. In many instances, counties have flexibility to use these funds on different types of services and populations. For example, a county may use a mix of 1991 health realignment funds, county general funds, and mental health realignment funds to provide services to MIAs.

Figure 3

Examples of Nonfederal Funding Sources Used to Pay for Care for the Medically Indigent

- 1991 Health Realignment Funds. Vehicle license fee (VLF) and state sales tax revenues that are allocated to the health account of each county.

|

- 1991/2011 Mental Health Realignment. The VLF and state sales tax revenues that are allocated to the mental health account of each county.

|

- Tobacco Master Settlement Funds. A portion of funds paid by tobacco companies under the Master Settlement Agreement between the states and certain tobacco companies is allocated to counties.

|

- County General Funds. The public funds of the county primarily from tax revenues.

|

In addition, provider counties receive a wide variety of supplemental payments from the federal government, including Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) payments and other payments associated with California’s Medicaid Section 1115 Waiver (discussed in more detail below). These funds are meant to at least partially offset uncompensated care costs, such as costs associated with providing care to the uninsured and care for which the county does not receive enough payment to fully cover its costs.

County–operated hospitals and clinics are a major part of the health care safety net. The health care safety net may be broadly defined as the health care providers—both public and private—that, as part of their core mission, provide services to all patients regardless of ability to pay or legal status. There are many different types of safety–net providers, including county–hospitals, private safety–net hospitals (such as Children’s Hospitals), county clinics, and rural health clinics. Generally, these providers serve a high percentage of individuals enrolled in Medi–Cal, county–based indigent health programs, and the uninsured. The financing structure for these providers is complex and they depend on a wide variety of funding sources. For example, under the terms of the Section 1115 waiver, counties are financially responsible for the nonfederal share of Medi–Cal inpatient services delivered to certain Medi–Cal enrollees. However, the waiver also provides a significant amount of federal funding that is intended to help ease the burden of uncompensated care costs for these hospitals.

The ACA, also referred to as federal health care reform, is far–reaching legislation that makes significant changes to health care coverage and delivery in California. The ACA is, in part, designed to create a health coverage purchasing continuum that makes it easier for persons to access, purchase, and maintain health care coverage. As individuals’ incomes rise and fall; as they become employed, change employers, or become unemployed; and as they age, they are to have access to different sources of coverage along the coverage continuum. Creating this continuum requires the modification of existing government programs and integration of these programs with new coverage options created by ACA. For more information on the various provisions in the ACA that potentially affect California state health programs, please see our May 2010 report,

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: An Overview of Its Potential Impact on State Health Programs. Below, we discuss some of the major ACA provisions that have fiscal implications for state and local governments. We note that there are numerous other provisions of the ACA that will affect state and county finances—both directly and indirectly—that we have not described here.

Creates Penalties for Certain Individuals Without Health Insurance Coverage. Beginning January 1, 2014, the ACA requires most U.S. citizens and legal residents to have health insurance coverage or pay a penalty. This requirement is commonly known as the individual mandate. Certain individuals are exempt from the individual mandate, including those exempt from filing federal taxes due to their low–income status. A significant portion of the Medicaid population has income below the federal tax filing threshold and would be exempt from the individual mandate. The ACA also gives the federal Secretary of Health and Human Services (Secretary) some flexibility to establish other financial hardship exemptions. In light of the recent Supreme Court ruling, as discussed below, the Secretary indicates that she would use this authority to exempt additional low–income individuals in those states that chose not to implement the optional Medicaid expansion.

Establishes Health Benefit Exchanges With Federal Subsidies to Purchase Coverage. The ACA establishes entities called Health Benefit Exchanges. Through these exchanges, individuals and small businesses will be able to research, compare, check their eligibility for, and purchase health coverage. In California, citizens and legal residents with family income between 100 percent and 400 percent FPL who do not qualify for Medi–Cal will be eligible for federal subsidies to purchase health coverage through the California Health Benefit Exchange (also known as the Exchange or Covered California) that is currently under development.

Authorizes Medicaid Expansion up to 133 Percent FPL. The ACA gives states the option to significantly expand their Medicaid programs, with the federal government paying for a large majority of the additional costs. Beginning January 1, 2014, federal law allows state Medicaid programs to expand coverage to most adults under age 65—including childless adults—with incomes at or below 133 percent of the FPL who are not currently eligible. (After taking into account a technical adjustment to eligibility required under the federal law, the income limit is, in effect, 138 percent of the FPL.) Generally, this population includes nonpregnant, nondisabled childless adults. In addition, some parents with incomes between 100 percent and 133 percent FPL would become eligible. Similar to other Medi–Cal eligibility categories, undocumented immigrants would only be eligible for limited services, such as emergency services. As shown in Figure 4, the federal matching rate for coverage of this expansion population will be 100 percent for the first three years, but will decline between 2017 and 2020, with the state eventually bearing 10 percent of the additional cost of health care services for the expansion population.

Figure 4

Federal Matching Rate for Health Care Services Provided to Medicaid Expansion Population

|

Calendar Year

|

Federal Match

|

|

2014

|

100%

|

|

2015

|

100

|

|

2016

|

100

|

|

2017

|

95

|

|

2018

|

94

|

|

2019

|

93

|

|

2020 and thereafter

|

90

|

Recent Supreme Court Ruling Makes Medicaid Expansion Optional for States. Originally, the ACA included a provision that would allow the federal government to withhold a state’s Medicaid funding if the state did not adopt the expansion—effectively making the Medicaid expansion mandatory. A recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling found the mandatory Medicaid expansion unconstitutional and struck down this provision of the ACA—effectively making the Medicaid expansion optional for states. Subsequent federal guidance confirmed that the Medicaid expansion is now truly voluntary—meaning states may choose to adopt or eliminate the coverage expansion at any time. Recent guidance from the federal government also indicates that states may not partially adopt the Medicaid expansion. In other words, states may either adopt the expansion up to 133 percent FPL or not adopt the expansion at all. For example, states may not adopt the expansion only for adults up to 100 percent FPL.

Changes Methodology Used to Determine Financial Eligibility. Beginning January 1, 2014, the ACA makes changes to the methodology used to calculate income when determining Medicaid program eligibility for most beneficiaries—excluding certain populations, such as seniors and persons with disabilities. Currently, the methodology used to determine financial eligibility for Medicaid is complex—often involving verification of an applicant’s assets and accounting for a variety of income deductions and exemptions. The ACA generally simplifies the standards used to determine financial eligibility. The two major changes to the methodology are:

- Requiring the use of a new methodology to calculate income, known as Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI). As part of this change, various deductions to applicant income that are now permissible would end.

- Asset tests will no longer be used to determine eligibility.

Changes to Outreach and Enrollment Processes. In addition to the eligibility changes identified above, the ACA also includes provisions aimed at streamlining the enrollment processes and coordinating with other entities that will offer subsidized health insurance coverage to low– and moderate–income persons. For example, persons may be determined eligible for Medi–Cal after applying through a website operated by the Exchange. The state is required to use available electronic data sources, such as tax information from the Internal Revenue Service, to determine eligibility prior to asking for additional information from the applicant. The Exchange will also be conducting outreach activities aimed at enrolling uninsured individuals in health coverage, including Medi–Cal.

The ACA requires over several years an $18.1 billion total reduction in federal funding nationwide for DSH allocations, which now go to hospitals that serve a disproportionate share of Medicaid beneficiaries and the uninsured. The fiscal impact of this change will be felt mainly by counties that operate DSH–supported hospitals.

The state and counties have, in effect, already taken significant steps toward implementing the optional expansion under ACA. Much of that progress was facilitated by the state’s Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstration Waivers that provided federal funding for, among other things, county–based indgent health programs. (These allow states to waive federal Medicaid requirements in order to have the flexibility to modify their Medicaid programs in ways that are favorable to beneficiaries.) In 2005, the federal government approved the first of two 1115 waivers in California—hereafter referred to as “the previous waiver.” In November 2010, several months after passage of ACA, the federal government approved the next waiver—called California’s “Bridge to Reform” waiver—hereafter referred to as “the waiver.” Below, we discuss some of the significant components of the waivers and how they relate to funding and care for the medically indigent.

Previous Waiver Authorized Coverage Initiatives in Ten Counties. Among other things, the previous waiver authorized county–operated Coverage Initiatives in ten counties to provide medical care to low–income adults. In 2007–08, the following counties began operating Coverage Initiatives: Alameda, Contra Costa, Kern, Los Angeles, Orange, San Diego, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, and Ventura. Counties operating Coverage Initiatives received 50 percent federal funding for care provided to enrollees. In return, counties were required to meet certain federal requirements related to improved system integration, quality, and coordination of care. The general goal of the Coverage Initiatives was to assign individuals to a “medical home” in an effort to shift care away from more expensive episodic care to a more coordinated system of care to improve access, quality of care, and efficiency.

Bridge to Reform Waiver Authorized Low Income Health Programs (LIHPs). The Bridge to Reform waiver built upon and expanded the existing Coverage Initiatives in the ten counties by authorizing optional county–based LIHPs in every county. County LIHPs are split into two different types of coverage groups.

- Medicaid Coverage Expansion (MCE). Counties may offer coverage to low–income adults up to 133 percent FPL who would become eligible under ACA for Medi–Cal in 2014. Counties have the option to establish their MCE income eligibility thresholds below 133 percent FPL.

- Health Care Coverage Initiative (HCCI). If a county provides coverage to the MCE population up to 133 percent FPL, it has the option to operate a HCCI that offers coverage to adults with incomes between 133 percent and 200 percent FPL.

Currently, most counties are operating—or plan to operate—LIHPs that provide coverage to low–income populations, many of whom would qualify for Medi–Cal under the expansion. As shown in Figure 5, the characteristics of each LIHP—such as income threshold—vary from county to county. In addition, counties began implementing LIHPs at different times over the course of the last couple of years and currently several counties have not implemented a LIHP.

Figure 5

County Low Income Health Program (LIHP) Characteristics Vary

|

|

Upper–Income Limit (Percent of FPL)

|

Implementation Date

|

Monthly Enrollmenta (As of October 2012)

|

|

MCE

|

HCCIb

|

Total

|

|

Alamedac

|

200%

|

7/1/2011

|

37,900

|

8,600

|

46,500

|

|

Contra Costac

|

200

|

1/2/2012

|

9,800

|

2,000

|

11,800

|

|

CMSP

|

100

|

7/1/2011

|

56,600

|

—

|

56,600

|

|

Kernc

|

100

|

7/1/2011

|

6,000

|

—

|

6,000

|

|

Los Angelesc

|

133

|

7/1/2011

|

205,300

|

—

|

205,300

|

|

Monterey

|

100

|

N/A

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Orangec

|

200

|

7/1/2011

|

33,900

|

9,800

|

43,700

|

|

Placer

|

100

|

8/1/2012

|

1,900

|

—

|

1,900

|

|

Riverside

|

133

|

1/1/2012

|

23,900

|

—

|

23,900

|

|

Sacramento

|

67

|

11/1/2012

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

San Bernardino

|

100

|

1/1/2012

|

24,700

|

—

|

24,700

|

|

San Diegoc

|

133

|

7/1/2011

|

32,800

|

—

|

32,800

|

|

San Franciscoc

|

25

|

7/1/2011

|

9,400

|

—

|

9,400

|

|

San Joaquin

|

80

|

6/1/2012

|

1,500

|

—

|

1,500

|

|

San Mateoc

|

133

|

7/1/2011

|

8,500

|

—

|

8,500

|

|

Santa Clarac

|

75

|

7/1/2011

|

12,200

|

—

|

12,200

|

|

Santa Cruz

|

100

|

1/1/2012

|

2,200

|

—

|

2,200

|

|

Tulare

|

75

|

N/A

|

—

|

—

|

—

|

|

Venturac

|

200

|

7/1/2011

|

8,400

|

2,900

|

11,300

|

|

Totals

|

|

|

475,000

|

23,300

|

498,300

|

Counties that operate a LIHP receive 50 percent federal matching funds for services provided to LIHP enrollees. (Counties pay for the nonfederal share.) In return, a county must comply with certain federal requirements, such as minimum covered benefits and provider network adequacy. As discussed in more detail below, the LIHPs share some similar characteristics with Medi–Cal, but there are also significant differences. Many counties that operate a LIHP also operate a separate medically indigent program for adults who are not eligible for the LIHP, including undocumented immigrants and uninsured individuals with incomes too high to qualify for the LIHP.

Counties that operate a LIHP receive 50 percent federal matching funds for services provided to LIHP enrollees. (Counties pay for the nonfederal share.) In return, a county must comply with certain federal requirements, such as minimum covered benefits and provider network adequacy. As discussed in more detail below, the LIHPs share some similar characteristics with Medi–Cal, but there are also significant differences. Many counties that operate a LIHP also operate a separate medically indigent program for adults who are not eligible for the LIHP, including undocumented immigrants and uninsured individuals with incomes too high to qualify for the LIHP.

Waiver Provides Additional Federal Funding for State Programs and Public Hospitals. In addition to the LIHPs, the waiver made over $7 billion in federal Medicaid matching funds available over a five–year period to offset state costs for certain state health programs and provide funding to public hospitals intended to help preserve and improve the county–based health care safety net. For example, as much as $2 billion may be used to offset state General Fund costs for certain state health programs, such as the Genetically Handicapped Persons Program (GHPP) and the California Children’s Services Program (CCS), over the five–year period. Another $1.9 billion may be used to offset some of the uncompensated care costs that public hospitals incur when treating the uninsured. The waiver also established a new $3.4 billion Delivery System Reform Incentive Pool (DSRIP) that is used to encourage infrastructure development, innovative models of care delivery, improved care for certain diseases, and more broad improvements in public hospital care.

The administration has stated its commitment to adopting the optional Medicaid expansion authorized under ACA beginning January 1, 2014. The Governor’s budget summary document presents two distinct approaches—a state–based expansion and a county–based expansion. However, the administration neither indicates which approach it prefers nor provides an estimate of the fiscal effects on the state for either approach. Accordingly, the budget does not reflect any costs or savings related to the optional Medi–Cal expansion. The Governor’s budget summary notes that counties will realize savings associated with MIAs becoming eligible for Medi–Cal under the expansion. It further asserts that state implementation of ACA will require it to assess how much of these county savings “should be redirected to pay for the shift in health care costs to the state.” While the administration has not clarified how this redirection would occur, it suggests possible changes in the state–county fiscal relationship.

State–Based Expansion Approach. Under the state–based expansion approach, the state would build upon the existing state–administered Medi–Cal Program and managed care delivery system. Aside from long–term care, covered benefits for the expansion population would be similar to benefits available to the currently eligible population. According to the administration, this option would require a discussion with the counties around the appropriate state and local relationship in the funding and delivery of health care, and what additional programs the counties should be responsible for if the state assumes the majority of the nonfederal health care costs for the expansion population. (Currently, the counties are generally responsible for paying for the nonfederal share of health care costs for the expansion population.) Under the Governor’s proposed state–based approach, the counties would assume programmatic and fiscal responsibility for various human services programs, such as subsidized child care.

County–Based Expansion Approach. Under this approach, the counties would have operational and fiscal responsibility for implementing the Medi–Cal expansion. The financial responsibility for the nonfederal share of Medi–Cal costs for the expansion population would belong with the counties. Operational responsibilities include some functions currently performed by the state and Medi–Cal managed care plans to administer the program such as:

- Establishing networks of providers to deliver health care services.

- Setting payment rates to providers.

- Processing claims billed by providers.

Counties could build upon their existing medically indigent programs and LIHPs to operate the expansion. The county–based expansion would meet statewide eligibility standards and cover a minimum benefits package similar to coverage requirements for health plans offered on the Exchange. Counties would also have the option of covering additional benefits (other than long–term care) for the expansion population. The administration indicates this approach would likely require federal approval.

The optional Medi–Cal expansion presents a number of important fiscal and policy considerations for the Legislature. Below, we provide our assessment of (1) the major policy benefits of the expansion, (2) the major fiscal effects—on both the cost and savings fronts—an expansion would have on state and local governments, (3) whether or not, on balance, the state should adopt the expansion, (4) what approach should be taken to implement the expansion if adopted, and (5) what types of changes to the state–local fiscal relationship would be appropriate under such an adopted expansion.

Perhaps the primary policy merits of adopting the expansion relate to the benefits associated with increasing the number of Californians with health coverage—specifically low–income adults who are citizens and legal residents.

Expansion Would Increase Health Coverage for Low–Income Adults. While it is certain that a number of individuals currently without health coverage would ultimately obtain coverage under the expansion, there is significant uncertainty regarding this number. While some of the newly eligible Medi–Cal enrollees currently receive health coverage from county–based programs, including county indigent programs or LIHPs, indigent adults with incomes below 133 percent FPL yet too high to qualify for coverage in some counties would gain access to health coverage under the expansion. In addition, in many cases, the coordination of the services delivered would potentially be much better under the Medi–Cal Program (discussed in more detail below).

Estimates of the newly eligible population range from 1.4 million to nearly 3 million individuals. Under the expansion, and other provisions of the ACA that are intended to encourage individuals to obtain health coverage, estimates suggest that roughly 50 percent to 75 percent of the newly eligible population would likely enroll in Medi–Cal. Based on our review of the literature, we believe the expansion would result in about 1.2 million new Medi–Cal enrollees by 2017. Plausible estimates, however, range from 750,000 to about 2 million newly eligible Medi–Cal enrollees.

Health Coverage Has Significant Benefits for Enrollees. Generally, obtaining health coverage increases an individual’s access to health care services. Enhanced access to health care services may lead to improved health outcomes for the newly covered population. For example, individuals with health coverage are more likely to seek primary and preventative health care—services that are likely to result in improved long–term health outcomes. In addition, there is evidence that a coverage expansion for low–income adults would result in lower overall out–of–pocket medical expenditures and medical debt for the newly covered populations, as well as better self–reported health.

The expansion would likely reduce the total amount of uncompensated health care provided in California. In addition to the significant fiscal effects on counties (which we discuss in more detail below), many health care providers—including private hospitals, clinics, and physicians—often provide care for which they receive no direct reimbursement. For example, according to data from the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD), California hospitals provide over $1 billion annually in “charity care”—services provided for which the hospital receives no direct reimbursement. In some cases, providers receive substantial supplemental payments from the federal or state government that help offset some of these uncompensated care costs. Under an expansion, over a million individuals may obtain Medi–Cal coverage—thereby reducing the overall amount of uncompensated care provided in California. A reduction in total uncompensated care costs may reduce some of the associated financial burden on health care providers and other payers for health care services.

The optional expansion would have major fiscal effects on state and local governments, regardless of whether a state–based or county–based approach were adopted. We describe these impacts below.

Expansion Costs Are Subject to Substantial Uncertainty. Estimates of the costs to provide services to the expansion population are subject to considerable uncertainty. Numerous national and state–level studies have attempted to estimate the number of additional enrollees and related government costs that would result from the Medicaid expansion—with significantly varying results. In addition to the typical challenges associated with projecting costs in the Medi–Cal Program—such as projecting underlying caseload growth and medical inflation—several additional major factors contribute to the overall uncertainty when projecting expansion costs, including:

- Eligible Expansion Population. The total number of individuals who would become eligible for the Medi–Cal Program under the expansion is subject to significant uncertainty.

- Take–Up Rates. The percent of eligible individuals who would actually enroll in the expanded program—often referred to as the “take–up rate”—depends on a variety of factors, including behavioral responses to the individual mandate, the effectiveness of outreach activities, and the degree to which a simplified application process reduces barriers to enrollment.

- Per Capita Cost of Coverage. The cost of providing health coverage to the expansion population largely depends on the health characteristics of the newly enrolled population. There are limited data that can be used to precisely estimate the cost to provide health care services to the expansion population since most of these individuals were previously ineligible for Medi–Cal.

- Remaining State and Federal Decisions Contribute to Uncertainty. Remaining state policy decisions could impact the cost of the expansion. For example, it is still unclear exactly which benefits package would be provided to the expansion population—a decision which affects costs. At the federal level, a reduction in the federal matching rate for the expansion population as a method to reduce federal deficits would increase the nonfederal share of costs and potentially significantly increase nonfederal costs.

To illustrate the broad range of potential Medi–Cal expansion costs, we estimated costs over a ten–year period under three scenarios, each involving a different set of assumptions regarding the eligible population, take–up rates, and average cost per new enrollee, as seen in Figure 6. (We note that these are estimates of the cost of providing health care services to the expansion population. They do not include administrative costs.) The potential for the particular assumptions used in each of these three scenarios is based on our review of a wide variety of studies and reports, including: (1) models that attempt to predict the size of the expansion population, (2) previous studies analyzing Medicaid take–up rates in California and across the country, (3) information on costs to provide services to nondisabled adults currently in the Medi–Cal Program, and (4) preliminary cost information from county–run Coverage Initiaves and LIHPs.

Figure 6

Range of Estimated Annual Medi–Cal Costs for Expansion Population Under the ACAa

(Dollars in Millions)

|

State Fiscal Year

|

Low–Cost Assumptions

|

|

Moderate–Cost Assumptions

|

|

High–Cost Assumptions

|

|

Total Cost

|

Federal Funds

|

Nonfederal Funds

|

Total Cost

|

Federal Funds

|

Nonfederal Funds

|

Total Cost

|

Federal Funds

|

Nonfederal Funds

|

|

2013–14

|

$694

|

$694

|

—

|

|

$1,339

|

$1,339

|

—

|

|

$2,844

|

$2,844

|

—

|

|

2014–15

|

1,790

|

1,790

|

—

|

|

3,470

|

3,470

|

—

|

|

7,426

|

7,426

|

—

|

|

2015–16

|

2,167

|

2,167

|

—

|

|

4,222

|

4,222

|

—

|

|

9,125

|

9,125

|

—

|

|

2016–17

|

2,408

|

2,348

|

$60

|

|

4,714

|

4,596

|

$118

|

|

10,290

|

10,032

|

$257

|

|

2017–18

|

2,546

|

2,406

|

140

|

|

5,009

|

4,733

|

275

|

|

11,043

|

10,436

|

607

|

|

2018–19

|

2,697

|

2,522

|

175

|

|

5,332

|

4,985

|

347

|

|

11,872

|

11,101

|

772

|

|

2019–20

|

2,853

|

2,610

|

242

|

|

5,668

|

5,186

|

482

|

|

12,746

|

11,662

|

1,083

|

|

2020–21

|

3,026

|

2,723

|

303

|

|

6,042

|

5,438

|

604

|

|

13,722

|

12,350

|

1,372

|

|

2021–22

|

3,213

|

2,892

|

321

|

|

6,448

|

5,803

|

645

|

|

14,789

|

13,310

|

1,479

|

|

2022–23

|

3,403

|

3,063

|

340

|

|

6,862

|

6,176

|

686

|

|

15,894

|

14,305

|

1,589

|

|

Key Assumptions

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eligible population in 2014

|

1.4 million

|

|

|

1.8 million

|

|

|

2.8 million

|

|

Average take–up ratesb

|

50%

|

|

|

65%

|

|

|

75%

|

|

Annual average cost per new enrollee in 2014

|

$3,000

|

|

|

$3,500

|

|

|

$4,000

|

We consider the moderate–cost scenario the most likely of the three scenarios presented. In our view, the low– and high–cost scenarios are plausible, but not likely.

Short–Term Nonfederal Cost of Expansion Would Be Minor. Under all three scenarios illustrated in Figure 6, there would be no costs to the state as a whole through 2015–16 because the federal government would pay 100 percent of the cost of health services. Under the moderate–cost scenario, the state as a whole would begin to incur costs in the low hundreds of millions of dollars starting in 2016–17 as the federal matching rate begins to decline.

Estimated Long–Term Costs of Health Services Vary Widely, but May Be Substantial. Under our moderate–cost scenario, nonfederal expansion costs increase to over $600 million annually beginning in 2020–21 when the state as a whole would become responsible for 10 percent of the costs. Under the alternative low– and high–cost scenarios, nonfederal expansion costs could be as low as $300 million or as high as $1.3 billion annually beginning in 2020–21. Under all three scenarios, the federal government would pay about 94 percent of the expansion costs over the ten–year period, with state or counties paying the remaining 6 percent.

Uncertain, but Relatively Minor Costs for Eligibility Determinations. It is important to note that while an enhanced federal match would be applied to the health care services provided to the Medi–Cal expansion population, this enhanced federal match is not available for some administrative costs, such as costs associated with conducting eligibility determinations. (There is, however, an enhanced federal match for changes to technological systems that need to be made in order to conduct Medicaid eligibility determinations under the ACA.) Therefore, the state as a whole would pay the traditional 50 percent cost–share for some of the additional costs of determining eligibility for the expansion population. The conversion to MAGI eligibility and other changes that streamline the eligibility processes would likely result in some efficiencies and lower per capita eligibility costs. However, some of the details of the eligibility determination process under the ACA are still being determined at the state and federal levels. These unresolved policy decisions and implementation details make the future costs for eligibility determinations for the expansion population highly uncertain.

Significant Federal Funding Would Offset County Costs for Certain MIAs. As discussed above, health care that is currently provided to the expansion population is largely funded by counties. The expansion would leverage a significant amount of federal funding to provide care to the medically indigent population that would become eligible for Medi–Cal. Generally, this population is currently the programmatic and fiscal responsibility of counties. The total number of individuals who are currently enrolled in county–based programs who would become eligible for Medi–Cal under the expansion is uncertain because the income thresholds and residency requirements used in these county programs vary. However, based on our preliminary estimates, almost 600,000 individuals who are currently enrolled in county–based programs would transition to Medi–Cal under an expansion. Once enrolled in Medi–Cal, the enhanced federal funding available for health services provided to these individuals would almost entirely offset current county costs in the near term and mostly offset county costs in the long term.

Data Limitations Make County Savings Estimates Subject to Considerable Uncertainty. Poor data availability makes estimating county savings difficult. The state does not currently collect data on county spending for MIAs. Perhaps more importantly, there is no single source of information that can be used to precisely estimate county spending on the portion of the medically indigent population that would become newly eligible for Medi–Cal.

Preliminary Analysis Indicates County Savings Likely Range From $800 Million to $1.2 Billion. In our view, the MCEs provide a reasonable starting point for estimating current county spending on the expansion population. The number of MCE enrollees is well known, as shown in Figure 5. Unfortunately, it will take at least a couple of years for counties to complete the process of calculating, reporting, and reconciling costs for health care services provided to MCE enrollees. In the absence of reliable cost information for current MCE enrollees, we used per–enrollee cost information from the Coverage Initiatives to develop a proxy for per–enrollee MCE costs. A preliminary evaluation of the Coverage Initiatives conducted by the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research indicates that average per–enrollee costs were $3,861 and $3,312 annually in the first and second years of implementation, respectively. We note, however, that, as a proxy for MCE costs, the per–enrollee cost information from the preliminary evaluation of the Coverage Initiatives has a few significant limitations, including:

- Cost Estimates Are Based on Preliminary Reports From Counties. Although the Coverage Initiatives began operating in 2007–08, the publicly available cost information is still preliminary and subject to final reconciliation. In addition, some counties may not have reported cost information that they knew was ineligible for federal reimbursement.

- Some Coverage Initiatives Targeted High–Risk Populations. In a few counties, enrollment for the Coverage Initiatives was targeted toward high–risk populations with chronic conditions, such as diabetes and hypertension, or individuals with urgent medical conditions. The MCEs generally focus enrollment on a broader population that likely has fewer health risks and lower per–enrollee costs.

- Coverage Initiatives Had Fewer Federal Requirements. Under the terms of the new waiver, the MCEs must meet certain requirements that were not part of the Coverage Initiatives, such as the requirement to provide HIV/AIDS drugs. The additional MCE requirements will likely result in higher per–enrollee costs, all else equal.

Given these limitations, we used a somewhat broader range of per–enrollee cost from $3,000 to $4,000 annually (total funds) to estimate MCE costs. Using this range of per–enrollee costs, we estimate that counties’ nonfederal spending on MCE enrollees as of October 2012 is likely between $700 million and $950 million annually.

Additionally, a portion of the expansion population is not eligible for an MCE but is currently enrolled in a medically indigent program in a county that either: (1) does not operate an MCE or (2) operates an MCE with a maximum income threshold below 133 percent FPL. After including a rough estimate of additional spending in county medically indigent programs, we estimate that current nonfederal spending on health care services for the expansion population likely ranges from $800 million to $1.2 billion. While we recognize that this estimated range is based on limited available data, we believe it provides a reasonable basis for ongoing discussions related to reduced county spending under the expansion.

Savings to Counties Would Likely Outweigh Nonfederal Costs, for at Least a Decade. Our preliminary estimates indicate that the direct county savings associated with adopting the expansion likely range from $800 million to $1.2 billion annually. This amount of county savings exceeds our estimates of the most likely annual nonfederal costs associated with providing health care to the expansion population through 2022–23, as shown in Figure 6.

County savings related to the shift of adults from county–based programs into a mostly federally funded Medi–Cal is the most significant fiscal benefit to the state or local governments under an expansion. However, we discuss other significant fiscal benefits that would likely accrue to the state and counties under an expansion.

State May Realize Savings in Certain Health Programs. The expansion would likely reduce state costs in certain state–administered health programs that focus on particular illnesses or diseases, such as GHPP and the Breast and Cervical Cancer Treatment Program (BCCTP). Some individuals currently enrolled in these programs would become newly eligible for Medi–Cal and the state would receive the enhanced federal matching rate. The net fiscal effect on these types of state programs would depend on future policy decisions about the potential modification or elimination of these existing programs, but state savings could be in the low hundreds of millions of dollars annually.

Reduced State and County Costs for Inmate Medical Services. A Medi–Cal eligibility expansion could result in significant savings from reduced inmate medical services costs. While federal law generally excludes individuals who are inmates being held involuntarily in an institutional setting (such as in county jails and state prisons) from the Medicaid program, there is an important exception to this rule. Specifically, inmates who are referred off–site for inpatient care lasting at least 24 hours are not excluded from participation in the Medicaid program if they otherwise meet the program’s eligibility requirements. In other words, when jail or prison inmates receive such care at a hospital, nursing facility, or other facility that is outside of the correctional system, they can be enrolled into Medi–Cal and a federal match can be applied to the state’s cost of the entire duration of their inpatient stay at the Medi–Cal rate. Most inmates are low–income childless adults and thus many would be part of a Medi–Cal expansion population. Under an expansion, state General Fund savings for prison inmates who would become newly eligible for Medi–Cal is potentially over $60 million annually. For more information on potential correctional savings from a Medi–Cal eligibility expansion, please refer to our recent report,

The 2013–14 Budget: Obtaining Federal Funds for Inmate Medical Care—A Status Report.

The optional Medi–Cal expansion gives California the opportunity to leverage a significant amount of federal funding to pay for health care for certain low–income adults. The expansion would have significant policy benefits, including improved health outcomes for the newly eligible Medi–Cal population. In the short term, fiscal savings to the counties and the state would far outweigh the nonfederal costs associated with providing health care to the expansion population. After several years, when the enhanced federal matching rate is reduced from 100 percent to 90 percent, we estimate that overall savings to the counties and state would likely continue to outweigh costs.

We note that there is a significant uncertainty about the actual costs and savings associated with the expansion. First, the number of adults who would actually enroll in Medi–Cal and the cost to provide services to the new enrollees is highly uncertain. In addition, there is a risk that the federal government would reduce the federal matching rate and, thereby, increase the nonfederal share of cost for providing services to the expansion population. This fiscal risk is somewhat mitigated by the fact that California would be able to opt out of the expansion in the future.

On balance, we believe the policy merits of the expansion and fiscal benefits that are likely to accrue to state and county governments outweigh its costs and potential fiscal risks. Therefore, we recommend the state adopt the optional expansion. Below, we provide our assessment of the two implementation approaches outlined by the Governor and what changes to the state–county fiscal relationship would be appropriate under an expansion.

The administration indicates that it is considering two approaches to the Medi–Cal expansion: a state–controlled or a county–controlled program. Decisions regarding the assignment of responsibility for governmental programs invariably are complex and pose difficult questions regarding the fundamental purpose of programs and the advantages of state versus local control. (We discuss the conceptual advantages of state versus local control over any given program in the nearby box.)

Which Programs Should the State Control? If statewide uniformity is vital because service level variation would impede the achievement of overriding state objectives, conflict with federal requirements, or could create incentives for people to move across county borders, state control of the program typically is the better option. In addition, state control is more appropriate for programs where the costs or benefits of a program are not restricted geographically, and thus individual counties might underinvest in a program because the county does not see the full impact of its actions. Finally, state control over income support programs (including health care for the indigent) makes sense, because it allows the redistribution of income to reflect the resources of the entire state, as opposed to the resources of a specific county.

Which Programs Should Counties Control? County control over programs offers different advantages. Counties have greater ability to adjust programs to meet the needs of their communities and experiment to determine which efforts improve program outcomes. Also, when budget constraints are significant, counties are in a better position to discern what works in their community and preserve the activities yielding the best outcomes. Thus, when program innovation, responsiveness to community interests, and efficiency are critical, it makes sense to assign the program to counties.

In approaching the decision between state and county control over Medi–Cal for the expansion population, we recommend that the Legislature focus on promoting the best health outcomes and program efficiency—and sort out the fiscal issues afterwards. Underlying this view is a belief that government’s job is to provide public services and programs to its residents, and that government’s ability to raise or reallocate revenue is solely a means to the end of providing these services and programs. We also recommend that the Legislature assign program financial responsibility and program authority to the same level of government. Under this approach, efficiency and accountability is promoted because the level of government that determines whether a program is offered pays its resulting bills.

Should the State or Counties Control the Medi–Cal Expansion? In our view, with respect to the delivery of physical health care services to the expansion population, a state–controlled Medi–Cal system makes the most sense for two primary reasons. First, most of the traditional advantages of county–controlled programs (greater ability to experiment with service delivery, modify programs to meet local needs, et cetera) are probably not possible because the federal government likely will require a high degree of uniformity in the delivery of these services. Second, as described in greater detail below, the delivery of health care services to low–income individuals and families would probably be more organized and coordinated under a state controlled system—thereby leading to improved health outcomes for enrollees and potential administrative efficiencies.

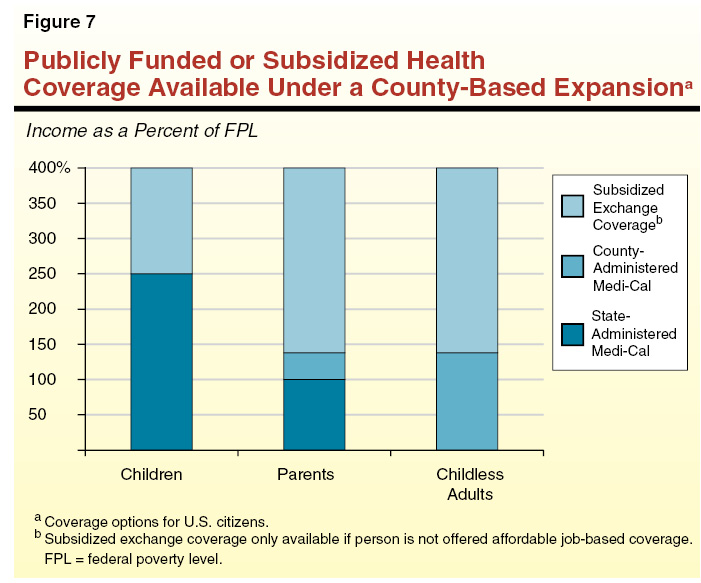

Under the state–based approach, the DHCS and the Exchange would administer the two major free or publically subsidized health coverage options available to non–elderly low– and moderate–income persons—state–administered Medi–Cal (for the currently eligible and expansion populations) and subsidized coverage offered on the Exchange. Under a county–based expansion, coverage available to the expansion population would likely differ from the state–administered Medi–Cal Program in several significant ways—including offering different benefit packages, provider networks, and provider rates. As shown in Figure 7, a county–based approach would effectively create a third major health coverage program—county–administered Medi–Cal—for the expansion population. (Hereafter, we use the term “county–administered Medi–Cal” to describe the county–administered programs that would provide physical health care services to the Medi–Cal expansion population under the Governor’s county–based approach.)

Operating a consolidated state–administered Medi–Cal Program for low–income populations under the state–based approach—rather than operating separate state– and county–administered programs under the county–based approach—would have several significant advantages. We discuss some of the primary advantages below.

Consolidated State–Administered Medi–Cal Program Would Decrease Churning. Low–income households frequently experience changes in income or household composition that cause individuals to gain or lose eligibility for different health coverage programs, potentially causing them to have to change health plans and/or providers—a phenomenon often known as “churning.” Churning has the potential to disrupt coverage, adversely affect health outcomes, and increase administrative costs. A state–based approach would likely result in less churning than a county–based approach because, under a county–based approach, adults with incomes below 133 percent FPL would potentially have to switch programs when income or household composition change. For example, a parent whose income increases from 90 percent FPL to 110 percent FPL may have to switch from the state–administered program to the county–administered program. On the other hand, if a childless adult with income below 100 percent FPL has a child, she might have to switch from the county–administered coverage to state–administered coverage. In both of the above examples, the individuals would not have to switch health plans or providers under a state–based approach.

More Parents Would Share Coverage With Their Children Under a State–Based Approach. Families that obtain coverage from the same source may find it easier to navigate the health care delivery system and access appropriate medical care. Under a state–based approach, essentially all parents and children under 133 percent FPL would be eligible for state–administered Medi–Cal. Alternatively, under the county–based approach, parents with incomes from 100 percent FPL to 133 percent FPL would potentially be eligible for county–administered Medi–Cal and their children would be eligible for state–administered Medi–Cal.

State–Based Approach Would Potentially Reduce Administrative Complexity and Duplication. Creating a new county–administered Medi–Cal Program would run counter to recent state efforts to consolidate health coverage programs for low–income populations. For example, California is in the process of consolidating its two largest health coverage programs for low–income families and children, Medi–Cal and HFP—a change that is partially intended to streamline and simplify the administration of health coverage programs prior to ACA implementation in 2014. The county–based approach has the potential to create additional administrative complexity by creating a new county–administered Medi–Cal Program in each county that would have to coordinate its activities with the state–administered Medi–Cal Program and the Exchange. In addition, as discussed in more detail below, many counties would have to build the infrastructure needed to conduct many of the administrative activities that are already performed by DHCS and Medi–Cal managed care plans—including contracting with providers and/or health plans, setting provider rates, and processing claims.

The two expansion approaches outlined by the administration would likely create very different systems for organizing and coordinating care delivered to the expansion population. It is our understanding that, under the state–based approach, the state would attempt to contract with Medi–Cal managed care plans to arrange for the delivery of care to all new enrollees. For example, managed care plans would perform the following functions:

- Establish networks of providers to deliver health care services.

- Set payment rates to providers.

- Process claims billed by providers.

Under the county–based approach, counties would be responsible for performing these same tasks. The administration indicates that counties would build on their existing medically indigent programs and LIHPs to deliver care to the expansion population.

Medi–Cal Managed Care Plans Have Significant Experience Organizing and Coordinating Care. In 2012–13, approximately 5.4 million out of over eight million Medi–Cal enrollees are expected to receive care from Medi–Cal managed care plans. In most large counties, these plans have significant experience coordinating care for low–income populations, including an established process for assigning enrollees to a primary care provider and emphasizing preventative care as a way to avoid more serious medical conditions that result in unnecessary hospitalizations. In addition, managed care plans also have significant experience with the administrative activities that are typical of an organized care delivery system.

While Certain Counties Have Made Progress Developing Organized Systems of Care . . . Historically, many county medically indigent programs provided fragmented and episodic care, with limited care coordination and little emphasis on primary care or preventative care. However, in recent years, some counties have improved their systems for delivering care. For example, through the Coverage Initiatives, some counties made significant progress developing provider networks, assessing access to specialists, managing referrals, offering disease management programs, and building an infrastructure to promote and monitor quality. Many of these counties were able to leverage existing health systems and local managed care plans, as well as create new relationships with private providers to accomplish these goals. Under the LIHPs, these counties have an opportunity to build upon the progress under the Coverage Initiatives, and new counties operating LIHPs have opportunities to achieve similar progress toward building organized and coordinated systems of care.

. . . Significant Challenges Remain. Despite the improvements made in certain county delivery systems under the Coverage Initiatives, significant obstacles to implementing the county–based expansion statewide remain. We have serious concerns about counties’ capacity to successfully implement a coverage expansion of this magnitude by January 1, 2014. Many counties started operating LIHPs within the last couple of years and some counties do not currently operate LIHPs. At this point, it is unclear how much progress recently established LIHPs have made in establishing provider networks and coordinating care. In addition, despite improvements in care delivery made under the Coverage Initiatives, many of these counties may lack the administrative resources needed to implement the expansion by January 1, 2014, such as the ability to quickly secure contracts with additional providers to serve the additional enrollees and develop the capacity to process a large number of additional claims. Some counties may be able to leverage existing relationships with their local managed care plans or other third–party administrators to perform these activities. However, in our view, many counties lack the existing relationships and infrastructure necessary to effectively implement these changes, particularly in the short term.

What if Certain Counties Are Unwilling or Unable to Adopt the Expansion? As discussed above, many counties may lack the infrastructure necessary to implement an expansion by January 1, 2014. Under the county–based option, the administration indicates that there would be statewide eligibility standards, but only counties would offer coverage to the expansion population—a state–administered program for the expansion population would not exist. At this time, it is unclear how the county–based expansion would be implemented statewide if certain counties are either unwilling or incapable of implementing the expansion.

Federal Approval of County–Based Approach Is Uncertain. The administration indicates that the county–based approach would require federal approval of a waiver. At this point, many of the details about the county–based approach are unclear so it is difficult to comment with much confidence on the likelihood of obtaining federal approval for such an approach. However, we believe there is a risk that the state might not receive federal approval. The LIHPs were established under California’s Bridge to Reform waiver under the assumption that LIHP enrollees would transition to the state–administered Medi–Cal Program on January 1, 2014. The conditions of the waiver require the state to complete a detailed plan to transition LIHP enrollees to Medi–Cal and the Exchange on January 1, 2014. A county–based approach would require an amendment to the existing waiver and represent a significant change in policy from what was previously approved by the federal government.

Implementation Timelines for County–Based Approach Appear Unrealistic. We believe implementation of the county–based approach by January 1, 2014 may be unrealistic. In addition to the significant amount of work at the county level needed to prepare for a county–based expansion, successful implementation by January 1, 2014 depends on quick action from both the state and the federal government on major issues. As discussed above, there is currently very little detail about the structure of a county–based approach and how it would be implemented. The Legislature would need to resolve a number of major policy and fiscal issues prior to passing legislation adopting the county–based expansion. Furthermore, after legislation is passed, the state would need to secure federal approval of a waiver. The process of submitting a waiver and receiving federal approval often takes several months, especially for a proposal of this scope.

Implementation Challenges Under State–Based Expansion Are Less Severe. Many of the implementation obstacles that we identified above would not exist under a state–based approach. However, a significant amount of effort prior to January 1, 2014 would still be required. For example, Medi–Cal managed care plans would need to prepare for roughly one million additional Medi–Cal enrollees. This would likely require securing new provider contracts in order to have an adequate network of providers to accommodate the additional enrollment. Given the significant experience managing care for the Medi–Cal population and recent transitions of additional enrollees into managed care, these plans are likely better equipped to handle the task of expanding their provider network to handle additional enrollees than the counties. The state would also need to continue to plan and implement the successful transition of MCE enrollees from county–based coverage under a LIHP into Medi–Cal managed care plans. While these activities would require a significant amount of effort, we believe a state–based expansion has a much greater likelihood of being successfully implemented by January 1, 2014 than a county–based expansion.