LAO Contact

Related content . . .

September 21, 2016

Improving Education for Deaf and Hard of Hearing Students in California

Executive Summary

Most Students Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing (DHH) Experience Language Delays. California currently serves about 14,000 DHH students a year. Because DHH students cannot respond to spoken language as easily as their hearing peers, they often lag behind in developing important language, social, and cognitive skills. These developmental delays lead to academic challenges, with DHH students as a group performing far behind other student groups on statewide assessments of reading/writing and math.

A Variety of DHH Educational Programs Exist, but Some Students Have More Options Than Others. Several types of DHH educational programs operate in California, with programs varying by classroom setting and instructional approach. Regarding setting, some programs serve DHH students in mainstream classrooms, whereas others serve them in special classrooms consisting either solely of other DHH students or broader groups of students with disabilities. Regarding instructional approach, some DHH programs provide instruction in spoken language, others provide instruction using sign language, and still others use a combination of spoken and sign language. No single programmatic approach works best for all students. Students in some districts, typically large urban districts, tend to have access to more DHH programmatic options than students in other districts. DHH options typically are most limited in small, rural districts.

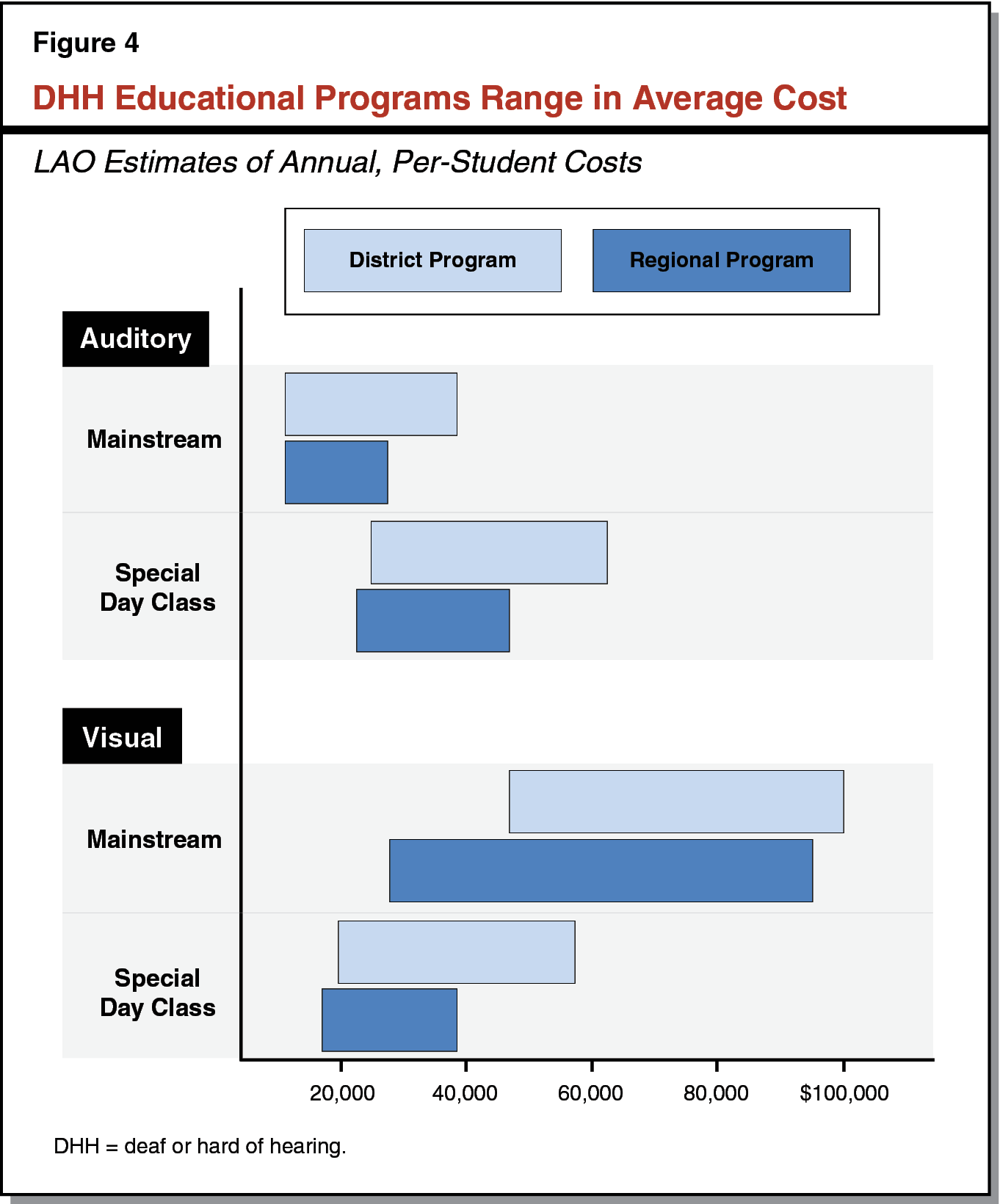

DHH Education Is Costly, but Programs With Many Students Cost Less Than Smaller Programs. The cost of DHH education ranges from about $20,000 to more than $100,000 per student per year. Even using the low end of this range, the state spends significantly more on DHH students than it does on most other student groups, including students with various other disabilities. While DHH educational costs vary for several reasons, programs with many DHH students generally cost less than smaller programs.

Two State Special Schools (SSS) Serve a Small Number of DHH Students at High Cost. The SSS, which are located in Fremont and Riverside, use sign language to educate about 800 DHH students a year. About 60 percent live on campus as residential students, whereas the remaining 40 percent live nearby and commute to school each day. Even though the SSS are larger than most local DHH programs, they currently spend on average $92,000 per student annually, significantly more than most local DHH programs.

Assessment

California Could Address Many DHH Educational Issues by Fostering “Critical Mass.” Programs with a certain number of DHH students (between 3 and 20 students per grade) are said to have critical mass. DHH students in these programs are less likely to be socially isolated and thus more likely to develop important language and social skills. Programs with critical mass also are more likely to offer a variety of DHH instructional approaches, increasing the chances of finding the best fit for each student. Finally, programs with critical mass generally can offer the same services as smaller programs at a lower cost.

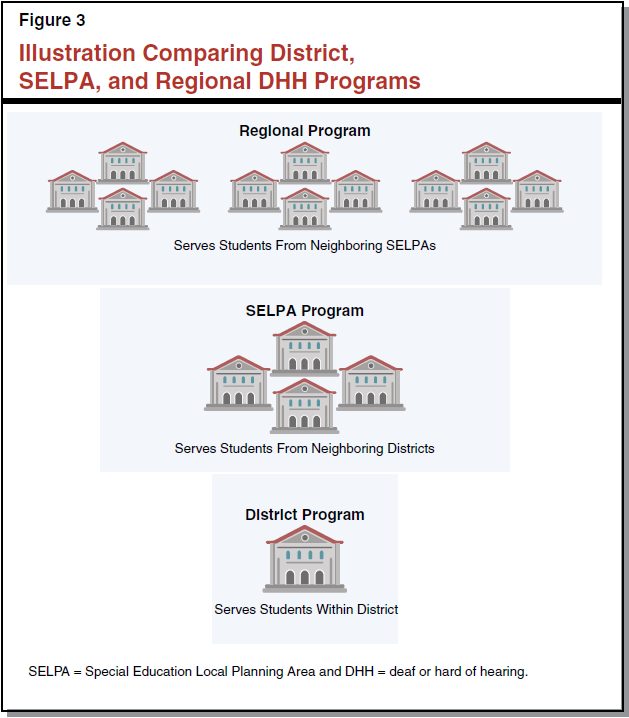

Regional Programs Help Foster Critical Mass, but Currently Are Rare. Regional programs are more likely to have a critical mass than programs organized within individual districts or Special Education Local Planning Areas (SELPAs). This is because regional programs draw DHH students from multiple SELPAs and serve them on a few campuses. Despite the advantages of assembling critical mass, relatively few regional programs exist in California today. These programs tend to be more difficult to form because they require school administrators both within and across SELPAs to agree on DHH programmatic and fiscal decisions.

The SSS Have Major Shortcomings. Though the SSS are intended to help foster critical mass by drawing together DHH students from sparsely populated areas of the state, the SSS serve mostly DHH students from urban areas. These are the students most likely to be able to access local programs with critical mass. Districts also currently pay far less to place DHH students at the SSS than they do to serve these students locally. This arrangement likely discourages some administrators from establishing their own regional programs. Finally, SSS funding is not linked to enrollment. Over time, inflation–adjusted SSS spending per student has increased significantly—the result of enrollment declines coupled with funding increases.

Recommendations

Encourage More Regional Programs to Foster Critical Mass. Though the state already fosters critical mass through SELPA arrangements, we believe the state could do more in this area—particularly given the low incidence of DHH students statewide. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature take three key actions to encourage more cross–SELPA regional programs. First, we recommend providing one–time grants to cover the cost of starting or expanding these programs. Second, we recommend simplifying the process for creating regional programs by allowing these programs to serve all interested students without first obtaining permission from their home districts. Third, we recommend authorizing regional programs to charge districts a reimbursement rate that covers the average cost of participating students. Based on our review of available cost data, we recommend initially setting a default rate of $35,000 per student.

Help the SSS Refocus on Serving Students From Rural Areas. Because even regional programs are unable to foster critical mass in some rural areas, we recommend refocusing the SSS to serve students from sparsely populated areas. To this end, we recommend the Legislature adopt an enrollment–based funding formula for the SSS that explicitly encourages rural enrollment while also reducing funding disparities between SSS and local DHH programs gradually over time. We further recommend providing transitional support to the SSS.

Change Reimbursement Rate SSS Charges Districts to Improve Student Placements. In tandem with the above recommendations, we recommend raising the amount districts pay to send students to the SSS initially to $35,000 (or the going rate for regional programs). Setting the rate at this level would lessen districts’ incentives to place students at the SSS solely for fiscal reasons. It also would encourage more districts to develop local DHH programs by minimizing the cost difference between placing students at the SSS and serving them directly. Finally, this change would result in state savings that could be redirected for the regional program grants mentioned above.

Introduction

California opened its first school for the deaf in 1860, long before it established most other forms of special education. Today, we estimate California spends more than $400 million a year to educate approximately 14,000 students who are deaf or hard of hearing (DHH). On a per–student basis, California spends substantially more to educate DHH students than other groups of children, including students with various other disabilities. Despite California’s long experience with and relatively large expenditures on DHH students, these students continue to lag far behind their hearing peers on statewide assessments of reading and math.

In this report, we undertake a comprehensive review of DHH education in California. We begin by describing the state’s current approach to DHH education, then identify several major shortcomings with this approach, and conclude by making recommendations to address the shortcomings.

Back to the TopBackground

DHH education in California can be characterized as having three main facets—students, programs, and financing. We discuss each of these below.

DHH Students

Few California Students Are DHH. DHH students comprise about 0.2 percent of all California students, and 1.9 percent of all California students in special education. Most DHH students are hard of hearing rather than deaf. Whereas about 1 in every 500 California students is hard of hearing, 1 in every 2,000 California students is deaf. Though more technical definitions exist, students who are hard of hearing generally require special amplification to hear normal speech, whereas students who are deaf generally cannot hear normal speech even with amplification.

Most DHH Students Experience Language Delays. Young children develop important cognitive skills by listening and responding to the language that surrounds them every day. As DHH children cannot listen and respond to spoken language as early as their hearing peers, they often develop early language and cognitive delays that hinder future academic progress. These delays tend to be more pronounced in DHH children born to hearing parents, as hearing parents tend to be less familiar with modes of communications that help DHH children develop in their early years. About 90 percent of DHH children are born to hearing parents. (As discussed in the nearby box, parents typically discover their child is DHH through a newborn hearing screening. Hospitals then refer DHH children for early education services.)

Early Screening and Services for DHH Children

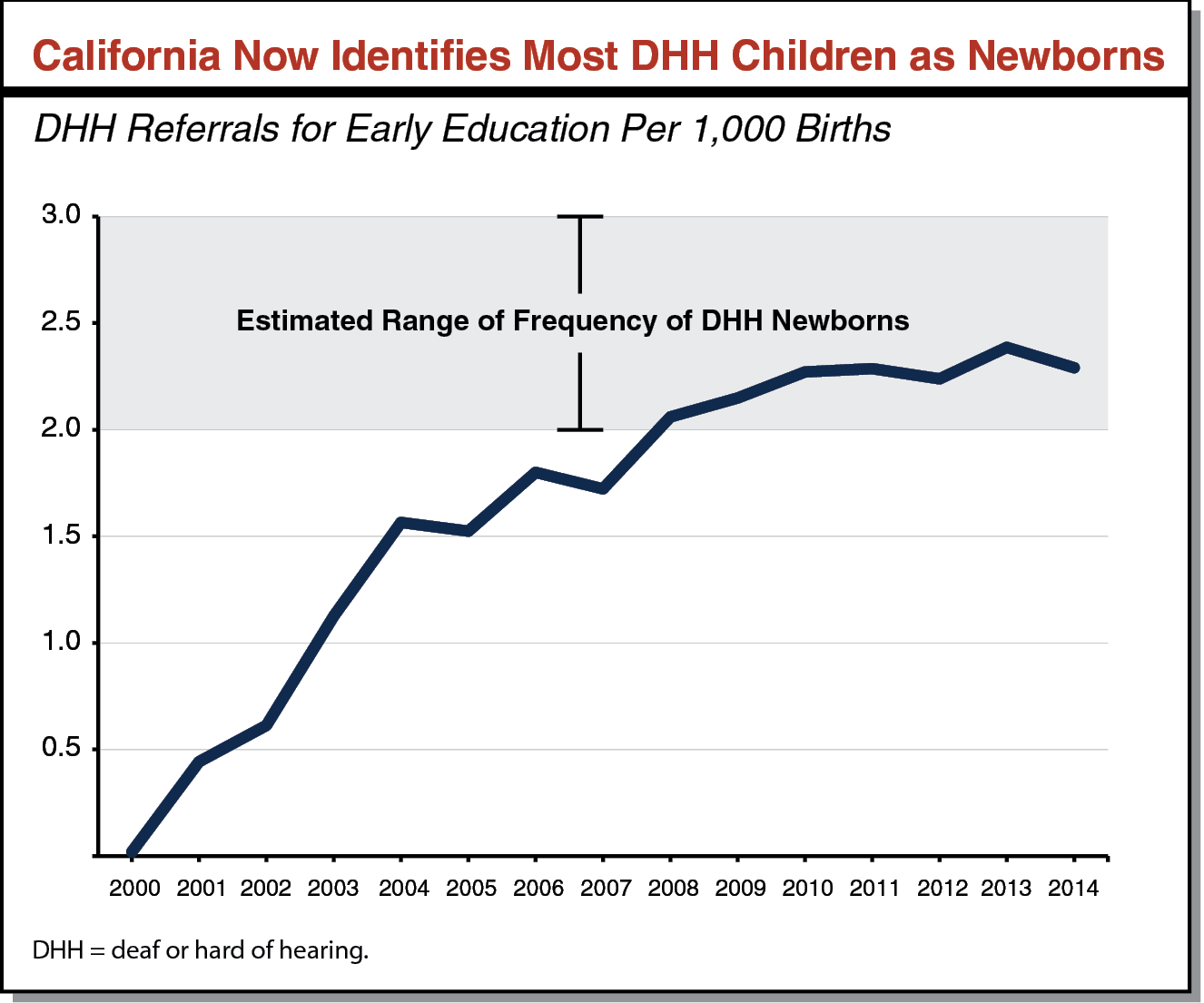

Newborn Screening Identifies Deaf or Hard of Hearing (DHH) Children. California requires hospitals and perinatal services to screen all newborns to identify those who are DHH. Since these requirements were introduced in 2000, compliance has improved to the point where the state now appears to identify nearly all DHH children as newborns. As shown in the figure below, the state now identifies between two and three DHH newborns for every 1,000 births, a number equal to the estimated national incidence of DHH newborns according to the Centers for Disease Control.

All DHH Infants and Toddlers Are Eligible for Early Education. Since 1993, California has provided early education to all DHH children from birth to three years old. Typically, early education specialists visit these children at home at least once a week to teach their parents how to foster healthy development. Recently, the Legislature passed a law establishing new language development benchmarks for DHH children in early education.

Language Delays Can Contribute to DHH Students Becoming Socially Isolated. Given the difficulty DHH students and their hearing peers have conversing with each other, DHH students in mostly hearing environments can be socially isolated. One strategy to prevent social isolation is to ensure these students attend schools with a critical mass of DHH peers. Though educators do not agree on what exactly constitutes a critical mass, some have suggested standards ranging from 3 to 20 DHH students per grade.

Most Districts Do Not Have a Critical Mass of DHH Students. Even if each district concentrated all of their DHH students on a single campus, most districts still would not assemble a critical mass. Of California’s approximately 1,000 school districts, we estimate only about 150 have at least 3 DHH students per grade and only about 5 have at least 20 DHH students per grade.

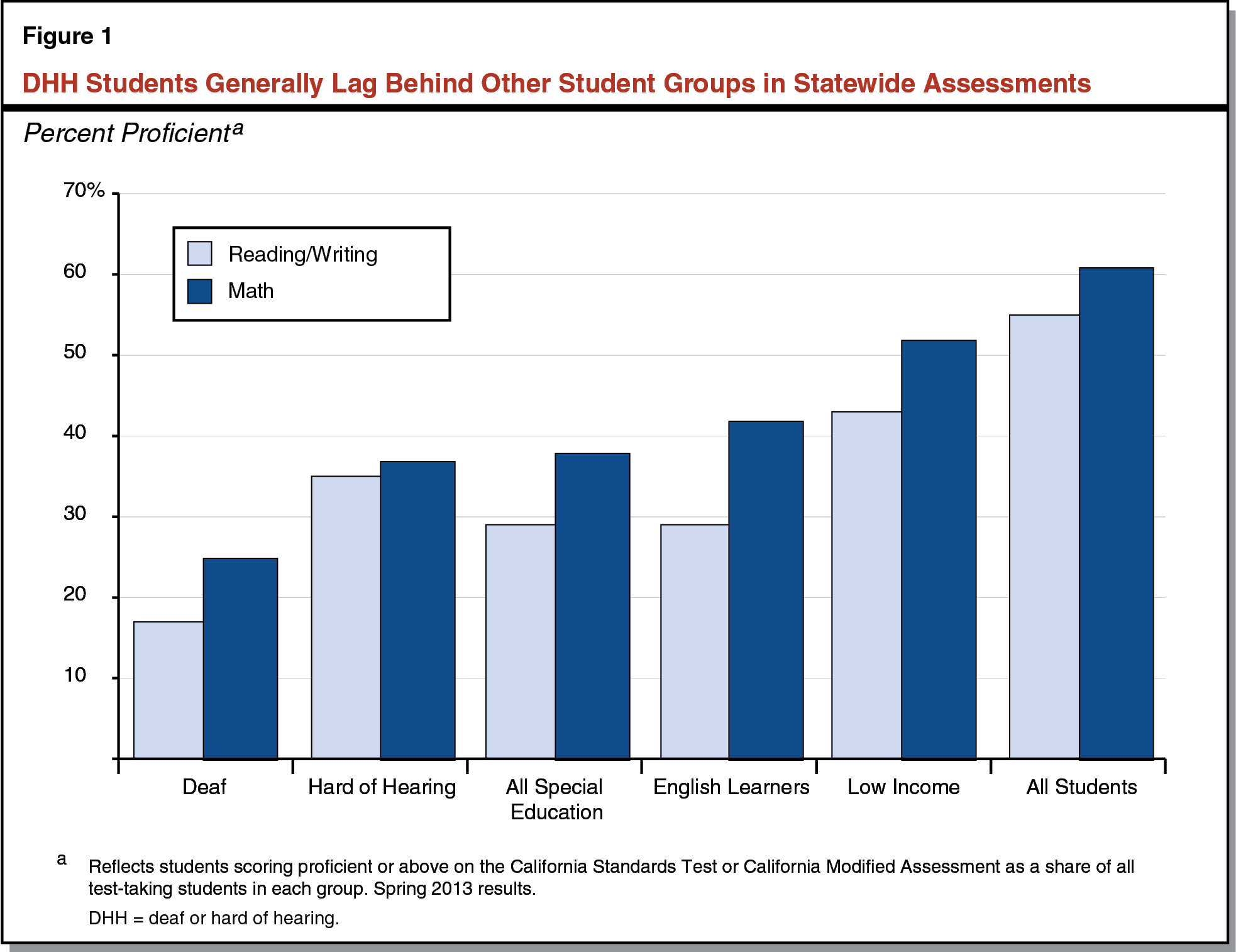

As a Group, DHH Students Have Low Test Scores. Though test scores for DHH students are not readily available, we obtained scores by submitting a special request to the California Department of Education (CDE). As Figure 1 shows, DHH students perform relatively poorly on statewide assessments, with fewer than 35 percent scoring at or above grade level on reading/writing and mathematics. Among DHH students, deaf students perform worse than those who are hard of hearing, particularly on assessments of reading/writing. DHH students also generally perform worse on statewide assessments than other groups of students, including students from low–income families, English learners, and other students with disabilities.

DHH Educational Programs

California offers a variety of DHH educational programs, with each defined by a particular combination of instructional approach, classroom setting, and instructional provider.

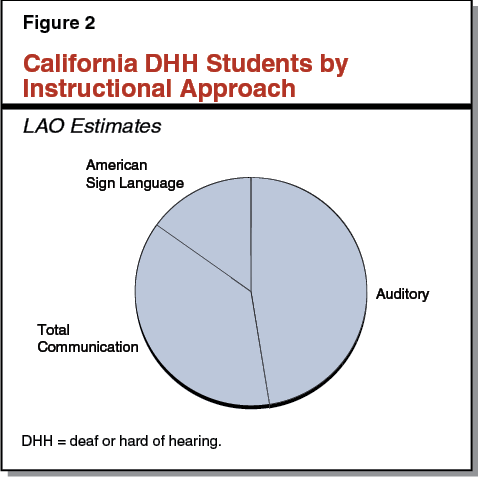

DHH Instructional Approaches

Auditory Programs Teach DHH Students to Use Spoken English. Instructional approaches for DHH students fall on a spectrum from the mostly auditory to the mostly visual. On the auditory end of this spectrum, DHH students receive instruction in spoken English. These students often use assistive technology such as hearing aids, cochlear implants, and classroom amplification systems. Many of these students also need special lessons to learn how to speak and read lips. As shown in Figure 2, we estimate that auditory instruction is the most common DHH instructional approach in California.

American Sign Language (ASL) Is a Visual Alternative to Spoken English. Users of ASL communicate through a combination of hand shapes, gestures, and facial expressions. Rather than a simple word–for–word translation of spoken English, ASL is a distinct language with a grammar, syntax, and history of its own.

Total Communication Programs Combine Auditory and Visual Approaches. These programs use multiple forms of communication simultaneously to engage DHH students. For example, teachers might use some ASL to augment instruction given mostly in spoken language or use some spoken language to augment instruction given mostly in ASL.

Choice of Best Instructional Approach Has Long Been Controversial. Schools have used the auditory and visual approaches since at least the early 1800s, and educators have long debated which approach works best for most students. ASL users believe sign language offers DHH students a sense of community and shared history they otherwise would lack. On the other hand, auditory proponents believe their approach offers DHH students a better chance to succeed in a mostly hearing world. Disagreements over the best instructional approach often divide the DHH community into two opposing camps. Both state and federal law now protect parents’ right to choose the instructional approach they believe to be best for their child.

DHH Classroom Settings

Mainstream Classes Integrate DHH Students With Hearing Peers. About 45 percent of DHH students spend most of their time in mainstream classrooms surrounded by hearing classmates. Most DHH students require special supports to be integrated into a mainstream environment. For example, some students might require hearing aids and special microphones to amplify their teachers’ voices, whereas other students might require sign language interpreters. Some students spend part of their day in a mainstream classroom and part of their day in “pull–out” services with special educators. These pull–out services might include speech therapy or one–on–one instruction with a DHH specialist.

Special Day Classes Integrate DHH Students With Special Education or DHH Peers. About 55 percent of DHH students spend most of their time in special day classes. Some special day classes include students with many different kinds of disability, whereas others serve only DHH students. Special day classes that serve only DHH students typically specialize in one instructional approach.

DHH Educational Providers

School Districts Serve Most DHH Students. We estimate roughly three–fourths of DHH students are served either by their home district or a neighboring district. DHH students in these programs generally are limited to whatever DHH offerings their districts provide. Some districts offer only one instructional approach (for example, auditory) whereas other districts, typically larger districts, offer a mix of approaches (for example, auditory and total communication). Because most districts lack a critical mass of DHH students, they tend to place DHH students either in mainstream settings or in special day classes that serve students with other kinds of disability.

Some Districts Run Small, Collaborative Programs for DHH Students in Their Vicinity. Recognizing that small and mid–sized districts likely do not have the means to fully serve all of their students with disabilities (including DHH students), the state requires these districts to collaborate with their neighboring districts to form Special Education Local Planning Areas, or SELPAs. In an effort to foster critical mass, some SELPAs have established centralized DHH programs that serve students from all of their member districts on one or two school sites. Although the state does not systematically track SELPA–run DHH programs, we are aware of dozens of such programs, including ones in urban areas (for example, the San Diego County Office of Education runs this type of program) and rural areas (for example, the Shasta County Office of Education also runs this type of program). We estimate SELPA–run programs serve between 10 percent and 20 percent of DHH students in California. SELPAs with a critical mass of DHH students are more likely to provide multiple DHH educational options, including special day classes that specialize in DHH education.

Some Districts Collaborate to Run Relatively Large Regional Programs. Because the incidence of DHH students is so low, even many SELPAs are not large enough to foster a critical mass of DHH students. We estimate about 25 percent of SELPAs do not have 3 DHH students per grade, and about 95 percent do not have 20 DHH students per grade. To further foster critical mass, neighboring SELPAs sometimes work together to create regional DHH programs that serve all students from participating SELPAs on a few school sites. For example, the regional program in Orange County concentrates DHH students from ten SELPAs onto two elementary schools, one middle school, and one high school. Regional programs typically offer the greatest breadth of educational options, sometimes even having multiple special day DHH options. Having more DHH–specific options gives families and educators the greatest chance to place each DHH student in an educational setting that meets his or her individual needs. Despite these advantages, we estimate regional programs serve only about 5 percent of DHH students in California, with most of these students living in urban areas. Figure 3 illustrates how regional programs compare to SELPA and district DHH programs.

Two State Special Schools (SSS) Serve a Small Number of DHH Students. Long before the state adopted its SELPA approach to special education collaboration, it opened and operated two state schools for DHH students. These schools were designed to foster critical mass by enrolling DHH students from across the state, especially DHH students from sparsely populated areas. Students in these areas have few, if any, other opportunities to be in a DHH program with a critical mass of DHH students. Today, a total of approximately 800 students (or about 6 percent of all DHH students) attend these two SSS, one located in Fremont and one in Riverside. These state–run schools serve mostly deaf students in an ASL special day class environment. About 60 percent of students at the SSS live on campus throughout the week but return home during weekends and school holidays. The remaining 40 percent of students live nearby and return home after school each day. (Throughout this report, we use SSS to refer to the two California Schools for the Deaf. The state also operates one school for the blind and three diagnostic centers for students with various disabilities.)

Nonpublic Schools (NPS) Serve a Small Number of DHH Students. A total of approximately 250 DHH students (or about 2 percent of all DHH students) attend six NPS in the state. NPS are nonprofit organizations that contract with school districts to educate students with disabilities in a special day class environment. Five NPS specialize in auditory instruction and one specializes in total communication. Today, NPS operate in the Bay Area (Berkeley, Redwood City, and San Francisco), the Los Angeles area (Culver City and Los Angeles), and Sacramento.

Choosing a DHH Program

Program Placement Decided by Parents, Teachers, and Administrators. Federal law outlines a process to determine what services to provide each student in special education, including DHH students. Under this process, a team composed of the student’s parents, teachers, and school administrators draft an annual service plan. For example, a student’s plan might specify whether the student will attend a special day class at a regional program or a mainstream class with an interpreter. Each member of the team must sign off on this plan.

Formal Process Resolves Disputes Between Parents and Their Districts. Parents and districts sometimes disagree about what specific services each child needs. For example, parents might want their child to attend an ASL special day class even though their district only offers mainstream classes with interpreters. If parents desire a particular program their district does not offer, they can request a due process hearing with the state Office of Administrative Hearings. Administrative law judges preside over these hearings and render decisions. When a decision warrants a certain education program, a district must either establish such a program or arrange for the student to be served by another provider.

Students Can Transfer Between DHH Programs Only With Permission From Their Home Districts. Under current law, all students need permission from their home districts before they can transfer to another district. This includes DHH students, who can only attend DHH programs in neighboring districts with the permission of their home districts. Districts may withhold this permission for any reason (unless the district is overruled in a due process hearing). For example, neighboring districts might disagree about whether DHH students should be taught in an auditory or an ASL program. The district favoring ASL can refuse to let its students transfer into its neighbor’s auditory program, and vice versa.

DHH Financing

The cost of DHH educational programs in California varies notably. Though costs vary, the same core set of funding sources—state, federal, and local—support these programs.

DHH Costs

DHH Educational Costs Are Driven by Services, Class Size, Caseloads, and Salaries. Though the state does not systematically track DHH educational costs, we collected expenditure data from various DHH programs. Using these data and making certain programmatic assumptions, we derived cost ranges for eight types of DHH programs (see Figure 4). For each combination of instructional approach and classroom setting, we assumed students receive a fixed bundle of DHH educational services. For example, we assumed students in an auditory mainstream program receive regular visits from DHH teachers, speech therapists, and audiologists, whereas students in a visual mainstream program are served by educational interpreters. After controlling for these bundles of services, we allowed costs to vary based on class size, caseloads for specialists (like audiologists and speech therapists), and salaries for teachers and specialists. Programs with relatively large classes and caseloads are less costly than smaller programs, as larger programs spread the cost of each bundle of services across more students. The most expensive programs tend to be those that provide ASL in mainstream classrooms, as educational interpreters typically have high salaries and serve only one student at a time.

Regional Programs Less Costly Than District Counterparts. As indicated in Figure 4, regional programs generally can offer any combination of instructional approach and classroom setting at lower cost than district programs. This is because regional programs tend to have larger class sizes and caseloads. Because SELPA programs tend to be somewhat smaller than regional programs but somewhat larger than district programs, their costs tend to fall between regional and district ranges.

NPS Programs Cost About the Same as Similar Regional Programs. Districts pay a reimbursement rate for NPS services. According to their public rate schedules, NPS programs charge between $25,000 and $35,000 per DHH student, or approximately the cost of running an auditory special day class in a regional program with an equivalent bundle of services.

SSS Are Costly but Less Expensive Than Some Alternatives. In 2014–15, the SSS spent approximately $75,000 per day student and $103,000 per residential student (with an average overall per–student cost of $92,000). The cost of serving students at the SSS exceeds that of many, but not all, DHH educational programs in California. In particular, some parts of the state have a chronic shortage of educational interpreters, and schools in these regions must pay high rates to attract qualified interpreters. In these regions, the SSS might be the least expensive option for serving students who use ASL.

DHH Educational Funding

State, Federal, and Local Funds Support District Programs. Districts receive state general purpose funding to serve all students, including DHH students. This funding covers the cost of basic educational services, such as textbooks and teacher salaries. On top of these funds, both the state and federal governments distribute additional funding to cover the cost of special education services, such as auditory equipment or salaries for interpreters and other specialists. When DHH program costs exceed combined state and federal special education funding, schools make up the difference out of their general purpose dollars, effectively reducing the funding available to serve non–DHH students.

Districts Reimburse Regional and NPS Programs for Full Cost of Service. Districts use the funding streams noted above to cover the cost of enrolling their students in regional programs and NPS, both of which charge reimbursement rates. Regional programs negotiate reimbursement rates with each district they serve. The NPS are required to submit their reimbursement rate schedules to CDE, which posts these rates each year on its website.

Districts Reimburse SSS for Small Part of Cost, State Covers Bulk of Remaining Cost. Each district pays a relatively small annual reimbursement rate of about $7,000 to the SSS. These rates are intended to cover roughly 10 percent of the per–student instructional cost at SSS. After accounting for both instructional and residential costs, district reimbursements constitute less than 5 percent of the overall SSS budget. The state provides almost all remaining SSS funding. The amount of state SSS funding in any given year is based primarily on the prior–year SSS funding level grown for certain state salary and benefit increases. (The SSS also receive a small amount of federal funding.)

Back to the TopAssessment

We have three main concerns with California’s existing approach to DHH education. As discussed below, we are concerned that the state is missing some opportunities to foster critical masses of DHH students, the SSS have significant programmatic and fiscal shortcomings, and data on key DHH outcomes are not available.

Missed Opportunities to Foster Critical Mass

Critical Mass Produces Several Programmatic and Fiscal Benefits. Large programs with a critical mass of DHH students have several advantages over smaller programs. First, DHH students in these programs are less likely to be socially isolated. Second, these programs are likely to offer a variety of instructional approaches, allowing parents and educators more opportunity to discover which approach works best for each student. Finally, because their teachers and specialists are able to serve many DHH students simultaneously, these programs have lower per–student costs than smaller DHH programs.

State Already Makes Efforts to Foster Critical Mass. The state already requires groups of small and mid–sized districts to collaborate on special education issues through their SELPAs. These SELPAs sometimes draw DHH students together across district lines to foster critical mass. Moreover, the state encourages DHH students living in sparsely populated areas to attend one of the state’s two residential DHH schools. In sum, the state already provides several opportunities for DHH students to be drawn together into larger, enriched, and more affordable DHH programs.

Regional Programs Are Rare, Seemingly Because Coordination Is Difficult. Despite existing state efforts to draw DHH students together, most districts and SELPAs still do not have critical masses of DHH students. As a result, the only practical option for achieving critical mass in many areas of the state is to establish regional programs. We are aware, however, of only a handful of regional DHH programs in California. Many administrators have told us regional programs are rare because neighboring SELPAs (and the districts they represent) often disagree on issues such as instructional approach and setting, location, finances, administration, and student transportation.

Low Reimbursement Rates at the SSS Might Discourage Regionalization. Though the SSS reimbursement rates originally were intended to encourage more districts to develop their own DHH programs, these rates currently are far below the cost of serving a DHH student in district, SELPA, or regional programs. As a result, districts and SELPAs concerned with ensuring their students have access to a critical mass of DHH peers have a strong fiscal incentive to refer students to the SSS rather than work through all the organizational issues necessary to establish regional programs.

Several Concerns With the SSS

Despite Statutory Mission, the SSS Serve Relatively Few Students From Sparsely Populated Regions. State law requires the SSS to give priority admission to students from sparsely populated regions. However, more than half of SSS students come from Riverside and Alameda counties, the densely populated counties where the SSS are located. Furthermore, of the remaining students who attend the SSS, most come from adjoining counties with dense urban populations. We estimate less than 15 percent of SSS students come from sparsely populated areas of the state.

Some Districts Are Reluctant to Refer Students to the SSS for Programmatic Reasons. Many administrators, including some in rural areas, have told us they are reluctant to refer students to the SSS due to specific programmatic concerns. The most common concerns raised are the SSS not providing all special education services outlined in a student’s individualized education plan and the SSS having unusually stringent student discipline practices. These concerns might explain why some districts rarely or never refer students to the SSS, even though it costs the districts significantly less to serve students at the SSS than in their own DHH programs.

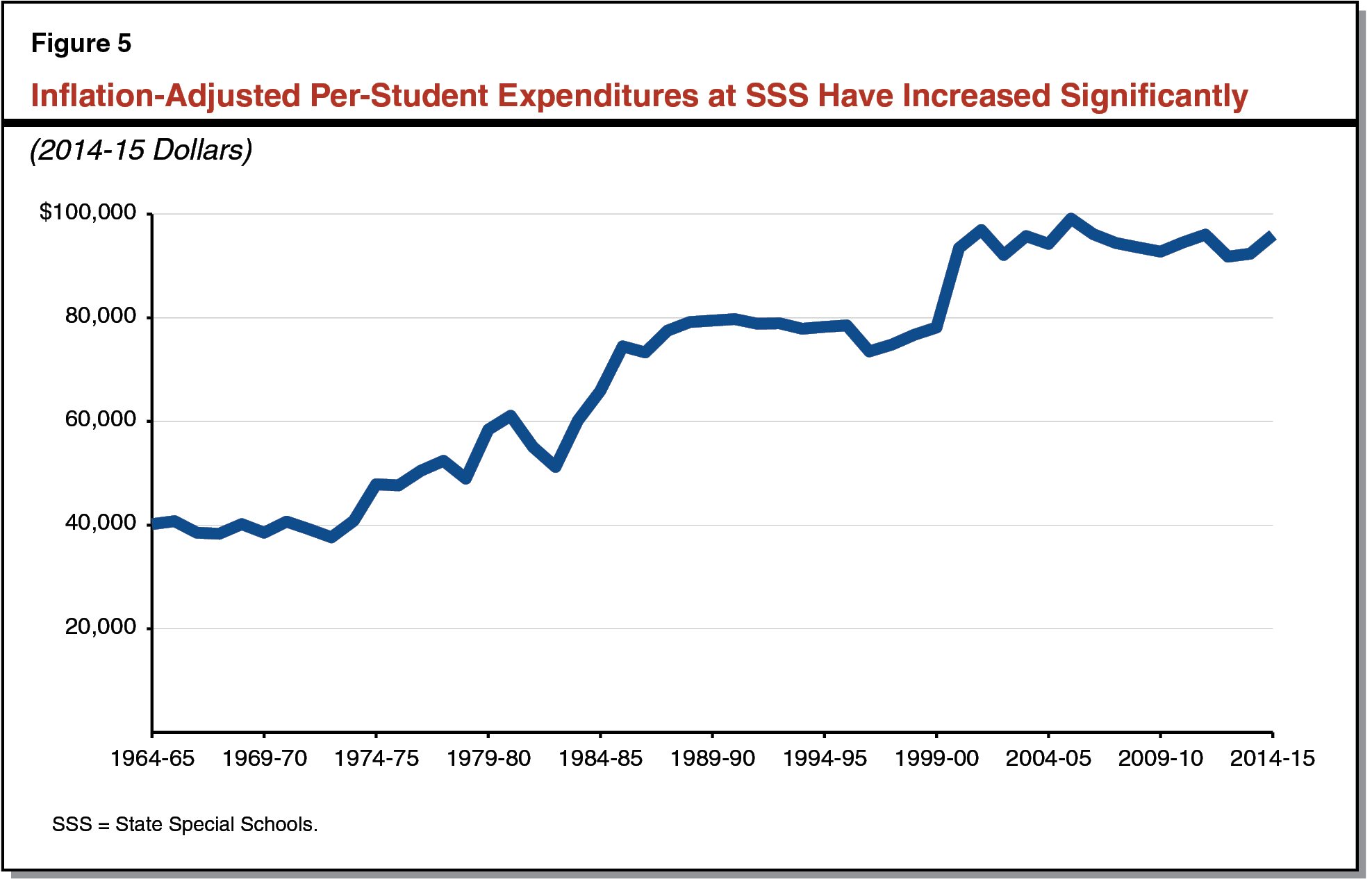

SSS Funding Is Not Linked to Changes in Enrollment. For all public schools other than the SSS, the state adjusts funding to reflect annual changes in student enrollment. As the state does not adjust SSS funding to reflect student enrollment, the SSS have no fiscal incentive either to increase their enrollment or prevent enrollment declines. Over the last 50 years, enrollment at the SSS has declined by more than 20 percent while overall funding for the SSS has increased significantly.

SSS Per–Student Costs Have Increased Significantly Over Time. As shown in Figure 5, inflation–adjusted, per–student expenditures at the SSS have increased by about 140 percent over the past 50 years. By comparison, we estimate inflation–adjusted, per–student expenditures for all other California schools increased by about 50 percent during the same period.

High Per–Student Costs Not Justified by SSS Student Characteristics. Despite their high per–student costs, the SSS do not appear to serve DHH students with unusually challenging needs. Students at the SSS are only somewhat more likely than DHH students in other settings to come from low–income families (68 percent at the SSS compared to 58 percent in other settings) or have multiple disabilities (13 percent at the SSS compared to 11 percent in other settings, excluding speech and language impairments).

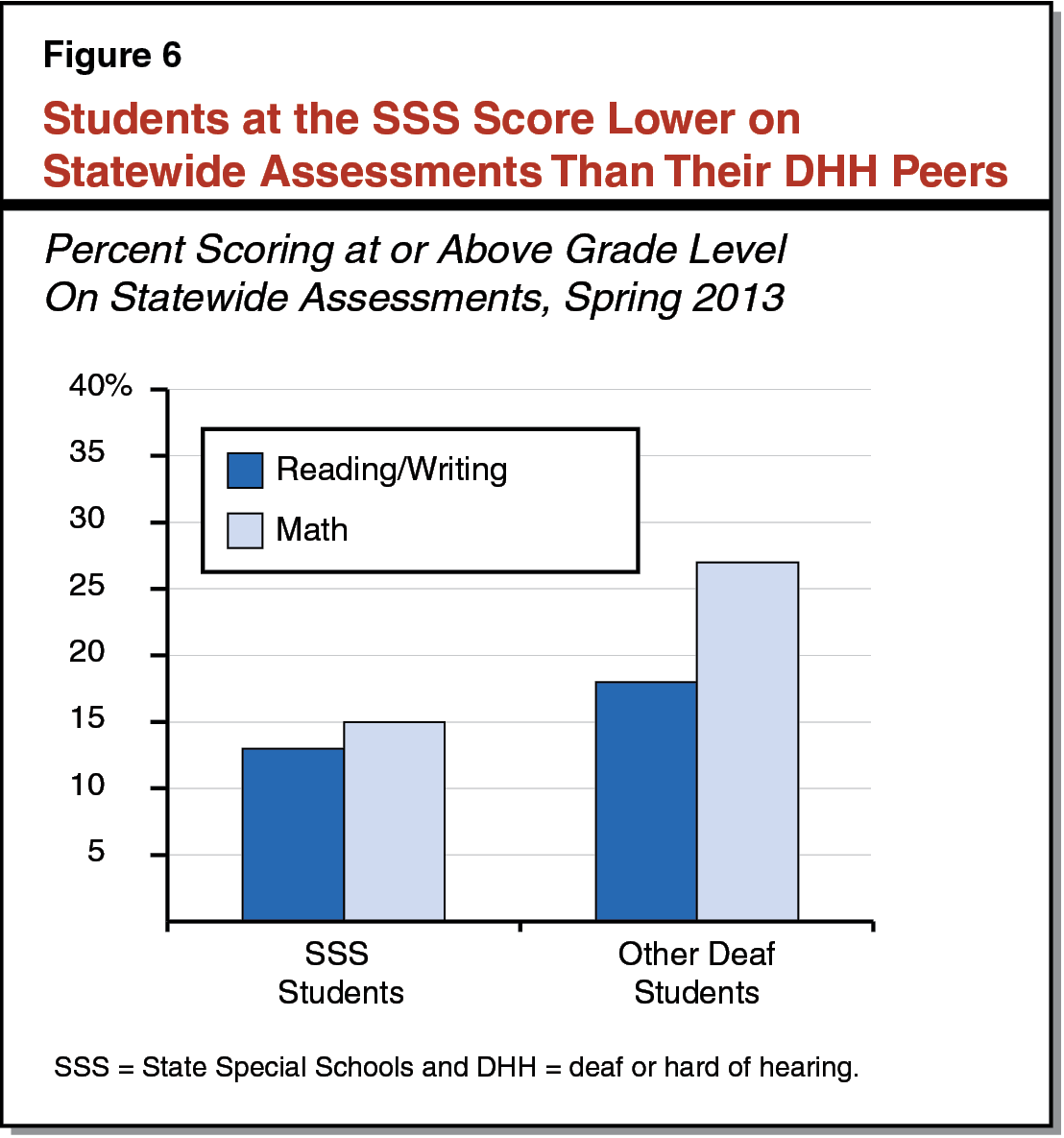

Despite Higher Per–Student Costs, Students at the SSS Lag Behind on Statewide Assessments. As Figure 6 shows, students at the SSS score lower on statewide tests than deaf students in other settings. (Nearly all students at the SSS are deaf rather than hard of hearing.) In particular, 13 percent of students at the SSS score at or above grade level on reading/writing as compared to 18 percent of deaf student in other settings, and 15 percent of students at the SSS score at or above grade level on math as compared to 27 percent of deaf students in other settings.

Limited DHH Data, Weak Public Accountability

No Subgroup Data Means No Way to Assess and Compare DHH Programs. To date, the state has not required districts to report test scores or graduation rates for DHH students as a subgroup. Instead, districts report outcomes for all students in special education as one group. The primary rationale for not reporting special education subgroup data appears to be protecting student privacy. Privacy issues, however, can be overcome by setting a minimum subgroup size (typically 10 to 15 students) for reporting purposes. Without key DHH outcome data, parents and policymakers currently cannot compare DHH programs or assess the overall success of DHH education in the state.

Back to the TopRecommendations

Below, we recommend steps to improve DHH education in California without increasing state spending (see Figure 7). Specifically, we recommend creating more opportunities for critical mass by encouraging greater use of regional programs, helping the SSS fulfill its core mission of serving students from rural areas, and making DHH student data more readily available. The recommended changes to the SSS free up some funding that we recommend repurposing for regional DHH programs.

Figure 7

Summary of Key Recommendations

|

Foster More Opportunities for Critical Mass

|

|

Help the SSS Fulfill Their Core Mission

|

|

Provide Better Data

|

|

DHH = deaf or hard of hearing and SSS = State Special Schools. |

Provide More Opportunities for Critical Mass

Provide Incentive Grants to Start or Expand Regional Programs. As noted above, regional programs offer the only practical option for creating a critical mass of DHH students in some parts of the state. To help foster these programs in more areas of the state, we recommend the Legislature fund a new, three–year grant program. The grants would be intended to encourage more districts and SELPAs to work together across SELPA lines to form or expand regional programs. We recommend providing up to a total of $75 million for the grant program, or $25 million per year. (This amount is linked to certain SSS reimbursement rate changes that we recommend in the next section—changes that free up about $25 million in state funds per year.) To obtain grants, new or existing regional programs would submit applications specifying the number of students they intend to serve and the specific expenses they intend to incur. Recipients could use grants for any reasonable associated cost, including DHH program coordination and outreach, curriculum development, instructional materials, audiological equipment, hiring and moving bonuses for new DHH staff, and facility renovations or expansions. We recommend varying grant amounts based on DHH enrollment so that larger programs receive larger grants. Additionally, we recommend grants be allocated broadly across the state. As discussed in more detail in the nearby box, we recommend that a temporary committee administer the incentive grant program.

Establish a Deaf or Hard of Hearing (DHH) Educational Committee

Task Committee With Selecting Grant Recipients. We recommend the Legislature establish a committee to implement the new incentive grant program. We recommend the committee establish specific application procedures and select grant winners. At a minimum, we recommend the applications be required to outline a comprehensive vision for a new or expanded regional program. The committee could evaluate applicants using a basic set of criteria, including: the projected number of students served, the soundness of the proposed fiscal plan, the variety of instructional approaches offered, the proposed location and its centrality for DHH families, and geographic proximity to other regional DHH programs. Grant recipients would be granted state approval to operate regional programs moving forward.

Set Committee Membership, Staffing, and Funding. We recommend the committee be large enough to represent the diversity of stakeholders in DHH education but small enough to conduct business in a timely manner. For example, the Legislature could create a seven–member committee, with one representative each from the State Special Schools, Nonpublic Schools, the State Board of Education, California’s Deaf Access Program, and higher education, as well as two local special education administrators. We recommend providing enough funding for the committee to hire two limited–term staffers and provide each committee member with a small stipend (for example, $15,000 per year) to compensate for his/her time and expense. We recommend establishing the committee for three years, consistent with the duration of the grant program, though we expect somewhat more work to occur in the first year of implementation compared to the next two years.

Allow DHH Students to Freely Enroll in Any Regional Program. We recommend requiring regional DHH programs to annually specify their enrollment capacity and enroll interested DHH students up to that capacity, selecting students by lottery if enrollment demand exceeds capacity. Likewise, we recommend allowing all DHH students to attend any regional program without first receiving permission from their home districts. As a result of this recommendation, districts or SELPAs would no longer need to negotiate a transfer agreement with each neighboring district, thereby greatly simplifying and streamlining their enrollment practices. This recommendation would also empower any DHH student living near a regional program to choose between that program and his/her home district program. To ensure these students have practical access to any nearby regional program, we recommend requiring that regional programs provide transportation to DHH students in their vicinity.

Empower Regional Programs to Charge a Reimbursement Rate, Set Default Rate. We recommend the Legislature authorize regional programs to charge districts a reimbursement rate that covers the cost of the students they serve. Based on our review of the cost of running a regional program, we recommend initially setting a default rate at $35,000 per student. As part of its incentive grant application, a regional program could propose a reimbursement rate that was higher or lower than the default rate, though the application would need to provide special justification for a higher rate. The DHH educational committee would make the final determination on a program’s rates and CDE would post each regional program’s annual rate publicly. We recommend adjusting all approved reimbursement rates annually to reflect the overall K–12 cost–of–living adjustment and revisiting the issue after ten years to ensure these rates still reflect relevant costs.

Help the SSS Fulfill Their Core Mission

Help the SSS Focus on Students From Rural Areas. If the recommendations we discuss above result in new and expanded regional programs, more DHH students would benefit from programs with critical mass. Regional programs, however, might remain uncommon in some rural parts of the state given that these programs would have to cover large geographic distances with few DHH students. Moreover, regional programs that do form in rural areas might not have all the DHH options provided by their urban counterparts. In particular, because relatively few DHH students use ASL, regional programs in rural areas might lack the students needed to operate an ASL special day class. For many DHH students in rural areas using ASL, the SSS therefore might be the only practical option for being in a program with their peers. To better serve these students, we recommend several changes to the SSS below.

Link State Funding to Changes in Enrollment. First, we recommend the Legislature adopt a statutory budget formula to adjust state SSS funding annually for changes in their enrollment, with the adjustments beginning in 2018–19. At a minimum, we recommend the new budget formula satisfy three major policy objectives: (1) ensure the SSS fulfill their mission of serving DHH students from sparsely populated areas, (2) reduce funding disparities between the SSS and local DHH programs, and (3) ensure a manageable transition from current funding levels. In the nearby box, we outline one possible funding model that satisfies each of these requirements.

Example of Enrollment–Based Funding Formula for the State Special Schools (SSS)

Increase Funding When Enrollment Increases, Decrease Funding When Enrollment Declines. One way to meet the guiding policy objectives would be to set one funding rate for enrollment growth and another rate for enrollment declines. Under this approach, the state would fund new SSS enrollment at the average cost calculated for comparable deaf or hard of hearing (DHH) programs. Though the SSS have a larger DHH student body than any existing DHH regional program, regional programs come closest to the SSS in terms of services provided and cost structure. For these reasons, the state could link the per–student funding rate for new SSS enrollment to the state default rate for regional DHH programs (initially $35,000). To this amount, the state could add the average cost of providing housing and transportation for SSS residential students, which is currently about $28,000. For enrollment declines, the state could decrease SSS funding based on the prevailing SSS per–student cost (currently $75,000 per day student and $103,000 per residential student). This enrollment–based approach ensures that funding is linked with students, new state funding is provided at comparable rates for students receiving comparable services, and funding for the SSS changes gradually. (The state uses a similar approach to fund overall special education enrollment.)

Measure Enrollment Using Three–Year Moving Averages. If the state were concerned about potentially large year–to–year changes in SSS enrollment under the new funding system, it could calculate SSS enrollment using a three–year moving average. This modification would provide SSS with an even more manageable transition to the new funding mechanism.

State Could Modify Formula to Encourage Rural Enrollment. If the state were concerned that the SSS lacked adequate incentive to recruit students from sparsely populated areas, it could fund new rural enrollment at a higher rate than new urban enrollment. One option would be to fund urban enrollment at the statewide average rate ($35,000), with the rural rate somewhat higher. Even with this modification, the funding formula still would decrease the funding disparity between the SSS and regional programs gradually over time.

Increase SSS Reimbursement Rates. In tandem with the shift to an enrollment–based funding formula, we recommend increasing the reimbursement rate the SSS charges each district such that these districts have a fiscally neutral choice between referring students to the SSS and establishing their own regional programs. We believe districts’ decisions to refer students to the SSS should be based on each student’s educational needs, rather than favoring the SSS because of a large fiscal incentive. To this end, we recommend linking the reimbursement rate for the SSS to the default reimbursement rate for regional programs ($35,000 initially).

New Reimbursement Rates Would Create State Savings, Recommend Using Mostly for Regional Programs. Higher reimbursement rates would shift some of the cost of the SSS from the state to districts. This would produce state savings without decreasing overall funding for the SSS. Under our recommended reimbursement structure, we estimate direct state appropriations to the SSS would decrease by approximately $25 million per year (assuming current enrollment), with district reimbursements increasing the same amount. As discussed above, we recommend repurposing the bulk of the freed–up state funds to help start and expand regional DHH programs.

Set Aside Some State Savings to Provide Transitional Support to the SSS. We recommend dedicating any state savings not designated for regional programs to short–term, transitional support to the SSS. The state could provide some transitional support if SSS enrollment declined significantly during the transition to a new funding formula and reimbursement system. This transitional funding could be structured to phase out gradually over a period of three to five years, giving the SSS time to recruit new students and adjust to any funding change. The state also could award SSS a small amount of transitional funding ($60,000 per year for two years) upon state approval of a proposal to hire a limited–term consultant focused on strengthening SSS’s relationship with rural SELPAs. At a minimum, this consultant could help the SSS conduct outreach to rural SELPAs as well as examine and make recommendations for improving programmatic aspects of the SSS.

Over Long Run, State Savings Would Be Available for Other Purposes. Over the long run, any state savings generated by the change in the SSS reimbursement rate structure would be available for any special education priority, including additional support for DHH programs.

Publish Data on DHH Student Outcomes

Report Data on DHH Student Performance. We recommend the Legislature require CDE to report some student outcome data by disability category. Specifically, we recommend that test scores and graduation rates be reported for any group of ten or more students who share a disability. By restricting these reporting requirements to groups of ten or more students, this recommendation would balance the demand for better information with the need to protect student privacy. We recommend requiring outcomes be reported at the school, district, county, SELPA, and state levels. (For example, if a county has ten DHH students spread across several districts, the average test results for the group would be reported at the county level but not at the district or school level.) These data would enable policymakers to better track the performance of DHH students as a subgroup and determine whether the legislative reforms outlined above, if enacted, resulted in improved outcomes.

Conclusion

California’s DHH students have unique needs that too often are not met by the state’s existing educational system. We believe the recommendations outlined in this report would improve DHH education by encouraging more regional programs and refocusing the SSS to serve students from sparsely populated regions. We believe the state could implement these changes without additional overall spending. By repurposing some existing DHH funding, the state could achieve better overall DHH outcomes, including better service and achievement for many DHH students in the state.