January 27, 2016

Evaluation of the School District of Choice Program

Executive Summary

State Faces Key Decision About Whether to Reauthorize “District of Choice” Program. A state law adopted in 1993 allows students to transfer to school districts that have deemed themselves Districts of Choice. Two main features distinguish this program from other interdistrict transfer laws. First, Districts of Choice must agree to accept interested students regardless of their academic abilities or personal characteristics. Second, interested students generally do not need to seek permission from their home districts. With the program scheduled to sunset on July 1, 2017, the state now faces a key decision about whether to reauthorize it. This report responds to a legislative requirement that we evaluate the program and provide recommendations concerning its future.

Major Findings

State Has 47 Districts of Choice Serving 10,000 Transfer Students. Participating districts represent 5 percent of all districts in the state and participating transfer students represent 0.2 percent of statewide enrollment. Participating districts include a number of small districts located throughout the state as well as several large districts located near the eastern edge of Los Angeles County. Five large districts serve nearly 80 percent of all participating transfer students.

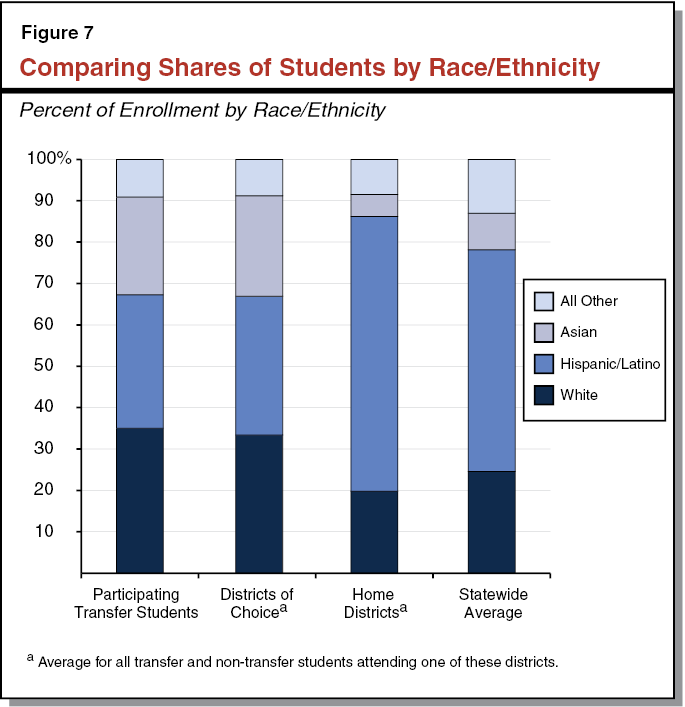

Transfer Students Have Varied Demographic Backgrounds. We found that 27 percent of participating transfer students come from low–income families. We also found that transfer students are 35 percent white, 32 percent Hispanic or Latino, 24 percent Asian, and 9 percent other groups. These percentages are similar to the average for all students attending Districts of Choice. Transfer students are, however, less likely to be low income or Hispanic than the students attending their home districts.

The Program Provides Transfer Students With Additional Educational Options. Students often participate in the District of Choice program to pursue academic opportunities unavailable in their home districts. The most common opportunities sought by transfer students are college preparatory programs (such as the International Baccalaureate program), academies with a thematic focus (such as science or language immersion), and schools with a specific instructional philosophy (such as project–based learning). Other students transfer because they are seeking a fresh start at a new school or because they want to attend a school that is more conveniently located.

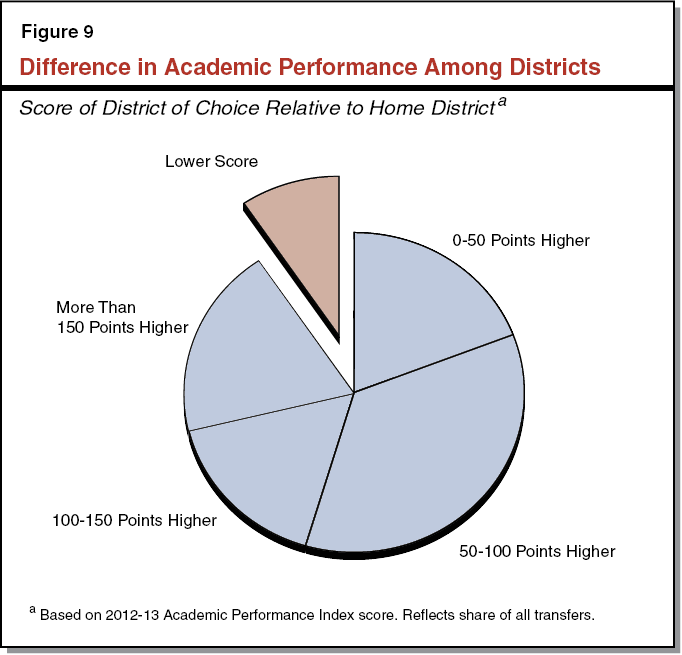

Almost All Students Transfer to Districts With Higher Test Scores. The average District of Choice has test scores well above the state average, whereas the average home district has test scores slightly below the state average. Available data show that more than 90 percent of students transfer to districts with higher test scores than their home districts.

Home Districts Often Respond by Improving Their Instructional Offerings. Most of the home districts we interviewed had responded to the program by taking steps to gain greater clarity about the priorities of their communities and by implementing new educational programs. Most home districts also had improved their test scores over time. Districts reported that their efforts usually resulted in at least some reduction in the number of students seeking to transfer out.

Program Oversight Has Been Limited by a Lack of Data and Flaws in the Audit Procedure. Though the law requires Districts of Choice to produce annual reports containing information about the number and characteristics of their transfer students, the state has never collected these reports. In addition, the audit requirement the state added to the program in 2009 has been implemented inconsistently and contains no mechanism to address any compliance problems.

Recommendations

Reauthorize Program for at Least Five More Years. We think the strengths of the program, including additional educational options for students and improved district programs, justify reauthorization. Eliminating the program, by contrast, would be disruptive for existing transfer students and deny future transfer students the educational options that have helped previous cohorts of students. For these reasons, we recommend the state reauthorize the program for at least five more years, the minimum amount of time we think the state would need to collect better data and assess the effects of our other recommendations.

Repeal Cumulative Cap. In tandem with reauthorizing the program, we recommend the Legislature repeal a cap that limits cumulative participation in the program. This cap currently makes the program unavailable in certain districts regardless of student interest or program quality. In addition, the state modified the program in 2009 to allow districts to prohibit transfers that would notably worsen their fiscal condition. With this provision in place, we believe the cumulative cap is no longer necessary.

Assign the California Department of Education Specific Administrative Responsibilities. We recommend the Legislature require the California Department of Education to (1) maintain a list of the Districts of Choice in the state, (2) ensure all districts submit their annual reports in a complete and consistent format, (3) post these annual reports and other program information in one location on its website, (4) provide information to districts about the program, and (5) explore the possibility of collecting statutorily required program data using the state’s existing student–level data system. These efforts would help the Legislature monitor the program and help families learn about their transfer options.

Implement a New Oversight Mechanism. We recommend the state replace the existing audit requirement with a new system of oversight administered by county offices of education. Under the new system, a home district that was concerned a District of Choice was not following the law could bring its concern to its county office of education. If the county office of education determined that the District of Choice was out of compliance, the District of Choice would be required to correct the problem before accepting additional transfer students.

Improve Local Communication. We recommend the state require Districts of Choice to provide nearby home districts with timely notification of the students accepted through the program. This information would reduce some home districts’ uncertainty regarding the number of transfer students. We also recommend the state require Districts of Choice to post application information on their websites. This information would increase transparency and help the program reach students who might otherwise be unaware of their transfer options.

Introduction

California Has District of Choice Program. California has several laws designed to give parents a choice about which school their children attend. One of these laws is known as the District of Choice program. This program allows a student living in one school district to transfer to another school district that has deemed itself a District of Choice. The program differs from existing interdistrict transfer laws because it does not require students to apply with the home districts they are leaving.

Legislation Authorizes Evaluation of Program. Though the state initially adopted the District of Choice program as a pilot program, it has reauthorized the law several times. The most recent reauthorization extended the program through July 1, 2017. To assist its deliberations about another reauthorization, the Legislature tasked our office with conducting a review of the program. Chapter 198 of 2009 (SB 680, Romero), as amended by Chapter 421 of 2015 (SB 597, Huff), contains the following requirement:

The Legislative Analyst shall conduct, after consulting with appropriate legislative staff, a comprehensive evaluation of the [District of Choice] program and prepare recommendations regarding the extension of the program.

This report responds to this evaluation requirement. First, we outline the main features of the program and compare it with other interdistrict transfer options in California. Next, we describe the findings that emerged from our interviews, data analysis, and review of the available research. Third, we assess the program and describe its strengths and weaknesses. Finally, we make recommendations regarding the future of the program.

Background

In this section, we describe the origins and main features of the District of Choice program. We also compare this program to other transfer options in the state.

History

Legislature Adopts District of Choice Program in 1993. The District of Choice program grew out of an effort in the early 1990s to increase the choices available to students within the public school system. Two main considerations motivated this effort. First, many supporters argued that choice would improve public education by encouraging schools to be more responsive to community concerns and by allowing parents to choose the instructional setting best suited to the needs of their children. Other supporters were concerned about growing interest in a proposal to fund private school vouchers and thought expanding choice among public schools was preferable. These concerns eventually led to the passage of three laws. The first, the Charter Schools Act of 1992, allowed the establishment of publicly funded charter schools that would operate independently from school districts. The second, enacted in 1993, gave students more options to transfer to other schools within the same district. The third law, also enacted in 1993, created the District of Choice program. Although this law was not the first to allow interdistrict transfers, it was designed to be much less restrictive.

State Has Reauthorized Program Five Times. The 1993 legislation implemented the District of Choice program as a five–year pilot, with the first transfers taking effect for the 1995–96 school year. The state extended the program for five more years in 1999, followed by additional extensions in 2004, 2007, 2009, and 2015. With the latest extension to July 1, 2017, the 2016–17 school year will be the last year for the District of Choice program unless the Legislature reauthorizes it.

Program Basics

A School District May Decide to Become a District of Choice. Figure 1 summarizes the key components of the District of Choice program. To participate in the program, the governing board of a school district must annually adopt a resolution declaring its intent to be a District of Choice and specifying the number of transfer students it is willing to accept. A District of Choice typically specifies this number by grade level, depending on available space within each grade.

Figure 1

Key Components of the District of Choice Program

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

aFor districts with more than 50,000 students, the annual cap is 1 percent and the cumulative cap is not applicable. bDifferent rules apply if the District of Choice is a basic aid school district. |

Students Can Leave Their Home District and Attend a District of Choice. Once a district has deemed itself a District of Choice, it may begin accepting attendance applications from students in other districts. Interested students apply directly to the District of Choice and generally do not need to seek permission from the home districts they currently attend. (State law allows a home district to prohibit transfers if certain conditions are met.) Students seeking to transfer in an upcoming school year must submit their applications prior to January 1 of the current school year. Within 90 days of receiving an application, a District of Choice must give each applicant a provisional notification of its decision to accept or deny the transfer application, with final notification required by May 15. Although transfer students are not guaranteed attendance at specific schools, most Districts of Choice allow students to rank their preferred schools and honor any preferences that do not displace students already enrolled. Transfer students accepted into a District of Choice are not obligated to attend. They may withdraw their applications at any time and return to their home districts. The law waives the application timeline for the children of military personnel that have been relocated within the past 90 days. These students may apply at any time and transfer as soon as they are accepted.

A District of Choice May Not Use a Selective Admissions Process. A distinguishing feature of the District of Choice program is the requirement for a participating district to accept all interested students up to the number specified in its board resolution. The law explicitly prohibits giving any consideration to academic or athletic performance or to the cost of educating a student. If the number of applicants exceeds the number of spaces available, the district must conduct a lottery at a public meeting to determine which students it will accept. The district may deny admission selectively only if doing so is necessary to maintain compliance with a court–ordered desegregation plan or admitting the student would require the district to create a new program to serve that student. A district, however, may not invoke the rule about new programs to deny the application of a student with disabilities or an English learner.

Accepted Students Do Not Need to Reapply Each Year. A District of Choice must allow transfer students to continue their attendance in subsequent school years. A district can revoke a transfer only upon recommending a student for expulsion through formal disciplinary proceedings or upon its withdrawal from the program. In the case of withdrawal, the district must allow high school students to continue their attendance until they graduate.

Law Encourages Communication With Families but Sets Few Specific Requirements. The law encourages Districts of Choice to hold hearings that provide interested families with information about their educational options. The law, however, does not require districts to take any special action to publicize their programs. The only specific requirement is that any publicity efforts must be “factually accurate” and avoid targeting individual students based on their academic performance, athletic performance, or any other personal characteristic.

A Home District Can Prohibit a Transfer for a Few Reasons. The law allows a home district to prevent a student from transferring to a District of Choice under a few circumstances. Specifically, a home district may prohibit a transfer that would affect it in one of the following ways:

- Exceed a 3 Percent Annual Cap. A home district may limit the number of students transferring out each year to 3 percent of its average daily attendance for that year. (The annual cap is 1 percent for home districts with more than 50,000 students.)

- Exceed a 10 Percent Cumulative Cap. In addition to the 3 percent annual cap, the law allows a home district to deny transfers that exceed a cumulative cap. (The cumulative cap applies to all home districts except those with more than 50,000 students.) In a 2011 appellate court decision regarding a dispute over the calculation of the cap, the court ruled that the cap is equal to 10 percent of a district’s average annual attendance over the life of the program. Every student who has participated in the program counts toward the cap, even if that student has graduated or left the program. Upon reaching this cap, a home district may prohibit all further transfers.

- Exacerbate Severe Fiscal Distress. As part of the 2009 reauthorization of the program, the Legislature created a new rule allowing a home district in severe fiscal distress to limit transfers. Specifically, if a county office of education assigns the home district a “negative” budget certification, meaning the district will be unable to meet its financial obligations for the current or upcoming year without corrective action, the home district may limit the number of students transferring out. The home district also may limit transfers if the county office of education determines that the home district will fail to meet state standards for fiscal stability exclusively due to the impact of the District of Choice program.

- Hinder a Court–Ordered Desegregation Plan. If a home district is operating under a court–ordered desegregation plan, it may prohibit transfers that it determines would have a negative impact on its desegregation efforts.

- Negatively Affect Racial Balance. Even if a district is not under a court–ordered desegregation plan, it may limit the number of pupils transferring out if it determines the limit is necessary to avoid negative effects on its voluntary desegregation plan or racial and ethnic balance.

An exception to these five rules applies to the children of parents on active military duty. Under legislation adopted in 2015, a home district may not prohibit transfer requests from these students for any reason.

Funding

Funding Follows Students. California funds school districts based on student attendance, with per–pupil funding rates determined by the Local Control Funding Formula. This formula, adopted in 2013–14, establishes a base grant for all students that varies by grade span but is otherwise uniform across the state. Low–income students and English learners generate a “supplemental grant” equal to 20 percent of the base grant. In districts where these students make up more than 55 percent of the student body, the state provides an additional “concentration grant.” The total allotment for each district is funded through a combination of local property tax revenue and state aid. When a student transfers, the home district no longer generates funding for that student and the District of Choice begins generating the associated funding.

Special Rules Apply to Basic Aid Districts. About 10 percent of school districts have local property tax revenue exceeding their allotments calculated under the Local Control Funding Formula. The state allows these districts to keep this additional revenue and treat it like other general purpose funding. These districts are known as basic aid districts (a term derived from a requirement in the State Constitution that all school districts receive a minimum level of state funding equal to $120 per student). Under the District of Choice program, funding for basic aid districts works differently than it does for other districts:

- Transferring From Non–Basic Aid to Basic Aid District. If a basic aid district enrolls a student from a home district that is not a basic aid district, the basic aid district receives 70 percent of the base funding the student would have generated in his or her home district. The student does not generate any supplemental or concentration funding that would apply in the home district. These types of transfers therefore generate some state savings relative to other types of transfers.

- Transferring Among Basic Aid Districts. If a basic aid district enrolls a student from another basic aid district, the law provides that no funding is exchanged between the two districts. As a result, the exchange from the state’s perspective is cost neutral.

State Accountability

Law Requires Each District of Choice to Produce an Annual Report. The law requires each District of Choice to track the following information about its transfer students: (1) the total number of students applying to enter the district each year; (2) the outcome of each application (granted, denied, or withdrawn), as well as the reason for any denials; (3) the total number of students entering or leaving the district each year; (4) the race, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, and home district of students entering or leaving the district; and (5) the number of students entering or leaving the district who are English learners or have disabilities. The law further requires each District of Choice to summarize these data and provide a report by May 15 of each year to (1) its governing board, (2) every adjacent school district, (3) the county office of education, and (4) the California Department of Education.

Law Requires Independent Auditors to Check Compliance. The 2009 reauthorization of the program made certain parts of the law subject to the school district audit process. Every school district in California undergoes an annual audit to verify the accuracy of its financial records and determine if it has spent funds in accordance with various state and federal laws. A district hires its auditor from a list of approved firms. The auditor then conducts an independent review following procedures in the school district audit manual developed by the state. With respect to the District of Choice program, the law requires an auditor to verify that the district (1) implemented an unbiased process for admitting students and used a lottery if oversubscribed, and (2) met the requirement for any communication to be factually accurate. The law, however, contains a special provision prohibiting the state from including any associated instructions in the audit manual. Under this unusual arrangement, a district must ask its auditor to check compliance with program requirements, but the state may not issue instructions telling auditors how to perform this compliance review. State law contains no repercussions if a District of Choice fails to correct issues arising from an audit.

Other Interdistrict Transfer Options

State Has Three Other Interdistrict Transfer Options. In addition to the District of Choice program, the state has three other laws allowing students to transfer to other school districts (see Figure 2). Two of the laws pertain specifically to interdistrict transfers whereas the third pertains to both interdistrict transfers and transfers among schools within the same district (intradistrict transfers). Each law functions independently of the others and includes different requirements for the students and districts involved. Many districts accept students through more than one option. (In addition to the following options, a state law requires a district to allow students to transfer to another school within the district if space is available.)

Figure 2

Interdistrict Transfer Options in California

|

|

|

|

Most Transfers Occur Through a Permit System With the Agreement of the Districts Involved. A longstanding state policy allows a student to transfer from one district to another when both districts sign a permit consenting to the transfer. The law provides each district the discretion to determine the conditions under which it will sign these permits. With respect to students leaving, most districts have a specific and limited set of reasons for which they will release a student. Examples include the availability of child care in the preferred district or the attendance of a sibling already enrolled in the preferred district. With respect to students entering, some districts have adopted standards for academic performance, attendance, and behavior. These standards could involve maintaining a minimum grade point average, arriving to school on time, or avoiding disciplinary problems. Districts may reject applicants who do not meet their standards or revoke the permits of students who fall below those standards. Students denied an interdistrict permit may appeal to their county board of education.

A District May Accept Transfers Based on Parental Employment. In 1986, the state adopted a law allowing any district to admit a student who has at least one parent employed within the boundaries of the district for at least ten hours during the school week. (The law is frequently known as the “Allen Bill” after its original author, Assembly Member Doris Allen.) If a district participates in this program, it may not deny a transfer based on a student’s personal characteristics, including race, ethnicity, parental income, and academic achievement. It may, however, deny the transfer of a student who would cost more to educate than the additional funding generated for the district. Since 1986, this law has operated under a series of temporary extensions.

A District Must Offer Open Enrollment to Students Attending Low–Ranked Schools. In 2010, the state enacted the Open Enrollment Act, a law designed to provide additional options for students attending schools with low test scores. Under the law, the state is to rank schools according to the performance of their students on state assessments and place the 1,000 schools with the lowest scores on the “Open Enrollment List.” A student attending one of these schools can apply to transfer to any other school within or outside of the district that has space available and higher test scores. Regarding transfers out of the district, the district that a student seeks to attend may decide how many students it will accept based on capacity, financial impact, and other factors, but it may not discriminate among students based on their personal characteristics or abilities. Although the Open Enrollment Act has no sunset date, its future is uncertain given the state’s transition to a new accountability system. The current list of low–performing schools is based on student tests taken in 2012–13, the last year the state ranked schools under its former accountability system. The state’s new accountability system, by contrast, currently has no mechanism for ranking schools.

Research Methods

Legislation Envisioned an Extensive Review, but State Has Collected Little Data. The legislation authorizing this evaluation envisioned a comprehensive assessment of the characteristics of participating students, the academic performance of Districts of Choice and home districts, multiyear enrollment trends, and effect of the program on district finances. The law intended the data for this comprehensive evaluation to come from the annual reports that districts are required to submit to the California Department of Education. Upon our inquiry, the department indicated that it had not received these reports. It also indicated that it had not taken any special steps to collect these reports because the law did not specifically require it to do so and because the state did not provide additional funding for this purpose.

California Department of Education Administered a Survey. To provide baseline data, the department agreed to administer a survey in March 2015 asking Districts of Choice to identify themselves and provide information about their transfer students. The data collected through this survey had substantial limitations, with only 6 of the 40 respondents providing complete information. In addition, some districts interpreted the survey instructions differently than others.

Some Districts Confuse the Program With Other Transfer Options. A final issue complicating our tally of participating districts was the confusion surrounding the term District of Choice. We found that some districts mistakenly believed this term referred to the interdistrict permit process. District websites and school board policies often mirrored this confusion. In addition, we learned that districts in a few counties adhere to countywide policies allowing students to transfer for almost any reason. These policies resemble the District of Choice program in some ways but generally rely on the interdistrict permit process.

Report Draws on Several Sources to Understand District of Choice Program. Given the data limitations, we adopted a three–pronged approach to our evaluation. First, we undertook substantial data collection efforts of our own, including personal contact with nearly 100 districts. Second, we arranged more than two dozen interviews with administrators from Districts of Choice and home districts. Third, we reviewed more than 25 studies examining similar interdistrict transfer programs in other states. We also examined administrative records and spoke with researchers and experts familiar with interdistrict transfer programs.

Findings

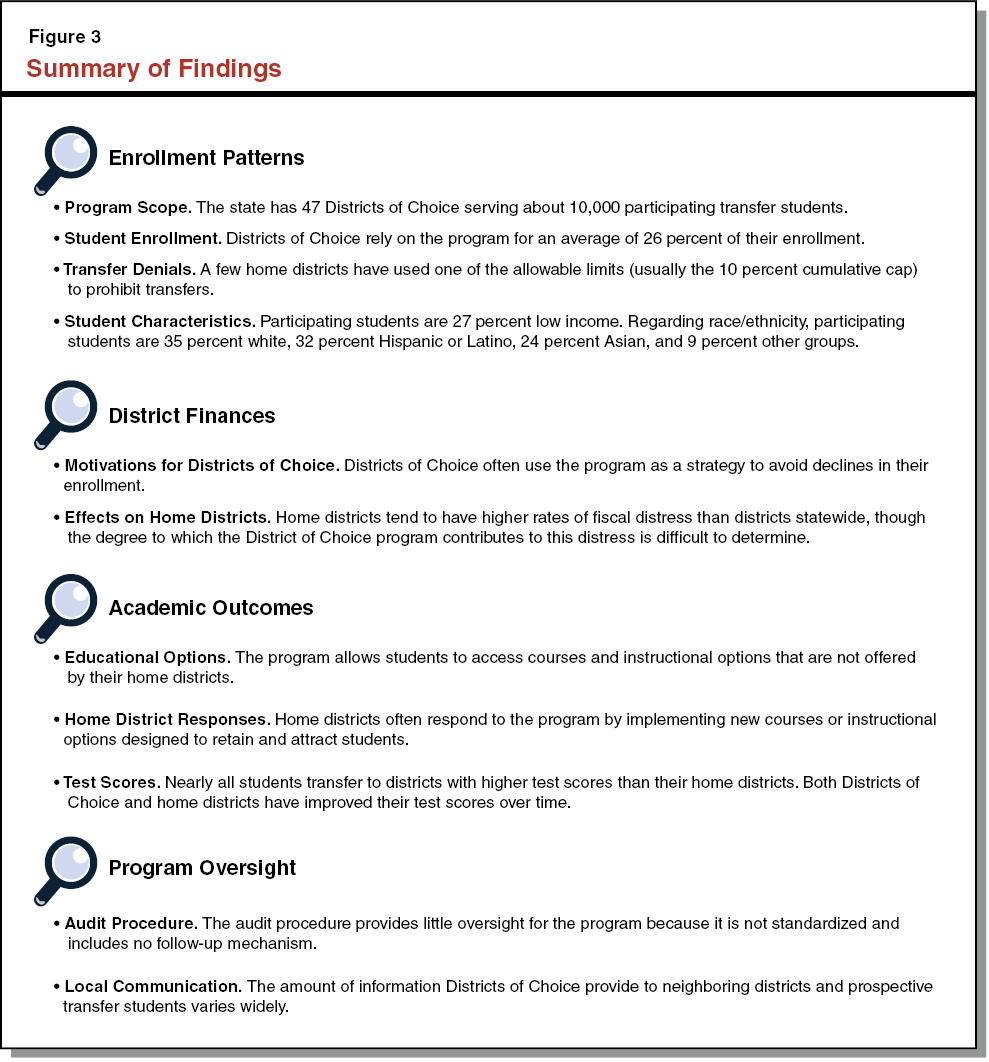

In this section of the report, we share our findings, organizing them around the areas of enrollment patterns, district finances, academic outcomes, and program oversight. Figure 3 provides a summary of these findings, which we discuss in detail below.

Enrollment Patterns

Below, we provide information about the number of districts and students participating in the District of Choice program, compare the number of participating students to the overall enrollment of Districts of Choice and home districts, examine how frequently districts prohibit transfers, and identify the demographic characteristics of students participating in the program.

District and Student Participation

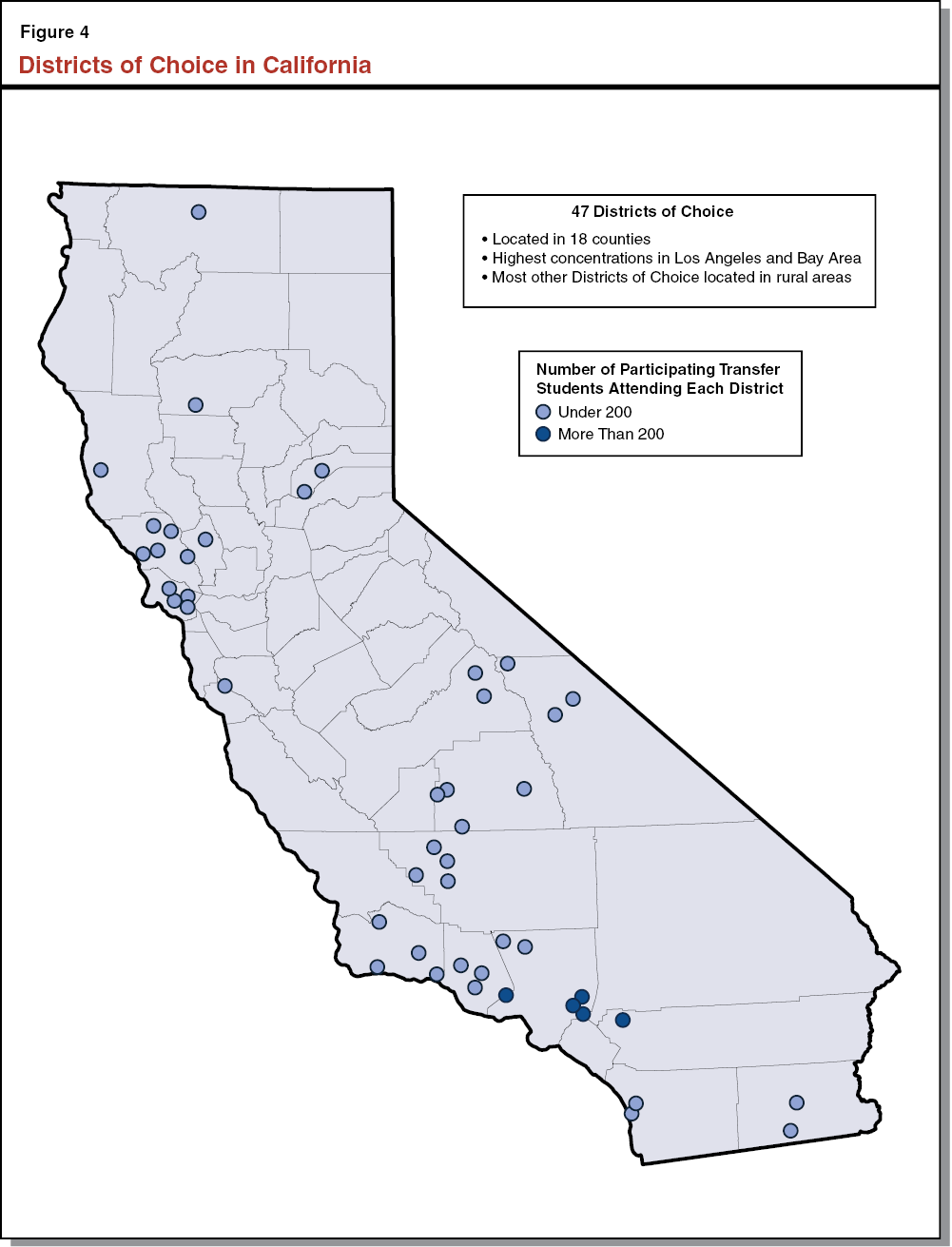

State Has 47 Districts of Choice. We identified 47 Districts of Choice for the 2014–15 school year, representing 5 percent of the 946 districts in the state. Figure 4 shows the location of these districts. As shown in the map, Districts of Choice are most heavily concentrated in Los Angeles and the Bay Area. Although we obtained data for only a single year, the number of participating districts appears to have grown in recent years. In a 2003 study, the California Department of Education identified only 18 Districts of Choice, less than half the number we identified for 2014–15.

State Has About 10,000 Participating Students. We identified 10,202 students who had transferred through the program and were attending a District of Choice in 2014–15. As shown in Figure 5, these students are concentrated in a small number of districts. One district, the Walnut Valley Unified School District in eastern Los Angeles County, accounts for one–third of all participating students. The next largest four districts combined serve 46 percent of participating students. Altogether, about 8,000 participating students are attending one of these five districts. Among the remaining Districts of Choice, 22 are basic aid districts serving a combined 9 percent of participating students and 20 are non–basic aid districts serving a combined 13 percent of participating students. (Four Districts of Choice have no students currently attending through the program. We spoke with two of these districts and learned that they participate in the program to provide an alternative option in case another district ever denies an interdistrict permit.) As described in the nearby box, the program is relatively small compared with other school choice options in the state.

Figure 5

Participation in the District of Choice Program

2014–15

|

District(s) |

District of Choice Students |

Share of All District of Choice Students |

Total District Attendance |

District of Choice Students as Share of Total District Attendance |

|

Walnut Valley Unified |

3,415 |

33% |

14,249 |

24% |

|

Oak Park Unified |

1,691 |

17 |

4,543 |

37 |

|

Glendora Unified |

1,392 |

14 |

7,495 |

19 |

|

Riverside Unified |

892 |

9 |

39,984 |

2 |

|

West Covina Unified |

633 |

6 |

8,888 |

7 |

|

Basic aid districts (22)a |

870 |

9 |

14,631 |

6 |

|

All other districts (20)a |

1,309 |

13 |

10,119 |

13 |

|

Totals |

10,202 |

100% |

99,910 |

10%b |

|

aTwo of the districts in each of these groups—a total of four statewide—have no students currently participating in the program. |

||||

|

bThis percentage is affected by a handful of relatively large districts with relatively few participating students. The district average is 26 percent. |

||||

Program Is Small Compared With Other School Choice Options

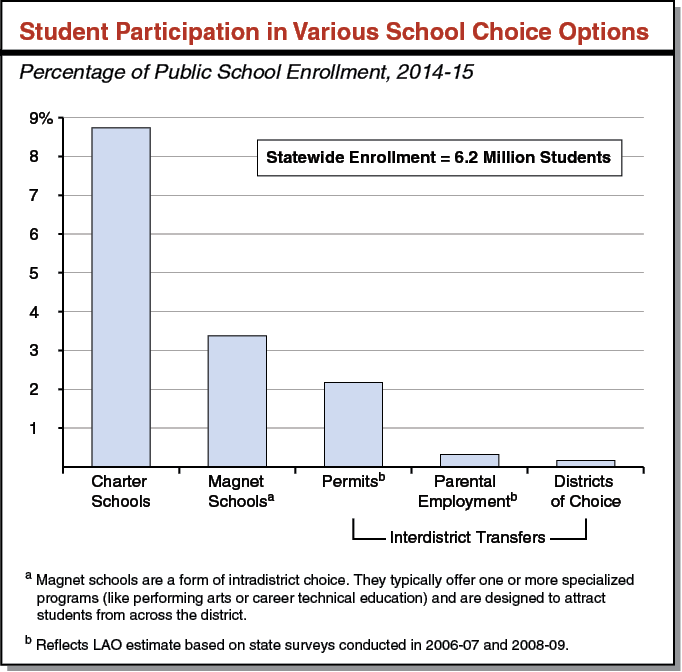

To place the District of Choice program in context, we compared it with the other interdistrict transfer options in the state, charter schools (which provide an alternative to district–run schools), and magnet schools (which are a form of intradistrict choice). The figure below shows the number of students using these options as a share of the 6.2 million students attending public school in 2014–15. Charter schools comprise the most prevalent option, enrolling about 545,000 students (8.7 percent of all students). Magnet schools are the next most common option, enrolling about 210,000 students (3.4 percent). Regarding interdistrict transfers, the available data suggest that roughly 140,000 students (2.2 percent) are using the interdistrict permit process, 20,000 students (0.3 percent) are using the parental employment provision, and 10,000 (0.2 percent) are using the District of Choice program. (An additional number of interdistrict transfers likely occur through the Open Enrollment Act, though the state has little data for this program.)

Apart From Five Largest Districts, Most Districts of Choice Are Small and Rural. The five Districts of Choice with the greatest participation are medium– to large–sized districts, and all serve grades K–12. Four are located in suburban areas and one is located in an urban area. These characteristics differ notably from the other 42 districts participating in the program. Of these districts, 69 percent have fewer than 300 total students, 74 percent serve rural communities, and 79 percent serve only grades K–8.

District Enrollment

Districts of Choice Usually Draw Students From Several Surrounding Districts. We found that participating transfer students come from 197 different home districts. Most Districts of Choice draw students from between two and seven home districts, though a few small districts draw from only one home district and three large districts draw from more than 30 home districts. Transfer activity tends to be highest among adjacent districts, with 77 percent of all participating students transferring to districts that are adjacent to their home districts.

Many Small Districts of Choice Rely on Program for a Significant Share of Students. Districts of Choice rely on the program for varying shares of their total enrollment, with the average District of Choice deriving 26 percent of its enrollment from transfers through the program. This average, however, does not capture key differences based on district size. The average for small–sized districts (fewer than 300 students) is 36 percent. By contrast, the average for larger districts (more than 300 students) is 9 percent.

Most Home Districts Experience Relatively Small Changes in Their Enrollment. The data also reveal that the number of students leaving their home districts tends to be small relative to the enrollment of those districts. Of the 197 home districts, 136 have less than 1 percent of their students attending a District of Choice. Of the remaining home districts, only 16 have more than 5 percent of their students attending a District of Choice. Half of these districts are very small (fewer than 300 students), such that the few students participating in the District of Choice program constitute a relatively large share of their enrollment.

Transfer Denials

Most Districts of Choice Do Not Need to Conduct a Lottery. Based on our interviews, we estimate that approximately one–fourth to one–third of all Districts of Choice receive enough applications to conduct a lottery. The other districts are able to accept all students who apply. Most of the districts conducting a lottery are very small, though one of the five largest Districts of Choice also conducts a lottery. The smaller districts often cite facility constraints as a key reason for not accepting additional students.

Several Home Districts Have Invoked Rules Limiting Transfers. Based on our review, we believe at least four home districts have invoked one of the rules limiting transfers. For the most part, these districts are relying on the 10 percent cumulative cap. In one case, the home district also cited the rule about fiscal distress, and in a second case, the home district also cited the 3 percent annual cap. We also learned that several other home districts are approaching the 10 percent cumulative cap and are thinking about using it to prohibit future transfers.

Student Characteristics

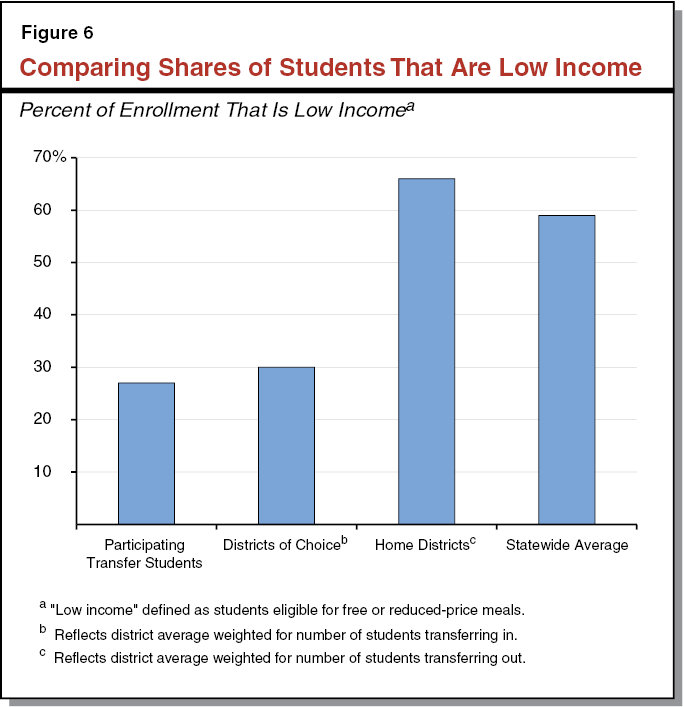

About One in Four Participating Students Is Low Income. Based on information provided by districts, we estimate that 27 percent of participating transfer students are from families with incomes low enough to qualify for the federal free or reduced–price meals program. (To qualify for this program, a family of four needed an annual income of no more than $44,000 in 2014–15.) Figure 6 compares the share of low–income students among participating transfer students to the share among all students attending Districts of Choice, all students attending home districts, and all students in the state. Overall, the share of participating transfer students qualifying as low income is similar to the average for Districts of Choice (30 percent). It is, however, much smaller than the share for home districts (66 percent) and students statewide (59 percent). When we examined transfer patterns, we found that nearly all students (94 percent) transfer to districts with smaller shares of low–income students than their home districts.

White and Hispanic Students Each Account for About One–Third of Participating Students. We found that participating transfer students are 35 percent white, 32 percent Hispanic or Latino, 24 percent Asian, and 9 percent other groups. Figure 7 compares these percentages to the average for Districts of Choice, home districts, and all students statewide. Overall, participating transfer students tend to mirror the profile of the Districts of Choice they attend. Some differences emerged when we compared these students with their home districts. As shown in the figure, Hispanic students transfer at relatively low rates compared with their share of home district enrollment. These students account for 66 percent of the students attending home districts but only 32 percent of participating transfer students. Conversely, white students and Asian students transfer at relatively high rates.

No Differences by Gender, Little Data Regarding Other Student Characteristics. We examined participation by gender and found that males and females participate in the program at similar rates. As requested by the legislation authorizing this evaluation, we also tried to obtain information about the participation of English learners and students with disabilities. Unfortunately, many districts either did not have the information readily available or could not provide the information in a consistent format. Given this limitation, we could not draw any definitive conclusions about the participation of these groups of students.

District Finances

Below, we describe the fiscal considerations that lead districts to become Districts of Choice. We then discuss the fiscal effects of the program on home districts.

Districts of Choice

Larger Districts Often Become Districts of Choice to Address Declining Enrollment. The larger districts we interviewed often reported that their discussions about joining the program began when they were anticipating enrollment declines. By backfilling these declines with transfer students, these districts sought to avoid funding reductions that would have otherwise required changes to their budgets. Some interviewees also commented that their neighboring districts had become less willing to sign interdistrict permits than they were in the past.

Smaller Districts Often Become Districts of Choice to Gain Economies of Scale. The smaller districts we interviewed often reported joining the program to keep their enrollment from dropping to an extremely low level. Their superintendents thought that without transfer students, the districts’ fixed costs would consume a growing share of their operating budgets, thereby constricting their educational programs. They particularly valued the provision allowing students to continue their attendance in the program automatically, noting that this provision allowed them to make more confident enrollment projections.

Compared With Other Transfer Options, Program Is Advantageous for Basic Aid Districts. Though basic aid districts make up only 10 percent of districts in the state, they account for nearly half of all Districts of Choice. Basic aid districts do not receive the 70 percent funding allowance for students who transfer through interdistrict permits or the parental employment option. By comparison, they do receive the allowance under the District of Choice program, making this transfer option more fiscally advantageous for them. (Though state law allows students transferring through the Open Enrollment Act to generate the 70 percent allowance, state records show that no basic aid districts accept students through this program.)

Home Districts

Home Districts Have Fiscal Concerns Associated With Their Declining Enrollment. Administrators for home districts we interviewed were critical of the program and expressed concerns about its fiscal impact. In particular, these administrators were concerned about declining enrollment and corresponding reductions in state funding. Although the state has a “hold harmless” provision that effectively protects a district from year–over–year enrollment declines, administrators nonetheless were concerned about long–term enrollment declines and identified closing schools, laying off teachers, increasing class sizes, and consolidating services as actions they had taken or might need to take in balancing their budgets. District officials emphasized that these actions were difficult and often unpopular in their communities.

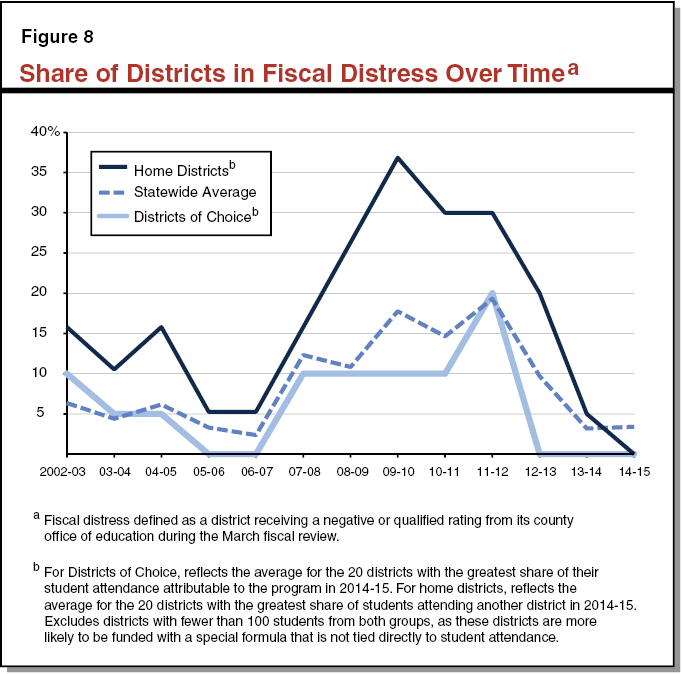

Home Districts Tend to Have Higher Rates of Fiscal Distress, Likely Reflecting Multiple Factors. Figure 8 shows the share of districts in fiscal distress, broken out for Districts of Choice, home districts, and all districts in the state. For this analysis, we considered a district in fiscal distress if it received a qualified or negative budget rating from its county office of education. (County offices of education assign a qualified rating when a district is at risk of not meeting its financial obligations in the current or upcoming two years and a negative rating when a district faces immediate budget problems.) Home districts were roughly twice as likely to be in fiscal distress over the period as the average district in the state, whereas Districts of Choice were slightly less likely to be in distress. We are uncertain to what extent these patterns would have been different had the District of Choice program not existed. Many factors other than interdistrict transfers—including staffing levels, collective bargaining agreements, reserve levels, and overall management—affect fiscal health. Additionally, home districts had higher rates of distress as far back as the early 2000s, when the District of Choice program was notably smaller.

Academic Outcomes

Below, we describe how the program can benefit participating students and outline some of the changes home districts have made to attract and retain students. We also discuss transfer patterns with respect to test scores and describe how district test scores have changed over time.

Transfer Students

Program Provides Participating Transfer Students With Additional Educational Options. During our interviews, we asked Districts of Choice a range of questions about their academic programs and the experiences of their transfer students. During these discussions, interviewees gave many examples of students transferring to participate in educational programs not available in their home districts. For example, several Districts of Choice reported that they offered college preparatory coursework (such as Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate programs) or gifted/talented programs that students would have been unable to take at their home districts. Other districts indicated that they operated the only schools in the area with a specific thematic focus like performing arts or engineering. In some cases, schools within the District of Choice had specialized instructional philosophies. For example, a few Districts of Choice indicated that they offered a project–based learning curriculum that was unavailable in neighboring districts. We also found that the District of Choice program operates in some parts of the state where other school choice options are more limited. For example, we found that roughly half of participating students come from home districts that do not have any charter schools located within their borders.

Program Can Help Students Who Have Struggled Socially or Want to Attend School Closer to Home. In addition to expanded educational options, we found a few other situations under which transferring could help students. For example, a few administrators indicated that they received inquiries from parents whose children had been bullied or were struggling to fit in at their current schools. For these students, transferring to a different district gave them a fresh start. Administrators also indicated that they sometimes received applications from students in adjacent districts who wanted to attend school closer to where they lived. School district boundaries often do not reflect current population patterns, and for some students, a school in an adjacent district may be nearer than the one assigned by their home district.

Surveys Conducted in Other States Find Participating Families Are Highly Satisfied. Though we did not have the resources to survey families participating in the District of Choice program, we did review surveys conducted in three other states with interdistrict transfer programs. These surveys all found that more than 90 percent of families using the program were satisfied or very satisfied with their new schools. In addition, fewer than 10 percent of families were thinking about changing schools again or returning to their home districts. A survey conducted in Minnesota asked parents to elaborate on the behavioral changes they observed in their children during the first year in their new schools. Parents most frequently described improvements in self–confidence, satisfaction with learning, and motivation, with about 60 percent of parents saying their children were doing better in these areas after transferring and less than 3 percent saying their children were doing worse. Administrators for the Districts of Choice we interviewed consistently reported similar results, characterizing their transfer students as happy with their new schools and generally doing well academically. Most administrators of these programs also cited high retention rates, with relatively few students returning to their home districts.

Home District Programs

Most Home Districts Started Taking Deliberate Action to Retain Students and Achieved Some Success. Despite their reservations about the program, most home districts we interviewed had responded to the program by trying to do more to retain and attract students. As a first step, these districts studied the factors causing students to leave. For example, two home districts we interviewed reported convening an intensive series of meetings with their parents and community members to ask them why students were leaving and how they could draw these students back. Several administrators analyzed administrative records, including interdistrict permit applications, to understand why parents might be choosing other districts. Some administrators examined successful educational programs operating in nearby districts. These activities led home districts to identify new educational programs and make the implementation of these programs a high priority. The programs identified through this process often included some combination of language immersion programs, advanced college preparatory programs, and academies focused on science or technology. A few districts identified other changes desired by their communities, like expanded child care or more opportunities to transfer within the district. Asked to describe the results of their efforts, most districts reported moderate declines in the number of students seeking to leave. A few districts also noted that their new programs had begun to attract students from other districts.

District Test Scores

Nearly All Students Transfer to Districts With Higher Test Scores. Until 2013–14, the state gave every school district a score on the Academic Performance Index (API). The API was a composite number representing performance on state tests administered to students in grades 2 through 12. In 2012–13, the average score was 801, with district scores ranging from a low of 566 to a high of 969 (with a maximum possible score of 1,000). The average score for Districts of Choice was 871, corresponding to performance well above the state average. The average score for home districts was 785, corresponding to performance slightly below the state average. (Our analysis weighted each district to reflect the number of participating transfer students.) As shown in Figure 9, nearly all students (90 percent) are transferring to districts with higher API scores than their home districts.

Districts of Choice and Home Districts Are Improving Their Academic Performance Over Time. Although Districts of Choice have higher API scores than home districts, we found that both groups of districts have improved their test scores over time. Over the five–year period beginning in 2008–09 and ending in 2012–13, home districts improved by an average of nine points per year and Districts of Choice improved by an average ten points per year. By comparison, districts statewide improved by an average of seven points per year over the same period. (For this analysis, we limited our focus to the 20 largest Districts of Choice and the 20 home districts experiencing the greatest change in their enrollment.)

Program Oversight

Below, we analyze the audit requirement the state implemented in 2009. We then cover a few other issues involving communication between Districts of Choice and home districts and between Districts of Choice and prospective transfer students.

Audit Procedure

Audit Requirement Has Two Key Limitations. First, the scope of this compliance review is inconsistent across districts. In some districts, the auditor conducts a detailed review and asks to see board resolutions, student applications, and other supporting records. In other districts, the auditor does not examine the program. These inconsistencies appear to be a result of the law prohibiting the state from issuing audit instructions for the program. Second, the state has established no system for acting upon any problems identified during an audit. The state has set no penalties for a district that is flagged by its auditor nor created a follow–up mechanism to ensure that a district corrects any problems moving forward.

Local Communication

Level of Communication Between Districts Is Inconsistent. We asked Districts of Choice and home districts about their level of communication with each other. Overall, we found that local practices vary widely. Some Districts of Choice make special efforts to communicate with home districts and notify them promptly upon accepting transfer students. In other cases, the communication between districts is limited and home district administrators may not know how many students are transferring or which other districts these students are attending until they are asked to forward student records. (These record requests may occur months after students apply and are accepted by Districts of Choice.) These administrators indicated that without this transfer information they faced greater difficulty planning their staffing levels and instructional programs.

In a Few Cases, Difficult to Know Whether a District Participates in the Program. A few Districts of Choice conduct extensive publicity efforts involving press releases, newspaper advertisements, community events, and tours of their schools. Most other Districts of Choice provide basic information about the program on their websites. We found, however, that a few districts do not provide any readily available information to indicate their participation in the program. These districts rely entirely on word of mouth to attract students.

Assessment

In this section of the report, we review the main strengths of the program, largely relating to enhanced choice for students. We then review the main weaknesses of the program, largely relating to data, oversight, and local communication.

Strengths

Provides Additional Educational Options for Participating Students. The District of Choice program appeals to many types of families seeking alternative educational options. Students can benefit from this option in one or more ways, including being able to enroll in a school with an educational philosophy aligned to their educational goals, participate in programs or classes that are unavailable in their home districts, or obtain a fresh start if they have struggled in another school. The program is relatively small in comparison to other choice programs, but it provides an alternative when these options are unavailable and when neighboring districts no longer are granting interdistrict permits. Based on surveys conducted in other states and feedback from administrators in California, participating students and their parents appear to be very satisfied with these options. Additionally, the program serves a broad swath of students, with participating students from a mix of ethnic groups, income levels, and geographic regions of the state.

Encourages Home Districts to Improve Their Programs. Several of the home districts most affected by the program implemented new educational programs to attract and retain students. These districts also took special steps to gain greater clarity about the priorities of their communities. In addition, despite some of the fiscal challenges facing home districts, test scores for the students remaining in these districts have continued to improve over time.

Weaknesses

State Lacks Reliable Data for the Program. Although the program has some strengths, we also believe it has a few weaknesses. One weakness relates to data about the program. Though existing law requires Districts of Choice to produce annual reports summarizing the demographic characteristics of participating transfer students, the state in practice has not collected these reports. Without this information, district administrators, Members of the Legislature, and the public will continue to have difficulty monitoring the program. For example, districts implementing new educational programs might wish to know how their new programs have affected the number of students seeking to enter or leave their districts. State policymakers might wish to know whether participation in the program is growing or declining over time and how program participation compares with other transfer options. Parents might wish to have a list of participating districts so that they can consider the options available to their children.

Existing Oversight Mechanism Is Limited. Another weakness relates to the program’s current audit provision. The state added this provision to improve oversight of the program, but inconsistencies in local audit procedures and the absence of any follow–up mechanism mean that this requirement effectively adds little oversight. If a district appears to be out of compliance with the program rules, the law includes no mechanism for an independent entity to investigate and determine whether any corrective action is needed.

Weak Justification for 10 Percent Cumulative Cap. While a cumulative cap might have been reasonable when the District of Choice program was a pilot, we believe its justification has become weaker over time. Though its original objective is not entirely clear from statute, we think the cap was intended to protect home districts from experiencing sizeable drops in enrollment over several consecutive years and losing the associated per–student funding. The state addressed this particular concern, however, when it added the provision in 2009 allowing home districts to deny transfers if facing fiscal distress. Districts also have interpreted and calculated the cap differently, with resulting disputes and litigation. Disagreement still exists regarding the most appropriate way for home districts to calculate the cumulative cap. Perhaps most importantly, we are concerned that the cumulative cap has no link to student interest or program quality. Once reached, the cumulative cap disallows additional participation, even if students remain interested in transferring and quality transfer options remain available.

Communication With Home Districts and Prospective Transfer Students Can Be Limited. Lastly, we have a few concerns about the cases in which Districts of Choice do not provide home districts with timely information about the students who are transferring. Without timely notification, home districts face greater challenges developing their budgets and setting their staffing levels. Moreover, without knowing where students are going, these districts are less likely to discover what factors led students to leave and what actions might address the concerns of those students. We also are concerned about Districts of Choice that do not make their participation in the program easily known to prospective transfer students. In these cases, students who have recently moved to a community or are unfamiliar with interdistrict transfer options are likely to have difficulty learning about the program. Though word of mouth can be an important communication tool, we do not think it should be the only way for students to learn about their transfer options.

Recommendations

In the course of this evaluation, we encountered many competing claims about the merits of the District of Choice program, the appropriate measures of its effectiveness, and its place among other school choice options in the state. The Legislature has grappled with these issues as part of previous deliberations about the program and likely will do so again as it considers whether to extend the program beyond its July 2017 sunset date. In this section of the report, we describe how the Legislature might approach this upcoming decision, offering recommendations that recognize the strengths of the program while addressing its weaknesses.

Reauthorize Program for at Least Five More Years. We recommend the Legislature reauthorize the program for at least five more years. Though a longer period also would be reasonable, we believe five years is the minimum amount of time the state would need to implement and assess the effects of our other recommendations (including the collection and analysis of better data). We believe the benefits of the program, including additional educational options and improved outcomes for students, justify reauthorization. Moreover, eliminating the program would be disruptive for about 10,000 existing transfer students and deny future transfer students the educational options that have helped previous cohorts of students. Eliminating the program would be particularly problematic for a few dozen small districts that have come to rely on the program for a substantial share of their enrollment.

Repeal Cumulative Cap. In tandem with our recommendation to reauthorize the program, we recommend the Legislature repeal the cumulative cap. Repealing the cap would allow students to use the program regardless of where they live or the level of transfer activity in previous years. Moreover, given the state now allows districts to prohibit transfers that would notably worsen their fiscal condition, we believe this cap is no longer necessary.

Assign the California Department of Education Specific Administrative Responsibilities. We recommend the state require the department to undertake certain administrative tasks for the District of Choice program. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature require the department to (1) maintain a list of the Districts of Choice in the state, (2) ensure all districts submit their annual reports in a complete and consistent format, (3) post these annual reports and other program information in one location on its website, (4) provide information to districts about the program, and (5) explore the possibility of collecting statutorily required program data using the state’s existing student–level data system. (Using the state’s existing student–level data system eventually could eliminate the need for districts to produce separate annual reports, thereby reducing costs for both the state and districts.) Given the department has no staff currently dedicated to the District of Choice program, and the department cites lack of staffing as one reason that it has been unable to fulfill these types of administrative responsibilities, we recommend the Legislature provide it with ongoing funding of about $150,000 and one additional staff position.

Implement a New Oversight Mechanism. To address the shortcomings of the audit requirement, we recommend the state replace this requirement with a new oversight system administered by county offices of education. Under the new system, a home district with a concern about a particular District of Choice could file a complaint alleging a violation of a specific provision of the law. The county office of education with jurisdiction over the District of Choice would review the complaint and assess its merit. If the county office of education determined that the District of Choice was out of compliance, that district would be required to correct the problem before accepting any more transfer students through the program. The county office of education also would notify the state of its findings, which would help the Legislature assess the need for any further refinements to the law. This approach would establish a clear standard of review and a clear consequence for noncompliance. In addition, it would be administered by local officials with an understanding of the districts in their counties. The cost to review complaints likely would vary based on the extensiveness, complexity, and seriousness of the charge. We estimate costs per review could range from a few thousand dollars to tens of thousands of dollars. Given the limited number of Districts of Choice, these costs likely would be minor statewide.

Improve Local Communication. We recommend the Legislature add two statutory requirements to improve local communication about the District of Choice program. First, we recommend the state require Districts of Choice, upon accepting transfer students, to provide home districts a list of those students. This requirement would reduce some home districts’ uncertainty surrounding the number of students that transfer. It also would help address some concerns these districts have about the effect of the program on their fiscal planning. Second, we recommend the state require Districts of Choice to post application information on their websites. This information would include the application form and related details such as the deadline to submit applications and the date of the lottery. This requirement would help prospective transfer students learn about the program and offer more transparency regarding the way districts are implementing the program. We think the costs of these requirements would be small, given that some districts already implement them and the required activities likely would need to occur only once per year. Although a few districts might incur small additional costs, these requirements would not constitute a reimbursable state mandate because no district is required to become a District of Choice.

Conclusion

Interdistrict Transfer Policies in California Are Complex and Overlapping. Although our evaluation focused on the District of Choice program, this program accounts for a relatively small share of all interdistrict transfers in California. The state has three other interdistrict transfer options, each with a separate set of rules governing student eligibility, application procedures, accountability, and funding. Although these other options were not a focus of this report, many administrators we interviewed had experience with these options and used them to provide a contrast or comparison with the District of Choice program. Our impression from these conversations is that the interdistrict transfer landscape in California consists of a complex and overlapping set of policies. The chief drawback of this arrangement is that if many districts struggle to keep the options straight, the level of confusion is likely even higher among parents who are searching for the best school for their children.

Broader Review of Transfer Policies Warranted. Given the confusion surrounding the existing laws, we think a broader review of interdistrict transfer policies is warranted over the coming years. In such a review, the Legislature likely would want to take several steps. First, the state could develop goals for its interdistrict transfer programs, which would guide future reauthorizations and facilitate the evaluation of these laws. Second, the state could study its existing transfer programs to determine which meet these goals and whether any of these programs could be consolidated. Third, after identifying the policies most closely aligned with its objectives, the Legislature could work to implement a revamped system of interdistrict choice with clear and strong fiscal incentives, oversight provisions, and transparency measures.